Abstract

A series of polyepoxide resins doped by lead oxide with low concentrations were fabricated in order to study the impacts of low PbO concentrations on the fabricated composites’ physical- and radiation-shielding properties. The epoxide resin was reinforced with the PbO compound with concentrations 0, 5, and 10 wt%. The density measurements affirmed that by elevating the PbO concentration between 0 and 10 wt%, the composites’ density increased from 1.103 to 1.185 g·cm−3. This low-density increase was echoed in the fabricated composites’ radiation-shielding properties, where the Monte Carlo simulation code affirmed a linear attenuation coefficient increase by factors of 230%, 218%, 24%, and 10%, respectively, at 59, 121, 356, and 662 keV. The half-value layer, mean free path, and transmission factor indicated a linear attenuation coefficient enhancement.

1 Introduction

As more technology starts to rely on radiation for operation, there is a growing need for efficient radiation protection materials. Radiation is widely employed in various industries and technological fields, including food processing, agriculture, and medical applications. On the contrary, radiation can inflict significant damage on living things and their surroundings if they are subjected to photons with very high energy for an extended length of time (1,2,3,4). When dealing with radiation, it is important to use radiation-shielding materials. These materials can be used to absorb high-energy photons (5,6,7,8,9). These shields are not only very good at preventing radiation from penetrating but they can also be tailored to have a range of qualities, depending on the situation, in order to produce them as effective as it is physically feasible for them to be. The materials used for radiation protection are required to have certain qualities, such as being lightweight, transparent, resistant to chemical exposure, and capable of absorbing a large range of photons (10). Concrete mixtures, for instance, could be efficient in absorbing neutrons and gamma radiation when mixed with certain additives; as a result, they are frequently utilized as a lining material for X-ray facilities. Furthermore, over time, concretes tend to form cracks and lose their water content; consequently, these qualities need to be taken into consideration, and either the concrete itself has to be improved or the characteristics themselves need to be improved (11,12,13,14). As an alternative to traditional concrete and glass shielding materials, recent research has looked into the radiation-shielding qualities of various polymer types with low density, the capacity to fabricate complex shapes, optical transparency, low fabrication costs, and durability (15,16,17,18,19).

Epoxy resin represents a polymer form featuring a high concentration of hydrogen atoms, which have the ability to significantly attenuate the impact of neutrons. Epoxy composites are also appropriate for use in severe environments, such as those found in nuclear power plants, as a result of their exceptional mechanical qualities, remarkable resistance to chemicals, and high adhesive strength (20). It is possible to further strengthen the epoxy’s shielding capabilities by adding additives that have high atomic numbers. Such supplements increase the probability of the shield interacting in some manner with the photons that enter the system, thus elevating the amount of blocked radiation (21). Moreover, incorporating PbO in the appropriate proportions can significantly raise the effective atomic number and lower the mean free path for the shields. In addition, using PbO is a suitable method for lowering the transmission of photons through various shielding composites such as concretes, glasses, and polymers (22,23). According to the World Health Organization report (International Chemical Safety Cards [ICSC-0288]), lead oxides have high toxicity effects on both human health and the environment. The harmful effects of PbO reach people through lead airborne particles (lead dust), which can quickly enter the human body when dispersed, especially if PbO is powdered. Bone marrow, the central nervous system, the kidneys, the lungs, and the peripheral nervous system are all impacted by PbO dust. Then, to avoid the risks of PbO and benefit from its advantages in the field of radiation protection field, researchers insert the PbO compounds in glasses and polymetric matrixes to reduce the PbO airborne emission. Recently, many researchers have studied PbO’s impact on various types of polymers’ radiation-shielding properties (24,25,26).

The evaluation of radiation-shielding properties is usually performed through various methods, including experimentally, Monte Carlo (MC) simulation (Monte-Carlo N-particle (MCNP) transport codes, FLUKA, Geant4, and EPICS2017 Library) (27,28,29,30), and theoretical calculations utilizing XCOM databases and their based programs (WinXCOM and Phy-X/PSD).

MC simulation, when applicable to the field of radiation technologies, is a useful analytical method for simulating the transport of gamma radiation based on the probabilistic distribution of radiation’s interaction with materials. When it is difficult to experiment, MC simulation is an important technique that can be used to acquire some radiation-shielding parameters of a material. This is especially true in situations where it is not possible to measure these values experimentally. Recently, a considerable number of investigations have explored different polymers’ radiation-shielding performance using the MC technique (31,32,33).

This research aims to develop a non-expensive shielding polymetric material with high shielding efficiency. Therefore, lead oxide was employed to enhance the epoxy resin’s gamma-ray shielding capacities to stand against the low and intermediate gamma-ray energies utilized in medical and scientific applications.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Synthesis

Three samples of lead oxide doped epoxy were fabricated at room temperature. The epoxy material has two parts: the polyepoxide resin (Part A) and the solidification (Part B); both Part A and Part B components were bought from SlabDOC (Ivanovo, Russia). First, the epoxy components were mixed together for 10 min with ratios 2:1 for Part A:Part B. After that, the three samples were fabricated according to the equation (100 − x) (Part A + Part B) + xPbO, where x = 0, 5, and 10 wt%. The commercial PbO chemical compound was supplied by Khimreaktivsnab (Yekaterinburg, Russia). The required amount from PbO was weighed with an electric balance (accuracy: ±0.01 mg) and mixed with epoxy (Part A + Part B) using vertical stirring for 10 min. After that, a 3 cm × 3 cm silicon mold was employed to mold the fabricated samples, as illustrated in Figure 1. Measurement of the fabricated samples’ density was done through a density meter (MXBAOHENG MH-300A; Guangdong, China), where the immersing liquid was water. The accuracy of density measurement is found in the range of ±0.001 g·cm−3.

The fabricated E-PbO composites.

A Tescan MIRA3 scanning electron microscope (SEM; Brno, Czech Republic) was used to capture the filler distributions within the synthesized composite-based epoxy resin (acceleration voltage: 20 kV; micrograph magnification: 1.66k×). The energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) was utilized in order to determine the fabricated E-PbO composite’s elemental chemical composition, as illustrated in Table 1.

The fabricated composites’ elemental chemical composition as measured by EDX

| Elemental chemical composition (wt%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| E-PbO0 | E-PbO5 | E-PbO10 | |

| C | 70.1 | 67.7 | 66.2 |

| O | 29.8 | 29.1 | 28.3 |

| Cl | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Si | 0 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Ca | 0 | 0.1 | |

| Fe | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Pb | 0 | 2.8 | 5.7 |

| Density (g‧cm−3) | 1.103 | 1.159 | 1.185 |

2.2 Radiation-shielding evaluation

MC simulation (MCNP-5 code) was employed to evaluate the γ-ray shielding properties in terms of the γ-photons’ average track length (ATL) in the fabricated material cell (34). This evaluation was performed using tally F4 which is dependent on the estimation of the material cell’s average flux per unit volume. The geometry used for the simulation process consisted of an outer shielding cylinder of lead with a thickness of 5 cm. The shielding cylinder is filled with air at room temperature and contains the radioactive source, collimator, fabricated materials, and detectors. Each of the mentioned components is defined in the input file through the cell, importance, material, and surface, as well as the source and tally cards (Figure 2). The radioactive source was introduced to the source card to emit gamma photons in the range between 0.033 and 1.332 MeV in the Z direction. Each source’s likelihood of gamma emission and the distribution of such emission were also entered into the SDEF card. The location of the radioactive source is at the center cell at (0 0 0) of the outer shielding cylinder. The fabricated material’s chemical composition and density are presented in Table 1 introduced to the material card. The input file was adjusted to stop the photon interaction after the emission of 106 historical, while for the extraction of the gamma photons’ interaction cross-section at a number of energies, the ENDF/B.VI.8 was utilized. The average flux per unit material cell, as well as the ATL of the material cell’s gamma-photons, were employed to estimate the shielding parameters such as the linear attenuation coefficient (µ, cm−1) through the equations that follows (35,36,37,38).

where N o refers to the total number of emitted photons and N t indicates the number of transmitted photons, which helped calculate the efficiency of radiation protection (RPE, %) and the transmission factor (TF, %). The half-value thickness (Δ 0.5, cm) is given by

The MC simulation MCNP-5 setup as presented in the input file.

Additionally, the fabricated E-PbO composites’ µ values were measured experimentally utilizing a Bicron NaI (Tl) scintillation detector and two gamma-ray sources (Cs-137 and Co-60; average energies: 662 and 1,252 keV). The scintillation detector consists of a 76 mm × 76 mm NaI (Tl) crystal sealed with a photomultiplier tube (PMT) in an aluminum case. The PMT detector is shielded by a 0.6 mm thick copper screen from the resulting X-ray radiation and a cylindrical lead chamber from external radiation and is connected to the Accuspec card. For each sample, both N t and N o were recorded using a Maestro software program connected to the NaI(Tl) crystal. After that, the fabricated composites’ thickness was measured with an X-PERT digital caliper (Moscow, Russia) (measurement range: 0–150 mm; measurement inaccuracy: 0.01 mm). The fabricated composites’ µ values are provided by the slope of the relation between ln(N o/N t).

3 Results and discussion

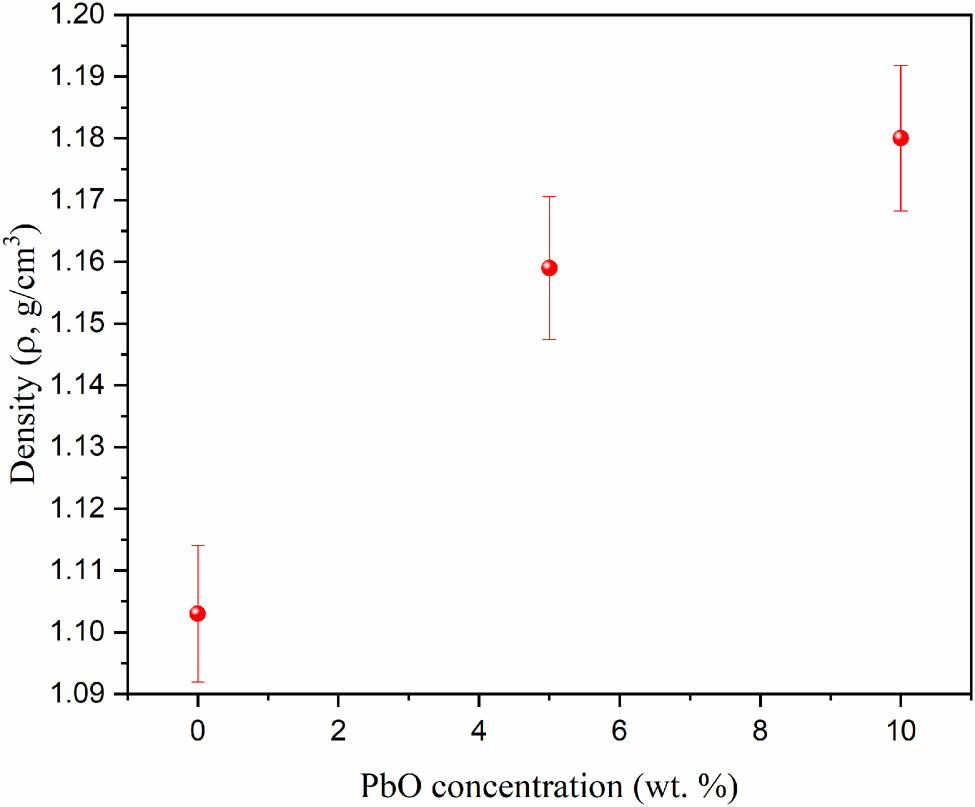

The relationship between the epoxy resin samples’ density and their PbO concentration is plotted in Figure 3. The density of the pure epoxy sample (E-PbO 0) is 1.103 g·cm−3, which increases to 1.159 and 1.185 g·cm−3 after introducing 5% and 10% PbO, respectively, into the composite. The increase in density is attributed to the high density of lead. It is important to study the prepared samples’ density as one of the most important factors that affect the radiation-shielding properties of different materials. This is because of the effect that density has on many parameters that are used to evaluate the attenuation capability of a sample.

Variation of the fabricated composite density vs. the doping PbO ratio (wt%).

The PbO distribution in E-PbO and E-PbO is shown in Figure 4, with the images revealing the filler’s homogenous distribution within the epoxy resin. According to the analysis of the SEM image, the size of the particles for the PbO fillers was in the 7–11 µm range.

SEM images for the fabricated composites: (a) pure curing epoxy (E-Pbo 0), (b) pure PbO, (c) E-PbO10, and (d) particle size distribution for the PbO compound in the fabricated composites.

Figure 5 shows the fabricated E-PbO composites’ mass attenuation coefficient (MAC) as an incident γ-photon energy function. This figure compares the simulated MAC values obtained by MCNP to the theoretical ones obtained from XCOM. The MAC values from both methods are very close together for the three tested samples at all energies. For instance, at 302 keV, the MAC values of E-Pb 10 are 0.1266 and 0.1270 cm2·g−1 from MCNP and XCOM, respectively, while at 1,173 keV, they are equal to 0.0622 and 0.626 cm2·g−1 from MCNP and XCOM, respectively. Since the two methods returned that has a very small difference, we can reliably use the results obtained from MNCP to analyze the radiation-shielding properties of the epoxy composites.

The E-PbO composites’ MAC variation.

The relationship between MAC and PbO concentration is illustrated in Figure 6 to demonstrate the effect that PbO has on the radiation-shielding properties of the prepared composites. At low energies, such as 121 keV, the MAC values increase linearly with PbO concentration. More specifically, pure epoxy has an MAC of 0.157 cm2·g−1, while E-PbO 10 has an MAC of 0.466 cm2·g−1. This high dependency occurs because of the photoelectric effect, the most important photon interaction process at low energies, which highly depends on the atomic number of the absorber. Because of Pb’s high atomic number, when adding 5% or 10% PbO into the composite, the MAC of these samples increased by around 5% and 10%, respectively, at this energy. At higher energies, such as 662 and 1,252 keV, however, the MAC values have a very weak dependency on the PbO. This difference is due to the lack of dominance of the photoelectric effect in this energy range, and in its place, the Compton scattering effect becomes more prevalent, which has a weak dependence on the atomic number of the absorber. For instance, the MAC of pure epoxy at 661 keV is 0.08207 cm2·g−1, while E-PbO 10’s MAC is 0.0832 cm2·g−1 at the same energy. Therefore, the MAC values are slightly increased at these two energies.

Variation of the fabricated E-PbO composites’ µ m values as a function of the PbO doping concentrations.

Additionally, the evaluation of the fabricated E-PbO composites’ µ values was grounded in the simulated ATL and measured experimentally using the NaI(Tl) detector, as shown in Table 2. The measurements emerging from the experiment reveal the µ values at 662 keV to vary between 0.097 and 0.102 cm−1 with the concentration of PbO between 0 and 10 wt%, respectively. The mentioned experimental results were found in agreement with the simulated MCNP-5 results, with a difference reaching ∼9% at gamma-ray energy of 1,252 keV (average energy for Co-60 radioactive energy).

Comparison between the experimentally measured µ values using the NaI detector and those of simulated MCNP-5’ µ values

| Energy (keV) | Linear attenuation coefficient (µ, cm−1) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-PbO0 | E-PbO5 | E-PbO10 | |||||||

| MCNP | EXP | Diff. (%) | MCNP | EXP | Diff. (%) | MCNP | EXP | Diff. (%) | |

| 59 | 0.249 | 0.533 | 0.822 | ||||||

| 121 | 0.173 | 0.361 | 0.552 | ||||||

| 302 | 0.125 | 0.147 | 0.166 | ||||||

| 356 | 0.117 | 0.133 | 0.146 | ||||||

| 383 | 0.114 | 0.128 | 0.139 | ||||||

| 661 | 0.091 | 0.097 | 7.000 | 0.096 | 0.099 | 3.100 | 0.100 | 0.102 | 2.200 |

| 1,173 | 0.069 | 0.072 | 0.074 | ||||||

| 1,252 | 0.067 | 0.073 | 9.500 | 0.070 | 0.074 | 5.600 | 0.071 | 0.074 | 4.100 |

| 1,332 | 0.064 | 0.067 | 0.069 | ||||||

| 1,408 | 0.063 | 0.066 | 0.067 | ||||||

The prepared composites’ µ, Δ 0.5, and λ (linear attenuation coefficient, half value layer, and mean free path, respectively) variation as a function of PbO at 121 keV is given in Figure 7. The µ value has an increasing trend with PbO. For example, µ is equal to 0.173 cm−1 at 0 PbO wt%, 0.361 cm−1 at 5 PbO wt%, and 0.552 cm−1 at 10 PbO wt%. Additionally, since both Δ 0.5 and λ have an inverse relationship with µ, both parameters decrease with the addition of PbO. For example, Δ 0.5 is equal to 4.00, 1.92, and 1.26 cm for 0, 5, and 10 PbO wt%. In other words, introducing PbO into pure epoxy leads to an enhancement in µ. This causes a reduction in the thickness that the attenuator needs to have, which can be seen from the Δ 0.5 values.

The fabricated E-PbO composites’ variation in linear attenuation coefficient, half-value thickness, and relaxation length values against the PbO doping concentrations at 121 keV.

The prepared samples’ Δ 0.5 is compared with other previously published epoxy-based composites (Figure 8). Pure epoxy’s half-value layer is the highest out of all the compared composites, closely followed by 6% Al2O3. Meanwhile, E-PbO 5%’s Δ 0.5 is lower than 5% micro WO3 and 6% Fe2O3 (37,38). Finally, E-PbO 10%’s Δ 0.5 is lower than 5% micro Bi2O3 15% Al2O3, 15% Fe2O3, and 10% MgO, but higher than 20%, 30%, and 40% MgO (20,39,40), for instance. These results illustrate that the fabricated epoxy composites are an effective shielding material for radiation-shielding purposes due to their relatively good necessary thickness to attenuate half of the incoming photons.

Half-value thickness comparison between the fabricated composites and previously published composite-based epoxy.

The transmission factor (TF) and radiation protection efficiency (RPE) as an incoming photon energy function are represented in Figure 9. TF and RPE have an opposite trend with energy, as TF increases with increasing energy, while RPE decreases with energy. In other words, at low energies, most of the photons are absorbed by the prepared samples, leading to a small TF, and thus the samples have a good attenuation capability. This is also represented by the RPE being high at low energies. Meanwhile, as energy increases, more photons can penetrate through the samples, leading to increased TF and thus decreased RPE. More specifically, the TF for E-PbO at 59 keV is 58.7% (and RPE is 41.3%) and changes to a TF of 87.8% at 356 keV (or 12.5% RPE). Therefore, epoxy composites are more effective shields in radiation applications with lower energy photons.

The fabricated composites’ transmission factor and RPE.

The TF and RPE of the tested samples are plotted as a function of the PbO concentration at 121 and 661 keV in Figure 10. This figure examines the impact of PbO on both parameters. PbO has a great impact on TF and RPE at 121 keV, which suggests that at low energy, the radiation-shielding ability of the samples can be enhanced by changing their composition. For example, when increasing the PbO concentration from 0% to 10%, the TF at 121 keV decreases from 84.1% to 57.6% (while the RPE increases from 15.9% to 42.4%). At 661 keV, PbO has an improvement in the radiation-shielding properties, although the change in the TF and RPE is smaller.

The TF and RPE for the present composites versus the doping concentration.

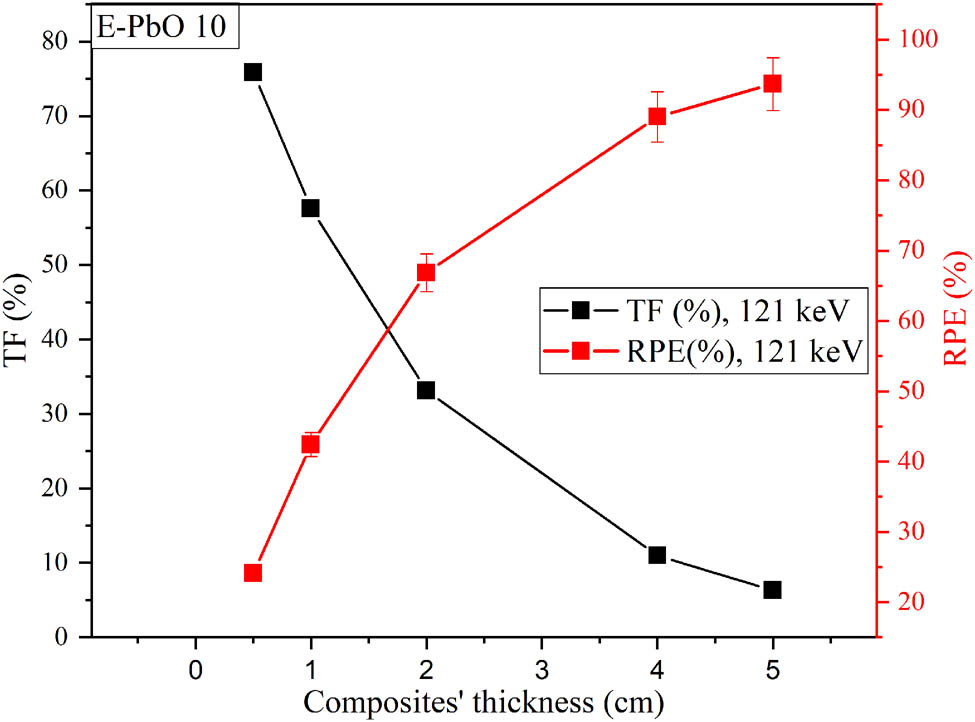

The variation of TF and RPE for the fabricated composites against the composites’ thickness at 121 keV is shown in Figure 11. TF and RPE have opposite trends with thickness. Specifically, TF decreases with increasing thickness, while RPE increases. For example, when the composites’ thickness increases from 0.5 to 5 cm, TF decreases from 75.9% to 6.3%, and RPE increases from 24.1% to 93.7%. At a thickness of 5 cm, the RPE value is almost 100%, meaning that a 5 cm thick sample of the prepared composite attenuates most of the incoming photons. Thus, it is clear that the thickness of the material is also an important factor that must be considered when developing radiation-shielding materials.

The TF and RPE for the fabricated composites versus the composite thickness.

4 Conclusion

The effect of PbO concentration on the epoxide resin’s physical and gamma-ray shielding properties was evaluated. Regarding the fabricated composites’ density, the measurement shows an increase by a factor of ∼8% with increasing incrementation of PbO between 0 and 10 wt%. The light enhancement in the material density was reflected in the fabricated composites’ shielding parameters. The µ simulated values showed a good enhancement in the low γ-photon energy (photoelectric region) where the µ values increased from 0.249 to 0.822 cm−1 with the PbO concentration raised between 0 and 10 wt%, respectively, at the 59 keV gamma photon energy. On the contrary, in the intermediate energy interval (i.e., 662 keV), when the concentration of PbO was raised between 0 and 10 wt%, respectively, the µ values increased by only 10%. The presented data showed a good performance for the fabricated composites at low γ-photon energy, while they have poor shielding for intermediate and high energy. Consequently, there is applicability for the fabricated samples in low γ-ray energy applications.

-

Funding information: The authors express their gratitude to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R57), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contributions: M. I. Sayyed: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft and editing, writing – review and editing; Dalal A. Alorain, Aljawhara H. Almuqrin: project administration, funding acquisition; K. G. Mahmoud: data curation, writing – original draft and editing, writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All the data have been reported in the manuscript. The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The raw data that support the findings are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

(1) Aygün B. High alloyed new stainless steel shielding material for gamma and fast neutron radiation. Nucl Eng Technol. 2020;52:647–53.10.1016/j.net.2019.08.017Search in Google Scholar

(2) Kamislioglu M. Research on the effects of bismuth borate glass system on nuclear radiation shielding parameters. Result Phys. 2021;22:103844.10.1016/j.rinp.2021.103844Search in Google Scholar

(3) Kamislioglu M. An investigation into gamma radiation shielding parameters of the (Al:Si) and (Al + Na):Si-doped international simple glasses (ISG) used in nuclear waste management, deploying Phy-X/PSD and SRIM software. J Mater Sci Mater Electron. 2021;32:12690–704.10.1007/s10854-021-05904-8Search in Google Scholar

(4) Aygün B. Neutron and gamma radiation shielding Ni based new type super alloys development and production by Monte Carlo Simulation technique. Radiat Phys Chem. 2021;188:109630.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2021.109630Search in Google Scholar

(5) Kaewjaeng S, Chanthima N, Thongdang J, Reungsri S, Kothan S, Kaewkhao J. Synthesis and radiation properties of Li2O-BaO-Bi2O3-P2O5 glasses. Mater Today Proc. 2021;43:2544–53.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.04.615Search in Google Scholar

(6) Sayyed MI, El-Mesady IA, Abouhaswa AS, Askin A, Rammah YS. Comprehensive study on the structural, optical, physical and gamma photon shielding features of B2O3-Bi2O3-PbO-TiO2 glasses using WinXCOM and Geant4 code. J Mol Struct. 2019;1197:656–65.10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.07.100Search in Google Scholar

(7) Kumar A, Gaikwad DK, Obaid SS, Tekin HO, Agar O, Sayyed MI. Experimental studies and Monte Carlo simulations on gamma ray shielding competence of (30 + x)PbO-10WO3-10Na2O−10MgO–(40-x)B2O3. Prog Nucl Energy. 2020;119:103047.10.1016/j.pnucene.2019.103047Search in Google Scholar

(8) Tijani SA, Al-Hadeethi Y. The use of isophthalic-bismuth polymer composites as radiation shielding barriers in nuclear medicine. Mater Res Exp. 2019;6:055323. 10.1088/2053-1591/ab0578 Search in Google Scholar

(9) Chanthima N, Kaewkhao J, Limkitjaroenporn P, Tuscharoen S, Kothan S, Tungjai M, et al. Development of BaO–ZnO–B2O3 glasses as a radiation shielding material. Radiat Phys Chem. 2017;137:72–7.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2016.03.015Search in Google Scholar

(10) Alsaif NA, Alotiby M, Hanfi MY, Sayyed MI, Mahmoud KA, Alotaibi BM, et al. A comprehensive study on the optical, mechanical, and radiation shielding properties of the TeO2–Li2O– GeO2 glass system. J Mater Sci Mater Electron. 2021;15226–41. 10.1007/s10854-021-06074-3.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Obaid SS, Sayyed MI, Gaikwad DK, Pawar PP. Attenuation coefficients and exposure buildup factor of some rocks for gamma ray shielding applications. Radiat Phys Chem. 2018;148:86–94.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2018.02.026Search in Google Scholar

(12) Şensoy AT, Gökçe HS. Simulation and optimization of gamma ray linear attenuation coefficients of barite concrete shields. Constr Build Mater. 2020;253:119218.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119218Search in Google Scholar

(13) Zayed AM, Masoud MA, Shahien MG, Gökçe HS, Sakr K, Kansouh WA, et al. Physical, mechanical and radiation attenuation properties of serpentine concrete containing boric acid. Constr Build Mater. 2021;272:121641.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121641Search in Google Scholar

(14) Daungwilailuk T, Yenchai C, Rungjaroenkiti W, Pheinsusom P, Panwisawas C, Pansuk W. Use of barite concrete for radiation shielding against gamma-rays and neutrons. Constr Build Mater. 2022;326:126838.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126838Search in Google Scholar

(15) Almurayshid M, Alsagabi S, Alssalim Y, Alotaibi Z, Almsalam R. Feasibility of polymer-based composite materials as radiation shield. Radiat Phys Chem. 2021;183:109425.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2021.109425Search in Google Scholar

(16) Wang Y, Wang G, Hu T, Wen S, Hu S, Liu L. Enhanced photon shielding efficiency of a flexible and lightweight rare earth/polymer composite: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Nucl Eng Technol. 2021;52(7):1565–70.10.1016/j.net.2019.12.028Search in Google Scholar

(17) Ambika MR, Nagaiah N, Suman SK. Role of bismuth oxide as a reinforcer on gamma shielding ability of unsaturated polyester based polymer composites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2017;134(13):44657.10.1002/app.44657Search in Google Scholar

(18) Aldhuhaibat MJ, Amana MS, Aboud H, Salim AA. Radiation attenuation capacity improvement of various oxides via high density polyethylene composite reinforcement. Ceram Int. 2022;48(17):25011–9.10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.05.154Search in Google Scholar

(19) Al‐Buriahi MS, Eke C, Alomairy S, Yildirim A, Alsaeedy HI, Sriwunkum C. Radiation attenuation properties of some commercial polymers for advanced shielding applications at low energies. Polym Adv Technol. 2021;32(6):2386–96.10.1002/pat.5267Search in Google Scholar

(20) Sayyed MI, Yasmin S, Almousa N, Elsafi M. Shielding properties of epoxy matrix composites reinforced with MgOMicro- and nanoparticles. Materials. 2022;15:6201. 10.3390/ma15186201.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(21) Kim S, Ahn Y, Song SH, Lee D. Tungsten nanoparticle anchoring on boron nitride nanosheet-based polymer nanocomposites for complex radiation shielding. Compos Sci Technol. 2022;221:109353.10.1016/j.compscitech.2022.109353Search in Google Scholar

(22) Aldhuhaibat MJ, Farhan HS, Hassani RH, Tuma HM, Bakhtiar H, Salim AA. Gamma photons attenuation features of PbO-doped borosilicate glasses: a comparative evaluation. Appl Phys A. 2022;128(12):1058.10.1007/s00339-022-06216-2Search in Google Scholar

(23) Amana MS, Aldhuhaibat MJ, Salim AA. Evaluation of the absorption, scattering and overall probability of gamma rays in lead and concrete interactions. SCIOL Biomed. 2021;4:191–9.Search in Google Scholar

(24) Elsad RA, Mahmoud KA, Rammah YS, Abouhaswa AS. Fabrication, structural, optical, and dielectric properties of PVC-PbO nanocomposites, as well as their gamma-ray shielding capability. Radiat Phys Chem. 2021;189:109753.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2021.109753Search in Google Scholar

(25) Bagheri K, Razavi SM, Ahmadi SJ, Kosari M, Abolghasemi H. Thermal resistance, tensile properties, and gamma radiation shielding performance of unsaturated polyester/nanoclay/PbO composites. Radiat Phys Chem. 2018;146:5–10.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2017.12.024Search in Google Scholar

(26) Özdemir T, Güngör A, Akbay IK, Uzun H, Babucçuoglu Y. Nano lead oxide and epdm composite for development of polymer based radiation shielding material: Gamma irradiation and attenuation tests. Radiat Phys Chem. 2018;144:248–55.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2017.08.021Search in Google Scholar

(27) Abouhaswa AS, Sayyed MI, Altowyan AS, Al-Hadeethi Y, Mahmoud KA. Synthesis, structural, optical and radiation shielding features of tungsten trioxides doped borate glasses using Monte Carlo simulation and phy-X program. J Non-Crystalline Solids. 2020;543:120134.10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2020.120134Search in Google Scholar

(28) Demir N, Akar Tarim U, Gurler O. Application of FLUKA code to gamma-ray attenuation, energy deposition and dose calculations. Int J Radiat Res. 2017;15(1):123–8.Search in Google Scholar

(29) Alabsy MT, Elzaher MA. Radiation shielding performance of metal oxides/EPDM rubber composites using Geant4 simulation and computational study. Sci Rep. 2023;13:7744.10.1038/s41598-023-34615-9Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(30) Gili MB, Hila FC. Investigation of gamma-ray shielding features of several clay materials using the EPICS2017 library. Philippine J Sci. 2021;150(5):1017–26.10.56899/150.05.13Search in Google Scholar

(31) Liu Y, Liu B, Gu Y, Wang S, Li M. Gamma radiation shielding property of continuous fiber reinforced epoxy matrix composite containing functional filler using Monte Carlo simulation. Nucl Mater Energy. 2022;33:101246.10.1016/j.nme.2022.101246Search in Google Scholar

(32) Sharma A, Singh B, Sandhu BS. Investigation of photon interaction parameters of polymeric materials using Monte Carlo simulation. Chin J Phys. 2019;60:709–19.10.1016/j.cjph.2019.06.011Search in Google Scholar

(33) More CV, Alavian H, Pawar PP. Evaluation of gamma ray and neutron attenuation capability of thermoplastic polymers. Appl Radiat Isotopes. 2021;176:109884.10.1016/j.apradiso.2021.109884Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(34) X-5 Monte Carlo Team, MCNP — A General Monte Carlo N-Particle Transport Code, Version 5, La-Ur-03-1987. II; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

(35) Sayyed MI, Zaid MH, Effendy N, Matori KA, Lacomme E, Mahmoud KA, et al. The influence of PbO and Bi2O3 on the radiation shielding and elastic features for different glasses. J Mater Res Technol. 2020;9(4):8429–84381.10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.05.113Search in Google Scholar

(36) Naseer KA, Marimuthu K, Mahmoud KA, Sayyed MI. The concentration impact of Yb3 + on the bismuth boro-phosphate glasses: Physical, structural, optical, elastic, and radiation-shielding properties. Radiat Phys Chem. 2021;188:109617.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2021.109617Search in Google Scholar

(37) Hannachi E, Mahmoud KA, Sayyed MI, Slimani Y. Effect of sintering conditions on the radiation shielding characteristics of YBCO superconducting ceramics. J Phys Chem Solids. 2022;164:110627.10.1016/j.jpcs.2022.110627Search in Google Scholar

(38) Sakar E, Özgür F, Bünyamin A, Sayyed MI, Murat K. Phy-X/PSD: Development of a user friendly online software for calculation of parameters relevant to radiation shielding and dosimetry. Radiat Phys Chem. 2020;166:108496.10.1016/j.radphyschem.2019.108496Search in Google Scholar

(39) Karabul Y, İçelli O. The assessment of usage of epoxy based micro and nano-structured composites enriched with Bi2O3 and WO3 particles for radiation shielding. Res Phys. 2021;26:104423. 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104423.Search in Google Scholar

(40) Aldhuhaibat MJR, Amana MS, Jubier NJ, Salim AA. Improved gamma radiation shielding traits of epoxy composites: Evaluation of mass attenuation coefficient, effective atomic and electron number. Radiat Phys Chem. 2021;179:109183. 10.1016/j.radphyschem.2020.109183.Search in Google Scholar

© 2023 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Chitosan nanocomposite film incorporating Nigella sativa oil, Azadirachta indica leaves’ extract, and silver nanoparticles

- Effect of Zr-doped CaCu3Ti3.95Zr0.05O12 ceramic on the microstructure, dielectric properties, and electric field distribution of the LDPE composites

- Effects of dry heating, acetylation, and acid pre-treatments on modification of potato starch with octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA)

- Loading conditions impact on the compression fatigue behavior of filled styrene butadiene rubber

- Characterization and compatibility of bio-based PA56/PET

- Study on the aging of three typical rubber materials under high- and low-temperature cyclic environment

- Numerical simulation and experimental research of electrospun polyacrylonitrile Taylor cone based on multiphysics coupling

- Experimental investigation of properties and aging behavior of pineapple and sisal leaf hybrid fiber-reinforced polymer composites

- Influence of temperature distribution on the foaming quality of foamed polypropylene composites

- Enzyme-catalyzed synthesis of 4-methylcatechol oligomer and preliminary evaluations as stabilizing agent in polypropylene

- Molecular dynamics simulation of the effect of the thermal and mechanical properties of addition liquid silicone rubber modified by carbon nanotubes with different radii

- Incorporation of poly(3-acrylamidopropyl trimethylammonium chloride-co-acrylic acid) branches for good sizing properties and easy desizing from sized cotton warps

- Effect of matrix composition on properties of polyamide 66/polyamide 6I-6T composites with high content of continuous glass fiber for optimizing surface performance

- Preparation and properties of epoxy-modified thermosetting phenolic fiber

- Thermal decomposition reaction kinetics and storage life prediction of polyacrylate pressure-sensitive adhesive

- Effect of different proportions of CNTs/Fe3O4 hybrid filler on the morphological, electrical and electromagnetic interference shielding properties of poly(lactic acid) nanocomposites

- Doping silver nanoparticles into reverse osmosis membranes for antibacterial properties

- Melt-blended PLA/curcumin-cross-linked polyurethane film for enhanced UV-shielding ability

- The affinity of bentonite and WO3 nanoparticles toward epoxy resin polymer for radiation shielding

- Prolonged action fertilizer encapsulated by CMC/humic acid

- Preparation and experimental estimation of radiation shielding properties of novel epoxy reinforced with Sb2O3 and PbO

- Fabrication of polylactic acid nanofibrous yarns for piezoelectric fabrics

- Copper phenyl phosphonate for epoxy resin and cyanate ester copolymer with improved flame retardancy and thermal properties

- Synergistic effect of thermal oxygen and UV aging on natural rubber

- Effect of zinc oxide suspension on the overall filler content of the PLA/ZnO composites and cPLA/ZnO composites

- The role of natural hybrid nanobentonite/nanocellulose in enhancing the water resistance properties of the biodegradable thermoplastic starch

- Performance optimization of geopolymer mortar blending in nano-SiO2 and PVA fiber based on set pair analysis

- Preparation of (La + Nb)-co-doped TiO2 and its polyvinylidene difluoride composites with high dielectric constants

- Effect of matrix composition on the performance of calcium carbonate filled poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composites

- Low-temperature self-healing polyurethane adhesives via dual synergetic crosslinking strategy

- Leucaena leucocephala oil-based poly malate-amide nanocomposite coating material for anticorrosive applications

- Preparation and properties of modified ammonium polyphosphate synergistic with tris(2-hydroxyethyl) isocynurate for flame-retardant LDPE

- Thermal response of double network hydrogels with varied composition

- The effect of coated calcium carbonate using stearic acid on the recovered carbon black masterbatch in low-density polyethylene composites

- Investigation of MXene-modified agar/polyurethane hydrogel elastomeric repair materials with tunable water absorption

- Damping performance analysis of carbon black/lead magnesium niobite/epoxy resin composites

- Molecular dynamics simulations of dihydroxylammonium 5,5′-bistetrazole-1,1′-diolate (TKX-50) and TKX-50-based PBXs with four energetic binders

- Preparation and characterization of sisal fibre reinforced sodium alginate gum composites for non-structural engineering applications

- Study on by-products synthesis of powder coating polyester resin catalyzed by organotin

- Ab initio molecular dynamics of insulating paper: Mechanism of insulating paper cellobiose cracking at transient high temperature

- Effect of different tin neodecanoate and calcium–zinc heat stabilizers on the thermal stability of PVC

- High-strength polyvinyl alcohol-based hydrogel by vermiculite and lignocellulosic nanofibrils for electronic sensing

- Impacts of micro-size PbO on the gamma-ray shielding performance of polyepoxide resin

- Influence of the molecular structure of phenylamine antioxidants on anti-migration and anti-aging behavior of high-performance nitrile rubber composites

- Fiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel via in situ fiber formation

- Preparation and performance of homogenous braids-reinforced poly (p-phenylene terephthamide) hollow fiber membranes

- Synthesis of cadmium(ii) ion-imprinted composite membrane with a pyridine functional monomer and characterization of its adsorption performance

- Impact of WO3 and BaO nanoparticles on the radiation shielding characteristics of polydimethylsiloxane composites

- Comprehensive study of the radiation shielding feature of polyester polymers impregnated with iron filings

- Preparation and characterization of polymeric cross-linked hydrogel patch for topical delivery of gentamicin

- Mechanical properties of rCB-pigment masterbatch in rLDPE: The effect of processing aids and water absorption test

- Pineapple fruit residue-based nanofibre composites: Preparation and characterizations

- Effect of natural Indocalamus leaf addition on the mechanical properties of epoxy and epoxy-carbon fiber composites

- Utilization of biosilica for energy-saving tire compounds: Enhancing performance and efficiency

- Effect of capillary arrays on the profile of multi-layer micro-capillary films

- A numerical study on thermal bonding with preheating technique for polypropylene microfluidic device

- Development of modified h-BN/UPE resin for insulation varnish applications

- High strength, anti-static, thermal conductive glass fiber/epoxy composites for medical devices: A strategy of modifying fibers with functionalized carbon nanotubes

- Effects of mechanical recycling on the properties of glass fiber–reinforced polyamide 66 composites in automotive components

- Bentonite/hydroxyethylcellulose as eco-dielectrics with potential utilization in energy storage

- Study on wall-slipping mechanism of nano-injection polymer under the constant temperature fields

- Synthesis of low-VOC unsaturated polyester coatings for electrical insulation

- Enhanced apoptotic activity of Pluronic F127 polymer-encapsulated chlorogenic acid nanoparticles through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in liver cancer cells and in vivo toxicity studies in zebrafish

- Preparation and performance of silicone-modified 3D printing photosensitive materials

- A novel fabrication method of slippery lubricant-infused porous surface by thiol-ene click chemistry reaction for anti-fouling and anti-corrosion applications

- Development of polymeric IPN hydrogels by free radical polymerization technique for extended release of letrozole: Characterization and toxicity evaluation

- Tribological characterization of sponge gourd outer skin fiber-reinforced epoxy composite with Tamarindus indica seed filler addition using the Box–Behnken method

- Stereocomplex PLLA–PBAT copolymer and its composites with multi-walled carbon nanotubes for electrostatic dissipative application

- Enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of Krestin–chitosan nanocomplex for cancer medication via activation of the mitochondrial intrinsic pathway

- Variation in tungsten(vi) oxide particle size for enhancing the radiation shielding ability of silicone rubber composites

- Damage accumulation and failure mechanism of glass/epoxy composite laminates subjected to repeated low velocity impacts

- Gamma-ray shielding analysis using the experimental measurements for copper(ii) sulfate-doped polyepoxide resins

- Numerical simulation into influence of airflow channel quantities on melt-blowing airflow field in processing of polymer fiber

- Cellulose acetate oleate-reinforced poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) composite materials

- Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

- Recyclable polytriazole resins with high performance based on Diels-Alder dynamic covalent crosslinking

- Adsorption and recovery of Cr(vi) from wastewater by Chitosan–Urushiol composite nanofiber membrane

- Comprehensive performance evaluation based on electromagnetic shielding properties of the weft-knitted fabrics made by stainless steel/cotton blended yarn

- Review Articles

- Preparation and application of natural protein polymer-based Pickering emulsions

- Wood-derived high-performance cellulose structural materials

- Flammability properties of polymers and polymer composites combined with ionic liquids

- Polymer-based nanocarriers for biomedical and environmental applications

- A review on semi-crystalline polymer bead foams from stirring autoclave: Processing and properties

- Rapid Communication

- Preparation and characterization of magnetic microgels with linear thermosensitivity over a wide temperature range

- Special Issue: Biodegradable and bio-based polymers: Green approaches (Guest Editors: Kumaran Subramanian, A. Wilson Santhosh Kumar, and Venkatajothi Ramarao)

- Synthesis and characterization of proton-conducting membranes based on bacterial cellulose and human nail keratin

- Fatigue behaviour of Kevlar/carbon/basalt fibre-reinforced SiC nanofiller particulate hybrid epoxy composite

- Effect of citric acid on thermal, phase morphological, and mechanical properties of poly(l-lactide)-b-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(l-lactide)/thermoplastic starch blends

- Dose-dependent cytotoxicity against lung cancer cells via green synthesized ZnFe2O4/cellulose nanocomposites