Abstract

Cultivation of human nasal septal chondrocytes in a self-established automated bioreactor system with a new designed reactor glass vessel and the results of a computational fluid dynamics model are presented. The first results show the effect of a homogeneous fluidic condition of the continuous medium flow and the resulting stresses on the scaffolds’ surface and their influence on the migration of the cells into the scaffold matrix under these conditions. For this purpose computational models, generated with the computational fluid dynamics software STAR-CCM+, and the results of alcian blue staining for newly synthesized sulphated glycosaminoglycans have been compared during cultivation in the new and a first version of the glass reactor vessel with inhomogeneous fluidic conditions, with the same automated bioreactor system and under similar cultivation conditions.

1 Introduction

Defects of septal or auricular facial cartilage are congenital or are caused by trauma or cancer. For reconstruction, biocompatible artificial implants or autologous donor tissue, harvested from the ribs or concha are used [1]. The advantage of the former method is e.g. limitless supply of implants [2], of the latter the lack of rejection reaction. Both have certain disadvantages such as extrusion, infection or donor site morbidity [3].

To solve those problems tissue engineering is a promising approach. In this approach, the patient’s own cells are seeded on a so-called scaffold, a three-dimensional porous structure made of a biocompatible material, and so cartilage can grow in a predefined shape [4]. To offer best possible conditions to the cells, different kinds of bioreactors had been established over the past years [5], [6]. Depending on the type of cultivated cells or intended type of cartilage different varieties of stresses and nutrition supply are necessary to lead to the desired results. To get an idea of these stresses the cells are exposed to or of the fluid dynamics in the bioreactor, computational modelling e.g. with CFD simulations can be used [7].

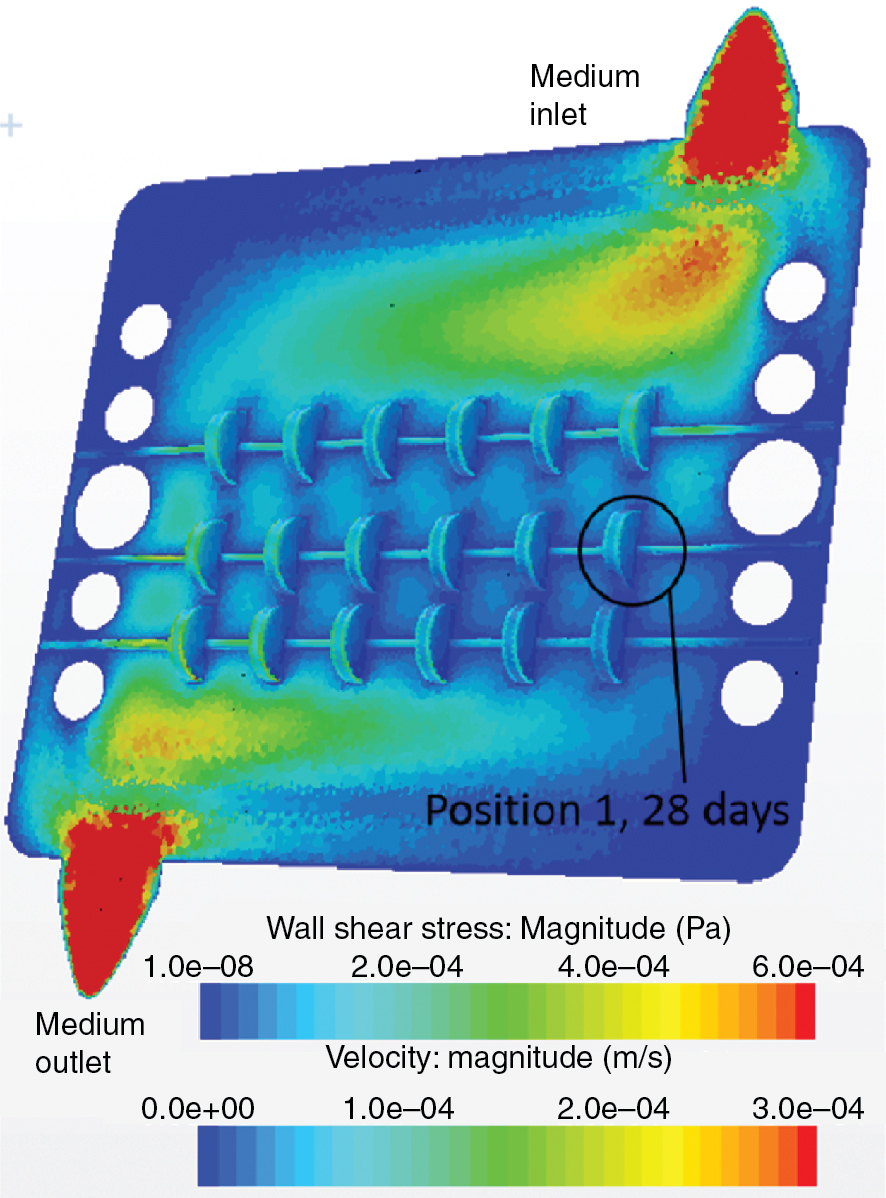

The outcome of the CFD modelling for the first version of the glass vessel of the established bioreactor system is presented in Figure 1. It shows inhomogeneous fluidic conditions and the resulting inhomogeneous wall shear stresses on the scaffolds’ surface. A detailed description of the established bioreactor system with the first version of the glass vessel and first results of cultivations can be found in [8].

CFD model of the former glass reactor vessel with the speared scaffolds on the wires during continuous medium flow of 2 ml/min during cultivation. It shows the velocity magnitude of the media on its way from the inlet to the outlet and the wall shear stress on scaffolds’ surface.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Automated bioreactor system

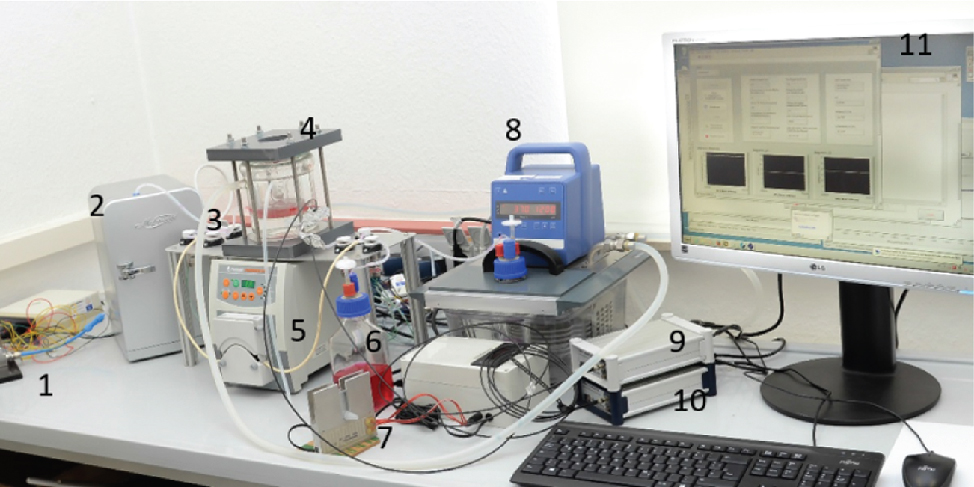

The bioreactor system presented here (Figure 2) consists of several components which are necessary to realize ideal cultivation conditions for the cells and the automatic sequence control of the whole system controlled by a self-established operating program via LabVIEW 2014 (National Instruments, TX, USA).

Photograph of the complete bioreactor system during a cultivation of populated scaffolds. Following components are contained: 1. Mass flow controller for gassing, 2. Refrigerator with fresh medium reservoir, 3. 6 Pinch valves for the media flow regulation, 4. Glass vessel bioreactor, 5. Peristaltic pump, 6. Bottle for medium waste, 7. Heating unit for exhaust gas filter, 8. Water bath with glass bottle for medium preheating, 9. & 10. Fibre optic transmitters for O2 and pH measurement, 11. Control PC.

This system offers the opportunity to control and regulate most of the environmental conditions like gassing, medium flow and medium exchange, heating of the bioreactor vessel and the non-invasive optical measurement of O2 and pH in the medium.

For that purpose, the glass vessel has a double jacket for the heating and contains inlets and outlets for the gassing and medium flow. Inside this vessel are two removable flow conducting elements, one after the medium inlet and one in front of the medium outlet, which lead to a homogeneous medium flow inside the vessel. Two mobile displacement devices for the medium can also be built in on demand. The dimension of the glass vessel’s cultivation chamber is 80 mm in diameter and could be implemented with an attachment for three wires or another attachment for auricular shaped scaffolds.

All further components of the system are fully described in [8].

2.2 Cells, scaffolds and media

Human primary nasal septal chondrocytes, obtained during routine surgeries in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology at the University Medical Center Ulm, were seeded on scaffolds made of sterile and processed porcine nasal septal cartilage, prepared at the Institute of Bioprocess Engineering of the University of Erlangen, with a diameter of 5 mm and 1 mm thickness. More detailed information about pre-treatment and preparation of the cells and scaffolds are reported in [9], [10].

The medium used here was StemMACS ChondroDiff Media human, a chondrocyte differentiation medium, from Miltenyi Biotec GmbH (Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).

2.3 Cell seeding

After 4 days of cultivation in monolayer culture, the cells reached subconfluence at 80–90% and a cell suspension with a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml was produced. Subsequently, each scaffold was seeded with about 1 × 106 cells and incubated in standard basal culture medium at 37°C with 5% CO2 under humidified conditions for about 1 h to allow cell adhesion. More detailed information is presented in [9], [10].

2.4 Cultivation conditions

The cultivation of the seeded scaffolds was performed in the automated bioreactor system for 6 weeks. Six scaffolds were placed on each of three Kirschner wires with diameters of 0.6 mm. Every 2 weeks, one wire was removed for qualitative and quantitative analysis of the corresponding six scaffolds. The temperature was 37°C, the pre-mixed gas consisted of 5% CO2, 20% O2 and 75% N2 and the flow rate of the media was 2 ml/min. The automated medium exchange was performed twice a week with a flow rate of 20 ml/min, exchanging 2/3 of the total volume.

2.5 CFD

For a first impression about the stresses on the scaffolds’ surface and the fluid flow characteristic a CFD modelling was performed. This was performed with the software STAR-CCM+ version 9.06.011 from CD-adapco (Melville, NY, USA) find a correlation between the computational results and laboratory analyses. The software ran on an iCore 5 PC with 3.2 GHz and 32 GB Ram.

2.6 Histology and immunohistochemistry

As further qualitative analysis, histological (alcian blue) and immunohistochemical detection methods (IHC) of newly synthesized sulphated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) such as aggrecan were performed. In addition IHC was also performed for collagen type I and II. Additional data are given in [9], [10].

3 Results

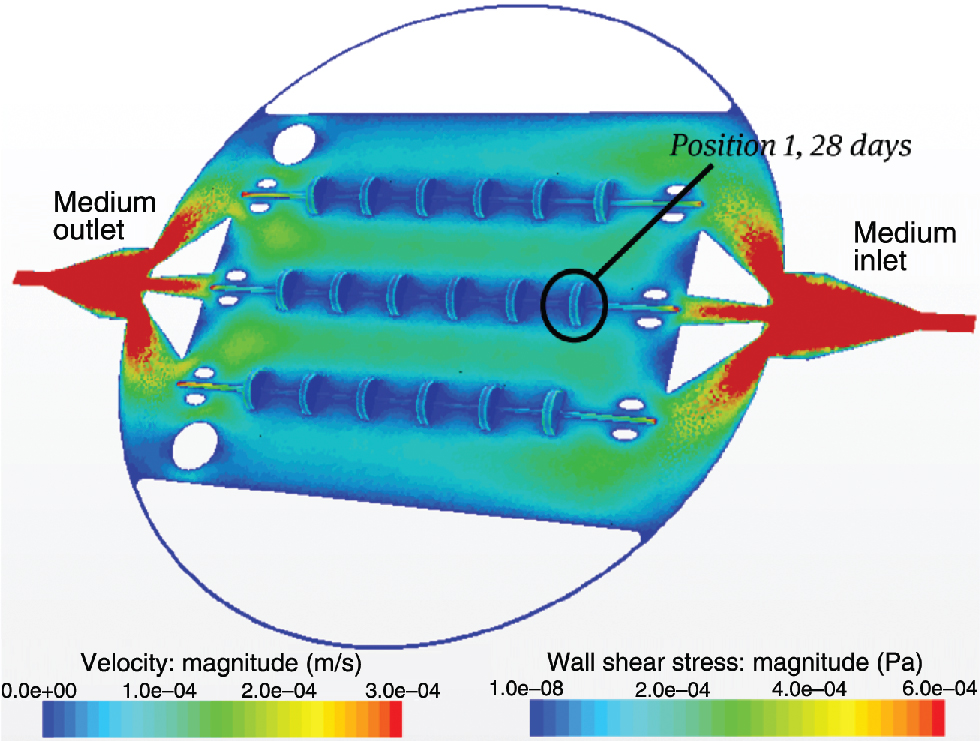

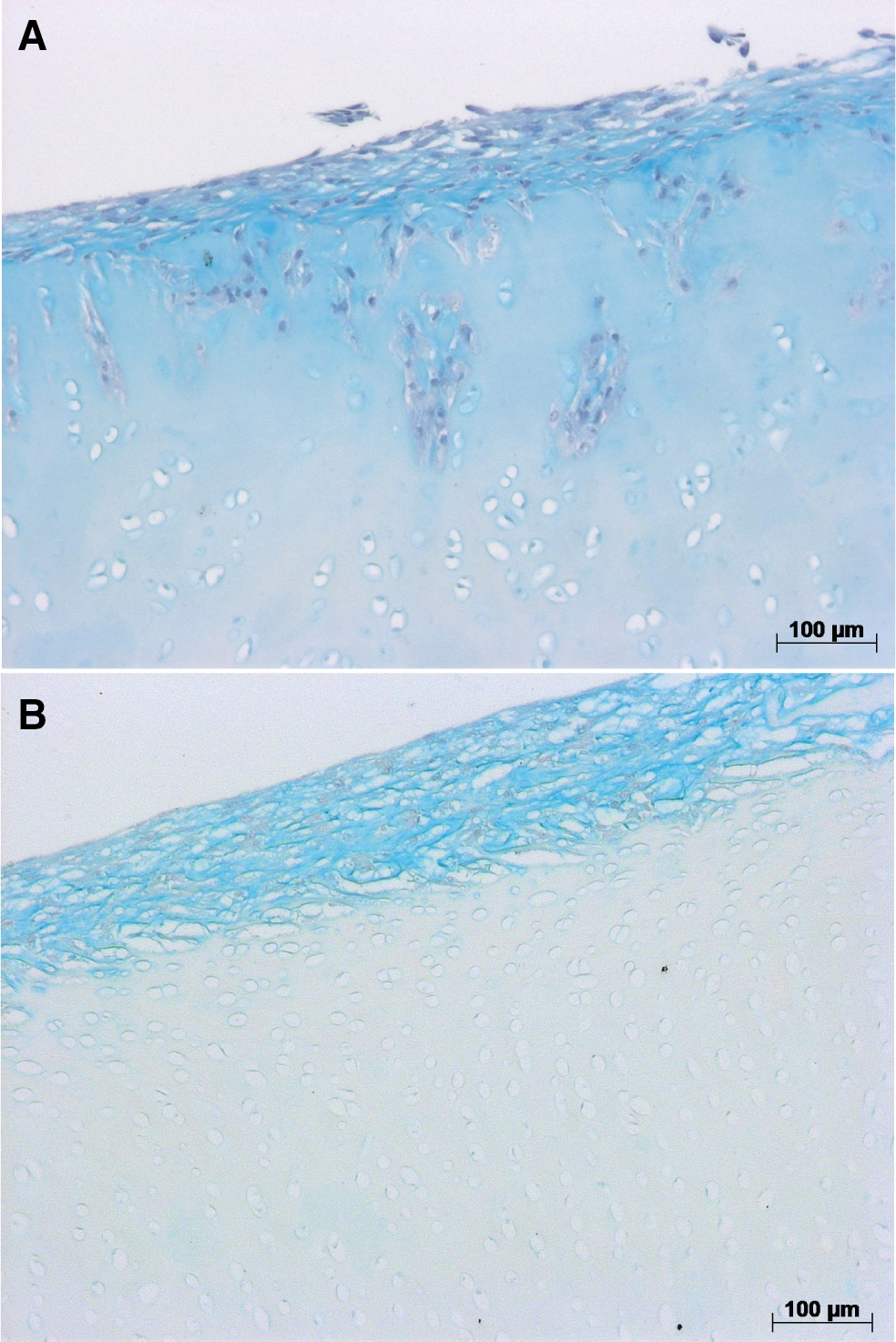

The CFD model in Figure 3 illustrates the velocity magnitude of the continuous medium flow during the cultivation in the reactor vessel on its way from the medium inlet to the medium outlet. The model also depicts the wall shear stress on the scaffolds’ surface resulting from the continuous medium flow. Figure 4A and Figure 4B present the results of the alcian blue staining visualising sulphated GAGs. By the blue staining of the newly synthesized sulphated GAGs the migration of the chondrocytes into the matrix of the scaffolds is clearly representable. Figure 4 demonstrates the alcian blue staining for scaffolds at position 1 after 28 days of cultivation in the (A) newly established reactor vessel in contrast to (B) in the former vessel. These two scaffolds have been chosen because of their similar position in the two different reactor vessels to show a potential difference in cell migration. In the new vessel the cells migrate into the matrix and generate a superficial cell layer on the scaffold surface which demonstrates the presence of newly synthesized GAGs. Cells in the former vessel are able to generate the superficial layer and produce new GAGs as well, but show no migration behaviour. These differences in cell migration might result from the different flow conditions and consequential stresses on the scaffolds’ surface.

CFD model of the new glass reactor vessel with the speared scaffolds on the wires during continuous medium flow of 2 ml/min during cultivation. It shows the velocity magnitude of the media on its way from the inlet to the outlet and the wall shear stress on scaffolds’ surface.

(A) Results of alcian blue staining for newly synthesized sulphated GAGs after 28 days of cultivation at position 1 in the new reactor vessel. (B) Results of alcian blue staining for newly synthesized sulphated GAGs after 28 days of cultivation at position 1 in the former reactor vessel. The comparison reflects that in (A) the migration of the chondrocytes into the scaffold matrix is deeper and more GAG was produced in the inner region of the scaffold.

4 Discussion and conclusion

The comparison of the computational results of the former (Figure 1) and new (Figure 3) bioreactor glass vessel proves clearly that the medium flow during continuous flow is more homogeneous in the new vessel which might lead to better results concerning the intended migration of chondrocytes into the scaffold matrices. This homogeneous flow also leads to a better nutrient supply and waste removal from the cells, also in deeper structures of the scaffold matrix. The comparison of Figure 4A to Figure 4B reveals that the cells on the scaffold in the new vessel, with optimized geometry, show better migration behaviour than the one in the former vessel on comparable positions in the bioreactor after the same duration of cultivation. The difference in migration behaviour of the chondrocytes could also be caused by the surface structure of the scaffolds.

The conclusion is that the new geometry of the reactor vessel leads to better results concerning cell migration into the scaffold matrix in all the scaffolds regardless of their position in the vessel. This might result from the nearly homogeneous medium flow characteristics and the consequential similar stresses like pressure and wall shear stress on the scaffolds.

These first results will be evaluated in more detail by additional cultivations to obtain more detailed information on cell behaviour under the above mentioned cultivation conditions.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Katja Urlbauer and Monika Jerg, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Ulm University Medical Center for their technical assistance and Prof. Dr. Christian Dettmann, Ulm University of Applied Sciences for his support concerning the CFD modelling.

Author’s Statement

Research funding: This work is part of the project “BioopTiss” supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Förderkennzeichen 03FH00813). Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest. Material and methods: Informed consent: Informed consent has been obtained from all individuals included in this study. All patient enrolled in this research have responded to an Informed Consent. Ethical approval: The research related to human use complies with all the relevant national regulations, institutional policies and was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration, and has been approved by the authors’ institutional review board or equivalent committee. Cartilage harvesting was approved by the University of Ulm Ethics Committee (No. 152/08).

References

[1] Bos EJ, Scholten T, Song Y, Verlinden JC, Wolff J, Forouzanfar T, et al. Developing a parametric ear model for auricular reconstruction: a new step towards patient-specific implants. J Cranio-Maxillo-Fac Surg. 2015;43:390–5.10.1016/j.jcms.2014.12.016Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Cao Y, Vacanti JP, Paige KT, Upton J, Vacanti CA. Transplantation of chondrocytes utilizing a polymer-cell construct to produce tissue-engineered cartilage in the shape of a human ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:297–302.10.1097/00006534-199708000-00001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Constantine KK, Gilmore J, Lee K, Leach J Jr. Comparison of microtia reconstruction outcomes using rib cartilage vs porous polyethylene implant. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2014;16:240–4.10.1001/jamafacial.2014.30Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Kim WS, Vacanti JP, Cima L, Mooney D, Upton J, Puelacher WC, et al. Cartilage engineered in predetermined shapes employing cell transplantation on synthetic biodegradable polymers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:233–7.10.1097/00006534-199408000-00001Search in Google Scholar

[5] Chen HC, Hu YC. Bioreactors for tissue engineering. Biotechnol Lett. 2006;28:1415–23.10.1007/s10529-006-9111-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Martin I, Wendt D, Heberer M. The role of bioreactors in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2004;22:80–6.10.1016/j.tibtech.2003.12.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Wendt D, Riboldi SA, Cioffi M, Martin I. Bioreactors in tissue engineering: scientific challenges and clinical perspectives. Adv Biochem Engine/Biotechnol. 2009;112:1–27.10.1007/10_2008_1Search in Google Scholar

[8] Princz S, Wenzel U, Tritschler H, Schwarz S, Dettmann C, Rotter N, et al. Automated bioreactor system for cartilage tissue engineering of human primary nasal septal chondrocytes. Biomedical Engineering/Biomedizinische Technik, (under review, submitted 2015-12-31).10.1515/bmt-2015-0248Search in Google Scholar

[9] Schwarz S, Koerber L, Elsaesser AF, Goldberg-Bockhorn E, Seitz AM, Dürselen L, et al. Decellularized cartilage matrix as a novel biomatrix for cartillage tissue-engineering applications. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:2195–209.10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0705Search in Google Scholar

[10] Schwarz S, Elsaesser AF, Koerber L, Goldberg-Bockhorn E, Seitz AM, Bermueller C, et al. Processed xenogenic cartilage as innovative biomatrix for cartilage tissue engineering: effects on chondrocyte differentiation and function. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2015;9:E239–51. Epub 2012.10.1002/term.1650Search in Google Scholar PubMed

©2016 Sascha Princz et al., licensee De Gruyter.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Synthesis and characterization of PIL/pNIPAAm hybrid hydrogels

- Novel blood protein based scaffolds for cardiovascular tissue engineering

- Cell adhesion and viability of human endothelial cells on electrospun polymer scaffolds

- Effects of heat treatment and welding process on superelastic behaviour and microstructure of micro electron beam welded NiTi

- Long-term stable modifications of silicone elastomer for improved hemocompatibility

- The effect of thermal treatment on the mechanical properties of PLLA tubular specimens

- Biocompatible wear-resistant thick ceramic coating

- Protection of active implant electronics with organosilicon open air plasma coating for plastic overmolding

- Examination of dielectric strength of thin Parylene C films under various conditions

- Open air plasma deposited antimicrobial SiOx/TiOx composite films for biomedical applications

- Systemic analysis about residual chloroform in PLLA films

- A macrophage model of osseointegration

- Towards in silico prognosis using big data

- Technical concept and evaluation of a novel shoulder simulator with adaptive muscle force generation and free motion

- Usability evaluation of a locomotor therapy device considering different strategies

- Hypoxia-on-a-chip

- Integration of a semi-automatic in-vitro RFA procedure into an experimental setup

- Fabrication of MEMS-based 3D-μECoG-MEAs

- High speed digital interfacing for a neural data acquisition system

- Bionic forceps for the handling of sensitive tissue

- Experimental studies on 3D printing of barium titanate ceramics for medical applications

- Patient specific root-analogue dental implants – additive manufacturing and finite element analysis

- 3D printing – a key technology for tailored biomedical cell culture lab ware

- 3D printing of hydrogels in a temperature controlled environment with high spatial resolution

- Biocompatibility of photopolymers for additive manufacturing

- Biochemical piezoresistive sensors based on pH- and glucose-sensitive hydrogels for medical applications

- Novel wireless measurement system of pressure dedicated to in vivo studies

- Portable auricular device for real-time swallow and chew detection

- Detection of miRNA using a surface plasmon resonance biosensor and antibody amplification

- Simulation and evaluation of stimulation scenarios for targeted vestibular nerve excitation

- Deep brain stimulation: increasing efficiency by alternative waveforms

- Prediction of immediately occurring microsleep events from brain electric signals

- Determining cardiac vagal threshold from short term heart rate complexity

- Classification of cardiac excitation patterns during atrial fibrillation

- An algorithm to automatically determine the cycle length coverage to identify rotational activity during atrial fibrillation – a simulation study

- Deriving respiration from high resolution 12-channel-ECG during cycling exercise

- Reducing of gradient induced artifacts on the ECG signal during MRI examinations using Wilcoxon filter

- Automatic detection and mapping of double potentials in intracardiac electrograms

- Modeling the pelvic region for non-invasive pelvic intraoperative neuromonitoring

- Postprocessing algorithm for automated analysis of pelvic intraoperative neuromonitoring signals

- Best practice: surgeon driven application in pelvic operations

- Vasomotor assessment by camera-based photoplethysmography

- Classification of morphologic changes in photoplethysmographic waveforms

- Novel computation of pulse transit time from multi-channel PPG signals by wavelet transform

- Efficient design of FIR filter based low-pass differentiators for biomedical signal processing

- Nonlinear causal influences assessed by mutual compression entropy

- Comparative study of methods for solving the correspondence problem in EMD applications

- fNIRS for future use in auditory diagnostics

- Semi-automated detection of fractional shortening in zebrafish embryo heart videos

- Blood pressure measurement on the cheek

- Derivation of the respiratory rate from directly and indirectly measured respiratory signals using autocorrelation

- Left cardiac atrioventricular delay and inter-ventricular delay in cardiac resynchronization therapy responder and non-responder

- An automatic systolic peak detector of blood pressure waveforms using 4th order cumulants

- Real-time QRS detection using integrated variance for ECG gated cardiac MRI

- Preprocessing of unipolar signals acquired by a novel intracardiac mapping system

- In-vitro experiments to characterize ventricular electromechanics

- Continuous non-invasive monitoring of blood pressure in the operating room: a cuffless optical technology at the fingertip

- Application of microwave sensor technology in cardiovascular disease for plaque detection

- Artificial blood circulatory and special Ultrasound Doppler probes for detecting and sizing gaseous embolism

- Detection of microsleep events in a car driving simulation study using electrocardiographic features

- A method to determine the kink resistance of stents and stent delivery systems according to international standards

- Comparison of stented bifurcation and straight vessel 3D-simulation with a prior simulated velocity profile inlet

- Transient Euler-Lagrange/DEM simulation of stent thrombosis

- Automated control of the laser welding process of heart valve scaffolds

- Automation of a test bench for accessing the bendability of electrospun vascular grafts

- Influence of storage conditions on the release of growth factors in platelet-rich blood derivatives

- Cryopreservation of cells using defined serum-free cryoprotective agents

- New bioreactor vessel for tissue engineering of human nasal septal chondrocytes

- Determination of the membrane hydraulic permeability of MSCs

- Climate retainment in carbon dioxide incubators

- Multiple factors influencing OR ventilation system effectiveness

- Evaluation of an app-based stress protocol

- Medication process in Styrian hospitals

- Control tower to surgical theater

- Development of a skull phantom for the assessment of implant X-ray visibility

- Surgical navigation with QR codes

- Investigation of the pressure gradient of embolic protection devices

- Computer assistance in femoral derotation osteotomy: a bottom-up approach

- Automatic depth scanning system for 3D infrared thermography

- A service for monitoring the quality of intraoperative cone beam CT images

- Resectoscope with an easy to use twist mechanism for improved handling

- In vitro simulation of distribution processes following intramuscular injection

- Adjusting inkjet printhead parameters to deposit drugs into micro-sized reservoirs

- A flexible standalone system with integrated sensor feedback for multi-pad electrode FES of the hand

- Smart control for functional electrical stimulation with optimal pulse intensity

- Tactile display on the remaining hand for unilateral hand amputees

- Effects of sustained electrical stimulation on spasticity assessed by the pendulum test

- An improved tracking framework for ultrasound probe localization in image-guided radiosurgery

- Improvement of a subviral particle tracker by the use of a LAP-Kalman-algorithm

- Learning discriminative classification models for grading anal intraepithelial neoplasia

- Regularization of EIT reconstruction based on multi-scales wavelet transforms

- Assessing MRI susceptibility artefact through an indicator of image distortion

- EyeGuidance – a computer controlled system to guide eye movements

- A framework for feedback-based segmentation of 3D image stacks

- Doppler optical coherence tomography as a promising tool for detecting fluid in the human middle ear

- 3D Local in vivo Environment (LivE) imaging for single cell protein analysis of bone tissue

- Inside-Out access strategy using new trans-vascular catheter approach

- US/MRI fusion with new optical tracking and marker approach for interventional procedures inside the MRI suite

- Impact of different registration methods in MEG source analysis

- 3D segmentation of thyroid ultrasound images using active contours

- Designing a compact MRI motion phantom

- Cerebral cortex classification by conditional random fields applied to intraoperative thermal imaging

- Classification of indirect immunofluorescence images using thresholded local binary count features

- Analysis of muscle fatigue conditions using time-frequency images and GLCM features

- Numerical evaluation of image parameters of ETR-1

- Fabrication of a compliant phantom of the human aortic arch for use in Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) experimentation

- Effect of the number of electrodes on the reconstructed lung shape in electrical impedance tomography

- Hardware dependencies of GPU-accelerated beamformer performances for microwave breast cancer detection

- Computer assisted assessment of progressing osteoradionecrosis of the jaw for clinical diagnosis and treatment

- Evaluation of reconstruction parameters of electrical impedance tomography on aorta detection during saline bolus injection

- Evaluation of open-source software for the lung segmentation

- Automatic determination of lung features of CF patients in CT scans

- Image analysis of self-organized multicellular patterns

- Effect of key parameters on synthesis of superparamagnetic nanoparticles (SPIONs)

- Radiopacity assessment of neurovascular implants

- Development of a desiccant based dielectric for monitoring humidity conditions in miniaturized hermetic implantable packages

- Development of an artifact-free aneurysm clip

- Enhancing the regeneration of bone defects by alkalizing the peri-implant zone – an in vitro approach

- Rapid prototyping of replica knee implants for in vitro testing

- Protecting ultra- and hyperhydrophilic implant surfaces in dry state from loss of wettability

- Advanced wettability analysis of implant surfaces

- Patient-specific hip prostheses designed by surgeons

- Plasma treatment on novel carbon fiber reinforced PEEK cages to enhance bioactivity

- Wear of a total intervertebral disc prosthesis

- Digital health and digital biomarkers – enabling value chains on health data

- Usability in the lifecycle of medical software development

- Influence of different test gases in a non-destructive 100% quality control system for medical devices

- Device development guided by user satisfaction survey on auricular vagus nerve stimulation

- Empirical assessment of the time course of innovation in biomedical engineering: first results of a comparative approach

- Effect of left atrial hypertrophy on P-wave morphology in a computational model

- Simulation of intracardiac electrograms around acute ablation lesions

- Parametrization of activation based cardiac electrophysiology models using bidomain model simulations

- Assessment of nasal resistance using computational fluid dynamics

- Resistance in a non-linear autoregressive model of pulmonary mechanics

- Inspiratory and expiratory elastance in a non-linear autoregressive model of pulmonary mechanics

- Determination of regional lung function in cystic fibrosis using electrical impedance tomography

- Development of parietal bone surrogates for parietal graft lift training

- Numerical simulation of mechanically stimulated bone remodelling

- Conversion of engineering stresses to Cauchy stresses in tensile and compression tests of thermoplastic polymers

- Numerical examinations of simplified spondylodesis models concerning energy absorption in magnetic resonance imaging

- Principle study on the signal connection at transabdominal fetal pulse oximetry

- Influence of Siluron® insertion on model drug distribution in the simulated vitreous body

- Evaluating different approaches to identify a three parameter gas exchange model

- Effects of fibrosis on the extracellular potential based on 3D reconstructions from histological sections of heart tissue

- From imaging to hemodynamics – how reconstruction kernels influence the blood flow predictions in intracranial aneurysms

- Flow optimised design of a novel point-of-care diagnostic device for the detection of disease specific biomarkers

- Improved FPGA controlled artificial vascular system for plethysmographic measurements

- Minimally spaced electrode positions for multi-functional chest sensors: ECG and respiratory signal estimation

- Automated detection of alveolar arches for nasoalveolar molding in cleft lip and palate treatment

- Control scheme selection in human-machine- interfaces by analysis of activity signals

- Event-based sampling for reducing communication load in realtime human motion analysis by wireless inertial sensor networks

- Automatic pairing of inertial sensors to lower limb segments – a plug-and-play approach

- Contactless respiratory monitoring system for magnetic resonance imaging applications using a laser range sensor

- Interactive monitoring system for visual respiratory biofeedback

- Development of a low-cost senor based aid for visually impaired people

- Patient assistive system for the shoulder joint

- A passive beating heart setup for interventional cardiology training

Articles in the same Issue

- Synthesis and characterization of PIL/pNIPAAm hybrid hydrogels

- Novel blood protein based scaffolds for cardiovascular tissue engineering

- Cell adhesion and viability of human endothelial cells on electrospun polymer scaffolds

- Effects of heat treatment and welding process on superelastic behaviour and microstructure of micro electron beam welded NiTi

- Long-term stable modifications of silicone elastomer for improved hemocompatibility

- The effect of thermal treatment on the mechanical properties of PLLA tubular specimens

- Biocompatible wear-resistant thick ceramic coating

- Protection of active implant electronics with organosilicon open air plasma coating for plastic overmolding

- Examination of dielectric strength of thin Parylene C films under various conditions

- Open air plasma deposited antimicrobial SiOx/TiOx composite films for biomedical applications

- Systemic analysis about residual chloroform in PLLA films

- A macrophage model of osseointegration

- Towards in silico prognosis using big data

- Technical concept and evaluation of a novel shoulder simulator with adaptive muscle force generation and free motion

- Usability evaluation of a locomotor therapy device considering different strategies

- Hypoxia-on-a-chip

- Integration of a semi-automatic in-vitro RFA procedure into an experimental setup

- Fabrication of MEMS-based 3D-μECoG-MEAs

- High speed digital interfacing for a neural data acquisition system

- Bionic forceps for the handling of sensitive tissue

- Experimental studies on 3D printing of barium titanate ceramics for medical applications

- Patient specific root-analogue dental implants – additive manufacturing and finite element analysis

- 3D printing – a key technology for tailored biomedical cell culture lab ware

- 3D printing of hydrogels in a temperature controlled environment with high spatial resolution

- Biocompatibility of photopolymers for additive manufacturing

- Biochemical piezoresistive sensors based on pH- and glucose-sensitive hydrogels for medical applications

- Novel wireless measurement system of pressure dedicated to in vivo studies

- Portable auricular device for real-time swallow and chew detection

- Detection of miRNA using a surface plasmon resonance biosensor and antibody amplification

- Simulation and evaluation of stimulation scenarios for targeted vestibular nerve excitation

- Deep brain stimulation: increasing efficiency by alternative waveforms

- Prediction of immediately occurring microsleep events from brain electric signals

- Determining cardiac vagal threshold from short term heart rate complexity

- Classification of cardiac excitation patterns during atrial fibrillation

- An algorithm to automatically determine the cycle length coverage to identify rotational activity during atrial fibrillation – a simulation study

- Deriving respiration from high resolution 12-channel-ECG during cycling exercise

- Reducing of gradient induced artifacts on the ECG signal during MRI examinations using Wilcoxon filter

- Automatic detection and mapping of double potentials in intracardiac electrograms

- Modeling the pelvic region for non-invasive pelvic intraoperative neuromonitoring

- Postprocessing algorithm for automated analysis of pelvic intraoperative neuromonitoring signals

- Best practice: surgeon driven application in pelvic operations

- Vasomotor assessment by camera-based photoplethysmography

- Classification of morphologic changes in photoplethysmographic waveforms

- Novel computation of pulse transit time from multi-channel PPG signals by wavelet transform

- Efficient design of FIR filter based low-pass differentiators for biomedical signal processing

- Nonlinear causal influences assessed by mutual compression entropy

- Comparative study of methods for solving the correspondence problem in EMD applications

- fNIRS for future use in auditory diagnostics

- Semi-automated detection of fractional shortening in zebrafish embryo heart videos

- Blood pressure measurement on the cheek

- Derivation of the respiratory rate from directly and indirectly measured respiratory signals using autocorrelation

- Left cardiac atrioventricular delay and inter-ventricular delay in cardiac resynchronization therapy responder and non-responder

- An automatic systolic peak detector of blood pressure waveforms using 4th order cumulants

- Real-time QRS detection using integrated variance for ECG gated cardiac MRI

- Preprocessing of unipolar signals acquired by a novel intracardiac mapping system

- In-vitro experiments to characterize ventricular electromechanics

- Continuous non-invasive monitoring of blood pressure in the operating room: a cuffless optical technology at the fingertip

- Application of microwave sensor technology in cardiovascular disease for plaque detection

- Artificial blood circulatory and special Ultrasound Doppler probes for detecting and sizing gaseous embolism

- Detection of microsleep events in a car driving simulation study using electrocardiographic features

- A method to determine the kink resistance of stents and stent delivery systems according to international standards

- Comparison of stented bifurcation and straight vessel 3D-simulation with a prior simulated velocity profile inlet

- Transient Euler-Lagrange/DEM simulation of stent thrombosis

- Automated control of the laser welding process of heart valve scaffolds

- Automation of a test bench for accessing the bendability of electrospun vascular grafts

- Influence of storage conditions on the release of growth factors in platelet-rich blood derivatives

- Cryopreservation of cells using defined serum-free cryoprotective agents

- New bioreactor vessel for tissue engineering of human nasal septal chondrocytes

- Determination of the membrane hydraulic permeability of MSCs

- Climate retainment in carbon dioxide incubators

- Multiple factors influencing OR ventilation system effectiveness

- Evaluation of an app-based stress protocol

- Medication process in Styrian hospitals

- Control tower to surgical theater

- Development of a skull phantom for the assessment of implant X-ray visibility

- Surgical navigation with QR codes

- Investigation of the pressure gradient of embolic protection devices

- Computer assistance in femoral derotation osteotomy: a bottom-up approach

- Automatic depth scanning system for 3D infrared thermography

- A service for monitoring the quality of intraoperative cone beam CT images

- Resectoscope with an easy to use twist mechanism for improved handling

- In vitro simulation of distribution processes following intramuscular injection

- Adjusting inkjet printhead parameters to deposit drugs into micro-sized reservoirs

- A flexible standalone system with integrated sensor feedback for multi-pad electrode FES of the hand

- Smart control for functional electrical stimulation with optimal pulse intensity

- Tactile display on the remaining hand for unilateral hand amputees

- Effects of sustained electrical stimulation on spasticity assessed by the pendulum test

- An improved tracking framework for ultrasound probe localization in image-guided radiosurgery

- Improvement of a subviral particle tracker by the use of a LAP-Kalman-algorithm

- Learning discriminative classification models for grading anal intraepithelial neoplasia

- Regularization of EIT reconstruction based on multi-scales wavelet transforms

- Assessing MRI susceptibility artefact through an indicator of image distortion

- EyeGuidance – a computer controlled system to guide eye movements

- A framework for feedback-based segmentation of 3D image stacks

- Doppler optical coherence tomography as a promising tool for detecting fluid in the human middle ear

- 3D Local in vivo Environment (LivE) imaging for single cell protein analysis of bone tissue

- Inside-Out access strategy using new trans-vascular catheter approach

- US/MRI fusion with new optical tracking and marker approach for interventional procedures inside the MRI suite

- Impact of different registration methods in MEG source analysis

- 3D segmentation of thyroid ultrasound images using active contours

- Designing a compact MRI motion phantom

- Cerebral cortex classification by conditional random fields applied to intraoperative thermal imaging

- Classification of indirect immunofluorescence images using thresholded local binary count features

- Analysis of muscle fatigue conditions using time-frequency images and GLCM features

- Numerical evaluation of image parameters of ETR-1

- Fabrication of a compliant phantom of the human aortic arch for use in Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) experimentation

- Effect of the number of electrodes on the reconstructed lung shape in electrical impedance tomography

- Hardware dependencies of GPU-accelerated beamformer performances for microwave breast cancer detection

- Computer assisted assessment of progressing osteoradionecrosis of the jaw for clinical diagnosis and treatment

- Evaluation of reconstruction parameters of electrical impedance tomography on aorta detection during saline bolus injection

- Evaluation of open-source software for the lung segmentation

- Automatic determination of lung features of CF patients in CT scans

- Image analysis of self-organized multicellular patterns

- Effect of key parameters on synthesis of superparamagnetic nanoparticles (SPIONs)

- Radiopacity assessment of neurovascular implants

- Development of a desiccant based dielectric for monitoring humidity conditions in miniaturized hermetic implantable packages

- Development of an artifact-free aneurysm clip

- Enhancing the regeneration of bone defects by alkalizing the peri-implant zone – an in vitro approach

- Rapid prototyping of replica knee implants for in vitro testing

- Protecting ultra- and hyperhydrophilic implant surfaces in dry state from loss of wettability

- Advanced wettability analysis of implant surfaces

- Patient-specific hip prostheses designed by surgeons

- Plasma treatment on novel carbon fiber reinforced PEEK cages to enhance bioactivity

- Wear of a total intervertebral disc prosthesis

- Digital health and digital biomarkers – enabling value chains on health data

- Usability in the lifecycle of medical software development

- Influence of different test gases in a non-destructive 100% quality control system for medical devices

- Device development guided by user satisfaction survey on auricular vagus nerve stimulation

- Empirical assessment of the time course of innovation in biomedical engineering: first results of a comparative approach

- Effect of left atrial hypertrophy on P-wave morphology in a computational model

- Simulation of intracardiac electrograms around acute ablation lesions

- Parametrization of activation based cardiac electrophysiology models using bidomain model simulations

- Assessment of nasal resistance using computational fluid dynamics

- Resistance in a non-linear autoregressive model of pulmonary mechanics

- Inspiratory and expiratory elastance in a non-linear autoregressive model of pulmonary mechanics

- Determination of regional lung function in cystic fibrosis using electrical impedance tomography

- Development of parietal bone surrogates for parietal graft lift training

- Numerical simulation of mechanically stimulated bone remodelling

- Conversion of engineering stresses to Cauchy stresses in tensile and compression tests of thermoplastic polymers

- Numerical examinations of simplified spondylodesis models concerning energy absorption in magnetic resonance imaging

- Principle study on the signal connection at transabdominal fetal pulse oximetry

- Influence of Siluron® insertion on model drug distribution in the simulated vitreous body

- Evaluating different approaches to identify a three parameter gas exchange model

- Effects of fibrosis on the extracellular potential based on 3D reconstructions from histological sections of heart tissue

- From imaging to hemodynamics – how reconstruction kernels influence the blood flow predictions in intracranial aneurysms

- Flow optimised design of a novel point-of-care diagnostic device for the detection of disease specific biomarkers

- Improved FPGA controlled artificial vascular system for plethysmographic measurements

- Minimally spaced electrode positions for multi-functional chest sensors: ECG and respiratory signal estimation

- Automated detection of alveolar arches for nasoalveolar molding in cleft lip and palate treatment

- Control scheme selection in human-machine- interfaces by analysis of activity signals

- Event-based sampling for reducing communication load in realtime human motion analysis by wireless inertial sensor networks

- Automatic pairing of inertial sensors to lower limb segments – a plug-and-play approach

- Contactless respiratory monitoring system for magnetic resonance imaging applications using a laser range sensor

- Interactive monitoring system for visual respiratory biofeedback

- Development of a low-cost senor based aid for visually impaired people

- Patient assistive system for the shoulder joint

- A passive beating heart setup for interventional cardiology training