Abstract

The clothing industry is often perceived, particularly in the European context, as a declining, traditional, labour-intensive industry. Nonetheless, in recent years in Poland, after over three decades of steady shrinkage, though the average scale of operations has continued to decline, the number of firms in the sector has been much more stable. In their analysis of the locations of apparel producers on the national level, the authors point to the changing geography of the sector in terms of its increased or diminishing relative presence in some areas. The links between location tendencies among firms in the clothing industry and other fashion-related institutions and initiatives are noted, as are new firms in the creative sector. The spatial patterns observed point to the ability of the resized sector to leverage emerging market opportunities and upgrade selectively, and to its broader evolution from a traditional towards a creative industry.

1 Introduction

The design, production, and consumption of clothing and apparel is a complex economic, technological, social, and cultural phenomenon [1,2,3]. The broadly defined fashion industry [4] may be divided into four main levels: textile production (including mills and yarn makers), design and manufacturing (designers, manufacturers, and wholesalers), retail (all types of stores and points of distribution and sale), and ancillary services which connect each of the other levels (advertising, the specialist press, research agencies, and fashion consultants and commentators as the arbiters of taste). Aside from fashion designers and the institutions involved in prototyping, design, and fashion production (and repair), and the institutions and firms that provide support and promotion to the sector, as well as wholesale and retail, the industry also includes temporary events and initiatives (such as fashion weeks, B2B fairs or independent fashion fairs) [5], educational institutions (fashion schools) [6], and other organizations. Hence, for instance, to reflect the complexity of the fashion sector from a statistical perspective on the EU-27 level and take into account the blurred boundaries between design, production, distribution, and retail,[1] the European Commission, in its report [7], proposes the term “textile ecosystem.” This includes seven main subsectors: intermediate products for textiles (fibres, yarns, and fabrics), intermediate products for leather and fur goods, (tanned and dressed leather and fur) textiles (home textiles including carpets and rugs, and technical and industrial textiles), clothing and accessories (including workwear), leather and fur finished products including footwear, and distribution – wholesale and retail. Although the leading positions in almost all the subfields across this ecosystem are held by Italy, Germany, France, and Spain, which are home to the largest number of enterprises and rank highest in terms of volume and turnover, a significant share of firms representing the sector are located in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), in particular if they conduct labour-intensive activities [8].

On the one hand, if only the volume, scale of production, and employment levels are taken into account, in recent decades, fashion, in particular production of textile and apparel, has often been perceived as a declining, labour-intensive, traditional sector, especially in the European context [9,10,11,12], due to offshoring and changes in the global value chains privileging Asian, in particular East Asian countries. On the other hand, in certain European countries (e.g. Italy, Poland, or Romania), it still employs a significant number of people [7] and is important in terms of the perception of brands and their country, region, or city of origin [13]. It does also implement technological, organizational, and design-related innovations [14,15,16], with Europe considered a “key innovator for the textile ecosystem worldwide” [8, p. 10]. At the same time, due to the growing importance of the symbolic, aesthetic, and creative content of clothing understood as fashion, it is included in most definitions of the cultural and creative industries (in the original department for culture, media and sport model, the “symbolic texts model,” as “borderline cultural industries”; in the concentric circle model in the outer most circle as so-called “related industries”; and in the world intellectual property organization model as a “partial copyright industry”) [17, p. 19].

This evolution from a traditional to a creative sector may also be considered as part of and a reflection of the upgrading processes taking place in the sector in some geographic locations [9,18,19,20]. Upgrading is usually understood as the trajectory of firms, regions, or countries from lower to higher value-added activities [21] or their achievement of a better position in global value chains [4,22,23]. Different types of upgrading are distinguished, linked with the extent and character of participation in core value chain stages such as headquarters and R&D (including design), manufacturing, marketing, logistics, and distribution. Upgrading may involve changes in production processes (e.g. an increase in the complexity of production activities, from assembly or a focus on a certain production stage to a broader range of production activities; an increase in the efficiency of technological processes; or the introduction of new technologies). It may also affect the characteristics and nature of produced goods (e.g. a shift towards higher quality or more sophisticated and complex products, introduction of new products, or a switch to more upscale product lines or products aimed at new market segments). It may also be related to functional changes in companies’ involvement in value chains (e.g. expansion or a change in focus to more knowledge-intensive and sophisticated value chain stages – higher value functions beyond manufacturing, such as input sourcing, product development, design, or branding) in order to exploit the stages of the commodity chain where most value is captured [24]. Upgrading can therefore lead to a change in the structure of production, including increased complexity of production and intra-sectoral upgrading involving forward and backward linkages in the supply chain, and a move away from labour-intensive to more capital- and skill-intensive economic activities [12]. It may also consist in venturing into related markets (e.g. from sewing of apparel to production of fabric goods for the automotive industry). Managerial upgrading, construed as improving the efficiency and effectiveness of a firm’s activities by implementing new organizational forms and methods, is likewise sometimes included in the list of upgrading types [25]. Aside from upgrading at the company level, cluster upgrading and path upgrading are also distinguished [26]. A range of resources can be used for upgrading. For instance, Aspers [19] recognized moving (or returning) into the design phase of the value chain as a form of using contextual knowledge for upgrading, and noticed that this may not necessitate location in typical industrial districts, but may take place in complex cooperation networks within a broader region or in major urban centres.

Moreover, in recent decades, the debate on upgrading has evolved to include a more nuanced understanding of this concept, and more critical stances on it [25,26]. First, it has been recognized that upgrading is not always a linear, voluntary, or pro-active process. It is not necessarily a choice, but is often undertaken under pressure as a defensive, survival strategy in response to changes in the business environment or shocks and unanticipated events on the national, continental, or global level [21]. Second, it may be characterized by uneven and complex dynamics at different spatial scales (e.g. within a country, region, or company). For instance, within a single firm, the survival or development strategy may involve selective upgrading in parallel with continuing cooperation with long-term suppliers and buyers along an earlier, lower value-added development path, or even downgrading (e.g. a firm develops its own brand while continuing to function as a subcontractor [outward processing traffic, OPT], resulting in the same manufacturer producing lower- and higher-quality, luxury products) [25,27]. Upgrading strategies may vary depending on the market sector, segment, and business size [22,23]. Moving into branding and retailing is a promising but also challenging choice. Sometimes upgrading requires external capital. In that sense, it opens the company up to the influence of capital markets [25]. Finally, the benefits of upgrading are neither evenly distributed nor certain. For instance, upgrading may translate into an improvement in some employees’ situation (better working conditions and wage increases understood as social upgrading) but at the same time cause employment cuts and downsizing, or even the disappearance of some firms. Upgrading may not lead to the capturing (redistribution) of rewards from buyers to manufacturers; the outcomes can be limited to a redistribution of costs and risks to suppliers. While upgrading within production (e.g. increasing the productivity, flexibility, or quality of production) may be welcomed, encouraged, or demanded by buyers, functional upgrading – moving to higher value-added activities such as design, branding, or retailing – may be unwelcome as an encroachment on the core competencies of buyers. Hence it is important to recognize the complex nature and multiscalar contexts in analysing up- and downgrading experiences [21].

Firms may approach upgrading in diverse ways [24]. Clothing enterprises may integrate horizontally into related fashion sectors (e.g. shoes or accessories). They may integrate backward into design and the coordination of the supply chain, or forward into coordination and control of distribution and retail. For instance, in the Northern Italian context, Dunford [24] identified three types of clothing enterprises: (a) firms which are directly involved in the design and prototyping phase as well as the marketing and distribution phase but outsource production to other enterprises; this allows them to employ a relatively small number of skilled staff at the initial phase and semi-final phase of the value chain and achieve a high turnover per employee; (b) firms involved in manufacturing either as subcontractors or co-contractors; (c) vertically integrated enterprises that are directly involved in all the stages of the value chain including having their own distribution structures. Some of these latter are rooted in high fashion and luxury ready-to-wear production, which can also include small-scale artisanal or bespoke production. The up- and downgrading experiences may be conditioned by local knowledge and skills, capital and ownership structures, the size of the domestic market, and external policies at the continental level (e.g. European integration) and globalization (e.g. trade agreements). Some authors also point to longer-term challenges attendant on upgrading. For instance, in the case of the clothing industry, there is a danger that relocating manufacturing and retaining the design phase, thus continuing to determine both the functional properties and symbolic context of the clothing, and the distribution phase, may bring benefits in the short term, but in the long run result in the loss of production competencies and in time, compromise the ability to design successful products [19].

The geographical dimension and impact of upgrading are also of significance. It may entail relocation of lower-value-added activities, above all manufacturing, first within countries to poorer, less developed regions, then to neighbouring states or other countries within a continent, and ultimately to more distant regions of the world. This process has been observed in the clothing industry in Western European countries over the last five decades, and intensified in the early years of the new millennium, becoming visible in other parts of the continent as well. The production fashionscape has changed drastically. Larger-scale manufacturing has almost disappeared. What is left are either micro and small enterprises or large retailers focused on value enhancement and capturing selected value-chain stages [24]. Moreover, it has been noticed that some functions connected with upgrading (control, design) tend to be concentrated in a few locations – major cities in certain countries [28]. As illustrated by the case of Milan [24], today’s major fashion capitals are therefore not necessarily major clothing manufacturing centres. Milan’s status as the centre of the textile and clothing industry is determined by other factors, such as its dominant position in international networks, the high concentration of services connected with the intangible and knowledge-related aspects of the fashion system, a large number of major firm and brand headquarters, and a high proportion of the higher-paid jobs in the fashion sector. In the Italian context, the city has the largest concentration of designers and stylists not directly employed by textile and clothing companies, and is the most important centre for fashion-related trade fairs and publishing.

While including fashion as part of the creative sector, geographers likewise point to the fact that it is both (at least potentially) global in terms of market range and value chain and local in terms of potential creative inspirations, and continues to be spatially clustered [29,30,31]. Fashion-related phenomena pertain to different spatial scales and diverse relations in space [32,33]. The role of space is important not only in terms of access to the supplies or labour necessary for fashion design and production, or access to potential fashion consumers, but also for the creation of intangible value in fashion and decoding its meanings [20,30,34,35,36,37] and conversely the fashion sector plays the role in labelling, dividing, and sorting hierarchies of spaces [38], for instance, in fashion cities [39]. In a given geographical context, the importance and visibility of certain aspects of the fashion value chain may also change over time. In recognition of this fact, Casadei et al. [40] distinguished three different ideal urban types: manufacturing, design, and symbolic fashion cities. The last mentioned category reflects the fact that for many large cities, fashion has become an important facet of the symbolic, tourist, and experience economy [41].

Therefore, in addition to analysis of global value chains connected with the clothing industry, including the limited nearshoring and reshoring processes visible in Europe in the last few decades [11,28,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], a less clear issue, but one equally important to explore, is the spatial transformation of the domestic fashion industry in certain European countries, the foundations of that transformation, how it is related to upgrading processes, and its implications for particular cities and regions.

2 CEE context of clothing industry transformations

Several authors have stressed that the fashion sector should be researched in various geographical contexts beyond those of the leading fashion countries, regions, or cities [48,49], including in more peripheral or semi-peripheral locations (in respect of both location and socio-economic development). According to the Euratex report [7], with 11% share of total employment in the EU-27 fashion sector, Poland comes second only to Italy, with a similar market share to Romania. It is sixth in terms of fashion turnover (4%) and seventh in terms of exports (3%), though unfortunately it is not among the top five EU-27 countries in terms of investments or innovations in the sector.

The situation of the Polish apparel sector and its transformation is shaped by global and continental factors as well as its specific CEE and national considerations. On the global and continental level, important developments over the last three decades, shaping the circumstances surrounding the transformation of the clothing industry and its (potential) upgrading, have included European integration processes and the accession of successive CEE countries to the EU, the phasing out of the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing in 2005, the global economic crisis at the turn of the first and second decades of the new millennium, and finally the recent Covid-19 pandemic and the outbreak of the armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine.

As the largest country in the CEE region, Poland seems to be a particularly interesting national context to study, as in this case, the broader fundamental processes of change in the European textile and clothing industry observed in recent decades overlap with the profound processes of socio-economic transformation which have impacted all aspects of the country’s economy, including both production and consumption of clothing. Poland entered the era of globalization, production offshoring, and fast fashion belatedly, but once it did so, the extent to which it embraced the new trends was very considerable. This delay was a function not only of its semi-peripheral status within the continent and lower level of socio-economic development, translating into lower disposable incomes, but also of the much longer lasting and deep-rooted traditional clothing production and consumption patterns (in terms of location, technology, acquisition and disposal of clothing, etc.) in the CEE region compared to Western Europe. On the eve of its political and economic transformations, its fashion sector was therefore a unique melange of large, state-owned textile and clothing enterprises (of various sizes, but dominated by large and very large factories), cooperatives, and a patchwork of formal and informal micro-initiatives linked with fashion production which enabled Polish consumers to deal with the permanent shortages of consumption goods typical for a centrally planned economy, while striving to both meet basic clothing needs and be fashionable [50]. Although the sector has suffered visible, ongoing shrinkage in terms of volume of production and employment since as long ago as the mid-1970s, as mentioned earlier, it has not disappeared completely. In fact, in the last decade, this decline has slowed significantly, and this makes it worthwhile to look at the location and functioning of this resized sector [48,51]. Moreover, the resilience demonstrated by the industry – its survival and growth strategies – may be linked to selective upgrading and evolution towards the creative sector, among both of a few larger Polish fashion brands with international ambitions which have mainly offshored production but retained key controlling and creative functions in their country of origin [27] and smaller Polish clothing firms which are exploiting new trends in the fashion market [48].

As is visible in the case of Poland, the former communist countries of the CEE region are partly repeating clothing industry transformation (and shrinkage) patterns observed in Western Europe, though these developments are to a certain degree unique, as they are also strongly conditioned by the specific regional and post-communist context. As already mentioned, the transformations of the clothing sector (and light industry more broadly) in CEE started much later than those observed in Western Europe, but then speeded up following the reintroduction of the market economy and deeper involvement (and impact) of global value chains coupled with important changes contingent on the socio-political transformations. These included significant changes in companies’ ownership, management, demographic, migration, and consumption patterns. Moreover, many of the CEE developments in the clothing industry and other, related industries (e.g. footwear) are seen as path-dependent, i.e. caused by a chain of past events which have resulted in a specific development trajectory that might be strengthened by externalities and agglomeration effects as well as institutional self-reproducing features (hysteresis) [22,23]. Researchers of transformations in CEE light industry therefore stress that, in addition to global and European trade policies, the legacy of the communist past, including existing social networks and industrial fabric, still affects the sector’s development paths and perspectives. Yoruk [27], for instance, remarked that while apparel production in Romania was relatively consolidated, company structure in Poland even during communism was much more dispersed, leading to potentially different privatization and upgrading processes.

Pickles and Smith [12] observed both processes of delocalization and resilience in CEE – the latter was understood as the ability to continue clothing production and upgrade despite shrinkage. They pointed to the fact that in CEE countries, this may be linked not only (or no longer) to competing on wage levels or production costs but most of all to geographic proximity, skills, and flexibility, giving benefits including lean retailing. Other authors also stress that as CEE countries are in an intermediary position between developed and developing countries in terms of production costs and sector specific traditions, shrinkage of production in various sectors of the fashion industry such as clothing and footwear is accompanied by structural changes and spatial changes [22,23].

The above-mentioned change processes will now be discussed with respect to the experiences of individual countries in CEE. Romania remains an important European clothing manufacturer, but the past two decades have witnessed a decline in exports and employment in the sector, leading to company closures and consolidations, functional upgrading, and turning to domestic and non-traditional markets [21]. Romanian firms play a variety of roles and pursue a variety of strategies simultaneously [12,21,25]. These comprise upgrading to higher-value products produced in smaller volumes, improving their position in value chains by including design, and relocating to poorer regions within the country or offshoring to neighbouring non-EU countries such as Ukraine. At the same time, Romania still functions as a nearshoring option, for instance, for higher-value-added apparel for Italian firms [19].

In Slovakia [28,44], the first decade of political and economic transformation saw a growing reliance on exports to Western Europe. After EU enlargement, the change in the conditions of trade and wage pressure led to a visible shrinkage in employment and an eastward regional shift to less developed regions of the country. Greater economic sustainability was observed among firms with foreign ownership and/or more deeply involved in Western European production networks and corporate structures, or those producing higher-value-added products. Production upgrading by offshoring to Ukraine and neighbouring EU countries with lower labour costs such as Romania and Bulgaria, the introduction of technological innovations (e.g. digital technologies), and a focus on more flexible production of higher-quality products were other visible adjustments. The latter change included product upgrading to technical clothing, original design, smaller scale, or bespoke fashion production. An east-west divide within the country is visible in this respect. More sophisticated, luxury production on a smaller scale has developed mainly in Bratislava and overlaps with the concentration of creative industries in the Slovak capital [52] (upgrading by focusing on design, manufacturing and retail of own brands, and functional clothing). More traditional production involving process and product upgrading takes place in more peripheral regions in the eastern part of the country (production of high-quality menswear and hosiery, more flexible production, and the commissioning of new, less labour-intensive machinery). In some cases, a switch to production for the automotive sector has also been observed. Pastor and Belvončikova [28] therefore see the future of the Slovak clothing industry in further specialization with respect to technical clothing, for instance, leisure and sports garments, or upscale and luxury segments, including expanding the production of women’s accessories. Vanishing production from some peripheral rural areas was nonetheless noted as a significant challenge, alongside the ambiguous impact of upgrading on the sector (e.g. improvements to the situation of workers, such as rising wages, presented the sector with new challenges in respect of competitiveness).

Until the outbreak of the Russian–Ukrainian war, Ukraine had not only been drawing on its clothing industry traditions (as a major supplier of clothing and apparel to Soviet consumers in Soviet Union times) and developing into a major nearshore option for European countries, including CEE countries such as Poland or Romania, but also as a competitor to them in attracting German or other Western European offshoring [53]. In the years before the pandemic, both employment and wages in the sector displayed an upward tendency. Even before the war, however, its clothing sector was also reported to face numerous development problems, such as insufficient domestic demand due to dominance of foreign (in particular East Asian, Turkish, and Polish) and second-hand imports, and lack of sufficient investment, government support, and regulation. Unlike in Romania and Hungary, where clothing production displayed a clear tendency to relocate or remain in less developed, poorer regions, in Ukraine, the largest share of enterprises in the apparel industry was associated with a range of regions with diverse per capita GDP and located in different parts of the country, from the Kyiv and Kharkiv regions to Lviv, Khmelnitsky, and the Odessa region.

Earlier studies of the broader fashion industry in CEE focusing on footwear production can likewise be used as a point of reference. For instance, in Hungarian footwear production, integration into global production networks by businesses taking on the roles of subcontractors and subsidiaries of foreign enterprises in the first decades of transformation was followed by shrinkage in employment, coupled with process and functional upgrading within existing value chains and small-scale developments with respect to companies’ own brands, in particular more artisanal and premium production [22,23]. As in the case of the clothing industry in Romania, developments in the capital, Budapest, differ from those in peripheral parts of the country. A greater decline in employment; disappearance of large production facilities; development of small enterprises focused on niche, luxury production; exploration of niche domestic markets; and to some extent benefiting from tourist demands are characteristics that have been observed in the capital. In the less developed southern and eastern parts of Hungary, continuation, and process or product upgrading are more common (e.g. ongoing subcontracting for the German market, and downsized but surviving larger production facilities). Coexistence or branching out into other industries where similar skills and related products are needed (in particular the automotive industry) has also been noticed. It has been pointed out, however, that domestic manufacturing locations can be considered as alternatives to offshoring only in respect of their higher value added and for specialist products for which local knowledge and skills are important. Drawing on the latter, moreover, has become a growing challenge due to the ageing and shrinking population of light industry workers.

Finally, the apparel and footwear industries in different CEE countries may be at different phases of development. With regard to footwear production, for instance, at the end of the 2000s, significant differences were noticed between Poland and Bulgaria [54]. Subcontracting happened much earlier in Poland (in the early to mid-1990s) than in Bulgaria (late 1990s). Bulgarian firms were found to be more dependent on export than Polish ones. The latter benefited from a much larger domestic market and showed a greater readiness to invest in higher-value-added activities (own brands, marketing, and sales networks) [54]. Similarly, earlier studies of upgrading in Polish clothing firms considered the process more effective in this population than in Romania due to these companies’ closer links with foreign buyers as original equipment manufacturers (OEM), and the development of own brand nurturing already in the early 2000s [27]. One reason for this may have been the diversity of industrial structures inherited from communism.

Despite the dynamic changes in the broader fashion ecosystem in Poland in the past few decades, recent studies on the Polish clothing industry have tended to focus mainly on production volumes, national competitiveness, international trade [55,56,57,58], or general trends [47], to some extent neglecting the internal spatial dynamics of the sector and the factors behind its transformation, as already noticed some years ago by Pickles and Smith [12, p. 182], who called for a more nuanced analysis of “actually existing trajectories of adjustment.” There are few up-to-date publications [50,51,57,58,59] which consider the issue from a national level perspective and discuss the changing geography of clothing production within Poland. This may be partly due to the broader issue of the geography of fashion being an under-studied and rather neglected research field both in Poland and in the wider CEE [5].

3 Research aim, materials, and methods

The aim of the present study is therefore to offer new interpretations of the spatial reconfiguration and adaptation processes in the downsized clothing and apparel sector in Poland in the context of current trends and factors in its shrinkage and reorganization [12,15,28,44,60,61].

As the primary, narrower understanding of the fashion industry considers it “the business of making clothes” [38, p. 290], in this article, we will focus on national-level data with respect to clothing production, in particular the number and location of firms in the sector,[2] keeping in mind that this will provide an overview only of a selected part of the more broadly defined “textile ecosystem” [8]. References to the textile sector will also be made, as background information. Moreover, as already underlined, existing, more recent publications on the Polish fashion industry tend to focus on global value chains, consumer behaviour, and case studies of selected firms or general issues [47,61,62,63,64], and do not usually include in-depth consideration of the spatial distribution of clothing firms within the country.

In order to identify trends in and rationales behind current clothing production locations in Poland, the authors posed the following research questions:

What trends may be observed in numbers and sizes of firms in the clothing industry in Poland in recent decades?

Where are the firms in the clothing industry in Poland currently located? What trends in changes in the geography of clothing production in Poland have been visible in the last decade?

What are the key factors behind the on-going (spatial) transformation of the clothing industry in Poland? How is it linked to selective upgrading?

Following a review of the relevant scientific literature and existing reports on the European [7,8], CEE [11,12,21,22,23,27,28,42,44,47, 53,54,60,65,66], and Polish levels [47,50,51,55,56,57,58,59,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70], the authors used two main sources of information. First, they acquired and analysed detailed statistical data on the number and locations of the total population of firms in the textile and clothing sector in Poland (REGON, NACE sections 13 and 14, Statistics Poland [SP] data) focusing on the 2013–2023 period.[3] Using measures of spatial concentration (location quotient, LQ), industry cluster areas were identified for 2013 and 2023, and changes between these periods were analysed. In addition, changes in the period 2013–2019 in comparison to 2019–2023 were examined to check for the potential impact of the pandemic and the Russian–Ukrainian war. Additional data on new clothing firms established in 2013–2023 were also consulted. The authors then cross-checked these data using information on employment in the largest firms in the clothing production sector, and clothing design and retail (owners of leading domestic fashion brands)[4] obtained from company reports for 2018 (Polish Company Register/National Court Register – KRS reports). Current locations of Polish clothing industry businesses were then compared with information on the locations of the headquarters of the main employers in the sector in 1980 (i.e. a few years after the industry reached its highest level of employment, in 1976) (SP data).

They also made use of the publicly available general SP data on manufacturing and newly registered firms in the creative sector (2013–2019), as well as data on the locations of independent B2C (business to client) fashion fairs organized in Poland in 2019 [5]. The interpretation of the changes in the spatial pattern of these firms and the strengthening of certain more visible clusters of clothing production was enriched by the authors’ participation in other, more qualitatively oriented research endeavours such as interviews and participant observation within the framework of a broader project on fashion in Poland [73].

4 Research results and their discussion

4.1 Size, dynamics, and structure of the sector

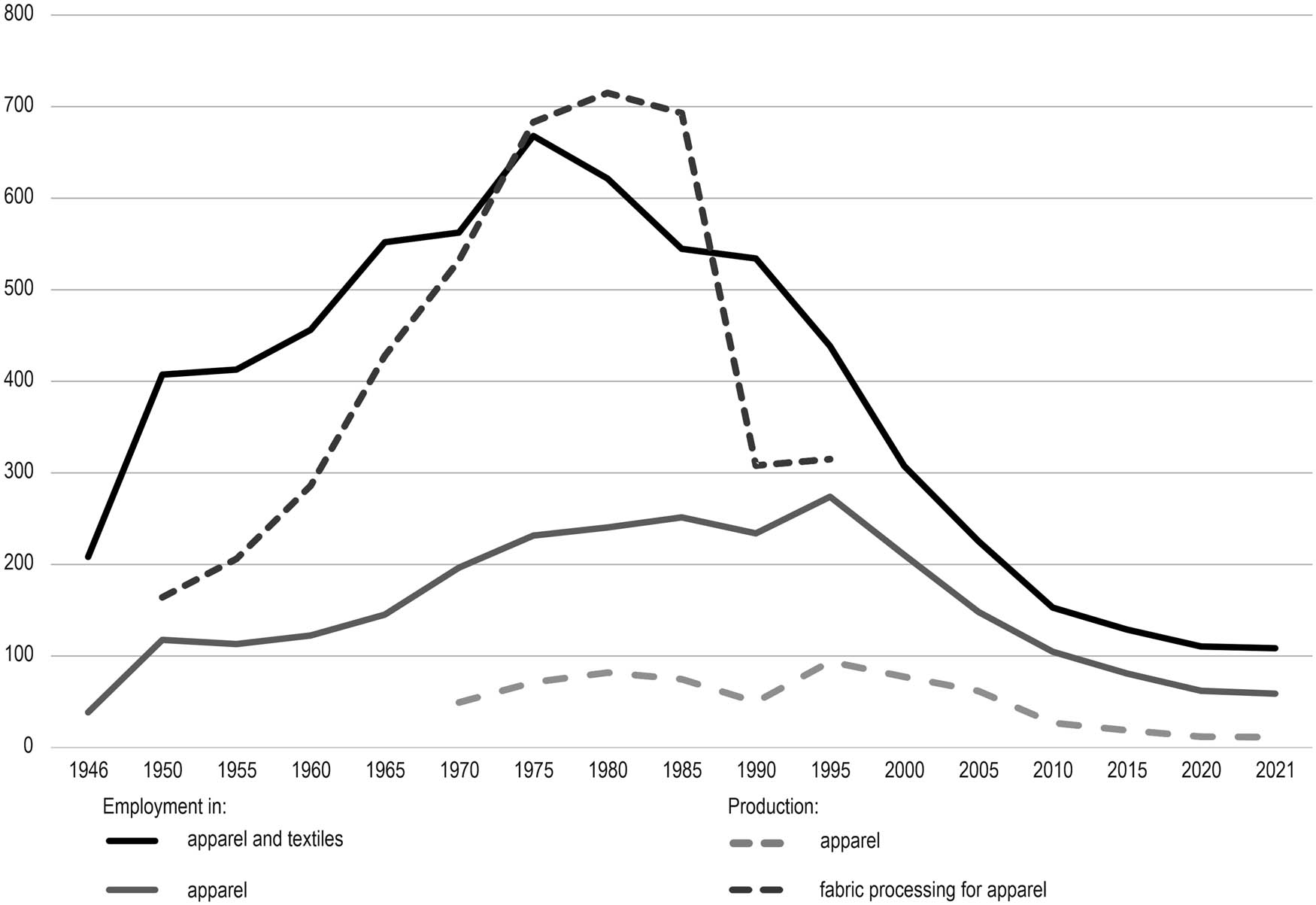

Any discussion on location tendencies in the contemporary clothing industry must take into account key long-term trends in respect of the size and structure of this sector in Poland. Both employment levels in the textile and clothing industry in Poland and its output reached a peak in the mid-1970s [50]. They started to decline significantly in the last decade of real socialism (1980s) (Figure 1) and continued to shrink in the decades after the reintroduction of capitalism and democracy. This decline affected the entire light industry sector, but was particularly significant in textile and clothing production. In 1993, production of textiles and clothing was jointly responsible for 12.9% of total employment in industry in Poland. By 2021, this share had dropped by two-thirds, to 4.2%, with textiles responsible for 1.9% of industrial employment and clothing for 2.3%, respectively (Table 1).

Productiona and employment (employees, ’000s) in the textile and apparel industries in Poland, 1946–2021. aData for volume of production for 1946–1995 expressed in millions of metres of processed fabrics, as only this type of data are available; data for 1970–2021 in millions of items of clothing. Source: authors’ own elaboration based on SP data.

Share of employment in the textile and clothing sectors in total employment in manufacturing in Poland, 1993–2021

| Industry | Share in employment (%) | Change, 1993–2021 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 2021 | ||

| Metal goods | 4.7 | 12.7 | 8.0 |

| Rubber and plastics | 2.5 | 8.7 | 6.2 |

| Automotive | 2.7 | 7.9 | 5.2 |

| Furniture | 4.5 | 7.1 | 2.6 |

| Textiles | 5.2 | 1.9 | −3.3 |

| Clothing | 7.7 | 2.3 | −5.4 |

aThe most recent available data is for 2015. Source: authors’ own elaboration based on SP data.

As mentioned earlier, while in absolute figures, employment in the clothing industry in Poland is now miniscule in comparison to the levels in the 1970s or even the early 2000s, the sector still provides a significant number of jobs in both the national and European contexts. In 2020, both subsectors jointly employed over 100,000 people: 49,600 in textile production and 58,900 in clothing production. As such, in terms of the size of the workforce, the Polish industry represents 9.2% of the textile industry and 7.7% of the clothing branch in the European Union. Moreover, the decline in both production and employment has slowed in the past decade (Figure 1).

The general decline and shrinkage in the last three decades may be explained by several factors. First of all, since the 1990s, there has been easier access to and a steady increase in imports of textiles and clothing from abroad, mainly from Asia, with domestic demand switching or even displaying a preference for (especially in the first years after 1989) imported goods. As early as in the 1980s, Asian countries, led by China, became the most important source countries of apparel imported to Poland [74].

Second, following the disintegration of the Soviet Bloc, including the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, Polish textile and clothing producers lost their major export markets (the former Soviet Union and other communist countries). In 1989, Poland exported 32% of its woven garments to the Soviet Union, while by 1996, exports to Russia accounted for only 1% [75]. Furthermore, many of the large enterprises with outdated equipment, business, and marketing models that had dominated the industry prior to 1989 were unable to compete with foreign firms or newly founded smaller Polish players [55]. The period of transformation therefore saw first the privatization and then the closure of many companies.

Still, in the first decade of transformation, the sector managed to find niche markets, initially mainly producing (sewing) for foreign labels and brands (as subcontractors for Western firms which offshored their production to Poland, a practice which had existed in communist times but intensified in the 1990s) [69]. Former employees of state-owned firms and other new entrepreneurs with links to the sector were also quite active in establishing new enterprises, drawing on skills and knowledge developed in communist times, and employing experienced workers from who had been laid off by older, former state-owned firms which failed to survive in the free market. Machinery and equipment from closed or restructured companies was initially the basis for many new business activities. Foreign investments in the sector were also relatively frequent in the 1990s, but fragmented, often short-lived and much smaller in scope than in other branches of industry (especially in the Lódź region) [76].

The competition from countries with lower labour costs, most of them in Asia, grew in the first decade of the twenty-first century, leading to a further decrease in employment in the sector as not only foreign subcontractors but also more successful Polish firms in the clothing sector started to offshore their production outside Europe in line with the growing scale of their operations [77]. Although not many of those companies have survived until today, both a few well-known brands from communist times which have undergone a complex privatization, restructuring, and consolidation process (one prime example would be VCR S.A., present on the Warsaw stock exchange since 1993 – initially as Vistula S.A. [70] – and today with a portfolio which is a mixture of brands renowned before 1989, such as Vistula, Bytom, Wólczanka, and others such as Kruk and Deni Cler), and firms founded in the 1990s (the above-mentioned leading Polish fashion company LPP S.A. is a good example), are now registered and function above all not as fashion producers but as fashion retailers with design, promotion, and logistic departments. Even if a certain (small) share of their production takes place in Poland, even this is subcontracted out to smaller firms (and may be understood as domestic onshoring).

This state of affairs is reflected in data on firms in the textile and clothing industry in Poland. Over the transformation period, there has been a huge decrease in average company size. There are now very few large firms (Table 2); the industry is dominated by small and micro firms (of up to nine employees). In 1990, there were over 100 textile and clothing firms in Poland with a workforce of over 1,000 people (86 in the textile and 20 in the clothing industry). By 2020 this figure had declined to four (three in the textile and one in the clothing industry). From the mid-1990s until the end of the 2000s, the number of newly registered firms also decreased. This trend has been reversed in the past decade. At present, the total number of firms continues to fall, but every year, 1,000–1,200 new textile businesses and 1,500–2,000 new clothing production firms are established. The survival rate of companies established in the last few years was slightly higher in the clothing sector than in the textile sector.

Firms in the textile and clothing industry in Poland with over 1,000 employees, 1990–2020

| Subsector | Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2020 | |

| Textiles | 86 | 39 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Clothing | 20 | 15a | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

aData for 1994. Source: authors’ own elaboration based on SP data.

4.2 Location of firms in the clothing sector

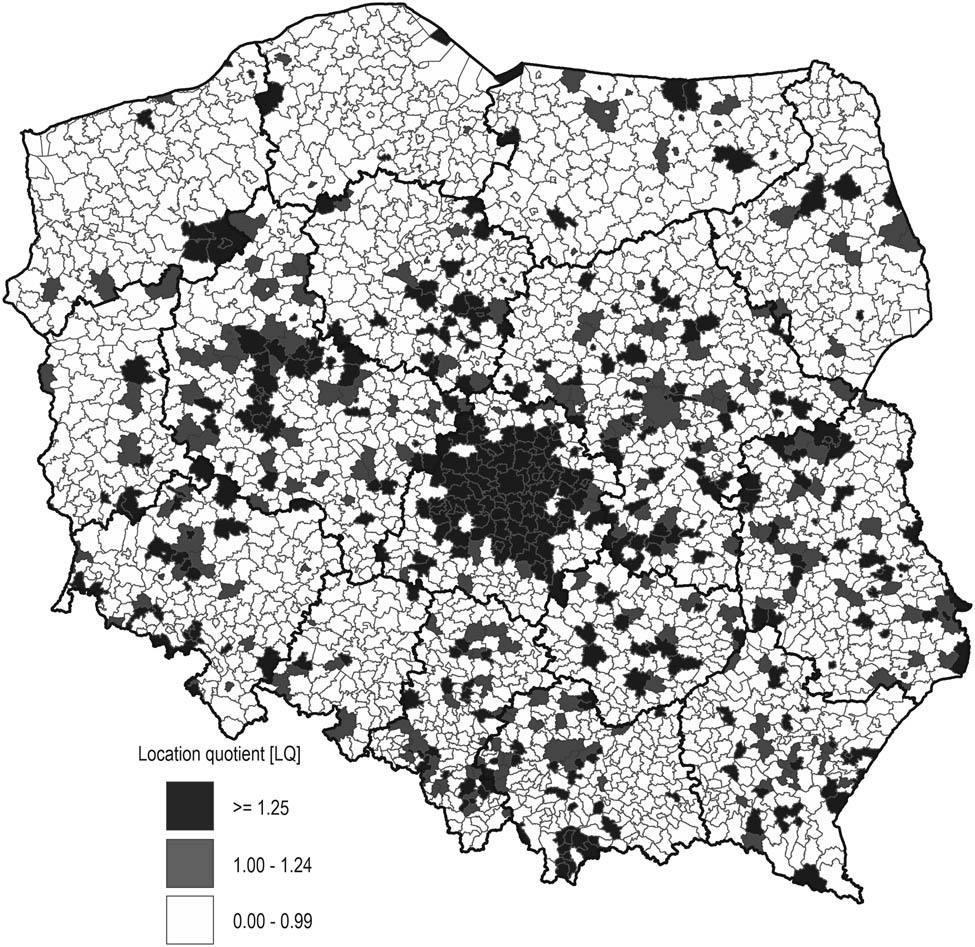

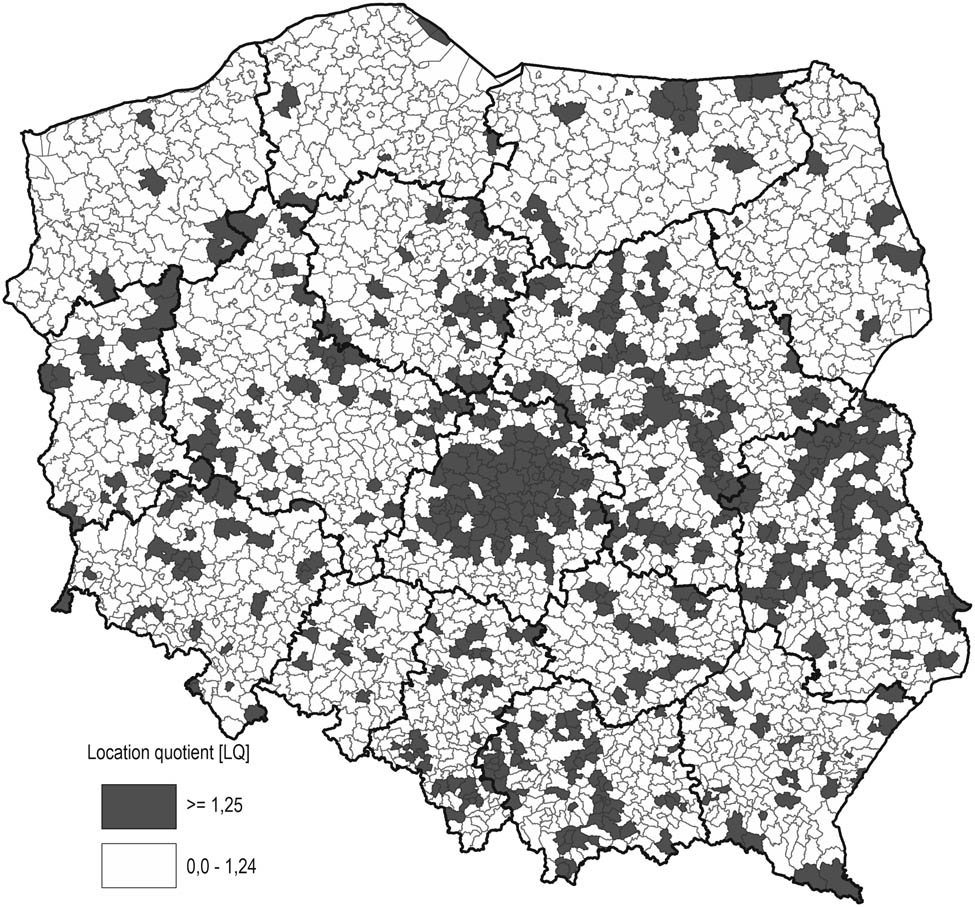

The changes taking place in the clothing industry are to some extent reflected in its spatial patterns. Apart from Lodz and its broad hinterland, the highest current LQs of the clothing industry are linked to Poznań and the vicinity, and to some extent Warsaw and Kraków (Figure 2).[5] These urban agglomerations are home to both numerous micro and small enterprises and the headquarters of major Polish fashion firms, which, as mentioned earlier, having retained control over the clothing design/conception phase and its distribution, now function mainly as fashion retailers and not as fashion producers. There are also moderate concentrations of firms in the clothing industry in connection with the continuation of earlier traditions (e.g. Legnica and its vicinity in the Silesian region), specialization in a certain type of apparel (e.g. lingerie in the Białystok area in the Podlachian region), lasting traditions of the textile and clothing industry enabling smaller-scale continuation (e.g. Bytom, the vicinity of Częstochowa and Bielsko-Biała in the Silesian region, or Kęty and Andrychów in Małopolska region), broader light industry experiences (e.g. Radom), and traditions of smaller-scale production (the Podhale region). Some concentration is also visible in current and former regional capitals (e.g. Kielce, Lublin, Toruń, Zielona Góra, and Jelenia Góra) or urban agglomerations (e.g. Rybnik). Measured using LQ, the clothing industry remains important in some peripheral areas – selected municipalities scattered across practically all regions of Poland, though they are less visible in the Opole and Pomerania regions (with the exception of Wałcz county).

LQ of firms in the clothing sector (NACE 14) in Poland in 2023. Source: authors’ own elaboration based on SP data.

In this respect, there seems to be a visible difference between the numerous SMEs, which, although attracted to larger cities, are still more evenly spread all over the country, and produce domestically, and the smaller group of the leading large Polish firms in the fast fashion sector with headquarters, design, and logistics centres in a few major cities, which mainly offshore, but may also onshore to smaller, more peripherally located firms.[6]

The main seats and design centres of 84% – i.e. 46 of the 55 leading Polish brands (fast fashion and premium mass production) – are located in only five urban agglomerations: Kraków (11), Łódź (11), Warsaw (10), Gdańsk, and Poznań (7 each). The outliers are either in the same regions, often with connections to these urban centres, or in historical centres of the clothing industry, often drawing on skills carried over from communist times and developed as a result of the existence of headquarters or branch plants of former larger state-owned companies (e.g. G8 S.A., the owner of the Lancerto brand, based in Łańcut, where the Vistula production facilities used to be located).

In comparison to the clothing industry, textile industry location to a larger extent follows traditional concentration patterns of the sector [50].[7] Average firm size is also larger for the textile sector, which has more openings to explore new qualitative niches thanks to textile innovations [15,16,51].

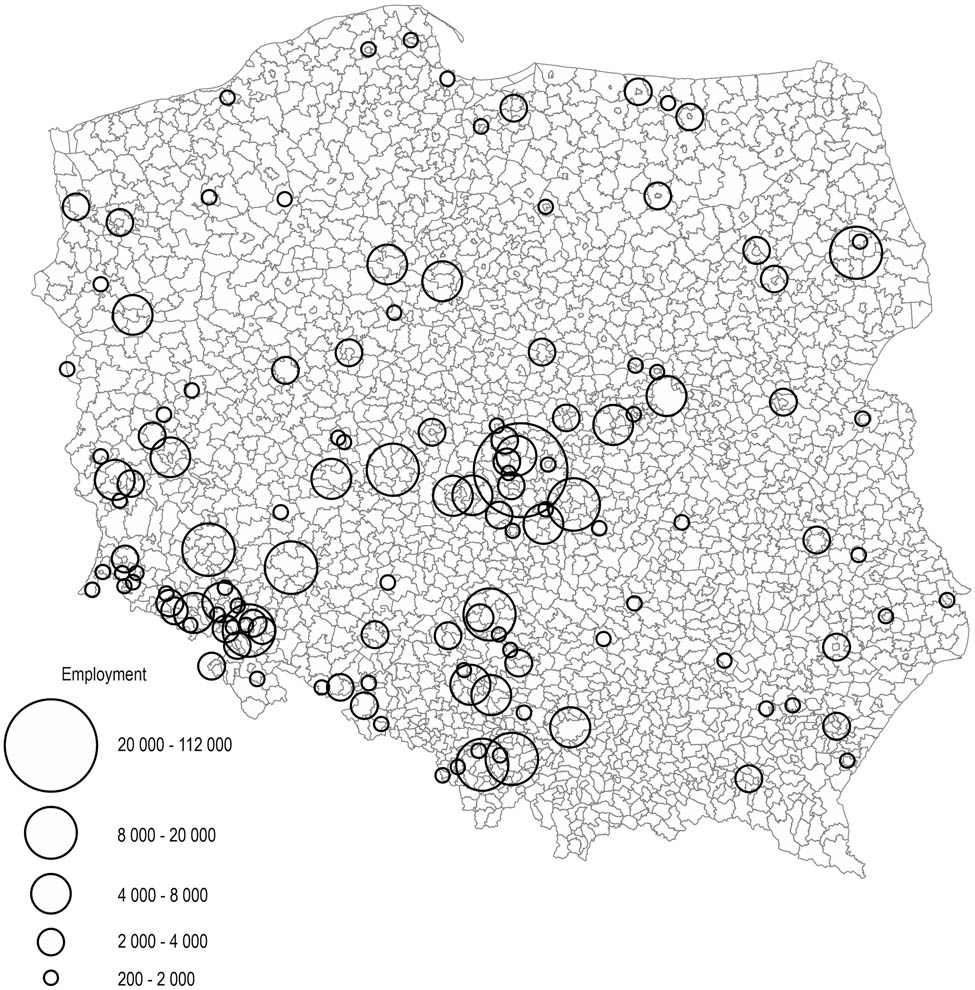

If we look at company numbers, with the exception of southern Lower Silesia, their locations seem largely to follow historical location patterns inherited from pre-communist and communist times (similar to other areas of light industry) (Figure 3). The picture is more complex if we take into account the number of people employed by the top 100 firms in the clothing industry (registered as clothing producers) and employment in the top 10 Polish fashion firms (owners of leading brands), which tend to subcontract (onshore) and offshore production, but are also the largest employers in the fashion industry, employing fashion designers and other clothing design and prototyping specialists (Figure 4). Over the last four decades, the traditional centres of the clothing industry – Łódź and its region, selected municipalities in Upper Silesia (both in the north, around Częstochowa, in the Upper Silesian Conurbation, and in the south, near Bielsko-Biała) have significantly downsized in employment, but remain important production areas. The relative importance of the Poznań region, the Warsaw agglomeration, and regions in Eastern Poland has been maintained or even enhanced. The regions in western Poland (Pomerania, Lubus, Lower Silesia), in turn, have declined in importance with respect to employment in the clothing industry. Last but not least, the relative importance of Kraków and Gdańsk has increased, mainly due to employment in the headquarters and R&D centres of major fast fashion firms. Employment in firms located in more peripheral locations, which, still tend to be focused on less sophisticated OPT, shows signs of decline.

Employment in the clothing and textile industry in Poland in 1980a. aEmployment in companies including branch plants. Source: authors’ own elaboration based on Ministry of Light Industry data.

Employment in the 100 largest clothing and fashion firms in Poland in 2018a. aTo reflect the current situation, the figures for employment in the largest firms, representing NACE 14, were complemented with data on employment in the 10 largest Polish fashion firms (NACE 46 or 47). Source: authors’ own elaboration based on National Court Register (KRS) reports for turnover in 2018.

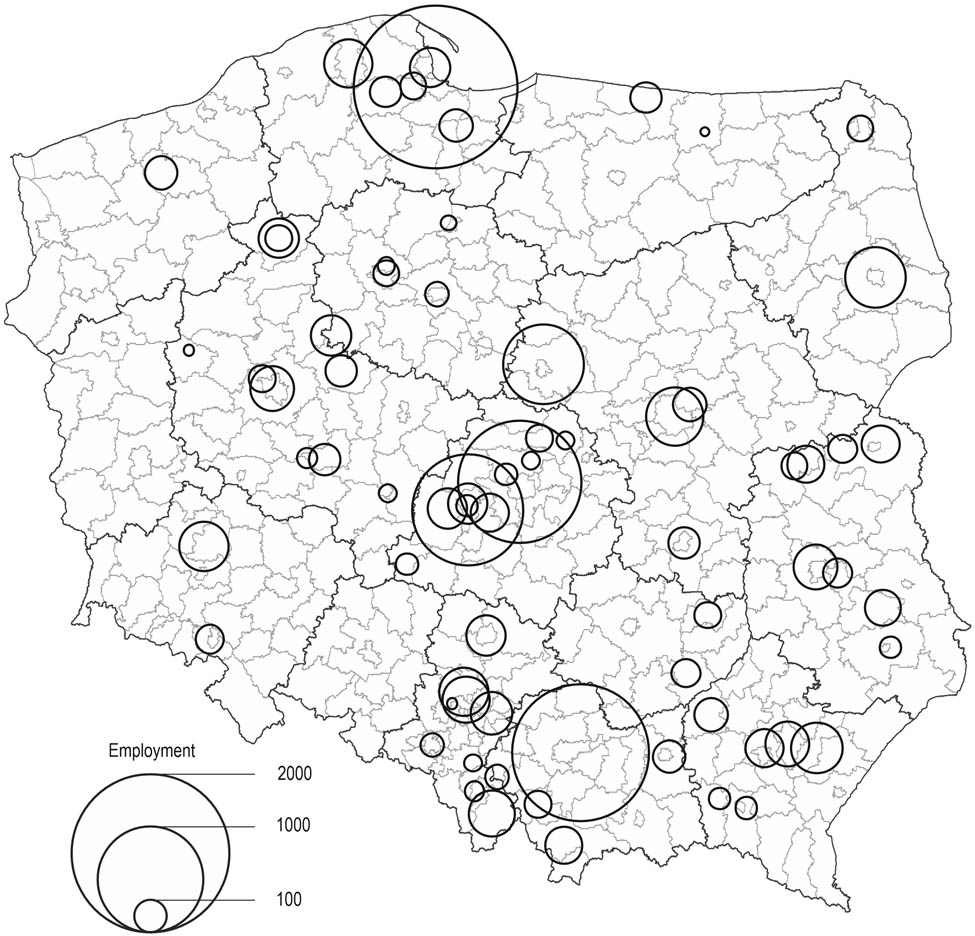

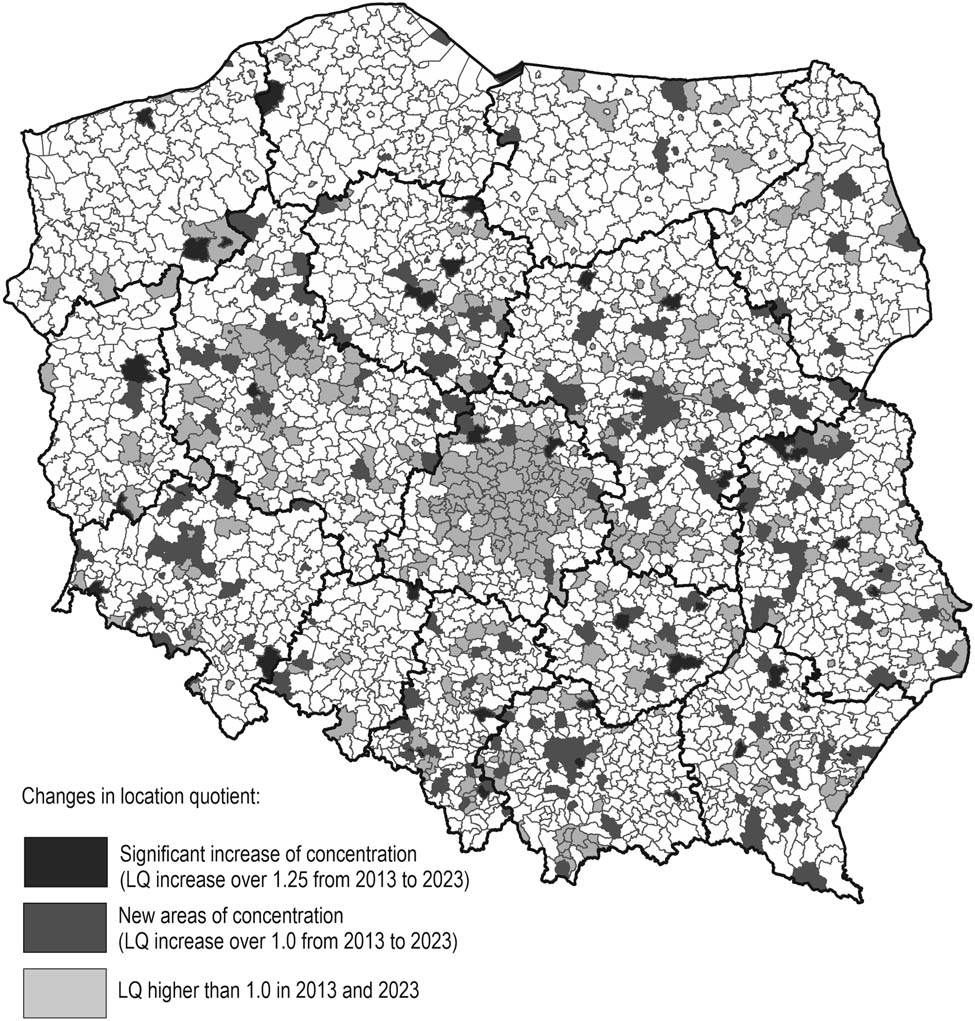

A more nuanced picture also emerges if the LQ is analysed longitudinally, looking at its changes in recent years (Figure 4). Changes in the LQ of apparel companies in Poland between 2013 and 2023 show that, although the Łódź region remains a leading area of apparel manufacturing in terms of number of companies and employment levels, changes in the relative concentration of the industry are taking place elsewhere, above all in the Warsaw and Kraków agglomerations, selected locations in Upper Silesia, mainly building on existing capabilities, and the Poznań agglomeration. Among the smaller regional capitals, in Kielce and Toruń and its vicinity, the LQ has also increased significantly. The share of clothing companies in the structure of local economies is increasing, not only in the country’s largest urban centres. There is also a clear trend towards economic suburbanization, probably following the processes of demographic suburbanization. However, it is not only the largest cities and their surroundings that have recently experienced an increase in the relative concentration of clothing companies, new fashion companies are also being established in the Subcarpathian region, e.g. in the vicinity of Rzeszów, in the Wałcz county in the south-eastern corner of the Pomerania region, around Międzyrzec and Świebodzin in the Lubus region, Legnica in Lower Silesia, and in the northern part of the Lublin region (around Biała Podlaska, Łuków, and Międzyrzec Podlaski), as well as in peripheral areas of the Podlachian region and the Holy Cross region. A very interesting change in the spatial differentiation of the LQ index is the absence of the revival observed since 2014 in Lower Silesia, a region rich in clothing manufacturing traditions, apart from the area of Legnica and Ząbkowice Śląskie. Looking at the LQ of new firms in the clothing sector established in 2013–2023, the historic “Polish Manchester” – Łódź and its surroundings – continue to attract new clothing firms (Figure 5). The situation is similar in smaller garment production centres such as Radom, parts of Upper Silesia (Czestochowa and the Upper Silesian conurbation, Bielsko-Biała, and Rybnik). Apart from the absence of major changes and the relatively smaller visibility of the clothing production sector in the northwestern part of the country and in the Opole region, and a slight predilection for the broader functional zones of selected larger Polish cities (Kraków, Warsaw, Poznań), there are, however, no clear patterns which would point to the relocation of the clothing industry in Poland. Neither the pandemic nor the outbreak of the Russian–Ukrainian war have changed the existing situation significantly, despite the short-term turbulence.

LQ of newly established firms in the clothing industry (NACE 14) in Poland in 2013–2023. Source: authors’ own elaboration based on SP data.

The current distribution of the firms in the clothing sector is therefore a combination of the continuation of historical location patterns, though with the disappearance of some clothing production centres, and the increasing importance of selected major cities and their metropolitan areas.

4.3 Selected factors influencing survival, transformation, and changes in the location patterns of the sector

4.3.1 Export and supplying other economic sectors

One of the more traditional factors affecting the rate of change in the textile and clothing industry is the continued importance of exports – production and sewing for foreign companies, either as OPT or more complex OEM (despite the relocation of some subcontracting for foreign luxury brands to countries with lower labour costs) [27,42], exports of finished goods, as well as production for other sectors of the domestic economy that require good quality textiles and clothing. This can be seen in the inter-industry input–output characteristics for textiles, which have remained at similar levels in recent years. In value terms, about a third of the textiles produced in Poland are further processed within the country as intermediate goods, only about 14% are sold for final consumption, and just over half are exported. For clothing, the shifts are more visible – in terms of the value of manufactured apparel, the share of clothing produced for intermediate and final consumption has decreased, while the share of clothing exported has increased. In 2015, two-thirds of the domestic production of clothing in Poland was exported (Table 3).

Input–output characteristics of domestic output of textile and clothing industry in Poland, 2005–2015a

| Branch | Intermediate consumption (%) | Final consumption (%) | Export (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | |

| Textiles | 33.5 | 31.8 | 33.8 | 11.1 | 16.9 | 13.8 | 55.2 | 51.4 | 52.3 |

| Clothing | 12.4 | 10.9 | 9.7 | 27.8 | 25.1 | 24.3 | 59.9 | 64.1 | 66.3 |

Source: authors’ own elaboration based on SP data, current prices.

aThe most recent available data are for 2015.

A comparison of the main directions of intermediate consumption of clothing industry output in Poland in 2005 and 2015 shows an increase in dependence on demand from sectors such as public administration, transport and logistics, construction and sports, and entertainment and leisure, i.e. sectors where corporate or functional clothing with a specific design, high quality, and durability is very important. For example, the police and military, medical services, transport, and construction workers often require specialist clothing of above-average durability and quality. The hotel and catering industry, on the other hand, requires not only textiles (e.g. bed, bath, and table linen), but also durable clothing with a specific design, reflecting the company’s desired image. The dynamic development of the leisure and tourism sector, including the catering industry, in Poland in recent years has therefore created additional demand for textiles and clothing produced in Poland. Some textiles and clothing processed in Poland can also be considered as intermediate goods, as patterns, prints, or other elements are added.

From a longitudinal perspective (2005–2015), there is marked growth in intermediate use of domestically produced textiles by five main intermediate consumption sectors. The leading sectors in this respect have not changed, though the importance of the textile consumption by the automotive sector and the furniture sector has declined (despite an increase in the share of these industries in the economy), while consumption of domestic textiles by the clothing and textile sector has increased. The share of domestically produced textiles consumed by the domestic clothing industry has increased particularly significantly. This may mean that textiles produced in Poland are now to a greater extent used for making garments in Poland, i.e. further processing by the Polish clothing industry rather than the automotive or furniture sectors.

With regard to clothing, however, the importance of intermediate consumption by such sectors as public administration, household services, business services, and retail is clearly in decline, while the share of domestically produced clothing treated as intermediate goods for further processing by other domestic clothing companies and by transport, construction, and firms in the tourism and leisure sector has increased (hence the relative importance of these segments as intermediate consumers of clothing made in Poland). The further development of tourism and leisure services, combined with the growing purchasing power of Polish consumers and an increase in the number of incoming foreign tourists, can therefore be seen as beneficial for the Polish textile and clothing industry (Table 4).

Main sectors involved in intermediate consumption of textile and clothing goods produced in Poland in 2005 and 2015 (share in the total value of textile and clothing goods purchased for intermediate consumption)

| Textiles | Clothing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2015 | 2005 | 2015 | ||||

| Sectors | (%) | Sectors | (%) | Sectors | (%) | Sectors | (%) |

| Textile industry | 27 | Clothing | 34 | Public Administration | 22 | Clothing | 30 |

| Clothing | 20 | Textile industry | 31 | Household services | 20 | Public administration | 7 |

| Furniture | 17 | Furniture | 11 | Clothing | 9 | Transport | 6 |

| Automotive | 11 | Rubber and plastics | 7 | Other business services | 5 | Construction | 5 |

| Rubber and plastics | 6 | Automotive | 6 | Retail | 4 | Sports, entertainment, leisure services | 4 |

| Total | 81 | Total | 88 | Total | 60 | Total | 54 |

Source: authors’ own elaboration based on SP data for domestic output in current prices.

4.3.2 Exploiting market opportunities: Specialized qualitative niches, consumer ethnocentrism, and the growing demand for sustainable fashion

Increasing disposable income and global trends are influencing the changing needs and preferences of Polish consumers with regard to clothing. On the one hand, wealthier, better educated consumers value above all unique, good-quality garments which lend them a symbolic distinction. Some of them do so by buying clothes from global luxury fashion brands (there is a longstanding tradition of appreciation of foreign, in particular French and Italian goods in Poland); others, however, prefer local brands or made-to-measure products.

The increasing awareness of the need for more sustainable consumption in general, and more sustainable consumption of clothing in particular, also translates into greater attention to the quality of purchased garments (rather than simply to price and quantity), and into the desire expressed by some consumers to buy from locally based companies with a slow and ethical fashion ethos. Therefore, many of the newly established small fashion brands in Poland, both because of their owners’ personal convictions and in order to exploit these emerging market opportunities, associate themselves explicitly with sustainable fashion (underlining this in brand communication strategies and in their marketing mix: the selection of textiles, the production process and its ethics, an emphasis on local production and quality, etc.) [47]. So far, very few such firms have grown to medium size, but those that have expanded tended to outsource sewing to external partners in Poland. A good example of one such leading Polish sustainable fashion brand is Elementy. According to information on the company website, as of early 2024, its clothing collection was produced in several locations in Poland (depending on garment and fabric type), both larger cities, such as Bielsko-Biała, Łódź, and Warsaw, and smaller municipalities (Brzeziny, Gostynin, Kobyłka) as well as in Turkey (this in view of its specialization in production of denimwear) [25].

Some firms also hope to benefit from the luxury consumer ethnocentrism by targeting clients of higher-end Polish brands designed and at least partially produced in Poland [47]. Others aim to appeal to creative patriotism by promoting domestic design, or by including references to national, local, or regional culture and heritage through ethno-design or “patriotic” garments. Although, according to the most recent study [64], more comprehensive consumer ethnocentric attitudes are displayed in the Polish context by a relatively small share of fashion consumers (a survey of the representative sample of the adult Polish population revealed that only 12.9% of the fashion consumers could be considered as strongly ethnocentric – i.e. both declared strong preferences for domestic production and domestic design and had clothes with ethnocentric symbolic connotations in their wardrobes), domestic production is fairly highly appreciated (i.e. declared as an important factor during fashion shopping) by over one-quarter of the Polish population (25.9%). While the connection with original design and higher quality is more likely to be valued by younger, better educated and wealthier consumers from larger cities, domestic production as such is also important to older residents from rural areas or small and medium-sized towns, especially those with higher incomes and an optimistic outlook on their material wellbeing.

Apart from corporate and specialist functional wear used in professional situations (e.g. protective clothing) [58], qualitative niches tapped into by Polish fashion producers may also include design and production of original, specialist attire associated with particular leisure activities and sports (e.g. climbing, running, or sailing), or apparel meeting the needs of particular social and age groups (e.g. young mothers) or enthusiasts of a specific fabric type (e.g. flax linen). Last but not least, some clothing companies have noticed the appeal and market potential of domestically produced garments and accessories, especially smaller items such as hats, socks, or belts, as original tourist souvenirs.

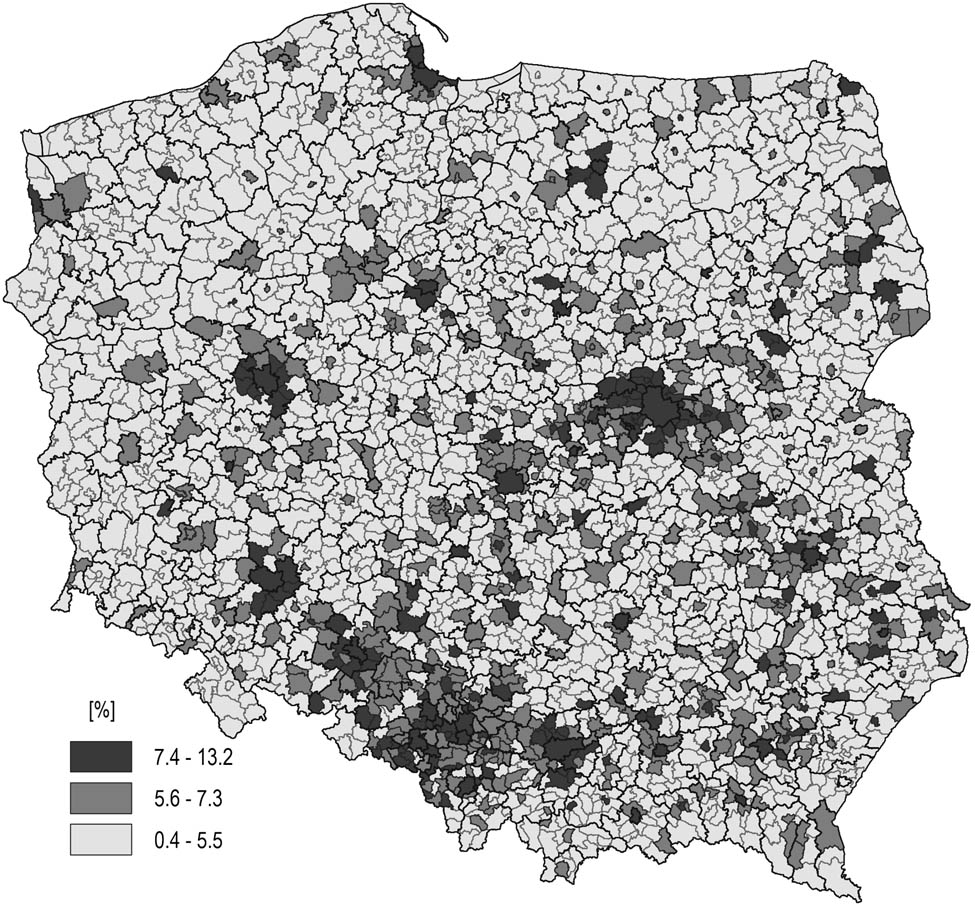

4.3.3 Evolution from a traditional towards a creative sector

Recognition in the clothing production sector of the importance of design, quality craftsmanship, and either technological sophistication or unique aesthetic qualities combined with attentiveness to users’ functional and symbolic needs points to its ongoing evolution in the direction of a creative industry. Several factors seem to confirm this in the Polish context. The new geography of clothing production in Poland reflected in the changing LQ discussed above overlaps significantly with the attractiveness of Polish municipalities as locations of creative firms in general. This is visible, for instance, when Figures 4 and 6 are compared with Figure 7, which shows “creative hotspots” – Polish municipalities where between 2013 and 2019 the share of newly registered creative businesses in the total number of registered firms was particularly high.[8] The aforementioned large cities (in particular Kraków and Warsaw), followed by Poznań, the Upper Silesian Metropolitan Area (GZM), and Gdańsk, are also home to the largest number of and most diverse institutions and infrastructure supporting creativity and innovation, such as business and technology incubators, fabLabs, and makerspaces [81].

Changes in the concentration of the clothing industry (NACE 14) in Poland in 2013–2023. Source: authors’ own elaboration based on SP data.

Share of newly registered creative firms in the total number of newly registered businesses in Polish municipalities between 2013 and 2019. Source: authors’ own elaboration based on SP data.

Second, the urban areas which have proved most successful in attracting the creative sector in Poland are also the most attractive to fashion designers in terms of the fashion design education possibilities and opportunities for professional buzz they offer, as well as their potential for direct contacts with end consumers at independent B2C fashion fairs or other fashion-related venues (Figure 8). Finally, the leisure-related fashion market has become an important aspect of the experience economy of major Polish cities, in particular the two largest metropolitan centres (Warsaw and Kraków).

5 Conclusion

The Polish clothing industry has significantly shrunk but also transformed in the last few decades, evolving towards specialization and a broader creativity-based fashion industry. Our research seems to confirm previous observations about its different phases of restructuring which Stępień and Młody termed “the fall of a giant, vestigial existence, and rejuvenation” [67]. Its further survival and transformation are predicated upon selective and diverse upgrading processes and Poland’s location in an intermediary position between highly developed Western economies, European peripheries, and Asia [22,23]. The significant size of the domestic market (in the European context) as the largest in CEE, and the growing purchasing power of Polish consumers are additional factors in the enduring presence of clothing production in Poland. Another important consideration is the proximity of the German market and its demand for fashion and workwear, as due to its geographic proximity and size, this remains the most important export destination for clothing produced in Poland [58]. Key to the persistence and evolution of the textile and clothing sector in Poland, aside from the continuing importance of historical development patterns, is the growing significance of the technological and design aspect of the clothing production process [84]. Some recent developments, such as the increasing recognition (among both policy makers and consumers) of the need to make the fashion sector less harmful to the environment on the European level, and the outbreak of the armed conflict just beyond the Polish border, which has put an end to or significantly limited nearshoring possibilities to Ukraine, are also of note.

The upgrading processes observed in Poland vary in terms of type, direction, and geographic focus. On the one hand, a shift towards higher-value-added products (e.g. corporate, technical, and specialist clothing; leisure- and sportswear; well-designed, premium products with a sustainable orientation; and hosiery with specific aesthetic appeal) and venturing into new markets for sewing (e.g. for the automotive industry) is visible, similar to trends observed in earlier periods not only in Poland, but also in Slovakia, Romania, and Hungary [22,23,24,28,85]. On the other hand, Poland’s overall upward trajectory in global clothing value chains is reflected in the existence, development, and international expansion of some leading Polish brands. The largest players are able to compete successfully with major foreign labels not only in domestic market segments but also abroad, in particular on other CEE markets.[9] They have strengthened their focus on the knowledge-intensive, more creative, and value-capturing stages of the value chain, continuing developments observed among some Polish firms already in the early 2000s [70].

At the same time, their domestic outsourcing activities, drawing on the flexibility and proximity of domestic producers, facilitate the existence of a limited number of smaller manufacturers, though larger-scale reshoring is very unlikely [48,77]. This issue has also been underlined by other authors, who have noticed, for instance, that concern for quality of production and effectiveness of operations, which includes understanding and responding to particular consumer needs, is an important driver of reshoring or in avoiding offshoring, visible especially in the specialist protective workwear and premium clothing segment [48]. In the Polish case, although OPT for foreign buyers still exists, the transformation and current survival of the clothing sector therefore seems to be much more dependent on and linked with Polish ownership of major brands rather than cooperation with Western buyers [28].[10] The position of Polish firms and their connections with certain countries are likewise different than those of other CEE countries. For instance, Poland has not become as important a location for Italian offshoring as Romania [85], but its domestic production is to a large extent dependent on the import of Italian fabrics, while clothes made in Italy are an important competition for apparel made in Poland due to their popular association with appealing design and quality.

In addition, the upgrading processes involve horizontal integration within the broader fashion sector. Polish apparel manufacturers and retailers are expanding the range of products they offer to include fashion accessories, footwear, and other related items (e.g. accessories for pets and home decor), while some Polish footwear producers are also expanding into clothing and fashion accessories.

The increasing importance attached to the design phase of garment development may be a good reflection of the upgrading processes taking place in the Polish clothing industry [19]. Upgrading through design is observed in three ways. Major fashion firms (registered as retailers) concentrate their efforts on design and develop their design departments. Other producers are moving into more upscale or fancy market segments using design (for instance, emphasizing the aesthetic rather than utilitarian qualities of socks). There has also been rising interest in and visibility of smaller-scale, bespoke, and more luxury or artisanal small-scale production, taking place, as in other countries [22,23,28] mainly in the capital, Warsaw, as well as in Kraków and other major cities.

The observed changes are both reactive and proactive. Among firms which continue acting as traditional OPT suppliers it seems to be primarily reactive. Upgrading by this group is connected with a broadening of their offer to include new processes, or limited attempts to increase the efficiency of production processes. In contrast, firms that function under their own brand, in particular larger ones, have always been proactive (e.g. diversifying their products to include more sustainable ones, broadening product ranges, or introducing new fabrics). The process of change, as suggested in other publications [26,27], is also uneven and complex. Leading Polish fashion brands continue to function within the fast fashion framework but introduce some sustainable and higher-quality product lines, leading them to source some production domestically, or move into nearshoring, and to develop the domestic design phase further. Today’s typology of Polish fashion firms comprising clothing producers and clothing retailers with their own design departments is increasingly similar to that of Western European (e.g. Italian) ones. A small number of leading larger firms focus on high-value-added activities (design, marketing) but outsource production to subcontractors domestically or abroad. There are still firms that concentrate mainly on the production phase, working for both domestic and foreign buyers, and finally, there are many, usually smaller, firms geared towards more upscale, specialist, or niche market segments that oversee and are involved in all stages of the value chain (from design to retail).

Although from a geographic point of view, the distribution of clothing industry players is still to a large extent path-dependent and, apart from the Łódź region, the structure of the industry developed prior to 1989, relatively more dispersed than that in other CEE countries, persists to a larger extent, nonetheless, some new spatial patterns are emerging. Unlike in Slovakia, Romania, or Hungary, there has been no particularly visible relocation of production activities to poorer regions in Eastern Poland; instead, a more scattered location pattern is observed. Clothing firms are still present in most Polish regions (also in the south and west of the country), wealthier and poorer, more centrally located and peripheral. This is to some extent similar to the diverse location structure of the Ukrainian clothing industry observed before the war [53], though of course at different employment levels. The Łódź region, despite diversifying its economic structure and the significant development of other industrial sectors (e.g. household appliance production), still remains the centre of Polish clothing production [25]. Some concentrations of clothing industry players likewise remain or even have become relatively more visible in other traditional locations (e.g. Legnica in Lower Silesia, certain counties in Upper Silesia, and Łańcut in the Subcarpathian region).

The most interesting process observed is the strengthening of the visibility and presence of the more broadly understood fashion industry, including clothing design and production, in major Polish cities [22,23,28]. The concentrations of creatives dealing with the conceptual phase of clothing production (design, prototyping) in selected urban locations accentuates this trend. Major Polish fashion companies have their headquarters and design offices located in a few of the largest cities, which they mainly use as design and logistic centres for offshored clothing production. In addition, their proximity to fashion schools allows them to tap into a constant source of new potential of creative workers – adepts of clothing design who, in return, gain useful practical experience in the fashion market and, after working for a major label, sometimes decide to start their own businesses. The main urban centres and metropolitan areas, which are attractive for the creative sector in general, are therefore also very appealing to fashion designers and smaller, independent fashion firms. Although the digitization of the economy may ultimately weaken some of the above trends, fashion SMEs, especially the smallest creative firms run by individual fashion designers, may still feel the need to ascertain the symbolic value and authenticity of their products, associate with an attractive city image, and be a part of the professional fashion community and its buzz [86] by locating themselves in or near major Polish urban centres. Kraków, Warsaw, and to some extent Poznań and Gdańsk are current leaders in this respect, functioning as multidimensional fashion cities, while Łódź, although maintaining its position as a manufacturing fashion city [48], to some extent lags behind in terms of broader fashion ecosystem development dynamics. In this context, our findings indicate that, contrary to expectations, Wrocław – another large Polish city with significant creative potential – is overall not a significant point on the map of major Polish fashion centres. This finding echoes the recent assessment of the potential of the textile industry in Poland by Jabłońska et al. [51] who pointed to Mazovia, Małopolska, and Silesia as the most promising regions for its development and noticed the weaker development capacities, despite strong textile traditions, of the Łódź region, Lower Silesia, and regions in Eastern Poland (apart from Podkarpackie). It is also worth mentioning than unlike in other, smaller CEE countries where the urban network is much more monocentric (in particular Hungary and Slovakia, and to a large extent also Czechia) [87,88], in Poland, larger cities other than the capital also have the capacity to develop into more prominent fashion hubs.

Conversely, the current situation of the Polish clothing industry may be analysed from the point of view of some downgrading tendencies. Retaining at least part of the clothing production process in Poland, despite both foreign and Polish consumer demand for it, may be fraught with significant barriers. First and foremost among these is the aging and shrinking population of skilled seamstresses [89] coupled with the ongoing decline of traditional vocational education for the textile and clothing sector [77]. This population has been to some extent temporarily rejuvenated by the influx of younger, skilled Ukrainian seamstresses, due to both economic migration prior to the Russian attack on Ukraine and the arrival of numerous refugees since the beginning of the war. The relatively uncertain and unappealing working conditions and still comparatively low wages discourage younger people from choosing more traditional, lower-level careers in the fashion industry other than that of a creative (in particular designer) involved in the conceptual phase of product development or running their own firm. The downsizing of the sector has therefore led not only to the loss of ability to produce larger quantities of goods, but also to an ongoing loss of skills and technical capacities to sew more complicated garments (e.g. outerwear, jeans), and may in the long run compromise not only production but also design capabilities [19].

Another downside of the flexible, on-demand model production in smaller batches that is in line with some sustainable fashion ideas is the difficulties such an approach poses to the stability of the day-to-day functioning of manufacturing firms. Small fashion firms that are involved in all stages of the value chain are often also in a precarious situation. This is due to both insufficient domestic demand (stemming partly from purchasing power, partly from lack of awareness) and lack of sufficient marketing resources to compete effectively with major (domestic and foreign) fast fashion players. The development of B2B fashion fairs mentioned above to some extent helps to promote them [5].

Developments such as a smaller scale of production and more flexible production, the move towards outsourcing and subcontracting domestically and abroad, the growing power of retailers – the shift from a manufacture-driven to a retail-driven market – and the focus on design and marketing observed in Poland since the beginning of the new millennium and in greater intensity in the last decade, are similar to those seen in the 1980s and 1990s in Western Europe and developed Anglo-Saxon countries such as Great Britain [10]. They are however modified – both hindered and speeded up – by context-specific factors and the emergence of new global considerations such as the rising importance and faster diffusion of sustainability paradigms from Western Europe [8,43,90], the need for more flexible and shorter supply chains (which became very visible during the Covid-19 pandemic), the possibilities offered by digitization, and the concentration of development and creativity in leading metropolitan areas.

Our research findings therefore indicate an ongoing evolution and spatial reconfiguration of clothing design and production in Poland, and point to the existence and growing importance of the increasingly complex fashion ecosystems [24,91] in certain major cities which act as growth poles for the broader fashion sector thanks to both public and private efforts. The longer-term sustainability of these ecosystems seems to be dependent on a host of internal and external factors, however, such as the political and economic situation; consumer awareness, attitudes, and behaviour; the effectiveness of the development strategies adopted by major Polish fast fashion brands and emergent sustainable brands; as well as the support and regulations created by public authorities at various levels of governance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would sincerely like to thank all reviewers of the paper. Their interesting and inspiring comments and suggestions are much appreciated.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the Polish National Science Centre, grant “Fashion market in the context of sustainable development,” grant agreement no. UMO-2018/31/B/HS4/02961 for the years 2019–2024. The publication has been supported by a grant from the Faculty Geography and Geology under the Strategic Programme Excellence Initiative at Jagiellonian University.

-

Author contributions: Conceptualization, A.K. and M.M.-K.; methodology, A.K. and M.M.-K.; analysis of data/investigation A.K. and M.M.-K.; writing–original draft preparation, M.M.-K. and A.K.; writing–review and editing, M.M.-K. and A.K.; visualization, A.K. and M.M.-K.; project administration, M.M.-K.; funding acquisition, M.M.-K.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Ethical approval: The conducted research is not related to either human or animal use.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Arnold, R. (2009). Fashion. A very short introduction, Oxford University Press (Oxford).10.1093/actrade/9780199547906.001.0001Search in Google Scholar

[2] Crewe, L. (2017). The geographies of fashion, Bloomsbury (London).10.5040/9781474286091Search in Google Scholar

[3] Scarpellini, E. (2019). Italian Fashion since 1945: A cultural history, Springer (Cham).10.1007/978-3-030-17812-3Search in Google Scholar

[4] Wilson, E. (2018), Fashion industry. In: Steele, V. (Ed.). The Berg companion to fashion, Bloomsbury Visual Arts (London).Search in Google Scholar

[5] Hołuj, D., Murzyn-Kupisz, M. (2022). Struktura przestrzenna targów mody w Polsce skierowanych do indywidualnych odbiorców. Studia Regionalne i Lokalne, 89(3), 67–85.Search in Google Scholar