Abstract

This article aimed at providing a new biomechanical three-dimensional dynamic finite element model of the hand–glove combination for exploring the distribution of the overall continuous dynamic contact pressure of the hand with the flexible glove in the state of grabbing an object, and further predicting the accuracy of sensors of wearable smart gloves. The model was validated by garment pressure experiments at eight muscle points. The results showed that the pressure value measured with three flexible gloves was highly consistent with the finite element simulation value. Based on the model, the distribution of dynamic pressure between the soft tissue of the hand and the fabric in the process of flexing the fingers and grabbing external objects were predicted accurately and effectively, which indicated that the model with high accuracy could be applied to evaluate the accuracy of the pressure value collected by sensors of smart gloves. In addition, the model had been confirmed that it has a certain application value. The findings could help to provide a reference for dynamic continuous monitoring equipment or other intelligent wearable devices, and promote the development of the intelligent clothing industry in the future.

1 Introduction

The advancement of flexible electronic technology provides development opportunities for the development of wearable flexible intelligent devices. Nowadays, there is a growing awareness of the exploitation of sensor equipment that can be flexible, stretched, wearable, and track the complex motion of the human body [1–4]. Flexible sensors can collect, process, and feedback on the relevant information of the human body through technologies such as textiles, materials, artificial intelligence, and the Internet. In particular, wearable smart products applied in the field of textile and clothing have specific functions such as human health monitoring [5], information transmission [6], communication [7], human–computer interaction [8], and other functions. Wearable smart gloves combined with flexible sensors provide an effective way to monitor, collect, and analyze the data of the hand, which has a significant impact on many application areas such as clinical medicine [9], human–computer interaction [10], bionic manufacturing [11], and product design [12]. For instance, small flexible capacitor sensors can detect micro gestures from small posture changes [13]; height stretching sensors can control the movement of the robot’s finger [14]; capacitance sensors can accurately rebuild the hand posture based on neural network algorithms [15]; and knitting pressure blocking gloves can identify the type and method of grabbing [16]. A multimode sensor system combined muscle activity with sensitive array [17] or flexible equipment with measuring strain and stress [18] also helps achieve gesture classification.

In the actual application scenario, the contact pressure between gloves and the soft tissue of the hand is important information that the pressure sensor needs to collect when wearing smart gloves and interacting with external objects. Although flexible sensor technology has developed rapidly in recent years, the flexible pressure sensor used in smart gloves is still defective in terms of signal stability, recognition accuracy, and response speed. Specifically, the relative position of the sensor and the hand is prone to change during the process of exercise, which makes it difficult to measure the pressure of glove–hand interface accurately. In addition, the number and location of the layout of the pressure sensor are limited, so the information detected is scarce, the signal acquisition system of the pressure sensor is too complicated to improve the stability of the signal acquisition, and the materials for manufacturing flexible pressure sensors are expensive. These factors are considered as the main limitations that affect the accuracy of the pressure collection.

The finite element numerical simulation method is one of the most commonly used methods in clothing pressure prediction. With the development of three-dimensional (3D) modeling technology, a 3D biomechanical model can be established, and the contact pressure, contact area, stress, and strain on the interface of the garment and the human body can be calculated accurately through digital simulation. Much research has focused on establishing finite element models for simulating the pressure between the garment and skin. Lin et al. [19] simulated the process of wearing tight pants to the lower limbs and the knee flexing movement to analyze the dynamic relationship between the tights and the skin surface. Dan and Shi [20] explored the displacement and pressure distribution of the waist-wearing elastic pantyhose during walking by the finite element simulation method. Chen et al. [21] studied the changes in the pressure of medical pressure socks on human legs with the finite element model. Hong et al. [22] established a finite element model of a standard female body bust section to find the linear equation between the pressure on the chest, the strain of the vest, and the fabric’s Yang’s modulus. Sun et al. [23] predicted the breast-shaping effect of the bra and the pressure distribution of the skin by establishing a finite element contact model of female ultra-elastic breasts and steel ring bras. With the establishment of the finite element simulation model, the interface pressure distribution of a certain part of the human body can be understood. Nevertheless, the current research focused on the impact of the pressure caused by tight functional pressure garments on the human body. The exploration of continuous dynamic pressure on garment–skin interface in interaction between the human body and external objects is still unclear.

The signal output by wearable smart gloves that is based on sensor technology in actual detection applications is closely related to human body surfaces, dynamic parameters, and materials itself. However, there is no clear criterion for the accuracy of the output signal, which puts forward a huge challenge for the development of wearable smart gloves. In addition, the accuracy of the glove system needs to be tested before the wearable smart gloves are produced, which helps to evaluate whether gloves are suitable for investment. Currently, it is rarely measured by the entire glove system in terms of repetitiveness and accuracy. At the same time, it lacks a standard performance evaluation method, which also becomes an obstacle to the industrialization of wearable smart gloves.

Based on the aforementioned issues, there is an urgent need for a set of calibration measurement accuracy data to assess the reliability of the data collected by smart gloves. The purpose of this study is to establish a combined 3D biomechanical model of the hand and glove. The simulation model can output the continuous dynamic pressure of the glove–palm interface in real time. The distribution of the contact pressure obtained by the numerical simulation can be applied to evaluate the accuracy of the pressure sensor of smart gloves, overcome the limitations of current smart gloves in applications, and provide data reference for the accuracy of data collection of wearable flexible smart gloves. At the same time, it helps to improve the evaluation system of wearable flexible smart gloves. The numerical simulation method can also be extended and applied to the accuracy evaluation of other wearable intelligent textiles to promote the further development of the industry of smart e-textiles.

2 Methodology

2.1 Establishment of a finite element model of hand

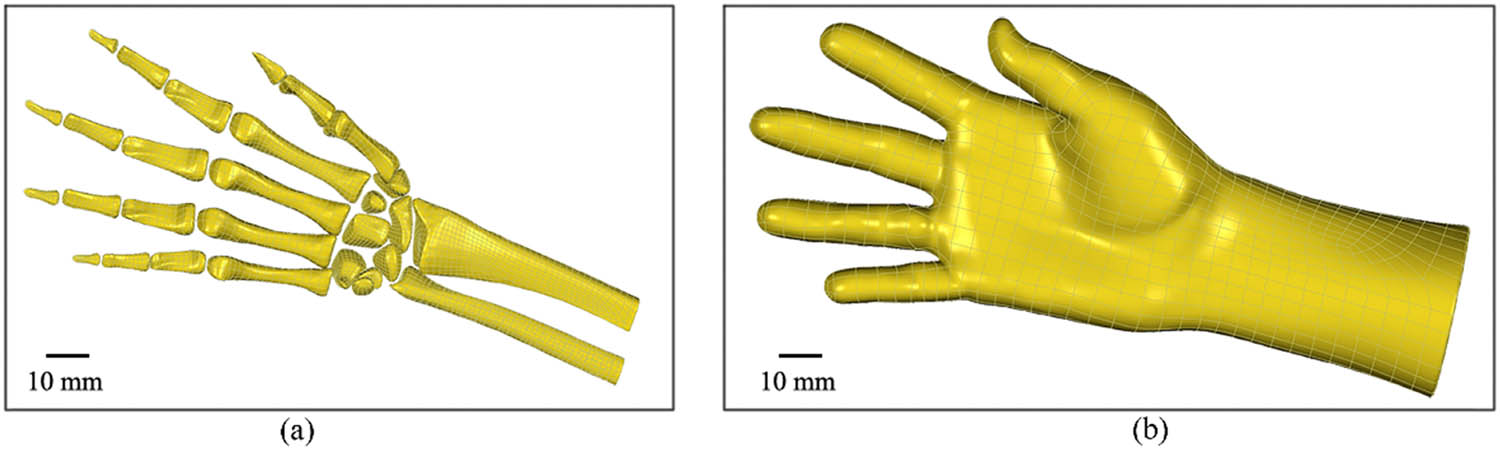

In this research, a 3D solid model of the hand was established by cropping operations based on an open-source 3D anatomical male human digital model, and the process of reconstruction of the model of the hand was as follows: Geomagic Studio 2012 software was used for smooth processing on the model surface, and eventually converted polygon facial slices into Nurbs curved surfaces suitable for creating complex curved shapes. Then, each component model of the hand was introduced in the Solidworks 2019 software to reintegrate. Since the complex geometric surfaces of the bones and soft tissue in the hand model and the high requirements for the mesh quality, Hypermesh 2019 software was chosen to carry out 3D meshing. Finally, the 3D geometry model of the hand was obtained, as shown in Figure 1, which consists of soft tissue and an internal skeleton. Furthermore, as we were concerned with the contact pressure at the glove–palm interface rather than the internal response of the hand, the ligaments and tendons of the finger joints were not considered to simplify the model.

The 3D geometry model of the hand. (a) The bone of the hand and (b) the soft tissue of the hand.

2.2 Establishment of a finite element model of the glove–hand combination

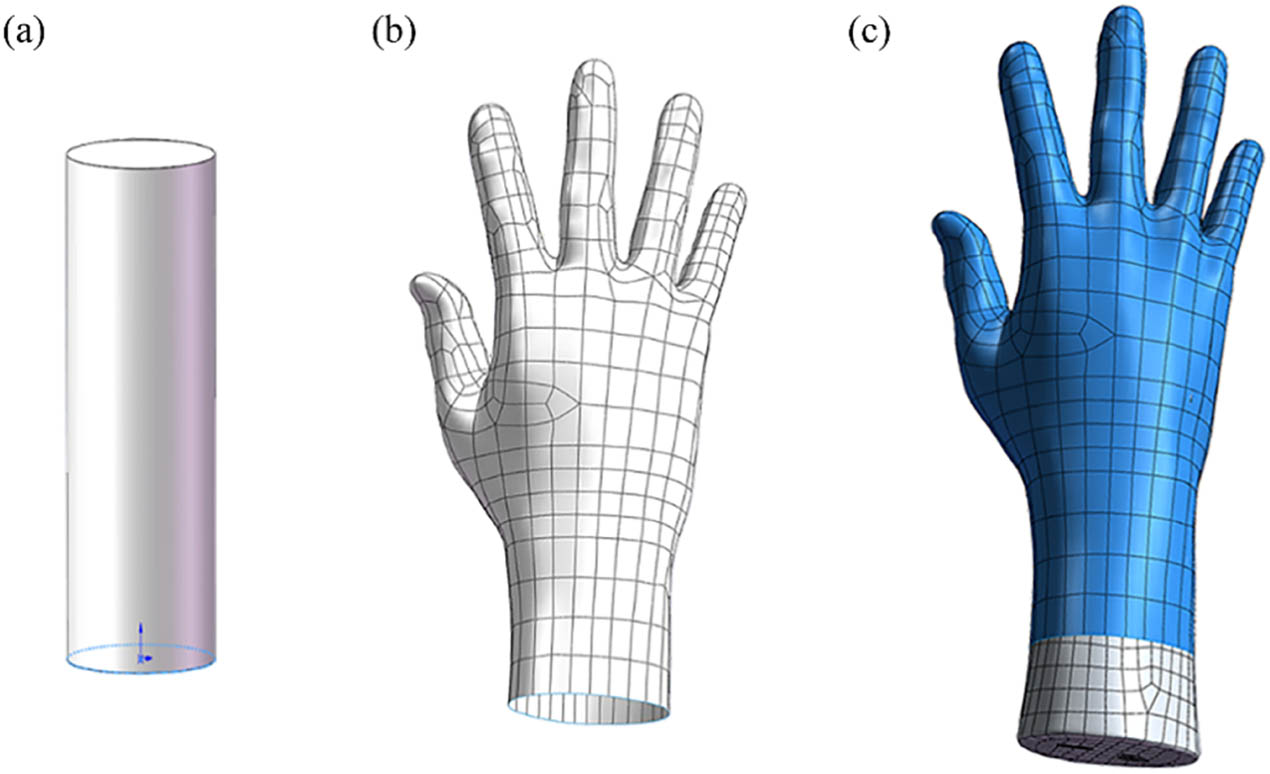

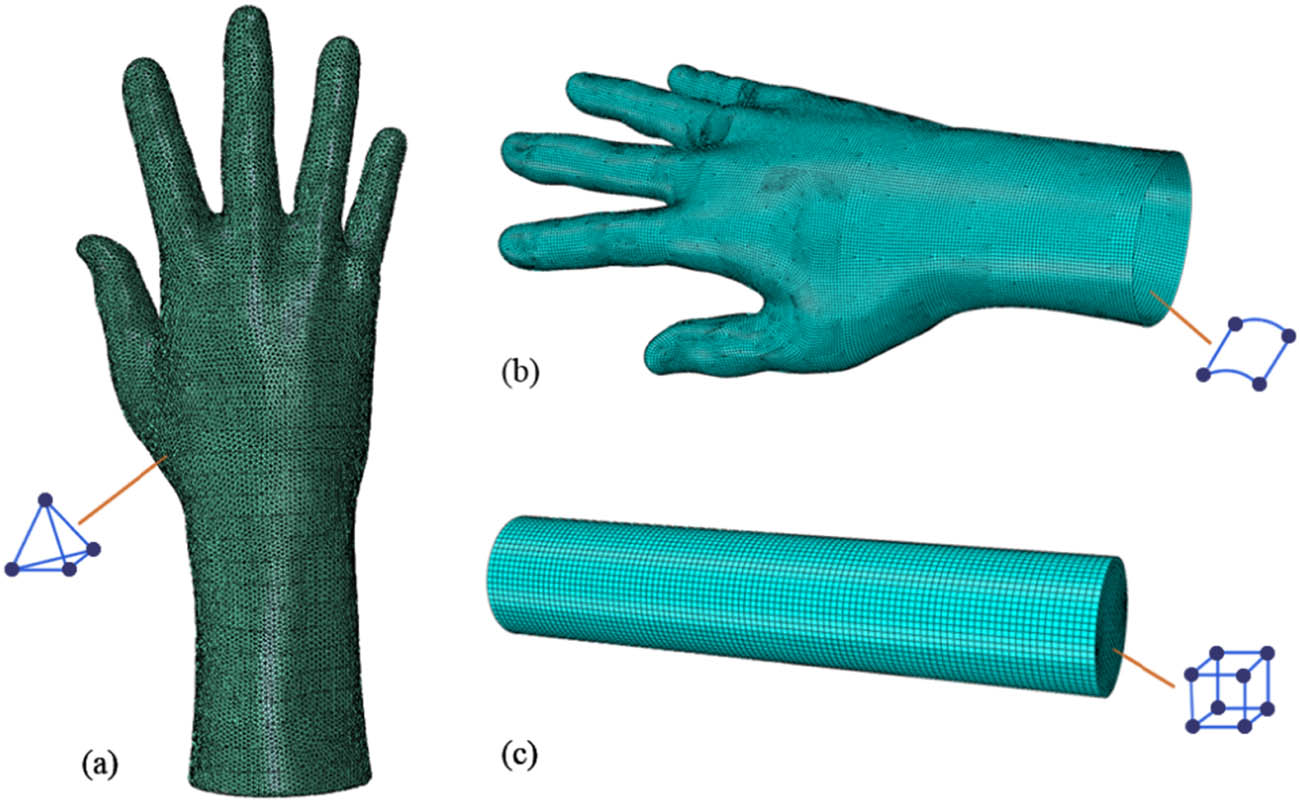

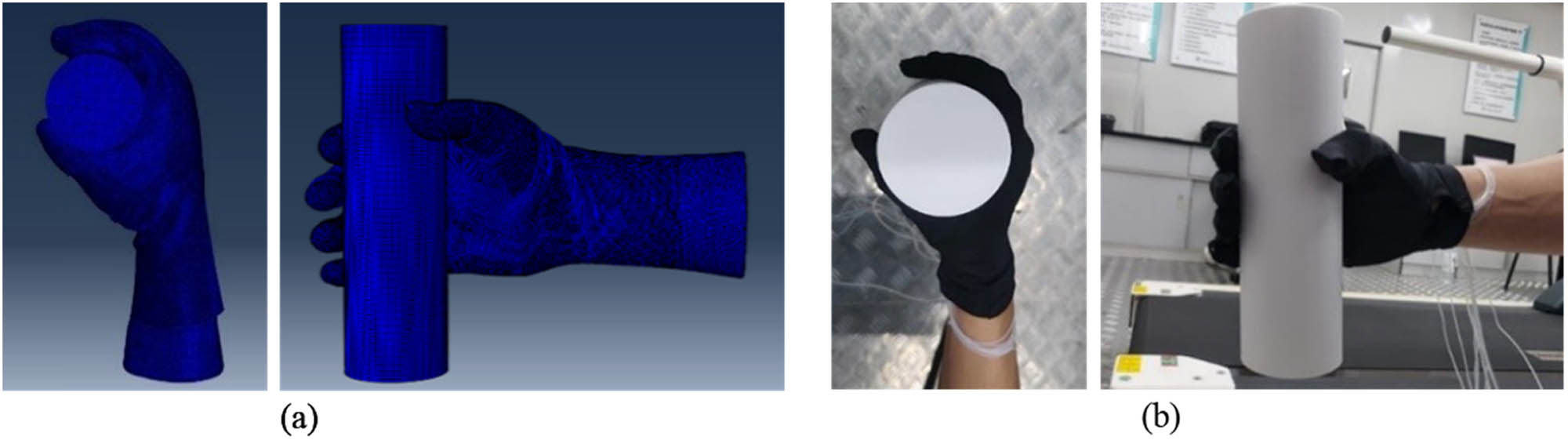

A combined glove–hand model was further constructed for predicting the glove–palm surface contact pressure, which included the hand, the glove, and a cylinder. The model of the cylinder was obtained in the part module in the Solidworks 2019 software (Figure 2a). As the base layer of the wearable flexible smart glove is a light-fitting glove, the 3D shell glove fabric geometry model was constructed based on the built hand model by shell extraction operation in Solidworks 2019 software (Figure 2b). In the end, a combined model of the hand-wearing gloves was established (Figure 2c).

(a) The model of the cylinder, (b) the model of the glove, (c) the model of the glove–hand combination.

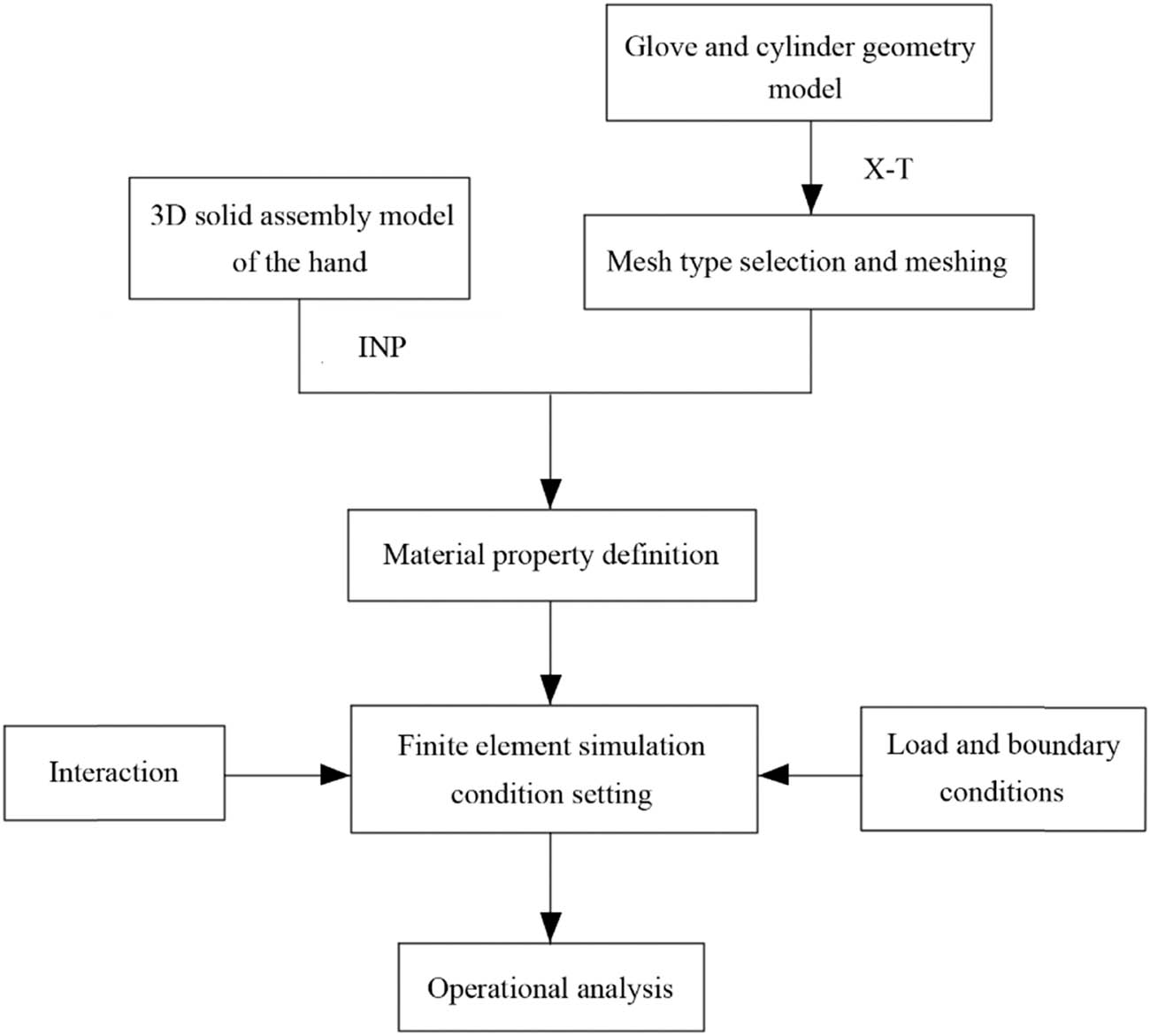

The 3D geometric model of the hand was preprocessed. Then, the complete combination model was introduced into the Abaqus 2020 software for finite element simulation, including the definition of material attributes, the selection of grid types, loads, constraints, and the setting of boundary conditions. The process of reconstruction of the finite element model of the glove–hand combination is shown in Figure 3.

The process of reconstruction of the finite element model of the glove–hand combination.

2.2.1 Materials

The bones are composed of cortex and pine bone, both of which have viscoelastic and anisotropic mechanical characteristics. Some scholars have given various material parameters to the cortical and pine bones, respectively. In theory, it is closer to the authenticity characteristics of human bone materials that define bones as nonaverage materials. However, the particularity of biomass is that as an active organization, its material parameters will change under different mechanical effects. Within a specific range, the cortex and pine bone have the characteristics of linearly elastic material. Because of previous studies on the mechanical properties of the human body [24,25,26,27], bones of the hand were defined as a homogeneous, linearly elastic material in the simulation. Therefore, this study characterized the bones as an average linearly elastic material to simplify calculations.

In addition, the mechanical properties of soft tissues are more complicated. Scholars believe that it can be regarded as a homogeneous linearly elastic body when observing the changes in soft tissues, which can make the finite element simulation results highly accurate. Therefore, based on ref. [28–32], the properties of linearly elastic material were adopted as the material parameters of the soft tissue in this article.

Since the cylindrical handle is a tool that people commonly use to interact with the outside world, a cylindrical geometric object was included in the simulation, and the material was defined as Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene [33].

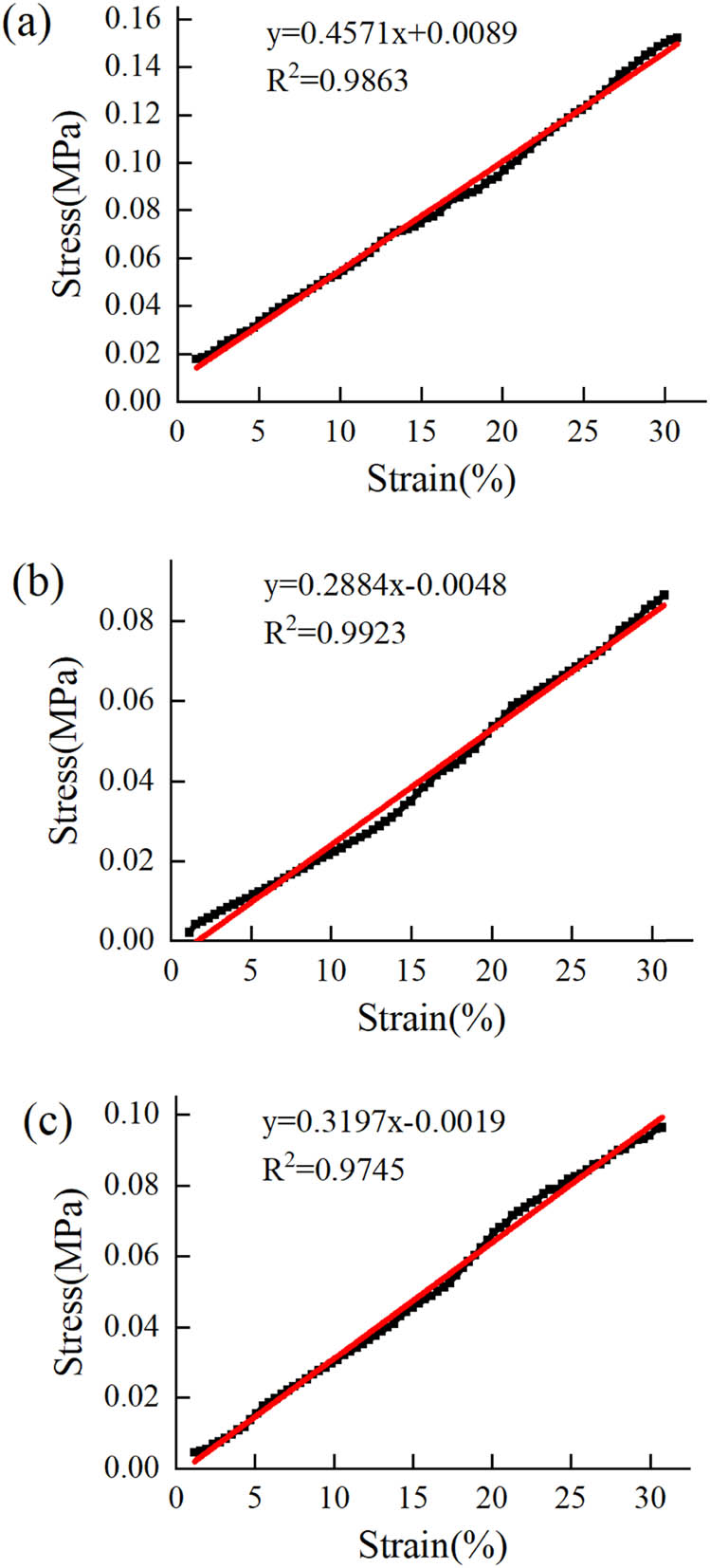

Due to the substrate of wearable smart gloves being flexible textile gloves, the three light-fitting gloves were experimentally measured as the material properties of the glove fabric. Concretely, the quality and thickness of fabric samples were measured by electronic balance and thickness instrument, and the density values were calculated through the ratio of quality and volume. The stretching rate of glove fabrics generally does not exceed 30% when wearing gloves for grasping movements. Therefore, the single-axis stretching experiments were used to test the mechanical performance of fabric samples. According to the stretching experimental data, the tensile stress–strain curves of the three fabrics in the wale and course direction can be obtained from an excellent linear relationship within the range of 0–30%. In terms of the slope of the straight line is Young’s modulus, and the ratio of horizontal and vertical strain is Poisson’s ratio of the fabric. The glove mainly occurs in the vertical stretching and deformation at the grip movement. Correspondingly, the stress produced during the stretching process is primarily related to the mechanical behavior of the fabric in the wale direction. Hence, only the tensile properties of the fabric in the wale direction were considered in the simulation (Figure 4), and the material of the glove fabrics model used in the simulation can be regarded as the linear elastic and isotropic material. The material parameters of each component of the finite element model are shown in Table 1.

Tensile stress–strain curves of the wale direction of the three glove fabrics: (a) fabric 1, (b) fabric 2, and (c) fabric 3.

The material parameters of each component in the finite element model

| Part | Density (kg/m3) | Young’s modulus (MPa) | Poisson’s ratio | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | 1,950 | 14,000–20,000 | 0.3 | Ref. [24–27] |

| Soft tissue | 1,100 | 0.177 | 0.4 | Ref. [28–31] |

| Gloves (fabric 1) | 453 | 0.457 | 0.304 | Ref. [32] |

| Gloves (fabric 2) | 336 | 0.288 | 0.379 | Ref. [32] |

| Gloves (fabric 3) | 468 | 0.320 | 0.329 | Ref. [32] |

| Cylinder | 1,040 | 2 | 0.39 | Ref. [33] |

2.2.2 Mesh

The types of bones and soft tissues of the hand were defined as a four-node linear tetrahedron element (C3D4) combined previous researches and needs of the study. The meshing density of the bones was 2 mm, and the soft tissue was 1 mm (Figure 5a). The mesh elements used for the glove fabric model were four nodes of curved shell (S4R) with limited membrane strain (Figure 5b). The glove model consisted of 30,902 elements with a minimum mesh size of 1.5 mm. The type of cylinder was defined as the eight-node linear six-sided element (C3D8R), and there were 38,400 elements in the model with a minimum mesh size of 2 mm (Figure 5c).

(a) The mesh of the hand, (b) the mesh of the glove, and (c) the mesh of the cylinder.

2.2.3 Load and boundary conditions

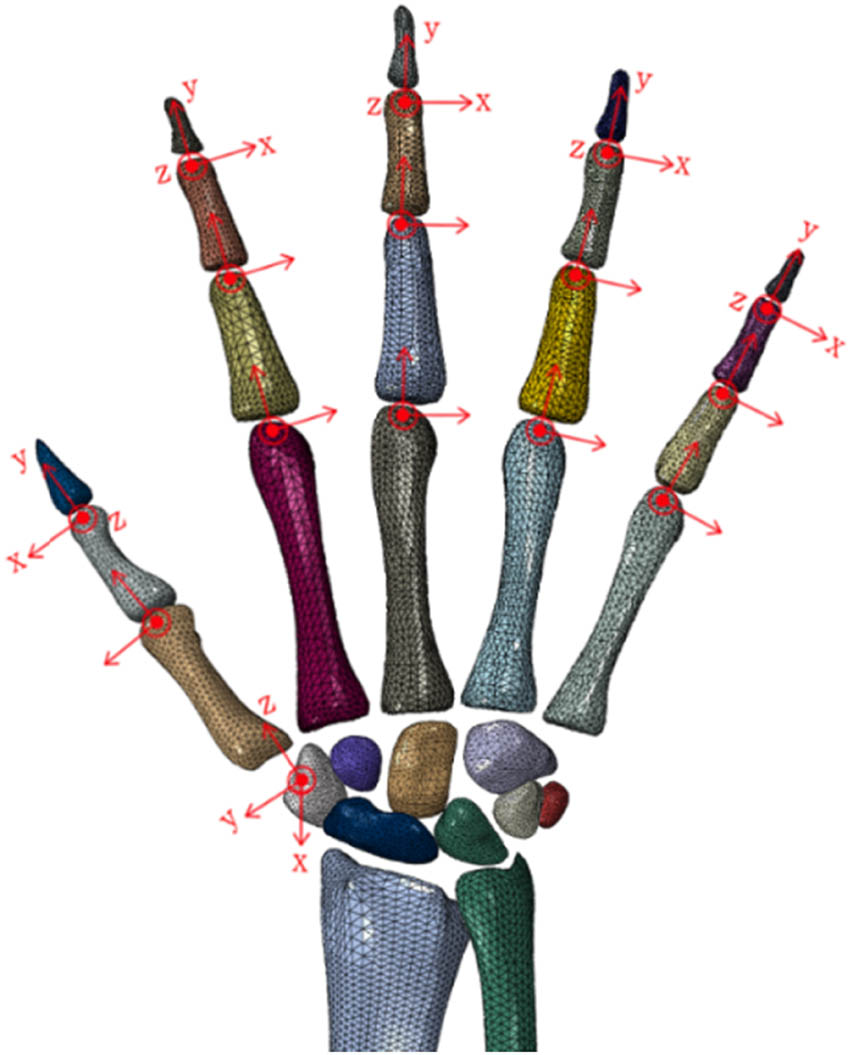

The reference points were defined on the internal bones, and all nodes on the bone were coupled to the reference point, which was convenient to describe the kinematic information and exert mechanical load on the hand. Furthermore, as multiple joints in the fingers have a subordinate relationship during exercise, the local coordinate system was established at each joint, so that the finger bones can be rotated under each local coordinate system. The local coordinate system of the finger joints of the hand finite element model is shown in Figure 6.

The local coordinate system of the finger joints of the hand finite element model.

Joint displacements were applied to each joint for gripping motion simulation, and a static measurement method was used in this article to determine the rotation angle of each joint hinge in the gripping posture. The joint angles of each finger measured from human experiments were applied to the joint local coordinate system of the hand finite element model as load conditions [33].

3 Experimental verification of finite element model

To verify the accuracy of the pressure of the simulation prediction, the garment pressure on the palm of the hand was measured with the hand wearing the glove, and compared with the pressure that predicted by the finite element prediction.

3.1 Experimental materials

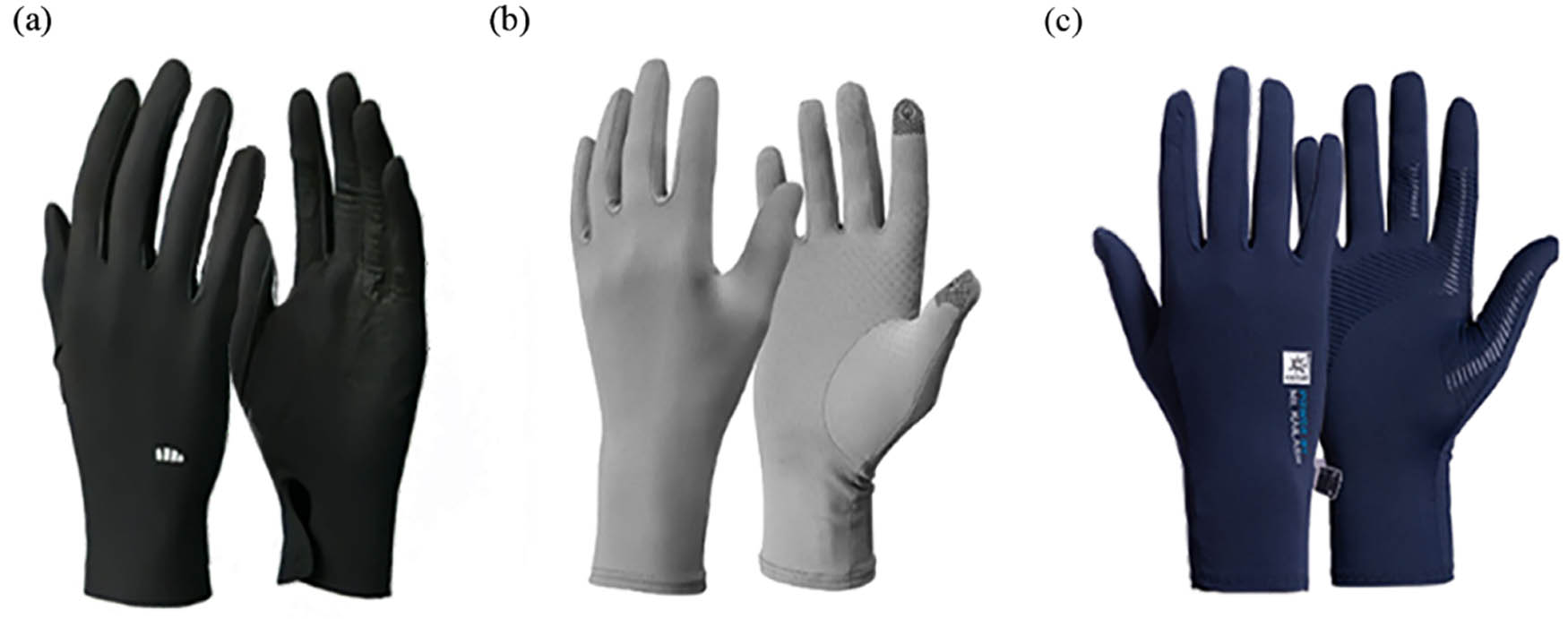

Ideally, the wearable flexible smart glove combined the sensing system with an ordinary textile glove. In alignment with the manufacturing principles governing smart gloves and the imperative for validating the effectiveness of the combined glove–hand model in this study, three light-fitting gloves available in the market were selected through pre-experiments, identified as fabric 1, fabric 2, and fabric 3. The style of the three glove fabrics is shown in Figure 7, and their specific parameter is shown in Table 2.

The style of the three glove fabrics: (a) fabric 1, (b) fabric 2, and (c) fabric 3.

The fabric parameters of the three gloves

| Number | Material parameters |

|---|---|

| Fabric 1 | 92% nylon, 8% spandem |

| Fabric 2 | 85% polyester, 15% spandex |

| Fabric 3 | 70% cotton, 30% spandex |

The grasping object should have a simple geometric shape to avoid unnecessary factors that may increase complexity of the results. Therefore, a cylinder was chosen as the grasping object, and the diameter and height of the cylinder were set to 60 and 200 mm, respectively, to avoid the uncomfortableness. The cylinder was made of Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene by a 3D printer (Shanghai Dianxiang Automation Equipment Co., Ltd., Dianxiang, DX-750s, China).

3.2 Selection of feature points

The measurement location of the soft tissue of hand was determined by existing theory and pre-experiments. Based on biomechanical studies of the finger joints, it is clear that muscle attachment points can be used as an important area for garment measuring. Furthermore, it can be concluded that the curvature of the body is an important factor in garment pressure. Eight points were finally determined as the pressure test point, with the specific locations shown in Figure 8: A (flexor pollicis longus), B (flexor disitorum profundus of index finger), C (flexor disitorum profundus of middle finger), D (flexor disitorum profundus of ring finger), E (flexor disitorum profundus of little thumb), F (musculus flexor pollicis brevis), G (thenar), and H (hypothenar).

Location of pressure test points on the hand.

3.3 Measurement of the finger joint angle

Angles of 14 joints of fingers in the grabbing position were measured by an angular gauge when the hand reached a stable grip on a cylinder in this study. To minimize the error, each joint was measured three times to ensure that the error in each measurement did not exceed 5°, and the measured joint angles of each finger joint in the gripping position are shown in Table 3.

The angles of the joints of fingers under the grabbing posture

| Finger joints | Thumb (°) | Index finger (°) | Middle finger (°) | Ring finger (°) | Little thumb (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distant interphalangeal point | 24.06 | 17.19 | 25.78 | 20.05 | 34.38 |

| Middle interphalangeal point | 36.67 | 63.03 | 74.48 | 68.75 | 74.48 |

| Proximal interphalangeal point | 73.91 | 103.13 | 117.46 | 111.73 | 97.40 |

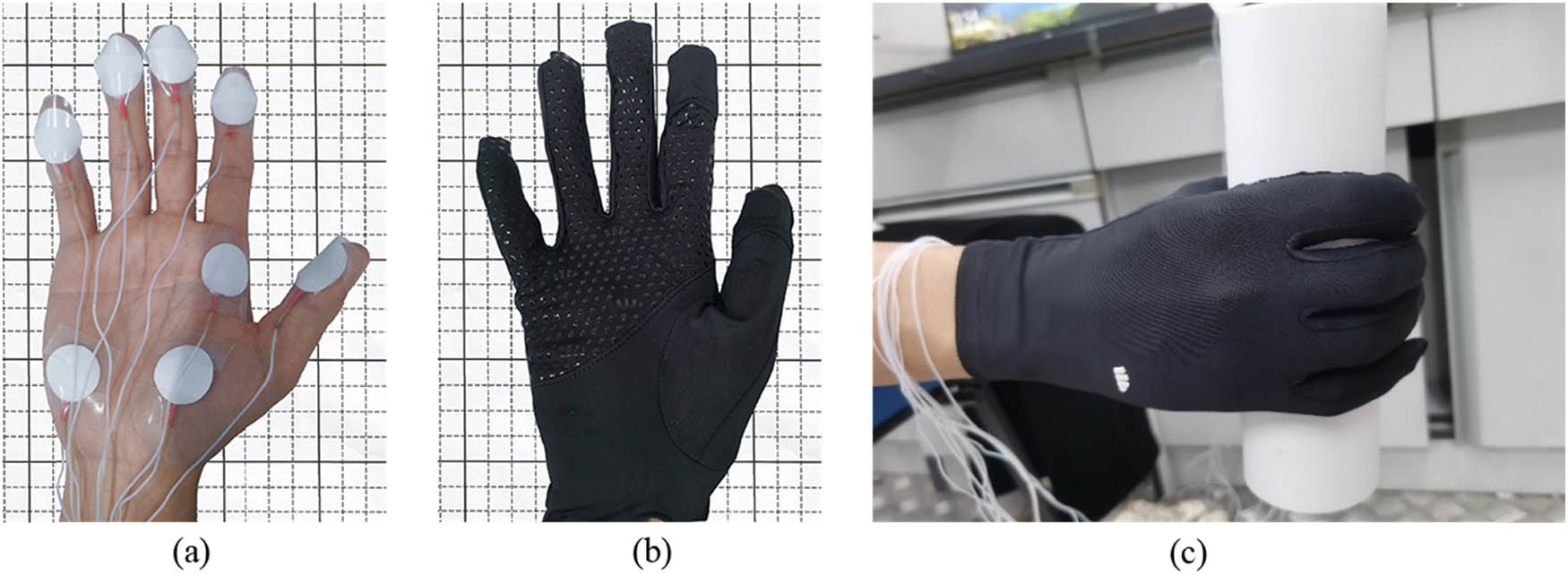

3.4 Garment pressure test experiment

The AMI3037-10 airbag contact pressure test system was used for garment pressure testing, which includes airbags, pressure converters, and data collectors. The measurement principle of the sensor is to measure the pressure between the two planes. Pressure sensors are both flexible materials, so that they will change with the changes in the fingers during the test. Then, the pressure-sensitive area of the sensor is relatively small compared to the surface area of the grasped object, so the fit with the surface of the cylinder is relatively high during the force transmission process, and the force used to deform the sensor can be ignored in the method of transmission. In addition, the sensors were calibrated before the test to eliminate the system error. Under this premise, it can be considered that the attached sensor’s impact on the inherent mechanical elasticity of the human skin will be reasonably small and will not affect the measurement results. The measurement accuracy is high enough to capture continuous dynamic garment pressure. Except for considering that the built finite element model of hand is based on the right hand of a healthy adult man, the hand dimensions of the selected subjects should be consistent with the model. Five healthy men (average age 22.9 ± 1.1 years, height 174.6 ± 6.3 cm, weight 63.7 ± 8.1 kg, and body mass index 20.5 ± 1.5 kg/m2) were recruited for this study, and all subjects were free of hand injury.

The pressure experiment was performed in a climatic chamber at a temperature of 25 ± 1°C and a relative humidity of 65 ± 2%. In turn, five subjects were asked to wear three light-fitting gloves with different fabric compositions. The airbag probe of the AMI airbag pressure sensor was placed on the eight test points of the right hand. The instrument was set to zero after wearing glove fabrics, and then subjects gripped at the same joint angle as the model. As shown in Figure 9, all subjects gripped the cylinder with the right hand, and it was still motionless after reaching the stability of grasping. The posture was maintained for 10–15 s for pressure records, and then, this step was repeated five times to obtain the average value.

Garment pressure test experiment: (a) the fixation of the airbag pressure sensors, (b) the state of the glove was worn on the hand, and (c) the action of grasping the cylinder.

For the sake of verifying the effectiveness of the model, the position of each finger and the flexion angle of the joint in the experimental gripping posture were kept the same as the simulation when the gripping posture was finally achieved. The grip postures of experimental and simulation results are shown in Figure 10. Obviously, the comparison of the posture in the experiment and simulation shows significant similarity.

Comparison of the gripping posture: (a) finite element simulation and (b) experiment.

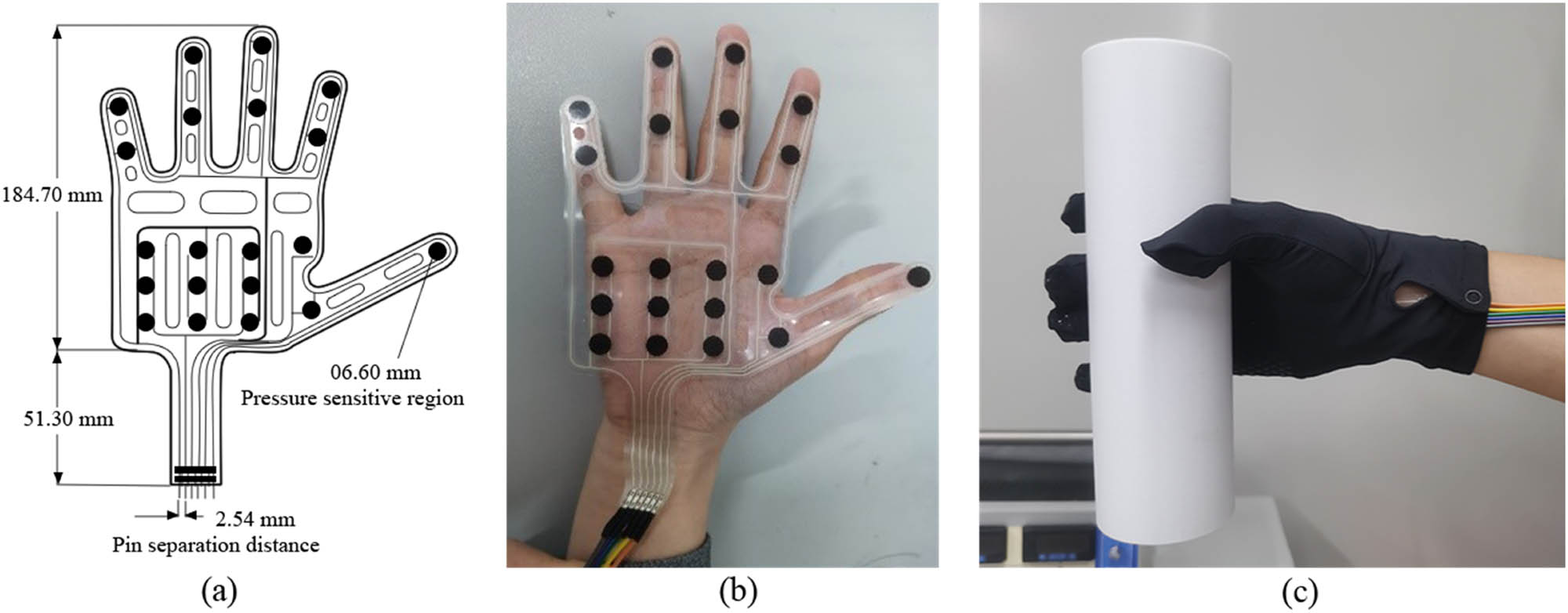

3.5 Pressure collection of sensors of wearable smart gloves

To predict the accuracy of the pressure sensor of wearable smart gloves, a film flexible sensor commonly used in smart gloves on the market (flexible film pressure sensor ZNS-01 smart glove piezoresistive multipoint sensing pressure sensor) was selected and placed on the palm of the hand, and then the flexible glove was worn for cylindrical grasping, as shown in Figure 11. The contact pressure collected by the film flexible sensor can be compared with the simulation value, which is conducive for the accuracy assessment of the finite element model.

(a) The size of the flexible film pressure sensor, (b) the sensor placed on the palm of the hand, and (c) the pressure data collection of the sensor.

4 Results

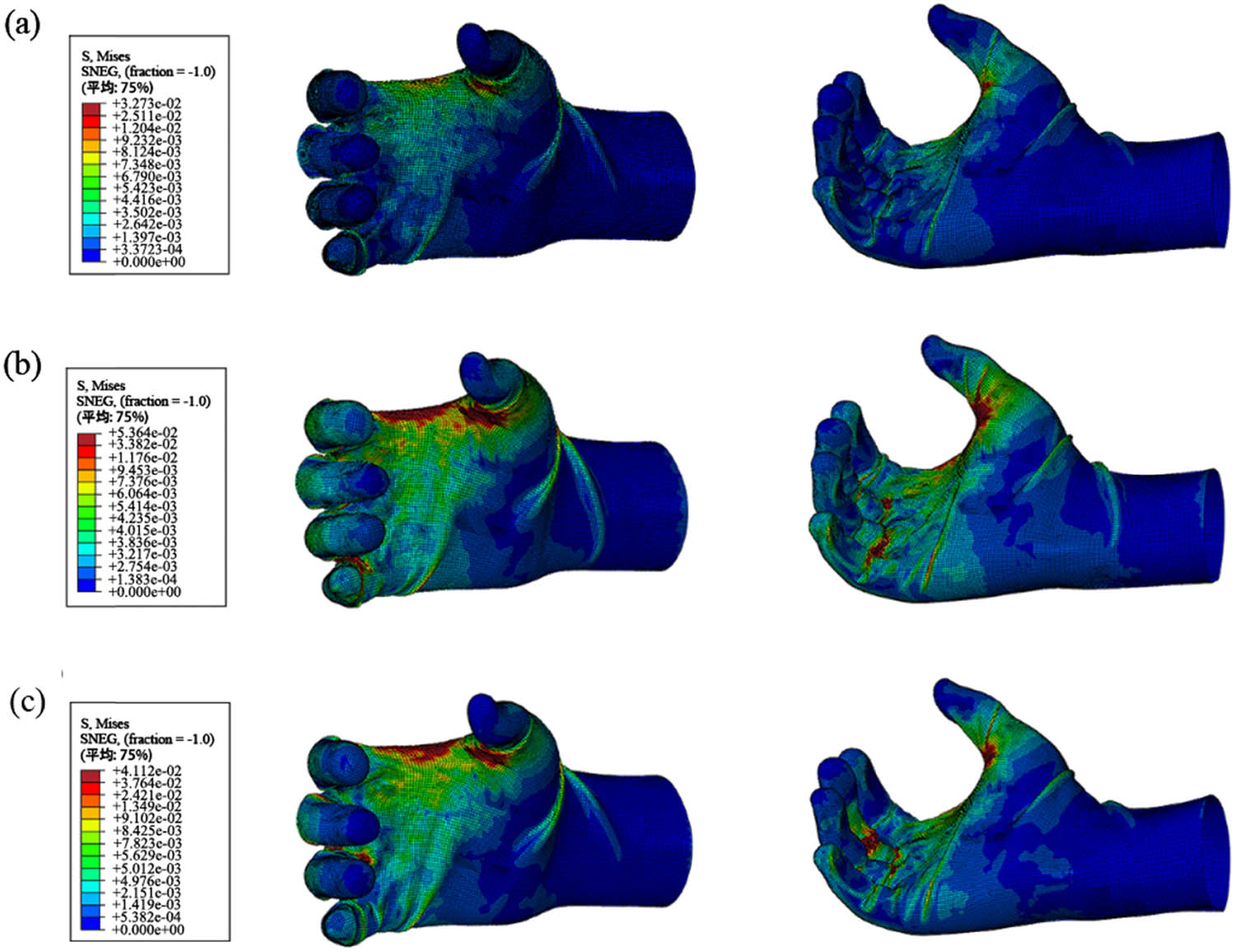

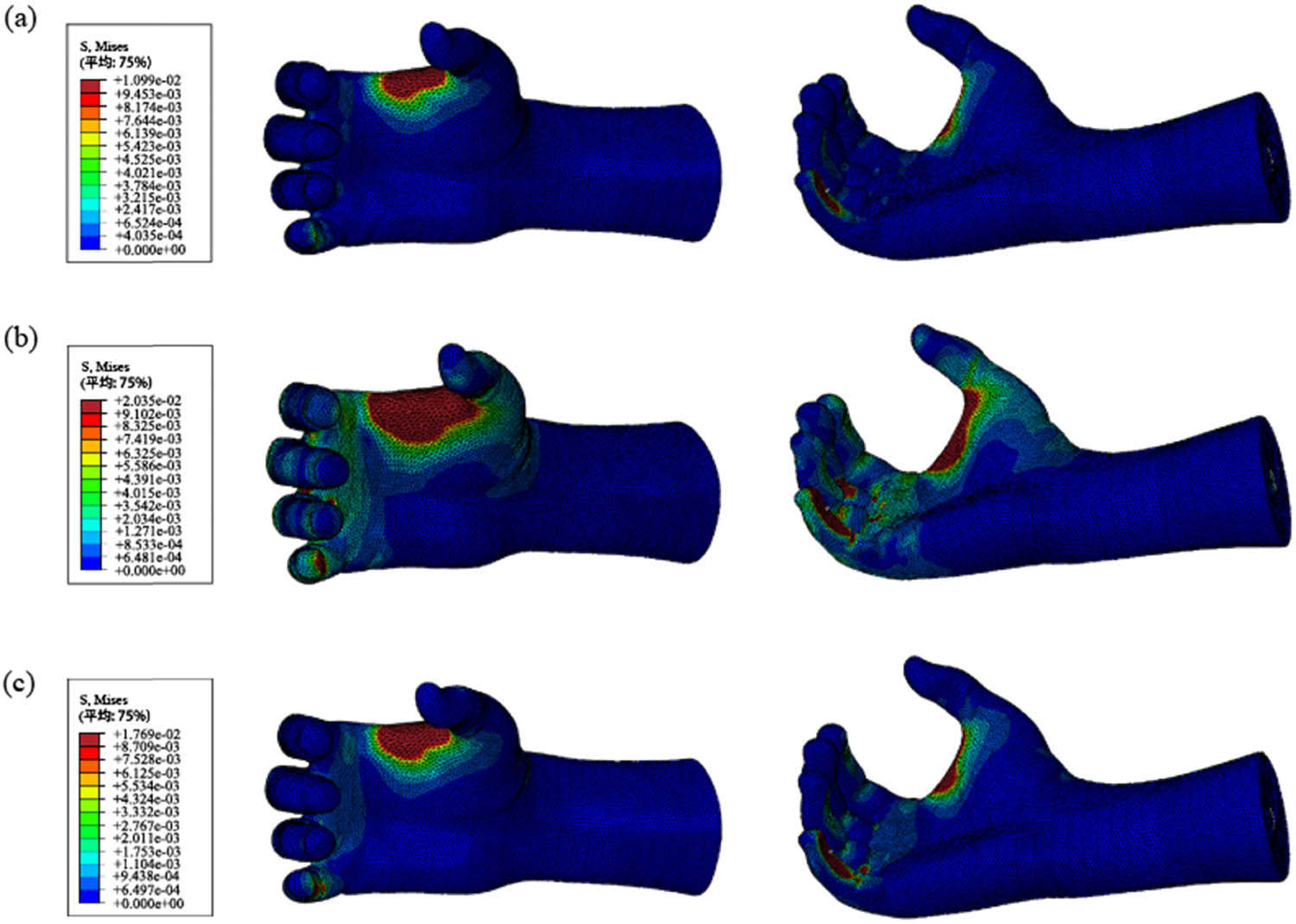

4.1 The stress distribution of gloves and soft tissues

The Abaqus 2020 software was used to complete the numerical simulation of the hand gripping a cylinder while wearing a flexible glove fabric in this research. The display dynamic analysis was adopted to simulate the dynamic flexion process of the finger. What’s more, the joint displacement was applied to the “hinge” connector to drive the model, and the specific joint angles were measured in previous experiments. A set of eight pressure test points was set up in advance to output the contact pressure at the glove–palm interface in the visualized module. The material properties of fabric 1, fabric 2, and fabric 3 were assigned to the shell finite element model of the glove respectively to observe the effect of different mechanical properties of different glove fabrics on the interface pressure. The stress distributions of gloves and soft tissues are shown in Figures 12 and 13, respectively.

The stress distribution of gloves: (a) fabrics 1, (b) fabric 2, and (c) fabric 3.

The stress distribution of the soft tissue of the hand: (a) the situation of wearing fabric 1 glove, (b) the situation of wearing fabric 2 glove, and (c) the situation of wearing fabric 3 glove.

In the process of grip with a glove fabric, dynamic deformation of the fabric occurred due to external force with the finger movement. The mechanical properties of different glove fabrics correspond to different fabric compositions. Generally, the greater the Young’s modulus, the less likely the material to deform, and the stronger the rigidity of the material, the greater the hardness, so that the smaller the Young’s modulus, the greater the deformation produces and the less stress the fabric is subjected to. It is shown in Figure 12 that the lowest stress was distributed on fabric 1, and the minimum stress was between the center of the palm and the bottom of the glove, about 3.273 × 10−5 MPa; the stress of fabric 2 was the highest due to the minimum Young’s modulus, at approximately 5.364 × 10−2 MPa, and the strain was also the largest correspondingly, about 18.63%. Owing to the convex surface of the thenar and its greater curvature, the stress and strain of the area corresponding to the glove were higher than the surrounding area, with a maximum stress of approximately 7.564 × 10−4 MPa. The stress distributed in immediate areas was between 6.383 × 10−5 and 7.271 × 10−4 MPa. The maximum stress of fabric 3 was concentrated at the location of the thumb side of the glove, about 4.112 × 10−2 MPa, followed by the distal area of the thumb and index finger, the proximal area of the ring and middle finger of the glove, all with stress magnitudes floated between 7.382 × 10−4 and 3.471 × 10−3 MPa, and the lowest stress distributed between the center of the palm and the little thumb side of the glove, at approximately 5.934 × 10−5 MPa.

In conclusion, the overall stress distribution trends of three glove fabrics were consistent, which meant that the model established had the effectiveness of biomechanics. Simultaneously, the effectiveness of the glove–hand combination finite element model was also verified.

The interaction force from the cylinder to the glove fabric was further transferred to the soft tissues through the glove after a stable gripping position had been achieved. As shown in Figure 13, the stress distribution of soft tissue with three flexible glove fabrics has a high consistency and the stress suffered by soft tissue is smaller than the glove as a whole. To be specific, the maximum stress occurred in the proximal area of the fingers and the area attached to the musculus flexor pollicis brevis. It can be known that the stress of soft tissue wearing fabric 2 glove was the highest, followed by fabric 3 and fabric 1, respectively, which is related to the material mechanical properties of the fabric. The maximum stress of soft tissue wearing fabric 1 was 1.099 × 10−2 MPa, the stress of soft tissue wearing fabric 2 was 2.035 × 10−2 MPa, and the stress of soft tissue wearing fabric 3 was 1.769 × 10−2 MPa. Secondly, stress analysis was conducted on specific areas: the distal region of the index finger, the proximal regions of the middle finger, ring finger, and little finger. The stress values for soft tissue with fabric 1 ranged from 2.104 × 10−5 to 1.149 × 10−4 MPa, fabric 2 exhibited stress levels within the range of 4.535 × 10−5 to 7.646 × 10−4 MPa, and fabric 3 showed stress levels ranging from 3.432 × 10−5 to 3.511 × 10−4 MPa. Furthermore, it was observed that the stress in the area under the palm of the hand was the lowest.

4.2 The distribution of continuous dynamic contact pressure

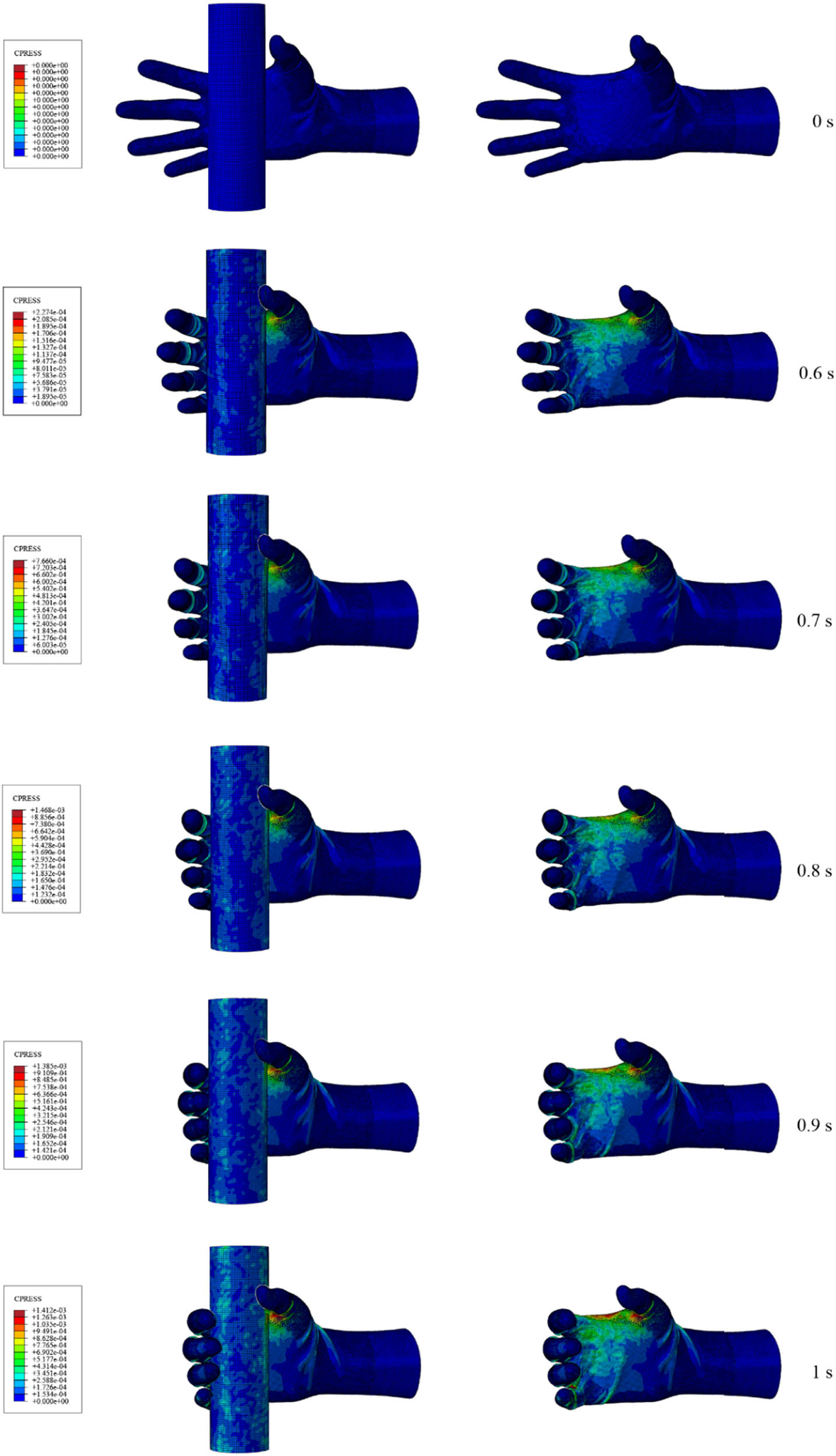

There was no contact between the hand and the cylinder until 0.6 s, the grip movement was over to reach a stable grip state when the time reached 1 s. The dynamic flexion process of grasping action was quantified and analyzed in Figure 14, to gain a clearer understanding of the changes in the contact pressure between the glove and the hand, which shows the contact pressure cloud diagram of action similar to that of the hand gripping a cylinder while wearing the fabric 1 glove during the course of 0, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, and 1 s.

The cloud diagram of the contact pressure of the finger flexing dynamic grip process in the state of wearing the fabric 1 glove.

It can be seen from the figure that the fingers were completely stretched when the grip movement had not begun, and the contact pressure between the palm and the glove was 0 MPa. With the increase of the flexion angle, the stress of the area where the musculus flexor pollicis brevis attached to the soft tissue was increasingly concentrated. It was because muscles were passively stretched in the movement of the finger flexion. As a result, the greater the curvature at the point of attachment of the muscle, the greater the stretching and deformation of glove fabrics at the corresponding location, the stress of the soft tissue and the glove increased, and the contact pressure also increased. At the same time, as the gripping action was carried out, the distance between the cylinder and the palm got closer, and the palm was squeezed by the external objects to produce greater deformation, leading to the increased pressure in the contact area. The maximum contact pressure on the palm reached 1.412 × 10−3 MPa when a steady-state gripping posture was reached. Besides, the maximum contact pressure in the finger flexing process occurred in areas where the musculus flexor pollicis brevis attached.

5 Discussion

5.1 Model verification

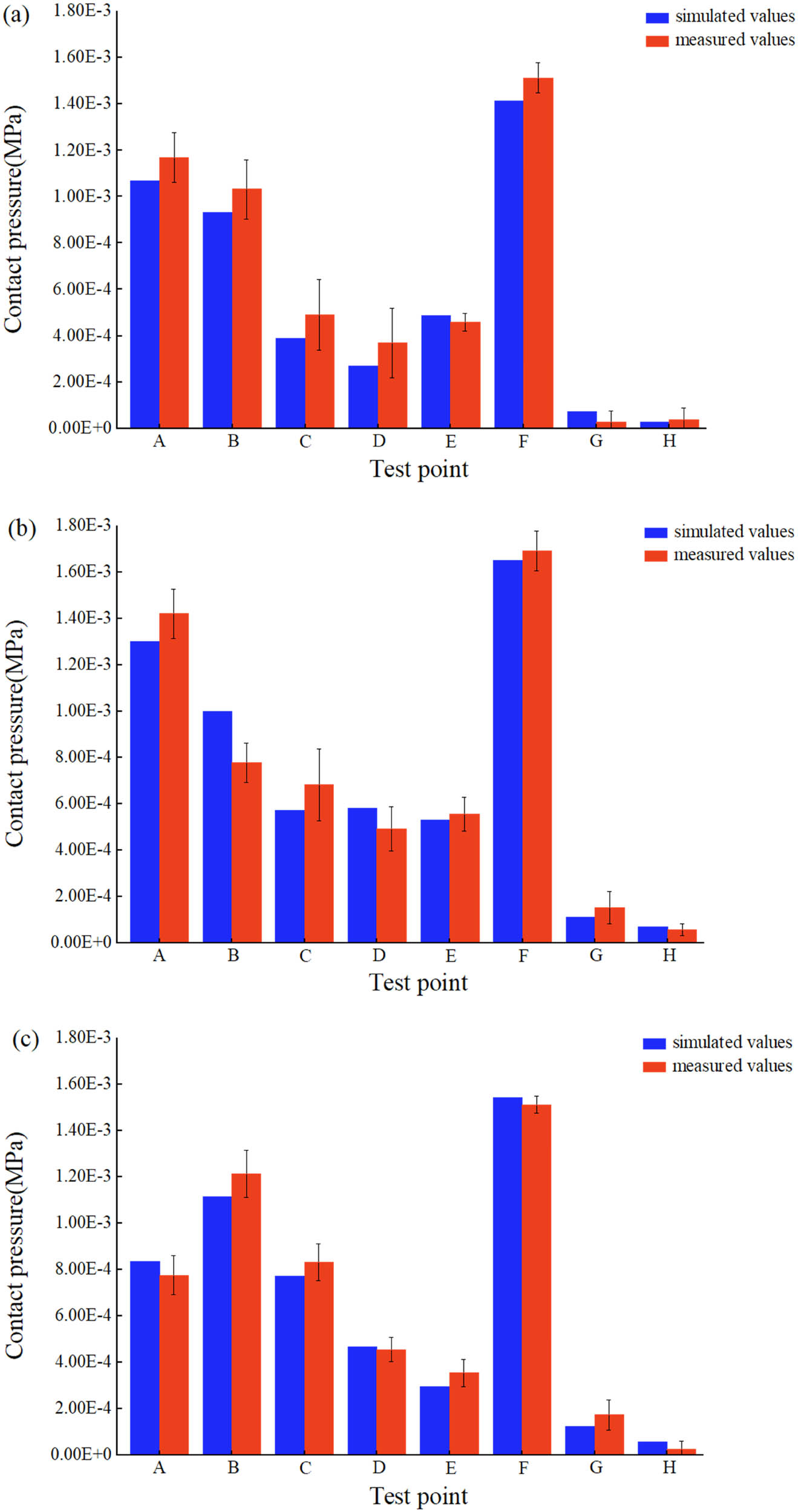

Within the aim of verifying the effectiveness of the finite element model, the data obtained from the AMI airbag pressure sensor were compared and analyzed for relative errors with the simulated data obtained by the finite element method at the corresponding location. According to the actual size of the airbag probe, the average pressure value in the unit mesh with a diameter of 2 cm was taken as the analog value of the finite element model, and the average value of each test point measured by the five experimental objects was considered as the measured value. Thanks to individual differences, the pressure experimental value of the five experimental objects was analyzed by error. In addition, the average and standard deviation of the contact pressure at the same test point were calculated to reflect the discreteness of the experimental data. The shorter the error bar, the smaller the error in the measured value. The quantitative comparison of the contact pressure is shown in Figure 15.

Comparison of contact pressure of simulated and measured values: (a) the situation of wearing fabric 1 glove, (b) the situation of wearing fabric 2 glove, and (c) the situation of wearing fabric 3 glove.

The comparison of the contact pressure between the finite element simulations with measured values of wearing fabric 1 glove is shown in Figure 15(a). It was manifested from the finite element simulation results that the contact pressure at the hypothenar was the smallest, about 2.601 × 10−5 MPa, and on the contrary, the location where the musculus flexor pollicis brevis attached was subjected to the highest pressure at approximately 1.412 × 10−3 MPa. The finite element simulation results were analyzed based on the average of the measured contact pressure while wearing the fabric 1 glove, and the relative errors of each test point were as follows: A (flexor pollicis longus): 10.77%; B (flexor disitorum profundus of the index finger): 12.87%; C (flexor disitorum profundus of middle finger): 15.21%; D (flexor disitorum profundus of ring finger): 15.17%; E (flexor disitorum profundus of little thumb): 3.76%; F (musculus flexor pollicis brevis): 6.39%; G (thenar): 4.83%; and H (hypothenar): 5.26%. Figure 15(b) compares the measured values of wearing the fabric 2 glove with the simulated values, and the contact pressure of each test points ranged from 7.211 × 10−5 to 1.651 × 10−3 MPa. Figure 15(c) depicts a comparison between the measured values of wearing the fabric 3 glove and the simulated values. The hypothenar had the smallest relative error of 2.57% and the largest relative error of 15.21% was found on the flexor disitorum profundus of index finger.

In a word, it can be seen that the relative errors of contact pressure between the simulated and measured during dynamic gripping while wearing the three flexible gloves were within a reasonable range. Among them, the relative error at the key point of the muscles was a maximum of 15.59% and a minimum of 2.57%. Nevertheless, the relative errors of the flexor disitorum profundus of index, middle, and ring fingers were large because the force-generating habits were different for each experimental subject when grasping the cylinder. Furthermore, due to the challenges encountered in accurately pinpointing the muscle measurement points during the in vitro garment pressure testing experiment, a certain level of discrepancy was observed between the simulated and measured values. Despite this, the contact pressure values measured by the three flexible gloves exhibited a consistent trend of change with the finite element simulation. Notably, the finite element predictions for the eight test points aligned well with the experimental measurements, indicating a high degree of accuracy in the finite element model. Moreover, the simulated results for each test point were mostly within the average ± standard deviation of the results obtained for the five subjects in the experiments, so the model could be proved to have operational stability.

5.2 Accuracy prediction model of the smart glove

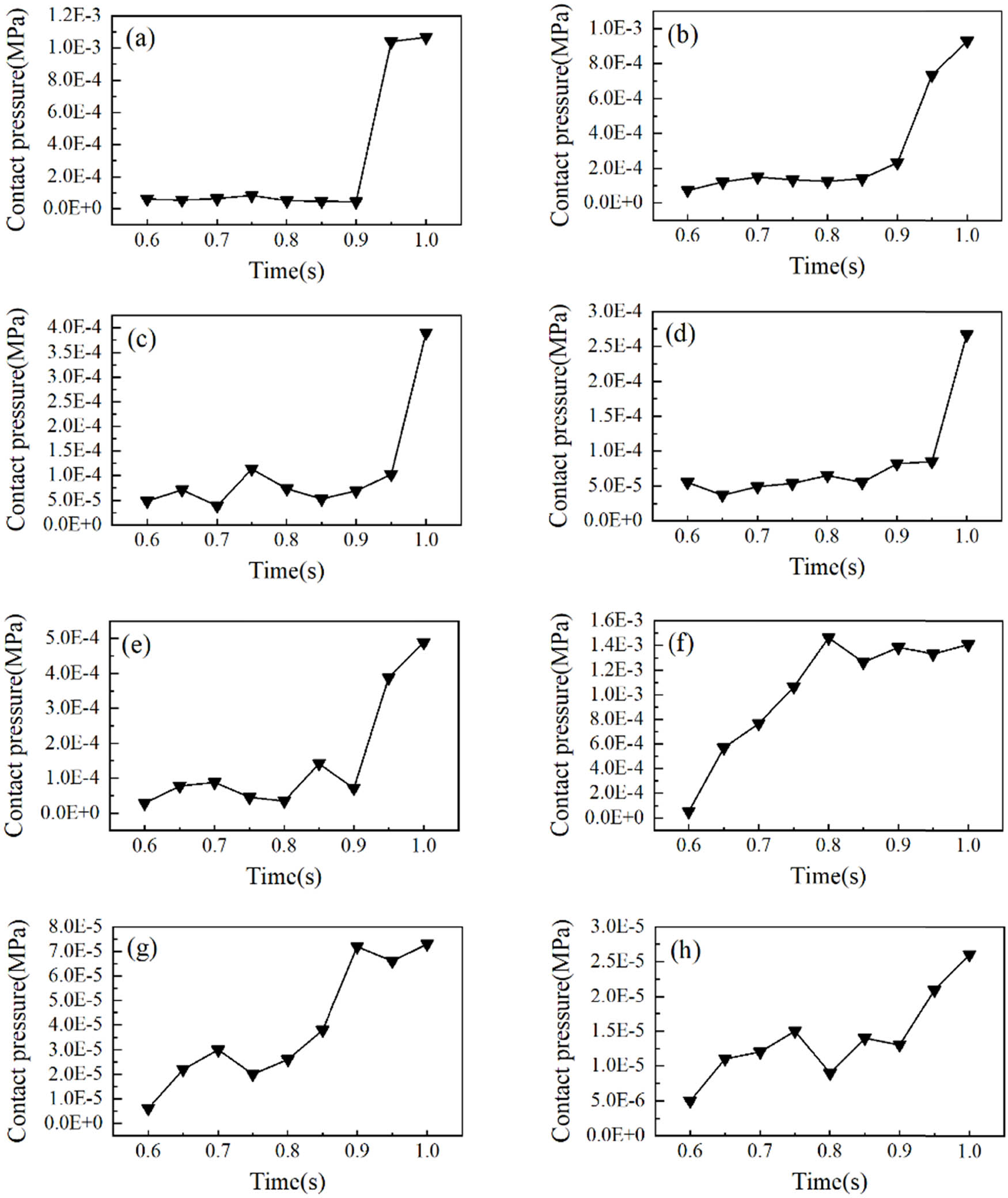

In an effort to further investigate the changes of contact pressure between the palm and the glove in the process of flexion of the fingers with the fabric 1 glove, the simulated values at each test point were extracted at 0.6, 0.65, 0.7, 0.75, 0.8, 0.85, 0.9, 0.95, and 1 s, and the changes of contact pressure under the flexion movement were analyzed quantitatively.

As shown in Figure 16, the pressure value of all test points changed significantly, and the trend of overall contact pressure of the eight test points was on the rise during the finger flexing. Concretely, the contact pressure of the area attached to the flexor disitorum profundus of five fingers was almost no change within 0.6–0.9 s and the increase in the trend became gentle. With the increase of the flexion angle, the fingers began to contact the cylindrical surface, so that the contact pressure increased sharply in 0.9–1 s. The contact pressure in the attachment area of the musculus flexor pollicis brevis gradually increased at the beginning of the grip until it reached a pressure maximum of 1.463 × 10−3 MPa at 0.8 s, after which the contact pressure remained between 1.264 × 10−3 and 1.412 × 10−3 MPa. The overall contact pressure in the region of the thenar and hypothenar was relatively small, and the pressure values fluctuated slightly with the flexion of the fingers. With a slow increase in the overall trend, the pressure value reached the maximum when fingers reached a stable gripping position.

The contact pressure simulation results during the finger flexing process in the action of grabbing the cylinder with fabric 1 glove: (a) the contact pressure at point A, (b) the contact pressure at point B, (c) the contact pressure at point C, (d) the contact pressure at point D, (e) the contact pressure at point E, (f) the contact pressure at point F, (g) the contact pressure at point G, and (h) the contact pressure at point H.

Referring to the results of the simulation, it can be concluded that the contact pressure was the largest at the location of the attachment position of the musculus flexor pollicis brevis, and the magnitude of the contact pressure curve over time was also greater. Hence, with the aim of making the data comparison curve more obvious, the data of contact pressure at point F were extracted in the postprocessing module of Abaqus software to read the change with finger flexion. Finally, the pressure dispersion point diagram of the change over time was obtained. Then, the simulation data were linearly filed by the Origin software, and the simulation linear regression model was established, as shown in equation (1). The equation is a linear regression model of the contact pressure at the point F over time when the fingers were flexed at a uniform rate of 1 s until the gripping action was complete and a stable grip on the cylinder was achieved after wearing the glove.

where x is time (s) and y is the contact pressure (MPa) at the attachment point of the musculus flexor pollicis brevis.

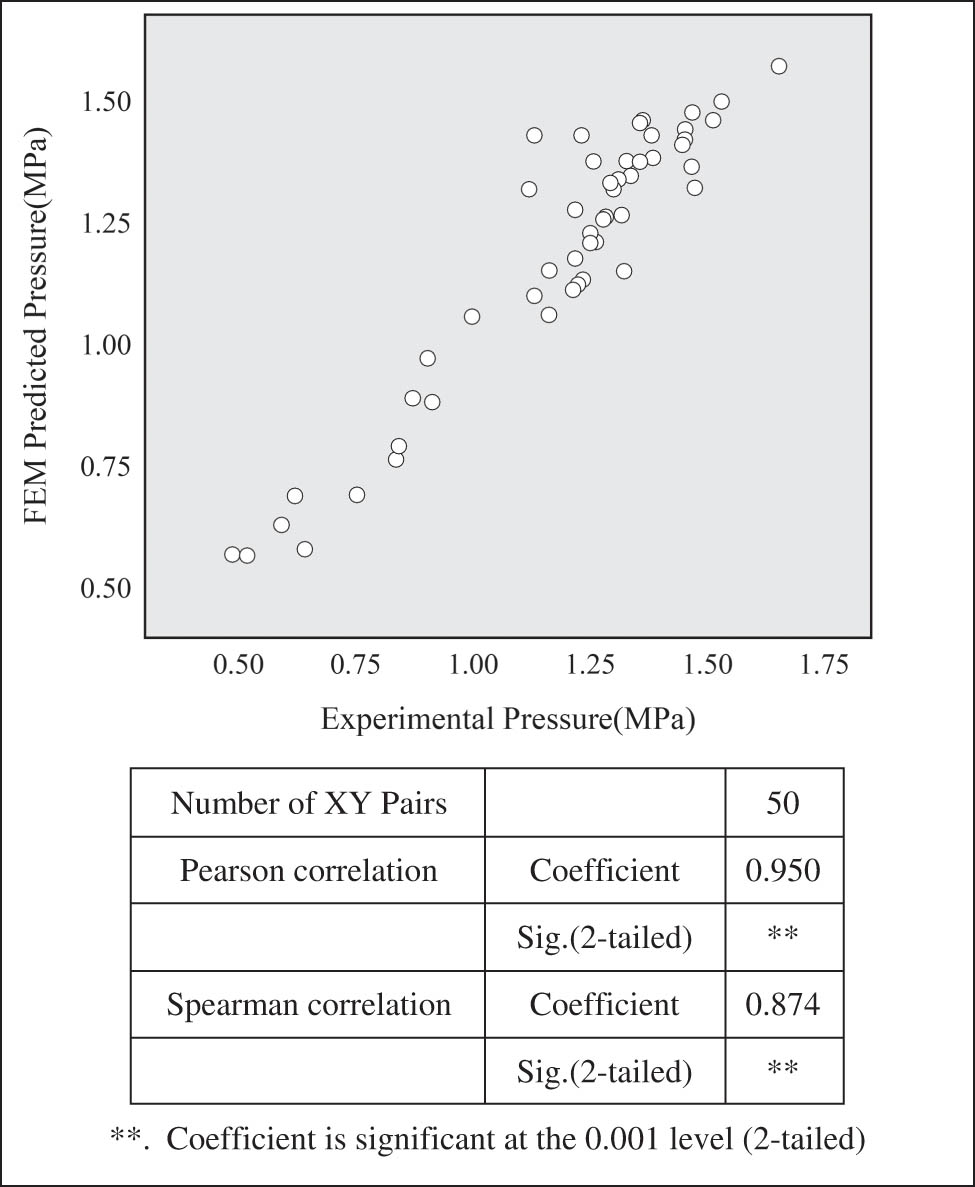

The Pearson test and Spearman nonparametric test were used to quantify the correlation between experimental measurements and simulations. The descriptive and correlation statistical tests were run under SPSS27 software. The statistical results obtained are shown in Figure 17. It can be seen that there was a significant Pearson correlation (R = 0.950, N = 50, P < 0.001) and the Spearman rank correlation (R = 0.874, N = 50, P < 0.001) between the simulated and measured pressure values. The prediction pressure distribution was generally consistent with the experimental results, which proved that the model could characterize the accuracy of the sensor of wearable flexible smart gloves.

Analysis of the relevance of the experimental and simulated pressure at the musculus flexor pollicis brevis.

Apart from this, the mean absolute error (MAE) was selected as a representation indicator of a linear regression model, and the experimental and simulated values of continuous dynamic pressure during gripping were analyzed for relative errors. The difference between the experimental and simulated results was evaluated through the MAE calculated by equation (2). The smaller the value, the smaller the error between the two. Considering the confirmed effectiveness of the biomechanical model established, which accurately predicts continuous dynamic garment pressure, it can be utilized to assess the precision of the pressure sensor in collecting pressure values. In the end, the resulting MAE for the sensor was calculated to be 0.066, the value was small enough to explain that the smart glove pressure-sensitive resistance flexible film pressure sensor has high accuracy during data collection.

where n is the number of data points; A (MPa) is the contact pressure predicted in the simulation; E (MPa) is the contact pressure tested in the experiment; and j is the time serial number. As a consequence, MAE corresponds to the average absolute value error between the measured and predicted values.

6 Conclusions

In this study, a combined finite element hand model with a flexible glove fabric was developed to predict the contact pressure distribution of the glove–hand interface when the hand interacts with external objects with the glove fabric. The simulation process of wearing three gloves with different fabric components for grasping the cylinder showed a high degree of similarity in contact pressure at eight specific pressure test points between the measured and simulated results, so that the combined finite element model was proven to be valid. Furthermore, the dynamic contact pressure distribution between the glove and the hand during the dynamic grasp wearing a glove was analyzed. Then, the dynamic pressure variation curves were extracted and a linear regression model was developed to compare and analyze the pressure data output from the sensor of the wearable flexible smart glove in actual applications. In the end, the MAE was used to evaluate the accuracy of the performance of the sensor, which indicated that the finite element simulation technology was able to effectively characterize the accuracy of the sensor of wearable devices in data collection.

This study predicted the contact pressure distribution of the glove–hand interface successfully when the hand interacts with external objects in the state of wearing gloves. The overall contact pressure and distribution of the hand could be displayed intuitively in a visual cloud diagram by the garment dynamic pressure model that we built. It helps to understand the mechanical relationship between the fabric and the hand when the human body interacts with external objects and can also provide data for the comfort of dressing. In addition, the finite element simulation prediction model can be used to characterize the accuracy of the collection signal of the sensing materials, which will be significant to promote the development, optimization, and effect prediction of flexible intelligent wearable devices. What is more, it can be combined with textile materials, measurement technology, and sensor technology to further expand into a variety of practical applications, such as bionic manufacturing, clinical medicine, rehabilitation auxiliary tools, virtual interaction, and other fields.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the biomechanics staff of Liverpool John Moores University, and Human Efficacy and Functional Clothing Laboratory of Shanghai University of Engineering Science where the present study was conducted.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Plan of China “Active Health and Aging Science and Technology Copper” under Grant number 2018YFC2000900.

-

Author contributions: Yan Zhang: Conceptualization; Methodology; Formal Analysis; Writing – Original Draft Preparation; Visualization; Investigation; Data Curation. Hong Xie: Paper Review & Editing; Supervision; Project Administration; Funding Acquisition. Mark J. Lake: Paper Review & Editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors report there are no competing interests to declare for this article.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. Requests for data should be directed to the corresponding author [Yan Zhang] at [zhangyan20210301@126.com]. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to [reasons for restriction, e.g., ethical considerations, participant confidentiality], but de-identified data may be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Gao, W., Ota, H., Kiriya, D., Takei, K., Javey, A. (2019). Flexible electronics toward wearable sensing. Accounts of Chemical Research, 52(3), 523–533.10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00500Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Xu, K., Lu, Y., Takei, K. (2019). Multifunctional skin-inspired flexible sensor systems for wearable electronics. Advanced Materials Technologies, 4(3), 1800628.10.1002/admt.201800628Search in Google Scholar

[3] Jayathilaka, W. A. D. M., Qi, K., Qin, Y., Chinnappan, A., Serrano-García, W., Baskar, C., et al. (2019). Significance of nanomaterials in wearables: a review on wearable actuators and sensors. Advanced Materials, 31(7), 1805921.10.1002/adma.201805921Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Xie, M., Hisano, K., Zhu, M., Toyoshi, T., Pan, M., Okada, S., et al. (2019). Flexible multifunctional sensors for wearable and robotic applications. Advanced Materials Technologies, 4(3), 1800626.10.1002/admt.201800626Search in Google Scholar

[5] Dinh, T., Nguyen, T., Phan, H. P., Nguyen, N. T., Dao, D. V., Bell, J. (2020). Stretchable respiration sensors: Advanced designs and multifunctional platforms for wearable physiological monitoring. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 166, 112460.10.1016/j.bios.2020.112460Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Bariya, M., Nyein, H. Y. Y., Javey, A. (2018). Wearable sweat sensors. Nature Electronics, 1(3), 160–171.10.1038/s41928-018-0043-ySearch in Google Scholar

[7] Homayounfar, S. Z., Andrew, T. L. (2020). Wearable sensors for monitoring human motion: a review on mechanisms, materials, and challenges. Slas Technology: Translating Life Sciences Innovation, 25(1), 9–24.10.1177/2472630319891128Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Cutrone, A., Micera, S. (2019). Implantable neural interfaces and wearable tactile systems for bidirectional neuroprosthetics systems. Advanced Healthcare Materials, 8(24), 1801345.10.1002/adhm.201801345Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Fei, F., Xian, S., Xie, X., Wu, C., Yang, D., Yin, K., et al. (2021). Development of a wearable glove system with multiple sensors for hand kinematics assessment. Micromachines, 12(4), 362.10.3390/mi12040362Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Li, Y., Yang, L., He, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, H., Zhang, W., et al. (2022). Low-cost data glove based on deep-learning-enhanced flexible multiwalled carbon nanotube sensors for real-time gesture recognition. Advanced Intelligent Systems, 4(11), 2200128.10.1002/aisy.202200128Search in Google Scholar

[11] Irzmańska, E., Jastrzębska, A., Michalski, M. (2022). A biomimetic approach to protective glove design: inspirations from nature and the structural limitations of living organisms. Autex Research Journal, 23(1), 89–102.10.2478/aut-2022-0004Search in Google Scholar

[12] Silva, D. C., Paschoarelli, L. C., Medola, F. O. (2019). Evaluation of two wheelchair hand rim models: contact pressure distribution in straight line and curve trajectories. Ergonomics, 62(12), 1563–1571.10.1080/00140139.2019.1660000Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Si, Y., Chen, S., Li, M., Li, S., Pei, Y., Guo, X. (2022). Flexible strain sensors for wearable hand gesture recognition: from devices to systems. Advanced Intelligent Systems, 4(2), 2100046. 10.1002/aisy.202100046Search in Google Scholar

[14] Luo, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, J., Xiao, X., Li, Q., Ding, W., et al. (2021). Triboelectric bending sensor based smart glove towards intuitive multi-dimensional human-machine interfaces. Nano Energy, 89, 106330.10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.106330Search in Google Scholar

[15] Glauser, O., Wu, S., Panozzo, D., Hilliges, O., Sorkine-Hornung, O. (2019). Interactive hand pose estimation using a stretch-sensing soft glove. ACM Transactions on Graphics (ToG), 38(4), 1–15.10.1145/3306346.3322957Search in Google Scholar

[16] Sundaram, S., Kellnhofer, P., Li, Y., Zhu, J. Y., Torralba, A., Matusik, W. (2019). Learning the signatures of the human grasp using a scalable tactile glove. Nature, 569(7758), 698–702.10.1038/s41586-019-1234-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Zhang, X., Yang, Z., Chen, T., Chen, D., Huang, M. C. (2019). Cooperative sensing and wearable computing for sequential hand gesture recognition. IEEE Sensors Journal, 19(14), 5775–5783.10.1109/JSEN.2019.2904595Search in Google Scholar

[18] Dong, W., Yang, L., Gravina, R., Fortino, G. (2021). Soft wrist-worn multi-functional sensor array for real-time hand gesture recognition. IEEE Sensors Journal, 22(18), 17505–17514.10.1109/JSEN.2021.3050175Search in Google Scholar

[19] Lin, Y., Li, Y., Yao, L., Zhao, G., Wang, L. (2020). Effects of deep knee flexion on skin pressure profile with lower limb device: A computational study. Textile Research Journal, 90(17–18), 1962–1973.10.1177/0040517520902275Search in Google Scholar

[20] Dan, R., Shi, Z. (2021). Dynamic simulation of the relationship between pressure and displacement for the waist of elastic pantyhose in the walking process using the finite element method. Textile Research Journal, 91(13–14), 1497–1508.10.1177/0040517520981741Search in Google Scholar

[21] Chen, Y., Bruniaux, P., Sun, Y., Hong, Y. (2020). Modelization and identification of medical compression stocking: part 2–3D interface pressure modelization. Textile Research Journal, 90(19–20), 2184–2197.10.1177/0040517520913346Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hong, L., Dongsheng, C., Qufu, W., Ruru, P. (2011). A study of the relationship between clothing pressure and garment bust strain, and Young’s modulus of fabric, based on a finite element model. Textile Research Journal, 81(13), 1307–1319.10.1177/0040517510399961Search in Google Scholar

[23] Sun, Y., Yick, K. L., Yu, W., Chen, L., Lau, N., Jiao, W., et al. (2019). 3D bra and human interactive modeling using finite element method for bra design. Computer-Aided Design, 114, 13–27.10.1016/j.cad.2019.04.006Search in Google Scholar

[24] Harih, G., Kalc, M., Vogrin, M., Fodor-Mühldorfer, M. (2021). Finite element human hand model: Validation and ergonomic considerations. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 85, 103186.10.1016/j.ergon.2021.103186Search in Google Scholar

[25] Harih, G., Tada, M. (2019). Development of a feasible finite element digital human hand model. In DHM and Posturography (pp. 273–286). Academic Press.10.1016/B978-0-12-816713-7.00021-0Search in Google Scholar

[26] Harih, G. (2019). Development of a tendon driven finger joint model using finite element method. In Advances in Human Factors in Simulation and Modeling: Proceedings of the AHFE 2018 International Conferences on Human Factors and Simulation and Digital Human Modeling and Applied Optimization, Held on July 21–25, 2018, in Loews Sapphire Falls Resort at Universal Studios, Orlando, Florida, USA 9 (pp. 463–471). Springer International Publishing.10.1007/978-3-319-94223-0_44Search in Google Scholar

[27] Hokari, K., Arimoto, R., Pramudita, J. A., Ito, M., Noda, S., Tanabe, Y. (2019). Palmar contact pressure distribution during grasping a cylindrical object: parameter study using hand finite element model. Advanced Experimental Mechanics, 4, 135–140.10.1299/jsmeatem.2019.1008D0915Search in Google Scholar

[28] Wu, J. Z., Dong, R. G., Rakheja, S., Schopper, A. W. (2002). Simulation of mechanical responses of fingertip to dynamic loading. Medical Engineering & Physics, 24(4), 253–264.10.1016/S1350-4533(02)00018-8Search in Google Scholar

[29] Yeung, K. W., Li, Y., Zhang, X. (2004). A 3D biomechanical human model for numerical simulation of garment-body dynamic mechanical interactions during wear. The Journal of The Textile Institute, 95(1–6), 59–79.10.1533/joti.2001.0050Search in Google Scholar

[30] Hendriks, F. M., Brokken, D., Oomens, C. W. J., Baaijens, F. P. T. (2004). Influence of hydration and experimental length scale on the mechanical response of human skin in vivo, using optical coherence tomography. Skin Research and Technology, 10(4), 231–241.10.1111/j.1600-0846.2004.00077.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Liang, X., Boppart, S. A. (2009). Biomechanical properties of in vivo human skin from dynamic optical coherence elastography. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 57(4), 953–959.10.1109/TBME.2009.2033464Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Yu, A., Yick, K. L., Ng, S. P., Yip, J., Chan, Y. F. (2016). Numerical simulation of pressure therapy glove by using finite element method. Burns, 42(1), 141–151.10.1016/j.burns.2015.09.013Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Wei, Y., Zou, Z., Wei, G., Ren, L., Qian, Z. (2020). Subject-specific finite element modelling of the human hand complex: muscle-driven simulations and experimental validation. Annals of Biomedical Engineering, 48, 1181–1195.10.1007/s10439-019-02439-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2024 by the authors, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Characterization of viscoelastic properties of yarn materials: Dynamic mechanical analysis in the transversal direction

- Analysis of omni-channel implementations that are preferred by consumers in clothing sector

- Structural modeling and analysis of three-dimensional cross-linked braided preforms

- An experimental study of mechanical properties and comfortability of knitted imitation woven shirt fabrics

- Technology integration to promote circular economy transformation of the garment industry: a systematic literature review

- Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks

- Research on She nationality clothing recognition based on color feature fusion with PSO-SVM

- Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves

- Preparation and performance of stainless steel fiber/Lyocell fiber-blended weft-knitted fabric

- Development of an emotional response model for hospital gown design using structural equation modeling

- Preparation and properties of stainless steel filament/pure cotton woven fabric

- Facemask comfort enhancement with graphene oxide from recovered carbon waste tyres

- Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials

- Optical-related properties and characterization of some textile fibers using near-infrared spectroscopy

- Network modeling of aesthetic effect for Chinese Yue Opera costume simulation images

- Predicting consumers’ garment fit satisfactions by using machine learning

- Non-destructive identification of wool and cashmere fibers based on improved LDA using NIR spectroscopy

- Study on the relationship between structure and moisturizing performance of seamless knitted fabrics of protein fibers for autumn and winter

- Antibacterial and yellowing performances of sports underwear fabric with polyamide/silver ion polyurethane filaments

- Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics

- Phonetic smart clothing design based on gender awareness education for preschoolers

- Determination of anthropometric measurements and their application in the development of clothing sizing systems for women in the regions of the Republic of Croatia

- Research on optimal design of pleated cheongsam based on Kano–HOQ–Pugh model

- Numerical investigation of weaving machine heald shaft new design using composite material to improve its performance

- Corrigendum to “Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials”

- Shaping of thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites by direct surface modification using magnetron sputtering technique

- Numerical modeling of the heat flow component of the composite developed on the basis of basalt fabric

- Weft insertion guideway design based on high-temperature superconducting levitation

- Ultrasonic-assisted alkali hydrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate fabric and its effect on the microstructure and dyeing properties of fibers

- Comparative study on physical properties of bio-based PA56 fibers and wearability of their fabrics

- Investigation of the bias tape roll change time efficiency in garment factories

- Analysis of foot 3D scans of boys from Polish population

- Optimization of garment sewing operation standard minute value prediction using an IPSO-BP neural network

- Influence of repeated switching of current through contacts made of electroconductive fabrics on their resistance

- Numerical calculation of air permeability of warp-knitted jacquard spacer shoe-upper materials based on CFD

- Compact Spinning with Different Fibre Types: An Experimental Investigation on Yarn Properties in the Condensing Zone with 3D-Printed Guiding Device

- Modeling of virtual clothing and its contact with the human body

- Advances in personalized modelling and virtual display of ethnic clothing for intelligent customization

- Investigation of weave influence on flame retardancy of jute fabrics

- Balloonless spinning spindle head shape optimisation

- Research on 3D simulation design and dynamic virtual display of clothing flexible body

- Turkish textile and clothing SMEs: Importance of organizational learning, digitalization, and internationalization

- Corrigendum To: “Washing characterization of compression socks”

- Study on the promotion multiple of blood flow velocity on human epidermal microcirculation of volcanic rock polymer fiber seamless knitted fabric

- Bending properties and numerical analysis of nonorthogonal woven composites

- Bringing the queen mother of the west to life: Digital reconstruction and analysis of Taoist Celestial Beings Worshiping mural’s apparel

- Modeling process for full forming sports underwear

- Retraction of: Ionic crosslinking of cotton

- An observational study of female body shape characteristics in multiracial Malaysia

- Study on theoretical model and actual deformation of weft-knitted transfer loop based on particle constraint

- Design and 3D simulation of weft-knitted jacquard plush fabrics

- An overview of technological challenges in implementing the digital product passport in the textile and clothing industry

- Understanding and addressing the water footprint in the textile sector: A review

- Determinants of location changes in the clothing industry in Poland

- Influence of cam profile errors in a modulator on the dynamic response of the heald frame

- Quantitative analysis of wool and cashmere fiber mixtures using NIR spectroscopy

- 3D simulation of double-needle bar warp-knitted clustered pile fabrics on DFS

- Finite element analysis of heat transfer behavior in glass fiber/metal composite materials under constant heat load

- Price estimation and visual evaluation of actual white fabrics used for dress shirts and their photographic images

- Effect of gluing garment materials with adhesive inserts on their multidirectional drape and bending rigidity

- Optimization analysis of carrier-track collision in braiding process

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the ballistic performance of soft bulletproof vests for women

- The antimicrobial potential of plant-based natural dyes for textile dyeing: A systematic review using prisma

- Influence of sewing parameters on the skin–fabric friction

- Validation by experimental study the relationship between fabric tensile strength and weave structures

- Optimization of fabric’s tensile strength and bagging deformation using surface response and finite element in stenter machine

- Analysis of lean manufacturing waste in the process flow of ready-to-wear garment production in Nigeria

- An optimization study on the sol–gel process to obtain multifunctional denim fabrics

- Drape test of fully formed knitted flared skirts based on 3D-printed human body posture

- Supplier selection models using fuzzy hybrid methods in the clothing textile industry

Articles in the same Issue

- Characterization of viscoelastic properties of yarn materials: Dynamic mechanical analysis in the transversal direction

- Analysis of omni-channel implementations that are preferred by consumers in clothing sector

- Structural modeling and analysis of three-dimensional cross-linked braided preforms

- An experimental study of mechanical properties and comfortability of knitted imitation woven shirt fabrics

- Technology integration to promote circular economy transformation of the garment industry: a systematic literature review

- Research on T-shirt-style design based on Kansei image using back-propagation neural networks

- Research on She nationality clothing recognition based on color feature fusion with PSO-SVM

- Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves

- Preparation and performance of stainless steel fiber/Lyocell fiber-blended weft-knitted fabric

- Development of an emotional response model for hospital gown design using structural equation modeling

- Preparation and properties of stainless steel filament/pure cotton woven fabric

- Facemask comfort enhancement with graphene oxide from recovered carbon waste tyres

- Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials

- Optical-related properties and characterization of some textile fibers using near-infrared spectroscopy

- Network modeling of aesthetic effect for Chinese Yue Opera costume simulation images

- Predicting consumers’ garment fit satisfactions by using machine learning

- Non-destructive identification of wool and cashmere fibers based on improved LDA using NIR spectroscopy

- Study on the relationship between structure and moisturizing performance of seamless knitted fabrics of protein fibers for autumn and winter

- Antibacterial and yellowing performances of sports underwear fabric with polyamide/silver ion polyurethane filaments

- Numerical and experimental analysis of ballistic performance in hybrid soft armours composed of para-aramid triaxial and biaxial woven fabrics

- Phonetic smart clothing design based on gender awareness education for preschoolers

- Determination of anthropometric measurements and their application in the development of clothing sizing systems for women in the regions of the Republic of Croatia

- Research on optimal design of pleated cheongsam based on Kano–HOQ–Pugh model

- Numerical investigation of weaving machine heald shaft new design using composite material to improve its performance

- Corrigendum to “Use of enzymatic processes in the tanning of leather materials”

- Shaping of thermal protective properties of basalt fabric-based composites by direct surface modification using magnetron sputtering technique

- Numerical modeling of the heat flow component of the composite developed on the basis of basalt fabric

- Weft insertion guideway design based on high-temperature superconducting levitation

- Ultrasonic-assisted alkali hydrolysis of polyethylene terephthalate fabric and its effect on the microstructure and dyeing properties of fibers

- Comparative study on physical properties of bio-based PA56 fibers and wearability of their fabrics

- Investigation of the bias tape roll change time efficiency in garment factories

- Analysis of foot 3D scans of boys from Polish population

- Optimization of garment sewing operation standard minute value prediction using an IPSO-BP neural network

- Influence of repeated switching of current through contacts made of electroconductive fabrics on their resistance

- Numerical calculation of air permeability of warp-knitted jacquard spacer shoe-upper materials based on CFD

- Compact Spinning with Different Fibre Types: An Experimental Investigation on Yarn Properties in the Condensing Zone with 3D-Printed Guiding Device

- Modeling of virtual clothing and its contact with the human body

- Advances in personalized modelling and virtual display of ethnic clothing for intelligent customization

- Investigation of weave influence on flame retardancy of jute fabrics

- Balloonless spinning spindle head shape optimisation

- Research on 3D simulation design and dynamic virtual display of clothing flexible body

- Turkish textile and clothing SMEs: Importance of organizational learning, digitalization, and internationalization

- Corrigendum To: “Washing characterization of compression socks”

- Study on the promotion multiple of blood flow velocity on human epidermal microcirculation of volcanic rock polymer fiber seamless knitted fabric

- Bending properties and numerical analysis of nonorthogonal woven composites

- Bringing the queen mother of the west to life: Digital reconstruction and analysis of Taoist Celestial Beings Worshiping mural’s apparel

- Modeling process for full forming sports underwear

- Retraction of: Ionic crosslinking of cotton

- An observational study of female body shape characteristics in multiracial Malaysia

- Study on theoretical model and actual deformation of weft-knitted transfer loop based on particle constraint

- Design and 3D simulation of weft-knitted jacquard plush fabrics

- An overview of technological challenges in implementing the digital product passport in the textile and clothing industry

- Understanding and addressing the water footprint in the textile sector: A review

- Determinants of location changes in the clothing industry in Poland

- Influence of cam profile errors in a modulator on the dynamic response of the heald frame

- Quantitative analysis of wool and cashmere fiber mixtures using NIR spectroscopy

- 3D simulation of double-needle bar warp-knitted clustered pile fabrics on DFS

- Finite element analysis of heat transfer behavior in glass fiber/metal composite materials under constant heat load

- Price estimation and visual evaluation of actual white fabrics used for dress shirts and their photographic images

- Effect of gluing garment materials with adhesive inserts on their multidirectional drape and bending rigidity

- Optimization analysis of carrier-track collision in braiding process

- Numerical and experimental analysis of the ballistic performance of soft bulletproof vests for women

- The antimicrobial potential of plant-based natural dyes for textile dyeing: A systematic review using prisma

- Influence of sewing parameters on the skin–fabric friction

- Validation by experimental study the relationship between fabric tensile strength and weave structures

- Optimization of fabric’s tensile strength and bagging deformation using surface response and finite element in stenter machine

- Analysis of lean manufacturing waste in the process flow of ready-to-wear garment production in Nigeria

- An optimization study on the sol–gel process to obtain multifunctional denim fabrics

- Drape test of fully formed knitted flared skirts based on 3D-printed human body posture

- Supplier selection models using fuzzy hybrid methods in the clothing textile industry