Abstract

We report here a convenient, rapid one-pot synthesis of new metal–metal core–shell nanocomposites comprising silver nanowires (AgNWs) coated with nickel. The resulting AgNWs and nickel-coated silver nanocables average 60–80 nm in diameter were prepared by the polyol synthetic route. This method employed ethylene glycol as a reducing agent and polyvinylpyrrolidone as a capping agent. These nanomaterials are designated as AgNWs (0.1 M) and Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and Ag@Ni (0.5 M) nanocables based on the nickel content and were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), X-ray diffraction (XRD), UV–Visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy, and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy. The morphology of each nanowire and nanocable was clarified using SEM, while EDX quantified the presence of Ni. XRD patterns confirmed the face-centered cubic structure of the nanomaterials. The Debye–Scherrer formula was applied to establish different characteristics such as crystallite size and lattice constant. Surface plasmon resonance was measured using UV−Vis spectroscopy and fluorescence of each product was determined by PL spectroscopy, respectively. Both the AgNWs and Ag@Ni nanocables catalyze the reduction of p-nitrophenol to p-aminophenol by sodium borohydride.

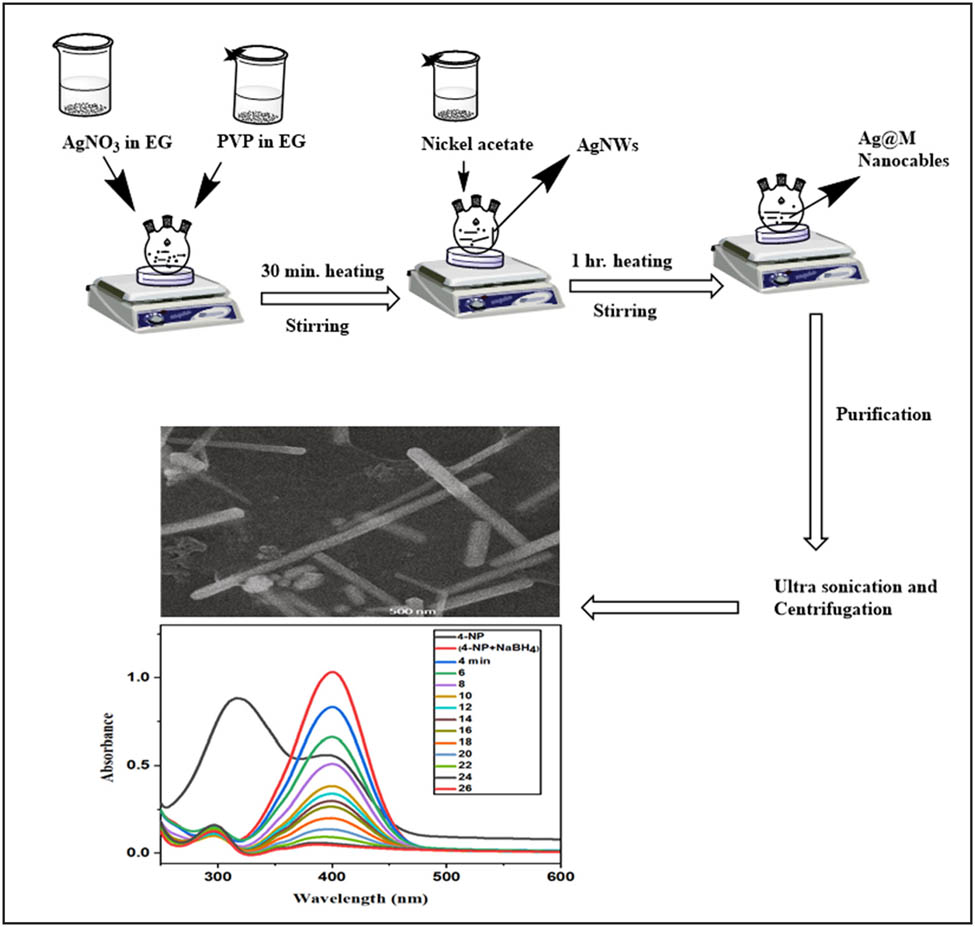

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

The synthesis of metal–metal nanocomposites with improved properties for various applications is important in material science and nanotechnology [1,2]. Heteronuclear core–shell metallic nanostructures have gained much importance because of their value in the fields of optics, medicine, catalysis, energy conversion, and storage [3–6]. In such materials, the core has major functional properties, and the surrounding shell protects and stabilizes the inner core. Since the properties of nanostructures greatly depend upon their shape, size, and composition, these structures exhibit significantly superior and enhanced characteristics relative to their single-component counterparts [7–9]. Metal-based nanoparticles (NPs) have intrigued scientists for more than a century and almost any metal can be converted into nanostructures such as copper (Cu), silver (Ag), aluminium (Al), gold (Au), cobalt (Co), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), and nickel (Ni) [10]. The capping agents of such nanocomposites facilitate the effective catalysis of stereoselective and stereospecific processes due to steric hindrances from specific crystal planes [11].

McKiernan et al. synthesized core/shell Ag@Ni nanowires via two-step solution-based method and studied their electric and magnetic properties. They observed a decrease in electric conductivity of Ag nanowires with a coating of nickel because of electron transfer from the silver core to the nickel. The Ag@Ni core/sheath nanocomposites show potential applications in areas such as medical, spintronics, displays and electronics [12–14]. Zhang et al. prepared an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution by coating AgNWs with nickel [15]. Recently, hydrothermal [16], laser ablation [17], galvanic replacement [18], and sonochemical [19] methods have been used to synthesize bimetallic core/shell nanostructures to improve coating quality. The microwave polyol method was used by Tsuji et al. for the synthesis of Ag@Ni core/shell NPs [20]. Superparamagnetic core/shell Ag@Ni NPs and Ag@Pd NPs were fabricated by using the one-pot synthetic method. The as-synthesized product was used as a catalyst for the hydrolysis of NaBH4 to generate hydrogen (H2) gas. In addition, better catalysts have been fabricated by coating metal oxide layers on metal cores. The resulting core/shell NPs exhibit enhanced catalytic performance compared to conventional supported catalysts [21,22]. We note that sodium borohydride can be problematical in the synthesis of bimetallic nanostructured catalysts because it can reduce some metal ions at room temperature during synthesis, and this frequently leads to irregular particle sizes.

Nickel catalyzes many reactions including oxidative coupling of inert chemicals and hydrogenation of vegetable oils [23,24]. Bimetallic Ag@Ni/C particles are effective cathodic catalysts in alkaline fuel cells due to their low working temperature and low corrosivity. In addition, nickel and nickel dispersion coatings are used in a multitude of applications where corrosion and wear resistance are challenges. Such dispersion films combine the ductility of the metal matrix with the hardness of incorporated non-metallic particles, such as alumina, titania, or silicon carbide [25]. Coatings of nickel, tin, and chromium are cathodic coatings as these are higher than steel in the galvanic series. These coatings provide a physical barrier between metal and the environment [26]. Also, nano-sized nickel catalysts are used for Stille coupling reactions in water. Nickel NPs, like those of other catalytic transition metals, benefit from large surface-to-volume ratios, which result in greater efficiency compared to bulk materials [27]. Nickel NPs can be used for the conversion of p-nitrophenol (p-NP) to p-aminophenol (p-AP) through catalytic hydrogenation. Despite these extensive catalytic applications of nickel, improvements are still needed in performance and catalyst cost [28]. The main objective of this work is to study the morphology of Ni sheath on the surface of nanostructure and investigate the catalytic and fluorescent properties of as synthesized material.

This study reports easily prepared Ag@Ni co-axial nanocable catalysts for the selective conversion of p-NP to p-AP by sodium borohydride which is more effective than many reported catalysts for this process [29]. This hybrid nanomaterial has been characterized by multiple physical techniques and its catalytic activity studied in detail.

2 Experimental

This section describes the material used in the study and the process used in the synthesis of nanocomposites.

2.1 Materials

Analytical grade reagents and chemicals were used in this work. Nickel acetate (Degussa) and silver nitrate AgNO3 99.0% (Analytical reagent) were used as precursors. Ethylene glycol (EG) (C2H6O2) 99% (Sigma Aldrich) was employed as solvent and reductant, and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, K-90 from Daejung Reagent Chemicals-Korea) was used as a capping agent. p-NP (UNI-CHEM), acetone (Ridel-de-Haen), sodium borohydride (NaBH4), and absolute ethanol (CH3CH2OH) from Merck were used as received.

2.2 Methods

This section presents a discussion of the specific steps used in the literature review and collection of data for the study.

2.2.1 Synthesis of AgNWs

AgNWs (0.1 M) were synthesized using the polyol method. In a typical synthesis, 10 mL of EG was pre-heated for 30 min at 160°C. Then, 60 µL aliquots of an EG solution of NaCl (0.0087 g in 5 mL) were added to 10 mL of pre-heated EG. To this resulting solution was added slowly and dropwise EG solutions of silver nitrate (5 mL, 0.085 g, 0.5 mmol) and PVP (5 mL, 0.055 g, 0.5 mmol). After these additions, the resulting solution was yellowish brown which turned grey after a few minutes. The temperature of the reaction mixture dropped to 140°C during the addition. It was then maintained for 1 h at 160°C, acetone was added, and the resulting mixture was centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min. The compacted solid product was suspended in ethanol and centrifuged, sequentially, several times to afford the gray-colored AgNWs.

2.2.2 Synthesis of Ag@Ni nanocables

The Ag@Ni nanostructures were synthesized by preheating 10 mL of EG at 160°C under continuous stirring for 1 h. The EG solutions of silver nitrate (AgNO3; 0.085 g, 0.5 mmol) and PVP (0.055 g, 0.5 mmol) were added dropwise to the preheated EG. The addition of the AgNO3 solution resulted in the formation of seeds, which was followed by the formation of NWs. The silver nanostructures with varying amounts of nickel coating were prepared using varying concentrations of nickel acetate (0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 M solutions in EG). Here, a 2 mL solution of 0.2 M (0.09 g) nickel acetate was added to the above reaction after 30 min. Each reaction was stirred for 1 h to ensure completion. For the synthesis of Ag@Ni (0.3 M), Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and Ag@Ni (0.5 M), a similar method was applied. Finally, the reaction was cooled to room temperature, washed with ethanol, and centrifuged at 6,000 rpm to remove any small particles and un-passivated PVP. Each sample was dispersed in ethanol and designated as Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and Ag@Ni (0.5 M).

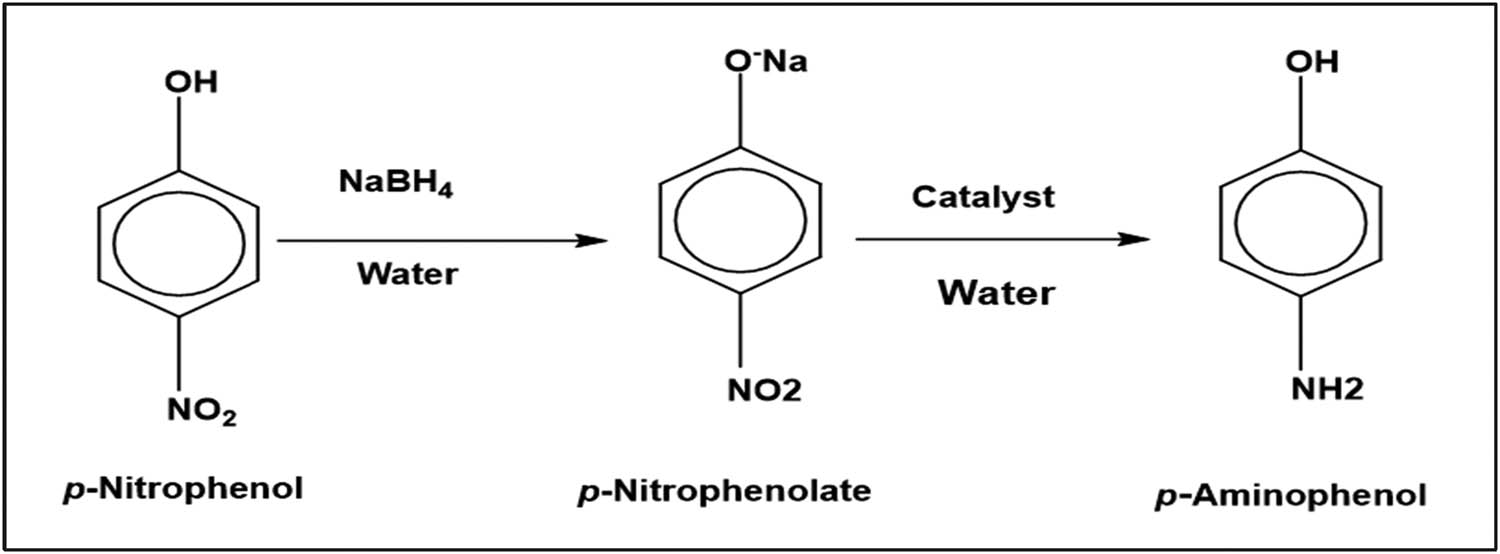

2.3 Catalytic properties of AgNWs and Ag@Ni nanocables

The catalytic reduction of p-NP to p-AP by NaBH4 was studied in the presence of the nickel nanocatalyst in aqueous media. For this purpose, p-NP (0.0069 g, 0.05 mmol) and NaBH4 (0.007 g, 0.2 mmol) were prepared, separately, in 5.0 mL of distilled water. A molar 1:4 ratio of substrate:reagent was used. The catalyst, AgNWs (0.1 M), was added to the solution of p-NP, and the resulting mixture was sonicated for 30 min at room temperature. The reaction was started by the addition of the aqueous NaBH4 solution as shown in Scheme 1. The catalytic conversion was followed by the consumption of p-NP monitored at 400 nm. The same procedure was used to study the catalytic behavior of Ni-coated AgNWs using 0.025 g of AgNWs (0.1 M), Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), and Ag@Ni (0.4 M).

Reaction scheme for the reduction of p-NP to p-AP.

2.4 Characterization of Ag@Ni nanocables

The following methods were used to establish the structure and morphology of the as-prepared samples. A TESCAN MIRA3 XMU scanning electron microscope coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) provided both morphologies and elemental compositions, while X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Bruker D-8 discoverer X-ray diffractometer) gave the structural information. UV–Visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy (SHIMADZU UV 1800 Spectrophotometer) and photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy (SHIMADZU RF-6000 Spectro Fluorometer) were used to quantify surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and fluorescent properties of the nanostructures.

3 Results and discussion

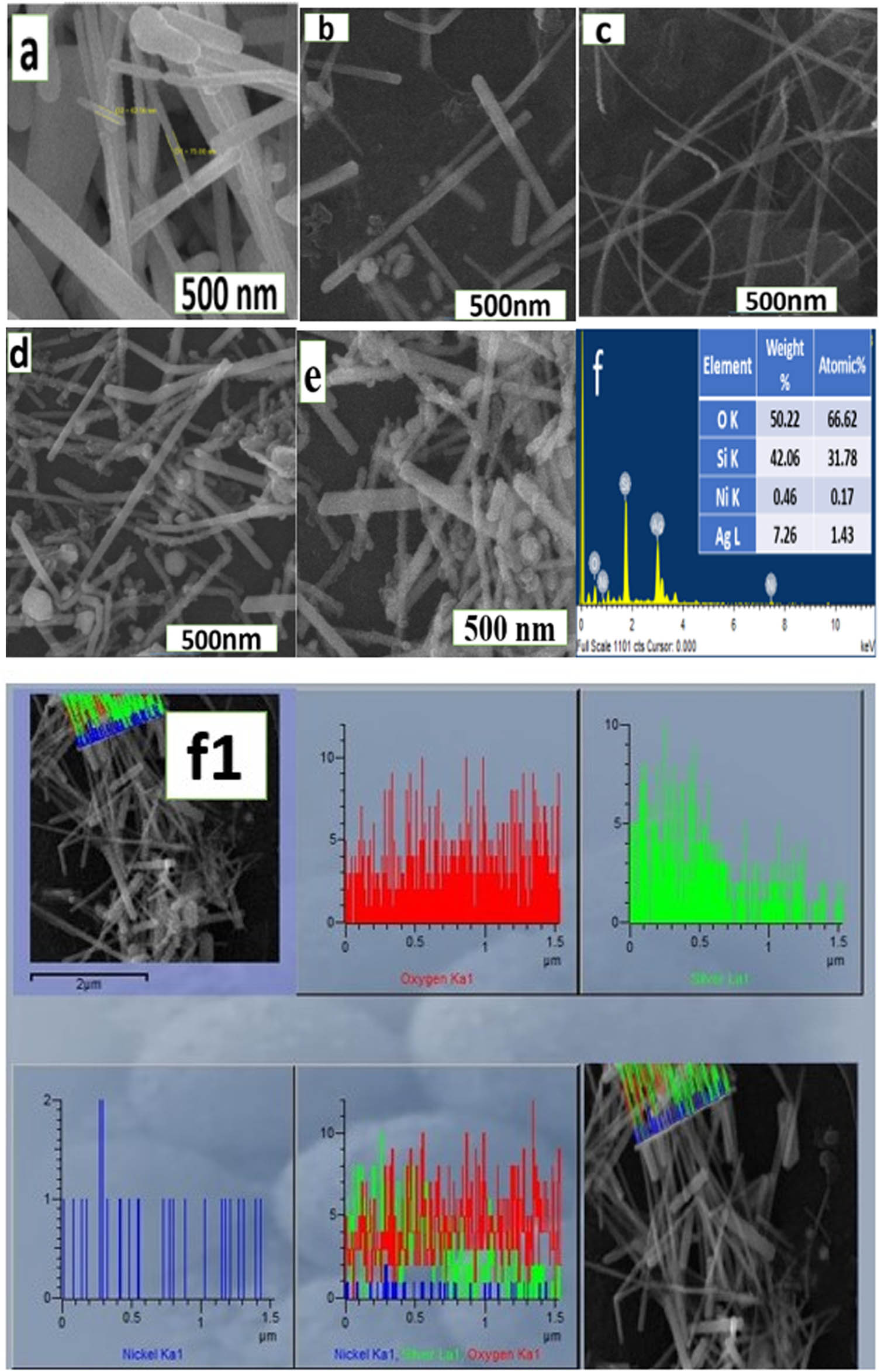

3.1 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and EDX characterization

The SEM micrographs of the pure AgNWs and Ag@Ni nanocables are shown in Figure 1a–e. Figure 1a indicates the AgNWs diameters between 60 and 80 nm and lengths on μm scale. Such dimensions are consistent with reported data [30]. The images indicate that the as-synthesized wires have smooth surfaces at the 500-nm scale. Furthermore, the new structures appear in different morphologies including spheres, cubes, and rod-like NPs (Figure 1a–e). The SEM images of Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and Ag@Ni (0.5 M) are shown in Figure 1b–e. Figure 1b shows the presence of rod-like NPs which co-exist with the AgNWs. Additionally, there are small deposits of spherical NPs around the AgNWs. In these domains, the Ag support is in its initial growth mode. Thus, Figure 1a and b shows that different metal precursors result in highly varied morphologies under otherwise identical conditions. Such results help to understand the impact of the cations and the PVP capping agents used in the synthesis, the reducing ability of the metal precursors, and the potential of multi-metal nuclei to develop stable dimensions. Figure 1c shows NWs along with some NPs. The diameter of the AgNWs is 55–60 nm, but these are interspersed with some ultra-long, thin (30 nm in diameter) AgNWs. The observed diameter of the former in Figure 1d is 57–65 nm, with the presence of ultrathin wires around 31 nm diameter, along with NPs with geometry spherical and cubic shapes. The cubic NPs are also within the 70–75 nm size range. The NWs are still the dominant structures in this case. The small spherical NPs in Figure 1e disappeared upon increasing the concentration of nickel. The diameter of the wires also increased up to 80 nm with the coating of nickel because the tiny nickel NPs are uniformly deposited on their surface.

SEM images of (a) AgNWs (0.1 M) and nanocables (b) Ag@Ni (0.2 M), (c) Ag@Ni (0.3 M), (d) Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and (e) Ag@Ni (0.5 M): (f) EDX pattern and (f1) Line mapping of Ag@Ni (0.2 M).

The images depicted on the SEM were also analyzed using EDX to assess the elemental compositions. The EDX pattern shows the weight percentage of Ag and Ni in the nanocables. Silver is the dominant element in all cases. The existence of Si in the EDX is due to the glass substrate, the reduced silver, Ag(i), and oxygen result from the surface oxidation of these structures. Ag:Ni weight percentage for the nanocables displayed in Figure 1b–e is 3.04:0.44, 7.26:0.46, 18.31:2.40, and 44.55:2.54.

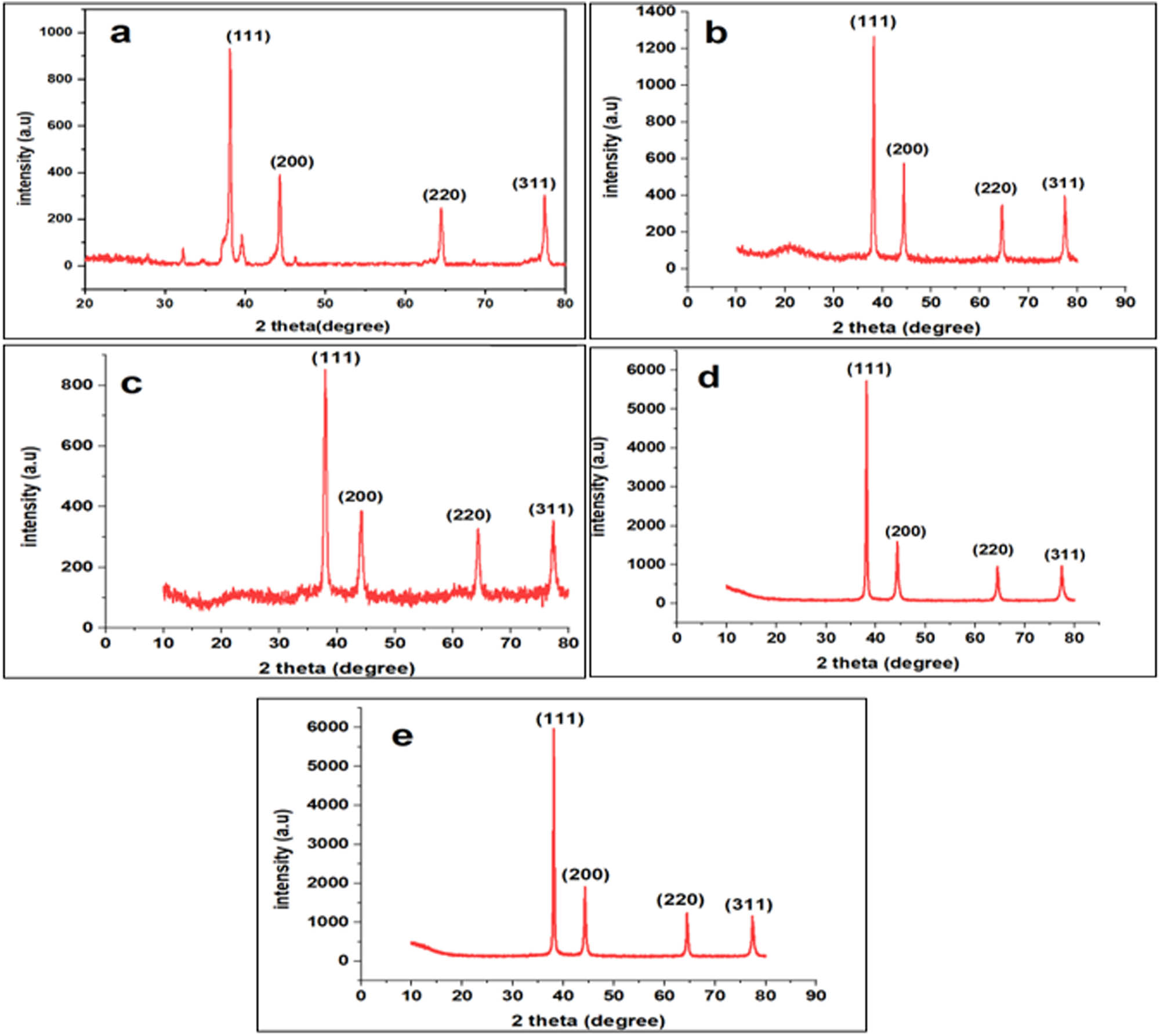

3.2 XRD analysis

XRD was used to study the degree of crystallinity of the AgNWs and Ag@Ni nanocables in Figure 2a–e. According to Figure 2a, four distinct diffraction peaks at 2θ = 38.2°, 44.6°, 65°, and 77.4° have been assigned as planes (111), (200), (220), and (311), respectively. It is worth noting that the peak at 38.02° exhibits relatively high intensity, indicating the anisotropic growth of the (111) phase of Ag during synthesis. An additional peak appeared at 77.4° when data were recorded in the scan range of 10–80° which corresponds to the (311) plane of fcc Ag. The strong and narrow peaks show a highly crystalline nature. The characteristic peak of Ni which was supposed to be at 52° did not appear due to the low concentration of nickel. This shows that the silver phase is dominant in both AgNWs and Ag@Ni nanocables. While Figure 2b and c further shows anisotropic behavior, a peak at 20° derives from PVP, which is present due to its affinity with particles in the sample. Typically, residual polymer shows up in many just-synthesized nanocomposites and is generally seen in the PXRD data as is the case here. The remaining four distinct diffraction peaks of Ag in Figure 2b and c are also in Figure 2a. Subsequently, mass transport on the growing end of the NWs decreased, allowing ample time for existing structures to rearrange to the more stable phase.

XRD pattern of (a) AgNWs (0.1 M), (b) Ag@Ni (0.2 M), (c) Ag@Ni (0.2 M), (d) Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and (e) Ag@Ni (0.5 M).

We have also found that the use of NaCl in the polyol reduction reactions, in which Cl− ions are released, results in an improved yield of AgNWs [31]. The crystallite sizes of the as-synthesized samples were calculated from the full-width at half maximum (FWHM) of the Bragg reflections using the Debye–Scherrer equation:

where D represents the crystallite size (nm), K is the dimensionless shape factor called the Scherrer constant having a value of about 0.94 which can vary with the actual shape of the crystallite, λ is the wavelength of the X-ray source, typically 0.15418 nm, β represents the FWHM intensity in radians, and θ is the Bragg angle or peak position of main crystal plane. The crystallite size is calculated for the samples in Figure 2a–e: 36, 35, 33, 32, and 30 nm by choosing the (111) plane of Ag and showing that the sizes decrease with increasing Ni percent. The lattice spacing was determined using the Bragg equation:

where d represents the lattice spacing, n is the order of diffraction, λ is the X-ray wavelength, and θ is the peak position angle. By choosing the (111) plane of Ag, the lattice spacings were determined to be 2.354, 2.356, 2.358, 2.36, and 2.36 Å. This reduction in spacing results from the Ni atoms having a smaller radius (124 pm) than Ag atoms (144 pm) in the silver lattice. The decrease in crystallite size with increasing Ni content and the presence of single fcc structure peaks are evidence that there is atomic level alloying of the two metal atoms. It is worth noting that the peak at 38.02° is relatively intense, indicating anisotropic growth of Ag at (111) phase and coaxial growth of Ni in the same phase.

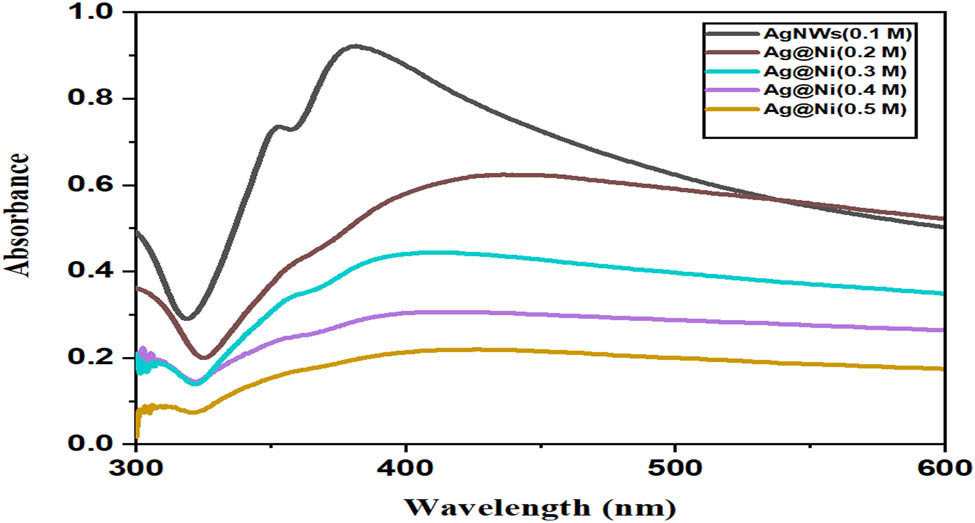

3.3 UV–Vis spectroscopy

SPRs were determined for each sample from the λ max values in the UV–Vis spectra. Figure 3 shows the SPR and the morphological evolution of AgNWs and the nickel-coated AgNWs. The SPR peaks appeared at different wavelengths proving to be dependent on the shapes and sizes of the metal nanostructures [32]. Metal surfaces exhibit plasma-like properties that result from free electrons and positively charged nuclei in the surface layers. SPR occurs near the AgNW surface, as electrons are excited to the conduction band. The SPR peaks give rise to intense colors. Figure 3 shows the spectra of AgNWs (0.1 M), Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and Ag@Ni (0.5 M). The two relatively sharp SPR peaks at 356 and 386 nm result from the transverse mode of the AgNWs. The shoulder peak at 356 nm and the peak at 386 nm are attributed to the out-of-plane quadropole resonance and the out-of-plane dipole resonance of the AgNWs, respectively [33,34]. The broad peak at 386 nm for Ag@Ni nanostructures indicates the presence of NWs as well as particles. The transverse SPR of AgNWs (0.1 M) at 356 nm has been suppressed, a result consistent with nickel deposited on the surface of wires. A slight red shift is also observed in the case of Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and Ag@Ni (0.5 M). The band gap of the AgNWs is calculated using the equation:

where E g is the band gap, h and c are constants, and λ is an absorption wavelength. The calculated band gaps for samples illustrated in Figure 3 are 3.24, 3.07, 3.06, 3.04, and 2.99 eV. The existence of a band gap in Ag nanostructures clearly demonstrates that the ψ function of the electron is restricted in the nanodomain and allowed in the microdomain for the conduction of electrons.

UV–Vis spectra of AgNWs (0.1 M) and the Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and Ag@Ni (0.5 M) nanocables.

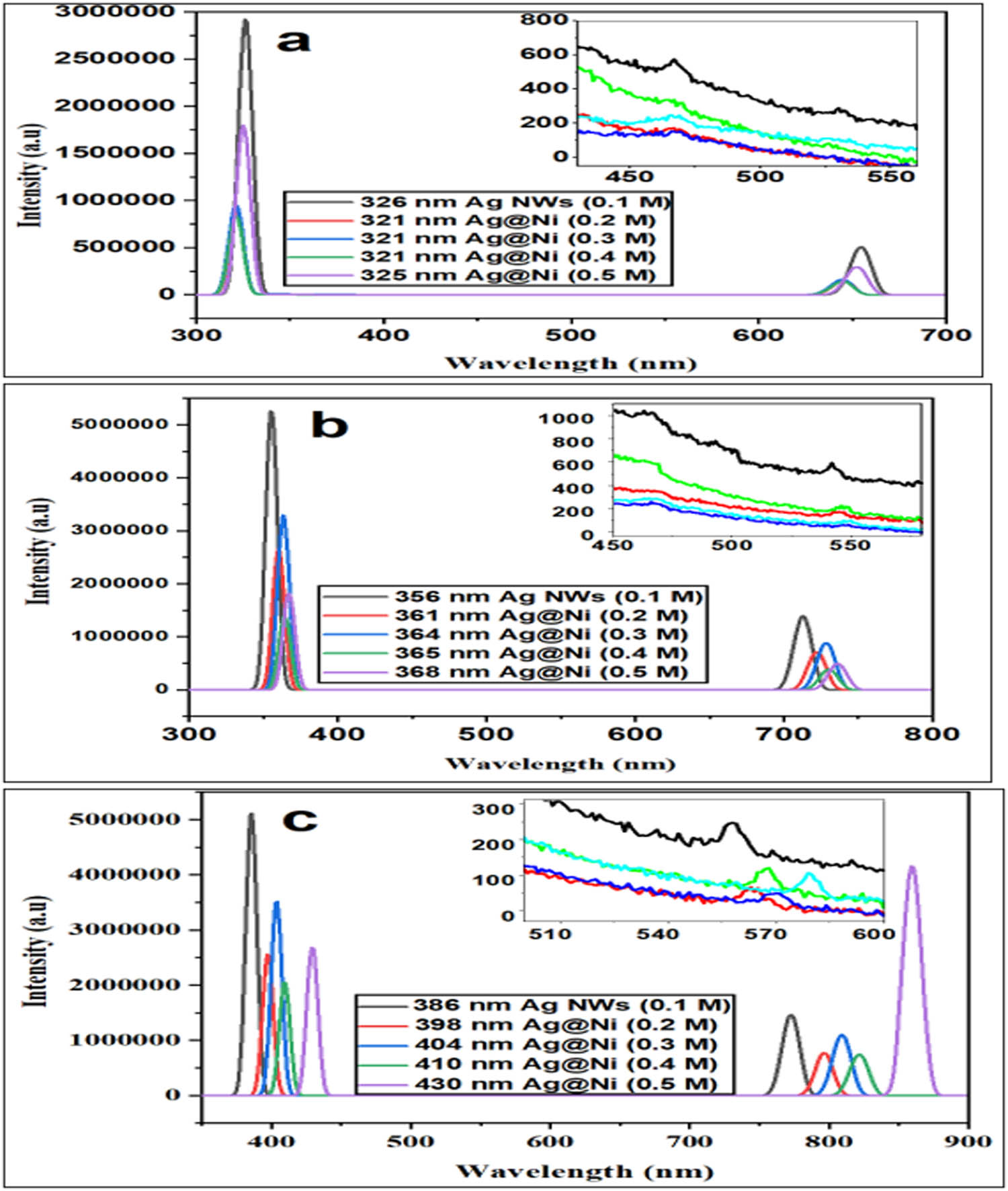

3.4 PL spectroscopy

Metal nanostructures exhibit good light-harvesting behavior because their fluorescence is not limited to a single wavelength. Both fluorescence and absorptions in metal nanostructures are broad. These optical characteristics frequently render metal nanostructures suitable candidates for photovoltaic applications [35]. Figure 4a–c shows the PL spectra of AgNWs (0.1 M), Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and Ag@Ni (0.5 M) at different excitation wavelengths. In Figure 4b, the different excitation wavelengths of 356, 361, 364, 365, and 368 nm were used for each sample and the respective emissions were recorded. All the samples gave an emission of around 500 nm, but the intensity of the emitted light was reduced upon coating AgNWs with nickel. The same phenomenon is the case in Figure 4c where excitation wavelengths of 386–430 nm were used for AgNWs and Ag@Ni nanostructures AgNWs (0.1 M), Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and Ag@Ni (0.5 M), respectively, and emissions were recorded between 500 and 600 nm. The fluorescence of Ag is more evident in the AgNWs (0.1 M) sample and more intense compared to the other samples. High enhancement of fluorescence emission, improved fluorophore photostability, and significant reduction of fluorescence lifetime were derived from the high aspect ratio of the AgNWs. The data showed that the Ag emission spectra follow the relationship in the equation:

PL spectra (a–c) of AgNWs (0.1 M) and nanocables Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), Ag@Ni (0.4 M), and Ag@Ni (0.5 M) at different wavelengths.

which reflect the non-linear second-order optical properties of confirmed metal nanostructures. These, in turn, result from electric-dipole interaction with radiation of strong intensity.

3.5 Catalytic activity of the AgNWs and Ag@Ni nanocables

The nickel is used in a variety of catalytic reactions, such as alcohol oxidation and the hydrogenation of unsaturated olefins. It is also an important catalyst precursor for ethylene homopolymerization and the alternating copolymerization of ethylene with carbon monoxide [36]. For the reduction of carbonyl, imine, nitrile, and alkyne groups, NaBH4 is commonly used, but it is the least effective for the reduction of nitro residues. Therefore, many researchers use different nanocatalysts to improve nitro-to-amino reduction selectivity. Recently, nano-Ag has been successfully employed for the reduction of nitro groups by NaBH4 [37]. The yellow-colored aqueous mixture of p-NP and sodium borohydride shows an absorption maximum at 400 nm due to the formation of p-nitrophenolate ions. Reduction does not proceed in the absence of catalyst and the absorption peak remains unchanged over time. However, after the addition of catalyst, a change in the absorption pattern is observed. The yellow solution becomes colorless at the end of reaction, indicating the reduction of p-NP to p-AP. AgNWs (0.1 M), Ag@Ni (0.2 M), Ag@Ni (0.3 M), and Ag@Ni (0.4) converted the phenolate ions into p-AP in 48, 40, 36, and 26 min, respectively. The speed of reduction correlates with the thickness of the Ni layer and higher Ni content in the Ag/Ni nanocomposite. The main peak of the nitrophenolate at 400 nm decreases with time; whereas, a second peak at 300 nm, of the aminophenol product, increases slowly. Finally, the isobestic point is clearly observed in all the Ag@Ni nanocomposites around 314 nm. Figure 5 shows the successive UV–Vis absorption spectra of the reduction of p-NP by NaBH4 in the presence of AgNWs or Ag@Ni nanocable catalysts. The kinetic reaction rate order was calculated from the change in concentration of the substrate A (phenolate ions) as shown in Figure 6. The plot of 1/[A] versus time reveals second-order kinetics.

Catalytic activities of (a) AgNWs (0.1 M), (b) Ag@Ni (0.2 M), (c) Ag@Ni (0.3 M), and (d) Ag@Ni (0.4 M) for reduction of p-NP to p-AP by NaBH4.

![Figure 6

Plot of 1/[A] versus time for reduction of p-NP to p-AP by NaBH4 in aqueous solution, showing good second-order kinetics.](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2024-0010/asset/graphic/j_secm-2024-0010_fig_006.jpg)

Plot of 1/[A] versus time for reduction of p-NP to p-AP by NaBH4 in aqueous solution, showing good second-order kinetics.

4 Conclusions

This study reports a new and facile approach to fabricate metal@metal nanocomposites containing Ag and Ni. Using the polyol method, Ag@Ni nanocables with different concentrations of Ni were successfully synthesized. The product of the syntheses was confirmed, using UV–Vis spectroscopy, SEM coupled with EDX, and XRD. SEM image shows that with changing the metal concentration, the morphology is changed. The suppression of transverse SPR of AgNWs at 356 nm confirmed that the AgNW surfaces were coated with nickel. XRD showed the characteristic sharp peaks of silver. The Ag-based nanomaterials exhibited good light harvesting properties, which were assessed through PL spectroscopy. Ni-containing nanocomposites catalyzed the facile and selective reduction of p-NP to p-AP by sodium borohydride. The time required for the reduction decreased with increasing nickel content in the silver-nickel NWs (Table 1). This comparison clearly shows that the silver@nickel nanocables are more efficient catalysts for p-NP reduction than Ag nanowires. In addition, the new nanocomposites generally enhance the ability of NaBH4 to reduce nitro groups. These silver nickel nanocomposites may well have enhanced rates and selectivities in other Ni-based catalytic reductions. The nanocomposite formed has extensive potential for use in many sectors across the medical, electronic, and environmental fields.

Comparison of catalyst quantity and time of reduction of p-NP

| Sr. no | Name of sample | Reduction time (min) | Slope (k) (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AgNWs | 48 | 0.0050 |

| 2 | Ag@Ni (0.2 M) | 40 | 0.0052 |

| 3 | Ag@Ni (0.3 M) | 36 | 0.0186 |

| 4 | Ag@Ni (0.4 M) | 26 | 1.03295 |

Acknowledgments

The ORICMUST and HEC (Project Number: 7183) Pakistan are gratefully acknowledged for the financial support to the study.

-

Funding information: The study was funded by The ORICMUST and HEC (Project Number: 7183).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. SS: investigation, supervision, writing – original draft. TA: investigation, validation. ZA: conceptualization, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. MAC: conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition. MA: methodology, software.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article or its supplementary materials can be shared upon request.

References

[1] Emam HE, Ahmed HB. Comparative study between homo-metallic & hetero-metallic nanostructures based agar in catalytic degradation of dyes. Int J Biol macromolecules. 2019;138:450–61.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.07.098Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Ahmad Z, Choudhary M, Mirza M, Mirza J. Synthesis and characterization of Ag@ polycarbazole nanoparticles using different oxidants and their dispersion behavior. Mater Science-Poland. 2016;34(1):79–84.10.1515/msp-2016-0019Search in Google Scholar

[3] Guo H, Chen Y, Chen X, Wen R, Yue G-H, Peng D-L. Facile synthesis of near-monodisperse Ag@ Ni core–shell nanoparticles and their application for catalytic generation of hydrogen. Nanotechnology. 2011;22(19):195604.10.1088/0957-4484/22/19/195604Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Kumar R, Mondal K, Panda PK, Kaushik A, Abolhassani R, Ahuja R, et al. Core–shell nanostructures: perspectives towards drug delivery applications. J Mater Chem B. 2020;8(39):8992–9027.10.1039/D0TB01559HSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Perumbilavil S, López‐Ortega A, Tiwari GK, Nogués J, Endo T, Philip R. Enhanced ultrafast nonlinear optical response in ferrite core/shell nanostructures with excellent optical limiting performance. Small. 2018;14(6):1701001.10.1002/smll.201701001Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Vysakh A, Babu CL, Vinod C. Demonstration of synergistic catalysis in Au@ Ni bimetallic core–shell nanostructures. The J Phys Chem C. 2015;119(15):8138–46.10.1021/jp5128089Search in Google Scholar

[7] Su L, Jing Y, Zhou Z. Li ion battery materials with core–shell nanostructures. Nanoscale. 2011;3(10):3967–83.10.1039/c1nr10550gSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Duan S, Wang R. Bimetallic nanostructures with magnetic and noble metals and their physicochemical applications. Prog Nat Sci: Mater Int. 2013;23(2):113–26.10.1016/j.pnsc.2013.02.001Search in Google Scholar

[9] Fan Z, Huang X, Tan C, Zhang H. Thin metal nanostructures: synthesis, properties and applications. Chem Sci. 2015;6(1):95–111.10.1039/C4SC02571GSearch in Google Scholar

[10] Nasrollahzadeh M, Issaabadi Z, Sajjadi M, Sajadi SM, Atarod M. Types of nanostructures. Interface Sci Technol. 2019;28:29–80.10.1016/B978-0-12-813586-0.00002-XSearch in Google Scholar

[11] Liu Y, Tang Z. Multifunctional nanoparticle@ MOF core–shell nanostructures. Adv Mater. 2013;25(40):5819–25.10.1002/adma.201302781Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Wu S-H, Chen D-H. Synthesis and characterization of nickel nanoparticles by hydrazine reduction in ethylene glycol. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;259(2):282–6.10.1016/S0021-9797(02)00135-2Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] McKiernan M, Zeng J, Ferdous S, Verhaverbeke S, Leschkies KS, Gouk R, et al. Facile synthesis of bimetallic Ag/Ni core/sheath nanowires and their magnetic and electrical properties. Small. 2010;6(17):1927–34.10.1002/smll.201000801Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Santhi K, Thirumal E, Karthick S, Kim H-J, Nidhin M, Narayanan V, et al. Synthesis, structure stability and magnetic properties of nanocrystalline Ag–Ni alloy. J Nanopart Res. 2012;14:1–12.10.1007/s11051-012-0868-7Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zhang C, Liu S, Mao Z, Liang X, Chen B. Ag–Ni core–shell nanowires with superior electrocatalytic activity for alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. J Mater Chem A. 2017;5(32):16646–52.10.1039/C7TA04220ESearch in Google Scholar

[16] Lee YW, Kim M, Kim ZH, Han SW. One-step synthesis of Au@ Pd core− shell nanooctahedron. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(47):17036–7.10.1021/ja905603pSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Lee I, Han SW, Kim K. Production of Au–Ag alloy nanoparticles by laser ablation of bulk alloys. Chem Commun. 2001;18:1782–3.10.1039/b105437fSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Liu X, Wang D, Li Y. Synthesis and catalytic properties of bimetallic nanomaterials with various architectures. Nano Today. 2012;7(5):448–66.10.1016/j.nantod.2012.08.003Search in Google Scholar

[19] Major KJ, De C, Obare SO. Recent advances in the synthesis of plasmonic bimetallic nanoparticles. Plasmonics. 2009;4(1):61–78.10.1007/s11468-008-9077-8Search in Google Scholar

[20] Tsuji M, Hikino S, Matsunaga M, Sano Y, Hashizume T, Kawazumi H. Rapid synthesis of Ag@ Ni core–shell nanoparticles using a microwave-polyol method. Mater Lett. 2010;64(16):1793–7.10.1016/j.matlet.2010.05.032Search in Google Scholar

[21] Li G, Tang Z. Noble metal nanoparticle@ metal oxide core/yolk–shell nanostructures as catalysts: recent progress and perspective. Nanoscale. 2014;6(8):3995–4011.10.1039/C3NR06787DSearch in Google Scholar

[22] Mushtaq S, Ahmad Z, Hoskins C, Shahpal A, Choudhary MA. A facile synthesis of palladium encased Ag nanowires and its effect on fluorescence and catalysis. Mater Res Express. 2019;6(5):055015.10.1088/2053-1591/ab0180Search in Google Scholar

[23] Gui Y-Y, Sun L, Lu Z-P, Yu D-G. Photoredox sheds new light on nickel catalysis: from carbon–carbon to carbon–heteroatom bond formation. Org Chem Front. 2016;3(4):522–6.10.1039/C5QO00437CSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Natrup F, Graf W. Sherardizing: corrosion protection of steels by zinc diffusion coatings. In Thermochemical Surface Engineering of Steels. Woodhead Publishing; 2015. p. 737–5010.1533/9780857096524.5.737Search in Google Scholar

[25] Bhaviripudi S, Mile E, Steiner SA, Zare AT, Dresselhaus MS, Belcher AM, et al. CVD synthesis of single-walled carbon nanotubes from gold nanoparticle catalysts. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(6):1516–7.10.1021/ja0673332Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Zhan L, Xu Z. Separating and recycling metals from mixed metallic particles of crushed electronic wastes by vacuum metallurgy. Environ Sci & Technol. 2009;43(18):7074–8.10.1021/es901667mSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Wu L, Zhang X, Tao Z. A mild and recyclable nano-sized nickel catalyst for the Stille reaction in water. Catal Sci Technol. 2012;2(4):707–10.10.1039/c2cy00466fSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Song X, Zhang D. Bimetallic Ag–Ni/C particles as cathode catalyst in AFCs (alkaline fuel cells). Energy. 2014;70:223–30.10.1016/j.energy.2014.03.116Search in Google Scholar

[29] Rahaim RJ, Maleczka RE. Pd-catalyzed silicon hydride reductions of aromatic and aliphatic nitro groups. Org Lett. 2005;7(22):5087–90.10.1021/ol052120nSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Zhang D, Qi L, Yang J, Ma J, Cheng H, Huang L. Wet chemical synthesis of silver nanowire thin films at ambient temperature. Chem Mater. 2004;16(5):872–6.10.1021/cm0350737Search in Google Scholar

[31] Korte KE, Skrabalak SE, Xia Y. Rapid synthesis of silver nanowires through a CuCl-or CuCl 2-mediated polyol process. J Mater Chem. 2008;18(4):437–41.10.1039/B714072JSearch in Google Scholar

[32] Yan X, Ma J, Xu H, Wang C, Liu Y. Fabrication of silver nanowires and metal oxide composite transparent electrodes and their application in UV light-emitting diodes. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2016;49(32):325103.10.1088/0022-3727/49/32/325103Search in Google Scholar

[33] Zhu J-J, Kan C-X, Wan J-G, Han M, Wang G-H. High-yield synthesis of uniform Ag nanowires with high aspect ratios by introducing the long-chain PVP in an improved polyol process. J Nanomater. 2011;2011:1–7.10.1155/2011/982547Search in Google Scholar

[34] Yi Z, Xu X, Tan X, Liu L, Zhang W, Yi Y, et al. Microwave-assisted polyol method rapid synthesis of high quality and yield Ag nanowires. Surf Coat Technol. 2017;327:118–25.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2017.08.024Search in Google Scholar

[35] Gong Y, Zou C, Yao Y, Fu W, Wang M, Yin G, et al. A facile approach to synthesize rose-like ZnO/reduced graphene oxide composite: fluorescence and photocatalytic properties. J Mater Sci. 2014;49(16):5658–66.10.1007/s10853-014-8284-2Search in Google Scholar

[36] Klabunde U, Tulip T, Roe D, Ittel S. Reaction of nickel polymerization catalysts with carbon monoxide. J Organomet Chem. 1987;334(1–2):141–56.10.1016/0022-328X(87)80045-1Search in Google Scholar

[37] Ahmad Z, Maqsood M, Mehmood M, Ahmad MJ, Choudhary MA. Synthesis and characterization of pure and nano-Ag impregnated chitosan beads and determination of catalytic activities of nano-Ag. Bull Chem React Eng Catal. 2017;12(1):127–35.10.9767/bcrec.12.1.860.127-135Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective