Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

-

Natchanon Meesa

and Phithak Inthima

Abstract

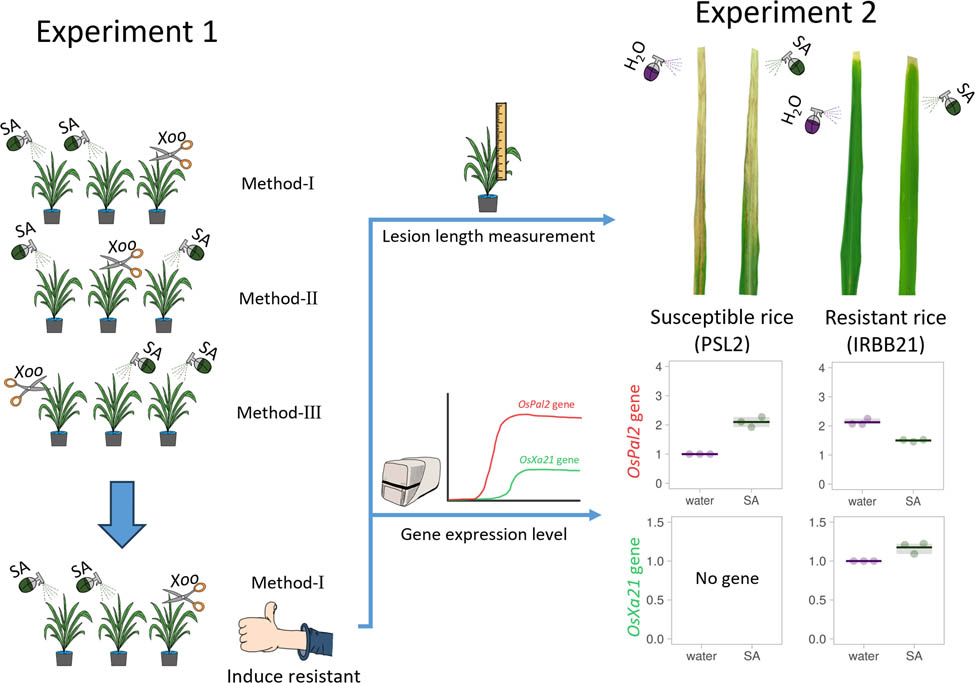

Salicylic acid (SA) serves as a pivotal signaling agent, activating defense mechanisms such as hypersensitive responses and systemic acquired resistance in various plants. This study aims to investigate the impact of SA application on bacterial blight (BB) resistance across diverse rice cultivars. The optimization of SA spraying involved testing three distinct methods: Method Ⅰ (daily spraying with SA for 2 consecutive days before inoculation), Method II (spraying with SA once before inoculation and again 1 day after inoculation), and Method III (daily spraying with SA for 2 consecutive days after inoculation). Each method was evaluated using varying SA concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, and 2 mM) to determine their efficacy in susceptible rice cultivars. The most effective approach, Method I, was then extended to different rice cultivars to evaluate SA’s influence on disease resistance induction and defense-related gene expression in “Phitsanulok 2” (“PSL2”), “IRBB21,” and backcrossed lines (“PSL2-Xa21” BC5F6). The results revealed that Method Ⅰ, with 2 mM SA applied before inoculation, significantly reduced lesion length by 4.6% in the susceptible “PSL2” cultivar compared to the H2O treatment. However, the impact was less pronounced in the resistant “IRBB21” and moderately resistant “PSL2-Xa21” cultivars, both carrying the Xa21 resistance gene. SA spraying up-regulated OsPal2 gene expression in the “PSL2” cultivar and enhanced OsXa21 gene expression in the “IRBB21” and “PSL2-Xa21” cultivars, compared to the H2O treatment control. These findings emphasize the potential of SA as a signaling molecule capable of activating defense mechanisms against BB disease in a range of rice cultivars, warranting further investigation into its application for BB management. Future research should focus on conducting field trials to assess the practical applicability of this approach under diverse agricultural settings. Additionally, investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction of SA and genetic resistance in rice will provide deeper insight into optimizing this strategy for effective disease control.

Graphical abstract

Source: Created by the authors.

1 Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is a major agricultural crop consumed widely around the world, with most of its production centered in Asia [1]. However, rice production faces various limitations, including soil characteristics, climate changes, insect infestations, and diseases. Among these, bacterial blight (BB) disease, caused by the bacterial Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo), is particularly devastating, leading to yield losses ranging from 30% to 60%, depending on the Xoo strain [2]. Despite extensive efforts, effective strategies for managing the Xoo epidemic in rice fields have not been successfully developed [3].

To date, the most effective approach to enhance resistance to BB disease is the introduction of resistance genes into susceptible rice cultivars through multi-generation backcrossing programs [4]. Recently, at least 46 BB resistance genes have been identified from diverse rice cultivars. Among these, the resistance gene OsXa21, encoding a receptor-like protein kinase (RLK), has been proven to confer broad-spectrum resistance against diverse strains of Xoo [5,6]. The OsXa21 gene triggers a systemic acquired resistance (SAR) response in rice, resulting in an enhanced defense response, such as hypersensitive reaction. Additionally, the OsXa21 encodes an RLK-immune receptor that recognizes and interacts with the RaxX protein secreted by Xoo, forming a complex necessary for activating Xa21-mediated immunity in rice [7].

Another promising strategy involves the application of salicylic acid (SA), which has been proven to reduce severe BB symptoms in rice. SA plays a crucial role in plant defense against various pathogens by inducing a series of defensive-response pathways and triggering defense-related genes [8]. For example, the exogenous SA elicitor has been proven to reduce the growth of pathogenic Xoo and reduce the BB disease severity in the susceptible rice cultivar “KDML105” [3]. Additionally, SA acted as a signal transducer (SA receptor), triggered the up-regulation of resistance genes such as xa5 [9], and defensive genes related to defense protein pathways, including OsNPR1 and OsTGA [10], OsPR1 [11], and OSWRKY45, which is associated with the cell death pathway [12].

These findings suggest that the combined utilization of the OsXa21 resistance gene and SA elicitor could enhance BB resistance in rice by reducing visible BB symptoms, limiting Xoo proliferation, and controlling the spread of Xoo during infection. However, prior research has largely focused on either SA application or OsXa21 resistance independently, without investigating their combined effects. Furthermore, no studies have systematically optimized SA application methods for eliciting BB resistance in rice genotypes with varying levels of susceptibility or resistance. Understanding the mechanisms by which SA enhances disease resistance can lead to the development of more effective, integrated pest management strategies. Additionally, optimizing SA application methods could provide a more sustainable and environmentally friendly alternative to chemical pesticides. Therefore, the aims of this study were to optimize the SA application for increasing BB resistance against Xoo infection and to quantify SA-mediated responsive genes in the rice cultivars “IRBB21” (a resistant cultivar), “PSL2” (a susceptible cultivar), and three backcrossed lines (“PSL2-Xa21-L1” to “PSL2-Xa21-L3”).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials

Rice seeds from the cultivar “Phitsanulok 2” (“PSL2”), “IRBB21,” and “PSL2-Xa21” BC5F6 were germinated and grown under greenhouse condition at the Faculty of Science, Naresuan University, Thailand. Seedlings were initially cultivated in tray, with one plant per cell. Fourteen-day-old seedlings were then transplanted into individual pots (12 in. in diameter) containing soil. To support plant growth, a 16–20–0 (N–P–K) fertilizer was applied at 5 g/pot every 15 days. When the rice plants reached 55 days old, corresponding to the flourishing tillering stage, they were subjected to experimental foliar spray treatments and Xoo inoculation.

2.2 Optimization of SA-sprayed application

To optimize the application of SA for inducing resistance, various SA concentrations (0.5, 1, and 2 mM) were tested on the susceptible rice cultivar “PSL2.” Each plant received 50 mL of the SA solution. The experiment employed three different application methods:

Method I: SA solutions were sprayed once daily over the course of 2 consecutive days on the entire rice plant before Xoo inoculation.

Method II: SA solutions were sprayed one day before Xoo inoculation and again 1 day after inoculation.

Method III: SA solutions were sprayed once daily over the course of 2 consecutive days on the entire rice plant after the Xoo inoculation.

The length of BB lesions was measured at 7 and 14 days after Xoo inoculation (DAI). The optimal SA application method identified from these experiments was used in subsequent studies.

2.3 SA application across various rice cultivars

Fifty-five-day-old rice plants, including the susceptible cultivar “PSL2,” the resistant cultivar “IRBB21,” and the backcrossed line BC5F6 (“PSL2-Xa21-L1” to “PSL2-Xa21-L3”) were subjected to the optimal SA spray application as described previously. Following the SA treatment, Xoo inoculation was performed. The quantification of Xoo copies was conducted at 3 DAI. The length of BB lesions was measured at 7 and 14 DAI. Additionally, the expression levels of genes involved in Xoo resistance were examined at 0, 120, and 180 min after Xoo inoculation (MAI).

2.4 Xoo inoculation and lesion length measurement

Xoo strain Xoo16PK002, isolated and identified by Buddhachat et al. [13], was cultured on nutrient agar (0.3% beef extract, 0.5% peptone, and 1.5% agar) and incubated at 28°C for 3–5 days. The resulting Xoo colonies were suspended in 10 mL of sterilized distilled water and adjusted to an absorbance value of 0.2 at 600 nm optical density (OD600) using a spectrophotometer, yielding an inoculum concentration of 2.5 × 108 cfu/mL. This Xoo inoculum was immediately used for rice infection.

The Xoo inoculation test was conducted on 55-day-old rice plants using the clipping-leaf method, as described by Ke et al. [14]. Post-inoculation, the length of BB lesions was measured using a tape measure and photographed with a digital camera at 7 and 14 DAI.

2.5 Quantification of bacterial Xoo copies

At 3 DAI, rice leaf samples (1 cm2) were excised from the area below 2 cm of the lesion site using sterile techniques. Each leaf sample was finely chopped and mixed in autoclaved distilled water using a vortex for 1 min, followed by incubation at room temperature for 1 h. The supernatant containing bacterial Xoo was collected for quantification using quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay with Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) on the CFX Duet Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, USA). For the qPCR, 1 µL of Xoo supernatant was mixed with Xoo4009 primer (Table 1) and Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix. The thermal cycling conditions included an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. A final extension step was performed at 72°C for 5 min. The cycle threshold (C t) values obtained from the samples were compared against a standard curve prepared using a series of 10-fold dilutions of the Xoo suspension with an OD600 of 0.2 (equivalent to 2.5 × 108 cfu/mL). The standard curve allowed for the determination of Xoo concentration in the samples based on their C t values.

Primers and sequences for this study

| Primer name | Sequences (5′–3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Xoo4009-F3 | GTTCACCCTGCCCTTCATTTCCGTCGTCATC | [13] |

| Xoo4009-B3 | CCTTTGAGATCGCATGCATGAAGAACCACCACA | |

| Edf-F | TCCGAACCAGCAGATCATCG | [15] |

| Edf-R | GCATGGTATCAAAAGACCCAGC | |

| Xa21-F | CAGAGTATGGCGTTGGGCT | [16] |

| Xa21-R | CGGGTCTGAATGTACTGTCA | |

| NPR1-F | TTTCCGATGGAGGCAAGAG | [10] |

| NPR1-R | GCTGTCATCCGAGCTAAGTGTT | |

| WRKY45-F | CCGGCATGGAGTTCTTCAAG | [17] |

| WRKY45-R | TATTTCTGTACACACGCGTGGAA | |

| Pal2-F | GCATTTCGAGAGTGTGAATGTT | [18] |

| Pal2-R | AGAACTTCTTCAGAGAACGAGC |

2.6 Quantification of gene expression profile

Rice leaf samples (approximately 5 cm2) were harvested from the area located 2 cm below the Xoo-clipping site at specific time points: 0, 120, and 180 MAI. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and total RNA was extracted using the FavorPrep™ Plant Total RNA Mini Kit (Favorgen, Taiwan), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomic DNA contamination was removed from the extracted RNA using the RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega, USA). The quantity, quantity, and integrity of total RNA were assessed using gel electrophoresis and the NanoDrop™ Lite Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Subsequently, cDNA synthesis was performed using the SensiFAST™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Meridian Bioscience, USA), with the total RNA serving as the template according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Gene expression levels were analyzed using HOT FIREPol® EvaGreen® qPCR Mix Plus (no ROX, 5× Solis BioDyne, Estonia) on the CFX Duet Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad, USA). The qPCR conditions included an initial denaturation at 95°C for 12 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s. A final extension step was performed at 72°C for 5 min. The C t values obtained for the target genes were normalized to the housekeeping gene Endothelial Differentiation Related Factor (edf) [15]. Gene expression levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method [19]. Primer sequences used in the qPCR assay are listed in Table 1.

2.7 Data analysis

The experiment was conducted using a completely randomized design with three and five plant replicates for the respective treatments. Data visualization was performed using the PlotsOfData web application [20]. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics version 17.0 for Windows. Prior to conducting one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Levene’s test, respectively. All data met these assumptions. Statistically significant differences among treatment means were determined using one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s new multiple range test at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 or 0.01.

3 Results

3.1 Optimization of SA concentration against BB disease in rice cultivar “PSL2”

Figure 1a illustrates the progression of BB lesions on rice leaves at 7 DAI. The primary symptoms of the disease initially appeared at the leaf tip, the site of infection, and included the formation of yellowish stripes on the leaf blades. These stripes were accompanied by distinct golden-yellow marginal necrosis, rolled leaf edges, and eventual overall yellow discoloration. In Method I, where SA was applied prior to Xoo inoculation, significant reductions in BB lesion length were observed with 0.5 and 2 mM SA treatment, achieving reduction of 10.7 and 10.3%, respectively, compared to the untreated control (Figure 1b, left panel). Conversely, the 1 mM SA treatment resulted in a 6.9% increase in lesion length compared to the control. For Method II, where SA was applied before and after Xoo inoculation, most SA treatments (except for the 2 mM concentration) did not showed significant differences in lesion length. The 2 mM SA treatment in this method led to a 10.4% increase in lesion length compared to the control (Figure 1b, middle panel). In Method III, where SA was applied after Xoo inoculation, all SA treatments resulted in substantial reductions in lesion length, ranging from 10.9 to 15.3% compared to the control (Figure 1b, right panel). This indicates the efficacy of post-inoculation SA application in reducing BB lesion length. To sum up, at 7 DAI, the most effective strategy for reducing lesion length was identified as the dual application of 0.5 and 2 mM SA via spraying before Xoo inoculation (Method I, Figure 1b, left panel).

BB disease symptom (a) and lesion length of BB disease (b) at 7 days after Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) inoculation in “Phitsanulok 2” rice cultivars sprayed with 0-, 0.5-, 1-, and 2-mM SA two times before, before and after, and after inoculation. In (b), each dot represents the lesion length obtained from five plants (two leaves each), the horizontal line indicates the mean, and the gray box shows the range of data. The difference letters above the data show significant differences in the mean analyzed by Duncan’s new multiple range test at p ≤ 0.05.

By 14 DAI, the BB disease symptoms had significantly progressed, presenting as marked brown discoloration on the leaves (Figure 2a). The application of SA through Method Ⅰ continues to show a trend of reducing lesion length with increasing SA concentration (Figure 2b, left panel). Specifically, 1 and 2 mM SA treatments resulted in significant lesion length reductions of 5.8 and 9.0%, respectively, compared to the control. For Method II and Method III, most SA treatments did not show significant differences in lesion length reduction, with the exception of Method II at 0.5 mM SA (Figure 2b).

BB disease symptom (a) and lesion length of BB disease (b) at 14 days after Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) inoculation in “Phitsanulok 2” rice cultivars sprayed with 0-, 0.5-, 1-, and 2-mM SA two times before, before and after, and after inoculation. In (b), each dot represents the lesion length obtained from five plants (two leaves each), the horizontal line indicates the mean, and the gray box shows the range of data. The difference letters above the data show significant differences in the mean analyzed by Duncan’s new multiple range test at p ≤ 0.05.

In conclusion, the utilization of a 2 mM SA application in Method Ⅰ was identified as the optimal approach for inducing resistance against BB, leading to a significant reduction in lesion length in the susceptible rice cultivar “PSL2.” This specific concentration and application method have been selected for further experiments.

3.2 Effect of SA on Xoo population across various rice cultivars

In the backcrossed lines “PSL2-Xa21-L2” and “PSL2-Xa21-L3,” a significantly elevated Xoo population was observed compared to both the maternal donor, “PSL2,” and the paternal donor, “IRBB21,” rice cultivars (Figure 3). Among the three backcrossed lines, “PSL2-Xa21-L3” exhibited a statistically significant reduction (p ≤ 0.05) in Xoo population by 8.9-fold when compared the untreated SA control (Figure 3). In contrast, “PSL2-Xa21-L2” showed a statistically significant increase (p ≤ 0.05) in Xoo population by 1.8-fold relative to the untreated SA condition (Figure 3). It is also noteworthy that “PSL2-Xa21-L1” exhibited a tendency towards an increased Xoo population, although this increase did not reach statistical significance when compared to the untreated SA control.

Number of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) in inoculated leaves at 3 days after Xoo inoculation of “Phitsanulok 2” (“PSL2,” recipient parent), “IRBB21” (donor parent), and three hybrids (“PSL2-Xa21-L1”-“L3”) rice cultivars. The rice plants were sprayed with 0- and 2-mM SA two times before inoculation. Each dot represents the number of Xoo data obtained from 5 plants (1 leaves each), the horizontal line indicates the mean, and the gray box shows range of data. The difference letters above the data show significant differences in the mean analyzed by Duncan’s new multiple range test at p ≤ 0.05.

In summary, the application of SA did not significantly impact the Xoo population in most of the examined rice cultivars. The exception was observed in “PSL2-Xa21-L3” rice, where the application of 2 mM SA via Method Ⅰ led to a statistically significant reduction in the Xoo population compared to the untreated SA control.

3.3 Efficacy of SA application against BB disease across various rice cultivars

The manifestation of BB disease symptoms across different rice cultivars at 7 DAI is depicted in Figure 4a. Among the rice cultivars treated with either 2 mM SA and H2O (0 mM SA), the resistant “IRBB21” cultivar exhibited the mildest disease symptoms, while the three backcrossed cultivars “PSL2-Xa21-L1,” “PSL2-Xa21-L2,” and “PSL2-Xa21-L3” displayed moderate BB symptoms. In contrast, the susceptible rice cultivar “PSL2” showed the most pronounced BB symptoms (Figure 4a). These observations were consistent with the BB lesion lengths measured at 7 DAI, as illustrated in Figure 4b. Remarkably, the “IRBB21” cultivar demonstrated a significant reduction in lesion length, up to 6.3-fold compared to “PSL2.” Similarly, all backcrossed cultivars exhibited substantial reductions in lesion length ranging from 3.4- to 3.7-fold compared to “PSL2.” However, no significant differences in lesion length were observed between SA-treated and H2O-treated rice across all the tested cultivars.

BB disease symptom (a) and lesion length of BB disease (b) at 7 days after Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) inoculation in “Phitsanulok 2” (“PSL2,” recipient parent), “IRBB21” (donor parent), and three hybrids (“PSL2-Xa21-L1”-“L3”) rice cultivars sprayed with 0- and 2-mM SA two times before inoculation. In (b), each dot represents the lesion length obtained from five plants (six leaves each), the horizontal line indicates the mean, and the gray box shows the range of data. The difference letters above the data show significant differences in the mean analyzed by Duncan’s new multiple range test at p ≤ 0.01.

At 14 DAI, the progression of BB symptoms was evident through the gradual increase in lesion length, as shown in Figure 5a. The results revealed that lesion lengths observed in “IRBB21,” “PSL2-Xa21-L1,” “PSL2-Xa21-L2,” and “PSL2-Xa21-L3” did not significantly differ between SA and H2O treatments (Figure 5b). However, all these cultivars exhibited statistically significant reductions in lesion length compared to “PSL2,” with reductions of 13.7-fold, 7.4-fold, 7.6-fold, and 8.7-fold, respectively. In contrast, “PSL2” rice treated with 2 mM SA showed a statistically significant reduction (p ≤ 0.01) in lesion length (4.6%) compared to the H2O treatment control. In summary, the application of 2 mM SA demonstrates greater potential for reducing lesion length in susceptible “PSL2” rice compared to highly resistant “IRBB21” and moderately resistant “PSL2-Xa21” rice cultivars.

BB disease symptom (a) and lesion length of BB disease (b) at 14 days after Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) inoculation in “Phitsanulok 2” (“PSL2,” recipient parent), “IRBB21” (donor parent), and three hybrids (“PSL2-Xa21-L1”-“L3”) rice cultivars sprayed with 0- and 2-mM SA two times before inoculation. In (b), each dot represents the lesion length obtained from five plants (six leaves each), the horizontal line indicates the mean, and the gray box shows the range of data. The difference letters above the data show significant differences in the mean analyzed by Duncan’s new multiple range test at p ≤ 0.01.

3.4 Impact of SA on gene expression profiles across various rice cultivars

The transcript levels of O. sativa XA21 receptor kinase (OsXa21) gene in the studied rice cultivars (“IRBB21,” “PSL2-Xa21-L1,” and PSL2-Xa21-L2”) were initially at their highest point immediately after Xoo inoculation (0 MAI) for both SA-treated and untreated conditions (Figure 6a). Subsequently, a discernible trend of down-regulation in OsXa21 expression was observed at 120 and 180 MAI. In SA-treated rice cultivars “IRBB21” and “PSL2-Xa21-L1,” the OsXa21 gene exhibited robust expression at 0 MAI, approximately 1.2-fold and 1.6-fold higher than the untreated control, respectively. Notably, at 120 and 180 MAI, SA-treated “IRBB21” rice maintained higher OsXa21 expression level compared to the H2O treatment. Conversely, the SA-treated “PSL2-Xa21-L3” line demonstrated a significant increase in OsXa21 gene expression at 180 MAI compared to 0 DAI.

The relative expression of OsXa21 (a), OsWRKY45 (b), OsNPR1 (c), and OsPal2 (d) genes at 0, 120, and 180 min after Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) inoculation (MAI) of “Phitsanulok 2” (“PSL2”, recipient parent), “IRBB21” (donor parent), and three hybrids (“PSL2-Xa21-L1”-“L3”) rice cultivars. The rice plants were sprayed with 0- and 2-mM SA two times before inoculation. Each dot represents a relative expression obtained from three plants, the horizontal line indicates the mean, and the gray box shows the range of data. The difference letters above the data of the same gene show significant differences in the mean analyzed by Duncan’s new multiple range test at p ≤ 0.01. MAI, minutes after inoculation.

In both SA- and H2O-treated “PSL2” rice, the O. sativa WRKY45 (OsWRKY45) gene maintained consistent expression levels across all Xoo infection time points, with a slight upward trend observed during extended infection periods (120 and 180 MAI, Figure 6b). Conversely, in both SA- and H2O-treated “IRBB21” rice, OsWRKY45 expression displayed a significant down-regulation during Xoo infection at 120 and 180 MAI compared to the expression at 0 MAI (Figure 6b). These findings suggest that the application of SA did not significantly impact OsWRKY45 expression post-Xoo infection. Notably, the expression of OsWRKY45 exhibited significant differences under SA and H2O treatments across the three backcrossed lines following Xoo infection. In “PSL2-Xa21-L1,” there was no significant difference in OsWRKY45 expression between SA-treated and untreated samples at 120 and 180 MAI compared to 0 MAI. In “PSL2-Xa21-L2,” untreated samples initially displayed an up-regulation at 120 MAI, while SA-treated rice exhibited up-regulation at 180 MAI compared to 0 MAI. Furthermore, within the “PSL2-Xa21-L3” context, untreated samples demonstrated a significant up-regulation in OsWRKY45 expression at 120 MAI, maintaining this elevated level at 180 MAI. In contrast, SA-treated samples exhibited a gradual increase in expression that persisted until 180 MAI (Figure 6b).

The expression pattern of the O. sativa Nonexpressor of pathogenesis-related genes 1 (OsNPR1) gene is presented in Figure 6c. In both SA- and H2O-treated “IRBB21” rice cultivar, OsNPR1 expression was notably higher at 180 MAI compared to 0 MAI and 120 MAI. Similarly, OsNPR1 expression in both SA- and H2O-treated “PSL2” rice cultivars showed a slight increase following extended periods of Xoo infection. In the backcrossed line “PSL2-Xa21-L1,” OsNPR1 expression under both SA and H2O treatments became evident at 180 MAI, mirroring the pattern observed in “IRBB21.” Interestingly, in the SA-treated “PSL2-Xa21-L1” line, OsNPR1 expression was suppressed before Xoo inoculation (0 MAI), a characteristic not observed in untreated samples. Furthermore, in the SA-treated backcrossed lines “PSL2-Xa21-L2” and “PSL2-Xa21-L3,” OsNPR1 expression was up-regulated at 120 MAI, while non-treated samples exhibited up-regulation at 180 MAI. However, non-treated samples still displayed significantly higher gene expression levels than their SA-treated counterparts at 180 MAI.

The expression profile of the O. sativa Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase 2 (OsPal2) gene in SA-treated “PSL2” rice exhibited a notable increase (approximately 2.1-fold) at 0 MAI compared to untreated SA samples. However, following Xoo inoculation at 120 and 180 MAI, both H2O-treated and SA-treated samples showed down-regulation of the OsPal2 gene expression (Figure 6d). In both H2O- and SA-treated rice cultivar “IRBB21,” OsPal2 expression demonstrated significant down-regulation at 120 MAI. A notable increase in OsPal2 expression was observed at 180 MAI compared to 120 MAI, with SA-treated “IRBB21” exhibiting higher expression levels compared to the H2O-treated group. Among the three backcrossed lines subjected to SA treatment, OsPal2 gene expression exhibited significant down-regulation at 120 MAI compared to 0 MAI, followed by a subsequent significant increase at 180 MAI relative to 120 MAI. For the non-treated SA samples, the “PSL2-Xa21-L2” backcrossed lines displayed significant down-regulation of OsPal2 gene expression following inoculation at 120 MAI. Similarly, “PSL2-Xa21-L3” backcrossed lines showed down-regulation of gene expression at 180 MAI compared to 0 MAI. In contrast, within the “PSL2-Xa21-L1” backcross line, non-treated SA samples exhibited up-regulated gene expression with no significant difference in expression levels at 180 MAI compared to 0 MAI.

4 Discussion

SA is a pivotal signaling molecule in plants, crucial for responding to various stresses, particularly biotic challenges such as pathogen attacks [21]. It plays a significant role in stimulating the plant’s defense mechanisms against diseases [22,23], primarily through the mechanism of SAR [24,25]. Our results unveiled that the most effective approach for inducing resistance against BB in rice was the application of 2 mM SA using Method I (two SA sprays on rice leaves for 2 consecutive days prior to Xoo inoculation). This method resulted in diminished severe symptoms and reduced lesion length in the susceptible rice cultivar “PSL2” at both 7 and 14 DAI (Figure 2). These findings are consistent with prior studies. For instance, treatment with 2 mM SA significantly alleviated BB severity in the rice cultivar “Taichung Native 1 (TN1)” infected Xoo pathogens [26]. Similarly, optimal SA concentrations (1–3 mM) have shown the highest efficacy in enhancing BB resistance in the susceptible rice cultivar “KDM105” [27]. Furthermore, our results align with observations where pre-infection exogenous SA treatment enhanced systemic resistance, providing defense against various diseases such as powdery mildew in Bhindi Masala [28], Potato virus Y in Solanum tuberosum [29], and BB in O. sativa [30]. This enhanced resistance can be attributed to the activation of SA signaling components that trigger the accumulation of defensive compounds in plants [25]. Additionally, SA accumulation might also induce hypersensitive responses, leading to localized cell death at the infection site [31]. The subsequent transport of SA through vascular bundles prompts the synthesis of pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins, thereby strengthening the plant’s defense against pathogenic attack [32]. The overall effect of SA in fortifying plant defenses underscores its potential as a critical component in managing BB in rice.

The application of SA can be administered through various methods, typically categorized into three main approaches. The first method involves preventative spraying before the introduction of pathogens or the onset of disease. Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach in disease management. For instance, Li et al. [33] showed that preventive spraying can confer resistance to the tomato yellow leaf curl virus in tomatoes. Similar outcomes have been observed in inducing resistance against BB disease in rice [3,34] and in minimizing sheath blight disease lesions in Brachypodium distachyon [35]. The second approach involves spraying after the introduction of pathogens, constituting a treatment strategy. Notable instances of this method include the effective response to BB disease in rice [30] and the induction of resistance to the blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae in rice [36]. The third approach combines both preventive and treatment strategies, encompassing applications before and after pathogen introduction. This combined approach has proven effective in enhancing resistance to wheat leaf rust disease in wheat plants [37]. Comparative studies have also assessed the impacts of different SA spraying timings. For example, Vimala and Suriachandraselvan [28] discovered that spraying SA before Erysiphe cichoracearum inoculation led to higher phenolic content and phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) activity compared to post-inoculation SA spraying, influencing powdery mildew disease resistance. Furthermore, El-Shazly et al. [29] demonstrated that spraying SA 7 days before Potato virus Y infection in potatoes resulted in a 1.1-fold and 1.3-fold reduction in virus concentration compared to spraying SA 3 days before or 24 h after infection, respectively. However, most studies primarily focus on comparing the effects of spraying before versus after pathogen introduction. Our study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis by incorporating both preemptive and post-inoculation spraying, comparing them against sole preventive or post-inoculation spraying methods. This approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of the optimal SA application timing and its effects on disease resistance in rice.

Previous research has documented that the application of exogenous SA can lead to a decline in pathogen populations in various crops, including “KDML105” rice [30], sugarcane [38], and potatoes [39]. However, our experiments did not reveal any significant effects on reducing Xoo populations in either the susceptible “PSL2” or the resistant “IRBB21” rice cultivars when subjected to SA treatments. This discrepancy could potentially be attributed to the fact that the Xoo-infected samples were collected at early stages before bacterial proliferation had reached the logarithmic phase of cell division. Similarly, in the case of tomato plants, no notable difference was observed in the populations of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus at 2 and 4 days post-inoculation between SA-treated and untreated plants. Nevertheless, a clear divergence emerged at 10 days post-inoculation, with a noticeable reduction in the virus population in SA-treated tomato plants [33]. Correspondingly, in sugarcane, the number of phytoplasmas showed a substantial increase at 14 days post-inoculation in H2O-treated plants, whereas their populations declined in SA-treated sugarcane at the same interval [38]. A notable observation arose from the analysis of the backcrossed line “PSL2-Xa21-L2,” where the Xoo population exhibited a more marked reduction under SA treatment compared to the H2O-treated control. This discrepancy could be attributed to distinct genetic backgrounds, resulting from the combination of genetic traits from both recipient and donor parental lines. This assumption could be supported by the work of Yang et al. [40], who discovered that Arabidopsis thaliana hybrids showcased varied disease resistance due to their differing genetic compositions. These findings underscore the complexity of SA-mediated pathogen resistance and highlight the influence of genetic background on the effectiveness of SA treatment. Further, research is needed to elucidate the specific genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying these observations, potentially leading to more targeted and effective use of SA in crop production.

The efficacy of SA-triggered defense mechanisms against pathogens in plants can exhibit variations based on distinct plant genetic backgrounds. The study by Li et al. [33] demonstrated that susceptible tomato cultivars exhibited a notably greater reduction in disease severity when treated with SA compared to their resistant counterparts. Similarly, our findings align with this trend, revealing that exogenous SA treatment led to a reduction in lesion length solely within susceptible cultivars (“PSL2”), but not in resistant cultivars (“IRBB2”) or hybrid lines carrying the Xa21 resistant gene, when compared to H2O-treated rice (Figure 5). It has been reported that resistant rice cultivars tend to possess higher endogenous SA content relative to their susceptible counterparts [41]. Moreover, in resistant rice cultivars, SA production increases following Xoo inoculation, whereas it remains relatively stable in susceptible rice cultivars [10]. Our study further reveals that OsPal2, an SA biosynthesis gene, exhibited upregulation at 24 h after the second SA application (0 MAI) in susceptible cultivars (“PSL2”), while maintaining steady expression in resistant cultivars (“IRBB21” and hybrid lines), when compared to the control (Figure 6d). These observations suggest that exogenous SA spraying may not significantly impact SAR induction in resistant rice cultivars, as they already possess elevated endogenous SA content before inoculation and have the capability to amplify endogenous SA production post-inoculation. However, this hypothesis requires validation in future studies to elucidate the specific genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying these responses.

In rice, the Xoo-receptor-like kinase (XRLK) protein encoded by the OsXa21 gene plays a pivotal role in the plant’s immune response. This protein facilitates the recognition of pathogen ligands, thus initiating signaling pathways that lead to the expression of defense genes orchestrated by OsXa21 [42,43]. XRLK, in particular, assumes a critical function in phosphorylation events that trigger responses to pathogen-associated molecular patterns during Xoo infection in rice [43]. Previous research has highlighted that the Xa21 gene in rice directly identifies the type I-secreted protein produced by Xoo during infection, conferring resistance against various strains of Xoo [44,45]. Our study sheds light on the capability of SA application to activate the expression of the OsXa21 gene in “IRBB21” and “PSL2-Xa21-L1” (Figure 6a). This aligns with previous reports, such as those by Ohtake et al. [46], which demonstrated that SA treatment in A. thaliana triggered the expression of RLK genes like RKC1, HAESA, RKF1, ARK1, and RLK1, all belonging to the XRLK protein family. However, the connection between SA and OsXa21 in rice remains largely unexplored. Notably, only a solitary publication has illuminated that SA application can induce the expression of Osxa5, enhancing BB disease resistance against the Xoo strain PXO86 in the “IRBB5” rice cultivar [10]. Our findings underscore the potential of SA to modulate the expression of key resistance genes such as OsXa21, contributing to the plant’s defense mechanisms against Xoo. These suggest that SA might play a broader role in the regulation of receptor-like kinases in rice, akin to its effects observed in Arabidopsis. Future studies should delve deeper into the molecular interplay between SA and XRLK proteins in rice, aiming to uncover the underlying mechanisms and potential applications in crop production strategies.

The OsNPR1 protein functions as an SA receptor and serves as a positive regulator of local and SAR responses against pathogens [47,48]. As depicted in Figure 6c, the expression of OsNPR1 increased following Xoo infection at 120 and 180 MAI in both SA-treated and H2O-treated rice cultivars. This suggests that while exogenous SA application might not directly regulate OsNPR1 expression, Xoo infection induces upregulation of OsNPR1 expression. Currently, there are no reports demonstrating that exogenous SA application directly triggers OsNPR1 gene expression. However, recent studies have indicated a significant rise in endogenous SA levels within cells upon pathogen invasion [49]. Consistent with previous research, it has been established that intracellular SA accumulation can prompt the recognition of hormone response-related elements within the promoter region of OsNPR1, consequently enhancing OsNPR1 gene expression [47,50]. Furthermore, our results indicate a substantial elevation of OsNPR1 expression in the resistant rice cultivar “IRBB21” compared to the susceptible “PSL2.” Similar findings have been reported in studies investigating OsNPR1 overexpression lines, which demonstrated a significant enhancement in rice resistance against the Xoo strain PXO99A, compared to the wild-type Japonica rice cultivar “Taipei 309” [51]. Those observations underscore the crucial role of OsNPR1 in mediating resistance responses in rice.

The OsPal gene, responsible for encoding the PAL enzyme, emerges as a significant defensive element contributing to rice’s resistance mechanism against Xoo [52]. This gene plays a role in regulating endogenous SA levels, which are vital for the SAR defense mechanism following Xoo infection in rice [53]. Our findings reveal that pretreatment with SA substantially elevated the expression of the OsPal2 gene at 0 MAI in the susceptible rice cultivar “PSL2,” compared to the H2O-treated group (Figure 6d). This suggests that SA-treated susceptible rice (“PSL2”) exhibited a modulated OsPal2 gene expression. Similar trends have been observed in other studies, where exogenous SA application triggered an upregulation in OsPal gene expression, concurrently leading to an increase in PAL accumulation in grape berry plants [54]. Moreover, Solekha et al. [52] reported that Xoo-infected black rice plants (“Pari Ireng” and “Melik” rice cultivars) demonstrated an enhancement of PAL enzyme levels and BB resistance, further emphasizing the role of PAL enzyme as an essential component of the rice’s defense mechanisms. The upregulation of OsPal in response to SA treatment and Xoo infection underscores its importance in the biosynthesis of SA and activation of defense pathways. Elucidating the regulatory mechanisms of OsPal and its interaction with other components of the SA signaling pathway could provide a better understanding of its role in plant immunity. This knowledge could lead to new strategies for enhancing disease resistance in rice and other crops.

5 Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the application of 2 mM SA to the susceptible rice cultivar “PSL2” using Method Ⅰ (SA-sprayed once daily over 2 consecutive days on the whole plant before Xoo inoculation) is an optimal treatment for inducing resistance against BB disease. This treatment effectively reduces lesion length and mitigates symptomatic appearances at 14 DAI. Although SA treatment did not influence the proliferation of Xoo at 3 DAI, rice cultivars subjected to SA treatment, particularly the susceptible “PSL2” cultivar, exhibited improved resistance to BB disease symptoms. These treated cultivars showed a notable reduction in lesion length at 14 DAI compared to the H2O-treated group. Additionally, the results revealed that SA treatment led to an increase in the expression of the OsXa21 gene solely in the “IRBB21” and “PSL2-Xa21-L2” rice cultivars at 0 DAI. The SA elicitor also stimulated the induction of OsPal2 gene expression in “PSL2” rice cultivars. However, no apparent correlation was observed between SA treatment and the expression of the OsWRKY45 and OsNPR1 genes. The finding highlights the potential of SA as an environmentally friendly and cost-effective elicitor for managing BB disease in rice, particularly in susceptible cultivars. Nonetheless, this study has limitations, including the absence of field trials to validate SA’s effectiveness in diverse agricultural environments and its varying efficacy against different Xoo strains. Future research should focus on large-scale field trials to assess the practical utility of SA in real-world settings and explore its potential integration into sustainable disease management strategies. Additionally, uncovering the underlying mechanisms of the interaction between the Xa21 and SA signaling pathways will provide deeper insight into optimizing BB resistance in rice. Such efforts will enhance the practical applications of SA treatment and its contribution to global food security.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our appreciation to the Tuition Fee Grant for graduate students in the Faculty of Science at Naresuan University, which covered Mr. N. Meesa’s tuition expenses.

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by The Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) Grant No. FRB650022/0179, Naresuan University Grant No. R2565B007, and the Global and Frontier Research University Fund, Naresuan University Grant No. R2566C051.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. NM: investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing – original draft; WL: investigation; KR, TR, and KB: methodology, writing – review and editing; KS: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing – review and editing, resources, supervision; PI: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, validation, writing – review and editing, resources, project administration, funding acquisition.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data will be provided upon request.

References

[1] FAOSTAT. Crops and livestock products Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Cham: Springer; 2021. Accessed : 18-July-2023 http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC/visualize.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Yasmin S, Hafeez FY, Mirza MS, Rasul M, Arshad HMI, Zubair M, et al. Biocontrol of bacterial leaf blight of rice and profiling of secondary metabolites produced by rhizospheric Pseudomonas aeruginosa BRp3. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1895. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01895.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Thanh TL, Thumanu K, Wongkaew S, Boonkerd N, Teaumroong N, Phansak P, et al. Salicylic acid-induced accumulation of biochemical components associated with resistance against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice. J Plant Interact. 2017;12:108–20. 10.1080/17429145.2017.1291859.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Peng H, Chen Z, Fang Z, Zhou J, Xia Z, Gao L, et al. Rice Xa21 primed genes and pathways that are critical for combating bacterial blight infection. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):12165. 10.1038/srep12165.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Liu F, McDonald M, Schwessinger B, Joe A, Pruitt R, Erickson T, et al. Variation and inheritance of the Xanthomonas raxX‐raxSTAB gene cluster required for activation of XA21‐mediated immunity. Mol Plant Pathol. 2019;20(5):656–72. 10.1111/mpp.12783.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Fiyaz RA, Shivani D, Chaithanya K, Mounika K, Chiranjeevi M, Laha GS, et al. Genetic improvement of rice for bacterial blight resistance: Present status and future prospects. Rice Sci. 2022;29(2):118–32. 10.1016/j.rsci.2021.08.002.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Ercoli MF, Luu DD, Rim EY, Shigenaga A, Teixeira de Araujo Jr A, Chern M, et al. Plant immunity: Rice XA21-mediated resistance to bacterial infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2022;119(8):e2121568119. 10.1073/pnas.2121568119.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Liang B, Wang H, Yang C, Wang L, Qi L, Guo Z, et al. Salicylic acid is required for broad-spectrum disease resistance in rice. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1354. 10.3390/ijms23031354.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Bimolata W, Kumar A, Reddy MSK, Sundaram RM, Laha GS, Qureshi IA, et al. Nucleotide diversity analysis of three major bacterial blight resistance genes in rice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120186. 10.1371/journal.pone.0120186.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Jiang G, Yin D, Shi Y, Zhou Z, Li C, Liu P, et al. OsNPR3. 3-dependent salicylic acid signaling is involved in recessive gene xa5-mediated immunity to rice bacterial blight. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):6313. 10.1038/s41598-020-63059-8.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Schwessinger B, Ronald PC. Review plant innate immunity: Perception of conserved microbial signatures. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012;63:451–82. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105518.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Duan C, Yu J, Bai J, Zhu Z, Wang X. Induced defense responses in rice plants against small brown planthopper infestation. Crop J. 2014;2(1):55–62. 10.1016/j.cj.2013.12.001.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Buddhachat K, Ritbamrung O, Sripairoj N, Inthima P, Ratanasut K, Boonsrangsom T, et al. One-step colorimetric LAMP (cLAMP) assay for visual detection of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice. Crop Prot. 2021;150:105809. 10.1016/j.cropro.2021.105809.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ke Y, Hui S, Yuan M. Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae inoculation and growth rate on rice by leaf clipping method. Bio-protocol. 2017;7(19):e2568. 10.21769/BioProtoc.2568.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Sagun CM, Grandmottet F, Suachaowna N, Sujipuli K, Ratanasut K. Validation of suitable reference genes for normalization of quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction in rice infected by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Plant Gene. 2020;21:100217. 10.1016/j.plgene.2019.100217.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Promma P, Grandmottet F, Ratanasut K. Characterisation of Xa21 and defence-related gene expression in RD47 × IRBB21 hybrid rice subject to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. In Proceedings of The National and International Graduate Research Conference 2016, Khon Kaen, Thailand; 2016. p. 1485–93.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Park SR, Kim HS, Lee KS, Hwang DJ, Bae SC, Ahn IP, et al. Overexpression of rice NAC transcription factor OsNAC58 on increased resistance to bacterial leaf blight. J Plant Biotechnol. 2017;44:149–55. 10.5010/JPB.2017.44.2.149.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Lu FF, Liu JT, Zhang N, Chen ZJ, Yang H. OsPAL as a key salicylic acid synthetic component is a critical factor involved in mediation of isoproturon degradation in a paddy crop. J Clean Prod. 2020;262:121476. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121476.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Postma M, Goedhart J. PlotsOfData—A web app for visualizing data together with their summaries. PLoS Biol. 2019;17(3):e3000202. 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000202.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Singewar K, Fladung M, Robischon M. Methyl salicylate as a signaling compound that contributes to forest ecosystem stability. Trees. 2021;35:1755–69. 10.1007/s00468-021-02191-y.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Vlot AC, Dempsey DMA, Klessig DF. Salicylic acid, a multifaceted hormone to combat disease. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2009;47:177–206. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.050908.135202.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Kalaivani K, Maruthi-Kalaiselvi M, Senthil-Nathan S. Seed treatment and foliar application of methyl salicylate (MeSA) as a defense mechanism in rice plants against the pathogenic bacterium, Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2021;171:104718. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2020.104718.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Liu PP, von Dahl CC, Klessig DF. The extent to which methyl salicylate is required for signaling systemic acquired resistance is dependent on exposure to light after infection. Plant Physiol. 2011;157(4):2216–26. 10.1104/pp.111.187773.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Gondor OK, Pal M, Janda T, Szalai G. The role of methyl salicylate in plant growth under stress conditions. J Plant Physiol. 2022;277:153809. 10.1016/j.jplph.2022.153809.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Shasmita D, Mohapatra PK, Naik SK, Mukherjee AK. Priming with salicylic acid induces defense against bacterial blight disease by modulating rice plant photosystem II and antioxidant enzymes activity. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2019;108:101427. 10.1016/j.pmpp.2019.101427.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Thepbandit W, Papathoti NK, Daddam JR, Thumanu K, Siriwong S, Thanh TL, et al. Identification of salicylic acid mechanism against leaf blight disease in Oryza sativa by SR-FTIR microspectroscopic and docking studies. Pathogens. 2021;10(6):652. 10.3390/pathogens10060652.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Vimala R, Suriachandraselvan M. Induced resistance in bhendi against powdery mildew by foliar application of salicylic acid. J Biopestic. 2009;2(1):111–4.10.57182/jbiopestic.2.1.111-114Search in Google Scholar

[29] El-Shazly MA, Attia YA, Kabil FF, Anis E, Hazman M. Inhibitory effects of salicylic acid and silver nanoparticles on potato virus Y-infected potato plants in Egypt. Middle East J Agric Res. 2017;6(3):835–48.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Thepbandit W, Buensanteai N, Thumanu K, Siriwong S, Toan Le T, Athinuwat D. Salicylic acid elicitor inhibiting Xanthomonas oryzae growth, motility, biofilm, polysaccharides production, and biochemical components during pathogenesis on rice. Chiang Mai J Sci. 2021;48:341–53.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Radojicic A, Li X, Zhang Y. Salicylic acid: A double-edged sword for programed cell death in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1133. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01133.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[32] Kamle M, Borah R, Bora H, Jaiswal AK, Singh RK, Kumar P. Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and induced systemic resistance (ISR): Role and mechanism of action against phytopathogens. Fungal biotechnology and bioengineering; 2020. p. 457–70. 10.1007/978-3-030-41870-0_20.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Li T, Huang Y, Xu ZS, Wang F, Xiong AS. Salicylic acid-induced differential resistance to the Tomato yellow leaf curl virus among resistant and susceptible tomato cultivars. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19(1):1–14. 10.1186/s12870-019-1784-0.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Leiwakabessy C, Sinaga MS, Mutaqien KH, Trikoesoemaningtyas T, Giyanto G. The endophytic bacteria, salicylic acid, and their combination as inducers of rice resistance against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. AGRIVITA. 2017;40(1):25–35. 10.17503/agrivita.v40i1.1029.Search in Google Scholar

[35] Kouzai Y, Kimura M, Watanabe M, Kusunoki K, Osaka D, Suzuki T, et al. Salicylic acid-dependent immunity contributes to resistance against Rhizoctonia solani, a necrotrophic fungal agent of sheath blight, in rice and Brachypodium distachyon. N Phytol. 2018;217(2):771–83. 10.1111/nph.14849.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Salman EK, Ghoniem KE, Badr ES, Emeran AA. The potential of dimetindene maleate inducing resistance to blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae through activating the salicylic acid signaling pathway in rice plants. Pest Manag Sci. 2022;78(2):633–42. 10.1002/ps.6673.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Elsharkawy MM, Omara RI, Mostafa YS, Alamri SA, Hashem M, Alrumman SA, et al. Mechanism of wheat leaf rust control using chitosan nanoparticles and salicylic acid. J Fungi. 2022;8(3):304. 10.3390/jof8030304.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Ratchaseema MTN, Kladsuwan L, Soulard L, Swangmaneecharern P, Punpee P, Klomsa-Ard P, et al. The role of salicylic acid and benzothiadiazole in decreasing phytoplasma titer of sugarcane white leaf disease. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):15211. 10.1038/s41598-021-94746-9.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Czajkowski R, van der Wolf JM, Krolicka A, Ozymko Z, Narajczyk M, Kaczynska N, et al. Salicylic acid can reduce infection symptoms caused by Dickeya solani in tissue culture grown potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) plants. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2015;141:545–58. 10.1007/s10658-014-0561-z.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Yang L, Li B, Zheng XY, Li J, Yang M, Dong X, et al. Salicylic acid biosynthesis is enhanced and contributes to increased biotrophic pathogen resistance in Arabidopsis hybrids. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):7309. 10.1038/ncomms8309.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Silverman P, Seskar M, Kanter D, Schweizer P, Métraux J, Raskin I. Salicylic acid in rice (biosynthesis, conjugation, and possible role). Plant Physiol. 1995;108(2):633–9. 10.1104/pp.108.2.633.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Century KS, Lagman RA, Adkisson M, Morlan J, Tobias R, Schwartz K, et al. Developmental control of Xa21-mediated disease resistance in rice. Plant J. 1999;20(2):231–6. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00589.x.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Pruitt RN, Schwessinger B, Joe A, Thomas N, Liu F, Albert M, et al. The rice immune receptor XA21 recognizes a tyrosine-sulfated protein from a Gram-negative bacterium. Sci Adv. 2015;1(6):e1500245. 10.1126/sciadv.1500245.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Rashid MM, Nihad SAI, Khan MAI, Haque A, Ara A, Ferdous T, et al. Pathotype profiling, distribution and virulence analysis of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae causing bacterial blight disease of rice in Bangladesh. J Phytopathol. 2021;169(7-8):438–46. 10.1111/jph.13000.Search in Google Scholar

[45] Jiang N, Yan J, Liang Y, Shi Y, He Z, Wu Y, et al. Resistance genes and their interactions with bacterial blight/leaf streak pathogens (Xanthomonas oryzae) in rice (Oryza sativa L.)—an updated review. Rice. 2020;13(1):1–12. 10.1186/s12284-019-0358-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Ohtake Y, Takahashi T, Komeda Y. Salicylic acid induces the expression of a number of receptor-like kinase genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41(9):1038–44. 10.1093/pcp/pcd028.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Ding Y, Sun T, Ao K, Peng Y, Zhang Y, Li X, et al. Opposite roles of salicylic acid receptors NPR1 and NPR3/NPR4 in transcriptional regulation of plant immunity. Cell. 2018;173(6):1454–67. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.044.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Backer R, Naidoo S, Van den Berg N. The nonexpressor of pathogenesis-related genes 1 (NPR1) and related family: mechanistic insights in plant disease resistance. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:102. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00102.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Rekhter D, Lüdke D, Ding Y, Feussner K, Zienkiewicz K, Lipka V, et al. Isochorismate-derived biosynthesis of the plant stress hormone salicylic acid. Science. 2019;365(6452):498–502. 10.1126/science.aaw1720.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[50] Jiang D, Yang G, Chen K, Yu P, Chen J, Luo Y, et al. Identification and functional characterization of the Nonexpressor of pathogenesis-related genes 1 (NPR1) gene in the tea plant (Camellia sinensis). Forests. 2023;14(8):1578. 10.3390/f14081578.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Dai X, Wang Y, Yu K, Zhao Y, Xiong L, Wang R, et al. OsNPR1 enhances rice resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae by upregulating rice defense genes and repressing bacteria virulence genes. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(10):8687. 10.3390/ijms24108687.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Solekha R, Susanto FA, Joko T, Nuringtyas TR, Purwestri YA. Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) contributes to the resistance of black rice against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. J Plant Pathol. 2020;102:359–65. 10.1007/s42161-019-00426-z.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Song A, Xue G, Cui P, Fan F, Liu H, Yin C, et al. The role of silicon in enhancing resistance to bacterial blight of hydroponic-and soil-cultured rice. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):24640. 10.1038/srep24640.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Wen PF, Chen JY, Kong WF, Pan QH, Wan SB, Huang WD. Salicylic acid induced the expression of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene in grape berry. Plant Sci. 2005;169(5):928–34. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.06.011.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants

- Assessment of nutrition status of pineapple plants during ratoon season using diagnosis and recommendation integrated system

- Nutritional value and consumer assessment of 12 avocado crosses between cvs. Hass × Pionero

- The lacked access to beef in the low-income region: An evidence from the eastern part of Indonesia

- Comparison of milk consumption habits across two European countries: Pilot study in Portugal and France

- Antioxidant responses of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages

- Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

- Yield and vegetation index of different maize varieties and nitrogen doses under normal irrigation

- Urbanization and forecast possibilities of land use changes by 2050: New evidence in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam

- Organizational-economic efficiency of raspberry farming – case study of Kosovo

- Application of nitrogen-fixing purple non-sulfur bacteria in improving nitrogen uptake, growth, and yield of rice grown on extremely saline soil under greenhouse conditions

- Digital motivation, knowledge, and skills: Pathways to adaptive millennial farmers

- Investigation of biological characteristics of fruit development and physiological disorders of Musang King durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.)

- Enhancing rice yield and farmer welfare: Overcoming barriers to IPB 3S rice adoption in Indonesia

- Simulation model to realize soybean self-sufficiency and food security in Indonesia: A system dynamic approach

- Gender, empowerment, and rural sustainable development: A case study of crab business integration

- Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses of bacterial communities in short mackerel (Rastrelliger brachysoma) under storage conditions and inoculation of the histamine-producing bacterium

- Fostering women’s engagement in good agricultural practices within oil palm smallholdings: Evaluating the role of partnerships

- Increasing nitrogen use efficiency by reducing ammonia and nitrate losses from tomato production in Kabul, Afghanistan

- Physiological activities and yield of yacon potato are affected by soil water availability

- Vulnerability context due to COVID-19 and El Nino: Case study of poultry farming in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Wheat freshness recognition leveraging Gramian angular field and attention-augmented resnet

- Suggestions for promoting SOC storage within the carbon farming framework: Analyzing the INFOSOLO database

- Optimization of hot foam applications for thermal weed control in perennial crops and open-field vegetables

- Toxicity evaluation of metsulfuron-methyl, nicosulfuron, and methoxyfenozide as pesticides in Indonesia

- Fermentation parameters and nutritional value of silages from fodder mallow (Malva verticillata L.), white sweet clover (Melilotus albus Medik.), and their mixtures

- Five models and ten predictors for energy costs on farms in the European Union

- Effect of silvopastoral systems with integrated forest species from the Peruvian tropics on the soil chemical properties

- Transforming food systems in Semarang City, Indonesia: A short food supply chain model

- Understanding farmers’ behavior toward risk management practices and financial access: Evidence from chili farms in West Java, Indonesia

- Optimization of mixed botanical insecticides from Azadirachta indica and Calophyllum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda using response surface methodology

- Mapping socio-economic vulnerability and conflict in oil palm cultivation: A case study from West Papua, Indonesia

- Exploring rice consumption patterns and carbohydrate source diversification among the Indonesian community in Hungary

- Determinants of rice consumer lexicographic preferences in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

- Effect on growth and meat quality of weaned piglets and finishing pigs when hops (Humulus lupulus) are added to their rations

- Healthy motivations for food consumption in 16 countries

- The agriculture specialization through the lens of PESTLE analysis

- Combined application of chitosan-boron and chitosan-silicon nano-fertilizers with soybean protein hydrolysate to enhance rice growth and yield

- Stability and adaptability analyses to identify suitable high-yielding maize hybrids using PBSTAT-GE

- Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-mediated rock phosphate utilization with poultry manure enhances soil nutrient dynamics and maize growth in semi-arid soil

- Factors impacting on purchasing decision of organic food in developing countries: A systematic review

- Influence of flowering plants in maize crop on the interaction network of Tetragonula laeviceps colonies

- Bacillus subtilis 34 and water-retaining polymer reduce Meloidogyne javanica damage in tomato plants under water stress

- Vachellia tortilis leaf meal improves antioxidant activity and colour stability of broiler meat

- Evaluating the competitiveness of leading coffee-producing nations: A comparative advantage analysis across coffee product categories

- Application of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LP5 in vacuum-packaged cooked ham as a bioprotective culture

- Evaluation of tomato hybrid lines adapted to lowland

- South African commercial livestock farmers’ adaptation and coping strategies for agricultural drought

- Spatial analysis of desertification-sensitive areas in arid conditions based on modified MEDALUS approach and geospatial techniques

- Meta-analysis of the effect garlic (Allium sativum) on productive performance, egg quality, and lipid profiles in laying quails

- Optimizing carrageenan–citric acid synergy in mango gummies using response surface methodology

- The strategic role of agricultural vocational training in sustainable local food systems

- Agricultural planning grounded in regional rainfall patterns in the Colombian Orinoquia: An essential step for advancing climate-adapted and sustainable agriculture

- Perspectives of master’s graduates on organic agriculture: A Portuguese case study

- Developing a behavioral model to predict eco-friendly packaging use among millennials

- Government support during COVID-19 for vulnerable households in Central Vietnam

- Citric acid–modified coconut shell biochar mitigates saline–alkaline stress in Solanum lycopersicum L. by modulating enzyme activity in the plant and soil

- Herbal extracts: For green control of citrus Huanglongbing

- Research on the impact of insurance policies on the welfare effects of pork producers and consumers: Evidence from China

- Investigating the susceptibility and resistance barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars against the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia)

- Characterization of promising enterobacterial strains for silver nanoparticle synthesis and enhancement of product yields under optimal conditions

- Testing thawed rumen fluid to assess in vitro degradability and its link to phytochemical and fibre contents in selected herbs and spices

- Protein and iron enrichment on functional chicken sausage using plant-based natural resources

- Fruit and vegetable intake among Nigerian University students: patterns, preferences, and influencing factors

- Bioprospecting a plant growth-promoting and biocontrol bacterium isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico: Paenibacillus sp. strain TSM33

- Quantifying urban expansion and agricultural land conversion using spatial indices: evidence from the Red River Delta, Vietnam

- LEADER approach and sustainability overview in European countries

- Influence of visible light wavelengths on bioactive compounds and GABA contents in barley sprouts

- Assessing Albania’s readiness for the European Union-aligned organic agriculture expansion: a mixed-methods SWOT analysis integrating policy, market, and farmer perspectives

- Genetically modified foods’ questionable contribution to food security: exploring South African consumers’ knowledge and familiarity

- The role of global actors in the sustainability of upstream–downstream integration in the silk agribusiness

- Multidimensional sustainability assessment of smallholder dairy cattle farming systems post-foot and mouth disease outbreak in East Java, Indonesia: a Rapdairy approach

- Enhancing azoxystrobin efficacy against Pythium aphanidermatum rot using agricultural adjuvants

- Review Articles

- Reference dietary patterns in Portugal: Mediterranean diet vs Atlantic diet

- Evaluating the nutritional, therapeutic, and economic potential of Tetragonia decumbens Mill.: A promising wild leafy vegetable for bio-saline agriculture in South Africa

- A review on apple cultivation in Morocco: Current situation and future prospects

- Quercus acorns as a component of human dietary patterns

- CRISPR/Cas-based detection systems – emerging tools for plant pathology

- Short Communications

- An analysis of consumer behavior regarding green product purchases in Semarang, Indonesia: The use of SEM-PLS and the AIDA model

- Effect of NaOH concentration on production of Na-CMC derived from pineapple waste collected from local society

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants

- Assessment of nutrition status of pineapple plants during ratoon season using diagnosis and recommendation integrated system

- Nutritional value and consumer assessment of 12 avocado crosses between cvs. Hass × Pionero

- The lacked access to beef in the low-income region: An evidence from the eastern part of Indonesia

- Comparison of milk consumption habits across two European countries: Pilot study in Portugal and France

- Antioxidant responses of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages

- Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

- Yield and vegetation index of different maize varieties and nitrogen doses under normal irrigation

- Urbanization and forecast possibilities of land use changes by 2050: New evidence in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam

- Organizational-economic efficiency of raspberry farming – case study of Kosovo

- Application of nitrogen-fixing purple non-sulfur bacteria in improving nitrogen uptake, growth, and yield of rice grown on extremely saline soil under greenhouse conditions

- Digital motivation, knowledge, and skills: Pathways to adaptive millennial farmers

- Investigation of biological characteristics of fruit development and physiological disorders of Musang King durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.)

- Enhancing rice yield and farmer welfare: Overcoming barriers to IPB 3S rice adoption in Indonesia

- Simulation model to realize soybean self-sufficiency and food security in Indonesia: A system dynamic approach

- Gender, empowerment, and rural sustainable development: A case study of crab business integration

- Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses of bacterial communities in short mackerel (Rastrelliger brachysoma) under storage conditions and inoculation of the histamine-producing bacterium

- Fostering women’s engagement in good agricultural practices within oil palm smallholdings: Evaluating the role of partnerships

- Increasing nitrogen use efficiency by reducing ammonia and nitrate losses from tomato production in Kabul, Afghanistan

- Physiological activities and yield of yacon potato are affected by soil water availability

- Vulnerability context due to COVID-19 and El Nino: Case study of poultry farming in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Wheat freshness recognition leveraging Gramian angular field and attention-augmented resnet

- Suggestions for promoting SOC storage within the carbon farming framework: Analyzing the INFOSOLO database

- Optimization of hot foam applications for thermal weed control in perennial crops and open-field vegetables

- Toxicity evaluation of metsulfuron-methyl, nicosulfuron, and methoxyfenozide as pesticides in Indonesia

- Fermentation parameters and nutritional value of silages from fodder mallow (Malva verticillata L.), white sweet clover (Melilotus albus Medik.), and their mixtures

- Five models and ten predictors for energy costs on farms in the European Union

- Effect of silvopastoral systems with integrated forest species from the Peruvian tropics on the soil chemical properties

- Transforming food systems in Semarang City, Indonesia: A short food supply chain model

- Understanding farmers’ behavior toward risk management practices and financial access: Evidence from chili farms in West Java, Indonesia

- Optimization of mixed botanical insecticides from Azadirachta indica and Calophyllum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda using response surface methodology

- Mapping socio-economic vulnerability and conflict in oil palm cultivation: A case study from West Papua, Indonesia

- Exploring rice consumption patterns and carbohydrate source diversification among the Indonesian community in Hungary

- Determinants of rice consumer lexicographic preferences in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

- Effect on growth and meat quality of weaned piglets and finishing pigs when hops (Humulus lupulus) are added to their rations

- Healthy motivations for food consumption in 16 countries

- The agriculture specialization through the lens of PESTLE analysis

- Combined application of chitosan-boron and chitosan-silicon nano-fertilizers with soybean protein hydrolysate to enhance rice growth and yield

- Stability and adaptability analyses to identify suitable high-yielding maize hybrids using PBSTAT-GE

- Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-mediated rock phosphate utilization with poultry manure enhances soil nutrient dynamics and maize growth in semi-arid soil

- Factors impacting on purchasing decision of organic food in developing countries: A systematic review

- Influence of flowering plants in maize crop on the interaction network of Tetragonula laeviceps colonies

- Bacillus subtilis 34 and water-retaining polymer reduce Meloidogyne javanica damage in tomato plants under water stress

- Vachellia tortilis leaf meal improves antioxidant activity and colour stability of broiler meat

- Evaluating the competitiveness of leading coffee-producing nations: A comparative advantage analysis across coffee product categories

- Application of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LP5 in vacuum-packaged cooked ham as a bioprotective culture

- Evaluation of tomato hybrid lines adapted to lowland

- South African commercial livestock farmers’ adaptation and coping strategies for agricultural drought

- Spatial analysis of desertification-sensitive areas in arid conditions based on modified MEDALUS approach and geospatial techniques

- Meta-analysis of the effect garlic (Allium sativum) on productive performance, egg quality, and lipid profiles in laying quails

- Optimizing carrageenan–citric acid synergy in mango gummies using response surface methodology

- The strategic role of agricultural vocational training in sustainable local food systems

- Agricultural planning grounded in regional rainfall patterns in the Colombian Orinoquia: An essential step for advancing climate-adapted and sustainable agriculture

- Perspectives of master’s graduates on organic agriculture: A Portuguese case study

- Developing a behavioral model to predict eco-friendly packaging use among millennials

- Government support during COVID-19 for vulnerable households in Central Vietnam

- Citric acid–modified coconut shell biochar mitigates saline–alkaline stress in Solanum lycopersicum L. by modulating enzyme activity in the plant and soil

- Herbal extracts: For green control of citrus Huanglongbing

- Research on the impact of insurance policies on the welfare effects of pork producers and consumers: Evidence from China

- Investigating the susceptibility and resistance barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars against the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia)

- Characterization of promising enterobacterial strains for silver nanoparticle synthesis and enhancement of product yields under optimal conditions

- Testing thawed rumen fluid to assess in vitro degradability and its link to phytochemical and fibre contents in selected herbs and spices

- Protein and iron enrichment on functional chicken sausage using plant-based natural resources

- Fruit and vegetable intake among Nigerian University students: patterns, preferences, and influencing factors

- Bioprospecting a plant growth-promoting and biocontrol bacterium isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico: Paenibacillus sp. strain TSM33

- Quantifying urban expansion and agricultural land conversion using spatial indices: evidence from the Red River Delta, Vietnam

- LEADER approach and sustainability overview in European countries

- Influence of visible light wavelengths on bioactive compounds and GABA contents in barley sprouts

- Assessing Albania’s readiness for the European Union-aligned organic agriculture expansion: a mixed-methods SWOT analysis integrating policy, market, and farmer perspectives

- Genetically modified foods’ questionable contribution to food security: exploring South African consumers’ knowledge and familiarity

- The role of global actors in the sustainability of upstream–downstream integration in the silk agribusiness

- Multidimensional sustainability assessment of smallholder dairy cattle farming systems post-foot and mouth disease outbreak in East Java, Indonesia: a Rapdairy approach

- Enhancing azoxystrobin efficacy against Pythium aphanidermatum rot using agricultural adjuvants

- Review Articles

- Reference dietary patterns in Portugal: Mediterranean diet vs Atlantic diet

- Evaluating the nutritional, therapeutic, and economic potential of Tetragonia decumbens Mill.: A promising wild leafy vegetable for bio-saline agriculture in South Africa

- A review on apple cultivation in Morocco: Current situation and future prospects

- Quercus acorns as a component of human dietary patterns

- CRISPR/Cas-based detection systems – emerging tools for plant pathology

- Short Communications

- An analysis of consumer behavior regarding green product purchases in Semarang, Indonesia: The use of SEM-PLS and the AIDA model

- Effect of NaOH concentration on production of Na-CMC derived from pineapple waste collected from local society