Abstract

In this work, an Ag–Ti2SnC composite was fabricated by the hot-pressing sintering method, and the erosion behavior of Ag–Ti2SnC with volume percentages of 10–40% was studied at a load voltage of 10 kV. The arc life and breakdown current were observed at about 31–36 ms and 39 A, respectively. The cathode spot traveled the fastest on the surface of the Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC composite. Due to emission center model, the temperature of the minor protrusions on the cathode surface increased, resulting in Ag ions, Ti ions, and Sn ions being generated. Combining with the ionized oxygen, Ag2O, AgO, TiO2, and SnO2 were formed on the eroded Ag–Ti2SnC surface after arc erosion. The research results will broaden the application range of Ag–Ti2SnC electrical contact material and enrich the arc erosion mechanism.

1 Introduction

Satellite relays, rocket long-distance signal transmission, and circuit conversion essentially employ electrical contact materials. Arc erosion will degrade the material structure, reducing the service life of the material with considerable costs to the national economy. During arc combustion, the following features will be present: (1) The arc will travel on the material surface once it starts, where the higher the arc concentration and the harsher the erosion action on the material, the slower the motion speed. (2) The molten pool flow will accelerate through a combination of arc plasma force, static pressure, and other factors, resulting in splashing, pores, and bulges. The electrical contact material will repeat the molten pool creation, material splashing, material solidification, and pore formation processes after several arc erosion [1]. The electrical contact mechanical strength and conductivity of the material will be dramatically diminished, resulting in circuit breakdown, with a significant impact on signal transmission accuracy and efficacy. The microstructure of electrical contact materials will have an impact on arc combustion properties, and a good microstructure will accelerate arc movement and scatter the arc throughout the material surface. As a result, it is critical to choose the right electrical contact material.

By altering the preparation procedure, researchers have increased the arc erosion capabilities of materials. The contact materials prepared by internal oxidation exhibited fine and uniformly dispersed reinforcing phases, good reinforcing effect, excellent resistance to arc corrosion, and anti-melt welding [2,3,4]. However, oxygen diffusion was difficult to control, and the phenomenon of uneven oxidation was prone to occur. The improper selection of temperature during internal oxidation led to the inconsistency in oxide particle size and the decrease in electrical properties [5]. The powder metallurgy was commonly used in the fabrication of electrical contact materials. Compared with the internal oxidation and chemical coprecipitation methods [6], AgSnO2 materials prepared by powder metallurgy showed less arc erosion and a shorter arc life [6,7]. The powders, such as Ag and MAX/Ag and SnO2/Ag, CuO, and In2O3, were first mixed by ball milling for some time, then the mixture was cold-pressed into the green bodies under a certain pressure. Thereafter, the green bodies were sintered for some hours at a certain temperature with flowing Ar [8,9,10,11]. Prior to sintering, the powder mixture was also annealed to release milling stress [12]. Ag and ZnO powders were first formed by cold isostatic press, and then the bulk materials were prepared by hot isostatic pressing [13]. In addition, due to the low sintering temperature and fast speed, Ag–WC, AgSnO2, W–Cu–Ni electrical contact material via spark plasma sintering exhibited a high density and uniform structure [14,15,16]. AgZnO and Ag–Ti3SiC2 electrical contact material prepared by hot pressing sintering method also showed similar advantages [17,18]. Vacuum-assisted material extrusion was performed to eliminate matrix voids and improve the bonding quality of deposited layers by reducing heat loss and entrapped air during manufacturing [19,20,21]. The mechanical properties of the material obtained by vacuum-assisted material extrusion were improved compared with conventional methods, which may be introduced in the fabrication of electrical contact materials.

Adding additives and changing the distribution of additive CuO can greatly reduce the arc erosion of AgSnO2 materials [12], which was another means to improve the material performance. Furthermore, adding Bi2O3, Y, or NiO was shown to improve the electrical contact properties of AgSnO2 materials [4,22,23]. The physical properties of AgSnO2Bi2O3 electrical contact materials can be improved through a combination of the melting atomization method and in situ reaction [24]. The addition of Ni was found to improve the arc erosion performance and dielectric strength of AgTiB2 and CuCr materials, respectively [25]. After adding graphite to a CuW alloy, the arc was found to originally occur on the Cu-specific crystal orientation transferred to graphite, which greatly enhanced the arc erosion ability of the CuW alloy [26]. Carbon nanotubes have been shown to effectively promote arc dispersion in TiB2/Cu materials and greatly reduce the arc energy of TiB2/Cu materials [27]. Furthermore, an increase in W content can reduce the fusion welding force of Al2O3–Cu (Cr, w) materials and shorten the arc life [28]. However, additives can complicate the composition of electrical contact materials, making the preparation process difficult to control stably. Moreover, additives will increase the difficulty of material preparation and add to the production cost. Therefore, it is urgent to develop a new electrical contact material without additives.

MAX phase is a class of layered ternary compounds with unique metal and ceramic properties, where M corresponds to the early transition metal, A represents the A group element, and X represents carbon or nitrogen [29,30]. Compared with metals, MAX phase materials exhibit higher mechanical strength. The electrical and thermal conductivity of MAX phase are better than those of ceramics. In addition, the good mechanical processing performance of MAX phase materials is popular with researchers. Sun et al. claimed that the metal and MAX phase material did not diffuse or react at high temperatures without additives, proving that metal–MAX composites were suitable for electrical contact materials [8]. The typical representative of MAX is Ti2SnC material. The electrical resistivity of Ti2SnC material is 0.22 μΩ m. The temperature coefficient of resistivity is 0.0032 K−1, and the coefficient of linear thermal expansion is 10 × 10−6 K−1. The Young’s modulus is 228 GPa and the Vickers hardness is 3.5 GPa [29]. Recently, Zhou et al. calculated the interface energy of Ag and Ti2SnC using first principles based on density functional theory, it was expected to become a substitute for the new generation of electrical contact materials [31]. Therefore, it is feasible to choose Ti2SnC as the reinforcing phase of Ag matrix as the electrical contact material [8,32–34]. Our previous work showed that Ti3AlC2/Ti3SiC2 material could protect the Cu/Ag matrix [18,35,36].

In this work, Ag–(10–40 vol%) Ti2SnC composites were fabricated by the hot pressing sintering method, and the erosion behavior of the Ag–Ti2SnC contact material in an air atmosphere was systematically studied.

2 Materials and methods

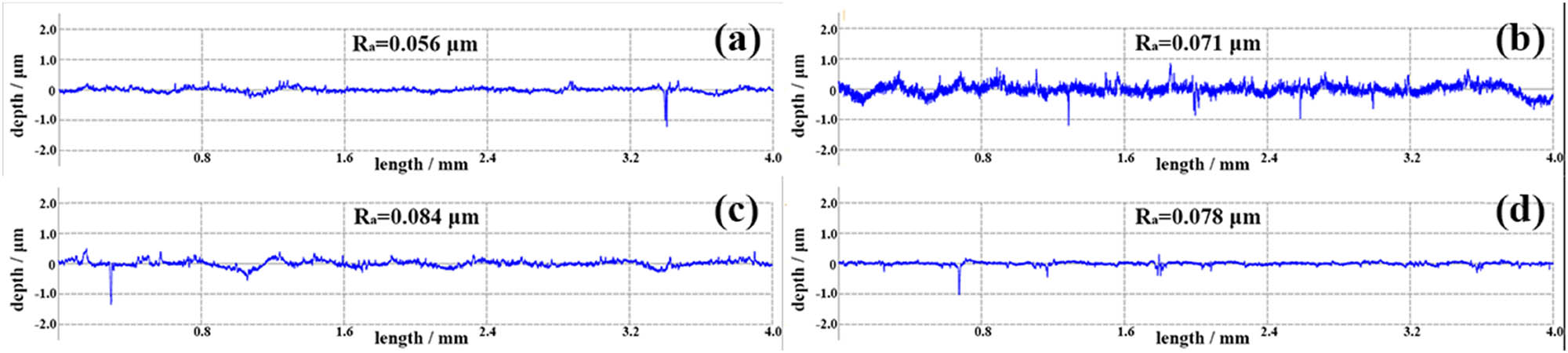

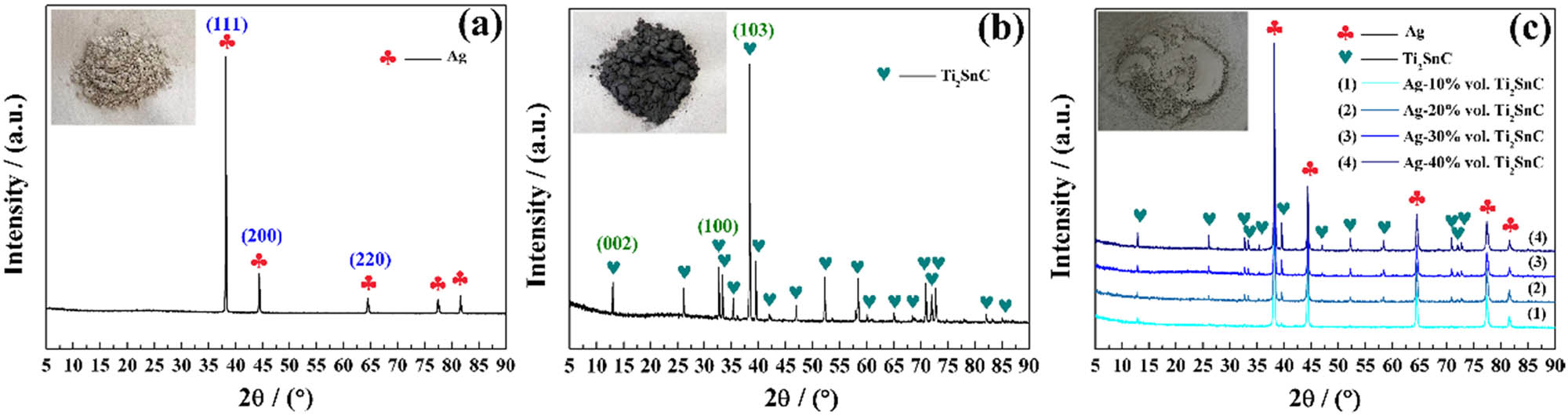

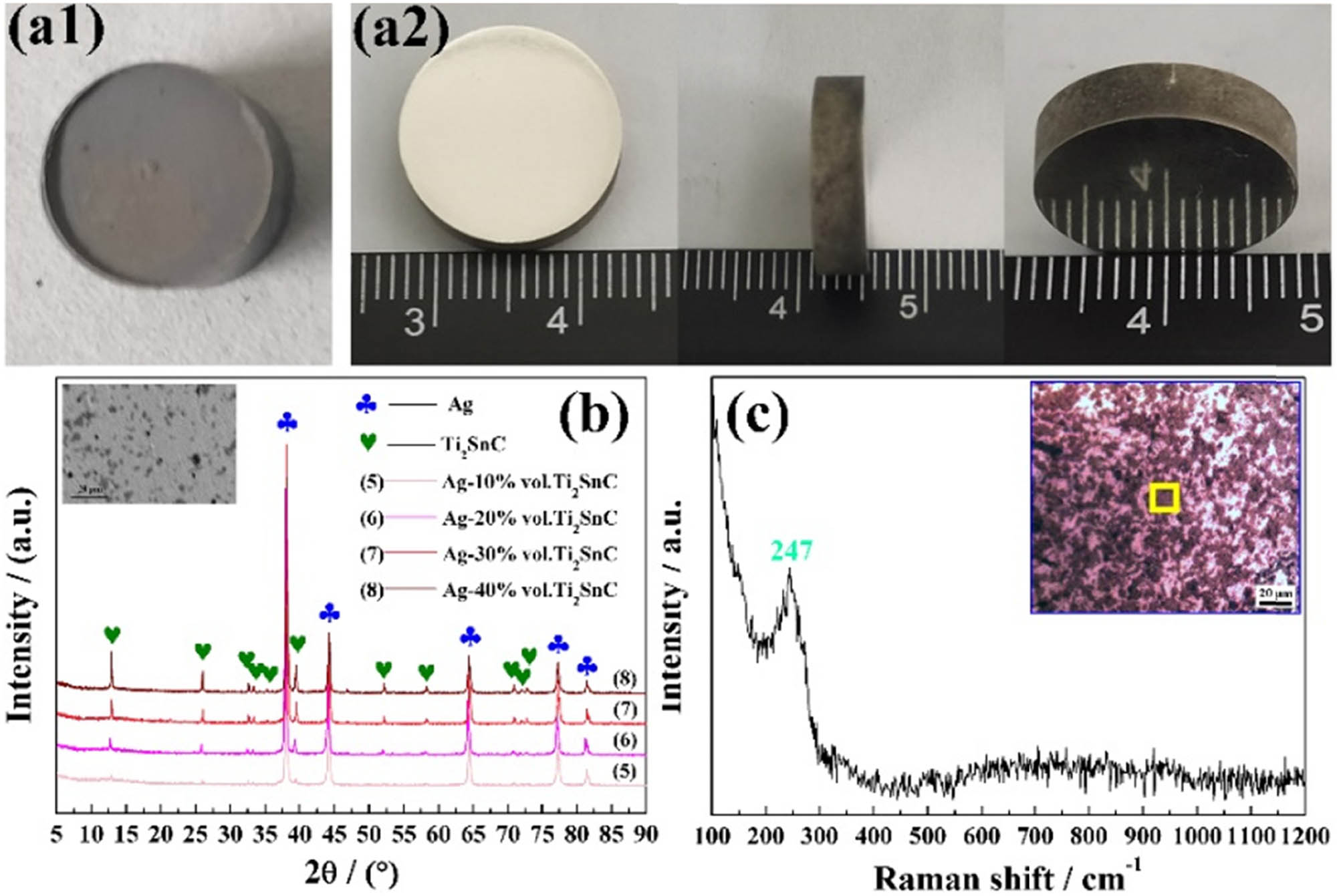

Ag powder (>99.9% purity, 200 mesh, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd) and Ti2SnC powder (>98%, 200 mesh, Laizhou Kai Kai Ceramic Materials Company Ltd) with different contents were first put into a sealed plastic bottle with a diameter of 80 mm and a height of 100 mm, and then the plastic bottle was placed and fixed inside a V-type mixing machine (VH5). The speed of the mixing machine containing the sealed plastic bottle was 120 rpm, maintaining for 2 h. The phases of the raw materials and the mixture were detected by X-ray diffraction (XRD, SmartLabSE, Japan) with Cu Ka radiation at 40 kV and 50 mA, as shown in Figure 2. The three-strong peaks ((111), (200), and (220)) of the Ag powder (JCPDF No. 87-0597) are labeled in Figure 2(a). The three strong peaks of the Ti2SnC powder (JCPDF No. 29-1353) were located at the crystal planes of (002), (100), and (103), as indicated in Figure 2(b). The peak intensity of the Ti2SnC of the mixture in Figure 2(c) increased with the increase in the Ti2SnC content, which was much weaker than the Ag phase. These results were consistent with the ratio of raw materials. Then, the mixture was placed into a high-strength graphite mold and coated with BN on the inner wall. The mold was placed inside the hot-pressing sintering furnace (ZT-40-20Y, Shanghai Chenhua Science Technology Corp., Ltd), and 30 MPa of pressure was applied. After drawing air in the furnace to 10−5 Pa, argon gas was injected into the furnace. Subsequently, the mold was heated to 700°C and held for 30 min. Finally, for the phase detection and arc erosion test, the bulk was polished to a mirror surface using abrasive paper, and an optical microscope was employed to record the surface morphologies of the polished samples. The arithmetical mean deviation of profile (R a) of polished Ag–Ti2SnC samples, measured via Surface roughness tester (MarSurf PS 10) is displayed in Figure 1, where the value of R a is less than 0.1 μm. The sintered density and relative density of Ag–Ti2SnC composite, via Archimedes method are listed in Table 1. The arc erosion test was carried out using self-made arc erosion equipment. During the test, the polished sample and W rod were chosen as the cathode and anode, respectively, where a load voltage of 10 kV was applied to the electrodes. For details on the arc erosion progress, see the study by Huang et al. [37]. After the arc erosion test, a high-resolution oscilloscope (ADS1102CAL) was used to record the test parameters. Three-dimensional laser scanning confocal microscopy (3D LSCM, VK-X1000) was carried out to analyze and reconstruct the characteristics after the arc erosion test. To compare the composition changes of the sample, Raman spectroscopy (Lab RAM-HR) was used to determine the composition before and after arc erosion testing. The compositional changes and microstructures of the samples were recorded by a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, SU8020) equipped with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS).

Curves of R a vs length of (a) Ag–10 vol% Ti2SnC, (b) Ag–20 vol% Ti2SnC, (c) Ag–30 vol% Ti2SnC, and (d) Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC.

The sintered density and relative density of Ag–Ti2SnC composite

| Ti2SnC content (vol%) | Sintered density (g/cm3) | Relative density (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 9.758 | 97.1 |

| 20 | 9.081 | 93.8 |

| 30 | 8.515 | 92.8 |

| 40 | 7.878 | 90.2 |

XRD patterns of (a) the Ag powder, (b) Ti2SnC powder, and (c) mixture of Ag with 10–40 vol% Ti2SnC powder.

3 Results

3.1 Microstructure of fabricated samples

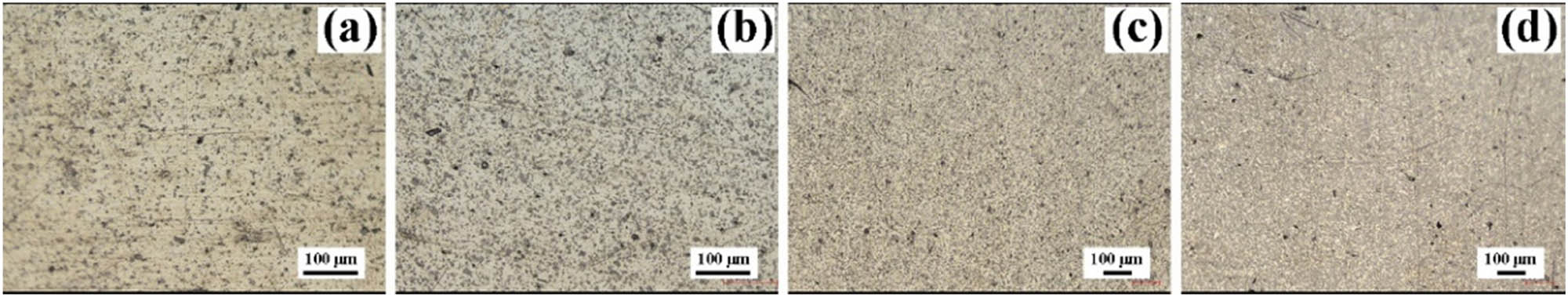

After sintering, the mixed powders turned to bulk, as shown in Figure 3(a1). As presented in Figure 3(a2), the sample had a mirror surface with a 15 mm diameter, and the height was about 3 mm. The XRD patterns of the samples (Ag–10–40 vol% Ti2SnC) are shown in Figure 3(b). We observed that no other phase was detected on the surface, indicating that the silver powder did not react with the Ti2SnC powder after sintering. From lines (5)–(8), the peak intensity of the Ti2SnC phase increased with the increase in the Ti2SnC content. The Raman spectroscopy results of the polished sample are shown in Figure 3(c), and the laser acted inside the yellow rectangle in the inset. The 247 cm−1 peak was labeled in the spectrum, which belonged to Ti2SnC [38], indicating that the gray phase was Ti2SnC. The optical micrographs of the Ag–Ti2SnC composite are displayed in Figure 4. The gray phases were evenly distributed on the surface, and we observed that with an increase in Ti2SnC content, the gray phase increased gradually.

(a1) The sintered block; (a2) the polished samples; (b) XRD pattern of the Ag–(10–40 vol%) Ti2SnC composite; and (c) Raman spectroscopy of the Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC composite.

Optical micrographs of (a) Ag–10 vol% Ti2SnC; (b) Ag–20 vol% Ti2SnC; (c) Ag–30 vol% Ti2SnC; and (d) Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC composite.

3.2 Arc parameters of eroded Ag–Ti2SnC cathodes

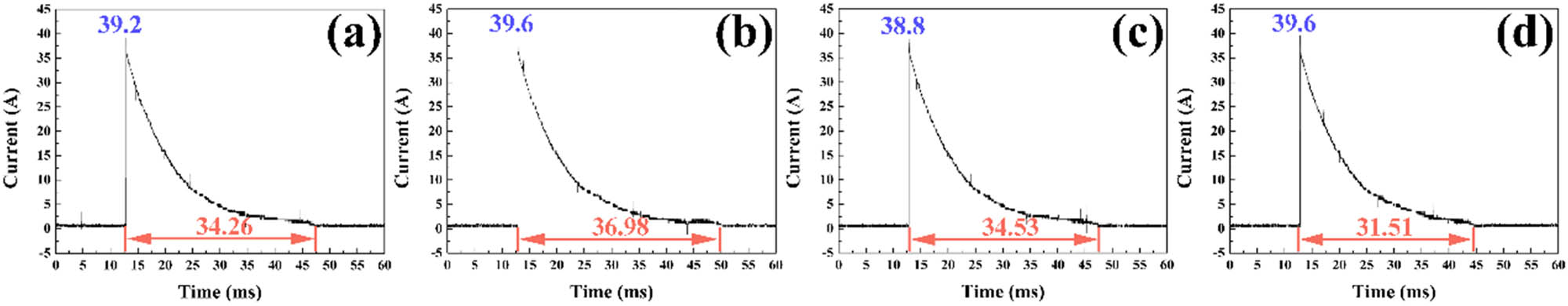

The current–time curves of the Ag–Ti2SnC composite are shown in Figure 5, where the vertical axis indicates the current value in the figure. Once an arc occurs, the current reaches the maximum first and is called the breakdown current. The breakdown current of the Ag–Ti2SnC composite was around 39 A with Ti2SnC content from 10 to 40 vol%. When the current value was close to zero, the arc was extinguished. The period from the beginning of arc erosion to extinction is called arc life. The values of arc life and breakdown current are displayed in Table 2. The arc life of the Ag–Ti2SnC composite remained about 31–36 ms. The arc energy was related to the arc life, breakdown current, and load voltage, which can be calculated using equation (1) [39].

Current–time curves at a load voltage of 10 kV for the Ag–Ti2SnC composite with Ti2SnC of (a) 10 vol%, (b) 20 vol%, (c) 30 vol%, and (d) 40 vol%.

Arc parameters of the Ag–Ti2SnC composite at a load voltage of 10 kV

| Ti2SnC content (vol%) | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 |

| Breakdown current (A) | 39.2 | 39.6 | 38.8 | 39.6 |

| Arc life (ms) | 34.26 | 36.98 | 34.53 | 31.51 |

| Arc energy (×103 J) | 13.430 | 14.644 | 13.398 | 12.478 |

where E is the arc energy (J), U is the load voltage (kV), I is the breakdown current (A), and t is the arc life (ms). The calculation results are listed in Table 2. The breakdown current of Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC was 39.6 A, which was much lower than Ag–40 vol% Ti3SiC2 (50.2 A) [18]. Similarly, the arc energy of the Ag–Ti2SnC composite was about 12–14 kJ, which was also lower than Ag–Ti3SiC2 at the same load voltage [18]. The electric current of AgZnO [13], AgSnO2 [11], AgCuO [40], AgCuOIn2O3SnO2 [10], AgWC30 [41], AgTiB2 [25], AgTiB2WO3 [42], Al2O3-Cu/(W, Cr) [28], and Ag–La2Sn2O7/SnO2 [43] ranged from 10 to 30 A. The arc voltage of those electrical contact materials varied from 12 to 4,500 V. The arc current and voltages used in the above materials were small, the arc energy was therefore far less than that of Ag–Ti2SnC material (12478 J-14644 J). However, due to the smaller arc energy for one arc erosion, the experiment was needed to be carried out tens of thousands of times [10,11,13,25,40–49]. That is why only one time arc erosion experiment was carried out here, where a single arc energy was sufficient to damage the surface of Ag–Ti2SnC electric contact material, and the surface morphology and composition could be analyzed.

3.3 Morphology and content on the eroded surface

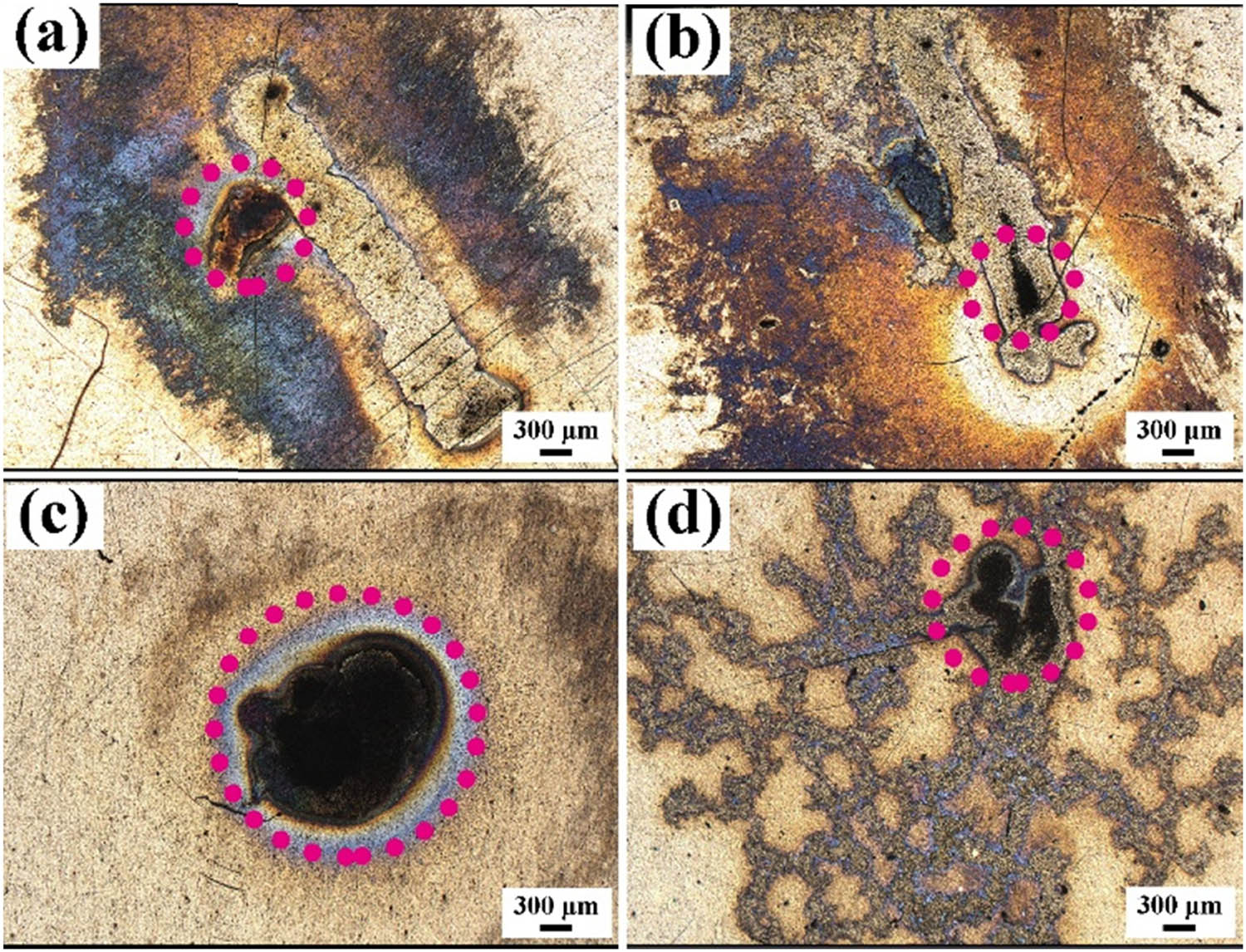

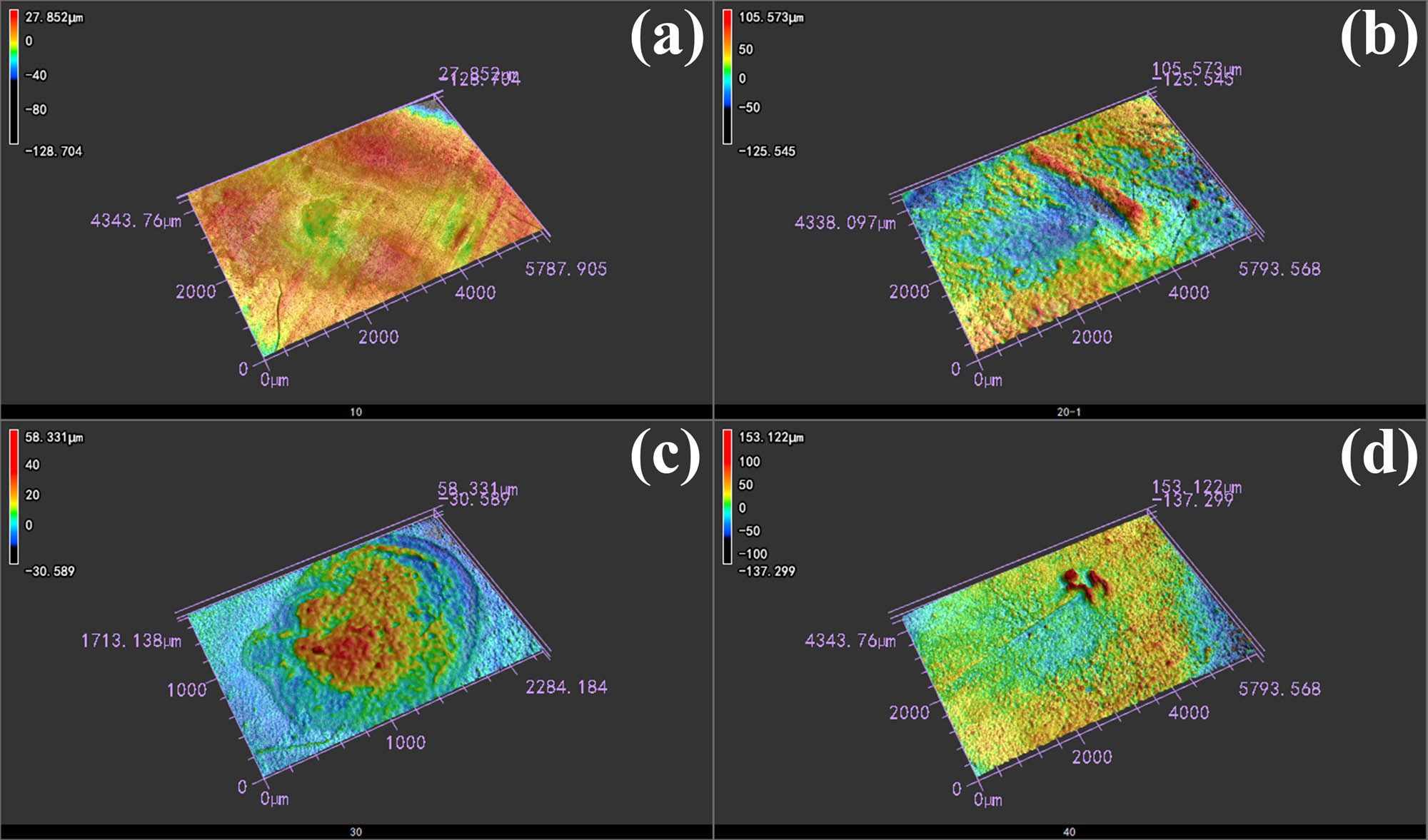

To observe the morphological characteristics after arc erosion, 3D LSCM was used to record the overall morphology and three-dimensional characteristics. The image shown in Figure 6 was obtained by the laser and color mode, and the eroded center areas are labeled by circles in the figure. With an increase in Ti2SnC content from 10–30 vol%, the erosion center area gradually became larger. As shown in Figure 6(a)–(c), the arc was concentrated at one point, forming a circle arc area on the surface. When the Ti2SnC content increased to 40 vol%, an interesting phenomenon occurred, and the arc area was no longer concentrated at one point. After the arc started at one point, as shown by the circle in Figure 6(d), it jumped on the Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC composite surface very fast. The arc life of the Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC composite was 31.51 ms, which was the shortest among the Ag–Ti2SnC composite. This phenomenon was consistent with the movement of the cathode spot, which will be further discussed in Section 4.3. The three-dimensional morphology is shown in Figure 7, and except for Figure 7(c), the morphology of the Ag–Ti2SnC composite after arc erosion was even without obvious bulges and pores. The arc concentrated at one point on the Ag–30 vol% Ti2SnC composite surface, causing the arc energy to concentrate at this point. When the arc was extinguished, numerous bulges and pores formed on the surface.

Micro-images of the eroded Ag–Ti2SnC with Ti2SnC content values of (a) 10 vol%, (b) 20 vol%, (c) 30 vol%, and (d) 40 vol% obtained in laser color mode using a three-dimensional laser scanning confocal microscope.

Three-dimensional morphology of eroded Ag–Ti2SnC with the Ti2SnC content of (a) 10 vol%, (b) 20 vol%, (c) 30 vol%, and (d) 40 vol%.

To determine the chemical composition change of the eroded Ag–Ti2SnC composite, the microstructure was further amplified by a SEM, as shown in Figure 8, where the morphologies in Figure 8(b) and (c) corresponded to the morphologies inside the same color rectangle in Figure 8(a). Many bulges formed on the eroded Ag–Ti2SnC composite surface, as indicated by the arrows in Figure 8(b) and (c), and microcracks are indicated by the circles in Figure 8(b) and (c). Spot scanning acted at point 1 in Figure 8(b), and the results are shown in Figure 8(d). After arc erosion, Ag, Ti, and Sn elements were detected on the eroded surface. Furthermore, N and O elements were found in the EDS results, indicating that oxides or nitrides were generated after the arc erosion test.

(a) SEM of Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC; (b) and (c) amplified images of (a); (d) the EDS result of point 1 in (b).

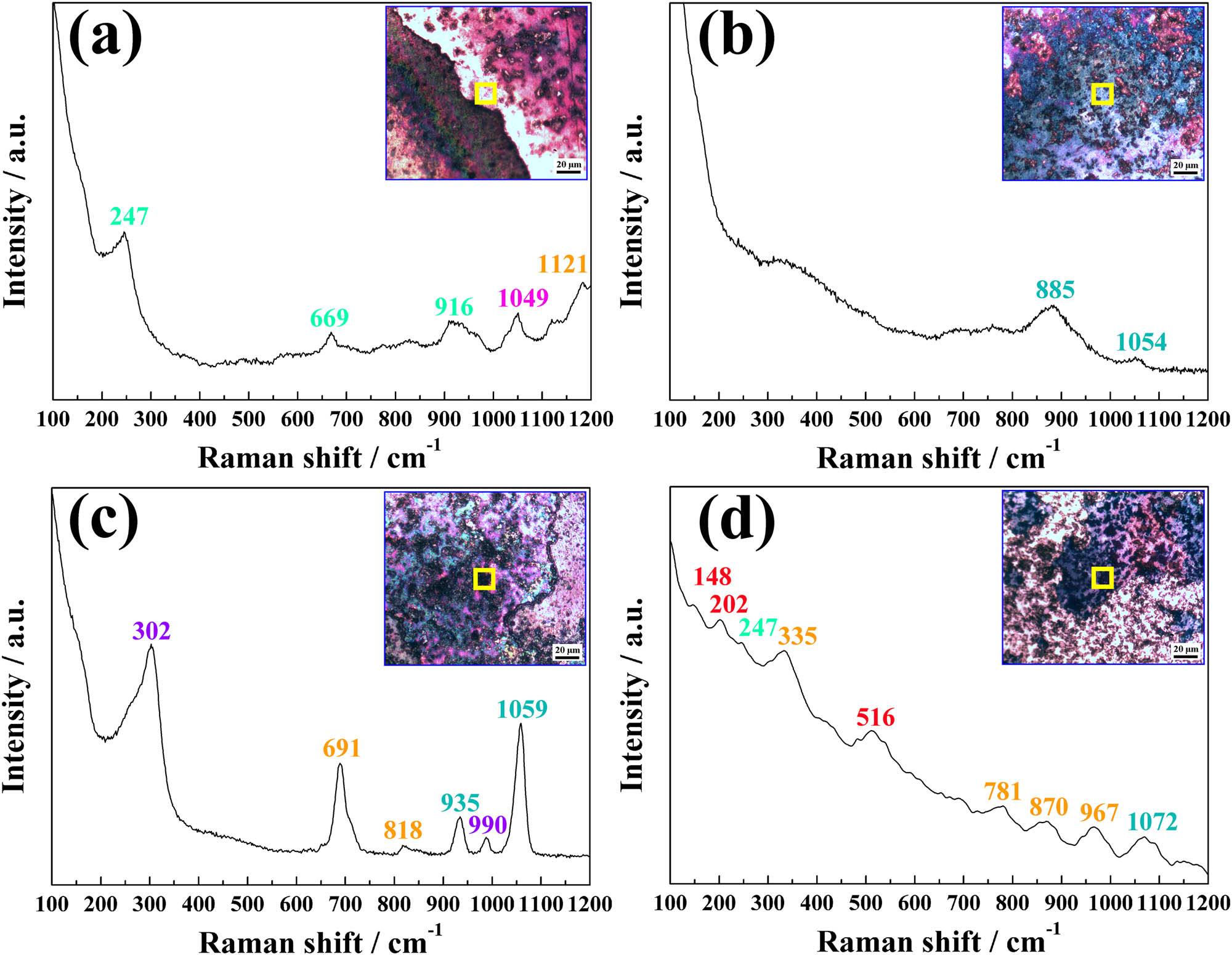

To further clarify the products after arc erosion, Raman spectroscopy was carried out on the eroded area. The results are presented in Figure 9, where the laser acted on the areas in the yellow rectangles inside the insets. At the edge of the erosion area in Figure 9(a), the peaks (247, 669, and 916 cm−1) of Ti2SnC were observed [38,50]. The peak at 1,049 cm−1 in the Raman shift belonged to the Ag element (R0070754), and the peak value of 1,121 cm−1 belonged to SnO2 (R040072). The results in Figure 9(a) indicated that a part of Ti2SnC decomposed and was oxidized at the eroded area. When the laser acted at the yellow rectangle in Figure 9(b), the peaks of 885 and 1,054 cm−1 were detected, which belonged to Ag2O [51]. Except for Ag2O (935 and 1,059 cm−1) [51,52], the peaks belonging to AgO (302 and 990 cm−1) [53,54] and SnO2 (691 and 818 cm−1, R050502 and R040017) were found in the Raman shift in Figure 9(c). As shown in Figure 9(d), the peaks at 148, 202, and 516 cm−1 were attributed to TiO2 (R050363, R120013, and R070582), and the peak at 247 cm−1 was assigned to Ti2SnC [38]. The four characteristic bands at 335, 781, 870, and 967 cm−1 were assigned to SnO2 (R050502, R040017, R050502, and R060563), and the 1,072 cm−1 peak belonged to Ag2O [52]. The Raman spectra in Figure 9 indicated that the Ag–Ti2SnC composite decomposed and oxidized to AgO, Ag2O, TiO2, and SnO2. No nitrides were detected on the eroded surface.

Raman spectra of the eroded Ag–Ti2SnC composite of (a) Ti2SnC and SnO2, (b) Ag2O, (c) AgO, Ag2O and SnO2, (d) TiO2, Ti2SnC, SnO2 and Ag2O.

4 Discussion

4.1 Generation of arc discharge

Gas discharge can be divided into non-self-sustained discharge and self-sustained discharge. When the current between the two electrodes was greater than a certain value, the gas conduction process itself could produce the charged particles needed to maintain conduction. This type of gas discharge only required additional measures to produce charged particles and induce ignition at the beginning. Once the discharge started, the additional measures were canceled, and the discharge process could continue. The discharge process itself could produce the charged particles required to maintain the discharge, which was called self-sustaining discharge [55]. The arc discharge belonged to the self-sustaining discharge and the arc discharge possessed the characteristics of lowest voltage, maximum current, highest temperature, and strongest luminescence. The charged particles that could maintain arc combustion consisted of electrons, positive ions, and negative ions. These particles were mainly produced by two physical processes, namely, gas ionization between the electrodes and electron emissions on the electrode surface. At the same time, this was accompanied by other processes such as dissociation, excitation, and recombination.

Although Ag–Ti2SnC composites were polished to a mirror face, the surface roughness of Ag–Ti2SnC is shown in Figure 1. It can be seen that the value of R a was less than 0.1 μm, meaning that there were still some minor protrusions existing on the cathode surface. According to the emission center model, the field strength at the micro protrusions on the cathode surface are very strong, and the heat generated by the field electron emission current in the area will increase the temperature at the micro protrusions. If the temperature is increased to a certain height, the field emissions will change into blasting electron emissions [56]. The minor protrusions existed on the cathode surface. When a load voltage of 10 kV was applied to the electrodes, the temperature of the minor protrusions increased. If the energy were to exceed the work function of the surface electrons, the electrons would escape from the surface. After electrons escaped, the Ag–Ti2SnC cathodes with lost electrons would become Ag ions, Ti ions, and Sn ions. The escaped electrons and these positive ions together formed a metal vapor. In 1971, Boddy and Utsumi first discovered that under atmospheric pressure, the arc combustion process was divided into two stages, namely, metallic phase and gaseous phase [57]. Thereafter, two main phases (metallic phase and gaseous phase) were proven to be present in the break arcs of resistive circuits spectroscopically [58]. In addition, the second gaseous phase is not present in vacuum arcs [58]. Since metal ions are eliminated in the process of inter-diffusion, the gas phase arc generated by ionization of the surrounding gas particles plays a greater part. The electrons on the cathode surface could also be emitted by light, an electric field, and particle collision [59]. Furthermore, the charged particles that sustained arc combustion were also ionized by gas. Under the action of an electric field between the two electrodes, the electrons moved toward the anode. During this process, the electrons collided with the atoms in the air, causing atoms to ionize into positive and negative ions, which was known as gaseous phase. In addition, the gas particles could be ionized by heat and light. The transition boundary from metallic to gaseous phase was closely related to arc voltage, air pressure, gas types, materials, and so on [60–62]. Kiyoshi Yoshida and Sunao Tanimoto experimentally studied the arc transition from metallic to gaseous phase in Ag, AgCu, and AgSnO2 [63,64]. The experiment was executed within the range of the source voltage from 12 to 48 V in air condition. They concluded that the gaseous phase arc transit was not caused in 24 V or less [65]. Here the arc voltage was 10 kV, which was much more than 24 V. In addition, arc erosion test was carried out under air condition. Therefore, the arc combustion process of Ag–Ti2SnC, specifically the plasma cloud, was formed by the combination of metal vapor and gas ionization. Considering the complexity of factors affecting arc transition from metallic to gaseous phase, it is necessary to further study the arc transition of Ag–Ti2SnC under air condition.

4.2 Movement of the cathode spot

During arc combustion, we observed a very bright plasma region with irregular movement on the cathode surface, which was called the cathode spots. These cathode spots were the center of emitting electrons, ions, metal vapor, and ejected droplets, which played a decisive role in the erosion of electrode materials and the continuity of current [56]. If a micro protrusion was completely consumed, the cathode spot would appear at the nearest neighboring protrusions until the arc was extinguished. When the content of Ti2SnC increased, the boundaries between Ag and Ti2SnC increased, resulting in the formation of more protrusions during the polishing process. Although the arc life was about 31–36 ms, the increase in protrusions on the surface of Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC could cause the cathode spots to move to a longer distance than Ag–30 vol% Ti2SnC. In the cathode spot area, molten pools formed, causing the Ag–Ti2SnC cathodes to melt and splash. Under the action of the Marangoni effect, bulge morphologies formed in Figure 8(b) and (c) [66]. When the arc was extinguished, the molten material solidified, and minor cracks and bulges formed on the surface.

4.3 Phase change after arc erosion

During arc combustion, Ag and Ti2SnC on the cathode surface decomposed into Ag ions, Ti ions, and Sn ions, and these ions combined with the O anions ionized in the air to form TiO2, SnO2, AgO, and Ag2O, as shown in Figures 8(d) and 9. Due to good wettability between Ag and SnO2 [32], SnO2 was likely the new starting point for cathode spot movement. Therefore, the movement range of the cathode spots on the material surface was the largest on the surface of Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC, resulting in the morphology shown in Figure 6(d).

5 Conclusion

Ag–Ti2SnC composite was fabricated by the hot-pressing sintering method. The erosion behavior of the Ag–Ti2SnC composite with varying contents of Ti2SnC was studied.

The breakdown current of Ag–Ti2SnC composite is around 39 A with the Ti2SnC content varying from 10 to 40 vol%, which is lower than that of Ti3SiC2 (52.6 A) material in our previous study. The arc energy of Ag–Ti2SnC composite is about 12–14 kJ, which is also lower than that of Ag–Ti3SiC2 at the same load voltage.

The arc concentrates at one point on Ag–(10–30)vol% Ti2SnC composite surface. The arc jumps on the Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC composite surface very fast. The arc life of Ag–40 vol% Ti2SnC composite is 31.51 ms, which is the shortest among the Ag–Ti2SnC composite.

The morphologies of bulges and pores are formed on the eroded surface of the Ag–Ti2SnC composite.

Metal oxides, such as Ag2O, AgO, TiO2, and SnO2 are detected on the surface.

During arc combustion, Ag and Ti2SnC on the cathode surface decomposed into Ag ions, Ti ions, and Sn ions. The arc combustion process of Ag–Ti2SnC was formed by the combination of metal vapor and gas ionization, which may be measured by spectrometric method systematically in the future.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (Grant Nos 2208085ME104 and 1908085QE218), the University Natural Science Research Project of Anhui Province (Grants Nos KJ2021ZD0141 and 2022AH051589), the National Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 52275467, 51905485, and 51971100), Cultivation Programme for the Outstanding Young Teachers of Anhui Province (YQYB2023054) and Anhui Province Key Laboratory of Coal Clean Conversion and High Valued Utilization, Anhui University of Technology (CHV19-05).

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (Grant Nos 2208085ME104 and 1908085QE218), the University Natural Science Research Project of Anhui Province (Grants Nos KJ2021ZD0141 and 2022AH051589), the National Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 52275467, 51905485, and 51971100), Cultivation Programme for the Outstanding Young Teachers of Anhui Province (YQYB2023054) and Anhui Province Key Laboratory of Coal Clean Conversion and High Valued Utilization, Anhui University of Technology (CHV19-05).

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Ding KK, Ding JX, Zhang KG, Chen LM, Ma CJ, Bai ZC, et al. Micro/nano-mechanical properties evolution and degradation mechanism of Ti3AlC2 ceramic reinforced Ag-based composites under high-temperature arc corrosion. Ceram Int. 2022;48(22):33670–81.10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.07.313Search in Google Scholar

[2] Xu CH, Yi DQ, Wu CP, Liu HQ, Li WZ. Microstructures and properties of silver-based contact material fabricated by hot extrusion of internal oxidized Ag–Sn–Sb alloy powders. Mater Sci Eng A. 2012;538:202–9.10.1016/j.msea.2012.01.031Search in Google Scholar

[3] Lutz O, Behrens V, Franz S, Honig T, Heinrich J, Aichele I, et al. Silver/tin oxide contact materials based on internal oxidation for AC and DC applications. VDE Fachberichte. 2009;167–76.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Zhou XL, Xiong AH, Liu MM, Zheng Z, Yu J, Wang LH. Electrical contact properties of AgSnO2NiO electrical contact material. Rare Met Mater Eng. 2019;48(9):2885–92.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Pedder DJ. The thermal stability of cadmium oxide in internally oxidized silver-cadmium alloys. Metall Trans A. 1978;9(5):659–70.10.1007/BF02659923Search in Google Scholar

[6] Wu CP, Zhao Q, Li NN, Wang HS, Yi DQ, Weng W. Influence of fabrication technology on arc erosion of Ag/10SnO2 electrical contact materials. J Alloy Compd. 2018;766:161–77.10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.06.317Search in Google Scholar

[7] Chen HY, Xu Q, Wang JH, Li P, Yuan JL, Lyu BH, et al. Effect of surface quality on hydrogen/helium irradiation behavior in tungsten. Nucl Eng Technol. 2022;54(6):1947–53.10.1016/j.net.2021.12.006Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ding JX, Tian WB, Wang DD, Zhang PG, Chen J, Zhang YM, et al. Corrosion and degradation mechanism of Ag/Ti3AlC2 composites under dynamic electric arc discharge. Corros Sci. 2019;156:147–60.10.1016/j.corsci.2019.05.005Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ding JX, Tian WB, Zhang PG, Zhang M, Zhang YM, Sun ZM. Arc erosion behavior of Ag/Ti3AlC2 electrical contact materials. J Alloy Compd. 2018;740:669–76.10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.01.015Search in Google Scholar

[10] Hu C, Zhou XL, Chen L, Liu MM, Wang LH. Effect of SnO2 additive on the electrical contact properties of AgCuOIn2O3 composites. Acta Materiae Compositae Sin. 2022;39(3):1322–31.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhang M, Wang XH, Yang XH, Zou JT, Liang SH. Arc erosion behaviors of AgSnO2 contact materials prepared with different SnO2 particle sizes. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China. 2016;26:783–90.10.1016/S1003-6326(16)64168-7Search in Google Scholar

[12] Wang J, Kang YQ, Wang C, Wang JB, Fu C. Resistance to arc erosion characteristics of CuO skeleton-reinforced Ag-CuO contact materials. J Alloy Compd. 2018;756:202–7.10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.05.018Search in Google Scholar

[13] Li AK, Nie BX, Xie M, Wang S, Chen Y, Zhu YF, et al. Microstructure and property research on AgZnO electrical contact materials prepared by hot isostatic pressing Precious. Metals. 2018;39(51):14–20.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ray N, Kempf B, Wiehl G, Mützel T, Heringhaus F, Froyen L, et al. Novel processing of Ag-WC electrical contact materials using spark plasma sintering. Mater Des. 2017;121:262–71.10.1016/j.matdes.2017.02.070Search in Google Scholar

[15] Xiong QF, Wang S, Xie M, Chen YT, Zhang JM, Wang SB. AgSnO2 electrical contact material prepared by spark plasma sintering. Precious Met. 2013;34(4):12–6.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Lungu M, Tsakiris V, Enescu E, Pătroi D, Marinescu V, Tălpeanu D, et al. Development of W-Cu-Ni electrical contact materials with enhanced mechanical properties by spark plasma sintering process. Acta Phys Polonica A. 2014;125:327–30.10.12693/APhysPolA.125.327Search in Google Scholar

[17] Guzmán D, Muñoz P, Aguilar C, Iturriza I, Lozada L, Rojas PA, et al. Synthesis of Ag–ZnO powders by means of a mechanochemical process. Appl Phys A. 2014;117(2):871–5.10.1007/s00339-014-8447-7Search in Google Scholar

[18] Huang XC, Feng Y, Ge JL, Li L, Li ZQ, Ding M. Arc erosion mechanism of Ag-Ti3SiC2 material. J Alloy Compd. 2020;817:152741.10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.152741Search in Google Scholar

[19] Cao D. Investigation into surface-coated continuous flax fiber-reinforced natural sandwich composites via vacuum-assisted material extrusion. Prog Addit Manuf. 2023. 10.1007/s40964-023-00508-6 Search in Google Scholar

[20] Cao D. Fusion joining of thermoplastic composites with a carbon fabric heating element modified by multiwalled carbon nanotube sheets. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2023;128(9):4443–53.10.1007/s00170-023-12202-6Search in Google Scholar

[21] Cao D, Bouzolin D, Lu H, Griffith DT. Bending and shear improvements in 3D-printed core sandwich composites through modification of resin uptake in the skin/core interphase region. Compos Part B: Eng. 2023;264:110912.10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110912Search in Google Scholar

[22] Wang HT, Wang LZ, Wang ZX. Physical and electrical contact properties of Ag-SnO2 contact materials doped with different particle size additives. Rare Met Mater Eng. 2019;48(2):458–62.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Wang JQ, Zhang Y, Kang HL. Study on properties of AgSnO2 contact materials doped with rare earth Y. Mater Res Express. 2018;5(8):085902.10.1088/2053-1591/aad24bSearch in Google Scholar

[24] Wu XH, Yang H, Qi GX, Zhang LJ, Shen T, Mu CF, et al. A study on preparation and properties of Ag/SnO2-Bi2O3 electrical contact materials via in-situ reaction method. Electr Mater. 2019;5:6–11.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Li HY, Wang XH, Xi Y, Zhu T, Guo XH. Effect of Ni addition on the arc erosion behavior of AgTiB2 contact material. Vacuum. 2019;161:361–70.10.1016/j.vacuum.2019.01.003Search in Google Scholar

[26] Chen QY, Liang SH, Wang F, Zhuo LC. Microstructural investigation after vacuum electrical breakdown of the W-30wt.%Cu contact material. Vacuum. 2018;149:256–61.10.1016/j.vacuum.2018.01.004Search in Google Scholar

[27] Long F, Guo XH, Song KX, Jia SG, Yakubov V, Li SL, et al. Enhanced arc erosion resistance of TiB2/Cu composites reinforced with the carbon nanotube network structure. Mater Des. 2019;183:108136.10.1016/j.matdes.2019.108136Search in Google Scholar

[28] Zhang XH, Zhang Y, Tian BH, An JC, Zhao Z, Volinsky AA, et al. Arc erosion behavior of the Al2O3-Cu/(W, Cr) electrical contacts. Compos Part B: Eng. 2019;160:110–8.10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.10.040Search in Google Scholar

[29] Sun ZM. Progress in research and development on MAX phases: a family of layered ternary compounds. Int Mater Rev. 2011;56(3):143–66.10.1179/1743280410Y.0000000001Search in Google Scholar

[30] Barsoum MW. The MN + 1AXN phases: A new class of solids: Thermodynamically stable nanolaminates. Prog Solid State Chem. 2000;28(1):201–81.10.1016/S0079-6786(00)00006-6Search in Google Scholar

[31] Nian Y, Zhang Z, Liu M, Zhou X. The electronic structure and stability of Ti2SnC/Ag interface studied by first-principles calculations. Adv Theory Simul. 2023;7:2300649.10.1002/adts.202300649Search in Google Scholar

[32] Ding JX, Tian WB, Zhang PG, Zhang M, Chen J, Zhang YM, et al. Preparation and arc erosion properties of Ag/Ti2SnC composites under electric arc discharging. J Adv Ceram. 2019;8(1):90–101.10.1007/s40145-018-0296-ySearch in Google Scholar

[33] Zhang M, Tian WB, Zhang PG, Ding JX, Zhang YM, Sun ZM. Microstructure and properties of Ag–Ti3SiC2 contact materials prepared by pressureless sintering. Int J Miner Metall Mater. 2018;25(7):810–6.10.1007/s12613-018-1629-0Search in Google Scholar

[34] Ding JX, Sun ZM, Zhang PG, Tian WB, Zhang YM. Current research status and outlook of Ag-based contact materials. Materials Reports. 2018;32(1):58–66.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Huang XC, Feng Y, Qian G, Ge JL, Zhang XF, Wang CH. Comparison of electrical ablation properties between pantograph materials: Ti3AlC2 and Cu-Ti3AlC2. Rare Met Mater Eng. 2020;49(1):34–41.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Huang XC, Feng Y, Qian G, Zhao H, Song ZK, Zhang JC, et al. Arc corrosion behavior of Cu-Ti3AlC2 composites in air atmosphere. Sci China Technol Sci. 2018;61(4):551–7.10.1007/s11431-017-9166-3Search in Google Scholar

[37] Huang XC, Feng Y, Qian G, Zhou ZJ. Arc ablation properties of Ti3SiC2 material. Ceram Int. 2019;45(16):20297–306.10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.06.305Search in Google Scholar

[38] Bentzel GW, Naguib M, Lane NJ, Vogel SC, Presser V, Dubois S, et al. High-temperature neutron diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, and first-Principles calculations of Ti3SnC2 and Ti2SnC. J Am Ceram Soc. 2016;99(7):2233–42.10.1111/jace.14210Search in Google Scholar

[39] Kubo S, Kato K. Effect of arc discharge on the wear rate and wear mode transition of a copper-impregnated metallized carbon contact strip sliding against a copper disk. Tribol Int. 1999;32:367–78.10.1016/S0301-679X(99)00062-6Search in Google Scholar

[40] Chen SY, Wang J, Yuan Z, Wang Z, Du D. Microstructure and arc erosion behaviors of Ag-CuO contact material prepared by selective laser melting. J Alloy Compd. 2021;860:158494.10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.158494Search in Google Scholar

[41] Ren XL, Chen S, Li MY, Xie M, Chen JH, Wang SB, et al. Arc erosion characteristics of AgWC30 electrical contact material. Rare Met Mater Eng. 2017;46(11):3345–51.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Li HY, Wang XH, Xi Y, Liu YF, Guo XH. Influence of WO3 addition on the material transfer behavior of the AgTiB2 contact material. Mater & Des. 2017;121:85–91.10.1016/j.matdes.2017.02.059Search in Google Scholar

[43] Zhang LJ, Shen T, Shen QH, Zhang J, Chen L, Fan XP, et al. Anti-arc erosion properties of Ag-La2Sn2O7/SnO2 contacts. Rare Met Mater Eng. 2016;45(7):1664–8.10.1016/S1875-5372(16)30136-9Search in Google Scholar

[44] Wang XH, Yang H, Chen M, Zou JT, Liang SH. Fabrication and arc erosion behaviors of AgTiB2 contact materials. Powder Technol. 2014;256:20–4.10.1016/j.powtec.2014.01.068Search in Google Scholar

[45] Wang XH, Yang H, Liang SH, Liu MB, Liu QD. Effect of TiB2 particle size on erosion behavior of Ag-4wt% TiB2 composite. Rare Met Mater Eng. 2015;44(11):2612–7.10.1016/S1875-5372(16)60004-8Search in Google Scholar

[46] Li HY, Wang XH, Liu YF, Guo XH. Effect of strengthening phase on material transfer behavior of Ag-based contact materials under different voltages. Vacuum. 2017;135:55–65.10.1016/j.vacuum.2016.10.031Search in Google Scholar

[47] Li HY, Wang XH, Guo XH, Yang XH, Liang SH. Material transfer behavior of AgTiB2 and AgSnO2 electrical contact materials under different currents. Mater Des. 2017;114:139–48.10.1016/j.matdes.2016.10.056Search in Google Scholar

[48] Ding JX, Tian WB, Wang DD, Zhang PG, Chen J, Sun ZM. Arc erosion and degradation mechanism of Ag/Ti2AlC composite. Acta Metall Sin. 2019;55(5):627–37.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Wei ZJ, Zhang LJ, Yang H, Shen T, Chen L. Effect of preparing method of ZnO powders on electrical arc erosion behavior of Ag/ZnO electrical contact material. J Mater Res. 2016;31(4):468–79.10.1557/jmr.2016.20Search in Google Scholar

[50] Xie J, Wang XH, Zhou YC. Understanding formation mechanism of titanate nanowires through hydrothermal treatment of various Ti-containing precursors in basic solutions. J Mater Sci Technol. 2012;28(6):488–94.10.1016/S1005-0302(12)60087-5Search in Google Scholar

[51] Anjum M, Kumar R, Barakat MA. Visible light driven photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in wastewater and real sludge using ZnO–ZnS/Ag2O–Ag2S nanocomposite. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng. 2017;77:227–35.10.1016/j.jtice.2017.05.007Search in Google Scholar

[52] Martina I, Wiesinger R, Jembrih-Simburger D, Schreiner M. Micro-Raman characterization of silver corrosion products. Instrumet Setup Ref Database Raman Spectrosc. 2012;9:1–8.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Ravi Chandra Raju N, Jagadeesh Kumar K, Subrahmanyam A. Physical properties of silver oxide thin films by pulsed laser deposition: effect of oxygen pressure during growth. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2009;42(13):135411.10.1088/0022-3727/42/13/135411Search in Google Scholar

[54] Ravi Chandra Raju N, Jagadeesh Kumar K. Photodissociation effects on pulsed laser deposited silver oxide thin films: surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering. J Raman Spectrosc. 2011;42(7):1505–9.10.1002/jrs.2895Search in Google Scholar

[55] Jinji Y. Gas discharge. Beijng: Science Press; 1983.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Beilis II. State of the theory of vacuum arcs. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci. 2001;29(5):657–70.10.1109/27.964451Search in Google Scholar

[57] Boddy PJ, Utsumi T. Fluctuation of arc potential caused by metal‐vapor diffusion in arcs in air. J Appl Phys. 1971;42(9):3369–73.10.1063/1.1660739Search in Google Scholar

[58] Gray EW. Some spectroscopic observations of the two regions (metallic vapor and gaseous) in break arcs. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci. 1973;1(1):30–3.10.1109/TPS.1973.4316076Search in Google Scholar

[59] Hernqvist KG. Emission mechanism of cold-cathode arcs. Phys Rev. 1958;109(3):636–46.10.1103/PhysRev.109.636Search in Google Scholar

[60] Meunier JL, Drouet MG. Experimental study of the effect of gas pressure on arc cathode erosion and redeposition in He, Ar, and SF6 from vacuum to atmospheric pressure. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci. 1987;15(5):515–9.10.1109/TPS.1987.4316746Search in Google Scholar

[61] Drouet MG, Meunier JL. Influence of the background gas pressure on the expansion of the arc-cathode plasma. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci. 1985;13(5):285–7.10.1109/TPS.1985.4316421Search in Google Scholar

[62] Vinaricky E, Behrens V. Switching behavior of silver/graphite contact material in different atmospheres with regard to contact erosion. Proceedings of the Forty-Fourth IEEE Holm Conference on Electrical Contacts. Arlington, VA, USA; 1998. p. 292–300.10.1109/HOLM.1998.722458Search in Google Scholar

[63] Yoshida K, Takahashi A. Effects of air pressure on transition boundary from metallic to gaseous phase in W break arc. Electron Commun Jpn (Part II: Electron). 1992;75(11):71–80.10.1002/ecjb.4420751108Search in Google Scholar

[64] Vinaricky E, Behrens V, editors. Switching behavior of silver/graphite contact material in different atmospheres with regard to contact erosion. Proceedings of the Forty-Fourth IEEE Holm Conference on Electrical Contacts; 2002.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Yoshida K, Tanimoto S, editors. An experimental study of arc duration and transition from metallic to gaseous phase in Ag alloy break arc. Electrical Contacts – 2007 Proceedings of the 53rd IEEE Holm Conference on Electrical Contacts, 2007 16–19 Sept; 2007.10.1109/HOLM.2007.4318206Search in Google Scholar

[66] Huang XC, Feng Y, Qian G, Liu K. Erosion behavior of Ti3AlC2 cathode under atmosphere air arc. J Alloy Compd. 2017;727:419–27.10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.08.188Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective