Abstract

Homogenization of pigment is the key to coloring a plastic product evenly. In this article, the tensile properties of recovered carbon black merge with low molecular weight lubricants and other compounding ingredients in the form of pigment masterbatch (PM) added in a recycled low-density polyethylene (rLDPE) resin were evaluated. The prepared masterbatch with the varying amount and types of processing aids (A and B) was first compounded using the heated two-roll mill. Subsequently, the manually mixed masterbatch in rLDPE was put through an injection molding machine for the shaping process to produce an rLDPE pigment masterbatch composite (PMC). The tensile test was performed on the samples to evaluate the mechanical properties of the PMC. Meanwhile, the melt flow index test was executed to justify the composite flow characteristics. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy analysis and scanning electron microscopy were also carried out to analyze the PM and PMC chemical properties and their constructed surface morphology. Besides, X-ray diffraction analysis was performed to determine the changes in degree of crystallinity before and after the water absorption test. The addition of PM in rLDPE has slightly increased the rLDPE matrix tensile properties. While, the usage of more processing aid B in the PMC has turned out to secure better tensile properties compared to the addition of higher amount of processing aid A in the PMC. Interestingly, the tensile properties of all composites after the water absorption test were enhanced, suggesting that a stronger bond was formed during the immersion period.

1 Introduction

Numerous plastic products made from recycled polyolefin are found on the market today. Besides polyolefin recycling, automotive tyre recycling has gained much interest because of its various potential applications (1,2,3). The crosslink between the polymer structures is the most common obstacle to tyre disposal. Still, with the advancement of polymer composite studies, tyre waste recycling has now become feasible. To date, researchers have incorporated tyre dust as fillers in polymeric resins. Recently, Ramarad and coworkers blended the reclaimed tyre with poly(ethylene-co-vinyl acetate) (EVA) and observed that the addition of reclaimed tyre dust managed to improve the EVA composite thermal and mechanical properties (2). Since waste tyres contain a high amount of carbon black, there has been an attempt to recover the carbon black from tyre waste via pyrolysis, which led to the name “recovered carbon black” (rCB) (3).

Studies have shown that long-term exposure to UV radiation can negatively affect mechanical properties, increase the gel content, alter polymer structure, and initiate cracks in clear thermoplastic (4). In previous work, about 2–3% of carbon black are dispersed in resins as a colorant or pigment to control the photodegradation effect and UV protection (5). Well-dispersed carbon black particles with a particle size of less than 20 nm in polyethylene can absorb almost all UV radiation under sunlight for several years (6). Apart from that, adding rCB as fillers in polyolefin has demonstrated a reinforcing effect where the composites show comparable hardness, tear, and tensile strength compared to CB. Martinez and coworkers proclaimed that their demineralized rCB in SBR shows a reinforcing effect due to higher specific surface area and richer rCB chemical surface (7). Meanwhile, Chen’s group also reported that the thermal stability of rCB/PP composites rose as more carbon ash content was added (8).

The reinforcing effect of rCB and other compounding ingredients can be executed through satisfactory component dispersion and distribution. To accomplish it, researches will typically add in a small amount of low molecular weight materials of compatibilizer, plasticizer, and lubricant in their composite system (9,10). These processing aids act as flow enhancers, reducing the entire polymer melt viscosity. The low melt strength will yield better mobility for the added component to distance while sliding in between the long polymer chain during processing (11). Apart from that, the addition of compatibilizer has proven to promote interfacial connectivity between different phases of polymer blends and fillers (12,13). Recently, Lohar and colleagues demonstrated a refine morphology of compatibilized PP/ABS with CB composites leading to improvement in the composite tensile strength (14).

Throughout the years, the polar nature of carbon black particles in powder form has always been an issue because of their laborious handling, transportation, and health risks (15). For that reasons, it is more convenient for industrial players to use the pigmented masterbatch in the form of a pallet to color their product. In this article, we compiled the rCB, processing aids, and other ingredients to form a pigmented masterbatch (PM) by using recycled low-density polyethylene (rLDPE) as a carrier resin. The pigmented masterbatch with a different portion of processing aid A and processing aid B was first compounded via the heated two-roll mill and later added in rLDPE resin during the injection molding process. Next, the tensile properties of the specimens were evaluated, and other tests were also carried out to seek a correlation between the obtained results.

2 Materials and methods

All raw materials were supplied by Ecopower Synergy Sdn. Bhd, except for zinc stearate. Calcium carbonate with the mean particle size of 325 mesh was used as extender in the masterbatch. Low molecular weight processing aid A with the chemical formula of C38H76N2O2 with alcohol functional group attached, taking shape in powder form. Whereas processing aid B is PE wax with carbon and hydrogen element building unit. The rCB and all ingredients were compounded with rLDPE resin as binder to produce a pigment rLDPE masterbatch (PM). The rCB was obtained from waste tires through pyrolysis process with a mean particle size of 1,200 mesh. Meanwhile, zinc stearate was purchased from Chemplass. Based on the ashing test results, about 0.008% of non-burned residues were presented in rLDPE.

2.1 Pigment rLDPE masterbatch (PM) preparation

The PM was designed according to the formulation in Table 1 and an industrial Retrofit two-roll (Chaeng Co) was used to produce the masterbatches. All ingredients were carefully placed between the roll mill with a constant processing temperature of 180°C for 30 min at 35 rpm rolling speed. Subsequently, the PM was crushed using an industrial crusher (Gap Ecotech) until the sample was turned into small flakes ranging from 0.2 to 4 mm in diameter.

Formulation for PM

| *phr | PM control | PM A | PM B |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDPE resin | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| rCB | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| CaCO3 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Zinc stearate | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Processing aid A | 8 | 28 | 8 |

| Processing aid B | 20 | 20 | 40 |

*phr represents part per hundred resin.

2.2 Pigment rLDPE masterbatch composite (PMC) preparation

The tensile test dumbbell specimens for PMC were prepared by using the BOY 22M Procan injection molding machine. Initially, the manually mixed PM (2 and 4 phr) with rLDPE pellets were placed into the hopper and the PMC was injected into the mold at 190°C using 125 bar of pressure within 2.5 s cycle time for all samples. The cooling time was fixed for 20 s.

2.3 Testing and characterization

The tensile properties of the PMC dumbbell were tested using the Instron-UTM Model 5960 Series machine according to ASTM D638. The melt flow index (MFI) value of the PMC was evaluated using GT-7100 Gotech melt flow indexer in accordance with ASTM D 1238-90b standard using 2.16 kg of load at 180°C. MFI is defined as the extrudate weight (W) in grams per 10 min. The Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) absorption spectra of the PM and PMC were obtained using Agilent 4500a portable FTIR 103 spectrometers (Santa Clara, CA). Attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode was used with 4 cm−1 resolution, 64 scans, and spectral wavelengths ranging from 650 to 4,000 cm−1 for each sample. Finally, a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) test was conducted using the Model JEOL JSM-6460LA machine with 10 kV in voltage. The PM ash content test was performed according to ASTM 1506 at 750°C for 3 h. Meanwhile, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) test was conducted by utilizing the Rigaku X-ray diffractometer, Model Smartlab 2018 (Tokyo, Japan). The measurements were recorded with a Cu Kα radiation at a scan rate of 0.1 s per step in the range of 2θ = 2–90°. From the obtained graph, the PMC degree of crystallinity is determined by calculating the ratio of the areas of the crystalline peaks to the total generated area from the graph. As for the water absorption effect on the PMC, the PMC was immersed in distilled water for 2 weeks before a tensile test was performed. The crystallization temperature (T c) of PMC B before and after the absorption test was measured by using the Perkin Elmer differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). The heating rates were set up at 10°C‧min−1.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 The effect of processing aids

