Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

Abstract

In many infrastructural engineering techniques, a common challenge is how to control the continuous damage caused by the cracks of concrete slab/decks overlay under environmental impaction or vehicle load. It drives the development of a high-flowability hybrid polypropylene and steel fiber-reinforced concrete (HPSFC), which has peculiarities for the overlay construction. In this aspect, an experimental study of HPSFC was carried out considering the factors, the volume ratio of binder paste to aggregates (P/A ratio) varied from 0.48 to 0.60, and the polypropylene (PP) fiber content changed from 0.45 to 1.35 kg/m3 with a hybrid steel fiber at 0.8% volume fraction. The workability of fresh mixes was evaluated by the indices of slump flowability and static segregation rate with an explanation of the rheological properties, and it was verified by a pumping test. The peculiarity of HPSFC applied for slab/decks overlay was determined using the tests including the early cracking resistance, the water penetration resistance, the bond strength to existing concrete, and the impact resistance. Meanwhile, the basic mechanical properties including cubic compression strength, flexural strength, and toughness were also measured. Results indicate that the fresh mixes met the requirement of high-flowing without segregation, although the indices varied with the influence of P/A ratio and PP fiber content. The resistances to early cracking and water penetration obviously improved by increasing the PP fiber content. The bond strength to existing concrete could be improved by increasing the PP-fiber content. The impact resistance enhanced with the increase of the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content. The compressive strength and flexural strength presented an increased tendency with the P/A ratio, while the flexural toughness reached a peak at certain values of P/A ratio and PP fiber content. Comprehensively, for the high-flowability HPSFC designed with a water-to-binder ratio of 0.36, a fly-ash content of 30%, and a sand ratio of 52%, the optimal P/A ratio is 0.54 and the PP-fiber content is 0.90 kg/m3.

1 Introduction

The concrete slab/deck overlay is constructed in a case for linking the main precast members (T-beam, hollow slab, or box beam) together to ensure the assembly, and it is more commonly used for the pavement of the structural members including floorboard, ground plate, bridge deck, road slab, and container terminal storage yard. It plays an important role in facing the environmental action, directly subjecting to the vehicle loads or the impaction of the piling heavy objects. This needs the concrete slab/deck overlay having peculiarity to meet the requirement in these special working conditions. Therefore, with the premise of common mechanical properties of a structural concrete, the overlay concrete leads to a safely bond strength between the in situ cast concrete and the surface of precast members [1,2]. Commonly, with the premise of common mechanical properties of a structural concrete, the overlay concrete needs a safely bond performance to the existing concrete of precast members or slab/decks [1,2]. Meanwhile, it should have the resistances to cracking and water penetration to protect the steel reinforcements to avoid corrosion of main concrete structural members [3,4]. In case of subjecting impaction from skip motion of vehicle or heavy objects, it should have sufficient impact resistance [5].

Nowadays, the high-flowability concrete has been widely used for construction with automobile pump. Compared with conventional concrete, the pumped concrete is produced with a higher volume of binders and a smaller particle size of coarse aggregate to meet the high-flowing performance for pumping construction [6,7,8]. This leads to an increasing shrinkage that is unbeneficial to the resistance of concrete to cracking, especially at the early age of concrete. However, some countermeasures including the surface of the concrete overlay covered with plastic film or felt, and continuously cured by spraying water, the criss-cross cracks as well as peeling off of concrete cannot be eliminated [2,4,5]. Therefore, improving self-resistance of concrete is essential to solve this problem. In this aspect, except for optimizing the mix proportion of concrete with conventional constituents [8,9], admixing fibers including steel fiber and synthetic fiber can develop a higher performance of concrete that relates to the cracking resistance and the tensile strength [10,11,12]. On the one hand, this attributes to the bridging effect of uniformly distributed steel fiber across the micro- and macro-cracks of concrete matrix. As a result, the performances of concrete related to tensile effect including the tensile strength, the flexural strength and toughness, the fatigue resistance, the impact resistance as well as the restrain to shrinkage are well improved [13,14,15,16]. On the other hand, except for improving the flexural toughness and impact resistance to some extent, the fine and short synthetic fibers such as polypropylene fiber (PP-fiber) and polyvinyl alcohol fiber (PVA fiber) remarkably contribute to decreasing the shrinkage of concrete especially at early age [17,18,19,20]. Therefore, the steel fiber and the synthetic fiber focus on improving concrete from different aspects. This brings a possibility to further develop the hybrid advantages of steel fiber and synthetic fiber at macro- to micro-levels on the improving concrete, especially in shrinkage reduction and water impermeability [21,22,23]. The peculiarity of the concrete reinforced with hybrid steel and synthetic fibers is suitable for the overlay of slab/decks.

However, except for the study on pumpability and mechanical properties of steel fiber-reinforced concrete for remote-pumping construction, no study has been conducted on the hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete for pumping construction [24]. The crux of the problem is worried about the risk of pump pipe blocking, due to a higher cohesiveness of the fresh mix with hybrid fibers. To put away this worry, an experimental study was carried out on the pumpability of the hybrid PP-fiber and steel fiber-reinforced concrete (HPSFC) for the application in overlay of slab/decks. The HPSFC was produced with 0.8% volume fraction of steel fiber considered the factors of the volume ratio of binder paste to aggregates (P/A ratio) varied from 0.48 to 0.60, and the PP-fiber content changed from 0.45 to 1.35 kg/m3. The main performances of hardened HPSFC were also concerned on the early cracking resistance, water impermeability, bond strength to existing concrete and impact resistance, as well as the basic mechanical properties. The pumpability of fresh mixes was verified by a pumping test, while it is explained with the rheological properties. The variations of the performances of hardened HPSFC are also analyzed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Raw materials

The raw materials used in this experiment included cement, fly-ash, river sand, crushed limestone, steel fiber, PP-fiber, superplasticizer, and water. The ordinary Portland cement of strength grade 42.5 produced by Xinxiang Tianrui Cement Co. Ltd., Henan, China, was used with the properties as summarized in Table 1, which met the specification of China code GB 175 [25]. The class-I fly-ash supplied by Hebi Tongli Building Materials Co. Ltd., Henan, China, was used as the mineral admixture with the properties as summarized in Table 2, which met the requirements of China codes GB/T 1596 [26]. The natural river sand with fineness modulus of 2.65 was gathered from the beach of Tanghe River, Henan, China. The crushed limestone was used in gradation with a maximum particle size of 20 mm, which met the continuous gradation in specification [27], and satisfied the requirement for pumped concrete related to the diameter of pumping pipe and the length of steel fiber [6,10]. The main properties of river sand and crushed limestone are summarized in Table 3. The ingot-mill steel fiber was used with a length of 32.5 mm, an equivalent diameter of 0.8 mm, and a tensile strength over 860 MPa, which was produced by Shanghai Harex Steel Fiber Technology Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China. The PP-fiber was used with a length of 12 mm, a diameter of 0.03 mm, a tensile strength over 400 MPa, and an apparent density of 910 kg/m3, which was produced by Shanghai Chengqi Chemical Technology Co. Ltd., Shanghai, China. The properties of steel fiber and PP-fiber met the specification of China code JG/T 472 [10] and CECS 38 [11]. The superplasticizer was a compound pumping agent with 23.7% water reduction, 16.1% solid content, and 3.21% alkali content, and having a setting time differential of 145 min, a shrinkage rate of 103%, and the compressive strength ratio of 165 and 153% at a curing age of 7 and 28 days, which was produced by Jiangsu Subote New Materials Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China. The properties of superplasticizer met the specification of China code GB 8076 [28].

Physical and mechanical properties of cement

| Apparent density (kg/m3) | Fineness (m²/kg) | Water requirement of normal consistency (%) | Setting time (min) | Compressive strength (MPa) | Flexural strength (MPa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | 3 days | 28 days | 3 days | 28 days | |||

| 3,052 | 356 | 26.0 | 223 | 273 | 26.7 | 47.5 | 4.7 | 12.8 |

Physical and mechanical properties and the main chemical composites of fly-ash

| Apparent density (kg/m3) | Specific surface area (m2/kg) | Fineness (%) | Water demand (%) | Water content (%) | Activity index (%) | Main chemical composition (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | ||||||

| 2,250 | 406 | 20.3 | 98 | 0.42 | 86.0 | 50.3 | 31.1 |

Main properties of the coarse and fine aggregates

| Aggregates | Density (kg/m³) | Porosity (%) | Water content (%) | Water absorption (%) | Mud content (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apparent | Bulk | Closed packing | Bulk | Closed packing | ||||

| Crushed limestone | 2,730 | 1,505 | 1,700 | 44.9 | 37.8 | 0.31 | 0.75 | 2.70 |

| River sand | 2,597 | 1,600 | 1,685 | 38.4 | 35.1 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 1.90 |

2.2 Mix proportion

Based on the diagnoses of concrete slab/deck overlay and the specification of pumped concrete in China code JGJ/T 10 [6], the HPSFC was designed to reach a target strength grade of C40 with a cubic compressive strength of 48.2 MPa, and to be pumped a maximum distance around 1,000 m or a maximum height about 200 m with an initial slump of 220–260 mm and a slump-flow of 450–600 mm. The mix proportion of HPSFC was calculated with the absolute volume method, in which the river sand and crushed limestone were counted at the saturated and surface-dry condition, and the steel fiber was counted as coarse aggregate [10]. The fly-ash content was set at 30% for a common amount of admixture, and the water-to-binder ratio could be determined as 0.36 with the prediction formula of compressive strength of concrete [10]. By referencing the previous study, the sand ratio was 52% and the water dosage was 192.4 kg/m3 for a high-flowability concrete with 0.8% volume fraction of steel fiber [24]; the volume ratio of binder paste to aggregates (abbrev. P/A ratio) was selected as 0.48, 0.54, and 0.60. The PP-fiber content was set as 0.45, 0.90, and 1.35 kg/m3 based on the previous study of high-flowability concrete with PP-fiber [18]. Finally, the mix proportions of test HPSFCs are summarized in Table 4. The number followed by letter PA represents the P/A ratio of 0.48, 0.54, and 0.60, and that followed by letter SP represents the PP-fiber content of 0.45, 0.90, and 1.35 kg/m3.

Mix proportions of test HPSFCs

| Identifier | P/A ratio | PP-fiber volume fraction (%) | Dosage of raw materials (kg/m3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | Fly-ash | Water | Crushed stone | Sand | Steel fiber | PP-fiber | Pumping agent | |||

| PA1SP1 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 305 | 131 | 157 | 818 | 954 | 62.8 | 0.45 | 7.41 |

| PA2SP1 | 0.54 | 0.05 | 329 | 141 | 169 | 786 | 920 | 62.8 | 0.45 | 8.00 |

| PA3SP1 | 0.60 | 0.05 | 354 | 152 | 182 | 754 | 885 | 62.8 | 0.45 | 8.59 |

| PA3SP2 | 0.60 | 0.10 | 354 | 152 | 182 | 754 | 885 | 62.8 | 0.91 | 8.59 |

| PA3SP3 | 0.60 | 0.15 | 354 | 152 | 182 | 754 | 885 | 62.8 | 1.36 | 8.59 |

2.3 Test methods

A single-shaft forced mixer was used for mixing the raw materials with a process summarized in Figure 1. The workability of fresh mix was evaluated with the slump and slump-flow and the static segregation rate that measured using test methods specified in China code GB/T 50080 [29]. Some operation process was adjusted by referencing the previous study [30]. The rheological property of fresh HPSFC including the yield stress and the plastic viscosity was measured by the eBT-V concrete rheometer produced by Germany Schleibinger Co. Ltd. The test for rheological property was performed within 60 s, in which the rotating speed uniformly increased from zero to 30 rpm at the first 30 s and then uniformly decreased to zero at the second 30 s.

Mixing process of raw materials for the HPSFC.

After the tests of workability using standard methods, the pumping test was conducted in laboratory using a secondary structure concrete pump that was produced by Henan Yigong Machine & Equipment Co. Ltd. China. Using the automatic air pressure technology of piston structure and pumping the concrete with S-pipe valve, the pump is composited with hopper, piston cylinder, S-pipe valve, and pump pipe [24]. The pump has a maximum pumping ability of 6 m³/h, a working pressure of 10 MPa while a peak-pressure of 15 MPa, a motor power of 5 kW and a filling height of 0.7 m for fresh mix. A pipe of 6 m length with 80 mm diameter was used for cyclic pumping. With a flow of concrete in pump pipe at 0.47 m/s, a test simulated 100 m pumping distance of 220 s.

After the testing for workability, the fresh mix was artificially mixed again and poured into the molds to form the specimens that were required for testing of hardened HPSFC. Test for the early cracking resistance of HPSFC was conducted according to the specification of China code GB 50082 [31]. The steel mold was composited by surrounded U-steel of 63 mm × 40 mm × 6.3 mm on a steel plate of 100 mm × 100 mm × 5 mm. Several short steel bars were welded on the inner surface of U-steel to produce a confinement for the HPSFC specimen. Before casting of HPSFC, a plastic film was paved on the bottom steel plate to free the bottom surface of HPSFC specimen. After HPSFC formed in the mold, the exposure simulation test began with an electric fan blowing to the surface of specimen for 24 h; the crack width and length were detected with an automatic crack viewer produced by Beijing Zhibolian Technology Co. Ltd. Beijing, China. The nominal total area (A cr) and the crack reduction factor η cr are calculated as follows; the average of two specimens for a HPSFC was used as the test result in this study:

where ω i,max is the maximum width of the ith crack, mm; l i is the length of the ith crack, mm; A cr,0 and A cr,f are the nominal total crack areas for the reference specimen and the HPSFC specimen, respectively.

The water penetration resistance of HPSFC is known as a property that relates to the durability, because the corrosive substances are always carried by water penetrated into concrete. It was measured according to the specification of China code GB/T 50082 [31]. The water penetration tester produced by Zhangjiagang Jianyi Equipment Co. Ltd. China, was used. The specimen was a frustum of cone with a top section of ϕ175 mm, a bottom section of ϕ185 mm, and a height of 150 mm. Six specimens as a group were tested on the tester under a water pressure of 1.3 MPa that sustained for 24 h. Then, the specimens were split on a testing machine. The water penetration depth was measured along the bottom edge at 10 points. The average of 10-point test values was used as the water penetration depth of a specimen, and the average of six specimens of a group was taken as the water penetration depth of a HPSFC. According to the specification of China code SL352 [32], the relatively permeability coefficient k r is calculated as

where h m is the average water permeable height, cm; T is the sustainable time, s; H is the pressure presented by water head, cm.

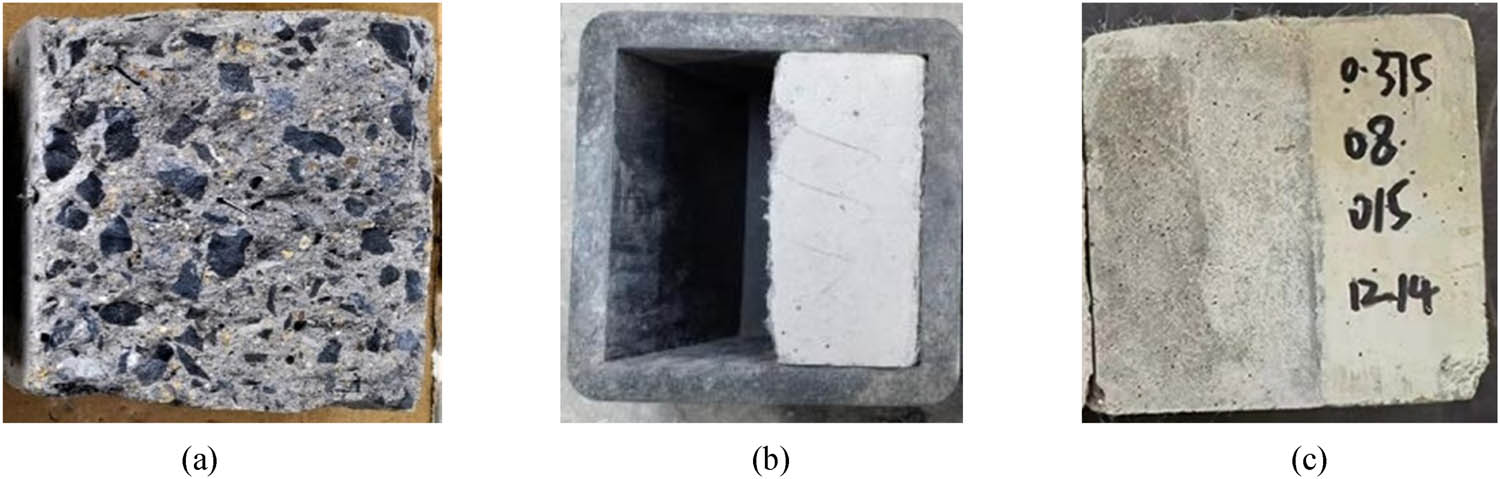

The splitting tensile method perpendicular to the bond section was used to measure the bond strength of HPSFC to the existing concrete, while the splitting load was exerted on the bond section of specimens [33,34]. To simulate the rough surface of the existing concrete, the cubic specimens with a dimension of 150 mm of the conventional concrete with a strength grade of C40 were split into two parts on testing machine, and the splitting surface was artificially shaped to expose coarse aggregates and keep a similar roughness. The surface roughness was measured by the sand filling method, and the average rough depth was around 4.5 mm. As shown in Figure 2, the half block with rough surface was placed in the mold, and the HPSFC was cast into the remnant half space to form the specimen for bond test, and the average of five specimens for a HPSFC was used as the test result in this study. Using the test of bond strength, the splitting tensile strengths of conventional concrete and HPSFC were also tested.

Preparation of specimens for the test of bond strength: (a) rough surface of existing concrete, (b) specimen molds, and (c) specimens.

The impact resistance of HPSFC was determined on MTS automatic drop hammer impacting testing machine. According to the specification of China code CECS 13 [35], a steel hammer of 4.5 kg weight automatically drops from a height of 500 mm on the center of a specimen with a dimension of ϕ150 × 63 mm. The numbers of impact at initial cracking on surface of specimen, and that at failure when the cracks extension leads the specimen contacted with at least three of surrounding baffles, were recorded. The impact energy dissipation can be calculated as follows, and the average of six specimens for a HPSFC was used as the test result in this study:

where W is the impact energy dissipation, J; N is the number of impact; m is the weight of hammer, kg; h is the drop height of hammer, m; g = 9.81 m/s2.

The cubic compressive strength of HPSFC was determined using a testing machine according to the specification of China code GB 50081 [33]. The dimension of cubic specimens was 150 mm, and three specimens were made for a HPSFC as a trial. As shown in Figure 3, the HPSFC specimens failed with less crushed and linked with fibers across cracks, which kept an entirety without broken.

Test of cubic specimens of HPSFC under compression.

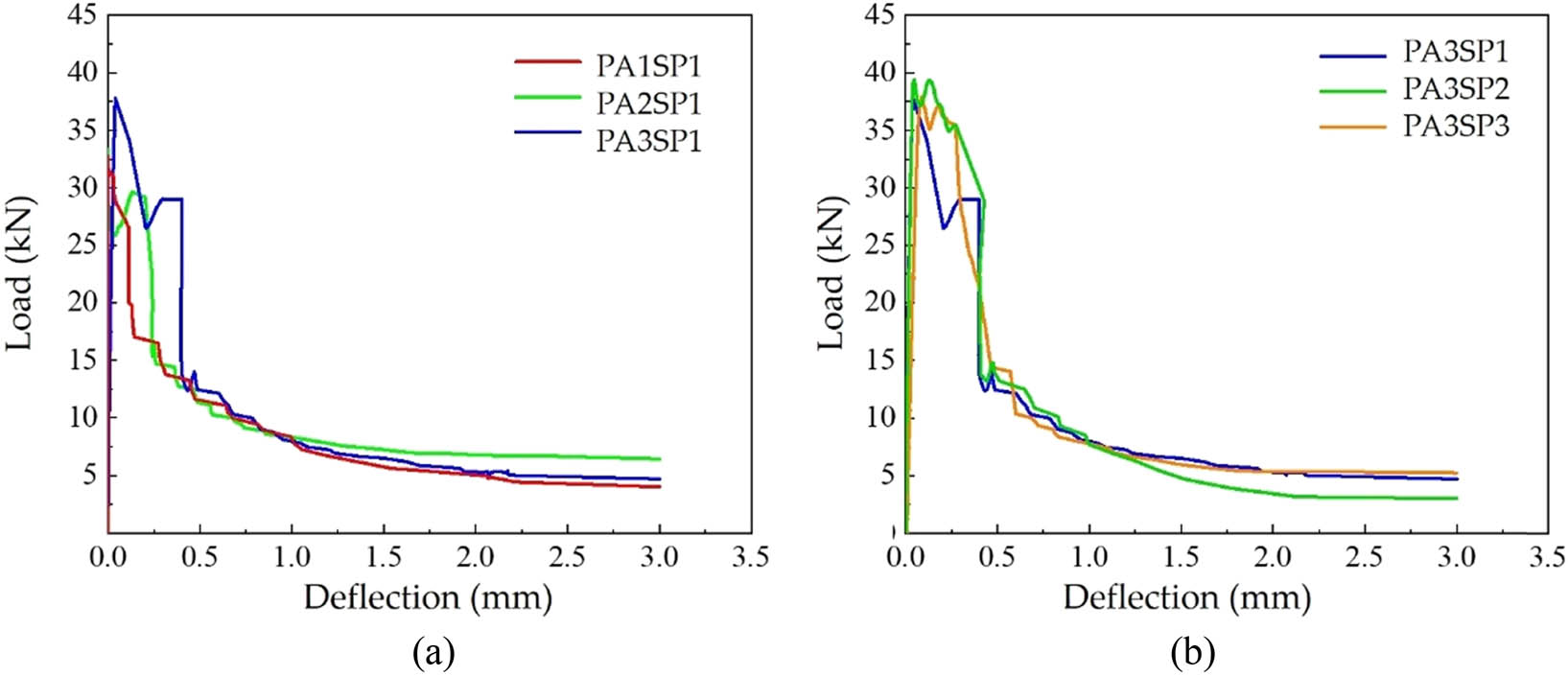

The flexural toughness of HPSFC was determined using a third-point loading test on the beam specimens with a span of 450 mm by a testing machine according to the specification of China code JG/T 472 [10]. The specimen was made with a section of 150 × 150 mm and a length of 550 mm. Three specimens were made for a HPSFC as a trial. As shown in Figure 4, a displacement meter installed at mid-span automatically measures the deflection of test beam under two concentrated loads. Normally, a complete load-deflection curve for each test specimen can be obtained, as the crack at the mid-span segment under pure bending was bridged with steel fibers and PP-fibers [36]. The steel fibers and PP-fibers across crack lost the bond to concrete matrix or broke with the increase of exerted load, and the mid-span deflection sustainably increased under the post-peak load. This leads the HPSFC to have flexural toughness without suddenly fractured. The representative curve of each HPSFC is obtained by dealing with three tested curves of each group [37].

Flexural toughness test for HPSFC.

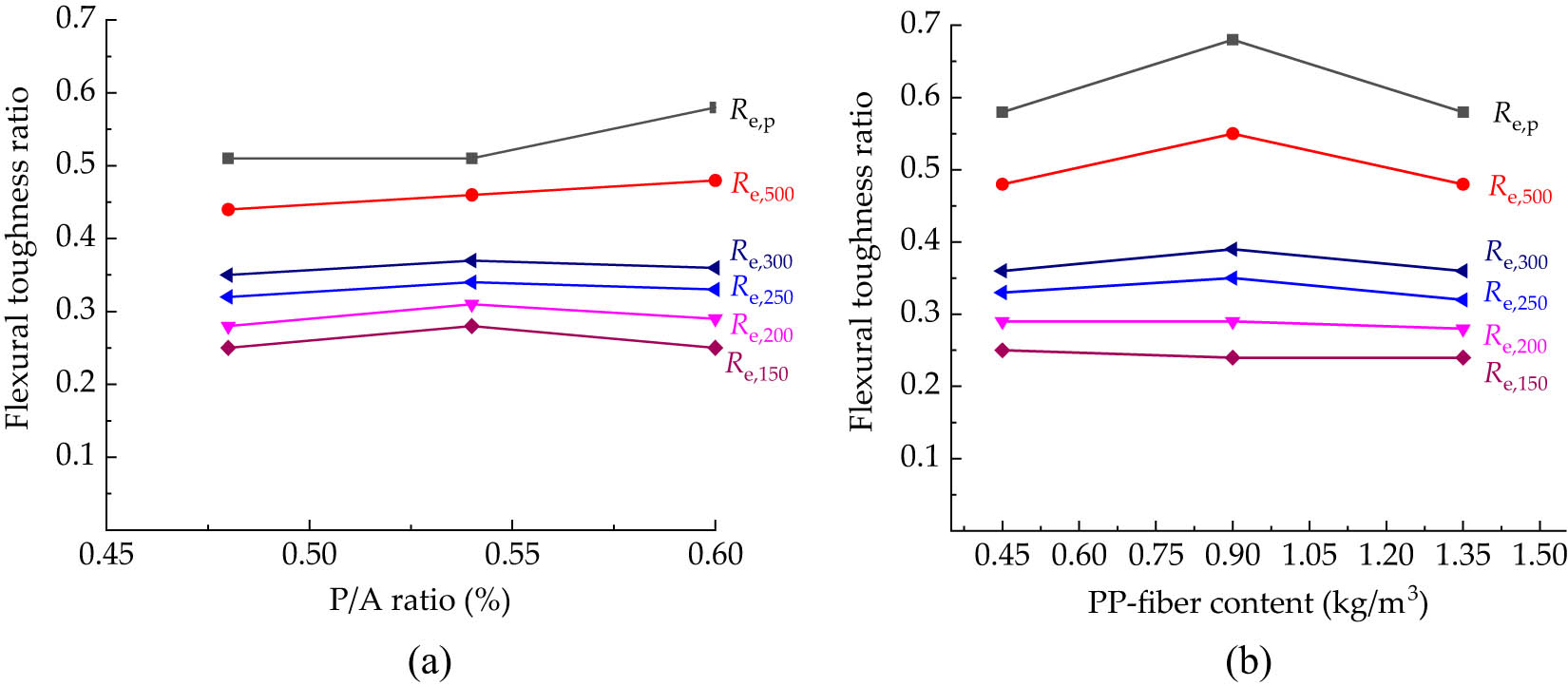

Using the calculation method of flexural toughness as per China code JG/T 472 [10], the initial flexural toughness ratio R e,p is computed to represent the pre-peak-load deflection toughness, and the remaining flexural toughness ratio R e,k is computed to represent the post-peak-load deflection toughness at a given deflection. A larger R e,p indicates a better enhancement of steel fibers on the flexural performance of HPSFC before it reaches the ultimate flexural strength, while a larger R e,k represents a great contribution of fibers to the remaining flexural strength and energy absorption capability of HPSFC [36,38]:

where f f is the flexural strength of HPSFC, MPa; P max is the peak load at the complete load–deflection curve, N; L 0 is the span of specimen, mm; b and h are the cross-sectional width and depth of specimen, mm; δ p is the deflection at the peak load, mm; δ k is a given deflection at condition of L 0/k (k = 500, 300, 250, 200, 150), mm; Ωp is the area enveloped by the curve within the deflection δ p, N mm; Ωp,k is the area enveloped by the curve within the deflection from δ p to δ k, N mm.

Except for those specimens tested for early cracking resistance, all the specimens were covered with plastic film and placed at laboratory room for 24 h before demolded. The specimens were cured in the standard curing room at a temperature of 20 ± 5°C and a relative humidity over 90%.

3 Workability of fresh mixes

3.1 Slump flowability

As summarized in Table 5, the slump and slump-flow of fresh mixes present an expected tendency that increased with the P/A ratio and decreased with the increase of PP-fiber content. This attributes to the increased volume of flowable binder paste with the P/A ratio and the linkage of fibers that arrested the flowing of binder paste. Considered that the initial slump of HPSFC varied from 230 to 255 mm, and the initial slump-flow varied from 470 to 600 mm, the pumping distance could reach 1,600 m when a pump pipe with 125 mm diameter is used as specified in China code JGJ/T 10 [6]. Meanwhile, except for the HPSFC with 0.15% volume fraction of PP-fiber, the other HPSFCs presented a slump loss of 20–30 mm after standing for 1 h. This was within the limit of 30 mm specified in China code GB 50164 [7]. After pumped by the simulation pumping test, the slump reduced to 150–195 mm, while the slump-flow reduced to 310–380 mm, due to the hydration of cement at a high temperature in pump pipe. The losses of slump and slump-flow took place on the HPSFC with the highest P/A ratio of 0.60. This indicates more content of cement hydrated during the pumping to elevate the temperature and then accelerated the hydration of cement to reduce the flowability. However, the flowability still met the requirement of flowability concrete specified in China code JGJ 55 [39].

Test results of slump and slump-flow of fresh mixes

| Fresh mix | Slump (mm) | Slump loss at 1 h (mm) | Slump-flow (mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Stand for 1 h | After pumped | Initial | After pumped | ||

| PA48PF5 | 230 | 205 | 180 | 25 | 470 | 340 |

| PA54PF5 | 240 | 220 | 195 | 20 | 500 | 380 |

| PA60PF5 | 255 | 225 | 195 | 30 | 600 | 350 |

| PA60PF10 | 235 | 210 | 175 | 25 | 550 | 320 |

| PA60PF15 | 230 | 195 | 150 | 35 | 500 | 310 |

As summarized in Table 6, the plastic viscosity and yield stress of fresh HPSFC decreased with the increase of P/A ratio and increased with the PP-fiber volume fraction, whatever before or after pumped. With the increase of P/A ratio from 0.48 to 0.54 and 0.60, the plastic viscosity decreased by 16.9 and 64.5% and the yield stress decreased by 63.3 and 93.6%. This is consistent with an obvious increase of the slump-flow than the slump and corresponds to the increased tendency of static segregation at initial and after pumped. Meanwhile, with the increase of PP-fiber volume fraction from 0.05 to 0.10% and 0.15%, the plastic viscosity increased by 64.3 and 145.2% and the yield stress increased by 27.6 and 76.6%. This is consistent with an obvious decrease of the slump than the slump-flow and corresponds to the decreased tendency of static segregation at initial and after pumped.

Test results of rheological properties of fresh mixes

| Fresh mix | Before pumped | After pumped | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic viscosity (Pa s) | Yield stress (Pa) | Plastic viscosity (Pa s) | Yield stress (Pa) | |

| PA48PF5 | 35.5 | 367.2 | 76.7 | 440.2 |

| PA54PF5 | 29.5 | 134.9 | 39.7 | 231.8 |

| PA60PF5 | 12.6 | 23.5 | 19.8 | 55.0 |

| PA60PF10 | 20.7 | 30.0 | 117.4 | 138.7 |

| PA60PF15 | 30.9 | 41.5 | 123.5 | 423.6 |

From the test results of rheological properties of fresh mixes, it can be seen that a dominating effect of the P/A ratio existed on the yield stress, because the skeleton of aggregate blocks the flowing of binder paste [24]. Comparatively, the plastic viscosity of fresh mix increased because more binder paste was bonded on the fine and short-and-thin PP-fibers, while the yield stress of fresh mix became higher because the staggered dispersion of PP-fibers confined the flowable deformation of binder paste.

Compared to the initial rheological properties, the plastic viscosity and the yield stress of fresh mix multiplied after pumped, which were highly influenced by the PP-fiber volume fraction than the P/A ratio. This reveals that different from the independent particles of aggregate, the PP-fibers built an interlinked frame bonded with cement hydrates to confine the flowability binder paste. With the increase of PP-fiber volume fraction, the frame became complete to present a much higher confinement.

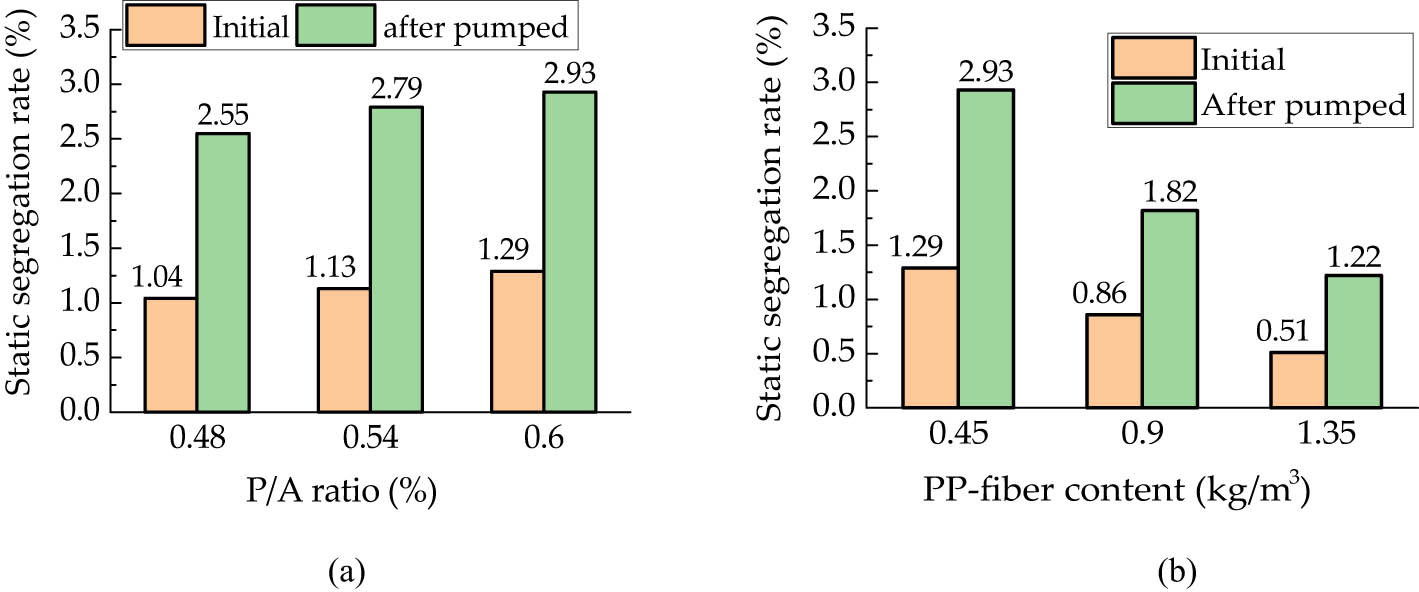

3.2 Static segregation

The static segregation rate is commonly used to intuitively estimate the bleeding resistance of fresh mix. As presented in Figure 5 for the test results, the static segregation rate increased by 8.6 and 24.0% with the P/A ratio increased from 0.48 to 0.54 and 0.60. This shows that the segregation rate increased with the P/A ratio, because more free paste leaved in the gaps of aggregates. The segregation of fresh mixes became obvious after pumped with an increment of 145.2, 146.9, and 127.1%, respectively. This indicates that the fresh mixes had a tendency that the paste freely separated from the wrapped aggregates under pumping pressure. When fixed P/A ratio at 0.60, the static segregation rate reduced by 17.3 and 51.0% with the PP-fiber content increased from 0.45 to 0.90 kg/m3 and 1.35 kg/m3. This indicates that the segregation of fresh mix can be obviously reduced by adding more PP-fibers, because the cohesiveness of paste was increased with the mesh binding of PP-fibers. The segregation rate of pumped fresh mixes increased by 127.1, 111.6, and 139.2%, compared to those initial values before pumped. However, the tendency was kept ensuring that the static segregation rate decreased with the increase of PP-fiber content.

Static segregation rate of HPSFC changed with (a) P/A ratio and (b) PP-fiber content.

Generally, the static segregation rate of fresh mixes was 2.93% in maximum. This was far below the limit of 10% specified for pumping concrete in China code JGJ/T 10 [6]. Therefore, the static segregation of fresh HPSFC was not an issue that should be detected, due to the contributions of steel fibers and PP-fibers to binder paste retaining by surface coating and constituents gathering.

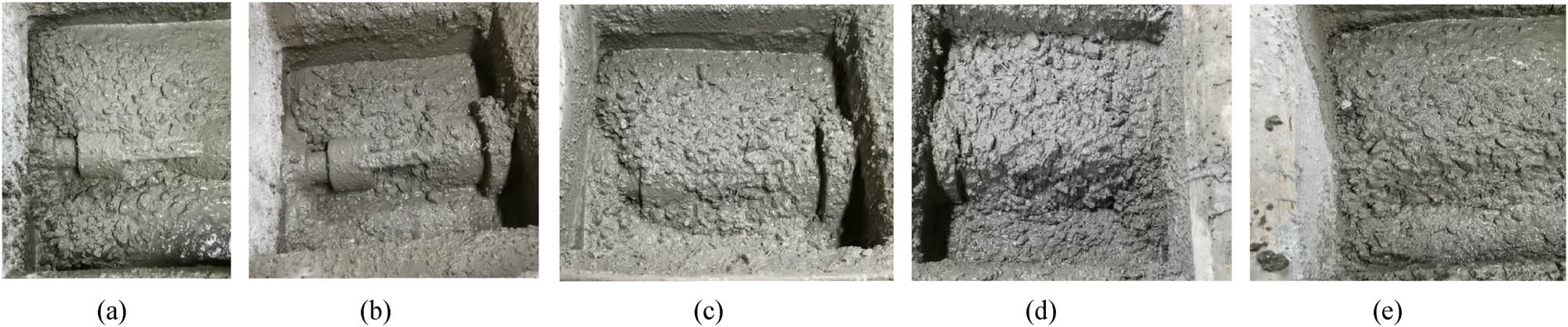

3.3 Pumping verification test

The pumpability of fresh mix was observed on the flow state in the hopper, as presented in Figure 6. All fresh mixes presented good cohesive without the water bleeding and the exposure of coarse aggregates and steel fibers, while the formation of lubricating layer benefited to the flow of fresh mix in pump pipe. The pump became easier with the increase of P/A ratio for fresh HPSFC due to the increased volume of binder paste (Figure 6c). An obvious slow-down appeared for the fresh HPSFC pumped into piston cylinder with the increase of PP-fiber content, due to the increased linkage of PP-fibers (Figure 6e).

Pumping status of fresh HPSFC: (a) PA1SP1, (b) PA2SP1, (c) PA3SP1, (d) PA3SP2, and (e) PA3SP3.

4 Peculiarity applied for slab/deck overlay

4.1 Resistances to early cracking

Table 7 summarizes the test results of the early cracking resistance of HPSFC, where PA1, PA2, and PA3 were the reference concretes without fibers in condition of the P/A ratio at 0.48, 0.54, and 0.60. Obviously, the number of cracks, the maximum crack width, and the nominal total area of cracks were all increased with the P/A ratio for the reference concretes. This indicates that the shrinkage of concrete mainly came from the set cement at early age. With the increase of P/A ratio, the volume of binder paste increased, while that of coarse aggregates decreased, and the higher shrinkage of set cement was less confined by the coarse aggregates. Corresponding to the appearance of more cracks with larger maximum crack width, the A cr,0 increased by 4.0 and 8.6% for concrete with P/A ratio increased from 0.48 to 0.54 and 0.60. Obviously, this situation could be improved by adding steel fibers and PP-fibers.

Test results of early crack resistance of test specimens

| Identifier | Number of cracks | Max. crack width (mm) | Nominal total area of cracks (mm2) | Reduction factor η cr (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA1 | 9 | 0.08 | 49.1 | — |

| PA2 | 10 | 0.12 | 51.0 | — |

| PA3 | 14 | 0.18 | 53.3 | — |

| PA1SP1 | 6 | 0.10 | 34.6 | 29.5 |

| PA2SP1 | 7 | 0.12 | 34.8 | 31.7 |

| PA3SP1 | 9 | 0.16 | 35.7 | 33.1 |

| PA3SP2 | 4 | 0.14 | 28.2 | 47.0 |

| PA3SP3 | 1 | 0.04 | 1.68 | 96.9 |

For the HPSFC with a PP-fiber content of 0.45 kg/m3, the A cr,f could be decreased with the decrease of the number of cracks and the maximum crack width. Compared with that of reference concrete, the reduction factor changed from 29.5 to 33.1%. This reveals a better confinement of steel fibers and PP-fibers on the shrinkage of set cement that contributes to the early cracking resistance of HPSFC. With the increase of PP-fiber content from 0.45 to 1.35 kg/m3, the improvement on the early cracking resistance of HPSFC became obvious, which led to almost disappearance of early crack on HPSFC with a PP-fiber content of 1.35 kg/m3. This means that the HPSFC can be produced without early cracking by adding certain PP-fibers.

According to the specification of China code CECS 38 [11], the first, second, and third degree of cracking resistance of HPSFC, respectively, corresponds to η cr ≥ 70%, 55 ≤ η cr < 70, and 40 ≤ η cr < 55. Therefore, the HPSFC with a PP-fiber content of 0.45 kg/m3 did not reach a target of cracking resistance even if at the third degree. Meanwhile, the HPSFC with a PP-fiber content of 0.90 kg/m3 reached the third degree of cracking resistance, while that with 1.35 kg/m3 was best at the first degree. This shows that a higher content over 0.45 kg/m3 was needed to provide sufficient confinement for the early shrinkage of HPSFC.

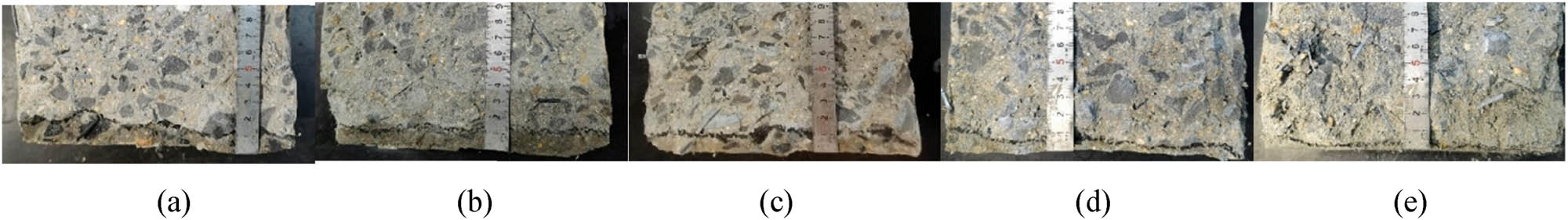

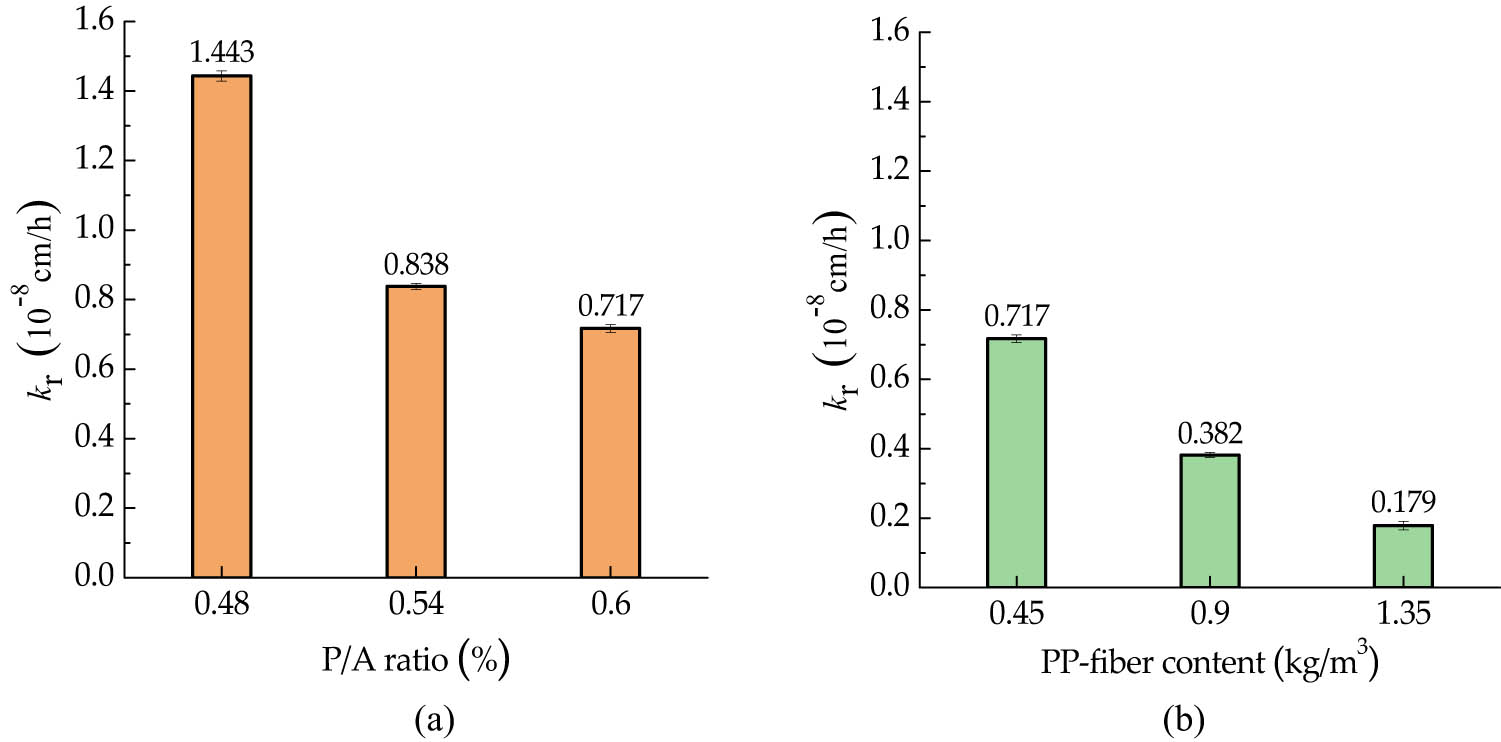

4.2 Resistances to water penetration

Figure 7 presents the measuring of water penetration depth in HPSFC specimens. The black curve marked the variation of water penetration into HPSFC. As observed from the splitting sections, the HPSFC was dense with well-wrapped and uniformly distributed coarse aggregates and fibers, and no macroscopic pores were observed. The water penetration depth was basically flush without the obvious penetration surrounding the coarse aggregates. This presents an average depth with small dispersion. Obviously, the water penetration depth decreased with the increase of the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content.

Water penetration depth of HPSFC changed with P/A ratio and PP-fiber content: (a) PA1SP1, (b) PA2SP1, (c) PA3SP1, (d) PA3SP2, and (e) PA3SP3.

As shown in Figure 8, the relatively permeability coefficient k r obviously decreased with the increase of the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content. That is to say, the resistance of HPSFC to water penetration increased with the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content. Because the water penetration always takes place along the pores and defect of concrete matrix especially those existed around the coarse aggregate, this possibility was lightened by sufficient binder paste of HPSFC with higher P/A ratio. The k r decreased by 42.0% for HPSFC with the P/A ratio increased from 0.48 to 0.54, and that decreased by 14.4% for HPSFC with the P/A ratio increased from 0.54 to 0.60. This indicates that the P/A ratio was insufficient at 0.48 for the HPSFC, and that was well at 0.54, combined with the mechanical properties of HPSFC. Certainly, the P/A ratio of 0.60 was best for HPSFC that presented best performances of resistance to early cracking and of mechanical properties. Compared to that of HPSFC with a PP-fiber content of 0.45 kg/m3, the k r decreased by 46.7 and 75.0% for HPSFC with a PP-fiber content of 0.90 and 1.35 kg/m3. This attributes to the improvement of PP-fibers on refining macro-pores and eliminating defects in concrete matrix. Most notably, this directly relies on the improvement of the early cracking resistance that eliminated the path of water penetrated into HPSFC, as previous study revealed that the water penetration rate of concrete with micro-cracks increased about 10 times [40].

Relative permeability coefficient of HPSFC changed with (a) P/A ratio and (b) PP-fiber content.

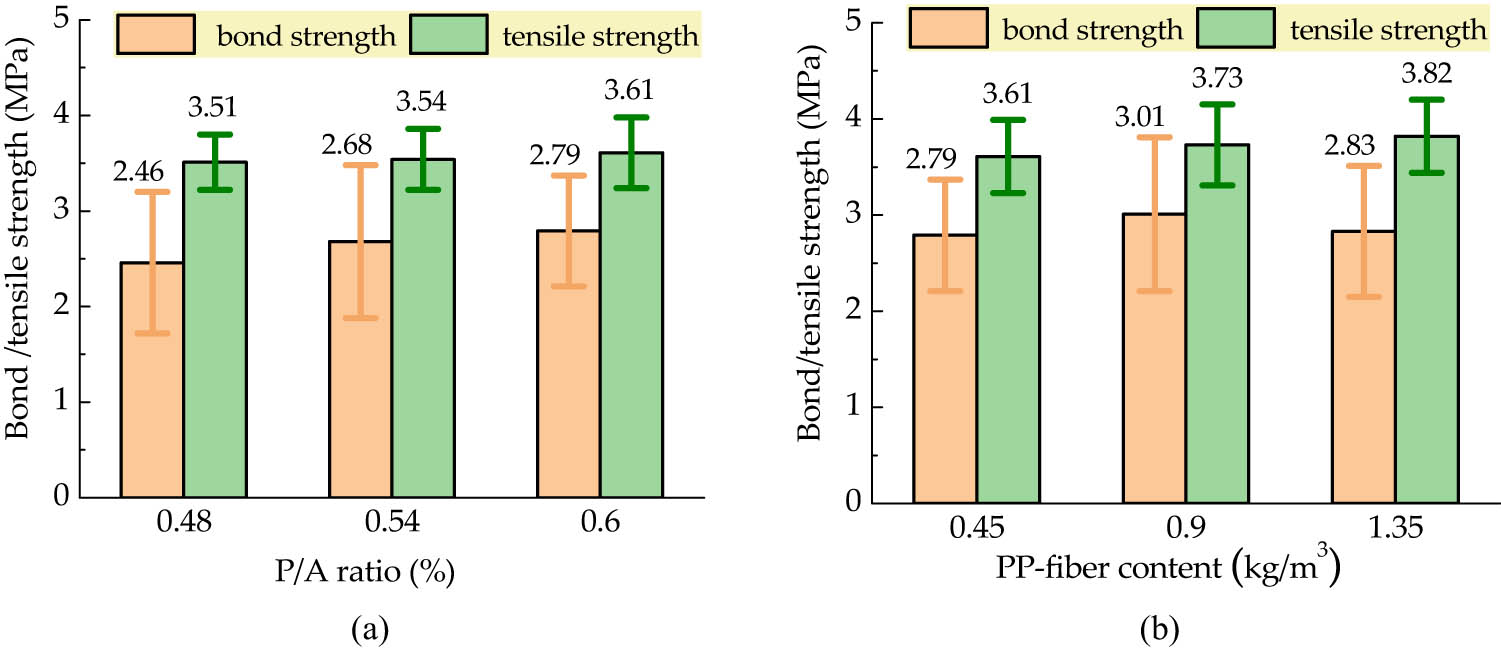

4.3 Bond strength to existing concrete

The splitting tensile strength of conventional concrete was 3.21 MPa. As presented in Figure 9, the splitting tensile strength of HPSFC slightly increased with the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content. The former attributed to the increased binder paste that was well wrapped on coarse aggregates to eliminate the defects on interface between set binder paste and coarse aggregates. The latter was due to the uniform distributed PP-fibers that improved the tensile strength of set cement that benefits to the entire tensile performance of HPSFC. Results of this study indicate that the splitting tensile failure took place on the bond surface of specimens, because the HPSFC and conventional concrete had higher splitting tensile strength. Observing the bond strength of HPSFC to existing concrete, it presents the increasing tendency with the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content. This can be attributed to the beneficial effects that sufficient binder paste benefited to fill the pits on the rough surface of existing concrete and enhance the entirety of indented interface between HPSFC and existing concrete, while a plentiful PP-fibers in the binder paste contributed to improve the stress distribution with a decreased shrinkage of HPSFC on the interface. On an average level, the bond strength was 70.1–80.2% of the tensile strength of HPSFC and 76.7–93.7% of the existed concrete.

Bond strength of HPSFC changed with (a) P/A ratio and (b) PP-fiber content.

However, it should be noted that the dispersion of bond strength was obviously larger than that of tensile strength. This indicates that the bond strength was affected by multifactors except for the HPSFC and existing concrete themselves, especially by the actual morphology feature of existed concrete surface although a similar roughness was evaluated by the sand filling method.

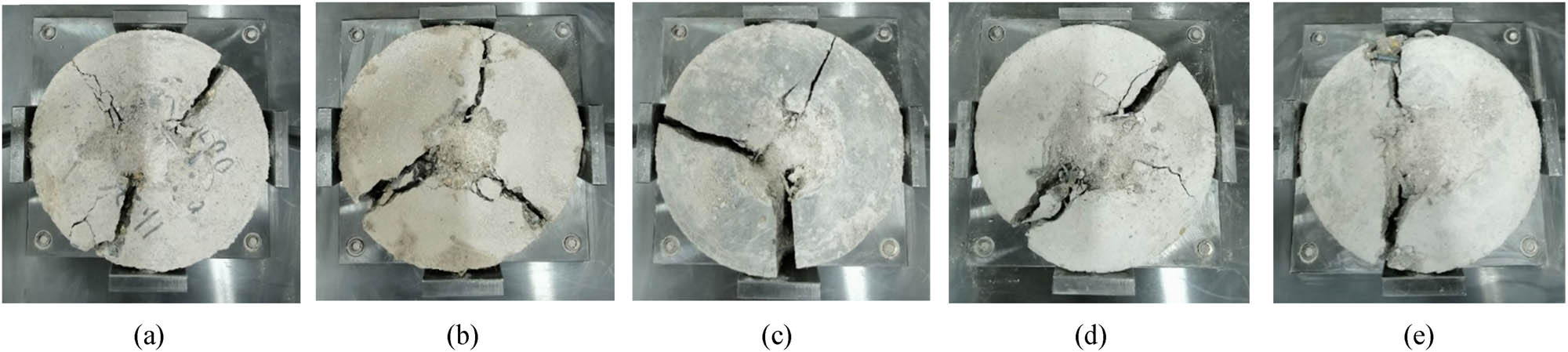

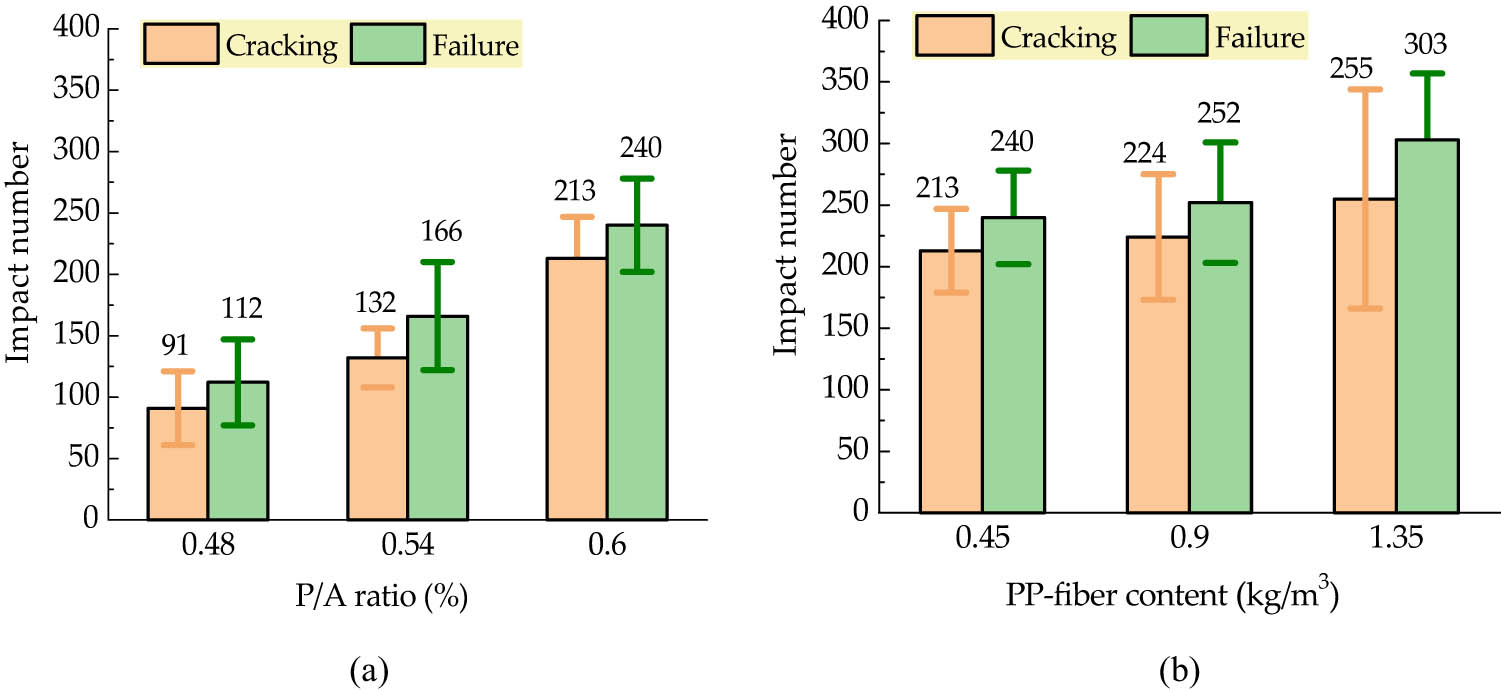

4.4 Impact resistance

As shown in Figure 10, similar failure patterns with three blocks that divided by three cracks appeared on tested specimens of HPSFC with different P/A ratio. A deeper crushed pit appeared on the center of specimen for the HPSFC with the highest P/A ratio. This indicates that the HPSFC with a higher compressive strength gave a higher impact resistance. With the increase of PP-fiber content, only a straight crack presented on the specimens, and the secondary crack disappeared on the specimen of HPSFC with the PP-fiber content of 1.35 kg/m3. This reveals that the linkage of PP-fibers in concrete matrix improved the entirety of HPSFC to resist the impact action.

Impact failure patterns of HPSFC: (a) PA1SP1, (b) PA2SP1, (c) PA3SP1, (d) PA3SP2, and (e) PA3SP3.

Figure 11 summarizes the test number of impact on HPSFC at the initial cracking and the failure states. Generally, the number of impacts on HPSFC specimens increased with the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content; however, a greater dispersion existed on the tested number of impacts on six specimens for a HPSFC. Comparatively, the number of compacts increased remarkably with the P/A ratio. This reveals that the bond of steel fiber in concrete matrix is very important to resist the impact action [24]. Increasing PP-fiber content continues to improve the impact resistance of HPSFC, where the increment reached 13.8 and 20.2% when the PP-fiber content increased from 0.45 to 1.35 kg/m3. Because the number of impacts at the failure only increased by 12.5 to 25.8% from that at the initial cracking, the impact resistance of HPSFC mainly relied on the resistance to initial cracking.

Impact number of HPSFC changed with (a) P/A ratio and (b) PP-fiber content.

5 Basic mechanical properties

5.1 Cubic compressive strength

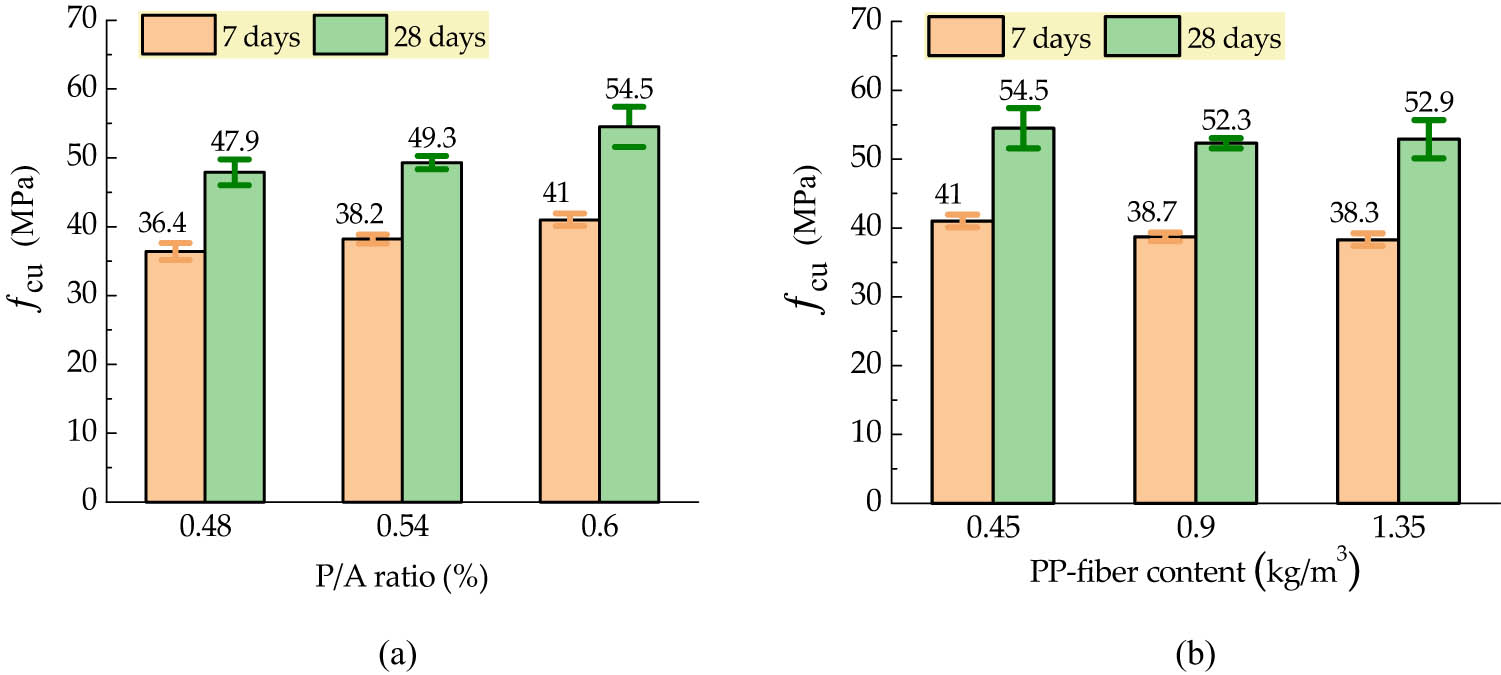

Test results of cubic compressive strength of HPSFC are presented in Figure 12. Except for the strength of PA1SP1, which was less than the target of 48.2 MPa, others were all over it at a curing age of 28 days. The cubic compressive strength of HPSFC increased with the P/A ratio, while that increased by 31.5, 29.1, and 32.9% at a curing age of 28 days from 7 days, respectively, for the HPSFC with a P/A ratio of 0.48, 0.54, and 0.60. This indicates that the set cement accompanied by hydrates of fly-ash dominated the compressive strength of HPSFC, and enough paste wrapped on aggregates was necessary to build a strong structure of HPSFC. Meanwhile, the compressive strength of HPSFC presented a slight decreased tendency with the increase of PP-fiber content, and that increased by 32.9, 35.1, and 38.1% at a curing age of 28 days from 7 days. This indicates that the compressive strength development of HPSFC was less influenced by the randomly distributed PP-fibers in concrete matrix due to the finite deformation confinement of PP-fibers with lower modulus of elasticity.

Cubic compressive strength of HPSFC changed with (a) P/A ratio and (b) PP-fiber content.

5.2 Flexural toughness

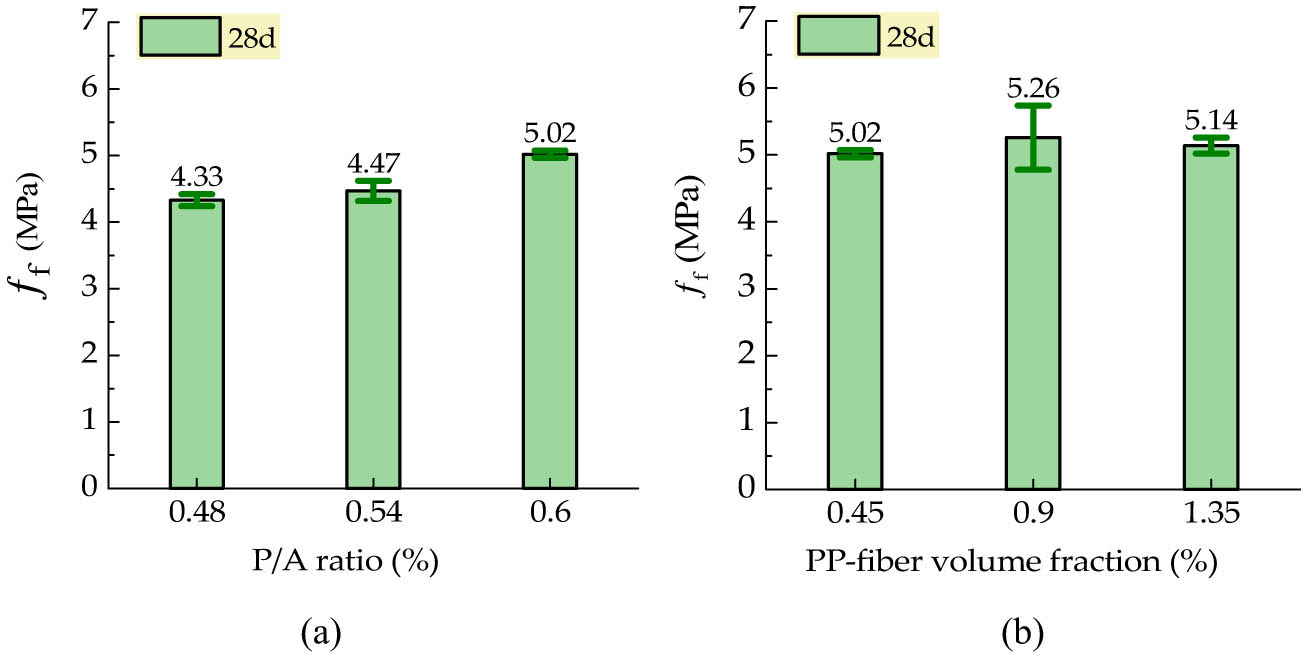

Figure 13 presents the complete load–deflection curves of HPSFC under bending. The peak load increased with the increase of P/A ratio, while an increased tendency of peak load appeared with the increase of PP-fiber content. This can be directly observed on Figure 14, which presents that the flexural strength of HPSFC changed with the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content. The HPSFC with PP-fiber content of 0.90 kg/m3 presented a highest flexural strength of 5.26 MPa. This is attributed to the bond performance between steel fibers and concrete matrix that strengthened with uniformly distributed PP-fibers [37,41]. The HPSFC with higher P/A ratio provided sufficient binder paste wrapped on coarse aggregates to eliminate the defects between the set cement and the surface of coarse aggregates. This creates a good cross-connected architecture of steel fibers across coarse aggregates with a steadily wrapped bond layer of set cement. Meanwhile, the uniformly distributed short-and-thin PP-fibers improved the macro-structure of concrete matrix, which benefits to reinforcing the bond performance of steel fibers to concrete matrix. This inferential analysis can be supported by the post-peak behavior of load–deflection curve presented in Figure 14. A slowly drop-down appeared on the post-peak decline curve of HPSFC with a higher P/A ratio and a greater PP-fiber content, which presented a well-sustainable deflection under a higher load and a second ascending at a relative larger deflection.

Flexural load–deflection curves of HPSFC with (a) P/A ratio and (b) PP-fiber content.

Flexural strength of HPSFC changed with (a) P/A ratio and (b) PP-fiber content.

As shown in Figure 15, the HPSFC with a PP-fiber content of 0.90 kg/m3 reached the highest initial flexural toughness ratio R e,p and the remaining flexural toughness ratio R e,k (k ≤ 250). Meanwhile, the fullness of post-peak decline segment of load–deflection curve ensured a higher R e,500 that corresponded to the deflection of 0.90 mm. The R e,500 remained 80.9 to 90.2% of the R e,p. When the mid-span deflection reached L 0/200, i.e., 2.25 mm, the R e,200 remained 42.6 to 60.8% of the R e,p. This indicates that the HPSFC in this study had better flexural performance with ideal flexural toughness.

Flexural toughness ratio of HPSFC changed with (a) P/A ratio and (b) PP-fiber content.

6 Conclusions

The fresh mixes met the workability for pumping construction. The slump flowability increased with the P/A ratio and decreased with the increase of PP-fiber content. This was in consistent with the variation of the rheological properties. The static segregation rate was limited without having influence on the pumpability of fresh HPSFC.

The HPSFC had a good early cracking resistance and became excellent with the increase of PP-fiber content from 0.45 to 1.35 kg/m3. The early cracking almost disappeared on the HPSFC with a PP-fiber content of 1.35 kg/m3. Correspondingly, the water penetration into HPSFC obviously decreased with the increase of the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content.

The bond strength of SPFRC to existing concrete slightly increased with the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content. On an average level, it could reach 70.1–80.2% of the tensile strength of HPSFC and 76.7–93.7% of the existed concrete. The impact resistance of HPSFC increased with the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content. The compact resistance increased remarkably with the P/A ratio and continuously improved by increasing PP-fiber content.

Except for the SPFRC with the P/A ratio of 0.48, others reached the target cubic compressive strength of 48.2 MPa for strength grade C40. The flexural strength and toughness of HPSFC increased in some extent with the P/A ratio and reached the maximum with the PP-fiber content of 0.90 kg/m3. The tensile strength of HPSFC slightly increased with the P/A ratio and the PP-fiber content.

The HPSFC was designed using the absolute volume method with the water-to-binder ratio of 0.36 with a fly-ash content of 30% and a sand ratio of 52%. The P/A ratio was rational at 0.54 and 0.60. The steel fiber in volume fraction of 0.8% was better with the PP-fiber in content from 0.90 to 1.35 kg/m3. Comprehensively, the optimal mixing ratio can be taken as the P/A ratio of 0.54 and the PP-fiber content of 0.90 kg/m3 for high-flowability HPSFC with a target strength grade C40. The mix proportion of HPSFC can be used for engineering applications.

For future studies, the optimal mix proportion of different strength-grade HPSFC should be examined to meet the engineering requirements. The hybrid coupling effect of steel fiber with PP-fiber is a key point to sufficiently develop the reinforcing ability of different fibers.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by Key Scientific and Technological Research Project of University in Henan, China (22A570002); Introduced International Intelligence Project of Henan, China (GJRC2018HS02); and Doctoral Innovation Fund of NCWU, China (HSZ2022-196).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results, and approved the final version of the manuscript. MZ (Miaomiao Zhu) and MZ (Minglei Zhao) designed the experiments, and KW and YZ carried them out. CL developed the calculation model and performed the fitness. MZ (Miaomiao Zhu), CL, and FL received the funding and prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] JTG D62-2004. Code for design of highway reinforced concrete and prestressed concrete bridges and culverts. Beijing, China: China Communications Press; 2004. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Helsel M, Muñoz J, Haber Z, De la Varga I. Effect of bridge deck surface preparation on the consolidation and bond of UHPC overlays. Constr Build Mater. 2023;364:129860.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129860Search in Google Scholar

[3] Freyne S, Ramseyer C, Giebler J. High-performance concrete designed to enhance durability of bridge decks: Oklahoma experience. J Mater Civ Eng. 2012;24:933–6.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000457Search in Google Scholar

[4] Subramaniam K. Identification of early-age cracking in concrete bridge decks. J Perform Constr Facil. 2016;30:1–9.10.1061/(ASCE)CF.1943-5509.0000915Search in Google Scholar

[5] Su N, Lou L, Amirkhanian A. Assessment of effective patching material for concrete bridge deck-a review. Constr Build Mater. 2021;293:123520.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123520Search in Google Scholar

[6] JGJ/T 10-2011. Technical specification for construction of concrete pumping. Beijing, China: China Building Industry Press; 2011. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[7] GB 50164-2011. Standard of quality control for concrete. Beijing, China: China Building Industry Press; 2011. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zhao M, Dai M, Li J, Li C. Case study on performance of pumping concrete with super-fine river-sand and manufactured-sand. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2023;18:e01850.10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e01850Search in Google Scholar

[9] Yang Y, Ding X, Gu Z, Deng L, Lv F, Zhao S. Lateral pressure test of vertical joint concrete and formwork optimization design for monolithic precast concrete structures. Buildings. 2022;12:261.10.3390/buildings12030261Search in Google Scholar

[10] JG/T 472-2015. Steel fiber reinforced concrete. Beijing China: China Standard Press; 2015. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[11] CECS 38:2004. Technical specification for fiber reinforced concrete structures. Beijing, China: China Plan Press; 2004. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[12] JGJ/T 465-2019. Code for design of steel fiber reinforced concrete structures. Beijing, China: China Building Industry Press; 2020. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Ding X, Li C, Han B, Lu Y, Zhao S. Effects of different deformed steel-fibers on preparation and properties of self-compacting SFRC. Constr Build Mater. 2018;168:471–81.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.02.162Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ding X, Li C, Zhao M, Li J, Geng H, Lian L. Tensile strength of self-compacting steel fiber reinforced concrete evaluated by different test methods. Crystals. 2021;11:251.10.3390/cryst11030251Search in Google Scholar

[15] Zhao S, Li C, Zhao M, Zhang X. Experimental study on autogenous and drying shrinkage of lightweight-aggregate concrete reinforced by steel fibers. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2016;2016:2589383.10.1155/2016/2589383Search in Google Scholar

[16] Li C, Shang P, Li F, Feng M, Zhao S. Shrinkage and mechanical properties of self-compacting SFRC with calcium sulfoaluminate expansive agent. Materials. 2020;13:588.10.3390/ma13030588Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Banthia N, Cheng V. Shrinkage cracking in polyolefin fiber-reinforced concrete. ACI Struct J. 2000;97:432–7.10.14359/7406Search in Google Scholar

[18] Li F, Liang N, Li C. Effects of polypropylene fiber and stone powder of machine-made sand on resistance of cement mortar to cracking. J Basic Sci Eng. 2012;20:895–901.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Bagherzadeh R, Sadeghi A, Latifi M. Utilizing polypropylene fibers to improve physical and mechanical properties of concrete. Text Res J. 2012;82:88–96.10.1177/0040517511420767Search in Google Scholar

[20] Del Savio A, Esquivel D, de Andrade Silva F, Agreda Pastor J. Influence of synthetic fibers on the flexural properties of concrete: prediction of toughness as a function of volume, slenderness ratio and elastic modulus of fibers. Polymers. 2023;15:909.10.3390/polym15040909Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Gao S, Tian W, Zhang E. Application of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete for pavement of bridge deck. Concr Cem Prod. 2010;3:55–9.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Afroughsabet V, Ozbakkaloglu T. Mechanical and durability properties of high-strength concrete containing steel and polypropylene fibers. Constr Build Mater. 2015;94:73–82.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.06.051Search in Google Scholar

[23] Nassif H, Habib M, Obeidah A, Abed M. Restrained shrinkage of high-performance ready-mix concrete reinforced with low volume fraction of hybrid fibers. Polymers. 2022;14:4934.10.3390/polym14224934Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Zhao M, Li C, Li J, Yue L. Experimental study on performance of steel fiber reinforced concrete for remote-pumping construction. Materials. 2023;16:3666.10.3390/ma16103666Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] GB 175-2007. Common portland cement. Beijing, China: China Standard Press; 2007. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[26] GB/T 1596-2017. Fly ash for cement and concrete. Beijing, China: China Standard Press; 2017. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[27] JGJ 52-2006. Standard for technical requirements and test method of sand and crushed stone (or gravel) for ordinary concrete. Beijing, China: China Building Industry Press; 2006. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[28] GB 8076-2008. Concrete admixtures. Beijing, China: China Building Industry Press; 2008. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[29] GB/T 50080-2016. Standard for test method of fresh performance of ordinary concrete. Beijing, China: China Building Industry Press; 2016. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Ding X, Geng H, Shi K, Song L, Li S, Liu G. Study on adaptability of test methods for workability of fresh self-compacting SFRC. Materials. 2021;14:5312.10.3390/ma14185312Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] GB/T 50082-2009. Standard for test method of long-term performance and durability of ordinary concrete. Beijing, China: China Building Industry Press; 2009. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[32] SL 352-2006. Test method for hydraulic concrete. Beijing, China: China Hydropower Press; 2006. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[33] GB/T 50081-2019. Standard for test method of physical and mechanical properties of concrete. Beijing, China: China Building Industry Press; 2019. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Li C, Yang Y, Su J, Meng H, Pan L, Zhao S. Experimental research on interfacial bonding strength between vertical cast-in-situ joint and precast concrete walls. Crystals. 2021;11:494.10.3390/cryst11050494Search in Google Scholar

[35] CECS 13:2009. Standard of test method for fiber reinforced concrete. Beijing, China: China Plan Press; 2009. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Zhao M, Li J, Law D. Effects of flowability on SFRC fibre distribution and properties. Mag Concr Res. 2017;69:1043–54.10.1680/jmacr.16.00080Search in Google Scholar

[37] Ding X, Geng H, Zhao M, Chen Z, Li J. Synergistic bond behaviors of different deformed steel fibers embedded in mortars wet-sieved from self-compacting SFRC with manufactured sand by using pull-out test. Appl Sci. 2021;11:10144.10.3390/app112110144Search in Google Scholar

[38] Zhao M, Li J, Xie Y. Effect of vibration time on steel fibre distribution and flexural properties of steel fibre reinforced concrete with different flowability. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;16:e01114.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01114Search in Google Scholar

[39] JGJ 55-2011. Specification for mix proportion design of ordinary concrete. Beijing, China: China Building Industry Press; 2011. Chinese.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Negin Y, Alireza J, Erfan H. Influence of fibers on drying shrinkage in restrained concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2017;148:833–45.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.093Search in Google Scholar

[41] Li X, Sun L, Zhou Y, Zhao S. A review of steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber reinforced concrete. Appl Mech Mater 2012;238:26–32.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.238.26Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective