Abstract

Black glutinous rice is a local pigmented rice that attracts the interest of many people due to its high nutritional value. While cultivating, black glutinous rice may experience abiotic stresses, such as drought and salinity threat. Drought and salinity may lead to oxidative stress, which leads to the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Moreover, the enzymatic defense mechanism of black glutinous rice against ROS, which depends on the stress type and the plant’s growth stages, remains unclear. This study was performed to determine the defense response of black glutinous rice to drought (10% PEG) and salinity (80 mM NaCl) stresses at different growth stages (vegetative [V], reproductive [R], and vegetative+reproductive [V+R]) and then continued to recover at every growth stage. This study showed enhanced accumulation of ROS under drought and salinity stresses, with the reproductive stage presenting the highest accumulation of hydrogen peroxide and malondialdehyde. In contrast, the recovery phase decreased the ROS accumulation. The antioxidant enzyme activities (catalase [CAT], ascorbate peroxidase [APX], and peroxidase [POD]) showed different responses between the biochemical and transcript levels of antioxidant genes (OsCATA, OsAPX, and OsPOD) during stress and in the recovery phase. These results indicate the foundation for elucidating the defense mechanism response of black glutinous rice to different growth stages and stresses, such as drought and salinity.

1 Introduction

The nutritional value of food plants is often improved to prevent malnutrition and meet the health needs of the community. Pigmented rice has been widely cultivated as an alternative food plant that contains highly bioactive compounds [1]. Black glutinous rice is one of the most notable types of pigmented rice, which contains high amounts of phenols, flavonoids, and anthocyanins [2]. Cyanidin-3-glucoside (C3G) and peonidin-3-glucoside (P3G) are the most abundant anthocyanins in black glutinous rice and are reported to have antioxidant properties [3]. These natural antioxidants in black glutinous rice provide broader cultivation opportunities for the food and pharmaceutical industries.

However, stress resistance mechanisms in black glutinous rice remain unclear. Previous studies of black glutinous rice have primarily focused on the bioactive content and health benefits [2], while its potential role in oxidative stress has received limited attention. The antioxidant potential of black glutinous rice, which plays an essential role in health, is scrutinized regarding its role when plants are exposed to stressful environments. Drought and salinity stresses disrupt plant growth and productivity [4]. Drought stress occurs due to soil surface evaporation and plant transpiration imbalance, followed by low soil moisture content [5]. Meanwhile, salinity stress occurs due to the accumulation of Na+ and Cl− ions. Excessive Na+ and Cl− ions in saline soils are toxic to plants, interfering with the absorption of other essential ions [6].

Drought and salinity stress cause similar symptoms where plants are unable to absorb water, triggering the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [7]. Plant responses to stress encourage ROS accumulation as a signaling molecule to activate stress tolerance mechanisms. However, the overproduction of ROS under extreme conditions may cause oxidative damage in plants [8]. Plant tolerance mechanisms to the overproduction of ROS generate various enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant compounds to create a cellular balance. The main enzymatic components of the defense system are superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and peroxidase (POD) [9,10]. The conversion of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) into water and oxygen is carried out by CAT, POD, and APX with the involvement of the ascorbate/glutathione (ASA/GSH) cycle. The conversion of H2O2 by APX occurs in the ASA/GSH cycle using ascorbic acid as the electron donor. This reaction produces dehydroascorbic acid (DHA), which is then reduced to ASA by glutathione (GSH). This mechanism maintains a dynamic balance between ASA/GSH [11]. Meanwhile, CAT is an enzyme that directly decomposes H2O2 into water (H2O) and oxygen (O2). Compared to APX, CAT is generally more effective in converting high concentrations of H2O2 [12]. Different from CAT, POD can utilize a broad range of electron donors, including ascorbic acid, phenolic compounds, and other reducing agents. This broad substrate specificity allows POD to play an important role in multiple cellular processes, including lignin biosynthesis, cell wall metabolism, and the regulation of ROS levels [13]. SOD, CAT, APX, and POD are referred to as antioxidant enzymes and are regulated in higher plants to maintain cell homeostasis and several environmental stimuli, including drought and salinity stresses [14]. Modulating the expression of these enzymes is also explicitly encoded by genes in rice (Oryza sativa): OsSOD, OsCAT, OsAPX, and OsPOD [9].

The defense mechanisms against ROS enzymatically may occur differentially, depending on the stress type, growth stage, stress duration, and plant variety [15]. The plant growth stage has different characteristics in stress response. Unpredictable environmental changes cause different responses in the stress resistance system, including recurrent stress in one life cycle [16]. Recurrent stress in plants develops a stress memory response, increasing the plant tolerance to environmental changes [17].

Plant responses during recovery also need further investigation, relating to plant adaptation to extremely uncertain environmental changes [18]. Differences in stress and recovery responses are essential factors to understand the mechanisms of black glutinous rice’s resistance to environmental changes. The response of black glutinous rice to oxidative stress has never been studied. Considering the potential of black glutinous rice cultivation to meet health needs, this study was performed to determine the defense response of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses, the application of stress in different plant growth stages, and the recovery strategy of black glutinous rice to normal conditions when the stress was removed. This study presents the biochemical marker analyses of specific antioxidant enzymes (CAT, APX, and POD), ROS accumulation (H2O2 and malondialdehyde [MDA]), and gene expressions of specific antioxidant genes (OsCAT, OsAPX, OsPOD) under drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials and experimental conditions

This study was performed in the Agrotechnopark Jubung, UPA Waste Management, and the Integrated Laboratory University of Jember, East Java, Indonesia. The seeds were local black glutinous rice provided by the UPA Laboratory, University of Jember. Homogeneous and healthy seeds were used as the plant material and grown under the same conditions. The seeds were soaked in water for 24 h and sown for 20 days (vegetative stage). Then, the seedlings were transferred to pots containing field soil with pH and nutrients adjusted according to the technical recommendations for rice crops. Pots were irrigated daily until the maximum capacity (water saturation) and maintained under greenhouse conditions.

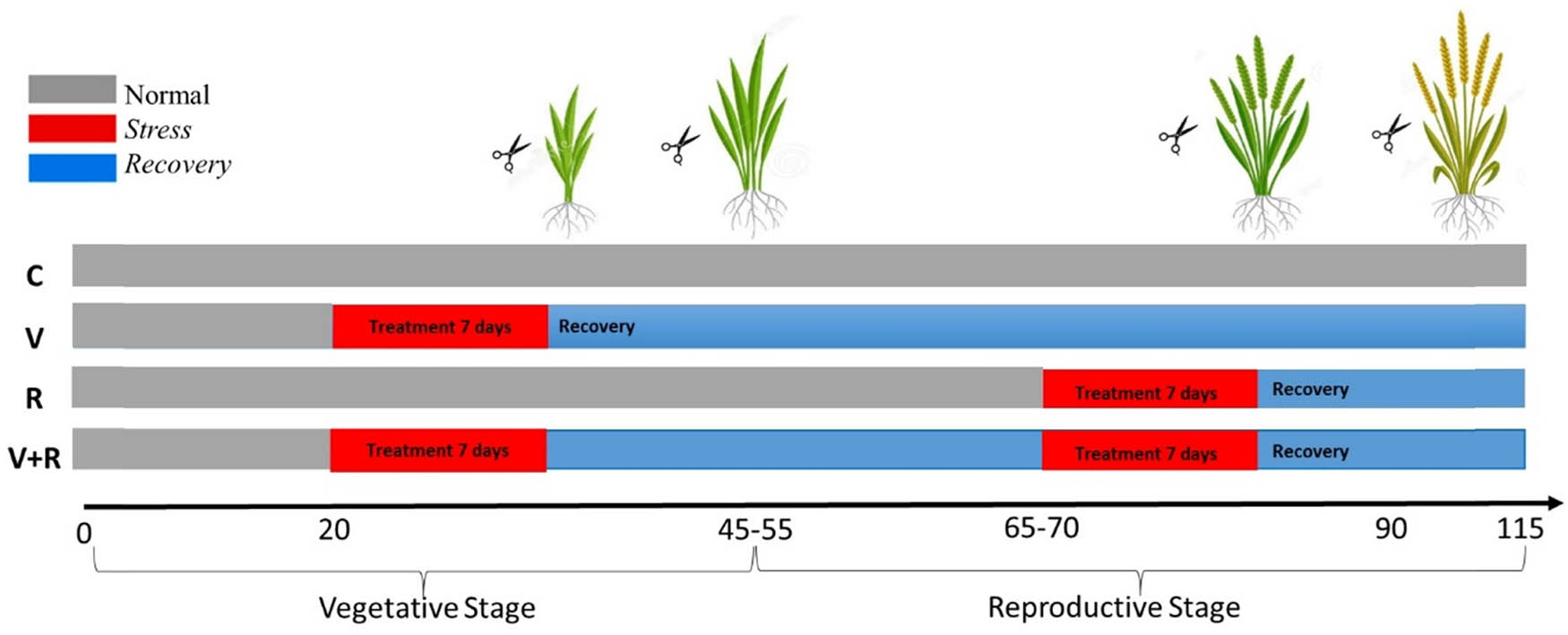

The crops were subjected to two different abiotic stresses (drought and salinity) separately. The experiments consisted of four treatments with different abiotic stresses (drought/salinity) (Figure 1). The drought and salinity stress were artificially induced by polyethylene glycol 6000 (PEG-600) and NaCl. The concentrations of PEG and NaCl given were adjusted to natural stress in field conditions, 10% PEG and 80 mM NaCl.

Experimental design for drought stress treatment in 10% PEG and salinity stress treatment in 80 mM NaCl. The scissors indicate the points at which the leaves were sampled for further analyses.

At the V5 vegetative stage, plants were divided into two groups. The first group was grown under well-watered (normal) conditions (C and R), whereas the second group (V and V+R) was treated with 10% PEG or 80 mM NaCl for 7 days. After the plants were stressed, the pots were fully rehydrated and kept well-watered until subsequent exposure to stress in the reproductive stage. This trim lasted for 40 days and reached the reproductive stage. In the reproductive stage before flowering (R1–R2), plants were subjected to 10% PEG or 80 mM NaCl in the second group plants (R and V+R) for 7 days; meanwhile, the other group plants (C and V) were kept well-watered. The periods chosen for drought or salinity stress (V5 and R1–R2) were those in which rice was highly sensitive to abiotic stresses.

The experimental design was completely randomized in a 2 × 4 factorial scheme, with two types of abiotic stresses (drought/salinity) and four experimental conditions described above. Plant samplings (harvest) for further analyses were carried out in two instants, at the end of the stress phase and after 7 days of recovery in every growth stage (Figure 1). Each treatment consisted of three pots (replicates) containing three plants per pot (experimental unit).

2.2 Morphological parameters

Morphological parameters, including plant height, number of tillers, and number of leaves, were measured to determine the growth response of black glutinous rice to abiotic stress (drought and salinity) treatment and recovery phase. These parameters were recorded every 7 days after the exposure to and recovery phase of treatment.

2.3 Determination of H2O2 and MDA contents

The H2O2 content was determined based on a previous study [19]. About 0.5 g of fresh leaves were homogenized in 5 mL of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. The absorbance was measured at 390 nm. The H2O2 content was calculated in µmol g−1 FW units.

MDA was carried out based on a previous study [20]. Approximately 0.2 g of fresh leaves were homogenized in 5 mL of 0.1% TCA and 0.5% thiobarbituric acid (TBA). The mixture was then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant (1 mL) was mixed with 4 mL of 20% TCA and 0.5% TBA. The mixture solution was incubated using a dry block at 95°C for 30 min and then immediately moved to cold conditions. Measurements were performed at wavelengths of 532 and 600 nm. The MDA content was calculated using a coefficient of 155 mM−1 cm−1. The absorbance results were calculated in µmol g−1 FW units.

2.4 Activity of antioxidant enzymes: CAT, APX, POD

The enzyme extract was prepared by taking 0.1 g of fresh leaves and then ground using liquid nitrogen. The sample was homogenized with an extraction buffer of 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7), 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 5 mM MgCl2. The solution was centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was used for further enzymatic analyses (APX, CAT, and POD).

CAT activity was assessed based on the method reported in Hadwan and Abed [21]; the enzyme sample was incubated in a 1 mL substrate containing 65 mmol mL−1 H2O2 in 60 mmol L−1 sodium-potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37°C for 3 min, then the reaction was stopped using ammonium molybdate. The reaction was performed in four test tubes. These tubes include a test tube containing the supernatant of the sample, substrate, and molybdate; a control test tube containing the supernatant of the sample, distilled water, and molybdate; a standard test tube containing distilled water, substrate, and molybdate; and a blank test tube containing distilled water and molybdate. This method was based on the reaction of undecomposed H2O2 with ammonium molybdate to produce a yellowish color with an absorbance measurement at 374 nm. The following equation was used to determine CAT activity:

where t is the time, S° is the absorbance of the standard tube, S is the absorbance of the test tube, M is the absorbance of control test (correction factor), V t is the total volume of reagents in the test tube, and V s is the volume of sample.

APX activity was determined as described in the previous study [22]. About 50 µL of supernatant was added with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7), 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 0.2 mM H2O2 at twice the volume of the supernatant. After incubation for 3 min, the reaction was initiated by adding H2O2. The enzyme activity was determined by measuring the decreased absorbance level at 290 nm due to AsA oxidation over a few minutes. The APX activity was calculated using the extinction coefficient of 2.8 mM−1 cm−1, and the activity was expressed as the number of moles of ascorbate oxidized per min per mg protein [22].

Determination of POD activity was carried out based on a modified method of Krishnegowda and Lohith [23] by adding 4 mg mL−1 4-aminoantipyrine, 50 mg mL−1 phenol buffer, 0.1 M phosphate buffer, and 0.1 mL 30% H2O2, followed by incubation for 10 min at 37°C. The reaction was measured at 2 and 5 min at 500 nm wavelength and expressed as mU/mg proteins. POD activity was determined by the following equation:

where 12.88 refers to the millimolar extinction coefficient of the quinoneimine dye, 3 the reaction time, ½ the factor based on the fact that two molecules of H2O2 form one molecule of quinoneimine dye, 3.2 the final volume of the reaction mixture, 0.1 the volume of enzyme solution, Dm the dilution multiple of enzyme solution, and 0.693 the exchange coefficient.

2.5 Expression analysis of antioxidant genes – CAT, APX, and POD

The leaf sample (0.1 g) was ground in liquid nitrogen until the powdery texture was achieved, which was then homogenized in 1 mL AccuZol™, a total RNA isolation reagent. Then, 200 µL of chloroform was added to the solution, shaken vigorously for 15 s, and incubated on ice for 5 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was added with an equal volume of isopropyl alcohol, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and 80% ethanol was added to the pellet and re-centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The pellet was collected and then dissolved in RNAase-free water. The RNA concentrations were measured from absorbance at 260 and 280 nm .

Approximately 1 µg of RNA was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with the AccuPower® CycleScript™ RT Premix (dT20) solution reagent kit. Then, DEPC-DW was added up to 20 µL. cDNA synthesis was carried out on a PCR machine with the following reaction conditions: primer annealing at 15–25°C for 30 s, cDNA synthesis at 42–45°C for 4 min, followed by a second melting step at 55°C for 30 s for 12 cycles. The reaction was then incubated at 95°C for 5 min. The cDNA product was then amplified using PCR under the following conditions: 95°C for 5 min, 95°C for 30 s, 48.9–52.5°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min for 30 cycles, and 72°C for 5 min as the final elongation. Primers for antioxidant gene expression are listed in Table 1.

Primer sequences for antioxidant gene expression analysis

| Gene | Primer sequence | Accession number | Molecular weight (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OsAPX | F: GCGAAATACTCCTACGGAAAGA | AK100016.1 | 309 | [18] |

| R: ATTCACATGCCCATCCTTTTAC | ||||

| OsCATA | F: GAAGATTGCGAATAGGCTCAAC | D29966.1 | 305 | [18] |

| R: GTGGCATTAATACGCCAGTACA | ||||

| OsPOD | F: GGGTGCGTTCCCTAATGTCA | XM_015773716.1 | 250 | [19] |

| R: GAAGTTACCCAGGTCGGTGG | ||||

| Actin | F: TCCATCTTGGCATCTCTCAG | X16280.1 | 335 | [19] |

| R: GTACCCGCATCAGGCATCTG |

The PCR products were subsequently subjected to electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel and then run at 80 V for 50 min. A 100 bp DNA ladder (PROMEGA) was used as the molecular weight marker, with a 3 μL load. The electrophoresis results were then visualized using a gel documentation system and quantified using ImageJ software as relative gene expression.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All treatments were arranged in a completely randomized design with three replications. Data expressed as mean (n = 3) ± standard deviation (SD) were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), then continued with Duncan’s multiple range tests at p < 0.05 if the values presented a statistically significant difference.

3 Results

3.1 Morphological parameters

Morphological characteristics were observed to determine the effects of drought and salinity stresses on the black glutinous rice. Table 2 presents that stress plants in the vegetative stage tend to have lower height growth than the controls. Similar results were also observed in plants under recurrent stress (V+R), whereas the stressed plants’ height was relatively lower than the control plants. In contrast to the reproductive stage, stressed plants in this stage tend to be taller than control plants. Morphological characteristics including the number of tillers and leaves were also observed. The vegetative, reproductive, and recurrent stress (V+R) stages decrease the number of tillers and leaves in plants when exposed to drought or salinity stresses.

Effect of drought and salinity stresses on morphological characteristics of black glutinous rice

| Stage of stress | Types of stresses | Plant height (cm) | Number of tillers | Number of leaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetative | Control | 67.20 ± 0.02cA | 3.00 ± 0.03cA | 12.00 ± 0.06cA |

| 10% PEG | 40.50 ± 0.03cC | 2.00 ± 0.06cB | 6.00 ± 0.03cC | |

| 80 mM NaCl | 56.30 ± 0.08bB | 3.00 ± 0.04bA | 8.00 ± 0.06bB | |

| Reproductive | Control | 122.30 ± 0.04aC | 22.00 ± 0.05aA | 88.00 ± 0.01aA |

| 10% PEG | 134.10 ± 0.01aB | 19.00 ± 0.07aB | 69.00 ± 0.04aB | |

| 80 mM NaCl | 152.10 ± 0.06bB | 15.00 ± 0.06aC | 62.00 ± 0.03aC | |

| Vegetative + reproductive | Control | 110.00 ± 0.03bA | 8.00 ± 0.05bA | 32.00 ± 0.02bA |

| 10% PEG | 102.30 ± 0.04bC | 5.00 ± 0.03bC | 21.00 ± 0.03bC | |

| 80 mM NaCl | 110.10 ± 0.06cB | 7.00 ± 0.06cB | 25.00 ± 0.03cB |

Note: Lowercase letters compare the simple effects of plant life-stage factors at the same stress level. Capital letters compare the simple effects of stress factors on the same life stage. Different letters at the same level indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

The effects of recovery from drought and salinity stresses were also observed in this study (Table 3). The data indicate that recovered plants experienced an increase in the plant height, number of tillers, and number of leaves. The morphological changes in the recovery phase were recorded on the seventh day of recovery phase in every growth stage treatment. The data continued to be quantified for the relative growth rate (%) of the stress plant to recovery. The relative growth rate (%) varied among plants in each treatment and growth stage. The relative growth rate (%) was measured from the difference between the final growth value (recovery) and the initial growth value (stress) and then divided by the initial growth value (stress).

Effect of recovery from drought and salinity stresses on morphological characteristics of black glutinous rice

| Stage of stress | Types of stresses | Plant height (cm) | Number of tillers | Number of leaves |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetative | Control | 116.20 ± 0.06cA | 6.00 ± 0.01cA | 26.00 ± 0.01cA |

| 10% PEG | 101.30 ± 0.01cB | 3.00 ± 0.02cC | 10.00 ± 0.02cC | |

| 80 mM NaCl | 88.80 ± 0.42bC | 4.00 ± 0.82cB | 12.00 ± 3.74cB | |

| Reproductive | Control | 144.50 ± 0.05aB | 25.00 ± 0.06aA | 68.00 ± 0.01aA |

| 10% PEG | 141.00 ± 0.02aC | 15.00 ± 0.05aB | 63.00 ± 0.02aB | |

| 80 mM NaCl | 152.18 ± 0.92aA | 14.00 ± 2.58aC | 57.00 ± 1.63aC | |

| Vegetative + reproductive | Control | 121.40 ± 0.02bA | 9.00 ± 0.05bB | 37.00 ± 0.01bB |

| 10% PEG | 112.60 ± 0.02bC | 7.00 ± 0.06bC | 26.00 ± 0.01bC | |

| 80 mM NaCl | 115.08 ± 0.08cB | 10.00 ± 2.58bA | 41.00 ± 0.03bA |

Note: Lowercase letters compare the simple effects of plant life-stage factors at the same stress level. Capital letters compare the simple effects of stress factors on the same life stage. Different letters at the same level indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

The most significant relative plant height growth rate was found on the recovered vegetative plants from drought stress (150%), followed by recovered vegetative plants from salinity stress (58%). The vegetative stage provided the highest relative growth rate after recovery compared to other growth stages (R and V+R). The reproductive stage provided the lowest relative height growth rate, and the height growth rates of control, drought, and salinity treatments, which were 18, 5, and 0%, respectively. Meanwhile, the recurrent stress stages (V+R) slightly increased the relative height growth rate by 9 and 5% at drought and salinity stresses, respectively.

The relative growth rate in the number of tillers was also observed from stress to recovery (Figure 2). The vegetative stage provided a lower growth rate compared to control after stress exposure, 50 and 33% at drought and salinity stress, respectively. Different results were observed in the recurrent stress stage (V+R), where plants were given the highest number of tillers compared to other stages after drought and salinity exposure, 40 and 43%, respectively. Meanwhile, the control plants in the recurrent stress stage (V+R) showed a slightly increased relative growth rate of 13%. The reproductive stage showed the lowest relative growth rate in the number of tillers, either in drought 27% or salinity 7% stress, compared to the vegetative and recurrent stages (V+R).

Relative growth rate of black glutinous rice in stress in the recovery phase. Note: Lowercase letters compare the simple effects of plant life-stage factors at the same stress level. Capital letters compare the simple effects of stress factors on the same life stage. Different letters at the same level indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

The relative growth rate in the number of leaves was also observed as a plant growth parameter from the stress to the recovery phase. The vegetative stage provided the highest growth rate in the number of leaves on all stress exposure: control, drought, and salinity (117, 67, and 56%, respectively). The recurrent stress stage (V+R) showed a growth rate in the number of leaves at 16, 24, and 64% at the control, drought, and salinity treatments. In the reproductive stage, plants tended to have no growth (0%) elevation in the number of leaves after recovery. Recovered plants from drought and salinity stresses had fewer leaves.

3.2 H2O2 and MDA contents

Abiotic stress (drought and salinity) causes a higher ROS accumulation than the unstressed condition (control). As shown in Figure 3, stress exposure with 10% PEG (drought) and 80 mM NaCl (salinity) resulted in a higher H2O2 content than the control in the vegetative (V), reproductive (R), and combination (V+R) stages. The highest accumulation of H2O2 occurred when plants were exposed to drought and salinity stresses in the reproductive stage at 63.9 and 69.8 µmol g−1 FW, respectively.

ROS (H2O2 and MDA) contents in black glutinous rice on drought and salinity exposure and in the recovery phase. Note: Lowercase letters compare the simple effects of plant life-stage factors at the same stress level. Capital letters compare the simple effects of stress factors on the same life stage. Different letters at the same level indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

The highest H2O2 accumulation was found in black glutinous rice plants exposed to recurrent stresses (V+R) from drought and salinity stresses at 55.9 and 47.2 µmol g−1 FW, respectively. Providing treatment at different plant life stages with the same stress type resulted in a significant difference. Meanwhile, different stress exposures applied to the same growth stage provided insignificantly different results. This can be interpreted as the H2O2 accumulation was influenced by the plant growth stage when exposed to stress. Fundamental differences occurred when plants were stressed during the reproductive stage. The reproductive stage had significantly different effects on H2O2 accumulation, at 6.3 and 6.9% for drought and salinity stresses, respectively. Recurrent stress (V+R) increased the H2O2 accumulation by 6.7 and 5.5% under drought and salinity stresses, respectively.

Changes in H2O2 content were also observed when the plants were in the recovery phase. The recovery phase involved water irrigation that could decrease the H2O2 content. The most significant decrease in the recovery phase occurred under recurrent stress (V+R) at 0.2% with 10% PEG stress. At different growth stages, recovery treatment for the same stress type showed significantly different results. In contrast, the results are insignificantly different at the same life stage and with different types of stresses. This condition proves that the decreased H2O2 accumulation in the recovery phase is greatly influenced by the plant’s growth stage, whereas the recovery phase in the reproductive stage significantly reduced the H2O2 content.

MDA is the final product of lipid peroxidase, which is an indicator of oxidative stress in plants [19]. Changes in MDA accumulation in black glutinous rice are shown in Figure 3. The accumulated MDA content of black glutinous rice plants in this study was lower than the H2O2 content but only in 0–9 µmol g−1 FW range. MDA accumulation after salinity stress obtained significantly different results in the reproductive stage. In contrast, other treatments showed insignificantly different results for the same stress type with different growth stages.

The highest MDA content was found in black glutinous rice under 10% PEG stress in the reproductive stage (1.02%), followed by the same stress in the vegetative stage (0.92%). The MDA content was low in the recurrent stress (V+R). Changes in MDA content also occurred in the recovery phase, and a decreased MDA content occurred after the stress was removed. The most significant decrease occurred in the recovery phase of 10% PEG in the vegetative stage at 0.58%. In comparison, the lowest decrease occurred in the recovery phase of 10% PEG in the reproductive stage.

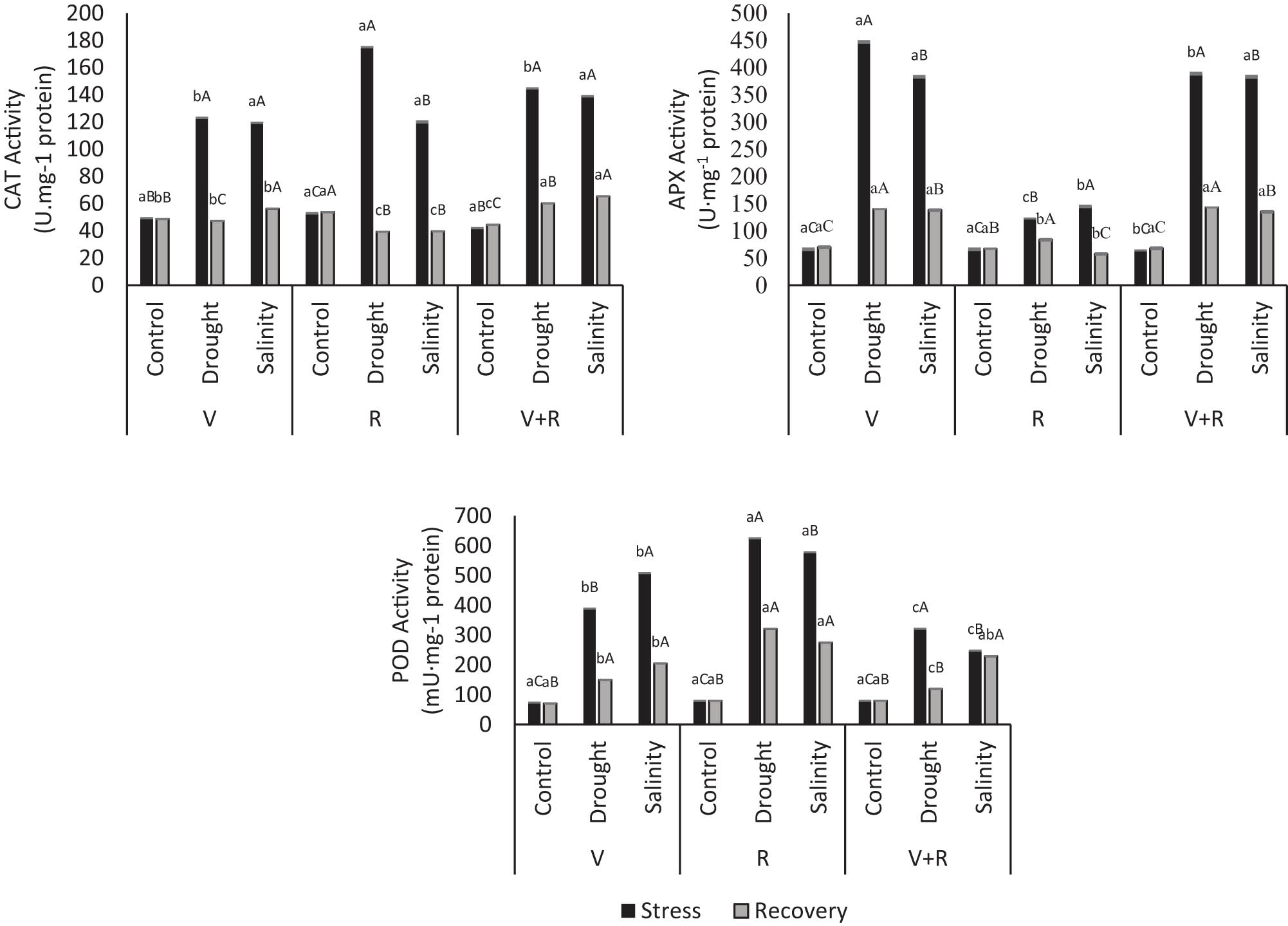

3.3 Activity of antioxidant enzymes: SOD, CAT, APX, and POD

The highest CAT activity was obtained in black glutinous rice with 10% PEG stress in the reproductive stage at 174.98 U mg−1 protein. Drought stress (10% PEG) obtained a higher CAT activity than salinity stress in all treatments at different growth stages. Drought stress showed significantly different results in the reproductive stage compared to other growth stages.

This condition indicates that drought stress in the reproductive CAT activity decreased in the recovery phase, approaching normal conditions in all growth stages and types of stresses, within an average value of 50.15 U mg−1 protein. This condition means that CAT activity is influenced by environmental stress and activated to defend plants from non-optimal environmental conditions.

APX is an antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of H2O2 to H2O with ASA assistance. The APX activity in black glutinous rice is presented in Figure 4, which presented different results from the CAT activity. The highest APX activity was achieved in the vegetative stage exposed to drought stress (5.8 %), followed by the recurrent stress treatment stage (V+R) at 5.1%. Increased APX activity under salinity stress was 4.8 and 5% in the vegetative and recurrent stages (V+R), respectively.

CAT, APX, and POD activities in black glutinous rice on drought and salinity exposure and in the recovery phase. Note: Lowercase letters compare the simple effects of plant life-stage factors at the same stress level. Capital letters compare the simple effects of stress factors on the same life stage. Different letters at the same level indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

APX activity decreased to near-normal conditions with each type of stress during the recovery phase. The most significant decrease in APX activity occurred in the vegetative stage under drought and salinity stresses at 2.2 and 1.8%, respectively. APX activity in the recovery phase after drought and salinity stresses was nearly similar to the unstressed plants (control), as there was no significant increase of APX activity in the reproductive stage.

When exposed to drought or salinity stresses, POD activity was beyond normal conditions during all growth stages. However, the POD activity was lower than that of other antioxidant enzymes, as evidenced by the results obtained in mU mg−1 protein. The most significant increase in POD activity was observed when stressed plants were found in the reproductive stage. In the reproductive stage, POD obtained the highest activity after exposed to drought and salinity stresses at 624.42 and 578.50 mU mg−1 protein, respectively. Meanwhile, the recovery stage affected the POD activity, decreasing when recovery occurred. The most significant decrease in POD activity occurred in the recovery phase, with recurrent drought stress (V+R) at 1.69%. In the recovery stage of recurrent salinity stress (V+R), POD activity decreased by 0.08%.

3.4 Expression analysis of antioxidant genes: CAT, APX, and POD

Molecular analysis was performed to determine the antioxidant gene regulation when plants were exposed to stress and survived during the recovery phase. The regulation of antioxidant gene expression (OsCATA, OsAPX, and OsPOD) is shown in Figure 5. The regulation of the molecular level differs from its biochemical level. In general, the regulation of antioxidant gene expression during recovery is higher than the regulation during stress. In contrast, antioxidant activity is higher during stress than during the recovery phase at the biochemical level.

(a) Gene expression of CAT, APX, and POD electrophoresis bands under stress and in the recovery phase. Note: (1) vegetative control, (2) vegetative 10% PEG, (3) vegetative 80 mM NaCl, (4) reproductive control, (5) reproductive 10% PEG, (6) reproductive 80 mM NaCl, (7) vegetative + reproductive control, (8) vegetative + reproductive 10% PEG, and (9) vegetative + reproductive 80 mM NaCl. (b) Relative gene expressions of CAT, APX, and POD under stress and in the recovery phase. Note: Lowercase letters compare the simple effects of plant life-stage factors at the same stress level. Capital letters compare the simple effects of stress factors on the same life stage. Different letters at the same level indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05).

The OsCATA expression under stress and recovery conditions was visually observed in DNA band electrophoresis, and the relative gene expression was also provided. The highest OsCAT expression occurred when plants were exposed to drought stress in the reproductive stage. In contrast, other growth stages (V and V+R) had no significant changes in OsCATA gene expression under stress conditions. The recovery phase showed equal OsCAT expression in the reproductive and recurrent stress stages after drought and salinity stress exposure.

The highest OsAPX expression was found in plants that were exposed to salinity and drought stresses in the reproductive stage. Low levels of APX expression were under control in all growth stages. The recovery stage showed OsAPX expression in the reproductive and recurrent stress stages. However, OsAPX expression was absent in the recovery phase from drought stress under (V+R) conditions.

OsPOD expression was observed under stress and in the recovery phase in black glutinous rice. The highest OsPOD expression was observed in plants that were exposed to recurrent salinity and drought stresses in the reproductive stage. In contrast, the low expression of OsPOD was observed in the vegetative stage under control and drought stresses. Black glutinous rice that entered the recovery phase after stress exposure expressed OsPOD at almost the same level under all control and recovery phases in all growth stages. However, OsPOD expression was lower in the reproductive stage than in other growth stages (V and V+R).

4 Discussion

4.1 Morphological parameters

Drought and salinity stresses in the reproductive stage influenced the higher plant height among control plants. The increase of the plant height in this stage was a plant adaptation to stress by the drought tolerance mechanism. This mechanism included cellular adjustments, morphological adaptation, ROS regulation, molecular signaling, and resistance-related gene expressions [24]. Increased plant height under stress in the reproductive stage is related to increased H2O2 accumulation. Accumulation of H2O2 could increase cell division in the vegetative stage and modulate cell expansion in the reproductive stage through signal transmission [25]. According to previous study [26], H2O2 may act as a signal molecule under biotic or abiotic stress. H2O2 may increase PME (pectin methylesterase) activity in cell walls, thereby increasing the induction of pectin synthesis for cell expansion. Cell expansion occurs to balance the integrity of the cell wall in an attempt to survive extreme environmental changes. The regulation of cell expansion in specific organs may occur when plants are stressed but is often achieved at the expense of other growth organs of the plant or by reducing plant biomass [27].

The recovery process is crucial as it determines whether a plant adapts to environmental stress by resuming growth [18]. Plant growth in this study was evaluated from the relative growth rate of stressed plants in the recovery phase. The results showed that the vegetative stage obtained the highest significant growth rate in plant height among the other growth stages. This condition means that the vegetative stage has better morphological growth restoration capabilities for plant height. Plants in various growth stages have different recovery capabilities due to different responses and vulnerabilities to environmental stress [28]. The vegetative stage has good morphology recovery capabilities due to its composition of relatively young plant cells. Therefore, vegetative plants can easily resume their growth with more massive cell differentiation and elongation than reproductive plants [29].

The relative growth rate in the number of tillers and leaves differed in each growth stage. The vegetative stage obtained the lowest relative growth rate in the number of tillers compared to other growth stages. In the vegetative phase, the plant response is greater in plant height and number of leaves. The reproductive stage had the lowest relative growth rate in height growth, number of tillers, and number of leaves. This condition indicates that the reproductive stage is more vulnerable to stress, based on a lower morphological recovery response than other growth stages [30]. The reproductive stage tends to have a slower recovery than the vegetative stage because it has more energy reserves in the form of carbohydrates stored in the roots and other tissues, allowing them to respond more effectively to stress promoting recovery. Meanwhile, in the reproductive stage, the plant uses much of its stored energy for reproduction, leaving fewer reserves available for recovery [31]. The recurrent stress stage (V+R) tended to recover better than the reproductive stage, which was caused by the plant’s ability to survive through memory metabolic processes, affecting the plant's response to the new stress exposure potential [17].

4.2 H2O2 and MDA contents

Drought and salinity stresses promote ROS accumulation in plant cells. H2O2 is one of the most stable types of ROS, and it quickly passes through membranes to transmit signals between cells [32]. Accumulation of H2O2 at high levels may cause cell damage [33]. The reproductive stage accumulated the highest amount of H2O2 when plants were exposed to stress. This shows that the reproductive stage is sensitive to environmental stress, based on H2O2 as a stress biomarker [34]. Water and nutrition availability are necessary in the flowering (reproductive) stage [15]. A decrease in H2O2 content occurred when stress was relieved (recovery phase). Accumulation of H2O2 is a biomarker for stressed plants. In contrast, the degression of H2O2 indicates that the stress was removed [35]. The vegetative stage showed the lowest H2O2 content compared to other growth stages, suggesting that the vegetative stage has good capacity for recovery.

MDA is a secondary lipid peroxidation product that indicates cell damage levels due to stress. Plants with a low MDA content present a tolerance to stress [36]. Lipid peroxidation is formed by taking electrons from unsaturated fats (PUFA), which contain reactive hydrogen atoms in plant cells. This mechanism indicates plant cell oxidative damage [37]. The MDA content in cells can be detected using TBA, a reactive compound to MDA, marked red as the end product of the reaction. The redder the color of the mixture produced, the greater the MDA accumulation [38]. High amounts of MDA accumulation indicate the magnitude of cellular damage due to abiotic stress [37,38].

In the present study, the highest MDA accumulation was obtained from the reproductive plants exposed to drought stress, followed by vegetative plants under drought stress. Drought stress using 10% PEG is more reactive in oxidizing lipids [39]. PEG was administered to simulate drought stress, which could accumulate in cell membranes and damage lipids’ double bonds quicker than the salt. The reproductive stage is a critical period for plants in terms of their water needs. In this stage, lack of water will affect the formation of panicles and rice grains, the main factors for yield production [15]. Furthermore, the vegetative stage also accumulates high amounts of MDA, a critical period for high amounts of water to form subsequent plant organs, such as leaves and tillers [40]. On the other hand, the lowest MDA accumulation was obtained in the recurrent stress stage (V+R), both in drought and salinity stress, which showed no MDA elevation under drought and salinity stress compared to the control plants. This result suggests a memory effect from the first drought/salinity experience. Plants experiencing recurrent drought or salinity stress would show more active mechanisms of stress tolerance [17]. According to Fleta-Soriano and Munné-Bosch [41], plant responses to recurrent stress differ from those in single-stage stress. Plants experiencing recurrent stress improve inducible responses to stress, a process known as “primability” to subsequent stress, in which a first stress experience may prime the plant for an improved response to upcoming new potential stressful events [16].

Decreased MDA content occurred when the stress was relieved (recovery phase). The lowest MDA content occurred in vegetative plants under drought stress. This indicates that vegetative plants can recover faster than reproductive plants, and MDA accumulation remained high even after stress removal. Stress removal (recovery) explains the plant’s tolerance to stress by its ability to regrowth [18]. In this condition, the reproductive stage is highly susceptible to stress. In contrast, the vegetative stage is relatively more tolerant to stress due to good recovery ability.

4.3 CAT, APX, and POD activities

The antioxidant activity induced by PEG and NaCl was evaluated, and this study reported the physiological changes in rice plants. A study by Bhattacharjee et al. [42] found enzyme activity higher at 10% PEG than control. High concentrations of PEG can cause significant decreases in morphology, and a study by Sagar et al. [43] at 20% PEG resulted in 0% growth in plants, and they even died immediately when stress was applied. Therefore, 10% PEG was chosen as the most suitable concentration to create artificial drought stress in this study. Also, for salinity stress, 80 mM NaCl (equal to 8 dS m−1) was chosen as the most suitable concentration to evaluate the morphological changes and antioxidant enzyme activity in rice, as declined enzyme activity with more increased NaCl concentrations and prolonged salt stress were found [44].

CAT is an enzymatic antioxidant that directly catalyzes H2O2 into H2O and O2 without requiring a substrate. The results showed that CAT activity was higher in the drought-exposed plants in the reproductive stage. The high CAT activity is related to the high accumulation of H2O2. Thus, the higher the H2O2 accumulation, the more the CAT activity in breaking down H2O2 [45]. CAT activity increased when stress was present in every growth stage, and it decreased to normal conditions when the stress was removed (recovery). Thus, the upregulation of CAT is a survival condition against oxidative stress in plants.

APX catalyzes H2O2 to H2O using ASA as a specific electron donor. The results showed that APX activity increased when plants were exposed to stress, with the highest level obtained from the vegetative stage under drought stress, followed by the recurrent stress stage (V+R). Salinity stress also increased the APX activity when plants were in vegetative and recurrent (V+R) stages. The reproductive stage showed no elevation level of APX activity. This may cause the CAT to carry out the H2O2 breakdown, so the H2O2 breakdown in the vegetative and recurrent (V+R) stages was maximized by APX. APX activity occurred in the Asa-GSH cycle, known as the Asada-Haliwell cycle, the primary antioxidant defense pathway in detoxifying H2O2. Non-enzymatic antioxidants such as AsA and GSH were also present [6]. AsA and GSH are the most abundant soluble antioxidants in higher plants that play an important role as electron donors and capture ROS directly through the AsA-GSH cycle [6]. The abundance of AsA and GSH in plants was considered a reason for the high activity of APX compared to CAT.

APX activity decreased in the recovery phase, indicating that APX is very responsive to environmental changes. However, APX activity was still relatively high during the recovery treatment from drought and salinity stresses in the vegetative and recurrent (V+R) stages despite the decrease in their activity. APX activity during recovery was decreased than CAT activity, which could be close to the normal level when stress was removed. This was suggested to be due to high APX activity when stress occurred, and their regulation increased by twofold above control. Therefore, the decreased APX activity in the recovery phase of 7 days has not yet reached the normal level. The rate at which an enzyme's activity is upregulated or downregulated may vary and is not universal due to the differences in cultivar, organ, plant growth, and growing conditions [46].

The POD activity increased when plants were under drought and salinity stresses. In reproductive plants, the POD reached the highest activity, followed by the vegetative plants under drought and salinity stresses. This condition presents that the reproductive and vegetative stages are the most reactive stages where POD activity changed. The vegetative and reproductive stages are highly susceptible to water and nutritional needs [29], so if the environment is suboptimal, plants will regulate their defense system [34]. However, POD activity is lower than other antioxidant enzymes (CAT and APX), likely due to H2O2 detoxification being maximized by CAT during stress.

Recovery has an impact on decreasing the POD activity as well as on the activity of other antioxidant enzymes. This condition is also influenced by the fact that ROS no longer accumulates in high amounts, so plants have no need to regulate enzymatic antioxidants and maintain the cellular balance. POD activity is still visible even at low levels in non-stressed conditions, which may play a role in various plant physiological processes, such as cell wall metabolism [47], auxin metabolism [48], and lignification [49].

4.4 Relative expressions of CAT, APX, and POD

The expression of antioxidant-related genes was observed visually through the electrophoresis bands, whereas the band’s thickness indicates the target gene’s expression level [50]. The DNA bands were then processed quantitatively using ImageJ software as a relative gene expression. Relative gene expression was based on the ratio of target versus housekeeping genes [51], in which actin was used as a housekeeping gene in this study.

The target genes related to antioxidants in this study were OsCAT, OsAPX, and OsPOD, which provided the highest relative gene expression levels under drought and salinity stresses in the reproductive stage. The upregulation of OsCATA and OsPOD was associated with its protein level regulation [41], where CAT and POD activities were increased under drought and salinity stresses in the reproductive stage. This condition shows that the increased transcription levels of OsCATA and OsPOD encoded the CAT and POD proteins in the reproductive plants, a sensitive growth stage to environmental stress [42]. CAT is found in peroxisomes and is indispensable for decomposing H2O2 during stress [52]. This agreed with the results in H2O2 accumulation, which was higher during stress in the reproductive stage. The upregulated OsCATA encoded CAT activity to detoxify high accumulation of H2O2 in peroxisomes turn into H2O and O2. CAT consists of a small family in rice presented by the genes OsCATA, OsCATB, and OsCATC [53]. They were in different locations and had specific functions. OsCATA is located in photosynthetic tissues, whereas OsCATB is related to vascular tissues, and the OsCATC is exhibited in seeds and reproductive tissues [54]. Under high salinity, OsCATA and OsCATC were the most responsive to saline stress [55]. The expressional level of OsCATA was also strongly enhanced in the leaves due to drought treatment in the tolerant genotype [56]. Thus, it could be stated that OsCATA is the stress-responsive member of CAT. Under drought and salinity stresses, a study by Refli and Purwestri [57] observed an increase in CAT expression, which was higher under drought stress than under salinity stress, similar to this study. This indicated that detoxification of H2O2 produced was more effective under drought than under salinity stress. Detoxification of H2O2 is also facilitated by OsPOD, which encodes POD activity. This study presents an increased expression of OsPOD under salinity and drought stresses in the reproductive stage, as it decomposes H2O2 [54]. The increase of OsPOD was lower compared to OsCATA and OsAPX in the reproductive stage. Similar findings by Mehmood et al. [58] showed that OsPOD continued to express low levels during stress, and a suggestion by Abogadallah [59] stated that POD may not be sufficient to control H2O2 levels compared to CAT and APX.

The ASA/GSH cycle, an efficient antioxidant system in the detoxification of H2O2, involves APX, MDHAR, DHAR, and GR for enzymes. The cycle maintains the proper ratio between reduced and oxidized ASA and GSH, which is useful for proper ROS scavenging in plant cells [60]. APX is the main enzyme in the ASA/GSH cycle, encoded by the transcript level of OsAPX. The increase of the expression level in OsAPX should increase its enzyme activity. However, this study presented a different result between the expression level of OsAPX and its APX activity during stress in the reproductive stage. APX activity remained low under stress and in the reproductive stage. This may suggest that OsCATA mainly facilitates the detoxification of H2O2 as it is correlated with the increased level of OsCATA and CAT activity due to stress in the reproductive stage. A study by Vighi et al. [55] reported that the increased expression of OsAPX did not affect the enzyme activity, especially in the tolerant genotype. This may be suggested by the absence of reduced ascorbate in the activation of APX [61]. This indicates that APX expression is regulated at the post-translational modification level during protein synthesis, which may result in differences between gene expression and enzyme activity [62]. Similarly, the findings of Nounjan et al. [63] stated that the increase in transcript levels of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes did not always coincide in most cases of enzyme levels. This may result from a higher enzyme turnover of H2O2 inactivation.

Transcription levels of OsCAT, OsAPX, and OsPOD increased in stress conditions. However, increased expression of OsCAT, OsAPX, and OsPOD also occurred in the recovery phase. In the recovery phase, the expression of antioxidant-related genes was regulated at the post-transcriptional level. Post-transcriptional levels were active in small-scale responses to temporary stress and in the recovery stage to normal conditions [64]. The transcript level may be expressed in the recovery phase, as found in the study by Bian and Jiang [52], which reported the expression of CAT, APX, and POD during recovery. The antioxidant gene remains expressed in the recovery phase for several important reasons. Yeung et al. [18] suggested that the expression of APX and CAT during recovery may continue to counteract the damage caused by ROS and restore cellular balance. Similar to Mehmood et al. [58], CAT and POD help modulate the inflammatory response and prevent excessive ROS from causing additional tissue damage during recovery.

5 Conclusions

The tolerance capability of black glutinous rice to abiotic stress can be evaluated from the plant's ability to recover after the stress is removed. Stressed plants in the vegetative stage and recurrent stress (V+R) have better recovery abilities than in the reproductive stage. The regulation of black glutinous rice resistance at the protein and enzymatic levels varies among each treatment stage. Specifically, CAT and POD show high activity in the reproductive stage, while APX activity is more pronounced in the vegetative and recurrent stress stages (V+R). Additionally, regulation at the molecular level also shows different relative expression results between stress and recovery conditions. These differences occur due to gene expression factors, such as transcription, post-transcription, and post-translation, creating a unique pattern in the molecular and biochemical responses of black glutinous rice to abiotic stress. In conclusion, this work underlines the defense responses of black glutinous rice under oxidative stress in different growth and recurrent stress stages, in which this information is beneficial for broader cultivation on suboptimal lands.

Acknowledgements

This study project was supported by the University of Jember and the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education, Indonesia.

-

Funding information: This study was funded by the University of Jember and the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education, Indonesia.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. Composed the original draft: YFR and TAS. Conceptualization: TAS, YFR, OHA, and ALP. Sample collection: YFR, OHA, and ALP. Data analysis: YFR, OHA, and RR. Investigation: YFR, OHA, ALP, and RR. Supervision: TAS. Funding acquisition: TAS.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Pradipta S, Siswoyo TA, Ubaidillah M. Nutraceuticals and bioactive properties of local Java pigmented rice. Biodiversitas. 2023;24(1):571–82. 10.13057/biodiv/d240166.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Ngamdee P, Wichai U, Jiamyangyuen S. Correlation between phytochemical and mineral contents and antioxidant activity of black glutinous rice bran, and its potential chemopreventive property. Food Technol Biotechnol. 2016;54(3):282–9.10.17113/ftb.54.03.16.4346Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Chen L, Huang Y, Xu M, Cheng Z, Zheng J. Proteomic analysis reveals coordinated regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis through signal transduction and sugar metabolism in black rice leaf. Int J Mol Sci. Dec 2017;18:12. 10.3390/ijms18122722.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Batlang U, Baisakh N, Ambavaram MMR, Pereira A. Phenotypic and physiological evaluation for drought and salinity stress responses in rice. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;956:209–25. 10.1007/978-1-62703-194-3_15.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Bogati K, Walczak M. The impact of drought stress on soil microbial community, enzyme activities and plants. Agron. 2022;12(1):189. 10.3390/agronomy12010189.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Hasanuzzaman M, Fujita M. Plant responses and tolerance to salt stress: Physiological and molecular interventions. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4810. 10.3390/ijms23094810.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Sachdev S, Ansari SA, Ansari MI, Fujita M, Hasanuzzaman M. Abiotic stress and reactive oxygen species: Generation, signaling, and defense mechanisms. Antioxid. 2021;10(2):277. 10.3390/antiox10020277.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Naing AH, Kim CK. Abiotic stress-induced anthocyanins in plants: Their role in tolerance to abiotic stresses. Physiol Plant. 2021;172:1711–23. 10.1111/ppl.13373.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Shah K, Nahakpam S. Heat exposure alters the expression of SOD, POD, APX and CAT isozymes and mitigates low cadmium toxicity in seedlings of sensitive and tolerant rice cultivars. Plant Physiol Biochem. Aug 2012;57:106–13. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.05.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Sharma P, Jha AB, Dubey RS, Pessarakli M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J Bot. Apr 2012;2012:1–26. 10.1155/2012/217037.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Hasanuzzaman M, Bhuyan MHMB, Anee TI, Parvin K, Nahar K, Mahmud JA, et al. Regulation of ascorbate-glutathione pathway in mitigating oxidative damage in plants under abiotic stress. Antioxid. 2019;8(9):384. 10.3390/antiox8090384.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Anjum NA, Sharma P, Gill SS, Hasanuzzaman M, Khan EA, Kachhap K, et al. Catalase and ascorbate peroxidase—representative H2O2-detoxifying heme enzymes in plants. Environ Sci Pollut Res. Oct 2016;23(19):19002–29. 10.1007/s11356-016-7309-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Pandey VP, Awasthi M, Singh S, Tiwari S, Dwivedi UN. A comprehensive review on function and application of plant peroxidases. Biochem Anal Biochem. 2017;6(1):308. 10.4172/2161-1009.1000308.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Gupta DK, Palma JM, Corpas FJ. Antioxidants and antioxidant enzymes in higher plants. Cham: Springer; 2018. 10.1007/978-3-319-75088-0.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Yang X, Wang B, Chen L, Li P, Cao C. The different influences of drought stress at the flowering stage on rice physiological traits, grain yield, and quality. Sci Rep. Dec 2019;9(1):3742. 10.1038/s41598-019-40161-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Auler PA, Souza GM, da Silva Engela M, do Amaral MN, Rossatto T, da Silva M, et al. Stress memory of physiological, biochemical and metabolomic responses in two different rice genotypes under drought stress: The scale matters. Plant Sci. Oct 2021;311:110994. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.110994.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Auler PA, do Amaral MN, Rodrigues G, Benitez LC, da Maia LC, Souza GM, et al. Molecular responses to recurrent drought in two contrasting rice genotypes. Planta. Nov 2017;246(5):899–914. 10.1007/s00425-017-2736-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Yeung E, van Veen H, Vashisht D, Sobral Paiva AL, Hummel M, Rankenberg T, et al. A stress recovery signaling network for enhanced flooding tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. Jun 2018;115(26):E6085–94. 10.1073/pnas.1803841115.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Junglee S, Urban L, Sallanon H, Lopez-Lauri F. Optimized assay for hydrogen peroxide determination in plant tissue using potassium iodide. Am J Anal Chem. 2014;5(11):730–6. 10.4236/ajac.2014.511081.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Heath RL, Packer L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;125(1):189–98. 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Hadwan MH, Abed HN. Data supporting the spectrophotometric method for the estimation of catalase activity. Data Brief. Mar 2016;6:194–9. 10.1016/j.dib.2015.12.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Nakano Y, Asada K. Purification of ascorbate peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts; its inactivation in ascorbate-depleted medium and reactivation by monodehydroascorbate radical. Plant Cell Physiol. 1987;28(1):131–40. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a077268.Search in Google Scholar

[23] SBS, Krishnegowda A, Lohith S MK. Spectrophotometric assay based on horseradish peroxidase-catalysed hydrogen peroxide using amino antipyrine and resorcinol as chromogenic reagents for sensitive detection of peroxidase in plant extracts. GIJET. 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/375926391.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Wahab A, Abdi G, Saleem MH, Ali B, Ullah S, Shah W, et al. Plants’ physio-biochemical and phyto-hormonal responses to alleviate the adverse effects of drought stress: A comprehensive review. Plants. 2022;11(13):1620. 10.3390/plants11131620.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Siti ZI, Mohammad MK, Nashriyah M, Amru NB. Effects of hydrogen peroxide on growth, development and quality of fruits: A review. J Agron. 2015;14:331–6. 10.3923/ja.2015.331.336.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Xiong J, Yang Y, Fu G, Tao L. Novel roles of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in regulating pectin synthesis and demethylesterification in the cell wall of rice (Oryza sativa) root tips. N Phytologist. Apr 2015;206(1):118–26. 10.1111/nph.13285.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Zhang H, Zhao Y, Zhu JK. Thriving under stress: How plants balance growth and the stress response. Dev Cell. 2020;55:529–34. 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.10.012.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Pociecha E. Different physiological reactions at vegetative and generative stage of development of field bean plants exposed to flooding and undergoing recovery. J Agron Crop Sci. Jun 2013;199(3):195–9. 10.1111/jac.12009.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Moonmoon S, Islam M. Effect of drought stress at different growth stages on yield and yield components of six rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes. Fundam Appl Agric. 2017;2(3):1. 10.5455/faa.277118.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Quintao G, Ubaidillah M, Hartatik S, Khofifa RAN, Siswoyo TA. The morpho-physiological and gene expression of East Timor’s local rice plant (Oryza sativa) response to drought and salinity stress. Biodiversitas. 2023;24(8):4548–56. 10.13057/biodiv/d240858.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Kang J, Peng Y, Xu W. Crop root responses to drought stress: Molecular mechanisms, nutrient regulations, and interactions with microorganisms in the rhizosphere. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(16):9310. 10.3390/ijms23169310.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Yu Y, Wang S, Guo W, Geng M, Sun Y, Li W, et al. Hydrogen peroxide promotes tomato leaf senescence by regulating antioxidant system and hydrogen sulfide metabolism. Plants. Feb 2024;13(4):475. 10.3390/plants13040475.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Mansoor S, Ali WO, Lone JK, Manhas S, Kour N, Alam P, et al. Reactive oxygen species in plants: from source to sink. Antioxid. 2022;11(2):225. 10.3390/antiox11020225.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Oguz MC, Aycan M, Oguz E, Poyraz I, Yildiz M. Drought stress tolerance in plants: Interplay of molecular, biochemical and physiological responses in important development stages. Physiologia. Dec 2022;2(4):180–97. 10.3390/physiologia2040015.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Hasanuzzaman M, Tanveer M. Signaling and communication in plants salt and drought stress tolerance in plants: signaling networks and adaptive mechanisms. Cham: Springer; 2020. 10.1007/978-3-030-40277-8.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Ma J, Du G, Li X, Zhang C, Guo J. A major locus controlling malondialdehyde content under water stress is associated with Fusarium crown rot resistance in wheat. Mol Genet Genomics. Oct 2015;290(5):1955–62. 10.1007/s00438-015-1053-3.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Melanie M, Sergi M. Malondialdehyde: Facts and artifacts. Plant Physiol. 2019;180(3):1246–50.10.1104/pp.19.00405Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Ayala A, Muñoz MF, Argüelles S. Lipid peroxidation: Production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;360438. 10.1155/2014/360438.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Susilowati E, Sanjaya BRL, Nugraha AS, Ubaidillah M, Siswoyo TA. Revealing of free radical scavenging and angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitor potency of pigmented rice seed protein. Food Sci Technol (Braz). 2022;42:e66520. 10.1590/fst.66520.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Swain P, Raman A, Singh SP, Kumar A. Breeding drought tolerant rice for shallow rainfed ecosystem of eastern India. Field Crop Res. Aug 2017;209:168–78. 10.1016/j.fcr.2017.05.007.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Fleta-Soriano E, Munné-Bosch S. Stress memory and the inevitable effects of drought: A physiological perspective. Front Plant Sci. Feb 2016;7:143. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00143.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Bhattacharjee B, Ali A, Rangappa K, Choudhury BU, Mishra VK. A detailed study on genetic diversity, antioxidant machinery, and expression profile of drought-responsive genes in rice genotypes exposed to artificial osmotic stress. Sci Rep. Dec 2023;13(1):18388. 10.1038/s41598-023-45661-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Sagar A, Rauf F, Mia M, Shabi T, Rahman T, Hossain A. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) induced drought stress on five rice genotypes at early seedling stage. J Bangladesh Agric Univ. 2020;18(3):606–14. 10.5455/jbau.102585.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Rahman A, Nahar K, Al Mahmud J, Hasanuzzaman M, Hossain MdS, Fujita M. Salt stress tolerance in rice: Emerging role of exogenous phytoprotectants. In Advances in International Rice Research. InTech; 2017. 10.5772/67098.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Ahmad R, Hussain S, Anjum MA, Khalid MF, Saqib M, Zakir I, et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense mechanisms in plants under salt stress. In: Hasanuzzaman M, Hakeem K, Nahar K, Alharby H, editors. Plant abiotic stress tolerance. Cham: Springer; 2019. p. 191–205. 10.1007/978-3-030-06118-0_8.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Sofo A, Scopa A, Nuzzaci M, Vitti A. Ascorbate peroxidase and catalase activities and their genetic regulation in plants subjected to drought and salinity stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(6):13561–78. 10.3390/ijms160613561.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Passardi F, Penel C, Dunand C. Performing the paradoxical: How plant peroxidases modify the cell wall. Trends plant Sci. Nov 2004;9:534–40. 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.09.002.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] McInnis SM, Desikan R, Hancock JT, Hiscock SJ. Production of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species by angiosperm stigmas and pollen: Potential signalling crosstalk? N Phytol. Oct 2006;172(2):221–8. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01875.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Liszkay A, Kenk B, Schopfer P. Evidence for the involvement of cell wall peroxidase in the generation of hydroxyl radicals mediating extension growth. Planta. Aug 2003;217(4):658–67. 10.1007/s00425-003-1028-1.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Shen CX, Zhang QF, Li J, Bi FC, Yao N. Induction of programmed cell death in Arabidopsis and rice by single-wall carbon nanotubes. Am J Bot. Oct 2010;97(10):1602–9. 10.3732/ajb.1000073.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW, Dempfle L. Relative expression software tool (REST©) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:36e. [Online] http://docs.appliedbiosystems.com/pebiodocs/.10.1093/nar/30.9.e36Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Bian S, Jiang Y. Reactive oxygen species, antioxidant enzyme activities and gene expression patterns in leaves and roots of Kentucky bluegrass in response to drought stress and recovery. Sci Hortic. Apr 2009;120(2):264–70. 10.1016/j.scienta.2008.10.014.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Rossatto T, do Amaral MN, Benitez LC, Vighi IL, Braga E, de Magalhães Júnior AM, et al. Gene expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes in rice plants, cv. BRS AG, under saline stress. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. Oct 2017;23(4):865–75. 10.1007/s12298-017-0467-2.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] García-Caparrós P, De Filippis L, Gul A, Hasanuzzaman M, Ozturk M, Altay V, et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant metabolism under adverse environmental conditions: A review. Bot Rev. Dec 2021;87(4):421–66. 10.1007/s12229-020-09231-1.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Vighi IL, Benitez LC, do Amaral MN, Auler PA, Moraes GP, Rodrigues GS, et al. Changes in gene expression and catalase activity in Oryza sativa L. Under abiotic stress. Genet Mol Res. Nov 2016;15(4):gmr15048977. 10.4238/gmr15048977.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] Freeg HA, Attia KA, Casson S, Fiaz S, Ramadan EA, Banna AE, et al. Physio-biochemical responses and expressional profiling analysis of drought tolerant genes in new promising rice genotype. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3):e0266087. 10.1371/journal.pone.0266087.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[57] Refli R, Purwestri YA. The response of antioxidant genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedling Cv. Cempo Ireng under drought and salinity stresses. In AIP Conference Proceedings. American Institute of Physics Inc; Jun 2016. 10.1063/1.4953521.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Mehmood S, Ahmed W, Rizwan M, Imtiaz M, Elnahal ASMA, Ditta A, et al. Comparative efficacy of raw and HNO3-modified biochar derived from rice straw on vanadium transformation and its uptake by rice (Oryza sativa L.): Insights from photosynthesis, antioxidative response, and gene-expression profile. Environ Pollut. Nov 2021;289:117916. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117916.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[59] Abogadallah GM. Differential regulation of photorespiratory gene expression by moderate and severe salt and drought stress in relation to oxidative stress. Plant Sci. Mar 2011;180(3):540–7. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.12.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[60] Mittler R, Zilinskas BA. Regulation of pea cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase and other antioxidant enzymes during the progression of drought stress and following recovery from drought. Plant J. Mar 1994;5(3):397–405. 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1994.00397.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[61] Shikanai T, Takeda T, Yamauchi H, Sano S, Tomizawa KI, Yokota A, et al. Inhibition of ascorbate peroxidase under oxidative stress in tobacco having bacterial catalase in chloroplasts. FEBS Lett. May 1998;428(1–2):47–51. 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00483-9.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Koussounadis A, Langdon SP, Um IH, Harrison DJ, Smith VA. Relationship between differentially expressed mRNA and mRNA-protein correlations in a xenograft model system. Sci Rep. Jun 2015;5:10775. 10.1038/srep10775.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Nounjan N, Nghia PT, Theerakulpisut P. Exogenous proline and trehalose promote recovery of rice seedlings from salt-stress and differentially modulate antioxidant enzymes and expression of related genes. J Plant Physiol. Apr 2012;169(6):596–604. 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.01.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Hernandez-Elvira M, Sunnerhagen P. Post-transcriptional regulation during stress. Oxford University Press; 2022. 10.1093/femsyr/foac025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants

- Assessment of nutrition status of pineapple plants during ratoon season using diagnosis and recommendation integrated system

- Nutritional value and consumer assessment of 12 avocado crosses between cvs. Hass × Pionero

- The lacked access to beef in the low-income region: An evidence from the eastern part of Indonesia

- Comparison of milk consumption habits across two European countries: Pilot study in Portugal and France

- Antioxidant responses of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages

- Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

- Yield and vegetation index of different maize varieties and nitrogen doses under normal irrigation

- Urbanization and forecast possibilities of land use changes by 2050: New evidence in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam

- Organizational-economic efficiency of raspberry farming – case study of Kosovo

- Application of nitrogen-fixing purple non-sulfur bacteria in improving nitrogen uptake, growth, and yield of rice grown on extremely saline soil under greenhouse conditions

- Digital motivation, knowledge, and skills: Pathways to adaptive millennial farmers

- Investigation of biological characteristics of fruit development and physiological disorders of Musang King durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.)

- Enhancing rice yield and farmer welfare: Overcoming barriers to IPB 3S rice adoption in Indonesia

- Simulation model to realize soybean self-sufficiency and food security in Indonesia: A system dynamic approach

- Gender, empowerment, and rural sustainable development: A case study of crab business integration

- Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses of bacterial communities in short mackerel (Rastrelliger brachysoma) under storage conditions and inoculation of the histamine-producing bacterium

- Fostering women’s engagement in good agricultural practices within oil palm smallholdings: Evaluating the role of partnerships

- Increasing nitrogen use efficiency by reducing ammonia and nitrate losses from tomato production in Kabul, Afghanistan

- Physiological activities and yield of yacon potato are affected by soil water availability

- Vulnerability context due to COVID-19 and El Nino: Case study of poultry farming in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Wheat freshness recognition leveraging Gramian angular field and attention-augmented resnet

- Suggestions for promoting SOC storage within the carbon farming framework: Analyzing the INFOSOLO database

- Optimization of hot foam applications for thermal weed control in perennial crops and open-field vegetables

- Toxicity evaluation of metsulfuron-methyl, nicosulfuron, and methoxyfenozide as pesticides in Indonesia

- Fermentation parameters and nutritional value of silages from fodder mallow (Malva verticillata L.), white sweet clover (Melilotus albus Medik.), and their mixtures

- Five models and ten predictors for energy costs on farms in the European Union

- Effect of silvopastoral systems with integrated forest species from the Peruvian tropics on the soil chemical properties

- Transforming food systems in Semarang City, Indonesia: A short food supply chain model

- Understanding farmers’ behavior toward risk management practices and financial access: Evidence from chili farms in West Java, Indonesia

- Optimization of mixed botanical insecticides from Azadirachta indica and Calophyllum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda using response surface methodology

- Mapping socio-economic vulnerability and conflict in oil palm cultivation: A case study from West Papua, Indonesia

- Exploring rice consumption patterns and carbohydrate source diversification among the Indonesian community in Hungary

- Determinants of rice consumer lexicographic preferences in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

- Effect on growth and meat quality of weaned piglets and finishing pigs when hops (Humulus lupulus) are added to their rations

- Healthy motivations for food consumption in 16 countries

- The agriculture specialization through the lens of PESTLE analysis

- Combined application of chitosan-boron and chitosan-silicon nano-fertilizers with soybean protein hydrolysate to enhance rice growth and yield

- Stability and adaptability analyses to identify suitable high-yielding maize hybrids using PBSTAT-GE

- Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-mediated rock phosphate utilization with poultry manure enhances soil nutrient dynamics and maize growth in semi-arid soil

- Factors impacting on purchasing decision of organic food in developing countries: A systematic review

- Influence of flowering plants in maize crop on the interaction network of Tetragonula laeviceps colonies

- Bacillus subtilis 34 and water-retaining polymer reduce Meloidogyne javanica damage in tomato plants under water stress

- Vachellia tortilis leaf meal improves antioxidant activity and colour stability of broiler meat

- Evaluating the competitiveness of leading coffee-producing nations: A comparative advantage analysis across coffee product categories

- Application of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LP5 in vacuum-packaged cooked ham as a bioprotective culture

- Evaluation of tomato hybrid lines adapted to lowland

- South African commercial livestock farmers’ adaptation and coping strategies for agricultural drought

- Spatial analysis of desertification-sensitive areas in arid conditions based on modified MEDALUS approach and geospatial techniques

- Meta-analysis of the effect garlic (Allium sativum) on productive performance, egg quality, and lipid profiles in laying quails

- Optimizing carrageenan–citric acid synergy in mango gummies using response surface methodology

- The strategic role of agricultural vocational training in sustainable local food systems

- Agricultural planning grounded in regional rainfall patterns in the Colombian Orinoquia: An essential step for advancing climate-adapted and sustainable agriculture

- Perspectives of master’s graduates on organic agriculture: A Portuguese case study

- Developing a behavioral model to predict eco-friendly packaging use among millennials

- Government support during COVID-19 for vulnerable households in Central Vietnam

- Citric acid–modified coconut shell biochar mitigates saline–alkaline stress in Solanum lycopersicum L. by modulating enzyme activity in the plant and soil

- Herbal extracts: For green control of citrus Huanglongbing

- Research on the impact of insurance policies on the welfare effects of pork producers and consumers: Evidence from China

- Investigating the susceptibility and resistance barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars against the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia)

- Characterization of promising enterobacterial strains for silver nanoparticle synthesis and enhancement of product yields under optimal conditions

- Testing thawed rumen fluid to assess in vitro degradability and its link to phytochemical and fibre contents in selected herbs and spices

- Protein and iron enrichment on functional chicken sausage using plant-based natural resources

- Fruit and vegetable intake among Nigerian University students: patterns, preferences, and influencing factors

- Bioprospecting a plant growth-promoting and biocontrol bacterium isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico: Paenibacillus sp. strain TSM33

- Quantifying urban expansion and agricultural land conversion using spatial indices: evidence from the Red River Delta, Vietnam

- LEADER approach and sustainability overview in European countries

- Influence of visible light wavelengths on bioactive compounds and GABA contents in barley sprouts

- Assessing Albania’s readiness for the European Union-aligned organic agriculture expansion: a mixed-methods SWOT analysis integrating policy, market, and farmer perspectives

- Genetically modified foods’ questionable contribution to food security: exploring South African consumers’ knowledge and familiarity

- The role of global actors in the sustainability of upstream–downstream integration in the silk agribusiness

- Multidimensional sustainability assessment of smallholder dairy cattle farming systems post-foot and mouth disease outbreak in East Java, Indonesia: a Rapdairy approach

- Enhancing azoxystrobin efficacy against Pythium aphanidermatum rot using agricultural adjuvants

- Review Articles

- Reference dietary patterns in Portugal: Mediterranean diet vs Atlantic diet

- Evaluating the nutritional, therapeutic, and economic potential of Tetragonia decumbens Mill.: A promising wild leafy vegetable for bio-saline agriculture in South Africa

- A review on apple cultivation in Morocco: Current situation and future prospects

- Quercus acorns as a component of human dietary patterns

- CRISPR/Cas-based detection systems – emerging tools for plant pathology

- Short Communications

- An analysis of consumer behavior regarding green product purchases in Semarang, Indonesia: The use of SEM-PLS and the AIDA model

- Effect of NaOH concentration on production of Na-CMC derived from pineapple waste collected from local society

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants