Abstract

The involvement of global actors and local stakeholders plays a strategic role in the sustainability of natural silk agribusiness. However, there remains a significant gap in understanding how the presence of global actors shapes, influences, and directs the design and achievements of integration in the Soppeng and Wajo Regencies. This study aims to analyze the role of global actors in the sustainability of upstream and downstream integration involving actors from two neighboring regions. This study was conducted using a case study method on actor interactions in the sustainability of natural silk agribusiness integration. Data were collected through interviews, observations, and documentation from 22 participants. The results show that the sustainability of upstream–downstream integration of the natural silk agribusiness in Soppeng and Wajo Regencies is influenced by the interaction between local and global actors. The dominance of global actors as providers of production inputs and export market connectors has shifted the role of local actors and weakened the natural silk supply chain structure. This is reflected in the shifting roles of traditional spinners and the weaving industry in downstream activities that survive on imported yarn. Therefore, strengthening local institutions and production independence are key strategies for realizing the sustainability of an inclusive and competitive natural silk agribusiness.

1 Introduction

Natural silk is a rural agribusiness activity that provides an alternative source of family income, has a low environmental impact, and is economically valuable, thereby contributing to sustainable development [1], [2], [3]. Silk is used as a raw material in textiles and various other industries [4]. The largest producers of natural silk are China and India, whereas smaller producers include Uzbekistan, Thailand, and Brazil, with a global contribution of 98.3 % [5], 6]. Silk production is currently declining in several parts of the world, including Indonesia [7]. Indonesia is not only a silk-producing country but also a silk thread importer, and Indonesia’s silk production tends to decline due to silkworm diseases and the limited quality of silkworm seeds [8]. However, the demand for silk thread and fabric has shown a progressive increase each year, indicating a disparity between the upstream and downstream sectors in Indonesia’s natural silk industry [9].

South Sulawesi Province is a natural silk producer in Indonesia, accounting for more than 80 % of the national silk thread production [8], 10]. The institutional capacity of sericulture businesses in Indonesia is generally still small-scale and household-based. In South Sulawesi, for example, institutions are formed based on the socio-cultural attachment of the community to the use of silk cloth [11]. In Uzbekistan, the government plays a central role through the establishment of the “Uzbekipaksanoat Association,” a national institution that coordinates the entire silk value chain and supports the export and investment activities of sericulture and silk production companies [12]. Meanwhile, Thailand has implemented a community-based institutional model through the government’s One Tambon (Village) One Product (OTOP) program, which has strengthened relationships between communities. Silk-producing communities are gradually being encouraged to work together as clusters [13]. Reference [7] states that the existence of natural silk cultivation in South Sulawesi Province has been preserved from generation to generation thanks to government support in establishing institutions such as silkworm farming groups. The actors along the silk production chain, most of whom still rely on natural silk agribusiness for their livelihoods, are spread across Soppeng Regency [14], 15] and Wajo Regency, which is known as the “City of Silk” [16]. Natural silk agribusiness involves a series of interrelated activities, where the success of each stage determines the next [17], and requires attention to environmental conditions [18], [19], [20], starting from mulberry cultivation, silkworm cultivation, post-harvest handling, and processing to marketing, which contributes to the regional economy and income for farming families [21], 22].

Natural silk production in Soppeng and Wajo districts is not yet optimal, so it is unable to meet market demand, and the quality of the silk produced remains low [23]. Problems in the mulberry cultivation subsystem include a decline in the number of mulberry farmers owing to a lack of farmer regeneration and a decline in the quality of silkworm seeds. According to [24], farmer regeneration in agribusiness sustainability is rooted in innovation through knowledge exchange among generations of farmers. Low silkworm cocoon production is influenced by many factors, including the environment, availability of silkworm feed, quality of silkworm seeds, labor, and cultivation facilities and infrastructure [7]. Many factors that affect the success of cocoon production have an impact on the sustainability of farmers’ incomes. Therefore, quality improvements are required to meet farmers’ expectations and satisfaction [25]. The downstream subsystem includes spinning and weaving, and the problem is a decline in the quantity and quality of cocoon production, which has led to a decline in the spinning industry. Many small-scale spinners operate on a very limited scale owing to an insufficient supply of raw materials [26].

The presence of PT. The mulberry silk industry has created new dynamics in the upstream sector of natural silk products in South Sulawesi. The company exported its first batch of silkworm cocoons to China in 2023, amounting to 1.9 tons, distributed mulberry seeds and silkworm seeds for free, and provided price certainty and guaranteed purchase of cocoons after production. This has revived farmers’ enthusiasm for the silk business in Soppeng. The average cocoon production from silkworms distributed by partner companies is 37–40 kg/box, and they purchase the cocoons at Rp. 60,000/kg, which then became an export product. The supply of raw materials for downstream production activities, namely silk fabric manufacturing in Wajo, is constrained by the availability of raw materials in the form of yarns. This has prompted businesses in Wajo to use imported yarn from abroad to continue production [26]. The relationship between two different administrative regions, Soppeng Regency and Wajo Regency, has become increasingly complex concerning the role of silkworm and silk thread suppliers at the global level, thereby affecting the sustainability of upstream and downstream integration. The integration of upstream activities (silkworm cultivation and thread production) and downstream activities (weaving and marketing of silk fabrics) from a regional perspective, considering cooperation between regions and the global economy, as well as the role of global actors in interacting with local actors from neighboring regions, impacts the sustainability of the silk agribusiness.

Previous research on the role of global actors in the development of silk has explored several aspects of this topic. For example [27], found that the silk industry flourished within a complex and interconnected supply chain structure because of Bangladesh’s agriculture-based economy. The availability, cost, and accessibility of silk-based products are influenced by complex networks of actors, detailed procedures, and dynamic tactics. Study [28] found that stakeholders in the upstream and downstream value chains of the silk industry essentially influence business formation while also being influenced by the results of product and process innovation. The findings [29] show that the actors who have significant influence and interest in the sustainability of natural silk in Soppeng Regency mainly come from the provincial and regency government sectors. The results of the study [26] found that good adaptability in the era of globalization encourages the sustainability of the silk weaving business in the Wajo Regency. However, there remains a knowledge gap regarding how the presence of global actors affects the sustainability of upstream and downstream integration in the silk agribusiness. This study aims to fill this gap by providing detailed information on the role of global actors in promoting the sustainability of upstream–downstream integration and the interrelationships between key actors involved in the natural silk activity chain in South Sulawesi Province.

2 Literature review

2.1 Interactions of global actors in the supply chain

Actors are institutions, groups, or individuals that play a central role in the system [30]. Actors play an important role in the development of a system through their ability to organize resources and directly influence the outcomes of the system [31]. Each actor has characteristics that indicate their power to influence the policy process [29]. A role can be understood as a series of identifiable actions and attitudes adopted by an actor in response to recurring situations [32]. Actors require resources to maintain their existence and protect their interests, which form a communication network between them. The approach to interaction between actors begins with the social environment in which the actor relates to other actors [33]. Collaboration and synergy between stakeholders through their respective roles and support can contribute to program sustainability [34]. The development of new knowledge configurations through cross-stakeholder collaboration is crucial to addressing today’s sustainability challenges [35]. Each form of knowledge is composed of a number of more specific and in-depth sub-knowledge areas [36]. In this context, knowledge management plays a strategic role in strengthening innovation capacity among farmers [37]. It is also necessary to adjust the framework in the agricultural sector to suit its specific characteristics and needs, with the support of strategic planning, effective cost management, and comprehensive stakeholder involvement to strengthen capacity and increase acceptance [38].

The supply chain encompasses all activities related to meeting consumer needs, including the flow of goods from raw materials to final products, integrated with information and financial flows [39]. Mapping actors in the supply chain is necessary to identify the relative contributions of each actor in the interconnected system. This analysis helps to understand the dynamics of each actor’s role and support for the success of sustainable development programs [40]. Collaboration and cooperation among actors in the supply chain have been shown to have a positive impact on the continuity of programs in the future [41]. This collaboration can encourage economic growth, improve product quality, and ensure the equitable distribution of benefits to farmers [42]. Previous research also reinforces that idea that the collaborative involvement of all parties strengthens the ongoing empowerment process [35]. The development of a circular supply chain requires transformative changes that involve cross-collaboration between stakeholders, both internal and external to the organization [43]. Through close collaboration with supply chain stakeholders, companies can drive economic growth while preserving the environment and community welfare [44]. According to the study [45], improving the value chain can promote sustainable development. According to [46], studies on the sustainability of the New Silk Road are still dominated by economic perspectives, while social, ecological, and local sustainability aspects receive less attention. The involvement of actors in research is needed to ensure that project implementation is inclusive and environmentally friendly. Thus, the application of Actor Network Theory (ANT) principles can play a role in strengthening communication between actors, strengthening collaboration between supply chain nodes, and encouraging more efficient and coordinated management practices. ANT is a paradigmatic and methodological framework in sociology that seeks to understand and explain the complex and dynamic interactions between human and non-human actors in various sociotechnical systems [47], [48], [49], [50]. ANT is gaining attention in supply chain management studies because it offers a new perspective that challenges traditional approaches through three main principles: heterogeneity emphasizes the diversity of actors in a network, relationality highlights that meaning arises from relationships between actors, and finally, performativity shows that reality is formed through actions and interactions that occur in each episode of activity.

2.2 Upstream–downstream integration in the silk agribusiness

Natural silk is an activity developed in rural areas as an alternative source of income for the community [1], in line with decision-making efforts in planting alternative commodities aimed at increasing the income of agricultural actors and maintaining the sustainability of agricultural productivity at the local level [51]. Silk is a strategic commodity. Silk plays an important role as a raw material for the national textile industry and is a source of livelihood for communities from upstream to downstream industries [14]. The development of the silk agribusiness is necessary to meet the needs of the national textile industry, which has thus far been fulfilled by imports. Silk is currently considered the world’s leading textile material because of its high appeal, luster, and ability to bind chemical dyes. Despite facing fierce competition from synthetic fibers, silk has maintained its superiority in the production of luxury clothing and high-quality specialty items [52]. As it develops in the international market, sustainable silk cultivation practices increasingly emphasize the use of natural and environmentally friendly technologies in the production process and its application [3]. The application of circular economy principles, such as innovative and durable product design, reduced chemical use, silk fabric reuse, and recycling promotion, are key to optimizing resources and minimizing waste [39]. Their implementation requires social innovation to change social practices (attitudes, behaviors, and collaborative networks) and is always associated with the involvement of civil society actors [53]. This is even believed to bring about improvements that have the potential to change the direction towards sustainability [54].

Silk agribusiness consists of a series of interrelated upstream and downstream subsystems. Activities in the upstream subsystem include mulberry cultivation (Morus sp.), silkworm rearing (Bombyx mori L), cocoon processing, and silk thread harvesting, each of which can be carried out with consideration for the silkworm environment [18], [19], [20]. Downstream subsystem activities consist of spinning cocoons into silk threads, weaving them into silk fabric, and marketing the product. Natural silk activities, from mulberry cultivation to product marketing, involve farmers, spinners, weavers, weaving entrepreneurs, fabric and sarong traders, silkworm egg importers, and government stakeholders [14]. The integration of upstream and downstream agribusiness is important for understanding a series of systems. In a series of systems, all components must function for the system to operate smoothly [55]. The coordination, integration, and management of business processes between actors in the supply chain are necessary to balance the distribution of profits and risks between the upstream and downstream sectors [39]. Supply chain integration involves harmonious coordination and collaboration among partners in the supply chain to optimize efficiency, reduce operational costs, and improve overall performance [56], 57].

3 Methods

3.1 Research location

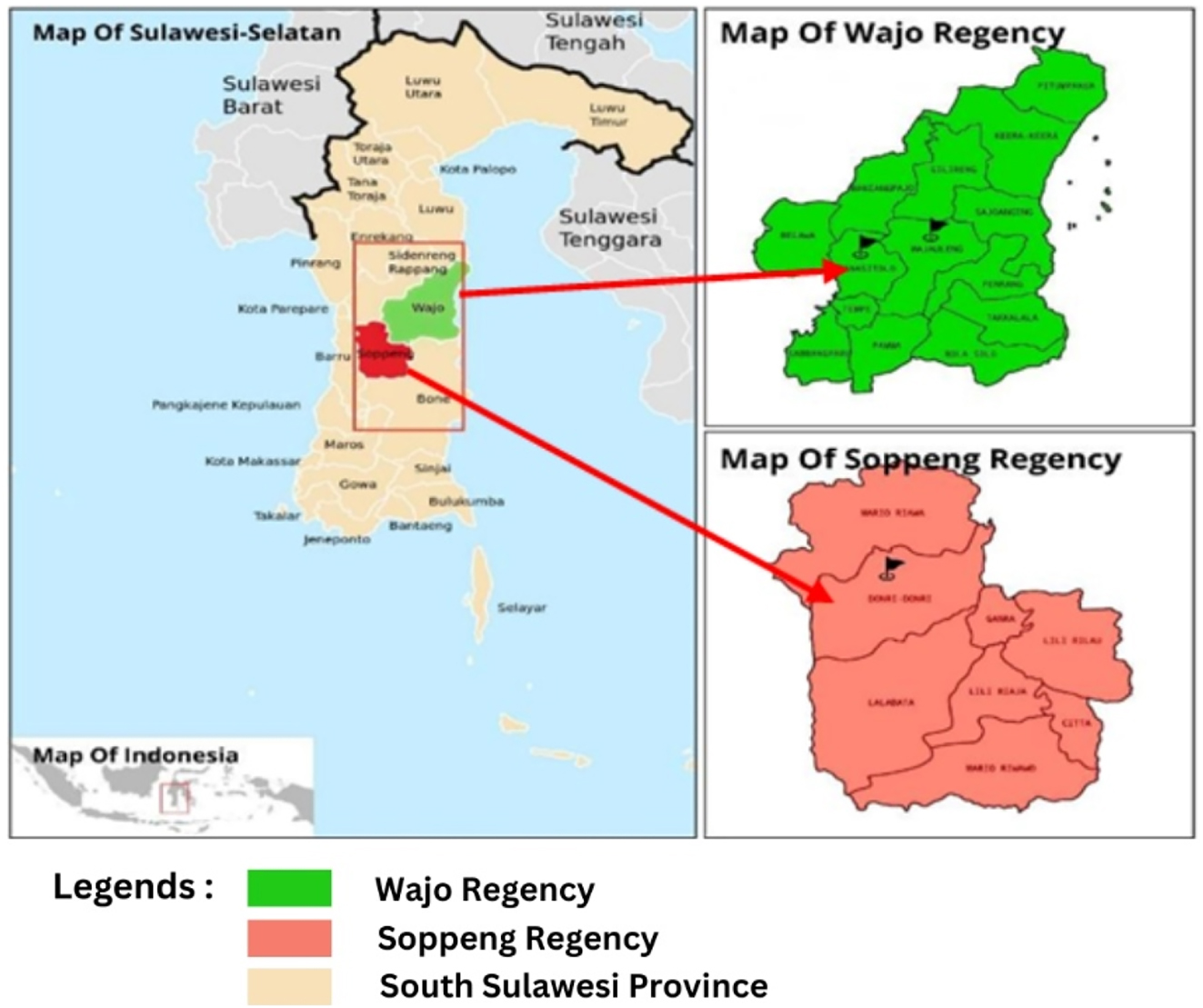

This study was conducted in the Soppeng and Wajo Regencies of South Sulawesi Province, as shown in Figure 1. These locations were selected purposively, considering that the area is a major region for natural silk development in the province.

Map of the research location in Soppeng and Wajo Regencies, South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. Source: Modified from Wikimedia, accessed July 5, 2025.

3.2 Research design

This study used a qualitative approach and a case study method. The case study method is a research strategy in which the researcher carefully investigates the events, activities, processes, and programs of a group or an individual. Case studies are limited by space and time, and complete information was collected using various data collection procedures based on a predetermined time frame [58]. The case units in this study are upstream–downstream integration in the silk agribusiness in Soppeng and Wajo Regencies, where interactions between local and global actors take place.

3.3 Data collection

Informants were selected using purposive and snowball sampling techniques, which involved deliberately selecting informants rather than randomly [59]. According to [60], purposive sampling is one of the most common strategies for determining informants in qualitative research, which involves determining the group of participants who will become informants based on criteria relevant to the research problem. To provide adequate data, informants were selected based on the criteria of having at least five years of experience as either upstream or downstream actors, being willing to be interviewed, and providing information openly. These criteria were determined to obtain representative and in-depth data on the dynamics of the silk agribusiness system before and after the arrival of global actors. According to [61], snowball sampling is a data source sampling technique that starts with a small number of sources and gradually expands the number of sources. Informants were selected based on their knowledge and involvement in the natural silk agribusiness system, whereby initial informants recommended other relevant informants who were directly involved in the natural silk value chain, which was then expanded through referrals from previous informants. This approach was used by researchers to reach key actors at various upstream and downstream levels and to follow the entire production flow through the expansion of the informant network until no new meaningful information was found.

A total of 22 informants consisting of 10 silk agribusiness actors upstream, 10 silk agribusiness actors downstream, and 2 people from government agencies were interviewed. This number was determined based on the data saturation achieved through repeated analysis and cross-confirmation between sources during the field research. Data for this study were obtained through in-depth interviews, observations, and documentation. The information collected was then triangulated to check for consistency and validity between sources, minimize potential subject bias, and obtain a more complete understanding. This triangulation process was used to determine the point of data saturation. According to [62], data saturation is achieved when no new data/codes emerge in the last three interviews, and information from three new informants no longer produces findings that are substantially different from the previous data, indicating the stability of the main categories and themes of the study.

The interview began with an introduction and asking the informant’s willingness to be interviewed. The interviews lasted between 30 and 90 min, and all information was recorded and transcribed. In addition, observations were conducted directly at the location to observe the activities of agribusiness actors firsthand. The time horizon of this study used a cross-sectional study approach, which was conducted once on each subject [63]. The data collection process was conducted through interviews over five months, from February to June 2025.

3.4 Informed consent

All informants received an explanation of the research objectives, the nature of their involvement, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequence. Consent was obtained verbally and in writing prior to the interview. Confidentiality was maintained by disguising identities using pseudonyms, and personal data were stored securely. The researcher sought to minimize relational inequality during the interviews through a participatory and empathetic approach, creating a comfortable atmosphere for the informants to share their views openly.

3.5 Ethical approval

This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Graduate School of Hasanuddin University (Approval No. 01206/UN4.20.1/PT.01.04/2025 and 01202/UN4.20.1/PT.01.04/2025). The researchers have also obtained permission from the government office at the research location (Approval No. 42/IP/DPMPTNT/II/2025 and 0094/IP/DPMPTSP/2025).

3.6 Data analysis

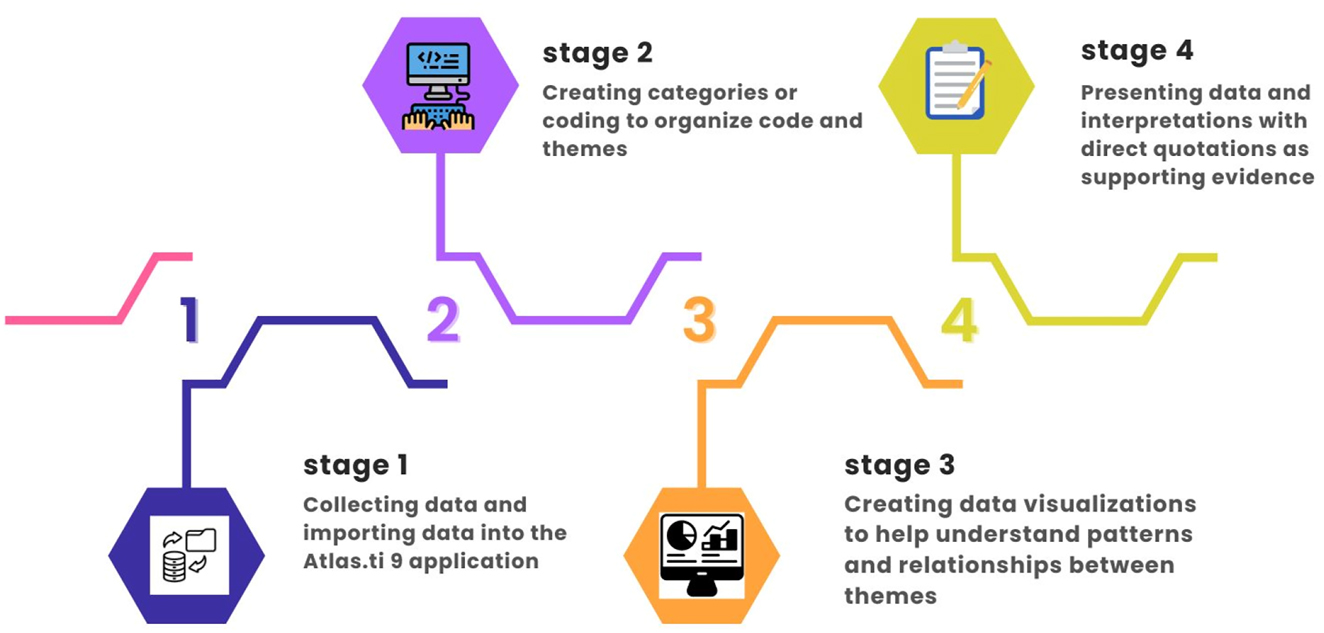

According to [64], data analysis is a systematic process of reviewing and collecting interview transcripts, field notes, documentation, and other materials to deepen understanding of the research focus, whether from observations, interviews, or documentation, to be used as the research findings. In this study, the researcher used ATLAS.ti 9 software to minimize the possibility of subjective errors in processing the data. ATLAS.ti is software that supports the qualitative data analysis process through location determination, coding or tagging, and annotation of elements in unstructured data sets. The data analysis process consists of several stages (Figure 2) [1]. Importing interview transcripts and field notes into the Atlas.ti software [2]. Creating categories or coding to organize codes and themes. The first coding process is open coding, which is the process of assigning codes to units of meaning relevant to the research focus. Second, axial coding [65], explains that axial coding is an advanced stage of analysis from open coding, which is carried out through a process of filtering, refining, and integrating the results of open coding. This stage aims to group codes that are related into categories or sub-themes, so that patterns of relationships between codes begin to form. Finally, selective coding is the process of selecting and integrating categories into main themes that comprehensively explain the research phenomenon [3]. Create data visualizations to clarify the relationships between themes and track the analysis to ensure the transparency, credibility, and replicability of the research results [66]. Reference [4] presenting data and interpretations in the form of reports accompanied by direct quotations from informants to support arguments. ATLAS.ti is widely used by researchers in various fields because of its ability to manage various types of data, including text, images, audio, videos, and geospatial data [67]. According to [68], using ATLAS.ti software in qualitative research provides significant benefits in facilitating a more systematic and in-depth data analysis process. ATLAS.ti features allow researchers to manage complex data, identify themes and patterns, and make more structured and accurate interpretations.

Stages of data analysis using the Atlas.ti 9 application. Source: Modified from Canva.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 The role of global actors in the natural silk agribusiness upstream

Amidst the efforts to revive the glory of silk in South Sulawesi, many parties have been working to restart the natural silk production cycle. This occurs in the context of high demand for silk thread that is not matched by available production. The decline in activity in the upstream sector, particularly in mulberry cultivation and silkworm rearing, indicates that most farmers have abandoned this business after the government assistance programs were discontinued. The presence of global actors shows a new dynamic, marked by increased demand for silk thread from India. This demand has been able to absorb thread stocks that were previously unsold, including thread that had been distributed from Soppeng Regency to Wajo Regency, to meet the volume of demand for export. This was facilitated by a silk activist, who stated the following:

In 2022, I happened to have an old acquaintance from India named Mr. T who wanted to revive the silk industry. He absorbed all the yarn from farmers that had not been sold during the Covid-19 pandemic. At that time, there was a demand for 600 kg of yarn from India, so he not only bought yarn from weavers, but he also requested a supply of yarn from yarn shops in Sengkang (the capital of Wajo Regency). (AM, silk activist and local seed supplier).

The presence of global actors in 2022, particularly from India and China, has become a turning point in reviving upstream activities, namely silkworm cultivation in Soppeng Regency. The entry of Chinese companies was initiated by an Indian entrepreneur who introduced this region’s potential to his Chinese business partners. The network has led to direct partnerships between foreign companies and local farmers. The partnership agreement stipulated that 70 % of cocoon production would be allocated for export to China, while the remaining 30 % would be absorbed by the domestic market, particularly through purchases by the South Sulawesi Provincial Government. A local seed supplier illustrated the followings.

In 2023, my boss from China brought seeds and guaranteed to buy back the farmers’ cocoons with an agreement that 70% would be for export and 30% for local needs. In 2025, all of our cocoon production will be absorbed by the export market. (A, Chinese Company Seed Supplier)

The role of global actors in upstream silk agribusiness activities in the Soppeng Regency consists of several categories, as shown in Table 1.

The role of global actors in upstream activities in Soppeng Regency.

| No. | Upstream activities | Role of global actors |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Mulberry cultivation | Providing mulberry cuttings |

| 2. | Silkworm maintenance | Distributing egg seeds |

| 3. | Rearing | Supplying cocooning equipment |

| 4. | Cocoon harvesting | Guaranteeing the purchase of farmers’ cocoon production |

4.1.1 Provision of mulberry leaf cuttings

Global actors not only play a role in supplying superior silkworm seeds but also facilitate upstream inputs in the form of mulberry cuttings. Through a partnership scheme, Chinese companies distribute mulberry cuttings to local farmers at no cost. This initiative is strategic in strengthening the upstream chain by increasing access to quality feed from the early stages of cultivation. The provision of mulberry cuttings by global actors has implications for both the quantity and quality of leaves produced. In addition, the agronomic quality of mulberry plants has improved significantly, as evidenced by the higher leaf productivity, disease resistance, and adaptability to the local climate. According to one farmer, the company provides mulberry seedlings before the silkworm cultivation process began.

For silkworms in the first instar stage, we feed them only the tips for two days. After that, we feed them older leaves. For mulberry trees in the past (in the 1980s), we followed recommendations from Japan. Starting from instar 1 with young leaves, instar 2 with young leaves, and then instar 5 with older leaves. So, based on my experience, the seedlings distributed by the company can be said to be superior. (M, Farmer).

4.1.2 Distribution of egg seeds

Production inputs in the form of genetically and technically superior imported silkworm seeds are directly distributed to farmers. This is a response to the limited productivity and quality of local seeds. Local seeds previously used by farmers often failed to hatch, had low environmental resistance, and produced low cocoon yields. In addition to quality, the technical aspects of distribution have changed. Imported silkworm seeds are distributed directly to farmers without intermediaries such as farmer groups and without the intervention of government agencies. The partnership mechanism is individual between global companies and farmers, with more attractive schemes, such as no fees deducted from the production value. This approach creates a more efficient and results-oriented system and reduces the administrative barriers that have previously slowed the distribution of production inputs. The function of production input providers not only improves the technical quality of cultivation, but also plays a strategic role in cocoon production upstream, which is greatly influenced by the existence and sustainability of supply from global actors. This was conveyed by several farmers, including the following.

The quality of the eggs used in the past and those currently used from the Chinese company are very different. The hatchability of silkworms in the past was low due to the very long storage period. In the past, if the group ordered 10 boxes from the government, not even one box would hatch. I once had a box of eggs that only yielded 4 kg. Currently, the seeds from the Chinese company are good, and the yield is also higher. These seeds are also more resistant to changes in weather. Farmers can now distinguish that local seeds are prone to disease, produce small cocoons, and yield fewer results than hybrid seeds. Seeds from China yield an average of 35–42 kg/box of cocoons. So now many farmers have switched to raising silkworm seeds from China. This is not only because the rearing period is short, but also because the number of cocoons produced is high. (M, Farmer).

4.1.3 Provision of cocooning equipment

The quality of cocoons as the end result of silkworm cultivation is greatly influenced by the cocooning process and the equipment used. The provision of cardboard cocooning equipment supplied by a Chinese partner company has provides a practical solution based on global production standards. The cocooning equipment was designed such that each silkworm had adequate individual space, allowing the cocooning process to proceed optimally without urine contamination or overcrowding. This differs from conventional practices that use bamboo or plastic media, where cocoons tend to be contaminated by dirt and are crowded, resulting in a decrease in selling value and thread quality. Based on interviews with farmers, it is known that the use of cardboard cocooning tools has a significant impact on cocoon quality.

In my opinion, a good cocooning method is one that uses cardboard because there is only one caterpillar in each column, and its urine is absorbed by the cardboard, so it does not contaminate the cocoon. If bamboo is used, the cocoons are usually dirty and the caterpillars pile up on top of each other. The best quality cocoons are produced using cardboard. If bamboo or plastic is used for cocooning, the caterpillars’ urine usually mixes with the cocoon, so the cocoons often have brown spots. (S, Farmer)

4.1.4 Cocoon purchase guarantee

The involvement of global actors plays a strategic role in creating market stability for local cocoon-producing farmers. The partnership model allows farmers to sell their cocoon harvest directly to partner companies without engaging in independent spinning or local intermediaries. Although there are no written contracts, these trade relationships operate within a trust-based partnership system that guarantees purchases and reduces market risk for farmers. The sales process is carried out directly at the partner’s warehouse, where the cocoons are weighed and paid for in cash on the spot at an agreed-upon price. This practice differs from the previous pattern, which relied on intermediaries and often caused payment delays. This also encourages the long-term sustainability of farmers’ businesses through a more efficient market mechanism that is responsive to the export demand. This was illustrated by several farmers, including the following:

The sale is made directly to the partner to weigh the cocoons. They are then paid immediately according to the results at a price of Rp. 60,000/kg of cocoons and paid in cash. Previously, they were sometimes paid only two months later. Sold directly to Chinese companies and paid in cash immediately, the system is a partnership without a written contract. Currently, most farmers who work with Chinese companies sell their products directly in the form of cocoons. (AMn, Farmer).

The presence of global actors working with local actors to develop the natural silk upstream sector has significantly revitalized silk cultivation activities at the farmer level. Global actors entered through direct partnership schemes with farmers and brought with them high-quality silkworm seeds that were in demand by farmers owing to their durability and good product quality. In addition, agreements to purchase farmers’ cocoon harvests provide certainty for farmers. This scheme indirectly revives the enthusiasm and optimism of farmers who had previously begun to abandon sericulture because of limited resources, trauma from declining production and demand, and minimal government intervention. This partnership model does not take the form of a farmer group institution as commonly found in government programs, but rather through social relationships between individual farmers and partner companies. This relationship model opens up new opportunities for farmers to return to active participation in the export-oriented cultivation cycle controlled by global actors, while still providing room for participation by local actors as the main producers of cocoon raw materials.

Many farmers hope that the entry of this Chinese company will restore the glory of silk to what it once was. Due to the current conditions, many have switched commodities to cocoa and dragon fruit. (S, Soppeng Regency Government Staff)

4.2 The role of global actors in the downstream natural silk agribusiness

The obstacle in the downstream activities of the silk woven fabric agribusiness in the Wajo Regency is the marketing of authentic woven fabrics. This is because of weak market demand and a significant decline in the availability of authentic silk raw materials, which has led to a decrease in production volume. Although the market prospects for woven silk fabrics remain high, the scarcity of raw materials is a major factor hindering their business development. The production of authentic silk woven fabrics is currently limited and only occurs when there are orders from consumers. This is because of the high price of authentic silk products, which is not commensurate with the community’s purchasing power. The following are statements from several informants regarding this (Table 2).

We only weave genuine silk products when there are orders for them. This is because genuine silk products are expensive. Moreover, raw materials are difficult to obtain and require more intensive care. (H. B, Silk Fabric Store Owner).

The current market outlook is still good, even though buyer interest has declined. One reason for this is the availability of numerous traditional clothing rental services. Five years ago, there was still a high demand for fabric for various events, but since the emergence of rental services, fabric sales have declined. (I.M., Silk Fabric Seller).

The role of global actors in downstream activities in Soppeng Regency.

| No. | Downstream activities | Role of global actors |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Spinning | – |

| 2. | Weaving | Supplying silk thread |

| 3. | Marketing | – |

The presence of global players has indirectly provides a supply of high-quality silk thread at relatively competitive prices as can be seen in Table 2. Imported silk threads from China and local silk thread differ in terms of price and quality. Although imported thread is more expensive than local thread, it is of more consistent quality, characterized by a uniform thread size and stable spinning results. This is in contrast to the local yarn, which often shows irregular sizes, making the weaving process difficult and affecting the quality of the resulting fabric. This inconsistency also influences consumer preferences for the final products This condition reflects the superiority of globally produced imported silk yarn in the silk supply chain through the use of modern spinning technology. Local yarn production still relies on manual processes that are limited in terms of efficiency and quality consistency. The presence of imported silk yarn not only affects the market structure but also indirectly becomes a benchmark for quality, affecting the competitiveness of local silk products in the domestic market. The following is a statement from a weaver who supported this statement:

The genuine silk thread I currently use is imported from China. Compared to the price of local thread, it is more expensive, ranging from Rp. 1,300,000 to 1,500,000, while local silk thread costs around Rp. 700,000 to 800,000. The quality of the thread is very different, as can be seen from the thickness of the thread produced by twisting. Imported threads from China are all of the same thickness, whereas local threads sometimes vary in thickness. This makes it difficult for weavers and affects the quality of the fabric produced, which buyers do not like (H. D, Weaver).

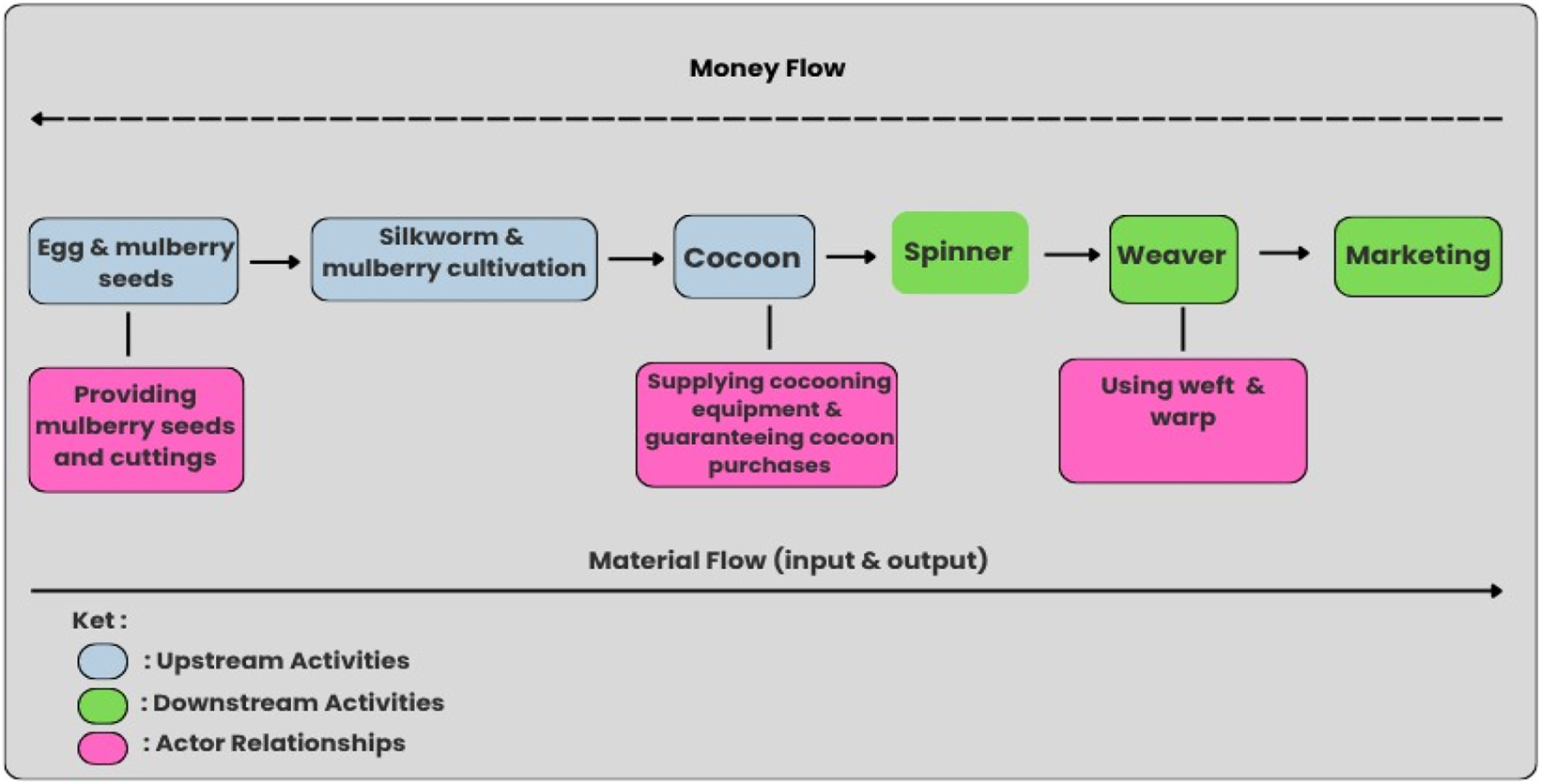

4.3 Actor interactions in the upstream–downstream integration of the silk agribusiness

The integration of the natural silk agribusiness between the upstream region of Soppeng and the downstream region of Wajo can be traced through the flow of output in the form of thread from Soppeng to Wajo, followed by the flow of money from downstream to upstream in the form of thread purchase transactions can be seen in Figure 3. This relationship reflects the economic link between the two regions in the silk agribusiness system. In the upstream sector, the sustainability of silk farmers’ businesses is inseparable from the presence of global actors, namely Chinese companies, which provide inputs for cultivation in the form of silkworm seeds, mulberry plants, reeling equipment, and guaranteed purchases of cocoons from partner farmers. Production activities in the upstream sector in recent years have occurred because of the support of global companies’ partnerships with farmers, not because of the structural strength of local actors. Market dynamics show that during certain periods, particularly when the supply of thread from Soppeng declined because of reduced silkworm production by farmers, production activities in Wajo continued because of the supply of imported thread from China and India. These countries acted as alternative suppliers of raw materials, enabling the continuity of the silk weaving industry, even though local production faced constraints in meeting market demand. A government official in Soppeng expressed concern about this in the following statement.

Actually, it is the upstream that must be maintained. This is because if there is no more thread supply from Soppeng, we can still import thread, and the downstream weaving process can still continue. However, the current situation in Soppeng is that most producers are selling raw silk cocoons to China. Therefore, the future challenge is how to resume silk thread production for spinning and weaving. (M. A, Government Staff of Wajo Regency).

Relationships between actors in the silk agribusiness supply chain.

The role of actors in the upstream sector can be seen in the continued existence of local production activities that originate from the use of domestically produced silkworm seeds with a profit-sharing scheme for farmers to cover the cost of seeds and hatching silkworms. This shows that local actors continue to perform their productive functions in the silk agribusiness system. Although local production in Soppeng is relatively small in volume, it still flows to Wajo in the form of yarn to be woven into silk fabric. This demonstrates the existence of a historically sustained domestic integration channel. However, the entry of global actors has introduced new dynamics to this system. On the one hand, the involvement of global actors contributes to maintaining the continuity of cocoon production through support for production inputs, markets and export demand. However, on the other hand, this poses challenges to independence and causes dependence, leading to a shift in the production structure, whereby cocoons that were previously spun into yarn at the local level are now exported directly without going through the spinning process. Consequently, the availability of raw materials for the spinning industry has become limited, and the role of local spinners as an important part of the silk agribusiness value chain has been marginalized, threatening the sustainability of their businesses. The shift in production orientation towards raw cocoon exports has significant social implications for the sustainability of local livelihoods, especially for spinners who have long depended on silk thread spinning activities. The loss of spinning activities also has an impact on household income. Spinning work has shifted to become an unattractive livelihood option because it is not economically promising. Many spinners have switched to other more profitable jobs, considering the effort and benefits they receive.

Farmers now sell their cocoons directly to China. I used to spin, and people would bring their cocoons here, but that is rarely done now because they are sold in the form of cocoons. When I spin, I finish first and then ask the owner to take the thread. The problem now is that all the spinners don’t have cocoons to spin because they’ve been sold to China. Under the current conditions, this work has greatly decreased, not only because there are fewer cocoons but also because it’s not attractive anymore, especially since many people use non-silk materials locally called “sabbe-sabbe.” I have also started to leave this work and choose to sell at the market. (Hj. M Spinner)

The role of actors in the downstream sector can be seen in the use of yarn to produce silk-woven fabric. Yarn spun in Soppeng traditionally has lower quality and price compared to imported silk yarn, so it can only be used as weft (yarn that is installed horizontally and woven through the warp yarn to make fabric) in the silk fabric weaving process. This limitation in quality means that the yarn does not meet the standards for use as a warp (yarn that is placed vertically on the loom and forms the basis of the woven fabric), which requires greater strength and consistency. In this context, there has been an adaptive functional integration on the part of the weaving industry in Wajo, namely by combining local weft yarn from traditional spinners with imported warp yarn from China. This strategy is implemented to balance the production cost efficiency and quality assurance of woven products that meet market preferences. This integration demonstrates the synchronization of roles between local and global actors, where the role of local yarn is maintained as an important component, while the quality of imported yarn supports the production of woven fabrics with higher selling value. This integrative practice not only reflects a response to yarn quality disparities but also serves as a sustainability strategy that combines local resources with global inputs to maintain production continuity and product competitiveness in the market. Weavers and silk traders express it as follows.

The silk I use is authentic silk. For the authentic silk yarn, I order it from Mrs. R (Soppeng), while for the lusy yarn, I buy it at the Sengkang store (imported from China). Nowadays, local yarn is scarce because Chinese companies have taken over the cocoons in Soppeng. This is also difficult because the price of local yarn has increased, but the price of authentic silk fabric has not. (H. D, Weaver).

The production of authentic silk is also rare because, in addition to its higher price, it requires special care, as it cannot be washed directly and its colors can fade over time. The motifs that can be made are also limited, usually only tie-dye motifs. The raw silk thread from Soppeng is only used as feed, while the lusian thread is imported from China. (H. N, Silk Fabric Trader).

4.4 Global actors and the sustainability of the natural silk agribusiness supply chain

There are four main categories and twelve subcategories in the upstream–downstream integration of the silk agribusiness that is the focus of this study. The results show similarities in the interactions between actors upstream and downstream, namely silkworm cultivation inputs and raw materials for weaving, as shown in Figure 4.

Categories and subcategories related to the roles of global actors in upstream–downstream integration.

The sustainability of upstream–downstream integration in the natural silk agribusiness in this region is not entirely based on the internal synergy between local actors. It is greatly influenced by the presence of global actors who play a strategic role as the main drivers of the sustainability of the upstream production system. The integration between the upstream and downstream sectors, which was initially locally based, began to undergo structural changes with the entry of external interventions. This is consistent with the principle of performativity in ANT. In the context of supply chain management, this principle challenges the notion that integration is a predetermined outcome. Instead, ANT views integration as an ongoing achievement that emerges from the interactions and translations among actors in specific practices. Integration is not a static state, but a dynamic and evolving process over time [47], 48], 50], 69]. The assistance provided by global actors in the upstream sector, such as the provision of silkworm seeds, mulberry plants, cocooning equipment, and guaranteed cocoon purchases, has increased silkworm farmers’ production and impacted farmers’ social and environmental income. This is in line with the research [70] that silkworm farming in China, Brazil, and India has successfully increased agricultural yields and smallholder farmers’ income through income diversification with low initial costs. Furthermore, sericulture has the potential to contribute to the development of developing countries through the implementation of a sustainable circular economy and can reduce carbon emissions if the supply chain is managed carefully and efficiently. Research [71] has shown that one of the factors that can determine success in silkworm rearing is the use of superior silkworm seeds. Furthermore, according to [72], 73], the availability of silkworm feed, namely mulberry leaves, is crucial to ensure healthy silkworm growth. High-quality, high-quantity, and high-productivity mulberry leaves as silkworm feed will affect the production and quality of the cocoons produced [74], 75]. The expansion of mulberry cultivation for silkworm feed can positively impact environmental conservation, as mulberry trees are conservation plants that can improve water and soil quality [76] and enhance air quality through carbon absorption [77]. Additionally, high biomass production makes it more suitable and adoptable for cultivation in environments contaminated with various soil pollutants [78], 79]. It also plays a significant role in environmental cleanup through the bioremediation of contaminated sites (soil, air, and water) and carbon sequestration [80]. The material and structure of the cocooning site greatly influence the temperature and humidity that affect the quality of the cocoons and filaments, as well as the labor required for cocooning and harvesting the cocoons [81].

Silkworm farming is an economically viable alternative for both women and men because it can be done around the home and provides a source of income. The involvement of men and women in the natural silk industry in South Sulawesi can contribute to household income [82]. This can be seen from the amount of time women spend working in each subsystem of the natural silk agribusiness, starting from the initial stages of mulberry cultivation and silkworm rearing to spinning, weaving, and the production and distribution of silk fabrics. Women are extensively involved in various aspects of the silk industry [83]. The role of women in the silk cultivation process in India is extraordinary in helping to reduce unemployment, which is a problem among rural women. The involvement of women in the household confirms that silk cultivation not only improves the welfare of the poor but also functions in activities that promote gender equality in rural India [84].

As global actors, Chinese companies have driven competitive natural silk production in the international market and created new dependencies for farmers on external resources. This is consistent with the finding [85] that the proactive involvement of external parties in a supply chain can generate competitive advantages and encourage competition by creating a need to emulate sustainable practices. Silkworm farmers in Soppeng are geared toward exporting cocoons, that can shift the orientation of agribusiness from the domestic scale to the global market. This transformation not only impacts the technical aspects of production but also reshapes power relations and networks within the natural silk agribusiness system. Global actors have succeeded in playing a dominant role in the function of input providers, replacing the role of local actors and the state, which has not been optimal in supporting the sustainability of silk cultivation. According to [86], 87], this shows how the different characteristics and activities of global actors enable them to exert a strong and widespread influence throughout the world and in regions that were previously the exclusive domain of the state.

The dominance of global actors in the natural silk agribusiness supply chain has shown the limited sustainability of local actors. Although local production continues, its role has become secondary to a system controlled by the interests of global actors operating within the framework of the global value chain. According to [88], the application of the concept of sustainable economy in the supply chain can face several obstacles owing to the behavior and interactions of actors in the supply chain. This is in line with the relational principle in ANT, which does not assume that the structure of the supply chain exists a priori to its construction. Instead, this theory studies how structures are formed through relational interactions. This approach differs from the functionalist perspective, which views the supply chain as a pre-designed system with predetermined roles [47], 48], 50], 69]. As a result, the role of local actors in regulating the flow of products and value in the silk agribusiness chain has begun to be displaced by global actors, as seen in the power and interest relations between local and global actors. This is in line with the opinion [89] that power is created between actors, in which power relations are not only in the form of powerful actors but can also be in the form of who controls and who is controlled. In the context of upstream–downstream integration, the production inputs provided by global actors enable the continuity of cocoon supply for export and local needs, while reviving the upstream chain that was previously disrupted due to weak input and market support.

The role of global actors influences the direction of production and transaction patterns in the upstream sector, particularly in the procurement of silkworm seeds and the purchase of raw cocoons for export. Dependence on global markets and actors can weaken local governments’ ability to regulate production mechanisms and manage local resources. In the long term, this condition can create structural vulnerability when fluctuations in demand or import policies of partner countries have a direct impact on farmers’ incomes due to external changes. This is in line with the opinion [11] that there are many challenges in the development of silkworms in Indonesia, both at the upstream and downstream levels; therefore, commitment, cooperation, and action from all stakeholders are needed to improve silkworm development. Local governments can strengthen local institutions and production independence through sustainable practices, such as sustainable practices in the silk and textile industries in Europe, which require strong collaboration between farmers, stakeholders, and local governments. This synergy must be maintained through close relationships with the central government and non-governmental organizations so that best practices can be implemented responsibly at every level and throughout the production cycle [90].

The intervention of global actors plays an important role in maintaining the sustainability of cocoon production, but on the other hand, it poses challenges to the independence and internal capacity of local actors. This dependence has structural consequences, one of which is the marginalization of local actors, such as those involved in yarn spinning. The results of the study [91] conclude that the long-term influence of global actors can increase local unemployment. This occurs because farmers’ production, which is usually spun into yarn, is now exported directly in the form of cocoons without going through the spinning process at the local level. Raw materials for spinning have become scarce, thus reducing the role and contribution of local actors in the silk agribusiness chain. This is in line with the findings [92] that the roles, activities, and interaction patterns of actors in the supply chain are key factors that determine the success of a system. Farmers’ dependence on global inputs has become a new reality that shapes the direction of natural silk agribusiness sustainability at the local level. According to [93], sustainability is an important element in designing supply chain networks, although ensuring sustainability across the entire value chain is difficult and requires collaborative efforts and transparency among stakeholders [94]. Upstream and downstream integration no longer depends entirely on synergies between local regions but is increasingly determined by the intervention and involvement of external parties with access to technology, superior seeds, and international markets. This approach is in line with the principle of heterogeneity in network actor theory, which asserts that every actor, whether human or non-human, has the ability to act and should be treated seriously [47], 48], 50], 95]. In the context of supply chain management, technology, processes, and inanimate objects can play an important role in shaping the supply chain. This differs from the traditional supply chain management approach, which often places greater emphasis on the role of human actors [47], [48], [49], [50]. The role of global actors downstream through the supply of high-quality yarn is a key factor in overcoming local quality disparities while strengthening product competitiveness through international trade networks. This is in line with the findings [96] that integration with external partners, including suppliers and customers, significantly affects producers’ quality practices and performance. In the context of global competition, quality is not solely the responsibility of the end producer, but is a shared commitment of the entire supply chain to ensure customer satisfaction.

5 Conclusions

Based on the results of the case studies conducted in Soppeng and Wajo, it can be concluded that the sustainability of upstream–downstream integration in the natural silk agribusiness is influenced by the interaction between local and global actors. Although there are still local production activities based on domestic seeds, their scale and impact are relatively small compared to production systems controlled by global actors. Global actors play an important role not only as providers of production inputs in the upstream sector (importing silkworm seeds, mulberry seeds, and cocooning tools), but also as export market connectors through cocoon purchasing activities in the global value chain scheme. The sustainability of the output flow from the upstream to downstream sectors, which was previously supported by relationships between local actors, is now increasingly dependent on external presence and interventions. The weaving industry in Wajo can continue to operate even though the supply of yarn from Soppeng has decreased because it relies on imported yarn. However, the direct export of cocoons from Soppeng farmers to the global market has displaced the role of traditional local spinners, thereby weakening the local supply chain structure and increasing dependence on external markets for raw silk supply. The interaction between global and local actors has created an unbalanced relationship in which the sustainability of the agribusiness system is determined more by external dynamics and support than by internal capabilities.

The sustainability of the natural silk supply chain requires a strategy that combines the role of global actors as market and technology facilitators with strengthening local capacity in seed production, farming institutions, and supply chain governance. This integration will minimize the risk of dependence on external partners while ensuring the sustainability of the natural silk agribusiness in terms of farmers’ economic well-being, environmental sustainability, and social relations within the community. Therefore, local governments can facilitate a hybrid partnership model between global companies and local institutions. This approach combines the capital, technology, and market networks of global companies with the local knowledge, skilled labor, and natural resources of local communities. Furthermore, implementing export quota mechanisms or restrictions on raw cocoon exports by setting a minimum proportion of local absorption before export can ensure that the raw material needs of spinners are met and encourage the formation of formal partnerships, such as silk cooperatives or village-owned enterprises (BUMDes), between upstream and downstream actors in an integrated business chain.

This study had several limitations. First, the use of purposive and snowball sampling techniques has the potential to cause selection bias because the informants involved tend to come from the same social network, so that the views of other actors are not fully represented. Second, the cross-sectional approach only describes conditions at a certain period, so it is not able to capture seasonal dynamics or long-term changes in the silk production and marketing system. Third, this study has limitations in thoroughly tracing the global silk value chain, particularly regarding the dynamics of cocoon exports from Soppeng to China and the supply of imported silk yarn from China used by the weaving industry in Wajo. To overcome these limitations, future research should use a long-term approach to observe changes in sustainability practices over time. In addition, the application of a more diverse sampling strategy could broaden the scope of perspectives and reduce potential representation bias in future studies. Finally, a more comprehensive follow-up study is needed to examine the relationship between international trade cycles and the sustainability of the local weaving industry.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Institute for Research and Community Service at Hasanuddin University for their support in conducting this research.

-

Funding: This research was funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia based on Contract Number: 02209/UN4.22/PT.01.03/2025.

-

Author contributions: All authors are responsible for the entire content of this manuscript and agree to its submission to the journal, review all results, and approve the final version of the manuscript. RR: Writing, data analysis, methodology, draft preparation and software. DS: Supervision, conceptualization, methodology validation, review, data curation, and draft editing. R: Data validation and manuscript review. AS: Supervision, review, and editing.

-

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in the writing of this manuscript.

-

Data availability statement: The dataset generated during the current study is available from the authors and can be accessed upon reasonable request.

References

1. Giacomin, AM, Garcia, JB, Zonatti, WF, Santos, SMC, Laktim, MC, Ramos, BJ. Brazilian silk production: economic and sustainability aspects. Procedia Eng 2017;200:89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2017.07.014.Suche in Google Scholar

2. Meneguim, AM, Lovato, L, Silva, DRZ, Yamaoka, RS, Nagashima, GT, Pasini, EA. Morus Bombyx mori. PR Neotrop Entomol 2007;6001:670–4.10.1590/S1519-566X2007000500006Suche in Google Scholar

3. Altman, GH, Farrell, BD. Sericulture as a sustainable agroindustry. Clean Circ Bioecon 2022;2:100011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcb.2022.100011.Suche in Google Scholar

4. Zhou, K, Yuan, T, Wang, S, Hu, F, Luo, L, Chen, L, et al.. Beyond natural silk: bioengineered silk fibroin for bone regeneration. Mater Today Bio 2025;33:102014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.102014.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

5. Czaplicki, Z, Gliścińska, E, Machnowski, W. Natural silk – an unusual fiber: origin, processing and world production. Fibres Text East Eur 2021;29:22–8. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0014.9291.Suche in Google Scholar

6. Thiripura Sundari, K. Silk production: the global scenario. Asian Rev Soc Sci 2018;7:22–4. https://doi.org/10.51983/arss-2018.7.2.1435.Suche in Google Scholar

7. Muin, N, Isnan, W. Silk farmers’ strategies in meeting household needs in Soppeng Regency, South Sulawesi. Talent Conf Ser Agric Nat Resour 2019;2:26–33. https://doi.org/10.32734/anr.v2i1.570.Suche in Google Scholar

8. Nuraeni, S. Gaps in the thread: disease, production, and opportunity in the failing silk industry of South Sulawesi. For Soc 2017;1:110–20. https://doi.org/10.24259/fs.v1i2.1861.Suche in Google Scholar

9. Agustarini, R, Andadari, L, Minarningsih, Dewi, R Conservation and breeding of natural silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) in Indonesia. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2020;533:012004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/533/1/012004.Suche in Google Scholar

10. Iwang, B, Sudirman. The role of the government in promoting silk companies in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Southeast Asian Soc Sci Rev 2020;5:103–32. https://doi.org/10.29945/SEASSR.202005_5(1).0005.Suche in Google Scholar

11. Andadari, L, Yuniati, D, Supriyanto, B, Murniati, Suharti, S, Widarti, A, et al.. Lens on tropical sericulture development in Indonesia: recent status and future directions for industry and social forestry. Insects 2022;13:913. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13100913.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Rasuljonovich, KR. An economic analysis of sericulture in the Republic of Uzbekistan and development of its competitiveness. J Pharmaceut Neg Res 2022;13:3820–3827. https://doi.org/10.47750/pnr.2022.13.S06.509.Suche in Google Scholar

13. Patichol, P, Wongsurawat, W, Johri, LM. Upgrade strategies in the Thai silk industry: balancing value promotion and cultural heritage. J Fash Mark Manag 2014;18:20–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-09-2011-0059.Suche in Google Scholar

14. Ashar, NM, Bulkis, S, Rahmadanih, R, Tenriawaru, AN, Busthanul, N. Income of female workers in natural silk agribusiness. Indones Agribus J 2023;11:136–49. https://doi.org/10.29244/jai.2023.11.1.136-149.Suche in Google Scholar

15. Isnan, W. Perception and motivation of farmers in the development of natural silk business in Soppeng Regency, South Sulawesi. Wasian J 2019;6:1–10. https://doi.org/10.20886/jwas.v6i1.4638.Suche in Google Scholar

16. Hidayatullah, Y, Haerunnisa, M, Syah, UT. Business strategies for the development of natural silk in Walennae Village, Sabbangparu District, Wajo Regency. Agrotani Sci J 2021;3:53–61. https://doi.org/10.54339/agrotani.v3i2.246.Suche in Google Scholar

17. Yuniarti, A, Prayudhi, P, Faisal, F, Nur, AW, Aldi, A. Transformation of silk weaving through collaboration with universities in the digital Age. J Humanit Educ 2024;4:160–6. https://doi.org/10.31004/jh.v4i2.739.Suche in Google Scholar

18. Huang, W, Ling, S, Li, C, Omenetto, FG, Kaplan, DL. Silkworm silk-based materials and devices generated using bio-nanotechnology. Chem Soc Rev 2018;47:6486–504. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CS00187A.Suche in Google Scholar

19. Tran, S, Jorcano, S, Falco, T, Lamanna, G, Miralbell, R, Zilli, T. Oligorecurrent nodal prostate cancer. Am J Clin Oncol Cancer Clin Trials 2021;41:960–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/COC.0000000000000419.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

20. Barreiro, LD, Yeo, J, Tarakanova, A, Martin-Martinez, FJ, Buehler, MJ Multiscale modeling of silk and silk-based biomaterials – a review. Macromol Biosci 2019; 9:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/mabi.201970007.Suche in Google Scholar

21. Tenriawaru, AN, Fudjaja, L, Jamil, MH, Rukka, RM, Anisa, A, Halil. Natural silk agroindustry in Wajo Regency. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2021;807:032057. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/807/3/032057.Suche in Google Scholar

22. Widiarti, A, Andadari, L, Suharti, S, Heryati, Y, Yuniati, D, Agustarini, R. Partnership model for sericulture development to improve farmer’s welfare (a case study at Bina Mandiri farmer group in Sukabumi Regency). IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2021;917:012009. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/917/1/012009.Suche in Google Scholar

23. Ashar, NM, Nurmalina, R, Muflikh, YN. Natural silk agribusiness development strategy in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. Agro Bali: Agric J 2024;7:810–23. https://doi.org/10.37637/ab.v7i3.1915.Suche in Google Scholar

24. Tolinggi, WK, Salman, D, Rahmadanih, IH. Farmer regeneration and knowledge co-creation in the sustainability of coconut agribusiness in Gorontalo, Indonesia. Open Agric 2023;8:20220162. https://doi.org/10.1515/opag-2022-0162.Suche in Google Scholar

25. Bahtiar; Arsyad, M; Salman, D; Azrai, M; Tenrirawe, A; Yasin, M; Gaffar, A , et al.. Promoting new superior varieties of national hybrid corn: increasing farmer satisfaction to increase production. Agriculture 2023;13:174. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13010174.Suche in Google Scholar

26. Sulolipu, AA, Soetjipto, BE, Wahyono, H, Haryono, A. Silk weaving business sustainability as a cultural heritage of Indonesia: a case study in Wajo Regency, South Sulawesi. Ind Textil 2022;73:184–90. https://doi.org/10.35530/IT.073.02.202056.Suche in Google Scholar

27. Islam, S, Shill, AC, Alam, S, Asha, AA, Hossain, R. Silk industry supply chain complexity: a comparative study on finding the gap between demand and supply. Supply Chain Insider 2023;11:2617–7420. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10030828.Suche in Google Scholar

28. Wang, Q, Yang, X. Analysis on the development of China’s modern silk industry. Asian Soc Sci 2022;18:27. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v18n4p27.Suche in Google Scholar

29. Halide, L, Sirajuddin, SN, Demmalinno, EB, Saddapotto, A, Rahim, L, Nurlaelah, S, et al.. Interconnection of actors in sustainable natural silk management in Soppeng District. J Lifestyle SDGs Rev 2025;5:e05924. https://doi.org/10.47172/2965-730x.sdgsreview.v5.n03.pe05924.Suche in Google Scholar

30. Rees, GH, MacDonell, S. Data gathering for actor analyses: a research note on the collection and aggregation of individual respondent data for MACTOR. Future Stud Res J Trends Strateg 2017;9:115–37. https://doi.org/10.24023/FutureJournal/2175-5825/2017.v9i1.256.Suche in Google Scholar

31. Avelino, F, Wittmayer, JM. Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: a multi-actor perspective. J Environ Pol Plann 2016;18:628–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1112259.Suche in Google Scholar

32. Wittmayer, JM, Avelino, F, Steenbergen, VF, Loorbach, D. The role of actors in transition: insights from a sociological perspective. Enviro Innov Soc Trans 2017;24:45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2016.10.003.Suche in Google Scholar

33. Yuniningsih, T, Sriwahyuni, N. Government-Business Partnerships (GBPs) in tourism development in Semarang City. J Publ Sect Innov 2018;3:84–93. https://doi.org/10.26740/jpsi.v3n2.p84-93.Suche in Google Scholar

34. Farida, AN, Sambodo, R, Astriani, D, Dinarto, W. Empowerment analysis of the Guyub Rukun Women Farmers Group through the Development Program of the Biodiversity Collection Park of Potential Medicinal Plants in Sundi Kidul Hamlet, Argorejo Village. Sedayu, Bantul. Agribus Media 2022;6:243–9. https://doi.org/10.35326/agribisnis.v6i2.2861.Suche in Google Scholar

35. Indriasari, R, Nurcahyanto, H. Stakeholder collaboration in empowered communities (case study in Wonoyoso Village, Pringapus District, Semarang Regency). J Publ Policy Manag Rev 2018;8:97–112. https://doi.org/10.14710/jppmr.v8i1.22729.Suche in Google Scholar

36. Indriasari, S, Sensuse, DI, Resti, Y, Wurzinger, M, Hidayat, DS, Widodo, B. Requirements engineering of knowledge management system for smallholder dairy farmers. J Hum Earth Future 2024;5:151–72. https://doi.org/10.28991/HEF-2024-05-02-02.Suche in Google Scholar

37. Xie, G, Su, X, Huang, M. Social media, knowledge management, and learning in farmer innovation. HighTech Innov J 2024;5:295–311. https://doi.org/10.28991/HIJ-2024-05-02-06.Suche in Google Scholar

38. Anbananthen, KSM, Muthaiyah, S, Thiyagarajan, S, Balasubramaniam, B, Yousif, YB, Mohammad, S, et al.. Evaluating enterprise architecture frameworks for digital transformation in agriculture. J Hum Earth Future 2024;5:761–72. https://doi.org/10.28991/HEF-2024-05-04-015.Suche in Google Scholar

39. Hasan, FM, Afifuddin, M, Abdullah, A. Relationship and influence of material supply chain risk factors on building construction project performance in Pidie Jaya and Bireuen Regencies. J Civil Eng Plann Arch 2019;2:362–71. https://doi.org/10.24815/jarsp.v2i4.14953.Suche in Google Scholar

40. Zamora, EA. Value chain analysis: a brief review. Asian J Innovation Policy 2016;5:116–28. https://doi.org/10.7545/ajip.2016.5.2.116.Suche in Google Scholar

41. Ramanathan, U, Gunasekaran, A. Supply chain collaboration: impact of success in long-term partnerships. Int J Prod Econ 2014;147:252–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2012.06.002.Suche in Google Scholar

42. Duhamel, PN, Pathak, S, Yii, JLC, Thammachote, P. Exploring critical success factors in agritourism: a mixed-methods approach. J Hum Earth Future 2024;5:421–37. https://doi.org/10.28991/HEF-2024-05-03-08.Suche in Google Scholar

43. Ermini, C, Visintin, F, Boffelli, A. Understanding supply chain orchestration mechanisms to achieve sustainability-oriented innovation in the textile and fashion industry. Sustain Prod Consum 2024;49:415–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2024.07.008.Suche in Google Scholar

44. Azadi, M, Jafarian, M, Saen, RF, Mirhedayatian, SM. A new fuzzy DEA model for evaluation of efficiency and effectiveness of suppliers in sustainable supply chain management context. Comput Oper Res 2015;54:274–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2014.03.002.Suche in Google Scholar

45. Acquaye, AA, Yamoah, FA, Ibn-Mohammed, T, Quaye, E, Yawson, DE. Equitable global value chain and production network as a driver for enhanced sustainability in developing economies. Sustainability 2023;15:14550. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914550.Suche in Google Scholar

46. Maró, ZM, Török, Á. China’s new silk road and central and Eastern Europe – a systematic literature review. Sustainability 2022;14:1801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031801.Suche in Google Scholar

47. Hald, KS, Spring, M. Actor-network theory: a novel approach to supply chain management theory development. J Supply Chain Manag 2023;59:87–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12296.Suche in Google Scholar

48. Mason, K, Kjellberg, H, Hagberg, J, editors. Marketing performativity: theories, practices and devices. Milton Park: Routledge; 2018.10.4324/9781315300238Suche in Google Scholar

49. Çalışkan, K, Callon, M. Economization, part 1: shifting attention from the economy towards processes of economization. Econ Soc 2009;38:369–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140903020580.Suche in Google Scholar

50. Abboubi, ME, Pinnington, AH, Clegg, SR, Nicolopoulou, K. Involving, countering, and overlooking stakeholder networks in soft regulation: case study of a small-to medium-sized enterprise’s implementation of SA8000. Bus Soc 2022;61:1594–630. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503211017508.Suche in Google Scholar

51. Romo Bacco, CE, Parga-Montoya, N, Del Carmen Montoya Landeros, M, Cortés-Palacios, HA, García Vidales, MY. Analysis of the establishment, development and future of agricultural reconversion. J Hum Earth Future;20245:543–59.10.28991/HEF-2024-05-04-01Suche in Google Scholar

52. Babu, KM. Natural textile fibers: animal and silk fibers. In: Textiles and fashion. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2015:57–78 pp.10.1016/B978-1-84569-931-4.00003-9Suche in Google Scholar

53. Moulaert, F, Martinelli, F, Swyngedouw, E, González, S. Towards alternative model(s) of local innovation. Urban Stud 2005;42:1969–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980500279893.Suche in Google Scholar

54. Khan, N, Subbarao, A, Khan, S, Siddika, A. Cultivating change: empowering communities among elderly through social innovation and entrepreneurship in smart urban farming. J Hum Earth Future 2024;5:483–98. https://doi.org/10.28991/HEF-2024-05-03-012.Suche in Google Scholar

55. Adana, AH. The future of Indonesian agribusiness: developing Indonesian agriculture based on local products. Muhammadiyah University of Malang; 2024.Suche in Google Scholar

56. Flynn, BB, Huo, B, Zhao, X. The impact of supply chain integration on performance: a contingency and configuration approach. J Oper Manag 2010;28:58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.06.001.Suche in Google Scholar

57. Aggrey, GAB, Kusi, LY, Afum, E, Osei-Ahenkan, VY, Norman, C, Boateng, KB, et al.. Firm performance implications of supply chain integration, agility and innovation in agri-businesses: evidence from an emergent economy. J Agribus Dev Emerg Econ 2022;12:320–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/JADEE-03-2021-0078.Suche in Google Scholar

58. Cresswell, J. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication; 2013.Suche in Google Scholar

59. Cresswell, JW, Creswell, JD. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Newbury Park: Sage publications; 2017.Suche in Google Scholar

60. Bungin, B. Qualitative research methodology: methodological actualization towards contemporary variants. Jakarta: Rajawali Pers; 2011.Suche in Google Scholar

61. Sugiyono. Metode Penelitian Kuantitatif, Kualitatif, dan R&D. Bandung: ALFABETA.Suche in Google Scholar

62. Morse, JM. Data were saturated. Qual Health Res 2015;25:587–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315576699.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

63. Abduh, M, Alawiyah, T, Apriansyah, G, Sirodj, RA, Afgani, MW. Survey design: cross sectional dalam Penelitian Kualitatif. J Sci Comput Educ 2022;3:31–9. https://doi.org/10.47709/jpsk.v3i01.1955.Suche in Google Scholar

64. Bogdan & Biklen. Qualitative research for education: an introduction to theory and methods. Allyn and Bacon, Inc.; 1982.Suche in Google Scholar

65. Bertolozzi-Caredio, D, Bardaji, I, Coopmans, I, Soriano, B, Garrido, A. Key steps and dynamics of family farm succession in marginal extensive livestock farming. J Rural Stud 2020;76:131–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.04.030.Suche in Google Scholar

66. Friese, S. Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS.ti, 3rd ed London: SAGE Publications; 2019.Suche in Google Scholar

67. Lewins, A, Silver, C. Using software in qualitative research: a step by step guide. London: Sage Publication, Inc.; 2007.10.4135/9780857025012Suche in Google Scholar

68. Tumanggor, S, Tanjung, H, Pasaribu, A, Simbolon, SNI, Pasaribu, I. Qualitative data analysis software (a study of the use of ATLAS.Ti software in qualitative research). Al-Muhajirin: J Islamic Educ 2024;1. https://doi.org/10.63911/jhynfn10.Suche in Google Scholar

69. Díaz Andrade, A, Urquhart, C. The affordances of actor network theory in ICT for development research. Inf Technol People 2010;23:52–374. https://doi.org/10.1108/09593841011087806.Suche in Google Scholar

70. Mushtaq, R, Qadiri, B, Lone, FA, Raja, TA, Singh, H, Ahmed, P, et al.. Role of sericulture in achieving sustainable development goals. Problemy Ekorozwoju 2023;18:199–206. https://doi.org/10.35784/pe.2023.1.21.Suche in Google Scholar

71. Chauchan, T, Tayal, MK. Mulberry sericulture. In: Industrial entomology. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pte. Ltd; 2017:1–465 pp.10.1007/978-981-10-3304-9_8Suche in Google Scholar

72. Batara, AW, Mahyuddin, Sadapotto, A Factors affecting traditional spinning silk yarn quality in the Soppeng Regency, Indonesia, and optimisation strategies. J Glob Innov Agricult Sci2014;12:1099–107. https://doi.org/10.22194/JGIAS/24.1435.Suche in Google Scholar

73. Faradilla, F, Alias, S. High-quality silk yarn products through sericulture techniques using in vitro-developed feed. Jurnal Hutan Tropis 2017;5:151–7. https://doi.org/10.20527/jht.v5i2.4369.Suche in Google Scholar

74. Setiadi, W, Kasno, Haneda, NF The use of organic fertilizer to increase the productivity of mulberry leaves (sp.) as food for silkworms (L.). Bombyx mori. J Trop Silvic, 2011;2, 165-70. https://doi.org/10.29244/j-siltrop.2.3.%25p.Suche in Google Scholar

75. Muin, N, Suryanto, H, Minarningsih, M, Minarningsih. Testing hybrids and Morus khunpai M. indica as silkworm (Linn.) feed. Bombyx Mori. Wallacea For Res J 2015;4:137–45. https://doi.org/10.18330/jwallacea.2015.vol4iss2pp137-145.Suche in Google Scholar

76. Liu, Y, Willison, JHM, Wan, P, Xiong, X, Ou, Y, Huang, X, et al.. Mulberry trees conserved soil and protected water quality in the riparian zone of the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Environ Sci Pollut Control Ser 2016;23:5288–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-5731-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

77. Manzoor, S, Qayoom, K. Environmental importance of mulberry: a review. J Exp Agric Int 2024;6:95–105. https://doi.org/10.9734/jeai/2024/v46i82681.Suche in Google Scholar

78. Peng, X, Yang, B, Deng, D, Dong, J, Chen, Z. Lead tolerance and accumulation in three cultivars of Eucalyptus urophylla×E. grandis: implication for phytoremediation. Environ Earth Sci 2012;67:1515–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-012-1595-1.Suche in Google Scholar