Abstract

Mo2C layer was generated on the diamond surface via vacuum micro-evaporating, which was used as the reinforcement particles to fabricate diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering (SPS). The effect of evaporation parameters on the forming of Mo2C, and the holding time on diamond/Cu composites fabrication is studied. Combined with the experiment and finite element analysis (FEA), the holding time on diamond/Cu composites influence on the thermal conductivity (TC) of composites is further discussed. The results show that the Mo2C area on the diamond surface would gradually enlarge and cover the diamond surface evenly with the increment in evaporation time and temperature, better vacuum micro-evaporating parameters were given as 1,000°C for 60 min. The fractures in the diamond/Cu composites are mainly ductile fractures on copper and diamond falling out from the Mo2C interface. It was found that sintering time would significantly influence the dissipation property of diamond/Cu composites. A comprehensive parameter for SPS was obtained at 900°C, 80 MPa for 10 min, the relative density (RD) and TC of the composites obtained under the parameter were 96.13% and 511 W/(m K). A longer sintering time would damage the Mo2C interlayer and further decrease the bonding between copper matrix and diamond particles, which would lower the RD and TC of composites. It can be obtained from the comparison of simulation results and experimental results that the FEA result is closer to the experimental results due to the gaps with low heat conduction, and the air in the gaps is added in the simulation process.

1 Introduction

Heat sink materials nowadays are becoming widely used in electronic packaging and other related fields. As the fast developments in electronics and communication, the demand for higher-integrated microchips and miniaturized electronics is highly increasing. Therefore, a higher requirement for heat dissipation is urgently needed. However, the first and second generations of heat sink materials available like Al2O3, SiC, etc., with a thermal conductivity (TC) of 210–300 W/(m K) [1], cannot meet the increasing heat dissipation demands. Fortunately, the interdisciplinary developments between materials and electronics have made it possible to build functional materials or composites with high thermal-conducting ability. In this context, an ideal composite with appropriate thermal properties is expected to be massively needed. Diamond/Cu composites are considered an ideal heat sink material because it is designed to combinate TC of diamond and Cu. The TC of synthesized diamond can range from 1,500 to 2,000 W/(m K), while the Cu has an average TC of 398 W/(m K). However, the TC of the composites fabricated is far lower than expected [2,3,4]. Diamond and copper determines neither to react with nor solute to each other. Holes, gaps, cracks, and other defects existing in the diamond/Cu composites are mainly caused by the non-wettability and will significantly influence not only its mechanical properties but also the thermal conducting ability [5].

Compared with mere mechanical interfacial bonding, the bonding created through chemical reaction and solid solution can be more effective in improving interfacial bonding qualities [6,7]. Quantities of pores and holes in the composites can be reduced and the mechanical properties could be developed through the strong-bonded interfaces, and these are the reasons why the researchers are eager to find out the interface modifying methods between diamond and Cu matrix. Pre-alloying of Cu matrix [8] is one method that can obtain a better combination between Cu and diamond. Ti [9,10], B [11,12], Sn [13], Zr [14], Ag [15], carbides [16], and rare earth oxides like Sc2O3 [17] are added in the Cu matrix to strengthen the interface bonding because the additional elements can react or form solid solution in Cu matrix. It is an effective method of developing mechanical and thermal properties. Another method of modifying the interface is to deposit a coating on the diamond surface, and the coating can act as a medium that connects the two phases with chemical bonding by either reaction or solid solution [18]. Different elements, such as W [19,20,21], Cr [6,7,22,23,24], Nb [25], Ni [20,26], Ti and its carbides [27,28,29,30], and Mo and its carbide [31,32,33,34,35,36], are coated on the diamond surface to improve the interface properties. The coating methods are considered as the most direct method to strengthen the interface bonding. Several coating methods have been used to coat on diamond surfaces. Magnetron sputtering is an effective way that can obtain a smooth, even, and thickness-adjustable interface [33], but the coating is deposited under a relatively low temperature like room temperature, where the temperature is too low to react on diamond. Electrocoating is also used for depositing metal on the diamond surface to strengthen better the interface bonding between diamond and copper matrix [25,37,38,39,40]. In addition, a new manufacturing routine of vacuum-assisted material extrusion, a sandwich structure, and interleaving of the low-temperature issue of the composites is performed to eliminate matrix voids and improve the bonding quality of deposited layers [41,42,43]. Based on the above, vacuum micro-evaporating deposition is one of the physical vapor deposition methods that deposit the metal elements in a high vacuum and high temperature condition at a relatively low cost. Energy from a high vacuum and temperature environment could be provided to highly activate metal surface atoms, which makes the elements react with the diamond to generate compounds.

Despite Mo and its carbide having the ability to significantly improve the wettability between Cu matrix and diamond as an effective interlayer [32], it still causes a reduction in the TC of the composites with an inappropriate interlayer thickness, whicih ignored the negative effect from the Mo carbide or Mo itself [35]. Meanwhile, combined finite element simulation to analyze the effect of different coating thicknesses on the TC of the composites is rare. Based on the fact, the forming mechanism and optimization processing of Mo2C coating on the diamond surface and finite element analysis (FEA) of the composites for the thermal properties need to be studied for the prediction and development. In this work, the diamond particles with Mo2C coating were fabricated by vacuum micro-deposition method, the microstructure of Mo2C-coated diamond is presented and analyzed, and the formation mechanism of Mo2C on diamond surfaces is discussed. Spark plasma sintering (SPS) is an effective way of producing diamond/Cu composites, thus, the prediction and heat dissipation properties of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites by SPS are researched as well in this work. The thickness of the Mo2C interlayer on the microstructure and the thermal performance of the diamond/Cu composites were studied by simulation and experiment.

2 Experimental method

Commercially synthesized MBD-8 diamond particles with average particle sizes of 100 μm were purchased from Whirlwind Diamond Powder Co., Ltd, Henan, China. And Mo powder with a size of 2 μm (Shanghai Chaowei Nano Co., Ltd) was used for powder coating. The diamond particles were cleaned in 10 wt% NaOH solution and 20 wt% HCl, respectively, to remove the oil and coarsen the diamond surfaces, and the diamond particles were dried after being cleaned to neutral with distilled water. Diamond particles and Mo powders with a molar ratio of 10:1 was mixed evenly at a rotating speed of 300 rpm for 2 h by planetary ball mill.

The tube furnace (TL1200, Nanjing Boyuntong Co., Ltd) was used for vacuum micro-evaporating. The ceramic crucible including the mixed powder with a molar ratio of 10:1 was put in the tube furnace, vacuumed to a pressure of ≤10−3 Pa, and heated up to gradually reach the target temperature of 1,000°C, and this temperature is held for 50–60 min. Then, the coating is plated at 980–1,020°C for 60 min. The holding procedure is then stopped and the furnace is cooled to room temperature. The Mo2C-coated diamond particles are cleaned with distilled water in the ultrasonic cleaner to wash away the Mo powder that might get exited on the surface of the diamond when heating. The coated diamond particles are then dried up.

The high-resolution transmission scanning electronic microscope (SEM, SU8220) was used to observe the further microstructure of the Mo2C-coated diamond. X-Ray diffraction (XRD, SmartLab, Rigaku UltimaIII) with a scanning range of 20–90° at a scanning speed of 4°/min was used for analyzing the phase composition of the Mo2C-coated diamond and the composites. Atomic force microscope (AFM, BRUKER) was used to study the differences in surface roughness between the original and coated diamonds. The TC of the composites was measured by laser flash TC measurement apparatus (TC-7000H, Sinku-Riko Inc., Japan). The Mo2C-coated diamonds were sent to mix with copper powder and sintered via spark plasma to make diamond/Cu composites for 10, 20, and 40 min. The process diagram of preparation of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites is shown in Figure 1.

The process diagram of preparation of Mo2C-Diamond/Cu composites.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Microstructure analysis of Mo-coated diamond

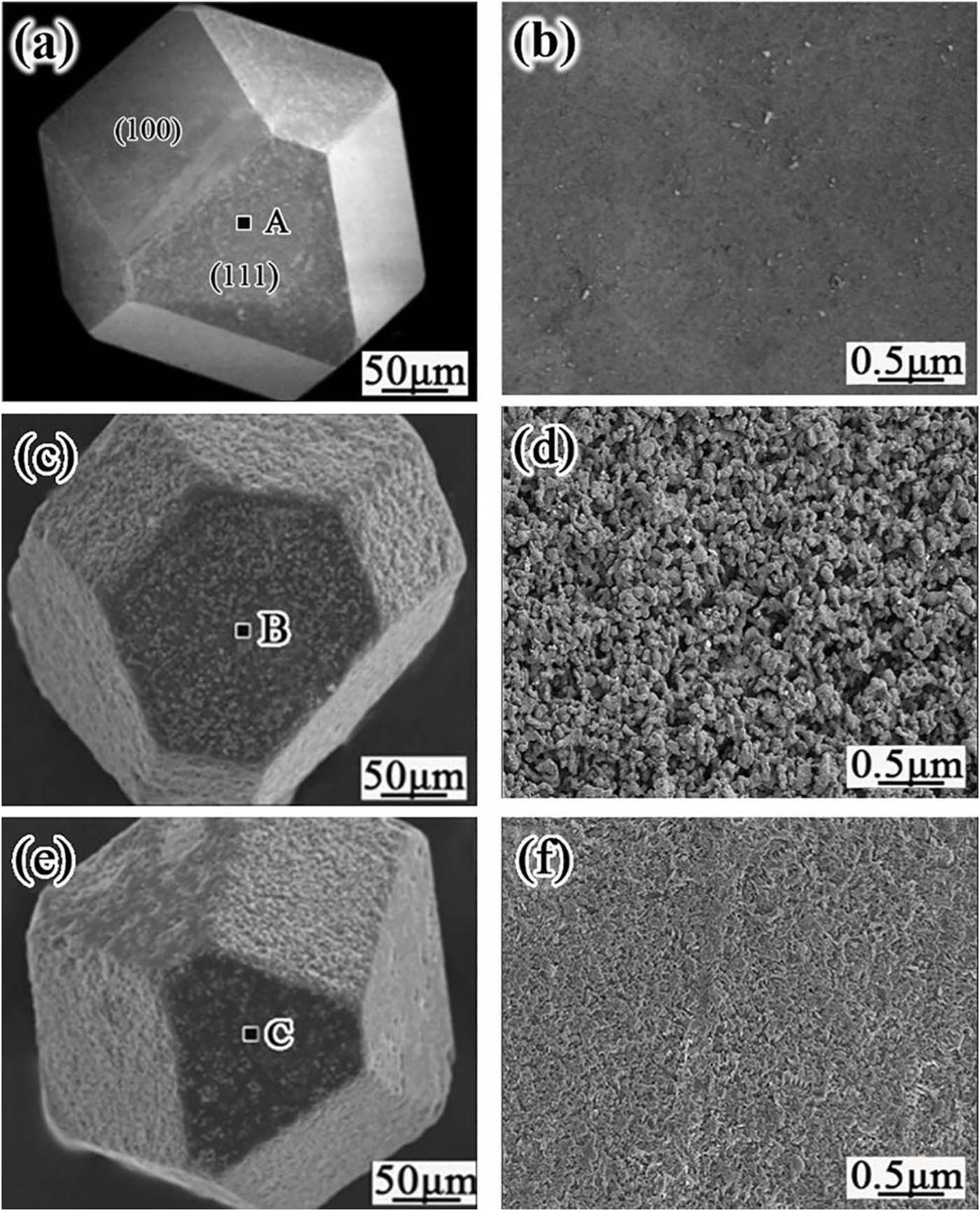

Figure 2 displays the morphologies of as-received diamond and Mo-coated ones deposited at 1,000°C with different deposition time. The as-received diamond particle has a cubic octahedral shape, which has an intact and smooth surface as a perfect crystal, as shown in Figure 2(a) and (b). Mo was deposited on the have surface at the deposition time of 50 min, as shown in Figure 2(c) and (d), the deposited areas have a grain shape, and the grain shape connects and finally covers the diamond surface uniformly. The reason this phenomenon occurs is because of the reaction between carbon and Mo. As the deposition time increases to 60 min, more Mo gas mass gathered and reacted with carbon, Mo particles are gathering on the Mo carbide surface due to the increased deposition period. Meanwhile, Mo diffuses into diamond and bonds with carbon, the grain shape expands and joins others until it became a whole which covers the diamond surface. As shown in the SEM results, the Mo-coated diamond particles at 1,000°C for 60 min are better for the surface to be nearly covered with Mo2C.

Microstructures of Mo2C-coated diamonds at 1,000°C for different deposition time: (a) as-received diamond, (b) magnified view of the region in (a), (c) deposition time of 50 min, (d) magnified view of the region in (c), (e) deposition time of 60 min, and (f) magnified view of the region in (e).

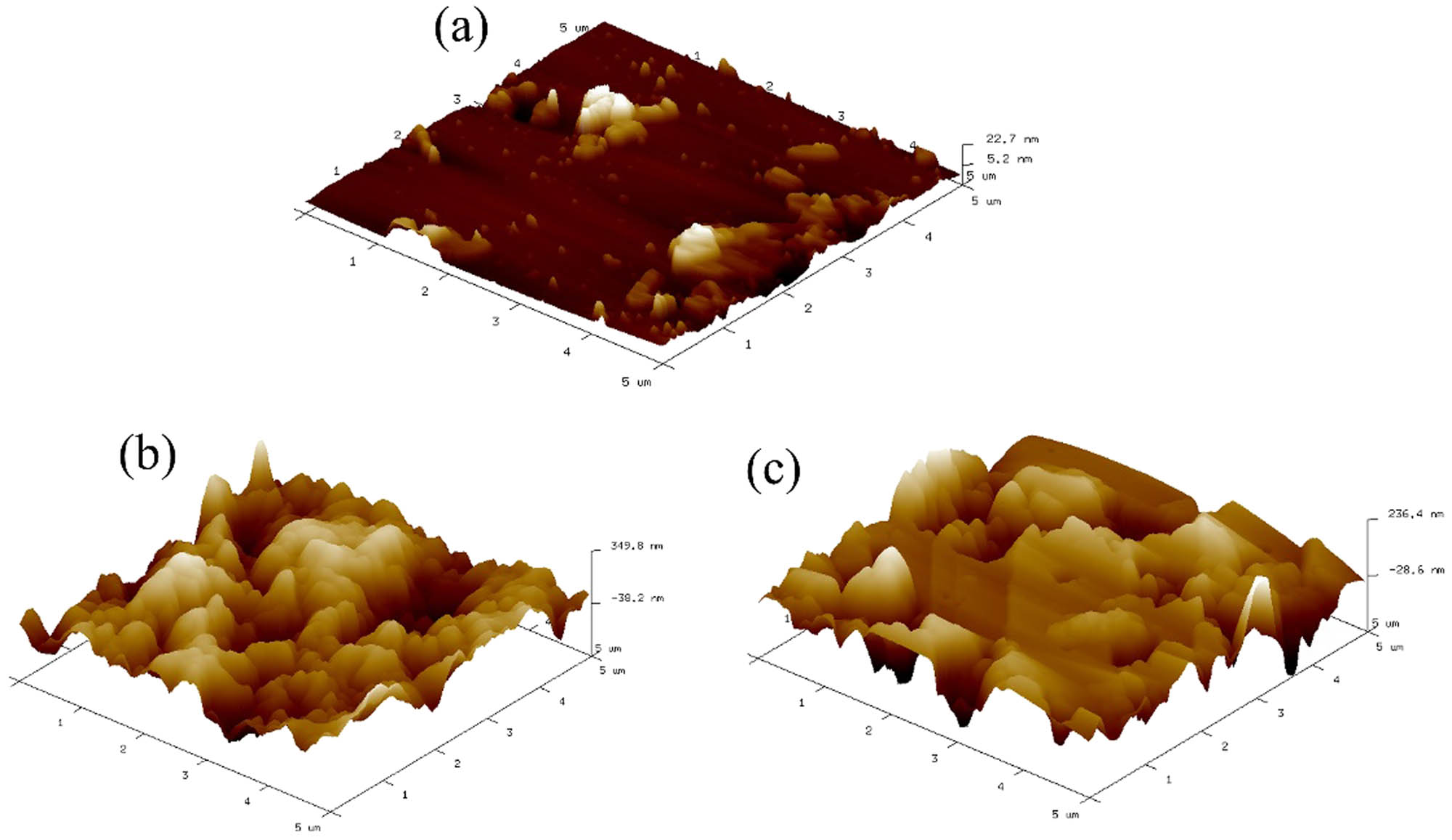

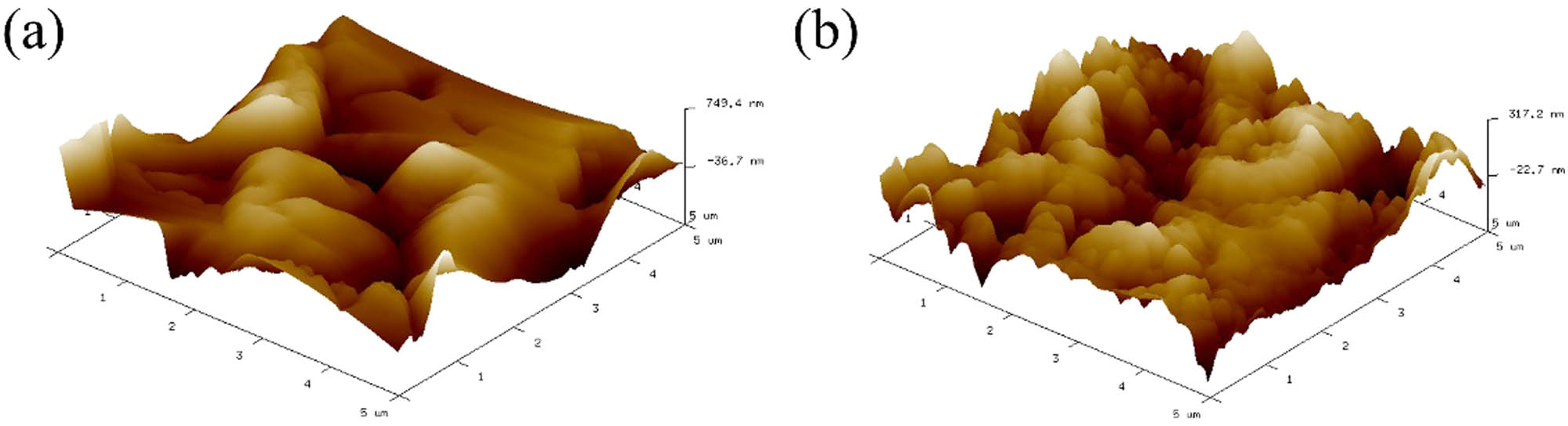

The diamond surface under different parameters was observed by AFM, as shown in Figure 3. As seen from Figure 3(a), the initial diamond particle is relatively flat as a whole, but there are also some micron level protrusions which are mainly caused by the preparation process of the diamond, it increases the surface area of the diamond and is conducive to the deposition of coating elements during vacuum micro-evaporating. Figure 3(b) is the AFM result of Mo2C-coated diamond surface with a peak height of 349.8 nm at 1,000°C for 50 min, and the diamond surface roughness changes more rapidly, the rough Mo2C-coated surface is obtained due to the irregular movement of Mo gas groups and the microscale Mo powder size. The diamond surface at 1,000°C for 60 min with obvious changes in surface morphology and numerous surface fluctuations with the peak height of 236.4 nm at the highest point, is shown in Figure 3(c). Compared to the former, the coating on the diamond surface becomes relatively flat and uniform. According to the work of Pan et al. [36], the rough and dense Mo2C surface would be easier for copper to bond and increase the shearing force between copper and Mo2C to prevent the Mo2C-coated diamonds from desquamating and debonding from the copper matrix.

AFM morphology of diamond at 1,000°C for different deposition time: (a) as-received, (b) 50 min, and (c) 60 min.

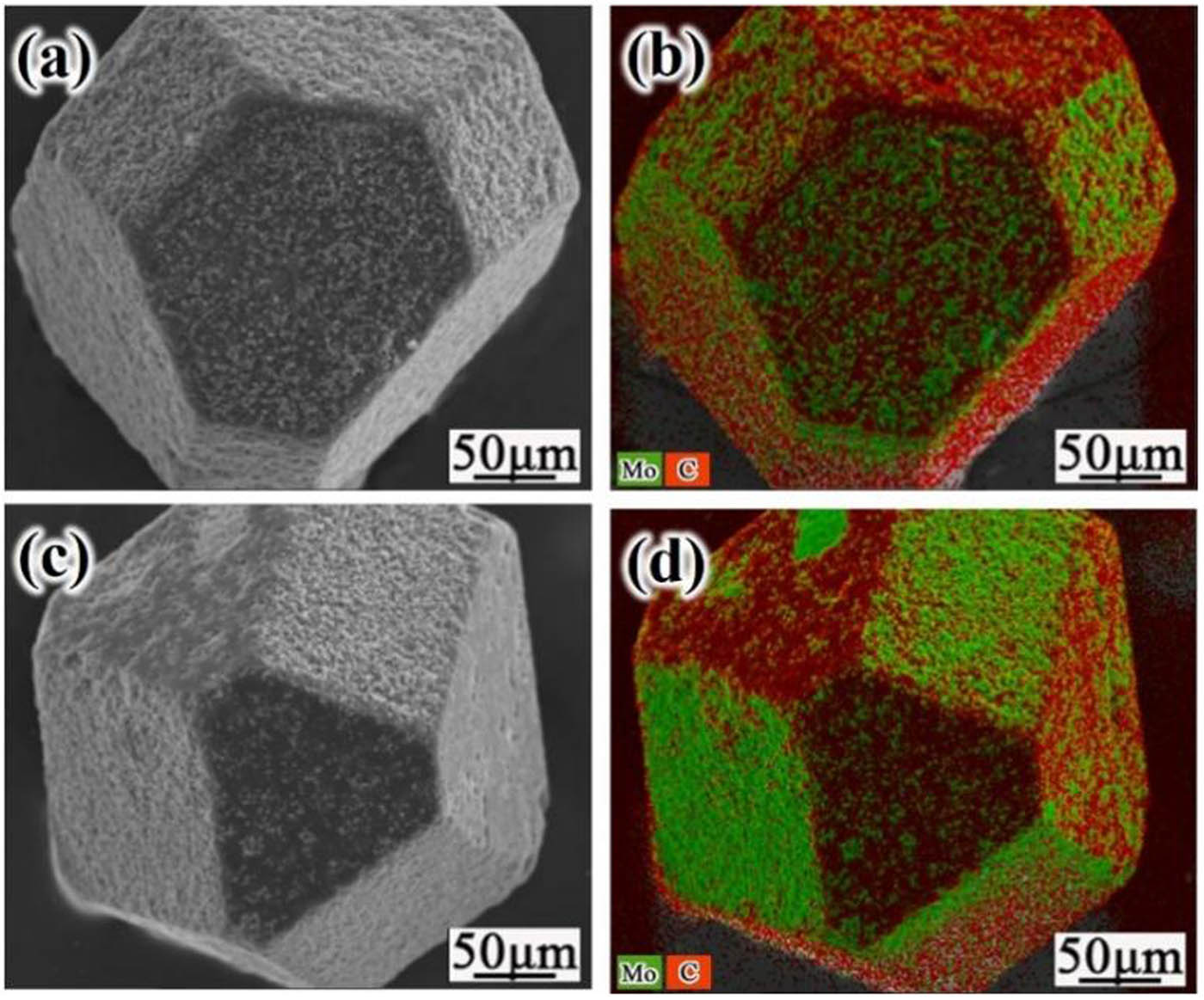

Figure 4 is an EDS analysis of Mo2C-coated diamonds at 1,000°C for different deposition time. Mo coating is completely plated on the whole diamond surface, but the surface is rugged and rough, as shown in Figure 4(a) and (b). The reason for the local agglomeration of Mo is that during the coating process, the part is too much in contact with Mo powder resulting in the aggregation of Mo molecular groups around them at the high temperature and connected as a whole. Figure 4(c) shows that the Mo coating on the diamond surface is more even and smooth. The EDS surface scanning results with a coating time of 60 min are shown in Figure 4(d), it can be seen that Mo is evenly distributed on the surface of diamond, which shows that the process parameters are conducive to the uniform preparation of Mo coating, and provides a basis for obtaining good surface quality and interface adhesion.

EDS analysis of Mo2C-coated diamonds at 1,000°C for different deposition time: (a) 50 min, (b) mapping of (a), (c) 60 min, and (d) mapping of (c).

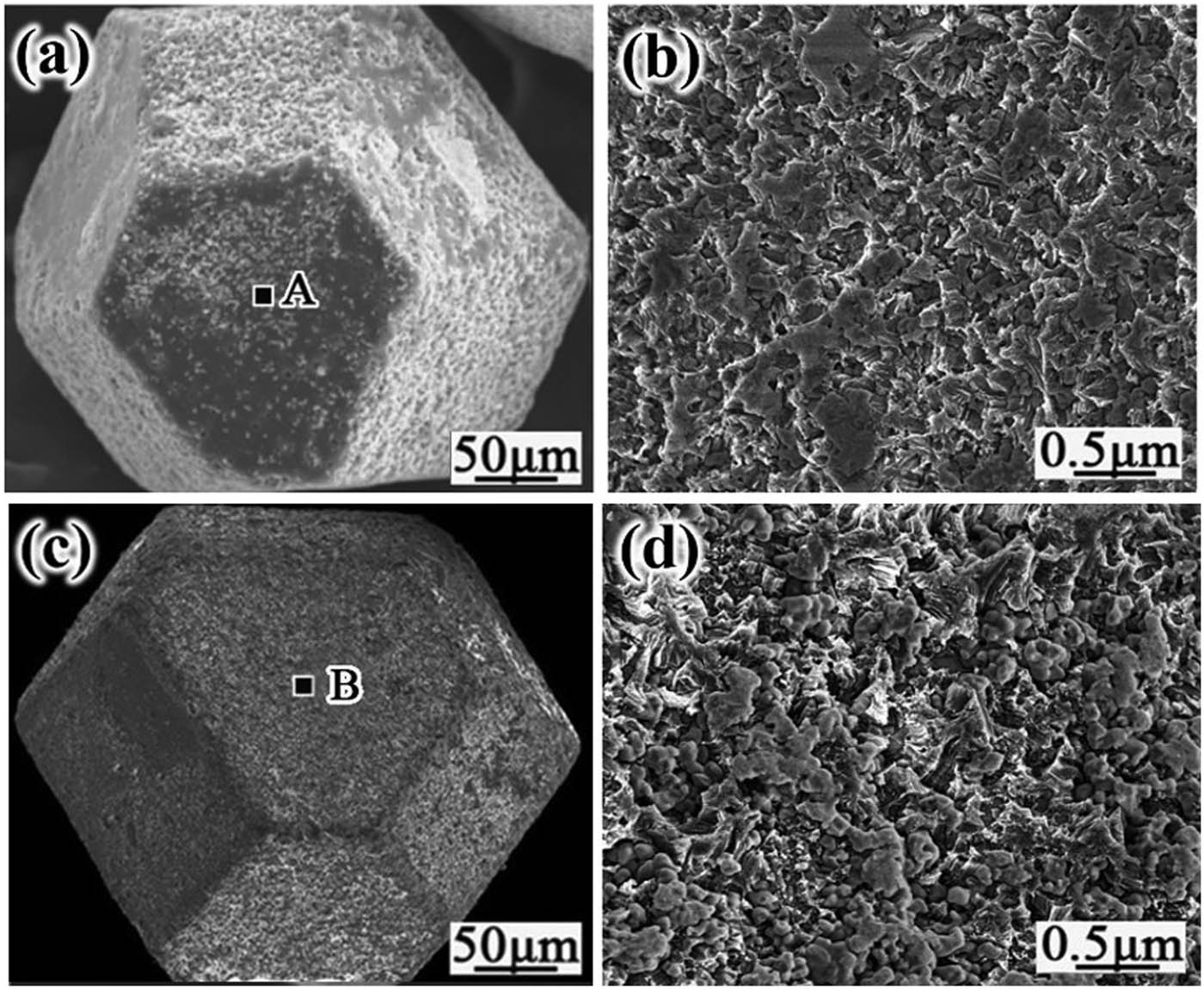

Figure 5 shows the surface morphology of Mo coated diamond deposited at different temperatures for 60 min. It is observed that the surface of diamond is in the form of gullies and rough at 980°C, the coating degree of the surface is not high, and the microstructure with transverse growth trend diffuses on the diamond surface, as shown in Figure 5(a) and (b). When the deposition temperature elevates to 1,020°C, as seen from Figure 5(c) and (d), almost all diamond surfaces have grown a coating layer, the surface massive structure of diamond continues to expand, Mo groups adhere on the coating layer, and the transverse growth between the groups is before the longitudinal growth. From the above SEM results, it can be concluded that the surface coating preferentially grows laterally under different coating temperatures, that is, a uniform and dense coating layer is preferentially obtained on the diamond. As the temperature increases, Mo preferentially combines with the diamond that is more prone to react to obtain the Mo2C interface faster, various parts of Mo groups combine to form a denser caking layer, which makes the transverse diffusion of the coating.

Microstructure of Mo2C-coated diamond at 60 min for different temperatures: (a) 980°C, (b) magnified view of the region in (a), (c) 1,020°C, and (d) magnified view of the region in (c).

Figure 6(a) shows the AFM morphology of diamond after coating at 980°C for 60 min. The surface is very flat, and the highest peak is 749.4 nm. The surface at 1,020°C gathers thicker Mo molecular groups, as shown in Figure 6(b). The maximum difference between the groups and the formed coating surface is 317.2 nm. The Mo molecular groups have fused, which is consistent with Figure 5 results. It is proved that the relatively flat coating surface will be combined with Mo particles again at 1,020°C. The reason for the phenomenon is that as the ambient temperature increases, the energy supply increases, and the Mo on the surface of diamond obtains enough energy to form Mo coating. Compared with the micro-evaporating temperature of 1,000°C, the coating at 980 and 1,020°C is not relatively dense enough. Therefore, the optimum process parameters for coating Mo on the diamond surface is 1,000°C for 60 min.

AFM morphology of Mo2C-coated diamond at different temperatures for 60 min: (a) 980°C and (b) 1,020°C.

3.2 Phase composition of Mo-coated diamond

Based on the above discussion results, the optimum parameters of Mo coated on the diamond surface is 1,000°C for 60 min, the next work only analyzes the effect of different deposition time on the phase composition of Mo coated diamond at 1,000°C. Mo will react with carbon to form carbide at a temperature of 600°C.

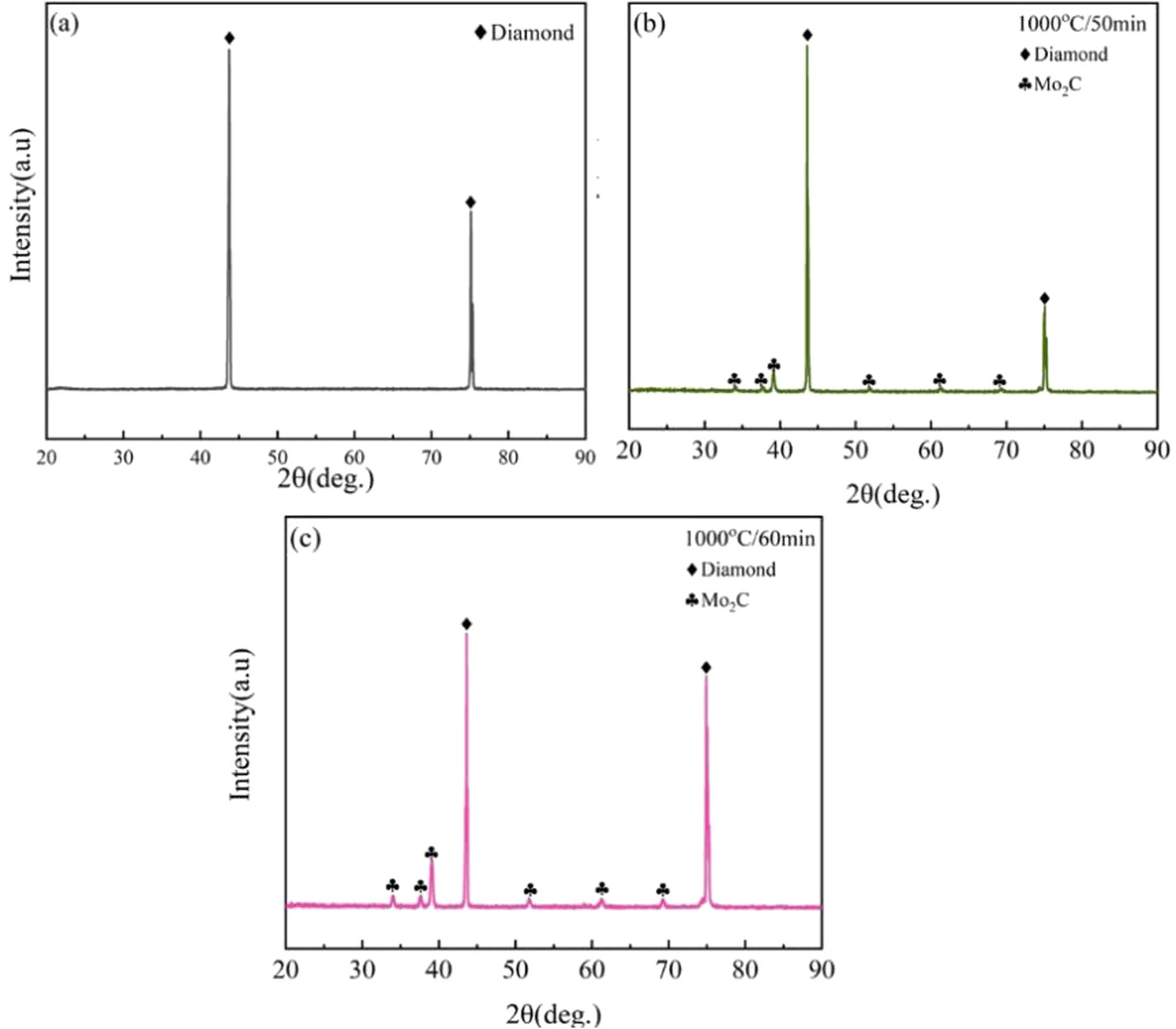

Figure 7 is the XRD analysis of Mo coated diamond at 1,000°C for different deposition time. The XRD pattern shows that the graphite phase was not detected. The high peak near 2θ = 45o specifies that this matter is diamond, which means the diamond graphitization is not an obvious phenomenon in vacuum micro-evaporating, and the Mo2C is more likely to be the main product compared with MoC through this processing under this condition according to formulas (1) and (2). Mo2C is successfully produced through deposited Mo by vacuum micro-evaporating, as shown by the Mo2C peak in Figure 7, which indicates the successful generation of Mo2C on the diamond surfaces at the deposition time of 50 min; this is due to the reaction between Mo and carbon in diamond when the reacting temperature between Mo and carbon is above 650°C as reported by Liu et al. [31].

XRD analysis of Mo coated diamond at 1,000°C for different deposition time: (a) as-received diamond, (b) 50 min, and (c) 60 min.

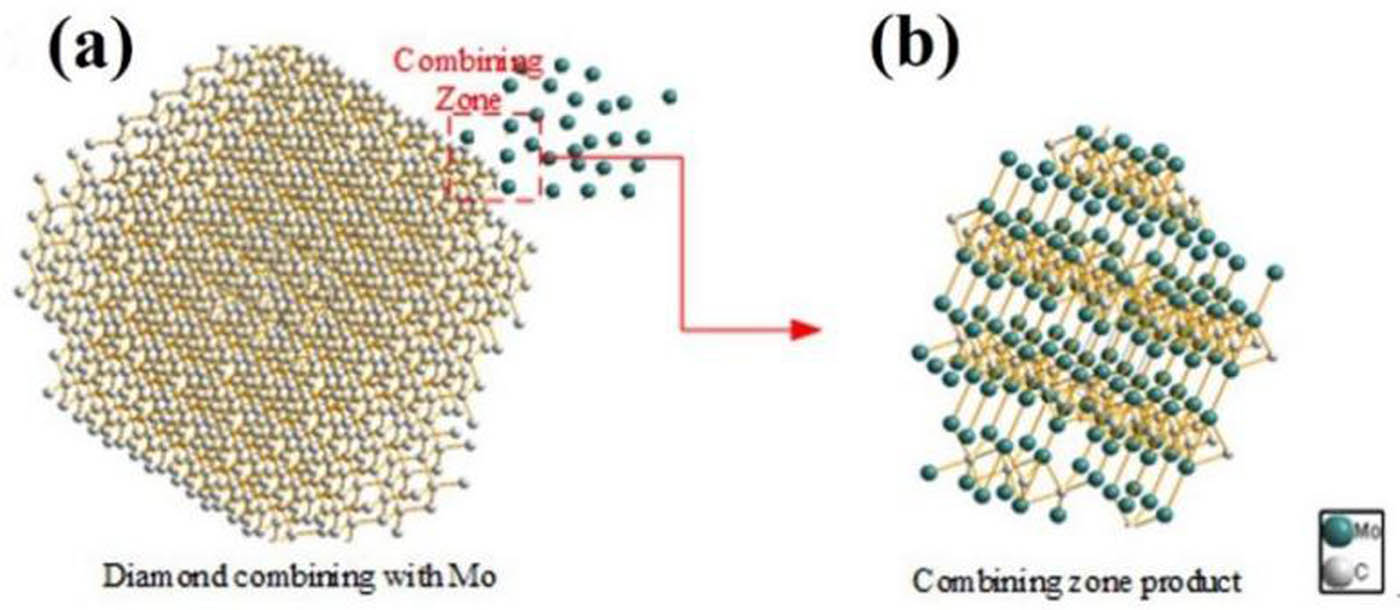

Figure 8 is the forming process of Mo2C. Mo reacts with carbon in the diamond surface, as shown in Figure 8(a). Figure 8(b) is the ideal structure of Mo2C after reacting for the structure is similar to the structure of the original diamond, which means Mo would react with carbon to form this structure with less energy. Although Mo2C has different space groups, it can be defined by comparing the experimental XRD pattern with the calculated diffraction patterns of different Mo2C structures. The crystal structure of diamond is referred to the structure of Pm1 shown in Figure 8(b) as the calculated diffraction pattern fits the experimental XRD pattern shown in Figure 7, the XRD pattern of the space structure shown in 8(b) when the sweeping angle ranges from 20–90°. The peaks of Figure 8(b) show when 2θ is 33.676, 38.707, 38.989, 52.227, 60.228, 70.247°, which can fit the experimental XRD pattern shown in Figure 8. Therefore, it can basically be ensured from the experimental XRD pattern that most Mo2C space group generated on the diamond surface is in a structure of P

The forming process of Mo2C: (a) diamond combining with Mo, and (b) combining product Mo2C.

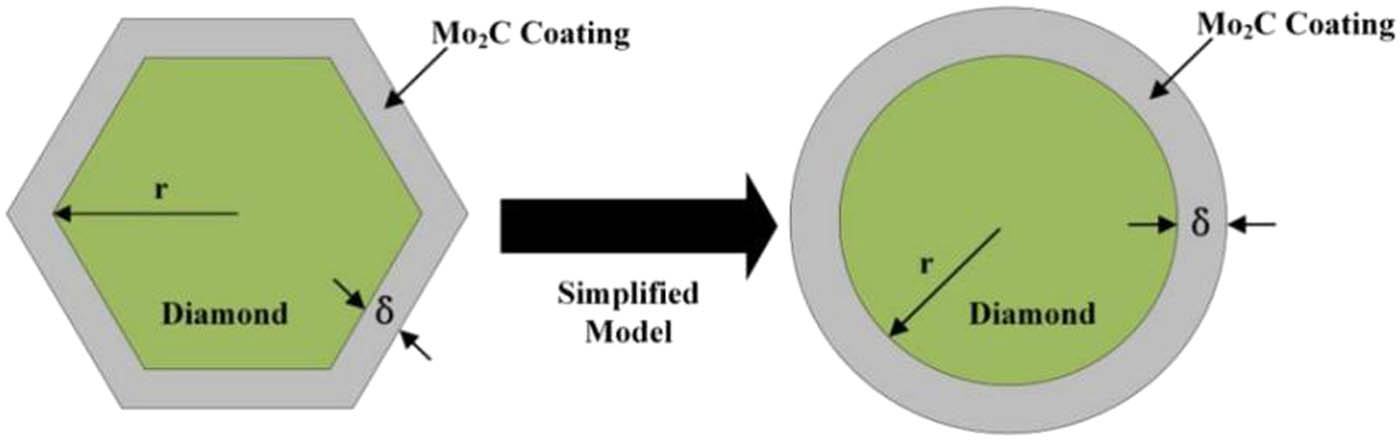

Mo2C coating thickness is calculated through the simplified model referred to in the work of Chang et al. [34] presented in Figure 9. Δm is the additional weight of diamond after being coated with Mo2C, which is measured by the gravimetric method. The measured additional weight statistics are listed in Table 1. The calculating expression is shown in formula (3).

where r stands for the average diamond radius, which could be presented by diamond particle size,

Simplified model of coating thickness on the diamond surface.

Additional weight percentage of Mo2C-coated diamond

| Temperature (°C) | Molar ratio | Time (min) | Additional weight (%) | Theoretical coating thickness (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 10:1 | 50 | 2.7690 | 176.30 |

| 60 | 4.2055 | 267.30 |

According to the morphology of Mo2C-coated diamond in Figure 2 and theoretical thickness values at different evaporating time, the amount of Mo deposited at 1,000°C for 50 min is not dense. Therefore, the Mo2C-coated diamonds at 1,000°C for 60 min are more suitable to be selected to fabricate diamond/Cu composites by SPS.

3.3 Compactness analysis of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites

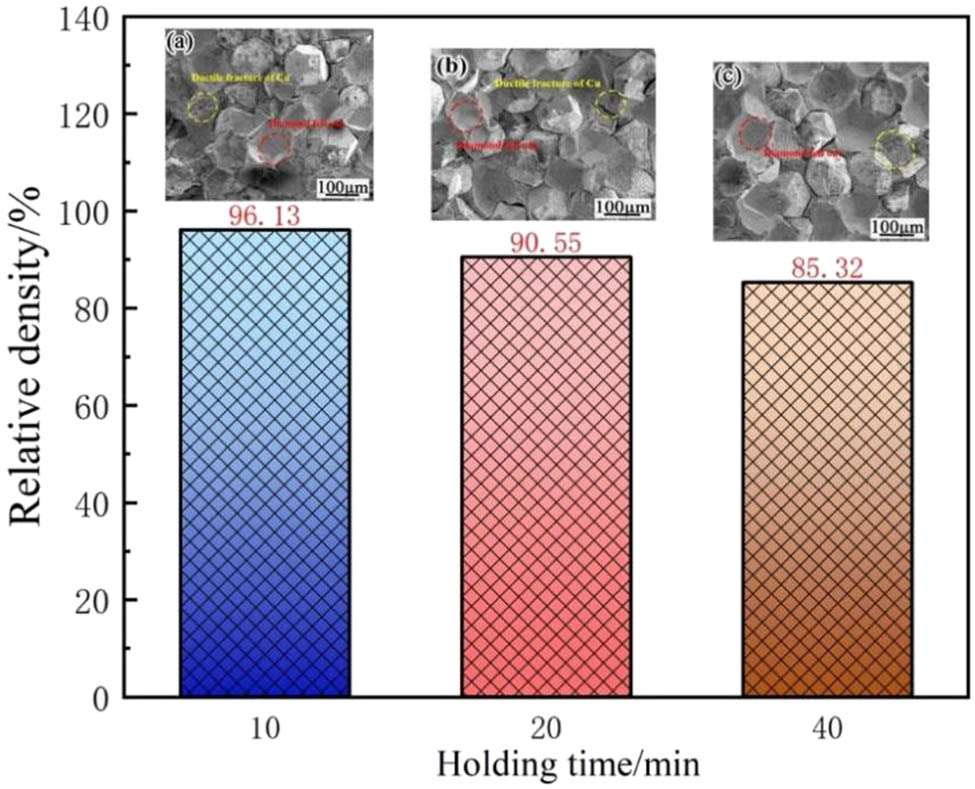

Based on the above research results, the Mo2C-coated diamond particles at 1,000°C deposited for 60 min were selected to fabricate diamond/Cu composites. The composites were fabricated with 50 vol% Mo2C-coated diamonds by SPS at 80 MPa, 900°C for 10, 20, and 40 min, respectively. Figure 10 shows the relative density (RD) of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites. The highest RD of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites is 96.13% at the holding time of 10 min, the two main fracture types of diamond/Cu composites are ductile and diamond falling out from the surface, some diamond faces are bonded with copper compactly where there are fewer cracks inside, while the RD of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites decreases at the holding time of 10 and 20 min, it can be seen that cracks and gaps exist between diamond surfaces and copper. Meanwhile, more voids and gaps appear between copper and Mo2C-coated diamond composites as the sintering time is prolong. Due to the SPS period going up, the spark pulse would produce instantaneous high temperature, which will damage the interlayer between copper matrix and diamond, the same effect as diamond/Cu composites with non-coated diamond. Therefore, the RD of composites is consistent with the morphology, because the lower the RD is, the more voids and gaps will appear in the composites. The decrease in RD can also prove that the bonding between copper and the Mo2C interlayer is weakened with the increase in sintering time, which causes the increase in voids and cracks as seen in Figure 10. The morphologies of the facture show that there is better interfacial bonding in diamond/Cu composites fabricating under 900°C, 80 MPa sintering for 10 min.

RD of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites at different holding time.

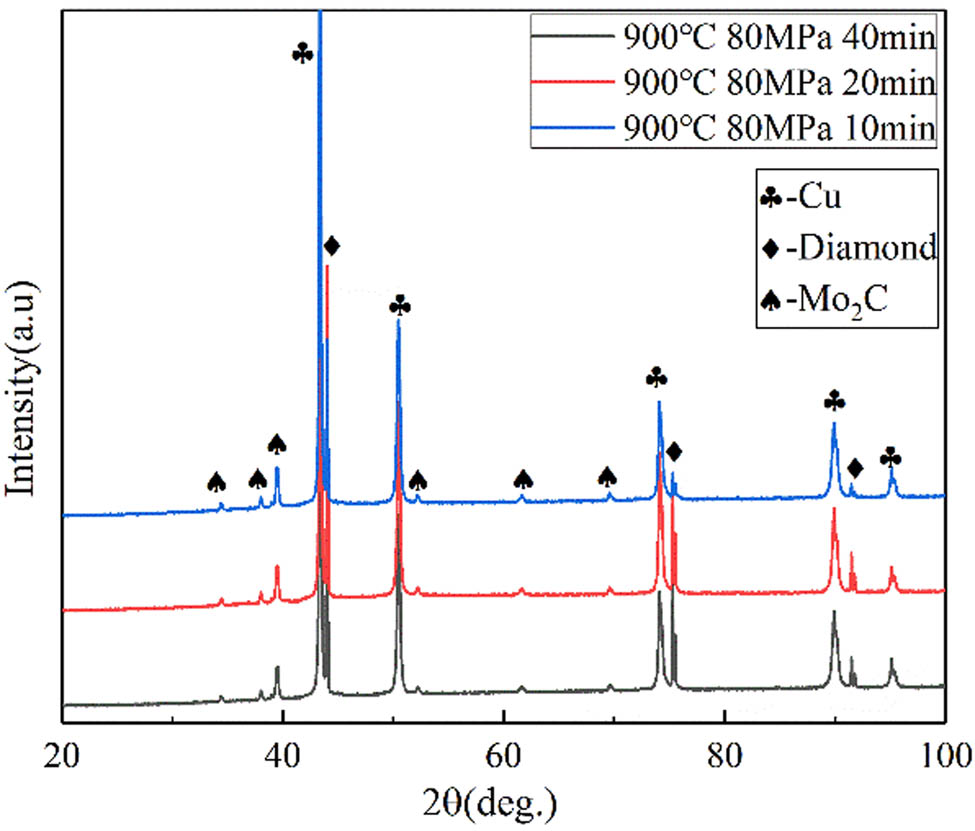

Figure 11 is the XRD pattern of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites at different sintering parameters. The XRD result shows that there is no other phase generated when fabricating the composites, which is in agreement with that in the study by Li et al. [44]. And Cu and Mo2C still exist after sintering. The diamond phase is detected means there would be no graphite phase generated by SPS, which also indicates that 900°C would be a suitable temperature for fabricating diamond/Cu composites.

XRD pattern of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites with different sintering parameters.

3.4 FEA and experiment analysis on TC of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites

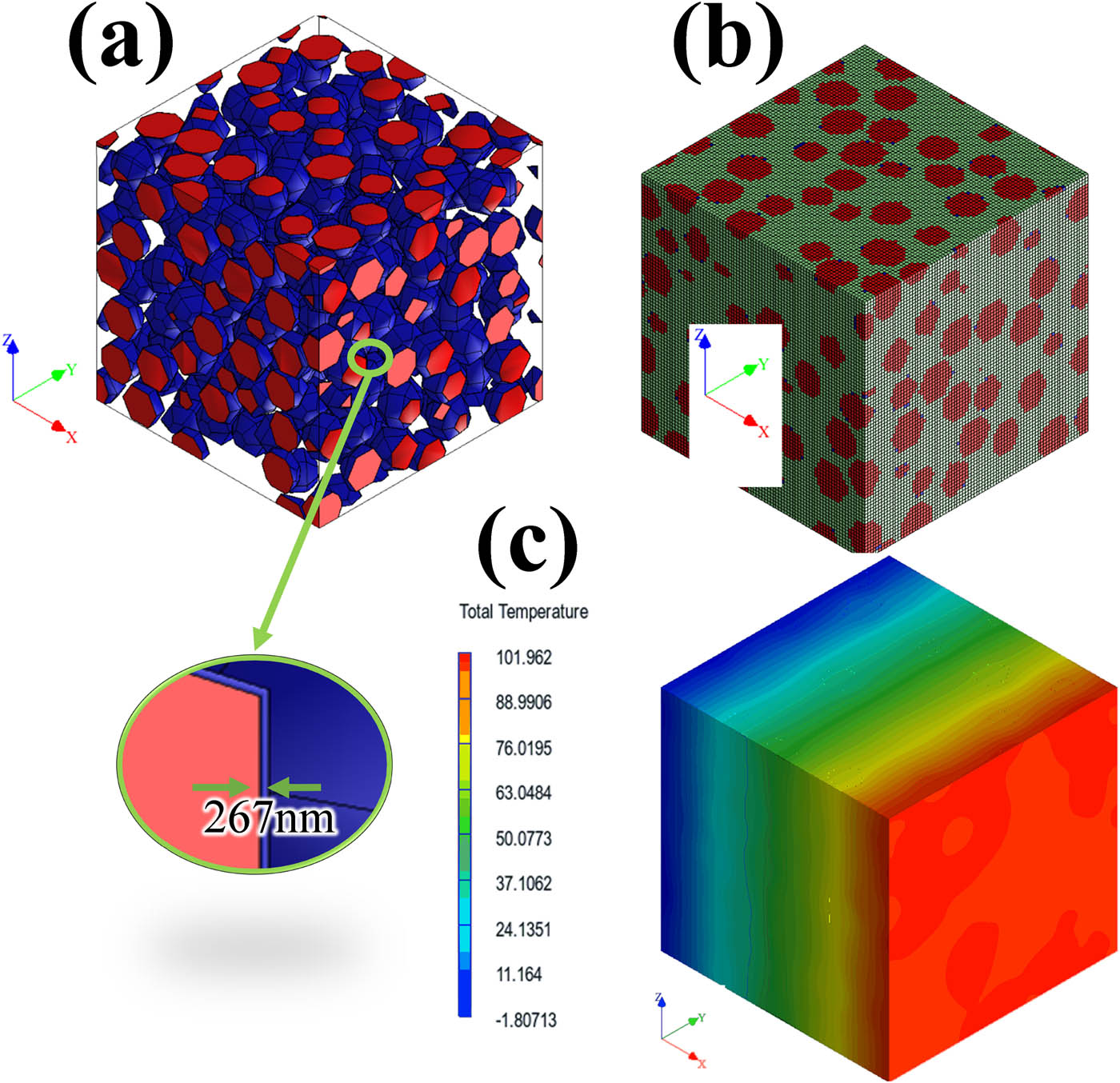

The representative volume element (RVE) model of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites is established by using Digimat and ABAQUS simulation software. Voxel mesh generation for 3D models can be chosen due to its stable mesh quality, high accuracy, low consumption of computing power, and a high degree of customization for the number of meshes. Due to the isotropic nature of diamond/Cu composites, the thermal field can be loaded in a specific direction. The simulation field is set as heat exchange, the right side of its X-axis is set as the heat source contact surface, the peak temperature is 100°C, and the unidirectional heat transfer along the X-axis of RVE is carried out, as shown in Figure 12, and the parameters for FEA of the composites is displayed in Table 2.

Finite element model of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites: (a) 3D model, (b) mesh generation, and (c) temperature field model.

| Materials | Density (g/cm3) | Heat capacity (J/(kg K)) | Debye sound velocity (m/s) | TC (W/(m K)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diamond | 3.52 | 512 | 13,430 | 1,500 |

| Mo2C | 8.89 | 347 | 4,003 | 21 |

| Porosity | 1.205 | 1,002 | — | 0.026 |

| Cu | 8.96 | 386 | 2,801 | 398 |

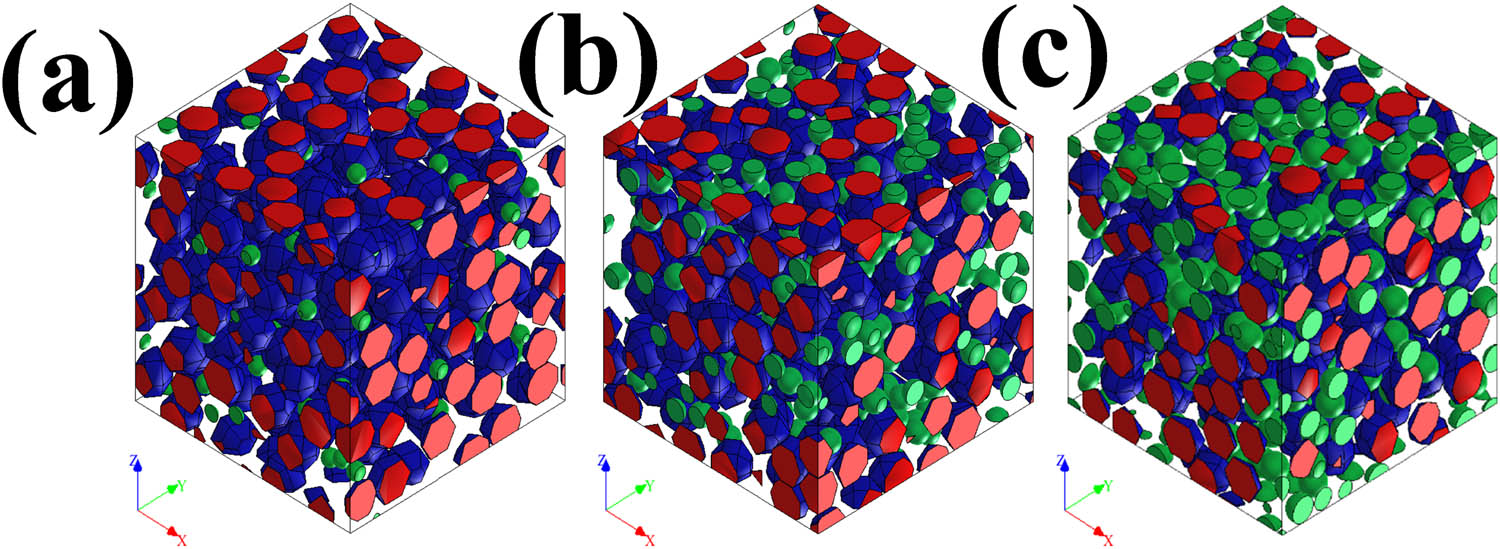

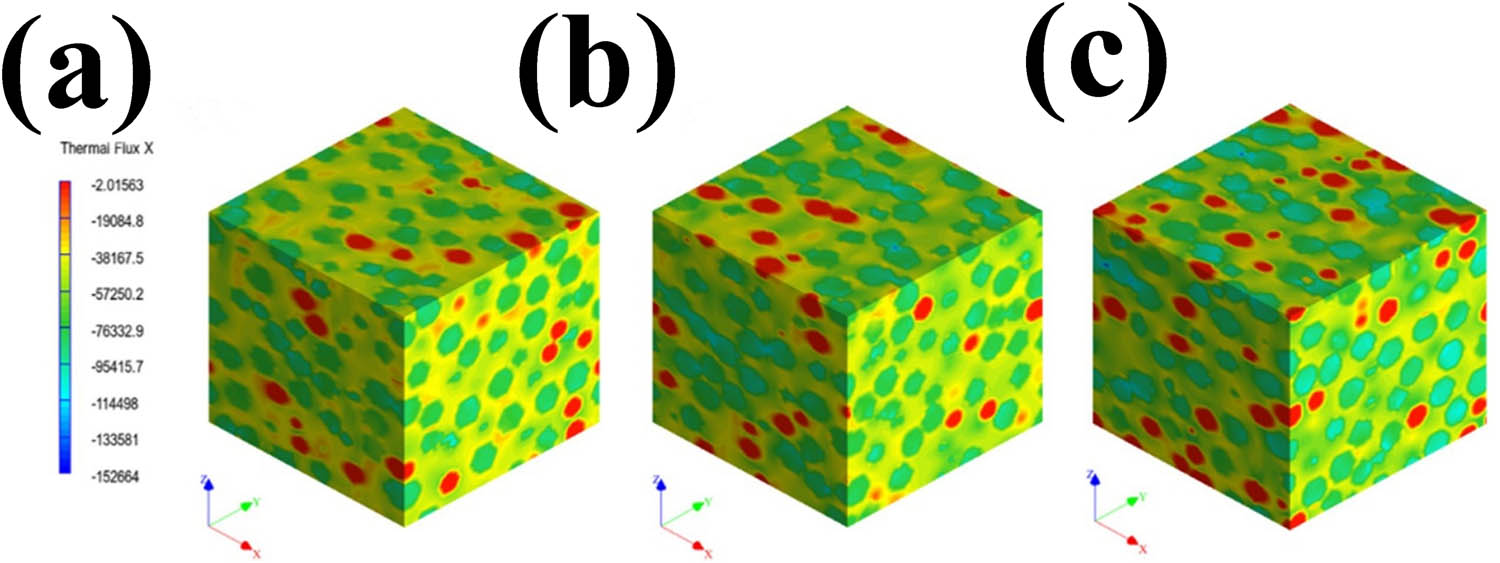

It can be seen from Figure 10 that the RD of the composites under different holding time is 96.13, 90.55, and 85.32%, respectively, in other words, the porosity of the composites is 4.87, 9.45, and 14.68%. Since porosity has a great influenceon the TC of diamond/Cu composites, the effect of porosity on TC is mainly discussed, which is based on the 3D model with the Mo2C coating thickness of 267 nm. The 3D model of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites with different porosities is shown in Figure 13. In the image, the blue portion is Mo2C continuous coating and the green portion is randomly distributed pores.

3D model of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites with different porosities: (a) 4.87%, (b) 9.45%, and (c) 14.68%.

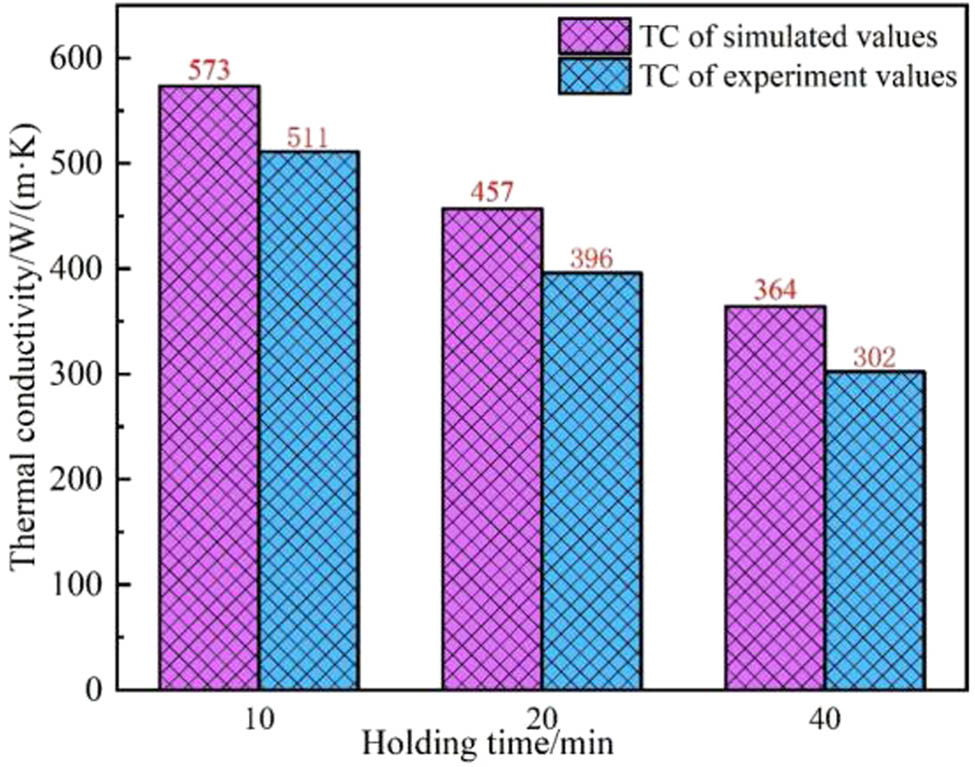

The FEA TC results of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites at different parameters are shown in Figure 14 and Table 3. It is seen that the pores have a completely negative effect on the TC of the composites, and the heat could not be effectively conducted when it is accumulated in the pores. As the porosity increases, the surface heat flux of the composites gradually decreases due to the large scattering range and high degree of air in the pores, where high thermal resistance is formed and the TC is only 0.026 W/(m K). Therefore, the heat flux density at the pores is much lower than that in other parts.

FEA result of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites with different porosities: (a) 4.87%, (b) 9.45%, and (c) 14.68%.

FEA TC results of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites at different parameters

| Sintering temperature (°C) | Loading pressure (MPa) | Holding time (min) | Porosity (%) | Specific direction | TC (W/(m K)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 900 | 80 | 10 | 5 | K11 | 574 |

| K22 | 573 | ||||

| K33 | 574 | ||||

| 20 | 10 | K11 | 457 | ||

| K22 | 458 | ||||

| K33 | 458 | ||||

| 40 | 15 | K11 | 364 | ||

| K22 | 364 | ||||

| K33 | 364 |

The simulated and experimental TC of Mo2C-coated diamond/Cu composites are shown in Figure 15. Compared with the experimental value, the simulation result is closer to the experimental results, since the gap with low heat conduction and the air in the gap is added in the simulation process, so that it can simulate in a more real heat conduction situation. Meanwhile, the simulation results considering pores and coatings can be used as a tool to predict TC, and the TC prediction database based on the simulation results can be established, but there exists a difference in them, as the coating on the diamond surface is uneven actually, while the simulation considers the uniform coating between diamond and Cu.

Comparison of TC obtained by simulation and experiment.

4 Conclusion

Mo2C layer was generated on the diamond surface via vacuum micro-evaporating, which was used as the reinforcement particles to fabricate diamond/Cu composites by SPS. The effect of evaporation parameters on the forming of Mo2C, and the holding time on diamond/Cu composites fabrication is studied. Combined with the experiment and FEA, the holding time on diamond/Cu composites influence on TC of composites is further discussed.

But, in the work, the process parameters of diamond and diamond-copper composite materials are merely experimentally studied by using the principle of single variable. In the future, neural networks and other algorithms can be further used to construct the optimization design of process parameters under multi-factor and multi-coupling. The conclusion of the study is as follows:

As the evaporation of time and temperature increases, the Mo coating on diamonds surface becomes evenly, the optimum time and tenmperature of coatd Mo2C on diamond particles is 1,000°C for 60 min.

Diamond/Cu composites were fabricated by SPS at 900°C, 80 MPa, sintered for 10, 20, and 40 min, respectively, and high density of the composites with Mo2C interlayer can be fabricated by SPS at 900°C, 80 MPa for 10 min. The fractures in the diamond/Cu composites are mainly ductile fractures on copper and diamond falling out from the Mo2C interface. It was found that sintering time would significantly influence the dissipation property of diamond/Cu composites.

The comprehensive parameter for SPS was obtained as 900°C, 80 MPa for 10 min, the RD and TC of the composites obtained is 96.13% and 511 W/(m K). A longer sintering time would damage the Mo2C interlayer and further decrease the bonding between copper matrix and diamond particles, which would lower the RD and TC of composites.

On comparison, the simulation result is closer to the experimental results, since the gap with low heat conduction and the air in the gap is added in the simulation process. Meanwhile, the simulation results considering pores and coatings can be used as a tool to predict TC, and the TC prediction database based on the simulation results can be established, but difference exist in them, as the coating on the diamond surface is uneven actually, while the simulation considers uniform coating between diamond and Cu.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52075250, 52175468), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2020M683376), State Key Laboratory of Advanced Welding and Joining, Harbin Institute of Technology (No. AWJ-22M13), and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20211185).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. CW: provided the data acquisition, interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript, HL: carried out the experiments, wrote the manuscript, and edited the manuscript for Grammer and language errors, WT and WL guided the writing, critical revision of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Dai SG, Li JW, Lu NX. Research progress of diamond/copper composites with high thermal conductivity. Diam Relat Mater. 2020;108:107993.10.1016/j.diamond.2020.107993Search in Google Scholar

[2] Chen MH, Li HZ, Wang CR, Wang N, Li ZY, Tang LN. Progress in heat conduction of diamond/Cu composites with high TC. Rare Met Mater Eng. 2020;49:12.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Yuan MY, Tan ZQ, Fan GL, Xiong DB, Guo Q, Guo CP, et al. Theoretical modelling for interface design and TC prediction in diamond/Cu composites. Diam Relat Mater. 2018;81:38–44.10.1016/j.diamond.2017.11.010Search in Google Scholar

[4] Li YQ, Zhou HY, Wu CJ, Yin Z, Liu C, Huang Y, et al. The interface and fabrication process of diamond/cu composites with nanocoated diamond for heat sink applications. Metals. 2021;11:196.10.3390/met11020196Search in Google Scholar

[5] Wang LH, Li JW, Che ZF, Wang XT, Zhang HL, Wang JG, et al. Combining Cr pre-coating and Cr alloying to improve the thermal conductivity of diamond particles reinforced Cu matrix composites. J Alloy Compd. 2018;749:1098–105.10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.03.241Search in Google Scholar

[6] Sun LL, Zuo X, Guo P, Li XW, Ke PL, Wang AY. Role of deposition temperature on the mechanical and tribological properties of Cu and Cr co-doped diamond-like carbon films. Thin Solid Films. 2019;678:16–25.10.1016/j.tsf.2019.03.034Search in Google Scholar

[7] Bai GZ, Wang LH, Zhang YJ, Wang XT, Wang JG, Kim MJ, et al. Tailoring interface structure and enhancing thermal conductivity of Diamond/Cu composites by alloying boron to the Cu matrix. Mater Charact. 2019;152:265–75.10.1016/j.matchar.2019.04.015Search in Google Scholar

[8] Yang L, Sun L, Bai WW, Li LC. Thermal conductivity of Cu-Ti/diamond composites via spark plasma sintering. Diam Relat Mater. 2019;94:37–42.10.1016/j.diamond.2019.02.014Search in Google Scholar

[9] Chung CY, Lee MT, Tsai MY, Chu CH, Lin SJ. High thermal conductive diamond/Cu–Ti composites fabricated by pressureless sintering technique. Appl Therm Eng. 2014;69:1–2.10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2013.11.065Search in Google Scholar

[10] Bai GZ, Li N, Wang XT, Wang JG, Kim MJ, Zhang HZ. High thermal conductivity of Cu-B/diamond composites prepared by gas pressure infiltration. J Alloy Compd. 2018;735:1648–53.10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.11.273Search in Google Scholar

[11] Bai GZ, Zhang YJ, Dai JJ, Wang LH, Wang XT, Wang JG, et al. Tunable coefficient of thermal expansion of Cu-B/diamond composites prepared by gas pressure infiltration. J Alloy Compd. 2019;794:473–81.10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.04.252Search in Google Scholar

[12] Duan DZ, Xiao B, Wang B, Han P, Li WJ, Xia SW. Microstructure and mechanical properties of pre-brazed diamond abrasive grains using Cu-Sn-Ti alloy. Int J Refract Met Hard Mater. 2015;48:427–32.10.1016/j.ijrmhm.2014.10.015Search in Google Scholar

[13] Chu K, Jia CC, Guo H, Li WS. On the thermal conductivity of Cu-Zr/diamond composites. Mater Des. 2013;45:36–42.10.1016/j.matdes.2012.09.006Search in Google Scholar

[14] Wu M, Cao CC, Din RU, He XB, Qu XH. Brazing diamond/Cu composite to alumina using reactive Ag-Cu-Ti alloy. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China. 2013;23:1701–8.10.1016/S1003-6326(13)62651-5Search in Google Scholar

[15] Xia Y, Song YQ, Lin CG, Cui S, Fang ZZ. Effect of carbide formers on microstructure and thermal conductivity of diamond-Cu composites for heat sink materials. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China. 2009;19:1161–6.10.1016/S1003-6326(08)60422-7Search in Google Scholar

[16] Zhang XY, Xu M, Cao SZ, Chen WB, Yang WY, Yang QY. Enhanced thermal conductivity of diamond/copper composite fabricated through doping with rare-earth oxide Sc2O3. Diam Relat Mate. 2020;104:107755.10.1016/j.diamond.2020.107755Search in Google Scholar

[17] Zhang C, Wang RC, Cai ZY, Peng CQ, Feng L, Zhang L. Effects of dual-layer coatings on microstructure and thermal conductivity of diamond/Cu composites prepared by vacuum hot pressing. Surf Coat Technol. 2015;277:299–307.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2015.07.059Search in Google Scholar

[18] Wang XL, He XB, Xu ZY, Qu XH. Preparation of W-plated diamond and improvement of thermal conductivity of Diamond-WC-Cu composite. Metals. 2021;11:437.10.3390/met11030437Search in Google Scholar

[19] Ukhina A, Bokhonov B, Samoshkin D, Stankus D, Dudina D, Galashov E, et al. Morphological features of W- and Ni-containing coatings on diamond crystals and properties of diamond-copper composites obtained by spark plasma sintering. Mater Today: Proc. 2017;4:11396–401.10.1016/j.matpr.2017.09.016Search in Google Scholar

[20] Okada T, Fukuoka K, Arata Y, Yonezawa S, Kiyokawa H, Takashima M. Tungsten carbide coating on diamond particles in molten mixture of Na2CO3 and NaCl. Diam Relat Mater. 2015;52:11–7.10.1016/j.diamond.2014.11.008Search in Google Scholar

[21] Chu K, Liu ZF, Jia CC, Chen H, Liang XB, Gao WJ, et al. Thermal conductivity of SPS consolidated Diamond/Cu composites with Cr-coated diamond particles. J Alloy Compd. 2010;490:453–8.10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.10.040Search in Google Scholar

[22] Zuo Q, Wang W, Gu MS, Fang HJ, Ma L, Wang P, et al. Thermal conductivity of the diamond-Cu composites with chromium addition. Adv Mater Res. 2011;311–313:287–92.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.311-313.287Search in Google Scholar

[23] Niazi AR, Li YS, Wang KC, Liu JX, Hu ZY, Usman Z. Parameters optimization of electroless deposition of Cu on Cr-coated diamond. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China. 2014;24:136–45.10.1016/S1003-6326(14)63039-9Search in Google Scholar

[24] Hell J, Chirtoc M, Eisenmenger-Sittner C, Hutter H, Kornfeind N, Kijamnajsuk P, et al. Characterisation of sputter deposited niobium and boron interlayer in the copper–diamond system. SurfCoat Technol. 2012;208:24–31.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2012.07.068Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Yang GR, Song WM, Wang N, Li YM, Ma Y. Fabrication and formation mechanism of vacuum cladding Ni/WC/GO composite fusion coatings. Mater Today Com. 2020;25:101342.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101342Search in Google Scholar

[26] Chang G, Sun FY, Wang LH, Che ZX, Wang XT, Wang JG, et al. Regulated interfacial thermal conductance between Cu and diamond by a TiC interlayer for thermal management applications. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2019;11:26507–17.10.1021/acsami.9b08106Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] WangCR LiHZ, Chen MH, Li ZY, Tang LN. Microstructure and thermo-physical properties of Cu-Ti double-layer coated diamond/Cu composites fabricated by spark plasma sintering. Diamond Related Mater. 2020;109:108041.10.1016/j.diamond.2020.108041Search in Google Scholar

[28] Chang G, Sun FY, Duan JL, Che ZF, Wang XT, Wang JG, et al. Effect of Ti interlayer on interfacial thermal conductance between Cu and diamond. Acta Mater. 2018;160:235–46.10.1016/j.actamat.2018.09.004Search in Google Scholar

[29] Zhang C, Wang CR, Peng CQ, Tang YG, Cai ZY. Influence of titanium coating on the microstructure and thermal behavior of Dia./Cu composites. Diam Relat Mater. 2019;97:107449.10.1016/j.diamond.2019.107449Search in Google Scholar

[30] Chang G, Sun FY, Duan JL, Wang LH, Zhang Y, Wang XT, et al. Mo-interlayer-mediated thermal conductance at Diamond/Cu interface measured by time-domain thermoreflectance. Compos Part A: Appl Sci Manufact. 2020;135:105921.10.1016/j.compositesa.2020.105921Search in Google Scholar

[31] Liu RX, Luo GQ, Li Y, Zhang J, Shen Q, Zhang LM. Microstructure and thermal properties of diamond/copper composites with Mo2C in-situ nano-coating. Surf Coat Technol. 2019;360:376–81.10.1016/j.surfcoat.2018.12.116Search in Google Scholar

[32] Zha XH, Yin JS, Zhou YH, Huang Q, Luo K, Lang JJ, et al. Intrinsic structural, electrical, thermal, and mechanical properties of the promising conductor Mo2C MXene. J Phys Chem C. 2016;120:15082–8.10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b04192Search in Google Scholar

[33] Long F, Wei QP, Yu ZM, Luo JQ, Zhang XW, Long HY, et al. Effects of temperature and Mo2C layer on stress and structural properties in CVD diamond film grown on Mo foil. J Alloys Compd. 2013;579:638–45.10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.06.146Search in Google Scholar

[34] Chang R, Zang JB, Wang YH, Yu YQ, Lu J, Xu XP. Preparation of the gradient Mo layers on diamond grits by spark plasma sintering and their effect on Fe-based matrix diamond composites. J Alloy Compd. 2017;695:70–5.10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.10.172Search in Google Scholar

[35] Ma SD, Zhao NQ, Shi CS, Liu EZ, He CN, He F, et al. Mo2C coating on diamond: Different effects on thermal conductivity of diamond/Al and diamond/Cu composites. Appl Surf Sci. 2017;402:372–83.10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.01.078Search in Google Scholar

[36] Wu YP, Tang ZY, Wang Y, Cheng P, Wang H, Ding GF. High thermal conductive Cu-diamond composites synthesized by electrodeposition and the critical effects of additives on void-free composites. Ceram Int. 2019;45:19658–68.10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.06.215Search in Google Scholar

[37] Cho HJ, Yan D, Tam J, Erb U. Effects of diamond particle size on the formation of copper matrix and the thermal transport properties in electrodeposited copper-diamond composite materials. J Alloy Compd. 2019;791:1128–37.10.1016/j.jallcom.2019.03.347Search in Google Scholar

[38] Wu YP, Lai LY, Wang Y, Wang H, Ding GF. Optimization of external and internal conditions for high thermal conductive Cu-diamond composites produced by electrocoating. Diamond Related Mater. 2019;98:107478.10.1016/j.diamond.2019.107478Search in Google Scholar

[39] Wu YP, Sun YN, Luo JB, Cheng P, Wang Y, Wang H, et al. Microstructure of Cu-diamond composites with near-perfect interfaces prepared via electrocoating and its thermal properties. Mater Charact. 2019;150:199–206.10.1016/j.matchar.2019.02.018Search in Google Scholar

[40] Tao JM, Zhu XK, Tian WW, Yang P, Yang H. Properties and microstructure of Diamond/Cu composites prepared by spark plasma sintering method. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China. 2014;24:3210–4.10.1016/S1003-6326(14)63462-2Search in Google Scholar

[41] Cao D. Investigation into surface-coated continuous flax fiber-reinforced natural sandwich composites via vacuum-assisted material extrusion. Prog Addit Manuf. 2023;368:845101.10.1007/s40964-023-00508-6Search in Google Scholar

[42] Cao D, Bouzolin D, Lu H, Griffith DT. Bending and shear improvements in 3D-printed core sandwich composites through modification of resin uptake in the skin/core interphase region. Compos Part B. 2023;264:110912.10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110912Search in Google Scholar

[43] Cao D. Fusion joining of thermoplastic composites with a carbon fabric heating element modified by multiwalled carbon nanotube sheets. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2023;128:4443–53.10.1007/s00170-023-12202-6Search in Google Scholar

[44] Li HZ, Wang CR, Ding W, Wu LM, Wang J, Tian W, et al. Microstructure evolution of diamond with molybdenum coating and thermal conductivity of diamond/copper composites fabricated by spark plasma sintering. J Mater Sci: Mater Electron. 2022;33:15369–84.10.1007/s10854-022-08441-0Search in Google Scholar

[45] Williams WS. The thermal conductivity of metallic ceramics. JOM. 1998;50:62–6.10.1007/s11837-998-0131-ySearch in Google Scholar

[46] Swartz ET, Pohl RO. Thermal boundary resistance. Rev Mod Phys. 1989;61:605–20.10.1103/RevModPhys.61.605Search in Google Scholar

[47] Stoner RJ, Maris HJ. Kapitza conductance and heat flow between solids at temperatures from 50 to 300 K. Phys Rev B. 1993;48(22):16373.10.1103/PhysRevB.48.16373Search in Google Scholar

© 2024 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective

Articles in the same Issue

- Regular Articles

- Research on damage evolution mechanisms under compressive and tensile tests of plain weave SiCf/SiC composites using in situ X-ray CT

- Structural optimization of trays in bolt support systems

- Continuum percolation of the realistic nonuniform ITZs in 3D polyphase concrete systems involving the aggregate shape and size differentiation

- Multiscale water diffusivity prediction of plain woven composites considering void defects

- The application of epoxy resin polymers by laser induction technologies

- Analysis of water absorption on the efficiency of bonded composite repair of aluminum alloy panels

- Experimental research on bonding mechanical performance of the interface between cementitious layers

- A study on the effect of microspheres on the freeze–thaw resistance of EPS concrete

- Influence of Ti2SnC content on arc erosion resistance in Ag–Ti2SnC composites

- Cement-based composites with ZIF-8@TiO2-coated activated carbon fiber for efficient removal of formaldehyde

- Microstructure and chloride transport of aeolian sand concrete under long-term natural immersion

- Simulation study on basic road performance and modification mechanism of red mud modified asphalt mixture

- Extraction and characterization of nano-silica particles to enhance mechanical properties of general-purpose unsaturated polyester resin

- Roles of corn starch and gellan gum in changing of unconfined compressive strength of Shanghai alluvial clay

- A review on innovative approaches to expansive soil stabilization: Focussing on EPS beads, sand, and jute

- Experimental investigation of the performances of thick CFRP, GFRP, and KFRP composite plates under ballistic impact

- Preparation and characterization of titanium gypsum artificial aggregate

- Characteristics of bulletproof plate made from silkworm cocoon waste: Hybrid silkworm cocoon waste-reinforced epoxy/UHMWPE composite

- Experimental research on influence of curing environment on mechanical properties of coal gangue cementation

- Multi-objective optimization of machining variables for wire-EDM of LM6/fly ash composite materials using grey relational analysis

- Synthesis and characterization of Ag@Ni co-axial nanocables and their fluorescent and catalytic properties

- Beneficial effect of 4% Ta addition on the corrosion mitigation of Ti–12% Zr alloy after different immersion times in 3.5% NaCl solutions

- Study on electrical conductive mechanism of mayenite derivative C12A7:C

- Fast prediction of concrete equivalent modulus based on the random aggregate model and image quadtree SBFEM

- Research on uniaxial compression performance and constitutive relationship of RBP-UHPC after high temperature

- Experimental analysis of frost resistance and failure models in engineered cementitious composites with the integration of Yellow River sand

- Influence of tin additions on the corrosion passivation of TiZrTa alloy in sodium chloride solutions

- Microstructure and finite element analysis of Mo2C-diamond/Cu composites by spark plasma sintering

- Low-velocity impact response optimization of the foam-cored sandwich panels with CFRP skins for electric aircraft fuselage skin application

- Research on the carbonation resistance and improvement technology of fully recycled aggregate concrete

- Study on the basic properties of iron tailings powder-desulfurization ash mine filling cementitious material

- Preparation and mechanical properties of the 2.5D carbon glass hybrid woven composite materials

- Improvement on interfacial properties of CuW and CuCr bimetallic materials with high-entropy alloy interlayers via infiltration method

- Investigation properties of ultra-high performance concrete incorporating pond ash

- Effects of binder paste-to-aggregate ratio and polypropylene fiber content on the performance of high-flowability steel fiber-reinforced concrete for slab/deck overlays

- Interfacial bonding characteristics of multi-walled carbon nanotube/ultralight foamed concrete

- Classification of damping properties of fabric-reinforced flat beam-like specimens by a degree of ondulation implying a mesomechanic kinematic

- Influence of mica paper surface modification on the water resistance of mica paper/organic silicone resin composites

- Impact of cooling methods on the corrosion behavior of AA6063 aluminum alloy in a chloride solution

- Wear mechanism analysis of internal chip removal drill for CFRP drilling

- Investigation on acoustic properties of metal hollow sphere A356 aluminum matrix composites

- Uniaxial compression stress–strain relationship of fully aeolian sand concrete at low temperatures

- Experimental study on the influence of aggregate morphology on concrete interfacial properties

- Intelligent sportswear design: Innovative applications based on conjugated nanomaterials

- Research on the equivalent stretching mechanical properties of Nomex honeycomb core considering the effect of resin coating

- Numerical analysis and experimental research on the vibration performance of concrete vibration table in PC components

- Assessment of mechanical and biological properties of Ti–31Nb–7.7Zr alloy for spinal surgery implant

- Theoretical research on load distribution of composite pre-tightened teeth connections embedded with soft layers

- Coupling design features of material surface treatment for ceramic products based on ResNet

- Optimizing superelastic shape-memory alloy fibers for enhancing the pullout performance in engineered cementitious composites

- Multi-scale finite element simulation of needle-punched quartz fiber reinforced composites

- Thermo-mechanical coupling behavior of needle-punched carbon/carbon composites

- Influence of composite material laying parameters on the load-carrying capacity of type IV hydrogen storage vessel

- Review Articles

- Effect of carbon nanotubes on mechanical properties of aluminum matrix composites: A review

- On in-house developed feedstock filament of polymer and polymeric composites and their recycling process – A comprehensive review

- Research progress on freeze–thaw constitutive model of concrete based on damage mechanics

- A bibliometric and content analysis of research trends in paver blocks: Mapping the scientific landscape

- Bibliometric analysis of stone column research trends: A Web of Science perspective