Optimization of mixed botanical insecticides from Azadirachta indica and Calophyllum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda using response surface methodology

-

Edy Syahputra

, Danar Dono

, Sudarjat

Abstract

The ratio of ingredients in the mixture of botanical insecticides affects the insecticide activity. This study conducted a single and mixed insecticide test of Azadirachta indica and Callophylum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda. Insecticide application used the residue method on leaves with a microsyringe and acetone + methanol solvent (4:1). The test concentration was based on the preliminary tests. Optimization of the ratio between A. indica and C. soulattri was carried out using response surface methods. The test results showed that the LC50 and LC95 values of the single insecticides A. indica and C. soulattri were 0.099, 0.420 and 0.537, 3.481%, respectively. The response surface method optimization showed that the ratio between A. indica and C. soulattri resulted in the highest mortality and the lowest feed consumption at 2.0800:1.1657. The LC50 and LC95 values of the mixed insecticide were 0.030 and 0.224%, respectively. The mixed insecticide of A. indica and C. soulattri has strong synergy at LC50 and weak synergy at LC95. The mixed insecticides of A. indica and C. soulattri can be used as an alternative environmentally friendly control against S. frugiperda in maize fields.

1 Introduction

The use and exploration of botanical insecticides as an alternative pest control continues to grow worldwide, including in Indonesia. The literature studies show that from 1993 to 2019, 94 types of plants were used as insecticides, with 6 main types of plants widely reported for pest control: Annona muricata, Azadirachta indica, Nicotiana tabacum, Carica papaya, and Cymbopogon nardus [1]. A. indica oil has been reported to suppress feed consumption with an LC50 value of 0.08% against Spodoptera frugiperda Smith at 16 days after treatment [2] and an LC50 of 0.68% at 12 h after treatment [3]. Other reports also show that it caused mortality of Sitophilus oryzae by 76.5% at a concentration of 10% (10 g/100 g of rice) [4]. This shows the potential of A. indica to control pests in crops and warehouses.

Reports of the effectiveness of A. indica in the form of active ingredients, extracts, and formulations have been widely reported. Azadirachtin (active ingredient of A. indica) has strong feeding and growth inhibitory activity and can interfere with the central nervous system of Drosophila [5,6]. Neem oil (pressed) has toxicity with an LC50 value of 0.039% against S. frugiperda [7], and in the formulation (50% active ingredient), it has an LC50 of 0.8% against Crocodolomia pavonana [8]. The difference in activity between active ingredients, extracts, and formulations differs based on the target pests and materials used [9,10,11]. In addition, the main constituents of commercial formulations of azadirachtin in the world market used for the control of agricultural insect pests are available [12].

Calophyllum soulattri Burm. f. is one of the plants with insecticidal properties that grows in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. C. soulattri was first reported by Syahputra et al. [13] against Crocidolomia pavonana (LC50 0.04%). C. soulattri was confirmed to have compounds from the triterpenoid group as insecticides, and soulattrin compounds that have cytotoxic activity were reported to have antibacterial activity [14,15,16]. Ethanol extract from C. soulattri bark was also reported to have an LC50 value of 0.349% against S. frugiperda [17]. C. soulattri is also reported to have active ingredients calosubellinone and garsubellin B, which have potential activity as an anticancer agent [18,19]. However, reports as an insecticide and effectiveness against other pests are still limited.

S. frugiperda is reported to be an invasive pest and causes quite high losses to maize plants in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. The moth can fly optimally for up to 10 h/night or a flight distance of 63.73 km with a speed of 2.73 km/h, so the spread in coastal areas is higher than in inland areas [20,21]. Plant damage reached 85–100% in East Nusa Tenggara and Lampung provinces and 34–52.7% in West Java, Indonesia [22,23,24]. Losses in maize production due to S. frugiperda reached $2531–6312 million in Africa, and the cost of control using synthetic insecticides reached US$ 1.30 for 100 kg of maize seeds [25,26]. S. frugiperda has 353 host plants from 76 plant families [27]. This causes the survival ability of S. frugiperda to be relatively high, and proper control is needed to reduce the population size and losses caused.

An insecticide mixture is one solution that increases insecticide toxicity. A mixture of C. soulattri with Sesamum indicum shows synergistic properties against S. frugiperda at a ratio of 4:1, but it is antagonistic in its mixture with Piper aduncum at a ratio of 1:2 [17]. A mixture of Piper sarmentosum and A. indica at ratios of 1:9, 2:8, 3:7, and 4:6 is antagonistic, while at a ratio of 5:5, it is addictive. Meanwhile, at ratios of 6:4; 7:3; 8:2 and 9:1, it is synergistic in LC50 values [28]. This shows that the ratio between mixtures determines the properties of the insecticide mixture.

Optimization of the mixture ratio between insecticide ingredients can be done using the response surface method (RSM). RSM is a set of mathematical and statistical techniques used to model and analyze problems where the desired response is influenced by multiple variables, aiming to optimize that response [29]. The use of RSM to determine the optimization of botanical insecticides is still limited. One of the uses of RSM was reported to optimize the conditions of neem seed oil, emulsifier, and water to reduce the weight reduction of pests and optimize the pesticide activity of Chrysanthemum coronarium and A. indica in the form of nanosuspension [30,31]. The mixture of C. soulattri and A. indica against S. frugiperda has not been reported yet.

This study tested botanical insecticides A. indica and C. soulattri and their mixtures against S. frugiperda. The mixture of A. indica and C. soulattri from the results of RSM optimization is expected to be an alternative for environmentally friendly control of S. fruiperda in maize plants.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Test insect and botanical insecticide

Spodoptera frugiperda as an insect test was from the Laboratory of Pesticide and Environment Toxicology (Department of Plant Pest and Diseases, Universitas Padjadjaran, West Java, Indonesia) and reared with baby maize (pesticide-free) for larvae and 10% honey solution for adults. Environment conditions for rearing and experiment were conducted at a temperature of 27–32°C and humidity of 65–80%. Leave maize plant (Zea mays; a variety of Talenta) was used for the experiment as an insect fed for 48 h after application and replaced with baby maize until S. frugiperda became pupa.

Azadirachta indica seed (obtained from Situbondo, East Java Province, Indonesia) was pressed using a seed press machine (MKS-J05) and oil-filtered with filter paper (Whatman no. 41). C. soulattri sap (obtained from Teluk Melano District, Ketapang Regency, West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia) is cleaned from dirt with acetone, and then the solvent is removed by evaporation in Laboratory of Pesticide (Department of Agrotechnology, Universitas Tanjungpura, West Kalimantan, Indonesia). The oil and sap are put in bottles and stored at −4°C.

2.2 Experiment

2.2.1 Determination of the ratio of the insecticide mixture

A. indica and C. soulattri materials were tested using the RSM with central composite design (CCD) to obtain the optimum response. The RSM-CCD design was created using Minitab 20 software. The RSM design shows the ratio between the A. indica and C. soulattri materials. From the modeling, 13 experimental units were obtained with different ratios of each A. indica and C. soulattri material in each mixture tested (the test design is presented in Table 1). All treatments were carried out at a concentration of 0.5%. Bioassay was conducted using the residue method on the surface of the feed leaves by Widayani et al. [17]. Maize leaves (4 cm × 4 cm in size) are treated with insecticide according to treatment and concentration. Each leaf surface was smeared with 100 μl of test insecticide solution with a microsyringe. The leaves are then air-dried, and two leaves are given to the second instar larvae, S. frugiperda, in a Petri dish (9 cm in diameter) lined with tissue. The Petri dishes were stored on a table in the laboratory (temperature of 27–32°C and humidity of 65–80%). After 2 days of treatment, each live larva was placed in a plastic glass (50 ml) individually. The observation was made by counting the number of dead larvae and the feed weight consumed.

Mixed insecticide test design of A. indica and C. soulattri

| No. | A. indica | C. soulattri |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.20000 | 0.60000 |

| 2 | 2.00000 | 0.20000 |

| 3 | 1.20000 | 1.16569 |

| 4 | 1.20000 | 0.03431 |

| 5 | 1.20000 | 0.60000 |

| 6 | 2.33137 | 0.60000 |

| 7 | 2.00000 | 1.00000 |

| 8 | 1.20000 | 0.60000 |

| 9 | 1.20000 | 0.60000 |

| 10 | 0.06863 | 0.60000 |

| 11 | 0.40000 | 1.00000 |

| 12 | 1.20000 | 0.60000 |

| 13 | 0.40000 | 0.20000 |

Note: The comparative values of the lower and upper limits are as follows: A. indica: 0.4–2; C. soulattri: 0.2–1.

The data obtained were then processed using Minitab-20 to obtain an equation showing the relationship between the influence of research variables on the desired response. Then, the data were processed using ANOVA, and the relationship between responses was viewed using a contour plot to obtain the most optimum comparison. RSM verification of observation variables used a model verification test under optimum conditions with three repetitions. The optimization results were then compared with the control.

