Abstract

The study aims to substitute river sand used in ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) with pond ash (PA), a waste by-product from the Sikka thermal power station in Gujarat, India, at replacement levels ranging from 0 to 20%. Also, 20% of the cement was replaced with ground granulated blast-furnace slag, which is a sustainable, eco-friendly material. As a result, this concrete is both environmentally and economically feasible. Experimental analysis evaluated the workability, compressive strength, split tensile strength, flexural strength, and microstructure of the UHPC mixtures. Incorporating 10% PA as a sand replacement enhanced the compressive strength, reaching 117 MPa at 90 days, as well as the flexural strength of 23 MPa and the split tensile strength of 14 MPa. The strength is positively impacted when 10% of the river sand is replaced with PA, while the strength of UHPC appears to be diminished if PA content is increased beyond 10% replacement of sand. Petrographic microscopy and X-ray diffraction were used to study the microstructure of UHPC made with PA. When PA was used instead of sand, the mortar mass solidified and became denser, resulting in an improved microstructure of the UHPC with fewer surface cracks. With the inclusion of PA, the calcium silica hydrate gel content of the concrete increases, and enhanced performance of UHPC up to a certain amount of replacement has been observed.

1 Introduction

Ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) is recognized for its exceptional durability and high performance. It has emerged as a promising material for enhancing the sustainability of various structural and infrastructural elements. Over the past two decades, there has been significant global interest in UHPC, with applications spanning bridges, building components, architectural features, precast concrete piles, repair and rehabilitation work, offshore and hydraulic structures, and thin-bonded overlays on deteriorated bridge decks [1,2]. Among these, bridge and road construction are the most prevalent uses of UHPC [3,4].

A typical UHPC mixture includes binding materials, fine aggregates, superplasticizers (SPs), fibers, and controlled amounts of water. In both UHPC and conventional concrete, a dense particle skeleton is formed where the fine aggregate plays a critical role [5,6]. The fine aggregate significantly influences the mechanical properties and durability of concrete. Historically, natural river sand (NRS) has been the primary fine aggregate used in UHPC [7]. However, the unsustainable extraction of river sand poses serious environmental risks, including ecosystem disruption, riverbank erosion, and infrastructure instability [8].

With rapidly growing construction demands, India requires approximately 900 million tonnes of sand annually to sustain its development. This high demand for sand highlights the scarcity issue, as excessive sand mining can alter river channels, cause bank erosion, and disrupt aquatic habitats [9]. The utilization of resources such as water, energy, and land plays a crucial role in climate change dynamics. Recognizing these challenges, the United Nations General Assembly established the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015 to promote global sustainability. The construction industry, being a significant consumer of non-renewable resources, must adopt more sustainable practices to mitigate environmental impacts.

Researchers are exploring the use of residual materials from thermal power plants, such as bottom ash, fly ash, and pond ash (PA), in cement, mortar, and concrete production to address waste disposal challenges [10,11]. While substantial research exists on bottom ash and fly ash, there is limited information on PA utilization [12,13,14]. Incorporating PA as a replacement material can help manage waste, reduce environmental impact, and address the scarcity of natural sand resources. Vast reserves of PA occupy significant land areas in India, and its use in construction could alleviate sand shortages [15,16]. However, the presence of toxic components in ash ponds requires careful handling to prevent soil and water contamination as shown in Figure 1.

PA sample collected from thermal power plant.

Extensive research has investigated the use of PA as a substitute for fine aggregate in conventional concrete, but its application in UHPC remains largely unexplored. This study aims to fill this gap by evaluating the potential of PA as a fine aggregate replacement in UHPC, presenting a novel avenue for research in sustainable construction materials.

2 Materials

Ordinary Portland cement (OPC), fly ash, silica fume, NRS, ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS), polycarboxylate ether-based SP, steel fibers, and water are the materials used to produce UHPC [17,18,19], which are depicted in Figure 2.

Materials used for producing UHPC.

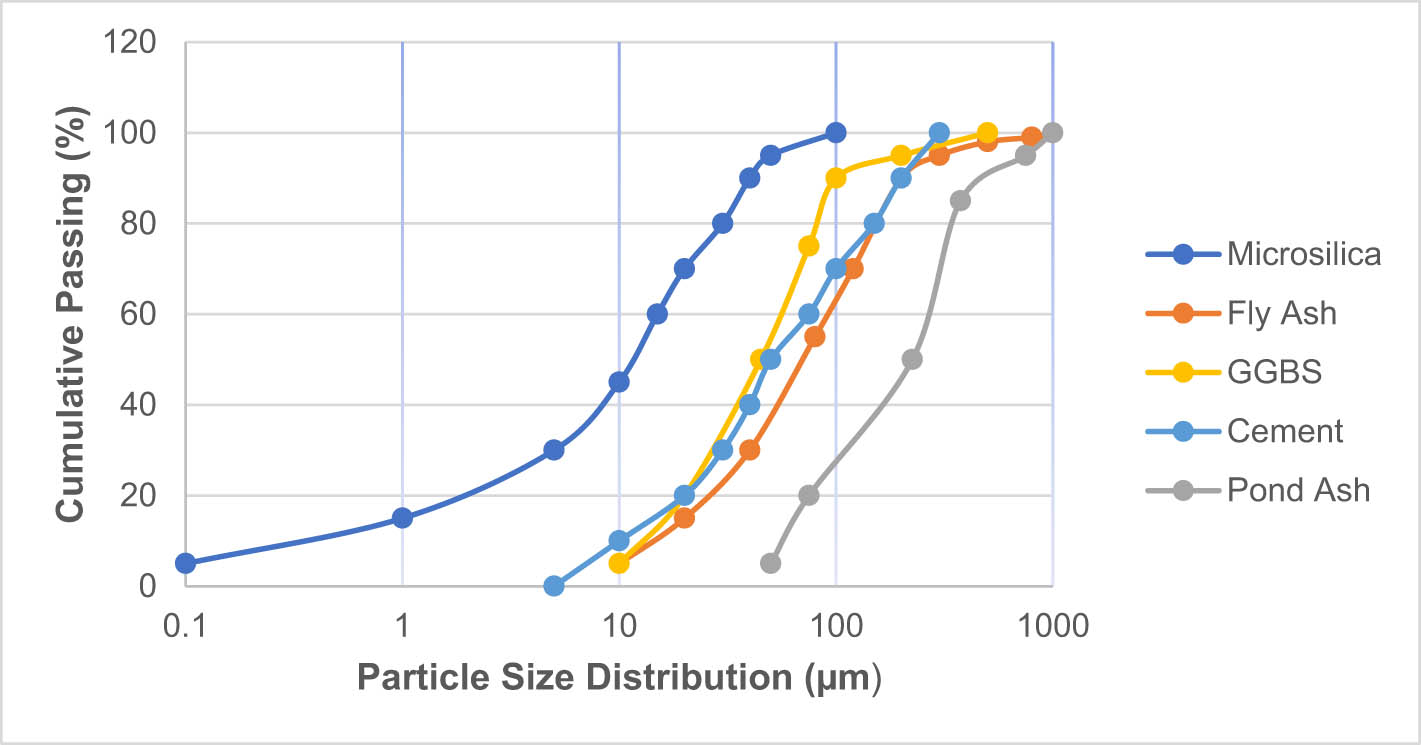

River sand with a size range of 600–150 µ, OPC of 53 grade as per requirements specified by IS: 12269 [20] and microsilica with an extreme fineness and high amorphous silica concentration are all necessary ingredients in UHPC due to their filler and pozzolanic properties. The tensile strength of the brass-coated steel microfibers, which were 13 mm in long and 0.2 mm in diameter, was 2,500 MPa. Table 1 lists the chemical characteristics of the raw material used in UHPC, and Figure 3 shows the particle size distribution curve of different raw materials needed to produce UHPC.

