Abstract

This study used thawed rumen fluid (TRF) to assess in vitro degradability and its relationship with the phytochemical and fibre contents of four herbs (green tea leaves, great burnet leaves, eucalyptus leaves, and oregano leaves) and five spices (black seed, cumin seeds, garlic bulb, onion flesh, and grape peel) using multivariate approaches. Duplicate samples of each herb and spice were incubated with TRF from each of four replicated steers for 48 h in an ANKOM DaisyII incubator. The results showed that each group of herbs and spices had different proximate, fibre, and phytochemical contents. Apparently, TRF was effective in estimating the in vitro degradability of different herbs and spices. Moreover, in vitro degradability was positively associated with total saponin content, while negatively correlated with fibre fractions. Principal component analysis identified two main dimensions, one associated with ‘fibre fractions’ and the other with ‘phytochemicals’, which were interpreted as the main factors influencing degradability. The multiple regression analysis demonstrated a positive correlation coefficient for the phytochemical contents of garlic bulb and onion flesh, indicating a considerable improvement in dry matter degradability (DMD). Additionally, the DMD values were significantly improved, as indicated by the positive correlations for the fibre fractions of onion flesh and green tea leaves. It can be concluded that the current multivariate analysis may be more accurate and useful for selecting or ranking various plants before their use as feed additives. However, further in vitro studies are needed to examine the effects of different levels of herbs and spices on degradability, fermentation, and gas production profiles of a much wider range of feeds and forages. This could be achieved by using TRF when fresh rumen fluid is not easily available due to the ever-increasing restrictions and logistics at an abattoir.

1 Introduction

Conducting animal-based in vivo experiments is challenging, invasive and costly, as it requires large amounts of different feeds to determine the degradability and digestibility of ingredients [1]. Additionally, animal trials are often inappropriate for evaluating single feedstuffs [2]. As a result, various in vitro methods using fresh [3], [4], [5], [6] or thawed [7], [8], [9], [10] rumen fluid have been developed as inexpensive alternatives to assess the nutritional value of feeds [11].

The nutritional value of a ruminant feed is determined not only by its chemical composition but also by the efficiency of its microbial degradation and digestion [12]. Plant-derived products and essential oils are increasingly investigated for their potential to improve nutrient use efficiency and reduce environmental impact [13]. This is linked to their secondary metabolite contents, such as saponins and tannins, which can not only exert anti- or pro-bacterial effects [14], but also contribute protein, fibre, and minerals that are found in most plants, such as tea leaves [15].

Different plants vary considerably in their content of phytochemicals and nutrients. For example, Sanguisorba officinalis is rich in phenolics, polysaccharide, and tannins with strong antioxidant properties [16]; black seed has been described as a ‘miracle plant’ due to its antibacterial activities [17]; eucalyptus leaves contain flavonoids and phenols [18]; garlic and onions are rich in saponins [19], and organosulfur compounds as the dominant bioactive constituents [20]; and grape pomace [21] and green tea [22] contain high concentrations of tannins. Understanding the phytochemical and proximate composition of herbs and spices is therefore essential, since excessive intake of some metabolites may limit their value as feed additives.

Despite their potential, the effects of plant secondary metabolites on ruminant fermentation remain inconsistent, partly due to variability in composition and interactions with other feed components such as fibre [23]. Rumen modifiers (e.g., essential oils, tannins, saponins, lipids) are widely available, but their efficacy is inconsistent across studies [24]. This makes evaluating different plant parts and their combined effects on degradability a continuing research priority.

In vitro fermentation studies typically rely on fresh rumen fluid (FRF) as an inoculum source, which requires immediate handling and continuous access to donor animals. However, obtaining FRF presents logistical and ethical challenges, particularly in facilities without in-house ruminants. Thawed rumen fluid (TRF) has emerged as a practical alternative, with recent studies showing comparable fermentation patterns to FRF under controlled conditions [7], [8], [9, 22], 25]. In the present study, TRF was utilised to assess the degradability of various herbs and spices. Multivariate techniques were further applied to link degradability outcomes with biochemical composition, thereby supporting a more informed selection of herbs and spices as potential ruminant feed additives.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Ethics statement

The studies were approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Board (AWERB) of Newcastle University, UK (Project ID No: 1089). Instead of using live and surgically modified animals, only steers that were freshly slaughtered for food were used to obtain rumen fluid (RF). Therefore, ethical standards for the use of animal-derived materials from only the UK approved farms were followed in this study.

2.2 Experimental design

In vitro incubation was conducted using a DAISYII incubator with four jars, each inoculated with buffered rumen fluid from one steer, effectively simulating four steers as biological replicates. While initial tests revealed no significant steer effect (P > 0.05), these individual jars were still treated as biological replicates to ensure statistical robustness and cover for inherent biological variability. Therefore, each plant material was tested in duplicate within each of four jars, resulting in eight replicated observations per treatment for each herb or spice.

The study was conducted using a completely randomised experimental design, with TRF from four replicated steers and duplicate sample bags in the ANKOM Daisy incubator. The experiment tested the in vitro DMD (IVDMD) and organic matter degradability (IVOMD) of four herbs: green tea leaves (Camellia sinensis, GTL), great burnet leaves (S. officinalis, GBL), oregano leaves (Origanum vulgare, OL), and eucalyptus leaves (Eucalyptus globulus, EL), as well as five spices: black seeds (Nigella sativa, BS), cumin seeds (Cuminum cyminum, CS), garlic bulbs (Allium sativum, GB), onion flesh (Allium cepa, OF), and grape peel (Vitis vinifera, GrP) before their use as feed additives.

2.3 Collection and storage of rumen fluid

Representative samples of frozen RF, stored at −20 °C for up to one month, were used in this study. These frozen samples were preserved in the laboratory from their fresh counterparts, which were obtained from four humanely killed steers at a local abattoir. The steers represented different breeds, ages, and farm locations, as shown in Table 1. Before slaughter, they had been fed diets containing fresh, dried, and ensiled grass with concentrates. This reflects expected variations amongst animals that are routinely received and processed at a typical abattoir.

Pre-slaughter features of four steers used to collect rumen fluid for in vitro incubations.

| Parameters | Steers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Farm location | Morpeth, Northumberland | Wigton, Cumbria | Thornton, Bradford | Morpeth, Northumberland |

| Breed | Aberdeen Angus X | Ayrshire X | Limousin X | Aberdeen Angus X |

| Age in days | 591 | 493 | 863 | 724 |

Soon after collection, the RF was filtered through four layers of muslin cloth using a large funnel and immediately transferred into pre-warmed, sterile, insulated thermos flasks (Thermos Ltd, UK) maintained at around 39 °C, which were flushed with CO2 and screw capped to maintain anaerobic conditions. The filtered samples were then transported to the laboratory for use as FRF in another in vitro study, and two 2 mL samples were each acidified at a 1:1 ratio with 1 N hydrochloric acid (HCl) and stored at −20 °C for subsequent analysis of ammonia nitrogen (NH3–N) and volatile fatty acids (VFAs). Simultaneously, measured portions of FRF from each of the four steers were aliquoted into sterile containers, flushed with CO2 to remove residual O2, tightly sealed, and stored at −20 °C until further use. Before incubation, the samples were thawed at 40 °C in a water bath and then filtered again through muslin cloth to remove large residual particulates and obtain TRF. Before incubation with the test feedstuffs, TRF from each steer was incubated under standard in vitro conditions without substrate to assess baseline fermentation traits, including pH, NH3–N, and VFAs. These values were compared with FRF from our lab and published data [2], 6], 10], 25] to confirm that TRF retained comparable fermentation characteristics, ensuring its suitability for ranking feeds in subsequent incubations. Although FRF is preferred, previous studies [4], [19], [20], [21], [22] have shown that properly handled TRF could still provide comparable, albeit lower, fermentation characteristics for ranking feeds. Although rumen fluid was collected in a single event on the same day, the samples were obtained from four different steers representing variation in breed, age, and diet. This approach introduces biological variability, while temporal variation across multiple collections is acknowledged as a limitation, but consistent with the previous reports [5], [7], [8], [9, 25].

2.4 Buffered inoculum

McDougall’s synthetic saliva [26] (Supplementary Table S1) was used as a buffer solution. It was placed into dark bottles, flushed with CO2, screw-capped, and maintained in a water bath at 39 °C. The frozen RF at −20 °C was thawed in a water bath at approximately 40 °C until fully liquefied, then filtered through four layers of muslin cloth to obtain TRF. Approximately 400 mL of TRF from each steer was then mixed with 1,600 mL of buffer in each 2.5 L Daisy jar, simulating a rumen environment. The jars were purged with CO2 to displace oxygen and firmly closed.

For subsequent analysis of NH3–N and VFAs, two 2 mL aliquots of TRF were each acidified at a 1:1 ratio with 1 N HCl and stored at −20 °C.

2.5 In vitro degradation using the ANKOM DAISYII incubator

The DaisyII incubator (ANKOM Technology) consisted of four separate digestion jars that allowed for constant rotation of the fermentation medium at the required temperature (39.5 ± 0.5 °C). Each jar acted as a simulated steer as it contained buffered TRF from a single steer as a biological replicate. For each jar, duplicate powder samples from each herb and spice were individually weighed into fibre filter bags (F57, pore size 25 µm; Ankom Technology®, Macedon, NY, USA), which were then sealed and incubated. The method followed standard procedures according to the operating instructions provided by the manufacturer (Ankom Technology®, Macedon, NY, USA).

Ground samples (0.50 g per bag) of each herb and spice were weighed into duplicate fibre filter bags, with two empty bags serving as blanks. The bags were heat-sealed and placed in digestion jars containing the buffered TRF. Although each sample was incubated in a separate bag within the same jar, we acknowledge that incubating multiple treatments together could allow cross-treatment interactions, for example, tannins from high-tannin substrates potentially affecting microbial activity in other samples. This limitation is inherent to the batch incubation system. However, using a shared environment mimics the natural rumen of an intact or a fistulated animal, where multiple feed components are fermented simultaneously. This approach ensures that all samples experienced identical fermentation conditions, reducing within-jar variability.

At the end of the 48-h incubation period, the jars were removed from the DaisyII chamber. The bags were collected, rinsed with tap water, oven-dried (Genlab drying oven, England) at 60 °C for 72 h, and weighed to determine IVDMD. Then the dried residues were ignited in a furnace at 550 °C for 5 h to determine organic matter (OM) content before estimating IVOMD.

2.6 Processing and biochemical analysis of samples

Before chemical analysis, all herb and spice samples were ground through a 1 mm sieve using a sample mill (TWISTER – Cyclone Mill 20.831, Germany). Dry matter (DM), organic matter (OM), and ether extract (EE) were determined using standard techniques [27], while crude protein (CP) was assessed by measuring total nitrogen (N) (N × 6.25 = CP) using a combustion assay (Elemental analyser, LECO CHN628, USA). The neutral detergent fibre (NDF) of each sample was determined using the previously reported method [28], without the use of amylase, dekalin, and sodium sulfite. The acid detergent fibre (ADF) and acid detergent lignin (ADL) contents were also determined [29]. The cellulose content was calculated by subtracting ADL values from ADF values, while the hemicellulose content was calculated by subtracting ADF values from NDF.

Total tannins (TT) were estimated using the Folin-Ciocalteu method [30], with tannic acid (Fisher Scientific, UK) as the standard. The condensed tannin (CT) content was determined using the butanol-HCl method [30], with (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (eMolecules, Fisher Scientific, UK) as the standard. The vanillin/HCl method [31] was employed to determine the total saponin (TS) content, using diosgenin (Fisher Scientific, UK) as the reference standard. A UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Libra S12, Biochrom Ltd, Cambridge, UK) was used to measure absorbance at 725 nm, 400 nm, and 544 nm for analysing TT, CT, and TS, respectively.

Ammonia nitrogen (NH3–N) was analysed according to the method of Broderick and Kang [32], using NH4Cl in H2O as the ammonium standard solution. A UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Libra S12, Biochrom Ltd, Cambridge, UK) was used to measure and record absorbance at 550 nm.

Volatile fatty acids, including acetate, propionate, n-butyrate, n-valerate, isobutyrate, and isovalerate, were analysed using a Dionex Aquion Ion Chromatography System (Thermo Scientific™, UK) equipped with an AS-AP autosampler and a Dionex IonPac ICE-AS1 column (4 × 250 mm). A 25 µL injection was run with a 1 mM heptafluorobutyric acid eluent at an isocratic flow rate of 0.16 mL/min for 35 min. The ACRS-ICE500 suppressor was used with 5 mM tetrabutyl ammonium hydroxide. The column oven temperature was set at 30 °C. Analytical-grade standards of acetic, propionic, butyric, valeric, isobutyric, and isovaleric acids were run at 5, 50, and 100 ppm. Total VFA concentration was calculated as the sum of all quantified acids.

2.7 Statistical analysis

All data sets were arranged in Microsoft Excel data sheets for Microsoft 365 (Part of Office 365 ProPlus, Newcastle University) before applying suitable comparative or statistical analyses by using Minitab 21 software as described below:

One-way ANOVA tests were conducted to compare the fermentation profiles of FRF with TRF after one month of freezing, with significance set at P < 0.05. Additionally, qualitative assessments compared the effectiveness of TRF with FRF based on previous studies from the same laboratory and from other research groups.

Moreover, one-way ANOVA was used to compare different materials within each group of herbs or spices for different proximate and phytochemical contents. Tukey’s post hoc test was employed to compare the means of each content within each group of herbs and spices (P < 0.05). Additionally, the effect of each herb and spice on in vitro degradability was examined using one-way ANOVA across various herbs and spices. Tukey’s post hoc test was also used to evaluate the individual means of IVDMD and IVOMD, among GTL, EL, OL, GBL, BS, CS, GB, OF, and GrP at P < 0.05.

Pearson’s correlation was used to explore relationships between each phytochemical or fibre fraction and each of the IVDMD and IVOMD of the tested herbs and spices. Only variables that showed significant correlations were further analysed using polynomial regression.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to examine patterns and relationships among different biochemical parameters. This multivariate method helps reduce data complexity while retaining essential information. Rotated factor loadings and commonalities were calculated to better understand how well each variable was represented by the extracted components.

Multiple regression analysis was then applied to determine how phytochemical compounds and fibre fractions influenced IVDMD. Additional regression models were developed using the first two principal components to assess their effect on IVDMD, based on the proportion of total variance they explained. The analysis focused on key variables including TT, CT, TS, and fibre fractions (NDF, ADF, and ADL).

3 Results

3.1 Comparative evaluation of thawed rumen fluid

In the current study, TRF displayed fermentation characteristics that were largely comparable to the FRF under identical conditions (Table 2). No differences (P > 0.05) were found between TRF and FRF in pH, NH3–N, total VFA, or main VFA components, including acetate, propionate, butyrate, and isovalerate. However, a slight but statistically significant difference was observed in valerate (P < 0.05), and a highly significant difference was noted in isobutyrate concentrations (P < 0.01), with TRF showing increased levels than FRF.

Comparison of fermentation characteristics between fresh and thawed rumen fluid from the current study and reference values reported in this and other laboratories.

| Traits | Current study | RF from literature | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRF | TRF | SEM | This lab FRF [3] | Other labs [6], 10], 25] | ||

| FRF | TRF | |||||

| pH | 7.5 | 7.5 | 0.19NS | 6.8–7.3 | 6.4–6.9 | 6.8–6.9 |

| NH3–N mg/L | 195 | 127 | 20.4NS | 63–123 | 134–261 | 64–127 |

| Total VFAs | 86.3 | 93.8 | 6.97NS | 61–82 | 47–122 | 43–64 |

| VFAs (mmol/L) | ||||||

| Acetate | 53 | 64 | 5.05NS | 53–76 | 30–77 | 27–29 |

| Propionate | 24 | 21 | 2.4NS | 18–31 | 9–15 | 7–10 |

| Butyrate | 8 | 6 | 0.8NS | 4.4–8.5 | 6–13 | 4–6 |

| Valerate | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.13* | 0.4–1.4 | 0.6–1.3 | 0.5–0.7 |

| Isobutyrate | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.18** | 0.7–2.6 | 0.4–13 | 0.3–23 |

| Isovalerate | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.28NS | 0.9–3.8 | 0.8–1.7 | 0.6–0.8 |

-

RF, rumen fluid; FRF, fresh rumen fluid; TRF, thawed rumen fluid; NH3–N, Ammonia concentration; VFAs, volatile fatty acids; n.d., not detected; SEM, standard error of the mean; P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), NS, not significant.

3.2 Proximate analysis

Table 3 shows differences between each set of herbs and spices for different proximate analyses (P < 0.01). Among the herbs, the CP contents of GBL and GTL were comparable and higher than those of the other herbs. Meanwhile, EL exhibited greater levels of EE, ADF, and ADL compared to the other herbs. Additionally, NDF and cellulose contents were higher in OL than in the other herbs. The hemicellulose contents of GTL and OL were comparable and significantly higher than those of GBL and EL. Regarding spices, BS had a significantly higher EE content than the other spices. The CP contents of BS and GB were similar and considerably higher than those of the other spices. Furthermore, GrP showed greater levels of NDF, ADF, and ADL than the other spices, while the hemicellulose content of GB was lower than that of BS, CS, and GrP.

Mean (n = 3) proximate composition (g/kg DM), standard error of means (SEM) and significance levels for values for four herbs and five spices.

| Herb/spice | Proximate content | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM | OM | CP | EE | NDF | ADF | ADL | Hemicellulose | Cellulose | |

| Herbs | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| GBL | 951B | 897D | 258A | 40B | 202D | 164C | 146C | 37b | 17B |

| EL | 949C | 957A | 63C | 118A | 353B | 330A | 291A | 22b | 38A |

| GTL | 965A | 953B | 256A | 44B | 251C | 137C | 127C | 110a | 10B |

| OL | 964A | 926C | 92B | 79AB | 391A | 279B | 239B | 107a | 40A |

| SEM | 2.17*** | 7.28*** | 27.3*** | 11.5* | 23.0*** | 24.2*** | 20.5*** | 12.6*** | 4.18*** |

|

|

|||||||||

| Spices | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| BS | 975A | 960B | 198A | 315A | 362C | 182B | 132B | 175a | 50A |

| CS | 969B | 886E | 170B | 79B | 406B | 222B | 184B | 179a | 38A |

| GB | 969B | 969A | 186A | 9B | 14E | 5C | n.d. | 8b | n.d. |

| OF | 924C | 930D | 125C | 28B | 138D | 173B | 153B | n.d. | 19A |

| GrP | 969B | 937C | 138C | 60B | 548A | 432A | 405A | 175a | 27A |

| SEM | 4.99*** | 7.82*** | 7.52*** | 30.5*** | 51.4*** | 37.0*** | 34.1*** | 22.2*** | 5.79NS |

-

GBL, great burnet leaf; EL, eucalyptus leaf; GTL, green tea leaf; OL, oregano leaf; BS, black seed; CS, cumin seed; GB, garlic bulb; OF, onion flesh; GrP, grape peel; DM, dry matter; OM, organic matter; CP, crude protein; EE, ether extract; NDF, neutral detergent fibre; ADF, Acid detergent fibre; ADL, acid detergent lignin. Means within a column for each nutrient in each group of herbs or spices with different letters (A, B, C and D) differed significantly (P < 0.05). Here *, *** and NS represent either significance at P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, or non-significant, respectively.

3.3 Phytochemical contents

The main differences for mean phytochemical amounts between various herbs and spices are shown in Table 4. The results for herbs indicated that the TT and CT contents of GTL, GBL, and EL were higher than those of OL. Great burnet leaves, on the other hand, contain significantly more TS than the other herbs. In terms of spices, the levels of TT and CT in grape peel were higher than those in the other spices. Additionally, GB and OF contain considerably more TS than the other spices.

Mean (n = 3) phytochemical contents (g/kg DM), standard error of means (SEM) and significance levels for values for herbs and spices.

| Herb/spice | Secondary metabolites content | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total tannin | Condensed tannin | Total saponin | |

| Herbs | |||

|

|

|||

| GBL | 69A | 25A | 11.8A |

| EL | 65A | 30A | 8.0B |

| GTL | 79A | 28.4A | 4.1C |

| OL | 20B | 2.4B | 8.0B |

| SEM | 7.68*** | 3.39*** | 0.88*** |

|

|

|||

| Spices | |||

|

|

|||

| BS | 3.68B | 0.51B | 11.89BC |

| CS | 3.82B | 0.88B | 13.45B |

| GB | 1.39B | 0.98B | 35.05A |

| OF | 0.73B | 0.27B | 33.44A |

| GrP | 8.44A | 4.78A | 10.32C |

| SEM | 0.77*** | 0.45*** | 2.95*** |

-

GBL, great burnet leaf; EL, eucalyptus leaf; GTL, green tea leaf; OL, oregano leaf; BS, black seed; CS, cumin powder; GB, garlic bulb; OF, onion flesh; GrP, grape peel. Means within a column for each content in each group of herbs or spices with different letters (A, B, C and D) differed significantly (P < 0.05). Here *** represents significance at P < 0.001.

3.4 In vitro degradability

Table 5 presents the mean in vitro degradability values of various herbs and spices. Different herbs and spices showed significant differences (P < 0.001) in their IVDMD and IVOMD. The highest IVDMD and IVOMD were observed in GB and OF, followed by GTL, CS, OL, GBL, BS, EL, and GrP.

Mean (n = 8) in vitro dry matter and organic matter degradability (g/kg DM) using the ANKOM DaisyII system of different herbs and spices.

| Herb/spice | Degradability (g/Kg DM) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dry matter | Organic matter | |

| Great burnet leaves | 525CD | 554D |

| Eucalyptus leaves | 420E | 461E |

| Green tea leaves | 687B | 702B |

| Oregano leaves | 563C | 604CD |

| Black seed | 475DE | 518DE |

| Cumin seed | 635B | 653BC |

| Garlic bulb | 996A | 996A |

| Onion flesh | 949A | 968A |

| Grape peel | 329F | 335F |

| SEM with significance | 26.0*** | 36.7*** |

-

Means within a column with different letters differ significantly (P < 0.01). Mean values were significantly different at P < 0.001 (***); SEM, standard error of the means; n, number of replicates.

3.5 Relationship between degradability and phytochemical contents and fibre fractions of herbs/spices

3.5.1 Correlation coefficient

The Pearson correlation coefficients between the phytochemical contents, fibre fractions of all herbs and spices, and IVDMD and IVOMD are shown in Table 6. A strong positive association (P < 0.01) was found between TS content in herbs and spices and degradability. The correlation coefficients (r) between TS and IVDMD and IVOMD were 0.82 and 0.80, respectively. Additionally, IVDMD and IVOMD showed a significant negative correlation (P < 0.01) with NDF, ADF, and ADL contents. The correlation coefficients between NDF and IVDMD and IVOMD were −0.85 and −0.87, respectively. For ADF, the correlation coefficients were −0.78 and −0.80, respectively, while the correlation values between ADL and IVDMD and IVOMD were −0.61 and −0.65, respectively. In contrast, the correlation coefficients between IVDMD and IVOMD with TT, CT, hemicellulose, and cellulose were negative but not statistically differ (Table 6). Furthermore, Table 7 shows the results of a polynomial regression analysis to relate the significant contents like TS, NDF, and ADF to the DM and OM degradability of the herbs and spices.

Correlation coefficients (r) between in vitro degradability traits and phytochemical and fibre contents of herbs and spices.

| Parameter | IVDMD | IVOMD |

|---|---|---|

| Total tannin | −0.25ns | −0.25ns |

| Condensed tannin | −0.29ns | −0.29ns |

| Total saponin | 0.82** | 0.80** |

| NDF | −0.85** | −0.87** |

| ADF | −0.78** | −0.80** |

| ADL | −0.61** | −0.65** |

| Hemicellulose | −0.29ns | −0.28ns |

| Cellulose | −0.32ns | −0.28ns |

-

IVDMD, in vitro dry matter degradability; IVOMD, in vitro organic matter degradability; NDF, neutral detergent fibre; ADF, acid detergent fibre; ADL, acid detergent lignin; **, P < 0.01; ns, non-significant.

Model performance metrics (standard error, R-squared, and P-values) for predicting IVDMD and IVOMD from total saponin (TS), neutral detergent fibre (NDF), acid detergent fibre (ADF), and acid detergent lignin (ADL) using linear, quadratic, and cubic regression.

| Response | Predictor | Standard error of the regression (S) | R-squared (%) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | Quadratic | Cubic | ||||

| IVDMD | TS | 93.6 | 85 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.008 |

| IVOMD | TS | 89.99 | 85 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.014 |

| IVDMD | NDF | 121.7 | 74 | 0.0001 | 0.0262 | 0.615 |

| IVOMD | NDF | 110.9 | 76 | 0.0001 | 0.381 | 0.431 |

| IVDMD | ADF | 146.7 | 62 | 0.0001 | 0.333 | 0.850 |

| IVOMD | ADF | 133.4 | 66 | 0.0001 | 0.362 | 0.803 |

| IVDMD | ADL | 151.4 | 46 | 0.002 | 0.921 | 0.084 |

| IVOMD | ADL | 139.7 | 49 | 0.001 | 0.944 | 0.129 |

-

IVDMD, in vitro dry matter degradability; IVOMD, in vitro organic matter degradability; TS, total saponin; NDF, neutral detergent fibre; ADF, acid detergent fibre; ADL, acid detergent lignin.

3.5.2 Principal components analysis (PCA)

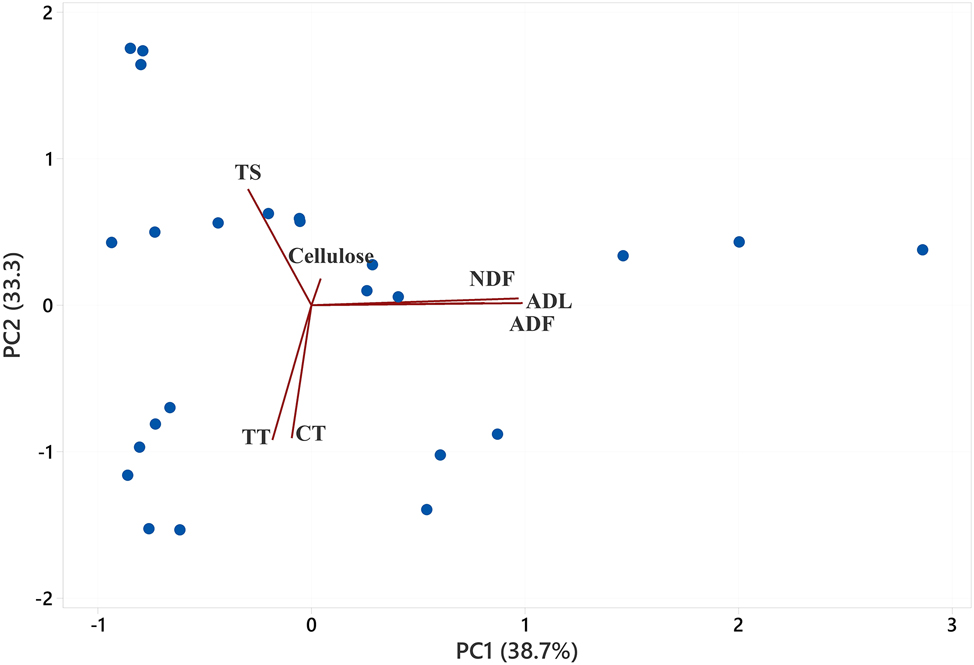

Table 8 and Figure 1 show the Principal Component Analysis results indicating the dataset’s underlying structure. It appears that only the first three components were determined to be relevant, accounting for 38.7 %, 33.3 %, and 20.2 % of the total variance among the seven investigated features. The fibre contents – specifically NDF, ADF, and ADL – loaded significantly on the first factor, with positive loadings of 0.81, 0.97, and 0.99, respectively. So, this component was referred to as the “fibre fraction” factor. The second component, derived from the phytochemical contents, exhibited strong negative loading scores for TT (−0.92) and CT (−0.91), while TS had a positive loading score (0.79); thus, it may be defined as the “phytochemical content” factor. Cellulose was found to load negatively on the third component with a score of −0.90, which is interpreted as the “cellulose” factor and represents a unique aspect of the dataset.

Rotated factor loadings and final communality estimates (c) from principal components analysis on phytochemical and fibre contents of herbs/spices.

| Traits | Component | (c)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Total tannin | −0.18 | −0.92 | 0.28 | 0.96 |

| Condensed tannin | −0.09 | −0.91 | 0.31 | 0.93 |

| Total saponin | −0.30 | 0.79 | 0.41 | 0.88 |

| Neutral detergent fibre | 0.81 | 0.02 | −0.50 | 0.91 |

| Acid detergent fibre | 0.97 | 0.05 | −0.12 | 0.96 |

| Acid detergent lignin | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.98 |

| Cellulose | 0.04 | 0.18 | −0.90 | 0.85 |

| Total | ||||

| Variance | 2.707 | 2.332 | 1.416 | 6.46 |

| Variance explained (% total) | 38.7 | 33.3 | 20.2 | 92 |

-

a(c), Final communality estimates. The bold values indicate the highest loading scores for each component.

Biplot of the first two principal component (PC) score vectors, describing the classification of each phytochemical and fibre content within the PC loading vectors. PC, principal component; TT, total tannin; CT, condensed tannin; TS, total saponin; NDF, neutral detergent fibre; ADF, acid detergent fibre; ADL, acid detergent lignin.

The PCA results identified two meaningful components: (1) a ‘fibre fraction’ factor, capturing variance in NDF, ADF, and ADL, and (2) a ‘phytochemical content’ factor, predominantly influenced by tannins and saponins. Although the first two principal components explained 72 % of the total variance, PCA still provided meaningful insights into the clustering of samples based on their chemical profiles and degradability characteristics. The overlap among herbs and spices in PC space suggests some degree of compositional similarity, particularly in fibre and phytochemical content. Notably, samples with high tannin or saponin contents tended to cluster away from those with lower levels, offering preliminary differentiation that can inform subsequent feed additive screening and ranking.

3.5.3 Multiple regression of PCA and IVDMD results

Multiple regression analysis was used to investigate the complex correlations between independent variables, specifically the phytochemical content factor (TT, CT, and TS) and the fibre fraction factor (NDF, ADF, and ADL), and the dependent variable, IVDMD (Tables 9 and 10). The analysis focused on small variations among nine different herbs and spices: GTL, GBL, EL, OL, BS, CS, GB, OF, and GrP. Each herb and spice was examined separately for its effect on IVDMD, without a specified reference herb or spice. The coefficients indicate the average difference relative to the overall mean of the dependent variable.

Multiple regression coefficients for IVDMD (g/kg) across categorical (herbs and spices) and continuous (TT, CT, and TS g/kg DM) variables (R 2 = 99.49 %).

| Term | Coef | SE coef | t-Value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 556.6 | 90.4 | 6.16 | 0.001 |

| TT | 1.154 | 0.620 | 1.86 | 0.082 |

| CT | −3.22 | 4.58 | −0.70 | 0.493 |

| TS | 4.38 | 4.67 | 0.94 | 0.363 |

|

|

||||

| Herbs/spices | ||||

|

|

||||

| GBL | −72.1 | 59.1 | −1.22 | 0.241 |

| BS | −154.5 | 47.6 | −3.25 | 0.005 |

| CS | 35.4 | 42.7 | 0.83 | 0.421 |

| EL | −141.1 | 79.5 | −1.78 | 0.096 |

| GB | 286.7 | 92.6 | 3.10 | 0.007 |

| GrP | −275.9 | 36.6 | −7.54 | 0.001 |

| GTL | 119.6 | 79.4 | 1.51 | 0.153 |

| OL | −64.1 | 55.9 | −1.15 | 0.269 |

| OF | 266.2 | 86.2 | 3.09 | 0.008 |

-

Coef, coefficient; SE, standard error; TT, total tannin; CT, condensed tannin; TS, total saponin; GBL, great burnet leaves; BS, black seeds; CS, cumin seeds; EL, eucalyptus leaves; GB, garlic bulb; GrP, grape peel; GTL, green tea leaves; OL, oregano leaves; OF, onion flesh.

Multiple regression coefficients for IVDMD g/kg across categorical (herbs and spices) and continuous (NDF, ADF, and ADL g/kg DM) variables (R 2 = 99.12 %).

| Term | Coef | SE coef | t-Value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 211 | 225 | 0.94 | 0.365 |

| NDF | 0.991 | 0.637 | 1.56 | 0.144 |

| ADF | 0.515 | 0.484 | 1.06 | 0.307 |

| ADL | −0.419 | 0.430 | −0.97 | 0.348 |

|

|

||||

| Herbs/spices | ||||

|

|

||||

| GBL | 101.0 | 87.3 | 1.16 | 0.268 |

| BS | −151.3 | 29.0 | −5.22 | 0.001 |

| CS | 1.5 | 50.0 | 0.03 | 0.976 |

| EL | −179.1 | 30.3 | −5.91 | 0.001 |

| GrP | −486 | 150 | −3.25 | 0.006 |

| GTL | 216.6 | 61.2 | 3.54 | 0.004 |

| OL | −99.3 | 42.3 | −2.35 | 0.035 |

| OF | 597 | 127 | 4.71 | 0.001 |

-

Coef, coefficient; SE, standard error; NDF, neutral detergent fibre; ADF, acid detergent fibre; ADL, acid detergent lignin; GBL, great burnet leaves; BS, black seeds; CS, cumin seeds; EL, eucalyptus leaves; GrP, grape peel; GTL, green tea leaves; OL, oregano leaves; OF, onion flesh.

The multiple regression analysis explored various predictors of IVDMD across different herbs and spices. Among the independent variables examined, TT, CT, and TS did not demonstrate significant relationships with IVDMD (TT: coef. = 1.15, P = 0.08; CT: coef. = −3.22, P = 0.49; TS: coef. = 4.38, P = 0.36). These findings suggest that variations in TT, CT, and TS contents may not reliably predict changes in IVDMD across different categories of herbs and spices. Conversely, GB (coef. = 287, P = 0.007) and OF (coef. = 266, P = 0.008) showed significant positive associations, indicating that they enhance IVDMD. Additionally, variables such as GrP (coef. = −276, P = 0.001) and BS (coef. = −155, P = 0.005) exhibited significant negative relationships with IVDMD, suggesting that higher levels of BS and GrP are associated with reduced IVDMD. Meanwhile, GBL, GTL, OL, EL, and CS did not show significant relationships.

Among the independent variables examined, the NDF, ADF, and ADL contents did not demonstrate significant relationships with IVDMD (NDF: coef. = 0.99, P = 0.14; ADF: coef. = 0.52, P = 0.31; ADL: coef. = −0.42, P = 0.35). Conversely, OF (coef. = 597, P = 0.001) and GTL (coef. = 217, P = 0.004) showed significant positive associations, indicating that they enhanced IVDMD. Additionally, variables such as GrP (coef. = −486, P = 0.006), EL (coef. = −179, P = 0.001), BS (coef. = −151, P = 0.001), and OL (coef. = −99, P = 0.04) exhibited significant negative relationships with IVDMD, suggesting that higher levels of GrP, EL, BS, and OL were associated with reduced IVDMD. Meanwhile, GBL and CS did not show significant relationships with IVDMD.

4 Discussion

Evaluation of the functional properties of herbs and spices, including proximate and secondary metabolite compositions, is essential. Many plants are consumed without adequate information about their metabolites, which, if ingested in excess, may limit their effectiveness as feed additives. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to assess selected herbs and spices for their proximate and phytochemical contents, as well as their in vitro degradability, before considering them as potential ruminant feed additives.

Recent research has supported using TRF as an inoculum source for in vitro fermentation studies. Recently, Ma et al. [5] demonstrated that the concentrate-to-forage ratio affects fermentation and bacterial diversity independently of inoculum type, confirming the suitability of TRF for evaluating starch content effects. Similarly, Tunkala et al. [9], 33] showed that RF stored at −20 °C yielded gas production results that were comparable to FRF, with no differences in total gas production or lag time over six months, making storage at −20 °C preferable to −80 °C. Additionally, Chaudhry and Mohamed [7] noted that TRF can reliably predict in vitro degradation when FRF is not readily available. This is supported by the findings of Qiu et al. [25] and Pramita et al. [8], who found that freezing at −20 °C or −80 °C did not affect the microbial population composition or fermentation characteristics. Overall, these findings justify the use of TRF in the present study as a reliable alternative to FRF for the fermentation assessment of various feeds.

When compared with RF characteristics reported in previous studies (Table 2), the TRF used in this investigation fell within or near the reported ranges for FRF from the same laboratory [3] and from other laboratories [6], 10], 25]. The pH (7.5) was consistent with prior observations, and ammonia concentrations (127 mg/L) remained within the expected range despite being slightly lower than in the fresh counterpart. Total VFA and major VFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate in TRF also aligned with earlier values, further indicating preserved fermentative potential. The higher isobutyrate level observed in TRF falls within the broader range reported in literature and may reflect microbial adaptation or selective survival of certain species during the freeze–thaw process. These results support the reliability of using TRF as a substitute for FRF in in vitro fermentation trials when immediate access to fresh inoculum is not feasible.

The results showed that various herbs and spices differed significantly in most proximate compositions. These differences may be attributed to variations in plant varieties and climatic conditions in different growing locations [34]. Furthermore, this finding suggests that GTL, GBL, BS, and GB are good sources of protein.

The NDF fraction, which represents the entire cell wall (cellulose + hemicellulose + lignin), ranged from 202 to 391 g/kg DM in herbs, while it ranged from 14 to 548 g/kg DM in spices. These amounts are lower than the aerial fraction reported for several forage sources, which ranged from 595 to 846 g/kg DM [14]. However, our values are comparable to those reported by Ramdani et al. [22] for green tea leaves, Thao et al. [35] for eucalyptus leaves, and Stefenoni et al. [36] for oregano leaves. Notably, OL exhibited the highest NDF content, exceeding the findings of Olijhoek et al. [37], who reported NDF values of 243–289 g/kg DM. However, these values are comparable to those reported by El-Naggar and Ibrahim [38] and Bhargav et al. [39], for CS, as well as by Foiklang et al. [40] and Moate et al. [41], for GrP. In contrast to Al-Naqeep et al. [42], who observed NDF values of 206–271 g/kg DM, black seed exhibited a higher NDF content in this study. Additionally, climatic conditions have an impact; according to Pascual et al. [43], high temperatures and low precipitation are associated with increased cell wall carbohydrates (NDF) and decreased soluble content in various plants.

The ADF (lignocellulose) and ADL (lignin) fractions varied among the investigated herbs. Our results for EL and OL are consistent with previously reported findings [36], 44]. However, EL showed the highest ADF content, surpassing the findings of Thao et al. [35] who reported 220 g ADF/kg DM for EL. Additionally, Kondo et al. [45] determined that the ADF content in green tea by-products was 289 g/kg DM, while Sallam et al. [12] found that EL contained 493–504 g ADF/kg DM, which is higher than the results of the current study. The investigated spices also displayed varying ADF and ADL contents, with results for GrP and CS aligning with those previously reported [39], 41], respectively. While others reported 65–89 g ADF/kg DM [42] and 120 g ADF/kg DM [34] in BS, the current study found a higher ADF proportion. Moreover, Foiklang et al. [40] determined that the ADF content in grape pomace was 306 g/kg DM, and Juráček et al. [46] discovered that dried grape pomace contained 380 g ADF/kg DM, which is lower than the results of the current study. The growth stage is an important factor to consider, and genotype plays a key role in the accumulation of fibres in the cell wall [47].

The GBL was not compared to other findings because, to the best of our knowledge, no data on the proximate analysis of great burnet (S. officinalis L.) were available in the literature.

Preliminary phytochemical profiling provides important information about the variety of distinct groups of secondary metabolites in plant extracts [48]. Plant secondary metabolites have long been considered vital for protecting plants against predators, and their synthesis is influenced by environmental, seasonal, and external stimuli [49]. Although secondary metabolites have traditionally been viewed as hazardous to animals and identified as anti-nutritional agents [50], they have gained popularity in animal nutrition in recent decades due to their positive effects on parasite management, rumen fermentation, and methane reduction [49].

The selected herbs were rich in tannin content. Similar results were reported for TT (77 g GAE/kg), CT (19 g leucocyanidin/kg), and TS (13 g DE/kg) in EL [51]. Furthermore, Singh [52] found the same CT value in OL. Additionally, Samadi and Fatemeh [53] observed comparable TT results in GTL. In contrast, the TT, CT, and TS contents of GTL in this investigation were much lower than those reported previously, which used the same reference standard equivalents 231, 204, 176, and 276 g/kg DM, respectively [22]. Similarly, Sallam et al. [12] noted higher TT levels in EL, whereas Bendifallah et al. [54] found higher amounts in OL, which contrasts with the current study’s findings. On the other hand, the TT and TS levels reported for both OL [55] and EL [56] were lower than the results found in this study.

The selected spices were rich in saponin content. Similarly, Akeem et al. [19] reported comparable CT and TS values in GB, whereas the CT and TS contents of GrP in the current study were much lower than those previously reported by Spanghero et al. [57]. Similarly, Milutinović et al. [58] noted higher amounts of CT in grape pomace. In addition, Khan and Chaudhry [59] discovered higher levels of CT and TS in CS. However, different plants may have various constituents and nutritional benefits depending on where they are cultivated or sourced [42]. Moreover, it was indicated that several factors could influence the phytochemical composition, including growing locations, maturation stages, processing techniques, and isolation methods [24].

High levels of tannins in the diet (6–12 % DM) may reduce animal production and digestive efficiency [60]. More recently, Gerlach et al. [61] found no influence of tannins on the digestibility of concentrate organic matter at a tannin level of 1 %. However, digestibility decreased when the tannin contents were 3 % (−21 %) and 5 % (−28 %). According to Cabral et al. [62], who studied three levels of tannins in sheep diets, low-, medium-, and high-tannin cultivars exhibited distinctly different DM digestibility. Therefore, Besharati et al. [63] demonstrated in their review article that the ingestion of tannins altered digestibility by affecting the pattern of ruminal fermentation. Although these effects are discussed in two subsections, the repeated conclusion is that increased dietary tannin levels could decrease food digestion by raising nitrogen excretion in the faeces. Nevertheless, depending on their quantity, type, chemical structure, and feed composition, condensed tannins can have either positive or negative effects on ruminants, especially when there is a high percentage of crude protein in the diet [64].

Saponins have been studied for their ability to influence rumen fermentation by reducing protozoal populations, thereby lowering hydrogen (H2) availability and methane (CH4) production [65]. Saponins can form complexes with the lipid membranes of bacteria, increasing their permeability, causing an imbalance, and resulting in the lysis of the microorganisms; most saponins do influence protozoa [66]. Moreover, Wallace et al. [67] proposed that saponins disrupt protozoa by forming complexes with sterols on the protozoan membrane surface, leading to impairment and disintegration. Therefore, determining the phytochemical contents of herbs and spices before adding them to the ration is critical for determining the total amount of additives to be used.

The Ankom DaisyII incubator was developed as a rumen simulation equipment to facilitate the measurement of in vitro degradability. The procedure involves degrading multiple feed samples in bags simultaneously within glass jars that are rotated in an enclosed chamber. Compared to traditional techniques, such as the first stage of the Tilley and Terry [68] method and the Van Soest et al. [69] method, the Ankom DaisyII incubator offers advantages in terms of time, efficiency, and labour requirements [70]. Its design allows for the examination of a high number of samples [71], 72]. It is a simple, affordable, and effective instrument for estimating the degradability of a variety of diets and feedstuffs [73] simultaneously. Simply, it can mimic the rumen of four ruminant animals, e.g. sheep, goat, cattle, while placed together in the same anaerobic chamber.

Due to the initial focus on the in vitro degradation of each herb and spice individually, it is challenging to compare the current findings with those of previous investigations where spices and herbs were tested as additives or supplements alongside other feeds. However, the lower concentration of fibre fractions may explain the higher in vitro degradability of GB and OF (Table 5). Conversely, GrP exhibited reduced in vitro degradation of DM and OM contents due to its higher fibre contents (Table 3). This is supported by the negative association between fibre content and the IVDMD and IVOMD values (Table 6).

Due to the complexity of interactions among fibre components and phytochemical contents, multivariate statistical methods were employed to determine key drivers of degradability. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) revealed clustering patterns linked to both fibre content and secondary metabolites, highlighting differentiation between herbs and spices. Additionally, multiple linear regression models were constructed to predict IVDMD using quantitative predictors such as NDF, ADF, and total tannins. The inclusion of categorical variables (e.g., herb vs. spice) helped capture compositional variation, offering practical insights into the degradability potential of individual additives. The two main PCs were the fibre fractions (NDF, ADF, and ADL) and the phytochemical contents (TT, CT, and TS), while the third component was cellulose. These two PCs can be utilised to select herbs and spices as feed additives. However, it is not advisable to rely on a single feature for herb/spice selection, as this may disrupt other related traits; therefore, such issues can be mitigated by calculating and applying PCs. The primary challenges for evaluating herbs and spices in ruminant feeds, whether in vitro or in vivo, are the required labour and high costs. Nevertheless, depending on the selection goal, reducing the number of necessary measurements may make this approach feasible, allowing the final selection to be based on fewer traits. Although labour and cost may continue to be significant issues, such practices should be implemented before utilising herbs and spices in feed. Consequently, it may be possible to rely on one of the first principal components (fibre fractions) when selecting herbs and spices as feed additives, rather than assessing all contents, due to the high correlation between them. The same approach applies to the phytochemical contents as the second principal component.

The multiple regression analysis was performed to assess the impact of phytochemical components (e.g., tannins and saponins) and fibre fractions (e.g., NDF and ADF) on IVDMD across different herbs and spices. Since each plant material possesses unique chemical compositions that may affect ruminal degradation differently, including individual herbs and spices as categorical variables, allowed for a more comprehensive evaluation of their effects.

This approach provided key insights, including the identification of primary degradability drivers, the relative ranking of different feed additives, and potential interaction effects between fibre fractions and secondary metabolites. While correlation analysis identifies pairwise relationships, multiple regression accounts for the simultaneous influence of multiple factors, ensuring that the observed effects are not confounded by interdependencies.

The results indicated that tannins and saponins had no impact on IVDMD across different herbs and spices. However, some individual plant materials (e.g., garlic bulb and onion flesh) exhibited higher IVDMD, whereas others (e.g., grape peel and black seed) showed reduced degradability. These findings suggest that phytochemical composition alone may not be the primary determinant of IVDMD, reinforcing the importance of evaluating both fibre fractions and secondary metabolites together.

Due to the absence of ADL in the fibre fraction assessment, garlic bulbs were not included in the multiple regression analysis. The in vitro dry matter degradability values of OF and GTL showed significant improvement, as indicated by their positive coefficients. This suggests that the lower NDF, ADF, and ADL contents in OF and GTL may contribute to their higher IVDMD. Conversely, the negative coefficients for NDF, ADF, and ADL contents in GrP, EL, BS, and OL indicate a decrease in their IVDMD. This suggests that the fibre and phytochemical contents of each herb and spice indicate their potential as feed additives, given their impact on degradability, which may affect the substrate feed components. The differences in coefficients among the studied herbs and spices highlight various factors influencing IVDMD across different feed groups. These findings contribute to the growing body of knowledge regarding the quality of herbs and spices and guide future research efforts aimed at enhancing nutritional management strategies for optimal ruminant nutrition.

5 Conclusions

This study confirms that TRF can be used effectively as an alternative to FRF for screening and ranking herbs and spices for in vitro degradability, as TRF preserved sufficient microbial activity, as indicated by the fermentation characteristics. The presence of significant quantities of TT and CT in GTL, GBL, and EL, as well as high levels of TS in GBL and all spices, particularly GB and OF, suggests that these herbs and spices might serve as natural additives in ruminant diets. Based on standard evaluations of proximate composition, phytochemical contents, and in vitro degradability, all herbs and spices except GrP appear useful for promoting rumen degradability. However, advanced multivariate analyses (PCA and multiple regression) provided a more precise assessment of feed additive potential, identifying GB, OF, GTL, GBL, CS, and OL, in descending order of effectiveness, as the most promising candidates. Conversely, GrP, EL, and BS may have had minimal or negative impact on degradability. These findings highlight the limitations of relying solely on traditional compositional analysis for feed additive selection and demonstrate that multivariate statistical approaches offer a more meaningful strategy for pre-screening botanicals in ruminant nutrition research. Further studies should explore dose-response effects and validate these findings in vivo before implementation.

-

Funding information: This study was supported by the Higher Committee for Education Development in Iraq (HCED-IRAQ).

-

Author contributions: All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication. KM conceived, designed, and conducted the study, including data evaluation and analysis. ASC conceived and contributed to the experimental design. KM drafted the original manuscript, which was revised following discussions on data interpretation with ASC and JS. Additionally, ASC provided supervision and participated in the review and editing of the manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing interests.

-

Ethical approval: The studies were approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Board (AWERB) of Newcastle University, UK (Project ID No: 1089) for the use of animal-derived materials. No live animals were involved in this study. Instead, slaughtered steers at an approved abattoir were used as donors to obtain rumen fluid.

-

Data availability statement: None of the data or models has been submitted to an official repository. The corresponding author can provide the datasets generated and analysed during the current investigation upon reasonable request.

References

1. Estes, KA, Yoder, PS, Stoffel, CM, Hanigan, MD. An evaluation of the validity of an in vitro and an in situ/in vitro procedure for assessing protein digestibility of blood meal, feather meal and a rumen-protected lysine prototype. Transl Anim Sci 2022;6:txac039. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txac039.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Steiner, D, Krska, R, Malachova, A, Taschl, I, Sulyok, M. Evaluation of matrix effects and extraction efficiencies of LC-MS/MS methods as the essential part for proper validation of multiclass contaminants in complex feed. J Agric Food Chem 2020;68:3868–80. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.9b07706.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

3. Chaudhry, AS. Slaughtered cattle as a source of rumen fluid to evaluate supplements for in vitro degradation of grass nuts and barley straw. Open Vet Sci J 2008;2:16–22. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874318808002010016.Search in Google Scholar

4. Chaudhry, AS, Khan, MMH. Impacts of different spices on in vitro rumen dry matter disappearance, fermentation and methane of wheat or ryegrass hay based substrates. Livest Sci 2012;146:84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.livsci.2012.01.007.Search in Google Scholar

5. Ma, ZY, Zhou, JW, Yi, SY, Wang, M, Tan, ZL. Inoculation of fresh or frozen rumen fluid distinguishes contrasting microbial communities and fermentation induced by increasing forage to concentrate ratio. Front Nutr 2022;8.10.3389/fnut.2021.772645Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Spanghero, M, Chiaravalli, M, Colombini, S, Fabro, C, Froldi, F, Mason, F, et al.. Rumen inoculum collected from cows at slaughter or from a continuous fermenter and preserved in warm, refrigerated, chilled or freeze-dried environments for in vitro tests. Animals 2019;9:815. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9100815.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

7. Chaudhry, AS, Mohamed, RAI. Fresh or frozen rumen contents from slaughtered cattle to estimatein vitro degradation of two contrasting feeds. Czech J Anim Sci 2012;57:265–73. https://doi.org/10.17221/5961-cjas.Search in Google Scholar

8. Pramita, MS, Soetanto, H, editors. The potential of frozen rumen fluid for ruminant feed evaluation using in vitro gas production technique. In: E3S Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences; 2022.10.1051/e3sconf/202233500053Search in Google Scholar

9. Tunkala, BZ, DiGiacomo, K, Alvarez Hess, PS, Dunshea, FR, Leury, BJ. Rumen fluid preservation for in vitro gas production systems. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2022;292:115405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2022.115405.Search in Google Scholar

10. Fu, CP, Qu, MR, Ouyang, KH, Qiu, QH. Effects of storage time and temperature on the fermentation characteristics of rumen fluid from a high-forage diet. Agriculture 2024;14:1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14091481.Search in Google Scholar

11. Vinyard, JR, Faciola, AP. Unraveling the pros and cons of various in vitro methodologies for ruminant nutrition: a review. Transl Anim Sci 2022;6:txac130. https://doi.org/10.1093/tas/txac130.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Sallam, SMA, Bueno, ICS, Nasser, MEA, Abdalla, AL. Effect of eucalyptus (Eucalyptus citriodora) fresh or residue leaves on methane emission in vitro. Ital J Anim Sci 2010;9:299–303.Search in Google Scholar

13. Benchaar, C, Petit, HV, Berthiaume, R, Ouellet, DR, Chiquette, J, Chouinard, PY. Effects of essential oils on digestion, ruminal fermentation, rumen microbial populations, milk production, and milk composition in dairy cows fed alfalfa silage or corn silage. J Dairy Sci 2007;90:886–97. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(07)71572-2.Search in Google Scholar

14. Ramdani, D, Chaudhry, AS, Hernaman, I, Seal, CJ. Comparing tea leaf products and other forages for In-vitro degradability, fermentation, and methane for their potential use as natural additives for ruminants. KnE Life Sci 2017;2:63. https://doi.org/10.18502/kls.v2i6.1020.Search in Google Scholar

15. Ramdani, D, Chaudhry, AS, Seal, CJ. Chemical composition, plant secondary metabolites, and minerals of green and black teas and the effect of different tea-to-water ratios during their extraction on the composition of their spent leaves as potential additives for ruminants. J Agric Food Chem 2013;61:4961–7. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf4002439.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

16. Jang, E, Kim, S, Lee, N-R, Kim, H, Chae, S, Han, C-W, et al.. Sanguisorba officinalis extract, ziyuglycoside I, and II exhibit antiviral effects against hepatitis B virus. Eur J Integr Med 2018;20:165–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2018.05.009.Search in Google Scholar

17. Almatroudi, A, Khadri, H, Azam, M, Rahmani, AH, Al Khaleefah, FK, Khateef, R, et al.. Antibacterial, antibiofilm and anticancer activity of biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles using seed extract of Nigella sativa. Processes 2020;8:388. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr8040388.Search in Google Scholar

18. Kaur, S, Gupta, S, Gautam, PB. Phytochemical analysis of Eucalyptus leaves extract. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2019;8:2442–6.Search in Google Scholar

19. Akeem, S, Joseph, J, Kayode, R, Kolawole, F. Comparative phytochemical analysis and use of some Nigerian spices. Croat J Food Technol Biotechnol Nutr 2016;11:145–1.Search in Google Scholar

20. Walag, AMP, Ahmed, O, Jeevanandam, J, Akram, M, Ephraim-Emmanuel, BC, Egbuna, C, et al.. Health benefits of organosulfur compounds. In: Functional foods and nutraceuticals: bioactive components, formulations and innovations. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020:445–72 pp.10.1007/978-3-030-42319-3_21Search in Google Scholar

21. Onache, PA, Geana, E-I, Ciucure, CT, Florea, A, Sumedrea, DI, Ionete, RE, et al.. Bioactive phytochemical composition of grape pomace resulted from different white and red grape cultivars. Separations 2022;9:395. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations9120395.Search in Google Scholar

22. Ramdani, D, Jayanegara, A, Chaudhry, AS. Biochemical properties of black and green teas and their insoluble residues as natural dietary additives to optimize in vitro rumen degradability and fermentation but reduce methane in sheep. Animals (Basel) 2022;12:305. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12030305.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

23. Firkins, JL, Henderson, EL, Duan, H, Pope, PB. International symposium on ruminant physiology: current perspective on rumen microbial ecology to improve fiber digestibility. J Dairy Sci 2024;108:7511–29. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2024-25863.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

24. Hannan, MA, Rahman, MA, Sohag, AAM, Uddin, MJ, Dash, R, Sikder, MH, et al.. Black cumin (Nigella sativa L.): a comprehensive review on phytochemistry, health benefits, molecular pharmacology, and safety. Nutrients 2021;13:1784. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13061784.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

25. Qiu, Q, Long, T, Ouyang, K, Lei, X, Qiu, J, Zhang, J, et al.. Effect of preservation temperature and time on fermentation characteristics, bacterial diversity and community composition of rumen fluid collected from high-grain feeding sheep. Fermentation 2023;9:466. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9050466.Search in Google Scholar

26. McDougall, EI. Studies on ruminant saliva. 1. The composition and output of sheep’s saliva. Biochem J 1948;43:99–109. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj0430099.Search in Google Scholar

27. International, A, editor. Guidelines for Collaborative Study Procedures to Validate Characteristics of a Method of Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2023.Search in Google Scholar

28. Van Soest, PJ, Robertson, JB, Lewis, BA. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J Dairy Sci 1991;74:3583–97. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(91)78551-2.Search in Google Scholar

29. Van Soest, PJ. Use of detergents in the analysis of fibrous feeds. II. A rapid method for the determination fiber and lignin. J Assoc Off Anal Chem 1963;46:829–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaoac/46.5.829.Search in Google Scholar

30. Makkar, HPS. Quantification of tannins in tree and shrub foliage: a laboratory manual. Vienna, Austria: Springer Science & Business Media; 2003.10.1007/978-94-017-0273-7Search in Google Scholar

31. Makkar, HPS, Siddhuraju, P, Becker, K. Plant secondary metabolites. Totowa, New Jersy, USA: Humana Press Inc; 2007.10.1007/978-1-59745-425-4Search in Google Scholar

32. Broderick, GA, Kang, JH. Automated simultaneous determination of ammonia and total amino acids in ruminal fluid and in vitro media. J Dairy Sci 1980;63:64–75. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(80)82888-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

33. Tunkala, BZ, DiGiacomo, K, Alvarez Hess, PS, Dunshea, FR, Leury, BJ. Impact of rumen fluid storage on in vitro feed fermentation characteristics. Fermentation 2023;9:392. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation9040392.Search in Google Scholar

34. Medjekal, S, Bodas, R, Bousseboua, H, López, S. Evaluation of three medicinal plants for methane production potential, fiber digestion and rumen fermentation in vitro. Energy Proc 2017;119:632–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.07.089.Search in Google Scholar

35. Thao, NT, Wanapat, M, Kang, S, Cherdthong, A. Effects of supplementation of eucalyptus (E. Camaldulensis) leaf meal on feed intake and rumen fermentation efficiency in swamp buffaloes. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2015;28:951–7. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.14.0878.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

36. Stefenoni, H, Räisänen, S, Cueva, S, Wasson, DE, Lage, C, Melgar, A, et al.. Effects of the macroalga Asparagopsis taxiformis and oregano leaves on methane emission, rumen fermentation, and lactational performance of dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 2021;104:4157–73. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2020-19686.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

37. Olijhoek, DW, Hellwing, ALF, Grevsen, K, Haveman, LS, Chowdhury, MR, Lovendahl, P, et al.. Effect of dried oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) plant material in feed on methane production, rumen fermentation, nutrient digestibility, and milk fatty acid composition in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 2019;102:9902–18. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2019-16329.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

38. El-Naggar, S, Ibrahim, E. Impact of incorporating garlic or cumin powder in lambs ration on nutrients digestibility, blood constituents and growth performance. Egypt J Nutr Feed 2018;21:355–64. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejnf.2018.75530.Search in Google Scholar

39. Bhargav, S, Patil, AK, Jain, RK, Kurechiya, N, Aich, R, Jayraw, AK. (Effect of Dietady Incluiion of CumincSeed sCuminum cyminum) on Volunvary Feed fntaki, Milk mieldy Milk mualiqy and UdderuHealth of DairydCows.cAsian J Dairy Food Res 2025;44:320–5.Search in Google Scholar

40. Foiklang, S, Wanapat, M, Norrapoke, T. In vitro rumen fermentation and digestibility of buffaloes as influenced by grape pomace powder and urea treated rice straw supplementation. Anim Sci J 2016;87:370–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/asj.12428.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

41. Moate, PJ, Jacobs, JL, Hixson, JL, Deighton, MH, Hannah, MC, Morris, GL, et al.. Effects of feeding either red or white grape marc on milk production and methane emissions from early-lactation dairy cows. Animals (Basel) 2020;10:976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10060976.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

42. Al-Naqeep, G, Ismail, M, Al-Zubairi, A, Esa, N. Nutrients composition and minerals content of three different samples of Nigella sativa L. cultivated in Yemen. Asian J Biol Sci 2009;2:43–8. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajbs.2009.43.48.Search in Google Scholar

43. Pascual, JJ, Fernández, C, Dı́az, JR, Garcés, C, Rubert-Alemán, J. Voluntary intake and in vivo digestibility of different date-palm fractions by Murciano-Granadina (Capra hircus). J Arid Environ 2000;45:183–9.10.1006/jare.1999.0622Search in Google Scholar

44. Manh, N, Wanapat, M, Uriyapongson, S, Khejornsart, P, Chanthakhoun, V. Effect of eucalyptus (Camaldulensis) leaf meal powder on rumen fermentation characteristics in cattle fed on rice straw. Afr J Agric Res 2012;7:2142–8. https://doi.org/10.5897/ajar11.1347.Search in Google Scholar

45. Kondo, M, Hirano, Y, Kita, K, Jayanegara, A, Yokota, HO. Fermentation characteristics, tannin contents and in vitro ruminal degradation of green tea and black tea By-products ensiled at different temperatures. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2014;27:937–45. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2013.13387.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

46. Juráček, M, Vašeková, P, Massányi, P, Kováčik, A, Bíro, D, Šimko, M, et al.. The effect of dried grape pomace feeding on nutrients digestibility and serum biochemical profile of wethers. Agriculture 2021;11:1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11121194.Search in Google Scholar

47. Bouazza, L, Bodas, R, Boufennara, S, Bousseboua, H, López, S. Nutritive evaluation of foliage from fodder trees and shrubs characteristic of Algerian arid and semi-arid areas. J Anim Feed Sci 2012;21:521–36. https://doi.org/10.22358/jafs/66126/2012.Search in Google Scholar

48. Ahmed, SR, Roy, R, Romi, IJ, Hasan, M, Bhuiyan, MKH, Khan, MMH. Phytochemical screening, antioxidant and antibacterial activity of some medicinal plants grown in Sylhet region. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci 2019;14:26–37.Search in Google Scholar

49. Ku-Vera, JC, Jiménez-Ocampo, R, Valencia-Salazar, SS, Montoya-Flores, MD, Molina-Botero, IC, Arango, J, et al.. Role of secondary plant metabolites on enteric methane mitigation in ruminants. Front Vet Sci 2020;7:584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2020.00584.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Sarwar, GG, Wu Xiao, C, Cockell, KA. Impact of antinutritional factors in food proteins on the digestibility of protein and the bioavailability of amino acids and on protein quality. Br J Nutr 2012;108:S315–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114512002371.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

51. Bhatt, RS, Sahoo, A, Sarkar, S, Soni, L, Sharma, P, Gadekar, YP. Dietary supplementation of plant bioactive-enriched aniseed straw and eucalyptus leaves modulates tissue fatty acid profile and nuggets quality of lambs. Animal 2020;14:2642–51. https://doi.org/10.1017/s175173112000141x.Search in Google Scholar

52. Singh, AK. Evaluation of the antioxidant potential of oregano leaves (Origanum vulgare L.) and their effect on the oxidative stability of ghee. NUTRAfoods 2017;16:109–19.Search in Google Scholar

53. Samadi, S, Fatemeh, RF. Phytochemical properties, antioxidant activity and mineral content (Fe, Zn and Cu) in Iranian produced black tea, green tea and roselle calyces. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol 2020;23:101472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101472.Search in Google Scholar

54. Bendifallah, L, Tchoulak, Y, Djouabi, M, Oukili, M, Ghezraoui, R. Phytochemical study and antimicrobial activity of Origanum Vulgare L. (Lamiaceae) in Boumerdes mountainous Region (Algeria). J Med Biol Eng 2015;4:471–4. https://doi.org/10.12720/jomb.4.6.471-474.Search in Google Scholar

55. Abd, Q, Al-Samarrai, A, Al-Samarrai, R. Phytochemical constituents and nutrient evaluation of Origanum vulgare. TJPS 2017;22:114–9.10.25130/tjps.v22i4.741Search in Google Scholar

56. Wale, OA, Adewunmi, DG. Evaluation of nutritional and phytochemical properties of Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Hibiscus sabdariffa and Morinda lucida from Ogun State, Nigeria. J Stress Physiol Biochem 2020;16:45–56.Search in Google Scholar

57. Spanghero, M, Salem, AZM, Robinson, PH. Chemical composition, including secondary metabolites, and rumen fermentability of seeds and pulp of Californian (USA) and Italian grape pomaces. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2009;152:243–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2009.04.015.Search in Google Scholar

58. Milutinović, M, Vasić, S, Obradović, A, Zuher, A, Jovanović, M, Radovanović, M, et al.. Phytochemical evaluation, antimicrobial and anticancer properties of new “Oligo Grapes” supplement. Nat Prod Commun 2019;14:1934578X19860371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578x19860371.Search in Google Scholar

59. Khan, MMH, Chaudhry, AS. Chemical composition of selected forages and spices and the effect of these spices on in vitro rumen degradability of some forages. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2010;23:889–900. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2010.90442.Search in Google Scholar

60. Patra, A. Nutritional management in organic livestock farming for improved ruminant health and production-An overview. Livest Res Rural Dev 2007;19:41.Search in Google Scholar

61. Gerlach, K, Pries, M, Südekum, K-H. Effect of condensed tannin supplementation on in vivo nutrient digestibilities and energy values of concentrates in sheep. Small Rumin Res 2018;161:57–62.10.1016/j.smallrumres.2018.01.017Search in Google Scholar

62. Cabral Filho, SLS, Abdalla, AL, Bueno, ICS, Gobbo, S, Oliveira, A. Effect of sorghum tannins in sheep fed with high-concentrate diets. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec 2013;65:1759–66. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-09352013000600025.Search in Google Scholar

63. Besharati, M, Maggiolino, A, Palangi, V, Kaya, A, Jabbar, M, Eseceli, H, et al.. Tannin in ruminant nutrition: review. Molecules 2022;27:8273. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27238273.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

64. Ropiak, HM, Lachmann, P, Ramsay, A, Green, RJ, Mueller-Harvey, I. Identification of structural features of condensed tannins that affect protein aggregation. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170768. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170768.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

65. Hess, H, Monsalve, LM, Lascano, CE, Carulla, J, Diaz, T, Kreuzer, M. Supplementation of a tropical grass diet with forage legumes and Sapindus saponaria fruits: effects on in vitro ruminal nitrogen turnover and methanogenesis. Aust J Agric Res 2003;54:703–13. https://doi.org/10.1071/ar02241.Search in Google Scholar

66. Makkar, HP, Blümmel, M, Becker, K. In vitro effects of and interactions between tannins and saponins and fate of tannins in the rumen. J Sci Food Agric 1995;69:481–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.2740690413.Search in Google Scholar

67. Wallace, RJ, McEwan, NR, McIntosh, FM, Teferedegne, B, Newbold, CJ. Natural products as manipulators of rumen fermentation. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2002;15:1458–68. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2002.1458.Search in Google Scholar

68. Tilley, J, Terry, dR. A two‐stage technique for the in vitro digestion of forage crops. Grass Forage Sci 1963;18:104–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2494.1963.tb00335.x.Search in Google Scholar

69. Van Soest, P, Wine, R, Moore, L, editors. Estimation of the true digestibility of forages by the in vitro digestion of cell walls; 1966. pan: 19670700081item type: Conference proceedings Book.Search in Google Scholar

70. Tassone, S, Fortina, R, Peiretti, PG. In vitro techniques using the Daisy(II) incubator for the assessment of digestibility: a review. Animals (Basel) 2020;10:775. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10050775.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

71. Wilman, D, Adesogan, A. A comparison of filter bag methods with conventional tube methods of determining the in vitro digestibility of forages. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2000;84:33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0377-8401(00)00110-3.Search in Google Scholar

72. Vogel, KP, Pedersen, JF, Masterson, SD, Toy, JJ. Evaluation of a filter bag System for NDF, ADF, and IVDMD forage analysis. Crop Sci 1999;39:276–9. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1999.0011183x003900010042x.Search in Google Scholar

73. Adesogan, A, editor. What are feeds worth? A critical evaluation of selected nutritive value methods. In: Proceedings 13th annual Florida ruminant nutrition symposium; 2002.Search in Google Scholar

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/opag-2025-0476).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants

- Assessment of nutrition status of pineapple plants during ratoon season using diagnosis and recommendation integrated system

- Nutritional value and consumer assessment of 12 avocado crosses between cvs. Hass × Pionero

- The lacked access to beef in the low-income region: An evidence from the eastern part of Indonesia

- Comparison of milk consumption habits across two European countries: Pilot study in Portugal and France

- Antioxidant responses of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages

- Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

- Yield and vegetation index of different maize varieties and nitrogen doses under normal irrigation

- Urbanization and forecast possibilities of land use changes by 2050: New evidence in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam

- Organizational-economic efficiency of raspberry farming – case study of Kosovo

- Application of nitrogen-fixing purple non-sulfur bacteria in improving nitrogen uptake, growth, and yield of rice grown on extremely saline soil under greenhouse conditions

- Digital motivation, knowledge, and skills: Pathways to adaptive millennial farmers

- Investigation of biological characteristics of fruit development and physiological disorders of Musang King durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.)

- Enhancing rice yield and farmer welfare: Overcoming barriers to IPB 3S rice adoption in Indonesia

- Simulation model to realize soybean self-sufficiency and food security in Indonesia: A system dynamic approach

- Gender, empowerment, and rural sustainable development: A case study of crab business integration

- Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses of bacterial communities in short mackerel (Rastrelliger brachysoma) under storage conditions and inoculation of the histamine-producing bacterium

- Fostering women’s engagement in good agricultural practices within oil palm smallholdings: Evaluating the role of partnerships

- Increasing nitrogen use efficiency by reducing ammonia and nitrate losses from tomato production in Kabul, Afghanistan

- Physiological activities and yield of yacon potato are affected by soil water availability

- Vulnerability context due to COVID-19 and El Nino: Case study of poultry farming in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Wheat freshness recognition leveraging Gramian angular field and attention-augmented resnet

- Suggestions for promoting SOC storage within the carbon farming framework: Analyzing the INFOSOLO database

- Optimization of hot foam applications for thermal weed control in perennial crops and open-field vegetables

- Toxicity evaluation of metsulfuron-methyl, nicosulfuron, and methoxyfenozide as pesticides in Indonesia

- Fermentation parameters and nutritional value of silages from fodder mallow (Malva verticillata L.), white sweet clover (Melilotus albus Medik.), and their mixtures

- Five models and ten predictors for energy costs on farms in the European Union

- Effect of silvopastoral systems with integrated forest species from the Peruvian tropics on the soil chemical properties

- Transforming food systems in Semarang City, Indonesia: A short food supply chain model

- Understanding farmers’ behavior toward risk management practices and financial access: Evidence from chili farms in West Java, Indonesia

- Optimization of mixed botanical insecticides from Azadirachta indica and Calophyllum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda using response surface methodology

- Mapping socio-economic vulnerability and conflict in oil palm cultivation: A case study from West Papua, Indonesia

- Exploring rice consumption patterns and carbohydrate source diversification among the Indonesian community in Hungary

- Determinants of rice consumer lexicographic preferences in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

- Effect on growth and meat quality of weaned piglets and finishing pigs when hops (Humulus lupulus) are added to their rations

- Healthy motivations for food consumption in 16 countries

- The agriculture specialization through the lens of PESTLE analysis

- Combined application of chitosan-boron and chitosan-silicon nano-fertilizers with soybean protein hydrolysate to enhance rice growth and yield

- Stability and adaptability analyses to identify suitable high-yielding maize hybrids using PBSTAT-GE

- Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-mediated rock phosphate utilization with poultry manure enhances soil nutrient dynamics and maize growth in semi-arid soil

- Factors impacting on purchasing decision of organic food in developing countries: A systematic review

- Influence of flowering plants in maize crop on the interaction network of Tetragonula laeviceps colonies

- Bacillus subtilis 34 and water-retaining polymer reduce Meloidogyne javanica damage in tomato plants under water stress

- Vachellia tortilis leaf meal improves antioxidant activity and colour stability of broiler meat