2.2.2 Botanical insecticide test

The optimization results obtained in the RSM test were then used as a mixture test insecticide. Then, the single and mixture extract tests were carried out again using the residue method on the surface of the feed leaves, as explained in the comparison test of the mixture insecticide. The test concentration used was from preliminary tests, which caused the range of 0% mortality < × < 100% insect test. The research used a randomized block design with five concentration ranges and controls, or six treatments repeated four times.

Observation parameters in the study of determining the toxicity of single and mixed insecticides include the mortality of test insect equation (1), development time, weight of feed consumption equation (2), and pupa weight.

The observation of larvae development time started 2 days after treatment (from larva instar II) until instar VI larvae at a 24-h observation interval. The time for the larvae to instars III, IV, V, and VI was recorded.

Feed consumption weight is calculated based on weight loss in the leaves used as feed. As a correction factor, the calculation uses dry and wet weights based on the average test results of five initial feed leaf sample weights. Dry weight is obtained by baking the feed leaves at 90°C for 48 h. Furthermore, the weight data are used to calculate the proportion of dry weight and obtain the initial dry weight data. Forty-eight hours after the treatment feed is given, the leaves are oven-baked at 90°C for 48 h and weighed as the final dry weight. Feed consumption weight is calculated based on equation (2):

The pupae’s weight was observed using an analytical scale. The data obtained from observation were analyzed using the variance analysis. If the results were significant, the data were analyzed using the Duncan test using the SPSS 26 program. The probit was analyzed using the Polo Plus program 1.1.

The insecticide mixture activity is analyzed using different joint action models by calculating the combination index (CI) at the LC50 and LC95 levels [32] in equation (3):

Here,

The categories of mixed activity properties:

CI < 0.5: strong synergies,

CI 0.5–0.77: weak synergies,

CI > 0.77–1.43: additive,

CI > 1.43: antagonistic.

3 Results

3.1 Single toxicity of A. indica and C. soulattri

The test results showed that C. soulattri sap had a rapid mortality effect on the test insects. The mortality of test insects occurred at the observation’s beginning (2–4 DAT). The probit regression analysis of C. soulattri on the mortality showed that the LC50 and LC95 values were 0.537 and 3.481% (Table 2). The results of the A. indica insecticide test showed that the mortality of the test insects occurred from the beginning of instar II until the larvae reached instar VI. The LC50 and LC95 values at the end of the observation or from S. frugiperda larva instars II–VI were 0.099 and 0.420%, respectively (Table 3).

Probit regression parameters of the relationship between C. soulattri sap concentration and S. frugiperda mortality

| Observation time | a ± SE | b ± SE | LC50 | CL95 | LC95 | CL95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 DAT | 0.471 ± 0.135 | 1.982 ± 0.233 | 0.579 | 0.287–1.413 | 3.910 | 1.544–78.586 |

| 4 DAT | 0.547 ± 0.138 | 2.026 ± 0.235 | 0.537 | 0.297–1.078 | 3.481 | 1.537–30.272 |

| 8 DAT | 0.547 ± 0.138 | 2.026 ± 0.235 | 0.537 | 0.297–1.078 | 3.481 | 1.537–30.272 |

| 16 DAT | 0.547 ± 0.138 | 2.026 ± 0.235 | 0.537 | 0.297–1.078 | 3.481 | 1.537–30.272 |

a: intercept; b: slope; SE: standard error; LC: lethal concentration (%); CL: confidence level; DAT: day after treatment.

Probit regression parameters of the relationship between A. indica concentration and S. frugiperda mortality

| Instar time | a ± SE | b ± SE | LC50 | CL95 | LC95 | CL95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II–III | −0.397 ± 0.284 | 1.258 ± 0.393 | 2.068 | 0.828−73.724 | 42.017 | 5.593−∞ |

| II–IV | 1.619 ± 0.138 | 2.052 ± 0.297 | 0.162 | 0.110−0.243 | 1.029 | 0.530−5.632 |

| II–V | 2.610 ± 0.326 | 2.735 ± 0.348 | 0.111 | 0.091−0.132 | 0.444 | 0.331−0.699 |

| II–VI | 2.630 ± 0.331 | 2.617 ± 0.348 | 0.099 | 0.080−0.119 | 0.420 | 0.312−0.676 |

a: intercept; b: slope;.

SE: standard error; LC: lethal concentration (%); CL: confidence level.

A single C. soulattri sap treatment decreased feed consumption or inhibited feed consumption by 92.67% (Table 4), prolonged larval development time from instars II–VI to 13 days or 1.12 days longer than the control (Table 5) but did not significantly decrease pupal weight (Table 6). These results indicate that in addition to causing the mortality of test insects, C. soulattri insecticides also disrupt the biological activity of pests.

Effect of C. soulattri sap treatment on the weight of S. frugiperda feed consumption

| Treatment | Consumption weight (mg) X ± SE (%) | Inhibition percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| C. soulattri (2.5%) | 1.563 ± 0.0718a | 92.67 |

| C. soulattri (0.94%) | 2.871 ± 0.3436a | 86.53 |

| C. soulattri (0.35%) | 4.490 ± 0.3169b | 78.93 |

| C. soulattri (0.13%) | 6.153 ± 0.2726b | 71.12 |

| C. soulattri (0.05%) | 7.753 ± 0.1537c | 63.61 |

| Control | 21.307 ± 0.3316d | 0.00 |

Values followed by the same letter indicate no significant difference according to Duncan’s test at the 5% level. X: mean; SE: standard error.

Effect of C. soulattri sap treatment on the development time of S. frugiperda larvae

| Treatment | X ± SE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Instars II–II | N | Instars II–IV | N | Instars II–V | N | Instars II–VI | |

| C. soulattri (2.5%) | 1 | 4 ± − | 1 | 7.00 ± − | 1 | 10.00 ± − | 1 | 13.00 ± − |

| C. soulattri (0.94%) | 17 | 3.29 ± 0.111 | 15 | 6.13 ± 0.088 | 15 | 9.27 ± 0.114 | 15 | 12.40 ± 0.126 |

| C. soulattri (0.35%) | 28 | 3.46 ± 0.094 | 28 | 6.21 ± 0.078 | 28 | 9.36 ± 0.091 | 28 | 12.39 ± 0.105 |

| C. soulattri (0.13%) | 36 | 3.11 ± 0.094 | 36 | 5.86 ± 0.080 | 36 | 9.28 ± 0.075 | 36 | 12.53 ± 0.083 |

| C. soulattri (0.05%) | 38 | 3.42 ± 0.109 | 38 | 5.66 ± 0.100 | 38 | 9.37 ± 0.078 | 38 | 12.32 ± 0.075 |

| Control | 40 | 2.45±0.100 | 40 | 5.48±0.079 | 40 | 8.75 ± 0.116 | 40 | 11.88 ± 0.052 |

X: mean; SE: standard error; and N: number of larvae.

Effect of C. soulattri sap treatment on S. frugiperda pupae weight

| Treatment | n | Pupae weight X ± SE (g) |

|---|---|---|

| C. soulattri (2.5%) | 1 | 0.2102 ± 0.0000 |

| C. soulattri (0.94%) | 15 | 0.1934 ± 0.0041 |

| C. soulattri (0.35%) | 26 | 0.1885 ± 0.0045 |

| C. soulattri (0.13%) | 35 | 0.1871 ± 0.0051 |

| C. soulattri (0.05%) | 37 | 0.1861 ± 0.0032 |

| Control | 40 | 0.2111 ± 0.0018 |

X: mean; SE: standard error; and N: number of pupae.

3.2 Mix ratio optimization using RSM

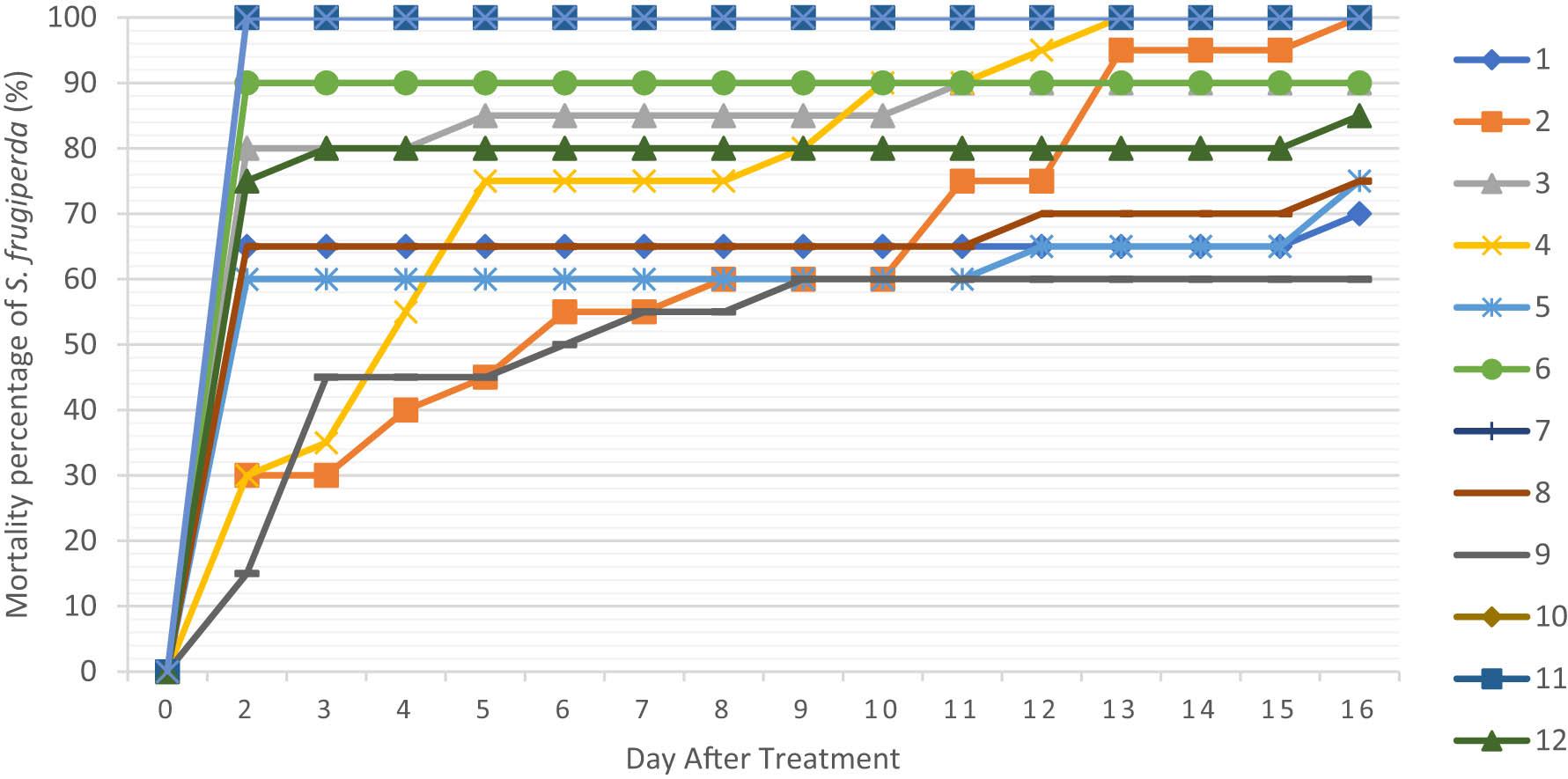

This study used the RSM factor and CCD. For one numerical factor, CCD has five levels (−α, −1, 0, +1, +α). Based on 13 treatments tested from the 2-factor RSM-CCD design (Table 7), the observation parameters of the mortality of test insects and the weight of feed consumption were obtained. Test insects’ mortality was observed for optimization analysis on the 7th day after treatment. This is based on analyzing the most visible differences in response compared to the observation day before or after the 7th day (Figure 1). At the beginning of the observation, an increase in the mortality of test insects was still seen. In contrast, in the observation, after 7 DAT, several treatments showed 100% mortality, so the data were not used for RSM analysis.

Results of RSM test of a mixture of A. indica and C. soulattri at various comparison ratios

| Treatment | Mortality percentage on 7 DAT (%) | Weight larva consumption (mg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | A. indica | C. soulattri | ||

| 1 | 1.2000 | 0.6000 | 65 | 3.341 |

| 2 | 2.0000 | 0.2000 | 55 | 0.531 |

| 3 | 1.2000 | 1.1657 | 85 | 0.906 |

| 4 | 1.2000 | 0.0343 | 75 | 4.075 |

| 5 | 1.2000 | 0.6000 | 60 | 1.678 |

| 6 | 2.3314 | 0.6000 | 90 | 9.388 |

| 7 | 2.0000 | 1.0000 | 100 | 1.106 |

| 8 | 1.2000 | 0.6000 | 65 | 8.997 |

| 9 | 1.2000 | 0.6000 | 55 | 4.941 |

| 10 | 0.0686 | 0.6000 | 100 | 6.819 |

| 11 | 0.4000 | 1.0000 | 100 | 7.653 |

| 12 | 1.2000 | 0.6000 | 80 | 4.731 |

| 13 | 0.4000 | 0.2000 | 100 | 2.028 |

Mortality graph of S. frugiperda in the mixed RSM test of A. indica and C. soulattri.

Based on the research, test insects’ mortality against various comparisons of A. indica and C. soulattri were obtained (Table 8). The analysis showed that equation (4) can be used to predict the mortality response of test insects. In addition, the results of the ANOVA showed that single A. indica and C. soulattri did not significantly affect the mortality of test insects, with a P value > 0.05. As for the interaction between A. indica * A. indica and A. indica * C. soulattri, it showed a significant effect where P < 0.05. The results of the ANOVA showed that the P value of the lack-of-fit test was 0.508, which was greater than the degree of significance of 0.05, which means that the model formed was acceptable. The results of the contour plot analysis also showed that the number of comparisons of A. indica was 0.5 and the number of C. soulattri was between 0.2 and 0.4, or the number of comparisons of A. indica was less than < 0.5, and the number of C. soulattri was greater than 1 to obtain the optimum response of mortality of test insects (Figure 2).

Results of ANOVA of the RSM mixture of A. indica and C. soulattri based on the mortality of S. frugiperda

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 5 | 3251.1 | 650.23 | 7.70 | 0.009 |

| Linear | 2 | 874.4 | 437.22 | 5.18 | 0.042 |

| A. indica | 1 | 437.2 | 437.22 | 5.18 | 0.057 |

| C. soulattri | 1 | 437.2 | 437.22 | 5.18 | 0.057 |

| Square | 2 | 1870.4 | 935.22 | 11.07 | 0.007 |

| A. indica*A. indica | 1 | 1631.1 | 1631.11 | 19.31 | 0.003 |

| C. soulattri*C. soulattri | 1 | 424.6 | 424.59 | 5.03 | 0.060 |

| 2-Way interaction | 1 | 506.3 | 506.25 | 5.99 | 0.044 |

| A. indica*C. soulattri | 1 | 506.3 | 506.25 | 5.99 | 0.044 |

| Error | 7 | 591.2 | 84.45 | ||

| Lack-of-fit | 3 | 241.2 | 80.39 | 0.92 | 0.508 |

| Pure error | 4 | 350.0 | 87.50 | ||

| Total | 12 | 3842.3 |

Contour plot between A. indica and C. soulattri on the mortality of S. frugiperda.

Consumption weight is another parameter observed to determine the level of plant damage after the test insecticide treatment. The lower the consumption weight, the lower the possibility of plant damage due to pest attacks. In this study, the values of feed consumption weight for various comparisons of A. indica and C. soulattri, equation (5), were obtained, which showed the relationship between the mixture of A. indica and C. soulattri and the response of feed consumption weight. The results of the ANOVA test showed that the amount of the A. indica and C. soulattri mixture did not significantly affect the feed consumption weight because the P value of both parameters was >0.05%. However, the results of the ANOVA test showed that the lack-of-fit value was 0.261, which was greater than the significance level of 0.05, which means that the model formed was acceptable (Table 9). The response from the equation obtained can be plotted with a contour plot to see the RSM shape of the experimental points more clearly. From these results, it can be predicted that the optimum concentration of the ratio of A. indica and C. soulattri to obtain a feed consumption weight of less than 1.5 mg, then the ratio of A. indica is 0.5–1.5 and the ratio of C. soulattri is less than 0.2 (Figure 3).

Results of variance analysis of RSM A. indica and C. soulattri based on weight consumption

| Source | DF | Adj SS | Adj MS | F-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 5 | 42.076 | 8.4152 | 0.81 | 0.579 |

| Linear | 2 | 2.801 | 1.4007 | 0.13 | 0.876 |

| A. indica | 1 | 2.432 | 2.4321 | 0.23 | 0.644 |

| C. soulattri | 1 | 0.369 | 0.3692 | 0.04 | 0.856 |

| Square | 2 | 32.899 | 16.4494 | 1.58 | 0.272 |

| A. indica*A. indica | 1 | 7.905 | 7.9053 | 0.76 | 0.413 |

| C. soulattri*C. soulattri | 1 | 21.067 | 21.0672 | 2.02 | 0.198 |

| 2-Way interaction | 1 | 6.376 | 6.3756 | 0.61 | 0.460 |

| A. indica*C. soulattri | 1 | 6.376 | 6.3756 | 0.61 | 0.460 |

| Error | 7 | 72.972 | 10.4246 | ||

| Lack-of-fit | 3 | 43.478 | 14.4926 | 1.97 | 0.261 |

| Pure error | 4 | 29.495 | 7.3737 | ||

| Total | 12 | 115.048 |

Contour plot between A. indica and C. soulattri on weight consumption of S. frugiperda.

The next step in RSM is ratio optimization. Optimization is carried out to obtain the optimal value of the model. In optimizing the mortality of test insects and consumption weight, the optimized two responses are analyzed, namely the maximum mortality condition of test insects and the minimum consumption weight. Based on the RSM optimization to obtain the highest mortality of 100% and a minimum weight of 0.2802 mg, the number of comparisons of C. soulattri is 1.1657 and A. indica is 2.3314 (Figure 4). The validation results of the optimization comparison show that the mortality of test insects at 7 DAT is 95%, and the consumption weight is 1.49 mg (Table 10). These results indicate that the results of the mortality of test insects and consumption weight are close to the optimization results of RSM.

Optimization of A. indica and C. soulattri mixture.

Results of insecticide mixture verification based on optimization results

| No. | Insecticide ingredient | Ratio | Mortality from prediction (%) | Mortality from validation (%) (X ± SE) | Weight consumption from prediction (mg) | Weight consumption from validation (mg) (X ± SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A. indica | C. soulattri | 2.0800:1.1657 | 100 | 95 ± 0.250 | 0.2802 | 1.493 ± 0.634 |

| 2 | Control | 0 ± 0.000 | 23.274 ± 1.774 | ||||

3.2.1 Insecticide mixture of A. indica and C. soulattri

The mortality of test insects in the A. indica and C. soulattri insecticide mixture (ratio 2.0800:1.1657) caused an increase in mortality from 2 to 12 DAT, and there was no increase in mortality after 13 DAT at the highest test concentration. At lower test concentrations, the mortality of test insects occurred at 2–7 DAT, and there was no significant increase in mortality after that (Figure 5). The results of the probit analysis showed that the LC50 and LC95 values at 12–16 DAT were 0.030 and 0.224%, respectively (Table 11). The LC value of the mixture of A. indica and C. soulattri insecticides (2.0800:1.1657) was lower than that of every single insecticide. Based on the calculation of the value of the mixture properties, at the beginning of the observation of 2–8 DAT, the mixture of insecticides had strong synergies in LC50 and LC95. At 12–16 DAT, insecticides have strong synergies at LC50 and weak synergies at LC95. This may be because, at the beginning of the observation, the mortality of the test insects was faster due to the role of C. soulattri, while at the end of the observation, the mortality of the test insects was likely only influenced by A. indica (Table 12).

Mortality graph of S. frugiperda in the mixed treatment of A. indica and C. soulattri.

Probit regression parameters of the relationship between C. soulattri sap and A. indica oil mixture concentration against S. frugiperda mortality

| Time observation | a ± SE | b ± SE | LC50 | CL95 | LC95 | CL95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 DAT | 1.641 ± 0.276 | 1.485 ± 0.189 | 0.079 | 0.045–0.178 | 1.006 | 0.351–12.268 |

| 4 DAT | 1.926 ± 0.288 | 1.601 ± 0.193 | 0.063 | 0.031–0.183 | 0.667 | 0.214–22.879 |

| 8 DAT | 2.498 ± 0.340 | 1.688 ± 0.209 | 0.033 | 0.16–0.078 | 0.313 | 0.114–7.871 |

| 12 DAT | 2.866 ± 0.386 | 1.879 ± 0.233 | 0.030 | 0.016–0.066 | 0.224 | 0.089–4.075 |

| 16 DAT | 2.866 ± 0.386 | 1.879 ± 0.233 | 0.030 | 0.016–0.066 | 0.224 | 0.089–4.075 |

a: intercept;b: slope; SE: standard error; LC: lethal concentration (%); CL: confidence level; DAT: day after treatment.

Results of the analysis of mixed insecticidal properties

| Treatment | LC50 and LC95 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 DAT (II–III) | 8 DAT (II–IV) | 12 DAT (II–V) | 16 DAT (II–VI) | |||||

| LC50 | LC95 | LC50 | LC95 | LC50 | LC95 | LC50 | LC95 | |

| A | 2.068 | 42.017 | 0.162 | 1.029 | 0.111 | 0.444 | 0.099 | 0.420 |

| C | 0.579 | 3.910 | 0.537 | 3.481 | 0.537 | 3.481 | 0.537 | 3.481 |

| AC | 0.079 | 1.006 | 0.033 | 0.313 | 0.030 | 0.224 | 0.030 | 0.224 |

| Combination index value | ||||||||

| Treatment | 2 DAT (II–III) | 8 DAT (II–IV) | 12 DAT (II–V) | 16 DAT (II–VI) | ||||

| LC50 | LC95 | LC50 | LC95 | LC50 | LC95 | LC50 | LC95 | |

| AC | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.63 |

| Combination index value | ||||||||

| Treatment | 2 DAT (II–III) | 8 DAT (II–IV) | 12 DAT (II–V) | 16 DAT (II–VI) | ||||

| LC50 | LC95 | LC50 | LC95 | LC50 | LC95 | LC50 | LC95 | |

| AC | Strong synergies | Strong synergies | Strong synergies | Strong synergies | Strong synergies | Weak synergies | Strong synergies | Weak synergies |

A: A. indica; C: C. soulatttri; and AC: A. indica + C. soulattri.

The mixture of A. indica and C. soulattri insecticides also inhibited feed consumption weight by up to 93.02% at a concentration of 0.3%. At lower concentrations (0.0015–0.080%), the inhibition of feed consumption was 46.05–91.97% (Table 13). Other observation parameters showed that the treatment of mixed insecticides had an effect by reducing the weight of S. frugiperda pupae (Table 14) and extending the development time of larvae from instar II to instar VI (Table 15). It is shown that the mixture of A. indica and C. soulattri may cause physiological disturbances in larvae’s growth and metabolic processes.

Effect of the A. indica and C. soulattri mixture on feed consumption of S. frugiperda

| Treatment | Weight consumption (mg) ± SE | Inhibition (%) |

|---|---|---|

| AC 0.3% | 1.979 ± 0.6784a | 93.02 |

| AC 0.080% | 2.279 ± 0.8577a | 91.97 |

| AC 0.021% | 7.293 ± 1.0210ab | 74.29 |

| AC 0.0056% | 9.493 ± 2.4353b | 66.53 |

| AC 0.0015% | 15.301 ± 1.0495c | 46.05 |

| Control | 28.363 ± 1.8126d | — |

Values followed by the same letter indicate no significant difference according to Duncan’s test at a 5% level. X: mean; SE: standard error; and AC: A. indica + C. soulattri.

Effect of the A. indica and C. soulattri mixture on the weight of S. frugiperda pupae

| Treatment | n | Mean of pupae weight (g) ± SE |

|---|---|---|

| AC 0.3% | 1 | 0.2073 ± 0.00000 |

| AC 0.080% | 10 | 0.2113 ± 0.00576 |

| AC 0.021% | 21 | 0.2166 ± 0.00465 |

| AC 0.0056% | 30 | 0.2168 ± 0.00538 |

| AC 0.0015% | 37 | 0.2174 ± 0.00538 |

| Control | 40 | 0.2177 ± 0.00249 |

X: mean; n: number of pupae; SE: standard error; and AC: A. indica + C. soulattri.

Effect of the A. indica and C. soulattri mixture on the development of S. frugiperda larvae

| Treatment | Mean duration of larval development ± SE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Instars II–II | N | Instars II–IV | N | Instars II–V | N | Instars II–VI | |

| AC 0.3% | 9 | 3.56 ± 0.166 | 8 | 7.75 ± 0.153 | 3 | 10.67 ± 0.544 | 1 | 14.00 ± 0.000 |

| AC 0.080% | 18 | 2.83 ± 0.142 | 13 | 6.38 ± 0.135 | 10 | 8.70 ± 0.202 | 10 | 11.80 ± 0.237 |

| AC 0.021% | 31 | 2.48 ± 0.111 | 24 | 5.75 ± 0.159 | 21 | 8.62 ± 0.142 | 21 | 11.19 ± 0.209 |

| AC 0.0056% | 35 | 2.63 ± 0.082 | 31 | 5.61 ± 0.118 | 31 | 8.35 ± 0.086 | 30 | 10.93 ± 0.176 |

| AC 0.0015% | 39 | 2.49 ± 0.080 | 37 | 5.11 ± 0.113 | 37 | 7.62 ± 0.080 | 37 | 10.86 ± 0.122 |

| Control | 40 | 2.18 ± 0.060 | 40 | 4.55 ± 0.079 | 40 | 6.90 ± 0.131 | 40 | 10.43 ± 0.078 |

n: number of larvae; SE: standard error; and AC: A. indica + C. soulattri.

4 Discussion

Botanical insecticides A. indica and C. soulattri caused the mortality of S. frugiperda with LC50 and LC95 values higher than the mixture. This shows that mixing both insecticides can increase toxicity. Mixing insecticides A. indica and C. soulattri can reduce the test concentration and reduce the need for the required materials. This also shows that the RSM optimization method effectively determines the ratio optimization in insecticide mixtures. In this study, optimization uses two responses: the mortality of test insects and the weight of feed consumption. Each response provides a mathematical equation to predict the response that will be produced. The optimization ratio in this study was 2.0800:1.1657 between A. indica and C. soulattri.

Determination of the ratio between insecticide ingredients using RSM is still rarely reported. In this study, we confirm that using RSM makes it easier to design research to determine the effects of mixing on mortality and feed consumption parameters. In conventional ratio determination, such as determining the properties of mixed insecticides at various ratios, all single and mixed insecticides must have known LC or toxicity values to determine the properties of the mixed insecticide [33,34]. In RSM, the optimum ratio can be determined using one experimental unit. As stated by Sai et al. [35], RSM can be used for experimental and numerical response estimates.

The mortality time of test insects also differed in the single treatment of A. indica and C. soulattri and their mixtures. The mortality of the test insects in the C. soulattri treatment was faster or occurred at the beginning of the observation. Meanwhile, in the A. indica treatment, the mortality of the test insects occurred from the beginning to the end of the observation. Syahputra et al. [14] reported that the way C. soulattri works on the active fraction is faster. A. indica causes inhibition of cuticle turnover due to disruption of the endocrine system, prevents ecdysis, apolysis, cuticle secretion, and inhibition of the eclosion process and disruption of the central nervous system [6,36,37]. In the mixture of A. indica and C. soulattri, the mortality of the test insects was high at the beginning of observation (2–5 DAT), but there was still an increase in mortality in subsequent observations. C. soulattri is reported to have neurotoxin properties, so it provides a response at the beginning of observation, while A. indica has hormonal toxins that cause developmental disorders, and mortality of test insects can occur until the end of larval development. This was confirmed by Widayani et al. [17], who showed that in a mixture of C. soulattri and S. indicum (4:1) and a mixture of C. soulattri and P. aduncum (1:2), the mortality of test insects occurred at the beginning of the observation period (2–4 DAT). This also shows that the type of insecticide mixture will affect the mechanism of action of the mixture, including the time of mortality of the test insects.

A synergistic effect is obtained when two materials are mixed to produce a combination index value of ≤0.5. Synergism will be obtained at the right ratio between materials, so determining the ratio between mixed materials is important. In this study, the results obtained below the optimum ratio of the RSM test of the A. indica and C. soulattri insecticide mixture can increase the toxicity of the insecticide mixture and have strong synergistic properties at LC50 based on the combination index. This shows that each mode of action of A. indica and C. soulattri can work together so that the mixed effect is better than either alone. The phenomenon of the mechanism of action of the combination of two active ingredients, one of which increases penetration while the other inhibits the detoxification mechanism (synergistic component). Another phenomenon can be that both components are toxic, whose targets can be the same or different. In this study, the two ingredients used were not pure components but were still in the form of extracts, both of which have adverse effects on insects. Azadirachtin, which is an active compound from the A. indica plant, can interfere with insect development/hormones, although it has also been reported to interfere with the reproductive system. Research on azadirachtin, especially in their physiological and biological activities and their applications in agriculture, has brought a lot of progress, but the exact mechanism of action, especially at the molecular level, is not fully understood [38,39]. On the other hand, based on the observations of symptoms of C. soulattri extract poisoning in insects, there were no symptoms of hormonal disorders [40]. Efforts to find active components from this plant extract using chromatography techniques have been carried out by Syahputra (2004) in his dissertation research. After separating the materials into fractions, the results obtained were active fractions that crystallized (indicating relatively pure components), indicating that the insecticidal toxicity of the active fraction decreased, and finally, the search for active compounds was stopped. This indicates that the insecticidal activity shown by the C. soulattri extract is likely to work synergistically.

Two or more mixed ingredients will cause synergistic and antagonistic effects. The mixture of two products can be synergistic if the effect shows more of their 1 + 1 effect or increases their effectiveness. Then, antagonism reduces the effectiveness of two compounds or the effect less than the expected sum of two individual effects [41,42]. The research results of Levchenko and Silivanova [43] show that interaction patterns (synergistic or antagonistic) in the insecticide mixtures can depend on both the combination of insecticides and their ratio. A synergistic interaction was considered to occur when the combination of the sublethal doses of two compounds resulted in a significantly higher lethality relative to the individual effects of each other [44]. The addition of synergistic ingredients can also increase the toxicity of insecticides. Synergies ingredients are non-toxic ingredients, and the mode of action is to block the metabolic systems (like detoxification of insecticides) that would otherwise break down insecticide molecules [45]. In this study, a mixture of two insecticide ingredients was used against S. frugiperda. Each ingredient has a different mode of action and is expected to work together to increase the toxicity and effectiveness of the mixture.

Insecticide treatment of C. soulattri and its mixture also affects feed consumption, larval development time, and pupal weight. Ethanol extract from C. soulattri bark can suppress feed consumption, extend larval time, and reduce the pupal weight of S. frugiperda [17]. Physiological disorders in test larvae can be caused by the inhibition of invertase and protease enzyme activity of C. pavonana and provide the effect of refusing to eat and affecting digestion and absorption of food [46]. This affects the growth and development process of test insects. A. indica is reported to contain limonoids, quadinoids, meliantriol, and other active ingredients that function as repellents and feeding inhibitors and reduce the number of circulating cells and the activity of lysozyme-like enzymes [47,48,49]. These effects are combined with the work of C. soulattri, which results in cytotoxic effects [50]. Specific reports regarding the active ingredients of C. soulattri insecticide against insect pests are still limited. Both botanical insecticides have also been reported to suppress acetylcholine esterase activity [51,52]. This shows that the synergistic effect is obtained due to the existence of a mode of action or influence that both supports and other influences that increase the activity of the mixed insecticide.

5 Conclusions

The test results showed that the LC50 and LC95 values of single insecticides A. indica and C. soulattri were higher than those of the mixture at 2.0800:1.1657. In this experiment, RSM optimization showed that the estimated optimum response in determining the mixture ratio could increase the insecticide activity. The mixture of insecticides A. indica and C. soulattri had strong synergy at LC50 and weak synergy at LC95. The mixture of insecticides A. indica and C. soulattri also affected feed consumption, larval development time, and pupal weight of S. frugiperda. The mixture of insecticides A. indica and C. soulattri can be used to control S. frugiperda pests in maize plants in an environmentally friendly way. The obtained results indicate that mixed insecticides can increase toxicity and effects on tested insects. Determination of the mixture ratio can use RSM to save research time and energy and predict the response of the treatment used.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by the DIPA Scheme Universitas Tanjungpura in 2022 (No. 2788/UN22.3/PT.01.03/2022) and the Internal Grant Universitas Padjadjaran with the Academic Leadership Grant scheme in 2023/2024 (No. 1430/UN6.3.1/PT.00/2024).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. E.S.; conceptual, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquation, investigation, methodology, resources, writing – review & editing, validation, supervision, and project administration. D.D.; conceptual, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquation, investigation, methodology, resources, writing – review & editing, validation, supervision. Sudarjat; investigation, project administration, supervision, validation. Y.H.; data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, writing – review & editing, supervision. L.T.P.; data curation, formal analysis, investigation, project administration, resources, writing – original draft, supervision. V.K.D.; data curation, formal analysis, investigation, project administration. S.I.; data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, software writing – review & editing, validation and N.S.W.; data curation, investigation, project administration, writing – original draft.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets are stored in the repository of Universitas Padjadjaran (https://repository.unpad.ac.id/home) and included in this published article.

References

[1] Supriyono S, Hidayah N, Wijayanti KS, Sujak S, Sunarto DA, Yulianti T, et al. Research status of botanical insecticide in Indonesia and its commercial constraints. BIO Web Conf EDP Sci. 2024;91:01019.10.1051/bioconf/20249101019Search in Google Scholar

[2] Dono D, Hidayat Y, Suganda T, Hidayat S, Widayani NS. The toxicity of neem (Azadirachta indica), citronella (Cymbopogon nardus), castor (Ricinus communis), and clove (Syzygium aromaticum) oil against Spodoptera frugiperda. Cropsaver. 2020;3(1):22–30.10.24198/cropsaver.v3i1.28324Search in Google Scholar

[3] Tulashie SK, Adjei F, Abraham J, Addo E. Potential of neem extracts as natural insecticide against fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda (J. E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Case Stud Chem Environ Eng. 2021;4:100130.10.1016/j.cscee.2021.100130Search in Google Scholar

[4] Fauzi S, Prastowo S. Repellent effect of the pandanus (Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb.) and neem (Azadirachta indica) against rice weevil Sitophilus oryzae L. (Coleoptera, Curculionidae). Entomol Ornithol Herpetol. 2022;11(2):276.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Wang H, Lai D, Yuan M, Xu H. Growth inhibition and differences in protein profiles in azadirachtin-treated Drosophila melanogaster larvae. Electrophoresis 2014;35(8):1122–29.10.1002/elps.201300318Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Qiao J, Zou X, Lai D, Yan Y, Wang Q, Li W, et al. Azadirachtin blocks the calcium channel and modulates the cholinergic miniature synaptic current in the central nervous system of Drosophila. Pest Manag Sci. 2014;70(7):1041–7.10.1002/ps.3644Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Wulansari R, Hidayat Y, Dono D. Aktivitas insektisida campuran minyak mimba (Azadirachta indica) dan minyak jarak kepyar (Ricinus communis) terhadap Spodoptera frugiperda. Agrikultura. 2021;32(3):207–18.10.24198/agrikultura.v32i3.35174Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ramadhan RAM, Widayani NS, Puspasari LT, Hidayat Y, Dono D. Laboratory evaluation of neem formulation bioactivity against Crocidolomia pavonana F. larvae. Cropsaver. 2018;1(1):37–41.10.24198/cropsaver.v1i1.20334Search in Google Scholar

[9] Isman MB. Bridging the gap: moving botanical insecticides from the laboratory to the farm. Ind Crops Prod. 2017;110:10–4.10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.07.012Search in Google Scholar

[10] Kilani-Morakchi S, Morakchi-Goudjil H, Sifi K. Azadirachtin-based insecticide: overview, risk assessments, and future directions. Front Agron. 2021;3:676208.10.3389/fagro.2021.676208Search in Google Scholar

[11] Michel MR, Aguilar-Zárate M, Rojas R, Martínez-Ávila GCG, Aguilar-Zárate P. The insecticidal activity of Azadirachta indica leaf extract: optimization of the microencapsulation process by complex coacervation. Plants. 2023;12(6):1318.10.3390/plants12061318Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Benuzzi M, Ladurner E. Plant protection tools in organic farming. In Handbook of pest management in organic farming. Wallingford UK: CAB international; 2018. p. 24–59.10.1079/9781780644998.0024Search in Google Scholar

[13] Syahputra E, Manuwoto S, Darusman LK, Dadang, Prijono D. Aktivitas insektisida bagian tumbuhan Calophyllum soulattri Burm.F. (Clusiaceae) terhadap larva lepidoptera. J Trop Plant Pests Dis. 2004;4(1):23–31.10.23960/j.hptt.1423-31Search in Google Scholar

[14] Syahputra E, Prijono D, Dono DD. Sediaan insektisida Calophyllum soulattri: aktivitas insektisida dan residu terhadap larva Crocidolomia pavonana dan keamanan pada tanaman. J Trop Plant Pests Dis. 2007;7(1):21–9.10.23960/j.hptt.1721-29Search in Google Scholar

[15] Mah SH, Ee GCL, Teh SS, Rahmani M, Lim YM, Go R. Phylattrin, a new cytotoxic xanthone from Calophyllum soulattri. Molecules 2012;17(7):8303–11.10.3390/molecules17078303Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Husni E, Dachriyanus D, Saputri VW. Penentuan kadar fenolat total, uji aktivitas antioksidan dan antibakteri dari ekstrak dan fraksi kulit batang bintangor (Calophyllum soulattri Burm. F). J Sains Farm Klin. 2020;7(1):92–8.10.25077/jsfk.7.1.92-98.2020Search in Google Scholar

[17] Widayani NS, Dono D, Hidayat Y, Ishmayana S, Syahputra E. Toxicity of Calophyllum soulattri, Piper aduncum, Sesamum indicum and their potential mixture for control Spodoptera frugiperda. Open Agric. 2023;8(1):1.20220213.10.1515/opag-2022-0213Search in Google Scholar

[18] Fareza MS, Choironi NA, Susilowati SS, Rini MP, Festihawa V, Fauzi ISN, et al. LC-MS/MS and cytotoxic activity analysis of extract and fraction of Calophyllum soulattri Stembark. Indones J Pharm. 2021;32(3):356–64.10.22146/ijp.1328Search in Google Scholar

[19] Lim CK, Hemaroopini S, Say YH, Jong VYM. Cytotoxic compounds from the stem bark of Calophyllum soulattri. Nat Prod Commun. 2017;12(9):1469–71.10.1177/1934578X1701200922Search in Google Scholar

[20] Ge SS, He LM, Wey HE, Ran YAN, Wyckhuys KA, Wu KM. Laboratory-based flight performance of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. J Integr Agric. 2021;20(3):707–14.10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63166-5Search in Google Scholar

[21] Wang J, Huang Y, Huang L, Dong Y, Huang W, Ma H, et al. Migration risk of fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) from North Africa to Southern Europe. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1141470.10.3389/fpls.2023.1141470Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Mukkun L, Kledden YL, Simamora AV. Detection of Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in maize field in East Flores District, East Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia. Int J Trop Drylands. 2021;5(1):20–6.10.13057/tropdrylands/t050104Search in Google Scholar

[23] Trisyono YA, Suputa S, Aryuwandari VEF, Hartaman M, Jumari J. Occurrence of heavy infestation by the fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda, a new alien invasive pest, in corn Lampung Indonesia. J Perlin Tan Indonesia. 2019;23(1):156–60.10.22146/jpti.46455Search in Google Scholar

[24] Asfiya W, Subagyo VNO, Dharmayanthi AB, Fatimah F, Rachmatiyah R. Intensitas serangan Spodoptera frugiperda J.E. Smith (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) pada pertanaman jagung di Kabupaten Garut dan Tasikmalaya, Jawa Barat. J Entomol Indones. 2020;17(3):163–7.10.5994/jei.17.3.163Search in Google Scholar

[25] Day R, Abrahams P, Bateman M, Beale T, Clottey V, Cock M, et al. Fall armyworm: impacts and implications for Africa. Outlooks Pest Manage. 2017;28(5):196–1.10.1564/v28_oct_02Search in Google Scholar

[26] Deshmukh SS, Kalleshwaraswamy CM, Prasanna BM, Sannathimmappa HG, Kavyashree BA, Sharath KN, et al. Economic analysis of pesticide expenditure for managing the invasive fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) by maize farmers in Karnataka, India. Curr Sci. 2021;121(11):1487–92.10.18520/cs/v121/i11/1487-1492Search in Google Scholar

[27] Montezano DG, Specht A, Sosa-Gómez DR, Roque-Specht VF, Sousa-Silva JC, Paula-Moraes SV., et al. Host plants of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in the Americas. Afr Entomol. 2018;26(2):286–300.10.4001/003.026.0286Search in Google Scholar

[28] Mawi M, Hanzalah M, Saad M, Syahirah Mokhtar A, Asib N. Toxicity of Azadirachta indica and Piper sarmentosum extract mixture formulations against Nilaparvata lugens (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) in paddy field. Serangga. 2022;27(3):132–42.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Anderson MJ, Whitcomb PJ. RSM simplified optimizing processes using response surface methods for design of experiments. 2nd edn. New York: CRC Press; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[30] RajeNimbalkar RU, Barge NS, Marathe RJ, Phatake YB, Deshmukh RB, Dange SS, et al. Application of response surface methodology for optimization of siderophore production. Indian J Agric Res. 2022;56(2):230–37.10.18805/IJARe.A-5663Search in Google Scholar

[31] Hazafa A, Jahan N, Zia MA, Rahman KU, Sagheer M, Naeem M. Evaluation and optimization of nanosuspensions of Chrysanthemum coronarium and Azadirachta indica using response surface methodology for pest management. Chemosphere. 2022;292:133411.10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133411Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Chou TC, Talalayi P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–5.10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Nailufar N, Prijono D. Synergistic activity of Piper aduncum fruit and Tephrosia vogelii leaf extracts against the cabbage head caterpillar, Crocidolomia pavonana J ISSAAS. 2017;23(1):102–10.Search in Google Scholar

[34] Nuryanti NSP, Budiarti L. Toxicity and compatibility of botanical insecticide from clove (Syzygium aromaticum), lime (Citrus aurantifolia) and garlic (Allium sativum) essential oil against Callasobruchus chinensis L. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 2022. p. 012036, IOP Publishing.10.1088/1755-1315/1012/1/012036Search in Google Scholar

[35] Sai DA, Nataraj K, Lakshmana RA. Response surface methodology-a statistical tool for the optimization of responses. Glob J Addict Rehabil Med. 2023;7(1):1–7.10.19080/GJARM.2023.07.555705Search in Google Scholar

[36] Sieber KP, Rembold H. The effects of azadirachtin on the endocrine control of moulting in Locusta migratoria. J Insect Physiol. 1983;29(6):523–7.10.1016/0022-1910(83)90083-5Search in Google Scholar

[37] Dorn A, Rademacher JM, Sehn E. Effects of azadirachtin on the moulting cycle, endocrine system, and ovaries in last-instar larvae of the milkweed bug, Oncopeltus fasciatus. J Insect Physiol. 1986;32(3):231–8.10.1016/0022-1910(86)90063-6Search in Google Scholar

[38] Lai D, Jin X, Wang H, Yuan M, Xu H. Gene expression profile change and growth inhibition in Drosophila larvae treated with azadirachtin. J Biotechnol. 2014;185:51–6.10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.06.014Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Dawkar VV, Barage SH, Barbole RS, Fatangare A, Grimalt S, Haldar S, et al. Azadirachtin-a from Azadirachta indica impacts multiple biological targets in cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera. ACS Omega. 2019;4(5):9531–41.10.1021/acsomega.8b03479Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Syahputra E. Bioaktivitas insektisida botani Calophyllum soulattri Burm. F. (Clusiaceae) sebagai pengendali hama alternatif, Bogor: Institut Pertanian Bogor; 2004.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Akhtar Y, Isman MB. Plant natural products for pest management: the magic of mixtures. Advanced technologies for managing insect pests. London: Springer; 2013. p. 231–47.10.1007/978-94-007-4497-4_11Search in Google Scholar

[42] Reddy DS, Chowdary NM. Botanical biopesticide combination concept—a viable option for pest management in organic farming. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2021;31(1):1–10.10.1186/s41938-021-00366-wSearch in Google Scholar

[43] Levchenko MA, Silivanova EA. Synergistic and antagonistic effects of insecticide binary mixtures against house flies (Musca domestica). Regul Mech Biosyst. 2019;10(1):75–2.10.15421/021912Search in Google Scholar

[44] Bernard BC, Philogfene BJR. Insecticide synergists: role, importance, and perspectives. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1993;38(2):199–233.10.1080/15287399309531712Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Yadav J, Ranga P, Guruwan D. Chapter - 3 role of synergists in combating insect resistance to pesticides, in book: applied entomology and zoology. Vol. 4. New Delhi: AkiNik Publications; 2018. p. 45–59.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Syahputra E, Prijono D, Dadang, Manuwoto S, Darusman LK. Respons fisiologi Crocidolomia pavonana terhadap fraksi aktif Calophyllum soulattri. Hayati. 2006;13(1):7–12.10.1016/S1978-3019(16)30372-2Search in Google Scholar

[47] Suryaningsih E, Hadisoeganda AW. Controlling important chili pests and diseases with biorational pesticides. J Hort. 2007;17(3):261–9.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Mardianingsih TL, Sukmana C, Tarigan N, Suriati S. Efektivitas insektisida nabati berbahan aktif Azadirachtin dan saponin terhadap mortalitas dan intensitas serangan Aphis gossypii Glover. Bul Littro. 2010;21(2):171–83.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Duarte JP, Redaelli LR, Silva CE, Jahnke SM. Effect of Azadirachta indica (Sapindales: Meliaceae) oil on the immune system of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) immatures. J Insect Sci. 2020;20(3):1–6.10.1093/jisesa/ieaa048Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Mah SH, Ee GCL, Teh SS. Chemistry and cytotoxic activity of essential oil from the stem bark of Calophyllum soulattri. Asian J Chem. 2013;25(15):8831–2.10.14233/ajchem.2013.15565Search in Google Scholar

[51] Ee GCL, Teh SS, Mah SH, Jamaluddin NA, Sahimi MSBM, Ahmad Z. Acetyl-cholinesterase enzyme inhibitory effect of Calophyllum species. Trop J Pharm Res. 2015;14(11):2005–8.10.4314/tjpr.v14i11.8Search in Google Scholar

[52] Sami AJ, Bilal S, Khalid M, Shakoori FR, Rehman F, Shakoori AR. Effect of crude neem (Azadirachta indica) powder and azadirachtin on the growth and acetylcholinesterase activity of Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Pakistan J Zool. 2016;48(3):881–6.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants

- Assessment of nutrition status of pineapple plants during ratoon season using diagnosis and recommendation integrated system

- Nutritional value and consumer assessment of 12 avocado crosses between cvs. Hass × Pionero

- The lacked access to beef in the low-income region: An evidence from the eastern part of Indonesia

- Comparison of milk consumption habits across two European countries: Pilot study in Portugal and France

- Antioxidant responses of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages

- Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

- Yield and vegetation index of different maize varieties and nitrogen doses under normal irrigation

- Urbanization and forecast possibilities of land use changes by 2050: New evidence in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam

- Organizational-economic efficiency of raspberry farming – case study of Kosovo

- Application of nitrogen-fixing purple non-sulfur bacteria in improving nitrogen uptake, growth, and yield of rice grown on extremely saline soil under greenhouse conditions

- Digital motivation, knowledge, and skills: Pathways to adaptive millennial farmers

- Investigation of biological characteristics of fruit development and physiological disorders of Musang King durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.)

- Enhancing rice yield and farmer welfare: Overcoming barriers to IPB 3S rice adoption in Indonesia

- Simulation model to realize soybean self-sufficiency and food security in Indonesia: A system dynamic approach

- Gender, empowerment, and rural sustainable development: A case study of crab business integration

- Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses of bacterial communities in short mackerel (Rastrelliger brachysoma) under storage conditions and inoculation of the histamine-producing bacterium

- Fostering women’s engagement in good agricultural practices within oil palm smallholdings: Evaluating the role of partnerships

- Increasing nitrogen use efficiency by reducing ammonia and nitrate losses from tomato production in Kabul, Afghanistan

- Physiological activities and yield of yacon potato are affected by soil water availability

- Vulnerability context due to COVID-19 and El Nino: Case study of poultry farming in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Wheat freshness recognition leveraging Gramian angular field and attention-augmented resnet

- Suggestions for promoting SOC storage within the carbon farming framework: Analyzing the INFOSOLO database

- Optimization of hot foam applications for thermal weed control in perennial crops and open-field vegetables

- Toxicity evaluation of metsulfuron-methyl, nicosulfuron, and methoxyfenozide as pesticides in Indonesia

- Fermentation parameters and nutritional value of silages from fodder mallow (Malva verticillata L.), white sweet clover (Melilotus albus Medik.), and their mixtures

- Five models and ten predictors for energy costs on farms in the European Union

- Effect of silvopastoral systems with integrated forest species from the Peruvian tropics on the soil chemical properties

- Transforming food systems in Semarang City, Indonesia: A short food supply chain model

- Understanding farmers’ behavior toward risk management practices and financial access: Evidence from chili farms in West Java, Indonesia

- Optimization of mixed botanical insecticides from Azadirachta indica and Calophyllum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda using response surface methodology

- Mapping socio-economic vulnerability and conflict in oil palm cultivation: A case study from West Papua, Indonesia

- Exploring rice consumption patterns and carbohydrate source diversification among the Indonesian community in Hungary

- Determinants of rice consumer lexicographic preferences in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

- Effect on growth and meat quality of weaned piglets and finishing pigs when hops (Humulus lupulus) are added to their rations

- Healthy motivations for food consumption in 16 countries

- The agriculture specialization through the lens of PESTLE analysis

- Combined application of chitosan-boron and chitosan-silicon nano-fertilizers with soybean protein hydrolysate to enhance rice growth and yield

- Stability and adaptability analyses to identify suitable high-yielding maize hybrids using PBSTAT-GE

- Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-mediated rock phosphate utilization with poultry manure enhances soil nutrient dynamics and maize growth in semi-arid soil

- Factors impacting on purchasing decision of organic food in developing countries: A systematic review

- Influence of flowering plants in maize crop on the interaction network of Tetragonula laeviceps colonies

- Bacillus subtilis 34 and water-retaining polymer reduce Meloidogyne javanica damage in tomato plants under water stress

- Vachellia tortilis leaf meal improves antioxidant activity and colour stability of broiler meat

- Evaluating the competitiveness of leading coffee-producing nations: A comparative advantage analysis across coffee product categories

- Application of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LP5 in vacuum-packaged cooked ham as a bioprotective culture

- Evaluation of tomato hybrid lines adapted to lowland

- South African commercial livestock farmers’ adaptation and coping strategies for agricultural drought

- Spatial analysis of desertification-sensitive areas in arid conditions based on modified MEDALUS approach and geospatial techniques

- Meta-analysis of the effect garlic (Allium sativum) on productive performance, egg quality, and lipid profiles in laying quails

- Optimizing carrageenan–citric acid synergy in mango gummies using response surface methodology

- The strategic role of agricultural vocational training in sustainable local food systems

- Agricultural planning grounded in regional rainfall patterns in the Colombian Orinoquia: An essential step for advancing climate-adapted and sustainable agriculture

- Perspectives of master’s graduates on organic agriculture: A Portuguese case study

- Developing a behavioral model to predict eco-friendly packaging use among millennials

- Government support during COVID-19 for vulnerable households in Central Vietnam

- Citric acid–modified coconut shell biochar mitigates saline–alkaline stress in Solanum lycopersicum L. by modulating enzyme activity in the plant and soil

- Herbal extracts: For green control of citrus Huanglongbing

- Research on the impact of insurance policies on the welfare effects of pork producers and consumers: Evidence from China

- Investigating the susceptibility and resistance barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars against the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia)

- Characterization of promising enterobacterial strains for silver nanoparticle synthesis and enhancement of product yields under optimal conditions

- Testing thawed rumen fluid to assess in vitro degradability and its link to phytochemical and fibre contents in selected herbs and spices

- Protein and iron enrichment on functional chicken sausage using plant-based natural resources

- Fruit and vegetable intake among Nigerian University students: patterns, preferences, and influencing factors

- Bioprospecting a plant growth-promoting and biocontrol bacterium isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico: Paenibacillus sp. strain TSM33

- Quantifying urban expansion and agricultural land conversion using spatial indices: evidence from the Red River Delta, Vietnam

- LEADER approach and sustainability overview in European countries

- Influence of visible light wavelengths on bioactive compounds and GABA contents in barley sprouts

- Assessing Albania’s readiness for the European Union-aligned organic agriculture expansion: a mixed-methods SWOT analysis integrating policy, market, and farmer perspectives

- Genetically modified foods’ questionable contribution to food security: exploring South African consumers’ knowledge and familiarity

- The role of global actors in the sustainability of upstream–downstream integration in the silk agribusiness

- Multidimensional sustainability assessment of smallholder dairy cattle farming systems post-foot and mouth disease outbreak in East Java, Indonesia: a Rapdairy approach

- Enhancing azoxystrobin efficacy against Pythium aphanidermatum rot using agricultural adjuvants

- Review Articles

- Reference dietary patterns in Portugal: Mediterranean diet vs Atlantic diet

- Evaluating the nutritional, therapeutic, and economic potential of Tetragonia decumbens Mill.: A promising wild leafy vegetable for bio-saline agriculture in South Africa

- A review on apple cultivation in Morocco: Current situation and future prospects

- Quercus acorns as a component of human dietary patterns

- CRISPR/Cas-based detection systems – emerging tools for plant pathology

- Short Communications

- An analysis of consumer behavior regarding green product purchases in Semarang, Indonesia: The use of SEM-PLS and the AIDA model

- Effect of NaOH concentration on production of Na-CMC derived from pineapple waste collected from local society

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants

- Assessment of nutrition status of pineapple plants during ratoon season using diagnosis and recommendation integrated system

- Nutritional value and consumer assessment of 12 avocado crosses between cvs. Hass × Pionero

- The lacked access to beef in the low-income region: An evidence from the eastern part of Indonesia

- Comparison of milk consumption habits across two European countries: Pilot study in Portugal and France

- Antioxidant responses of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages

- Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

- Yield and vegetation index of different maize varieties and nitrogen doses under normal irrigation

- Urbanization and forecast possibilities of land use changes by 2050: New evidence in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam

- Organizational-economic efficiency of raspberry farming – case study of Kosovo

- Application of nitrogen-fixing purple non-sulfur bacteria in improving nitrogen uptake, growth, and yield of rice grown on extremely saline soil under greenhouse conditions

- Digital motivation, knowledge, and skills: Pathways to adaptive millennial farmers

- Investigation of biological characteristics of fruit development and physiological disorders of Musang King durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.)

- Enhancing rice yield and farmer welfare: Overcoming barriers to IPB 3S rice adoption in Indonesia

- Simulation model to realize soybean self-sufficiency and food security in Indonesia: A system dynamic approach

- Gender, empowerment, and rural sustainable development: A case study of crab business integration

- Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses of bacterial communities in short mackerel (Rastrelliger brachysoma) under storage conditions and inoculation of the histamine-producing bacterium

- Fostering women’s engagement in good agricultural practices within oil palm smallholdings: Evaluating the role of partnerships

- Increasing nitrogen use efficiency by reducing ammonia and nitrate losses from tomato production in Kabul, Afghanistan

- Physiological activities and yield of yacon potato are affected by soil water availability

- Vulnerability context due to COVID-19 and El Nino: Case study of poultry farming in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Wheat freshness recognition leveraging Gramian angular field and attention-augmented resnet

- Suggestions for promoting SOC storage within the carbon farming framework: Analyzing the INFOSOLO database

- Optimization of hot foam applications for thermal weed control in perennial crops and open-field vegetables

- Toxicity evaluation of metsulfuron-methyl, nicosulfuron, and methoxyfenozide as pesticides in Indonesia

- Fermentation parameters and nutritional value of silages from fodder mallow (Malva verticillata L.), white sweet clover (Melilotus albus Medik.), and their mixtures

- Five models and ten predictors for energy costs on farms in the European Union

- Effect of silvopastoral systems with integrated forest species from the Peruvian tropics on the soil chemical properties

- Transforming food systems in Semarang City, Indonesia: A short food supply chain model

- Understanding farmers’ behavior toward risk management practices and financial access: Evidence from chili farms in West Java, Indonesia

- Optimization of mixed botanical insecticides from Azadirachta indica and Calophyllum soulattri against Spodoptera frugiperda using response surface methodology

- Mapping socio-economic vulnerability and conflict in oil palm cultivation: A case study from West Papua, Indonesia

- Exploring rice consumption patterns and carbohydrate source diversification among the Indonesian community in Hungary

- Determinants of rice consumer lexicographic preferences in South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia

- Effect on growth and meat quality of weaned piglets and finishing pigs when hops (Humulus lupulus) are added to their rations

- Healthy motivations for food consumption in 16 countries

- The agriculture specialization through the lens of PESTLE analysis

- Combined application of chitosan-boron and chitosan-silicon nano-fertilizers with soybean protein hydrolysate to enhance rice growth and yield

- Stability and adaptability analyses to identify suitable high-yielding maize hybrids using PBSTAT-GE

- Phosphate-solubilizing bacteria-mediated rock phosphate utilization with poultry manure enhances soil nutrient dynamics and maize growth in semi-arid soil

- Factors impacting on purchasing decision of organic food in developing countries: A systematic review

- Influence of flowering plants in maize crop on the interaction network of Tetragonula laeviceps colonies

- Bacillus subtilis 34 and water-retaining polymer reduce Meloidogyne javanica damage in tomato plants under water stress

- Vachellia tortilis leaf meal improves antioxidant activity and colour stability of broiler meat

- Evaluating the competitiveness of leading coffee-producing nations: A comparative advantage analysis across coffee product categories

- Application of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum LP5 in vacuum-packaged cooked ham as a bioprotective culture

- Evaluation of tomato hybrid lines adapted to lowland

- South African commercial livestock farmers’ adaptation and coping strategies for agricultural drought

- Spatial analysis of desertification-sensitive areas in arid conditions based on modified MEDALUS approach and geospatial techniques

- Meta-analysis of the effect garlic (Allium sativum) on productive performance, egg quality, and lipid profiles in laying quails

- Optimizing carrageenan–citric acid synergy in mango gummies using response surface methodology

- The strategic role of agricultural vocational training in sustainable local food systems

- Agricultural planning grounded in regional rainfall patterns in the Colombian Orinoquia: An essential step for advancing climate-adapted and sustainable agriculture

- Perspectives of master’s graduates on organic agriculture: A Portuguese case study

- Developing a behavioral model to predict eco-friendly packaging use among millennials

- Government support during COVID-19 for vulnerable households in Central Vietnam

- Citric acid–modified coconut shell biochar mitigates saline–alkaline stress in Solanum lycopersicum L. by modulating enzyme activity in the plant and soil

- Herbal extracts: For green control of citrus Huanglongbing

- Research on the impact of insurance policies on the welfare effects of pork producers and consumers: Evidence from China

- Investigating the susceptibility and resistance barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) cultivars against the Russian wheat aphid (Diuraphis noxia)

- Characterization of promising enterobacterial strains for silver nanoparticle synthesis and enhancement of product yields under optimal conditions

- Testing thawed rumen fluid to assess in vitro degradability and its link to phytochemical and fibre contents in selected herbs and spices

- Protein and iron enrichment on functional chicken sausage using plant-based natural resources

- Fruit and vegetable intake among Nigerian University students: patterns, preferences, and influencing factors

- Bioprospecting a plant growth-promoting and biocontrol bacterium isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico: Paenibacillus sp. strain TSM33

- Quantifying urban expansion and agricultural land conversion using spatial indices: evidence from the Red River Delta, Vietnam

- LEADER approach and sustainability overview in European countries

- Influence of visible light wavelengths on bioactive compounds and GABA contents in barley sprouts

- Assessing Albania’s readiness for the European Union-aligned organic agriculture expansion: a mixed-methods SWOT analysis integrating policy, market, and farmer perspectives

- Genetically modified foods’ questionable contribution to food security: exploring South African consumers’ knowledge and familiarity

- The role of global actors in the sustainability of upstream–downstream integration in the silk agribusiness

- Multidimensional sustainability assessment of smallholder dairy cattle farming systems post-foot and mouth disease outbreak in East Java, Indonesia: a Rapdairy approach

- Enhancing azoxystrobin efficacy against Pythium aphanidermatum rot using agricultural adjuvants

- Review Articles

- Reference dietary patterns in Portugal: Mediterranean diet vs Atlantic diet

- Evaluating the nutritional, therapeutic, and economic potential of Tetragonia decumbens Mill.: A promising wild leafy vegetable for bio-saline agriculture in South Africa

- A review on apple cultivation in Morocco: Current situation and future prospects

- Quercus acorns as a component of human dietary patterns

- CRISPR/Cas-based detection systems – emerging tools for plant pathology

- Short Communications

- An analysis of consumer behavior regarding green product purchases in Semarang, Indonesia: The use of SEM-PLS and the AIDA model

- Effect of NaOH concentration on production of Na-CMC derived from pineapple waste collected from local society