Abstract

In this study, oxide dispersion strengthened (ODS) ferritic steels with nominal composition of Fe–14Cr–2W–0.35Y2O3 (14Cr non Zr-ODS) and Fe–14Cr–2W–0.3Zr–0.35Y2O3 (14Cr–Zr-ODS) were fabricated by mechanical alloying (MA) and hot isostatic pressing (HIP) technique to explore the impact of Zr addition on the microstructure and mechanical properties of 14Cr-ODS steels. Microstructure characterization revealed that Zr addition led to the formation of finer oxides, which was identified as Y4Zr3O12, with denser dispersion in the matrix. The ultimate tensile strength (UTS) of the non Zr-ODS steel is about 1201 MPa, but UTS of the Zr-ODS steel increases to1372 MPa, indicating the enhancement of mechanical properties by Zr addition.

Introduction

In a future environmental friendly energy scenario, the aim of decreasing reliance on fossil fuels has motivated a world-wide interest in advanced nuclear energy [1, 2]. To meet the higher standard of material performance in generation IV fission reactors and future fusion reactors, it is necessary to develop new structural materials with excellent properties including irradiation resistance, corrosion resistance and good high temperature strength [1, 3]. Recently, oxide dispersion strengthened (ODS) ferritic steels have been developed as fuel cladding for next generation nuclear systems. Compared with conventional ferritic/martensitic steels, ODS steels have better tensile and creep strength, radiation resistance and oxidation resistance due to the high number density of nano-sized oxide particles with good thermal stability [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. Cr can improve the corrosion resistance of ODS steels, but the Cr content can be balanced between a merit of corrosion resistance and a demerit of aging embrittlement at high temperature [12]. Therefore, the Cr content in ODS steels was usually controlled to less than 16 wt%. Some research groups have also reported the benefit of Ti addition in refining oxide particles (Y2O3) sizes, and increasing their number densities, through changing their chemical composition [13, 14, 15]. According to the first principle calculation results, the binding energy of Y–Zr–O phase is higher than that of Y–Ti–O phase in Fe matrix, which means that the Y–Zr–O phase is easier to form and more stable than Y–Ti–O phase [16]. Some researchers have found that the addition of element Zr can refine the oxides due to smaller oxide formation energy [17]. For this, some researchers have suggested utilizing of Zr rather than Ti in Al-ODS steel which promoted formation of finer Y–Zr–O particles compared to coarse Y–Al–O particles [18]. So it was expected that the addition of Zr elements in ODS steels without Al addition would refine the oxide particles and increase the number density of oxide particles by forming Y–Zr–O phase instead of Y–O phase, which can improve the high temperature strength with a good corrosion resistance ability. In this research, we report a new alloy system based on conventional ODS steels with Zr addition which were fabricated by mechanical alloying (MA) and hot isostatic pressing (HIP). The grain size, size and phase composition of oxide particles, and mechanical properties of the 14Cr-ODS steels were characterized.

Experimental

The ODS ferritic steel with the nominal composition of Fe–14Cr–2W–0.35Y2O3 (wt%) was prepared by MA, using high-purity metal powders of Fe, Cr, W and Ti in size about 10 μm and Y2O3 particles sized between 30 and 50 nm. In order to investigate effects of Zr addition on the microstructure and mechanical properties of ODS ferritic steels, Zr powders (0.3 wt%) in size of micrometer were used. The MA was performed in a high purity Ar (99.99 wt%) atmosphere by using a planetary ball mill. The ball-to-powder weight ratio of 10:1 and a rotation speed of 260 rpm were conducted with milling time up to 50 h [19]. Subsequently, the milled powders were then sealed into a mild steel can, degassed at 400°C for 4 h in vacuum (<10–4 Pa) and then consolidated by HIP at 1100°C under a pressure of 150 MPa for 2 h. The relative density of specimen was measured by means of the Archimedes method and compared to a calculated, theoretical density of the ferritic steel 7.82 g/cm3. To investigate the effect of Zr addition on the grain size, the Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) specimens from HIPed bars with dimension 3×5×10 mm3 was carried out on a JEOL JSM7001F SEM after electro polishing in step length of 0.1 μm/s. The oxide particles size and composition of the specimens were investigated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a JEM-2010 with an Energy Dispersive Spectroscope (EDS). The TEM samples were prepared by using a replica method. The procedures for the preparation are as follows: mechanically polished 5×10 mm2 of the ODS steels were pre-etched in a dilute acid solution (hydrochloric acid (10%), ethanol (90%)) for 10 min. The chemically etched surfaces were then coated with an amorphous carbon film to a thickness of about 1500 Å with a JEOL 560 fine carbon coater, and subsequently chemical etched again in a similar acid solution to make the separation of carbon films from the substrate of the alloys. The carbon films can be cleaned carefully in an ethanol solution (10% pure ethanol: 90% distillated water), were finally put on copper meshes. Extraction replicas can give us more coherent information about oxide particles analysis without a matrix. The SAXS measurements were performed in transmission mode at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) in BL16B1 beamline to analysis the size and number density distribution of nano-sized oxides in ODS steels. The photon energy and wavelength were 10 KeV and 1.24 Å, respectively. In order to obtain a good transmission rate, the ODS samples were finally mechanically ground to 30 μm in thickness. A two-dimensional imaging detector was used to collect the scattering patterns. After corrections (using a cowhells standard), the two-dimensional diffraction rings were transformed into one-dimensional SAXS intensity (I)~ scattering vector (q) curves. The scattering vector q is defined as: q=4π sin θ/λ, λ is the X-ray wavelength, θ is the scattering angle. After correction (using cowhells as standard specimen), the two-dimensional scattering rings were transformed into one-dimensional scattering curves by using Fit 2D software produced by Andy Hammersley on V 10.132. [20].

In this study, SAXS data were fitted by software package IRENA package [21]. The oxides were assumed to be spherical [22]. The unified equation summarized by Beaucage is an approximate form that describes a complex morphology over a wide range of q in terms of structural levels. The fitting of SAXS data was based on the maximum entropy algorithm [22, 23], so that the size distribution of oxides could be assessed. The unified equation is given below:

Where G is a constant defined by the specifics of composition and concentration of the oxides. For dilute oxides, G=Npnp2, where Np is the number of oxides in the scattering volume and np is the number of excess electrons in an oxide compared to Fe matrix. Thus, G=Np(ρeVp)2, where Vp is the volume of an oxide and ρe is the electron-density difference between the oxide and Fe matrix. Rg is radius of gyration. B is a prefactor specific to the type of power-law scattering and defined according to the regime in which the exponent P falls.

The number density distribution N(r) of oxides with radius r is assumed to have a log normal distribution, which is defined as follows:

Where R0 is the radius at the peak position of number density, and the standard deviation σ is the width of log normal distribution of N(r). The average diameter dave and standard deviation σ in this study were obtained from IRENA package directly.

Vickers microhardness tests were performed by using 401MVDTM Vickers hardness tester at a load of 100 g. The hardness values were determined based on the average of 10 points. Tensile tests were carried out at constant strain rate of 2×10–3 mms−1 at room temperature (RT) and 650°C, respectively with the dimensions of 1 mm thick, 3 mm wide and 13 mm gauge length. Tension tests were performed three times at each temperature.

Result and discussion

Microstructure characterization

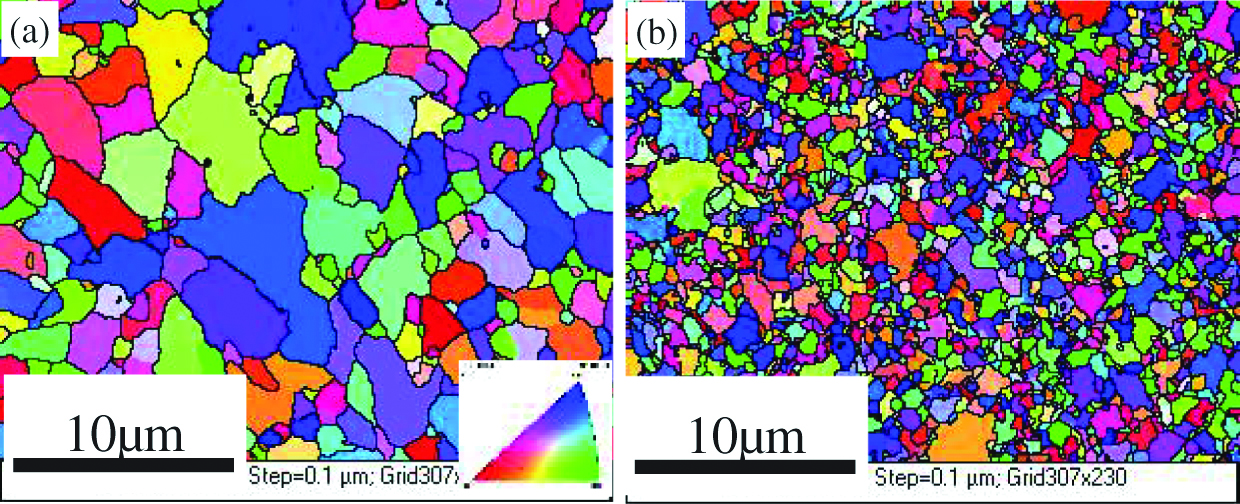

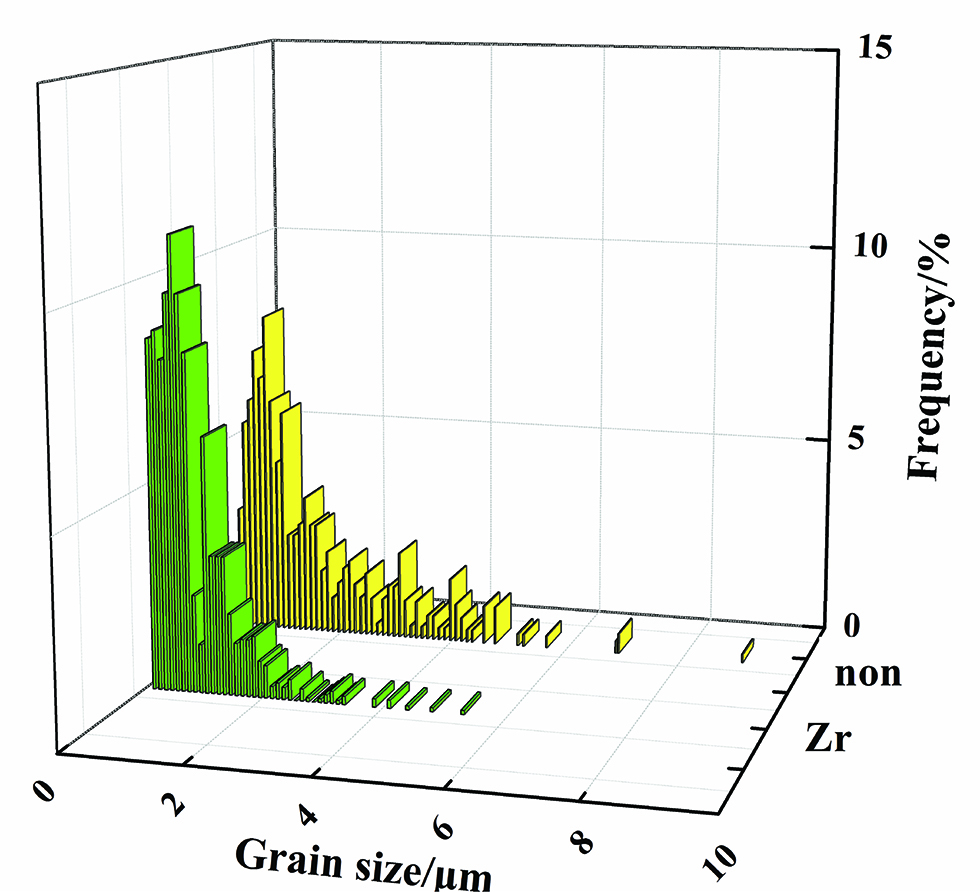

The relative density (the ratio of real density and theoretical density) of the two kinds of 14Cr-ODS ferritic steels produced by MA and HIP is greater than 99%. EBSD method was exploited to evaluate the change of grain size by Zr addition. Results are shown in Figure 1. It can be seen from the inverse pole figure (IPF) maps that no obvious anisotropies were observed in the specimens. The grain size can be refined by Zr addition. The mean grain sizes were around 1.3±0.4 μm and 0.7±0.3 μm, respectively which can be determined from the EBSD images. Based on Hall–Petch relation, the smaller grain size means higher yield strength. The histograms of grain size distribution were presented in Figure 2. It shows that the distribution of the grain size becomes narrower by Zr addition and that the grain size is mainly distributed in the range of 0.2–6.8 μm and 0.1–3.8 μm in non Zr-ODS steel and Zr-ODS steel, respectively. The statistical EBSD results, seen in Figure 2, indicate that Zr addition has significant effect on the grain size and distribution.

Inversed pole figures (IPF) maps of 14Cr-ODS steels (a) non Zr-ODS steel (b) Zr-ODS steel.

Grain size distribution of the ODS steels by EBSD analysis.

After a long time milling, the alloy elements go on a complete dissolution at the atomic scale and matrix which form a supersaturated solid solution within the matrix and the grains of powders are refined and high-density defects and dislocations are produced due to severe and repeated plastic deformation, resulting in high stored energy [19, 24]. Nano-scale grains in MA powders grow or recrystallize during HIP due to high temperature. However, the formation of high density of rich nano-oxides can impede the growth of grains during HIP. Some researchers also reported that Fe–Zr and Fe–Ni–Zr alloys which were produced by MA are resistant to grain growth due to the the amount of Zr available for segregation in a large grain-boundary area [25, 26]. According to the first principle calculation results, the Y–Zr–O phase is easier to form and more stable [16]. The grains may grow very slowly due to Zr addition.

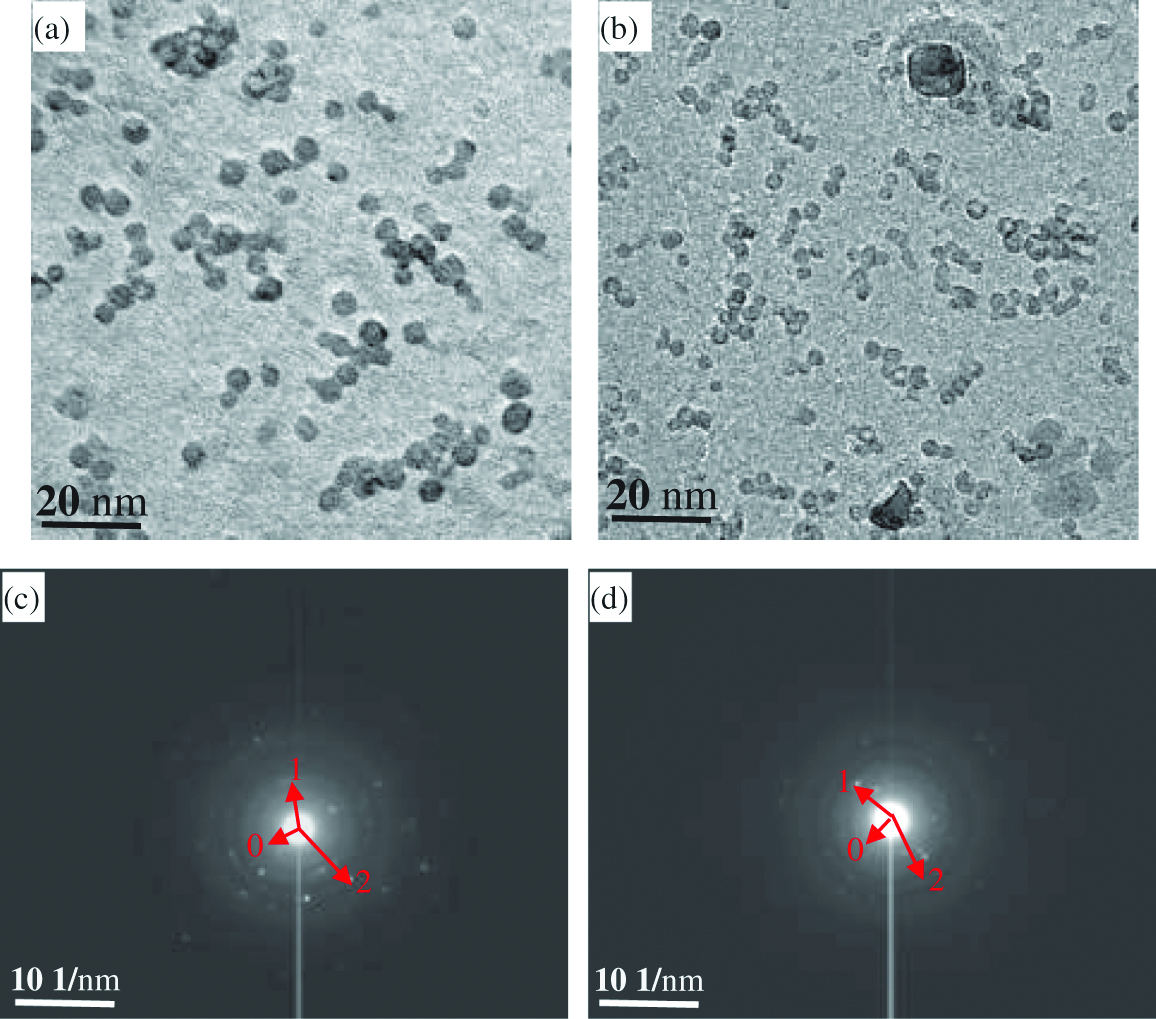

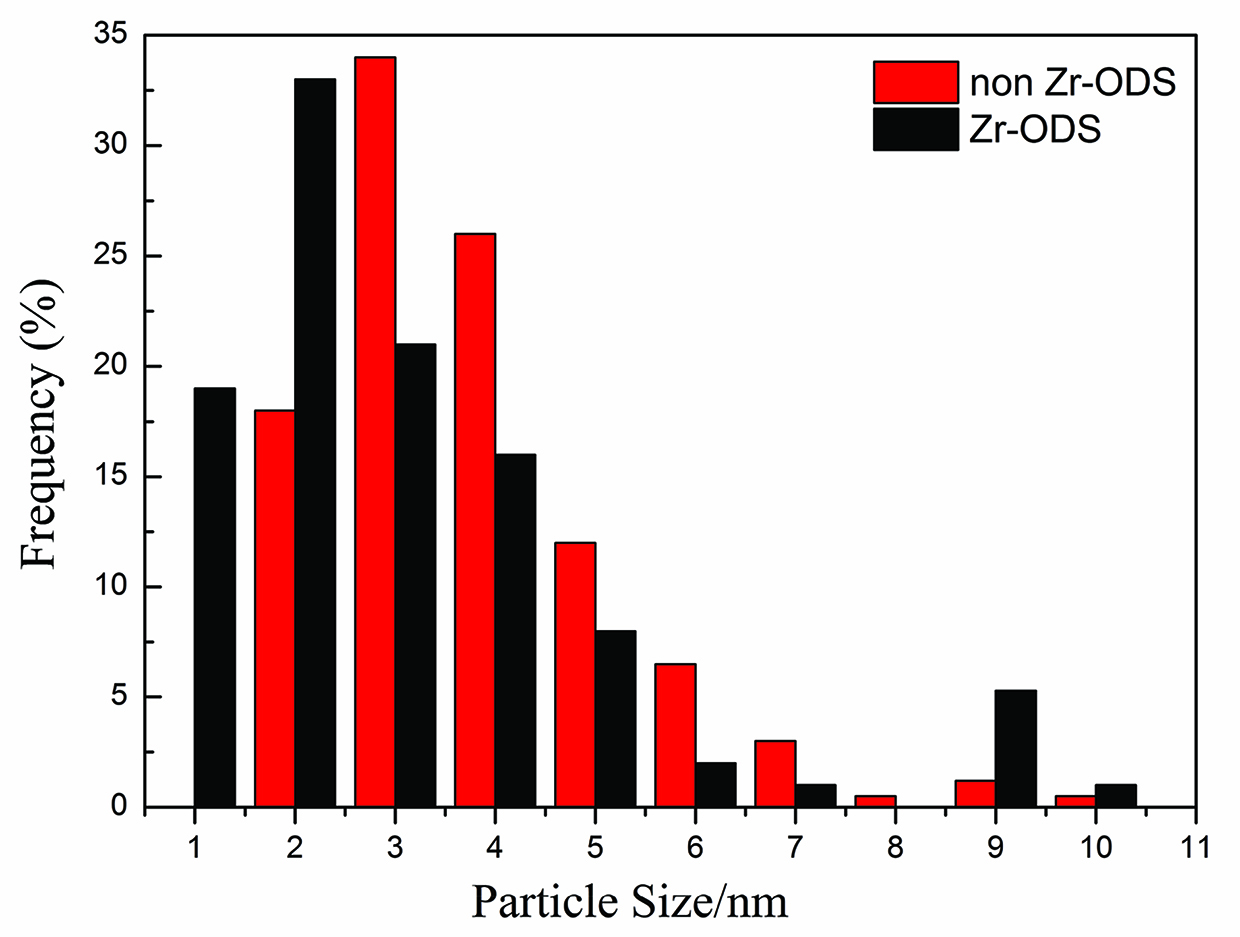

Typical morphologies of oxides in the specimens of the two kinds of ODS steels are shown in Figure 3(a) and 3(b). The image taken from carbon replica specimens indicated that oxides with a size less than 10 nm were relatively uniformly distributed. Significant difference in the size distribution of oxides in the two kinds of specimens was found. The mean particle sizes were measured to be 5.4±1.9 and 3.3±1.1 nm as estimated by counting more than 1000 particles in the TEM images taken in different regions of the specimens in the non Zr-ODS steel and the Zr-ODS steels, respectively, as given in Figure 4(a) and 4(b). It is found that selected-area diffraction (SAD) patterns from oxides fit the cubic structure Y2O3 compounds in non Zr-ODS steel. In Zr-ODS steel, the nano-sized oxides are trigonal δ-phase Y4Zr3O12 compounds. The Y4Zr3O12 oxide has a space group: R-3(148) with a=b=0.9723 nm and c=0.909 nm, a=b=90°, c=120° [27]. The investigation of individual oxides with SAD patterns usually tend to make use of relatively big particles, the results are not a good statistics especially for nano-sized oxides. Therefore the polycrystalline rings from SAD over a large number of nano-sized oxides for non Zr-ODS steel and Zr-ODS steel in a region of the carbon replica specimens were used, as shown in Figure 4(c) and 4(d). The radius of the relatively intensive rings (obtained under an acceleration voltage of 200 kV and a camera length of 80 cm) and matches are given in Tables 1 and 2. It can be seen that the intensive rings of the SAD pattern can be readily ascribed to some like (2 2 0), (4 0 0) and (4 4 4) for non-Zr ODS steel. Another rings of the SAD pattern for Zr-ODS steel are (0 2 1), (2 1–2) and (3 1–1).

Typical morphology of oxides retrieved in a carbon replica from the ODS steels (a) non Zr-ODS steel (b) Zr-ODS steel.

Size distributions of the oxides retrieved in a carbon replica from the ODS steels.

Radius of rings from SAD pattern and possible matches for non Zr-ODS steel.

| Ring No. | Radius (nm) | Match Crystal: index of reflections |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.375 | Y2O3 cubic (2 2 0) |

| 1 | 0.265 | Y2O3 cubic (4 0 0) |

| 2 | 0.153 | Y2O3 cubic (4 4 4) |

Radius of rings from SAD pattern and possible matches for Zr-ODS steel [27].

| Ring No. | Radius (nm) | Match Crystal: index of reflections |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.382 | Y4Zr3O12 Rhomb centered (0 2 1) |

| 1 | 0.261 | Y4Zr3O12 Rhomb centered (2 1–2) |

| 2 | 0.226 | Y4Zr3O12 Rhomb centered (3 1–1) |

More details about the chemical composition of the oxides can still be obtained using the carbon replica method, which supplies an enhanced image contrast and reduced background absorption. According to the EDS analyses in Figure 5(a) and 5(b), the chemical compositions of these oxides were analyzed to be Y- and O-enriched particles, and Y-, Zr- and O-enriched particles in the non-Zr and the Zr-ODS steels, respectively. These results are in good agreement with the SAD results in Figure 4(c) and 4(d). During HIP, Y–O rich oxides and Y–Zr–O particles start nucleation and then grow through Ostwald ripening mechanism. Y–O rich oxides grow more quickly than Y–Zr–O particles. This result is in good agreement with the first principle calculation results that the Y–Zr–O phase is easier to form and more stable due to the strong interaction of Zr with vacancy and attractive interaction between Y and Zr [16].

EDS spectrum of the oxides retrieved in a carbon replica from the ODS steels (a) non Zr-ODS steel (b) Zr-ODS steel.

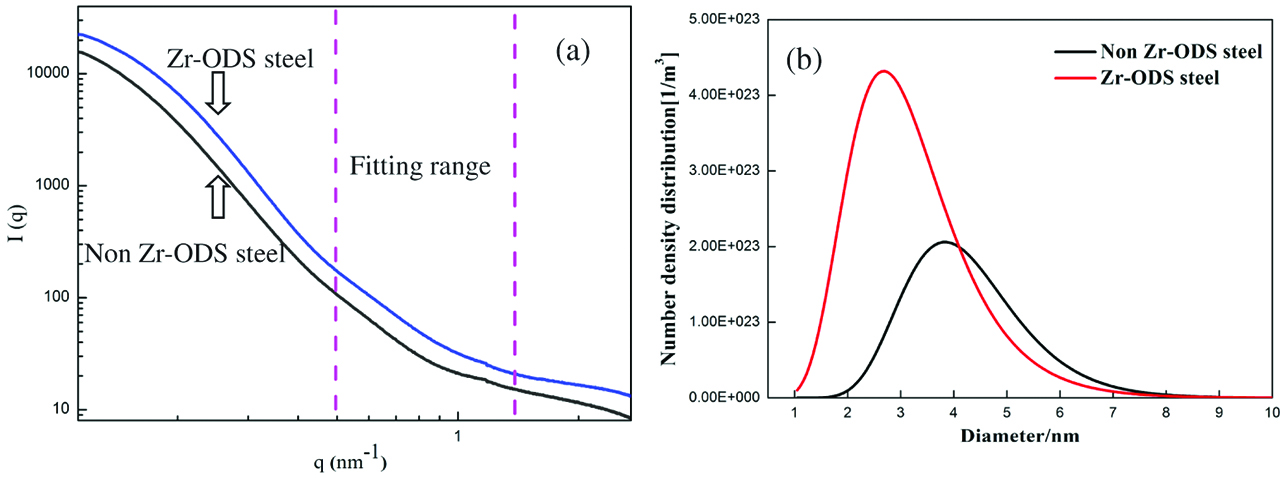

SAXS were employed in this study to obtain the statistical density and size distribution of oxides in the ODS steels from large specimen volume. Figure 6(a) shows the SAXS profiles from the ODS steels in the non Zr-ODS steel and Zr-ODS steel, respectively. According to the TEM results, most of oxides size is less than 10 nm. So the scattering vector range from 0.5 to 1.5 nm−1 is analyzed in this study. The size distributions and number density of the oxides in the specimens from SAXS fitting are shown in Figure 6(b). The average size decreases from 4.1 to 2.8 nm and the number density increases from 2.1×1023/m3 to 4.3×1023/m3 of oxides at an almost constant volume fraction by Zr addition. The average size obtained from SAXS is smaller than that from TEM. The statistics difference between SAS and TEM data probably is due to the resolution restriction of TEM and/or the larger analyzed volume of SAXS [28, 29].

(a) SAXS profiles of the ODS steels; (b) Number density and size distribution of oxides calculated from scattering curves.

Mechanical properties

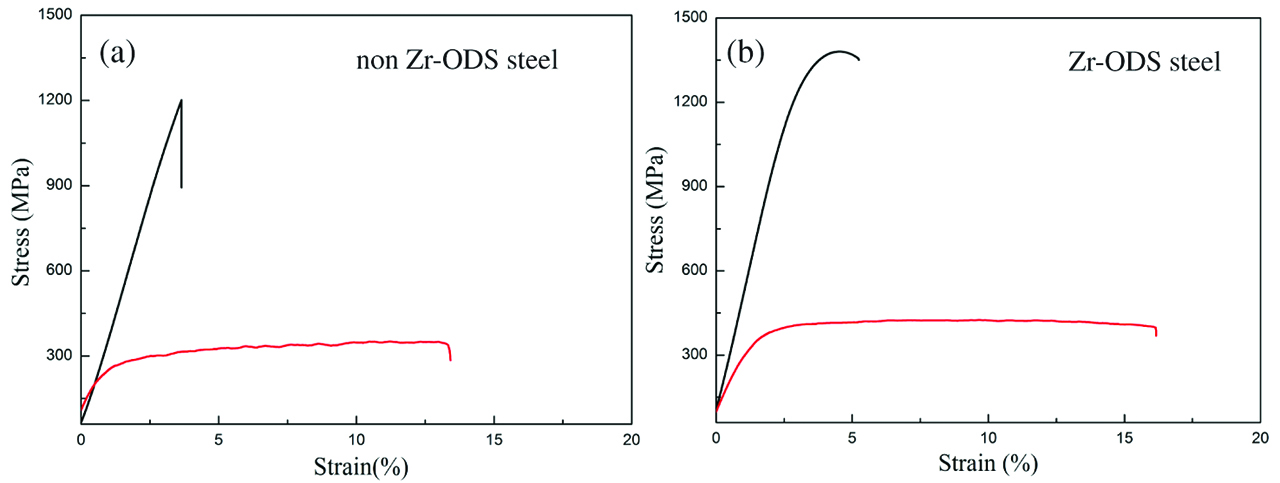

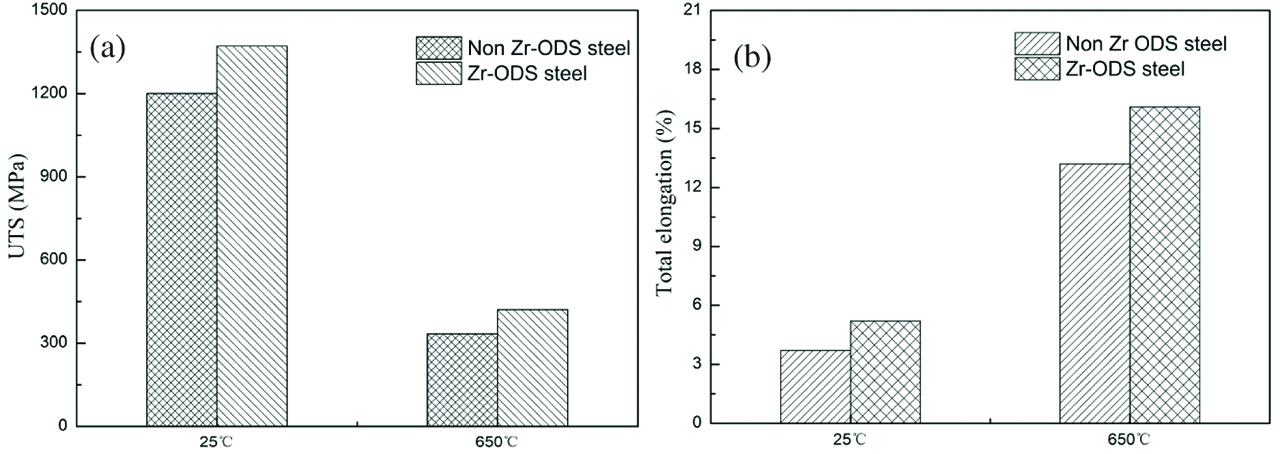

The addition of Zr element in the ODS steels modifies the size, density and composition of the oxides. In this regards, it also affects the mechanical properties of ODS steels. The micro-hardness increases from 431±6 to 552±8 HV by Zr addition. Increase of the hardness in ODS steel is attributed to the grain refinement, the average size decreases and the number density increases of oxides. Tensile tests were performed at room temperature (RT, 25°C) and 650°C, respectively. Figures 7 and 8 show tensile stress–strain curves of the ODS steels and average values of tensile properties of two ODS steels at each temperature. The ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and TE of non Zr-ODS steel are 1201 MPa, 3.7% and 334 MPa, 13.2% at RT and 650°C, respectively. The UTS and TE of Zr-ODS steel are 1372 MPa, 5.2% and 421 MPa, 16.1% at RT and 650°C, respectively. It is found that the UTS and the TE of ODS steel increases by Zr addition. With the increase of test temperature, it can be seen that the UTS of the ODS steels decreases and TE increases. The Zr-ODS steel exhibits the higher UTS and TE at RT and 650°C. This is because the higher density of oxides and the finer grains in Zr-ODS steel. Dou et al. [27] have proved that nano-size Y4Zr3O12 oxides are coherent with matrix. The coherent interface between the Y4Zr3O12 oxides and matrix hinders the formation and propagation of micro-crack which can effectively pin dislocations.

Tensile stress–strain curves of 15Cr-ODS steels at RT and 650°C (a) non Zr-ODS steel (b) Zr-ODS steel.

Tensile properties of 14Cr-ODS steels at RT and 650°C (a) UTS, (b) TE.

Conclusion

14Cr-ODS steels were prepared by MA and HIP. The effect of Zr additon on microstructure and mechanical properties were investigated. The main conclusions are as follows:

The presence of zirconium addition has improved the mechanical properties (microhardness, strength and ductility) of the ODS ferritic steel as a result of two linked factors: (a) a refinement of the ferritic matrix grains, and (b) formation of fine Y–Zr–O nano-oxides randomly dispersed in the matrix, which in part suppresses the formation of larger Y–O nano-oxides in the matrix.

The results reported here provide the foundation for understanding the unusual microstructure characteristics and outstanding irradiation tolerance of the oxide particles as well as the superior strength and will help to guide future design and optimization of ODS alloys.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51274121), the Provincial Natural Fund Project of Liaoning Province, China (201602396), the China Scholarship Council (201506080085), the Science and Technology Project of the Education Department of Liaoning Province, China (2016TSZD03), United Fund between State Key Laboratory of Metal Material for Marine Equipment and Application, Ansteel Group Corporation and University of Science and Technology Liaoning (301002515, 301002520). The TEM analyses were carried out at the Joint-use Facilities: Laboratory of Nano-Micro Material Analysis, Hokkaido University. In addition, Haijian Xu wants to thank, in particular, the patience, care and support from Xiaoting Wang for a long time. Will you marry me?

References

[1] K.L. Murty and I. Charit, J. Nucl. Mater., 383 (2008) 189–195.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2008.08.044Search in Google Scholar

[2] G. Odette, M. Alinger and B. Wirth, Annu. Rev. Mater. Res., 38 (2008) 471–503.10.1146/annurev.matsci.38.060407.130315Search in Google Scholar

[3] P. Yvon and F. Carre, J. Nucl. Mater., 385 (2009) 217–222.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2008.11.026Search in Google Scholar

[4] H.J. Xu, Z. Lu, D.M. Wang and C.M. Liu, Nucl. Eng. Technol., 49 (2017) 178–188.10.1016/j.net.2017.01.002Search in Google Scholar

[5] H.S. Cho and A. Kimura, J. Nucl. Mater., 367-370 (2007) 1180–1184.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2007.03.211Search in Google Scholar

[6] J.H. Schneibel, C.T. Liu, D.T. Hoelzer, M.J. Mills, P. Sarosi, T. Hayashi, U. Wendt and H. Heyse, Scr. Mater., 57 (2007) 1040–1043.10.1016/j.scriptamat.2007.07.029Search in Google Scholar

[7] H.J. Xu, Z. Lu, D.M. Wang, Z.W. Zhang, Y.F. Han and C.M. Liu, Mater. Sci. Technol., 33 (2017) 1790–1795.10.1080/02670836.2017.1318245Search in Google Scholar

[8] A. Steckmeyer, M. Praud, B. Fournier, J. Malaplate, J. Garnier, J.L. Béchade, I. Tournié, A. Tancray, A. Bougault and P. Bonnaillie, J. Nucl. Mater., 405 (2010) 95–100.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2010.07.027Search in Google Scholar

[9] H.J. Xu, Z. Lu, S. Ukai, N. Oono and C.M. Liu, J. Alloys Compd., 693 (2017) 177–187.10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.09.133Search in Google Scholar

[10] A. Certain, K.G. Field, T.R. Allen, M. Miller, J. Bentley and J. Busby, J. Nucl.Mater., 407 (2010) 2–9.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2010.07.002Search in Google Scholar

[11] H.J. Xu, Z. Lu, C.Y. Jia, H. Gao and C.M. Liu, High Temp. Mater. Proc., 35 (2016) 321–325.10.1515/htmp-2014-0163Search in Google Scholar

[12] A. Kimura, R. Kasada, N. Iwata, H. Kishimoto, C. Zhang, J. Isselin, P. Dou, J. Lee, N. Muthukumar, T. Okuda, M. Inoue, S. Ukai, S. Ohnuki, T. Fujisawa and T. Abe, J. Nucl. Mater., 417 (2011) 176–179.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2010.12.300Search in Google Scholar

[13] S. Ukai and M. Fujiwara, J. Nucl. Mater., 307-311 (Part 1) (2002) 749–757.10.1016/S0022-3115(02)01043-7Search in Google Scholar

[14] S. Ohtsuka, S. Ukai, M. Fujiwara, T. Kaito and T. Narita, J. Phys. Chem. Solids, 66 (2005) 571–575.10.1016/j.jpcs.2004.06.033Search in Google Scholar

[15] H. Kishimoto, M.J. Alinger, G.R. Odette and T. Yamamoto, J. Nucl. Mater., 329-333 (Part A) (2004) 369–371.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2004.04.044Search in Google Scholar

[16] D. Murali, B.K. Panigrahi, M.C. Valsakumar, S. Chandra, C.S. Sundar and B. Raj, J. Nucl. Mater., 403 (2010) 113–116.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2010.06.008Search in Google Scholar

[17] Y. Uchida, S. Ohnuki, N. Hashimoto, T. Suda, T. Nagai, T. Shibayama, K. Hamada, N. Akasaka, S. Yamashita, S. Ohstuka and T. Yoshitake, Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc., 981 (2007) 107–112.10.1557/PROC-981-0981-JJ07-09Search in Google Scholar

[18] R. Gao, T. Zhang, X.P. Wang, Q.F. Fang and C.S. Liu, J. Nucl. Mater., 444 (2014) 462–468.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.10.038Search in Google Scholar

[19] H.J. Xu, Z. Lu, C.Y. Jia, D.Z. Feng and C.M. Liu, High Temp. Mater. Proc., 35 (2016) 473–477.10.1515/htmp-2014-0229Search in Google Scholar

[20] J. Ilavsky and P.R. Jemian, Appl. Crystallogr., 42 (2009) 347–353.10.1107/S0021889809002222Search in Google Scholar

[21] G. Beaucage and D.W. Schaefer, J. Non-Cryst Solids., 172-174 (1994) 797–805.10.1016/0022-3093(94)90581-9Search in Google Scholar

[22] G. Beaucage, J. Appl. Crystallogr., 28 (1995) 717–728.10.1107/S0021889895005292Search in Google Scholar

[23] J.A. Potton, G.J. Daniell and B.D. Rainford, Appl. Crystallogr., 21 (1988) 663–668.10.1107/S0021889888004819Search in Google Scholar

[24] P. Pochet, P. Bellon, L. Chaffron and G. Martin, Mater. Sci. Forum., 207 (1996) 225–227.10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.225-227.207Search in Google Scholar

[25] H. Kotan, K.A. Darling, M. Saber, R.O. Scattergood and C.C. Koch, J. Mater. Sci., 48 (2013) 8402–8411.10.1007/s10853-013-7652-7Search in Google Scholar

[26] K.A. Darling, R.N. Chan, P.Z. Wong, J.E. Semones, R.O. Scattergood and C.C. Koch, Scr. Mater., 59 (2008) 530–533.10.1016/j.scriptamat.2008.04.045Search in Google Scholar

[27] P. Dou, A. Kimura, R. Kasada, T. Okuda, M. Inoue, S. Ukai, S. Ohnuki, T. Fujisaw and F. Abe, J. Nucl. Mater., 444 (2014) 441–453.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.10.028Search in Google Scholar

[28] P. Olier, J. Malaplate, M.H. Mathonet, D. Nunes, D. Hamon, L. Toualbi, Y. de Carlan and L. Chaffron, J. Nucl. Mater., 428 (2012) 40–46.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2011.10.042Search in Google Scholar

[29] N.J. Cunningham, Y. Wu, A. Etienne, E.M. Haney, G.R. Odette, E. Sterga, D.T. Hoelzer, Y.D. Kim, B.D. Wirth and S.A. Maloy, J. Nucl. Mater., 444 (2014) 35–38.10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.09.013Search in Google Scholar

© 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Public License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Research on the Influence of Furnace Structure on Copper Cooling Stave Life

- Influence of High Temperature Oxidation on Hydrogen Absorption and Degradation of Zircaloy-2 and Zr 700 Alloys

- Correlation between Travel Speed, Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Wear Characteristics of Ni-Based Hardfaced Deposits over 316LN Austenitic Stainless Steel

- Factors Influencing Gas Generation Behaviours of Lump Coal Used in COREX Gasifier

- Experiment Research on Pulverized Coal Combustion in the Tuyere of Oxygen Blast Furnace

- Phosphate Capacities of CaO–FeO–SiO2–Al2O3/Na2O/TiO2 Slags

- Microstructure and Interface Bonding Strength of WC-10Ni/NiCrBSi Composite Coating by Vacuum Brazing

- Refill Friction Stir Spot Welding of Dissimilar 6061/7075 Aluminum Alloy

- Solvothermal Synthesis and Magnetic Properties of Monodisperse Ni0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 Hollow Nanospheres

- On the Capability of Logarithmic-Power Model for Prediction of Hot Deformation Behavior of Alloy 800H at High Strain Rates

- 3D Heat Conductivity Model of Mold Based on Node Temperature Inheritance

- 3D Microstructure and Micromechanical Properties of Minerals in Vanadium-Titanium Sinter

- Effect of Martensite Structure and Carbide Precipitates on Mechanical Properties of Cr-Mo Alloy Steel with Different Cooling Rate

- The Interaction between Erosion Particle and Gas Stream in High Temperature Gas Burner Rig for Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Permittivity Study of a CuCl Residue at 13–450 °C and Elucidation of the Microwave Intensification Mechanism for Its Dechlorination

- Study on Carbothermal Reduction of Titania in Molten Iron

- The Sequence of the Phase Growth during Diffusion in Ti-Based Systems

- Growth Kinetics of CoB–Co2B Layers Using the Powder-Pack Boriding Process Assisted by a Direct Current Field

- High-Temperature Flow Behaviour and Constitutive Equations for a TC17 Titanium Alloy

- Research on Three-Roll Screw Rolling Process for Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy Bar

- Continuous Cooling Transformation of Undeformed and Deformed High Strength Crack-Arrest Steel Plates for Large Container Ships

- Formation Mechanism and Influence Factors of the Sticker between Solidified Shell and Mold in Continuous Casting of Steel

- Casting Defects in Transition Layer of Cu/Al Composite Castings Prepared Using Pouring Aluminum Method and Their Formation Mechanism

- Effect of Current on Segregation and Inclusions Characteristics of Dual Alloy Ingot Processed by Electroslag Remelting

- Investigation of Growth Kinetics of Fe2B Layers on AISI 1518 Steel by the Integral Method

- Microstructural Evolution and Phase Transformation on the X-Y Surface of Inconel 718 Ni-Based Alloys Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting under Different Heat Treatment

- Characterization of Mn-Doped Co3O4 Thin Films Prepared by Sol Gel-Based Dip-Coating Process

- Deposition Characteristics of Multitrack Overlayby Plasma Transferred Arc Welding on SS316Lwith Co-Cr Based Alloy – Influence ofProcess Parameters

- Elastic Moduli and Elastic Constants of Alloy AuCuSi With FCC Structure Under Pressure

- Effect of Cl on Softening and Melting Behaviors of BF Burden

- Effect of MgO Injection on Smelting in a Blast Furnace

- Structural Characteristics and Hydration Kinetics of Oxidized Steel Slag in a CaO-FeO-SiO2-MgO System

- Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Oxidation Roasting of Oxide–Sulphide Zinc Ore with Addition of Manganese Dioxide Using Response Surface Methodology

- Hydraulic Study of Bubble Migration in Liquid Titanium Alloy Melt during Vertical Centrifugal Casting Process

- Investigation on Double Wire Metal Inert Gas Welding of A7N01-T4 Aluminum Alloy in High-Speed Welding

- Oxidation Behaviour of Welded ASTM-SA210 GrA1 Boiler Tube Steels under Cyclic Conditions at 900°C in Air

- Study on the Evolution of Damage Degradation at Different Temperatures and Strain Rates for Ti-6Al-4V Alloy

- Pack-Boriding of Pure Iron with Powder Mixtures Containing ZrB2

- Evolution of Interfacial Features of MnO-SiO2 Type Inclusions/Steel Matrix during Isothermal Heating at Low Temperatures

- Effect of MgO/Al2O3 Ratio on Viscosity of Blast Furnace Primary Slag

- The Microstructure and Property of the Heat Affected zone in C-Mn Steel Treated by Rare Earth

- Microwave-Assisted Molten-Salt Facile Synthesis of Chromium Carbide (Cr3C2) Coatings on the Diamond Particles

- Effects of B on the Hot Ductility of Fe-36Ni Invar Alloy

- Impurity Distribution after Solidification of Hypereutectic Al-Si Melts and Eutectic Al-Si Melt

- Induced Electro-Deposition of High Melting-Point Phases on MgO–C Refractory in CaO–Al2O3–SiO2 – (MgO) Slag at 1773 K

- Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of 14Cr-ODS Steels with Zr Addition

- A Review of Boron-Rich Silicon Borides Basedon Thermodynamic Stability and Transport Properties of High-Temperature Thermoelectric Materials

- Siliceous Manganese Ore from Eastern India:A Potential Resource for Ferrosilicon-Manganese Production

- A Strain-Compensated Constitutive Model for Describing the Hot Compressive Deformation Behaviors of an Aged Inconel 718 Superalloy

- Surface Alloys of 0.45 C Carbon Steel Produced by High Current Pulsed Electron Beam

- Deformation Behavior and Processing Map during Isothermal Hot Compression of 49MnVS3 Non-Quenched and Tempered Steel

- A Constitutive Equation for Predicting Elevated Temperature Flow Behavior of BFe10-1-2 Cupronickel Alloy through Double Multiple Nonlinear Regression

- Oxidation Behavior of Ferritic Steel T22 Exposed to Supercritical Water

- A Multi Scale Strategy for Simulation of Microstructural Evolutions in Friction Stir Welding of Duplex Titanium Alloy

- Partition Behavior of Alloying Elements in Nickel-Based Alloys and Their Activity Interaction Parameters and Infinite Dilution Activity Coefficients

- Influence of Heating on Tensile Physical-Mechanical Properties of Granite

- Comparison of Al-Zn-Mg Alloy P-MIG Welded Joints Filled with Different Wires

- Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Thick Plate Friction Stir Welds for 6082-T6 Aluminum Alloy

- Research Article

- Kinetics of oxide scale growth on a (Ti, Mo)5Si3 based oxidation resistant Mo-Ti-Si alloy at 900-1300∘C

- Calorimetric study on Bi-Cu-Sn alloys

- Mineralogical Phase of Slag and Its Effect on Dephosphorization during Converter Steelmaking Using Slag-Remaining Technology

- Controllability of joint integrity and mechanical properties of friction stir welded 6061-T6 aluminum and AZ31B magnesium alloys based on stationary shoulder

- Cellular Automaton Modeling of Phase Transformation of U-Nb Alloys during Solidification and Consequent Cooling Process

- The effect of MgTiO3Adding on Inclusion Characteristics

- Cutting performance of a functionally graded cemented carbide tool prepared by microwave heating and nitriding sintering

- Creep behaviour and life assessment of a cast nickel – base superalloy MAR – M247

- Failure mechanism and acoustic emission signal characteristics of coatings under the condition of impact indentation

- Reducing Surface Cracks and Improving Cleanliness of H-Beam Blanks in Continuous Casting — Improving continuous casting of H-beam blanks

- Rhodium influence on the microstructure and oxidation behaviour of aluminide coatings deposited on pure nickel and nickel based superalloy

- The effect of Nb content on precipitates, microstructure and texture of grain oriented silicon steel

- Effect of Arc Power on the Wear and High-temperature Oxidation Resistances of Plasma-Sprayed Fe-based Amorphous Coatings

- Short Communication

- Novel Combined Feeding Approach to Produce Quality Al6061 Composites for Heat Sinks

- Research Article

- Micromorphology change and microstructure of Cu-P based amorphous filler during heating process

- Controlling residual stress and distortion of friction stir welding joint by external stationary shoulder

- Research on the ingot shrinkage in the electroslag remelting withdrawal process for 9Cr3Mo roller

- Production of Mo2NiB2 Based Hard Alloys by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis

- The Morphology Analysis of Plasma-Sprayed Cast Iron Splats at Different Substrate Temperatures via Fractal Dimension and Circularity Methods

- A Comparative Study on Johnson–Cook, Modified Johnson–Cook, Modified Zerilli–Armstrong and Arrhenius-Type Constitutive Models to Predict Hot Deformation Behavior of TA2

- Dynamic absorption efficiency of paracetamol powder in microwave drying

- Preparation and Properties of Blast Furnace Slag Glass Ceramics Containing Cr2O3

- Influence of unburned pulverized coal on gasification reaction of coke in blast furnace

- Effect of PWHT Conditions on Toughness and Creep Rupture Strength in Modified 9Cr-1Mo Steel Welds

- Role of B2O3 on structure and shear-thinning property in CaO–SiO2–Na2O-based mold fluxes

- Effect of Acid Slag Treatment on the Inclusions in GCr15 Bearing Steel

- Recovery of Iron and Zinc from Blast Furnace Dust Using Iron-Bath Reduction

- Phase Analysis and Microstructural Investigations of Ce2Zr2O7 for High-Temperature Coatings on Ni-Base Superalloy Substrates

- Combustion Characteristics and Kinetics Study of Pulverized Coal and Semi-Coke

- Mechanical and Electrochemical Characterization of Supersolidus Sintered Austenitic Stainless Steel (316 L)

- Synthesis and characterization of Cu doped chromium oxide (Cr2O3) thin films

- Ladle Nozzle Clogging during casting of Silicon-Steel

- Thermodynamics and Industrial Trial on Increasing the Carbon Content at the BOF Endpoint to Produce Ultra-Low Carbon IF Steel by BOF-RH-CSP Process

- Research Article

- Effect of Boundary Conditions on Residual Stresses and Distortion in 316 Stainless Steel Butt Welded Plate

- Numerical Analysis on Effect of Additional Gas Injection on Characteristics around Raceway in Melter Gasifier

- Variation on thermal damage rate of granite specimen with thermal cycle treatment

- Effects of Fluoride and Sulphate Mineralizers on the Properties of Reconstructed Steel Slag

- Effect of Basicity on Precipitation of Spinel Crystals in a CaO-SiO2-MgO-Cr2O3-FeO System

- Review Article

- Exploitation of Mold Flux for the Ti-bearing Welding Wire Steel ER80-G

- Research Article

- Furnace heat prediction and control model and its application to large blast furnace

- Effects of Different Solid Solution Temperatures on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of the AA7075 Alloy After T6 Heat Treatment

- Study of the Viscosity of a La2O3-SiO2-FeO Slag System

- Tensile Deformation and Work Hardening Behaviour of AISI 431 Martensitic Stainless Steel at Elevated Temperatures

- The Effectiveness of Reinforcement and Processing on Mechanical Properties, Wear Behavior and Damping Response of Aluminum Matrix Composites

Articles in the same Issue

- Frontmatter

- Review Article

- Research on the Influence of Furnace Structure on Copper Cooling Stave Life

- Influence of High Temperature Oxidation on Hydrogen Absorption and Degradation of Zircaloy-2 and Zr 700 Alloys

- Correlation between Travel Speed, Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Wear Characteristics of Ni-Based Hardfaced Deposits over 316LN Austenitic Stainless Steel

- Factors Influencing Gas Generation Behaviours of Lump Coal Used in COREX Gasifier

- Experiment Research on Pulverized Coal Combustion in the Tuyere of Oxygen Blast Furnace

- Phosphate Capacities of CaO–FeO–SiO2–Al2O3/Na2O/TiO2 Slags

- Microstructure and Interface Bonding Strength of WC-10Ni/NiCrBSi Composite Coating by Vacuum Brazing

- Refill Friction Stir Spot Welding of Dissimilar 6061/7075 Aluminum Alloy

- Solvothermal Synthesis and Magnetic Properties of Monodisperse Ni0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 Hollow Nanospheres

- On the Capability of Logarithmic-Power Model for Prediction of Hot Deformation Behavior of Alloy 800H at High Strain Rates

- 3D Heat Conductivity Model of Mold Based on Node Temperature Inheritance

- 3D Microstructure and Micromechanical Properties of Minerals in Vanadium-Titanium Sinter

- Effect of Martensite Structure and Carbide Precipitates on Mechanical Properties of Cr-Mo Alloy Steel with Different Cooling Rate

- The Interaction between Erosion Particle and Gas Stream in High Temperature Gas Burner Rig for Thermal Barrier Coatings

- Permittivity Study of a CuCl Residue at 13–450 °C and Elucidation of the Microwave Intensification Mechanism for Its Dechlorination

- Study on Carbothermal Reduction of Titania in Molten Iron

- The Sequence of the Phase Growth during Diffusion in Ti-Based Systems

- Growth Kinetics of CoB–Co2B Layers Using the Powder-Pack Boriding Process Assisted by a Direct Current Field

- High-Temperature Flow Behaviour and Constitutive Equations for a TC17 Titanium Alloy

- Research on Three-Roll Screw Rolling Process for Ti6Al4V Titanium Alloy Bar

- Continuous Cooling Transformation of Undeformed and Deformed High Strength Crack-Arrest Steel Plates for Large Container Ships

- Formation Mechanism and Influence Factors of the Sticker between Solidified Shell and Mold in Continuous Casting of Steel

- Casting Defects in Transition Layer of Cu/Al Composite Castings Prepared Using Pouring Aluminum Method and Their Formation Mechanism

- Effect of Current on Segregation and Inclusions Characteristics of Dual Alloy Ingot Processed by Electroslag Remelting

- Investigation of Growth Kinetics of Fe2B Layers on AISI 1518 Steel by the Integral Method

- Microstructural Evolution and Phase Transformation on the X-Y Surface of Inconel 718 Ni-Based Alloys Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting under Different Heat Treatment

- Characterization of Mn-Doped Co3O4 Thin Films Prepared by Sol Gel-Based Dip-Coating Process

- Deposition Characteristics of Multitrack Overlayby Plasma Transferred Arc Welding on SS316Lwith Co-Cr Based Alloy – Influence ofProcess Parameters

- Elastic Moduli and Elastic Constants of Alloy AuCuSi With FCC Structure Under Pressure

- Effect of Cl on Softening and Melting Behaviors of BF Burden

- Effect of MgO Injection on Smelting in a Blast Furnace

- Structural Characteristics and Hydration Kinetics of Oxidized Steel Slag in a CaO-FeO-SiO2-MgO System

- Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Oxidation Roasting of Oxide–Sulphide Zinc Ore with Addition of Manganese Dioxide Using Response Surface Methodology

- Hydraulic Study of Bubble Migration in Liquid Titanium Alloy Melt during Vertical Centrifugal Casting Process

- Investigation on Double Wire Metal Inert Gas Welding of A7N01-T4 Aluminum Alloy in High-Speed Welding

- Oxidation Behaviour of Welded ASTM-SA210 GrA1 Boiler Tube Steels under Cyclic Conditions at 900°C in Air

- Study on the Evolution of Damage Degradation at Different Temperatures and Strain Rates for Ti-6Al-4V Alloy

- Pack-Boriding of Pure Iron with Powder Mixtures Containing ZrB2

- Evolution of Interfacial Features of MnO-SiO2 Type Inclusions/Steel Matrix during Isothermal Heating at Low Temperatures

- Effect of MgO/Al2O3 Ratio on Viscosity of Blast Furnace Primary Slag

- The Microstructure and Property of the Heat Affected zone in C-Mn Steel Treated by Rare Earth

- Microwave-Assisted Molten-Salt Facile Synthesis of Chromium Carbide (Cr3C2) Coatings on the Diamond Particles

- Effects of B on the Hot Ductility of Fe-36Ni Invar Alloy

- Impurity Distribution after Solidification of Hypereutectic Al-Si Melts and Eutectic Al-Si Melt

- Induced Electro-Deposition of High Melting-Point Phases on MgO–C Refractory in CaO–Al2O3–SiO2 – (MgO) Slag at 1773 K

- Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of 14Cr-ODS Steels with Zr Addition

- A Review of Boron-Rich Silicon Borides Basedon Thermodynamic Stability and Transport Properties of High-Temperature Thermoelectric Materials

- Siliceous Manganese Ore from Eastern India:A Potential Resource for Ferrosilicon-Manganese Production

- A Strain-Compensated Constitutive Model for Describing the Hot Compressive Deformation Behaviors of an Aged Inconel 718 Superalloy

- Surface Alloys of 0.45 C Carbon Steel Produced by High Current Pulsed Electron Beam

- Deformation Behavior and Processing Map during Isothermal Hot Compression of 49MnVS3 Non-Quenched and Tempered Steel

- A Constitutive Equation for Predicting Elevated Temperature Flow Behavior of BFe10-1-2 Cupronickel Alloy through Double Multiple Nonlinear Regression

- Oxidation Behavior of Ferritic Steel T22 Exposed to Supercritical Water

- A Multi Scale Strategy for Simulation of Microstructural Evolutions in Friction Stir Welding of Duplex Titanium Alloy

- Partition Behavior of Alloying Elements in Nickel-Based Alloys and Their Activity Interaction Parameters and Infinite Dilution Activity Coefficients

- Influence of Heating on Tensile Physical-Mechanical Properties of Granite

- Comparison of Al-Zn-Mg Alloy P-MIG Welded Joints Filled with Different Wires

- Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Thick Plate Friction Stir Welds for 6082-T6 Aluminum Alloy

- Research Article

- Kinetics of oxide scale growth on a (Ti, Mo)5Si3 based oxidation resistant Mo-Ti-Si alloy at 900-1300∘C

- Calorimetric study on Bi-Cu-Sn alloys

- Mineralogical Phase of Slag and Its Effect on Dephosphorization during Converter Steelmaking Using Slag-Remaining Technology

- Controllability of joint integrity and mechanical properties of friction stir welded 6061-T6 aluminum and AZ31B magnesium alloys based on stationary shoulder

- Cellular Automaton Modeling of Phase Transformation of U-Nb Alloys during Solidification and Consequent Cooling Process

- The effect of MgTiO3Adding on Inclusion Characteristics

- Cutting performance of a functionally graded cemented carbide tool prepared by microwave heating and nitriding sintering

- Creep behaviour and life assessment of a cast nickel – base superalloy MAR – M247

- Failure mechanism and acoustic emission signal characteristics of coatings under the condition of impact indentation

- Reducing Surface Cracks and Improving Cleanliness of H-Beam Blanks in Continuous Casting — Improving continuous casting of H-beam blanks

- Rhodium influence on the microstructure and oxidation behaviour of aluminide coatings deposited on pure nickel and nickel based superalloy

- The effect of Nb content on precipitates, microstructure and texture of grain oriented silicon steel

- Effect of Arc Power on the Wear and High-temperature Oxidation Resistances of Plasma-Sprayed Fe-based Amorphous Coatings

- Short Communication

- Novel Combined Feeding Approach to Produce Quality Al6061 Composites for Heat Sinks

- Research Article

- Micromorphology change and microstructure of Cu-P based amorphous filler during heating process

- Controlling residual stress and distortion of friction stir welding joint by external stationary shoulder

- Research on the ingot shrinkage in the electroslag remelting withdrawal process for 9Cr3Mo roller

- Production of Mo2NiB2 Based Hard Alloys by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis

- The Morphology Analysis of Plasma-Sprayed Cast Iron Splats at Different Substrate Temperatures via Fractal Dimension and Circularity Methods

- A Comparative Study on Johnson–Cook, Modified Johnson–Cook, Modified Zerilli–Armstrong and Arrhenius-Type Constitutive Models to Predict Hot Deformation Behavior of TA2

- Dynamic absorption efficiency of paracetamol powder in microwave drying

- Preparation and Properties of Blast Furnace Slag Glass Ceramics Containing Cr2O3

- Influence of unburned pulverized coal on gasification reaction of coke in blast furnace

- Effect of PWHT Conditions on Toughness and Creep Rupture Strength in Modified 9Cr-1Mo Steel Welds

- Role of B2O3 on structure and shear-thinning property in CaO–SiO2–Na2O-based mold fluxes

- Effect of Acid Slag Treatment on the Inclusions in GCr15 Bearing Steel

- Recovery of Iron and Zinc from Blast Furnace Dust Using Iron-Bath Reduction

- Phase Analysis and Microstructural Investigations of Ce2Zr2O7 for High-Temperature Coatings on Ni-Base Superalloy Substrates

- Combustion Characteristics and Kinetics Study of Pulverized Coal and Semi-Coke

- Mechanical and Electrochemical Characterization of Supersolidus Sintered Austenitic Stainless Steel (316 L)

- Synthesis and characterization of Cu doped chromium oxide (Cr2O3) thin films

- Ladle Nozzle Clogging during casting of Silicon-Steel

- Thermodynamics and Industrial Trial on Increasing the Carbon Content at the BOF Endpoint to Produce Ultra-Low Carbon IF Steel by BOF-RH-CSP Process

- Research Article

- Effect of Boundary Conditions on Residual Stresses and Distortion in 316 Stainless Steel Butt Welded Plate

- Numerical Analysis on Effect of Additional Gas Injection on Characteristics around Raceway in Melter Gasifier

- Variation on thermal damage rate of granite specimen with thermal cycle treatment

- Effects of Fluoride and Sulphate Mineralizers on the Properties of Reconstructed Steel Slag

- Effect of Basicity on Precipitation of Spinel Crystals in a CaO-SiO2-MgO-Cr2O3-FeO System

- Review Article

- Exploitation of Mold Flux for the Ti-bearing Welding Wire Steel ER80-G

- Research Article

- Furnace heat prediction and control model and its application to large blast furnace

- Effects of Different Solid Solution Temperatures on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of the AA7075 Alloy After T6 Heat Treatment

- Study of the Viscosity of a La2O3-SiO2-FeO Slag System

- Tensile Deformation and Work Hardening Behaviour of AISI 431 Martensitic Stainless Steel at Elevated Temperatures

- The Effectiveness of Reinforcement and Processing on Mechanical Properties, Wear Behavior and Damping Response of Aluminum Matrix Composites