Abstract

A direct modification of the surface of the basalt fabric was carried out by using magnetron sputtering to obtain composites intended for effective protection against contact and radiant heat. One-layer composite with a coating of aluminum (Al) and zirconium dioxide (ZrO2), two-layer composite with a coating of Al/ZrO2, and two-layer composite with a coating of Al/(ZrO2 + titanium dioxide [TiO2]) were deposited on the fabric surface. Scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis was used to assess the coating on basalt fabrics and determine their chemical composition. Parameters such as thermal conductivity coefficient, resistance to radiant heat, and resistance to contact heat for a contact temperature of 250°C were determined for assessment of the composites from the point of view of protective properties. The similarity analysis of composites was performed to state the impact of coating components’ content and coating thickness on chosen parameters. It was found that a two-layer composite in which the outer layer is Al and the inner layer is a mixture of ZrO2 and TiO2 provides good thermal insulation properties. The composites capable of protecting against contact heat at the first efficiency level and against radiant heat at the second efficiency level were obtained.

1 Introduction

Basalt fibers are called man-made mineral fibers. They are chemically mineral fibers. Textile products made from them, including personal protective equipment, can be used at temperatures up to 700°C [1,2,3,4]. Basalt fiber products have mainly characterized by low moisture absorption, low thermal conductivity, good thermal resistance, good resistance to chemicals, and high mechanical strength and are biodegradable; therefore, they are an alternative to S and E glass fibers. Basalt fabrics may irritate the respiratory tract, skin, and eyes without coating. Currently, basalt fibers are used primarily in the production of specialized products. Due to their fire-resistant properties, fabrics made of basalt fibers are used in accessories and protective clothing, e.g., in gloves to protect against high temperatures or in the form of protective coats [5,6,7,8]. Fabrics made of basalt fibers are used in military and aerospace equipment as thermal and acoustic insulation materials, sound-absorbing barriers, fire-resistant curtains, and road surface reinforcements [9]. Basalt textiles are also used to reinforce concrete and in the production of composites [10,11]. Moreover, as filter materials, they can be applied in the petrochemical, petroleum, and chemical industries [1].

Due to the rapid development of materials used in technical textiles, surface modification and functionalization are frequently used [12,13]. One way to modify the fabric surface is to use the physical vapor deposition (PVD) process [14,15]. The process involves creating a coating on a substrate by physically depositing ions, atoms, or molecules. The physical deposition of vapor phase coatings, called PVD methods, is inextricably linked to the development of vacuum technology. In their most basic forms, PVD methods use two methods for changing the state of matter of the coating material: evaporation, sublimation (usually thermal), and sputtering, which occur under the influence of other, non-thermal physical forces. Depending on how the deposited materials are obtained, three types of PVD processes can be distinguished: classic evaporation (evaporation), ion plating (modification of the traditional process by applying an electric field, i.e., sputtering), and sputtering (in many different types of sputtering). Each procedure is performed in a vacuum range of 10−5 to 10 Pa [14,16,17]. The sputtering method can transfer metallic materials to textile surfaces [18]. The deposition of titanium dioxide (TiO2), zirconium dioxide (ZrO2), zinc oxide, and the production of coatings on the surface of textile materials are reported [12,13,16,18,19]. The modifications lead to improved properties, such as fire resistance, thermal conductivity, antibacterial properties, electromagnetic shielding, self-cleaning properties, and resistance to UV radiation [13,17,18,20,21]. The functional properties of the deposited coatings depend primarily on individual physical properties and proper adhesion to the substrate. Heat transfer through textile substrates is a very complicated and complex phenomenon. When examining heat transfer through textiles or textile products, the influence of various factors should be considered, i.e., raw material composition, thickness, weave, weft and warp number, and the thermal conductivity of fibers.

Research was carried out on the influence of fabric surface modification on thermal properties [22]. The tests selected included an aramid fabric with an aluminum (Al) coating on its surface (the one-layer coating), the two-layer coating of Al with silicon dioxide (SiO2), and the three-layer coating of SiO2/Al/SiO2. The Al coating was deposited on the fabric surface using direct current magnetron sputtering, while the non-metal coating, SiO2, was deposited using alternating current magnetron sputtering. All three coatings deposited on the surface of the aramid fabric were found to be continuous. The one-layer Al coating was the smoothest, while the three-component coating was the roughest. It was confirmed that the resistance to thermal radiation improved for three samples of aramid fabric modified with three coatings. The reflectance values for SiO2/Al/SiO2, SiO2/Al, and single Al were 65, 57, and 52%, respectively.

The thermal and physical properties of polyamide fabric, modified by a sputtering method using Al, copper, and nickel, were studied [23]. The tests used polyamide fabric and Mylar® foil, one of which was electro-conductive due to the sputtered Al. It was found that the fabric had a rough surface. Energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry revealed that the surfaces of the samples contain over 80% of the content of individual metals. The conductive fabric exhibited the highest stiffness because it was densely woven. Due to its high bending stiffness compared to other fabrics, it was noticed that the conductive fabric has a low drapeability, especially when the Mylar® foil has high stiffness.

The heat transfer of Al-sprayed textile materials was investigated [24]. The selected metal was sprayed onto four different textile substrates: polyamide, polyester, a 50/50 cotton/polyester blend, and shape memory polyurethane. The Al was sprayed on one sample side only. It was observed that the coating thickness increased linearly with the sputtering time. It was found that unmodified fabrics and fabrics modified with a metal coating were characterized by different thicknesses, different thermal conductivity, and different heat emissivity. It was observed that the heat transfer of the Al coating increased with its thickness. The cotton/polyester sample was characterized by the lowest heat transfer coefficient.

The direct modification of the surface of basalt fabric was applied to improve its thermal properties [25]. Chromium, Al, and zirconium coatings of various thicknesses were deposited on the surface of the basalt fabric. The surface-modified fabric was tested for resistance to contact heat at contact temperatures of 100 and 250°C and for resistance to radiant heat. The results of direct fabric modification were not satisfactory; therefore, the composites were taken into consideration [26]. The composites consisted of basalt fabric, silicone or glue, and a modified Mylar® foil with a coating of Al, ZrO2, and zirconium(iv). It was found that the basalt fabric-based composites showed improved resistance to contact heat and thermal radiation. The composites achieved resistance to contact heat at a contact temperature of 250°C. It was observed that as the resistance of the tested samples to the contact heat increases, their resistance to thermal radiation declines.

The literature review concluded that the direct modification of the basalt fabric is the right solution to obtain composites intended for effective protection against contact and radiant heat. The advantage of this modification method is that it produces a more flexible composite designed for the outside in a package of materials comprising protective clothing or accessories used in a hot work environment than composite with foil. One- and two-layer composite coatings were applied to assess and shape the protective properties of the basalt fabric-based composite. The magnetron sputtering technique was performed with single and composite coatings in various thickness configurations using Al and a mixture of ZrO2 and TiO2.

2 Materials

Basalt fabric was used as a textile substrate of composites. The fabric parameters are given in Table 1.

Parameters of basalt fabric (parameter with coefficient of variation)

| Sample | Weave | Thickness (mm) | Areal density (g/m2) | Bulk density (kg/m3) | Warp density (threads/cm) | Weft density (threads/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Twill 2/2 | 0.550 (2%) | 380 (0.1%) | 691 | 13 | 11 |

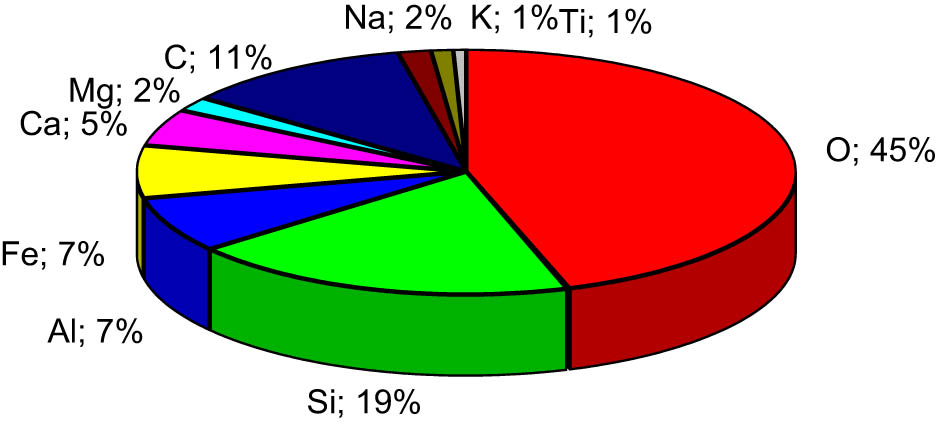

The chemical composition of basalt fabric using the scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) method is shown in Figure 1.

Chemical composition of basalt fabric.

The surface of fabric samples was modified on one side using the following elements and compounds (Table 2): Al, zirconium(iv) oxide (ZrO2), and titanium(iv) oxide (TiO2).

Chosen characteristics of elements and compounds [27]

| Element/compound | Density (g/cm3) | Thermal conductivity coefficient (W/(m K)) | Specific heat (J/(kg K)) | Thermal expansion (10−6/K) | Melting point (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 2.67–2.70 | 205.0–213.0 | 944–982 | 22.2–23.4 | 916–930 |

| ZrO2 | 5.00–6.15 | 1.7–2.7 | 450–540 | 2.3–12.2 | 2,823–2,973 |

| TiO2 | 3.97–4.05 | 4.8–11.8 | 683–697 | 8.4–11.8 | 2,103–2,123 |

Al was the outer coating of the composite as it is an excellent reflector of radiant energy. Al-based materials are heat-dissipating materials with strong corrosion resistance. The inner layer was ceramics (ZrO2 and TiO2) because of the material’s low thermal conductivity. The ceramic coating is characterized by good adhesion to the metallic substrate and chemical inertia. Both zirconia dioxide and TiO2 show high thermal expansion and good thermal insulation, which is confirmed by a low thermal conductivity coefficient. The composites with one-layer and two-layer coating were considered (Table 3).

Variants of basalt fabric-based composites

| Composite | One-layer coating | Two-layer coating | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | BZ | BAZ | BAZT | |

| Coatings | Al | ZrO2 | Al/ZrO2 | Al/(ZrO2 + TiO2) |

3 Methods

3.1 Magnetron sputtering technique

Magnetron sputtering is a deposition technique that relies on a glow discharge under reduced pressure and between two mutually perpendicular fields: electric and magnetic [14,28]. In this process, the emitted electrons move along the spiral path in a direction perpendicular to the direction of both fields along the magnetic field force lines. The interplay between these two fields leads to electron confinement within an excitation zone. Consequently, there is a substantial surge in ionizing collisions within the gaseous atmosphere. This phenomenon significantly enhances plasma excitation and substantially increases plasma density within the volume adjacent to the magnetron. A strong electric field accelerates positively charged ions toward the cathode. The ions hitting the cathode surface cause its intensive sputtering. Magnetron sputtering can be carried out in an inert atmosphere, a result of which metallic coatings are produced. Magnetron sputtering can also be taken in an atmosphere that is a mixture of reactive gases, which makes coatings that are compounds (metals with carbon, oxygen, or nitrogen).

Basalt fabric was subjected to the deposition of coating process by the magnetron sputtering using Al, zirconium(iv) oxide, and titanium(iv) oxide. The magnetron sputtering coatings’ deposition was performed using an industrial vacuum unit URM 079 equipped with one magnetron plasma source. Detailed deposition parameters of coatings manufactured using the magnetron sputtering technique are given in Table 4.

Parameters of a deposition process

| Composite | Coating | Coating thickness (µm) | Process time (min) | Residual pressure (Pa) | Process pressure (Pa) | Flow of Ar and O2 (sccm) | Power on magnetrons (kW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA1 | Al | 1.0 | 28 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 3.7–3.8 × 10−1 | 25; 0 | 2 × 1.0 (Al) |

| BA2 | Al | 5.0 | 140 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 3.7–3.8 × 10−1 | 25; 0 | 2 × 1.0 (Al) |

| BZ1 | ZrO2 | 1.0 | 35 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 3.8–4.0 × 10−1 | 25; 12–13 | 2 × 1.5 (Zr) |

| BZ2 | ZrO2 | 5.0 | 175 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 3.8–4.0 × 10−1 | 25; 12–13 | 2 × 1.5 (Zr) |

| BAZ1 | Al/ZrO2 | 0.2/2.0 | 82 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 3.7–4.0 | 25; 12–13 | 2 × 1.5 (Zr) |

| 2 × 1.5 (Al) | |||||||

| BAZ2 | Al/ZrO2 | 1.0/0.5 | 53 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 3.7–4.0 | 25; 12–13 | 2 × 1.5 (Zr) |

| 2 × 1.5 (Al) | |||||||

| BAZ3 | Al/ZrO2 | 1.0/1.0 | 72 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 3.9–4.1 | 25; 12–13 | 2 × 1.5 (Zr) |

| 2 × 1.5 (Al) | |||||||

| BAZ4 | Al/ZrO2 | 2.0/2.0 | 150 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 3.9–4.1 | 25; 12–13 | 2 × 1.5 (Zr) |

| 2 × 1.5 (Al) | |||||||

| BAZT1 | Al/(ZrO2 + TiO2) | 0.5/1.0 | 56 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 4.5–4.6 | 25; 12–13 | 1 × 1.5 (Zr) |

| 1 × 1.5 (Ti) | |||||||

| 2 × 1.0 (Al) | |||||||

| BAZT2 | Al/(ZrO2 + TiO2) | 0.3/2.0 | 90 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 4.5–4.7 | 25; 12–13 | 1 × 1.5 (Zr) |

| 1 × 1.5 (Ti) | |||||||

| 2 × 1.0 (Al) | |||||||

| BAZT3 | Al/(ZrO2 + TiO2) | 1.0/1.0 | 76 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 4.5–4.6 | 25; 12–13 | 1 × 1.5 (Zr) |

| 1 × 1.5 (Ti) | |||||||

| 2 × 1.0 (Al) | |||||||

| BAZT4 | Al/(ZrO2 + TiO2) | 1.0/2.0 | 110 | ∼2 × 10−3 | 4.5–4.7 | 25; 12–13 | 1 × 1.5 (Zr) |

| 1 × 1.5 (Ti) | |||||||

| 2 × 1.0 (Al) |

3.2 SEM-EDS technique

SEM-EDS [29] was used to assess coating on basalt fabrics and determine their chemical composition. SEM-EDS is a powerful analytical technique commonly employed in materials science and various fields to examine the surface morphology of materials and identify the elements present in a sample. EDS is an integral part of SEM that provides information about the chemical composition of the material. When the focused electron beam of the SEM interacts with the sample, it causes the emission of characteristic X-rays from the elements present in the sample. This technique allows for detailed visualization of the coating thickness, texture, and any defects or irregularities. A JEOL JSM-6610 LV scanning electron microscope working in a low vacuum mode with an attached Oxford Instrument X-MAX 80 module was used.

3.3 Thermal conductivity

The thermal insulation properties of composites were assessed based on the thermal conductivity coefficient [30]. The thermal conductivity coefficient λ of homogenous materials expressed in W m−1 K−1 is given as follows:

where Q is the heat transmitted, A is the area, Δt is the temperature gradient, and h is the sample thickness.

Thermal conductivity is a material property that primarily determines the elementary functions of clothing, especially the user’s comfort. The thermal conductivity of materials can vary significantly depending on factors such as temperature, pressure, and composition. Alambeta (Sensora device) was used for testing basalt fabric-based composites [30]. A sample was placed between the upper plate with a temperature of 35°C (it should more or less correspond to the human skin temperature) and the perpendicular lower plate reaching the ambient temperature. Metal plates adhere to the tested sample with a pressure of approximately 200 Pa. The thermal conductivity coefficient (λ) is measured as the quantity of heat transported through the sample when the difference.

3.4 Resistance to contact heat

This testing aimed to assess the ability of basalt fabric and composites to resist contact heat. It is essential to evaluate their suitability for applications where protection against contact with hot surfaces is necessary. Two standards were taken into account. The primary standard for determining the contact heat resistance of the tested materials was ISO 12127-1:2016 [31]. Another standard was ISO 11612:2015 [32], which specified performance requirements for clothing to protect the user’s body from heat, flames, and other related hazards, excluding the hands. The test sample was placed on a calorimeter and then in contact with a heater heated to a temperature of 250°C. The threshold time t t was measured from the moment the sample contacts the heater until the calorimeter temperature rises by 10°C. According to the standard [32], three efficiency levels (F1, F2, and F3) were considered:

F1 when t t falls within the range of [5.0, 10.0) s,

F2 when t t falls within the range of [10.0, 15.0) s,

F3 for t t greater than or equal to 15.0 s.

A longer threshold time indicates that the material can withstand contact with a hot surface for a more extended period before allowing significant heat transfer.

3.5 Resistance to radiant heat

This testing aimed to assess the ability of basalt fabric and composites to resist radiant heat. Radiant heat resistance is significant when evaluating materials intended for clothing that protect against heat and thermal radiation. Materials were tested to determine the radiant heat resistance based on standard [33]. A sample was placed on an appropriate holder and subjected to thermal radiation for a set time. An incident heat flux density of 20 kW/m2 was taken into consideration. The time it took for the calorimeter temperature to rise by 24.0°C (± 0.2)°C was measured according to test method B. This temperature rise indicates that the user experienced second-degree burns. Four efficiency levels were considered based on estimated time RHTI24 – the radiant heat transfer index [33]:

C1 when RHTI24 falls within the range of [7.0, 20.0) s,

C2 when RHTI24 falls within the range of [20.0, 50.0) s,

C3 when RHTI24 falls within the range of [50.0, 95.0) s,

C4 for RHTI24 greater than or equal to 95.0 s.

3.6 Similarity analysis of composite features

A geometric analysis of the similarity of composite features was performed to assess the impact of coating components content and coatings thickness on the thermal conductivity coefficient (λ), the resistance to contact heat (t t), and the resistance to radiant heat (RHTI24). Geometric similarity exists when two objects look exactly alike except for the fact that they are of different sizes. Similarity-based classifiers estimate the class label of a test sample based on the similarities between the test sample and a set of labeled training samples and between the pairwise of the training samples [34,35].

Let X be the sample space and G be the finite set of class labels. Let D: X × X → R be the similarity function. It is assumed that the pairwise similarities between n training samples are given as an n × n similarity matrix S whose (i, j)-entry is D(L i , L j ), where L i ∈ X denotes the ith training sample and y i ∈ G the corresponding ith class label (i = 1,2, …, n). Let the tangent distance-based classifier be the measure of similarity between pairwise of the training samples (variables). Tangent distance determines the relationship between the directions of vectors of variables L i and L j and is expressed as follows:

where r i,j is the linear correlation coefficient between variables L i and L j , i, j = 1,2, …, n.

Variables whose vectors in the multidimensional feature space are parallel (r = 1) or antiparallel (r = −1) carry the same information, and their tangent distance equals 0. Variables whose vectors are orthogonal (perpendicular to each other; r = 0) carry entirely different information and have a tangent distance equal to infinity. For remaining cases, i.e., for variables whose value of the linear correlation coefficient is greater than −1 and less than 0 or greater than zero and less than 1, the tangent distance measure takes a deal from 0 to infinity. It means that the greater the distance between the variables, the less they carry common information.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 One-layer coating composites

Preliminary studies of one-layer coating composite were conducted. Zirconia(iv) oxide and Al coatings of various thicknesses were deposited on the basalt fabric surface to assess the impact of coating thickness on resistance to contact and radiant heat of the composite. Two variants of the coating thickness were considered: 1.0 and 5.0 μm. The deposition parameters of the coatings manufactured using magnetron sputtering are given in Table 4. The measurement results of the resistance to contact heat for a temperature of 250°C and radiant heat for the one-layer coating composites are shown in Table 5 [20]. Additionally, results obtained for basalt fabric B are also juxtaposed for comparison.

Resistance to contact and radiant heat for basalt fabric and one-layer coating composites

| Composite | B | BA1 | BA2 | BZ1 | BZ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ × 10−3 (W m−1 K−1) | 38.2 | 46.7 | 45.3 | 41.0 | 44.0 |

| t t (s) | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 8.0 |

| RHTI24 (s) | 12.6 | 20.7 | 24.2 | 10.8 | 11.6 |

The thermal conductivity coefficient of composites with one-layer coating increased compared to unmodified basalt fabric. The impact of the kind of deposited material (Al or ZrO2) on the coefficient λ is not observed. The first efficiency level (F1) of protection against contact heat was achieved for the 5.0 μm thick ZrO2 coating of basalt fabrics BZ2 for a contact temperature of 250°C. The first efficiency level (C1) of protection against radiant heat was achieved for samples B, BZ1, and BZ2. The second efficiency level (C2) of protection against radiant heat was achieved for both Al coating thickness of fabrics (BA1 and BA2). Even a thin coating of Al resulted in a significant improvement in the composite resistance to radiant heat. Basalt fabric-based composites with a two-layer coating (Al/ZrO2) were manufactured to obtain materials protecting against contact and radiant heat.

4.2 Two-layer coating composites

Basalt fabric-based composites BAZ were manufactured. The magnetron sputtering parameters for two-layer coating (Al/ZrO2) composites are given in Table 4. The coating thickness in a single layer not exceeding 2.0 μm was taken into account. SEM-EDS results for BAZ composite coating are shown in Table 6. The results of thermal properties measurements for two-layer coating composites are shown in Table 7.

Chemical composition of BAZ coatings

| Chemical element | Amount (wt%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAZ1 | BAZ2 | BAZ3 | BAZ4 | |

| Al | 11.47 | 29.53 | 15.61 | 80.23 |

| Zr | 69.18 | 49.72 | 11.39 | 14.76 |

| O | 18.48 | 9.82 | 35.33 | 2.24 |

| Others | 0.87 | 10.93 | 37.67 | 2.77 |

Thermal properties of BAZ composites

| Composite | BAZ1 | BAZ2 | BAZ3 | BAZ4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ 10−3 (W m−1 K−1) | 34.8 | 39.8 | 36.3 | 37.8 |

| t t (s) | 6.2 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 8.5 |

| RHTI24 (s) | 18.5 | 22.7 | 23.6 | 27.0 |

The thermal conductivity decreased, meaning the two-layer composites are characterized by better thermal insulation than one-layer ones. It is a crucial fact that the inner layer was ZrO2 – the material characterized by low thermal conductivity compared to Al. The outer Al layer increases the thickness of the coating. The first efficiency level (F1) of protection against contact heat was achieved for BAZ1 and BAZ4 composites. The first efficiency level (C1) of protection against radiant heat was achieved for BAZ1, and the second (C2) was reached for composites BAZ2, BAZ3, and BAZ4. It means that the protective properties of the composites against radiant heat were visibly improved compared to one-layer coating composites. BAZ composites showed slightly better protection against contact heat.

The similarity analysis (I) was carried out for variables: L 1 – the weight percentage of zirconium dioxide (denoted as ZrO2 in Table 8), L 2 – the weight percentage of aluminum (denoted as Al in Table 8), L 3 – the total weight percentage of aluminum and zirconium dioxide (denoted as Al/ZrO2 in Table 8), L 4 – the thermal conductivity coefficient λ, L 5 – the threshold time t t, and L 6 – the radiant heat transfer index RHTI24. Results of the similarity analysis (I) of the composite features ordered from the smallest tangent distance (equation (1)) to the largest one between variables L i and L j are shown in Table 8. A positive “+” and negative “−” correlation for the chosen pairs of variables is also given.

Similarity analysis (I) of BAZ composites

| Variable L i | Variable L j | D(L i , L j ) | r i,j |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZrO2 | RHTI24 | 0.11 | − |

| Al | RHTI24 | 0.66 | + |

| Al | t t | 0.71 | + |

| Al/ZrO2 | t t | 1.34 | + |

| ZrO2 | t t | 1.58 | − |

| Al | λ | 2.11 | + |

| ZrO2 | λ | 2.14 | − |

| Al/ZrO2 | λ | 6.04 | + |

| Al/ZrO2 | RHTI24 | 20.53 | − |

The shortest tangent distance was noticed between the weight percentage of ZrO2 observed on the coating surface and resistance to radiant heat RHTI24. A strong relationship was confirmed (r 1,6 = −0.994), which indicates that the higher the weight percentage of ZrO2 detected on the surface, the lower the composite resistance to radiant heat. At the same time, the analysis results indicate that the resistance to radiant heat will increase with the increase in Al (r 2,6 = 0.833). The comparable tangent distance between Al and resistance to contact heat t t was also noticed. Thus, the increase in the weight percentage of Al being heat-dissipating but also thermal conductivity material causes the parameter t t improvement (r 2,5 = 0.817). It means that the inner ZrO2 layer also has a significant impact on the protective properties of the composite against contact heat. Both Al and ZrO2 have an impact on the thermal conductivity coefficient λ. However, a moderate positive correlation for Al and a negative one for ZrO2 was found.

4.3 Two-layer coating composites enriched with ZrO2

The similarity analysis (II) was carried out in order to select coating thickness that will improve the protective properties of composites. The following variables were chosen: L 1 – the ZrO2 coating thickness (denoted as ZrO2 in Table 9), L 2 – the Al coating thickness (denoted as Al in Table 9), L 3 – the thermal conductivity coefficient λ, L 4 – the threshold time t t, and L 5 – the radiant heat transfer index RHTI24. The results of the analysis are given in Table 9.

Similarity analysis (II) of BAZ composites

| Variable L i | Variable L j | D(L i , L j ) | r i,j |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al | RHTI24 | 0.18 | + |

| ZrO2 | t t | 0.67 | + |

| ZrO2 | λ | 1.21 | − |

| Al | t t | 1.38 | + |

| Al | λ | 1.61 | + |

| ZrO2 | RHTI24 | 28.60 | − |

The shortest tangent distance means the best similarity and strong linear relationship (r 2,5 = 0.984) was observed between Al coating thickness and the radiant heat transfer index RHTI24. The thickness of ZrO2 and Al coatings are also important from the point of view of improving t t. The thicker the zirconium(iv) oxide and/or Al coating, the higher the threshold time t t value, i.e., the effectiveness of composite protection against contact heat. However, the linear correlation is much stronger for ZrO2 than for Al (r 1,4 = 0.832 and r 2,4 = 0.588, respectively). The moderate impact of the ZrO2 and Al coatings thickness on the thermal conductivity was found for BAZ composites, with a negative correlation between variables λ and ZrO2 and a positive correlation between λ and Al. Compatibility between thermal conductivity and reliability in strength and heat resistance have to be ensured when using Al. It was decided that not exceeding 1.0 μm thick Al outer coating of the new composites will be considered. Therefore, three Al coating thicknesses were taken into account 0.3, 0.5, and 1.0 μm (Table 4).

It was observed that zirconium(iv) oxide coating cracks as a result of aging in ambient conditions. Thus, it was decided to enrich the inner layer of the composites. Titanium(iv) oxide inhibits the coating aging process and is characterized by a low thermal conductivity coefficient. Titanium(iv) oxide was considered in combination with zirconium(iv) oxide. It was expected that an enrichment of the composites inner layer with TiO2 would improve the resistance to contact heat. Two coating thicknesses of ZrO2 and TiO2 mixture (50/50) were taken into account: 1.0 and 2.0 μm (Table 4).

New basalt fabric-based composites, BAZT, were manufactured with the use of magnetron sputtering in accordance with the adopted assumptions regarding the coating thicknesses given in Table 4. SEM-EDS results for BAZT composites coating are shown in Table 10. The results of the thermal parameters of the composites are shown in Table 11.

Chemical composition of BAZT coatings

| Chemical element | Amount (wt%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAZT1 | BAZT2 | BAZT3 | BAZT4 | |

| Al | 13.56 | 15.71 | 38.01 | 37.74 |

| Zr | 34.07 | 50.97 | 30.72 | 9.51 |

| Ti | 21.93 | 17.53 | 17.80 | 8.68 |

| O | 23.11 | 14.90 | 9.00 | 22.89 |

| Others | 7.33 | 0.89 | 4.47 | 21.18 |

Thermal properties of BAZT composites

| Composite | BAZT1 | BAZT2 | BAZT3 | BAZT4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λ·× 10−3 (W m−1 K−1) | 36.1 | 30.7 | 39.4 | 37.5 |

| t t (s) | 6.8 | 8.4 | 7.3 | 8.3 |

| RHTI24 (s) | 22.4 | 24.5 | 25.5 | 26.0 |

Based on values of the thermal conductivity coefficients, it was stated that the thermal insulation properties of BAZT composites remained generally unchanged. It was found that the composites still had the first efficiency level (F1) of protection against contact heat. Nevertheless, the threshold time has increased, especially for BAZT2 and BAZT3. The second efficiency level (C2) of protection against radiant heat was achieved for all BAZT composites.

5 Summary and conclusions

The direct modification using the magnetron sputtering technique enables the shaping of the thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites. Two-layer basalt fabric-based composite in which the outer layer is Al and the inner layer is ZrO2 and TiO2 mixture is a good solution to obtain contact heat and radiant heat-resistant material. The inner layer of ZrO2 + TiO2, 1.0–2.0 µm thick provides good thermal insulation properties and protection against contact heat at the first efficiency level. The outer layer of Al 0.3–1.0 µm thick provides protection against radiant heat at the second efficiency level. Modified basalt fabrics can be used in material packages and composites to protect against hot factors. The authors strive to produce a composite based on basalt fabric that will be resistant to contact heat at the third efficiency level for the contact temperature of 250°C and demonstrate a higher level of protection against thermal radiation than the tested composites. Applying an additional thin layer of aerogel seems like a promising solution. This lightweight and thermal insulation material could be a flexible inner layer of a composite.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Liu, H., Yu, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, M., Li, L., Ma, L., et al. (2022). A review on basalt fiber composites and their applications in clean energy sector and power grids. Polymers, 14(12), 1–20.10.3390/polym14122376Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Fiore, V., Scalici, T., Di Bella, G., Valenza, A. (2015). A review on basalt fibre and its composites. Composites Part B: Engineering, 74, 74–94.10.1016/j.compositesb.2014.12.034Search in Google Scholar

[3] Kumbhar, V. P. (2014). An overview: Basalt rock fibers – new construction material, Acta Engineering International, 2(1), 11–18.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Jamshaid, H., Mishra, R. (2016). A green material from rock: Basalt fiber – a review. Journal of the Textile Institute, 107(7), 923–937.10.1080/00405000.2015.1071940Search in Google Scholar

[5] Hrynyk, R., Frydrych, I. (2015). Study on textile assemblies with aluminized basalt fabrics destined for protective gloves. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 27(5), 1–17.10.1108/IJCST-09-2014-0112Search in Google Scholar

[6] Zhou, Q. Q., Liang, X. P., Wang, J., Wang, H., Chen, P., Zhang, D., et al. (2016). Preparation of activated aluminum-coated basalt fiber mat for defluoridation from drinking water. Journal of Sol-Gel Science and Technology, 78(2), 331–338.10.1007/s10971-016-3970-ySearch in Google Scholar

[7] Kakar, P., Singh, A., Sheikh, J. (2023). Flame retardant finishing of textiles - A comprehensive review. Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research, 48, 475–494.10.56042/ijftr.v48i4.7662Search in Google Scholar

[8] Watson, C., Troynikov, O., Lingard, H. (2019). Design considerations for low-level risk personal protective clothing: a review. Industrial Health, 57, 306–325.10.2486/indhealth.2018-0040Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Chowdhury, I. R., Pemberton, R., Summerscales, J. (2022). Developments and industrial applications of basalt fibre reinforced composite materials. Journal of Composites Science, 6(12), 1–26.10.3390/jcs6120367Search in Google Scholar

[10] Li, Z., Ma, J., Ma, H., Xu, X. (2018). Properties and applications of basalt fiber and its composites. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 186, 1–7.10.1088/1755-1315/186/2/012052Search in Google Scholar

[11] Chelliah, A. (2019). Mechanical properties and abrasive wear of different weight percentage of TiC filled basalt fabric reinforced epoxy composites. Materials Research, 22(2), 1–8.10.1590/1980-5373-mr-2018-0431Search in Google Scholar

[12] Wei, Q. F., Huang, F. L., Hou, D. Y., Wang, Y. Y. (2006). Surface functionalisation of polymer nanofibres by sputter coating of titanium dioxide. Applied Surface Science, 252(22), 7874–7877.10.1016/j.apsusc.2005.09.074Search in Google Scholar

[13] Yaman, N., Seventekin, N., Ozdogan, E., Oktem, T. (2008). Surface modification methods for improvement of adhesion to textile fibers. Textile and Apparel, 18(2), 89–93.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Mattox, D. M. (2010). Handbook of physical vapor deposition (PVD) processing. Elsevier, Amsterdam.10.1016/B978-0-8155-2037-5.00008-3Search in Google Scholar

[15] Baptista, A., Silva, F., Poeteiro, J., Miguez, J., Pitno, G. (2018). Review sputtering physical vapour deposition (PVD) coatings: A critical review on process improvement and market trend demands. Coatings, 8(11), 1–22.10.3390/coatings8110402Search in Google Scholar

[16] Miśkiewicz, P., Frydrych, I., Cichocka, A. (2022). Application of physical vapor deposition in textile industry. Autex Research Journal, 22(1), 42–54.10.2478/aut-2020-0004Search in Google Scholar

[17] Miśkiewicz, P., Tokarska, M., Frydrych, I., Makówka, M. (2021). Assessment of coating quality obtained on flame-retardant fabrics by a magnetron sputtering method. Materials, 14(6), 1–11.10.3390/ma14061348Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Wang, H. B., Wei, W. F., Wang, J. Y., Hong, J. H., Zhao, X. Y. (2008). Sputter deposition of nanostructured antibacterial silver on polypropylene non-wovens. Surface Engineering, 24(1), 70–74.10.1179/174329408X277493Search in Google Scholar

[19] Uddin, M. J., Cesano, F., Bonino, F., Bordiga, S., Spoto, G., Scarano, D., et al. (2007). Photoactive TiO2 films on cellulose fibres: synthesis and characterization. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 189(2–3), 286–294.10.1016/j.jphotochem.2007.02.015Search in Google Scholar

[20] Miśkiewicz, P., Tokarska, M., Frydrych, I., Makówka, M. (2014). Evaluation of thermal properties of certain flame-retardant fabrics modified with a magnetron sputtering method. Autex Research Journal. 2021, 21(4), 428–434.10.2478/aut-2020-0038Search in Google Scholar

[21] Ziaja, J., Koprowska, J., Janukiewicz, J. (2008). Using plasma metallisation for manufacture of textile screens against electromagnetic fields. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 16(5), 64–66.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Zhai, Y., Liu, X., Xiao, L. (2015). Magnetron sputtering coating of protective fabric study on influence of thermal properties. Journal of Textile Science and Technology, 1(3), 127–134.10.4236/jtst.2015.13014Search in Google Scholar

[23] Han, H. R., Kim, J. J. (2017). A study on the thermal and physical properties of nylon fabric treated by metal sputtering (Al, Cu, Ni). Textile Research Journal, 88(21), 2397–2414.10.1177/0040517517731662Search in Google Scholar

[24] Han, H. R, Park, Y., Yun, Ch, Park, Ch. H. (2018). Heat transfer characteristics of aluminum sputtered fabrics. Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics, 13(3), 37–44.10.1177/155892501801300305Search in Google Scholar

[25] Miśkiewicz, P., Frydrych, I., Pawlak, W. (2019). The influence of basalt fabrics modifications on their resistance to contact heat and comfort properties. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology, 31(6), 874–886.10.1108/IJCST-11-2018-0147Search in Google Scholar

[26] Miśkiewicz, P., Frydrych, I., Makówka, M. (2020). Examination of selected thermal properties of basalt composites. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 28(2), 103–109.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Azomaterials https://www.azom.com (Accessed on 05.01.2024).Search in Google Scholar

[28] Wei, Q. (Ed.). (2014). Surface modification of textiles, Woodhead, Sawston, England.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Goldstein, J. I., Newbury, D. E., Michael, J. R., Ritchie, N. W. M., Scott, J. H. J., Joy, D. C. (2018). Scanning electron microscopy and X-ray microanalysis (4th ed.). Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands.10.1007/978-1-4939-6676-9Search in Google Scholar

[30] Matusiak, M. (2006). Investigation of the thermal insulation properties of multilayer textiles. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe, 14(5), 98–102.Search in Google Scholar

[31] ISO 12127-1. Clothing for protection against heat and flame – determination of contact heat transmission through protective clothing or constituent materials – Part 1: contact heat produced by heating cylinder, 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[32] ISO 11612. Protective clothing – clothing to protect against heat and flame – minimum performance requirements, 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[33] ISO 6942. Protective clothing – protection against heat and fire – method of test: evaluation of materials and materials assemblies when exposed to a source of radiant heat, 2022.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Duda, R. O., Hart, P. E., Stork, D. G. (2000). Pattern classification (2nd ed.). Wiley, Hoboken.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Chen, Y., Garcia, E. K., Gupta, M. R., Rahimi, A., Cazzanti, L. (2009). Similarity-based classification: Concepts and algorithms. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 10(12), 747–776.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 by the authors, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Characterization of viscoelastic properties of yarn materials: Dynamic mechanical analysis in the transversal direction

- Analysis of omni-channel implementations that are preferred by consumers in clothing sector

- Structural modeling and analysis of three-dimensional cross-linked braided preforms

- An experimental study of mechanical properties and comfortability of knitted imitation woven shirt fabrics

- Technology integration to promote circular economy transformation of the garment industry: a systematic literature review

- Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks

- Research on She nationality clothing recognition based on color feature fusion with PSO-SVM

- Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves

- Preparation and performance of stainless steel fiber/Lyocell fiber-blended weft-knitted fabric

- Development of an emotional response model for hospital gown design using structural equation modeling

- Preparation and properties of stainless steel filament/pure cotton woven fabric

- Facemask comfort enhancement with graphene oxide from recovered carbon waste tyres

- Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials

- Optical-related properties and characterization of some textile fibers using near-infrared spectroscopy

- Network modeling of aesthetic effect for Chinese Yue Opera costume simulation images

- Predicting consumers’ garment fit satisfactions by using machine learning

- Non-destructive identification of wool and cashmere fibers based on improved LDA using NIR spectroscopy

- Study on the relationship between structure and moisturizing performance of seamless knitted fabrics of protein fibers for autumn and winter

- Antibacterial and yellowing performances of sports underwear fabric with polyamide/silver ion polyurethane filaments

- Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics

- Phonetic smart clothing design based on gender awareness education for preschoolers

- Determination of anthropometric measurements and their application in the development of clothing sizing systems for women in the regions of the Republic of Croatia

- Research on optimal design of pleated cheongsam based on Kano–HOQ–Pugh model

- Numerical investigation of weaving machine heald shaft new design using composite material to improve its performance

- Corrigendum to “Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials”

- Shaping of thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites by direct surface modification using magnetron sputtering technique

- Numerical modeling of the heat flow component of the composite developed on the basis of basalt fabric

- Weft insertion guideway design based on high-temperature superconducting levitation

- Ultrasonic-assisted alkali hydrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate fabric and its effect on the microstructure and dyeing properties of fibers

- Comparative study on physical properties of bio-based PA56 fibers and wearability of their fabrics

- Investigation of the bias tape roll change time efficiency in garment factories

- Analysis of foot 3D scans of boys from Polish population

- Optimization of garment sewing operation standard minute value prediction using an IPSO-BP neural network

- Influence of repeated switching of current through contacts made of electroconductive fabrics on their resistance

- Numerical calculation of air permeability of warp-knitted jacquard spacer shoe-upper materials based on CFD

- Compact Spinning with Different Fibre Types: An Experimental Investigation on Yarn Properties in the Condensing Zone with 3D-Printed Guiding Device

- Modeling of virtual clothing and its contact with the human body

- Advances in personalized modelling and virtual display of ethnic clothing for intelligent customization

- Investigation of weave influence on flame retardancy of jute fabrics

- Balloonless spinning spindle head shape optimisation

- Research on 3D simulation design and dynamic virtual display of clothing flexible body

- Turkish textile and clothing SMEs: Importance of organizational learning, digitalization, and internationalization

- Corrigendum To: “Washing characterization of compression socks”

- Study on the promotion multiple of blood flow velocity on human epidermal microcirculation of volcanic rock polymer fiber seamless knitted fabric

- Bending properties and numerical analysis of nonorthogonal woven composites

- Bringing the queen mother of the west to life: Digital reconstruction and analysis of Taoist Celestial Beings Worshiping mural’s apparel

- Modeling process for full forming sports underwear

- Retraction of: Ionic crosslinking of cotton

- An observational study of female body shape characteristics in multiracial Malaysia

- Study on theoretical model and actual deformation of weft-knitted transfer loop based on particle constraint

- Design and 3D simulation of weft-knitted jacquard plush fabrics

- An overview of technological challenges in implementing the digital product passport in the textile and clothing industry

- Understanding and addressing the water footprint in the textile sector: A review

- Determinants of location changes in the clothing industry in Poland

- Influence of cam profile errors in a modulator on the dynamic response of the heald frame

- Quantitative analysis of wool and cashmere fiber mixtures using NIR spectroscopy

- 3D simulation of double-needle bar warp-knitted clustered pile fabrics on DFS

- Finite element analysis of heat transfer behavior in glass fiber/metal composite materials under constant heat load

- Price estimation and visual evaluation of actual white fabrics used for dress shirts and their photographic images

- Effect of gluing garment materials with adhesive inserts on their multidirectional drape and bending rigidity

- Optimization analysis of carrier-track collision in braiding process

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the ballistic performance of soft bulletproof vests for women

- The antimicrobial potential of plant-based natural dyes for textile dyeing: A systematic review using prisma

- Influence of sewing parameters on the skin–fabric friction

- Validation by experimental study the relationship between fabric tensile strength and weave structures

- Optimization of fabric’s tensile strength and bagging deformation using surface response and finite element in stenter machine

- Analysis of lean manufacturing waste in the process flow of ready-to-wear garment production in Nigeria

- An optimization study on the sol–gel process to obtain multifunctional denim fabrics

- Drape test of fully formed knitted flared skirts based on 3D-printed human body posture

- Supplier selection models using fuzzy hybrid methods in the clothing textile industry

Articles in the same Issue

- Characterization of viscoelastic properties of yarn materials: Dynamic mechanical analysis in the transversal direction

- Analysis of omni-channel implementations that are preferred by consumers in clothing sector

- Structural modeling and analysis of three-dimensional cross-linked braided preforms

- An experimental study of mechanical properties and comfortability of knitted imitation woven shirt fabrics

- Technology integration to promote circular economy transformation of the garment industry: a systematic literature review

- Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks

- Research on She nationality clothing recognition based on color feature fusion with PSO-SVM

- Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves

- Preparation and performance of stainless steel fiber/Lyocell fiber-blended weft-knitted fabric

- Development of an emotional response model for hospital gown design using structural equation modeling

- Preparation and properties of stainless steel filament/pure cotton woven fabric

- Facemask comfort enhancement with graphene oxide from recovered carbon waste tyres

- Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials

- Optical-related properties and characterization of some textile fibers using near-infrared spectroscopy

- Network modeling of aesthetic effect for Chinese Yue Opera costume simulation images

- Predicting consumers’ garment fit satisfactions by using machine learning

- Non-destructive identification of wool and cashmere fibers based on improved LDA using NIR spectroscopy

- Study on the relationship between structure and moisturizing performance of seamless knitted fabrics of protein fibers for autumn and winter

- Antibacterial and yellowing performances of sports underwear fabric with polyamide/silver ion polyurethane filaments

- Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics

- Phonetic smart clothing design based on gender awareness education for preschoolers

- Determination of anthropometric measurements and their application in the development of clothing sizing systems for women in the regions of the Republic of Croatia

- Research on optimal design of pleated cheongsam based on Kano–HOQ–Pugh model

- Numerical investigation of weaving machine heald shaft new design using composite material to improve its performance

- Corrigendum to “Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials”

- Shaping of thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites by direct surface modification using magnetron sputtering technique

- Numerical modeling of the heat flow component of the composite developed on the basis of basalt fabric

- Weft insertion guideway design based on high-temperature superconducting levitation

- Ultrasonic-assisted alkali hydrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate fabric and its effect on the microstructure and dyeing properties of fibers

- Comparative study on physical properties of bio-based PA56 fibers and wearability of their fabrics

- Investigation of the bias tape roll change time efficiency in garment factories

- Analysis of foot 3D scans of boys from Polish population

- Optimization of garment sewing operation standard minute value prediction using an IPSO-BP neural network

- Influence of repeated switching of current through contacts made of electroconductive fabrics on their resistance

- Numerical calculation of air permeability of warp-knitted jacquard spacer shoe-upper materials based on CFD

- Compact Spinning with Different Fibre Types: An Experimental Investigation on Yarn Properties in the Condensing Zone with 3D-Printed Guiding Device

- Modeling of virtual clothing and its contact with the human body

- Advances in personalized modelling and virtual display of ethnic clothing for intelligent customization

- Investigation of weave influence on flame retardancy of jute fabrics

- Balloonless spinning spindle head shape optimisation

- Research on 3D simulation design and dynamic virtual display of clothing flexible body

- Turkish textile and clothing SMEs: Importance of organizational learning, digitalization, and internationalization

- Corrigendum To: “Washing characterization of compression socks”

- Study on the promotion multiple of blood flow velocity on human epidermal microcirculation of volcanic rock polymer fiber seamless knitted fabric

- Bending properties and numerical analysis of nonorthogonal woven composites

- Bringing the queen mother of the west to life: Digital reconstruction and analysis of Taoist Celestial Beings Worshiping mural’s apparel

- Modeling process for full forming sports underwear

- Retraction of: Ionic crosslinking of cotton

- An observational study of female body shape characteristics in multiracial Malaysia

- Study on theoretical model and actual deformation of weft-knitted transfer loop based on particle constraint

- Design and 3D simulation of weft-knitted jacquard plush fabrics

- An overview of technological challenges in implementing the digital product passport in the textile and clothing industry

- Understanding and addressing the water footprint in the textile sector: A review

- Determinants of location changes in the clothing industry in Poland

- Influence of cam profile errors in a modulator on the dynamic response of the heald frame

- Quantitative analysis of wool and cashmere fiber mixtures using NIR spectroscopy

- 3D simulation of double-needle bar warp-knitted clustered pile fabrics on DFS

- Finite element analysis of heat transfer behavior in glass fiber/metal composite materials under constant heat load

- Price estimation and visual evaluation of actual white fabrics used for dress shirts and their photographic images

- Effect of gluing garment materials with adhesive inserts on their multidirectional drape and bending rigidity

- Optimization analysis of carrier-track collision in braiding process

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the ballistic performance of soft bulletproof vests for women

- The antimicrobial potential of plant-based natural dyes for textile dyeing: A systematic review using prisma

- Influence of sewing parameters on the skin–fabric friction

- Validation by experimental study the relationship between fabric tensile strength and weave structures

- Optimization of fabric’s tensile strength and bagging deformation using surface response and finite element in stenter machine

- Analysis of lean manufacturing waste in the process flow of ready-to-wear garment production in Nigeria

- An optimization study on the sol–gel process to obtain multifunctional denim fabrics

- Drape test of fully formed knitted flared skirts based on 3D-printed human body posture

- Supplier selection models using fuzzy hybrid methods in the clothing textile industry