Chemical properties of raw materials used in UHPC at room temperature (25°C)

| Oxide | Cement | NRS | Fly ash | GGBS | Microsilica | Pond ash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | 64.1 | 3.54 | 7.89 | 45.86 | 0.36 | 0.86 |

| SiO₂ | 21.76 | 76.43 | 47.36 | 30.12 | 96.65 | 63.66 |

| Al₂O₃ | 5.8 | 15.71 | 39.01 | 13.35 | 0.25 | 24.53 |

| Fe₂O₃ | 3.3 | 4.23 | 3.52 | 0.45 | 0.15 | 7.24 |

| MgO | 1.75 | — | 0.23 | 4.98 | 0.47 | 0.55 |

| TiO₂ | — | — | 0.06 | — | 0.13 | 1.48 |

| MnO | — | — | 0.03 | — | 0.04 | 0.085 |

| L.O.I. | — | — | 2.79 | — | 2.29 | 2.93 |

| K₂O | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.88 | 0.37 | 0.84 | 1.35 |

| SO₃ | 1.8 | — | 0.69 | 3.51 | 0.69 | 0.13 |

| Na₂O | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.115 |

| Cl− | 0.03 | — | — | — | — |

Natural river sand (NRS); ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS).

Particle size distribution curve of different raw materials.

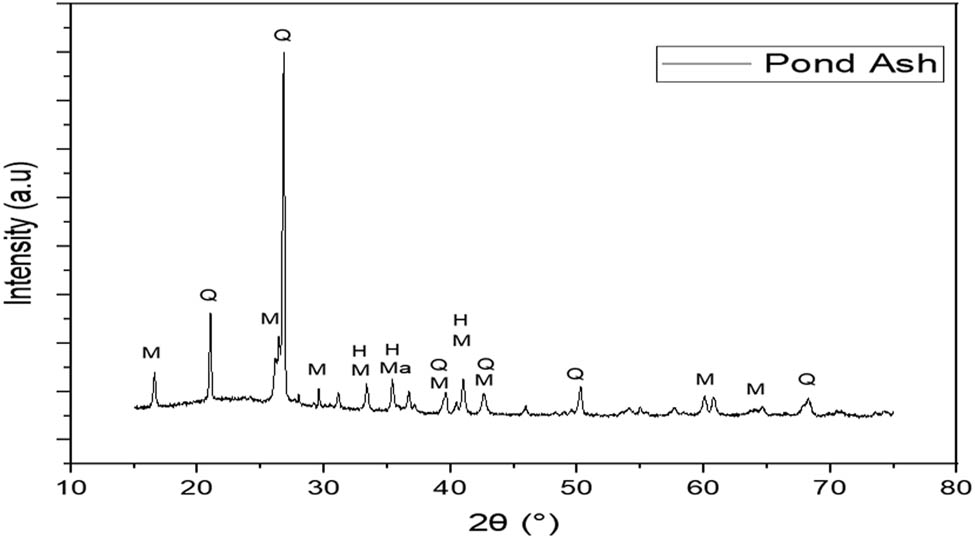

The PA collected from the Sikka Thermal Power Plant was oven-dried before being used as a raw material. Figure 4 shows the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of PA, which shows the peaks characteristic of quartz (SiO2)-Q, mullite (Al6Si2O13)-M, and iron oxides such as magnetite (Fe3O4)-Ma and hematite (Fe2O3)-H, both of which exist in crystalline form. Quartz and mullite are the most common phases and minerals found in ashes. The major peak is recognized as the most intense peak at 2θ = 27.78° due to quartz, the predominant mineral found in PA. Peaks near 2θ = 26.21° have been identified as mullite or aluminosilicate minerals, while those near 2θ = 17.2° have been identified as refractory mullite. The presence of heavy minerals such as magnetite and hematite is indicated by peaks near 2θ of 36.1° and 34.3° (Table 3).

XRD pattern of PA at room temperature (25°C). Mullite (M), quartz (Q), hematite (H), and magnetite (Ma).

2.1 Production of UHPC

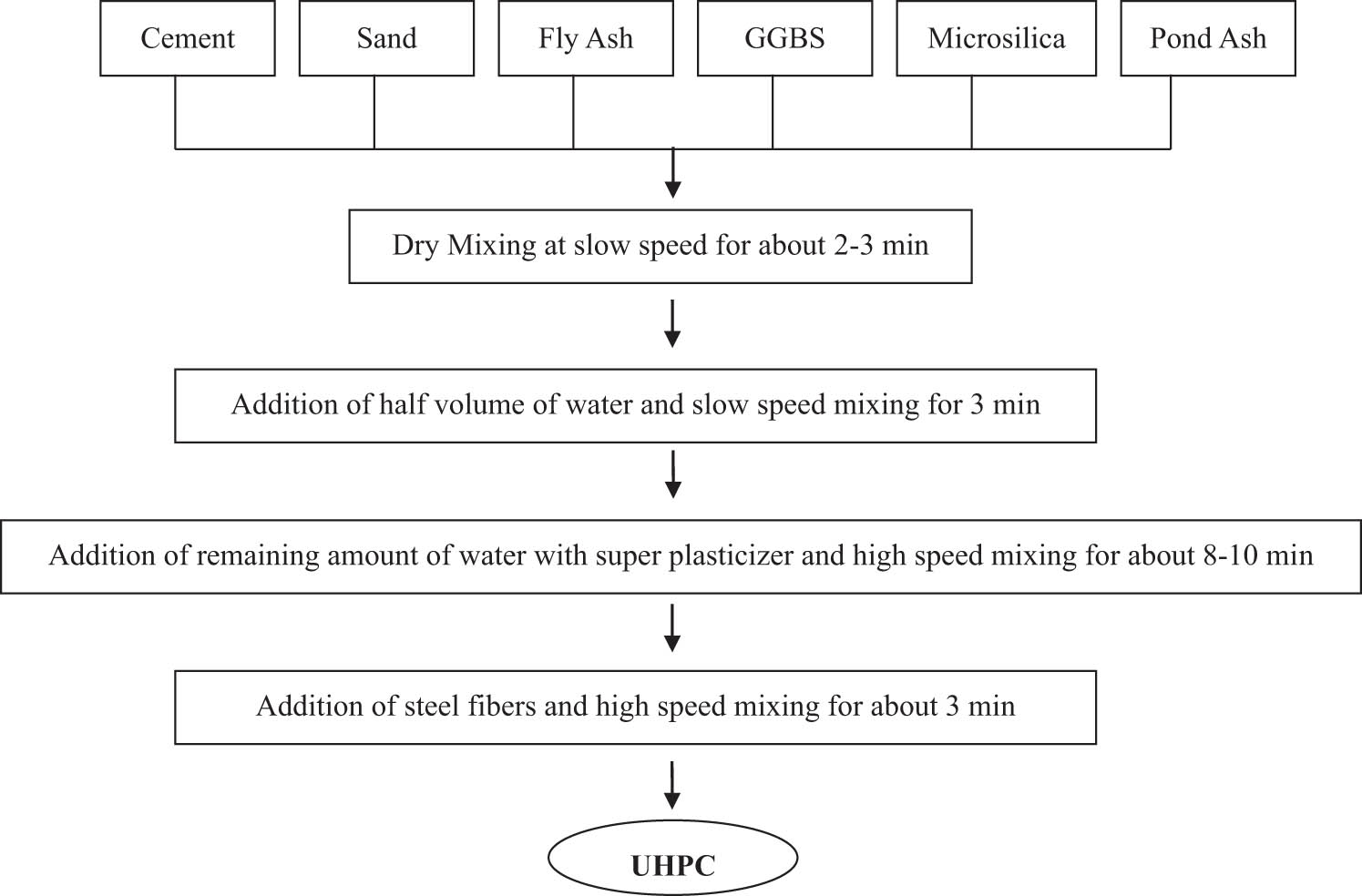

The mixed proportion of UHPC generated in this investigation is summarized in Table 2. The combinations are identified using abbreviations based on the amount of PA in UHPC, as shown in Table 2. The conventional concrete, which was called UHPC0, containing cement, FA, and microsilica as binders, without any GGBS or PA. In contrast, UHPC5, UHPC10, UHPC15, and UHPC20 indicate that 5, 10, 15, and 20% of PA by weight were used to replace NRS, respectively, with 20% of the cement replaced by GGBS. When it came time to prepare the necessary number of specimens in accordance with the mix proportion, the various ingredients needed for the creation of UHPC were weighed and held separately [21,22]. The components of UHPC were mixed using a planetary mixer. Figure 5 depicts the mixing order used for each mixed proportion of UHPC. The order is as follows: first, dry mixing was done for around 2 min with the following materials: cement, microsilica, fly ash, PA, GGBS, and NRS. After adding 50% of the water, the dry ingredients were slowly mixed for 3 min. The SP was then added and properly blended with the remaining 50% water before being added to the mixture for the next 8 min [23]. Steel fibers were added to the mixture once a thick cement matrix paste had formed, and mixing was continued for an additional three minutes to guarantee that the fibers got distributed uniformly throughout the concrete’s mass [12].

Mixture composition of UHPC (kg/m³)

| Mix | Cement | NRS | Pond ash | GGBS | Fly ash | Microsilica | SF | SP | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UHPC0 | 750 | 900 | 0 | 0 | 200 | 144 | 156 | 23 | 211 |

| UHPC5 | 600 | 855 | 45 | 150 | 200 | 144 | 156 | 23 | 211 |

| UHPC10 | 600 | 810 | 90 | 150 | 200 | 144 | 156 | 23 | 211 |

| UHPC15 | 600 | 765 | 135 | 150 | 200 | 144 | 156 | 23 | 211 |

| UHPC20 | 600 | 720 | 180 | 150 | 200 | 144 | 156 | 23 | 211 |

Steel fibers (SF); super plasticizer (SP).

Mixing sequence for developing UHPC.

After being prepared, the mixture was transferred into the molds, which included prismatic beams (100 mm × 100 mm × 500 mm), cylinders (100 mm × 200 mm), and cubes (70.7 mm × 70.7 mm × 70.7 mm). After the mixing procedure was completed, the casting process was finished in 10–15 min. The samples were then left in the molds at room temperature for 24 h. The samples were taken out of the molds after 24 h. According to the guidelines in IS-10262:2019 [24], the samples were cured in water for 7, 14, 28, and 90 days at room temperature.

XRD pattern peaks and mineral phases of pond ash at room temperature (25°C)

| Peak position (2θ) | Mineral phase | Chemical formula | Notation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 27.78 | Quartz | SiO₂ | Q |

| 26.21 | Mullite/aluminosilicate | Al₆Si₂O₁₃ | M |

| 17.2 | Refractory mullite | Al₂O₃·2SiO₂ | — |

| 36.1 | Magnetite | Fe₃O₄ | Ma |

| 34.3 | Hematite | Fe₂O₃ | H |

2.2 Experimental methodology

2.2.1 Compressive strength

The most crucial characteristic of concrete elements is their compressive strength, and for this experimental study, three UHPC cubical samples of size 7.07 cm were created for each combination. The concrete sample must be poured into the cube molds in three layers. Each layer must be compacted by hand or by vibration. Each layer of concrete in the mold must be compacted with a tamping bar. The specimens were demolded after 24 h and then exposed to 28 days of curing in accordance with the requirements set forth in IS 516-1959 [25]. The UHPC samples were placed on a compressive testing machine (CTM) with a 200-ton capacity until failure. At 7, 14, 28, and 90 days, each UHPC mix’s three samples underwent testing. The compressive strength was determined using the three samples’ average values [26,27].

2.2.2 Splitting tensile strength

Three samples per UHPC mix were cast as cylindrical specimens with a 100 mm dia. and 200 mm ht. to estimate the strength of concrete in tension. CTM tested the cylinders’ splitting tensile strength at 7, 14, 28, and 90 days. Accomplishments and test results were controlled in accordance with IS 5816-1999 guidelines [28].

2.2.3 Flexural strength

The strength of the UHPC prismatic beam in flexure was tested on a 4-point flexural test apparatus using a 500-mm-long, 100-mm-squared cross-section cast prismatic beam with three samples per composition in accordance with IS 516:1959 [25].

2.2.4 Fresh concrete test (workability test)

The slump cone test was used in this experimental study to highlight the fresh properties of all mixtures. For assessing the flowability of this type of concrete, which has a texture similar to mortar, slump flow is a suitable criterion. The conical cone had a height of 30 cm, a top dia. of 10 cm, and a bottom dia. of 20 cm. Fresh UHPC was first placed into a mold, after which the conical cone was elevated vertically. The average of two parallel diameters across a concrete spread is referred to as a slump flow.

2.2.5 Microstructure analysis

Utilizing petrographic imaging analysis, the UHPC’s microstructure is examined. Small pieces of prismatic specimens are used to make the slender pieces of the hardened UHPC mix samples, which are then examined under an optical microscope. When 5×, 10×, and 20× lenses are put together, it is easier and more accurate to figure out the exact shapes of the final mix [29].

3 Results

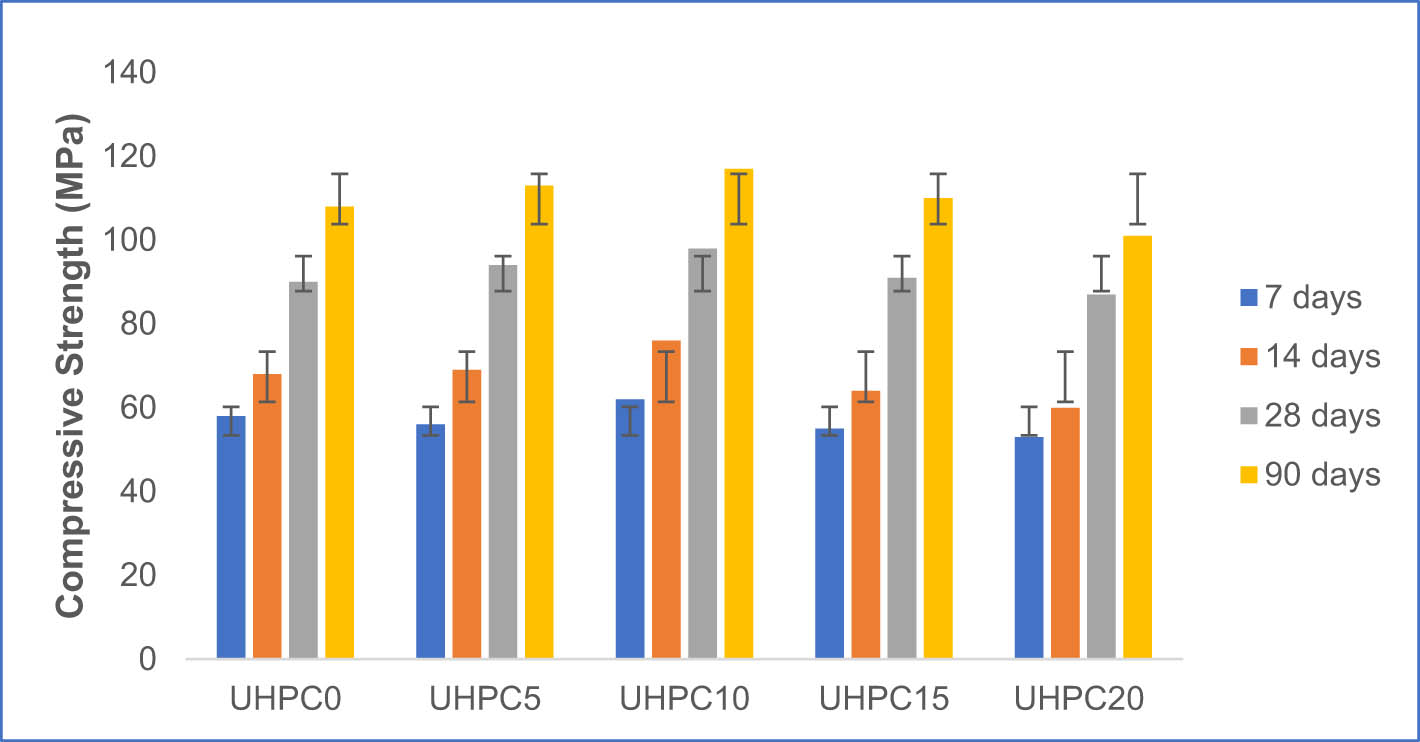

3.1 Compressive strength

The results of determining the compressive strength of UHPC specimens with various replacement percentages of PA by weight of NRS – 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20%, and the variation in compressive strength is shown in Figure 6.

Compressive strength of UHPC cubes with different PA content.

PA affects the strength of UHPC when sand is replaced with it. The 10% replacement of PA in UHPC after 28 days of curing results in the greatest compressive strength improvement. Other curing days’ increases in strength showed a similar pattern. For concrete mixtures up to 10% (UHPC10) cured for 7, 14, 28, and 90 days, an improvement in strength was seen with increasing PA content. The hydration products combine with the integrated supplemental cementitious materials (SCMs), resulting in a newly formed, stronger gel. The whole microstructure, particularly interfacial transition zone (ITZ), had been saturated with this stronger gel, which clearly showed UHPC’s dense and impermeable structure. These SCMs enhance the compressive properties of UHPC due to their pozzolanic reaction with Ca(OH)2 [30].

The strength of the concrete mixtures decreases beyond 10% replacement content. Due to a rise in PA content, more porous particles in the mortar mass did not react with Ca(OH)2 to form C–S–H gel after 10% replacement. As a result, strength drops after UHPC10.

In general, it can be said that PA is marginally good for enhancing UHPC’s compressive strength [15]. PA is therefore an acceptable choice for the aggregate in UHPC from the perspective of its mechanical properties [9,31].

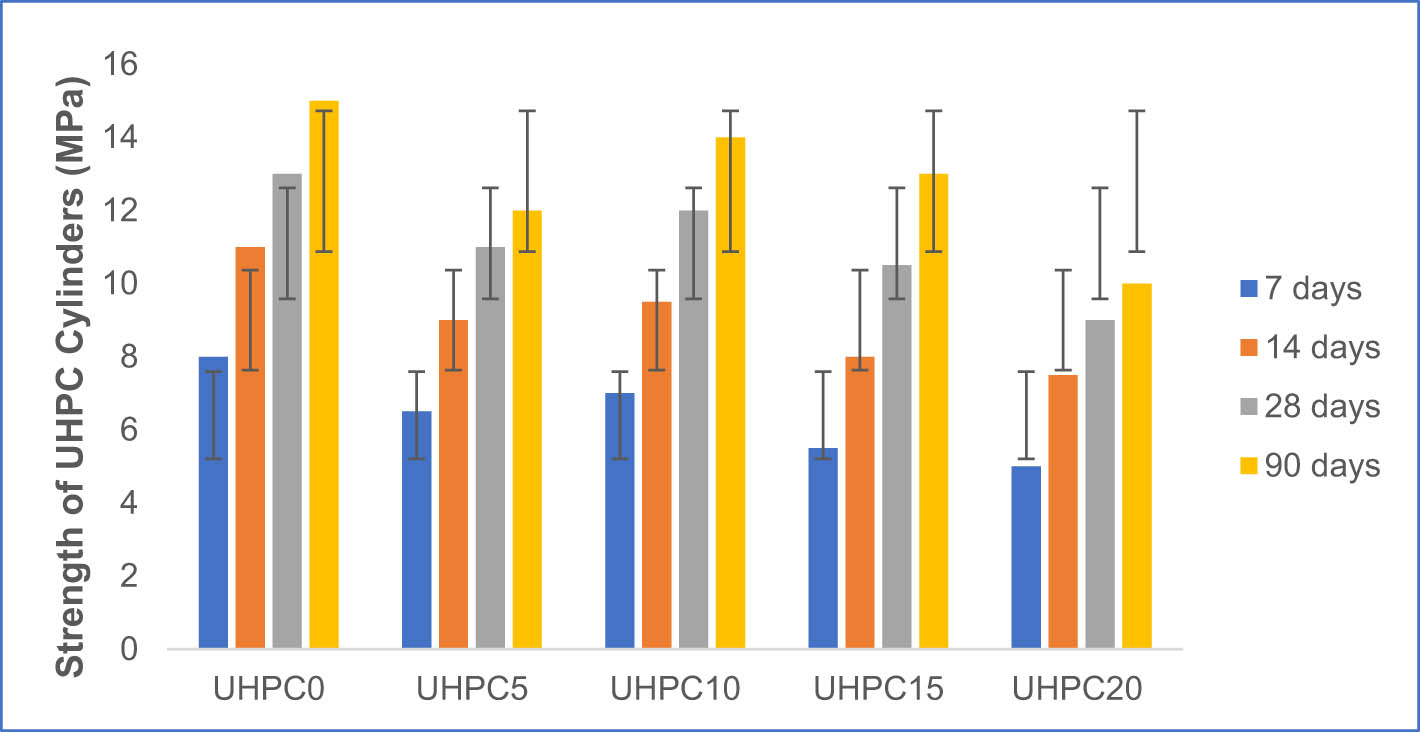

3.2 Split tensile strength

Split tensile strength serves as an indirect indicator of the tensile strength of concrete. The conventional UHPC (UHPC0) cylinder’s average split tensile strengths at 7, 14, 28, and 90 days are 8, 11, 13, and 15 MPa, respectively. When compared to conventional concrete, concrete that contains PA in various percentages has lower split tensile strength values. Figure 7 illustrates the change in tensile strength [32].

Split tensile strength of UHPC cylinders with different PA content.

At all stages of curing, the inclusion of PA decreased the split tensile strength of UHPC. However, the split tensile strength of the UHPC mixture adding 10% PA, or UHPC10, was comparable to that of the controlled UHPC, i.e., UHPC0. At 7, 14, 28, and 90 days, the UHPC10 mixture’s split tensile strength decreased by 12.5, 22.7, 7.69, and 6.66%, respectively. Concrete mixtures UHPC5, UHPC15, and UHPC20 showed lower split tensile strength at 7 days of curing age compared to conventional UHPC, or UHPC0, of 18.75, 31.2, and 37.5%, respectively. Similar to the conventional UHPC, or UHPC0, these UHPC mixtures at 28 days showed lower split tensile strengths of 15.38, 19.23, and 30.76%, respectively. The split tensile strength of these UHPC combinations treated with PA decreased by 20, 13.33, and 33.33%, respectively, after curing for 90 days. PA may have a poorer binding with cement paste than sand, which results in a weaker microstructure of the concrete and a drop in the split tensile strength of UHPC. Cracks appear early in the loading process because of a weak connection between the cement paste and the PA particles. All of these elements together lead to a reduction in split tensile strength. The heterogeneous discontinuity of the cementitious matrix with the weaker transition zone increases as PA concentration rises, and the split tensile strength of concrete further declines [33].

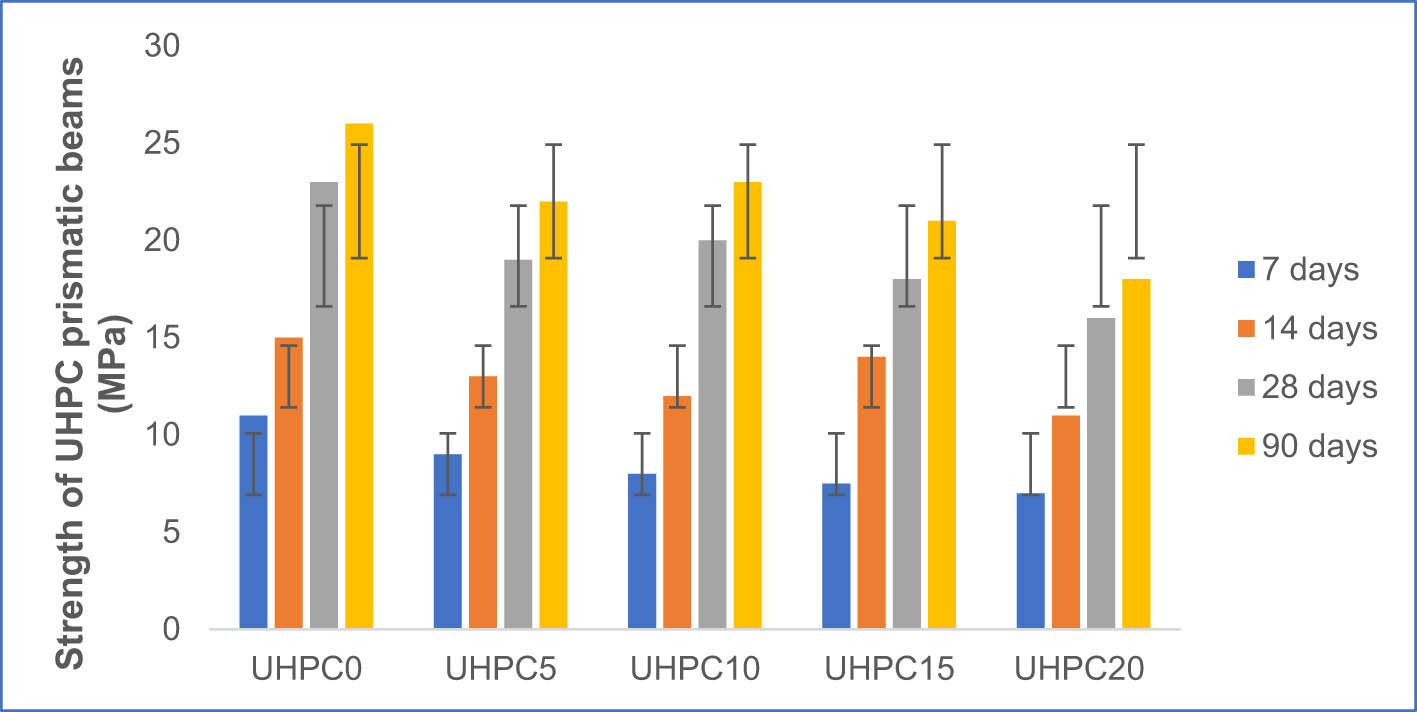

3.3 Flexural strength

Comparing PA in various proportions to conventional UHPC, the flexural strength has decreased at 7, 14, 28, and 90 days. The conventional UHPC (UHPC0) prismatic beam’s average flexural strengths are 11, 15, 23, and 26 MPa, respectively. In comparison to conventional concrete, concrete that contains different percentages of PA has lower values of flexural strength. Figure 8 depicts the variation in flexural strength.

Flexural strength of UHPC beams with different PA content.

At all stages of curing, adding PA decreased the flexural strength of UHPC. The flexural strength decreases with increasing PA content due to the combined effects of flocculation and the toughening effect of steel fiber. PA causes flocculation, which resists compressive forces better than tensile or flexural stresses. Flocs increase with PA concentration, lowering tensile, and flexural strengths. However, a UHPC mixture that contained 10% PA, or UHPC10, showed flexural strength that was comparable to conventional UHPC, or UHPC0. At 7, 14, 28, and 90 days, the UHPC10 mixture’s flexural strength had decreased by 27.27, 33.33, 13.04, and 11.53%, respectively. Concrete mixtures UHPC5, UHPC15, and UHPC20 all showed reduced flexural strengths at 7 days of curing age compared to conventional UHPC, or UHPC0, of 18.18, 40.9, and 36.36%, respectively. Similar to the conventional UHPC, or UHPC0, at 14 days, these UHPC combinations showed decreased flexural strengths of 13.33, 6.66, and 26.66%, respectively. These PA-modified UHPC mixtures lost 17.39, 21.73, and 30.43% of their flexural strength after 28 days of curing, respectively. The loss in flexural strength of these UHPC mixtures treated with PA after 90 days of curing age was 15.38, 19.23, and 30.76%, respectively.

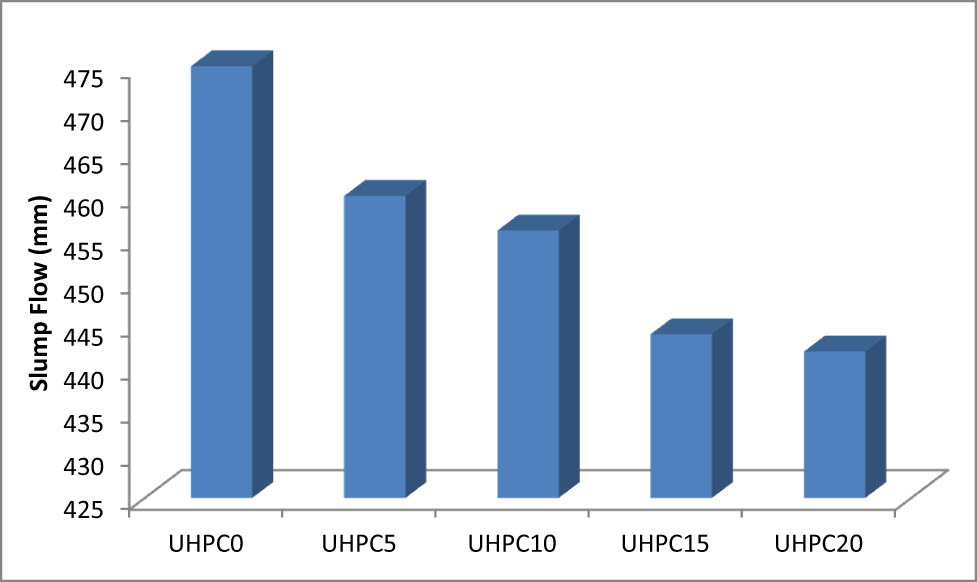

3.4 Workability

The quantity of fines and the characteristics of the fine aggregate used in the concrete determine its desired workability. NRS is made up of compact particles that lose their shape and smoothen as a result of weathering. Mica and other weak minerals are taken out of it. PA particles, on the other hand, are angular, rough in texture, and porous. Comparing NRS to PA, the PA contains a greater amount of particles that are smaller than 75 µm. As a result, when PA is used in place of natural sand in concrete, the number of fines and irregularly shaped, rough-textured, and porous particles increases, increasing the friction between the particles. Fresh concrete’s flow properties are hindered by the increased interparticle friction. Additionally, because PA has a significantly higher water absorption ratio than natural sand, a portion of the water is absorbed internally by the porous PA particles, reducing the amount of water that can be used to lubricate the particles to obtain the appropriate workability. As a result, using PA in place of sand affects the workability of concrete at a certain water cement ratio. According to the published research results, using PA instead of sand increases the water requirement for the same slump of concrete. The slump values of various concrete mixtures along with the fluctuation in slump flow are shown in Figure 9.

Variation of slump flow of UHPC mixes with different PA contents.

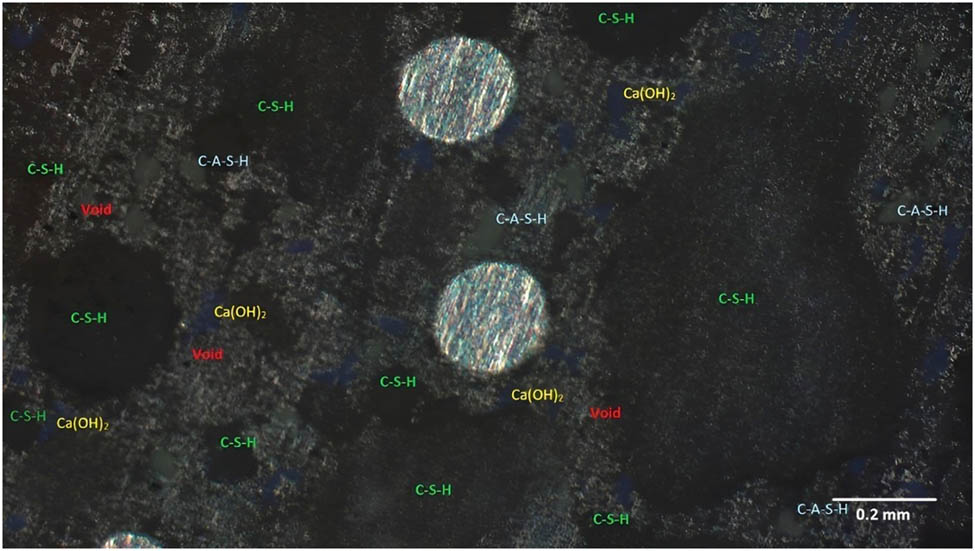

3.5 Microstructure analysis

Utilizing a petrographic image analysis, the microstructure of the hardened paste and the ITZ between the aggregate and the cement paste were examined to comprehend the strength mechanism of UHPC. The fractured specimen of UHPC was cut up into small pieces to provide samples for analysis.

The binder granules were near one another because of the exceptionally low water/binder ratio, causing very little porosity. The UHPC matrix is extremely dense and primarily made up of hydration products that resemble a gels that have been created by a diffusion process. A homogenous morphology of CSH gel makes up the majority of the image in Figure 10 and is the principal hydration product. However, there are also a few crystals of calcium hydroxide, i.e., Ca(OH)2, and calcium alumino silicate hydrates, i.e., CASH [34].

Optical image of UHPC at 50×.

Figure 10 illustrates the exceptionally dense microstructure of UHPC with 10% PA replacement. The low water-to-binder ratio results in a compact arrangement of cement particles, which, combined with the pozzolanic activity of GGBS and microsilica, minimizes voids and enhances the material’s density. The primary hydration product, calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel, dominates the microstructure, contributing to the material’s strength. The homogenous morphology of the C–S–H gel indicates effective pozzolanic reactions and improved mechanical properties [17].

The development of the microstructure post-hydration is shown in Figure 10.

About 70% of the solids volume and the source of the material’s improved strength, calcium silicate hydrates, i.e., CSH gel make up the majority of the UHPC sample.

About 20% of the solids’ volume is made up of hexagonal-shaped calcium hydroxide crystals, i.e., Ca(OH)2.

The prismatic crystals known as calcium aluminosilicate hydrates, i.e., CASH, have needle-like shapes. CASH makes up around 8% of the solids volume of hydrated concrete.

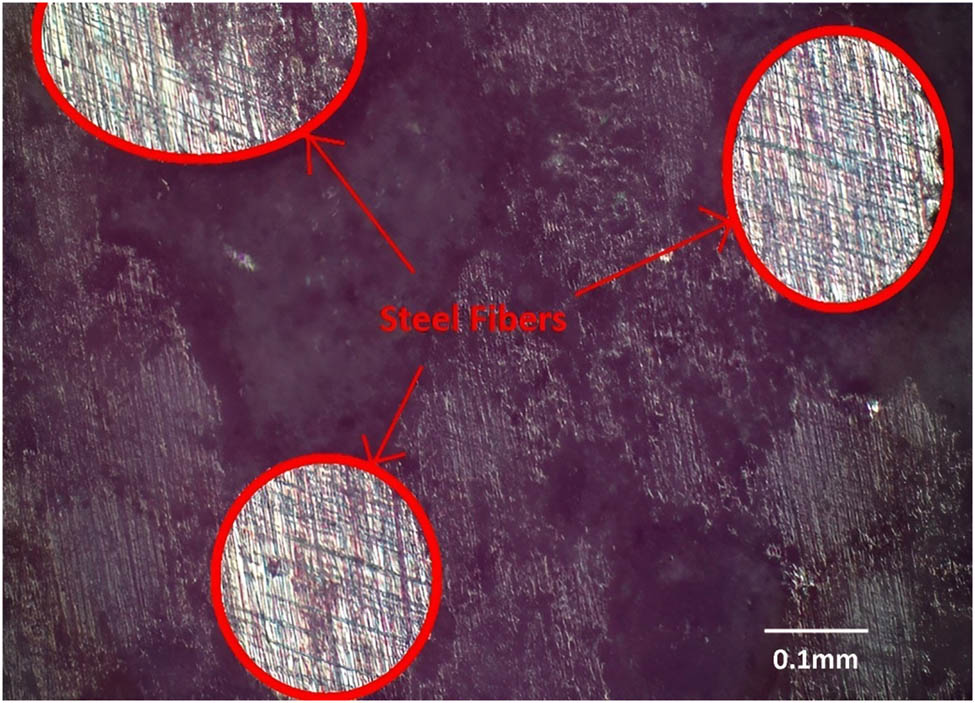

Different steel fibers found in UHPC are depicted in Figure 11 with red boundaries. Figure 11 highlights the distribution of steel fibers within the UHPC matrix. The strong bond between the steel fibers and the cement paste enhances the tensile and flexural properties of the concrete. The well-distributed fibers act as crack arrestors, preventing the propagation of microcracks and enhancing the durability of UHPC.

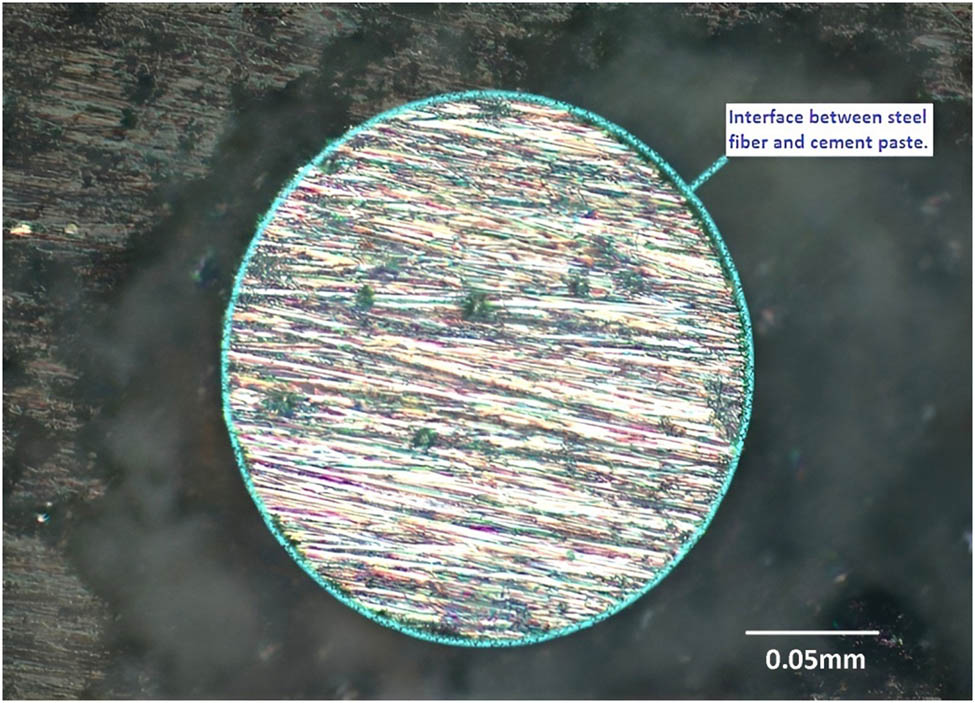

Optical image of UHPC at 100×.

Figure 12 shows the ITZ structure, which is critical for the composite action between the paste and the aggregate. The UHPC with 10% PA exhibits a denser ITZ with fewer microcracks compared to higher replacement levels. This denser ITZ is attributed to the optimal filler effect of PA, which improves the packing density and reduces the porosity at the interface. The well-distributed fibers act as crack arrestors, preventing the propagation of microcracks and enhancing the durability of UHPC, while the interface between steel fiber and cement paste is represented in Figure 12 with a blue boundary. Steel fiber–matrix bond qualities have a significant impact on the mechanical properties of steel fiber-reinforced concrete. The tension is transferred between the fiber–matrix phases through the fiber–matrix bond. The main element influencing bond strength is the fiber–matrix interface characteristic (fiber–matrix transition zone).

Optical image of UHPC at 200×.

The decrease in ITZ cracks indicates a tighter link between the cement matrix and aggregate at the interface, which increases interface strength and raises compressive strength. When PA replacement was at 10%, the initial ITZ crack was practically nonexistent. When PA replacement reached 20%, the UHPC fluidity increased quickly, the bonding power at interfaces between the cement paste and the aggregate reduced, and some cracks started to appear in the ITZ, which causes slight drop in compressive strength [35].

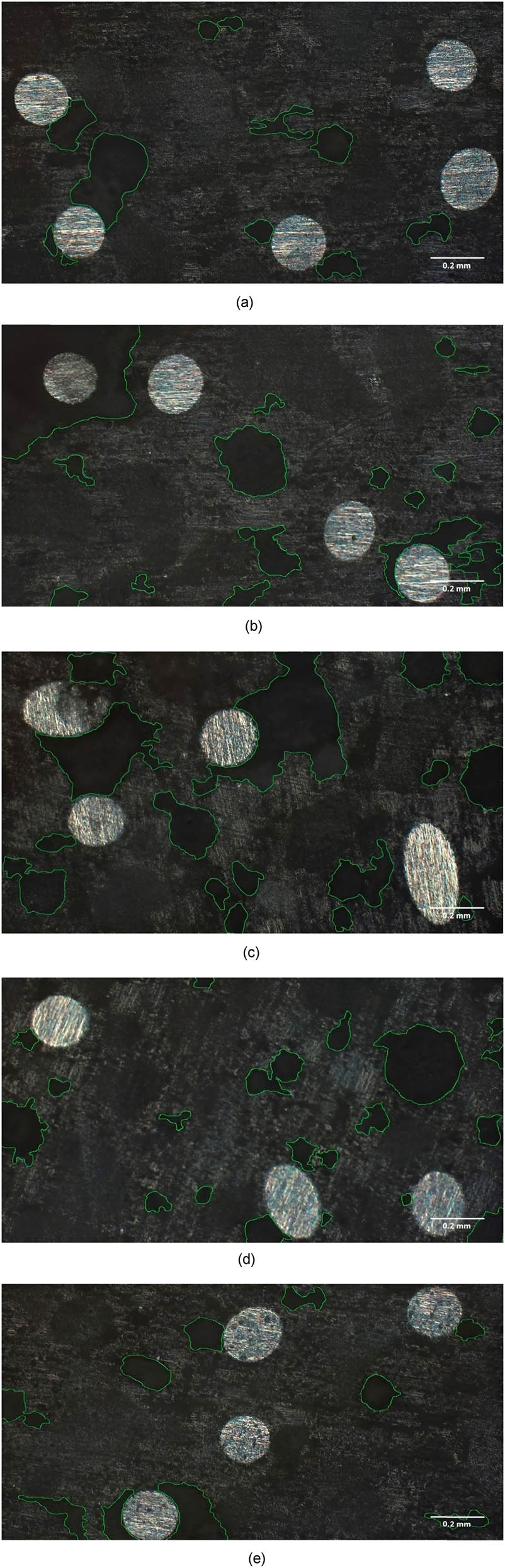

The change in hydration gel formation in the UHPC at day 28 is depicted in Figure 13(a)–(e) and it compares the hydration gel formation at different PA replacement levels. The C–S–H gel is indicated by a defined area with a green boundary. The maximum surface area of the C–S–H gel is observed at 10% PA replacement (Figure 13c), indicating the optimal pozzolanic activity and enhanced microstructural integrity. In contrast, higher replacement levels (Figure 13d and e) show a decrease in C–S–H gel formation, leading to increased porosity and reduced mechanical strength.

(a) Optical image of UHPC0 at 50×. (b) Optical image of UHPC5 at 50×. (c) Optical image of UHPC10 at 50×. (d) Optical image of UHPC15 at 50×. (e) Optical image of UHPC20 at 50×.

The microstructural analysis confirms that the incorporation of 10% PA in UHPC not only improves the material’s density and reduces porosity but also enhances the bond strength at the ITZ. These microstructural improvements directly contribute to the observed enhancements in compressive, tensile, and flexural properties, validating the optimal replacement level of PA in UHPC.

4 Conclusions

From the aforementioned findings, it can be inferred that UHPC can be produced using standard technology with high binder content, several additions of fly ash, microsilica, GGBS, and PA, an exceptionally low W/B ratio, and a high standard SP. The UHPC10 performed brilliantly in our study, with a slump of 456 mm and the highest compressive strengths of 98 MPa at 28 days and 117 MPa at 90 days. The bulk density of 2,450 kg/m3 and the specific density of 2,600 kg/m3 for the UHPC hardened concrete were obtained. For the preparation to be effective, it is found that a water binder ratio of 0.21, 1,200 kg/m3 of cementitious material, made up of 50% cement, 17% fly ash, 13% GGBS, 12% microsilica, and 8% PA, and an acceptable dosage of SP to guarantee optimal fluidity are necessary.

The following inferences are drawn from the findings of the fractional replacement of cement with GGBS and the 0–20% replacement of river sand with PA:

When compared to conventional UHPC, the UHPC incorporating GGBS and PA demonstrated enhanced mechanical properties.

Specifically, replacing up to 20% of cement with GGBS and up to 10% of river sand with PA resulted in significant strength improvements. The UHPC with 10% PA replacement achieved a compressive strength of 117 MPa at 90 days, compared to 108 MPa for conventional UHPC. The optimal replacement level for PA was identified as 10%, beyond which the strength gains diminished.

The workability, indicated by slump flow, showed acceptable values around 450 mm, with the UHPC containing 10% PA exhibiting a slump flow of 456 mm.

Microstructural analysis reveals that incorporating 10% PA in UHPC enhances material density, reduces porosity, and strengthens the ITZ bond. These improvements directly contribute to increased compressive, tensile, and flexural properties, confirming the optimal replacement level.

These findings suggest that moderate amounts of GGBS and PA can be effectively substituted in UHPC to enhance its strength and sustainability without compromising its performance.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. AS: conceptualization, methodology, data collection, writing – original draft, figure creation. RN: supervision, writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

References

[1] Zhao J, Sufian M, Abuhussain MA, Althoey F, Deifalla AF. Exploring the potential of agricultural waste as an additive in ultra-high-performance concrete for sustainable construction: A comprehensive review. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2024;63(1):20230181.10.1515/rams-2023-0181Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Junjie Z, Raza A, Weicheng F, Chengfang Y. Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature. Sci Eng Compos Mater. 2024;31(1):20240011.10.1515/secm-2024-0011Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Akeed MH, Qaidi S, Faraj RH, Majeed SS, Mohammed AS, Emad W, et al. Ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Part V: Mixture design, preparation, mixing, casting, and curing. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022 Dec;17:e01363.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01363Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Azmee NM, Shafiq N. Ultra-high performance concrete: From fundamental to applications. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2018 Dec;9:e00197.10.1016/j.cscm.2018.e00197Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Du J, Meng W, Khayat KH, Bao Y, Guo P, Lyu Z, et al. New development of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). Compos Part B: Eng. 2021 Nov;224:109220.10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109220Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Soni A, Nateriya R, Senapati T. Probabilistic dual hesitant Archimedean–Dombi operators for selection of sustainable materials. Soft Comput. 2023;8:1–7.10.1007/s00500-023-08679-8Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Dixit A, Du H, Pang SD. Marine clay in ultra-high performance concrete for filler substitution. Constr Build Mater. 2020;263:120250.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120250Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Rentier ES, Cammeraat LH. The environmental impacts of river sand mining. Sci Total Environ. 2022 Sep;838:155877.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155877Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Yang R, Yu R, Shui Z, Gao X, Xiao X, Fan D, et al. Feasibility analysis of treating recycled rock dust as an environmentally friendly alternative material in Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC). J Clean Prod. 2020;258:120673.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120673Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Ban CC, Kang SY, Siddique R, Tangchirapat W. Properties of ultra-high performance concrete and conventional concrete with coal bottom ash as aggregate replacement and nanoadditives: A review. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2023;62(1):20220323.10.1515/rams-2022-0323Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Pyo S, Kim HK. Fresh and hardened properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating coal bottom ash and slag powder. Constr Build Mater. 2017 Jan;131:459–66.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.10.109Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Lal D, Chatterjee A, Dwivedi A. Investigation of properties of cement mortar incorporating pond ash – An environmental sustainable material. Constr Build Mater. 2019;209:20–31.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.049Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Sofi A, Phanikumar BR. An experimental investigation on flexural behaviour of fibre-reinforced pond ash-modified concrete. Ain Shams Eng J. 2015;6(4):1133–42.10.1016/j.asej.2015.03.008Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Wang W-C, Xue J-C, Huang C-Y, Chang H-C. Incineration bottom ash as aggregate for controlled low strength materials: Implications and coping strategies. J Adv Concr Technol. 2023;21(11):837–50.10.3151/jact.21.837Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Singh M, Siddique R. Effect of coal bottom ash as partial replacement of sand on properties of concrete. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2013;72:20–32.10.1016/j.resconrec.2012.12.006Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Bera AK, Ghosh A, Ghosh A. Compaction characteristics of pond ash. J Mater Civ Eng. 2007;349(April):349–57.10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2007)19:4(349)Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Wang C, Yang C, Liu F, Wan C, Pu X. Preparation of ultra-high performance concrete with common technology and materials. Cem Concr Compos. 2012;34(4):538–44.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2011.11.005Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Aswed KK, Hassan MS, Al-Quraishi H. Optimisation and prediction of fresh ultra-high-performance concrete properties enhanced with nanosilica. J Adv Concr Technol. 2022;20(2):103–16.10.3151/jact.20.103Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Ma Z, Zhao T, Yao X. Influence of applied loads on the permeability behavior of ultra high performance concrete with steel fibers. J Adv Concr Technol. 2016;14(12):770–81.10.3151/jact.14.770Suche in Google Scholar

[20] IS-1727. Method of test for pozzolanic materials. New Delhi: Bureau of Indian Standards; 1967.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Bajaber MA, Hakeem IY. UHPC evolution, development, and utilization in construction: A review. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;10:1058–74.10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.12.051Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Peng Y, Li X, Liu Y, Zhan B, Xu G. Optimization for mix proportion of reactive powder concrete containing phosphorous slag by using packing model. J Adv Concr Technol. 2020;18(9):481–92.10.3151/jact.18.481Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Shi C, Wu Z, Xiao J, Wang D, Huang Z, Fang Z. A review on ultra high performance concrete: Part I. Raw materials and mixture design. Constr Build Mater. 2015;101:741–51.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.10.088Suche in Google Scholar

[24] IS 10262. Concrete Mix Proportioning- Guidelines. Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS); 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] IS 516. Method of Tests for Strength of Concrete. Bureau of Indian Standards; 1959.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Tahwia AM, Elgendy GM, Amin M. Mechanical properties of affordable and sustainable ultra-high-performance concrete. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;16(March):e01069.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01069Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Phanikumar BR, Sofi A. Effect of pond ash and steel fibre on engineering properties of concrete. Ain Shams Eng J. 2016;7(1):89–99.10.1016/j.asej.2015.03.009Suche in Google Scholar

[28] IS 5816-1999. Indian standard Splitting tensile strength of concrete- method of test. Bureau of Indian Standards; 1999.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Verma P, Dhurvey P, Sundramurthy VP. Potential assessment of E-waste plastic in metakaolin based geopolymer using petrography image analysis. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2022;2022(1):7790320.10.1155/2022/7790320Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Kang SH, Hong SG, Moon J. The use of rice husk ash as reactive filler in ultra-high performance concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2019;115:389–400.10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.09.004Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Mohammed AN, Johari MAM, Zeyad AM, Tayeh BA, Yusuf MO. Improving the engineering and fluid transport properties of ultra-high strength concrete utilizing ultrafine palm oil fuel ash. J Adv Concr Technol. 2014;12(4):127–37.10.3151/jact.12.127Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Siddique R, Singh M, Mehta S, Belarbi R. Utilization of treated saw dust in concrete as partial replacement of natural sand. J Clean Prod. 2020;261:121226.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121226Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Ganesh P, Murthy AR. Tensile behaviour and durability aspects of sustainable ultra-high performance concrete incorporated with GGBS as cementitious material. Constr Build Mater. 2019;197:667–80.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.240Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Yazici H, Deniz E, Baradan B. The effect of autoclave pressure, temperature and duration time on mechanical properties of reactive powder concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2013;42:53–63.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.01.003Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Jiao Y, Zhang Y, Guo M, Zhang L, Ning H, Liu S. Mechanical and fracture properties of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) containing waste glass sand as partial replacement material. J Clean Prod. 2020;277:123501.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123501Suche in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective