Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

-

Muhammad Umar

, Hui Qian

, Hamad Almujibah

Abstract

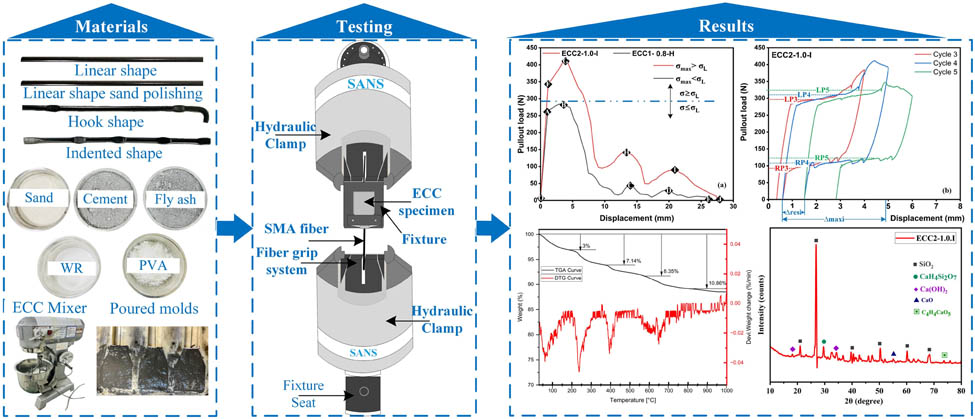

This study explores the effect of integrated superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers (SMAFs) on the mechanical performance of engineered cementitious composites (ECCs). Various SMAF configurations – linear-shaped SMAFs (LS-SMAFs), hook-shaped SMAFs (HS-SMAFs), and indented-shaped SMAFs (IS-SMAFs) – with diameters of 0.8 and 1.0 mm were incorporated into ECC matrices, and surface texturization was achieved through abrasive paper treatment. Their mechanical properties were assessed through single fiber pullout tests on ECC mixtures containing 1.5 and 2.0% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), subjected to both monotonic and cyclic loading conditions. Qualitative analysis, employing scanning electron microscopy, demonstrated that the IS-SMAF configuration provided superior mechanical interlocking and fiber–matrix adhesion, with a distinct flag shape observed during tensile testing. Quantitative data indicated that IS-SMAFs significantly improved the tensile strength and pullout resistance, with slip distances of ≥5 mm and average pullout loads ranging from 263 to 403 N. LS-SMAFs demonstrated better performance compared to HS-SMAFs and LS-SMAFs in terms of tensile and pullout characteristics. Additionally, ECCs with increased PVA content exhibited enhanced withdrawal performance. Thermogravimetry analysis and X-ray diffraction provided insights into the high-temperature stability and crystalline structure of the composites. These results underscore the effectiveness of IS-SMAFs in enhancing ECC properties, offering significant implications for the development and optimization of high-performance composite materials in civil engineering applications.

Graphical abstract

Nomenclature

- LS-SMAF

-

linear-shaped shape-memory alloy fiber

- HS-SMAF

-

hook-shaped shape-memory alloy fiber

- ISSMAF

-

indented-shaped shape-memory alloy fiber

- ECC

-

engineered cementitious composite

- SMAF-ECC

-

SMAF-reinforced engineered cementitious composite

- TGA

-

thermogravimetry analysis

- DTG

-

differential thermogravimetry

- SEM

-

scanning electron microscopy

- SCMs

-

supplementary cementitious materials

- A f

-

austenite temperature

- M f

-

martensite temperature

- SME

-

shape-memory effect

- SE

-

superelasticity

- HSECC

-

high-strength engineered cementitious composites

- PVA

-

polyvinyl alcohol

- SCR

-

self-centering ratio

- XRD

-

X-ray diffraction

- SMA

-

shape-memory alloy

1 Introduction

Concrete is widely used in the construction industry. However, conventional concrete materials have limitations such as poor strain softening, limited impact resistance, inadequate tensile strength, and significant fracture width. These limitations increase the vulnerability of internal steel reinforcement to corrosion [1,2,3]. To address these limitations, advanced fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) has been developed. This involves combining several high-performance fibers with concrete components to overcome the drawbacks of conventional concrete and meet modern construction requirements [4,5]. Being a significant invention from the University of Michigan in the early 1990s, engineered cementitious composites (ECCs) are cementitious composite materials with randomly distributed short fibers that provide remarkable toughness, tensile strength, and fracture resistance [6,7,8]. Unlike FRC and regular concrete, strain hardening occurs in ECC during cracking. Because ECC has a tensile strain capacity that is 300–500 times greater than conventional concrete, it will eventually break by creating many small, uniformly distributed cracks. Additionally, ECC exhibits damage tolerance and energy dissipation capability, which makes it a popular choice for improving the seismic performance of buildings [9,10,11]. In addition to conventional concrete or mortar, ECC exhibits significantly greater tensile deformation capacity, making it highly compatible with shape-memory alloy fibers (SMAFs) [12,13]. Furthermore, ECC’s wide crack distribution and small crack width facilitate the increased engagement of SMAFs, easing the challenge of closing cracks for these fibers [14,15].

In recent years, various approaches have been explored to enhance the mechanical properties and durability of concrete composites, making them less brittle and more resistant to cracking [16,17]. While the use of SMAFs has been a promising avenue, other methods have also shown significant potential. For example, recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of combining different additives and nano-additives to achieve a synergistic effect that improves the fracture behavior and durability of cementitious materials. Research studies such as the investigation of pozzolans and nano-additives on crack formation in concretes [18], the enhancement of fracture behavior using fly ash and nanosilica [19], and the mechanical properties of concrete modified with fly ash, silica fume, and nanosilica [20] highlight the advancements in this field. Additionally, the use of industrial waste in concrete, as discussed in recent literature [21], further emphasizes the diverse strategies available for improving the performance of concrete composites.

SMA has emerged as an innovative option for reinforcing concrete with its unique capability to close cracks (re-centering) [22,23,24]. Superelastic or pseudoelastic SMA, which exhibits flag-shaped behavior, a characteristic of superelasticity (SE), improves self-centering and provides additional energy dissipation. These alloys thus play a role in self-centering devices for different systems or structures. As shown in Figure 1, internal initiation of the superelastic behavior of SMA apart from the shape-memory effect (SME) is possible without external stimuli such as heating. The shape recovery in SMA results from a reversible solid-phase transformation, transitioning from austenite to martensite [25,26,27]. The SME in SMA occurs when the SMA is subjected to loading below the martensite completion temperature (M f), where only martensite crystals are present. This loading induces plastic deformation, with the applied stress being lower than the permanent yield stress. By heating the SMA to the austenite completion temperature (A f) above, the recovery of the plastic deformation is achievable, and the recovery deformation can reach 8–10%. On the other hand, SE in SMAs occurs when the material is at a temperature higher than A f, having only austenite crystals. Plastic deformation occurs during loading, and the strain is recovered without heating upon unloading. The recovery deformation in SE can also reach 8–10% [28,29].

Schematic diagram of SMA’s SME and SE.

SMA materials are traditionally formed into rods, bars, or strands for various applications [30,31,32,33,34]. However, these shapes are less than ideal for integration with existing steel reinforcement in concrete. To overcome this hurdle, researchers have explored using short, randomly distributed SMAFs within the concrete matrix. This approach offers better compatibility, but a major challenge remains: achieving a strong bond between the smooth surface of the fibers and the surrounding concrete. This weak bond currently leads to weak pullout performance [35,36]. Efforts to improve the bond strength between SMAFs and concrete have yielded promising results. Studies indicate that modifying fiber ends with shapes like 45° hooks and spearheads significantly enhances adhesion and energy dissipation within the concrete matrix [37,38,39]. In addition to the experimental work presented in this study, computational methods such as the conformal phase field method and the multiscale framework PERMIX offer powerful tools for understanding the underlying physics of fiber pullout behavior. These methods, as demonstrated in previous studies [40,41,42], can provide deeper insights into the interaction between SMAFs and the ECC matrix. Future work could integrate these computational approaches to complement the experimental findings and further clarify the mechanics of fiber pullout. Additionally, increasing the diameter of SMAFs has been linked to improved self-centering capacity in cementitious composites [43,44]. However, challenges persist. While larger diameter crimped fibers can generate higher pullout stress, the inherent brittleness of concrete itself limits the full potential of SMA performance, as highlighted by Ho et al. [45]. Studies of Chen et al., Ali and Nehdi [14,46] indicate increases of 40% in flexural strength and 36.1% in the self-centering rate for ECC beams containing SMAFs compared to control specimens.

While previous research has explored the influence of fiber shape, cementitious materials, and the overall ECC matrix on the bond-slip behavior of superelastic SMAFs within cementitious ECC mixtures [38,39,47,48,49,50,51], a comprehensive and systematic investigation of pullout behavior in SMA fiber-reinforced engineered cementitious composite (SMAF-ECC) matrices remains limited. This study addresses this gap by introducing a novel SMAF design with unique geometries and surface treatment. The novelty of this research lies in its systematic investigation of the pullout behavior of SMAFs in ECC matrices. This study introduces new SMAF designs with unique geometries and surface treatments, addressing a critical gap in the current literature. This research evaluates the impact of these design modifications on bonding properties, interfacial behavior, and stress distribution within the ECC matrix. The integration of SMAFs with advanced concrete technology promises significant improvements in mechanical performance, crack management, and structural resilience. By exploring these novel SMAF designs, this study aims to enhance the practical application of SMAFs in high-performance concrete, offering valuable insights for future developments in civil engineering.

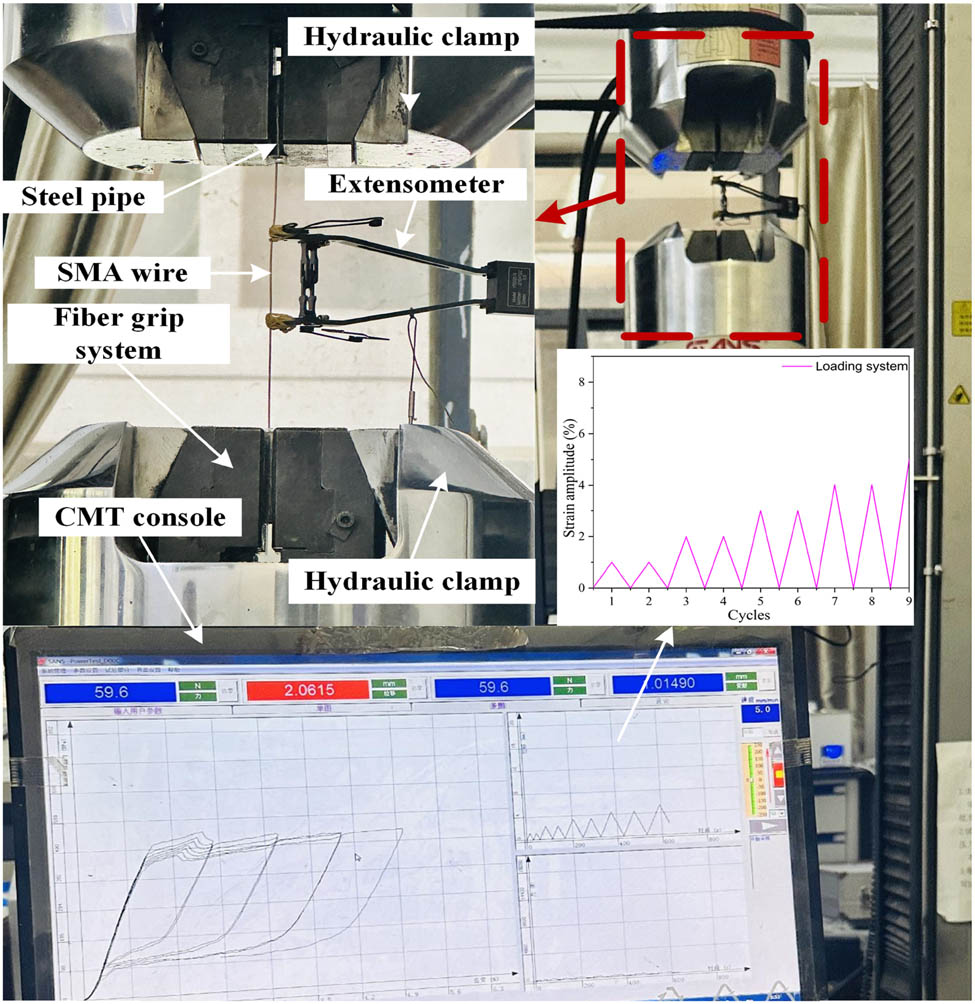

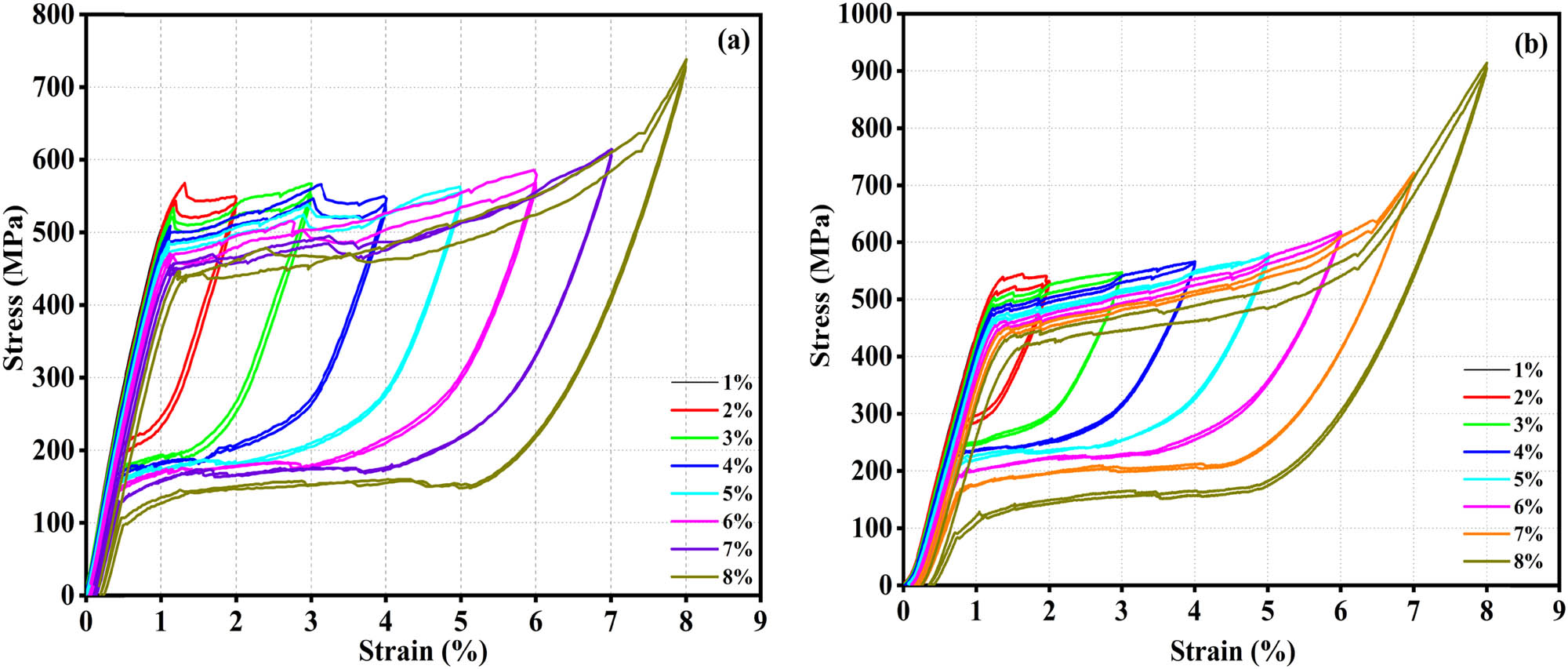

2 Tensile properties of SMA wires

Evaluating the superelastic behavior of the SMA wire required transforming it into fibers for testing due to its thinness and challenges in securing it to the testing machine [52,53]. Due to challenges in gripping the wires, they were embedded in epoxy for tensile testing. A specialized setup with a controlled testing machine was used, which is shown in Figure 2. The test involved stretching the wire at a constant temperature of 20°C in steps of 1% strain increase followed by unloading until no stress remained. This cycle was repeated twice for each strain level. The resulting stress–strain curve is shown in Figure 3, which provides key information about the SMA wire’s behavior. The initial slope indicates the stiffness, and a plateau emerges as the wire transforms from the austenitic phase to martensitic and back to austenitic [54]. Notably, at 8% strain, a segment roughly twice the wire diameter undergoes this transformation. The unloading slope and phase change stress are also influenced by the applied strain.

Schematic of the loading device and system.

SMA wire cyclic stress–strain curve: (a) 0.8 mm diameter and (b) 1.0 mm diameter.

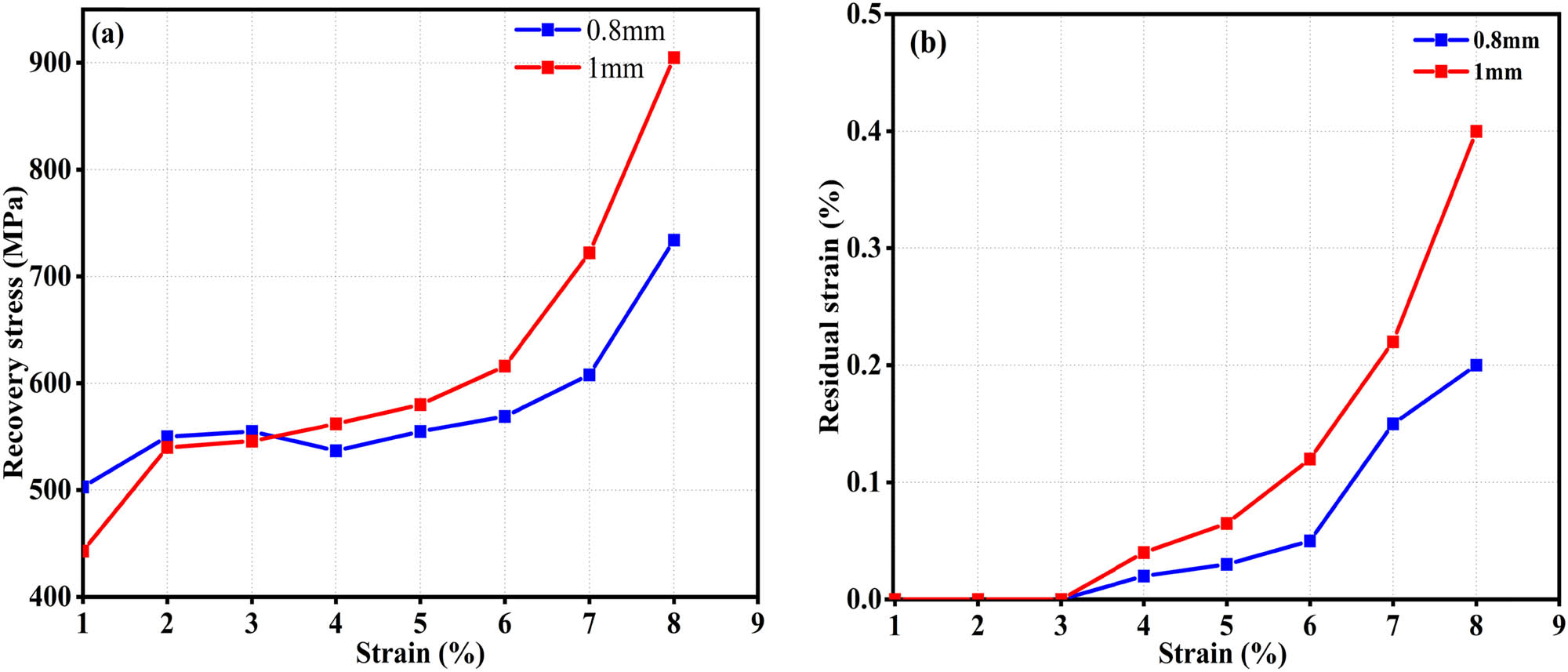

3 Internal stress and permanent deformation

Figure 4a illustrates the relationship between recovery stress and strain amplitude for SMA filaments of different diameters. The results indicate that lower strain amplitudes (0.8%) yield higher recovery stresses. This observation is crucial for applications in ECC as it suggests that SMAFs can effectively recover stress under lower strain conditions, which is beneficial for maintaining the integrity of the composite material under small deformations. For larger diameter filaments (1.0 mm), the recovery stress increases more significantly when the strain exceeds 3%. This behavior suggests that larger filaments exhibit a stronger stress response and may be more effective in applications requiring significant recovery stress, such as repair and rehabilitation of ECC structures.

(a) Restoration stress of the SMA wire. (b) Residual strain of the SMA wire.

The implication for ECC applications is that incorporating larger SMA filaments could enhance the repair capabilities of the composite by providing a more robust response to higher strain conditions. This is especially relevant for structures subject to significant deformation or seismic activity, where the increased recovery stress can help restore the structural integrity more effectively. Figure 4b reveals that SMA filaments exhibit complete shape recovery at a strain of 3%, which is ideal for closing cracks in the ECC. However, strains above 3% result in increased residual strain, with larger filaments showing a greater residual strain compared to smaller filaments. Despite this, both filament sizes retain a high recovery capacity of over 94%. This balance between deformation and recovery efficiency highlights the advantage of using larger filaments in applications requiring substantial deformation and self-healing. The significant recovery potential, even with some residual strain, underscores the suitability of SMA filaments for enhancing the self-healing properties of ECC.

4 Experimental program

4.1 Materials and fiber design

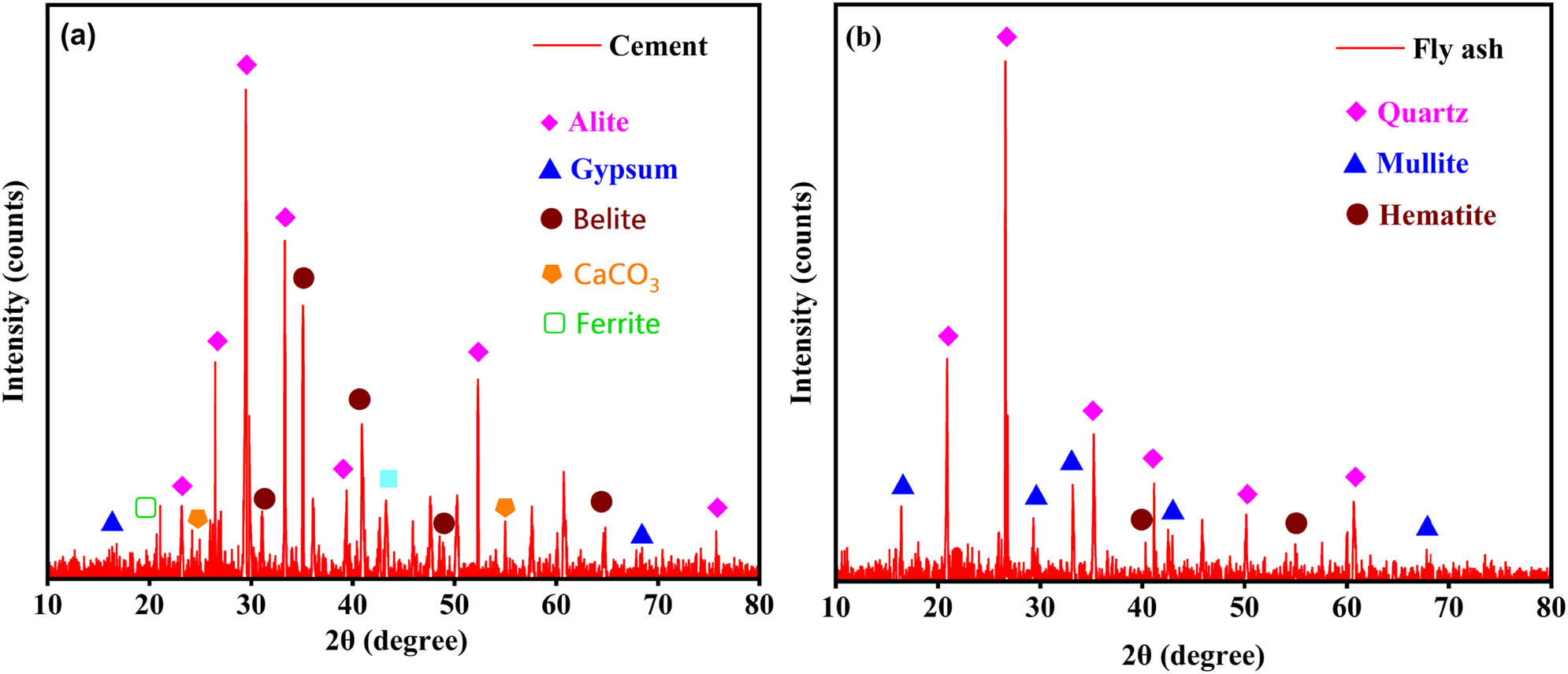

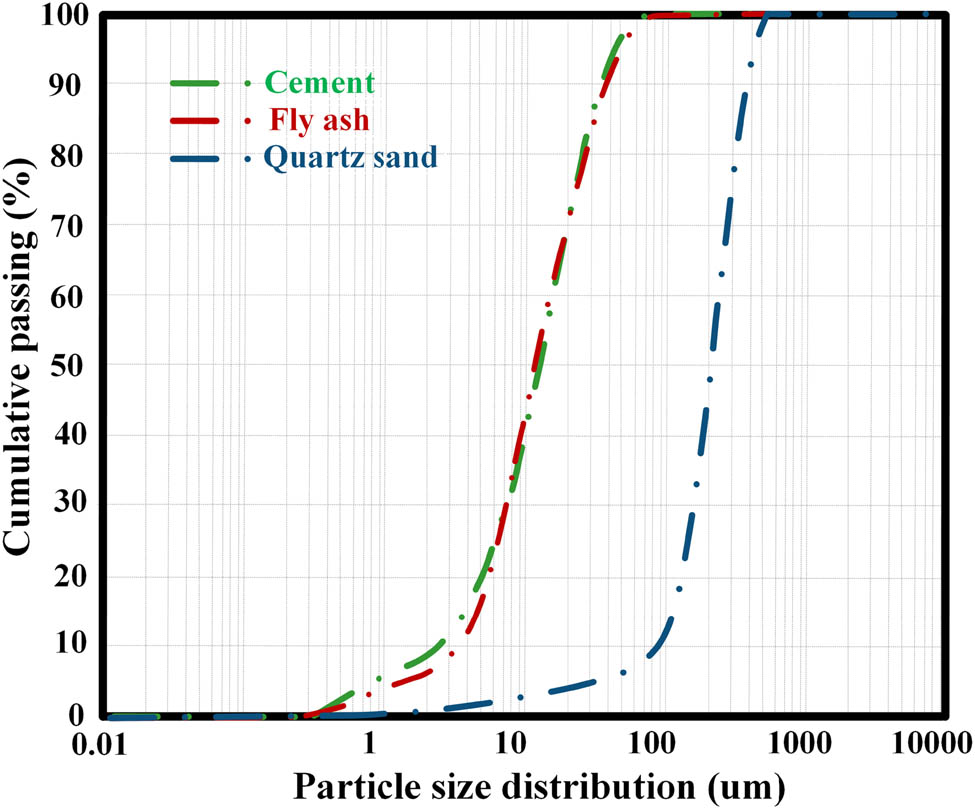

The experiment utilized Portland cement (P.O. 42.5) adhering to GB175 [55] and ASTM [56] standards, along with Class F fly ash as per ASTM standards [56]. The key oxide compositions of both cement and fly ash are detailed in Table 1. Fly ash primarily consisted of amorphous silica and aluminum oxide 79.42%, as corroborated by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) results in Figure 5. C3S and C2S were the dominant minerals in cement, with C3S constituting the highest-end members. Notably, the fly ash particles possessed a similar size to cement particles but exhibited a more spherical shape, as shown in Figure 6. This characteristic potentially enhances the packing density, flowability, and rheological properties of the cement paste, consequently improving the high-strength and high-performance concrete. Additionally, a polycarboxylic acid-based superplasticizer with a water reduction rate of 36% and a density of 1.084 g/cm³ was employed. Quartz sand, with a density of 2.54 g/cm³ and a particle size ranging from 75 to 630 μm, was incorporated. While larger than cement and fly ash particles, as shown in Figure 6, it was finer than conventional river sand used in typical concrete.

Main chemical composition of cement and fly ash

| Type | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | 24.99 | 8.26 | 4.03 | 51.42 | 3.71 |

| Fly ash | 54.84 | 24.58 | 5.85 | 5.38 | 0.85 |

XRD analysis results showing (a) cement and (b) fly ash.

Size distribution of cement, fly ash, and quartz sand particles.

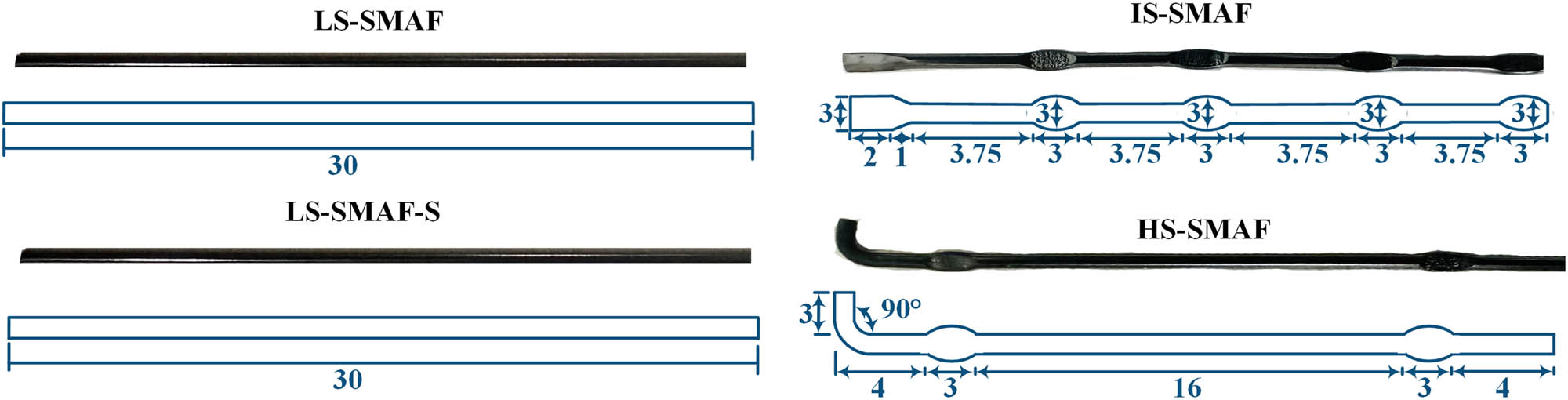

This research examined the effect of different SMAF shapes on their pullout resistance in ECC. Three different fiber shapes were created using NiTi SMA wires with diameters ranging from 0.8 to 1.0 mm. The composition and properties of these fibers are detailed in Table 2, provided by Baoji Changmao-tong Metal Materials Co., Ltd. These fibers were developed in four configurations: linear shaped SMAFs (LS-SMAF), hook-shaped SMAFs (HS-SMAF), indented-shaped SMAFs (IS-SMAF), and surface treated (sandpaper treated) linear-shaped SMAFs (LS-SMAFs-S). Figure 7 illustrates the specific shapes and dimensions of these SMAFs.

SMA chemical composition and physical properties

| Chemical composition | Ni | Fe | Nb | C | H | O | N | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass ratio (%) | 55.85 | 0.020 | 0.005 | 0.045 | 0.002 | 0.030 | 0.003 | 44.01 |

Physical properties: tensile property = 950 (MPa); elongation = 15%; grain size = Grade 7.

Shape of SMAFs embedded in the ECC matrix (units: mm).

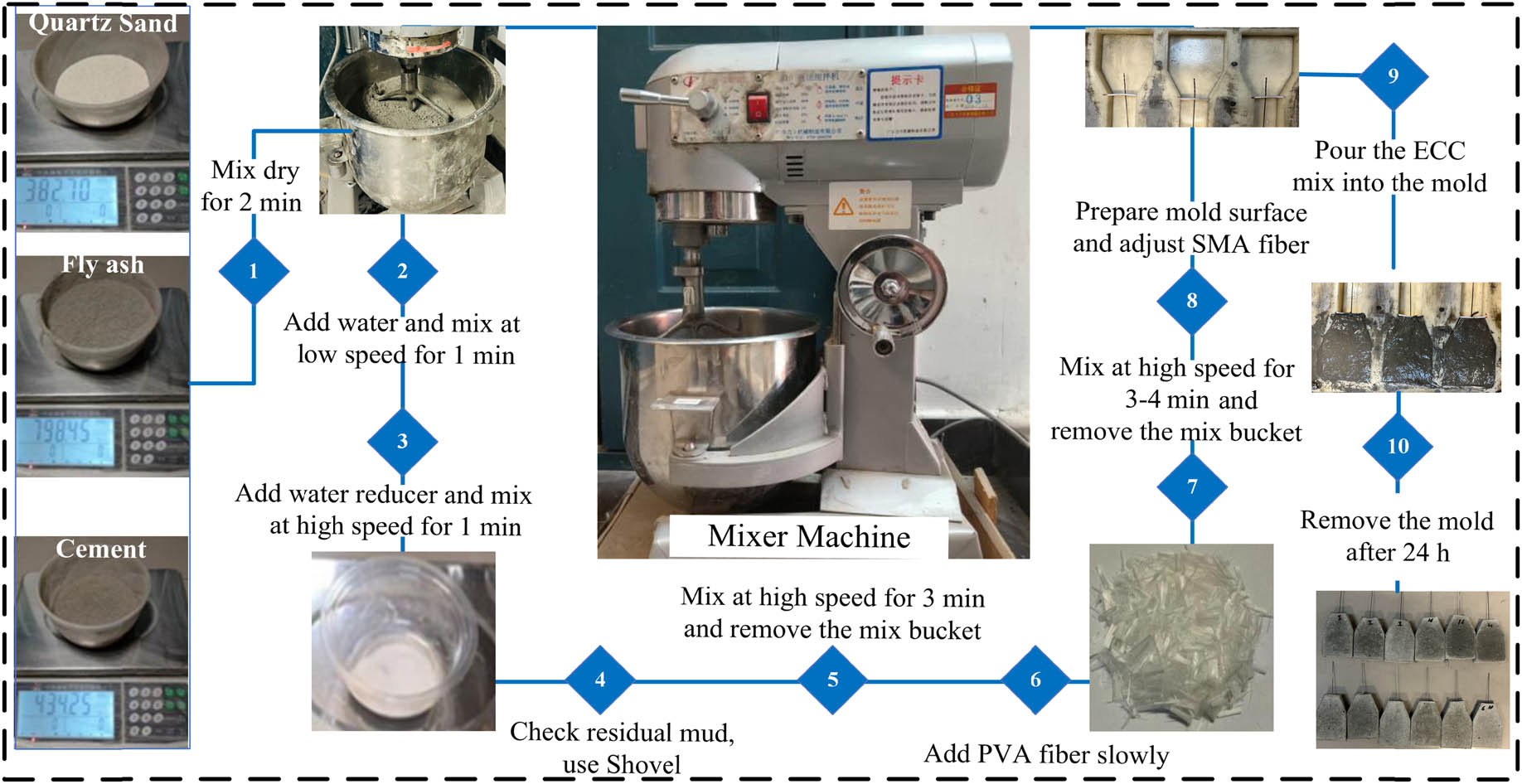

4.2 Preparation of the ECC mix

To study the pullout behavior and bond strength, ECC specimens were cast in molds shown in Figure 8. The ECC mix was prepared in a 6 L mixer. Dry ingredients of cement, fly ash, and sand were combined first, followed by gradual addition of water and mixing for 10–12 min. A high-range water reducer was then incorporated with further mixing for 3 min. Once the desired workability was achieved, the ECC mixture was ready for casting. Details on physical properties of cement and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers are provided in Table 3, while the final ECC mix composition is shown in Table 4.

Manufacturing steps for the test specimens.

Main physical properties of cement and PVA

| Cement | Fineness (m2/kg) | Initial setting (min) | Final setting (min) | Flexural strength 3/28-day (MPa) | Compressive strength 3/28-day (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 358 | 172 | 234 | 5.5/8.7 | 27.2/52.8 |

| PVA | Dia (μm) | Length (mm) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Ultimate elongation (%) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40.0 | 12.0 | 1562 | 6.5 | 41.0 |

Characteristics of the ECC matrix

| Type | Cement | Fly ash | Sand | Water | Superplasticizer | PVA (vol%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECC-1 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.012 | 2 |

| ECC-2 | 1 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.012 | 1.5 |

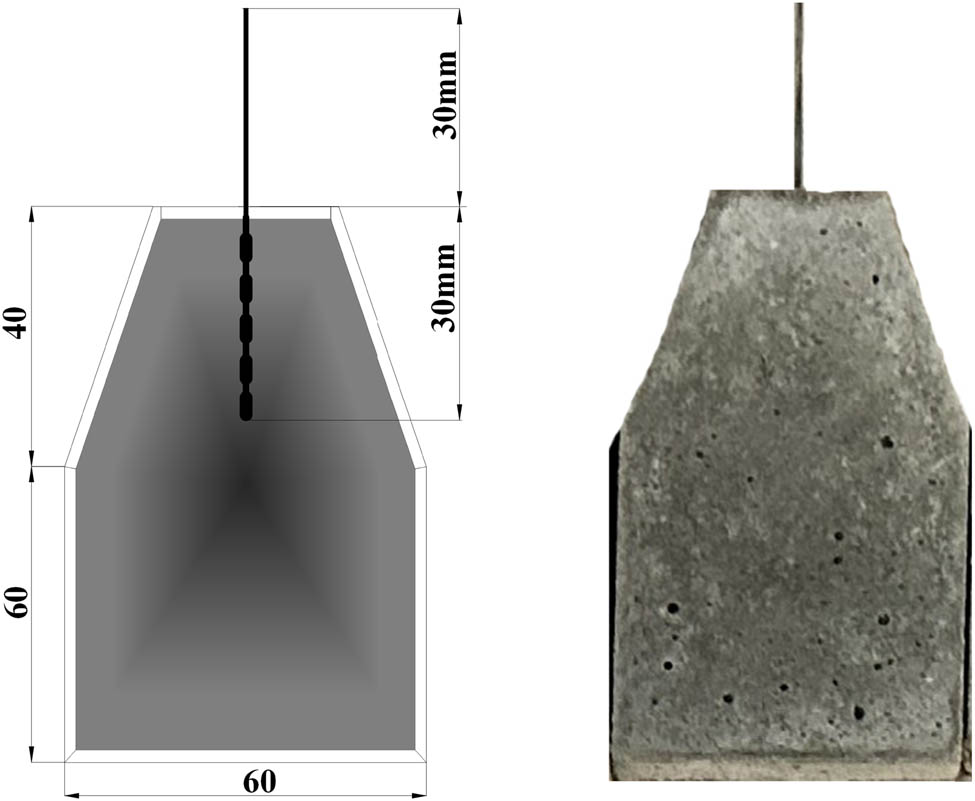

4.3 Exploring bond strength between SMAFs and the ECC matrix

Specially designed, semi-dog-bone-shaped specimens were created to assess the bond strength, as shown in Figure 9. These specimens incorporated three key variables: SMAFs with 0.8 and 1.0 mm dimensions, various shapes (LS-SMAFs, HS-SMAFs, IS-SMAFs, and LS-SMAFs-S), and a constant bonding length of 30 mm. Fabrication involves securing the fibers in a holding device, placing them in molds, and then casting the ECC mixture to fully embed the fibers. After curing, the specimens were subjected to pullout tests to evaluate the mechanical interaction between the fibers and the ECC matrix [57].

Specimen dimensions and fiber embedding.

Three samples from each unique specimen group shown in Table 5 were tested. Sample IDs encode details of fiber shape, surface treatment, diameter, and ECC mix composition. For instance, “ECC1-0.8-L” indicates a linear-shaped, 0.8 mm diameter fiber in an ECC mix with 1.5% PVA fibers. Similarly, “ECC2-1.0-L-S” represents a 1.0 mm diameter, sandpaper-treated linear fiber embedded in an ECC mix with 2% PVA fibers. Variations within indented and hook-shaped geometries (ECC2-1.0-I and ECC2-1.0-H) were also tested using 1.0 mm diameter fibers and 2% PVA content in the ECC mix.

Pullout specimen specifications

| Sr# | Specimen ID | Diameter | Fiber shape | Surface treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ECC1-1.0-L | 1.0 | LS-SMAF | — |

| 2 | ECC1-0.8-L | 0.8 | LS-SMAF | — |

| 3 | ECC1-1.0-I | 1.0 | IS -SMAF | — |

| 4 | ECC1-0.8-I | 0.8 | IS-SMAF | — |

| 5 | ECC1-1.0-H | 1.0 | HS-SMAF | — |

| 6 | ECC1-0.8-H | 0.8 | HS-SMAF | — |

| 7 | ECC2-1.0-L | 1.0 | LS-SMAF | — |

| 8 | ECC2-0.8-L | 0.8 | LS-SMAF | — |

| 9 | ECC2-1.0-I | 1.0 | IS-SMAF | — |

| 10 | ECC2-0.8-I | 0.8 | IS-SMAF | — |

| 11 | ECC2-1.0-H | 1.0 | HS-SMAF | — |

| 12 | ECC2-0.8-H | 0.8 | HS-SMAF | — |

| 13 | ECC1-1.0-L-S | 1.0 | LS-SMAF-S | Sandpaper |

| 14 | ECC1-0.8-L-S | 0.8 | LS-SMAF-S | Sandpaper |

| 15 | ECC2-1.0-L-S | 1.0 | LS-SMAF-S | Sandpaper |

| 16 | ECC2-0.8-L-S | 0.8 | LS-SMAF-S | Sandpaper |

5 Pullout test

To understand how different fiber shapes affect the pullout behavior and bond resistance of superelastic SMAFs, single fiber pullout tests were conducted using six samples for each type of fiber shape (linear, hook-shaped, and indented-shaped).

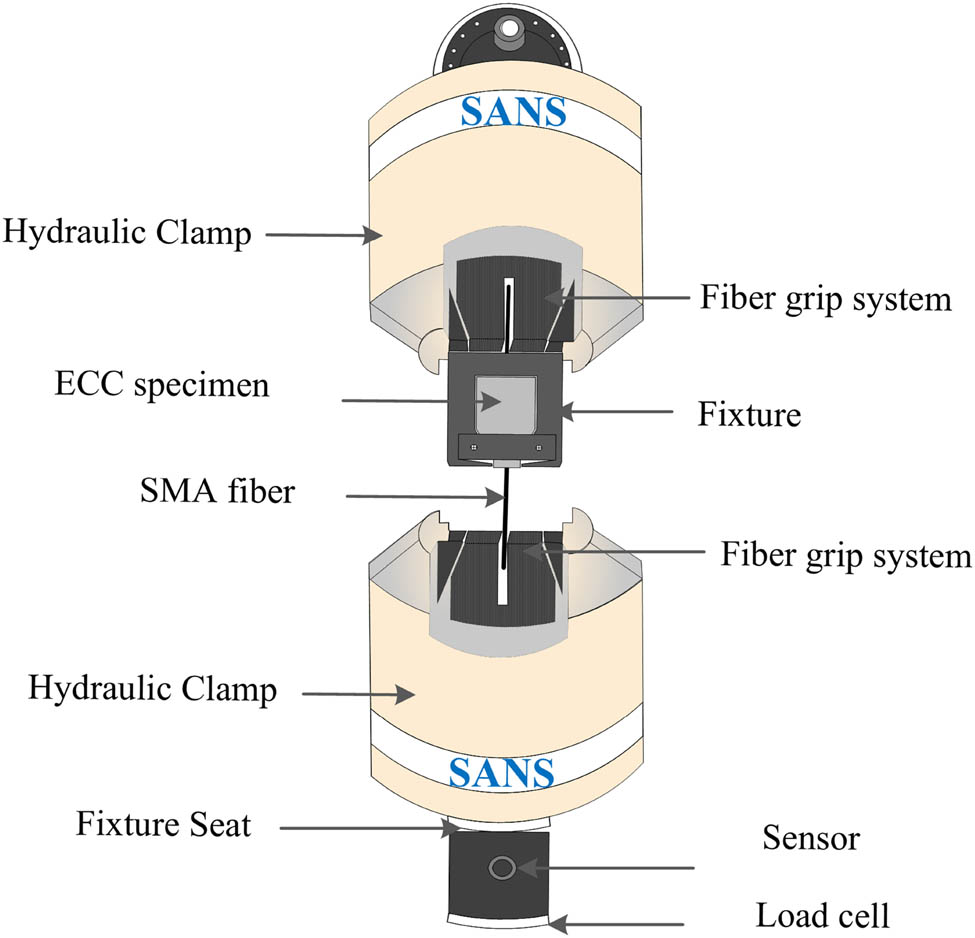

5.1 Pullout test procedure

The test setup shown in Figure 10 secured the bottom of the specimen in a special grip and actuator then pulled the fiber steadily downwards. This allowed for controlled pulling during the test. A sensor LVDT attached to the specimen monitored how much the fiber slipped within the material, while a load cell measured the applied pulling force. The test was conducted at a constant speed 5 mm/min with a frequency of 5 Hz to capture detailed data.

Illustration of the pullout test machine.

5.2 Pullout test results and discussion

To assess the performance of the SMAF pullout force, essential parameters, including the maximum pullout load

The mean bond strength

The energy dissipation by the fiber significantly influences the ultimate flexural strength, cycling load resistance, and post-cracking ductility of FRC structural members [41]. Pullout energy

The mode of failure provides additional information for evaluating the fiber extraction behavior. The published literature has identified several failure modes, including fiber pulling, rupture, and concrete cracking [38,39,61,62,63]. Failure due to fiber extraction happens when the entire embedded length is fully pulled out of the matrix, whereas partial fiber rupture occurs when the fiber breaks within the concrete but still transfers part of the load. When a fiber thoroughly penetrates the concrete, the extraction force is ineffective in moving the material [62].

5.3 Pullout behavior of SMAFs under monotonic loading

Pullout experiments were conducted to analyze the interaction between the SMAFs and the surrounding ECC matrix. The goal was to gain a comprehensive understanding of the mechanical behavior of the fibers under pulling forces, as shown in Table 6, for detailed results. Several factors contribute to the pullout resistance of the fibers, including chemical adhesion, frictional resistance, and mechanical anchorage [58]. In the case of the indented and hook-shaped fibers, mechanical anchorage played a primary role due to their geometry, leading to superior pullout performance. Notably, all specimens in these groups experienced complete pullout of the fibers without any breakage.

Summary of pullout test results: maximum load, energy dissipation, fiber stress, and bond strength

| Specimen ID | L emb (mm) | D f (mm) |

|

|

Sp (mm) | Σmax (MPa) |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECC1-0.8-L | 30 | 0.80 | 43.21 | 397.57 | 0.53 | 86.01 | 0.57 | 1.41 |

| ECC1-0.8-L-S | 30 | 0.80 | 85.61 | 536.22 | 1.58 | 170.41 | 1.14 | 1.90 |

| ECC1-0.8-H | 30 | 0.80 | 284.48 | 2122.48 | 3.44 | 566.23 | 3.77 | 7.51 |

| ECC1-0.8-I | 30 | 0.80 | 306.73 | 2780.93 | 3.70 | 610.54 | 4.07 | 9.84 |

| ECC2-0.8-L | 30 | 0.80 | 61.62 | 547.10 | 0.56 | 122.66 | 0.82 | 1.94 |

| ECC2-0.8-L-S | 30 | 0.80 | 94.19 | 555.67 | 1.33 | 187.48 | 1.25 | 1.97 |

| ECC2-0.8-H | 30 | 0.80 | 287.79 | 1837.92 | 2.29 | 572.83 | 3.82 | 6.50 |

| ECC2-0.8-I | 30 | 0.80 | 340.56 | 2871.29 | 2.32 | 677.87 | 4.52 | 10.16 |

| ECC1-1.0-L | 30 | 1.00 | 40.29 | 400.59 | 0.58 | 51.33 | 0.43 | 1.13 |

| ECC1-1.0-L-S | 30 | 1.00 | 121.70 | 776.46 | 1.40 | 155.03 | 1.29 | 2.20 |

| ECC1-1.0-H | 30 | 1.00 | 344.10 | 2568.47 | 3.71 | 438.35 | 3.65 | 7.27 |

| ECC1-1.0-I | 30 | 1.00 | 411.74 | 4131.16 | 4.77 | 524.50 | 4.37 | 11.69 |

| ECC2-1.0-L | 30 | 1.00 | 72.53 | 725.53 | 0.58 | 92.39 | 0.77 | 2.05 |

| ECC2-1.0-L-S | 30 | 1.00 | 146.76 | 949.69 | 1.61 | 186.96 | 1.56 | 2.69 |

| ECC2-1.0-H | 30 | 1.00 | 362.16 | 2321.03 | 2.16 | 461.35 | 2.86 | 6.57 |

| ECC2-1.0-I | 30 | 1.00 | 411.83 | 3466.65 | 2.39 | 524.63 | 4.37 | 9.81 |

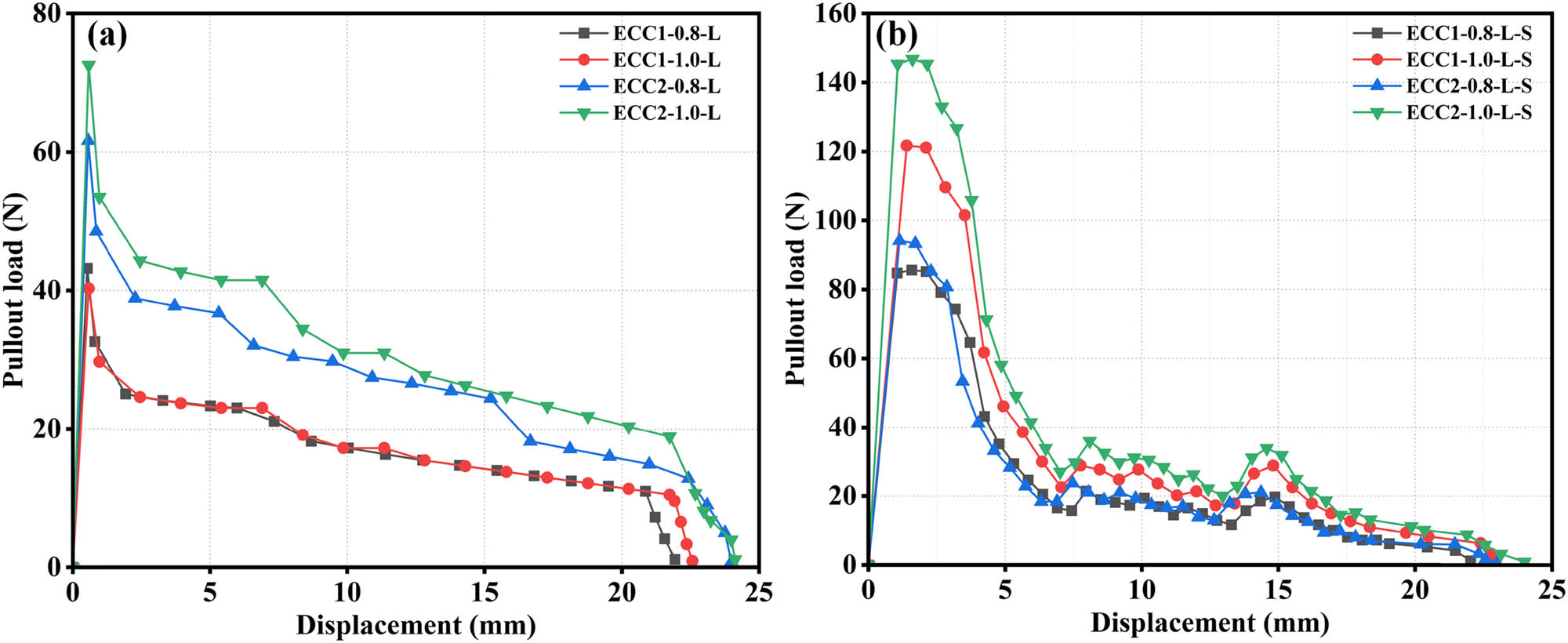

5.4 LS-SMAFs

Figure 11a illustrates the influence of fiber shape on pullout force in ECC. Straight fibers (LS-SMAFs) exhibit the lowest pullout force of 43.21 N, primarily due to their smooth surface, which offers minimal mechanical anchorage within the ECC matrix. This results in a higher slippage distance of 0.53 mm compared to fibers with an indented or hook shape.

Monotonic axial tensile test: (a) linear shaped fibers and (b) linear shaped fibers with surface treatment.

The smooth surface of straight fibers presents two significant issues: reduced physical contact with the surrounding ECC material and the absence of geometric features that could facilitate mechanical interlocking. The smooth texture limits the fiber’s ability to engage with the matrix effectively, relying predominantly on adhesive bonding and the minimal friction generated by the smooth surface. Consequently, straight fibers exhibit a lower pullout resistance, which highlights the need for fibers with more complex geometries to improve mechanical interlocking and the overall performance in ECC applications.

5.5 LS-SMAFs-S

Figure 11b reveals a substantial improvement in pullout force for linear-shaped fibers that have been treated with sandpaper compared to untreated fibers. The roughened fibers demonstrate a significant increase in pullout force, reaching an average maximum of approximately 146.7 N at larger displacement of 1.58 mm.

This enhancement is attributed to the sandpaper treatment, which creates a rough surface that improves mechanical anchorage within the ECC matrix. The roughened texture acts like small hooks, enhancing the mechanical interlocking between the fiber and the ECC material. This increased surface roughness enhances adhesion and friction, making it more difficult to pull the fibers out and thus requiring a greater pullout force. The results underscore the effectiveness of surface roughening in improving fiber performance in ECC applications [64].

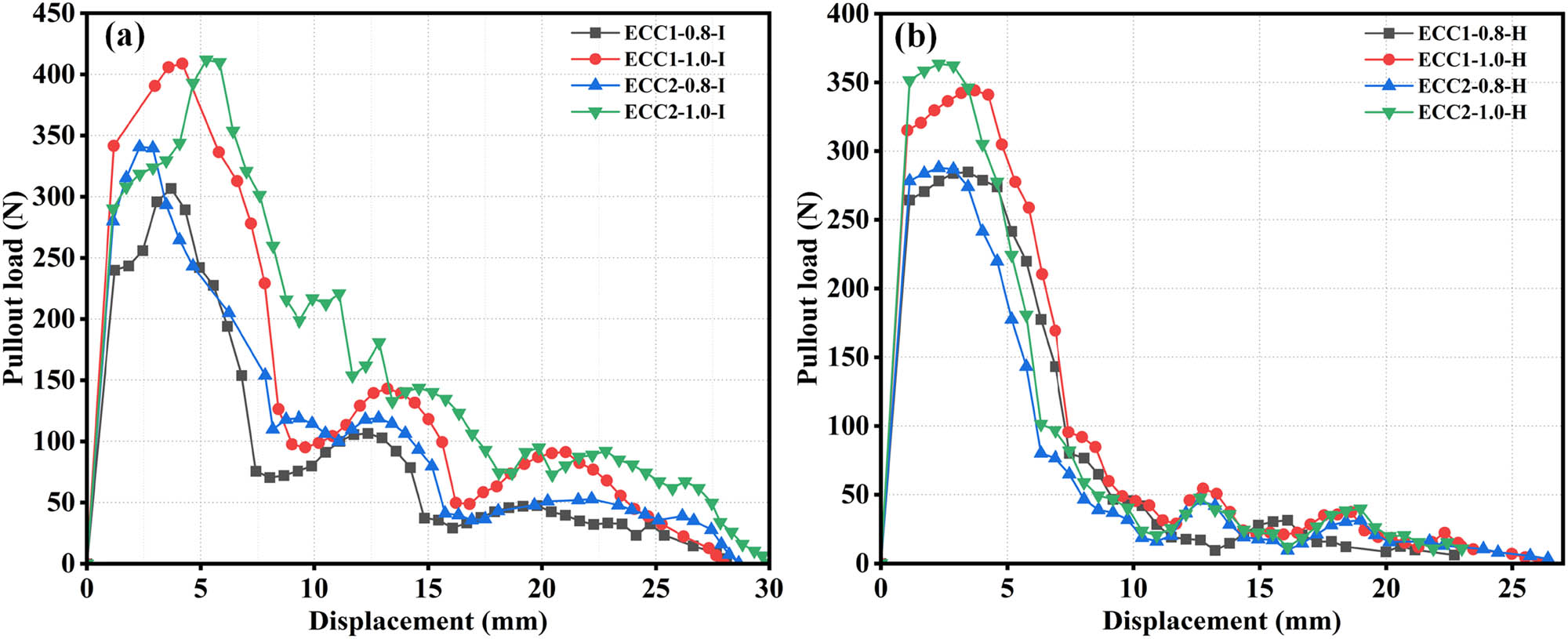

5.6 HS-SMAFs

Figure 12b demonstrates the influence of fiber shape and material properties on pullout behavior. HS-SMAFs consistently exhibit a substantially higher pullout load compared to LS-SMAFs across all displacement values and in both ECC mixtures (ECC1 and ECC2). This enhancement, which can exceed 50% and even double the pullout force, is attributed to the superior mechanical anchorage provided by the hooked geometry. The hooked ends of the fibers increase the frictional interaction during pullout and enhance mechanical interlocking with the ECC matrix, resulting in a stronger bond.

Monotonic axial tensile test: (a) IS-SMAFs and (b) HS-SMAFs.

Additionally, the data suggest that a larger fiber diameter of 1.0 mm and the use of the ECC2 mixture contribute to increased pullout loads. The wider diameter of 1.0 mm fibers provides a greater contact area, leading to a 10–20% increase in pullout load due to enhanced frictional forces and improved interlocking capabilities. Moreover, the ECC2 mixture appears to offer a more effective bonding environment, resulting in a 5–15% increase in pullout load compared to the ECC1 mixture. These findings underscore the significance of fiber shape and material properties in optimizing the pullout performance in ECC applications [65].

5.7 IS-SMAFs

Figure 12a illustrates that the IS-SMAFs consistently exhibit a higher pullout load across the entire displacement range, regardless of the ECC mixtures (ECC1 and ECC2). This is in contrast to LS-SMAFs and HS-SMAFs, with improvements ranging from 25 to 45%. The superior performance of IS-SMAFs can be attributed to the increased contact area between the indented fibers and the ECC matrix, which enhanced the frictional interaction and mechanical interlocking. Furthermore, Figure 12a shows that fibers with a larger diameter of 1.0 mm, along with the ECC2 mixture, also contribute to a significant increase in pullout load, ranging from 12 to 22%. This improvement is comparable to that observed with linear and hook-shaped fibers and results from the expanded contact area, which enhances the frictional force and bonding. Overall, these findings underscore the importance of fiber shape and diameter in optimizing the pullout performance in ECC systems.

5.8 Cyclic pullout behavior of SMAFs

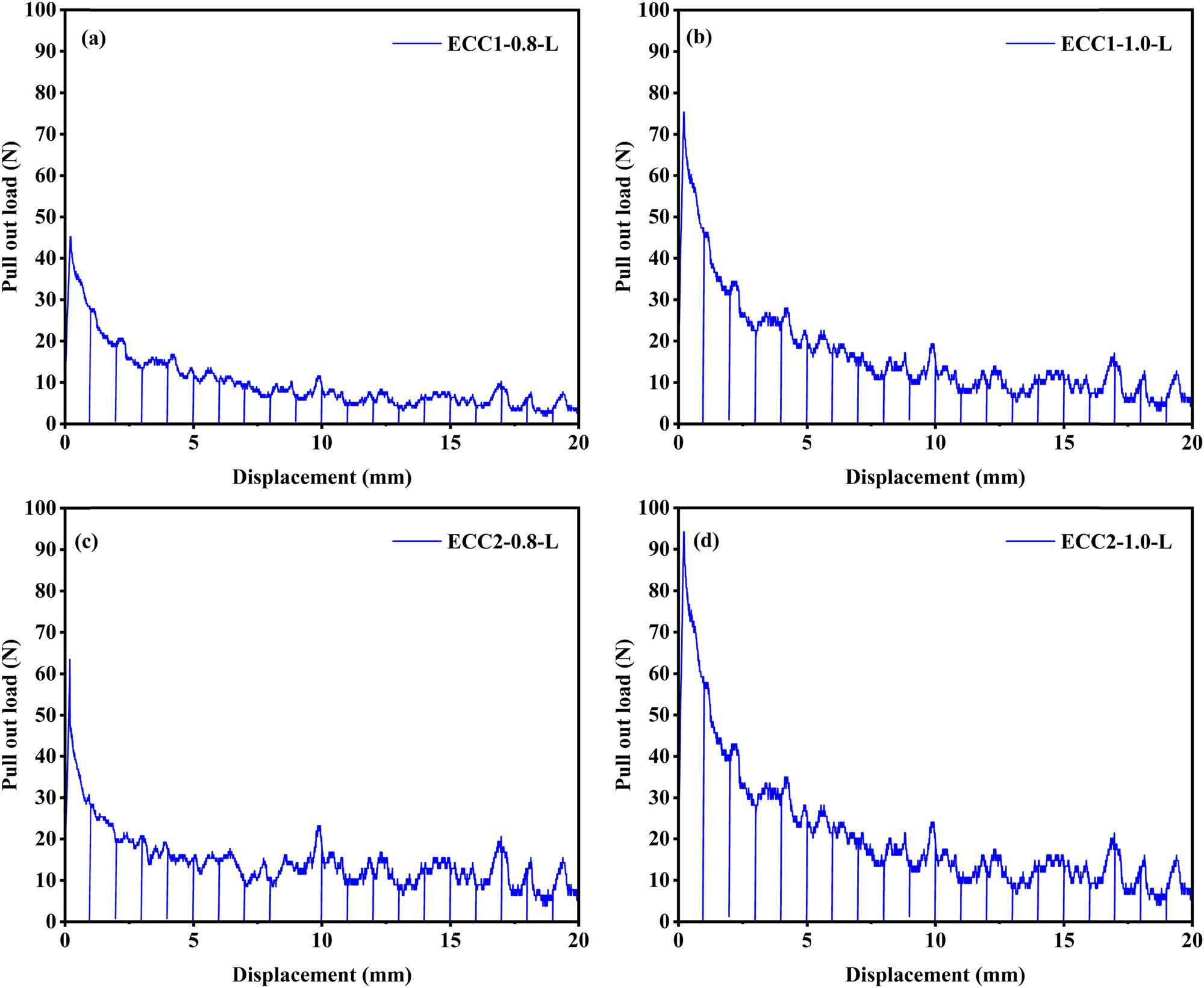

5.8.1 LS-SMAFs

To investigate the use of short superelastic SMAFs in self-centering structural elements, cyclic pullout tests were conducted [39]. These tests revealed that the peak pullout loads observed in both cyclic and monotonic tests were similar. For straight fibers (L-SMAFs) embedded in both ECC1 and ECC2 matrixes, the pullout load–displacement responses displayed nearly linear loading and unloading paths, indicating elastic behavior without any martensitic transformation, as shown in Figure 13. At a low cycle number, the ECC2-1.0-L graph might show a relatively high tensile strength value of 93 N. This represents the initial strength of LS-SMAFs before any cyclic loading. As the number of cycles increases, the graph might indicate a gradual decrease in tensile strength. This decline suggests that the fibers weaken with repeated pulling forces.

Cyclic pullout test of linear shape fibers in the ECC matrix, showing (a) ECC1-0.8-L, (b) ECC1-1-L, (c) ECC2-0.8-L, and (d) ECC2-1.0-L.

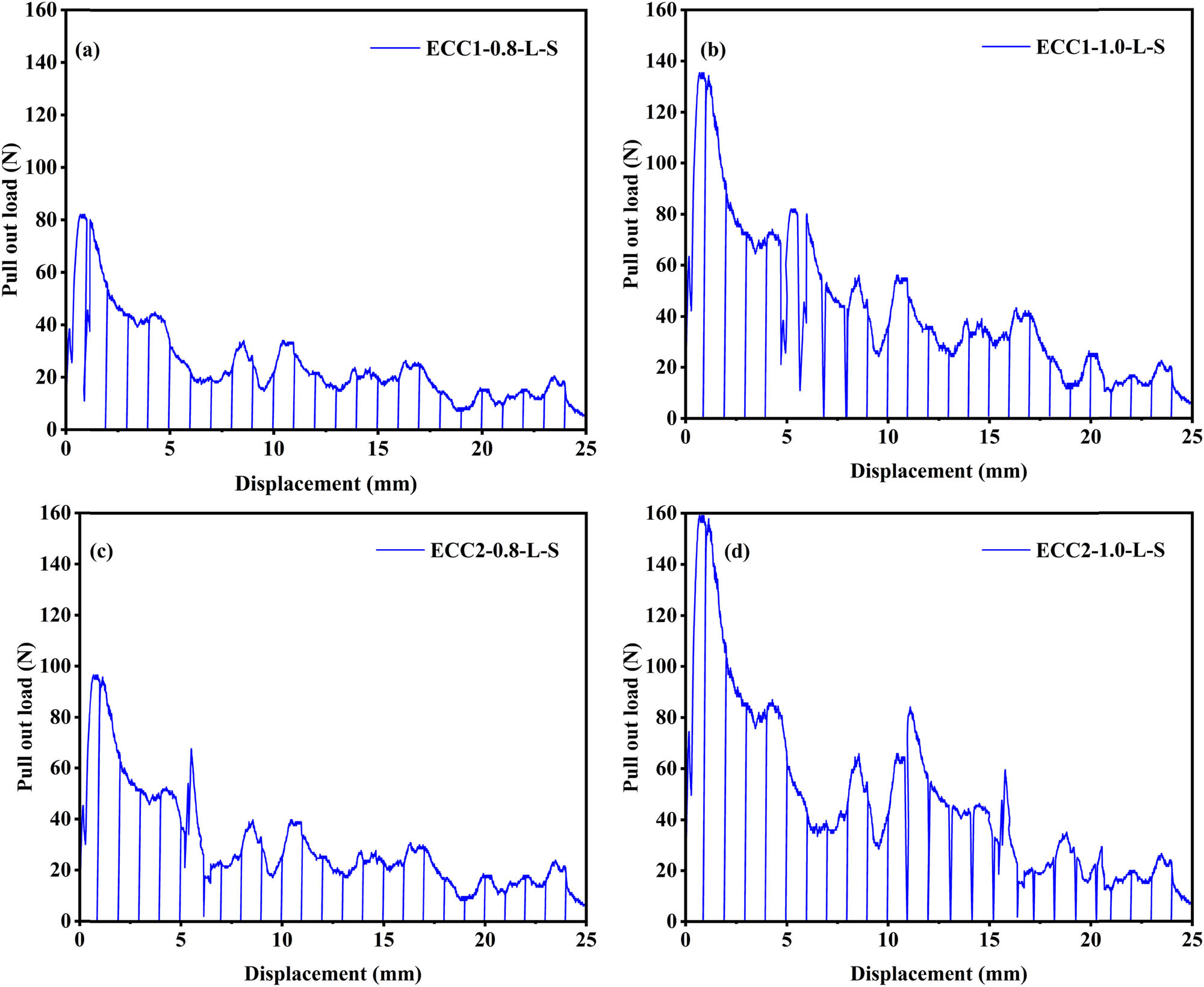

5.8.2 LS-SMAFs-S

The cyclic pullout tests in Figure 14a–d show that sandpaper-treated LS-SMAFs demonstrated limited recovery following the initial unloading cycle. This observation indicates primarily one-way deformation behavior, as the stresses applied were insufficient to activate the SME. Despite this, treated fibers exhibited higher pullout forces, ranging from 94.19 to 146.76 N, compared to untreated fibers, which reached a maximum of 85.61 N. This improvement in pullout resistance is attributed to the sandpaper polishing treatment, which likely enhanced the mechanical bond between the fibers and the ECC matrix. The test results suggest that both treated and untreated fiber types remained within the elastic deformation range throughout the testing, with no significant phase transformation occurring during the tests.

Cyclic pullout test of linear-shaped, sandpaper-treated fibers, showing (a) ECC1-0.8-L-S, (b) ECC1-1-L-S, (c) ECC2-0.8-L-S, and (d) ECC2-1.0-L-S.

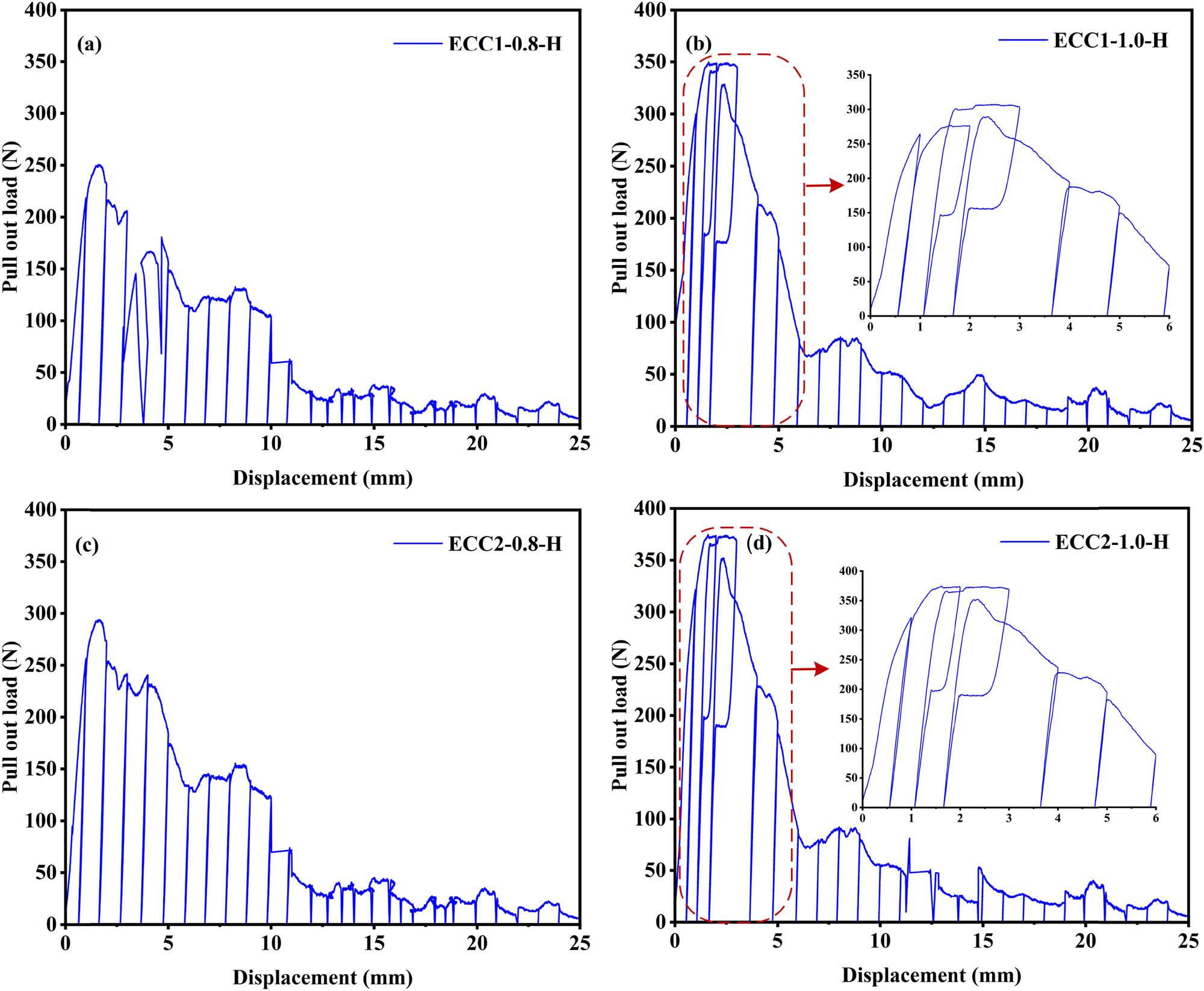

5.8.3 HS-SMAFs

In contrast to straight fibers (LS-SMAFs), HS-SMAFs exhibited a notable “flag-shaped” response during unloading and reloading cycles, as shown in Figure 15b and d. The HS-SMAFs demonstrated a significant recovery of slip and deformation, ranging from 3.71 to 4.11 mm, surpassing the performance of straight fibers. This enhanced behavior is attributed to two primary factors: first, the stresses encountered by the hook-shaped fibers during the initial unloading phase exceeded a critical threshold, which likely activated the shape-memory transformation. The localized stress concentration points created by the hook-shaped geometry facilitate this transformation. Second, the hook and indent shapes of the fibers contribute to their superelastic response, which is less pronounced in straight fibers due to the absence of such stress concentration features. This disparity highlights the superior pullout performance and recovery potential of HS-SMAFs in ECC applications.

Cyclic pullout test of hook-shaped fibers in the ECC matrix, showing (a) ECC1-0.8-H, (b) ECC1-1-H, (c) ECC2-0.8-H, and (d) ECC2-1.0-H.

As expected, the larger diameter fibers (ECC2) exhibited slightly higher pullout resistance even with the lower PVA contents of 287.79 and 284.48 N. More importantly, the increased PVA volume of 2.0% significantly boosted the pullout resistance for both diameters, around a 21% increase for ECC1 and a 26% increase for ECC2. This improvement is likely due to the enhanced bonding strength, coverage, and penetration provided by the higher adhesive volume.

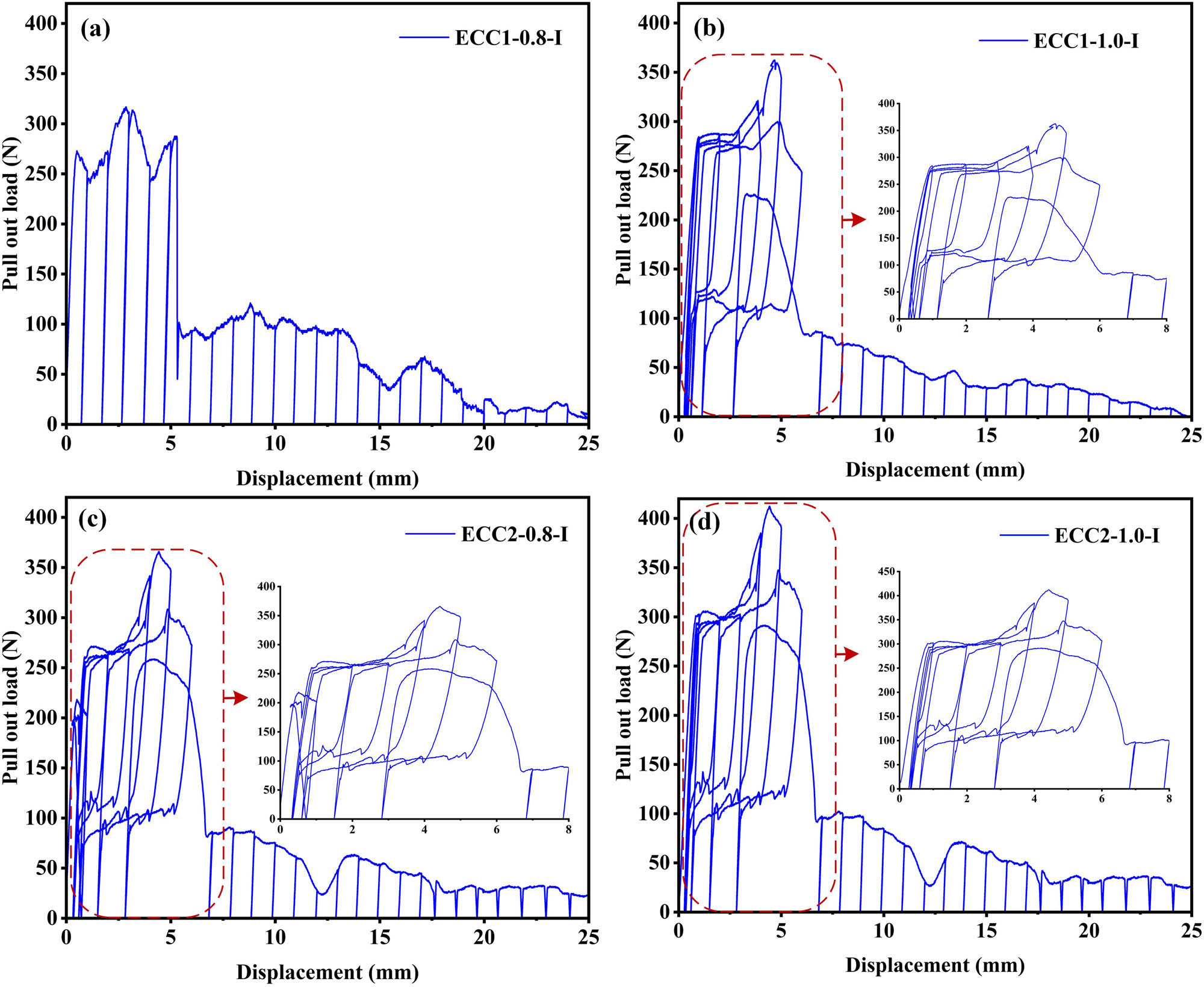

5.8.4 IS-SMAFs

Similar to the HS-SMAFs discussed earlier, IS-SMAFs also experience a slip in both matrixes more than 5 mm, with average pullout resistances ranging from 263.12 to 403.79 N, as shown in Figure 16, with their pullout resistance varying depending on the fiber diameter and PVA content. Larger diameter fibers of 1.0 mm generally have a higher pullout force due to their increased contact area of the adhesive.

Cyclic pullout test of indented-shaped fibers in the ECC matrix, showing (a) ECC1-0.8-I, (b) ECC1-1-I, (c) ECC2-0.8-I, and (d) ECC2-1.0-I.

The indented shape of IS-SMAFs significantly influences their pullout performance and recovery characteristics. The pronounced “flag-shaped” response observed during unloading and reloading cycles can be attributed to the indented design serving as an effective anchorage point. This shape facilitates concentrated stress transfer and enhances mechanical interlocking with the surrounding ECC matrix, leading to superior pullout resistance and deformation recovery.

In comparison, HS-SMAFs, with their hooked configuration, exhibit a less pronounced flag-shaped response due to fewer concentrated stress points. The simpler geometry of hooked fibers results in reduced stress concentration and, consequently, less effective shape recovery. Furthermore, the PVA content in the ECC matrix affects the fiber–matrix bond strength. A lower PVA content of 1.5% may not adequately saturate the matrix, weakening the fiber–matrix interface and reducing the pullout resistance. In contrast, IS-SMAFs benefit from their indented shape, which enhances the anchorage and improves the load transfer efficiency. These findings emphasize the importance of fiber geometry in optimizing the mechanical performance and recovery behavior of SMAFs in ECC systems [66].

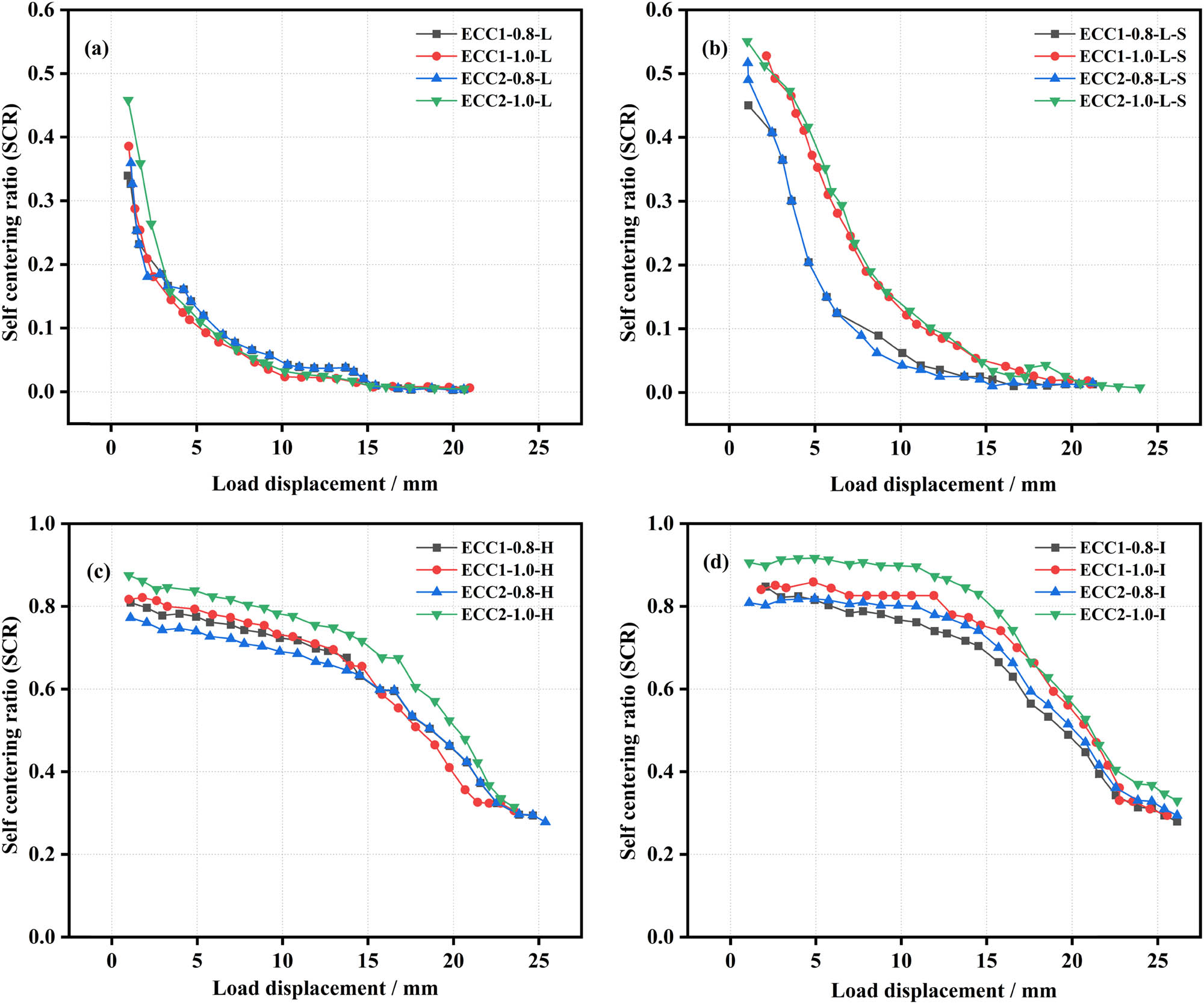

6 Self-centering

The effectiveness of SMAFs in re-centering within the ECC matrix was evaluated through the self-centering ratio (SCR). Equation (5) provides a means to compute the SCR, denoted as

In each cycle,

Figure 17a presents the SCRs of LS-SMAFs within ECC mixes. The data reveal that LS-SMAFs exhibit consistently low SCRs across all configurations. The highest SCR observed for untreated linear specimens (ECC2-1.0-L) is only 0.40, and it decreases further with increasing loading and bond failure. This indicates that linear fibers lack the necessary anchorage mechanisms to effectively induce self-centering within the ECC matrix [67]. While Figure 17b shows that LS-SMAFs-S provide some improvement in the self-centering performance over untreated fibers. The highest observed SCR for treated fibers is 0.55 for ECC2-1.0-L-S. Despite this improvement, the SCR remains relatively low, suggesting that the linear fiber geometry and its bonding with the matrix are insufficient for substantial shape recovery.

SCR of the ECC with SMAF: (a) LS-SMAF, (b) LS-SMAF-S, (c) HS-SMAF, and (d) IS-SMAF.

Figure 17c and d reveals a significant improvement in self-centering behavior for specimens incorporating HS-SMAFs and IS-SMAFs. Compared to the maximum SCR of 0.55 observed for linear fibers in Figure 17a, hooked specimens (ECC2-1.0-H) achieve a substantially higher ratio of 0.87. Similarly, indented specimens (ECC2-1.0-I) exhibit exceptional self-centering, reaching a peak SCR of 0.90, particularly between 10 and 12 mm displacement. This improved performance is attributed to the geometric advantages of the hooked and indented fibers, which provide superior mechanical interlocking with the ECC matrix. These shapes facilitate better stress transfer and enhance the shape recovery forces exerted by the fibers during unloading, making them more effective in self-centering applications.

However, it is important to note that the self-centering ability of both HS-SMAFs and IS-MAFs decreases after 12 mm displacement. This could be due to the fibers reaching a martensitic hardening stage. In this state, the SMAFs stiffen and are less effective in producing the shape recovery forces required for self-centering. Further research into the effects of fiber geometry and deformation levels on martensitic transformation behavior is needed. The results clearly show that the fiber diameter and mix composition influence the self-centering behavior. It was observed that specimens with larger diameter fibers exhibited a significantly higher SCR of 0.90 for ECC2-1.0-I, in comparison to specimens with smaller diameters, which achieved an SCR of 0.85 for ECC2-0.8-I. The observation suggests that there is a direct relationship between the diameter of fibers and their ability to anchor. Larger fibers have better mechanical interaction with the ECC matrix and help to align themselves. The components comprising the mixture also hold importance. The ECC2-1.0-I mix exhibited an SCR of 0.90, surpassing the SCR of the ECC1-1.0-I mix, which was 0.84. This can be attributed to the higher PVA concentration in ECC2. PVA improves the toughness, ductility, and fiber–matrix bonding of the composite. This, in turn, leads to a more effective energy dissipation mechanism and improved shape recovery capabilities during unloading, resulting in superior self-centering performance [68].

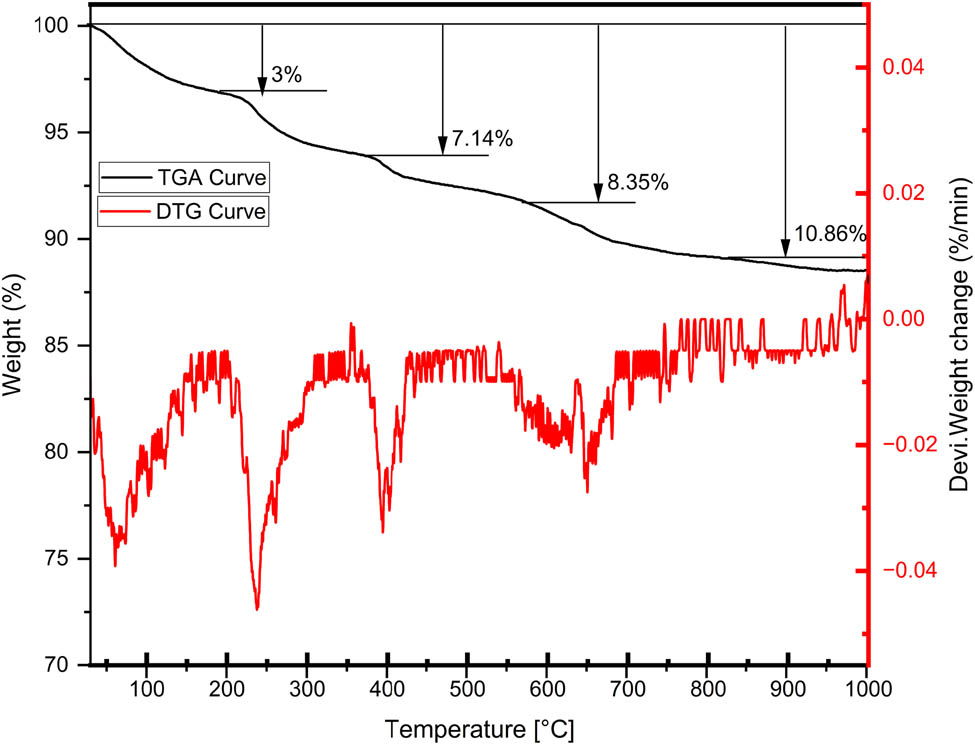

7 Thermogravimetry analysis (TGA)

TGA demonstrates multiple phases of weight reduction in the ECC specimen. Water evaporation, encompassing both surface moisture and chemically bound water within the material, is the main cause below 200°C. Between 200 and 600°C, a sharp drop in the DTG curve shown in Figure 18 signifies the loss of chemically bound water and the decomposition of hydrates like calcium hydroxide and calcium silicate hydrate. This coincides with the thermal decomposition of PVA fibers, further contributing to mass loss. As the temperature exceeds 600°C, significant microcracking occurs within the ECC. This development substantially enlarges the exposed surface area of the material, accelerating the decomposition of residual hydrates and the release of volatile components. The observed weight loss at higher temperatures, notably over 10.86% at 800°C, reflects the cumulative impact of these factors.

TGA and DTG curves of SMA-PVA-ECC.

The microcracking initiates increased surface area exposure, which facilitates the rapid breakdown of hydration products. As these hydrates decompose, they release water vapor, contributing to the initial mass loss. Concurrently, the degradation of PVA fibers within the ECC matrix also contributes to total weight loss. PVA fibers, which play a crucial role in the composite’s mechanical properties, degrade significantly at elevated temperatures, further increasing the overall mass loss.

The pronounced mass loss at 800°C results from the combined effects of water evaporation, breakdown of hydration products, PVA fiber degradation, and intensified decomposition driven by the formation of microcracks. Each of these processes interacts with the others, leading to a complex thermal response. The detailed understanding of these interactions is critical for optimizing the ECC performance under high-temperature conditions and enhancing the material’s resilience in fire-prone applications.

8 Microstructure analysis

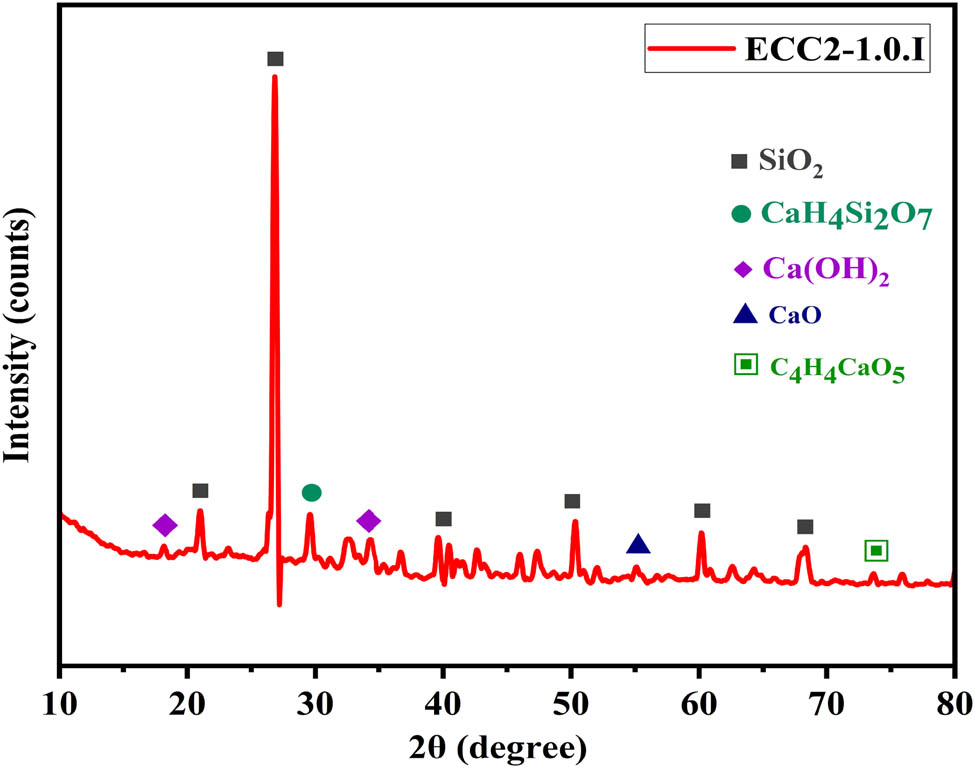

8.1 XRD analysis

As shown in Figure 19, sharp peaks around 28° and 48° indicate crystalline silicon dioxide (SiO2), likely originating from the quartz sand used in the ECC. Another peak around 34° suggests calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2), a common product of cement hydration. While not explicitly shown, calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H), another prevalent hydration product, likely contributes to the overall pattern. Due to their amorphous nature, PVA fibers themselves may not be directly detectable through XRD. The intensity of the peaks offers some insight into the material’s composition. The strong presence of SiO2 peaks suggests it as a major component. However, the presence of multiple peaks signifies a composite material with various crystalline phases. Interpreting solely from XRD data has limitations, as overlapping peaks can make definitive identification of all phases challenging.

XRD pattern of PVA-ECC.

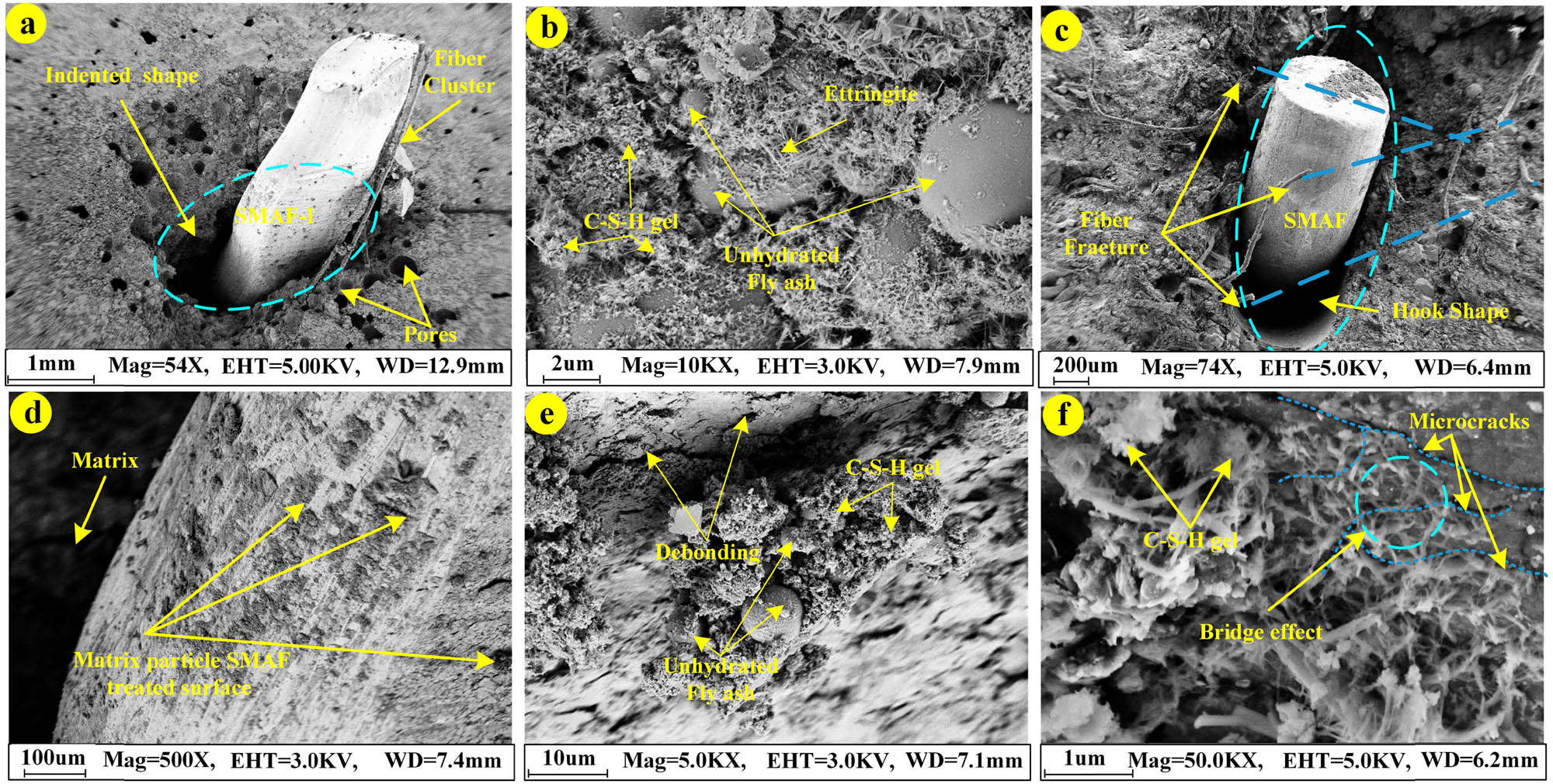

8.2 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

SEM analysis provides insights into the critical features governing the fiber–matrix interface in ECC composites. For IS-SMAFs, the analysis in Figure 20a reveals a pronounced mechanical interlock between the fiber geometry and the surrounding matrix. This interlocking significantly enhances the pullout resistance. Figure 20b highlights the presence of ettringite, C–S–H gel, and dehydrated fly ash within the ECC matrix. These observations indicate ongoing hydration processes, potential utilization of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), and pozzolanic reactions within the composite. The formation of these mineral phases contributes to a robust and stable microstructure, which is essential for optimal mechanical performance of the ECC. HS-SMAFs benefit from their inherent geometry, as illustrated in Figure 20c. The hook shape facilitates efficient anchoring and embedding within the matrix, leading to superior pullout resistance compared to other fiber shapes. This geometry acts as a mechanical barrier against fiber extraction, ensuring a secure fiber–matrix connection. The significance of fiber-to-fiber interactions is further highlighted by the occurrence of fiber cluster fracture.

SEM analysis of ECC after the pullout test, showing different fiber configurations: (a) ECC2-1-I, (b) ECC1-0.8-L, (c) ECC2-1-H, (d) ECC2-1-L-S, (e) ECC1-0.8-H, and (f) ECC2-0.8-I.

The efficacy of surface treatment to improve the bonding between fibers and matrices is further evidenced by the observation of matrix particles that are attached to the fibers treated with abrasive paper as shown in Figure 20d. The application of surface treatment results in the formation of pores on the surface of the fiber. These pores are expected to serve as supplementary anchoring sites, thereby enhancing the bonding through surface structure modification and an expansion of the contact area between the fiber and the matrix. In contrast, Figure 20e shows the difficulties faced in attaining consistent adhesion between the matrix and untreated shape-memory alloy (SMA) fibers. The visual representation provides evidence of separation and the presence of a loosely dispersed C–S–H gel surrounding the fiber. Various factors can be attributed to the observed phenomenon, including inconsistent surface treatment, inadequate initial bonding, and localized stress concentrations that arise during the loading process. These highlight the significance of optimizing surface preparation techniques to achieve dependable and strong adhesion at the interface between the fiber and matrix. The intermolecular adhesion plays a crucial role in promoting efficient stress reduction and improving the overall functionality of the composite material. Figure 20f shows the outcomes of the pullout test performed on PVA and treated SMAFs. The existence of microcracks within the matrix gives rise to apprehensions regarding the possibility of localized stress concentrations and subsequent degradation of the matrix. However, the image also unveils a favorable occurrence referred to as fiber bridging. The spanning and bridging of microcracks by SMAFs are evident, indicating their capacity to impede crack propagation and improve the overall ductility of the composite material. This observation underscores the beneficial impact of SMAFs in reducing failures caused by cracks and enhancing the durability of the material.

9 Summary of monotonic and cyclic tests

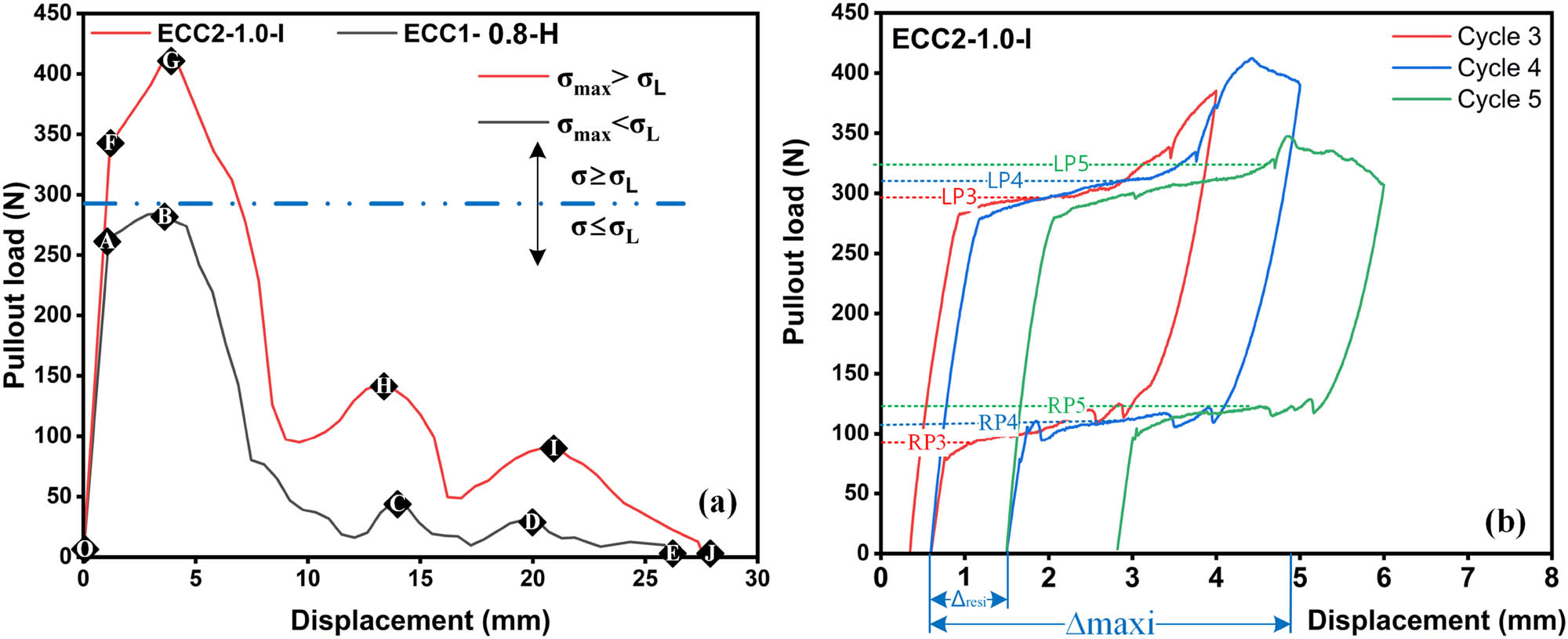

The pullout behavior exhibited by superelastic SMAF was analyzed under various loading conditions. Key points within the graph are labeled for reference. In scenarios where the internal stress within the fiber remains insufficient to reach the loading stress plateau, shown as a black line in Figure 21a, the pullout response can be characterized by five distinct stages. The initial stages A to B demonstrate a linear load increase due to the adhesive resistance between the fiber and the matrix. This is followed by a non-linear rise in load from B to C, attributed to the engagement of mechanical anchorage mechanisms. Upon reaching the peak load at point C, the hooked geometry of the HS-SMAF straightens, resulting in a gradual decrease in force from C to D. Finally, frictional forces govern the load behavior from point D until complete fiber pullout occurs at point E. Notably, unloading at any point during this pre-plateau regime E follows a near-vertical path as the SMAF does not undergo stress transformation.

Pullout load versus displacement curves for (a) monotonic and (b) cyclic tests.

However, when the mechanical anchorage is sufficiently robust to surpass the loading plateau stress, shown as a red line in Figure 21a, the pullout response exhibits different sets of stages. The initial load rise mirrors the pre-plateau behavior from A to F. However, a steeper load increase is observed from point F to G, signifying the initiation of the martensitic transformation within the SMAF. This transformation plateaus from point G to H until the load reaches its peak at point I. During unloading from stress exceeding the transformation point H, the SMAF undergoes a reverse transformation, resulting in a non-linear path with significant re-centering effect.

Figure 21b showcases consecutive loading cycles for a specimen subjected to loads exceeding the transformation stress. Each cycle exhibits a plateau region and strain-hardening behavior, but the peak loads and release plateaus represented by points like RP3 exhibit a progressive decrease. This reduction can be attributed to localized slip-induced transformations within the fiber, highlighting a potential limitation of the superelastic behavior under cyclic loading. In conclusion, this investigation underscores the critical role of strong mechanical anchorage in enabling the desired stress transformation and re-centering behavior in IH-SMAFs. While the observed performance surpasses previous findings, the reduction in pullout loads during cyclic loading warrants further research for potential improvements.

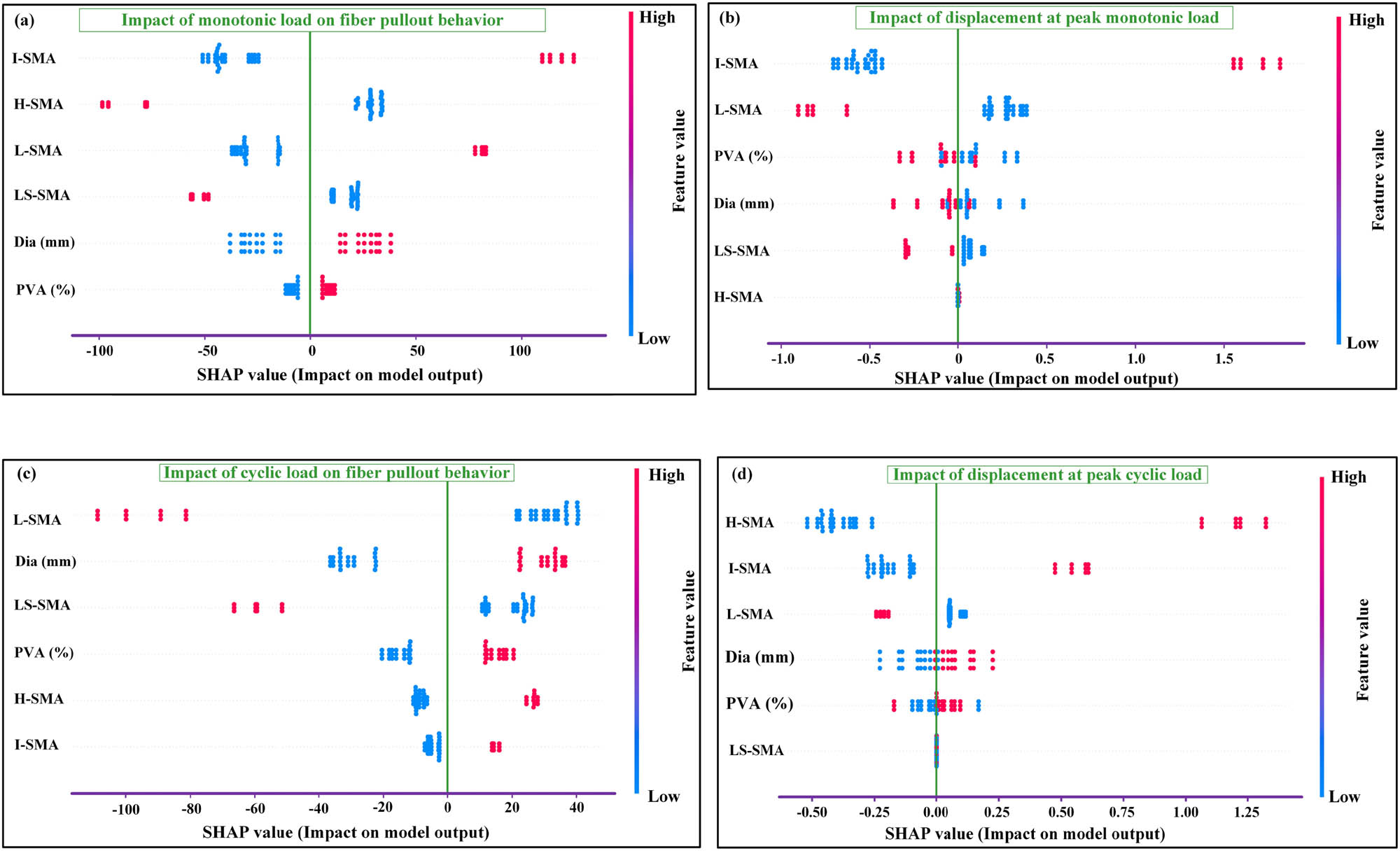

10 Sensitivity analysis

Shapley Additive Explanation (SHAP) values originate from cooperative game theory, designed to fairly distribute value among contributors. SHAP analysis helps to understand the contribution of each feature to the overall model performance [69]. As shown in Figure 22(a), for monotonic pullout load, the indented shape of the fiber has the highest positive impact, followed by a hooked shape. Conversely, both the LS-SMAF and LS-SMAF-S negatively impact the monotonic pullout test. In Figure 22(b), the impact of displacement at peak monotonic load is illustrated. Similar to monotonic load, the IS-SMAF has the highest positive impact, while the LS-SMAF shows the most significant negative impact. PVA fibers, diameter, and the LS-SMAF-S also negatively affect the displacement. Figure 22(c) shows that the linear fiber has the highest negative impact on the cyclic pullout test, while the diameter, PVA, and hooked and indented shaped fibers exhibit strongly positive impacts. The SHAP analysis of displacement at peak cyclic load reveals that the HS-SMAF and IS-SMAF have the highest positive impacts, with the diameter showing a significantly positive and a lesser negative impact, as shown in Figure 22(d).

Shape sensitivity analysis of SMAFs in ECC: (a) monotonic load on fiber pullout behavior, (b) displacement at peak monotonic load, (c) cyclic pullout behavior analysis, and (d) displacement at peak cyclic load.

11 Conclusions

This study experimentally demonstrated the pullout behavior of SMAF in ECC before and after surface treatment application. Three types of fibers were studied in ECC, including linear shaped (LS-SMAF), indented hook shaped (IHS-SMAF), and indented shaped (IS-SMAF) with diameters of 0.8 and 1.0 mm. Based on experimental results, the main findings of this study are concluded as follows:

The IS-SMAF and HS-SMAF exhibited 60–80% greater pullout resistance compared to the LS-SMAF, due to enhanced mechanical interlocking. Surface treatment (LS-SMAF-S) improved the LS-SMAF performance by 30–50%. Larger fiber diameters and higher PVA content further increased the pullout resistance by 15%, indicating that IS-SMAFs or surface-treated SMAFs can significantly enhance the structural performance and load-bearing capacity of ECC.

Hooked and indented fibers provide superior self-centering and stress transfer capabilities, with a 20% increase in SCR when using larger diameters and higher PVA content. This makes them ideal for applications requiring self-healing and enhanced recovery under load, such as in seismic-resistant structures.

SEM analysis revealed effective mechanical interlocking between indented and hooked fibers and the concrete matrix. XRD confirmed ongoing hydration processes, resulting in a robust microstructure. These findings suggest that optimizing the fiber–matrix interaction can improve the ECC performance under demanding conditions.

TGA identified stages of weight loss associated with water evaporation, decomposition of hydration products, and breakdown of PVA fibers at elevated temperatures. Understanding these thermal characteristics is crucial for applications involving high-temperature exposure.

12 Limitations, simplifications, and assumptions

This study, while providing valuable insights into the mechanical performance of ECCs reinforced with superelastic SMAFs operates within certain limitations and assumptions. First, the experimental conditions were controlled, and real-world factors such as environmental exposure, long-term durability, and varying loading conditions were not fully replicated. The study assumes uniform fiber distribution and consistent fiber–matrix bonding across samples, which may not be the case in larger-scale applications. The pullout and tensile tests were conducted under idealized conditions, and simplifications in the fiber treatment and embedding process may overlook potential variances in fiber orientation and distribution. Additionally, while the study includes a range of fiber geometries and surface treatments, it does not account for potential interactions between SMAFs and other composite constituents beyond the scope of this research. Future research should address these variables to better understand the behavior of SMAF-reinforced ECCs in the practical civil engineering field.

13 Future research directions

This study highlights the potential of SMAFs in enhancing the structural performance of ECC. Future research could focus on optimizing SMAF configurations and surface treatments to improve tensile and pullout capacities. Evaluating the long-term durability and structural integrity of SMAF-ECC composites under various environmental conditions is crucial for their application in construction. Additionally, conducting life cycle assessments and economic analyses of large-scale SMAF production could facilitate industry implementation. Integrating SMAFs with emerging construction technologies, such as 3D printing or self-healing materials, offers promising opportunities for innovation. Continued research in these areas will advance our understanding of SMAF-ECC systems and contribute to sustainable construction practices.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number TU-DSPP-2024-33.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, Project No. TU-DSPP-2024-33.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript, consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. MU: conceptualization, methodology, visualization, validation, software, and contribution to manuscript drafting. HQ: methodology, supervision, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing – review and editing, conceptualization and study design, and offered valuable perspectives on the implications of the findings. HA: methodology, formal analysis, and writing – original draft preparation. MNAK: writing – review and editing and contribution to the literature review. AR: writing – review and contribution to the Discussion section. AM: writing – review and editing and contribution to the literature review. YS: writing – review and editing and contribution to the Discussion section. MFA: formal analysis, writing – review, and visualization.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The authors declare that the data employed and analyzed during the current study will be available from the corresponding author upon request, and we are committed to providing access to our data to ensure the transparency and reproducibility of our findings.

References

[1] Shah AA, Ribakov Y. Recent trends in steel fibered high-strength concrete. Mater Des. 2011;32:4122–51.10.1016/j.matdes.2011.03.030Search in Google Scholar

[2] Rabi M, Shamass R, Cashell KA. Structural performance of stainless steel reinforced concrete members: A review. Constr Build Mater. 2022;325:126673.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126673Search in Google Scholar

[3] Zhang S, Cao K, Wang C, Wang X, Wang J, Sun B. Effect of silica fume and waste marble powder on the mechanical and durability properties of cellular concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2020;241:117980.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117980Search in Google Scholar

[4] Shah I, Li J, Khan N, Almujibah HR, Rehman MM, Raza A, et al. Bond-Slip behavior of steel bar and recycled steel fibre-reinforced concrete. J Renew Mater. 2024;12(1):167–86.10.32604/jrm.2023.031503Search in Google Scholar

[5] Yuan C, Fu W, Raza A, Li H. Study on mechanical properties and mechanism of recycled brick powder UHPC. Buildings. 2022;12:1622.10.3390/buildings12101622Search in Google Scholar

[6] Banaay KMH, Cruz OGD, Muhi MM. Engineered cementitious composites as a high-performance fiber reinforced material: a review. Int J Geomate. 2023;24:101–10.10.21660/2023.106.s8681Search in Google Scholar

[7] Akeed MH, Qaidi S, Ahmed Hemn U, Faraj RH, Majeed SS, Mohammed AS, et al. Ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Part V: Mixture design, preparation, mixing, casting, and curing. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;17:e01363.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01363Search in Google Scholar

[8] Sharma R, Jang JG, Bansal PP. A comprehensive review on effects of mineral admixtures and fibers on engineering properties of ultra-high-performance concrete. J Build Eng. 2022;45:103314.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103314Search in Google Scholar

[9] Zhang Z, Yang F, Liu JC, Wang S. Eco-friendly high strength, high ductility engineered cementitious composites (ECC) with substitution of fly ash by rice husk ash. Cem Concr Res. 2020;137:106200.10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106200Search in Google Scholar

[10] Ji J, Zhang Z, Lin M, Li L, Jiang L, Ding Y, et al. Structural application of engineered cementitious composites (ECC): A state-of-the-art review. Constr Build Mater. 2023;406:133289.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133289Search in Google Scholar

[11] Yu K, Zhang YX. Introduction to the development and application of engineered cementitious composite (ECC). Advances in engineered cementitious composite: Materials, structures, and numerical modeling. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering; 2022.10.1016/B978-0-323-85149-7.00001-XSearch in Google Scholar

[12] Yang Z, Xiong Z, Liu Y. Study on the self-recovery performance of SMAF-ECC under cyclic tensile loading. Constr Build Mater. 2023;392:131895.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131895Search in Google Scholar

[13] Qian H, Li Z, Pei J, Kang L, Li H. Seismic performance of self-centering beam-column joints reinforced with superelastic shape memory alloy bars and engineering cementitious composites materials. Compos Struct. 2022;294:115782.10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115782Search in Google Scholar

[14] Chen W, Feng K, Wang Y, Lin Y, Qian H. Evaluation of self-healing performance of a smart composite material (SMA-ECC). Constr Build Mater. 2021;290:123216.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123216Search in Google Scholar

[15] Qian H, Umar M, Khan MNA, Shi Y, Manan A, Raza A, et al. A state-of-the-art review on shape memory alloys (SMA) in concrete: mechanical properties, self-healing capabilities, and hybrid composite fabrication. Mater Today Commun. 2024;40:109738.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.109738Search in Google Scholar

[16] Raza A, Junjie Z, Shiwen X, Umar M, Chengfang Y. Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand. Sci Eng Compos Mater. 2024;31(1):20240017.10.1515/secm-2024-0017Search in Google Scholar

[17] Chengfang Y, Raza A, Manan A, Ahmad S, Chao W, Umar M. Numerical and experimental study of Yellow River sand in engineered cementitious composite. Proc Inst Civ Eng-Eng Sustain. 2024. Elsevier.10.1680/jensu.23.00080Search in Google Scholar

[18] Golewski GL. Investigating the effect of using three pozzolans (including the nanoadditive) in combination on the formation and development of cracks in concretes using non-contact measurement method. Adv Nanobiomed Res. 2024;16(3):217.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Golewski GL. Enhancement fracture behavior of sustainable cementitious composites using synergy between fly ash (FA) and nanosilica (NS) in the assessment based on digital image processing procedure. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2024;131:104442.10.1016/j.tafmec.2024.104442Search in Google Scholar

[20] Golewski GL. Mechanical properties and brittleness of concrete made by combined fly ash, silica fume and nanosilica with ordinary Portland cement. AIMS Mater Sci. 2023;10:390–404.10.3934/matersci.2023021Search in Google Scholar

[21] Wang L, Zhang P, Golewski G, Guan J. Editorial: Fabrication and properties of concrete containing industrial waste. Front Magn Mater. 2023;10:3389.10.3389/fmats.2023.1169715Search in Google Scholar

[22] Gupta NK, Srivastava V, Somani N. Self-healing materials: fabrication technique and applications – a critical review. Int J Interact Des Manuf. 2023;18:6333–50.10.1007/s12008-023-01283-ySearch in Google Scholar

[23] Fang C, Chen J, Wang W. SMA-braced steel frames influenced by temperature: Practical modelling strategy and probabilistic performance assessment. J Build Eng. 2023;76:107334.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107334Search in Google Scholar

[24] Qian H, Wu B, Shi Y, Du Y, Wang X, Zhang J, et al. Cyclic tensile response and crack closure performance of novel superelastic Ni-Ti SMA cable grid-reinforced engineered cementitious composites. Constr Build Mater. 2024;445:137959.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137959Search in Google Scholar

[25] Mohri M, Ferretto I, Khodaverdi H, Leinenbach C, Ghafoori E. Influence of thermomechanical treatment on the shape memory effect and pseudoelasticity behavior of conventional and additive manufactured Fe–Mn–Si–Cr–Ni-(V,C) shape memory alloys. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;24:5922–33.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.04.195Search in Google Scholar

[26] Mohri M, Ferretto I, Leinenbach C, Kim D, Lignos DG, Ghafoori E. Effect of thermomechanical treatment and microstructure on pseudo-elastic behavior of Fe–Mn–Si–Cr–Ni-(V, C) shape memory alloy. Mater Sci Eng A. 2022;855:143917.10.1016/j.msea.2022.143917Search in Google Scholar

[27] Zhang Y, Chai X, Ju X, You Y, Zhang S, Zheng L, et al. Concentration of transformation-induced plasticity in pseudoelastic NiTi shape memory alloys: Insight from austenite-martensite interface instability. Int J Plast. 2023;160:103481.10.1016/j.ijplas.2022.103481Search in Google Scholar

[28] Gao N, Jeon JS, Hodgson DE, Desroches R. An innovative seismic bracing system based on a superelastic shape memory alloy ring. Smart Mater Struct. 2016;25:55030.10.1088/0964-1726/25/5/055030Search in Google Scholar

[29] Salehi M, Desroches R, Hodgson D, Parnell TK. Numerical evaluation of SMA-based multi-ring self-centering damping devices. Smart Mater Struct. 2021;30:105012.10.1088/1361-665X/ac1d94Search in Google Scholar

[30] Shi Y, Wang X, Qian H, Zhao H, Wu P, Kang L, et al. Development and preliminarily tests of superelastic Ni-Ti SMA ribbed bars for reinforced concrete applications. Constr Build Mater. 2023;402:133066.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133066Search in Google Scholar

[31] Qian H, Wu P, Ren Z, Chen G, Shi Y. Pseudo-static tests of reinforced concrete pier columns confined with pre-tensioned superelastic shape memory alloy wires. Eng Struct. 2023;280:115680.10.1016/j.engstruct.2023.115680Search in Google Scholar

[32] Qian H, Wang X, Li Z, Zhang Y. Experimental study on re-centering behavior and energy dissipation capacity of prefabricated concrete frame joints with shape memory alloy bars and engineered cementitious composites. Eng Struct. 2023;277:115394.10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.115394Search in Google Scholar

[33] Qian H, Ye J, Shi Y, Ye Y, Gao J, Deng E. Development and investigation of a novel precast beam-column friction hinge joint enhanced with Cu–Al–Mn SMA-plate-based self-centring buckling-restrained devices. J Build Eng. 2023;79:107825.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107825Search in Google Scholar

[34] Jing H, Shi Y, Ye J, Li H, Qian H, Umar M, et al. Mechanical property optimization of a superelastic Ni-Ti SMA cable for prefabricated structural applications. Structures. 2024;67:106943.10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106943Search in Google Scholar

[35] Choi E, Kim DJ, Hwang JH, Kim WJ. Prestressing effect of cold-drawn short NiTi SMA fibres in steel reinforced mortar beams. Smart Mater Struct. 2016;25:85041.10.1088/0964-1726/25/8/085041Search in Google Scholar

[36] Choi E, Kim D, Chung YS, Nam TH. Bond-slip characteristics of SMA reinforcing fibers obtained by pull-out tests. Mater Res Bull. 2014;58:28–31.10.1016/j.materresbull.2014.04.060Search in Google Scholar

[37] Dehghani A, Aslani F, Liu Y. Pullout behaviour of shape memory alloy fibres in self-compacting concrete and its relation to fibre surface microtopography in comparison to steel fibres. Constr Build Mater. 2022;323:126570.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126570Search in Google Scholar

[38] Choi E, Kim D, Lee JH, Ryu GS. Monotonic and hysteretic pullout behavior of superelastic SMA fibers with different anchorages. Compos Part B Eng. 2017;108:232–42.10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.09.080Search in Google Scholar

[39] Choi E, Mohammadzadeh B, Hwang JH, Kim WJ. Pullout behavior of superelastic SMA fibers with various end-shapes embedded in cement mortar. Constr Build Mater. 2018;167:605–16.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.02.070Search in Google Scholar

[40] Rabczuk T, Belytschko T. Cracking particles: A simplified meshfree method for arbitrary evolving cracks. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 2004;61:2316–43.10.1002/nme.1151Search in Google Scholar

[41] Rabczuk T, Belytschko T. A three-dimensional large deformation meshfree method for arbitrary evolving cracks. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2007;196:2777–99.10.1016/j.cma.2006.06.020Search in Google Scholar

[42] Talebi H, Silani M, Bordas SPA, Kerfriden P, Rabczuk T. A computational library for multiscale modeling of material failure. Comput Mech. 2014;53:1047–71.10.1007/s00466-013-0948-2Search in Google Scholar

[43] Choi E, Mohammadzadeh B, Hwang JH, Lee JH. Displacement-recovery-capacity of superelastic SMA fibers reinforced cementitious materials. Smart Struct Syst. 2019;24:157–71.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Choi E, Mohammadadeh B, Kim D, Jeon JS. A new experimental investigation into the effects of reinforcing mortar beams with superelastic SMA fibers on controlling and closing cracks. Compos Part B Eng. 2018;137:140–52.10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.11.017Search in Google Scholar

[45] Ho HV, Choi E, Park SJ. Investigating stress distribution of crimped SMA fibers during pullout behavior using experimental testing and a finite element model. Compos Struct. 2021;272:114254.10.1016/j.compstruct.2021.114254Search in Google Scholar

[46] Ali M, Nehdi M. Experimental investigation on mechanical properties of shape memory alloy fibre-reinforced ECC composite. Int Conf Civ Archit Eng. 2016;11:1–11.10.21608/iccae.2016.43423Search in Google Scholar

[47] Dehghani A, Aslani F. Effect of 3D, 4D, and 5D hooked-end type and loading rate on the pull-out performance of shape memory alloy fibres embedded in cementitious composites. Constr Build Mater. 2021;273:121742.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121742Search in Google Scholar

[48] Kim DJ, Kim HA, Chung YS, Choi E. Pullout resistance of deformed shape memory alloy fibers embedded in cement mortar. J Intell Mater Syst Struct. 2016;27:249–60.10.1177/1045389X14566524Search in Google Scholar

[49] Yang Z, Gong X, Wu Q, Fan L. Bonding mechanical properties between SMA fiber and ECC matrix under direct pullout loads. Materials (Basel). 2023;16(7):2672.10.3390/ma16072672Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Yang Z, Deng T, Fu Q. The effect of fiber end on the bonding mechanical properties between SMA fibers and ECC matrix. Buildings. 2023;13:2027.10.3390/buildings13082027Search in Google Scholar

[51] Yang Z, Du Y, Liang Y, Ke X. Mechanical behavior of shape memory alloy fibers embedded in engineered cementitious composite matrix under cyclic pullout loads. Materials (Basel). 2022;15:4531.10.3390/ma15134531Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Shi F, Zhou Y, Ozbulut OE, Cao S. Development and experimental validation of anchorage systems for shape memory alloy cables. Eng Struct. 2021;228:111611.10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.111611Search in Google Scholar

[53] Liang D, Liang D, Zheng Y, Fang C, Fang C, Fang C, et al. Shape memory alloy (SMA)-cable-controlled sliding bearings: Development, testing, and system behavior. Smart Mater Struct. 2020;29:85006.10.1088/1361-665X/ab8f68Search in Google Scholar

[54] Šittner P, Heller L, Pilch J, Curfs C, Alonso T, Favier D. Young’s modulus of austenite and martensite phases in superelastic NiTi wires. J Mater Eng Perform. 2014;23:2303–14.10.1007/s11665-014-0976-xSearch in Google Scholar

[55] GB175-2007. Common portland cement. Beijing: Standard Press of China; 2007.Search in Google Scholar

[56] International A. Standard specification for portland cement, ASTM-C150-2012. West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, USA: ASTM International; 2021. p. 1–5. 10(Reapproved).Search in Google Scholar

[57] Yuan C, Xu S, Raza A, Wang C, Wang D. Influence and mechanism of curing methods on mechanical properties of manufactured sand UHPC. Materials (Basel). 2022;15:6183.10.3390/ma15186183Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[58] Qi J, Wu Z, Ma ZJ, Wang J. Pullout behavior of straight and hooked-end steel fibers in UHPC matrix with various embedded angles. Constr Build Mater. 2018;191:764–74.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.10.067Search in Google Scholar

[59] Bhutta A, Farooq M, Borges PHR, Banthia N. Influence of fiber inclination angle on bond-slip behavior of different alkali-activated composites under dynamic and quasi-static loadings. Cem Concr Res. 2018;107:236–46.10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.02.026Search in Google Scholar

[60] Kim DJ, El-Tawil S, Naaman AE. Rate-dependent tensile behavior of high performance fiber reinforced cementitious composites. Mater Struct Constr. 2009;42:399–414.10.1617/s11527-008-9390-xSearch in Google Scholar

[61] Abdallah S, Fan M. Anchorage mechanisms of novel geometrical hooked-end steel fibres. Mater Struct Constr. 2017;50:139.10.1617/s11527-016-0991-5Search in Google Scholar

[62] Isla F, Ruano G, Luccioni B. Analysis of steel fibers pull-out. Experimental study. Constr Build Mater. 2015;100:183–93.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.09.034Search in Google Scholar

[63] Beglarigale A, Yazici H. Pull-out behavior of steel fiber embedded in flowable RPC and ordinary mortar. Constr Build Mater. 2015;75:255–65.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.11.037Search in Google Scholar

[64] Shi M, Zhao J, Liu J, Wang H, Wang Z, Xu L, et al. The interface adhesive properties and mechanical properties of shape memory alloy composites. Fibers Polym. 2022;23:273–81.10.1007/s12221-021-3292-8Search in Google Scholar

[65] Choi E, Joo Kim D, Jeon C, Gin S, New SMA. Short fibers for cement composites manufactured by cold drawing. J Mater Sci Res. 2016;5:74–87.10.5539/jmsr.v5n2p74Search in Google Scholar

[66] Nespoli A, Grande AM, Bennato N, Rigamonti D, Bettini P, Villa E, et al. Towards an understanding of the functional properties of NiTi produced by powder bed fusion. Prog Addit Manuf. 2021;6:321–37.10.1007/s40964-020-00155-1Search in Google Scholar

[67] Raza S, Shafei B, Saiid Saiidi M, Motavalli M, Shahverdi M. Shape memory alloy reinforcement for strengthening and self-centering of concrete structures – State of the art. Constr Build Mater. 2022;324:126628.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126628Search in Google Scholar

[68] Ali MAEM, Nehdi ML. Innovative crack-healing hybrid fiber reinforced engineered cementitious composite. Constr Build Mater. 2017;150:689–702.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.06.023Search in Google Scholar

[69] Manan A, Zhang P, Ahmad S, Ahmad J. Prediction of flexural strength in FRP bar reinforced concrete beams through a machine learning approach. Anti-Corros Methods Mater. 2024;71(5):562–79.10.1108/ACMM-12-2023-2935Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand