Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) M4, M5, and M7 are subtypes of leukemia derived from myeloid cell derivatives that influences the results of the identification of AMLs, which includes myeloblast, monoblast, and megakaryoblast. Furthermore, they are divided into more specific types, including myeloblasts, promyelocytes, monoblasts, promonocytes, monocytes, and megakaryoblasts, which must be clearly identified in order to further calculate the ratio value in the blood. Therefore, this research aims to classify these cell types using the K-nearest neighbor (KNN) algorithm. Three distance metrics are tested, namely, Euclidean, Chebychev, and Minkowski, and both the weighted and unweighted were tested. The features used as parameters are area, nucleus ratio, circularity, perimeter, mean, and standard deviation, and about 1,450 objects are used as training and testing data. In addition, to ensure that the classification is not overfitting, K-fold cross validation was conducted. The results show that the unweighted Minkowski distance acquired about 240 of 290 objects at K = 19, which is the best. Therefore, the unweighted Minkowski distance is selected for further analysis. The accuracy, recall, and precision values of KNN with unweighted Minkowski distance obtained from fivefold cross validation are 80.552, 44.145, and 42.592%, respectively.

1 Introduction

Blood cancer or leukemia is a type of cancer discovered in the blood and bone marrow, which is caused by the rapid production of abnormal white blood cells, and it is one of the deadliest diseases in the world. Furthermore, its symptoms, which are sometimes difficult to detect, make it quite dangerous. Furthermore, it is caused by an excessive number of immature white blood cells in the human body, and the large number of immature blood cells actually inhibit the functioning of organs, which can lead to other diseases [1].

Leukemia is of two types, depending on the rate of growth of immature cells in the blood, acute and chronic leukemia. Both produce excess white blood cells that cannot properly function as antibodies. Acute leukemia can be recognized by the very fast multiplication of blast cells. It can lead to death in a matter of weeks or even days unless immediately and properly treated, while blast cells in chronic leukemia multiply slower than acute leukemia [2].

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is one of the main types, which is derived from the calculation of white blood cells from the offspring of myeloid cell. Its growth is so quick that the people with AML must get the proper and immediate treatment. Furthermore, AML is divided into eight groups of diseases based on the number of components of the white blood cells, namely, M0, M1, M2, M3, M4, M5, M6, and M7 [3]. AML subtypes are described in Table 1.

Subtypes of acute myeloid leukemia

| AML subtype | Name |

|---|---|

| M0 | Undifferentiated acute myeloblastic leukemia |

| M1 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia with minimal maturation |

| M2 | Acute myeloblastic leukemia with maturation |

| M3 | Acute promyelocytic leukemia |

| M4 | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia |

| M5 | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia with eosinophilia |

| M6 | Acute erythroid leukemia |

| M7 | Acute megakaryoblastic leukemia |

Some subtypes of AML such as M4, M5, and M7 are affected by the same type of precursor cells, and their precursor cells are myeloblast, monoblast, and megakaryoblast. They need to be precisely distinguished so that every cell can be counted [4]. These types of cells can be grouped into more specific types, which are used as the main factor ratio for AML M4, M5, and M7. They are myeloblast, promyelocyte, monoblast, promonocyte, monocyte, and megakaryoblast. Sample images for each white blood cell types are shown in Table 2.

Sample images of AML cells

| Myeloblast | Promyelocyte | Monoblast | Promonocyte | Monocyte | Megakaryoblast |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Setiawan et al. (2018).

2 Research method

The research consists of several steps. It started with data acquisition and ended with analyzing the results. The training and testing processes are carried out as the number of folds used in cross validation. These steps are inspired from Harjoko et al. previous research [1]. All the steps are illustrated in Figure 1.

Research steps.

2.1 Data acquisition

The AML M4, M5, and M7 extract features data were provided by Setiawan et al. [4]. These were basically blood smear images obtained from RSUP Sardjito Yogyakarta. The images were captured by using a 21-megapixel resolution digital camera attached to Olympus ocular lens with 1,000 times magnification. Furthermore, the features were extracted to obtain the numerical data. Six features are used as inputs for this research [1,4].

Cell area: the number of pixels that form an area of white blood cell, including nucleus and cytoplasm.

Perimeter: the outermost part of the cell object located right next to the background image.

Roundness: a degree of curvature measurement of an object that forms a circle.

Nucleus ratio: the value obtained from the ratio of nucleus area divided by the area of the cell body.

Mean: In this case, it is the average distribution of gray intensity values of each pixel in a gray scale image.

Standard deviation: measurement of the variation or dispersion of a set of value relative to its mean. It is also known as the square root of the variance.

In all, 1,450 cell objects were used as training and testing data. Each of the data rows was then labeled with white blood cell for validation purpose. In addition, six labels were given to the object, namely, myeloblast, promyelocyte, monoblast, promonocyte, monocyte, and megakaryoblast. The detailed number of objects in each AML preparation are shown in Table 3.

Number of objects

| AML subtype | Myeloblast | Promyelocyte | Monoblast | Promonocyte | Megakaryoblast | Monocyte |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M4 | 195 | 11 | 83 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M5 | 0 | 0 | 274 | 163 | 0 | 2 |

| M7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 722 | 0 |

| Total | 195 | 11 | 357 | 163 | 722 | 2 |

-

Ethical approval: The use of blood smear digital image dataset has been complied with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and in accordance the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the Medical and Health Research Ethic Comitee (MHREC) Faculty of Medicine Gadjah Mada University – Dr. Sardjito General Hostpital.

2.2 Data training

2.2.1 K-nearest neighbor

The K-nearest neighbor or KNN is used as the proposed classifier. KNN is a classification algorithm based on the distance between the object and its neighbors. Its purpose is to classify the new object based on attributes. Furthermore, the K samples of the training data in KNN is a number of nearest neighbors that are included in the contribution of the voting process [5]. The number K depends on the case where it is applied. When the number K is large, the time and storage costs are higher. However, if it is small, the nearby meter will be extremely small due to the poor information [6]. It is important to find the best value of K, and, therefore, a trial-and-concept error needs to conducted [7].

The accuracy of the KNN algorithm is greatly influenced by the absence or presence of irrelevant features. It is also influenced by the weight of the feature, which is not equivalent to its relevance for classification [8]. In the training phase, this algorithm stores features and class vectors of the training data. In the testing phase, the same features are calculated for the testing data. When new data are entered, its classification is unclear. The distance from the new one to all the learning data vectors is calculated, and the closest number of K is taken. The new points are predicted to be included in the most classifications of these points [9].

The training data are projected into a multidimensional space in which each dimension contains a set of feature data. This space is divided into several sections consisting of a collection of learning data. A point in this space is marked as a certain class if the class is the most common classification in the closest K of that point. KNN is modeled in Figure 2.

K-nearest neighbor model sample.

Figure 2 displays two classes, A and B. Therefore, two Ks, K = 3 and K = 6. In addition, a test data is located right in the center of the circle. If the K used is 3, it is easy to see that the proximity of the data is more inclined toward class A. However, if the K used is 6, then the test data is simply recognized as class B because it has a greater closeness to class B. Neighbors are usually calculated based on distances, and the distance between two points can be calculated using certain distance metrics such as Euclidean, Chebychev, Minkowski, etc. [10,11].

2.2.2 Euclidean distance

The Euclidean distance is the most common distance metric used for KNN. It is a straight line distance between two data points (

The distance between two points is simply calculated by finding the root of squared difference in x and y. This formula is similar to the Pythagorean theorem formula, and, therefore, it is also known as the Pythagorean.

2.2.3 Chebychev distance

The Chebychev distance or chessboard distance or P ∞ metric is a distance metric defined on a vector space where the distance between points (

2.2.4 Minkowski distance

The Minkowski distance is a metric in a normed vector space, which can be considered as a generalization of both the Euclidean distance and the Manhattan distance. It is used as the dissimilarity measurement between two vectors where

The Minkowski distance is a generalized distance metric. The formula above can be manipulated by substituting “p” to calculate the distance between two data points in different ways. For the case of p = 2, the Minkowski distance gives the Euclidean distance. For the case of p = ∞, the Minkowski distance gives the Chebychev distance [14].

2.2.5 Weighted KNN

Weighted KNN is a modified version of nearest neighbor algorithm. One of the many issues that affect the performance of the KNN algorithm is the choice of the hyperparameter K, which is sometimes less representative. In order to overcome this issue, a weight variable is added to the distance calculation formula [15]. The weight is calculated by the reciprocal of the distance, as shown in equation (4).

Where

In this research, either unweighted or weighted models were applied to the three distance metrics proposed above so that a total of six algorithms will be compared.

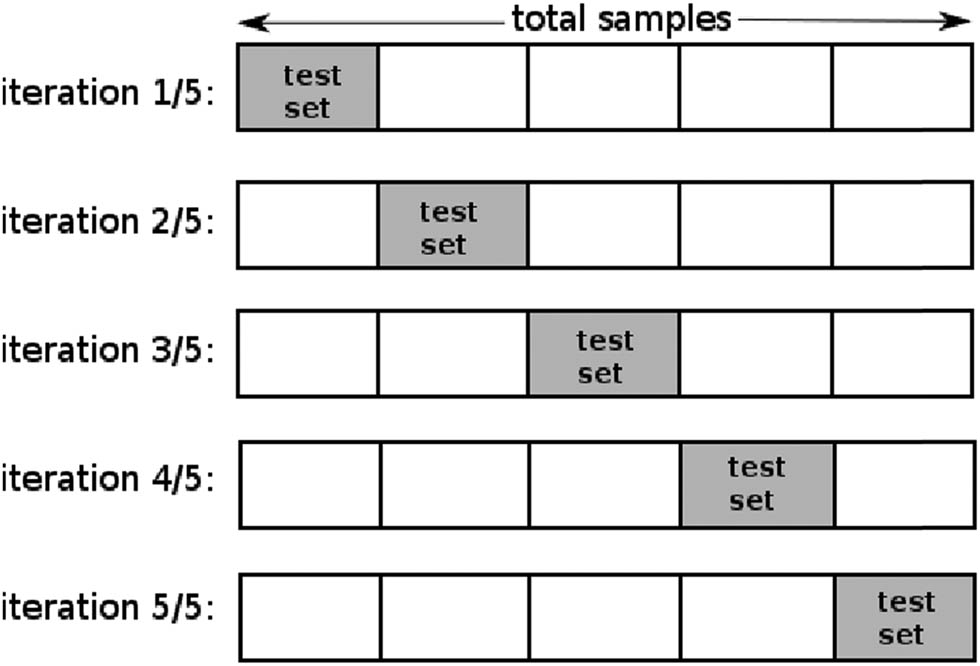

2.2.6 K-fold cross validation

The validation is vital in classification to ensure the model is clean, correct, and reliable. K-fold cross validation is used as a validation method. Furthermore, K-fold is one of the most common cross-validation methods by folding data to a number of K and repeating (iterating) the training and testing process as much as K [16]. Similarly, for every single iteration, onefold is used as the test set and the rest is used as the train set. The role as the test data takes turns in accordance with the order of the K index [1]. Figure 3 is the example for fivefold cross validation.

K-fold cross validation.

Figure 3 shows a set of data, which is divided into five segments or folds. In the first iteration, the first segment is used as the test data, and the number of test data set is 1/5 * n, where n is the total number of data set. Similarly, the other four segments are used as train set and then the second fold of data set is used as the test set, and the rest is used as the train set including the very first fold. This iteration is conducted five times as K = 5.

2.3 Data testing and validation

The data testing and validation are carried out in three stages. The first one is dividing the data into two parts, one is for training data and the rest is for testing data. Similarly, to be proportional, out of 1,450 feature data set, 1,160 objects are considered to be the training data and 290 objects as the testing data, and the selection of the training and testing classes was randomly chosen.

The next stage is testing three distance metrics to find out the best based on the most number of correctly predicted objects and the minimum K. Furthermore, each metric was tested weighted and unweighted in an increasing value of K neighborhood. This increased gradually starting from 0 and ending at 50. The metric with the highest predicted value and the lowest K value will be considered as the best. Line graphs of changes in the number of correctly predicted objects from these metrics are shown in Figure 4.

Line graphs of 50 K-nearest neighbor with Euclidean, Chebychev, and Minkowski distance.

Figure 4 shows six lines representing the sum of correctly predicted object for every distance metric. Y-axis represents the number of cells and X-axis represents the number of K neighborhood. Each metric has at least one K neighborhood value that is able to obtain the highest number of cells.

The results show that the unweighted Euclidean distance successfully identified 229 objects at K = 20 while the weighted Euclidean distance only obtained 220 objects at K = 11. Both unweighted Chebychev distance at K = 10 and weighted Chebychev distance at K = 27 correctly identified 235 objects. The unweighted Minkowski distance obtained 240 objects at K = 19 while the weighted Minkowski distance obtained the same result at K = 27. Therefore, unweighted Minkowski distance continued to be analyzed in the third stage.

The final stage is conducting a cross validation with the number of fold 5, which was performed on the unweighted Minkowski distance. Each fold contains 290 data that alternate in each iteration. This method is conducted to prevent the results from overfitting.

3 Results and discussion

The experimental results show that some data can be identified properly. Every data that has been tested, either correctly or incorrectly predicted, was counted and labeled as true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP), or false negative (FN). Furthermore, a TP is a result where the objects correctly predict the positive class. Similarly, a true negative is a result where the model correctly predicts the negative class. A false positive is a result where the model incorrectly predicts the positive class, and a false negative is a result where the model incorrectly predicts the negative class [17].

A confusion matrix is created to calculate the detailed accuracy, recall, and precision value from the best metric distance, the unweighted Minkowski distance. Accuracy is the ability of a classification model to match the actual value of the quantity measured [18]. The equation for calculating the accuracy is represented in equation (6).

Recall is the ability of a model to find all the relevant cases within a dataset [17]. The equation for calculating recall is represented in equation (7).

Precision is the ability of a classification model to identify only the relevant class label [17]. The equation for calculating precision is shown in equation (8).

The prediction results from 5-fold cross validation KNN with the unweighted Minkowski distance are shown in Table 4, and some mispredicted data are shown in Table 4. Misclassifications occurred because the features possessed by several cells were very similar to each other in such a way that they have very close degrees of neighborhood. Furthermore, these data were aggregated by category, i.e., TPs, TNs, FPs, and FNs. These results were written in a confusion matrix table.

Confusion matrix of KNN with unweighted Minkowski distance

| Actual values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloblast | Promyelocyte | Monoblast | Promonocyte | Megakaryoblast | Monocyte | ||

| Predicted values | Myeloblast | 160 | 1 | 54 | 22 | 3 | 0 |

| Promyelocyte | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Monoblast | 30 | 10 | 285 | 134 | 2 | 2 | |

| Promonocyte | 2 | 0 | 13 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Megakaryoblast | 3 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 717 | 0 | |

| Monocyte | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

The confusion matrix is subsequently used as a basis to calculate the value of the real accuracy, recall, and precision. Similarly, each class has the same accuracy in such a way that the total accuracy for KNN with unweighted Minkowski distance is 80.552%. The average recall and precision values obtained are 44.145% and 42.592%, respectively. Table 5 shows the detailed recall and precision values for each blood cells.

Recall and precision values of KNN with unweighted Minkowski distance

| Blood cells | Recall (%) | Precision (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Myeloblast | 82.0513 | 66.667 |

| Promyelocyte | 0 | 0 |

| Monoblast | 79.8319 | 61.5551 |

| Promonocyte | 3.681 | 28.5714 |

| Megakaryoblast | 99.3075 | 98.7603 |

| Monocyte | 0 | 0 |

| Average | 44.145 | 42.592 |

By inspecting the results in Table 5, it was concluded that the KNN with unweighted Minkowski distance metric provides optimal results for accuracy only. The value of recall and precision are pretty average. This is because some object classes were not identified.

4 Conclusion

Comparing the classification of white blood cells gives interesting results. Most of the 1,450 blood cell objects were correctly identified, and the error occurred because of the wide variety of variations in white blood cells. Even some cell types have not been identified, because they have similar characteristics, which make the classification process more difficult. The unweighted Minkowski distance’s accuracy is the highest among others, with a value of 80.552%. However, the moderate recall and precision values make it less suitable for practical purpose. The given suggestion for the future research is to consider increasing the amount of data acquired from other sources. It will increase the variety of objects which will consequently allow a better generalization to the implementations of the unweighted Minkowski distance.

Acknowledgment

Authors applied the FLAE approach for the sequence of authors.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Authors contribution: Nurcahya Pradana Taufik Prakisya conducted the software coding and prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors. Febri Liantoni made the conclusions. Puspanda Hatta created the model code. Yusfia Hafid Aristyagama carried out the data testing and validation. Andika Setiawan was responsible for data gathering and labeling.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from Medical and Health Research Ethic Comitee (MHREC), Faculty of Medicine Gadjah Mada University – Dr. Sardjito General Hostpital but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Medical and Health Research Ethic Comitee (MHREC), Faculty of Medicine Gadjah Mada University – Dr. Sardjito General Hostpital.

References

1 Harjoko A, Ratnaningsih T, Suryani E, Wiharto W, Palgunadi S, Prakisya NPT. Classification of acute myeloid leukemia subtypes M1, M2 and M3 using active contour without edge segmentation and momentum backpropagation artificial neural network. MATEC Web of Conferences; 2018.10.1051/matecconf/201815401041Search in Google Scholar

2 Suryani E, Wiharto W, Palgunadi S, Prakisya NPT. Classification of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML M2 and AML M3) using momentum back propagation from watershed distance transform segmented images. J Phys Conf Ser. Institute of Physics Publishing. 2017;801:012044.10.1088/1742-6596/801/1/012044Search in Google Scholar

3 Suryani E, Wiharto W, Palgunadi S, Putra YR. Cells identification of acute myeloid leukemia AML M0 and AML M1 using K-nearest neighbour based on morphological images. 2017 International Conference on Data and Software Engineering (ICoDSE); 2018 Jan. p. 1–6.10.1109/ICODSE.2017.8285851Search in Google Scholar

4 Setiawan A, Harjoko A, Ratnaningsih T, Suryani E, Wiharto W, Palgunadi S. Classification of cell types in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) of M4, M5 and M7 subtypes with support vector machine classifier. 2018 International Conference on Information and Communications Technology (ICOIACT); 2018. p. 45–9.10.1109/ICOIACT.2018.8350822Search in Google Scholar

5 Li G, Zhang J. Music personalized recommendation system based on improved KNN algorithm. 2018 IEEE 3rd Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC); 2018. p. 777–81.10.1109/IAEAC.2018.8577483Search in Google Scholar

6 Vaishnnave MP, Suganya Devi K, Srinivasan P, Arutperumjothi G. Detection and classification of groundnut leaf diseases using KNN classifier. 2019 IEEE International Conference on System, Computation, Automation and Networking (ICSCAN); 2019. p. 1–5.10.1109/ICSCAN.2019.8878733Search in Google Scholar

7 Zhang N, Karimoune W, Thompson L, Dang H. A between-class overlapping coherence-based algorithm in KNN classification. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC); 2017 Jan. p. 572–7.10.1109/SMC.2017.8122667Search in Google Scholar

8 Wisnu H, Afif M, Ruldevyani Y. Sentiment analysis on customer satisfaction of digital payment in Indonesia: a comparative study using KNN and Naïve Bayes sentiment analysis on customer satisfaction of digital payment in Indonesia: a comparative study using KNN and Naïve Bayes. J Phys Conf Ser. Institute of Physics Publishing. 2020:1444:012034.10.1088/1742-6596/1444/1/012034Search in Google Scholar

9 Harijanto B, Amalia EL, Mentari M. Recognition of the character on the map captured by the camera using K-nearest neighbor. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Vol. 732; 2020. p. 012043.10.1088/1757-899X/732/1/012043Search in Google Scholar

10 Williams J, Li Y. Comparative study of distance functions for nearest neighbors. Advanced techniques in computing sciences and software engineering. Dordrecht: Springer; 2010 Jan. p. 79–84.10.1007/978-90-481-3660-5_14Search in Google Scholar

11 Zaman FHK, Yassin IM, Shafie AA. Ensembles of large margin nearest neighbour with grouped lateral patch arrangement for face classification. 2016 IEEE 4th International Symposium on Robotics and Intelligent Sensors (IRIS); 2017 Dec. p. 6–12.10.1109/IRIS.2016.8066058Search in Google Scholar

12 Singh A, Pandey B. An Euclidean distance based KNN computational method for assessing degree of liver damage. 2016 International Conference on Inventive Computation Technologies (ICICT); 2016.10.1109/INVENTIVE.2016.7823222Search in Google Scholar

13 Klimo M, Škvarek O, Tarabek P, Šuch O, Hrabovsky J. Nearest neighbor classification in Minkowski quasi-metric space. 2018 World Symposium on Digital Intelligence for Systems and Machines (DISA); 2018. p. 227–32.10.1109/DISA.2018.8490622Search in Google Scholar

14 Khaldi B, Harrou F, Cherif F, Sun Y. Improving robots swarm aggregation performance through the Minkowski distance function. 2020 6th International Conference on Mechatronics and Robotics Engineering (ICMRE); 2020. p. 87–91.10.1109/ICMRE49073.2020.9064998Search in Google Scholar

15 Fan GF, Guo YH, Zheng JM, Hong WC. Application of the weighted k-nearest neighbor algorithm for short-term load forecasting. Energies. 2019;12(5):916.10.3390/en12050916Search in Google Scholar

16 Yadav S, Shukla S. Analysis of k-fold cross-validation over hold-out validation on colossal datasets for quality classification. 2016 IEEE 6th International conference on advanced computing (IACC); 2016. p. 78–83.10.1109/IACC.2016.25Search in Google Scholar

17 Rajpurohit S, Patil S, Choudhary N, Gavasane S, Kosamkar P. Identification of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in microscopic blood image using image processing and machine learning algorithms. 2018 International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics (ICACCI); 2018. p. 2359–63.10.1109/ICACCI.2018.8554576Search in Google Scholar

18 Uddhavraokatkar B, Barkade V. Prediction of isolated erythrocytes formation from compound erythrocytes in blood cells images. 2017 International Conference on Computing, Communication, Control and Automation (ICCUBEA); 2018. p. 5.10.1109/ICCUBEA.2017.8463823Search in Google Scholar

© 2021 Nurcahya Pradana Taufik Prakisya et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Electrochemical studies of the synergistic combination effect of thymus mastichina and illicium verum essential oil extracts on the corrosion inhibition of low carbon steel in dilute acid solution

- Adoption of Business Intelligence to Support Cost Accounting Based Financial Systems — Case Study of XYZ Company

- Techno-Economic Feasibility Analysis of a Hybrid Renewable Energy Supply Options for University Buildings in Saudi Arabia

- Optimized design of a semimetal gasket operating in flange-bolted joints

- Behavior of non-reinforced and reinforced green mortar with fibers

- Field measurement of contact forces on rollers for a large diameter pipe conveyor

- Development of Smartphone-Controlled Hand and Arm Exoskeleton for Persons with Disability

- Investigation of saturation flow rate using video camera at signalized intersections in Jordan

- The features of Ni2MnIn polycrystalline Heusler alloy thin films formation by pulsed laser deposition

- Selection of a workpiece clamping system for computer-aided subtractive manufacturing of geometrically complex medical models

- Development of Solar-Powered Water Pump with 3D Printed Impeller

- Identifying Innovative Reliable Criteria Governing the Selection of Infrastructures Construction Project Delivery Systems

- Kinetics of Carbothermal Reduction Process of Different Size Phosphate Rocks

- Plastic forming processes of transverse non-homogeneous composite metallic sheets

- Accelerated aging of WPCs Based on Polypropylene and Birch plywood Sanding Dust

- Effect of water flow and depth on fatigue crack growth rate of underwater wet welded low carbon steel SS400

- Non-invasive attempts to extinguish flames with the use of high-power acoustic extinguisher

- Filament wound composite fatigue mechanisms investigated with full field DIC strain monitoring

- Structural Timber In Compartment Fires – The Timber Charring and Heat Storage Model

- Technical and economic aspects of starting a selected power unit at low ambient temperatures

- Car braking effectiveness after adaptation for drivers with motor dysfunctions

- Adaptation to driver-assistance systems depending on experience

- A SIMULINK implementation of a vector shift relay with distributed synchronous generator for engineering classes

- Evaluation of measurement uncertainty in a static tensile test

- Errors in documenting the subsoil and their impact on the investment implementation: Case study

- Comparison between two calculation methods for designing a stand-alone PV system according to Mosul city basemap

- Reduction of transport-related air pollution. A case study based on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the level of NOx emissions in the city of Krakow

- Driver intervention performance assessment as a key aspect of L3–L4 automated vehicles deployment

- A new method for solving quadratic fractional programming problem in neutrosophic environment

- Effect of fish scales on fabrication of polyester composite material reinforcements

- Impact of the operation of LNG trucks on the environment

- The effectiveness of the AEB system in the context of the safety of vulnerable road users

- Errors in controlling cars cause tragic accidents involving motorcyclists

- Deformation of designed steel plates: An optimisation of the side hull structure using the finite element approach

- Thermal-strength analysis of a cross-flow heat exchanger and its design improvement

- Effect of thermal collector configuration on the photovoltaic heat transfer performance with 3D CFD modeling

- Experimental identification of the subjective reception of external stimuli during wheelchair driving

- Failure analysis of motorcycle shock breakers

- Experimental analysis of nonlinear characteristics of absorbers with wire rope isolators

- Experimental tests of the antiresonance vibratory mill of a sectional movement trajectory

- Experimental and theoretical investigation of CVT rubber belt vibrations

- Is the cubic parabola really the best railway transition curve?

- Transport properties of the new vibratory conveyor at operations in the resonance zone

- Assessment of resistance to permanent deformations of asphalt mixes of low air void content

- COVID-19 lockdown impact on CERN seismic station ambient noise levels

- Review Articles

- FMEA method in operational reliability of forest harvesters

- Examination of preferences in the field of mobility of the city of Pila in terms of services provided by the Municipal Transport Company in Pila

- Enhancement stability and color fastness of natural dye: A review

- Special Issue: ICE-SEAM 2019 - Part II

- Lane Departure Warning Estimation Using Yaw Acceleration

- Analysis of EMG Signals during Stance and Swing Phases for Controlling Magnetorheological Brake applications

- Sensor Number Optimization Using Neural Network for Ankle Foot Orthosis Equipped with Magnetorheological Brake

- Special Issue: Recent Advances in Civil Engineering - Part II

- Comparison of STM’s reliability system on the example of selected element

- Technical analysis of the renovation works of the wooden palace floors

- Special Issue: TRANSPORT 2020

- Simulation assessment of the half-power bandwidth method in testing shock absorbers

- Predictive analysis of the impact of the time of day on road accidents in Poland

- User’s determination of a proper method for quantifying fuel consumption of a passenger car with compression ignition engine in specific operation conditions

- Analysis and assessment of defectiveness of regulations for the yellow signal at the intersection

- Streamlining possibility of transport-supply logistics when using chosen Operations Research techniques

- Permissible distance – safety system of vehicles in use

- Study of the population in terms of knowledge about the distance between vehicles in motion

- UAVs in rail damage image diagnostics supported by deep-learning networks

- Exhaust emissions of buses LNG and Diesel in RDE tests

- Measurements of urban traffic parameters before and after road reconstruction

- The use of deep recurrent neural networks to predict performance of photovoltaic system for charging electric vehicles

- Analysis of dangers in the operation of city buses at the intersections

- Psychological factors of the transfer of control in an automated vehicle

- Testing and evaluation of cold-start emissions from a gasoline engine in RDE test at two different ambient temperatures

- Age and experience in driving a vehicle and psychomotor skills in the context of automation

- Consumption of gasoline in vehicles equipped with an LPG retrofit system in real driving conditions

- Laboratory studies of the influence of the working position of the passenger vehicle air suspension on the vibration comfort of children transported in the child restraint system

- Route optimization for city cleaning vehicle

- Efficiency of electric vehicle interior heating systems at low ambient temperatures

- Model-based imputation of sound level data at thoroughfare using computational intelligence

- Research on the combustion process in the Fiat 1.3 Multijet engine fueled with rapeseed methyl esters

- Overview of the method and state of hydrogenization of road transport in the world and the resulting development prospects in Poland

- Tribological characteristics of polymer materials used for slide bearings

- Car reliability analysis based on periodic technical tests

- Special Issue: Terotechnology 2019 - Part II

- DOE Application for Analysis of Tribological Properties of the Al2O3/IF-WS2 Surface Layers

- The effect of the impurities spaces on the quality of structural steel working at variable loads

- Prediction of the parameters and the hot open die elongation forging process on an 80 MN hydraulic press

- Special Issue: AEVEC 2020

- Vocational Student's Attitude and Response Towards Experiential Learning in Mechanical Engineering

- Virtual Laboratory to Support a Practical Learning of Micro Power Generation in Indonesian Vocational High Schools

- The impacts of mediating the work environment on the mode choice in work trips

- Utilization of K-nearest neighbor algorithm for classification of white blood cells in AML M4, M5, and M7

- Car braking effectiveness after adaptation for drivers with motor dysfunctions

- Case study: Vocational student’s knowledge and awareness level toward renewable energy in Indonesia

- Contribution of collaborative skill toward construction drawing skill for developing vocational course

- Special Issue: Annual Engineering and Vocational Education Conference - Part II

- Vocational teachers’ perspective toward Technological Pedagogical Vocational Knowledge

- Special Issue: ICIMECE 2020 - Part I

- Profile of system and product certification as quality infrastructure in Indonesia

- Prediction Model of Magnetorheological (MR) Fluid Damper Hysteresis Loop using Extreme Learning Machine Algorithm

- A review on the fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printing: Filament processing, materials, and printing parameters

- Facile rheological route method for LiFePO4/C cathode material production

- Mosque design strategy for energy and water saving

- Epoxy resins thermosetting for mechanical engineering

- Estimating the potential of wind energy resources using Weibull parameters: A case study of the coastline region of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

- Special Issue: CIRMARE 2020

- New trends in visual inspection of buildings and structures: Study for the use of drones

- Special Issue: ISERT 2021

- Alleviate the contending issues in network operating system courses: Psychomotor and troubleshooting skill development with Raspberry Pi

- Special Issue: Actual Trends in Logistics and Industrial Engineering - Part II

- The Physical Internet: A means towards achieving global logistics sustainability

- Special Issue: Modern Scientific Problems in Civil Engineering - Part I

- Construction work cost and duration analysis with the use of agent-based modelling and simulation

- Corrosion rate measurement for steel sheets of a fuel tank shell being in service

- The influence of external environment on workers on scaffolding illustrated by UTCI

- Allocation of risk factors for geodetic tasks in construction schedules

- Pedestrian fatality risk as a function of tram impact speed

- Technological and organizational problems in the construction of the radiation shielding concrete and suggestions to solve: A case study

- Finite element analysis of train speed effect on dynamic response of steel bridge

- New approach to analysis of railway track dynamics – Rail head vibrations

- Special Issue: Trends in Logistics and Production for the 21st Century - Part I

- Design of production lines and logistic flows in production

- The planning process of transport tasks for autonomous vans

- Modeling of the two shuttle box system within the internal logistics system using simulation software

- Implementation of the logistics train in the intralogistics system: A case study

- Assessment of investment in electric buses: A case study of a public transport company

- Assessment of a robot base production using CAM programming for the FANUC control system

- Proposal for the flow of material and adjustments to the storage system of an external service provider

- The use of numerical analysis of the injection process to select the material for the injection molding

- Economic aspect of combined transport

- Solution of a production process with the application of simulation: A case study

- Speedometer reliability in regard to road traffic sustainability

- Design and construction of a scanning stand for the PU mini-acoustic sensor

- Utilization of intelligent vehicle units for train set dispatching

- Special Issue: ICRTEEC - 2021 - Part I

- LVRT enhancement of DFIG-driven wind system using feed-forward neuro-sliding mode control

- Special Issue: Automation in Finland 2021 - Part I

- Prediction of future paths of mobile objects using path library

- Model predictive control for a multiple injection combustion model

- Model-based on-board post-injection control development for marine diesel engine

- Intelligent temporal analysis of coronavirus statistical data

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Electrochemical studies of the synergistic combination effect of thymus mastichina and illicium verum essential oil extracts on the corrosion inhibition of low carbon steel in dilute acid solution

- Adoption of Business Intelligence to Support Cost Accounting Based Financial Systems — Case Study of XYZ Company

- Techno-Economic Feasibility Analysis of a Hybrid Renewable Energy Supply Options for University Buildings in Saudi Arabia

- Optimized design of a semimetal gasket operating in flange-bolted joints

- Behavior of non-reinforced and reinforced green mortar with fibers

- Field measurement of contact forces on rollers for a large diameter pipe conveyor

- Development of Smartphone-Controlled Hand and Arm Exoskeleton for Persons with Disability

- Investigation of saturation flow rate using video camera at signalized intersections in Jordan

- The features of Ni2MnIn polycrystalline Heusler alloy thin films formation by pulsed laser deposition

- Selection of a workpiece clamping system for computer-aided subtractive manufacturing of geometrically complex medical models

- Development of Solar-Powered Water Pump with 3D Printed Impeller

- Identifying Innovative Reliable Criteria Governing the Selection of Infrastructures Construction Project Delivery Systems

- Kinetics of Carbothermal Reduction Process of Different Size Phosphate Rocks

- Plastic forming processes of transverse non-homogeneous composite metallic sheets

- Accelerated aging of WPCs Based on Polypropylene and Birch plywood Sanding Dust

- Effect of water flow and depth on fatigue crack growth rate of underwater wet welded low carbon steel SS400

- Non-invasive attempts to extinguish flames with the use of high-power acoustic extinguisher

- Filament wound composite fatigue mechanisms investigated with full field DIC strain monitoring

- Structural Timber In Compartment Fires – The Timber Charring and Heat Storage Model

- Technical and economic aspects of starting a selected power unit at low ambient temperatures

- Car braking effectiveness after adaptation for drivers with motor dysfunctions

- Adaptation to driver-assistance systems depending on experience

- A SIMULINK implementation of a vector shift relay with distributed synchronous generator for engineering classes

- Evaluation of measurement uncertainty in a static tensile test

- Errors in documenting the subsoil and their impact on the investment implementation: Case study

- Comparison between two calculation methods for designing a stand-alone PV system according to Mosul city basemap

- Reduction of transport-related air pollution. A case study based on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the level of NOx emissions in the city of Krakow

- Driver intervention performance assessment as a key aspect of L3–L4 automated vehicles deployment

- A new method for solving quadratic fractional programming problem in neutrosophic environment

- Effect of fish scales on fabrication of polyester composite material reinforcements

- Impact of the operation of LNG trucks on the environment

- The effectiveness of the AEB system in the context of the safety of vulnerable road users

- Errors in controlling cars cause tragic accidents involving motorcyclists

- Deformation of designed steel plates: An optimisation of the side hull structure using the finite element approach

- Thermal-strength analysis of a cross-flow heat exchanger and its design improvement

- Effect of thermal collector configuration on the photovoltaic heat transfer performance with 3D CFD modeling

- Experimental identification of the subjective reception of external stimuli during wheelchair driving

- Failure analysis of motorcycle shock breakers

- Experimental analysis of nonlinear characteristics of absorbers with wire rope isolators

- Experimental tests of the antiresonance vibratory mill of a sectional movement trajectory

- Experimental and theoretical investigation of CVT rubber belt vibrations

- Is the cubic parabola really the best railway transition curve?

- Transport properties of the new vibratory conveyor at operations in the resonance zone

- Assessment of resistance to permanent deformations of asphalt mixes of low air void content

- COVID-19 lockdown impact on CERN seismic station ambient noise levels

- Review Articles

- FMEA method in operational reliability of forest harvesters

- Examination of preferences in the field of mobility of the city of Pila in terms of services provided by the Municipal Transport Company in Pila

- Enhancement stability and color fastness of natural dye: A review

- Special Issue: ICE-SEAM 2019 - Part II

- Lane Departure Warning Estimation Using Yaw Acceleration

- Analysis of EMG Signals during Stance and Swing Phases for Controlling Magnetorheological Brake applications

- Sensor Number Optimization Using Neural Network for Ankle Foot Orthosis Equipped with Magnetorheological Brake

- Special Issue: Recent Advances in Civil Engineering - Part II

- Comparison of STM’s reliability system on the example of selected element

- Technical analysis of the renovation works of the wooden palace floors

- Special Issue: TRANSPORT 2020

- Simulation assessment of the half-power bandwidth method in testing shock absorbers

- Predictive analysis of the impact of the time of day on road accidents in Poland

- User’s determination of a proper method for quantifying fuel consumption of a passenger car with compression ignition engine in specific operation conditions

- Analysis and assessment of defectiveness of regulations for the yellow signal at the intersection

- Streamlining possibility of transport-supply logistics when using chosen Operations Research techniques

- Permissible distance – safety system of vehicles in use

- Study of the population in terms of knowledge about the distance between vehicles in motion

- UAVs in rail damage image diagnostics supported by deep-learning networks

- Exhaust emissions of buses LNG and Diesel in RDE tests

- Measurements of urban traffic parameters before and after road reconstruction

- The use of deep recurrent neural networks to predict performance of photovoltaic system for charging electric vehicles

- Analysis of dangers in the operation of city buses at the intersections

- Psychological factors of the transfer of control in an automated vehicle

- Testing and evaluation of cold-start emissions from a gasoline engine in RDE test at two different ambient temperatures

- Age and experience in driving a vehicle and psychomotor skills in the context of automation

- Consumption of gasoline in vehicles equipped with an LPG retrofit system in real driving conditions

- Laboratory studies of the influence of the working position of the passenger vehicle air suspension on the vibration comfort of children transported in the child restraint system

- Route optimization for city cleaning vehicle

- Efficiency of electric vehicle interior heating systems at low ambient temperatures

- Model-based imputation of sound level data at thoroughfare using computational intelligence

- Research on the combustion process in the Fiat 1.3 Multijet engine fueled with rapeseed methyl esters

- Overview of the method and state of hydrogenization of road transport in the world and the resulting development prospects in Poland

- Tribological characteristics of polymer materials used for slide bearings

- Car reliability analysis based on periodic technical tests

- Special Issue: Terotechnology 2019 - Part II

- DOE Application for Analysis of Tribological Properties of the Al2O3/IF-WS2 Surface Layers

- The effect of the impurities spaces on the quality of structural steel working at variable loads

- Prediction of the parameters and the hot open die elongation forging process on an 80 MN hydraulic press

- Special Issue: AEVEC 2020

- Vocational Student's Attitude and Response Towards Experiential Learning in Mechanical Engineering

- Virtual Laboratory to Support a Practical Learning of Micro Power Generation in Indonesian Vocational High Schools

- The impacts of mediating the work environment on the mode choice in work trips

- Utilization of K-nearest neighbor algorithm for classification of white blood cells in AML M4, M5, and M7

- Car braking effectiveness after adaptation for drivers with motor dysfunctions

- Case study: Vocational student’s knowledge and awareness level toward renewable energy in Indonesia

- Contribution of collaborative skill toward construction drawing skill for developing vocational course

- Special Issue: Annual Engineering and Vocational Education Conference - Part II

- Vocational teachers’ perspective toward Technological Pedagogical Vocational Knowledge

- Special Issue: ICIMECE 2020 - Part I

- Profile of system and product certification as quality infrastructure in Indonesia

- Prediction Model of Magnetorheological (MR) Fluid Damper Hysteresis Loop using Extreme Learning Machine Algorithm

- A review on the fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printing: Filament processing, materials, and printing parameters

- Facile rheological route method for LiFePO4/C cathode material production

- Mosque design strategy for energy and water saving

- Epoxy resins thermosetting for mechanical engineering

- Estimating the potential of wind energy resources using Weibull parameters: A case study of the coastline region of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

- Special Issue: CIRMARE 2020

- New trends in visual inspection of buildings and structures: Study for the use of drones

- Special Issue: ISERT 2021

- Alleviate the contending issues in network operating system courses: Psychomotor and troubleshooting skill development with Raspberry Pi

- Special Issue: Actual Trends in Logistics and Industrial Engineering - Part II

- The Physical Internet: A means towards achieving global logistics sustainability

- Special Issue: Modern Scientific Problems in Civil Engineering - Part I

- Construction work cost and duration analysis with the use of agent-based modelling and simulation

- Corrosion rate measurement for steel sheets of a fuel tank shell being in service

- The influence of external environment on workers on scaffolding illustrated by UTCI

- Allocation of risk factors for geodetic tasks in construction schedules

- Pedestrian fatality risk as a function of tram impact speed

- Technological and organizational problems in the construction of the radiation shielding concrete and suggestions to solve: A case study

- Finite element analysis of train speed effect on dynamic response of steel bridge

- New approach to analysis of railway track dynamics – Rail head vibrations

- Special Issue: Trends in Logistics and Production for the 21st Century - Part I

- Design of production lines and logistic flows in production

- The planning process of transport tasks for autonomous vans

- Modeling of the two shuttle box system within the internal logistics system using simulation software

- Implementation of the logistics train in the intralogistics system: A case study

- Assessment of investment in electric buses: A case study of a public transport company

- Assessment of a robot base production using CAM programming for the FANUC control system

- Proposal for the flow of material and adjustments to the storage system of an external service provider

- The use of numerical analysis of the injection process to select the material for the injection molding

- Economic aspect of combined transport

- Solution of a production process with the application of simulation: A case study

- Speedometer reliability in regard to road traffic sustainability

- Design and construction of a scanning stand for the PU mini-acoustic sensor

- Utilization of intelligent vehicle units for train set dispatching

- Special Issue: ICRTEEC - 2021 - Part I

- LVRT enhancement of DFIG-driven wind system using feed-forward neuro-sliding mode control

- Special Issue: Automation in Finland 2021 - Part I

- Prediction of future paths of mobile objects using path library

- Model predictive control for a multiple injection combustion model

- Model-based on-board post-injection control development for marine diesel engine

- Intelligent temporal analysis of coronavirus statistical data