Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

-

Charles Sarala Rubi

, Sharad Ramdas Gawade

Abstract

With the enhancement in science and technology, necessity of complex shapes in manufacturing industries have become essential for more versatile applications. This leads to the demand for lightweight and durable materials for applications in aerospace, defense, automotive, as well as sports and thermal management. Wire electric discharge machining (WEDM) is an extensively utilized process that is used for the exact and indented shaped components of all materials that are electrically conductive. This technique is suitable in practically all industrial sectors owing to its widespread application. The present investigation explores WEDM for LM6/fly ash composites to optimize different process variables for attaining performance measures in terms of maximum material removal rate (MRR) and minimum surface roughness (SR). Taguchi’s L27 OA design of experiments, grey relational analysis, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were employed to optimize SR and MRR. It has been noted from ANOVA that reinforcement (R) percentage and pulse on time are the most influential aspects for Grey Relational Grade (GRG) with their contributions of 28.22 and 18.18%, respectively. It is found that the best process variables for achieving the highest MRR and lowest SR simultaneously during the machining of the composite are gap voltage of 30 V, pulse on time of 10 µs, pulse off time of 2 µs, wire feed of 8 m/min, and R of 9%. The predicted GRG is 0.84, and the experimental GRG value is 0.86. The validation experiments at the optimized setting show close agreement between predicted and experimental values. The morphological study by optical microscopy revealed a homogenous distribution of reinforcement in the matrix which enhances the composite’s hardness and decreases the density.

1 Introduction

Although composites have been available since the earliest days, it was only in World War II that they were commercially viable. In order to create new materials and improve the properties of the base materials, a composite material combines multiple physical elements [1]. Aluminum matrix composites (AMCs) are growing in demand for use in automobiles, airplanes, and other applications in engineering. AMCs consistently meet the demand for robust, lightweight, and outstanding performance components. Exceptional durability, resistance to wear, and low thermal expansion and conductivity in electricity are all the characteristics of AMCs. It facilitates replacing traditional Al alloys [2].

Al alloy is a viable substitute for brake rotors due to the cast iron recyclable qualities issue and improved efficiency, and it has a wide variety of automotive uses. To improve the structural durability and maintain proper coefficient of friction regardless of repeated braking, abrasive particles, like silicon carbide and alumina, are utilized [3,4,5]. Over 80% of metal matrix composites (MMCs), according to the investigation, are utilized for ground-based transportation. For certain applications, appropriate inclusion of the matrix, reinforcement (R), and manufacturing techniques results in better physical and corrosive characteristics [6]. The size of a reinforcement particle used in a typical MMC ranges from 2 to 200 µm and the volume fraction varies between 5 and 40%. Also, matrices are generally based on light metal alloys like aluminum, copper, zinc, steel, and magnesium. Reinforcements used are generally of abrasive nature with high hardness [7]. The goal of the sector is to make things that are both affordable and high-quality in a short amount of time. To achieve effective cutting efficiency, the industry must operate near the optimum cutting factors [8]. Because of this, it is important to choose machining variables like gap voltage (GV), pulse on time (T on), pulse off time (T off), wire feed (WF), and R carefully. Digitally controlled cutting machines must run effectively in order to produce the required product since they are more expensive than their conventional counterparts [9].

The fabrication of hybrid MMC materials, which have recently proven to have more desirable properties, involves embedding the matrix phase with two or more second-phase materials [10]. Hybrid AMCs are designed for various uses, including drive shafts, brake rotors, airframe structures, vehicle parts, aviation, and airplane components. These materials can be manufactured by a variety of techniques [11].

The manufacturing sector first encountered wire electric discharge machining (WEDM) in the latter half of the 1960s. The unconventional material removal technique WEDM is commonly utilized to create parts with complex forms and shapes. The WEDM technology minimizes stresses that happen while machining. It additionally reduces the changes in geometry that take place during the machining of heat-treated steel and can work with exotic materials [12].

Nonconventional machining techniques, including electrical discharge machining (EDM), electro chemical machining, abrasive water jet machining, and laser beam machining, are alternatives that get beyond the restrictions of conventional machining methods, like machining a complicated shape, low precision, energy consumption, recycling, etc. [13,14]. Complex dimensions, such as hydraulic and injection mold parts, can be machined using WEDM. In WEDM, the component being machined and the wire material interact thermoelectrically to carry out the machining so that the hardest materials can be easily machined [15]. The parameters such as GV, T on, T off, WF, and R all influence how well the WEDM performs.

EDM and WEDM have similar material removal methods; however, they have different functional properties. WEDM uses an extremely fine wire continually fed through the work piece by a microprocessor controller, allowing for the incredibly high accuracy needed to make components with intricate shapes [16]. For the roughing and finishing processes in EDM, WEDM does not require the complex pre-shaped electrodes that are frequently needed.

Materials are removed by repeated electrical pulses with duration of 10−4 to 10−6 s across the specimen and the tool electrode [17]. The machine generator produces these electrical impulses and removes material through evaporation in addition to electrical discharge. A stream of dielectric liquid that has elevated resistance to electricity always washes the eroded material away from the cutting point [18,19]. The component being machined does not get stressed by traditional forces, as is typical when using traditional machining techniques because there is always a gap between the wire electrode and the specimen. Because of this, even very fragile materials can be machined, and thin-walled profiles can be made [20]. Another benefit is that irrespective of their toughness or hardness, all materials that are preferably somewhat conductive to electricity can be machined, which can also hinder the conventional machining of certain materials. The procedure’s increased energy usage and comparatively slow material removal are drawbacks [21,22].

Ti-6Al-4V was employed as the work material by Basak et al. [23], and a brass wire with 0.25 mm diameter served as the electrode. The surface roughness (SR) was predicted and modeled using a two-level factorial approach. The machining variables were input voltage, T on, dielectric fluid pressure, and T off. The findings demonstrated that with shorter pulse-on and at a lower dielectric fluid pressure, a superior surface quality could be achieved. Ti-6Al-4V has been investigated as a potential work material by Alis et al. [24]. A titanium alloy was machined using brass wire and a steady 4 A current. The wire tension, wire speed, and discharge current were chosen as the machining variables. Based on their research, they concluded that increasing the current produced a higher rate of material removal and that increasing the wire tension produced a smooth surface.

Furthermore, it was seen that as wire tension increased, the vibrations of the wire decreased. A Ti-6Al-4V alloy was machined using the WEDM technique by Gupta et al. [25] using a steady 6 A current and variable machining speeds between 2 and 6 mm/min. The machining variables included the pulse duration, wire speed, servo voltage, feed rate, and wire tension. The responses were the material removal rate (MRR) and SR. At a reduced machining feed rate and a greater wire tension, the surface circumstances were satisfactory. Some process variables, such as wire speed and pulse length, were found to be less beneficial for MRR.

Ni55.8Ti shape memory alloy has been machined by WEDM process. The effects of input parameters such as spark GV, pulse on-time, pulse off-time, and WF on metal removal rate (MRR) and surface quality have been investigated. Empirical modeling and analysis of variance (ANOVA) study have been done after conducting 16 experiments based on Taguchi’s L16 design of experiments (DoE) technique. Ranking and crowding distance-based non-dominated sorting algorithm-II (NSGA-II) is used for process optimization. The error percentage varies within ± 6% between experimental results and the predicted results developed by NSGA-II [26].

Several researchers attempted to improve the performance characteristics such as MRR, SR, surface and subsurface properties in WEDM. But full potential utilization of this process is still not completely solved due to its complexity, stochastic nature, and in addition, involvement of more number of process variables in this process [27].

The prior works on WEDM indicate that most of the studies concentrated on the influence of process parameters on SR and MRR during machining of different composites. Hence, the aim of the present study is to develop the mathematical models using Minitab software for the WEDM characteristics and then to simultaneously optimize the proposed WEDM characteristics of LM6/fly ash composites. Al-Matrix composites are considered as one of those classes of advanced engineering materials. Hence, it is obligatory to investigate the impact of different machining conditions for the selection of optimum parameter settings for aluminum-based hybrid MMC material.

The present investigation demonstrates the significance of cutting variables on Grey Relational Grade (GRG) of LM6/fly-ash composites. ANOVA is used to confirm the model’s validity. The findings demonstrate that the given model can precisely predict the MRR and SR in WEDM LM6/fly-ash composite material within the reported parameters. The present work provides optimum process variables for the researchers engaged in the WEDM of different kinds of MMCs. The trend is the same even when the material is different. This investigation reveals how process variables affect various responses. This article will be useful to the budding researchers to know about the WEDM process parameters, and their effect on MRR, SR, and GRG.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Al alloy LM6

Due to its tendency to drag and fast tool wear, Al alloy (LM6) is hard to machine. It exhibits good corrosion resistance in both ambient and marine environments. Unlike any other casting alloy, it is capable of being cast into thin, complex components. It provides outstanding pressure tightness, hence is a good choice for hydraulic systems and pressure vessels. The casting properties make it very efficient for complex parts. Optical emission spectrometry (ASTM E 1251-07) was used to determine the elemental Composition of the LM6 alloy, which is displayed in Table 1.

Elemental composition of the LM6 alloy

| Constituent | Si | Cu | Fe | Mg | Mn | Ti | Ni | Zn | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (%) | 11.48 | 0.013 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | Remainder |

2.2 Fly ash

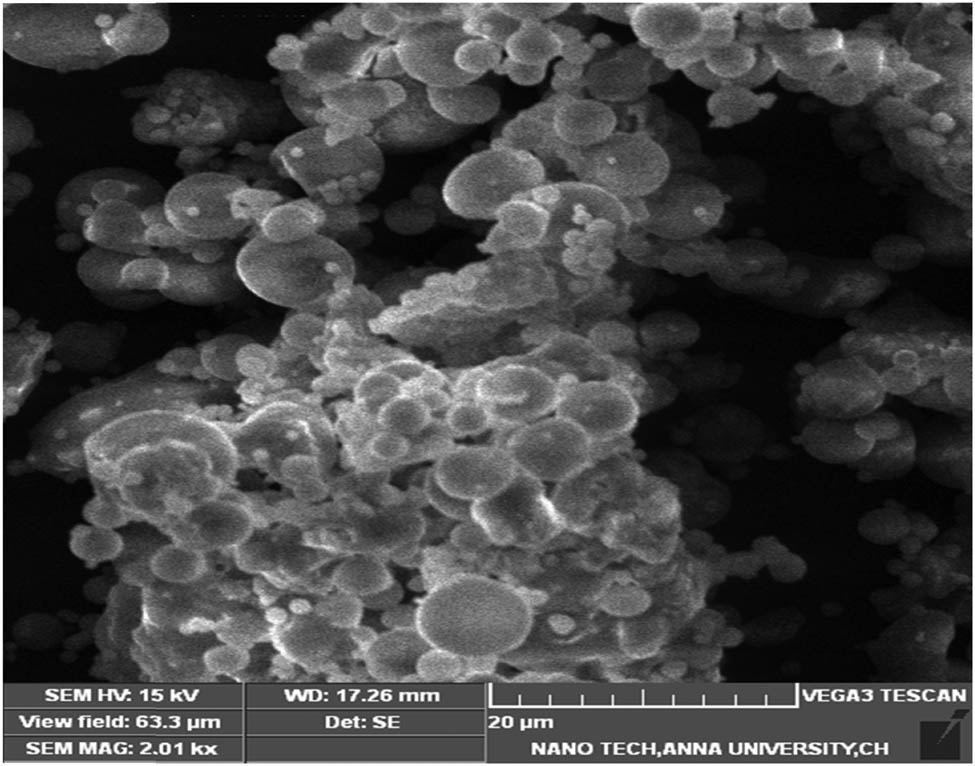

Fly ash particulates with a particle size of 12 μm have been used in this study as reinforcement. The presence of reinforcement in the LM6 alloy enhances their resistance to wear, damping abilities, hardness, and stiffness and decreases the weight. Fly ash particulates are thermal power plant wastes that are present in high amounts and are a form of intermittent reinforcement. The unique properties associated with fly ash, such as low electrical and thermal conductivity and lightweight, makes it useful in fabricating composite material that are less in weight and insulating. Al-fly ash composite materials have potential applications in the automobile and electrochemical sectors [28]. Table 2 and Figure 1 show the elemental constitution and surface morphology of fly ash particles, respectively.

Elemental constitution of fly ash

| Constituent | Al | Si | O | Fe | Ti | K | Ca | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (%) | 16.73 | 26.43 | 38.88 | 3.82 | 1.42 | 0.99 | 0.5 | Remainder |

Surface morphology of fly ash particles.

2.3 Fabrication of LM6/fly ash composites

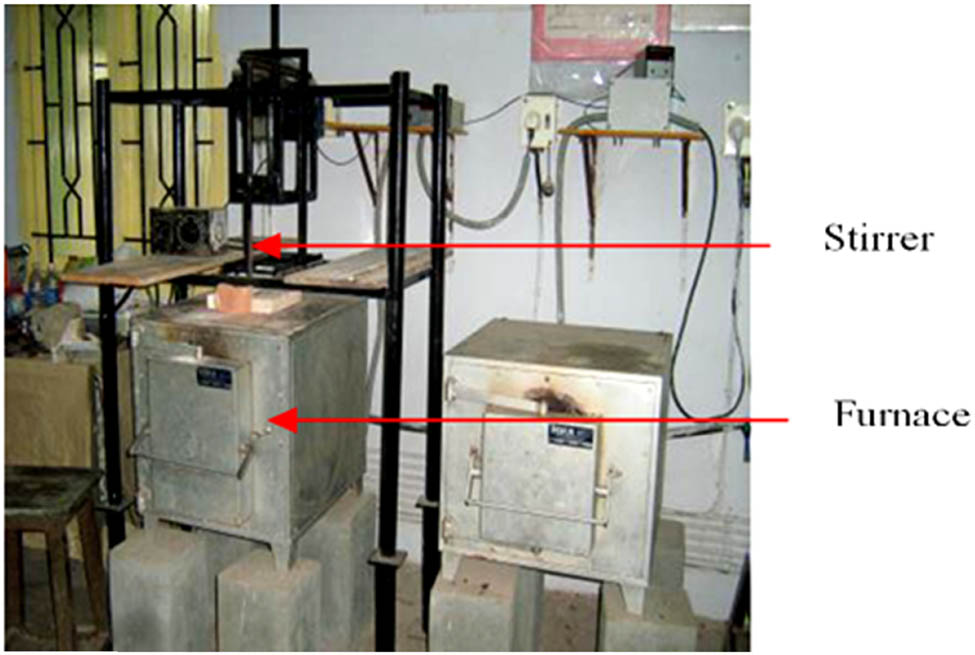

The simple and economical technique for producing the composites is stir casting. In this method, the reinforcement is embedded uniformly in the molten LM6 alloy by mechanical stirring [29,30]. Figure 2 shows the fabrication setup utilized in composite preparation.

Stir casting set up.

Blocks of Al alloy LM6 have been heated in an electric furnace to melt them. Slowly, the furnace’s temperature was increased to 850°C, and the melt was degassed using hexachloroethane in order to get rid of the dissolved gases. The melted metal was then mixed with the fly ash particles that had been heated to 250°C. For 10 min, a mechanical stirrer was used to continually agitate the slurry at 600 rpm in order to create a slurry. A tiny amount of Mg was mixed with the slurry to increase the wettability of the particles as they interacted with the metal. The slurry was then transferred into 650°C preheated molds, where it was allowed to cool to ambient temperature. Fly ash was incorporated into the continuous phase with the concentration of 3, 6, and 9 wt%.

2.4 Selection of parameters and orthogonal array (OA)-DoE

The DoE is a technique used to define what data, and in what quantity and settings must be collected during an experimentation, to satisfy two foremost goals: the statistical accuracy of the response parameters accompanied by lesser cost [31]. In the present investigation, five different process parameters at three levels were selected, viz. GV, pulse on time (T on), pulse off time (T off), WF, and R%. The responses are MRR and SR. Based on the selected parameters, L27 array is selected for the present investigation. L27 array has an exceptional property that the two-way interactions between several factors are partially confounded with various columns and hence their effect on the estimation of the main effects of the various parameters is minimized. The number of parameters is five and their levels are three. Therefore, 35 = 243 experiments using full factorial design should be conducted, but 27 experiments were conducted using DoE. So, 216 experiments were reduced. 1/9 experiments were conducted and saved 88% time and resources. Experiments have been repeated three times at each experimental condition. The machining variables and their levels are depicted in Table 3.

Machining variables and their levels

| Levels | Pulse on time (µs) | Pulse off time (µs) | WF (m/min) | GV (V) | R% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 30 | 3 |

| 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 50 | 6 |

| 3 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 70 | 9 |

2.5 Grey relational analysis (GRA)

While dealing with machining optimization problems, there are usually more than one quality characteristics (and often conflicting), due to high process complexity. The overall goal is to find solutions that are acceptable by the decision maker. Although in single-objective optimization problems, it is straight forward to find an optimal solution, multi-objective ones provide users with sets of solutions, out of which one should be chosen so as to be applied in physical systems [32].

GRA can be used to determine the relation among sequences. For the optimization of machining variables, the below-mentioned steps are followed:

Normalize the MRR and SR for WEDM experimental data;

Identify the sequence of deviation.

Find the grey relational coefficient (GRC).

By averaging the GRC, determine the GRG.

Utilize statistical examination of variance and GRG to analyze the experimental outcomes.

Choose the optimum machining variable.

Conduct confirmation experiments to validate the optimization method.

2.5.1 Data pre-processing

The preparation of data in GRA is the process of first normalizing the results of the experiment of the MRR and SR to be in the range of 0–1. For the GRA, different data preliminary processing approaches are available depending on the features of a data sequence. “Higher-the-better” property is used if the target value is infinite. The normalization of the original sequence is given in Equation (1).

For “lower-the-better” property, the normalization of the sequence is given in Equation (2),

where

2.5.2 GRC

The term “GRC” refers to the measure of significance among two distinct processes or sequences in GRA. The purpose of the GRA is to demonstrate the degree of relationship between the x o (k) and x i (k) sequences. The GRC is given in Equation (3).

where Δ 0i (k) denotes the deviation sequence.

where Δ min and Δ max are the smallest and largest value of ∆ 0i (k), respectively, and

2.5.3 GRG

The GRG is the foundation for the evaluation of the multi-response feature. It is given in Equation (4).

where

2.5.4 Predicting the optimum responses

The optimal condition is chosen based on the experiment’s goal, which is either maximization or reduction of the response. If there are three variables, say A, B, and C and three levels, 1, 2, and 3 and the first levels are the optimum conditions, then the predicted optimum response µpred is given in Equation (5).

where

2.6 ANOVA

ANOVA is used to analyze investigational findings concerning the investigation’s parameters. The % contribution shows how much each interaction contributed to the overall variance. The percentage of error-related responses shows the experiment’s efficiency before pooling. Generally speaking, if the proportion contribution attributable to error is 15% or less, no significant variables have been left out of the experiment. If it is higher (at least 50%), either there was a significant measurement error, or certain factors were not taken into account.

3 Machining and measurement

3.1 WEDM

The WEDM process is chosen for studying the machinability of the composites and the LM6 Al alloys. The image of CNC WEDM is presented in Figure 3.

Photograph of ECOCUT – CNC wire EDM.

3.2 Machining performance variables

MRR and SR were taken as the output responses in this study.

3.2.1 MRR

MRR is obtained by the ratio of the volume of the material removed from the specimen (mm3) to the time taken (min).

3.2.2 SR

Figure 4 shows the SR of the machined component as determined using a Surfcorder SE 3500 surface roughness tester. This measurement plays an important role in several fundamental issues, including friction, surface distortion, heat transmission, electrical current, joint stiffness, and spatial accuracy. The information was collected at three different locations on the machined surface, and the SR was calculated using the mean of the three measurements. An SR calculation’s orientation was perpendicular to the surface that was being machined [33].

Surface roughness tester.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Microstructure

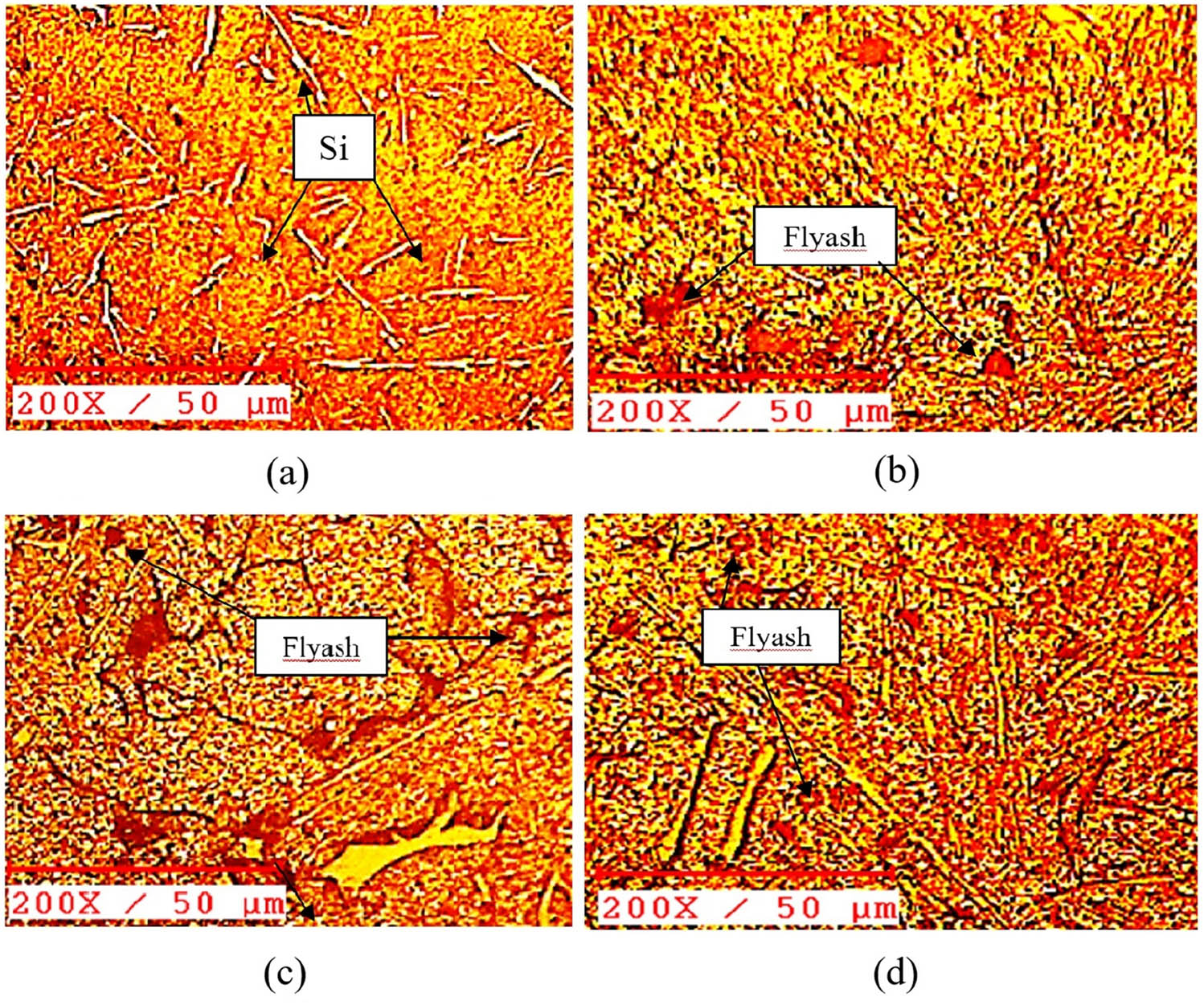

Microstructure is the term used to describe the materials’ appearance from the scale of micrometer to nanometer length. Microstructure helps analyze the presence of various phases in a composition. By modifying the microstructure, the desired properties can be obtained. It also affects the physical properties and mechanical behavior of materials. The ultimate goal of the micrograph is to observe the nature of the dispersion of reinforcement in the continuous phase. An optical microscope was used for this analysis, and the images show the uniform dispersion of the second phase material in the matrix and are depicted in Figure 5.

(a–d) Micrographs of LM6 and LM6/Fly ash composites. (a) Al alloy (LM6). (b) LM6 + 3% fly ash. (c) LM6 + 6% fly ash. (d) LM6 + 9% fly ash.

The physical properties of reinforcement particles and the physical properties of Al alloy decide the outcome of the composites. Figure 5(b) shows the distribution of 3% reinforcement in LM6 alloy matrix composites. The distribution is uniform, and the particles are closer to neighboring particles. This is due to the very low viscosity of LM6 Al alloy. Figure 5(c) and (d) shows the presence of 6 and 9% fly ash in LM6 alloy matrix composites, respectively. The Al-Si eutectic remains unchanged with a script-like shape in the composite materials (Figure 5a).

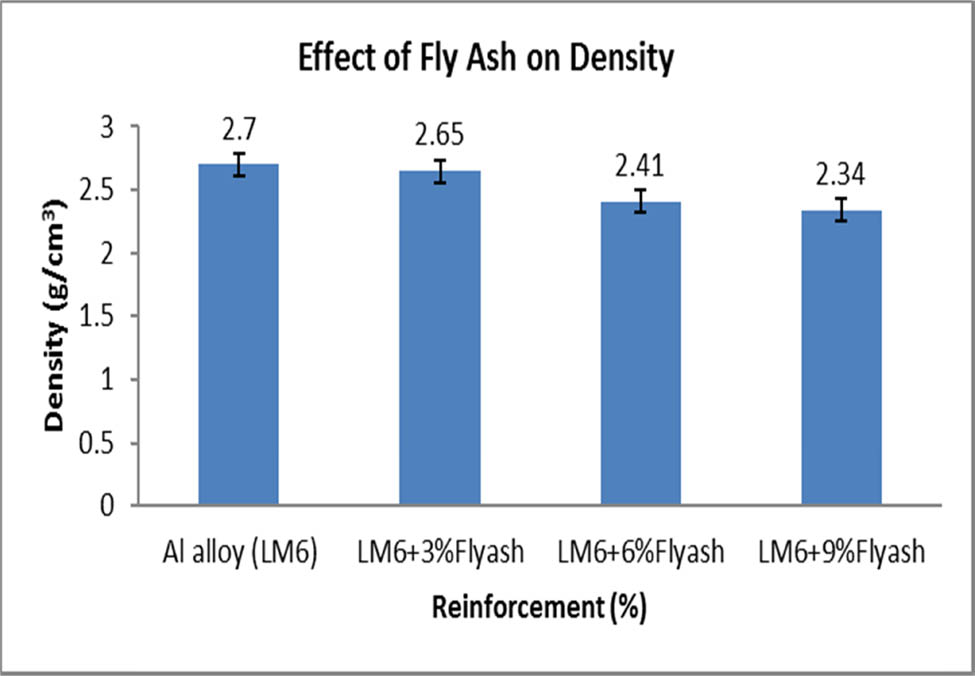

4.2 Density

The density of the composites and Al alloy (LM6) was found using the Archimedes principle and it is given in Equation (6).

Figure 6 displays the impact of fly ash particle weight percentages on the density of composites. The specimen’s density reduces with a rise in the amount of second-phase material. The key reason is that fly ash has a lower density (2.09 g/cm3) than LM6 alloys (2.70 g/cm3). A linear reduction is seen in the composite materials with rising dispersoid content [34,35]. The findings indicate that when the wt% of R increased, the specimen’s density decreased [36].

Effect of fly ash on the density of AMCs.

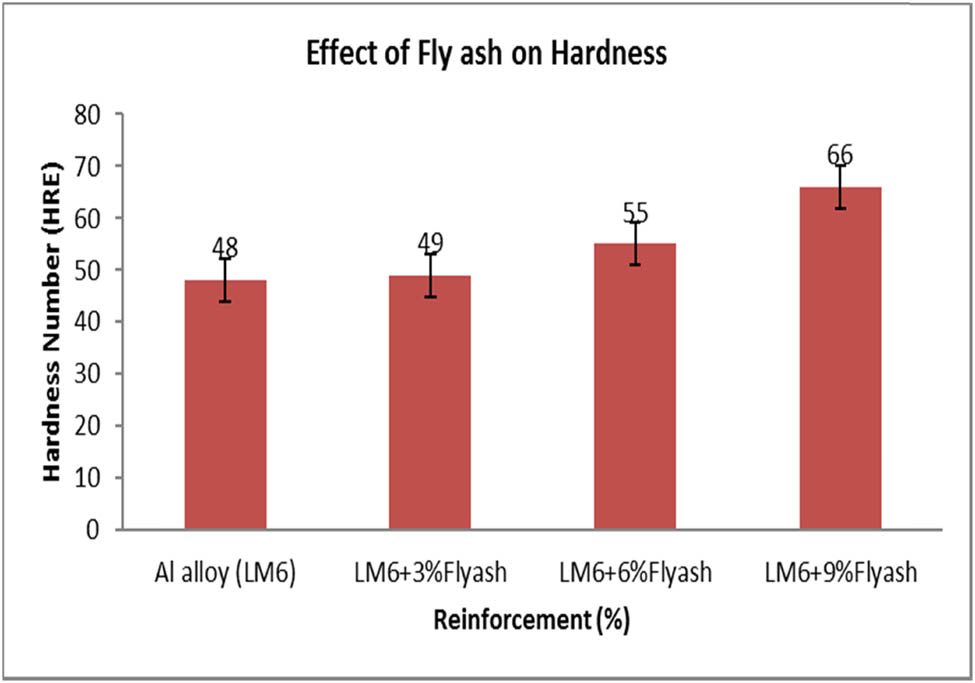

4.3 Hardness

The hardness of the composite materials and LM6 were determined using a Rockwell hardness tester. It is observed from Figure 7 that the hardness of the specimen was larger than that of the LM6 alloy. The composite material LM6/9% fly ash has the highest hardness value among the LM6 matrix composites.

Influence of fly ash on the hardness of AMCs.

The result of high hardness is due to the inclusion of fly ash particles like cenospheres and precipitators [37,38]. By adding the reinforcement particles to the composites, surface area of the reinforcement increases and the grain sizes of the matrix decrease. The presence of such hard reinforcement particles on the surface resists the plastic deformation of the material. The strength of the grain boundaries increases to maximum level and dislocation of atoms are decreased by increasing the wt% of the reinforcement, which gives strength to the matrix and thereby hardness of the composite gets increased [39,40].

4.4 Optimization of WEDM LM6/fly ash AMCs

The experimental findings on WEDM of LM6/fly ash are presented in this section. GRA was used to optimize the responses to obtain the highest MRR and the lowest SR values concurrently. The value of GRG was used to identify the best machining variables.

4.4.1 Experimental results

The goal of the WEDM studies is to investigate how cutting variables influenced the features of the output response. The 27 rows of the L27 OA, which has 13 columns and 3 levels, correspond to the number of experiments. Table 4 displays the experimental outcomes together with associated GRG and Ranks.

Experimental results of MRR and SR

| Ex. no. | GV (V) | T on (µs) | T off (µs) | WF (m/min) | R (wt%) | MRR (mm3/min) | SR (µm) | GRG | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 27.118 | 4.74 | 0.507 | 24 |

| 2 | 30 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 23.874 | 4.07 | 0.542 | 20 |

| 3 | 30 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 21.586 | 3.76 | 0.566 | 17 |

| 4 | 30 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 41.493 | 3.1 | 0.975 | 1 |

| 5 | 30 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 27.609 | 4.74 | 0.511 | 23 |

| 6 | 30 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 28.728 | 3.35 | 0.692 | 6 |

| 7 | 30 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 41.038 | 3.51 | 0.871 | 3 |

| 8 | 30 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 37.248 | 3.02 | 0.891 | 2 |

| 9 | 30 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 27.339 | 5.36 | 0.471 | 25 |

| 10 | 50 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 24.092 | 4.3 | 0.520 | 22 |

| 11 | 50 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 17.96 | 3.5 | 0.587 | 15 |

| 12 | 50 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 17.408 | 3.11 | 0.669 | 8 |

| 13 | 50 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 33.224 | 3.8 | 0.667 | 9 |

| 14 | 50 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 23.82 | 4.03 | 0.546 | 19 |

| 15 | 50 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 21.173 | 3.24 | 0.658 | 11 |

| 16 | 50 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 33.982 | 3.24 | 0.778 | 4 |

| 17 | 50 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 28.083 | 3.31 | 0.694 | 5 |

| 18 | 50 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 25.27 | 6.34 | 0.413 | 27 |

| 19 | 70 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 18.109 | 4.82 | 0.441 | 26 |

| 20 | 70 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 10.688 | 3.54 | 0.549 | 18 |

| 21 | 70 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 10.003 | 3.67 | 0.525 | 21 |

| 22 | 70 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 18.068 | 3.56 | 0.577 | 16 |

| 23 | 70 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 15.014 | 3.01 | 0.687 | 7 |

| 24 | 70 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 13.127 | 3.38 | 0.588 | 14 |

| 25 | 70 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 20.521 | 3.4 | 0.620 | 13 |

| 26 | 70 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 9 | 16.292 | 3.1 | 0.667 | 10 |

| 27 | 70 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 15.481 | 3.15 | 0.650 | 12 |

4.4.2 Analysis and discussion

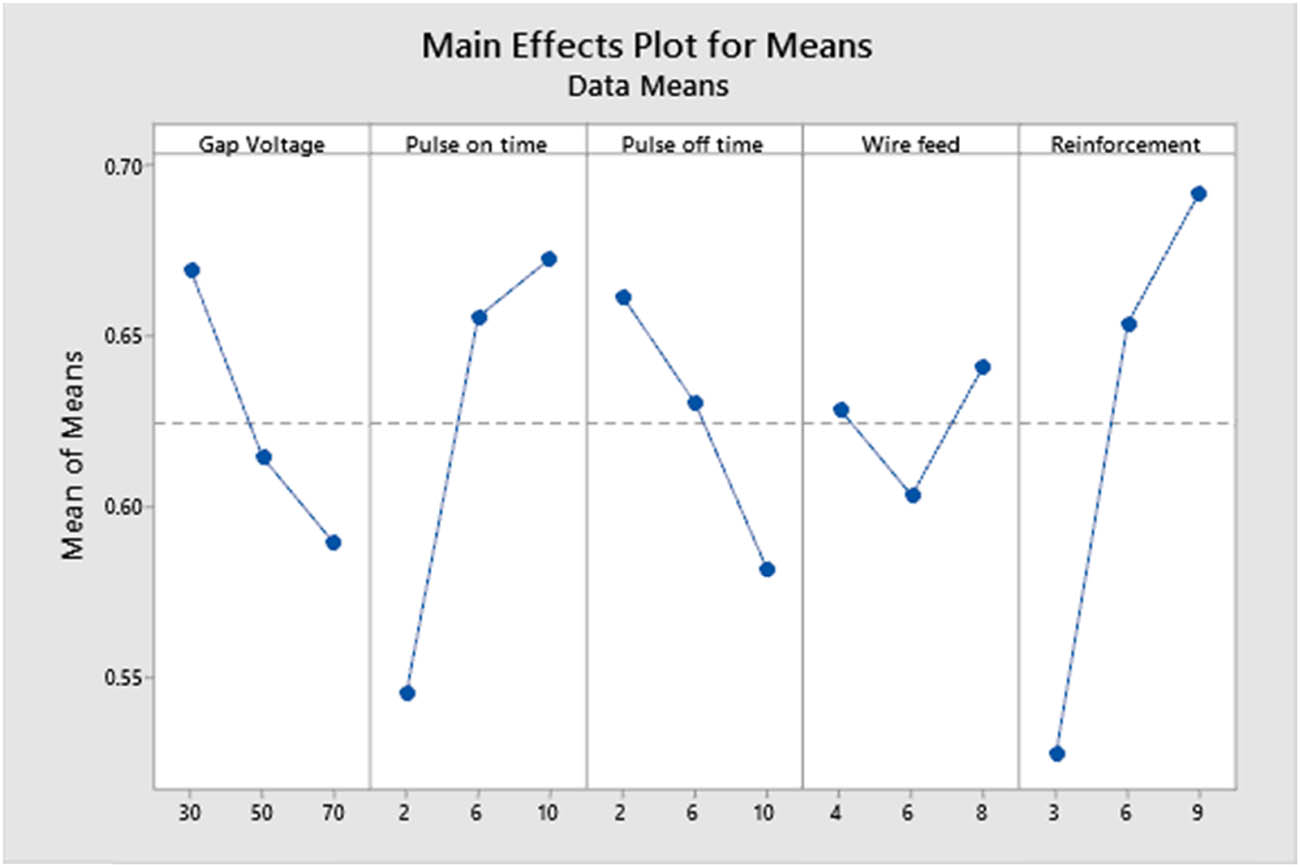

This section discusses the influence of various cutting variables on the MRR and SR quality characteristics that were chosen. Using the findings of the experiment, GRA has been employed to generate a GRG of the output parameters for each factor at multiple levels. Plots illustrating the GRG data’s major effects on process variables were drawn. Examining how parametric variables influence the response features is done using the response graphs. ANOVA is used to determine the important factors and analyze how much of an impact they have on the response features. Figure 8 demonstrates that the GRG rises with the increase in the “WF” and “R” during the pulse on time and diminishes with the increase in the “GV” and “T off.” This is because a higher rate of MRR results from an increase in the discharge energy as “T on” increases. The amount of discharges during a given period decreases as “T off” increases, which provides a good surface finish. The average discharge gap widens with an increase in “GV,” resulting in a minimum SR value. Because greater WF values result in larger MRR, the MRR increases with the “WF”.

Response graphs for GRG.

4.4.3 Selection of optimal levels

The ranks and the delta values reveal that “R,” followed in that order by “T on,” “T off,” “GV,” and “WF,” has the major impact on achieving the larger GRG. It is observed from Figure 8 that the first level of “GV,” third level of “T on,” first level of “T off,” third level of “WF,” and third level of “R” provide optimal values.

ANOVA is utilized in this investigation to optimize the cutting factors by examining the relative importance of each variable in terms of how significantly they contribute to the MRR and SR. The analysis strategy was examined with a 95% confidence level. Table 5 provides the findings of ANOVA for GRG. The value of R 2 for GRG is 89.08%. The p-value is lesser than 0.05 for “T on,” “R,” and interaction between “GV” and “R,” which depicts that the factors are influencing the GRG.

Response table for GRG

| Level | GV | T on | T off | WF | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.670 | 0.545 | 0.662 | 0.629 | 0.527 |

| 2 | 0.615 | 0.656 | 0.630 | 0.603 | 0.654 |

| 3 | 0.589 | 0.673 | 0.581 | 0.641 | 0.692 |

| Delta | 0.081 | 0.128 | 0.081 | 0.038 | 0.165 |

| Rank | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

The bold values show the optimum levels.

In contrast, the value of “p” is greater than 0.05 for GV, T off, and interaction between GV and T off, which indicates that the factors are insignificant on GRG. The Fisher’s F-test was utilized in addition to the p-value to analyze the process factors, and it proved that they had a significant effect on the response. According to Fisher’s F-test, its impact is determined to be significant if the computed value of the F-ratio is more than the tabulated F-value.

At a 5% level of significance, the F-values from the table are F 0.05,2,10 = 4.10 and F 0.05,4,10 = 3.48. It is clear from Table 5 that the percentages of the “T on,” “R,” and interaction between “GV” and “R” are significant. In contrast, GV, T off, and the interaction between GV and T off are insignificant. As a result, it is observed from ANOVA Table 5 that the variables “WF” and the interaction between “GV” and “WF” were combined into the error term. From the experiments conducted, “R” has the greatest impact on GRG (28.22%), followed by T on (18.18%), the interaction between “GV” and “R” (17.96%), the interaction between GV and T off (12.13%), GV (6.37%), and T off (6.22%). The contribution of “WF” and interaction between “GV” and “WF” is very less, so it is pooled up with the error term.

4.4.4 Confirmation experiments

The confirmation experiments and prediction of GRG are carried out using the optimum variables. The optimal variables are found by analyzing the experimental data. The parameters at level GV1, T on3, T off1, WF3, and R 3, which are “GV” of 30 V, “T on” of 10 µs, “T off” of 2 µs, “WF” of 8 m/min, and “R” of 9%, are the most optimal variables for achieving the highest GRG, as shown in Figure 8 and response Table 6. The experimental GRG is 0.86, while the predicted GRG is 0.84.

ANOVA for GRG

| Source of variation | DoE | Seq SS | Adj MS | F | P | Contribution (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GV | 2 | 0.030 | 0.015 | 2.92 | 0.101 | 6.37 |

| T on | 2 | 0.086 | 0.043 | 8.33 | 0.007 | 18.18 |

| T off | 2 | 0.030 | 0.015 | 2.85 | 0.105 | 6.22 |

| R | 2 | 0.134 | 0.067 | 12.93 | 0.002 | 28.22 |

| GV × T off | 4 | 0.058 | 0.014 | 2.78 | 0.087 | 12.13 |

| GV × R | 4 | 0.085 | 0.021 | 4.11 | 0.032 | 17.96 |

| Pooled error | 10 | 0.052 | 0.005 | 10.92 | ||

| Total | 26 | 0.475 | 100.00 |

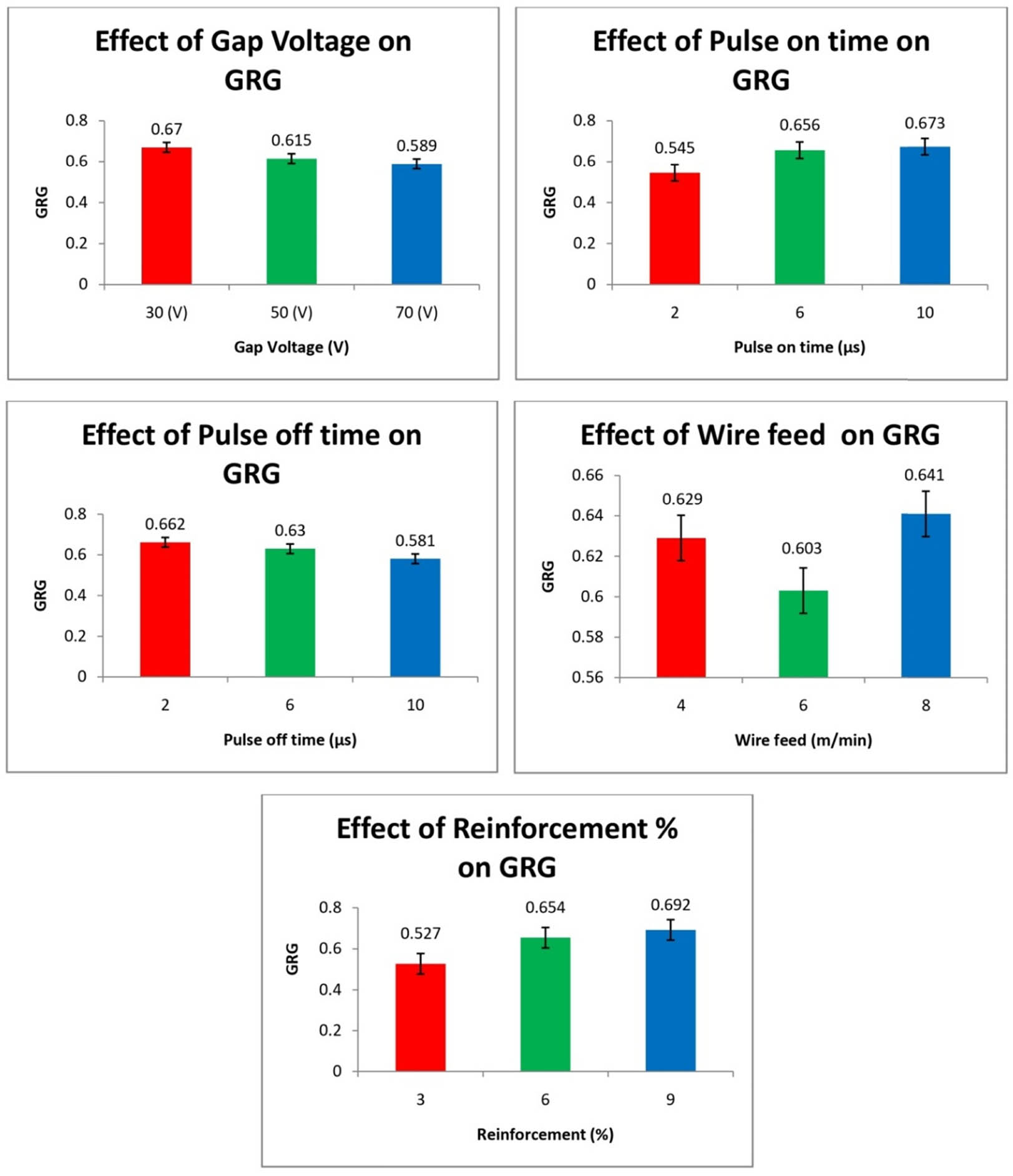

4.5 Impact of machining parameters on GRG

Figure 9 displays the impact of the cutting variables on GRG. The best machining variable for WEDM machining was obtained at a “GV” of 30 V, “T on” of 10 µs, a “T off” of 2 µs, “WF” of 8 m/min, and an “R” of 9 wt%. If “T on” is longer, more discharge energy is released, resulting in a more powerful explosion and deep craters on the work piece’s surface.

Impact of the cutting variables on GRG.

Deep craters imply significant metal loss rates and poor surface quality. To achieve better material removal rates, larger values of pulse on time should be used [41,42,43,44,45]. SR reduces as “T on” decreases. The finish cut of WEDM is affected by the SR. Higher “T on” results in greater SR owing to the transmission of more thermal energy, which causes deeper discharge craters on the specimen [46]. The findings of the experiment show that MRR increases as the “T off” decreases. Increased “T off” results in decreased cutting velocity due to an increase in non-cutting time. A longer “T off” results in a narrower gap, but it also provides a longer flushing time to clear the debris in the gap. A longer “T off” is always used to prevent wire rupture and to eliminate the aberrant process. When the pulse off time is insufficient as compared to on time, it will cause erratic cycling and retraction of the advancing servomotors, slowing down the operation [47].

Spark discharge happens more readily under the same gap when the voltage is higher because the electric field is stronger at higher voltages. Lower voltage can provide enough energy to melt the dielectric particles around it [48,49]. As the “GV” increases, the SR decreases. This is a fascinating phenomenon. Lower “GV” can provide enough energy to melt the surrounding dielectric particles and create a slew of projecting peaks. High voltage, on the other hand, results in a smoother surface. Increased GV results in increased electrostatic force, which causes wire wrapping during the discharge process. As the GV increases, the SR decreases [50].

“WF” is a neutral input parameter. “WF” should be chosen in such a way that it does not break the wire. The MRR increases as the wire speed increases. Increasing the “WF” may lower the stiffness of the wire during the discharging process [51].

In a nutshell, the results of this investigation agreed with those found in the literature. Even though the research was conducted on diverse materials, the results were consistent [52,53]. When the wt% of “R” increases, the SR of the MMC rises slowly. Furthermore, increasing the weight percent of the “R” increases the SR, which may be due to higher MMC hardness [54].

4.6 Mathematical models

It is always necessary to generate connectivity between input and response variables to clearly understand the process characteristics [55]. In the current study, the linear regression equation for MRR, SR (Ra), and GRG have been fitted with GV, T on, T off, WF, and R% as the process parameters. The fitted equations developed through linear regression equations using Minitab statistical software for the LM6/fly ash composites are presented in Equations (7)–(9).

The adequacy of the developed mathematical models was statistically checked through the ANOVA [56,57], which obviously show the competence for the proposed mathematical models of WEDM characteristics of LM6/fly ash composites.

5 Conclusion

The GRA for simultaneous minimization of SR (Ra) and the maximization of MRR in WEDM of LM6/fly ash has been discussed in this manuscript. The optimum number of experiments were planned as per Taguchi’s L27 OA and the linear regression model of WEDM characteristics, namely, SR (Ra) and MRR were constructed in terms of GV, T on, T off, WF, and R%. The fitted mathematical models were statistically tested through the ANOVA at 95% confidence level.

The findings of the experimental and statistical studies are as follows:

Stir casting, a low-cost technique was used for manufacturing composites made of LM6 and fly ash.

Optical microscopy images revealed that the fly ash was incorporated uniformly throughout the matrix.

The composite’s hardness improved with an increase in R; the densities of the composites dropped as the wt% of fly ash increases.

WEDM studies were conducted using Taguchi’s DoE and analyzed using GRA.

It has been found that during the machining of this composite, “GV” of 30 V, “T on” of 10 µs, “T off” of 2 µs, “WF” of 8 m/min, and “R” of 9% are the optimal machining variables for getting larger MRR and smaller SR simultaneously.

The predicted and experimental GRG are 0.84 and 0.86, respectively.

It can be clearly stated that the optimal setting of machine parameters was found, which allows machining of LM6/fly ash composites with the required surface quality without defects. These optimal settings may be useful to the WEDM industries involved in developing the machine pre-set values for machining composite materials. The GRA can be implemented for the investigation of other responses, viz. cutting rate, geometrical error, residual stresses, etc. Future work may focus on optimizing the WEDM process for machining other types of materials or other sets of parameters and performance measures.

-

Funding information: The authors extend their appreciation to King Saud University for funding this work through the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSP2024R164), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This article was co-funded by the European Union under the REFRESH - Research Excellence For Region Sustainability and High-tech Industries project number CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048 via the Operational Programme Just Transition and has been done in connection with project Students Grant Competition SP2024/087 “Specific Research of Sustainable Manufacturing Technologies” financed by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports and Faculty of Mechanical Engineering VŠB-TUO.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Conceptualization: CSR and JUP; methodology: SJJ and SS; validation, formal analysis, and investigation: CSR, SJJ, SRG, ESAN, and RC; writing - original draft and preparation: CSR; writing - review and editing: JUP, SRG, ESAN, and RC; and visualization and supervision: JUP, SRG, ESAN, and RC.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The data presented in this study are available through email upon request to the corresponding author.

References

[1] Mahesh KV, Venkatesh CV. A comprehensive review on material selection, processing, characterization and applications of aluminium metal matrix composites. Mater Res Express. 2019;6:072001.10.1088/2053-1591/ab0ee3Search in Google Scholar

[2] Shanmugavel R, Chinthakndi N, Selvam M, Madasamy N, Shanmugakani SK, Nair A, et al. Al-Mg-MoS2 reinforced metal matrix composites: Machinability characteristics. Materials. 2022;15:4548.10.3390/ma15134548Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Udaya Prakash J, Jebarose Juliyana S, Saleem M, Moorthy TV. Optimisation of dry sliding wear parameters of aluminium matrix composites (356/B4C) using Taguchi technique. Int J Ambient Energy. 2021;42(2):140–2.10.1080/01430750.2018.1525590Search in Google Scholar

[4] Jebarose Juliyana S, Udaya Prakash J, Čep R, Karthik K. Multi-objective optimization of machining parameters for drilling LM5/ZrO2 composites using grey relational analysis. Materials. 2023;16(10):3615.10.3390/ma16103615Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Telang AK, Rehman A, Dixit G, Das S. Alternate materials in automobile brake disc applications with emphasis on Al composites–a technical review. J Eng Res Stud. 2010;1(1):35–46.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Ananth S, Udaya Prakash J, Jebarose Juliyana S, Sarala Rubi C, Divya Sadhana A. Effect of process parameters on WEDM of Al – Fly ash composites using Taguchi technique. Materials-today-proceedings. 2021;39(Part 4):1786–90.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.07.615Search in Google Scholar

[7] Davim JP, editor. Machining of metal matrix composites. London: Springer; 2012.10.1007/978-0-85729-938-3Search in Google Scholar

[8] Al-Shayea A, Abdullah FM, Noman MA, Kaid H, Abouel Nasr E. Studying and optimizing the effect of process parameters on machining vibration in turning process of AISI 1040 steel. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2020;2020:1–5.10.1155/2020/5480614Search in Google Scholar

[9] Sarala Rubi C, Udaya Prakash J, Rajkumar C, Mohan A, Muthukumarasamy S. Optimization of process variables in drilling of LM6/fly ash composites using Grey-Taguchi method. Materials-Today-Proceedings. 2022;62(10):5894–8.10.1016/j.matpr.2022.04.627Search in Google Scholar

[10] Juliyana SJ, Prakash JU, Salunkhe S, Hussein HMA, Gawade SR. Mechanical characterization and microstructural analysis of hybrid composites (LM5/ZrO2/Gr). Crystals. 2022;12(9):1207.10.3390/cryst12091207Search in Google Scholar

[11] Sharma DK, Mahant D, Upadhyay G. Manufacturing of metal matrix composites: a state of review. Mater Today: Proc. 2020;26:506–19.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.12.128Search in Google Scholar

[12] Ho KH, Newman ST, Rahimifard S, Allen RD. State of the art in wire electrical discharge machining (WEDM). Int J Mach Tools Manuf. 2004;44:1247–59.10.1016/j.ijmachtools.2004.04.017Search in Google Scholar

[13] Milton Peter J, Udaya Prakash J, Moorthy TV. Optimization of WEDM process parameters of hybrid composites (A413/B4C/Fly Ash) using grey relational analysis. Appl Mech Mater. 2014;592:658–62.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.592-594.658Search in Google Scholar

[14] Gupta NK, Somani N, Prakash C, Singh R, Walia AS, Singh S, et al. Revealing the WEDM process parameters for the machining of pure and heat-treated titanium (Ti-6Al-4V) alloy. Materials. 2021;14:2292.10.3390/ma14092292Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Sivaprakasam P, Udaya Prakash J, Hariharan P. Enhancement of material removal rate in magnetic field-assisted micro electric discharge machining of AMCs. Int J Ambient Energy. 2022;43(1):584–9.10.1080/01430750.2019.1653979Search in Google Scholar

[16] Benedict GF. Electrical discharge machining (EDM), NonTraditional Manufacturing Processes. New York & Basel: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1987. p. 231–32.10.1201/9780203745410-16Search in Google Scholar

[17] Jameson EC. Electrical discharge machining. Southfield, MI, USA: Society of Manufacturing Engineers; 2001.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Jebarose Juliyana S, Udaya Prakash J, Salunkhe S. Optimisation of wire EDM process parameters using Taguchi technique for machining of hybrid composites. Int J Mater Eng Innov. 2022;13(3):257–71.10.1504/IJMATEI.2022.125110Search in Google Scholar

[19] Prakash JU, Sivaprakasam P, Garip I, Jebarose Juliyana S, Elias G, Kalusuraman G, et al. Wire electrical discharge machining (WEDM) of hybrid composites (Al-Si12/B4C/Fly Ash). J Nanomaterials. 2021;2021:1–9.10.1155/2021/2503673Search in Google Scholar

[20] Vates UK. Wire-EDM process parameters and optimization. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Sarala Rubi C, Udaya Prakash J, Jebarose Juliyana S, Čep R, Salunkhe S, Kouril K, et al. Comprehensive review on wire electrical discharge machining: a nontraditional material removal process. Front Mech Eng. 2024;10:1–16.10.3389/fmech.2024.1322605Search in Google Scholar

[22] Udaya Prakash J, Sivaprakasam P, Jebarose Juliyana S, Ananth S, Sarala Rubi C, Divya Sadhana A. Multi-objective optimization using grey relational analysis for wire EDM of aluminium matrix composites. Mater Today: Proc. 2023;72(4):2395–2401.10.1016/j.matpr.2022.09.415Search in Google Scholar

[23] Basak A, Pramanik A, Prakash C, Shankar S, Debnath S. Understanding the micro-mechanical behaviour of recast layer formed during WEDM of titanium alloy. Metals. 2022;12:188.10.3390/met12020188Search in Google Scholar

[24] Alis A, Abdullah B, Abbas NM. Influence of machine feed rate in WEDM of Ti-6Al-4V with constant current (6A) using brass wire. Proc Eng. 2012;41:1812–7.10.1016/j.proeng.2012.07.388Search in Google Scholar

[25] Gupta K, Gupta MK. Developments in nonconventional machining for sustainable production: A state-of-the-art review. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part C J Mech Eng Sci. 2019;233:4213–32.10.1177/0954406218811982Search in Google Scholar

[26] Magabe R, Sharma N, Gupta K, Paulo Davim J. Modelling and optimization of Wire-EDM parameters for machining of Ni55.8Ti shape memory alloy using hybrid approach of Taguchi and NSGA-II. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2019;102:1703–17.10.1007/s00170-019-03287-zSearch in Google Scholar

[27] Davim JP, editor. Computational methods and production engineering. Duxford: Wood Head Publishing; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Surappa MK, Rohatgi PK. Preparation and properties of cast aluminium-ceramics particle composites. J Mater Sci. 1981;16:983–93.10.1007/BF00542743Search in Google Scholar

[29] Miracle DB. Metal matrix composites – From science to technological significance. Compos Sci Technol. 2005;65:2526–40.10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.05.027Search in Google Scholar

[30] Palanikumar K. Cutting parameters optimization for surface roughness in machining of GFRP composites using Taguchi’s method. J Reinforced Plast Compos. 2006;25(16):1739–51.10.1177/0731684406068445Search in Google Scholar

[31] Davim JP, editor. Design of experiments in production engineering. New Delhi: Springer; 2016.10.1007/978-3-319-23838-8Search in Google Scholar

[32] Davim JP, editor. Statistical and computational techniques in manufacturing. Heidelberg: Springer; 2012.10.1007/978-3-642-25859-6Search in Google Scholar

[33] Rajan TPD, Pillai RM, Pai BC, Satyanarayana KG, Rohatgi PK. Fabrication and characterization of Al–7Si–0.35Mg/fly ash metal matrix composites processed by different stir casting routes. Composites Sci Technol. 2007;67:3369–77. Elsevier.10.1016/j.compscitech.2007.03.028Search in Google Scholar

[34] Mahendra KV, Radhakrishna K. Fabrication of Al-4.5% Cu alloy with fly ash metal matrix composites and its characterization. Mater Science-Poland. 2007;25(1):57–68.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Ramachandra M, Rradakrishna K. Synthesis – microstructure-mechanical properties-wear and corrosion behavior of an Al-Si (12%) - fly ash metal matrix composite. J Mater Sci. 2005;40:5989–97.10.1007/s10853-005-1303-6Search in Google Scholar

[36] Abhilash PM, Chakradhar D. Prediction and analysis of process failures by ANN classification during wire-EDM of Inconel 718. Adv Manuf. 2020;8(4):519–36.10.1007/s40436-020-00327-wSearch in Google Scholar

[37] Sadhana AD, Prakash JU, Sivaprakasam P, Ananth S. Wear behaviour of aluminium matrix composites (LM25/Fly Ash) – A Taguchi approach. Mater Today: Proc. 2020;33(7):3093–6.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.03.684Search in Google Scholar

[38] Sarala Rubi C, Udaya Prakash J. Drilling of hybrid aluminum matrix composites using grey-Taguchi method. INCAS Bull. 2020;12(1):167–74.10.13111/2066-8201.2020.12.1.16Search in Google Scholar

[39] Jebarose Juliyana S, Udaya Prakash J, Rubi CS, Salunkhe S, Gawade SR, Abouel Nasr ES, et al. Optimization of wire EDM process parameters for machining hybrid composites using grey relational analysis. Crystals. 2023;13:1549.10.3390/cryst13111549Search in Google Scholar

[40] Udaya Prakash J, Jebarose Juliyana S, Salunkhe S, Gawade SR, Nasr ESA, Kamrani AK. Mechanical characterization and microstructural analysis of stir-cast aluminum matrix composites (LM5/ZrO2). Crystals. 2023;13:1220.10.3390/cryst13081220Search in Google Scholar

[41] Jebarose Juliyana S, Udaya Prakash J. Optimization of machining parameters for wire EDM of AMCs (LM5/ZrO2) using Taguchi technique. INCAS Bull. 2022;14(1):57–68.10.13111/2066-8201.2022.14.1.5Search in Google Scholar

[42] Jebarose Juliyana S, Udaya Prakash J, Divya Sadhana A, Sarala Rubi C. Multi-objective optimization of process parameters of wire EDM for machining of AMCs (LM5/ZrO2) using grey relational analysis. Mater Today: Proc. 2022;52(3):1494–8.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.11.213Search in Google Scholar

[43] Hourmand M, Farahany S, Sarhan AA, Noordin MY. Investigating the electrical discharge machining (EDM) parameter effects on Al-Mg2Si metal matrix composite (MMC) for high material removal rate (MRR) and less EWR–RSM approach. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2015;77(5):831–8.10.1007/s00170-014-6491-2Search in Google Scholar

[44] Kumar K, Agarwal S. Multi-objective parametric optimization on machining with wire electric discharge machining. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2012;62(5):617–33.10.1007/s00170-011-3833-1Search in Google Scholar

[45] Bagherian AR, Teimouri R, GhasemiBaboly M, Leseman Z. Application of Taguchi, ANFIS and grey relational analysis for studying, modeling and optimization of wire EDM process while using gaseous media. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2014;71(1):279–95.10.1007/s00170-013-5467-ySearch in Google Scholar

[46] Aggarwal V, Pruncu CI, Singh J, Sharma S, Pimenov DY. Empirical investigations during WEDM of Ni-27Cu-3.15Al-2Fe-1.5Mn based superalloy for high temperature corrosion resistance applications. Materials. 2020;13(16):3470.10.3390/ma13163470Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Davim JP, editor. Nontraditional machining processes. London: Springer; 2013.10.1007/978-1-4471-5179-1Search in Google Scholar

[48] Guo ZN, Wang X, Huang ZG, Yue TM. Experimental investigation into shaping particle-reinforced material by WEDM-HS. J Mater Process Technol. 2002;129(1–3):56–9.10.1016/S0924-0136(02)00575-7Search in Google Scholar

[49] Rao PS, Ramji K, Satyanarayana B. Effect of WEDM conditions on surface roughness: A parametric optimization using Taguchi method. Int J Adv Eng Sci Technol. 2011;6(1):41–8.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Pramanik A, Islam MN, Basak AK, Dong Y, Littlefair G, Prakash C. Optimizing dimensional accuracy of titanium alloy features produced by wire electrical discharge machining. Mater Manuf Process. 2019;34(10):1083–90.10.1080/10426914.2019.1628259Search in Google Scholar

[51] Gopal PM, Prakash KS, Jayaraj S. WEDM of Mg/CRT/BN composites: Effect of materials and machining parameters. Mater Manuf Process. 2018;33(1):77–84.10.1080/10426914.2017.1279316Search in Google Scholar

[52] Ramakrishnan R, Karunamoorthy L. Modeling and multi-response optimization of Inconel 718 on machining of CNC WEDM process. J Mater Process Technol. 2008;207(1–3):343–9.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2008.06.040Search in Google Scholar

[53] Udaya Prakash J, Rajkumar C, Jayavelu S, Sivaprakasam P. Effect of wire electrical discharge machining parameters on various tool steels using grey relational analysis. Int J Veh Struct Syst. 2023;15(2):203–6. 10.4273/ijvss.15.2.11.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Udaya Prakash J, Jebarose Juliyana S, Pallavi P, Moorthy TV. Optimization of wire EDM process parameters for machining hybrid composites (356/B4C/Fly Ash) using Taguchi technique. Mater Today: Proc. 2018;5(2):7275–83.10.1016/j.matpr.2017.11.395Search in Google Scholar

[55] Davim JP, editor. Nonconventional machining. Berlin: DE Gruyter; 2023.10.1515/9783110584479Search in Google Scholar

[56] Montgomery DC. Design and analysis of experiments. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Myers RH, Montgomery DC, Anderson-cook CM. Response surface methodology: Process and product optimization using designed experiments. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2009.Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective