Bacillus subtilis 34 and water-retaining polymer reduce Meloidogyne javanica damage in tomato plants under water stress

-

Maria Josiane Martins

, Regina Cássia Ferreira Ribeiro

Abstract

Combining the water deficit of Meloidogyne javanica poses a challenge for tomato production. The objective of this study was to assess the effects of combining Bacillus subtilis 34 (BS34) and water-retaining polymer (WRP) on the control of M. javanica in tomato crops under water-deficit conditions. The experiment was conducted in a randomized block design with eight replications, using a 4 × 5 factorial arrangement consisting of four growing environments with different applications of BS 34 and WRP (control, WRP alone, BS34 alone, and BS34 + WRP) and five soil water tensions (10, 25, 40, 55, and 70 kPa). Agronomic and nematological variables were evaluated 65 days after transplanting. The application of WRP + BS34 improved the environmental conditions for tomato plant development, regardless of soil water tension. The treatments with WRP + BS34 and BS34 alone resulted in effective control of M. javanica. Soil water tensions exceeding 10 kPa reduced tomato plant development.

1 Introduction

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is among the main vegetable crops grown worldwide. Tomato crop areas reached 5 million hectares in 2020, with an average production of 187 million Mg [1]. The world’s largest tomato-producing countries are China, USA, India, Turkey, Egypt, Italy, Iran, Spain, and Brazil [1]. Tomato is grown in approximately 52,000 hectares in Brazil, where the main producing states are Goiás, São Paulo, and Minas Gerais [2]. In Minas Gerais, tomato crops are concentrated in the regions of Jaíba, Araguari, and Patos de Minas [3]. Despite the low rainfall conditions, the average yield in the Jaíba region, northern Minas Gerais, reached 73.63 Mg ha−1 [3] when grown under irrigation.

Water deficit can cause morphological, biochemical, and physiological disorders, affecting vital cellular processes and resulting in crop yield losses [4]. Damage to the photosynthetic apparatus and oxidative injuries to proteins and lipids in cell membranes are among the deleterious effects of drought on tomato plants [5]. Several studies have reported that decreases in tomato crop yield are directly proportional to reductions in water use efficiency (WUE) [6,7]. Therefore, formulating strategies for improving WUE in tomato plants is essential.

Root-knot nematodes of the genus Meloidogyne can infect a wide range of host plants worldwide. The species M. incognita and M. javanica are among the main plant parasitic nematodes [8]. Parasitism of Meloidogyne species has resulted in annual losses of approximately $70 billion [9]. Yield losses in tomato crops range from 25 to 100%, depending on the Meloidogyne species infesting the crop, population density, and tomato cultivar [10].

Parasitism of M. javanica in tomato roots may also cause plant wilting, and the same symptom results from the plant’s response to water deficit. Meloidogyne species are sedentary endoparasites that infect plant roots and establish feeding sites (giant cells) within the vascular cylinder, causing parenchyma cells to become multinucleated [11]. These cells provide water and nutrients to the nematode during its life cycle [12]. Simultaneously with the formation of giant cells, parenchyma cells undergo hyperplasia, resulting in the formation of galls on the roots.

The use of specific bacteria has shown positive effects on nematode control in recent decades. Studies have shown that Bacillus subtilis has an important function in controlling M. javanica and promoting tomato plant growth [13,14]. B. subtilis regulates nematode behavior by competing for nutrients and interfering with host recognition [15]. Additionally, B. subtilis can maintain this nematicidal effect even under high temperatures, making it a potential biocontrol agent for use in greenhouse vegetable growing to suppress M. javanica populations.

Water-retaining polymers (WRPs) absorb, store, and release water molecules [16]. They are used in arid and semiarid regions to mitigate negative impacts of water deficit and improve WUE, consequently contributing to plant growth. Although the use of B. subtilis or WRPs may improve plant performance under drought conditions, no information on the effects of combining these two techniques is currently found in the literature.

Considering that water stress and parasitism of Meloidogyne spp. can cause damage and losses to tomato crops and the lack of information on combining WRPs and rhizobacteria to control phytonematodes, the objective of this study was to assess the effects of the combined application of Bacillus subtilis 34 (BS34) and WRP on the control of Meloidogyne javanica in tomato crops under water-deficit conditions.

2 Materials and methods

Experiments were conducted at Hydraulic and Phytopathology Laboratories and in a greenhouse of the State University of Montes Claros, Janaúba campus, Minas Gerais, Brazil (15°49′47″S, 43°16′05″W, and altitude of 533 m). Seedlings were produced by planting three tomato seeds (Santa Cruz group, cultivar Kada Gigante) in plastic trays filled with a commercial substrate (Bioplant®). Thinning was performed after plant emergence, leaving one plant per cell.

Bacillus subtilis isolate 34 (BS34) (isolated from banana roots in an area infested with Panama disease) was cultured in a rice medium following the methodology described by Lopes et al. [13]. A 100 µL of bacterial suspension stored in saline solution at room temperature was added to 300 mL glass flasks containing 50 mL of rice medium for inoculation. These flasks were kept under shaking (220 rpm) on an orbital shaker at 28°C for 32 h to reach a concentration of 6.14 × 108 CFU mL−1 [14].

Tomato seedlings of the Santa Cruz group, cultivar Kada Gigante, were transplanted to 3 dm3 pots containing autoclaved sandy soil 21 days after sowing. The treatments with WRP contained 50 g of a WRP (Polyter®) placed in the planting hole before transplanting the seedlings. Five grams of the product were immersed in 1 L of distilled water for 7 h for hydration. The treatments with BS34 consisted of 50 mL of the bacterial suspension applied to the soil around the seedling at 7, 9, and 11 days after transplanting (DAT); 50 mL of distilled water was applied to plants in the control treatment.

The species-level identification of M. javanica was performed based on the phenotypes of the esterase enzyme. The plant parasitic nematode was cultivated on Santa Cruz tomato plants, cultivar Kada Gigante, for 3 months. After this period, eggs were extracted from the roots according to the methodology of Hussey and Barker [21], modified by Boneti and Ferraz [22]. Subsequently, 7.5 mL of an aqueous suspension containing 5,000 eggs and possible second-stage juveniles (J2) of M. javanica was applied at 10 DAT. The nematode suspension was applied to three holes around each tomato plant at a depth of approximately 3 cm. Control treatment plants were treated with 7.5 mL of distilled water.

The seedlings were maintained under soil moisture corresponding to field capacity (10 kPa) until 15 DAT. Then, they were subjected to different soil water tensions (10, 25, 40, 55, and 70 kPa) through irrigation, maintaining the soil moisture at field capacity. Irrigation was based on readings of soil water tension twice a day (07 and 17 h) in each treatment, using tensiometers installed in the pots. Tension readings were converted to matric potential and then used in the soil water retention equation (Figure 1) to calculate the soil moisture level.

Soil water retention curve.

These soil moisture levels and soil volume in the pots were used to calculate the daily water volume to be applied [17]; the water volumes applied to each experimental unit during the experiment were recorded.

The following agronomic variables were assessed at 65 DAT: shoot and root fresh weights (RFWs), shoot dry weight, carotenoid content, chlorophyll a and b contents, and WUE. Fresh and dry weights were measured on a digital scale (Balmak®); fresh weight was determined immediately after harvesting; the material was then dried in an air oven at 65°C until constant weight to obtain the dry weight. Contents of chlorophyll a and b and carotenoids were analyzed following the methodology proposed by Scopel et al. [18] and adjusted using the equation described by Arnon [19]. WUE was calculated by determining the ratio between shoot dry weight (g) and water consumption (L).

Regarding the nematode evaluation, galls, egg masses, eggs per gram of root, and J2 per 200 cm3 of soil were counted; the reproduction factor (RF) was determined using the formula RF = (final population/initial population/number of egg masses + J2 applied to the soil). Egg masses were counted after washing the roots in running water and immersing them in a phloxine B solution (15 mg L−1) [20]. Eggs were extracted using the technique described by Hussey and Barker [21] modified by Boneti and Ferraz [22]; J2 was extracted from the soil using the technique described by Jenkins [23]. Egg suspensions and J2 of M. javanica were placed in a counting chamber and counted under an inverted microscope.

The experiment was conducted in a randomized block design with eight replications, using a 4 × 5 factorial arrangement consisting of four growing environments with different applications of BS34 and WRP (control, WRP alone, BS34 alone, and BS34 + WRP) and five soil water tensions (10, 25, 40, 55, and 70 kPa). The obtained data were subjected to analysis of variance at a 5% significance level using the F-test. Soil water tension data were subjected to regression analysis, and the mean values obtained for BS34 and WRP applications were compared using Tukey’s test. All statistical analyses were performed using the R software [24].

3 Results

The effect of the interaction between the growing environment (applications of BS34 and WRP) and soil water tension was significant for the following tomato agronomic variables: shoot fresh and dry weights, RFW, chlorophyll a and b contents, carotenoid content, and WUE (p < 0.05; Table 1). All treatments resulted in increased shoot fresh weight (SFW) compared to the control treatment, regardless of soil water tension.

Effect of growing environments within different soil water tensions on shoot fresh and dry weights of tomato plants grown in soils subjected to the application of WRP and BS34

| Growing environment | Soil water tension (kPa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 25 | 40 | 55 | 70 | |

| Shoot fresh weight (g plant −1 ) | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 256.37a | 254.50a | 244.50a | 239.12a | 231.50a |

| BS34 | 248.12b | 243.00a | 243.00a | 236.12ab | 229.50a |

| WRP | 243.25b | 236.12b | 236.12b | 233.12b | 226.37a |

| Control treatment | 213.12c | 206.37c | 206.37c | 195.37c | 187.00b |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 11.9 | ||||

| Shoot dry weight (g plant −1 ) | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 35.87a | 35.25a | 31.50a | 30.62a | 27.75a |

| BS34 | 33.25b | 32.37b | 29.62b | 28.37b | 26.25a |

| WRP | 30.37c | 28.00c | 27.62c | 25.87c | 23.50b |

| Control treatment | 29.37c | 26.75d | 22.50d | 18.75d | 17.00c |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 14.92 | ||||

Means followed by the same letter in the columns are not significantly different from each other by using Tukey’s test at a 5% significance level.

The application of BS34 + WRP and BS34 alone to the soil at water tensions of 25, 40, and 55 kPa resulted in SFW. Treatments with the application of BS34 and WRP at a soil water tension of 10 kPa resulted in similar SFW. Applications of BS34 + WRP, BS34, and WRP at a soil water tension of 70 kPa resulted in similar SFW (Table 1). Tomato plants under application of BS34 + WRP at soil water tensions of 10, 25, 40, and 55 kPa resulted in higher shoot dry weights (SDW). BS34 applied alone resulted in higher SDW compared to the application of WRP and the control treatment, regardless of soil water tension (Table 1).

RFW was higher when applying BS34 + WRP to the soil, regardless of soil water tension (Table 2). BS34 applied alone resulted in higher RFW compared to the application of WRP and the control treatment, regardless of soil water tension. However, WRP applied alone yielded higher RFW means at soil water tensions of 10, 40, 55, and 70 kPa than the control treatment (Table 2). BS34 + WRP and BS34 alone at soil water tensions of 10 and 25 kPa resulted in higher chlorophyll a contents. WRP applied alone at soil water tensions of 40, 55, and 70 kPa resulted in higher chlorophyll contents than the control treatment (Table 2). Applying BS34 + WRP and BS34 alone at a soil water tension of 25 kPa resulted in higher chlorophyll b contents. Regarding the other soil water tensions, BS34 + WRP yielded better results. The application of WRP alone and the control treatment at soil water tensions of 10, 25, 40, and 55 kPa resulted in similar chlorophyll b contents (Table 2).

Effect of growing environments within different soil water tensions on RFW, chlorophyll a and b contents, carotenoid content, and WUE in tomato plants grown in soils subjected to the application of WRP and BS34

| Growing environment | Soil water tension (kPa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 25 | 40 | 55 | 70 | |

| Root fresh weight (g plant −1 ) | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 862.25a | 852.37a | 833.12a | 822.75a | 808.25a |

| BS34 | 849.12b | 822.74b | 808.12b | 744.50b | 718.12b |

| WRP | 668.87c | 615.50c | 590.75c | 556.75c | 527.62c |

| Control treatment | 630.50d | 614.62c | 557.25d | 514.00d | 509.62d |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 11.19 | ||||

| Chlorophyll a content (µg cm −2 ) | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 81.63a | 81.25a | 78.40a | 76.38a | 75.68a |

| BS34 | 79.51a | 78.92a | 74.42b | 73.43b | 71.65b |

| WRP | 76.13b | 74.17b | 71.55b | 68.12c | 65.46c |

| Control treatment | 73.92b | 71.32b | 66.20c | 63.42d | 61.15d |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 23.04 | ||||

| Chlorophyll b content (µg cm −2 ) | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 14.05a | 12.46a | 11.00a | 10.38a | 9.97a |

| BS34 | 12.67ab | 12.32a | 10.01b | 9.03b | 8.51b |

| WRP | 12.96bc | 12.22ab | 9.33bc | 8.91b | 8.06b |

| Control treatment | 12.32c | 11.43b | 9.10c | 8.45b | 7.00c |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 15.76 | ||||

| Carotenoid content (µg cm −2 ) | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 5.47a | 6.20a | 6.70a | 7.15a | 7.28a |

| BS34 | 9.11b | 9.17b | 9.41b | 9.72b | 9.88b |

| WRP | 10.62c | 10.66c | 11.01c | 11.37c | 11.83c |

| Control treatment | 10.66c | 10.71d | 11.12c | 11.93d | 12.07c |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 13.39 | ||||

| Water use efficiency (g L −1 ) | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 3.12a | 3.52a | 3.76a | 4.70a | 4.76a |

| BS34 | 2.58b | 2.44b | 2.80b | 3.12b | 3.56b |

| WRP | 2.08c | 2.31b | 2.39c | 2.86c | 3.29c |

| Control treatment | 1.64d | 1.55c | 1.52d | 1.47d | 1.39d |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 15.01 | ||||

Means followed by the same letter in the columns are not significantly different from each other by using Tukey’s test at a 5% significance level.

Carotenoid contents were higher in control treatment at soil water tensions of 25, 40, 55, and 70 kPa. The lowest carotenoid contents were found for BS34 + WRP, regardless of the soil water tension. BS34 applied alone resulted in lower carotenoid content than WRP applied alone (Table 2).

WUE was higher when applying BS34 + WRP, regardless of the soil water tension. Treatments with BS34 + WRP, BS34, and WRP, and the control treatment at a soil water tension of 10 kPa yielded 3.12, 2.58, 2.08, and 1.64 g of SDW, respectively, for each liter of water. BS34 applied alone at soil water tensions of 10, 40, 55, and 70 kPa resulted in a higher WUE than applying WRP alone; however, WRP alone yielded higher WUE than the control treatment, regardless of the soil water tension (Table 2).

SFW decreased as the soil water tension was increased, regardless of the growing environment (Figure 2). SFW decreased by 0.4342 g for each 1 kPa increase in the soil water tension when BS34 + WRP was applied. The smallest decrease (0.2617 g) was found when applying WRP alone. Applying BS34 alone resulted in a decrease of 0.3217 g, whereas the control treatment resulted in a higher decrease (0.4533 g). Treatments with BS34 alone resulted in a 0.35% decrease in SFW from the soil water tension of 10 to 25 kPa. The decreases in SFW found for BS34 + WRP, control treatment, and WRP alone were 0.73, 0.94, and 1.94%, respectively.

Shoot fresh weight of tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level using the t-test.

SDW decreased by 0.1392 g for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension when applying BS34 + WRP (Figure 3). When applied alone, BS34 and WRP resulted in decreases of 0.12 and 0.1058 g in SDW, respectively. The control treatment resulted in a decrease of 0.2183 g for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension. SDW decreased by 1.75% from the soil water tension of 10–25 kPa when BS34 + WRP was applied and decreased by 29% from the lowest to the highest soil water tension (10–70 kPa).

Shoot dry weight of tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level by using the t-test.

RFW decreased by 0.9175 g for each 1 kPa increase in the soil water tension when applying BS34 + WRP (Figure 4). When applied alone, BS34 and WRP resulted in decreases of 2.2683 and 2.2750 g in RFW, respectively. The control treatment resulted in a decrease of 2.2825 g for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension. RFW decreased by 1.59% and 3.20% from the soil water tension of 10–25 kPa when applying BS34 + WRP and BS34 alone, respectively, and decreased by 2.58% (control treatment) and 8.67% (WRP applied alone).

Root fresh weight of tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level by using the t-test.

Chlorophyll a content decreased by 0.1118 µg cm−2 for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension when applying BS34 + WRP (Figure 5). When applied alone, BS34 and WRP resulted in decreases of 0.1414 and 0.1827 µg cm−2, respectively. The control treatment resulted in a decrease of 0.2230 µg cm−2 for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension (Figure 5). Chlorophyll a content decreased by 0.46, 0.74, and 2.64% from the soil water tension of 10–25 kPa when applying BS34 + WRP, BS34, and WRP, respectively, and decreased by 3.64% in the control treatment.

Chlorophyll a content in tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level using the t-test.

Chlorophyll b content decreased by 0.0682 µg cm−2 for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension when applying BS34 + WRP (Figure 6). When applied alone, BS34 and WRP resulted in decreases of 0.0901 and 0.0881 µg cm−2, respectively. The control treatment resulted in a decrease of 0.0909 µg cm−2 for each 1 kPa increase in the soil water tension (Figure 6).

Chlorophyll b content in tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level using the t-test.

Carotenoid content increased by 0.0305 µg cm−2 for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension when BS34 + WRP was applied (Figure 7). WRP applied alone, and the control treatment resulted in increases of 0.0209 and 0.0270 µg cm−2, respectively. The lowest increase in the carotenoid content (0.014 µg cm−2) was found when applying BS34 alone.

Carotenoid contents in tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level by the t-test.

WUE increased by 0.0298 g L−1 for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension when applying BS34 + WRP (Figure 8). When applied alone, BS34 and WRP resulted in increases of 0.0198 and 0.0176 g L−1, respectively. However, the control treatment resulted in a decrease of 0.0039 g L−1 in WUE for each 1 kPa increase in the soil water tension.

Water use efficiency in tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level using the t-test.

Regarding the control of Meloidogyne javanica, the interaction effect between the factors (growing environment and soil water tension) was significant for the following nematode variables: number of galls, number of egg masses, number of eggs per gram of root, and reproduction factor (Table 3). All treatments resulted in decreased numbers of galls and egg masses per gram of root compared to the control treatment, regardless of the soil water tension. Considering the soil water tension of 10 kPa, the highest decreases in the number of galls per gram of root were found for BS34 + WRP treatment (82.52%), followed by BS34 (74.82%) and WRP (10.49%) treatments, and the highest decreases in number of egg masses per gram of root were found for BS34 + WRP (80.69%), followed by BS34 (66.90%) and WRP (13.10%).

Effect of growing environments within different soil water tensions on the number of galls, number of egg masses, and number of eggs of Meloidogyne javanica per gram of root of tomato plants grown in soil subjected to application of WRP and BS34

| Growing environment | Soil water tension (kPa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 25 | 40 | 55 | 70 | |

| Number of galls per gram of root | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 0.050a | 0.052a | 0.057a | 0.060a | 0.063a |

| BS34 | 0.072b | 0.083b | 0.092b | 0.101b | 0.105b |

| WRP | 0.256c | 0.286c | 0.310c | 0.346c | 0.378c |

| Control treatment | 0.286d | 0.316d | 0.362d | 0.400d | 0.412d |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 33.36 | ||||

| Number of egg masses per gram of root | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 0.028a | 0.031a | 0.049a | 0.059a | 0.068a |

| BS34 | 0.048b | 0.059b | 0.067b | 0.081b | 0.088b |

| WRP | 0.126c | 0.144c | 0.166c | 0.182c | 0.196c |

| Control treatment | 0.145d | 0.155d | 0.183d | 0.243d | 0.252d |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 26.36 | ||||

| Number of eggs per gram of root | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 1.15a | 1.18a | 1.57a | 2.70a | 3.79a |

| BS34 | 1.83a | 2.18a | 2.31a | 2.76a | 4.28a |

| WRP | 21.60b | 24.47b | 35.05b | 41.64b | 47.72b |

| Control treatment | 31.27b | 40.31c | 53.14c | 60.42c | 69.11c |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 34.64 | ||||

| Reproduction factor | |||||

| BS34 + WRP | 0.18a | 0.18a | 0.24a | 0.37a | 0.57a |

| BS34 | 0.29a | 0.33a | 0.35a | 0.42a | 0.57a |

| WRP | 2.70b | 3.27b | 3.87b | 4.32b | 4.71b |

| Control treatment | 3.68b | 4.63c | 5.52c | 5.80c | 6.58c |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 32.76 | ||||

Means followed by the same letter in the columns are not significantly different from each other by using Tukey’s test at a 5% significance level.

The number of eggs per gram of root varied among the growing environments. The control treatment showed a higher number of eggs, regardless of the soil water tension. Applications of BS34 + WRP and BS34 alone resulted in a lower number of eggs (Table 3). Considering the soil water tension of 10 kPa, the treatments with BS34 + WRP and BS34 alone resulted in decreases greater than 90% in the reproduction factor compared to the control treatment. Regarding the other water tensions, all treatments resulted in a decreased reproduction factor (Table 3).

The application of BS34 + WRP increased to 0.0002 galls g−1 for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension (Figure 9). When applied alone, BS34 and WRP resulted in increases of 0.0006 and 0.0020 galls g−1, respectively, whereas the control treatment increased to 0.0022 galls g−1 (Figure 9). BS34 + WRP and BS34 alone increased to 0.0007 egg masses g−1 for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension (Figure 10). WRP applied alone increased to 0.0012 egg masses g−1, whereas the highest increase (0.0020 egg masses g−1) was found for the control treatment. Egg masses increased by 9.67 and 12.5% from the soil water tension of 10–25 kPa when applying BS34 + WRP and WRP alone, respectively.

Number of galls per gram of root of tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level by using the t-test.

Number of egg masses of Meloidogyne javanica per gram of root of tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level by the t-test.

BS34 + WRP and BS34 alone resulted in increases of 0.04575 and 0.036158 eggs g−1, respectively, for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension (Figure 11). WRP applied alone increased to 0.04360 eggs g−1, whereas the control treatment resulted in the highest increase (0.6385 eggs g−1). The number of eggs increased by 2.54 and 22.42% from the soil water tension of 10–25 kPa for the application of BS34 + WRP and the control treatment, respectively (Figure 11).

Number of eggs of Meloidogyne javanica per gram of root of tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level by using the t-test.

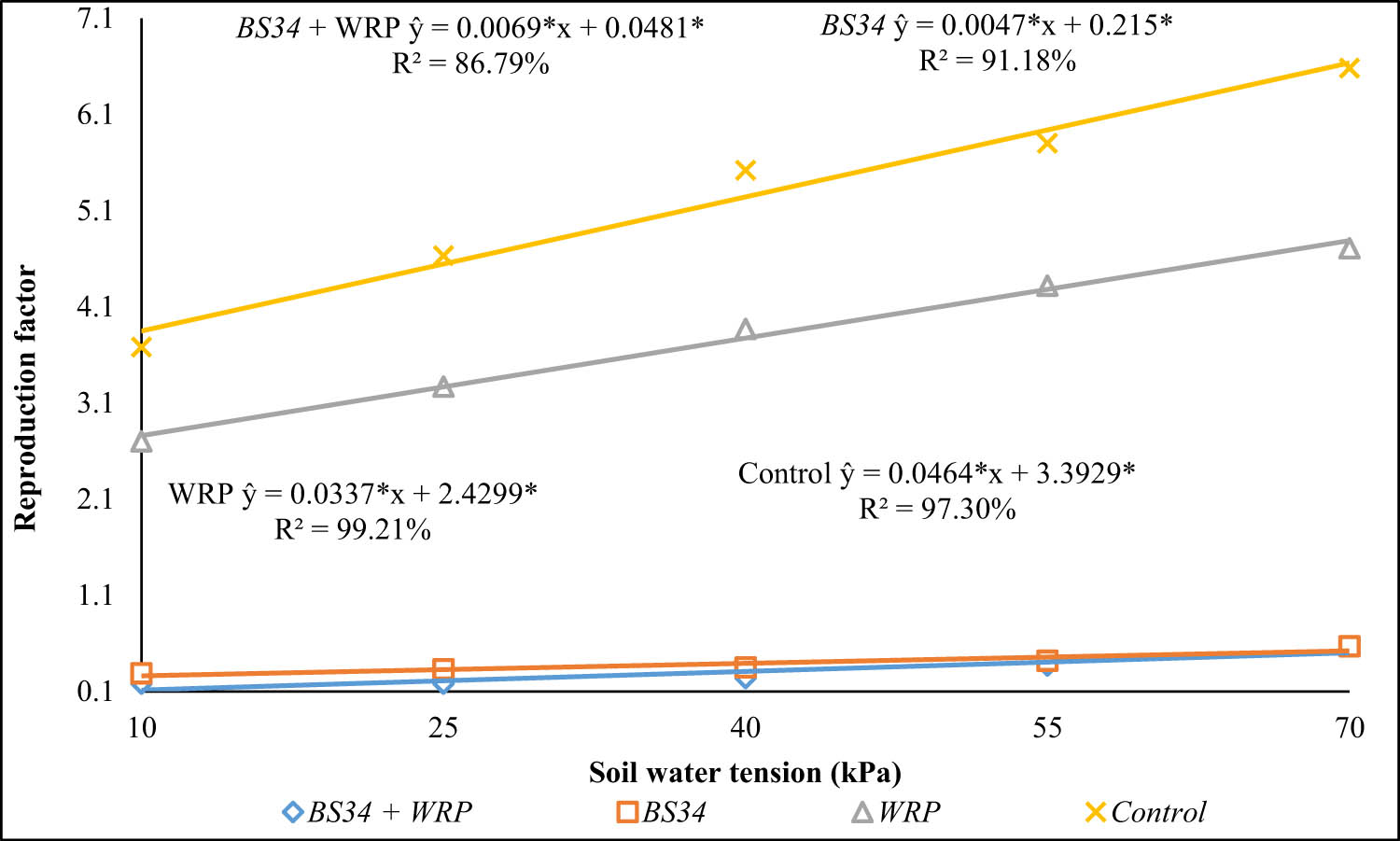

The reproduction factor increased by 0.0069 and 0.0047 when applying BS34 + WRP and BS34 alone, respectively, for each 1 kPa increase in soil water tension (Figure 12). WRP alone increased to 0.0337, whereas the control treatment resulted in the highest increase (0.0464) in the reproduction factor (Figure 12).

Reproduction factor for Meloidogyne javanica in tomato plants grown under different soil water tensions and application of WRP and BS34 to the soil. *Significant at a 5% significance level by the t-test.

The interaction effect was not significant for the number of second-stage juveniles (J2) of M. javanica in the soil (p > 0.05); therefore, the individual effects of the factors were assessed (Table 4; Figure 13). The lowest numbers of J2 were found for BS34 and BS34 + WRP. The treatment with the application of WRP alone did not differ from the control treatment (Table 4). The number of J2 increased by 0.7346 for each 1 kPa increase in the soil water tension (Figure 13).

Number of second-stage juveniles (J2) of Meloidogyne javanica in soil cultivated with tomato plants as a function of different growing environments

| Growing environment | Number of J2 of M. javanica |

|---|---|

| BS34+ WRP | 110.85a |

| BS34 | 107.9a |

| WRP | 152.95b |

| Control treatment | 160.65b |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 35.07 |

Means followed by the same letter in the columns are not significantly different from each other by using Tukey’s test at a 5% significance level.

Number of second-stage juveniles (J2) of Meloidogyne javanica as a function of different soil water tensions. *Significant at a 5% significance level by using the t-test.

4 Discussion

The combined application of BS34 and a WRP), overall improved the development of tomato plants, regardless of soil water tension, as the results found for the evaluated agronomic variables were better compared to the control treatment (Tables 1 and 2). The use of BS34 can stimulate plant growth through solubilization of phosphate, nitrogen fixation, and production of indole-3-acetic acid, siderophores, and phytohormones [25,26,27].

The control of Meloidogyne javanica may have indirectly promoted the growth of tomato plants due to several factors. The B. subtilis isolates used in the present study showed promising results for controlling M. javanica and M. incognita in other crops [14,15,28,29,30]).

WRP can store large amounts of water and release it to plants as the soil dries, promoting a favorable microclimate for microbial activity [31]. The application of BS34 + WRP increased RFW as the soil water tension was increased compared to the control treatment (Table 2). RFW increased by 36.75, 38.68, 49.50, 60.07, and 59.00% for soil water tensions of 10, 25, 40, 55, and 70 kPa, respectively.

The water released by polymers mitigates water stress in plants. WRPs become highly hydrophilic in the soil, as they have carboxylic groups that facilitate water retention and subsequent release of water to plants [32,33], mitigating the effects of droughts, mainly in sandy soils in arid and semiarid regions [34]. Increasing water availability by applying WRP protects the root system against dehydration, reduces nutrient leaching, and improves soil aeration and drainage, thus contributing to root and shoot development [35,36,37].

The application of BS34 may have produced compounds that contributed to the development of tomato plants. B. subtilis not only mobilizes nutrients but also produces a wide range of compounds that directly affect plant growth, as it can alter the homeostasis of plant growth hormones, promoting cell division and plant growth [38].

Normal plant growth depends on maintaining a balance in water metabolism, as the main challenge for plant survival is the soil water content. The application of WRP to the soil reduced the stress caused by water deficit in the evaluated tomato plants, probably due to increased soil water availability, as WUE was higher in plants subjected to the combined application of WRP and bacteria (Table 2; Figure 8). The plants utilized 1 L of water to produce 3.12 g of dry matter when BS34 and WRP were applied to the soil and 1 liter of water to produce 1.64 g of dry matter in the control treatment.

Photosynthetic pigment contents, such as chlorophylls, in tomato plants can affect the amount of radiation absorbed by the plant during its development. The negative results found for pigments in treatments with high soil water tensions and the absence of BS34 or WRP resulted in lower dry weights. Tomato plants grown under the application of BS34 + WRP presented higher chlorophyll a and b contents, which resulted in better vegetative development (Table 2; Figures 5 and 6).

Carotenoid contents increased as the water deficit was increased (increases in soil water tension), regardless of the growing environment (Figure 7). This may be attributed to a plant strategy to minimize damage to the photosynthetic apparatus, as carotenoids act as a filter of ultraviolet radiation, absorbing visible radiation and providing photoprotection by rapidly quenching the excitation of chlorophyll, thus preventing photooxidation [39].

The numbers of galls, egg masses, and eggs per gram of root, the number of J2 in the soil, and the reproduction factor of M. javanica increased as the soil water tension was increased (Table 3; Figure 13); this may be attributed to decreases in the root system development caused by water deficit, resulting in higher numbers per gram of root. These results are consistent with those reported by Khanizadeh et al. [40], who found higher reproduction of M. hapla in strawberry plants for the highest evaluated water deficit.

The reproduction factor of M. javanica, which represents the nematode reproductive capacity, was less than 1 when applying BS34 + WRP or BS34 alone, regardless of soil water tension. This is a similar result to that found for plants resistant to this nematode [41]. The application of BS34 controlled the development of M. javanica (Table 3; Figure 12). Nematicidal activity of B. subtilis has been reported in other studies [13,14,42]. B. subtilis damages Meloidogyne spp. by regulating their behavior, competing for nutrients, and interfering with host recognition [43]. Furthermore, B. subtilis can maintain the nematicidal effect, even under high temperatures, explaining the reduction of M. javanica when applying BS34 + WRP, even at high soil water tensions.

During the infective stage (J2), approximately 30% of the body weight of M. javanica consists of lipids, which are the main energy source used during the penetration and parasitism of the host [44]. BS34 has been described as a lipase producer [45]. Lipase enzymes degrade lipid molecules in nematodes. Lipases have an important function in controlling M. javanica by degrading its energy reserves and acting on lipid membranes [46]. This may explain the low parasitism of M. javanica in tomato plants grown in soils subjected to the application of BS34.

Lipids are essential for the survival of phytonematodes. Additionally, decreases in lipid reserves are associated with reduced infectivity and motility and delayed juvenile development [47]. Lipid losses in M. javanica can affect the nematode infectivity, resulting in its death. Losses of 50–60% in lipid reserves in Meloidogyne species result in loss of infectivity for the nematode [48].

5 Conclusions

The combined application of BS34 and a WRP to the soil improves plant growth and results in efficient control of Meloidogyne javanica nematodes in tomato plants grown under soil water tensions of 10, 25, 40, 55, and 70 kPa.

Water deficit increases M. javanica population. Soil water tensions higher than 10 kPa decrease tomato plant development.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Brazilian Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) (funding code 001), the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and the Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation (FAPEMIG) for granting graduate and undergraduate research scholarships.

-

Funding information: This work was funded by Capes, CNPq, and FAPEMIG.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors edited manuscript. MJM and RCFR wrote the paper and conceived the study. SRS and AAX collected and analyzed samples. MJM, RCFR, and SRS conducted statistical analyses. CARM, LGAS, RMA, ICCB, and EHM provided access to long-term experiments, guidance on experimental protocol, and contributed with data.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the study are available in the Postgraduate program in Plant Production in the Semiarid Region repository [https://producaovegetal.com.br/download-category/fitopatologia/].

References

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT. Crops and livestock products, tomatoes. Disponível em: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize. Accessed September 28, 2022.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento. CONAB. Tomate: Análise dos Indicadores da Produção e Comercialização no Mercado Mundial, Brasileiro e Catarinense. Compêndio de estudos Conab. Brasília: Compêndio Estudos, v21. 2019. p. 1–21.Suche in Google Scholar

[3] SEAPA- Secretaria de Estado de Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento. Balanço do agronegócio em Minas Gerais. Belo Horizonte: SEAPA; 2020. p. 1–50.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Pereira SIA, Abreu O, Moreira H, Vega A, Castro PML. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) improve the growth and nutrient use efficiency in maize (Zea mays L.) under water deficit conditions. Heliyon. 2020;6:e05106. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05106.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Huseynova IM, Rustamova SM, Suleymanov SY, Aliyeva DR, Mammadov AC, Aliyev JA. Drought-induced changes in photosynthetic apparatus and antioxidant components of wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) varieties. Photosynth Res. 2016;130:215–23. 10.1007/s11120-016-0244-z.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Khapte PS, Kumar P, Burman U, Kumar P. Deficit irrigation in tomato: Agronomical and physio-biochemical implications. Sci Hortic. 2019;248:256–64. 10.1016/j.scienta.2019.01.006.Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Medyouni I, Zouaoui R, Rubio E, Serino S, Ahmed HB, Bertin N. Effects of water deficit on leaves and fruit quality during the development period in tomato plant. Food Sci Nutr. 2021;9:1949–60. 10.1002/fsn3.2160.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Jones JT, Haegema A, Danchin EJ, Gaur HS, Helder J, Jones MGK, et al. Top 10 plant-parasitic nematodes in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol. 2013;14(9):946–61. 10.1111/mpp.12057.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Abdelsamad N, Regmi H, Desaeger J, Digermano P. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide induced resistance against root-knot nematode Meloidogyne hapla is based on increased tomato basal defense. J Nematol. 2019;51:1–10. 10.21307/jofnem-2019-022. e2019-22.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Seid A, Fininsa C, Mekete T, Decraeme RW, Wesemael WML. Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) – a century-old battle. Nematology. 2015;17:995–1009. 10.1163/15685411-00002935.Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Veronico P, Paciolla C, Pomar F, Leonardish S, Ulloa AG, Melillo MT. Changes in lignin biosynthesis and monomer composition in response to benzothiadiazole and root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita infection in tomato. J Plant Physiol. 2018;230:40–50. 10.1016/j.jplph.2018.07.013.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Xiao K, Chem W, Chen X, Zu X, Guan P, Hu J. CCS52 and DEL1 function in root-knot nematode giant cell development in Xinjiang wild myrobalan plum (Prunus sogdiana Vassilcz). Protoplasma. 2020;257:1333–44. 10.1007/s00709-020-01505-0.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Lopes EP, Ribeiro RCF, Xavier AA, Alves RM, Castro MT, Martins MJ, et al. Effect of Bacillus subtilis on Meloidogyne javanica and on tomato growth promotion. J Exp Agric Int. 2019a;35:1–8. 10.9734/JEAI/2019/v35i130197.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Lopes EP, Ribeiro RCF, Xavier AA, Castro MT, Alves RM, Martins MJ, et al. Liquid Bacillus subtilis formulation in rice for the control of Meloidogyne javanica and lettuce improvement. J Exp Agric Int. 2019b;36:1–9. 10.9734/JEAI/2019/v36i130226.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Cao H, Jiao Y, Yin N, Li Y, Ling J, Mao Z, et al. Analysis of the activity and biological control efficacy of the Bacillus subtilis strain Bs-1 against Meloidogyne incognita. Crop Prot. 2019;122:125–35. 10.1016/j.cropro.2019.04.021.Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Mondal MIH, Haque MO. Cellulosic hydrogels: A greener solution of sustainability. In: Mondal M, editor. Cellulose-based superabsorbent hydrogels. Polymers and polymeric Composites: A reference series. Cham: Springer; 2019. p. 3–35. 10.1007/978-3-319-77830-3_4.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Mantovani EC, Bernardo S, Palaretti LF. Irrigação: Princípios e métodos. Viçosa: UFV; 2009. p. 355.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Scopel W, Barbosa JZ, Vieira ML. Extração de pigmentos foliares em plantas de canola. Unoesc Ciência. 2011;2(1):87–94.Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Arnon DI. Cooper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenol oxydase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–15.10.1104/pp.24.1.1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Taylor AL, Sasser JN. Biology, identification and control of root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne sp). Raleigh, N.C: North Carolina State University; 1978. p. 111.Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Hussey RS, Barker KR. A comparison of methods of collecting inocula for Meloidogyne spp. Including a new techinque. Plant Dis Rep. 1973;57:1025–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Boneti JIS, Ferraz S. Modificação do método de Hussey e Barker para extração de ovos de Meloidogyne exigua de cafeeiro. Fitopatol Bras. 1981;6:553.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Jenkins WR. A rapid centrifugal-flotation technique for separating nematodes from soil. Plant Dis Rep. 1964;48:692.Suche in Google Scholar

[24] R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Mohamed EAH, Farag AG, Yousse FSA. Phosphate solubilization by Bacillus subtilis and Serratia marcescens isolated from tomato plant rhizosphere. J Environ Prot. 2018;9:266–77. 10.4236/jep.2018.93018.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Kuan KB, Othman R, Rahim KA, Shamsuddin ZH. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria inoculation to enhance vegetative growth, nitrogen fixation and nitrogen remobilisation of maize under greenhouse conditions. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152478. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152478.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[27] Rizzi A, Roy S, Bellenger JP, Beauregard PB. Iron homeostasis in Bacillus subtilis requires siderophore production and biofilm formation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2019;85(3):e02439-18. 10.1128/AEM.02439-18.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Santos BHCD, Ribeiro RCF, Xavier AA, Santos Neto JA, Mizobutsi EH. Nitrogen fertilization and rhizobacteria in the control of Meloidogyne javanica in common bean plants. J Agric Sci. 2019;11(1):430–7. 10.5539/jas.v11n1p430.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Lopes PS, Ribeiro RCF, Xavier AA, Rocha LDS, Mizobutsi EH. Determination of the treatment period of banana seedlings with rhizobacteria in the control of Meloidogyne javanica. Rev Bras Frutic. 2018;40(4):e-423. 10.1590/0100-29452018423.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Castro MTDE. Bactérias endofíticas no controle de Meloidogyne spp. em hortaliças. Dissertação (Mestrado em Produção Vegetal no Semiárido). Janaúba: Universidade Estadual de Montes Claros; 2021. p. 36.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Li X, He Z, Hughes JM, Liu YR, Zheng YM. Effects of super-absorbent polymers on a soil–wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) system in the field. Appl Soil Ecol. 2014;73:58–63. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2013.08.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Carvalho RP, Cruz MCM, Martins LM. Frequência de irrigação utilizando polímero hidroabsorvente na produção de mudas de maracujazeiro-amarelo. Rev Bras Frutic. 2013;35(2):518–26. 10.1590/S0100-29452013000200022.Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Conte AM, Maia GM, Souza JÁ, Manfio FLA. Crescimento inicial de cafeeiro com uso de polímero hidroabsorvente e diferentes intervalos de rega. Coffee Sci. 2014;9(4):465–71.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Pereira JS, Olszevski N, Silva JCDA. Retenção de água e desenvolvimento do feijão caupi em função do uso de polímero hidrorretentor no solo. Rev Eng Agric. 2018;26(6):582–91. 10.13083/reveng.v26i6.857.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Azambuja LO, Benett CGS, Benett KSS, Costa E. Produtividade da abobrinha ‘Caserta’ em função do nitrogênio e gel hidrorretentor. Científica. 2015;43(4):353–8.10.15361/1984-5529.2015v43n4p353-358Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Navroski M, Araujo MM, Reiniger LRS, Muniz MFB, Pereira OM. Influência do hidrogel no crescimento e no teor de nutrientes das mudas de Eucalyptus dunnii. Floresta. 2015;45(2):315–28. 10.5380/rf.v45i2.34411.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Saad JCC, Lopes JLW, Santos TA. Manejo hídrico em viveiro e uso de hidrogel na sobrevivência pós-plantio de Eucalyptus urograndis em dois solos diferentes. Rev Eng Agríc. 2009;29(3):404–11. 10.1590/S0100-69162009000300007.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Arkhipova TN, Veselov SU, Melentiev AI, Martynenko EV, Andkudoyarova GR. Ability of bacterium Bacillus subtilis to produce cytokinins and to influence the growth and endogenous hormone content of lettuce plants. Plant Soil. 2005;272:201–9. 10.1007/s11104-004-5047-x.Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Taiz L, Zeiger E, Moller IM, Murphy A. Fisiologia e Desenvolvimento Vegetal. 6ª edição. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2017. p. 888.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Khanizadeh S, Belair G, Lareau MJ. Relative susceptibility of five strawberry cultivars to Meloidogyne hapla under three soil water deficit levels. Phytoprotection. 1995;75(3):133–7. 10.7202/706060ar.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Oostenbrink M. Major characteristics of the relation between nematodes and plants. Meded Landbouwhogeschool. 1966;66:3–46.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Ramezani MM, Moghaddam EM, Ravari SB, Rouhani H. The nematicidal potential of local Bacillus species against the root-knot nematode infecting greenhouse tomatoes. Biocontrol Sci Technol. 2014;24(3):279–90. 10.1080/09583157.2013.858100.Suche in Google Scholar

[43] Adam M, Heuer H, Hallmann. Bacterial antagonists of fungal pathogens also control root-knot nematodes by induced systemic resistance of tomato plants. PLOS One. 2014;9(2):e90402. 10.1371/journal.pone.0090402.t001.Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Lee DL, Atkinson HJ. Physiology of nematodes. New York: Columbia University; 1977.10.1007/978-1-349-02667-8Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Silva CMDA. Prospecção de rizobactérias com atividades promotoras de crescimento do feijoeiro comum. Tese (Doutorado em Produção Vegetal no Semiárido). Janaúba: Universidade Estadual de Montes Claros; 2018. p. 104.Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Aballay E, Prodan S, Zamorano A, Castaneda-Alvarez C. Nematicidal effect of rhizobacteria on plant-parasitic nematodes associated with vineyards. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;33(7):1–14. 10.1007/s11274-017-2303-9.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Robinson MP, Atkinson HJ, Perry RN. The influence of soil moisture and storage time on the motility, infectivity, and lipid utilization of second-stage juveniles of the potato cyst nematodes Globodera rostochiensis and G. pallida. Rev Nematol. 1987;10(3):343–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] Van Gundy SD, Bird AF, Wallace HR. Ageing and starvation in larvae of Meloidogyne javanica and Tylenchulus semipenetrans. Phytopathology. 1967;57:559–71.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants

- Assessment of nutrition status of pineapple plants during ratoon season using diagnosis and recommendation integrated system

- Nutritional value and consumer assessment of 12 avocado crosses between cvs. Hass × Pionero

- The lacked access to beef in the low-income region: An evidence from the eastern part of Indonesia

- Comparison of milk consumption habits across two European countries: Pilot study in Portugal and France

- Antioxidant responses of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages

- Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

- Yield and vegetation index of different maize varieties and nitrogen doses under normal irrigation

- Urbanization and forecast possibilities of land use changes by 2050: New evidence in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam

- Organizational-economic efficiency of raspberry farming – case study of Kosovo

- Application of nitrogen-fixing purple non-sulfur bacteria in improving nitrogen uptake, growth, and yield of rice grown on extremely saline soil under greenhouse conditions

- Digital motivation, knowledge, and skills: Pathways to adaptive millennial farmers

- Investigation of biological characteristics of fruit development and physiological disorders of Musang King durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.)

- Enhancing rice yield and farmer welfare: Overcoming barriers to IPB 3S rice adoption in Indonesia

- Simulation model to realize soybean self-sufficiency and food security in Indonesia: A system dynamic approach

- Gender, empowerment, and rural sustainable development: A case study of crab business integration

- Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses of bacterial communities in short mackerel (Rastrelliger brachysoma) under storage conditions and inoculation of the histamine-producing bacterium

- Fostering women’s engagement in good agricultural practices within oil palm smallholdings: Evaluating the role of partnerships

- Increasing nitrogen use efficiency by reducing ammonia and nitrate losses from tomato production in Kabul, Afghanistan

- Physiological activities and yield of yacon potato are affected by soil water availability

- Vulnerability context due to COVID-19 and El Nino: Case study of poultry farming in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Wheat freshness recognition leveraging Gramian angular field and attention-augmented resnet

- Suggestions for promoting SOC storage within the carbon farming framework: Analyzing the INFOSOLO database

- Optimization of hot foam applications for thermal weed control in perennial crops and open-field vegetables

- Toxicity evaluation of metsulfuron-methyl, nicosulfuron, and methoxyfenozide as pesticides in Indonesia

- Fermentation parameters and nutritional value of silages from fodder mallow (Malva verticillata L.), white sweet clover (Melilotus albus Medik.), and their mixtures

- Five models and ten predictors for energy costs on farms in the European Union

- Effect of silvopastoral systems with integrated forest species from the Peruvian tropics on the soil chemical properties

- Transforming food systems in Semarang City, Indonesia: A short food supply chain model

- Understanding farmers’ behavior toward risk management practices and financial access: Evidence from chili farms in West Java, Indonesia

- Optimization of mixed botanical insecticides from Azadirachta indica and Calophyllum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda using response surface methodology

- Mapping socio-economic vulnerability and conflict in oil palm cultivation: A case study from West Papua, Indonesia

- Exploring rice consumption patterns and carbohydrate source diversification among the Indonesian community in Hungary

- Determinants of rice consumer lexicographic preferences in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

- Effect on growth and meat quality of weaned piglets and finishing pigs when hops (Humulus lupulus) are added to their rations

- Healthy motivations for food consumption in 16 countries

- The agriculture specialization through the lens of PESTLE analysis

- Combined application of chitosan-boron and chitosan-silicon nano-fertilizers with soybean protein hydrolysate to enhance rice growth and yield

- Stability and adaptability analyses to identify suitable high-yielding maize hybrids using PBSTAT-GE

- Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-mediated rock phosphate utilization with poultry manure enhances soil nutrient dynamics and maize growth in semi-arid soil

- Factors impacting on purchasing decision of organic food in developing countries: A systematic review

- Influence of flowering plants in maize crop on the interaction network of Tetragonula laeviceps colonies

- Bacillus subtilis 34 and water-retaining polymer reduce Meloidogyne javanica damage in tomato plants under water stress

- Vachellia tortilis leaf meal improves antioxidant activity and colour stability of broiler meat

- Evaluating the competitiveness of leading coffee-producing nations: A comparative advantage analysis across coffee product categories

- Application of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LP5 in vacuum-packaged cooked ham as a bioprotective culture

- Evaluation of tomato hybrid lines adapted to lowland

- South African commercial livestock farmers’ adaptation and coping strategies for agricultural drought

- Spatial analysis of desertification-sensitive areas in arid conditions based on modified MEDALUS approach and geospatial techniques

- Meta-analysis of the effect garlic (Allium sativum) on productive performance, egg quality, and lipid profiles in laying quails

- Optimizing carrageenan–citric acid synergy in mango gummies using response surface methodology

- The strategic role of agricultural vocational training in sustainable local food systems

- Agricultural planning grounded in regional rainfall patterns in the Colombian Orinoquia: An essential step for advancing climate-adapted and sustainable agriculture

- Perspectives of master’s graduates on organic agriculture: A Portuguese case study

- Developing a behavioral model to predict eco-friendly packaging use among millennials

- Government support during COVID-19 for vulnerable households in Central Vietnam

- Citric acid–modified coconut shell biochar mitigates saline–alkaline stress in Solanum lycopersicum L. by modulating enzyme activity in the plant and soil

- Herbal extracts: For green control of citrus Huanglongbing

- Research on the impact of insurance policies on the welfare effects of pork producers and consumers: Evidence from China

- Investigating the susceptibility and resistance barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars against the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia)

- Characterization of promising enterobacterial strains for silver nanoparticle synthesis and enhancement of product yields under optimal conditions

- Testing thawed rumen fluid to assess in vitro degradability and its link to phytochemical and fibre contents in selected herbs and spices

- Protein and iron enrichment on functional chicken sausage using plant-based natural resources

- Fruit and vegetable intake among Nigerian University students: patterns, preferences, and influencing factors

- Bioprospecting a plant growth-promoting and biocontrol bacterium isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico: Paenibacillus sp. strain TSM33

- Quantifying urban expansion and agricultural land conversion using spatial indices: evidence from the Red River Delta, Vietnam

- Review Articles

- Reference dietary patterns in Portugal: Mediterranean diet vs Atlantic diet

- Evaluating the nutritional, therapeutic, and economic potential of Tetragonia decumbens Mill.: A promising wild leafy vegetable for bio-saline agriculture in South Africa

- A review on apple cultivation in Morocco: Current situation and future prospects

- Quercus acorns as a component of human dietary patterns

- CRISPR/Cas-based detection systems – emerging tools for plant pathology

- Short Communications

- An analysis of consumer behavior regarding green product purchases in Semarang, Indonesia: The use of SEM-PLS and the AIDA model

- Effect of NaOH concentration on production of Na-CMC derived from pineapple waste collected from local society

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants

- Assessment of nutrition status of pineapple plants during ratoon season using diagnosis and recommendation integrated system

- Nutritional value and consumer assessment of 12 avocado crosses between cvs. Hass × Pionero

- The lacked access to beef in the low-income region: An evidence from the eastern part of Indonesia

- Comparison of milk consumption habits across two European countries: Pilot study in Portugal and France

- Antioxidant responses of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages

- Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

- Yield and vegetation index of different maize varieties and nitrogen doses under normal irrigation

- Urbanization and forecast possibilities of land use changes by 2050: New evidence in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam

- Organizational-economic efficiency of raspberry farming – case study of Kosovo

- Application of nitrogen-fixing purple non-sulfur bacteria in improving nitrogen uptake, growth, and yield of rice grown on extremely saline soil under greenhouse conditions

- Digital motivation, knowledge, and skills: Pathways to adaptive millennial farmers

- Investigation of biological characteristics of fruit development and physiological disorders of Musang King durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.)

- Enhancing rice yield and farmer welfare: Overcoming barriers to IPB 3S rice adoption in Indonesia

- Simulation model to realize soybean self-sufficiency and food security in Indonesia: A system dynamic approach

- Gender, empowerment, and rural sustainable development: A case study of crab business integration

- Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses of bacterial communities in short mackerel (Rastrelliger brachysoma) under storage conditions and inoculation of the histamine-producing bacterium

- Fostering women’s engagement in good agricultural practices within oil palm smallholdings: Evaluating the role of partnerships

- Increasing nitrogen use efficiency by reducing ammonia and nitrate losses from tomato production in Kabul, Afghanistan

- Physiological activities and yield of yacon potato are affected by soil water availability

- Vulnerability context due to COVID-19 and El Nino: Case study of poultry farming in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Wheat freshness recognition leveraging Gramian angular field and attention-augmented resnet

- Suggestions for promoting SOC storage within the carbon farming framework: Analyzing the INFOSOLO database

- Optimization of hot foam applications for thermal weed control in perennial crops and open-field vegetables

- Toxicity evaluation of metsulfuron-methyl, nicosulfuron, and methoxyfenozide as pesticides in Indonesia

- Fermentation parameters and nutritional value of silages from fodder mallow (Malva verticillata L.), white sweet clover (Melilotus albus Medik.), and their mixtures

- Five models and ten predictors for energy costs on farms in the European Union

- Effect of silvopastoral systems with integrated forest species from the Peruvian tropics on the soil chemical properties

- Transforming food systems in Semarang City, Indonesia: A short food supply chain model

- Understanding farmers’ behavior toward risk management practices and financial access: Evidence from chili farms in West Java, Indonesia

- Optimization of mixed botanical insecticides from Azadirachta indica and Calophyllum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda using response surface methodology

- Mapping socio-economic vulnerability and conflict in oil palm cultivation: A case study from West Papua, Indonesia

- Exploring rice consumption patterns and carbohydrate source diversification among the Indonesian community in Hungary

- Determinants of rice consumer lexicographic preferences in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

- Effect on growth and meat quality of weaned piglets and finishing pigs when hops (Humulus lupulus) are added to their rations

- Healthy motivations for food consumption in 16 countries

- The agriculture specialization through the lens of PESTLE analysis

- Combined application of chitosan-boron and chitosan-silicon nano-fertilizers with soybean protein hydrolysate to enhance rice growth and yield

- Stability and adaptability analyses to identify suitable high-yielding maize hybrids using PBSTAT-GE

- Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-mediated rock phosphate utilization with poultry manure enhances soil nutrient dynamics and maize growth in semi-arid soil

- Factors impacting on purchasing decision of organic food in developing countries: A systematic review

- Influence of flowering plants in maize crop on the interaction network of Tetragonula laeviceps colonies

- Bacillus subtilis 34 and water-retaining polymer reduce Meloidogyne javanica damage in tomato plants under water stress

- Vachellia tortilis leaf meal improves antioxidant activity and colour stability of broiler meat

- Evaluating the competitiveness of leading coffee-producing nations: A comparative advantage analysis across coffee product categories

- Application of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LP5 in vacuum-packaged cooked ham as a bioprotective culture

- Evaluation of tomato hybrid lines adapted to lowland

- South African commercial livestock farmers’ adaptation and coping strategies for agricultural drought

- Spatial analysis of desertification-sensitive areas in arid conditions based on modified MEDALUS approach and geospatial techniques

- Meta-analysis of the effect garlic (Allium sativum) on productive performance, egg quality, and lipid profiles in laying quails

- Optimizing carrageenan–citric acid synergy in mango gummies using response surface methodology

- The strategic role of agricultural vocational training in sustainable local food systems

- Agricultural planning grounded in regional rainfall patterns in the Colombian Orinoquia: An essential step for advancing climate-adapted and sustainable agriculture

- Perspectives of master’s graduates on organic agriculture: A Portuguese case study

- Developing a behavioral model to predict eco-friendly packaging use among millennials

- Government support during COVID-19 for vulnerable households in Central Vietnam

- Citric acid–modified coconut shell biochar mitigates saline–alkaline stress in Solanum lycopersicum L. by modulating enzyme activity in the plant and soil

- Herbal extracts: For green control of citrus Huanglongbing

- Research on the impact of insurance policies on the welfare effects of pork producers and consumers: Evidence from China

- Investigating the susceptibility and resistance barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars against the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia)

- Characterization of promising enterobacterial strains for silver nanoparticle synthesis and enhancement of product yields under optimal conditions

- Testing thawed rumen fluid to assess in vitro degradability and its link to phytochemical and fibre contents in selected herbs and spices

- Protein and iron enrichment on functional chicken sausage using plant-based natural resources

- Fruit and vegetable intake among Nigerian University students: patterns, preferences, and influencing factors

- Bioprospecting a plant growth-promoting and biocontrol bacterium isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico: Paenibacillus sp. strain TSM33

- Quantifying urban expansion and agricultural land conversion using spatial indices: evidence from the Red River Delta, Vietnam

- Review Articles

- Reference dietary patterns in Portugal: Mediterranean diet vs Atlantic diet

- Evaluating the nutritional, therapeutic, and economic potential of Tetragonia decumbens Mill.: A promising wild leafy vegetable for bio-saline agriculture in South Africa

- A review on apple cultivation in Morocco: Current situation and future prospects

- Quercus acorns as a component of human dietary patterns

- CRISPR/Cas-based detection systems – emerging tools for plant pathology

- Short Communications

- An analysis of consumer behavior regarding green product purchases in Semarang, Indonesia: The use of SEM-PLS and the AIDA model

- Effect of NaOH concentration on production of Na-CMC derived from pineapple waste collected from local society