Abstract

Blast furnace heat is the key to the blast furnace’s high efficiency and stable operation, and it is difficult to maintain a suitable temperature for large blast furnace operations. When designing the furnace heat prediction and control model, parameters with good reliability and measurability should be chosen to avoid using less accurate parameters and to ensure the accuracy and practicability of the model. This paper presents an effective model for large blast furnace temperature prediction and control. Using thermal equilibrium and the carbon-oxygen balance of the blast furnace’s high-temperature zone, the slag-iron heat index was calculated. Using the relation between the molten iron temperature and slag-iron heat index, the furnace heat parameter can be calculated while production conditions are changed,which can guide furnace heat control.

1 Introduction

Maintaining reasonable heat is the key to the blast furnace’s high efficiency and stable operation. It is difficult to maintain suitable temperature for a large blast furnace, and temperatures that are too high or too low will not only cause blast furnace condition fluctuation, but also the production and technical indicators of the blast furnace and molten iron quality will be adversely affected. Because to the blast furnace production process is a complex reaction process involving high temperatures, external the factors that influence furnace temperature, and long time lag for large blast furnace heat change, furnace temperature control is difficult [1, 2, 3, 4].

With the improvement in equipment and technology in the large blast furnace, the accuracy of certain blast furnace process parameters has clearly improved. For example, the air leaking rate of most small blast furnaces before was more than 8%, but in the modern large blast furnace, it is usually less than 2%. Meanwhile, the required accuracy for furnace temperature control is also improved. When designing the furnace heat prediction and control model, good parameters should be chosen for reliability and to avoid using less accurate parameters to ensure the accuracy and practicality of the model. In order to satisfy the temperature requirements, the operators of blast furnaces should predict the furnace temperature correctly according to the operation parameters and accurate adjustment measures. This paper presents an effective method for large blast furnace temperature prediction and control, which can guide furnace heat adjustment.

There are many factors that influence blast furnace heat. The main factors are blast parameters (including blast volume, rich oxygen flow, PCI rate, blast humidity, and blast temperature), coke load, gas utilization, operation yield, quality of raw materials and fuel (including: coke, coal, sintering, and pellet), heat load, and furnace dust. The furnace heat parameters should be calculated when the above mentioned conditions are changed.

The calculation model presented in this paper are as follows. Firstly, recent data on blast furnace operation were collected, as the benchmark data for blast furnace operation. Secondly, the blast furnace benchmark data were used in the blast furnace high temperature thermal equilibrium and carbon-oxygen balance equations, the theoretical PCI rate was calculated, the theoretical direct reduction of carbon consumption under the benchmark conditions and slag-iron heat index was calculated. Thirdly, the blast furnace target parameters was used in the thermal equilibrium and carbon-oxygen balance equations for the blast furnace high-temperature zone, target slag-iron heat index was calculated, the relation between the temperature and slag-iron heat index was established, and the molten iron temperature and [Si] were calculated; Finally, corresponding to the target molten iron temperature, the slag-iron heat index was used in the blast furnace high temperature thermal equilibrium and carbon-oxygen balance equations, and the PCI rate and the quantity of coal needed were calculated, such that heat control could be achieved.

2 Calculation of the theoretical PCI rate

First, the benchmark parameters should be statistics that can represent the recent operating status of the blast furnace (the "0" on the right is marked as the benchmark parameter), and the statistical parameters are shown in Table 1.

Benchmark parameters of blast furnace.

| Item | Symbol | Units | Benchmark parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blast volume | Vb | Nm3/min | 6096.00 |

| Rich oxygen flow | Vo2 | Nm3/h | 15929.00 |

| Atmospheric humidity | HATS | g/m3 | 3.00 |

| Humidification quantity | HADD | t/h | 0.10 |

| Blast temperature | BT | ∘C | 1267.00 |

| Gas utilization ratio | ηCO | - | 49.51% |

| Molten iron temperature | PT | ∘C | 1515.00 |

| Coke rate | K | kg/tFe | 326.56 |

| PCI rate(dry) | M | kg/tFe | 190.60 |

| Yield of iron | P | t/d | 9458.72 |

| Heat load | Qload | 10MJ/h | 8453.00 |

| Carbon in coke | ω(Ccoke) | % | 87.29 |

| Ash in coke | ω(Acoke) | % | 11.67 |

| Carbon in coal | ω(Ccoal) | % | 69.97 |

| Ash in coal | ω(Acoal) | % | 10.86 |

| Consumption of sintering per ton iron | Msint | kg/tFe | 1213.30 |

| Consumption of pellets per ton iron | Mpell | kg/tFe | 391.11 |

| [Si] | [Si] | % | 0.42 |

| [Fe] | [Fe] | % | 94.72 |

| [C] | [C] | % | 4.70 |

| [Mn] | [Mn] | % | 0.04 |

| [P] | [P] | % | 0.07 |

| [Ti] | [Ti] | % | 0.03 |

| Slag rate | Mslag | kg/tFe | 305.00 |

| Moisture in coal | ω(H2Ocoal) | % | 1.32 |

| O in coal | ω(Ocoal) | % | 8.21 |

| Fe2O3 in Sintering | ω(Fe2O3sint) | % | 72.44 |

| FeO in Sintering | ω(FeOsint) | % | 9.59 |

| Fe2O3 in pellets | ω(Fe2O3pell) | % | 90.88 |

| FeO in pellets | ω(FeOpell) | % | 0.66 |

| FeO in Slag | (FeO) | % | 0.04 |

| S in Slag | (S) | % | 1.02 |

| Furnace dust production per ton iron | Mdust | kg/tFe | 17.00 |

| Fe2O3 in dust | ω(Fe2O3dust) | % | 48.12 |

| FeO in dust | ω(FeOdust) | % | 6.82 |

| C in dust | ω(Cdust) | % | 20.25 |

| O in coke | ω(Ocoal) | % | 0.70 |

| Blast volume by PC | Vcoal | Nm3/min | 2873.00 |

| Nitrogen volume by PC | Vcoal_N2 | Nm3/h | 4000.00 |

| Hydrogen utilization | ηH2 | - | 40.00% |

Atmospheric humidity (%):

Amount of O2 per minute (Nm3/min):

where, λO2 is the quality percentage of O2 in rich oxygen, which is 99.7%.

Oxygen consumption in combustion per ton iron (Nm3/tFe):

Carbon consumption in combustion per ton iron (kg/tFe):

Under normal circumstances, the ratio of unburned coal powder to furnace dust is lower, and the influence on calculation of the thermal equilibrium and carbon-oxygen balance is not larger, but as the PCI rate increases, unburned coal powder into the furnace dust markedly increases, M0 should be the quantity of coal that actually reacts in the furnace, which is the total quantity of coal minus the quantity of coal increased in the furnace dust. Assuming that the coal is burned completely in the tuyere zone, then carbon consumption of coke in combustion per ton iron (kg/tFe)

Amount of coke gasification per ton iron (kg/tFe):

Carbon consumption by direct reduction per ton iron (kg/tFe):

where

The amount of oxygen entering into the blast furnace gas from raw materials and fuel (kg/tFe) is

Amount of moles H containing in per kg coal (kmol/kg):

Use the above calculation results in the carbon-oxygen balance equation [5]:

The denominator is the total volume of carbon gas in moles, the numerator is the total volume of CO2 gas in moles, and the amount is equal to the total amount of CO2 generated from reaction of CO and O. CO comes from the tuyere combustion and O from raw materials and fuel, minus the mole amount of CO that derived from the direct reduction process of C and FeO, and minus the molar volume of H2O that is derived from the direct reduction of H and O. ηH2 indicates the utilization ratio of hydrogen in the high temperature zone, which is generally 30%-50%.

Transform equation (9) to be

Use M0 in equations (5) and (7),

Comparing the theoretical PCI rate calculated from the above equation with the actual coal, if the deviation is not large, it can be directly used in the next calculation. However, the calculated data need to be checked for mistakes or parameter distortion. Based on this premise, the deviation between theoretical and actual quantity of coal needed (or PCI rate) is adjusted to ensure the accuracy of the calculated results.

3 Calculation of slag-iron heat index [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]

Total volume of hot air coming into the blast furnace per minute (Nm3/min):

The ratio of H2O in hot air:

The ratio of O2 in hot air after the decomposition of H2O:

The ratio of O2 in hot air before the decomposition of H2O:

The ratio of N2 in hot air:

The volume of hot air needed to burn per kilogram carbon (Nm3/kg):

The volume of H2O in hot air to burn per kilogram carbon (Nm3/kg):

The volume of O2 in hot air to burn per kilogram carbon (Nm3/kg):

The volume of N2 in hot air to burn per kilogram carbon (Nm3/kg):

The volume of CO generated by burning per kilogram carbon (Nm3/kg):

The volume of N2 generated by burning per kilogram carbon (Nm3/kg):

The volume of H2 generated by burning per kilogram carbon (Nm3/kg):

The volume of H2O generated by burning per kilogram carbon (Nm3/kg):

Thermal revenue by burning per kilogram carbon in high-temperature zone (kJ/kg (C)):

where,

While burning coke, thermal revenue burning per kilogram carbon (kJ/kg (C)) is

While burning coal, thermal revenue burning per kilogram coal (kJ/kg (C)) is

Thermal consumption of carbon per kilogram directly reduced (kJ/kg (C)) is

Heat loss per ton iron (kJ/tFe):

Using the above calculation results in the thermal equilibrium and carbon-oxygen balance equations to calculate the blast furnace high-temperature zone, the target slag-iron heat index (kJ/tFe) is

The slag-iron heat index indicates the heat of iron and slag per ton of iron, which represent the heat level of the blast furnace. The higher the slag-iron heat index is, the higher the furnace heat is.

4 Furnace heat prediction and control

Using the target parameters (or actual running parameters) in the thermal equilibrium and carbon-oxygen balance equations,

where,

The calculation method of OM, Cda, CCBR, Cdust, n(Hcoal), qC_CBT, qcoal, qdFe is the same as

Qheat = λ heat ×Q0heat,λ heat is heat coefficient, and when λ heat = 1, furnace heat can be considered equivalent to the benchmark furnace heat.

The formula of molten iron temperature prediction:

where, α is the correlation coefficient between molten iron temperature and slag-iron heat index.

Using the above calculation results in equations (31) and (32), only M and CdFe are the two unknowns in the equation [5].

M and CdFe can be obtained from equations (38) and (39), and the result can be use in equations (34) and (35) to calculate CCBT_coke and CCBT.

The estimated daily output of molten iron (t/d):

The quantity of coal needed (t/h):

5 Application of blast furnace heat control

Using the benchmark parameters of Table 1 in the above calculation equation, the calculation results are shown in Table 2.

Heat calculation results of blast furnace.

| Item | Symbol | Units | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric humidity | f | - | 0.37% |

| Ratio of O2 in hot air | O2_HB | Nm3/min | 1562.59 |

| Oxygen consumption in combustion per ton iron | OCBT | Nm3/tFe | 237.89 |

| Carbon consumption in combustion per ton iron | CCBT | kg/tFe | 254.88 |

| Amount of coke gasification per ton iron | CGAS_coke | kg/tFe | 234.60 |

| Amount of oxygen entering blast furnace gas | OM | kg/tFe | 421.52 |

| from raw materials and fuel | |||

| Amount of moles H in per kilogram coal | N(Hcoal) | kmol/kg | 0.018 |

| PCI rate | M | kg/tFe | 184.72 |

| Oxygen consumption in combustion per ton iron | CCBT_coke | kg/tFe | 123.35 |

| Carbon consumption by direct reduction per ton iron | CdFe | kg/tFe | 105.65 |

| Total volume of hot air coming into the blast furnace per minute | VHB | Nm3/min | 6748.11 |

| Ratio of H2O in hot air | φ(H2O) | - | 0.39% |

| Ratio of O2 in hot air after the decomposition of H2O | φ1(O2) | - | 24.12% |

| Ratio of O2 in hot air after the decomposition of H2O | φ2(O2) | - | 23.93% |

| Ratio of N2 in hot air | φ(N2) | - | 75.69% |

| Volume of hot air needed to burn per kilogram carbon | NHB | Nm3/kg | 3.87 |

| Volume of H2O in hot air to burn per kilogram carbon | νH2O_HB | Nm3/kg | 0.015 |

| Volume of O2 in hot air to burn per kilogram carbon | νO2_HB | Nm3/kg | 0.93 |

| Volume of N2 in hot air to burn per kilogram carbon | νN2_HB | Nm3/kg | 2.93 |

| Volume of CO generated by burning per kilogram carbon | νCO_GAS | Nm3/kg | 1.87 |

| Volume of N2 generated by burning per kilogram carbon | νN2_GAS | Nm3/kg | 2.93 |

| Volume of H2 generated by burning per kilogram carbon | νH2_GAS | Nm3/kg | 0.009 |

| Volume of H2O generated by burning per kilogram carbon | νH2O_GAS | Nm3/kg | 0.006 |

| Thermal revenue by burning per kilogram carbon in high-temperature zone | qC_CBT | kJ/kg(C) | 10308.33 |

| Thermal revenue by burning per kilogram carbon while burning coke | qC_CBT_coke | kJ/kg(C) | 10223.32 |

| Thermal revenue by burning per kilogram coal while burning coal | qcoal | kJ/kg | 6561.37 |

| Thermal consumption of per kilogram carbon directly reduced | qdFe | kJ/kg(C) | 12746.92 |

| Heat loss per ton iron | Qloss | kJ/tFe | 214481.47 |

| Slag-iron heat index | Qheat | kJ/tFe | 720564 |

According to the calculations in the above section, while the operation parameters of the blast furnace are changed to maintain constant furnace heat, the quantity of the coal needed or other control parameters can be calculated.

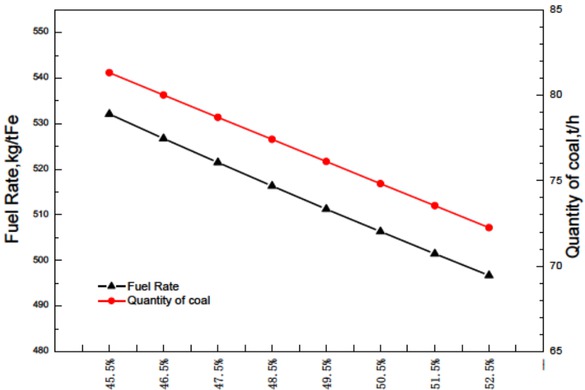

In actual production, to stabilize the furnace conditions and heat, the operating parameters are often kept constant, but ηCO changes frequently. Through the above section, the estimated fuel rate and quantity of coal needed can be calculated for different ηCO, and the calculation results as shown in Figure 1.

Estimated fuel rate and quantity of coal needed on different ηCO

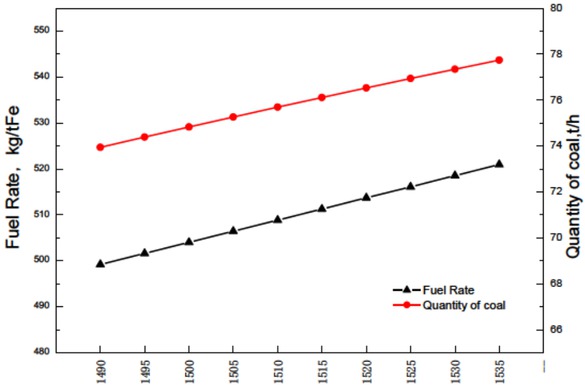

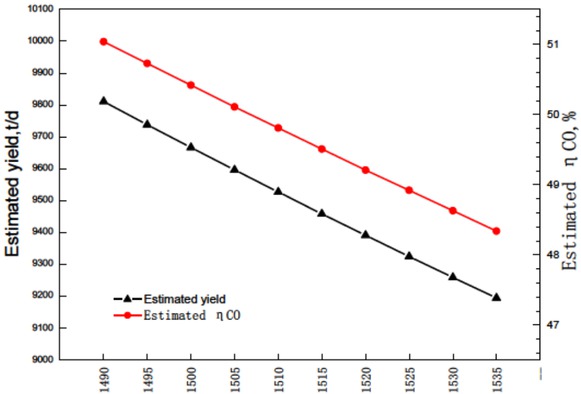

When the heat of blast furnace needs to be adjusted, assuming that only the quantity of coal is adjusted, other operating parameters remain the same, and at the same time direct reduction of heat consumption is constant. Therefore, simultaneous equations (37), (38) and (39), with such parameters as estimated fuel rate, quantity of coal needed, estimated yield and ηCO can be obtained for different temperatures, and the calculation results are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Amount of coal needed when the operating parameters of the blast furnace are changed.

| Item | Units | Operating parameters changed | Amount of coal needed (t/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blast volume | Nm3/min | +100 | +1.03 |

| Rich oxygen flow | Nm3/h | +1000 | +0.82 |

| Atmospheric humidity | g/m3 | +10 | +0.50 |

| Humidification quantity | t/h | +1 | +0.35 |

| Coke rate | kg/tFe | +10 | −4.27 |

Estimated fuel rate and quantity of coal needed at different temperature.

Estimated yield and ηCO at different temperature.

The furnace heat prediction model can be used to calculate the temperature of molten iron while the operation parameters of blast volume, ηCO, and operation yield change simultaneously. The slag-iron heat index, which is 693976 kJ/tFe, can be calculated for the following conditions: blast volume is 6196 Nm3/min, rich oxygen flow is 16929 Nm3/min, atmospheric humidity is 13.00 g/m3, humidification quantity is 1.10 t/h, ηCO is 50.51%, coke rate is 336.56 kg/tFe, operation yield is 9558.72 t/d, and estimated molten iron temperature is 1507∘C.

By adopting the furnace heat prediction and control model, the qualified rate of hot metal temperature in a TISCO large blast furnace (T = 1495~1515∘C) increased from 60.5% to 76.7%, and the qualified rate of [Si] in hot metal (the ratio of [Si] in hot metal < 0.55%) increased from 62.9% to 68.7%, which were good results.

6 Summary

When designing the furnace heat prediction and control model, parameters with good reliability to should be chosen, to avoid using less accurate parameters and to ensure the accuracy and practicality of the model. This paper presents an effective method for blast furnace temperature prediction and control.

The primary factors that influence blast furnace heat include blast parameters, coke load, gas utilization ratio, operation yield, quality of raw materials and fuel, heat load, and furnace dust. Using the furnace heat control model proposed in this paper, furnace heat parameters can be calculated when the above mentioned conditions are changed.

By using the thermal equilibrium and carbon-oxygen balance equation for the blast furnace high-temperature zone, the slag-iron heat index which represent the heat level of the blast furnace can be calculated.

Using the relation between the molten iron temperature and slag-iron heat index, the furnace heat parameters can be calculated when production conditions are changed, which can guide furnace heat control.

References

[1] M.S. Chu, Modelling on Blast Furnace Process and Innovative Technologies, Northeast University Press, Shenyang, 2006.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] J.C. Song, Blast Furnace Iron of Theory and Operation, Metallurgical Industry Press, Beijing, 2005 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[3] X.G. Bi, Mathematical Model and Computer Control of Blast Furnace Process, Metallurgical Industry Press, Beijing, 1996 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[4] X.G. Liu, F. Liu, Blast Furnace Ironmaking Process Optimization and Intelligent Control System, Metallurgical Industry Press, Beijing, 2003 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[5] S.R. Na, Analysis of Ironmaking Calculation, Metallurgical Industry Press, Beijing, 2010, 297-321 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[6] S.R. Na, Ironmaking Calculation, Metallurgical Industry Press, Beijing, 2005, 258-275 (in Chinese).Suche in Google Scholar

[7] L. Wei, S.S. Yang, F. Zhang, Q. Bai, Mathematical Model for Predicting Silicon content and Hot Metal Temperature of Blast Furnace Molten Iron by Means of Furnace Heat Index, Metallurgical Research Center, Beijing, 2005.Suche in Google Scholar

[8] C.X. Cao, G.Y. Zhang, Prediction System of Silicon Content in Blast Furnace Molten Iron Based on Furnace Heat Index and BP Network, Chongqing University, Chongqing, 2008.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Y.Q. Huang, Prediction System of Blast Furnace Thermal State Based on Furnace Heat Index and RBF, Chongqing University, Chongqing, 2007.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] S. P. Mehrotta, C. Nand, ISIJ Int. 33(1993) 839-844.10.2355/isijinternational.33.839Suche in Google Scholar

© 2019 Zhuang-nian Li et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Research on the Influence of Furnace Structure on Copper Cooling Stave Life

- Influence of High Temperature Oxidation on Hydrogen Absorption and Degradation of Zircaloy-2 and Zr 700 Alloys

- Correlation between Travel Speed, Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Wear Characteristics of Ni-Based Hardfaced Deposits over 316LN Austenitic Stainless Steel

- Factors Influencing Gas Generation Behaviours of Lump Coal Used in COREX Gasifier

- Experiment Research on Pulverized Coal Combustion in the Tuyere of Oxygen Blast Furnace

- Phosphate Capacities of CaO–FeO–SiO2–Al2O3/Na2O/TiO2 Slags

- Microstructure and Interface Bonding Strength of WC-10Ni/NiCrBSi Composite Coating by Vacuum Brazing

- Refill Friction Stir Spot Welding of Dissimilar 6061/7075 Aluminum Alloy

- Solvothermal Synthesis and Magnetic Properties of Monodisperse Ni0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 Hollow Nanospheres

- On the Capability of Logarithmic-Power Model for Prediction of Hot Deformation Behavior of Alloy 800H at High Strain Rates

- 3D Heat Conductivity Model of Mold Based on Node Temperature Inheritance

- 3D Microstructure and Micromechanical Properties of Minerals in Vanadium-Titanium Sinter

- Effect of Martensite Structure and Carbide Precipitates on Mechanical Properties of Cr-Mo Alloy Steel with Different Cooling Rate

- The Interaction between Erosion Particle and Gas Stream in High Temperature Gas Burner Rig for Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Permittivity Study of a CuCl Residue at 13–450 °C and Elucidation of the Microwave Intensification Mechanism for Its Dechlorination

- Study on Carbothermal Reduction of Titania in Molten Iron

- The Sequence of the Phase Growth during Diffusion in Ti-Based Systems

- Growth Kinetics of CoB–Co2B Layers Using the Powder-Pack Boriding Process Assisted by a Direct Current Field

- High-Temperature Flow Behaviour and Constitutive Equations for a TC17 Titanium Alloy

- Research on Three-Roll Screw Rolling Process for Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy Bar

- Continuous Cooling Transformation of Undeformed and Deformed High Strength Crack-Arrest Steel Plates for Large Container Ships

- Formation Mechanism and Influence Factors of the Sticker between Solidified Shell and Mold in Continuous Casting of Steel

- Casting Defects in Transition Layer of Cu/Al Composite Castings Prepared Using Pouring Aluminum Method and Their Formation Mechanism

- Effect of Current on Segregation and Inclusions Characteristics of Dual Alloy Ingot Processed by Electroslag Remelting

- Investigation of Growth Kinetics of Fe2B Layers on AISI 1518 Steel by the Integral Method

- Microstructural Evolution and Phase Transformation on the X-Y Surface of Inconel 718 Ni-Based Alloys Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting under Different Heat Treatment

- Characterization of Mn-Doped Co3O4 Thin Films Prepared by Sol Gel-Based Dip-Coating Process

- Deposition Characteristics of Multitrack Overlayby Plasma Transferred Arc Welding on SS316Lwith Co-Cr Based Alloy – Influence ofProcess Parameters

- Elastic Moduli and Elastic Constants of Alloy AuCuSi With FCC Structure Under Pressure

- Effect of Cl on Softening and Melting Behaviors of BF Burden

- Effect of MgO Injection on Smelting in a Blast Furnace

- Structural Characteristics and Hydration Kinetics of Oxidized Steel Slag in a CaO-FeO-SiO2-MgO System

- Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Oxidation Roasting of Oxide–Sulphide Zinc Ore with Addition of Manganese Dioxide Using Response Surface Methodology

- Hydraulic Study of Bubble Migration in Liquid Titanium Alloy Melt during Vertical Centrifugal Casting Process

- Investigation on Double Wire Metal Inert Gas Welding of A7N01-T4 Aluminum Alloy in High-Speed Welding

- Oxidation Behaviour of Welded ASTM-SA210 GrA1 Boiler Tube Steels under Cyclic Conditions at 900°C in Air

- Study on the Evolution of Damage Degradation at Different Temperatures and Strain Rates for Ti-6Al-4V Alloy

- Pack-Boriding of Pure Iron with Powder Mixtures Containing ZrB2

- Evolution of Interfacial Features of MnO-SiO2 Type Inclusions/Steel Matrix during Isothermal Heating at Low Temperatures

- Effect of MgO/Al2O3 Ratio on Viscosity of Blast Furnace Primary Slag

- The Microstructure and Property of the Heat Affected zone in C-Mn Steel Treated by Rare Earth

- Microwave-Assisted Molten-Salt Facile Synthesis of Chromium Carbide (Cr3C2) Coatings on the Diamond Particles

- Effects of B on the Hot Ductility of Fe-36Ni Invar Alloy

- Impurity Distribution after Solidification of Hypereutectic Al-Si Melts and Eutectic Al-Si Melt

- Induced Electro-Deposition of High Melting-Point Phases on MgO–C Refractory in CaO–Al2O3–SiO2 – (MgO) Slag at 1773 K

- Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of 14Cr-ODS Steels with Zr Addition

- A Review of Boron-Rich Silicon Borides Basedon Thermodynamic Stability and Transport Properties of High-Temperature Thermoelectric Materials

- Siliceous Manganese Ore from Eastern India:A Potential Resource for Ferrosilicon-Manganese Production

- A Strain-Compensated Constitutive Model for Describing the Hot Compressive Deformation Behaviors of an Aged Inconel 718 Superalloy

- Surface Alloys of 0.45 C Carbon Steel Produced by High Current Pulsed Electron Beam

- Deformation Behavior and Processing Map during Isothermal Hot Compression of 49MnVS3 Non-Quenched and Tempered Steel

- A Constitutive Equation for Predicting Elevated Temperature Flow Behavior of BFe10-1-2 Cupronickel Alloy through Double Multiple Nonlinear Regression

- Oxidation Behavior of Ferritic Steel T22 Exposed to Supercritical Water

- A Multi Scale Strategy for Simulation of Microstructural Evolutions in Friction Stir Welding of Duplex Titanium Alloy

- Partition Behavior of Alloying Elements in Nickel-Based Alloys and Their Activity Interaction Parameters and Infinite Dilution Activity Coefficients

- Influence of Heating on Tensile Physical-Mechanical Properties of Granite

- Comparison of Al-Zn-Mg Alloy P-MIG Welded Joints Filled with Different Wires

- Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Thick Plate Friction Stir Welds for 6082-T6 Aluminum Alloy

- Research Article

- Kinetics of oxide scale growth on a (Ti, Mo)5Si3 based oxidation resistant Mo-Ti-Si alloy at 900-1300∘C

- Calorimetric study on Bi-Cu-Sn alloys

- Mineralogical Phase of Slag and Its Effect on Dephosphorization during Converter Steelmaking Using Slag-Remaining Technology

- Controllability of joint integrity and mechanical properties of friction stir welded 6061-T6 aluminum and AZ31B magnesium alloys based on stationary shoulder

- Cellular Automaton Modeling of Phase Transformation of U-Nb Alloys during Solidification and Consequent Cooling Process

- The effect of MgTiO3Adding on Inclusion Characteristics

- Cutting performance of a functionally graded cemented carbide tool prepared by microwave heating and nitriding sintering

- Creep behaviour and life assessment of a cast nickel – base superalloy MAR – M247

- Failure mechanism and acoustic emission signal characteristics of coatings under the condition of impact indentation

- Reducing Surface Cracks and Improving Cleanliness of H-Beam Blanks in Continuous Casting — Improving continuous casting of H-beam blanks

- Rhodium influence on the microstructure and oxidation behaviour of aluminide coatings deposited on pure nickel and nickel based superalloy

- The effect of Nb content on precipitates, microstructure and texture of grain oriented silicon steel

- Effect of Arc Power on the Wear and High-temperature Oxidation Resistances of Plasma-Sprayed Fe-based Amorphous Coatings

- Short Communication

- Novel Combined Feeding Approach to Produce Quality Al6061 Composites for Heat Sinks

- Research Article

- Micromorphology change and microstructure of Cu-P based amorphous filler during heating process

- Controlling residual stress and distortion of friction stir welding joint by external stationary shoulder

- Research on the ingot shrinkage in the electroslag remelting withdrawal process for 9Cr3Mo roller

- Production of Mo2NiB2 Based Hard Alloys by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis

- The Morphology Analysis of Plasma-Sprayed Cast Iron Splats at Different Substrate Temperatures via Fractal Dimension and Circularity Methods

- A Comparative Study on Johnson–Cook, Modified Johnson–Cook, Modified Zerilli–Armstrong and Arrhenius-Type Constitutive Models to Predict Hot Deformation Behavior of TA2

- Dynamic absorption efficiency of paracetamol powder in microwave drying

- Preparation and Properties of Blast Furnace Slag Glass Ceramics Containing Cr2O3

- Influence of unburned pulverized coal on gasification reaction of coke in blast furnace

- Effect of PWHT Conditions on Toughness and Creep Rupture Strength in Modified 9Cr-1Mo Steel Welds

- Role of B2O3 on structure and shear-thinning property in CaO–SiO2–Na2O-based mold fluxes

- Effect of Acid Slag Treatment on the Inclusions in GCr15 Bearing Steel

- Recovery of Iron and Zinc from Blast Furnace Dust Using Iron-Bath Reduction

- Phase Analysis and Microstructural Investigations of Ce2Zr2O7 for High-Temperature Coatings on Ni-Base Superalloy Substrates

- Combustion Characteristics and Kinetics Study of Pulverized Coal and Semi-Coke

- Mechanical and Electrochemical Characterization of Supersolidus Sintered Austenitic Stainless Steel (316 L)

- Synthesis and characterization of Cu doped chromium oxide (Cr2O3) thin films

- Ladle Nozzle Clogging during casting of Silicon-Steel

- Thermodynamics and Industrial Trial on Increasing the Carbon Content at the BOF Endpoint to Produce Ultra-Low Carbon IF Steel by BOF-RH-CSP Process

- Research Article

- Effect of Boundary Conditions on Residual Stresses and Distortion in 316 Stainless Steel Butt Welded Plate

- Numerical Analysis on Effect of Additional Gas Injection on Characteristics around Raceway in Melter Gasifier

- Variation on thermal damage rate of granite specimen with thermal cycle treatment

- Effects of Fluoride and Sulphate Mineralizers on the Properties of Reconstructed Steel Slag

- Effect of Basicity on Precipitation of Spinel Crystals in a CaO-SiO2-MgO-Cr2O3-FeO System

- Review Article

- Exploitation of Mold Flux for the Ti-bearing Welding Wire Steel ER80-G

- Research Article

- Furnace heat prediction and control model and its application to large blast furnace

- Effects of Different Solid Solution Temperatures on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of the AA7075 Alloy After T6 Heat Treatment

- Study of the Viscosity of a La2O3-SiO2-FeO Slag System

- Tensile Deformation and Work Hardening Behaviour of AISI 431 Martensitic Stainless Steel at Elevated Temperatures

- The Effectiveness of Reinforcement and Processing on Mechanical Properties, Wear Behavior and Damping Response of Aluminum Matrix Composites

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Research on the Influence of Furnace Structure on Copper Cooling Stave Life

- Influence of High Temperature Oxidation on Hydrogen Absorption and Degradation of Zircaloy-2 and Zr 700 Alloys

- Correlation between Travel Speed, Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Wear Characteristics of Ni-Based Hardfaced Deposits over 316LN Austenitic Stainless Steel

- Factors Influencing Gas Generation Behaviours of Lump Coal Used in COREX Gasifier

- Experiment Research on Pulverized Coal Combustion in the Tuyere of Oxygen Blast Furnace

- Phosphate Capacities of CaO–FeO–SiO2–Al2O3/Na2O/TiO2 Slags

- Microstructure and Interface Bonding Strength of WC-10Ni/NiCrBSi Composite Coating by Vacuum Brazing

- Refill Friction Stir Spot Welding of Dissimilar 6061/7075 Aluminum Alloy

- Solvothermal Synthesis and Magnetic Properties of Monodisperse Ni0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 Hollow Nanospheres

- On the Capability of Logarithmic-Power Model for Prediction of Hot Deformation Behavior of Alloy 800H at High Strain Rates

- 3D Heat Conductivity Model of Mold Based on Node Temperature Inheritance

- 3D Microstructure and Micromechanical Properties of Minerals in Vanadium-Titanium Sinter

- Effect of Martensite Structure and Carbide Precipitates on Mechanical Properties of Cr-Mo Alloy Steel with Different Cooling Rate

- The Interaction between Erosion Particle and Gas Stream in High Temperature Gas Burner Rig for Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Permittivity Study of a CuCl Residue at 13–450 °C and Elucidation of the Microwave Intensification Mechanism for Its Dechlorination

- Study on Carbothermal Reduction of Titania in Molten Iron

- The Sequence of the Phase Growth during Diffusion in Ti-Based Systems

- Growth Kinetics of CoB–Co2B Layers Using the Powder-Pack Boriding Process Assisted by a Direct Current Field

- High-Temperature Flow Behaviour and Constitutive Equations for a TC17 Titanium Alloy

- Research on Three-Roll Screw Rolling Process for Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy Bar

- Continuous Cooling Transformation of Undeformed and Deformed High Strength Crack-Arrest Steel Plates for Large Container Ships

- Formation Mechanism and Influence Factors of the Sticker between Solidified Shell and Mold in Continuous Casting of Steel

- Casting Defects in Transition Layer of Cu/Al Composite Castings Prepared Using Pouring Aluminum Method and Their Formation Mechanism

- Effect of Current on Segregation and Inclusions Characteristics of Dual Alloy Ingot Processed by Electroslag Remelting

- Investigation of Growth Kinetics of Fe2B Layers on AISI 1518 Steel by the Integral Method

- Microstructural Evolution and Phase Transformation on the X-Y Surface of Inconel 718 Ni-Based Alloys Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting under Different Heat Treatment

- Characterization of Mn-Doped Co3O4 Thin Films Prepared by Sol Gel-Based Dip-Coating Process

- Deposition Characteristics of Multitrack Overlayby Plasma Transferred Arc Welding on SS316Lwith Co-Cr Based Alloy – Influence ofProcess Parameters

- Elastic Moduli and Elastic Constants of Alloy AuCuSi With FCC Structure Under Pressure

- Effect of Cl on Softening and Melting Behaviors of BF Burden

- Effect of MgO Injection on Smelting in a Blast Furnace

- Structural Characteristics and Hydration Kinetics of Oxidized Steel Slag in a CaO-FeO-SiO2-MgO System

- Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Oxidation Roasting of Oxide–Sulphide Zinc Ore with Addition of Manganese Dioxide Using Response Surface Methodology

- Hydraulic Study of Bubble Migration in Liquid Titanium Alloy Melt during Vertical Centrifugal Casting Process

- Investigation on Double Wire Metal Inert Gas Welding of A7N01-T4 Aluminum Alloy in High-Speed Welding

- Oxidation Behaviour of Welded ASTM-SA210 GrA1 Boiler Tube Steels under Cyclic Conditions at 900°C in Air

- Study on the Evolution of Damage Degradation at Different Temperatures and Strain Rates for Ti-6Al-4V Alloy

- Pack-Boriding of Pure Iron with Powder Mixtures Containing ZrB2

- Evolution of Interfacial Features of MnO-SiO2 Type Inclusions/Steel Matrix during Isothermal Heating at Low Temperatures

- Effect of MgO/Al2O3 Ratio on Viscosity of Blast Furnace Primary Slag

- The Microstructure and Property of the Heat Affected zone in C-Mn Steel Treated by Rare Earth

- Microwave-Assisted Molten-Salt Facile Synthesis of Chromium Carbide (Cr3C2) Coatings on the Diamond Particles

- Effects of B on the Hot Ductility of Fe-36Ni Invar Alloy

- Impurity Distribution after Solidification of Hypereutectic Al-Si Melts and Eutectic Al-Si Melt

- Induced Electro-Deposition of High Melting-Point Phases on MgO–C Refractory in CaO–Al2O3–SiO2 – (MgO) Slag at 1773 K

- Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of 14Cr-ODS Steels with Zr Addition

- A Review of Boron-Rich Silicon Borides Basedon Thermodynamic Stability and Transport Properties of High-Temperature Thermoelectric Materials

- Siliceous Manganese Ore from Eastern India:A Potential Resource for Ferrosilicon-Manganese Production

- A Strain-Compensated Constitutive Model for Describing the Hot Compressive Deformation Behaviors of an Aged Inconel 718 Superalloy

- Surface Alloys of 0.45 C Carbon Steel Produced by High Current Pulsed Electron Beam

- Deformation Behavior and Processing Map during Isothermal Hot Compression of 49MnVS3 Non-Quenched and Tempered Steel

- A Constitutive Equation for Predicting Elevated Temperature Flow Behavior of BFe10-1-2 Cupronickel Alloy through Double Multiple Nonlinear Regression

- Oxidation Behavior of Ferritic Steel T22 Exposed to Supercritical Water

- A Multi Scale Strategy for Simulation of Microstructural Evolutions in Friction Stir Welding of Duplex Titanium Alloy

- Partition Behavior of Alloying Elements in Nickel-Based Alloys and Their Activity Interaction Parameters and Infinite Dilution Activity Coefficients

- Influence of Heating on Tensile Physical-Mechanical Properties of Granite

- Comparison of Al-Zn-Mg Alloy P-MIG Welded Joints Filled with Different Wires

- Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Thick Plate Friction Stir Welds for 6082-T6 Aluminum Alloy

- Research Article

- Kinetics of oxide scale growth on a (Ti, Mo)5Si3 based oxidation resistant Mo-Ti-Si alloy at 900-1300∘C

- Calorimetric study on Bi-Cu-Sn alloys

- Mineralogical Phase of Slag and Its Effect on Dephosphorization during Converter Steelmaking Using Slag-Remaining Technology

- Controllability of joint integrity and mechanical properties of friction stir welded 6061-T6 aluminum and AZ31B magnesium alloys based on stationary shoulder

- Cellular Automaton Modeling of Phase Transformation of U-Nb Alloys during Solidification and Consequent Cooling Process

- The effect of MgTiO3Adding on Inclusion Characteristics

- Cutting performance of a functionally graded cemented carbide tool prepared by microwave heating and nitriding sintering

- Creep behaviour and life assessment of a cast nickel – base superalloy MAR – M247

- Failure mechanism and acoustic emission signal characteristics of coatings under the condition of impact indentation

- Reducing Surface Cracks and Improving Cleanliness of H-Beam Blanks in Continuous Casting — Improving continuous casting of H-beam blanks

- Rhodium influence on the microstructure and oxidation behaviour of aluminide coatings deposited on pure nickel and nickel based superalloy

- The effect of Nb content on precipitates, microstructure and texture of grain oriented silicon steel

- Effect of Arc Power on the Wear and High-temperature Oxidation Resistances of Plasma-Sprayed Fe-based Amorphous Coatings

- Short Communication

- Novel Combined Feeding Approach to Produce Quality Al6061 Composites for Heat Sinks

- Research Article

- Micromorphology change and microstructure of Cu-P based amorphous filler during heating process

- Controlling residual stress and distortion of friction stir welding joint by external stationary shoulder

- Research on the ingot shrinkage in the electroslag remelting withdrawal process for 9Cr3Mo roller

- Production of Mo2NiB2 Based Hard Alloys by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis

- The Morphology Analysis of Plasma-Sprayed Cast Iron Splats at Different Substrate Temperatures via Fractal Dimension and Circularity Methods

- A Comparative Study on Johnson–Cook, Modified Johnson–Cook, Modified Zerilli–Armstrong and Arrhenius-Type Constitutive Models to Predict Hot Deformation Behavior of TA2

- Dynamic absorption efficiency of paracetamol powder in microwave drying

- Preparation and Properties of Blast Furnace Slag Glass Ceramics Containing Cr2O3

- Influence of unburned pulverized coal on gasification reaction of coke in blast furnace

- Effect of PWHT Conditions on Toughness and Creep Rupture Strength in Modified 9Cr-1Mo Steel Welds

- Role of B2O3 on structure and shear-thinning property in CaO–SiO2–Na2O-based mold fluxes

- Effect of Acid Slag Treatment on the Inclusions in GCr15 Bearing Steel

- Recovery of Iron and Zinc from Blast Furnace Dust Using Iron-Bath Reduction

- Phase Analysis and Microstructural Investigations of Ce2Zr2O7 for High-Temperature Coatings on Ni-Base Superalloy Substrates

- Combustion Characteristics and Kinetics Study of Pulverized Coal and Semi-Coke

- Mechanical and Electrochemical Characterization of Supersolidus Sintered Austenitic Stainless Steel (316 L)

- Synthesis and characterization of Cu doped chromium oxide (Cr2O3) thin films

- Ladle Nozzle Clogging during casting of Silicon-Steel

- Thermodynamics and Industrial Trial on Increasing the Carbon Content at the BOF Endpoint to Produce Ultra-Low Carbon IF Steel by BOF-RH-CSP Process

- Research Article

- Effect of Boundary Conditions on Residual Stresses and Distortion in 316 Stainless Steel Butt Welded Plate

- Numerical Analysis on Effect of Additional Gas Injection on Characteristics around Raceway in Melter Gasifier

- Variation on thermal damage rate of granite specimen with thermal cycle treatment

- Effects of Fluoride and Sulphate Mineralizers on the Properties of Reconstructed Steel Slag

- Effect of Basicity on Precipitation of Spinel Crystals in a CaO-SiO2-MgO-Cr2O3-FeO System

- Review Article

- Exploitation of Mold Flux for the Ti-bearing Welding Wire Steel ER80-G

- Research Article

- Furnace heat prediction and control model and its application to large blast furnace

- Effects of Different Solid Solution Temperatures on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of the AA7075 Alloy After T6 Heat Treatment

- Study of the Viscosity of a La2O3-SiO2-FeO Slag System

- Tensile Deformation and Work Hardening Behaviour of AISI 431 Martensitic Stainless Steel at Elevated Temperatures

- The Effectiveness of Reinforcement and Processing on Mechanical Properties, Wear Behavior and Damping Response of Aluminum Matrix Composites