Abstract

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are renowned for their low density, high elastic modulus, and exceptional electrical and thermal properties. The continuously developing applications of CNTs provide higher specific stiffness and strength for composite materials. The unique characteristics of CNTs make them ideal reinforcing particles in aluminum matrix composites (AMMCs), which generally exhibit excellent mechanical properties. CNTs/AMMCs are usually prepared using methods such as powder metallurgy, casting, spray deposition, and reactive melting. The uniform diffusion of CNTs in composites is crucial for enhancing the properties of CNTs/AMMCs. The properties of CNTs/AMMCs largely depend on the content, morphology, and distribution of reinforcements in the matrix and the interaction between reinforcements and the matrix. By adding an appropriate volume fraction of CNTs, the hardness, tensile strength, compressive strength, and electrical properties of CNTs/AMMCs were significantly improved. The effects of CNT content on the mechanical properties of CNTs/AMMCs, including the tensile strength, yield strength, compressive strength, stress–strain curve behavior, elastic modulus, hardness, creep, and fatigue behavior, were revealed. The design of microstructure, optimization of the preparation process, and optimization of composition can further improve the mechanical properties of CNTs/AMMCs and expand their application in engineering. The design concept of integrating material homogenization and functional unit structure through biomimetic design of novel gradient structures, layered structures, and multi-level twin structures further optimizes the composition and microstructure of CNTs/AMMCs, which is the key to further obtaining high-performance CNTs/AMMCs. As a multifunctional composite material, CNTs/AMMCs have broad application prospects in fields such as air force, military, aerospace, automation, and electronics. Moreover, CNTs/AMMCs have potential applications in cell therapy, tissue engineering, and other areas.

Graphical abstract

The effects of CNT content on the mechanical properties of CNTs/AMMCs, including the tensile strength, yield strength, compressive strength, stress–strain curve behavior, elastic modulus, hardness, creep, and fatigue behavior, were revealed. CNTs/AMMCs have broad application prospects in cell therapy, tissue engineering, and other fields. Influence of the concentration of CNTs on mechanical characteristics of AMMCs.

1 Introduction

Aluminum-based composite materials (AMMCs) have excellent properties such as low density, high strength and elastic modulus, good ductility, good corrosion resistance, high thermal conductivity, and excellent wear resistance [1,2]. AMMCs are widely used in the automotive, shipbuilding, aerospace, and other industries. As a matrix material, AMMCs are used or considered for a range of applications, including high-speed trains, airplanes, and some automotive parts such as engine cylinder liners, cover plates, piston rings, bearings, connecting rods, and gears. AMMCs are also used in high-pressure valve products, such as pump casings, gears, valves, and turbochargers. In the industrialization process of AMMCs, traditional methods such as heat treatment and plastic deformation make it difficult to improve their mechanical properties further. Choosing appropriate reinforcement materials is crucial for determining the final mechanical properties of composite materials. The emergence of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [3] has shown through theoretical and experimental research that their unique structure and excellent mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties have broad application prospects, attracting great attention from scientists in materials, physics, electronics, chemistry, and other fields, and becoming a research frontier and hotspot in the international field of new materials [4]. The mechanical properties of multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), measured in situ by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), showed a maximum strength of 63 GPa [5]. Peng et al. [6] measured the strength of CNTs using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), revealing strengths as high as 110 GPa. Therefore, CNTs are considered one of the ideal reinforcing materials for AMMCs, offering excellent mechanical and functional properties [7,8,9]. CNT-reinforced AMMCs are considered one of the future lightweight and high-performance materials. The density, mechanical and chemical compatibility, and thermal stability of reinforcing materials are key factors affecting the metal matrix composites. The morphology of reinforcing materials can be diverse, such as fibrous, tubular, thin, or granular. CNTs are widely used as reinforcing materials for metal substrates.

Owing to the special synergistic effect of the unique properties of CNTs and AMMCs, many researchers have focused on the preparation of CNTs/AMMCs for various specialized structures. In most cases, a small amount of CNTs significantly enhances the strength of AMMCs [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. For instance, the invention patent CN107267811A [17] reveals a modified CNT-reinforced AMMCs and its preparation method. This modified CNTs/AMMCs comprises the following components: CNTs 13.2–19.5 wt%, Ag 2.9–5.6 wt%, Cu 2.1–6.3 wt%, Au 0.02–0.11 wt%, B 0.2–1.3 wt%, graphite 1.3–6.5 wt%, SiC 1.2–3.5 wt%, with the remainder being aluminum. The composition of these AMMCs maintains excellent mechanical properties while also providing good electrical properties. The density, mechanical and chemical compatibility, and thermal stability of reinforcing materials are key factors affecting metal matrix composites. The reinforcement mechanism of CNTs in AMMCs enhances the strong adhesion between the material and matrix material, resulting in effective load transfer. In addition, there are also strengthening and toughening mechanisms such as fine grain strengthening, dislocation strengthening, and dispersion strengthening. The improvement of compressive strength of CNT-reinforced AMMCs is due to the strong interfacial bonding between CNTs and AMMCs, which ensures effective transfer of load from softer aluminum matrix materials to CNTs, a strong reinforcing material. In addition, the significant increase in hardness of CNT-reinforced AMMCs may be due to grain refinement, increased dislocation density, work hardening, and increased density [18,19,20,21].

However, a higher reinforcement content can increase the brittleness of the composites. To fully leverage the effectiveness of CNTs as reinforcement in AMMCs, it is crucial to ensure that the CNTs are evenly dispersed within the matrix and that there is a coherent interface between CNTs and the matrix. There are several preparation processes for AMMCs reinforced with CNTs, including traditional melt processing methods [22,23], plasma spraying [24], friction stir processing [25], powder metallurgy [26], powder rolling [27,28], and molecular-level mixing methods [29,30]. The traditional melting treatment of CNTs and ANNCs is primarily limited by thermodynamics, structural damage to CNTs, formation of high-temperature carbides, and poor wettability between AMMCs and CNTs [31,32]. Additionally, friction stir welding and powder metallurgy processes, such as high-energy ball milling and spark plasma sintering (SPS), have demonstrated high efficiency in the preparation of AMMCs [33,34,35,36].

By adjusting the preparation process parameters and the content of CNTs, both the strength and formability of AMMCs can be improved simultaneously [37,38]. The weight percentage of CNT reinforcement in the matrix has a significant impact on the performance of AMMCs. With the development of relevant theories, models, and preparation processes, it is gradually possible to design and precisely control the microstructure of CNTs/AMMCs at different scales, such as nanoscale, microscale, and macroscopic, which is expected to further promote the development of this material. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to explore the effects of CNT type, content, and properties on the mechanical properties of CNTs/AMMCs. This includes investigating various aspects such as tensile performance, compressive performance, stress–strain curve behavior, elastic modulus, hardness, creep, and fatigue behavior and making prospects for urgent problems and future development in this field.

2 Structure and properties of CNTs

2.1 Structure of CNTs

CNTs are composed of curved carbon monolayers, typically categorized into two types based on their structures: single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). The CNTs first observed in 1991 were actually MWCNTs. A few years later, SWCNTs were successfully synthesized [39,40,41]. Depending on their rolling directions, three distinct types of SWCNT structures can be achieved, including armchair structure, Z-shaped structure, and chiral structure, as illustrated in Figure 1.

![Figure 1

Structures of different types of CNTs. The chiral vector denotes different types of nanotubes. Reproduced by Sanginario et al. [41] with permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry.](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2024-0009/asset/graphic/j_secm-2024-0009_fig_001.jpg)

Structures of different types of CNTs. The chiral vector denotes different types of nanotubes. Reproduced by Sanginario et al. [41] with permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry.

2.2 Properties of CNTs

The SP2 hybridization of the carbon–carbon (C–C) bonds in CNTs imparts exceptional characteristics to these materials. With a density of only 1.3 g/cm³ [42], CNTs are considered an ideal reinforcing material for aluminum matrices. A comparison of certain properties of CNTs with those of common engineering materials is presented in Table 1 [43].

Comparison of mechanical properties and thermal conductivities between CNTs and other common materials

| Materials | Properties | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific density (g/cm3) | Tensile strength (GPa) | Young’s modulus (GPa) | Thermal conductivity (W/m K) | ||

| SWCNTs | 1.35–2.1 | 80 | 1,000 | 3,000 | [44] |

| MWCNTs | 2.6 | 60 | 800 | 3,000 | [45] |

| Carbon fiber | 1.8 | 3,000 | 300 | 180 | [44] |

| Diamond | 3.52 | 20 | 1,140 | 2,200 | [46] |

| Graphite | 2.25 | 0.2 | 8 | 1,900 | [47] |

| Graphene | 1.01 | 130 | 1,000 | 1,000 | [48] |

| Wood | 0.6 | 0.008 | 16 | 0.14 | [44] |

Note: The actual data and details of Table 1 would typically include specific properties such as the tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, and thermal conductivity of CNTs compared to other materials like steel, aluminum, etc., but this information needs to be provided or referenced from the relevant source [44] for accuracy.

3 Influence of CNTs on the mechanical properties of AMMCs

The concentration and properties of CNTs are the crucial factors influencing the mechanical properties of CNTs/AMMCs. By incorporating CNT reinforcements, the mechanical properties of CNTs/AMMCs can be enhanced through load transfer, Orowan mechanism, thermal mismatch, and shear lag mechanism.

3.1 Tensile properties

Previous studies [24,49–51] have shown that, compared to pure aluminum, the optimal toughness and tensile strength of the composite are achieved when the CNT content is around 2 wt%. This represents the peak in mechanical enhancement, with the highest levels of toughness and tensile strength observed. When the CNT content exceeds this 2 wt%, the strength of the composites begins to decrease. This trend is attributed to the role of CNTs in strengthening the composite. The addition of CNTs beyond the optimal threshold likely leads to issues such as agglomeration or poor dispersion within the matrix, which negatively impacts the overall strength of the material.

The Young’s modulus obtained from tensile tests of CNT-reinforced AMMCs is illustrated in Figure 2. When CNT content increases from 1 to 5%, the elastic modulus of the composites rises from 70 to 110 GPa. However, it has also been reported that adding CNTs could reduce the elastic modulus of the composite [24]. This reduction is attributed to poor dispersion in the powder and the formation of large CNT clusters in the final microstructure. The increase in Young’s modulus is more pronounced for pure aluminum matrices than for aluminum alloy matrices. As the CNT content increases, the rate of stiffness increases, primarily due to the formation of CNT clusters and reduced load transfer efficiency to individual CNTs at higher CNT loads. Some studies have reported Young’s moduli higher than these predicted values for two reasons: first, the elastic modulus of CNTs is greater than 1,000 GPa, and second, the formation of alumina during processing can further increase stiffness. Compared to pure aluminum, the addition of CNTs increases the modulus of the composites. Deng et al. [52] demonstrated that the modulus of a 2024Al substrate was significantly improved by adding a certain amount of CNTs. At 2 wt% CNT content, the estimated elastic modulus increases by 23%. However, at 5 wt%, the elastic modulus decreases, yet it remains 20% higher than that of pure aluminum. The stiffness of CNTs/AMMCs produced by plasma sputtering is increased by 40% [53]. In the elastic region, CNTs enhance the flexibility of nanocomposites by maintaining the flexibility energy. The increase in modulus is largely due to the load transfer from the AMMCs to the CNTs [54].

To strengthen the interface bonding between the aluminum matrix and CNTs, several effective methods have been developed to control the interface structure. These include the in situ formation of Al4C3 between the aluminum matrix and CNTs [55], CNT coating [56], and CNT etching [57]. Zhang et al. [56] confirmed that the tensile strength of composites reinforced with 1 vol% CNTs could reach 50 MPa by coating the SiC layer formed in situ on the CNTs.

Despite considerable efforts, the service performance of CNTs/AMMCs still falls short of some industrially used aging aluminum alloys, such as the AA7075-T6 alloy. However, the addition of CNTs can enhance certain aspects of the aluminum matrix. For instance, the incorporation of CNTs promotes the formation of stacking faults within the aluminum matrix, which can improve the strain-hardening capability and modulus of the material, delay crack formation, growth, and fracture, and ultimately enhance its mechanical properties.

Density functional theory (DFT) simulations indicate that as the volume percentage of CNTs increases from 0.5 to 1.0 vol%, the stacking fault energy of the aluminum matrix decreases, and the density of stacking faults increases [58]. When CNTs are uniformly dispersed and exhibit good interface bonding with Al–1 vol% CNTs, the peak tensile strength (378 ± 8 MPa) and good ductility (17.1 ± 1.5%) are achieved. The primary mechanisms for strengthening in CNTs/AMMCs are attributed to Orowan looping and stacking fault strengthening.

At elevated temperatures, specifically at 400°C, the strength of CNTs/AMMCs increases with the CNT content up to 5 vol%. Notably, CNTs/AMMCs demonstrate a more pronounced reinforcing effect at high temperatures compared to room temperature [59]. This implies that CNTs/AMMCs might have specific applications where high-temperature strength is a critical factor.

3.2 Yield strength

Choi and Bae [60] found that the addition of CNTs increased the yield strength of CNTs/Al composites compared to pure aluminum. The study by Bustamante et al. showed that due to the dispersion strengthening mechanism of CNTs, the yield strength of CNTs/AMMCs was significantly improved when the content of CNTs increased to 0.75 wt%. Compared to unreinforced aluminum, an Al-2 wt% CNT composite shows a 26% increase in yield quality. However, the expansion of CNTs in the composite leads to a reduction of about 46% in fracture strain compared to pure aluminum. It is noteworthy that the yield strength values reported in various studies show considerable variation. This disparity is largely attributed to differences in processing routes. In the literature, the diameter of CNTs ranges from 20 to 140 nm. Due to the small size of CNTs, dislocations cannot penetrate through them, making the Orowan ring mechanism a feasible method for strengthening.

The aspect ratio of CNTs significantly affects the mechanical properties of CNTs/AMMCs. The addition of just 0.5 wt% CNTs can notably enhance the strength of Al composites without any loss of plasticity in hot extrusion. With a CNT content of 1.0 wt%, the CNTs are uniformly distributed within the aluminum matrix, significantly improving both strength and hardness. The primary strengthening mechanism in CNTs/AMMCs is believed to be dispersion strengthening [61]. CNTs of different lengths can effectively utilize both load transfer and Orowan strengthening mechanisms. Long CNTs primarily contribute to load transfer strengthening, while short CNTs predominantly facilitate the Orowan strengthening mechanism [62].

3.3 Compressive strength

Experimental studies [36,38,63–72] have demonstrated that adding different contents of CNTs to AMMCs can achieve higher compressive strength. When the CNT content is 1.6 vol%, the compressive strength of the CNTs/AMMCs increases by 350% [65]. Compression tests conducted at various temperatures for different strain percentages help analyze the material’s resistance to deformation. Table 2 provides a summary of the influence of CNTs on the strength of AMMCs. The patent CN110669956A [66] introduces a method for preparing a CNT-reinforced aluminum matrix composite coated with alumina. The alumina coating on the aluminum matrix endows the material with superior comprehensive mechanical properties. The yield strength at room temperature exceeds 320 MPa, the tensile strength surpasses 440 MPa, elongation is greater than 20%, and electrical conductivity is significantly enhanced. Compared to pure aluminum, the addition of CNTs greatly improves the compressive strength of AMMCs, yet the elongation of the composites remains unchanged, indicating excellent comprehensive mechanical properties.

Tensile results of CNTs/AMMCs

| Ref. | Preparation method | CNT content (wt%) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [36] | CVD + mechanical alloying + hot extrusion | 4.5 | 420 | 5.3 |

| [69] | Mechanical alloying + vacuum sintering + hot extrusion | 2.0 | 252 | 15.6 |

| [38] | Mechanical alloying + extrusion + annealing | 5.0 | 250 | — |

| [70] | SPS + hot extrusion | 3.4 | 194 | 10.1 |

| [71] | CVD + sintering | 5.0 | 398 | 2.2 |

The reinforcing effectiveness of CNTs in AMMCs diminishes with an increase in temperature and a decrease in the loading rate. This trend suggests that the contribution of CNTs to the overall strength of the composite is temperature and strain rate dependent. CNTs play a significant role in impeding dislocation movement and stabilizing the microstructure of the composite. Consequently, CNTs/AMMCs can exhibit enhanced strength at temperatures up to 603 K (330°C), regardless of the loading rate applied. When compared to standard AMMCs, those reinforced with CNTs demonstrate a higher sensitivity to strain rate and a lower activation volume across all tested temperatures [68]. This indicates that CNTs/Al composites respond more distinctly to changes in strain rate, suggesting a more complex interplay of mechanical behaviors at the nanoscale. These properties highlight the potential of CNTs/Al composites in applications where materials are subjected to varying temperatures and loading conditions, as they provide improved performance characteristics under these conditions. Figure 3(a) and (b) show the typical true stress–true strain compressive curves for 7055Al alloy and CNTs/7055Al composite at 400°C with a 0.01 1/s strain rate, prepared using high-energy ball milling and powder metallurgy methods. It is observed that the flow stress of both materials decreases with increasing temperature or decreasing strain rate, and the stress in the CNTs/7055Al composite is higher than that in the 7055Al alloy matrix, indicating that CNTs still have a strengthening effect at high temperature [72].

![Figure 3

Stress–strain curves of 3 vol% CNTs/7055Al (a) at 400°C and (b) at a strain rate of 0.01 1/s [72].](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2024-0009/asset/graphic/j_secm-2024-0009_fig_003.jpg)

Stress–strain curves of 3 vol% CNTs/7055Al (a) at 400°C and (b) at a strain rate of 0.01 1/s [72].

3.4 Stress–strain curve of CNTs/AMMCs

The adoption of a bimodal structure design, which involves uneven reinforcement or grain size distribution, has been identified as a potentially effective method to enhance both strength and ductility in CNTs/AMMCs and other ultrafine-grained composites.

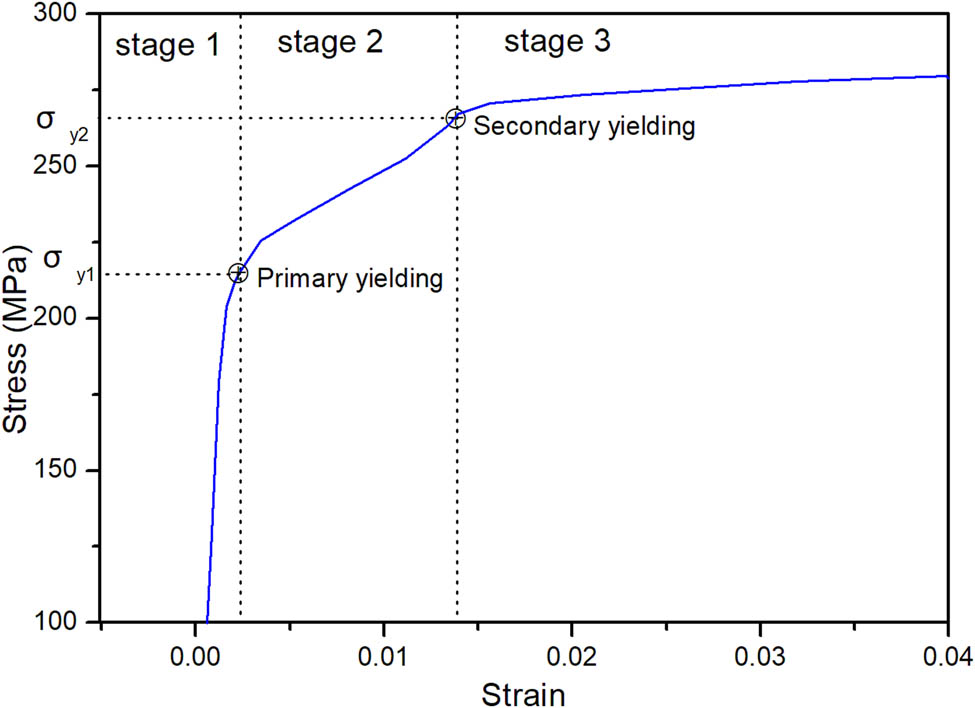

The mechanical properties of bimodal materials vary significantly between different regions. This variation can lead to uneven flow during thermal deformation, potentially deteriorating the material’s deformation capacity. However, by optimizing deformation temperature and strain rate, the compatibility of deformation across different regions can be effectively improved [73]. The stress–strain curve of CNT-reinforced metal matrix composites typically consists of three stages, as depicted in Figure 4. The first stage involves elastic deformation up to the yield point; in the second stage, the composites continue to stretch elastically due to the high yield strength of CNTs. The third stage is marked by plastic deformation occurring at the second yield point. Due to the presence of crack bridging, the stress–strain behavior includes three parts: the matrix elastic deformation zone, the CNTs pull-out zone, and the CNTs fracture zone. Although the aggregation of CNTs can lead to fracture, they also act as fracture inhibitors [34].

Double-yield phenomenon of CNTs/AMMCs.

It is inferred that the dual deformation behavior in CNTs/AMMCs results from different microstructures promoting different load transfers between regions. Figure 5 illustrates the true σ–ε (stress–strain) curve for unreinforced aluminum and composite specimens [34]. With an increase in CNT content, the yield resistance increases, but the work-hardening effect is negligible. Results indicate that the yield strength (σ y) and tensile strength (σ T) are 456 and 571 MPa, respectively. When the CNT content exceeds 2 wt%, additional CNTs do not positively affect the composite [61]. Tensile test results reveal that the strength of CNTs/Al composites significantly increases while elongation markedly decreases [69]. Evidently, increasing the volume fraction of CNTs in pure aluminum reduces the elongation of the resulting CNTs/Al composites [74].

![Figure 5

True stress–true strain behavior of CNTs/AMMCs. The experimental data in the figure are sourced from the study of Yoo et al. [34].](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2024-0009/asset/graphic/j_secm-2024-0009_fig_005.jpg)

True stress–true strain behavior of CNTs/AMMCs. The experimental data in the figure are sourced from the study of Yoo et al. [34].

With the addition of CNTs, the tensile strength of the CNTs/Al-Mg-Sc-Zr composites increased from 382.2 ± 8.1 to 409.4 ± 5.4 MPa. This enhancement is attributed to the significant promotion of precipitation secondary Al3(Sc,Zr) nanoparticles by heat treatment and the complete conversion of the CNTs into Al4C3 nanorods. The formation of a strong and stable Al4C3/Al interface to replace the relatively weak CNTs/Al matrix interface provides higher load transfer efficiency during deformation [75]. Additionally, the ability of MWCNTs to effectively refine the grain size of the aluminum matrix also contributes to the improved strength of the nanocomposites through grain refinement. The patent CN104532085A describes AMMCs reinforced with 0.05–5.0 wt% CNTs, which AMMCs containing 0.5–5.0 wt% Zn, with a mass ratio of Cr to Zn of 1:4–8. The elongation of these CNTs/AMMCs ranges from 19 to 22% [76]. Patent CN106555093A discloses the composition of CNTs/AMMCs containing 0.5–2% CNTs, 40–60% SiC particles, and the remainder being aluminum powder. The plasticity of these composites has increased by 5–10% [77].

These studies demonstrate that the mechanical properties of aluminum-based alloys, such as tensile strength and plasticity, can be significantly enhanced through the appropriate incorporation of nanomaterials like MWCNTs and CNTs, combined with heat treatment processes. These advancements are crucial for industries requiring lightweight and high-strength materials, such as aerospace and automotive manufacturing.

3.5 Hardness

Srivastava et al. [78] reported a significant increase in the hardness of CNTs/AMMCs with the addition of CNTs. Kwon and Leparoux [79] found that adding just 1 vol% of CNTs to aluminum can significantly improve its hardness, up to three times higher than that of pure aluminum. Observations indicate that the hardness of CNTs/AMMCs increases with the addition of less than 1.5 wt% CNTs, but generally decreases with further increases in CNT content. The hardness improvement is mainly due to the strengthening effect of CNTs [80,81].

MWCNTs were prepared using chemical catalytic vapor deposition, and catalysts containing cobalt and magnesium were prepared using the sol–gel method. Christopher and his team [82] found that the maximum hardness of 6 wt% MWCNTs/AMMCs was 151 MPa. Experimental results [83] show that the hardness of CNTs/Al composites, prepared by pressureless infiltration, increases with the addition of CNTs but decreases with a further increase in CNT content. It has also been shown that CNTs/Al composites with a 4.5% concentration of CNTs exhibit the highest tensile strength and hardness [36].

When the weight percentage of CNTs in Al6061 alloy increases from 1 to 2 wt%, the hardness escalates from 19.58 to 32.88 HV, marking a 68% increase, as shown in Figure 6. This increase is attributed to the presence of a hard phase in the Al6061 composites, with hard CNT particles inducing density dislocation during compaction, leading to further strain hardening [36]. After adding 2% CNTs, the microhardness of CNTs/Al with a nanostructure was substantially improved, reaching 800 MPa, approximately five times that of pure Al (170 MPa). This remarkable enhancement in mechanical properties is mainly due to the fine-grain strengthening effect [84,85].

![Figure 6

Hardness of with and without CNTs. Experimental data are sourced from the study of Yang et al. [36].](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2024-0009/asset/graphic/j_secm-2024-0009_fig_006.jpg)

Hardness of with and without CNTs. Experimental data are sourced from the study of Yang et al. [36].

These findings highlight the significant role of CNTs in enhancing the hardness and overall mechanical properties of AMMCs, making them highly suitable for various high-strength applications.

3.6 Creep properties

Creep is considered a time-dependent deformation mechanism, and before creep fracture, the normal creep process usually goes through three stages: primary creep, steady-state creep, and creep fracture. The development of material creep is related to parameters such as temperature, time, stress, alloy microstructure, and composition. Strengthening non-shear second-phase CNTs into AMMCs can improve its creep resistance by reducing load transfer and dislocation activity at the matrix reinforcement interface. Choi and Bae studied the creep properties of CNT/AMMC composites at 523 K and observed improved creep properties at a pressure of 200 MPa, as reported by Choi and Bae [86]. They found that in the medium pressure region (σ < 110 MPa), the strain rate showed little dependence on the stress. Figure 7(a) in their study presents a typical step load creep curve for ultra-fine grain (UFG) MWCNTs/Al composites, illustrating an evident secondary creep stage under various stresses. However, the extent of this stage in the composites is limited due to the debonding of the CNT reinforcement. Figure 7(b), as shown in their research [86], displayed a typical step strain rate curve for UFG aluminum and composites. The reduction in grain size from micron to UFG resulted in a significant increase in the step height of the strain rate, defined as strain rate sensitivity (where σ is the flow stress and the strain rate). This increase may originate from low-density dislocations in the lattice of small grains. Moreover, Figure 7(c) in the same study [86] showed the double logarithm plots of stress versus creep rate (obtained from step load creep test by power law equation) or strain rate (obtained from step strain rate test) for UFG aluminum and UFG MWCNTs/Al composites, as well as Al–6Mg–1Sc–1Zr–10 vol% SiC composites. When the volume fraction of CNTs is at 4.5%, the yield stress of the composite increases by approximately 70 MPa, surpassing that of Al–6Mg–1Sc–1Zr–10 vol% SiCp composites. This enhancement in flow stress may be due to the superior stiffness and yield stress of MWCNTs.

![Figure 7

(a) The strain–time curve during a step load creep test, which is critical for understanding the creep behavior of these materials under a constant load over time. (b) Stress–strain curves during step strain rate tests, offering insights into how the materials deform under varying stress levels. (c) Creep properties with double logarithmic plots of stress as a function of minimum creep rate (obtained from step load creep tests by the power-law equation) or strain rate (obtained from step strain rate tests). This plot is particularly informative in comparing the creep behavior of UFG aluminum, the UFC MWCNTs/Al composite, and 10 vol% SiC/Al6Mg1Sc1Zr composite [86].](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2024-0009/asset/graphic/j_secm-2024-0009_fig_007.jpg)

(a) The strain–time curve during a step load creep test, which is critical for understanding the creep behavior of these materials under a constant load over time. (b) Stress–strain curves during step strain rate tests, offering insights into how the materials deform under varying stress levels. (c) Creep properties with double logarithmic plots of stress as a function of minimum creep rate (obtained from step load creep tests by the power-law equation) or strain rate (obtained from step strain rate tests). This plot is particularly informative in comparing the creep behavior of UFG aluminum, the UFC MWCNTs/Al composite, and 10 vol% SiC/Al6Mg1Sc1Zr composite [86].

In regions of high-stress concentration (σ > 200 MPa), the creep elongation of the composite shows a high-stress index, as highlighted by Choi and Bae [86]. With a decrease in the load, the contribution of line defects to creep elongation decreases, leading to increased dispersion and a reduction in the stress exponent. The addition of 1 vol% CNTs effectively improves the tensile ductility of aluminum matrix composites at high temperatures by increasing the strain-hardening ability of CNTs/AMMCs and delaying the recovery rate [87]. The tensile ductility of composite materials increases with the increase in strain rate due to a decrease in the spacing between CNTs, an increase in creep threshold stress, and an increase in strain rate sensitivity at high strain rates.

3.7 Fatigue properties

The decline in the safety performance of materials used in vehicle and aviation foundations is often attributed to fatigue performance. CNTs/AMMCs, while exhibiting high strength, are susceptible to fracture or complete failure under alternating loads after a certain number of cycles. However, the addition of CNTs has been shown to significantly improve the fatigue properties of AMMCs, as indicated by Coble [88]. Carvalho et al. [89] conducted tensile fatigue tests with a stress ratio of R = 0.1 and a frequency of 16 Hz. The results of these tests are presented in Figure 8. This figure illustrates the fatigue test outcomes for a 2 wt% CNTs/AlSi composite. Notably, the number of stress cycles sustained by this composite was higher than that of unreinforced AlSi, indicating enhanced durability. When compared to the unreinforced AlSi alloy, the 2 wt% CNTs/AlSi composite demonstrated superior performance, as shown in Figure 8. Specifically, the fatigue strength of the composite increased by 270% [89].

![Figure 8

Maximum stresses versus cycles to failure for AlSi with and without CNTs. The experimental data is sourced from the study of Carvalho et al. [89].](/document/doi/10.1515/secm-2024-0009/asset/graphic/j_secm-2024-0009_fig_008.jpg)

Maximum stresses versus cycles to failure for AlSi with and without CNTs. The experimental data is sourced from the study of Carvalho et al. [89].

This remarkable increase in the fatigue strength can be attributed to two key mechanisms: crack bridging and CNTs pull-out. Crack bridging helps to distribute the stress across the crack, reducing the stress intensity at the crack tip and hence slowing down the crack propagation. On the other hand, the CNT pull-out mechanism provides energy dissipation during the fatigue process, contributing to the increased fatigue life of the composite. These mechanisms make CNT-reinforced composites particularly valuable in applications where materials are subjected to cyclic loading and high-stress conditions.

Liao et al. [90] performed fatigue tests under tensile load with a stress ratio of R = 0.1 and a frequency of 5 Hz. Their research highlighted that the addition of CNTs enhances the material’s resistance to damage under cyclic loading. It was observed that as stress fluctuates, the service life of the material decreases with increasing stress levels. However, the incorporation of CNTs into the material increases the number of loading cycles it can withstand. Similarly, Shin and Bae [7] studied the fatigue properties of Al2024 alloy reinforced with MWCNTs. They conducted fatigue experiments with a stress ratio of R = −0.5 and a frequency of 5 Hz. Their findings revealed that the number of cycles to failure for MWCNTs/2024Al composites increases with the addition of more CNTs. Notably, there was a significant increase in fatigue strength to 600 MPa at 2.5 × 106 cycles, indicating that CNT-reinforced composites possess higher fatigue strength. Figure 9, referenced in previous studies [91,92], illustrates the relationship between the maximum stress of MWCNTs/2024Al composite and the number of failure cycles. At any given number of cycles, the maximum stress that can be withstood due to the addition of CNTs is much higher than that of the pure 2024Al alloy. Additionally, the maximum stress increases with the increase in CNT content. While the fatigue life of MWCNT-reinforced composites decreases with the increase of applied stress, it increases significantly under high-stress levels. When the composite is subjected to fluctuating loads, the inconsistency in deformation between the matrix lattice and the reinforcing fibers causes drawing and acts as a crack bridge joint. This mechanism contributes to the increase in the number of fatigue cycles as the CNT content in the composite increases, as discussed in previous studies [93,94]. Thus, CNTs effectively strengthen AMMCs, enhancing their durability and suitability for high-stress applications.

The CNTs/7055Al composite exhibits a distinctive bimodal structure, characterized by ultra-fine crystalline regions that are rich in CNTs and coarse crystalline bands where CNTs are absent. After enduring 107 fatigue cycles, the CNTs/7055Al composites displayed the formation of dislocation cells, entanglement, and subgrain structures. The load transfer effect promoted by the CNTs significantly improved the fatigue strength of CNTs/7055Al, increasing from 350 to 400 MPa, and the number of cycles reached 107. The predominant damage mechanism observed in the CNTs/7055Al composites was mainly strain localization, as discussed in the study of Bi et al. [95]. Similarly, the bimodal 2009Al-based alloy and CNTs/2009Al composites demonstrated basic cyclic stability during cyclic deformation. The CNTs/2009Al nanocomposites were capable of maintaining high cyclic stress levels across all applied strain amplitudes. Additionally, these nanocomposites exhibited excellent fatigue life at low strain amplitudes, attributed to their high monotonic strength, as reported in the study of Mohammed et al. [96].

These findings underscore the significant impact of CNTs on enhancing the mechanical properties of aluminum composites, particularly in terms of fatigue strength and cyclic stability. The presence of CNTs not only contributes to an increase in fatigue strength but also aids in maintaining stability under cyclic loading conditions, making these materials highly suitable for applications where endurance and reliability are critical.

3.8 Fracture strain and toughness

Previous studies [97,98] indicate that AMMCs with more than 3 vol%. CNTs exhibit a failure strain more than 60% lower than that of pure aluminum. This significant reduction in the failure strain of the aluminum alloy matrix is attributed to the challenges associated with dispersing CNTs within the aluminum alloy. For both pure aluminum and aluminum alloy matrices, toughness decreases as the CNT content increases. In CNTs/Al composites, lower CNT contents (<2 vol%) are associated with higher toughness. However, when the CNT content exceeds 3 vol%, the toughness of both pure aluminum and aluminum alloys diminishes. This trend suggests that regardless of the dispersion quality of CNTs in the aluminum matrix, an increase in CNT content leads to increased brittleness of the material. While the addition of CNTs enhances strength and stiffness, it also reduces the plasticity and toughness of the materials.

In CNT-reinforced composites, the bridging connections of CNTs play a crucial role in resisting fracture by disrupting the propagation of cracks. As the fracture progresses, CNTs are pulled out from the lattice due to friction, which helps to inhibit further fracturing [16]. This implies that the friction force on CNTs can drive some CNTs to bridge and pull out during stress fluctuations. Small pores are often found in the damaged areas, and the carbon concentration near the fracture is usually high due to CNTs contacting the fracture surface. In matrices with high CNT content, wide cracks are visible near the fracture zone. In regions where CNTs contact the crack surface (length more than 20 mm), some CNT-containing areas act as joints on the fracture interface. The fracture in 2024Al-CNTs is often influenced by the matrix elongation, with the fracture path crossing the direction of the applied force. The primary driver of fatigue fracture in metal matrix composites is the initiation from both large-scale and small-scale cracks. These full-size and tiny voids are a result of weak interfaces between the reticular structure and the reinforcement. Consequently, mode I crack is a predominant fracture mode in many composites, where the axial stress perpendicular to the fracture zone drives the fracture along a conventional external load path. However, particle pull-out can negatively impact mechanical properties due to poor maintenance of the interface between particles and the matrix [99–101]. On the other hand, particle pull-out can significantly enhance fracture diffusion and crack-bridging performance [102–104].

Patent CN110724842 (A) [105] reveals a high toughness CNT-reinforced AMMCs with a non-uniform structure and its preparation method. The toughness of this composite is notably higher than that of other composite materials with a uniform structure. In this composite, CNTs adhere to the substrate, resulting in additional lattice elongation and enhancing fatigue protection by controlling fracture elongation. The superior quality and flexibility of CNTs make the fatigue mass of the strengthened 2024Al lattice larger than that of unreinforced 2024Al [17]. It is hypothesized that particle-reinforced metal matrix composites benefit from the uniform dispersion of particles and strong adhesion. When these composites are subjected to permanent tension, the particles bear the stress within the mesh until they break without pulling out. However, under alternating loads, any aluminum matrix composite will undergo particle stretching. The vibration can cause CNTs to hinder fracture and lead to crack propagation. As the crack propagates, the pulling out and sliding of CNTs consume energy, thereby reducing the propagation rate of microcracks. Thus, CNTs act as a connector of the crack under vibration, increasing strain intensity [17].

Crack deflection is a common phenomenon in aluminum matrix composites. In regions with uniformly dispersed CNTs, intergranular cracks appear in the aluminum matrix and propagate along the crystal structure of the material, leading to intergranular fracture. Therefore, the fracture modes of CNTs/AMMCs include intragranular fracture and intergranular fracture. Intergranular fracture primarily results from defects within the aluminum grains, where the fracture direction passes through the aluminum grain, accompanied by significant elongation. This detailed understanding of fracture mechanisms in CNT-reinforced aluminum matrix composites provides valuable insights for enhancing the durability and toughness of these advanced materials.

The composite material CNTs/7055Al-E prepared by extrusion exhibits a structure composed of coarse and fine particles. In contrast, the composites designated as CNTs/7055Al-ER, which were hot rolled after extrusion, developed a uniform UFG structure. Notably, the hot rolling process did not cause further structural damage or aggregation of the CNTs. Compared to CNTs/7055Al-E, the elongation of CNTs/7055Al-ER increased by two times, although there was a slight decrease in strength. The mechanism of improving mechanical properties is related to the grain refinement and improved grain orientation of the composite material after adding CNTs [106].

CNTs/Al-Mg composites with both uniform and bimodal grain structures were developed through a powder assembly process. For the bimodal CNTs/Al-Mg composites, which contained 25% coarse grain, the elongation increased from 4.2 to 5.2% compared to the homogenous structure. This improvement was a result of the activation of various dislocation mechanisms, leading to higher strain hardening ability, as explained in the study of Fu et al. [107].

Compared to pure aluminum, the addition of CNTs enhances the strength of AMMCs and improves the strain rate sensitivity. Under dynamic loads, both the strength and elongation at break of the material increase due to the heightened strain hardening rate. The long-range back stress of dislocation at the CNTs interface and the geometrically necessary dislocations accumulated along the interface strain gradient are considered the main mechanisms of strain hardening in CNTs/Al [108].

Furthermore, interface bonding and structure are critical factors that influence the mechanical properties of CNT-reinforced AMMCs. To enhance interfacial bonding, CNTs/AMMCs were prepared by modifying CNTs with copper nanoparticles. This approach significantly improved the strength and ductility of CNTs/AMMCs. The copper nanoparticles aid in repairing structural defects of CNTs, passivating the reactivity of defect sites, and inhibiting the formation of a large Al4C3 phase. Additionally, serving as a bridge between aluminum and CNTs, copper nanoparticles improve interfacial wettability and create an “aluminum-copper-CNTs” interlocking effect, as reported in reference [109]. These advancements highlight the ongoing innovations in the development of CNT-reinforced composites, focusing on optimizing their mechanical properties for various industrial applications.

3.9 In situ tensile and nano-mechanical properties

Boesl et al. prepared CNTs/AMMCs using SPS at 500°C and 80 MPa [110]. They observed that increasing the CNT content from 3 to 5.5% led to an increase in tensile strength from 68 to 95.5 MPa, closely aligning with the calculated values of 90–100 MPa. Tensile test results indicated that fiber reinforcement is a key mechanism in CNTs/AMMCs [111].

Chen et al. [112,113] and Zhou et al. [114] analyzed the interface phenomena, interfacial shear strength, and fracture morphology of CNTs/AMMCs during in situ tensile tests. They found that the pull-out of CNTs is a primary failure mechanism in these composites. When CNTs peel off, effective load transfer between the walls of CNTs leads to interaction between the defective structure and CNTs, resulting in crack propagation.

It was also determined that higher interfacial strength can be achieved by pulling CNTs out of AMMCs. Various mechanisms contribute to the pull-out of CNTs in AMMCs, including load transfer, grain refinement through the pinning effect of CNTs, solid solution strengthening by CNTs, strengthening by in situ formed or precipitated carbides, and thermal mismatch between CNTs and the matrix [115]. An in situ scanning electron microscope (SEM) study revealed that when a single CNT was pulled from the fracture surface, the inner core of MWCNTs was pulled away, leaving the shell fragments in the matrix under tension, resembling a “scabbard” fracture mode [115].

Nanoindentation is utilized as a rapid evaluation tool for mechanical properties. This technique efficiently calculates tensile properties, although it’s noted that the hardness and elastic modulus of CNTs/AMMCs studied by nanoindentation methods often yield values higher than those obtained from macroscopic tests without considering the effects of porosity and CNT clusters. Bakshi et al. prepared CNT-reinforced Al–12%Si eutectic alloy coating on steel pipes using plasma spraying technology [53]. The analysis of nanoindentation load-displacement curves indicated a compressive strength of 20 GPa and a tensile strength of 120 MPa. This discrepancy is attributed to the presence of CNT clusters, which lead to poor wettability and lack of penetration of the molten metal, behaving similarly to porosity. The effects of CNT clusters and grain boundary oxide particles are best determined through nanoindentation tests. In situ tensile tests showed that the yield strength of 1 vol% CNTs/Al composite is 263 MPa, significantly higher than the 78 MPa for pure Al. The mechanical properties of the composites, such as hardness and elastic modulus, obtained by nanoindentation tests were found to be similar to those obtained by tensile tests [79].

4 Conclusions and prospect

The enhancement of the CNTs/AMMCs interface is essentially a process of load transfer from the aluminum matrix to the reinforced CNTs. Due to the dispersion and bending characteristics of CNTs, this research primarily focuses on four parameters, the geometric parameters of the raw materials, processing technology, processing environment, and modified interface, to achieve optimal interface strength. CNTs/AMMCs with more loading layers, longer outer layers, larger diameters, and less than 2% volume fraction tend to exhibit higher strength. Additionally, smaller initial particle sizes lead to a better enhancement effect of CNTs.

The primary challenges in developing CNT-reinforced AMMCs are multifaceted:

Quality of CNTs: Producing high-quality, defect-free, and functional CNTs suitable for composite materials is crucial.

Uniform dispersion: Achieving uniform dispersion of CNTs in AMMCs at concentrations above 6 vol% while maintaining their structural integrity is a significant challenge. The design concept of integrating material plain and functional unit ordering further optimizing the composition and microstructure design of CNTs/AMMCs requires further in-depth research [116,117].

Processing conditions: The reduction of CNTs during processing at higher temperatures and/or pressures is a technical hurdle.

Wettability improvement: Further research is needed to improve the wettability of molten AMMCs with CNTs. Based on bionic design concepts, novel gradient structures, layered structures, and multi-level twin structures are designed to achieve controllable preparation of CNTs/AMMCs.

To achieve industrialization goals at the lowest cost, standardization of the above parameters is necessary. Dispersion of CNTs remains the biggest challenge in achieving high strength. A controllable interfacial reaction method is needed to manage the reasonable distribution of CNTs within the matrix. Methods to enhance the wettability and dispersion of CNTs in the aluminum melt are crucial for realizing large-scale production of components by melting processes.

Additionally, to improve the durability of CNTs/AMMCs, studies on corrosion, stress corrosion cracking, and fatigue performance evaluation are essential. It is crucial to establish new multi-scale models using data design methods, such as machine learning, to analyze the effects of interface, CNT dispersion, and CNT morphology on the strength and toughness of AMMCs in order to bridge the gap between experimental and theoretical values. A quantitative and semiquantitative model has to be developed for microstructure parameters, service life, and damage to achieve strength toughness matching of CNTs/AMCs.

While CNT-reinforced AMMCs have made remarkable strides in various engineering applications over the past decade, new applications may still emerge and be discovered. By addressing these challenges, CNTs/AMMCs have the potential to make significant contributions to the future of sustainable development.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No.: 51304247), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2019JJ70050), and the Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Hunan Province (19C0557), and supported by program for scientific research start-up funds of Guangdong Ocean University Project No. YJR22017 and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students of Guangdong Ocean University (Grant No.: 202310566038).

-

Funding information: This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No.: 51304247), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Project No.: 2019JJ70050), and the Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities in Hunan Province (Project No.: 19C0557), and supported by the program for scientific research start-up funds of Guangdong Ocean University Project No. YJR22017 and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students of Guangdong Ocean University (Grant No.: 202310566038).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. XN: writing - original draft preparation. AB: review, editing, and revising.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

[1] Bourkhani RD, Eivani AR, Nateghi HR. Through-thickness inhomogeneity in microstructure and tensile properties and tribological performance of friction stir processed AA1050-Al2O3 nanocomposite. Composites Part B. 2019;174:107061. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107061.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Kurt HI. Influence of hybrid ratio and friction stir processing parameters on ultimate tensile strength of 5083 aluminum matrix hybrid composites. Composites Part B. 2016;93:26–34. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.02.056.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Iijima S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature. 1991;6348:56–8. 10.1038/354056a0.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Xie S, Li W, Pan Z, Chang B, Sun L. Mechanical and physical properties on carbon nanotube. J Phys Chem Solids. 2000;61(2000):1153–8. 10.1016/S0022-3697(99)00376-5.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Yu MF, Lourie O, Dyer MJ, Moloni K, Kelly TF, Ruoff RS. Strength and breaking mechanism of multiwalled carbon nanotubes under tensile load. Science. 2000;287:637–40. 10.1126/science.287.5453.637.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Peng B, Locascio M, Zapol P, Li SY, Mielke SL, Schatz GC. Measurements of near-ultimate strength for multiwalled carbon nanotubes and irradiation-induced crosslinking improvements. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:626–31. 10.1038/nnano.2008.211.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Shin SE, Bae DH. Fatigue behavior of Al2024 alloy-matrix nanocomposites reinforced with multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Composites Part B. 2018;134:61–8. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2017.09.034.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Saadallah S, Cablé A, Hamamda S, Chetehouna K, Sahli M, Boubertakh A. Structural and thermal characterization of multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs)/aluminum (Al) nanocomposites. Composites Part B. 2018;151:232–6. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.06.019.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Chen B, Kondoh K, Li JS, Qian M. Extraordinary reinforcing effect of carbon nanotubes in aluminium matrix composites assisted by in-situ alumina nanoparticles. Composites Part B. 2020;183:107691. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107691.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Pérez-Bustamante R, Pérez-Bustamante F, Maldonado-Orozco MC, Martínez- Sánchez R. The effect of heat treatment on microstructure evolution in artificially aged carbon nanotube/Al2024 composites synthesized by mechanical alloying. Mater Charact. 2017;126:28–34. 10.1016/j.matchar.2017.01.006.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Chen B, Kondoh K, Imai H, Umeda J, Takahashi M. Simultaneously enhancing strength and ductility of carbon nanotube/aluminum composites by improving bonding conditions. Scr Mater. 2016;113:158–62. 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2015.11.011.Search in Google Scholar

[12] Zhu X, Zhao YG, Wu M, Wang HY, Jiang QC. Fabrication of aluminum matrix composites reinforced with untreated and carboxyl-functionalized carbon nanotubes. J Alloy Compd. 2000;674:145–52. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.03.036.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Liu ZY, Zhao K, Xiao BL, Wang WG, Ma ZY. Fabrication of CNT/Al composites with low damage to CNTs by a novel solution-assisted wet mixing combined with powder metallurgy processing. Mater Des. 2016;97:424–30. 10.1016/j.matdes.2016.02.121.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Kurita H, Estili M, Kwon H, Miyazaki T, Zhou W, Silvain JF, et al. Load-bearing contribution of multiwalled carbon nanotubes on tensile response of aluminum. Composites Part A. 2015;68:133–9. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2014.09.014.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Basariya MR, Srivastava VC, Mukhopadhyay NK. Microstructural characteristics and mechanical properties of carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum alloy composites produced by ball milling. Mater Des. 2014;64:542–9. 10.1016/j.matdes.2014.08.019.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Wu J, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Wang X. Mechanical and thermal properties of carbon nanotube/aluminum composites consolidated by spark plasma sintering. Mater Des. 2012;41:344–8. 10.1016/j.matdes.2012.05.014.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Huang M, Liu L, Liu X, Qiu J, Wang SA. Modified carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum matrix composite and its preparation method. CN107267811A; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Ranjan R, Bajpai V. Graphene-based metal matrix nanocomposites: recent development and challenges. J Compos Mater. 2021;55(17):2369–413.10.1177/0021998320988566Search in Google Scholar

[19] Cao D. Investigation into surface-coated continuous flax fiber-reinforced natural sandwich composites via vacuum-assisted material extrusion. Prog Addit Manuf. 2000;2023. 10.1007/s40964-023-00508-6.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Cao D, Bouzolin D, Lu H, Todd Griffith D. Bending and shear improvements in 3D-printed core sandwich composites through modification of resin uptake in the skin/core interphase region. Composites Part B. 2023;264:110912. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110912.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Cao D. Increasing strength and ductility of extruded polylactic acid matrix composites using short polyester and continuous carbon fibers. Int J Adv Des Manuf Technol. 2024;130:3631–47. 10.1007/s00170-023-12887-9.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Hiromi N, Ji Y, Li X, Liu J, Zhang W. Preparation device for carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum matrix composite and continuous preparation method of preparation device. CN105238946A, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Nie X, Xiong J. Electrochemical properties of Mn doped nanosphere LiFePO4. Jom. 2021;73:2525–30. 10.1007/s11837-021-04753-4.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Laha T, Chen Y, Lahiri D, Agarwal A. Tensile properties of carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum nanocomposite fabricated by plasma spray forming. Composites Part A. 2009;40:589–94. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2009.02.007.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Ma L, Qiao S, Qiu X, Sun X, Zhang K, Zhu T. Method for preparing carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum matrix composite by utilizing double-shaft shoulder friction stir process. CN111618534A; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Samal P, Vundavilli PR, MeherManas A, Mahapatra M. Reinforcing effect of multiwalled carbon nanotubes on microstructure and mechanical behavior of AA5052 composites assisted by in-situ TiC particles. Ceram Int. 2022;48:8245–57. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.12.029.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Chen L, Li Z, Tang J, Zhang C, Zhao G. Carbon nanotube reinforced multilayer aluminum-based composite material as well as preparation method and application. CN110322987A; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Nie X, Sheng M, Mabi A. Effect of SPS sintering process on compressive strength and magnetic properties of CoCuFeMnNi bulk alloy. Jom. 2022;74:2665–75. 10.1007/s11837-022-05277-1.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Nie XW, Lu Q. Fracture toughness of ZrO2-SiC/MoSi2composite ceramics prepared by powder metallurgy. Ceram Int. 2021;47:19700–8. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.03.309.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Nie XW, Cai MD, Cai S. Microstructure and mechanical properties of a novel refractory high entropy alloy TaZrHfMoSc. Int J Refract Hard Met. 2021;98:105568. 10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2021.105568.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Li Q, Rottmair CA, Singer RF. CNT reinforced light metal composites produced by melt stirring and by high pressure die casting. Compos Sci Technol. 2010;70:2242–7. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2010.05.024.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Liu Z, Xiao B, Wang W, Ma Z. Analysis of carbon nanotube shortening and composite strengthening in carbon nanotube/aluminum composites fabricated by multi-pass friction stir processing. Carbon. 2014;69:264–74. 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.12.025.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Liu ZY, Xiao BL, Wang WG, Ma ZY. Developing high-performance aluminum matrix composites with directionally aligned carbon nanotubes by combining friction stir processing and subsequent rolling. Carbon. 2013;62:35–42. 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.05.049.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Yoo SJ, Han SH, Kim WJ. Strength and strain hardening of aluminum matrix composites with randomly dispersed nanometer-length fragmented carbon nanotubes. Scr Mater. 2013;68:711–4. 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2013.01.013.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Choi H, Wang L, Cheon D, Lee W. Preparation by mechanical alloying of Al powders with single-, double-, and multiwalled carbon nanotubes for carbon/metal nanocomposites. Compos Sci Technol. 2013;74:91–8. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2012.10.011.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Yang X, Zou T, Shi C, Liu E, He C, Zhao N. Effect of carbon nanotube (CNT) content on the properties of in-situ synthesis CNT reinforced Al composites. Mater Sci Eng A. 2016;660:11–8. 10.1016/j.msea.2016.02.062.Search in Google Scholar

[37] Esawi A, Morsi K, Sayed A, Taher M, Lanka S. The influence of carbon nanotube (CNT) morphology and diameter on the processing and properties of CNT-reinforced aluminium composites. Composites Part A. 2011;42:234–43. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2010.11.008.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Esawi A, Morsi K, Sayed A, Taher M, Lanka S. Effect of carbon nanotube (CNT) content on the mechanical properties of CNT-reinforced aluminium composites. Compos Sci Technol. 2010;70:2237–41. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2010.05.004.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Bethune DS, Klang CH, De Vries MS, Gorman G, Savoy R, Vazquez J, et al. Cobalt-catalysed growth of carbon nanotubes with single-atomic-layer walls. Nature. 1993;363:605–7. 10.1038/363605a0.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Prasek J, Drbohlavova J, Chomoucka J, Hubalek J, Jasek O, Adam V, et al. Methods for carbon nanotubes synthesis—Review. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:15872–84. 10.1039/C1JM12254A.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Sanginario A, Miccoli B, Demarchi D. Carbon nanotubes as an effective opportunity for cancer diagnosis and treatment. Biosensors. 2017;7:9–12. 10.3390/bios7010009.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Stein J, Lenczowski B, Anglaret E, Fréty N. Influence of the concentration and nature of carbon nanotubes on the mechanical properties of AA5083 aluminium alloy matrix composites. Carbon. 2014;77:44–52. 10.1016/j.carbon.2014.05.001.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Radhamani AV, Chung Lau H, Ramakrishna S. CNT-reinforced metal and steel nanocomposites: a comprehensive assessment of progress and future directions. Composites Part A. 2018;114:170–87. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2018.08.010.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Yu MF, Files BS, Arepalli S, Ruoff RS. Tensile loading of ropes of single wall carbon nanotubes and their mechanical properties. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;84:5552–5. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.5552.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Troiani HE, Miki-Yoshida M, Camacho-Bragado GA, Marques MAL, Rubio A, Ascencio JA, et al. Direct observation of the mechanical properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes and their junctions at the atomic level. Nano Lett. 2003;3:751–5. 10.1021/nl0341640.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Fahrner WR. Handbook of diamond technology. Uetikon-Zuerich, Switzerland: Trans Tech Publications; 2000.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Sun K, Stroscio MA, Dutta M. Graphite C-axis thermal conductivity. Superlattices Microstruct. 2009;45:60–4. 10.1016/j.spmi.2008.11.018.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Balandin AA. Thermal properties of graphene and nanostructured carbon materials. Nat Mater. 2011;10:569–81. 10.1038/nmat3064.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Carvalho O, Miranda G, Soares D, Silva FS. CNT-reinforced aluminum composites: processing and mechanical properties. Cienc Tecnol Mater. 2013;25:75–8. 10.1016/j.ctmat.2014.03.002.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Ma K, Liu ZY, Zhang XX, Xiao BL, Ma ZY. Hot deformation behavior and microstructure evolution of carbon nanotube/7055Al composite. J Alloy Compd. 2021;854:157275. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.157275.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Pérez-Bustamante R, Estrada-Guel I, Antúnez-Flores W, Miki-Yoshida M, Ferreira PJ, Martínez-Sánchez R. Novel Al-matrix nanocomposites reinforced with multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J Alloy Compd. 2008;450:323–6. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2006.10.146.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Deng CF, Wang DZ, Zhang XX, Li AB. Processing and properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced aluminum composites. Mater Sci Eng, A. 2007;444:138–45. 10.1016/j.msea.2006.08.057.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Bakshi SR, Singh V, Seal S, Agarwal A. Aluminum composite reinforced with multiwalled carbon nanotubes from plasma spraying of spray dried powders. Surf Coat Technol. 2009;203:1544–54. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2008.12.004.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Zhan G, Joshua DK, Wan J, Mukherjee AK. Single-wall carbon nanotubes as attractive toughening agents in alumina-based nanocomposites. Nat Mater. 2003;2:38–42. 10.1038/nmat793.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Guo B, Chen Y, Wang Z, Yi J, Ni S, Du Y, et al. Enhancement of strength and ductility by interfacial nano-decoration in carbon nanotube/aluminum matrix composites. Carbon. 2020;159:201–12. 10.1016/j.carbon.2019.12.038.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Zhang X, Li S, Pan B, Pan D, Liu L, Hou X, et al. Regulation of interface between carbon nanotubes-aluminum and its strengthening effect in CNTs reinforced aluminum matrix nanocomposites. Carbon. 2019;155:686–96. 10.1016/j.carbon.2019.09.016.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Zhou W, Yamaguchi T, Kikuchi K, Nomura N, Kawasaki A. Effectively enhanced load transfer by interfacial reactions in multiwalled carbon nanotube reinforced Al matrix composites. Acta Mater. 2017;125:369–76. 10.1016/j.actamat.2016.12.022.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Guo B, Song M, Zhang X, Liu Y, Cen X, Chen B, et al. Exploiting the synergic strengthening effects of stacking faults in carbon nanotubes reinforced aluminum matrix composites for enhanced mechanical properties. Compos Part B-Eng. 2021;211:108646. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.108646.Search in Google Scholar

[59] Cao L, Chen B, Wan J, Kondoh K, Guo B, Shen J, et al. Superior high-temperature tensile properties of aluminum matrix composites reinforced with carbon nanotubes. Carbon. 2022;191:403–14. 10.1016/j.carbon.2022.02.009.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Choi HJ, Bae DH. Strengthening and toughening of aluminum by single-walled carbon nanotubes. Mater Sci Eng A. 2011;528:2412–7. 10.1016/j.msea.2010.11.090.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Xie K, Zhang G, Huang H, Zhang J, Liu Z, Cai B. Investigation of the main strengthening mechanism of carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum composites. Mater Sci Eng A. 2021;804:140780. 10.1016/j.msea.2021.140780.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Xu ZY, Li CJ, Gao P, You X, Bao R, Fang D, et al. Improving the mechanical properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced aluminum matrix composites by heterogeneous structural design. Compos Commun. 2022;29:101050. 10.1016/j.coco.2021.101050.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Shi Y, Zhao L, Li Z, Li Z, Xiong D, Su Y, et al. Strengthening and deformation mechanisms in nanolaminated single-walled carbon nanotube-aluminum composites. Mater Sci Eng A. 2019;764(138273):1–10. 10.1016/j.msea.2019.138273.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Carvalho O, Buciumeanu M, Mirandaa G, Costac N, Soares D, Silva FS. Mechanisms governing the tensile, fatigue and wear behavior of carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum alloy. Mech Adv Mater Struct. 2015;24:917–25. 10.1080/15376494.2015.1063176.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Noguchi T, Magario A, Fukazawa S, Shimizu S, Beppu J, Seki M. Carbon nanotube/aluminium composites with uniform dispersion. Mater Trans. 2004;45:602–4. 10.2320/matertrans.45.602.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Wu S. Preparation method of carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum-based composite material with surface coated with aluminum oxide. CN110669956A; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Wang M, Shen JA, Chen B, Wang Y, Umeda J, Kondoh K, et al. Compressive behavior of CNT-reinforced aluminum matrix composites under various strain rates and temperatures. Ceram Int. 2022;48:10299–310. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.12.248.Search in Google Scholar

[68] Sadeghi B, Qi J, Min X, Cavaliere P. Modelling of strain rate dependent dislocation behavior of CNT/Al composites based on grain interior/grain boundary affected zone (GI/GBAZ). Mater Sci Eng A. 2021;820:141547. 10.1016/j.msea.2021.141547.Search in Google Scholar

[69] Pérez-Bustamante R, Gómez-Esparza CD, Estrada-Guel I, Miki-Yoshida M, Licea-Jiménez L, Pérez-García SA, et al. Microstructural and mechanical characterization of Al-MWCNT composites produced by mechanical milling. Mater Sci Eng A. 2009;502:159–63. 10.1016/j.msea.2008.10.047.Search in Google Scholar

[70] Kwon, H, , Estili M, Takagi K, Miyazaki T, Kawasaki. A. Combination of hot extrusion and spark plasma sintering for producing carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum matrix composites. Carbon. 2009;47:570–7.10.1016/j.carbon.2008.10.041Search in Google Scholar

[71] He CN, Zhao NQ, Shi CS, Song SZ. Mechanical properties and microstructures of carbon nanotube-reinforced Al matrix composite fabricated by in situ chemical vapor deposition. J Alloy Compod. 2009;487:258–62.10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.07.099Search in Google Scholar

[72] Ma K, Liu ZY, Bi S, Zhang XX, Xiao BL, Ma ZY. Microstructure evolution and hot deformation behavior of carbon nanotube reinforced 2009Al composite with bimodal grain structure. J Mater Sci Technol. 2021;70:73–82. 10.1016/j.jmst.2020.09.003.Search in Google Scholar

[73] Mohammed S, Chen DL, Liu ZY, Ni DR, Wang QZ, Xiao BL, et al. Deformation behavior and strengthening mechanisms in a CNT-reinforced bimodal-grained aluminum matrix nanocomposite. Mater Sci Eng A. 2021;817:141370. 10.1016/j.msea.2021.141370.Search in Google Scholar

[74] Jen YM, Wang YC. Stress concentration effect on the fatigue properties of carbon nanotube/epoxy, composites. Composites Part B. 2012;43:1687–94. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.01.036.Search in Google Scholar

[75] Xi L, Ding K, Zhang H, Gu D. In-situ synthesis of aluminum matrix nanocomposites by selective laser melting of carbon nanotubes modified Al-Mg-Sc-Zr alloys. J Alloy Compd. 2022;891:162047. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.162047.Search in Google Scholar

[76] Fan G, Guo J, Li B, Li Z, Sun Z, Tan Z, et al. Carbon nano-tube reinforced aluminum alloy composite material and powder metallurgic preparation method. CN104532085A; 2015.Search in Google Scholar

[77] Li Z, Liu Q, Meng Q. Carbon nano tube reinforced aluminum silicon carbide composite material and preparation method. CN106555093A; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Srivastava AK, Xu CL, Wei BQ, Kishore R, Sood KN. Microstructural features and mechanical properties of carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum-based metal matrix composites. Sciences. 2008;15:247–55. 10.1109/TPC.2008.2000350.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Kwon H, Leparoux M. Hot extruded carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum matrix composite materials. Nanotechnology. 2012;23:415701. 10.1088/0957-4484/23/41/415701.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[80] Mahendra Kumar C, Raghavendra BV. Effect of carbon nanotube in aluminium metal matrix composites on mechanical properties. J Eng Sci Technol. 2020;15:919–30. 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.05.440.Search in Google Scholar

[81] Manikandan P, Sieh R, Elayaperumal A, Le HR, Basu S. Micro/nanostructure and tribological characteristics of pressureless sintered carbon nanotubes reinforced aluminium matrix composites. J Nanomater. 2000;11:1–10. 10.1155/2016/9843019.Search in Google Scholar

[82] Christopher RB, Gomon JK, Kollo L, Kwon L, Leparoux M. Hardness of multi wall Carbon nanotubes reinforced aluminium matrix composites. J Alloy Compd. 2014;585:362–7. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.09.142.Search in Google Scholar

[83] Zhou S, Zhang X, Ding Z, Min C, Xu G, Zhu W. Fabrication and tribological properties of carbon nanotubes reinforced Al composites prepared by pressureless infiltration technique. Composites Part A. 2007;38:301–6. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2006.04.004.Search in Google Scholar

[84] Preethi K, Raju TN, Shivappa HA, Shashidhar S, Nagral M. Processing, microstructure, hardness and wear behavior of carbon nanotube particulates reinforced Al6061 alloy composites. Mater Today: Proc. 2023;81:449–53. 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.03.608.Search in Google Scholar

[85] Kumar L, Alam SN, Sahoo SK. Influence of nanostructured Al on the mechanical properties and sliding wear behavior of Al-MWCNT composites. Mater Sci Eng, B. 2021;269:115162. 10.1016/j.mseb.2021.115162.Search in Google Scholar

[86] Choi HJ, Bae DH. Creep properties of aluminum-based composite containing multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Scr Mater. 2011;65:194–7. 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2011.03.038.Search in Google Scholar

[87] Kim WJ, Lee SH. High-temperature deformation behavior of carbon nanotube (CNT)-reinforced aluminum composites and prediction of their high-temperature strength. Composites Part A. 2014;67:308–15. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2014.09.008.Search in Google Scholar

[88] Coble RL. A model for boundary diffusion controlled creep in polycrystalline materials. J Appl Phys. 1963;34:1679–82. 10.1063/1.1702656.Search in Google Scholar

[89] Carvalho O, Buciumeanu M, Miranda G, Costa N, Soares D, Silva FS. Mechanisms governing the tensile, fatigue, and wear behavior of carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum alloy. Mech Adv Mater Struct. 2016;23:917–25. 10.1080/15376494.2015.1063176.Search in Google Scholar

[90] Liao JZ, Tan MJ, Bayraktar E. Tension-tension fatigue behaviour of carbon nanotube reinforced aluminium composites. Mater Sci Forum. 2013;765:563–7. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.765.563.Search in Google Scholar

[91] Merati A. A study of nucleation and fatigue behavior of an aerospace aluminum alloy 2024–T3. Int J Fatigue. 2005;27:33–44. 10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2004.06.010.Search in Google Scholar

[92] Walker K. The effect of stress ratio during crack propagation and fatigue for 2024-T3 and 7075-T6 aluminum. Vol. 1; ASTM International; 2009. p. 1–14.10.1520/STP32032SSearch in Google Scholar

[93] Wang Q, Apelian D, Lados D. Fatigue behavior of A356-T6 aluminum cast alloys. Part I. effect of casting defects. J Light Met. 2001;1:73–84. 10.1016/S1471-5317(00)00008-0.Search in Google Scholar

[94] Ding HZ, Biermann H, Hartmann O. A low cycle fatigue model of a short-fibre reinforced 6061 aluminium alloy metal matrix composite. Compos Sci Technol. 2002;62:2189–99. 10.1016/S0266-3538(02)00160-4.Search in Google Scholar

[95] Bi S, Liu ZY, Xiao BL, Xue P, Wang D, Wang QZ, et al. Different fatigue behavior between tension-tension and tension-compression of carbon nanotubes reinforced 7055 Al composite with bimodal structure. Carbon. 2021;184:364–74. 10.1016/j.carbon.2021.08.034.Search in Google Scholar

[96] Mohammed S, Chen DL, Liu ZY, Wang QZ, Ni DR, Xiao BL, et al. Cyclic deformation behavior and fatigue life modeling of CNT-reinforced heterogeneous aluminum-based nanocomposite. Mater Sci Eng A. 2022;840:142881. 10.1016/j.msea.2022.142881.Search in Google Scholar

[97] Myriounis D, Matikas T, Hasan S. Fatigue behaviour of SiC particulate-reinforced A359 aluminium matrix composites. Strain. 2012;48:333–41. 10.1111/j.1475-1305.2011.00827.x.Search in Google Scholar

[98] Bakshi SR, Agarwal A. An analysis of the factors affecting strengthening in carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum composites. Carbon. 2000;49:533–44. 10.1016/j.carbon.2010.09.054.Search in Google Scholar

[99] Liao JZ, Tan MJ, Sridhar I. Spark plasma sintered multi-wall carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum matrix composites. Mater Des. 2010;31:S96–100. 10.1016/j.matdes.2009.10.022.Search in Google Scholar

[100] Choi H, Shin J, Min B, Park J, Bae D. Reinforcing effects of carbon nanotubes in structural aluminum matrix nanocomposites. J Mater Res. 2009;24:2610–6. 10.1557/jmr.2009.0318.Search in Google Scholar

[101] Wang J, Li Z, Fan G, Pan H, Chen Z, Zhang D. Reinforcement with graphene nanosheets in aluminum matrix composites. Scr Mater. 2012;66:594–7. 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2012.01.012.Search in Google Scholar

[102] Loos MR, Yang J, Feke DL, Manas-Zloczower I, Unal S, Younes U. Enhancement of fatigue life of polyurethane composites containing carbon nanotubes. Composites Part B. 2013;44:740–4. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.01.038.Search in Google Scholar

[103] Srivastava I, Koratkar N. Fatigue and fracture toughness of epoxy nanocomposites. JOM. 2010;62:50–7. 10.1007/s11837-010-0032-8.Search in Google Scholar

[104] Baur J, Silverman E. Challenges and opportunities in multifunctional nanocomposite structures for aerospace applications. MRS Bull. 2007;32:328–34. 10.1557/mrs2007.231.Search in Google Scholar

[105] Liu Z, Ma Z, Xiao B, Wang Q, Wang D, Ni D, et al. High-toughness carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum-based composite material with non-uniform structure and preparation method thereof. CN110724842 (A); 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[106] Bi S, Liu ZY, Xiao BL, Zan YN, Wang D, Wang QZ, et al. Enhancing strength-ductility synergy of carbon nanotube/7055Al composite via a texture design by hot-rolling. Mater Sci Eng A. 2021;806:140830. 10.1016/j.msea.2021.140830.Search in Google Scholar

[107] Fu X, Yu Z, Tan Z, Fan G, Li P, Wang M, et al. Enhanced strain hardening by bimodal grain structure in carbon nanotube reinforced Al-Mg composites. Mater Sci Eng A. 2021;803:140726. 10.1016/j.msea.2020.140726.Search in Google Scholar

[108] Wang M, Li Y, Chen B, Shi D, Umeda J, Kondoh K, et al. The rate-dependent mechanical behavior of CNT-reinforced aluminum matrix composites under tensile loading. Mater Sci Eng A. 2021;808:140893. 10.1016/j.msea.2021.140893.Search in Google Scholar

[109] Chen J, Yan L, Liang S, Cui X, Liu C, Wang B, et al. Remarkable improvement of mechanical properties of layered CNTs/Al composites with Cu decorated on CNTs. J Alloy Compd. 2022;901:163404. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.163404.Search in Google Scholar

[110] Boesl B, Lahiri D, Behdad S, Agarwal A. Direct observation of carbon nanotube induced strengthening in aluminum composite via in situ tensile tests. Carbon. 2014;69:79–85. 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.11.061.Search in Google Scholar

[111] Chen B, Li B, Imai H, Jia L, Umeda J, Takahashi M. Load transfer strengthening in carbon nanotubes reinforced metal matrix composites via in-situ tensile tests. Compos Sci Technol. 2015;113:1–8. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2015.03.009.Search in Google Scholar

[112] Chen B, Kondoh K, Umeda J, Li S, Jia L, Li J. Interfacial in-situ Al2O3 nanoparticles enhance load transfer in carbon nanotube (CNT)-reinforced aluminum matrix composites. J Alloy Compd. 2019;789:25–9. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.03.063.Search in Google Scholar

[113] Chen B, Shen J, Ye X, Imai H, Umeda J, Takahashi M, et al. Solid-state interfacial reaction and load transfer efficiency in carbon nanotubes (CNTs)-reinforced aluminum matrix composites. Carbon. 2017;114:198–208. 10.1016/j.carbon.2016.12.013.Search in Google Scholar

[114] Zhou W, Yamamoto G, Fan Y, Kwon H, Hashida T, Kawasaki A. In-situ characterization of interfacial shear strength in multiwalled carbon nanotube reinforced aluminum matrix composites. Carbon. 2016;106:37–47. 10.1016/j.carbon.2016.05.015.Search in Google Scholar

[115] Bakshi SR, Lahiri D, Agarwal A. Carbon nanotube reinforced metal matrix composites – a review. Int Mater Rev. 2010;55:41–64. 10.1179/095066009X12572530170543.Search in Google Scholar

[116] Nie XW, Lv YB. Effect of heat treatment on microstructure of Al0.78CoCrFeNi alloy fabricated by laser additive manufacturing. Jom. 2024;76(2):43–852. 10.1007/s11837-023-06243-1.Search in Google Scholar

[117] Li XY, Lu K. Playing with defects in metals. Nat Mater. 2017;16:700–1. 10.1038/nmat4929.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.