Abstract

This study aims to develop composite plates using silkworm cocoon waste- and hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced polymer composite using epoxy resin as a matrix to replace synthetic fibers in bulletproof plates. The fabrication involved mixing 70 g of silkworm cocoon waste with 240 g of resin and 70 g of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene, followed by cold compression molding. Tensile and impact tests on the resulting samples, using a standardized 9 mm projectile, showed a tensile strength of 107.4 MPa and an elastic modulus of 1240.3 MPa. With a back face signature (BFS) of 21.25 mm, the samples effectively intercepted the projectile, satisfying the stringent U.S. National Institute of Justice standard 0101.06, which specifies a maximum BFS of 44 mm. In comparison with hemp woven materials, silkworm cocoon waste has proven to be a promising substitute for both tensile and impact evaluations, attracting considerable interest and underscoring its role as a reinforcing agent for national fiber. This research has significant implications for industries and applications requiring affordable, lightweight, and efficient safeguards against ballistic dangers. Ultimately, it contributes to the progress of ballistic protection methods by encouraging exploration into innovative, bio-inspired, and sustainable materials capable of achieving superior impact resistance.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, the global incidence of terrorist attacks has surged, with Thailand among the nations witnessing irregular occurrences, particularly within its southern provinces. In response to this rising threat to human life, the deployment of protective armor has become imperative. Personal armor assumes a critical role in safeguarding individuals against projectiles, expertly countering penetration while mitigating impact forces. Historically, personal armor has been created from a range of materials including metal alloys, wood, glass, ceramics, steel, and aluminum [1]. Nevertheless, despite their efficiency in intercepting projectiles, these conventional materials are troubled by weight and thickness, thereby causing discomfort during prolonged wear and incurring significant costs. In the search for optimal materials for personal armor, principal considerations encompass attributes such as lightweight construction, toughness, high tensile strength, and remarkable energy dissipation capabilities. Notably, recent research has shown increasing interest in natural fiber composites due to their potential to enhance ballistic impact [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. The highlights are examples of natural fibers used as reinforcement in composites, such as jute, flax, and hemp, along with nonwoven flax and hemp combined with polypropylene serving as the matrix. Furthermore, it explores the use of jute and hemp fibers, sisal, bagasse, and alfa fiber in conjunction with epoxy resin. Distinguished by their lightweight structure, vigorous structural integrity, textured surface morphology, eco-friendly characteristics, and economic capability stemming from their utilization of recycled materials, these composites offer a compelling proposition. Moreover, they have commendable ballistic performance at a fraction of the weight and cost experienced by conventional counterparts [9,10].

Typically, an anti-ballistic plate comprises a multi-layered configuration. The initial layer, typically composed of either ceramic or natural fiber composite, functions to deform the tip of a ballistic projectile while effectively dissipating and absorbing their kinetic energy. Subsequently, a secondary layer, predominantly comprising materials such as Kevlar or ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), serves to further absorb residual kinetic energy. Researchers have extensively investigated various types of natural fiber composites integrated with aramid fabrics (i.e., Kevlar or UHMWPE) for ballistic impact applications [11,12,13,14,15]. Examples include composites reinforced with ramie fabric and epoxy, kenaf reinforced with virgin high-density polyethylene, curaua fiber reinforced with aramid fabric, coconut shell powder-epoxy composite reinforced with Twaron fabric, giant bamboo fibers reinforced with epoxy and aramid fabric, and sisal fibers reinforced with epoxy resin and aramid fabric. Although Kevlar/UHMWPE composites exhibit efficiency in impeding projectiles, their high cost remains a significant limit. In response, researchers are engaged in efforts to reduce this financial impact, whether through reducing the number of Kevlar/UHMWPE layers or substituting them with cost-effective natural fibers like silkworm cocoon waste. Silkworm cocoons, products of silkworm caterpillars, represent a unique natural structure filled with notable mechanical properties. However, the utilization of environmentally sustainable materials such as silkworm cocoon waste is being carried out with a focus on sustainability. Research conducted by Sashina and Yakovleva [16] underscores the significance of this attempt, revealing that silk waste constitutes a substantial proportion 50 wt% of the byproducts generated during silk production.

Silkworm cocoon waste, encompassing fragments, defects, discarded remnants, and unspooled husks following silkworm extraction, presents a viable option as a natural fiber residue. Its integration into epoxy resin composites not only satisfies the imperative for sustainable materials but also capitalizes on the abundant resources afforded by the silk industry. Moreover, silkworm cocoon waste exhibits distinctive attributes, including its lightweight nature and biodegradability, rendering it conducive to diverse applications. In the realm of composite fabrication, silkworm cocoon waste assumes a pivotal role as a reinforcing fiber due to its virtuous mechanical properties, notably, its toughness, which reduces the back face signature (BFS) of composite plates [17,18]. Epoxy resin, renowned for its exceptional adhesion, high strength, durability, and chemical resistance, serves as the matrix material. Nevertheless, the utilization of silkworm cocoon waste for ballistic applications remains relatively underexplored. Thus, the primary objective of this investigation is to fabricate a hybrid composite plate comprising UHMWPE/silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy composites via the cold pressing technique. This method, involving composite formation under ambient conditions using epoxy resins, is favored for its cost-effectiveness and simplicity. To assess the ballistic performance of the composite plate, a 9 mm, 8 g projectile was employed for impact testing. The fracture morphology of the natural fiber waste at the impact zone was investigated utilizing scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Subsequently, the ballistic efficiency of the hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite (cocoon waste composite) specimens was compared with that of hybrid hemp woven-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite (hemp woven composite), as hemp has garnered substantial attention and proven efficiency as a reinforcing constituent within polymer matrices in previous research activities [19,20].

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

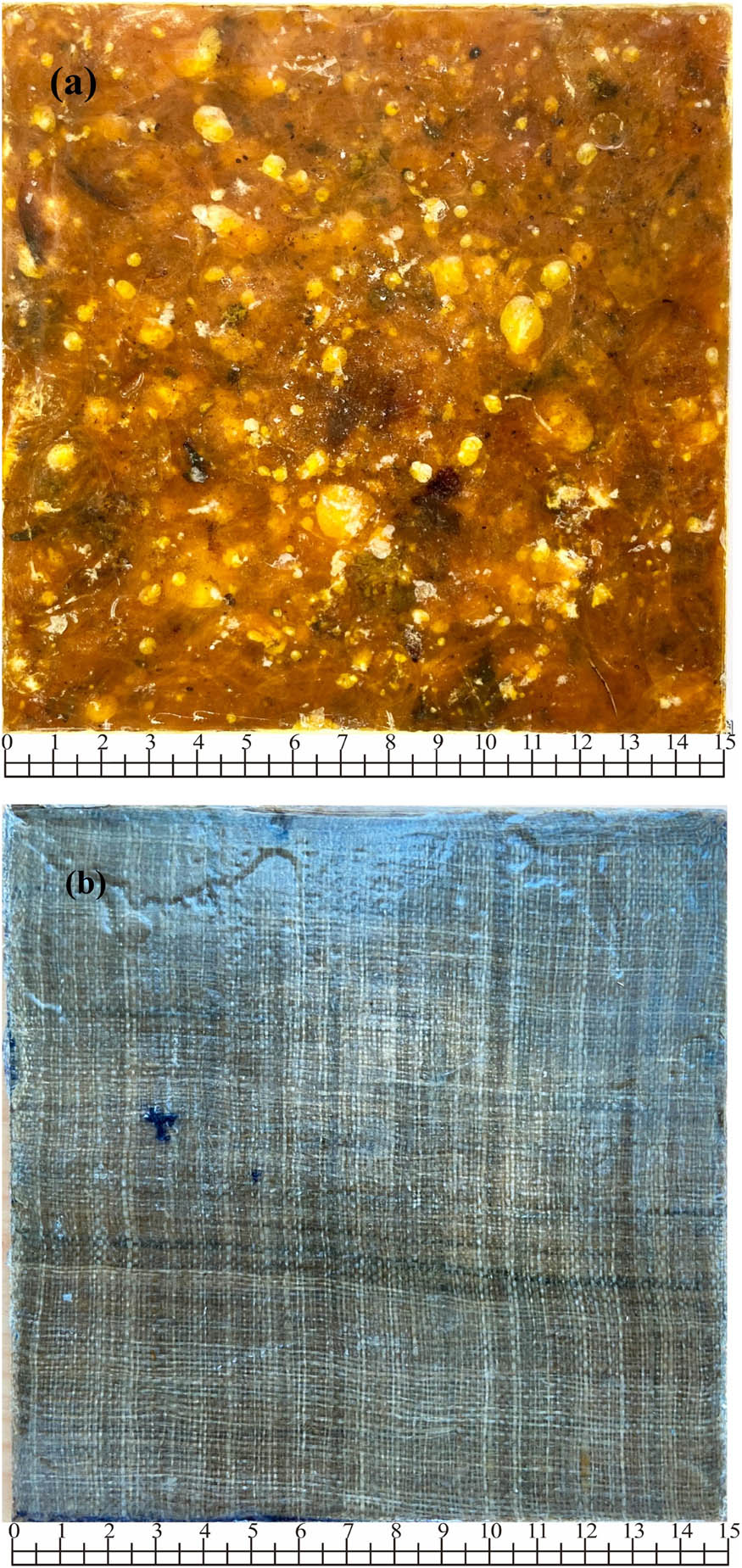

Bombyx mori silkworm cocoon waste was obtained from silk-producing communities located in the northeastern region of Thailand. These cocoons underwent careful preparation, involving the cutting of their tips and the removal of silkworm larvae from within. Concurrently, the hemp woven material was sourced from the hemp fiber product community enterprise situated in Chang Mai, Thailand. Both the silkworm cocoon waste and hemp woven specimens are depicted in Figure 1(a) and (b), respectively. The matrix employed in this study was epoxy resin YD 582, a modified bisphenol-A-based epoxy resin renowned for its vigorous properties. The hardening agent utilized, EPOTEC TH 7278, was a modified amine supplied by J.N. TRANSOS Company, Thailand. Additionally, the UHMWPE was sourced from a reputable Thai company based in Thailand.

Material for reinforced composite: (a) silkworm cocoon waste, (b) hemp woven, and (c) single UHMWPE sheet.

2.2 Procedures

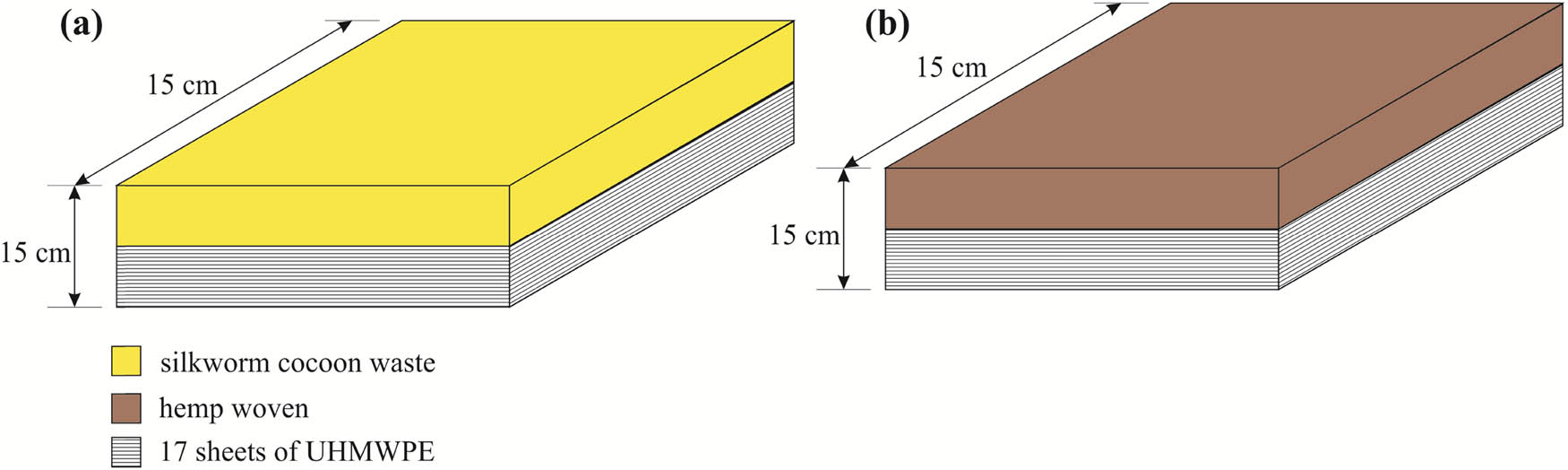

The compression molding technique was employed to fabricate the composite plate. In the preparatory phase, either silkworm cocoon waste or hemp woven material, weighing approximately 70 g, underwent compression via a hydraulic press at 6 MPa within a mold box measuring 15 cm in width, 15 cm in length, and 20 cm in height, resulting in the formation of a thin sheet. Particular care was taken to ensure uniform distribution of the silkworm cocoon waste, whereas the hemp woven material was cut to fit the dimensions of 15 cm × 15 cm. A hydraulic pressure of 6 MPa was applied to the mold for 1 h. The UHMWPE was split into 15 cm × 15 cm sheets, totaling approximately 70 g in weight, as depicted in Figure 1(c). Each sheet of UHMWPE was bonded together using epoxy resin. Subsequently, after complete adhesion of the UHMWPE sheets, either the silkworm cocoon waste or hemp woven thin sheet was positioned atop the UHMWPE layer. The epoxy resin was blended with the hardener in a weight ratio of 4:1, totaling approximately 240 g as a matrix solution. Before pouring, the matrix solution underwent degassing, followed by using a brush to eliminate air bubbles. The matrix solution was then poured onto the UHMWPE layer, along with either the silkworm cocoon waste or hemp woven sheet, within a mold box measuring 15 cm in width, 15 cm in length, and 5 cm in height, for 3 h. Subsequently, it was subjected to compression at 6 MPa for 12 h at ambient temperature. Upon removal from the mold, the composite underwent curing at 80°C for 4 h. Finally, composite plate samples weighing a total of 380 g (i.e., cocoon waste composite) for ballistic protection with two layers were obtained, as depicted in Figure 2. The details and designation for compliant hybrid composites are defined in Table 1, and the graphical representation of these composites is represented in Figure 3.

Composite plate samples before impact test with size 15 cm × 15 cm: (a) hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite and (b) hybrid hemp woven-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite.

Test specimen classification for testing

| Specimen type | Designation | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite | cocoon waste composite | silkworm cocoon waste/17 sheets of UHMWPE + epoxy |

| Hybrid hemp woven-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite | hemp woven composite | hemp woven/17 sheets of UHMWPE + epoxy |

Schematic representation of compliant composite, (a) hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite and (b) hybrid hemp woven-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite.

2.3 Characterization of composite specimens

The tensile testing of samples was carried out at room temperature following the ISO-527-4 standard using a 30 kN system, which is an internationally recognized testing standard for assessing the tensile properties of fiber-reinforced plastic composites. Strength and modulus were assessed at a deformation rate of 2 mm/min. Each test included five samples, and the average values were recorded.

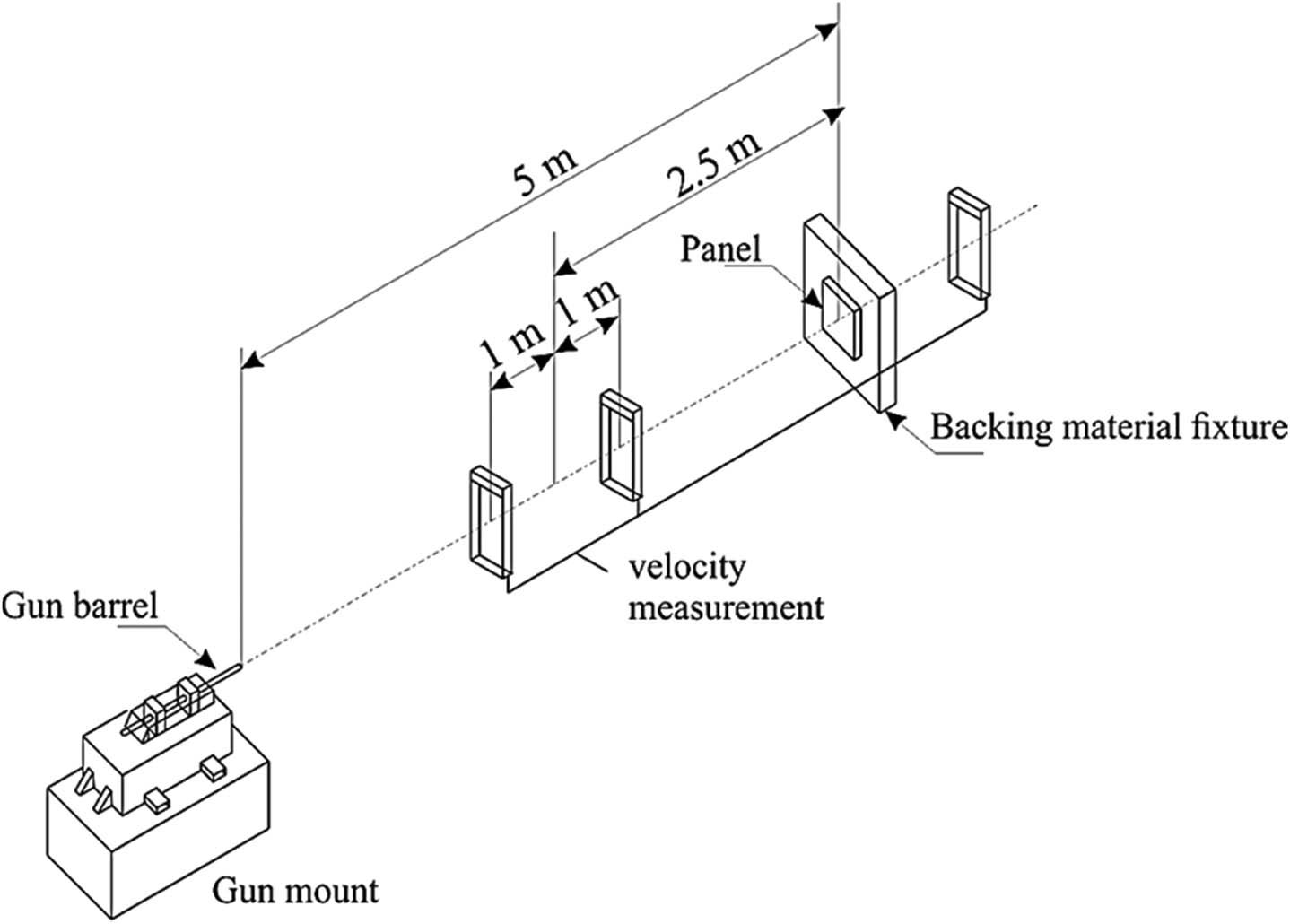

The composite plate samples underwent an impact test to assess the armor’s resistance to penetration. A 9 mm, 8 g weight ammunition was used for the test. The shooting device, comprising a gun barrel with a laser sight, was positioned 5 m away from the composite plate samples, as shown in Figure 4. The shooting was conducted horizontally perpendicular to the composite plate samples. The impact of kinetic energy absorption (E abs) can be calculated using the following equation:

where m is the mass of the ammunition; v i is the projectile’s impact velocity; and v r is the residual velocity after the impact. The fracture mechanisms of the composite plate after the impact test were investigated by a JEOL JSM-5900LV SEM at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV.

Experimental setup of impact test.

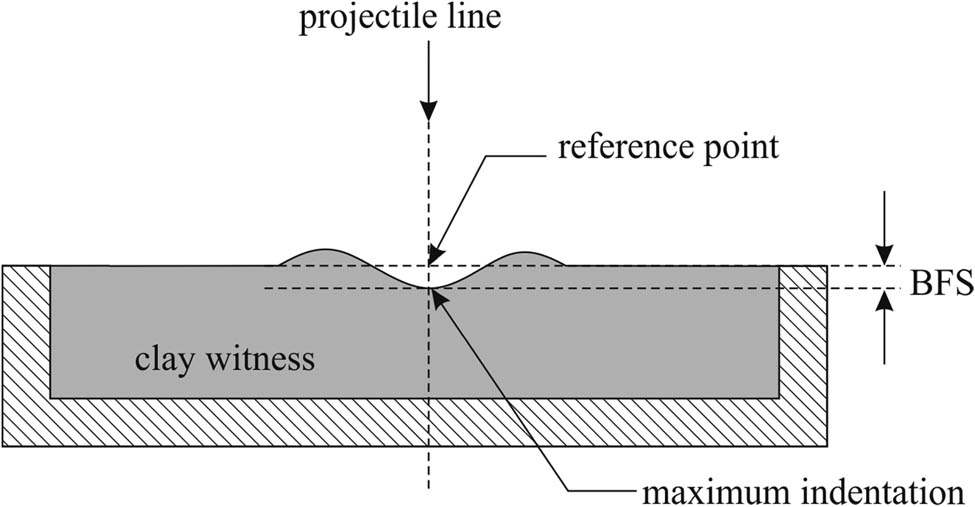

The BFS, which is the extent of indentation in the clay witness caused by a nonperforating impact on the sample, was measured with a 0.01 mm Mitutoyo vernier caliper. The caliper wings were placed on the plane surface near the indentation rim. The depth caliper baseline was identified as this planar surface, as demonstrated in Figure 5.

BFS measurement.

3 Results and discussion

Hemp woven emerges as a natural material exhibiting considerable promise as a composite reinforcement agent, a conclusion substantiated by the investigations conducted by A. Consequently, in the context of this study, hemp woven was considered suitable for comparison with silkworm cocoon waste, given their shared natural origins. Tensile strength, denoting a material’s capacity to endure tensile forces along the vertical axis, and strain, representing its flexibility until reaching failure, constitute pivotal mechanical attributes. Examination of these mechanical properties, exactly outlined in Table 2, revealed noteworthy findings: the cocoon waste composite plate demonstrated a tensile strength of 107.4 MPa and an elastic modulus of 1240.3 MPa, slightly surpassing those of hemp woven. Our main focus in this study was to identify the material’s maximum tensile strength, which is a research goal corroborated by previous academic studies, especially those conducted by Han et al., Loh and Tan [18,21]. Although our presentation exclusively focuses on the tensile strength and elastic modulus values displayed in Table 2, with minimal discussion on the material’s behavior during testing, we acknowledge the necessity for further exploration in this field. Throughout the duration of this study, careful oversight was exercised in controlling the alignment, distribution, and volume fraction of reinforcement, aimed at optimizing tensile strength. As a consequence of our rigorous methodologies, the integration of cocoon waste reinforcement material yielded substantial enhancements in tensile strength, a phenomenon suitably substantiated by the scholarly observations made by Anidha et al. and Tanguy et al. [7,22]. Moreover, our previous investigation [23] corroborated the utility of silkworm cocoon waste as a reinforcement agent within an epoxy matrix. It demonstrated that this material contributes significantly to enhancing structural integrity. Specifically, the empirical evidence explained a remarkable increase of over 41% in tensile strength when the proportion of silkworm cocoon waste reached 42% of the composite weight, contrasting with the absence of such reinforcement.

Mechanical properties of composite plate sample

| Composite plate sample | Tensile strength (MPa) | Elastic of modulus (MPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite | 107.36 ± 2.03 | 1240.32 ± 1.38 |

| Hybrid hemp woven-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite | 103.10 ± 1.38 | 1108.12 ± 2.59 |

The aim of this research is to develop simple and cost-effective composite plates. To achieve this, a method employing cold pressing was chosen to fabricate the composite plate material, enabling effective adhesion of the resin and reinforcement materials. Although the study did not investigate enhancing the adhesion properties between epoxy and UHMWPE, further exploration in this area was recommended. Two factors may contribute to the enhanced interfacial properties of cocoon waste composite. Chemically, cocoon waste fibers possess both hydrophobic and hydrophilic structural domains [24], facilitating polar-polar and hydrophobic interactions with the chemical groups in the epoxy matrix. However, morphologically, strong interfacial interactions may be hindered by an unfavorable contribution from the smooth surface morphology of silk fibers, as reported in previous studies [25]. It is hypothesized that in our scenario, hydrophobic interaction plays a crucial role, resulting in the observed improved interfacial characteristics of cocoon waste composite. The significant difference in hydrophobicity between epoxy and UHMWPE presents challenges in achieving strong bonding between these materials. While epoxy exhibits moderate hydrophobic properties, UHMWPE is highly hydrophobic, leading to limited affinity between their surfaces and hindering efficient adherence. Academic research has addressed this issue by exploring various surface modification techniques to enhance the compatibility of epoxy and UHMWPE. Plasma treatment, chemical functionalization, and the use of coupling agents have been investigated as methods to improve the bonding capacities of both materials by modifying their surface properties [26,27]. An alternative approach to this problem is to pretreat the UHMWPE, although this falls beyond the scope of this paper. Additionally, the tensile and elastic modulus properties of specific silk-reinforced composites described in recent literature vary depending on the matrix system employed. These composites utilized long continuous silk fiber [28], short-chopped fiber [29], and spun silk fabric [30,31] as the reinforcing phase. It is evident that the mechanical properties of these composites differ significantly based on the specific characteristics of the matrix system utilized. The adhesion between reinforcement and epoxy resin in composites involves various factors, including mechanical interlocking, chemical bonding, surface treatment, and surface morphology [32]. In the case of cocoon waste, a significant mechanism is mechanical interlocking, where the rough surface of the outermost sericin layer of the reinforcement material locks into the cured epoxy matrix, as evidenced by research findings from Morin and Alam [33]. While the composite tensile properties of silkworm cocoon waste may not exceed those of conventional epoxy resins, it offers advantages as a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable natural fiber. Moreover, when compared to hemp woven used as a reinforcing material, cocoon waste demonstrates superior tensile strength and elastic modulus.

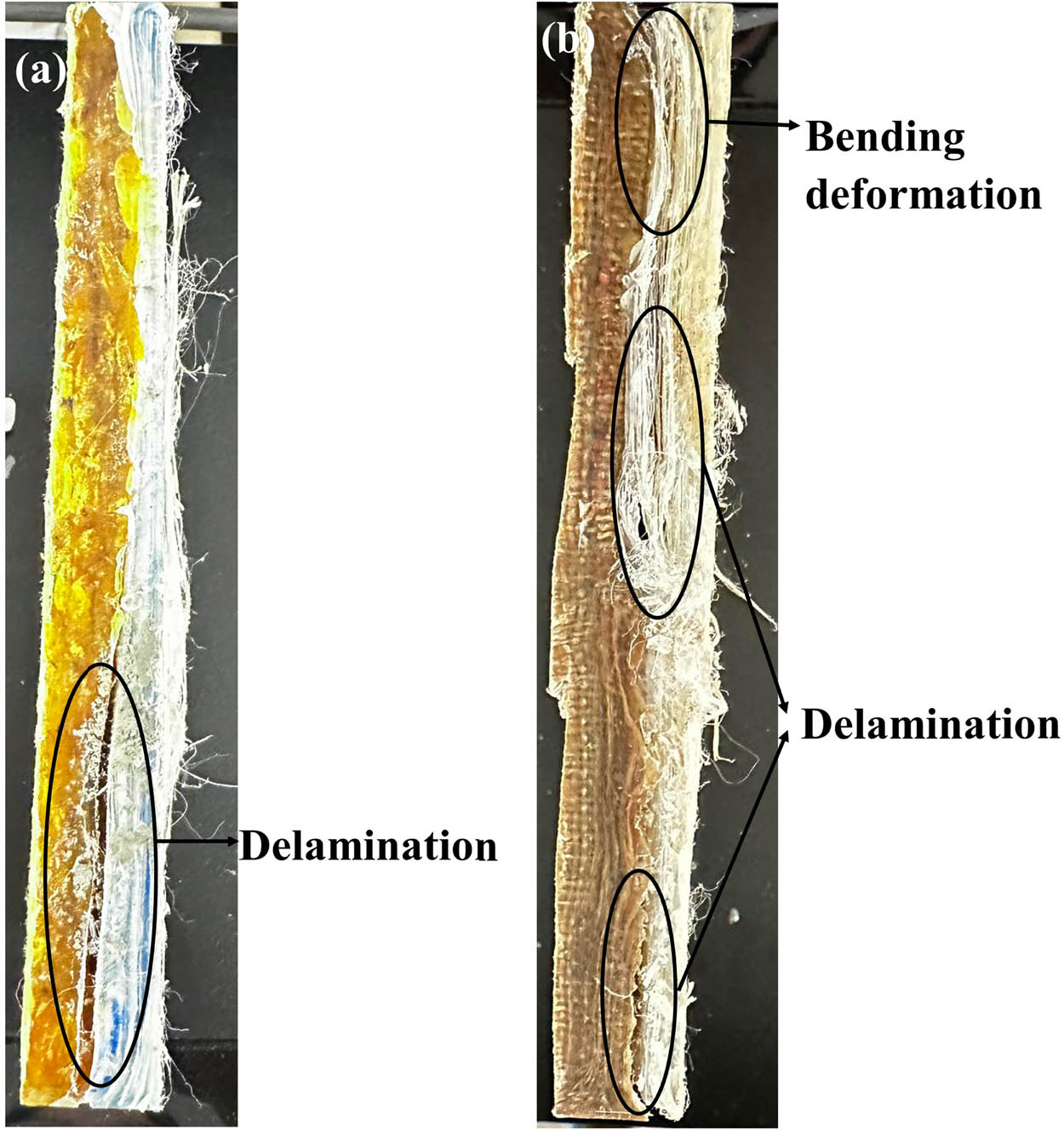

Table 3 presents the results of impact velocity, residual velocity, energy absorption, and backface signature. Both composite plate samples demonstrate excellent projectile protection, with the bullet unable to penetrate the target. This suggests that the naturally reinforced composite effectively absorbs the projectile’s kinetic energy due to its remarkable hard and brittle properties, consistent with the findings of Hu et al. [34]. The energy absorption of the hemp woven composite slightly exceeds that of the cocoon waste composite, a trend supported by the result shown in Figure 6(b), indicating delamination and bending deformation, which contribute to the high absorbed kinetic energy of the projectile [2]. Additionally, residual kinetic energy is completely absorbed by UHMWPE. The BFS results of both composite plate samples are below 44 mm, meeting the standard set by the U.S. National Institute of Justice (NIJ) standard 0101.06 [35]. However, the BFS values of the cocoon waste composite and hemp woven composite differ slightly. The cocoon waste composite has a BFS of 21.25 mm, while the hemp woven composite has a BFS of 27.53 mm, as shown in Table 3. This composite plate consists of two layers: the first layer is natural fiber waste reinforced with epoxy resin, capable of absorbing significant energy and reducing the velocity of projectile impact, aligning with Drodge et al. [36]. The second layer is the UHMWPE layer, approximately 5 mm thick, which absorbs the residual energy of the projectile and provides a higher ballistic limit. Figure 6 illustrates the delamination phenomenon occurring in both composite plates, which is the predominant failure mode, initiated by the projectile’s compressive load at the impact point, leading to continuous stress that affects the debonding and fracture of UHMWPE fiber, consistent with the previous study by Suriani et al. [37]. The penetration process involves four steps. First, the projectile hits the composite plate, causing matrix cracking at the impact point. Second, the impact load from the bullet destroys the fiber bonding and causes breakage. Third, the composite absorbs the kinetic energy of the bullet, deforming its tip. Finally, the residual kinetic energy of the bullet is fully absorbed. The UHMWPE layer bulges and is not fully penetrated.

Parameters and backface signature (BFS) results after impact test

| Composite plate sample | Impact velocity (m/s) | Residual velocity (m/s) | Energy absorption (J) | Backface signature (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite | 446.87 ± 2.03 | Unpenetrated | 798.77 ± 7.28 | 21.25 ± 0.68 |

| Hybrid hemp woven-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite | 448.94 ± 2.00 | Unpenetrated | 806.19 ± 7.18 | 27.53 ± 1.47 |

The deformation of composite plate samples after the impact test: (a) hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite and (b) hybrid hemp woven-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite.

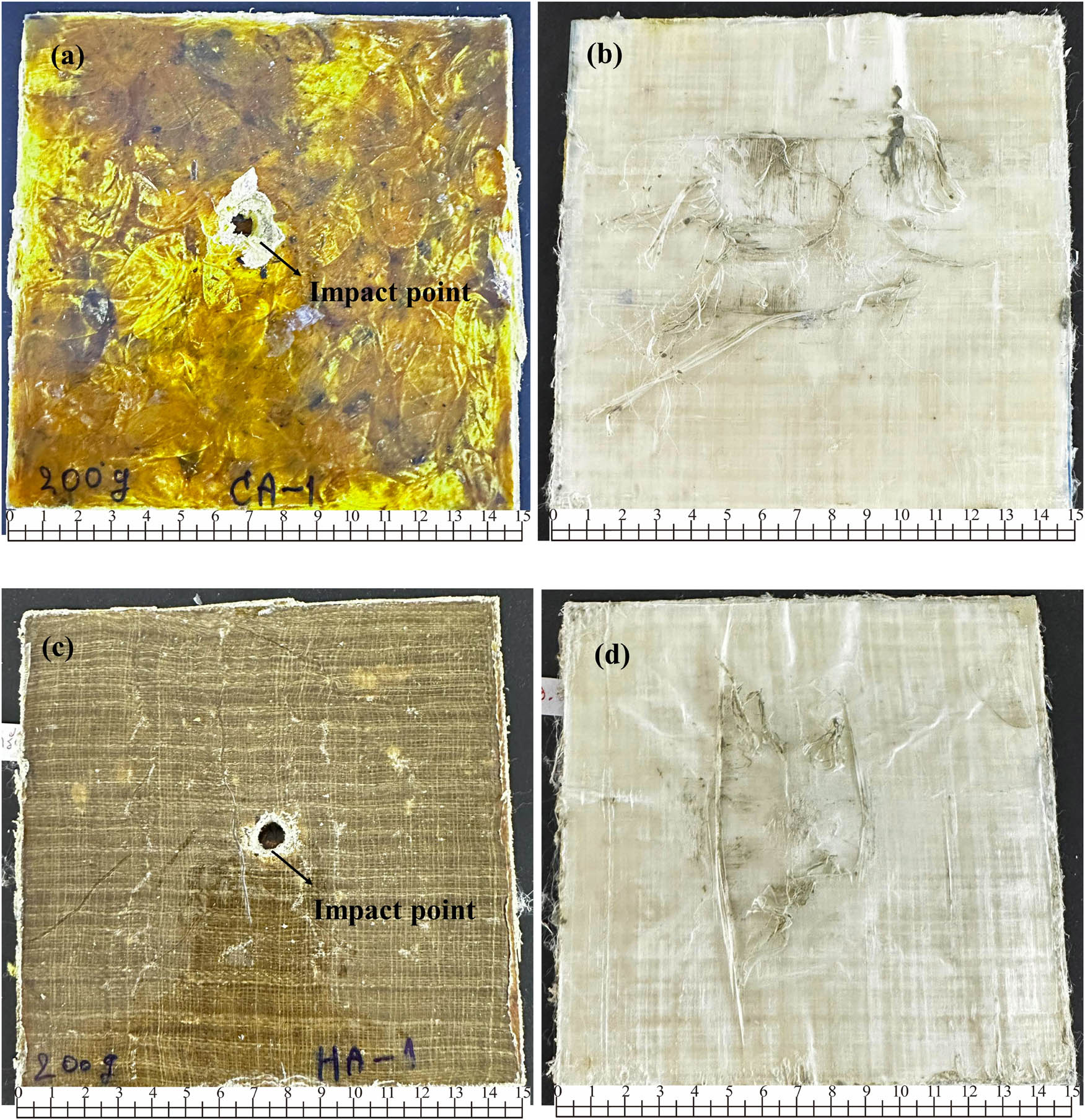

After the projectile attacked the composite plate samples, as illustrated in Figure 7, the results suggested that both composite plates effectively prevented further penetration. The projectile was stopped at the UHMWPE layer, as reported by Alkhatib et al. [38]. Figure 7(a) and (c) depicts full penetration without radial cracks, due to the inherently brittle epoxy resin and the toughness of both silkworm cocoon waste and hemp woven. Moreover, the robust interactions among silkworm cocoon waste, hemp woven, and the matrix contributed to a reduction in bullet velocity and substantial absorption of kinetic energy, resulting in relatively smooth damage at the impact point. However, the impact point hole of the cocoon waste composite exhibited more splaying compared to the hemp woven composite, attributed to the absence of weave in the silkworm cocoon waste, resulting in a rough and highly porous surface. In conclusion, both cocoon waste composite and hemp woven composite demonstrated effective performance as armor against projectile impacts. In Figure 7(b) and (d), bulges originating from the UHMWPE layer are visible in both composite plates, displaying pyramid-like deformation. Following the projectile’s penetration through the first layer, the UHMWPE layer fully absorbs the residual velocity. UHMWPE exhibits outstanding performance in both ballistic and projectile defense due to its high modulus and lower density [39].

The image of composite plate samples after the impact test: (a) strike face of cocoon waste composite and (b) rear face of cocoon waste composite, (c) strike face of hemp woven composite, and (d) rear face of hemp woven composite.

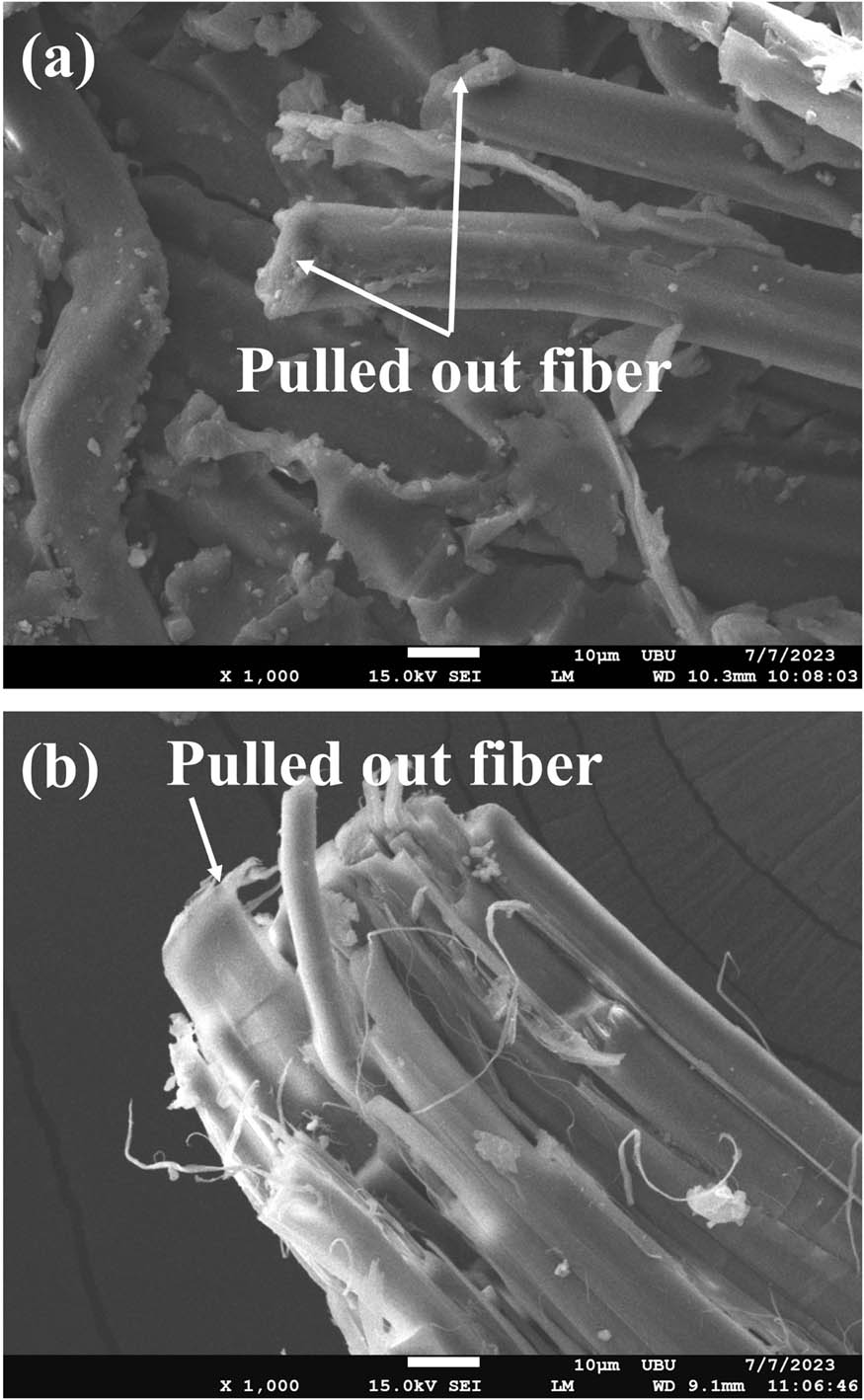

The SEM image depicting the fracture of natural fibers at the impact point is shown in Figure 8. Fiber pull-out is observed in both composite plates. In Figure 8(a), the fracture pattern of the cocoon waste composite shows its rough surface, which encourages excellent adherence with the matrix and suggests the absence of bending deformation, thus enhancing the absorption of the projectile’s kinetic energy. Conversely, Figure 8(b) displays the smooth surface of hemp fiber due to its tightly woven structure, incorporated with hydrophilic properties resulting weak interactions with the matrix. Bending deformation is visible in Figure 6(b). The distribution of both the matrix and cocoon waste fiber in the cocoon waste composites appears non-uniform across the epoxy resin surface, aligning with findings from Anidha et al. [7] and Yang et al. [40]. The interfacial connection between cocoon waste fiber and the epoxy resin matrix significantly influences the mechanical properties of the reinforced composite. Comprising fibroin fiber with a semicrystalline microstructure, the cocoon waste acts as a protein adhesive, enabling interfacial bonding with the matrix via hydrogen bonds [41]. This robust interfacial bonding greatly contributes to the strength of the closed-pack cocoon waste composite [42,43]. Consequently, both composite plate samples demonstrate effective performance in projectile protection, offering reduced cost, lightweight construction at 380 g per plate, and eco-friendliness through the utilization of cocoon waste and hemp woven from fabric production.

Fracture of natural fiber at the impact point: (a) silkworm cocoon waste of cocoon waste composite and (b) hemp woven of hemp woven composite.

4 Conclusion

Composite plates were successfully manufactured using the cold pressing process, selected for their cost-effectiveness, simplicity, and adherence to sustainable manufacturing principles. Cocoon waste served a critical function as a reinforcement component in these composites. The fabrication process entailed mixing silkworm cocoon waste with epoxy resin and UHMWPE, followed by cold compression molding. Tensile and impact tests were subsequently conducted on the resulting samples, utilizing a standardized 9 mm projectile. The experiments yielded a tensile strength of 107.4 MPa and an elastic modulus of 1240.3 MPa.

The impact test results unequivocally highlight the remarkable projectile protection capabilities of both composite plate samples. The cocoon waste composite, leveraging the inherent strength and brittleness of its components, along with matrix interactions, effectively absorbed the kinetic energy of the projectile, echoing findings from previous studies. Conversely, the hemp woven composite, while demonstrating slightly superior energy absorption, also exhibited the interplay between delamination and bending deformation, leading to efficient kinetic energy dissipation. These results align closely with established standards for ballistic protection, as evidenced by the measured BFS values, all well below the U.S. NIJ standard 0101.06 of 44 mm. Despite their differences, the BFS values of the cocoon waste composite and hemp woven composite reflected their specific characteristics, with the former at 21.25 mm and the latter at 27.53 mm. Delamination emerged as a prominent failure mode in both composite plates, where continuous stress from the projectile’s compressive load triggers debonding and fracture of UHMWPE fibers. These findings collectively demonstrated that both the cocoon waste composite and the hemp woven composite offer promising and effective solutions for projectile protection. This research represents a crucial step toward the development of innovative, sustainable, and cost-effective materials for enhanced ballistic defense across various applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Faculty of Engineering, Khon Kaen University.

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by the Research Fund for Supporting Lecturers to Admit High Potential Students to Study and Research on His Expert Program Year 2017, Graduate School, Khon Kaen University.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that no potential conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data used to support the findings of this study are included in this article.

References

[1] Shen C, Liu L, Cai X, Zhang F, Chen W, Ma Y. Investigation on the anti-penetration performance of the steel/nylon sandwich plate. Sci Eng Compos Mater. 2021;28(1):128–38.10.1515/secm-2021-0013Search in Google Scholar

[2] Wambua P, Vangrimde B, Lomov S, Verpoest I. The response of natural fibre composites to ballistic impact by fragment simulating projectiles. Compos Struct. 2007;77(2):232–40.10.1016/j.compstruct.2005.07.006Search in Google Scholar

[3] Page J, Sonebi M, Amziane S. Design and multi-physical properties of a new hybrid hemp-flax composite material. Constr Build Mater. 2017;139:502–12.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.12.037Search in Google Scholar

[4] Sowmya C, Ramesh V, Karibasavaraja D. An experimental investigation of new hybrid composite material using hemp and jute fibres and its mechanical properties through finite element method. Mater Today: Proc. 2018;5(5):13309–20.10.1016/j.matpr.2018.02.323Search in Google Scholar

[5] Merotte J, Le Duigou A, Kervoelen A, Bourmaud A, Behlouli K, Sire O, et al. Flax and hemp nonwoven composites: The contribution of interfacial bonding to improving tensile properties. Polym Test. 2018;66:303–11.10.1016/j.polymertesting.2018.01.019Search in Google Scholar

[6] Gupta NV, Rao KS. An experimental study on sisal/hemp fiber reinforced hybrid composites. Mater Today: Proc. 2018;5(2):7383–7.10.1016/j.matpr.2017.11.408Search in Google Scholar

[7] Anidha S, Latha N, Muthukkumar M. Reinforcement of aramid fiber with bagasse epoxy bio-degradable composite: Investigations on mechanical properties and surface morphology. J Mater Res Technol. 2019;8(3):3198–212.10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.05.008Search in Google Scholar

[8] Helaili S, Chafra M, Chevalier Y. Natural fiber alfa/epoxy randomly reinforced composite mechanical properties identification. Structures. 2021;34(12):542–9.10.1016/j.istruc.2021.07.095Search in Google Scholar

[9] de Assis FS, Pereira AC, da Costa Garcia Filho F, Lima EP, Monteiro SN, Weber RP. Performance of jute non-woven mat reinforced polyester matrix composite in multilayered armor. J Mater Res Technol. 2018;7(4):535–40.10.1016/j.jmrt.2018.05.026Search in Google Scholar

[10] Braga FDO, Milanezi TL, Monteiro SN, Louro LHL, Gomes AV, Lima EP. Ballistic comparison between epoxy-ramie and epoxy-aramid composites in Multilayered Armor Systems. J Mater Res Technol. 2018;7:541–9.10.1016/j.jmrt.2018.06.018Search in Google Scholar

[11] Akubue PC, Igbokwe PK, Nwabanne JT. Production of kenaf fibre reinforced polyethylene composite for ballistic protection. Int J Sci Eng Res. 2015;6(8):1–7.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Monteiro SN, Milanezi TL, Louro LHL, Lima EP, Braga FO, Gomes AV, et al. Novel ballistic ramie fabric composite competing with KevlarTM fabric in multilayered armor. Mater Des. 2016;96:263–9.10.1016/j.matdes.2016.02.024Search in Google Scholar

[13] Monteiro SN, Braga FO, Lima EP, Louro LHL, Drelich JW. Promising curaua fiber-reinforced polyester composite for high-impact ballistic multilayered armor. Polym Eng Sci. 2017;57(9):947–54.10.1002/pen.24471Search in Google Scholar

[14] Rohen LA, Margem FM, Monteiro SN, Vieira CMF, Araujo BM, Lima ES. Ballistic efficiency of an individual epoxy composite reinforced with sisal fibers in multilayered armor. Mater Res. 2015;18:55–62.10.1590/1516-1439.346314Search in Google Scholar

[15] Da Cruz RB, Junior EPL, Monteiro SN, Louro LHL. Giant bamboo fiber reinforced epoxy composite in multilayered ballistic armor. Mater Res. 2015;18:70–5.10.1590/1516-1439.347514Search in Google Scholar

[16] Sashina ES, Yakovleva OI. The current state and prospects of recycling silk industry waste into nonwoven materials. Fibers. 2023;11:56.10.3390/fib11060056Search in Google Scholar

[17] Li F, Tan Y, Chen L, Jing L, Wu D, Wang T. High fibre-volume silkworm cocoon composites with strong structure bonded by polyurethane elastomer for high toughness. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2019;125:105553.10.1016/j.compositesa.2019.105553Search in Google Scholar

[18] Han SO, Lee SM, Park WH, Cho D. Mechanical and thermal properties of waste silk fiber-reinforced poly(butylene succinate) biocomposites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2006;100:4972–80.10.1002/app.23300Search in Google Scholar

[19] Pickering KL, Efendy MGA, Le TM. A review of recent developments in natural fibre composites and their mechanical performance. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2016;83:98–112.10.1016/j.compositesa.2015.08.038Search in Google Scholar

[20] Karimah A, Ridho MR, Munawar SS, Adi DS, Ismadi, Damayanti R, et al. A review on natural fibers for development of eco-friendly bio-composite: characteristics, and utilizations. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;13:2442–58.10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.06.014Search in Google Scholar

[21] Loh K, Tan W. Natural silkworm-epoxy resin composite for high performance application. Metal Ceram Polym Compos Var Uses. 2011 Jul;325–40.10.5772/22338Search in Google Scholar

[22] Tanguy M, Bourmaud A, Beaugrand J, Gaudry T, Baley C. Polypropylene reinforcement with flax or jute fibre; Influence of microstructure and constituents properties on the performance of composite. Compos B Eng. 2018;139:64–74.10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.11.061Search in Google Scholar

[23] Jarupong J, Artnaseaw A, Sasrimuang S. Cocoon waste reinforced in epoxy matrix composite: Investigation on tensile properties and surface morphology. Eng Appl Sci Res. 2023;50:597–604.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Chen F, Liu X, Yang H, Dong B, Zhou Y, Chen D, et al. A simple one-step approach to fabrication of highly hydrophobic silk fabrics. Appl Surf Sci. 2016;360:207–12.10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.10.186Search in Google Scholar

[25] Shah DU. Developing plant fibre composites for structural applications by optimising composite parameters: A critical review. J Mater Sci. 2013;48:6083–107.10.1007/s10853-013-7458-7Search in Google Scholar

[26] Shelly D, Lee S-Y, Park S-J. Compatibilization of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) fibers and their composites for superior mechanical performance: A concise review. Compos B Eng. 2024;275:111294.10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.111294Search in Google Scholar

[27] Faruk O, Yang Y, Zhang J, Yu J, Lv J, Lv W, et al. A comprehensive review of ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene fibers for applications based on their different preparation techniques. Adv Polym Technol. 2023;2023:6656692.10.1155/2023/6656692Search in Google Scholar

[28] Shubhra QTH, Alam AKMM, Khan MA, Saha M, Saha D, Gafur MA, et al. Study on the mechanical properties, environmental effect, degradation characteristics and ionizing radiation effect on silk reinforced polypropylene/natural rubber composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2010;41(11):1587–96.10.1016/j.compositesa.2010.07.007Search in Google Scholar

[29] Lee SM, Cho D, Park WH, Lee SG, Han SO, Drzal LT. Novel silk/poly(butylene succinate) biocomposites: the effect of short fibre content on their mechanical and thermal properties. Compos Sci Technol. 2005;65(3–4):647–57.10.1016/j.compscitech.2004.09.023Search in Google Scholar

[30] Priya SP, Ramakrishna HV, Rai KS. Utilization of waste silk fabric as reinforcement in epoxy phenol cashew nut shell liquid toughened epoxy resin: Studies on mechanical properties. J Compos Mater. 2006;40(14):1301–11.10.1177/0021998306059727Search in Google Scholar

[31] Chen S, Cheng L, Huang H, Zou F, Zhao HP. Fabrication and properties of poly(butylene succinate) biocomposites reinforced by waste silkworm silk fabric. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2017;95:125–31.10.1016/j.compositesa.2017.01.004Search in Google Scholar

[32] Xu H, Zhang X, Yu Y, Yu Y, Weng L. Enhanced adhesion property of epoxy resin composites through dual reinforcement mechanisms. Mater. 2024;3:100072.10.1016/j.nxmate.2023.100072Search in Google Scholar

[33] Morin A, Alam P. Comparing the properties of Bombyx mori silk cocoons against sericin-fibroin regummed biocomposite sheets. Mater Sci Eng: C. 2016;65:215–20.10.1016/j.msec.2016.04.026Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Hu D, Zhang Y, Shen Z, Cai Q. Investigation on the ballistic behavior of mosaic SiC/UHMWPE composite armor systems. Ceram Int. 2017;43:10368–76.10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.05.071Search in Google Scholar

[35] NIJ Standard-0101.06. Ballistic Resistance of Personal Body Armor. U.S. Department of Justice; 2008 Jul.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Drodge DR, Mortimer B, Holland C, Siviour CR. Ballistic impact to access the high-rate behaviour of individual silk fibres. J Mech Phys Solids. 2012;60(10):1710–21.10.1016/j.jmps.2012.06.007Search in Google Scholar

[37] Suriani MJ, Rapi HZ, Ilyas RA, Petru M, Sapuan SM. Delamination and manufacturing defects in natural fiber-reinforced hybrid composite: A review. Polymers. 2021;13(8):1323.10.3390/polym13081323Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Alkhatib F, Mahdi E, Dean A. Design and evaluation of hybrid composite plates for ballistic protection: Experimental and numerical investigations. Polymers. 2021;13(9):1450.10.3390/polym13091450Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] López-Puente J, Arias A, Zaera R, Navarro C. The effect of the thickness of the adhesive layer on the ballistic limit of ceramic/metal armours. An experimental and numerical study. Int J Impact Eng. 2005;32(1–4):321–36.10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2005.07.014Search in Google Scholar

[40] Yang K, Ritchie RO, Gu Y, Wu SJ, Guan J. High volume-fraction silk fabric reinforcements can improve the key mechanical properties of epoxy resin composites. Mater & Des. 2016;108:470–8.10.1016/j.matdes.2016.06.128Search in Google Scholar

[41] Ho MP, Wang H, Lau KT, Lee JH, Hui D. Interfacial bonding and degumming effects on silk fibre/polymer biocomposites. Compos B Eng. 2012;43(7):2801–12.10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.04.042Search in Google Scholar

[42] Facca AG, Kortschot MT, Yan N. Predicting the tensile strength of natural fibre reinforced thermoplastics. Compos Sci Technol. 2007;67(11–12):2454–66.10.1016/j.compscitech.2006.12.018Search in Google Scholar

[43] Ho MP, Lau KT, Wang H, Bhattacharyya D. Characteristics of a silk fibre reinforced biodegradable plastic. Compos B Eng. 2011;42(2):117–22.10.1016/j.compositesb.2010.10.007Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective