Abstract

The current study aims to explore the representative and typical female body shapes through in-depth observation and analysis of the diversity in Malaysian female body shape characteristics across different ethnic and age groups, which assists in facilitating the establishment of accurate apparel size standards. This study was conducted in Selangor, which is the most populous and developed Malaysian state. The data were collected via a highly systematic approach. The K-mean clustering method was applied to synthesise and analyse the collected data, which classified the body types into five major clusters. The results not only revealed significant differences in the distribution of body shapes across ethnic and age groups but also highlighted the limitations of the various sizing systems currently employed by the Malaysian apparel industry to fulfil the requirements of the diverse Malaysian market. The findings provided practical implications for apparel manufacturers and retailers with concrete evidence to support improved product design and enhance customer satisfaction. A deeper understanding and categorisation of Malaysian females’ body types could also assist the apparel industry in developing more tailored sizing systems. Resultantly, an improved system minimises return rates, optimises inventory management, and supports environmental and sustainability goals by reducing overproduction.

1 Introduction

Extensive mechanisation spurred a significant transformation in the clothing industry since the nineteenth century, which signifies the commencement of an alternative era primarily focusing on mass production [1]. Clothing manufacturing was globalised after the 1950s by transferring production factories to nations with lower labour expenditures, which significantly increased worldwide production and efficiency and reinforced the industrial role as a global economic fundamental [2,3]. Accordingly, clothing consumption worldwide was projected to elevate by 63% to 102 million tonnes in 2030 [4]. Nevertheless, the apparel industry is recognised as the second largest global polluter [5], which significantly impacts environmental sustainability [6]. Increased production resulted in significant consumption rates of energy and resources and environmental pollution [7]. Moreover, 80% of garment waste globally is incinerated, which further increases the carbon footprint and the loss of energy and raw materials simultaneously [5]. The rapid change in fashion trends has also compelled the apparel industry to commit to moment-to-moment design and production. As such, overproduction has become a norm, which results in increased inventories and idle pressure due to the fast fashion trend. The dramatic increases in (fast) fashion production and consumption volumes have resulted in increasing textile waste [8]. In addition, firms and factories seek more knowledge of target customers’ body types, sizes, and preferences, which leads to the wide availability of different garment sizes. Ill-fitting garments elevate the rate of idle inventories and returns, thereby diminishing retailers’ operational efficiency [9,10].

The sustainability challenge exists in the Malaysian apparel market, which motivates more Malaysian apparel companies to pursue sustainable fashion. Start-ups, such as KANOE, Real-M, and Nukleus Wear, have demonstrated the sustainability trend [11] by actively pursuing and practising sustainable values. Nonetheless, the size and clothing fit are constant challenges, especially females’ body shapes and proportions that are significantly influenced by ethnicity and lifestyle factors. Therefore, ready-to-wear apparel is difficult to produce to cater to a diverse range of body shapes, which reduces clothing fit [12]. Sustainability is also primarily hampered by the requirement for more research on body shape and size in multi-ethnic Malaysia [13,14]. Concurrently, various clothing sizes increase online consumers’ confusion and dissatisfaction [15,16]. Based on the studies by Saaludin et al. [17], a significant number of online purchases are returned due to sizing and fit issues. Improving customer satisfaction can help reduce returns. Up to 80% of the consumers are dissatisfied with the current clothing sizes [18]. Enhancing customer satisfaction will lead to a decrease in clothing exchanges and returns [19]. Furthermore, confusion over sizing standards poses an overproduction risk, wherein manufacturers overproduce to fulfil consumers’ expectations [20]. Significant warehouse preservation and management resources will be occupied by returned and unemployed inventories, which diminish corporate cash flow while aggravating financial burdens on business development [21]. Accordingly, the present study conducted a preliminary survey on Malaysian females’ body types across five densely populated areas in Selangor to promote the sustainable development of the Malaysian clothing industry while establishing an apparel sizing system in the local context. This study seeks to systematically analyse Malaysian females’ body shape characteristics across different ethnic and age groups to provide a fundamental scientific basis for the future development of a local garment-sizing standard.

2 Methodology

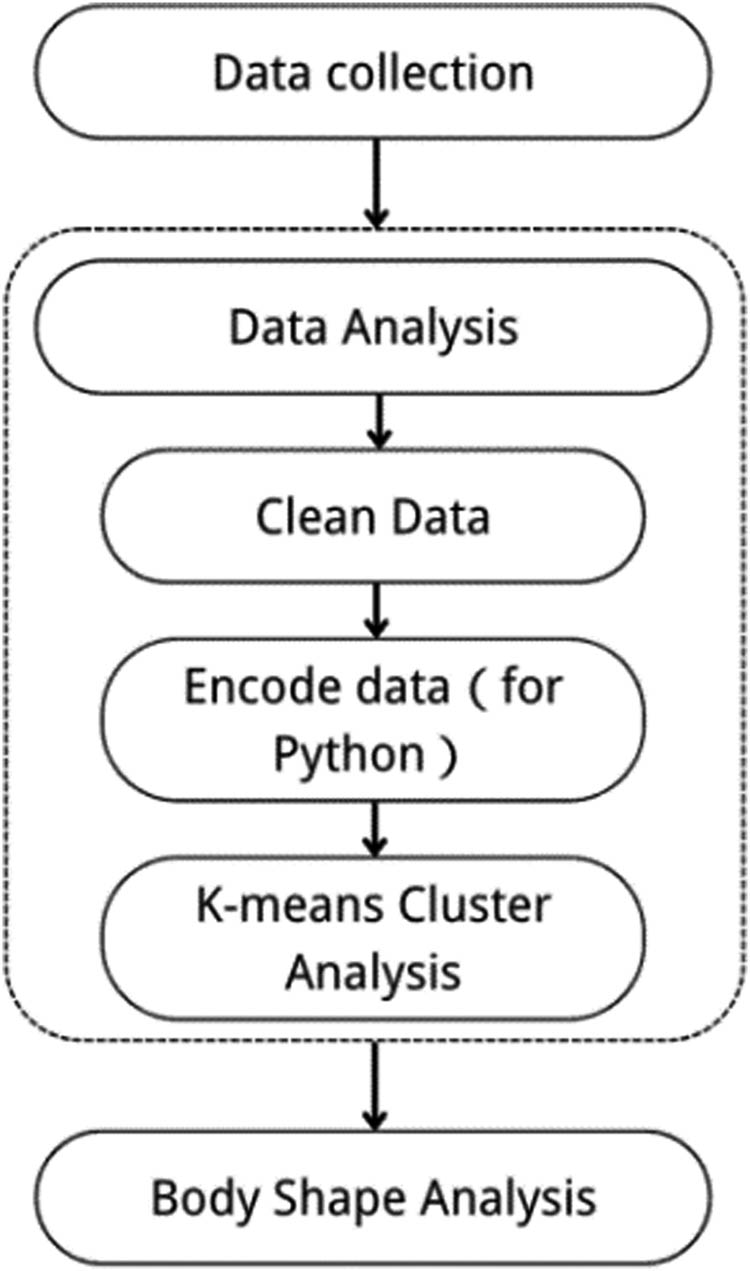

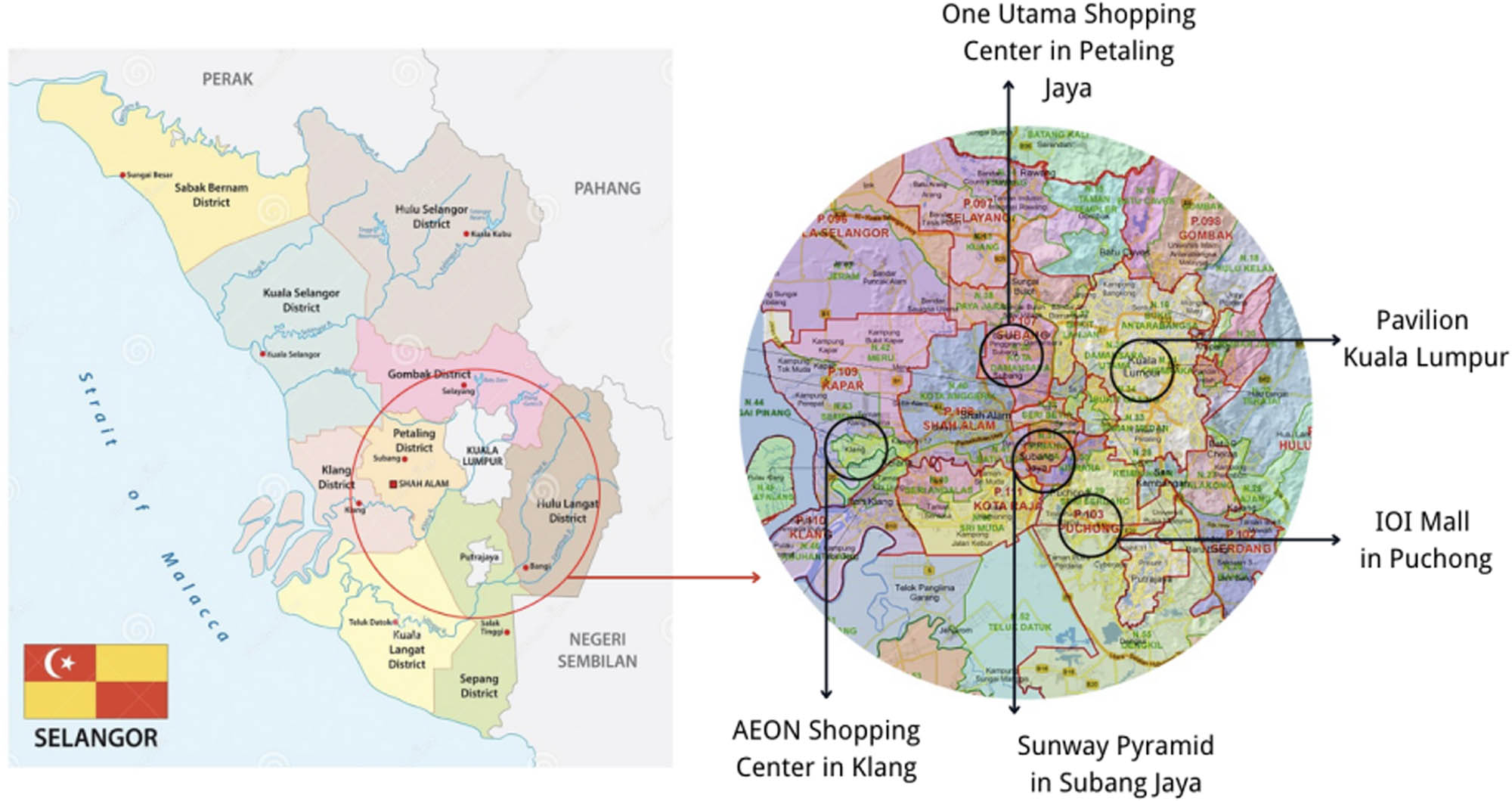

The current research process and methodology are illustrated in Figure 1. Data collection was the first step to obtain information about body shape through observations. The researcher subsequently performed data cleaning to remove inconsistent or incomplete data points. The cleaned data were required to be transformed into a Python-compatible format for coding and numerical processing. K-means cluster analysis was applied to identify different body shapes. K-means clustering was chosen as the data analysis method for this study due to its strong adaptability, ease of interpretation, and high computational efficiency. As a widely used unsupervised learning algorithm for large datasets, K-means effectively handles complex data, making it particularly suitable for identifying and classifying diverse characteristics within a varied sample [22]. Its low computational complexity allows for quick processing of large amounts of data, making it a practical choice for analysing the extensive sample sizes involved in this research. The findings revealed the characteristics and distribution among different taxonomies through the body shape analysis, which completed the scientific transformation from empirical observation to quantitative analysis. The observational survey was conducted in Selangor, which is the most populous and developed Malaysian state. Selangor is also one of the national commercial and industrial centres, which provided more employment opportunities and attracted population migration from other states and internationally. The population of Selangor was higher in quantity and density compared to other regions, with major ethnic groups, such as Malays, Chinese, Indians, and foreigners across the globe. Comparatively, multicultural integration was less common in other Malaysian states. Therefore, the researcher selected popular business districts in several major cities of Selangor, including Pavilion Kuala Lumpur, One Utama Shopping Centre in Petaling Jaya, AEON Shopping Centre in Klang, Sunway Pyramid in Subang Jaya, and IOI Mall in Puchong, for random and anonymous observations. The exact distribution is depicted in Figure 2.

Observational survey process.

Sampling locations in Selangor.

Three indicators were employed to comprehensively describe Malaysian females’ body shapes, namely the body type, body shape, and body proportion. The body type (somatotypes) developed by Dr W.H. Sheldon in the early 1940s categorises human body compositions into three distinct types, namely endomorph, mesomorph, and ectomorph [23]. Endomorphs tend to accumulate more weight and fat while displaying less pronounced muscularity with a rounded body shape and broader waist. Ectomorphs are generally lean with minimal muscular definition and low fat levels. Mesomorphs represent an intermediate body type. The body shape classification is more refined than that of the body type by focusing on the visual features. Different descriptions of visual classification are available on the internet (Table 1), and the researcher concluded seven visually distinct body shapes. The body proportion, which includes long (L) and short torso (S), is a set of descriptive terms in the field of fashion and fitness referring to the relative length of an individual’s torso to the legs and overall height. The data were analysed and processed after collating the collected data. Data cleansing was performed on the raw data by removing blank data and merging overlapping age groups. The original data were required to be coded before data analysis as the original data were strings and could not be analysed in the Python programming environment. Thus, recoding was performed for each variable.

Body shape descriptions

| Body shape | Description |

|---|---|

| Apple (A) | Focuses on fat accumulation in the abdomen, with the upper body being more prominent than the lower half. Generally with a larger chest, waist, and relatively thin arms and legs |

| Pear (P) | Hips and thighs are wider than shoulders and chest. Fats primarily accumulate in the lower body, especially in the hips and thighs |

| Hourglass (H) | The chest and hips are roughly equal in width, and the waist is significantly smaller. This body shape is characterised by distinct curves |

| Rectangle (R) | The shoulders, waist, and hips are roughly equal in width, and the body shape is visually straight and even. The waistline is less visible |

| Inverted triangle (IT) | The shoulders are wider than the hips. This shape is characterised by a more pronounced upper body than the lower body with broader shoulders and smaller hips |

| Diamond (D) | The waist is the widest body part, the chest and hips are relatively narrow, and the hips may be slightly wider than the shoulders. Common in middle-aged and older individuals |

| Oval (O) | The middle of the body is wider than the shoulders and hips. Similar to an apple shape but with a more rounded overall profile |

Weights were required to be attached to each sample in the Python environment before the data could be analysed due to the differences in the population size between different ethnic groups. The ethnic distribution of the Malaysian population was Malay (M) at 70.1%, Chinese (C) at 22.6%, Indians (I) at 6.6%, and Others (O) at 0.7%. Subsequently, the weighting coefficient was calculated by dividing the overall proportion by the sample proportion through the following formula:

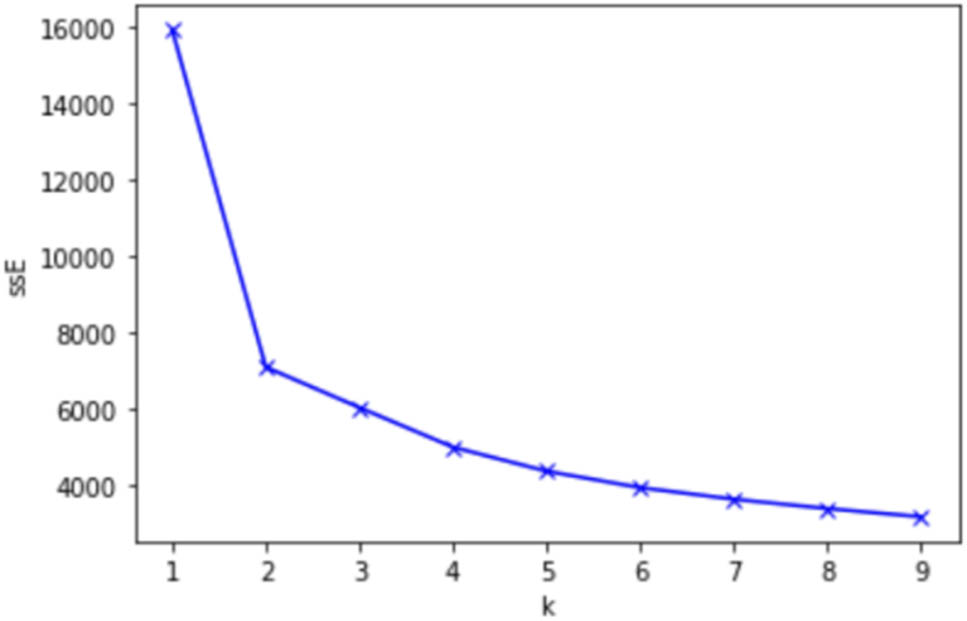

The weighting coefficients for each ethnic group were obtained, namely Malay (M) at 2.05, Chinese (C) at 0.52, Indians (I) at 0.35, and Others (O) at 0.18. The weighting coefficients represented the relationships between the relative proportions of each ethnic group in the sample and the actual proportions. Specifically, the Malay (M) sample was required to be weighted by a factor of 2.05. The Chinese (C) sample attained a weight of 0.52, which propounded that the Chinese data were over-represented and required to be down-weighted. The Indian (I) sample obtained a weight of 0.35, which suggested the need to be down-weighted. The Other (O) sample contained a weight of 0.18, which was required to be down-weighted. The recorded data were imported into the Python environment. The elbow method was utilised to determine the K value in the subsequent K-means cluster analysis. Figure 3 portrays the elbow plot.

The elbow plot.

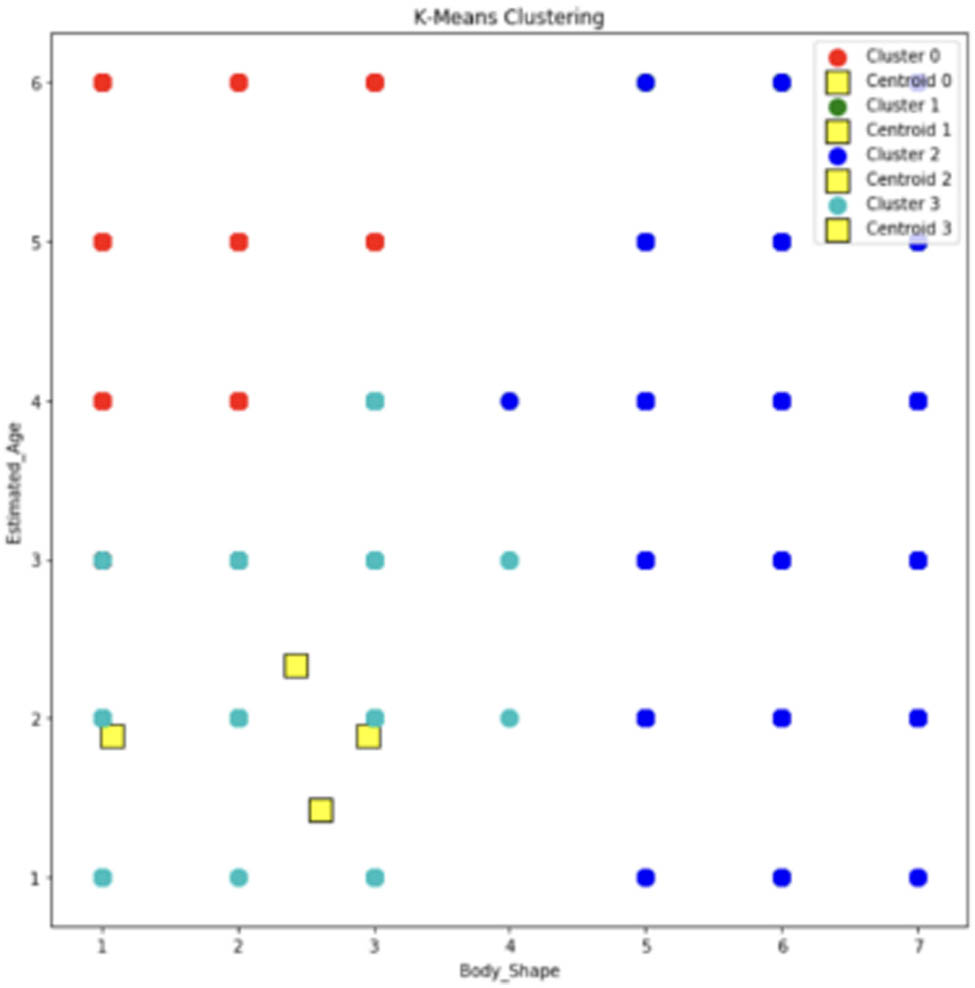

The elbow rule was applied to assess clustering effectiveness and analyse the variation of the K-mean clustering sum of squared errors (SSE) with the number of clusters (K). The SSE was determined by the number of clusters. The SSE value gradually decreased from K = 1 to K = 9, and elbow points were recognised as places where the SSE decrease tended to decelerate, which posited that including more clustering centres would diminish marginal effectiveness. The deceleration of the decline in SSE was more apparent at K = 3 despite one significant change at K = 4. K = 4 demonstrated a significant decrease in SSE, which led to the selection of K = 4 as the number of clusters. The preliminary K-means cluster analysis encompassed “nationality,” “body type,” “body shape,” “body proportion,” and “estimated age,” which resulted in four clusters and a K-means clustering scatter plot (Figure 4). Interpretations of the clustering results were conducted with the four most common body type combinations:

Scatter plot when K = 4.

Cluster 0: MEnDL: Malay, endomorph, diamond shape, and long torso.

Cluster 1: AMePS: Chinese, mesomorph, pear, and short torso.

Cluster 2: MMePS: Malay, mesomorph, pear, and short torso.

Cluster 3: IMeHS: Indian, mesomorph, hourglasses, and short torso.

The scatter plot illustrated that the data points in Cluster 1 were not displayed as the number of data points within this group might be insignificant or was covered by data points from other categories. As such, data points from this category might overlap with data points from other categories, which resulted in being indistinguishable.

The researcher postulated that the clustering approach could not depict the comprehensiveness of female body types in Malaysia, which is a multiracial country. The current study sought to holistically appraise the body shapes of Malaysian females. The four categories in the preliminary clustering results could not reveal key indicators of the body type and shape. A significant difference existed in the proportion of the initial clustering variable “ethnic,” which was weighted and significantly impacted the clustering results. Hence, the variable should be excluded from clustering. In addition, the variable “estimated age” could render errors, which should be excluded as a variable that tended to reduce clustering accuracy. Subsequently, the researcher increased the K value for stepwise testing to guide the factor “body type” to be fully presented. Resultantly, a full body type classification was obtained at K = 8, which statistically classified the body types into endomorph, ectomorph, and mesomorph, respectively, to illustrate the full range.

3 Results

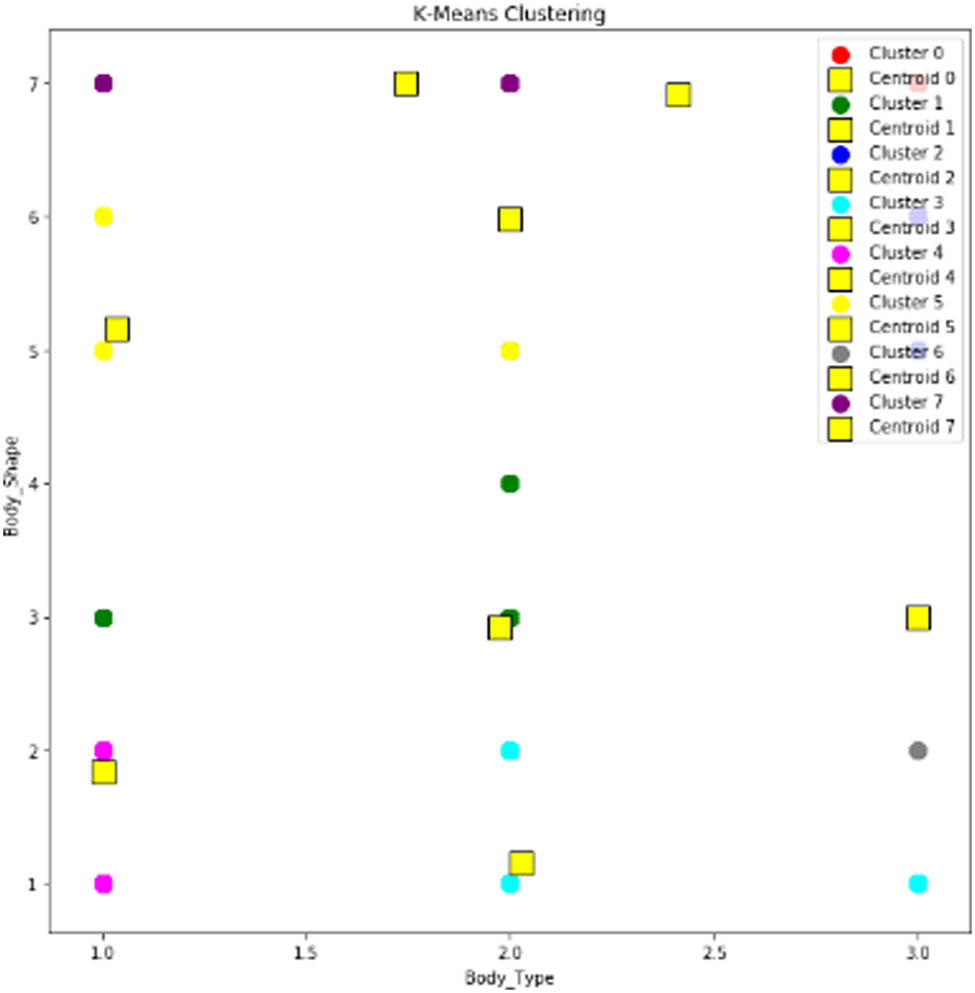

Figure 5 demonstrates the scatter plot obtained at K = 8. Interpretations of the clustering results were performed with a total of eight body type combinations:

Scatter plot when K = 8.

Cluster 0: EnOS: endomorph, oval shape, and short torso;

Cluster 1: MeAS: mesomorph, apple shape, and short torso;

Cluster 2: MeRS: mesomorph, rectangular shape, and short torso;

Cluster 3: MeHS: mesomorph, hourglass shape, and short torso;

Cluster 4: MePS: mesomorph, pear shape, and short torso;

Cluster 5: EnDS: endomorph, diamond shape, and short torso;

Cluster 6: EcHS: ectomorph, hourglass shape, and short torso;

Cluster 7: MeRL: mesomorph, rectangular shape, and long torso.

4 Findings and discussion

Table 2 demonstrates the proportion of each cluster in the sample. Cluster 2 (MeRS) accounted for the largest proportion (23.83%), which indicated that the short torso of the mesomorph with a rectangular shape was the most common in the sample. Cluster 7 (MeRL) accounted for the second largest proportion (15.75%), which highlighted that the long torso of the mesomorph with a rectangular shape was also relatively common. Thus, the overall rectangular shape of the mesomorph was the most common in the sample (39.58%). Cluster 0 (EnOS) and Cluster 5 (EnDS) could be summarised as a synthetic category of body types due to the similarity between oval and diamond shapes, which collectively accounted for 16.3% of the total sample. Moreover, the oval shape could be considered an endomorph and the second most common body type trait in the sample. The third most common body type was Cluster 1 (MeAS), which was a mesomorph with an apple shape and a long torso. Cluster 4 (MePS) accounted for more than 10% of the sample, which exhibited the long torsos of mesomorphs with pear shapes. The remaining two categories, namely Clusters 3 and 6, accounted for 18.96% of the sample, and the commonality was the hourglass shape. In addition, the data revealed that long-torso individuals only appeared in Cluster 7, which accounted for 15.75% of the total sample and indicated that the overall proportion of a long torso was relatively small. Summarily, the results discovered five clusters of the body shape characteristics, namely a rectangular body shape for mesomorphs with short and long torsos (MeRS/L), an oval body shape for endomorphs with short torsos (EnOS), an apple shape for mesomorphs with short torsos (MeAS), and an hourglass shape for mesomorph or ectomorph body types with short torsos (Me/EcHS; Table 3).

Percentage and count of each cluster

| Cluster | Percentage | Count |

|---|---|---|

| 0 (EnOS) | 9.00 | 196 |

| 1 (MeAS) | 15.06 | 328 |

| 2 (MeRS) | 23.83 | 519 |

| 3 (MeHS) | 9.92 | 216 |

| 4 (MePS) | 10.10 | 220 |

| 5 (EnDS) | 7.30 | 159 |

| 6 (EcHS) | 9.04 | 197 |

| 7 (MeRL) | 15.75 | 343 |

| Sum | 100.00 | 2,178 |

Percentage and count of five typical body shapes

| Order | Cluster | Typical body shape | Percentage | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 (MeRS) + 7 (MeRL) | MeRS/L | 39.58 | 862 |

| 2 | 3 (MeHS) + 6 (EcHS) | Me/EcHS | 18.96 | 413 |

| 3 | 0 (EnOS) + 5 (EnDS) | EnOS | 16.30 | 355 |

| 4 | 1 (MeAS) | MeAS | 15.06 | 328 |

| 5 | 4 (MePS) | MePS | 10.10 | 220 |

| Sum | 100.00 | 2,178 | ||

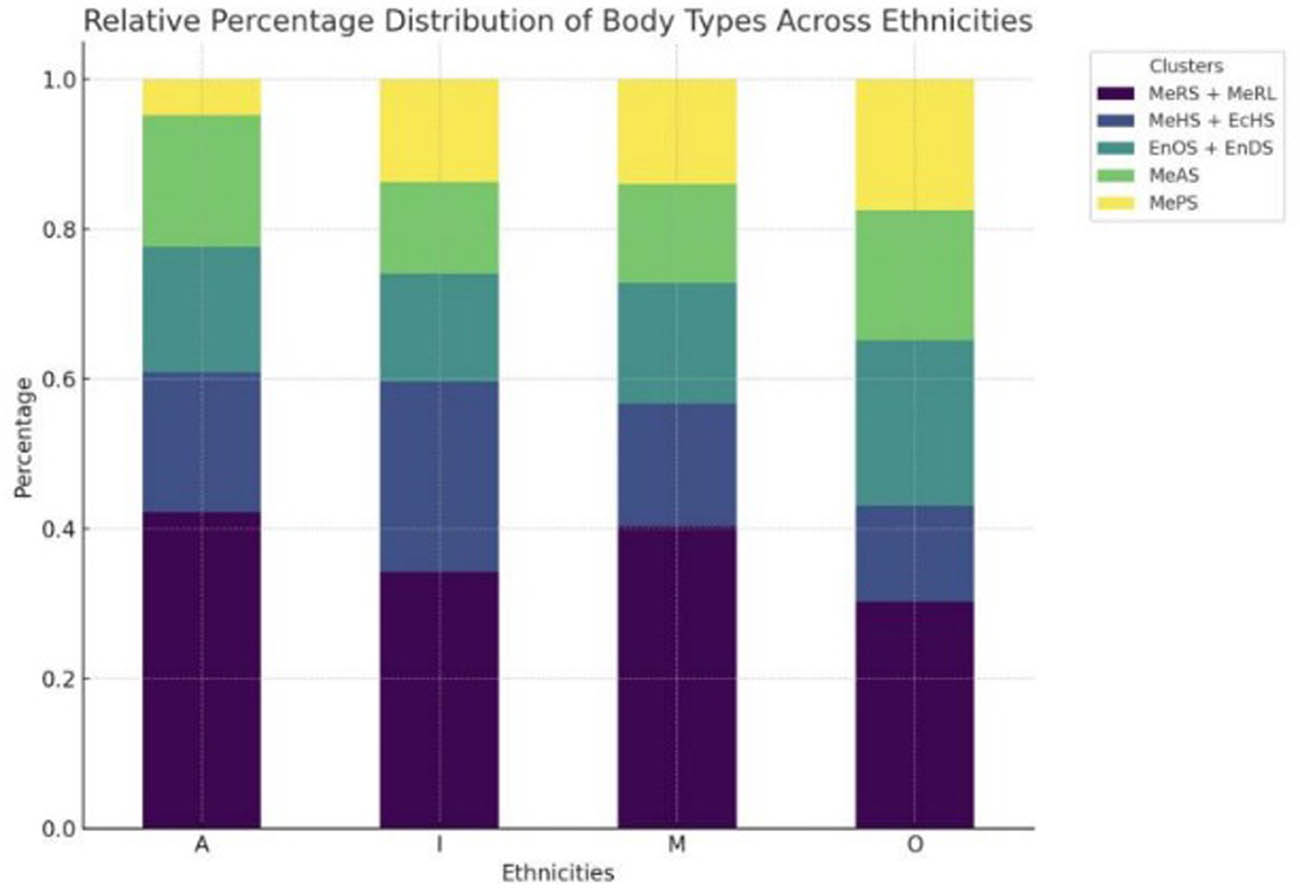

Table 4 illustrates the proportion of the five clusters between ethnic groups, with the distribution of each cluster between different ethnic groups being observed more visually in the stacked diagram (Figure 6). Particularly, the most significant portion of the Chinese group was dark blue, which represented “MeRS + MeRL” (mesomorph, rectangular body shape, and long or short torso) at 42.2%. These findings suggested that this combination of body types was prevalent in the Chinese community. The lighter blue section represented “MeHS + EcHS” (mesomorph, hourglass body shape, and short torso) at 18.65%. The “MeRS + MeRL” was also the body type combination with the highest percentage in the Indian group but slightly lower than the Chinese group at 34.14%, followed by “MeHS + EcHS” at 25.35%. The “MeRS + MeRL” (mesomorph, rectangular body shape, and long or short torso) at 40.32% was the most predominant body type combination similar to the distribution in the Chinese group. The “MeRS + MeRL” (mesomorph, rectangular body type, and long or short torso) in other cohorts also accounted for the largest proportion at 30.23%, whereas the “EnOS + EnDS” (endomorph, oval or diamond body type, and short torso) accounting for 22.09% was relatively high in the other group.

Percentage of five typical body shapes in each ethnic group

| Order | Cluster | Percentage in each ethnic group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | I | M | O | ||

| 1 | 2 (MeRS) + 7 (MeRL) | 42.22 | 34.14 | 40.32 | 30.23 |

| 2 | 3 (MeHS) + 6 (EcHS) | 18.65 | 25.35 | 16.39 | 12.79 |

| 3 | 0 (EnOS) + 5 (EnDS) | 16.74 | 14.39 | 16.13 | 22.09 |

| 4 | 1 (MeAS) | 17.59 | 12.20 | 13.17 | 17.44 |

| 5 | 4 (MePS) | 4.80 | 13.66 | 13.98 | 17.44 |

| Sum | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

Stacked diagram of five typical body shapes in different ethnic groups.

Table 5 portrays the hourglass body shape (mesomorphs and ectomorphs, Cluster 2: MeHS + EcHS) dominates in the younger female group (18–27 years old), which demonstrates that younger females possess a more optimal physique. Meanwhile, different trends existed in the mature age groups (28–37 and 38–47 years old), wherein mesomorph or rectangular (Cluster 1: MeRS + MeRL) and oval or diamond body shapes (Cluster 3: EnOS + EnDS) were more prevalent. The results postulated the prevalence of endomorphs among middle-aged females. Furthermore, apple and pear-shaped body shapes (Cluster 4: MeAS and Cluster 5: MePS) were relatively more in this age group. Clusters 2 (18–27 years old) and 3 (28–37 years old) contributed the highest proportions of the total sample, which propounded that females from the two age groups were more frequently observed in commercial areas. The females would also be more inclined to perform clothing purchases with a higher demand for appropriate clothing sizes and fit. Summarily, the Malaysian population contained diverse body types with certain variations across different age and ethnic groups. The distribution of the five body shape categories posited distinctive social and biological characteristics across different age and ethnic groups.

Count of five typical body shapes in each age group

| Order | Cluster | Count in each estimated age group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| (0–17) | (18–27) | (28–37) | (38–47) | (48–57) | (58∼) | ||

| 1 | 2 (MeRS) + 7 (MeRL) | 7 | 124 | 385 | 289 | 106 | 12 |

| 2 | 3 (MeHS) + 6 (EcHS) | 18 | 177 | 83 | 92 | 17 | 26 |

| 3 | 0 (EnOS) + 5 (EnDS) | 11 | 114 | 92 | 96 | 18 | 24 |

| 4 | 1 (MeAS) | 2 | 110 | 138 | 54 | 15 | 8 |

| 5 | 4 (MePS) | 0 | 12 | 95 | 79 | 14 | 2 |

| Sum | 38 | 537 | 793 | 610 | 170 | 72 | |

The mesomorph or rectangular (MeRS/L) body shape was predominant in all ethnic groups, with a significantly high prevalence among Chinese and Malays. The rectangular physique is roughly equal in width at the shoulders, waist, and hips, which is common among middle-aged females and indicates a certain degree of abdominal obesity. An hourglass-shaped physique (Me/EcHS) of a mesomorph body is characterised by roughly equal widths at the chest and hips and a significantly smaller waist, which is common in the younger female population. The oval and diamond-shaped physique of an endomorph (EnOS) is characterised by a larger body from the waist to the hips, which can be the widest at the waist or hips. Specifically, the findings demonstrated that the age distribution was between 18 and 47 years old, which underscored widespread obesity among Malaysian adult women. The apple-shaped physique (MeAS) of a mesomorph is characterised by abdominal obesity, a broader chest, and thinner limbs, which is common among middle-aged groups of various ethnicities in Malaysia. The mesomorph or pear-shaped physique (MePS) is characterised by wider hips and thighs than the shoulders, with fats primarily accumulating in the lower body. This body type was discovered in all age groups among adult females. In addition, the pear-shaped figure transitioned to a diamond or oval shape as weight increased.

5 Limitations

In this study, although an anonymous random sampling method was employed, there may be some imbalance in the representativeness of the sample within the context of a diverse population. As a multi-ethnic nation, Malaysia exhibits significant differences in body shape characteristics across various ethnic groups, and the current sampling method may not fully capture this diversity. This could introduce bias in the comparison of body shapes among different ethnic groups, potentially affecting the generalisability of the research findings.

Additionally, while the study utilised weighting coefficients to adjust the data and improve the accuracy of the results – correcting the sample proportions to better align with the actual population distribution among different ethnic groups – this adjustment method could also introduce certain issues. For example, after applying the weighting, some ethnic groups’ samples might exert an outsized influence on the analysis, potentially leading to bias in the clustering results. Future research could explore more refined weighting methods and aim to achieve a more balanced sample collection strategy, reducing reliance on such adjustments, and enhancing the stability and reliability of the results.

Furthermore, the data collection in this study was limited to several major commercial areas in Selangor, which may restrict the broader applicability of the research findings. Although Selangor is one of the most prosperous regions in Malaysia, the body shape characteristics of its residents may not fully reflect those of women across the entire country. Therefore, there may be limitations in generalising the findings to a national scale. To improve the generalisability and representativeness of the results, future studies should consider expanding the geographical scope of data collection.

6 Conclusion

This study employed K-means cluster analysis to observe and classify the body shapes of Malaysian women, identifying five primary body types: MeRS/L (a rectangular shape for mesomorphs with short or long torsos), Me/EcHS (an hourglass shape for mesomorph or ectomorph body types with short torsos), EnOS (an oval shape for endomorphs with short torsos), MeAS (an apple shape for mesomorphs with short torsos), and MePS (a pear shape for mesomorphs with short torsos). The research also explored the distribution of these body types across different ethnic groups and age ranges in Malaysia. This detailed classification provides crucial references for the Malaysian apparel industry in sizing and design, helping companies better understand the diversity of Malaysian women’s body shapes. By uncovering these body shape characteristics and their distribution patterns, this preliminary research offers a scientific basis for the future development of more targeted sizing standards, thereby reducing return rates due to improper sizing, enhancing customer satisfaction, and improving corporate profitability. It also lays the foundation for the development of future sizing systems and sustainable development.

At the same time, the research findings support the sustainable development goals of the apparel industry. By analysing the differences in body shape characteristics, the study provides customised information support for clothing design and production, enabling companies to optimise production processes, reduce overproduction and inventory backlogs, and thus decrease waste and environmental burden.

Additionally, the body shape patterns and trends discovered in this study provide a solid foundation for the development of market segmentation strategies. Apparel brands can use this information to develop more targeted product lines to meet the needs of consumers from different ethnic groups and age ranges. This refined market segmentation strategy not only helps to enhance brand competitiveness but also increases customer loyalty, driving the long-term growth of enterprises.

Overall, this study provides significant theoretical and practical support for the Malaysian apparel industry in terms of sizing standardisation, sustainable development, and market segmentation, promoting substantial progress in the industry.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the Changzhou Vocational Institute of Textile and Garment for providing financial support during the PhD period.

-

Funding information: The research was financially supported by Changzhou Vocational Institute of Textile and Garment.

-

Author contributions: Wang Yiyan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft, Data Collection, Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing. Norsaadah Zakaria: Supervision.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Majumder, P. (2015). Mass production in the garment industry: a case study of a ready-made garment factory in Bangladesh. The Journal of Developing Areas, 49, 85–102.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Arrigo, E. (2020). Global sourcing in fast fashion retailers: sourcing locations and sustainability considerations. Sustainability, 12(2), 508.10.3390/su12020508Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gazzola, P., Pavione, E., Pezzetti, R., Grechi, D. (2020). Trends in the fashion industry. The perception of sustainability and circular economy: a gender/generation quantitative approach. Sustainability, 12, 2809.10.3390/su12072809Search in Google Scholar

[4] Sumo, P. D., Arhin, I., Danquah, R., Nelson, S. K., Achaa, L. O., Nweze, C. N., et al. (2023). An assessment of Africa’s second-hand clothing value chain: a systematic review and research opportunities. Textile Research Journal, 93(19–20), 4701–4719.10.1177/00405175231175057Search in Google Scholar

[5] de Aguiar Hugo, A., de Nadae, J., da Silva Lima, R. (2021). Can fashion be circular? A literature review on circular economy barriers, drivers, and practices in the fashion industry’s productive chain. Sustainability, 13(21), 12246.10.3390/su132112246Search in Google Scholar

[6] Richardson-Moore, E. (2023). Dressing up the truth: fast fashion’s environmental consequences. https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/global-social-challenges/2023/12/20/dressing-up-the-truth-fast-fashions-environmental-consequences/.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Geissdoerfer, G., Savaget, P., Bocken, N. M. P., Hultink, E. J. (2017). The circular economy – a new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production, 143, 757–768.10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.048Search in Google Scholar

[8] Niinimäki, K., Peters, G., Dahlbo, H., Perry, P., Rissanen, T., Gwilt, A. (2020). The environmental price of fast fashion. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 1(4), 189–200.10.1038/s43017-020-0039-9Search in Google Scholar

[9] Wolff, K., Herholz, P., Ziegler, V., Link, F., Brügel, N., Sorkine-Hornung, O. (2021). 3D custom fit garment design with body movement. arXiv.org. Web site: https://arxiv.org.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Nestler, A., Karessli, N., Hajjar, K., Shirvany, R. (2021, August). SizeFlags: reducing size and fit related returns in fashion e-commerce. In KDD ‘21: The 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining.10.1145/3447548.3467160Search in Google Scholar

[11] Hasbullah, N. N., Sulaiman, Z., Mas’od, A., Ahmad Sugiran, H. S. (2022). Drivers of sustainable apparel purchase intention: an empirical study of Malaysian millennial consumers. Sustainability, 14, 1945.10.3390/su14041945Search in Google Scholar

[12] Cavusoglu, L., Atik, D. (2023). Extending the diversity conversation: fashion consumption experiences of underrepresented and underserved women. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 57(1), 387–417.10.1111/joca.12504Search in Google Scholar

[13] Zakaria, N., Taib, J. S. M. N., Tan, Y. Y., Wah, Y. B. (2008). Using data mining technique to explore anthropometric data towards the development of sizing system. In Proceedings – International Symposium on Information Technology 2008.10.1109/ITSIM.2008.4631721Search in Google Scholar

[14] Jalil, M. H., Shanat, M. (2022). Developing a sustainable childrenswear sizing system: body size, silhouette shape, and clothing key dimensions. New Design Ideas, 6(2), 229–242.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Nurashikin Saaludi, N., Ismail, M. H., Harun, S. (2018). Exploring online apparel shopping satisfaction on sizing and fit for Malaysian children. In Asia Proceedings of Social Sciences (pp. 95–99).10.31580/apss.v2i4.348Search in Google Scholar

[16] Bizuneh, B., Destaw, A., Mamo, B. (2023). Analysis of garment fit satisfaction and fit preferences of Ethiopian male consumers. Research Journal of Textile and Apparel, 27(2), 228–245.10.1108/RJTA-08-2021-0102Search in Google Scholar

[17] Saaludin, N., Saad, A., Mason, C. (2020). Intelligent size matching recommender system: fuzzy. International Conference on Technology, Engineering and Sciences (ICTES) 2020 (Vol. 917, p. 012014). 10.1088/1757-899X/917/1/012014.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Zakaria, N., Gupta, D. (2014). Apparel sizing: existing sizing systems and the development of new sizing systems. Anthropometry, Apparel Sizing and Design. Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK.10.1533/9780857096890.1.3Search in Google Scholar

[19] Zakaria, N., Ruznan, W. S. (2020). Developing apparel sizing system using anthropometric data: body size and shape analysis, key dimensions, and data segmentation. In Anthropometry, Apparel Sizing and Design, Elsevier Science, The Boulevard, Kidlington, Oxford, United Kingdom (pp. 92–118).10.1016/B978-0-08-102604-5.00004-4Search in Google Scholar

[20] Wren, B. (2022). Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: a comparative study of current efforts and best practices to address the climate crisis. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain, 4, 100032.10.1016/j.clscn.2022.100032Search in Google Scholar

[21] Phupattarakit, T., Chutima, P. (2019). Warehouse management improvement for a textile manufacturer. In 2019 IEEE 6th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Applications (ICIEA).10.1109/IEA.2019.8714853Search in Google Scholar

[22] Sampaio, C. (2023). Definitive guide to K-means clustering with Scikit-Learn. Stack Abuse. Retrieved August 6, 2024, from https://stackabuse.com/definitive-guide-to-k-means-clustering-with-scikit-learn/.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Baltadjiev, A., Merdzhanova, E., Boyadjiev, N., Angelova, P., Raycheva, R., Lalova, V., et al. (2024). Children somatotype study of different ethnic groups from Plovdiv region, Bulgaria. Journal of IMAB, 30(1), 5381–5386.10.5272/jimab.2024301.5381Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 by the authors, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Characterization of viscoelastic properties of yarn materials: Dynamic mechanical analysis in the transversal direction

- Analysis of omni-channel implementations that are preferred by consumers in clothing sector

- Structural modeling and analysis of three-dimensional cross-linked braided preforms

- An experimental study of mechanical properties and comfortability of knitted imitation woven shirt fabrics

- Technology integration to promote circular economy transformation of the garment industry: a systematic literature review

- Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks

- Research on She nationality clothing recognition based on color feature fusion with PSO-SVM

- Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves

- Preparation and performance of stainless steel fiber/Lyocell fiber-blended weft-knitted fabric

- Development of an emotional response model for hospital gown design using structural equation modeling

- Preparation and properties of stainless steel filament/pure cotton woven fabric

- Facemask comfort enhancement with graphene oxide from recovered carbon waste tyres

- Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials

- Optical-related properties and characterization of some textile fibers using near-infrared spectroscopy

- Network modeling of aesthetic effect for Chinese Yue Opera costume simulation images

- Predicting consumers’ garment fit satisfactions by using machine learning

- Non-destructive identification of wool and cashmere fibers based on improved LDA using NIR spectroscopy

- Study on the relationship between structure and moisturizing performance of seamless knitted fabrics of protein fibers for autumn and winter

- Antibacterial and yellowing performances of sports underwear fabric with polyamide/silver ion polyurethane filaments

- Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics

- Phonetic smart clothing design based on gender awareness education for preschoolers

- Determination of anthropometric measurements and their application in the development of clothing sizing systems for women in the regions of the Republic of Croatia

- Research on optimal design of pleated cheongsam based on Kano–HOQ–Pugh model

- Numerical investigation of weaving machine heald shaft new design using composite material to improve its performance

- Corrigendum to “Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials”

- Shaping of thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites by direct surface modification using magnetron sputtering technique

- Numerical modeling of the heat flow component of the composite developed on the basis of basalt fabric

- Weft insertion guideway design based on high-temperature superconducting levitation

- Ultrasonic-assisted alkali hydrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate fabric and its effect on the microstructure and dyeing properties of fibers

- Comparative study on physical properties of bio-based PA56 fibers and wearability of their fabrics

- Investigation of the bias tape roll change time efficiency in garment factories

- Analysis of foot 3D scans of boys from Polish population

- Optimization of garment sewing operation standard minute value prediction using an IPSO-BP neural network

- Influence of repeated switching of current through contacts made of electroconductive fabrics on their resistance

- Numerical calculation of air permeability of warp-knitted jacquard spacer shoe-upper materials based on CFD

- Compact Spinning with Different Fibre Types: An Experimental Investigation on Yarn Properties in the Condensing Zone with 3D-Printed Guiding Device

- Modeling of virtual clothing and its contact with the human body

- Advances in personalized modelling and virtual display of ethnic clothing for intelligent customization

- Investigation of weave influence on flame retardancy of jute fabrics

- Balloonless spinning spindle head shape optimisation

- Research on 3D simulation design and dynamic virtual display of clothing flexible body

- Turkish textile and clothing SMEs: Importance of organizational learning, digitalization, and internationalization

- Corrigendum To: “Washing characterization of compression socks”

- Study on the promotion multiple of blood flow velocity on human epidermal microcirculation of volcanic rock polymer fiber seamless knitted fabric

- Bending properties and numerical analysis of nonorthogonal woven composites

- Bringing the queen mother of the west to life: Digital reconstruction and analysis of Taoist Celestial Beings Worshiping mural’s apparel

- Modeling process for full forming sports underwear

- Retraction of: Ionic crosslinking of cotton

- An observational study of female body shape characteristics in multiracial Malaysia

- Study on theoretical model and actual deformation of weft-knitted transfer loop based on particle constraint

- Design and 3D simulation of weft-knitted jacquard plush fabrics

- An overview of technological challenges in implementing the digital product passport in the textile and clothing industry

- Understanding and addressing the water footprint in the textile sector: A review

- Determinants of location changes in the clothing industry in Poland

- Influence of cam profile errors in a modulator on the dynamic response of the heald frame

- Quantitative analysis of wool and cashmere fiber mixtures using NIR spectroscopy

- 3D simulation of double-needle bar warp-knitted clustered pile fabrics on DFS

- Finite element analysis of heat transfer behavior in glass fiber/metal composite materials under constant heat load

- Price estimation and visual evaluation of actual white fabrics used for dress shirts and their photographic images

- Effect of gluing garment materials with adhesive inserts on their multidirectional drape and bending rigidity

- Optimization analysis of carrier-track collision in braiding process

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the ballistic performance of soft bulletproof vests for women

- The antimicrobial potential of plant-based natural dyes for textile dyeing: A systematic review using prisma

- Influence of sewing parameters on the skin–fabric friction

- Validation by experimental study the relationship between fabric tensile strength and weave structures

- Optimization of fabric’s tensile strength and bagging deformation using surface response and finite element in stenter machine

- Analysis of lean manufacturing waste in the process flow of ready-to-wear garment production in Nigeria

- An optimization study on the sol–gel process to obtain multifunctional denim fabrics

- Drape test of fully formed knitted flared skirts based on 3D-printed human body posture

- Supplier selection models using fuzzy hybrid methods in the clothing textile industry

Articles in the same Issue

- Characterization of viscoelastic properties of yarn materials: Dynamic mechanical analysis in the transversal direction

- Analysis of omni-channel implementations that are preferred by consumers in clothing sector

- Structural modeling and analysis of three-dimensional cross-linked braided preforms

- An experimental study of mechanical properties and comfortability of knitted imitation woven shirt fabrics

- Technology integration to promote circular economy transformation of the garment industry: a systematic literature review

- Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks

- Research on She nationality clothing recognition based on color feature fusion with PSO-SVM

- Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves

- Preparation and performance of stainless steel fiber/Lyocell fiber-blended weft-knitted fabric

- Development of an emotional response model for hospital gown design using structural equation modeling

- Preparation and properties of stainless steel filament/pure cotton woven fabric

- Facemask comfort enhancement with graphene oxide from recovered carbon waste tyres

- Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials

- Optical-related properties and characterization of some textile fibers using near-infrared spectroscopy

- Network modeling of aesthetic effect for Chinese Yue Opera costume simulation images

- Predicting consumers’ garment fit satisfactions by using machine learning

- Non-destructive identification of wool and cashmere fibers based on improved LDA using NIR spectroscopy

- Study on the relationship between structure and moisturizing performance of seamless knitted fabrics of protein fibers for autumn and winter

- Antibacterial and yellowing performances of sports underwear fabric with polyamide/silver ion polyurethane filaments

- Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics

- Phonetic smart clothing design based on gender awareness education for preschoolers

- Determination of anthropometric measurements and their application in the development of clothing sizing systems for women in the regions of the Republic of Croatia

- Research on optimal design of pleated cheongsam based on Kano–HOQ–Pugh model

- Numerical investigation of weaving machine heald shaft new design using composite material to improve its performance

- Corrigendum to “Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials”

- Shaping of thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites by direct surface modification using magnetron sputtering technique

- Numerical modeling of the heat flow component of the composite developed on the basis of basalt fabric

- Weft insertion guideway design based on high-temperature superconducting levitation

- Ultrasonic-assisted alkali hydrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate fabric and its effect on the microstructure and dyeing properties of fibers

- Comparative study on physical properties of bio-based PA56 fibers and wearability of their fabrics

- Investigation of the bias tape roll change time efficiency in garment factories

- Analysis of foot 3D scans of boys from Polish population

- Optimization of garment sewing operation standard minute value prediction using an IPSO-BP neural network

- Influence of repeated switching of current through contacts made of electroconductive fabrics on their resistance

- Numerical calculation of air permeability of warp-knitted jacquard spacer shoe-upper materials based on CFD

- Compact Spinning with Different Fibre Types: An Experimental Investigation on Yarn Properties in the Condensing Zone with 3D-Printed Guiding Device

- Modeling of virtual clothing and its contact with the human body

- Advances in personalized modelling and virtual display of ethnic clothing for intelligent customization

- Investigation of weave influence on flame retardancy of jute fabrics

- Balloonless spinning spindle head shape optimisation

- Research on 3D simulation design and dynamic virtual display of clothing flexible body

- Turkish textile and clothing SMEs: Importance of organizational learning, digitalization, and internationalization

- Corrigendum To: “Washing characterization of compression socks”

- Study on the promotion multiple of blood flow velocity on human epidermal microcirculation of volcanic rock polymer fiber seamless knitted fabric

- Bending properties and numerical analysis of nonorthogonal woven composites

- Bringing the queen mother of the west to life: Digital reconstruction and analysis of Taoist Celestial Beings Worshiping mural’s apparel

- Modeling process for full forming sports underwear

- Retraction of: Ionic crosslinking of cotton

- An observational study of female body shape characteristics in multiracial Malaysia

- Study on theoretical model and actual deformation of weft-knitted transfer loop based on particle constraint

- Design and 3D simulation of weft-knitted jacquard plush fabrics

- An overview of technological challenges in implementing the digital product passport in the textile and clothing industry

- Understanding and addressing the water footprint in the textile sector: A review

- Determinants of location changes in the clothing industry in Poland

- Influence of cam profile errors in a modulator on the dynamic response of the heald frame

- Quantitative analysis of wool and cashmere fiber mixtures using NIR spectroscopy

- 3D simulation of double-needle bar warp-knitted clustered pile fabrics on DFS

- Finite element analysis of heat transfer behavior in glass fiber/metal composite materials under constant heat load

- Price estimation and visual evaluation of actual white fabrics used for dress shirts and their photographic images

- Effect of gluing garment materials with adhesive inserts on their multidirectional drape and bending rigidity

- Optimization analysis of carrier-track collision in braiding process

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the ballistic performance of soft bulletproof vests for women

- The antimicrobial potential of plant-based natural dyes for textile dyeing: A systematic review using prisma

- Influence of sewing parameters on the skin–fabric friction

- Validation by experimental study the relationship between fabric tensile strength and weave structures

- Optimization of fabric’s tensile strength and bagging deformation using surface response and finite element in stenter machine

- Analysis of lean manufacturing waste in the process flow of ready-to-wear garment production in Nigeria

- An optimization study on the sol–gel process to obtain multifunctional denim fabrics

- Drape test of fully formed knitted flared skirts based on 3D-printed human body posture

- Supplier selection models using fuzzy hybrid methods in the clothing textile industry