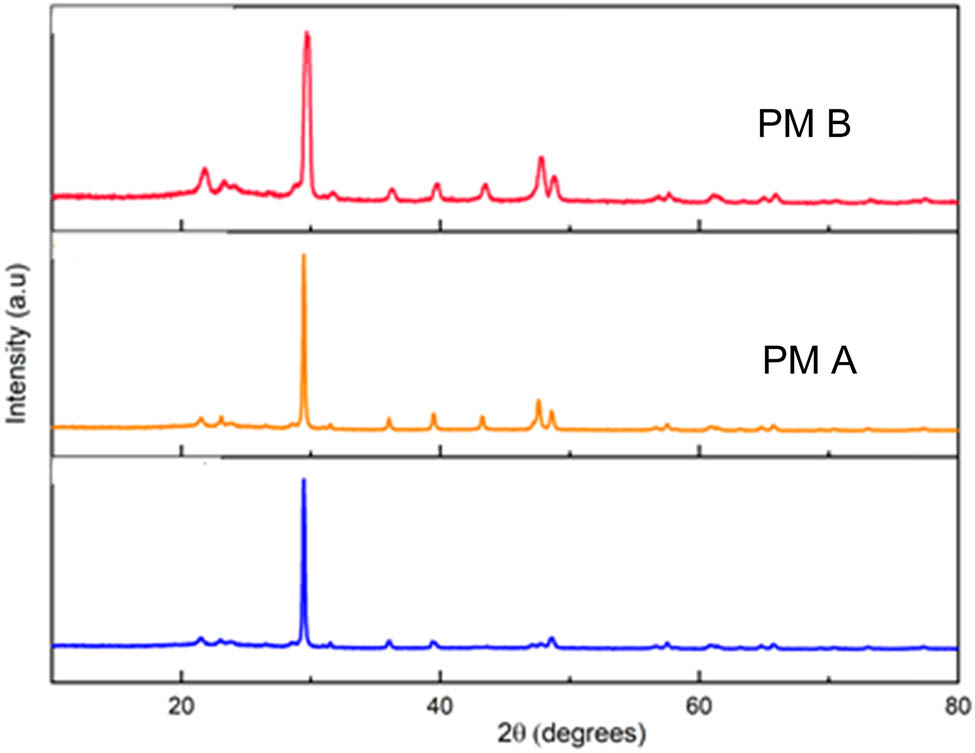

Initially, the prepared PM was manually mixed in rLDPE resin according to the formulated formulations before transferring it into an injection molding hopper for the shaping process. Based on the eyewitness evidence in Figure 1 for samples with 2 phr pigment masterbatch rLDPE composites (PMC control, PMC A, and PMC B), a well-dispersed rCB in rLDPE resin was observed for all samples. These indicate that the prepared PM has successfully dispersed and works as a pigment in the rLDPE resin. The results are displayed in Figure 1. The FTIR and XRD results for all PM are displayed in Figures A1 and A2.

Fabrication process for PMC dumbbell samples for tensile test.

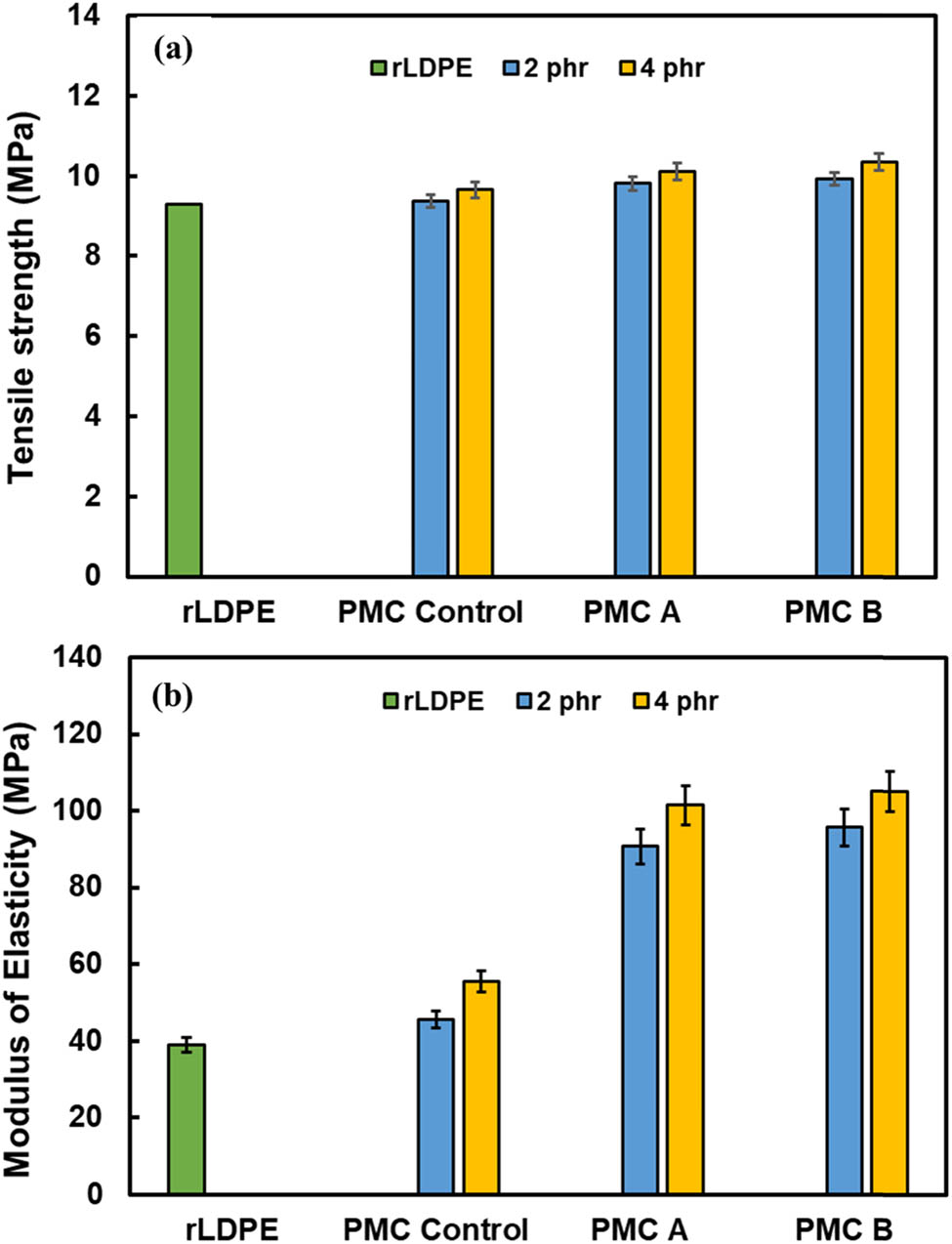

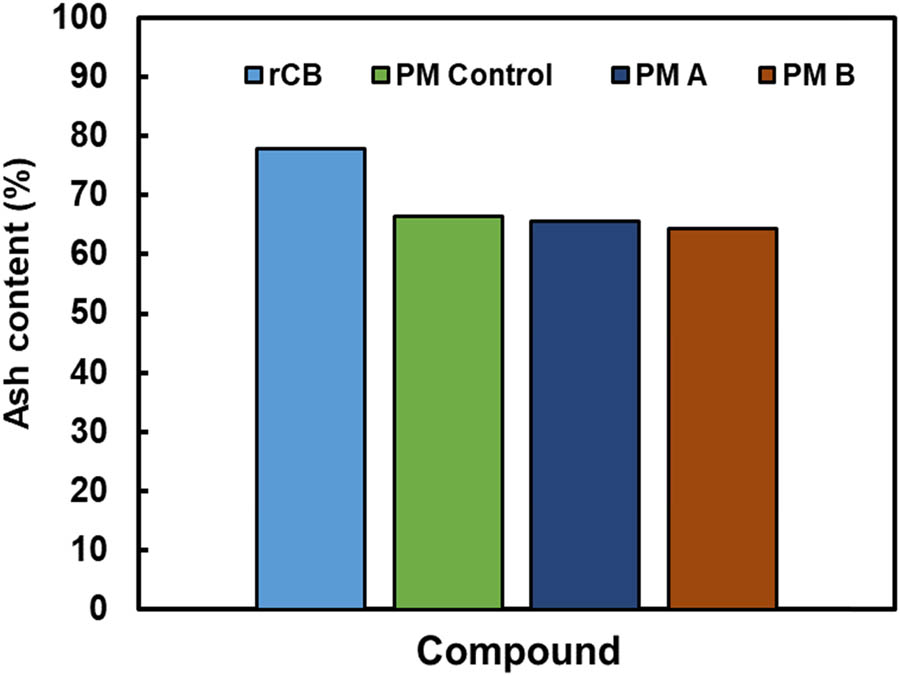

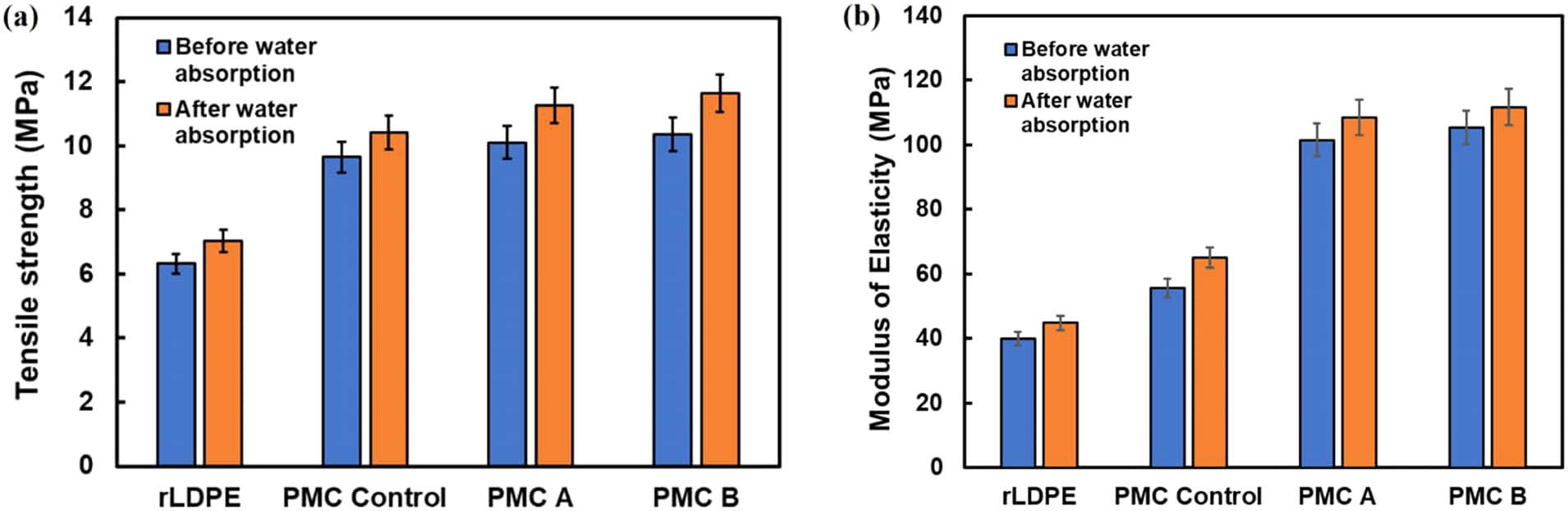

Meanwhile, Figure 2a presents the tensile properties for neat rLDPE, PMC control, PMC A, and PMC B. The results indicate that further increases in PM loading for all samples have consistently enhanced the tensile strength of the PMC system. The usage of 4 phr PM indicates the highest tensile strength compared to 2 phr PM in rLDPE, followed by neat rLDPE resin. The reason could be due to the presence of rCB and other foreign substance dispersed in the PM acting as reinforcing fillers or agent in rLDPE, which permits better tensile strength to the PMC dumbbell samples (15,16). To support the findings, the ash content test was performed to verify the amount of rCB and other foreign substance in the PM, and the results are disclosed in Figure 3. Recently, Alshangiti identified that adding a small amount of CB in irradiated natural rubber/butyl rubber blend has markedly increased their composite tensile strength. The reason is due to the occluded structure of CB with a high surface area initiating the formation of physical bonds between incorporated fillers and the rLDPE chains (17).

Tensile strength (a) and modulus of elasticity (b) of rLDPE and PMCs with 2 and 4 phr PM loading.

Ash content for rCB, PM control, PM A and PM B.

It is also noticed that the employment of PM B in rLDPE is preferable in providing better tensile strength to the rLDPE rather than using PM A and PM control. Despite that, an obvious increase was noticed for PMC B modulus of elasticity (Figure 2b). The 4 phr PMC B indicates the strongest tensile strength and modulus of elasticity with 10.35 and 105.25 MPa compared to 4 phr PMC A with 10.13 and 98.63 MPa, respectively. According to Gumede and colleagues, low molecular weight processing aids with similar functional groups are easily associated as well as imply a complete or partially miscible blend with LDPE. This has correspondingly reduced the overall matrix phase separation (9,10). Incorporating more processing aid B, comprised of C- and H- even in a small proportion, may have lessened the phase separation between the added materials in the rLDPE matrix. Hence, it will efficiently anticipate better interaction between rCB and rLDPE matrix, which eventually gives rise to better tensile properties to the PMC B compared to PMC control.

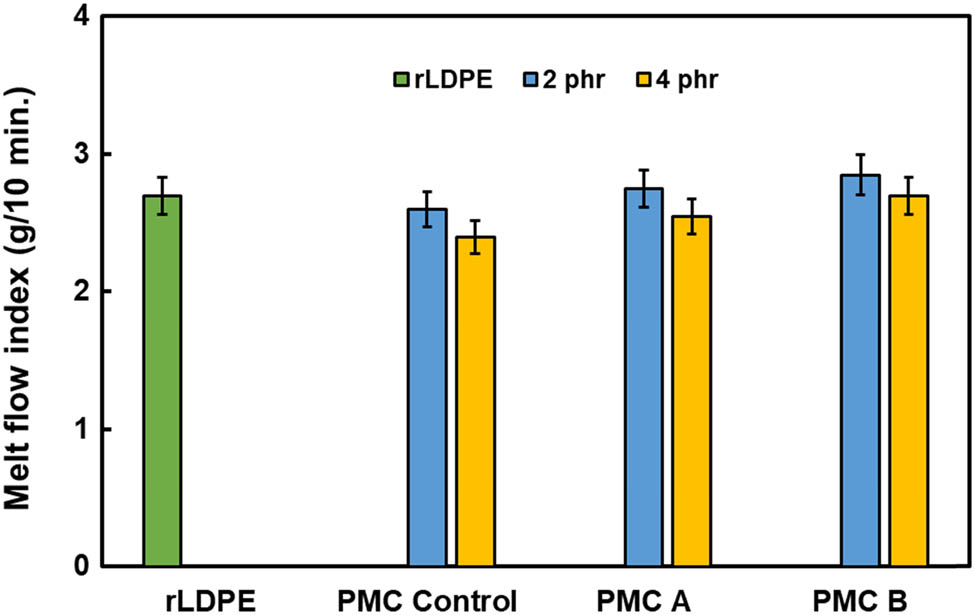

Furthermore, the variation in melt flow behavior of neat rLDPE resin and all PMC is shown in Figure 4. The MFI value did not change much when 2 phr PM was added into rLDPE. Indeed, for 2 phr PMC, PMC A shows a slight increase in MFI value with 2.83 g/10 min and 2.91 g/10 min for PMC B compared to 2.67 g/10 min for rLDPE. This was due to the effect of the lower molecular weight compound of the processing aids added in rLDPE, which has yielded better flow to the rLDPE composites. As the amount of PM increases to 4 phr, the PMC becomes more resistant to deformation due to the higher filler loading. The ease of melt flow depends upon the mobility of the molecular chains and the forces or entanglements holding the molecules together (4,13). Therefore, when higher foreign substance occupies in form of ashes, this will cause obstruction in the rLDPE composites and subsequently slightly elevate the compound MFI value.

MFI value for rLDPE and PMCs with 2 phr and 4 phr PM loading.

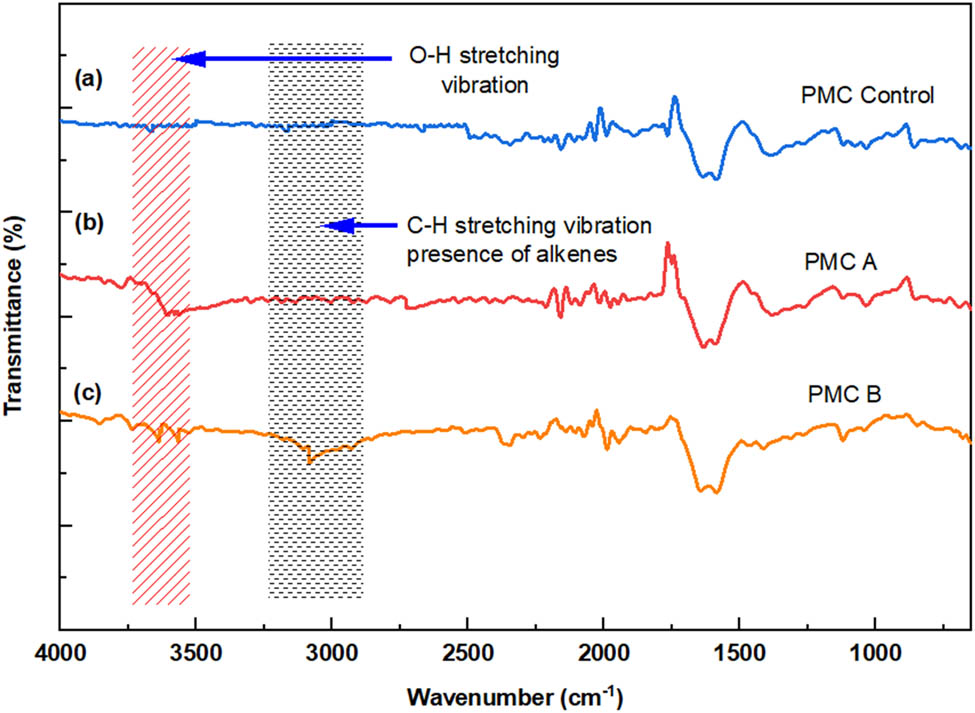

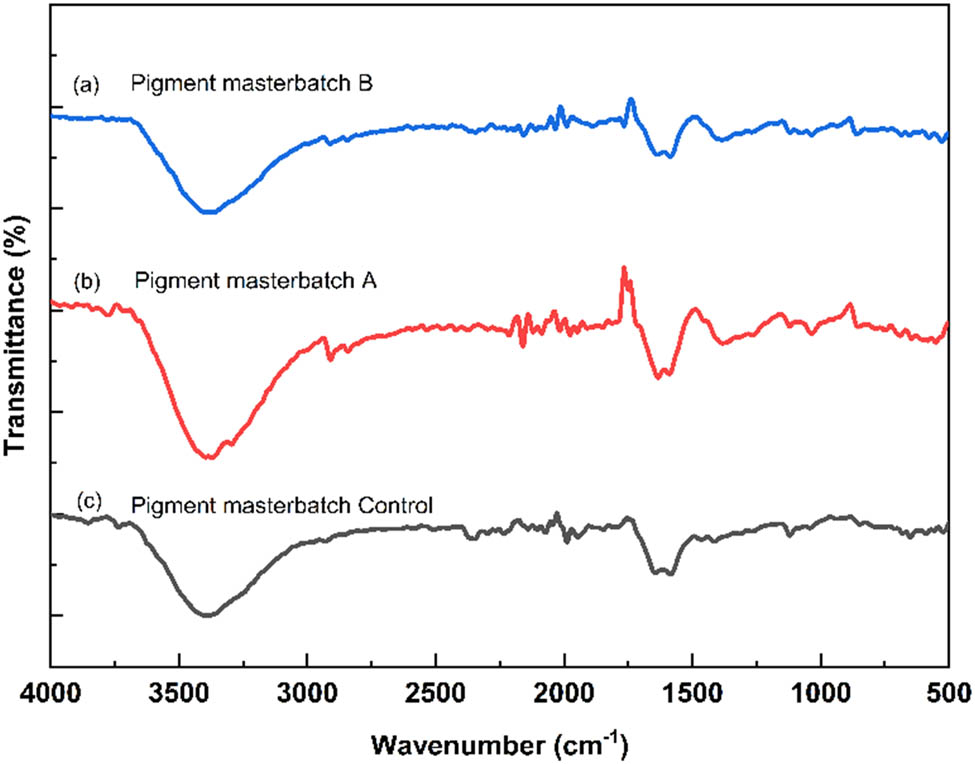

Besides, FTIR test was conducted for all PMC to seek the proper correlation, and the results are illustrated in Figure 5. It was detected that a strong O–H stretching appeared at wavenumber ranging from 3,700 to 3,600 cm−1 for PMC A and PMC B, respectively. The emergence of the alcohol group was directly came from processing aid A. PMC A with the highest amount of processing aid A indicates the most severe O–H group peak compared to PMC B. The O–H stretching for PMC B was contributed by the oxidized processing aid B during the sample shaping process. The low molecular processing aid B in the form of wax is vulnerable toward oxidation and temperatures (14). Thus, this suggests that the wax could have degraded during PMC B processing.

FTIR spectra of 4 phr of (a) PMC control, (b) PMC A, and (c) PMC B.

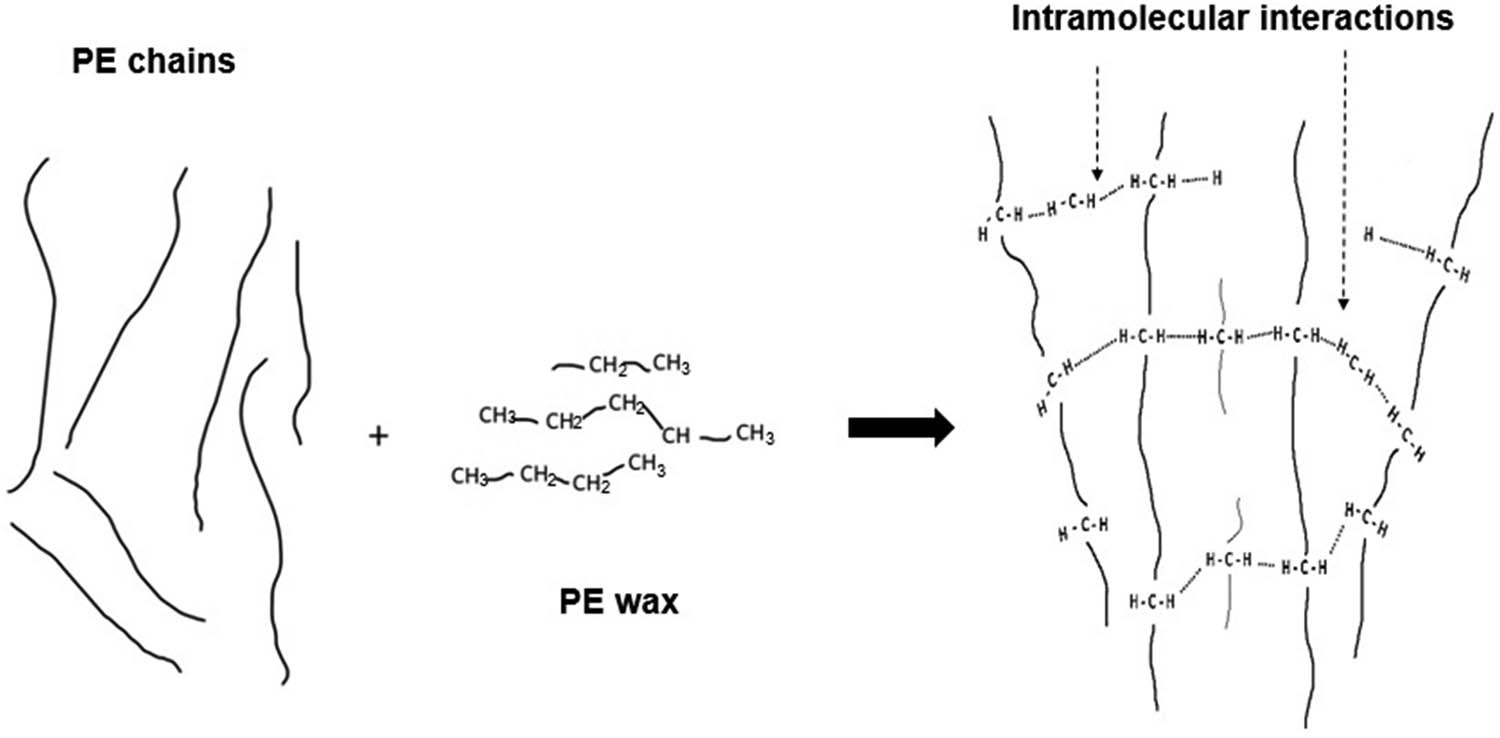

The FTIR graph also showed that the emergence of stronger IR spectra of alkenes was characterized by one or more C–H stretching peaks between 3,100 and 3,000 cm−1 presented for PMC B. The formation of intermolecular rigid π-bonds of alkenes provides a supporting reinforcement to the PMC B, enabling it to withstand better stress–strain deformation during tensile testing. In addition, the addition of more processing aid B, made of carbon and hydrogen elements in PMC B, could have triggered a higher formation of intramolecular bonds in rLDPE as illustrated in Figure 6. The C–H stretching can stipulate additional forces of Van der Waals’ bonds, C–H interaction, hydrogen bonding, and other weak forces surrounding the polymer chain, which simultaneously promote better tensile strength than control PMC. Previously, the Luyt group conducted a computer simulation of thermo-mechanical properties of LLDPE/wax blends and disclosed that the addition of wax increases the Van der Waals’ bonds between the wax crystals and the LLDPE chains. This has decreased in the LLDPE chains’ mobility and increased the sample stiffness (12,18). In line with the claim, the addition of a higher amount of processing aid B gives rise to better tensile properties for PMC B compared to PMC control.

Intramolecular interactions between PE chains and PE wax that form physical crosslinking.

3.2 The effect of water absorption

Since PE is largely used in the packaging industry, the water absorption test is important as moisture induces property changes in polymers, especially for filled PE. Figure 7 reveals the tensile properties of neat rLDPE and the PMC filled with 2 and 4 phr PM before and after the water absorption test. The mechanical strength of the rLDPE resin, 2 and 4 phr PMC control, PMC A, and PMC B manifests a slight increase in tensile strength after the water absorption test. The PMC B signifies the highest tensile strength (Figure 7a) of 11.98 MPa, followed by the PMC A with 11.57 MPa after the water absorption test. The value is slightly higher than PMC control (10.352 MPa). Proportionately, Figure 7b also suggests that an increase in the amount of PM A in PMC A and PM B in PMC B will enhance the modulus of elasticity for the composite after the water absorption test (19). This could be potentially attributed to the swelling of the added ingredients that might have occupied void spaces in the samples during manufacturing process. rLDPE consists of a small portion of contaminant; thus, the swelling of the substance can eventually lead to an improvement of the mechanical properties (20,21).

Tensile strength (a) and tensile modulus (b) of 4 phr PM for PMC control, PMC A, and PMC B before and after water absorption test.

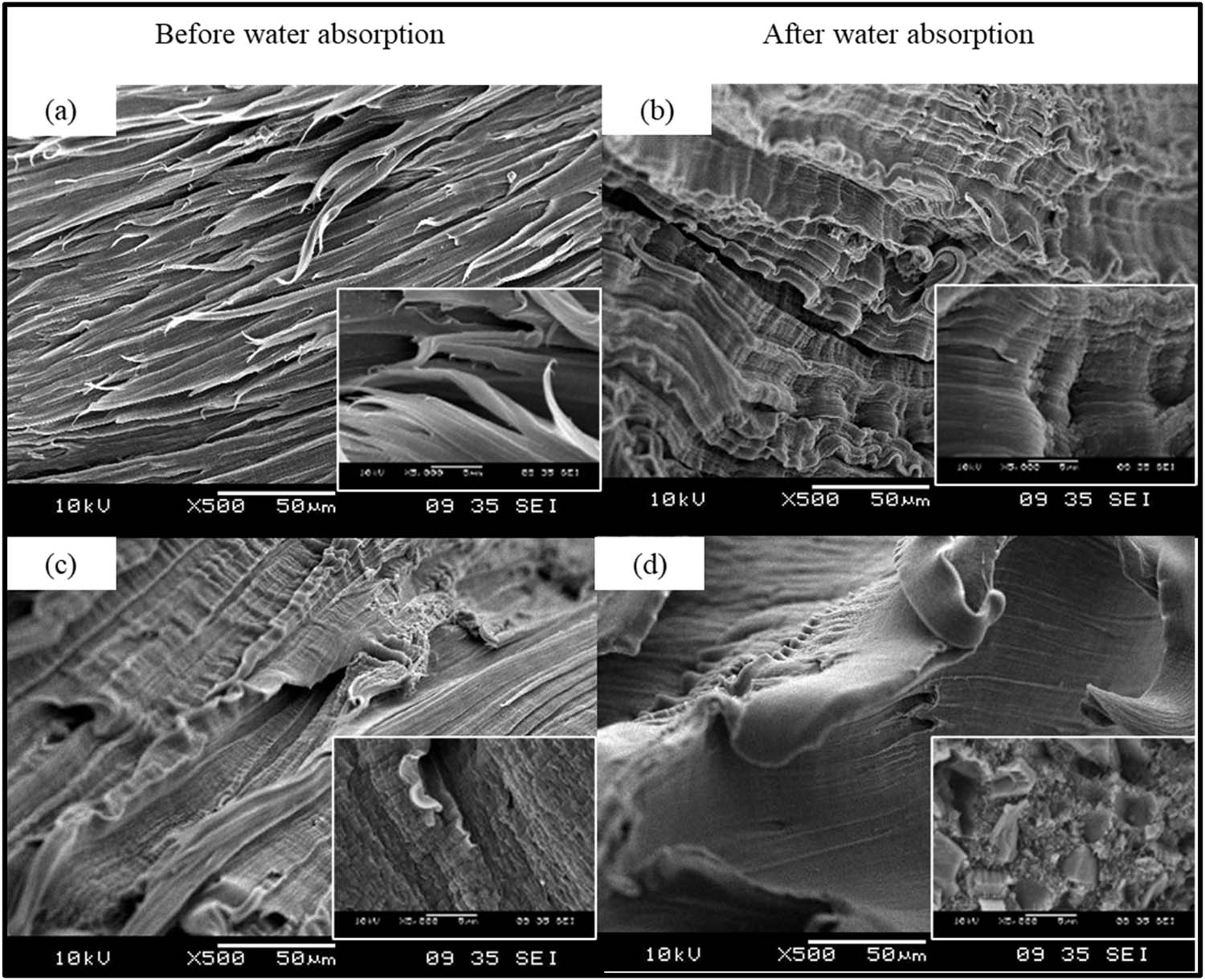

Figure 8 shows the micrographs of the PMC A and PMC B tensile fracture before and after the water absorption test. Hairy-like deformation was seen for PMC A before the water absorption test in Figure 8a. Meanwhile, after the absorption test, a wrinkle-like surface structure (Figure 8b) with no apparent rLDPE polymer chain breakage in the samples concludes that a better polymer chain interaction is achieved in the rLDPE chains. The presence of strong O–H stretching in PMC A might have associated well and could have formed a proper bonding with rLDPE chains after the water absorption process, hence yielding better tensile strength that can withstand deformation under loading (22,23).

Tensile fracture surface SEM morphology of 4 phr PM for (a and b) PMC A and (c and d) PMC B before and after water absorption test.

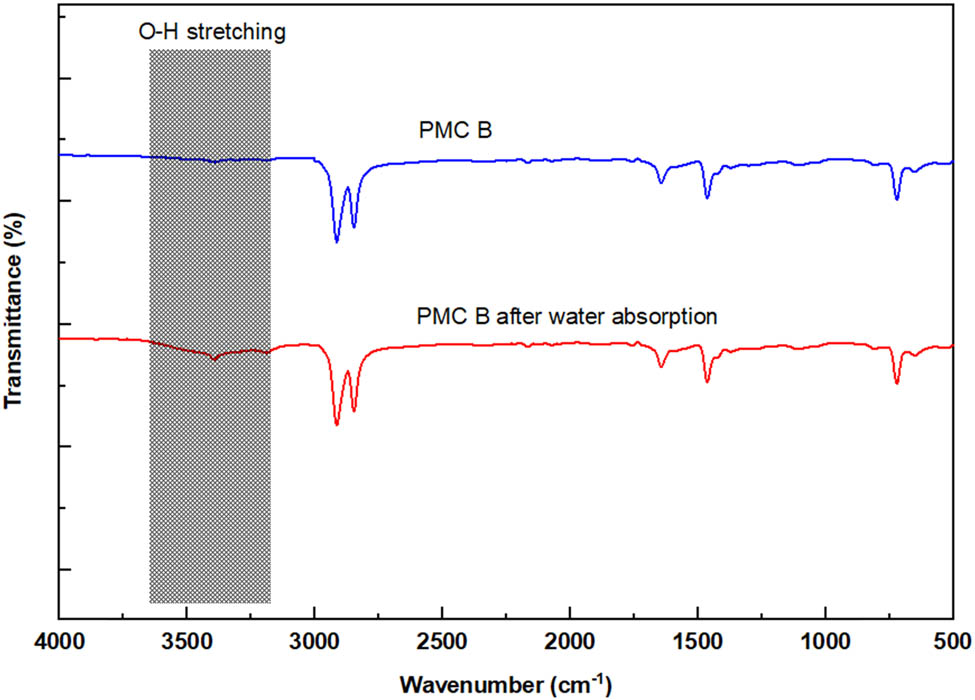

On the other hand, the addition of more processing aid B in PMC B reveals an exceptionally good interaction among the rLDPE chains, as in Figure 8c, due to its compatibility between processing aid B and rLDPE. After the water absorption process, it can be seen that the fracture surface of PMC B becomes smoother with less rLDPE chain pull out depicted in Figure 8d. To carefully verify the cause, the FTIR and XRD tests were conducted on PMC B. The FTIR test result is enclosed in Figure 9. It can identify that the formation of O–H stretching vibration became more severe after the water absorption test. According to Ali and coworkers, O–H stretching region of the hydroxylic group is caused by the formation of hydroperoxide and alcohol and the existence of water. Another contributing factor could be the degradation of rLDPE itself (23). The statement is also supported by Deepika and Madhuri, who also observe that LDPE degradation generates carbonyl and carboxylic groups on the LDPE surface (24).

FTIR spectra for PMC B before and after water absorption test.

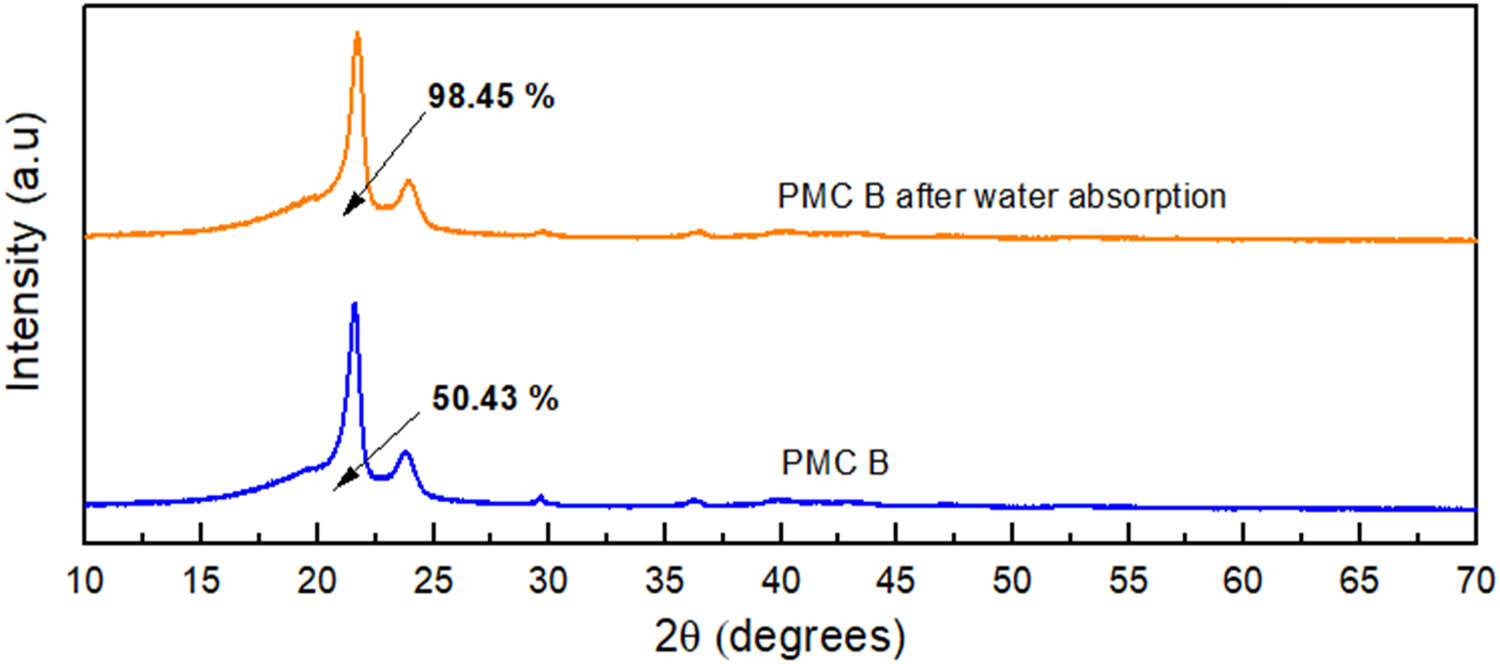

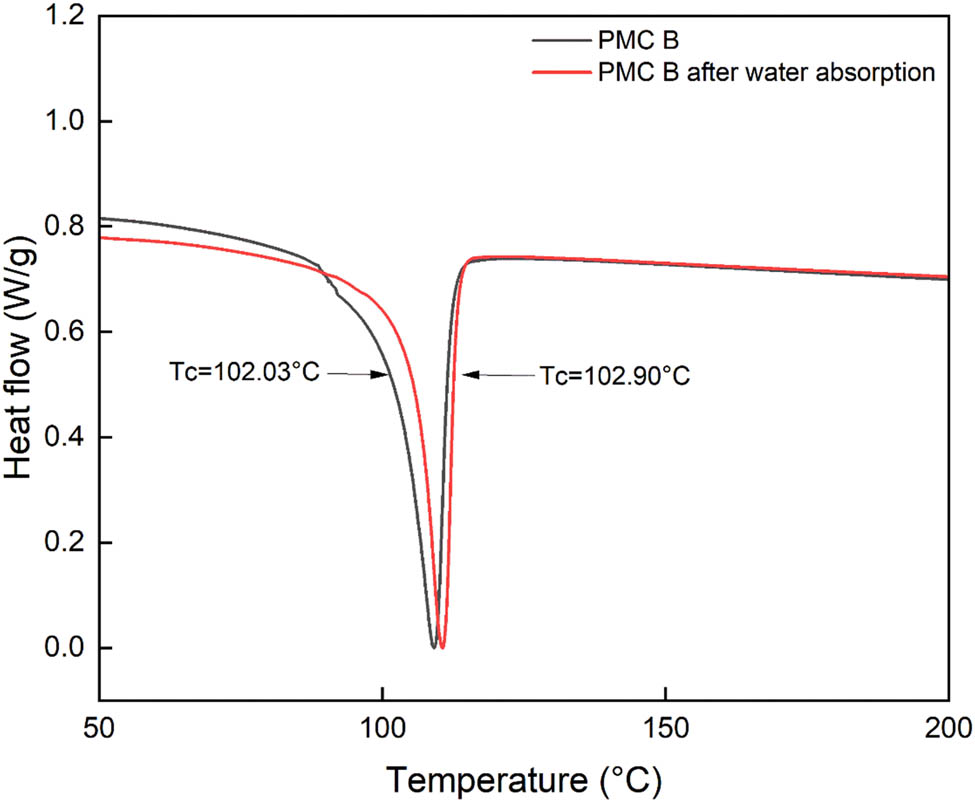

Meanwhile, the XRD displayed in Figure 10 comprehends that the degree of crystallization increased tremendously from 50.43% to 98.45% after 2 weeks of water absorption test for PMC B. The surrounding thermodynamic has crucial role in altering the composites’ crystallization behavior. During the absorption test, the interaction with water molecules at lower temperatures for PMC B will allow further recrystallization process at the PMC B mobile phase (20). The buildup pressure from the recrystallization site will remove the water molecules. In their article, Saretia and coworkers stated that the recrystallization process in water will progress until reaching its thermodynamically equilibrium depending on temperatures for ε‐caprolactone thin film (25). Similar to the system, this phenomenon may have affected the crystal thickness, increasing its lateral growth rate synchronously increase its degree of crystallization for PMC B (26). The claim is supported by the DSC results displayed in Figure 11, where the crystallization temperature (T c) of PMC B shifts to a higher temperature from 102.03°C to 102.90°C after the water absorption test. The increase in PMC B degree of crystallization also expresses the close packing arrangement for the polymer chains, thus providing higher tensile strength with smooth deformation failure compared to control PMC control (27,28).

XRD for 4 phr PM in PMC B before and after water absorption.

DSC for 4 phr PM in PMC B before and after water absorption.

4 Conclusions

In short, the PM with rCB using different amounts of processing aid A and processing aid B was successfully dispersed in an rLDPE matrix via the injection molding process. PMC B’s superior mechanical properties is contributed by the added amount and compatibility of processing aid B as a compatibilizer in establishing a proper matrix filler interaction between them. The addition of 4 phr PM to all PMC demonstrated the highest tensile strength and modulus of elasticity because of the reinforcing effect originating from rCB, calcium carbonate, and the unknown impurities available in the tested samples. Interestingly, after the water absorption process, the mechanical properties of all samples were enhanced. This can be explained by the recrystallization process of rLDPE during the immersion period, causing a close packing arrangement that results in better mechanical properties for the PMC. Considering that the addition of a small amount of rCB and processing aids has successfully worked as a colorant and significantly altered the mechanical properties of PMC, further work will be carried out to seek the effect of filler loading and processing temperature on the crystallization behavior of all PMC in the future (Table 2).

Formulation for PMC

| *phr | PMC control | PMC A | PMC B | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rLDPE | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| PM | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

*phr represents part per hundred resin.

-

Funding information: The author would like to acknowledge the support from the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) under a grant number of FRGS/1/2018/TK05/UNIMAP/02/13 from the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia.

-

Author contributions: Muhamad Al-Haqqem Abdul Hadi: writing – original draft; Nor Azura Abdul Rahim: writing – review and editing the content, writing – formatting; Pei Leng Teh, Kang Wei Chew, and Chun Hong Voon: data verification and checking the overall manuscript; Wee Chun Wong: writing – review and checking the content.

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

FTIR results for PM control, PM A, and PM B.

XRD results for PM control, PM A, and PM B.

References

(1) Chen L, Hou J, Chen Y, Wang H, Duan Y, Zhang J. Synergistic effect of conductive carbon black and silica particles for improving the pyroresistive properties of high density polyethylene composites. Compos B Eng. 2019;178:107465. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107465.Search in Google Scholar

(2) Ramarad S, Ratnam CT, Munusamy Y, Rahim NAA, Muniyadi M. Thermochemical compatibilization of reclaimed tire rubber/poly (ethylene-co-vinyl acetate) blend using electron beam irradiation and amine-based chemical. J Polym Res. 2021;28(10):1–19. 10.1007/s10965-021-02748-y.Search in Google Scholar

(3) Nizamuddin S, Jamal M, Gravina R, Giustozzi F. Recycled plastic as bitumen modifier: The role of recycled linear low-density polyethylene in the modification of physical, chemical and rheological properties of bitumen. J Clean Prod. 2020;266:121988. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121988.Search in Google Scholar

(4) Rahim NAA, Xian LY, Munusamy Y, Zakaria Z, Ramarad S. Melt behavior of polypropylene-co-ethylene composites filled with dual component of sago and kenaf natural filler. J Appl Polym Sci. 2022;139(6):51621. 10.1002/app.51621.Search in Google Scholar

(5) Silva LN, Dos Anjos EGR, Morgado GFD, Marini J, Backes EH, Montagna LS, et al. Development of antistatic packaging of polyamide 6/linear low-density polyethylene blends-based carbon black composites. Polym Bull. 2020;77(7):3389–409. 10.1007/s00289-019-02928-3.Search in Google Scholar

(6) Abdul Rahim NA, Ariff ZM, Abd Jalil J, Ariffin A. Flow characteristics of degraded polypropylene-co-ethylene kaolin composite extruded at different temperatures and extrusion cycles using single-screw extruder. Iran Polym J. 2021;30(11):1201–10. 10.1007/s13726-021-00969-y.Search in Google Scholar

(7) Martínez JD, Cardona-Uribe N, Murillo R, García T, López JM. Carbon black recovery from waste tire pyrolysis by demineralization: Production and application in rubber compounding. Waste Manage. 2019;85:574–84. 10.1016/j.wasman.2019.01.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(8) Lu X, Kang B, Shi S. Selective localization of carbon black in bio-based poly (lactic acid)/recycled high-density polyethylene co-continuous blends to design electrical conductive composites with a low percolation threshold. Polymers. 2019;11(10):1583. 10.3390/polym11101583.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(9) Verma A, Baurai K, Sanjay MR, Siengchin S. Mechanical, microstructural, and thermal characterization insights of pyrolyzed carbon black from waste tires reinforced epoxy nanocomposites for coating application. Polym Compos. 2020;41(1):338–49. 10.1002/pc.25373.Search in Google Scholar

(10) Touris A, Turcios A, Mintz E, Pulugurtha SR, Thor P, Jolly M, et al. Effect of molecular weight and hydration on the tensile properties of polyamide 12. Results Mater. 2020;8:100149. 10.1016/j.rinma.2020.100149.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Velzen EUT, Chu EU, Alvarado CF, Brouwer MT, Molenveld K. The impact of impurities on the mechanical properties of recycled polyethylene. Packag Technol Sci. 2021;34(4):219–28. 10.1002/pts.2551.Search in Google Scholar

(12) Mosoabisane MF, Luyt AS, van Sittert CG. Comparative experimental and modelling study of the thermal and thermo-mechanical properties of LLDPE/wax blends. J Polym Res. 2022;29(7):296. 10.1007/s10965-022-03136-w.Search in Google Scholar

(13) Vigueras-Santiago E, Hernández-López S, Brostow W, Olea-Mejia O, Lara-Sanjuan O. Surface and electrical properties of high density polyethylene + carbon black composites near the percolation threshold. e-Polymers. 2010;10(1):100–7. 10.1515/epoly.2010.10.1.1120.Search in Google Scholar

(14) Lohar G, Tambe P, Jogi B. Influence of dual compatibilizer and carbon black on mechanical and thermal properties of PP/ABS blends and their composites. Compos Interfaces. 2020;27(12):1101–36. 10.1080/09276440.2020.1726137.Search in Google Scholar

(15) Sarifuddin N, Ismail H, Ahmad Z. Studies of properties and characteristics of low-density polyethylene/thermoplastic sago starch-reinforced kenaf core fiber composites. J Thermoplast Compos Mater J. 2015;28(4):445–60. 10.1177/0892705713486125.Search in Google Scholar

(16) Rahim NAA, Ariff ZM, Ariffin A, Jikan SS. Study on effect of filler loading on the flow and swelling behaviors of polypropylene-kaolin composites using single-screw extruder. J Appl Polym Sci. 2011;119:73–83. 10.1002/app.32541.Search in Google Scholar

(17) Alshangiti DM. Impact of a nanomixture of carbon black and clay on the mechanical properties of a series of irradiated natural rubber/butyl rubber blend. e-Polymers. 2021;21(1):662–70. 10.1515/epoly-2021-0051.Search in Google Scholar

(18) Molefi JA, Luyt AS, Krupa I. Comparison of LDPE, LLDPE and HDPE as matrices for phase change materials based on a soft Fischer–Tropsch paraffin wax. Thermochim Acta. 2010;500:88–92. 10.1016/j.tca.2010.01.002.Search in Google Scholar

(19) Tham WL, Poh BT, Ishak ZAM, Chow WS. Effect of N, N′-ethylenebis (stearamide) on the water absorption and hydrolytic degradation of poly (lactic acid)/halloysite nanocomposites. J Thermoplast Compos Mater J. 2017;30(3):416–33. 10.1177/0892705715599435.Search in Google Scholar

(20) Sanjeevi S, Shanmugam V, Kumar S, Ganesan V, Sas G, Johnson DJ, et al. Effects of water absorption on the mechanical properties of hybrid natural fibre/phenol formaldehyde composites. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13385. 10.1038/s41598-021-92457-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(21) Nor WZW, Rahim NAA, Osman H, Ibrahim M. Mechanical properties of starch filled polypropylene under exposure of hygrothermal conditions. Malaysian J Anal Sci. 2014;18(2):434–43.Search in Google Scholar

(22) Khanam PN, AlMaadeed MAA. Processing and characterization of polyethylene-based composites. Adv Manuf Polym Compos Sci. 2015;1:63–79. 10.1179/2055035915Y.0000000002.Search in Google Scholar

(23) Ali SS, Qazi IA, Arshad M, Khan Z, Voice TC, Mehmood CT. Photocatalytic degradation of low density polyethylene (LDPE) films using titania nanotubes. Environ Nanotechnol. 2016;5:44–53. 10.1016/j.enmm.2016.01.001.Search in Google Scholar

(24) Deepika N, Madhuri RJ. Reliable and sophisticated techniques to evaluate LDPE degraded compounds by streptomyces werraensis SDJM. Nat Environ Pollut. 2021;20(3):1077–85. 10.46488/NEPT.2021.V20i03.015.Search in Google Scholar

(25) Saretia S, Machatschek R, Bhuvanesh T, Lendlein A. Effect of Water on Crystallization and Melting of Telechelic Oligo(ε‐caprolactone)s in Ultrathin Films. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2021;8(7):2001940. 10.1002/admi.202001940.Search in Google Scholar

(26) Saw LT, Uy Lan DN, Rahim NAA, Kahar AWM, Viet CX. Processing degradation of polypropylene-ethylene copolymer-kaolin composites by a twin-screw extruder. Polym Degrad Stab. 2015;111:32–7. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.10.024.Search in Google Scholar

(27) Almond J, Sugumaar P, Wenzel MN, Hill G, Wallis C. Determination of the carbonyl index of polyethylene and polypropylene using specified area under band methodology with ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. e-Polymers. 2020;20(1):369–81. 10.1515/epoly-2020-0041.Search in Google Scholar

(28) Mazur K, Jakubowska P, Romańska P, Kuciel S. Green high density polyethylene (HDPE) reinforced with basalt fiber and agricultural fillers for technical applications. Compos B Eng. 2020;202:108399. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108399.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites