Evaluating the nutritional, therapeutic, and economic potential of Tetragonia decumbens Mill.: A promising wild leafy vegetable for bio-saline agriculture in South Africa

Abstract

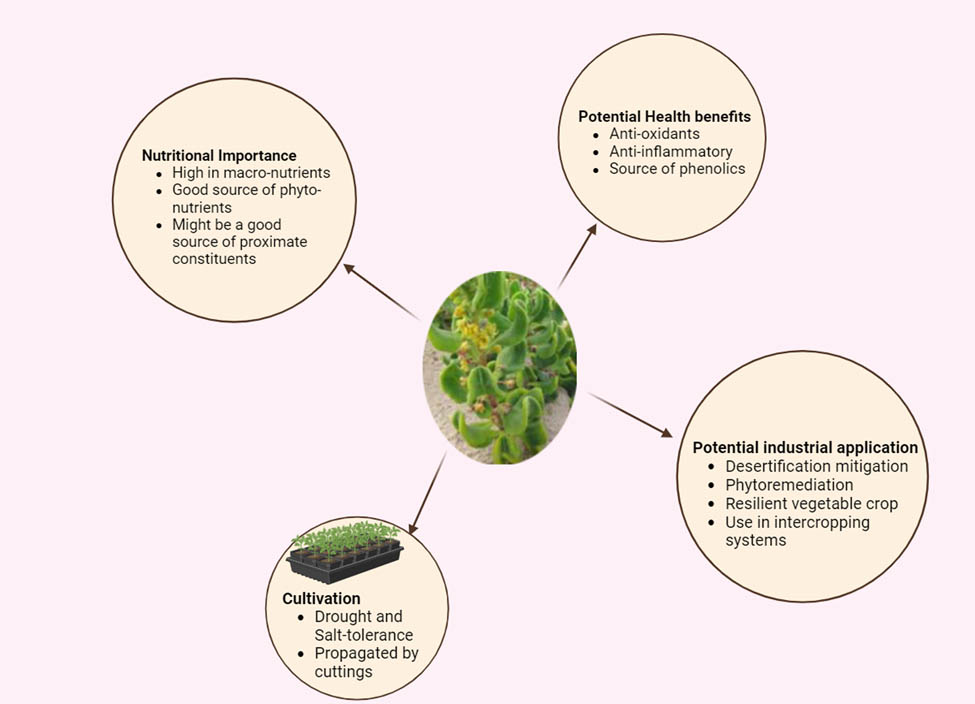

Global agriculture feeds over seven billion people and alarmingly, this number is expected to increase by a further 50% by 2050. To meet the additional food demand, the world development report has estimated that crop production should increase by 70–100% by 2050. However, climate change, expanding soil salinization, and the developing shortages of freshwater have negatively affected crop production of edible plants around the world. Current attempts to adapt to these conditions include the use of salt-tolerant plant species with potential economic value to fulfil the increasing food demand escalated by the increasing human population. The wild edible halophyte Tetragonia decumbens commonly known as dune spinach has the potential to be used as a leafy vegetable, a source of dietary salt, in phytoremediation and as a source of secondary metabolites. However, it remains underutilized in South Africa as commercial farming of this species has never been explored. This review examined the potential of domesticating the wild dune spinach as a leafy vegetable, describing its morphology and ecology, its propagation and cultivation requirements as well as its potential use on human health and in phytoremediation of saline soils. Furthermore, this analysis is expected to be useful towards further research and popularization of this underexploited halophyte.

Source

Avela Sogoni.

1 Introduction

The global agricultural industry already provides sustenance for more than seven billion people, and it is projected that this figure will rise by an additional 50% by the year 2050 [1]. The need for food production on a worldwide scale is now at its highest and already about 2 billion people are estimated to suffer from micronutrient deficiency problem [2]. To satisfy the growing need for food, agricultural output must rise by 70–100% by the year 2050 [3]. However, increasing soil salinity and global climate change have caused major constraints for agricultural productivity of staple crops such as wheat and maize [4]. Furthermore, high salinity in the soil triggers osmotic balance disruption in plants, limiting water intake and transpiration and consequently reduces yield [5]. Present efforts to adjust to these conditions include the use of wild edible plants that can tolerate high temperatures and salinity, and possess economic potential such as leafy vegetable, feed crop, and as pharmaceutical precursors [6,7]. This sparked a global interest in the crop production development of edible halophytes in combating the challenges of food and nutrient deficiency around the world [8].

In Europe and Latin America, culinary halophytes, such as Cichorium spinosum, Cichorium intybus, Capparis spinosa, Crithmum maritimum, and Portulaca oleracea to name a few, are used in many green dishes in restaurants and are favoured as main ingredients in salad dressing due to their saltiness and crunchiness [9,10]. In Korea, the young stalks of the edible halophyte Salicornia herbacea are eaten in a variety of ways, including as a seasoned vegetable, salad, and in fermented food [11]. Beside their culinary applications, the medicinal properties of various halophytes have been shown to be effective in treating and preventing chronic diseases that plague modern societies, such as cancer, heart disease, and diabetes [12,13]. This led to the inclusion of these plants on supermarket shelves in Europe and Asia, which resulted in the emergence of commercial cultivation due to the increasing demand of sustainable supply [14].

In South Africa, edible halophytes are still neglected and considered important mainly in the light of safeguarding biodiversity and are only valued in rural parts of the country during times of famine [15]. In the Cape Floristic Region (mainly the Western Cape province), many edible halophytes species are foraged rather than cultivated and are only known by a small group of local chefs and food enthusiasts due to their nutritional offering of healthy and affordable nutrient alternatives such as vitamins and minerals [16]. Afolayan and Jimoh [17] also reported that these neglected vegetables can contribute to diets by adding both micronutrients and bioactive compounds and could help eradicate nutrient deficiencies and reduce food insecurity at the household level. Furthermore, given the increasing global climate change and severe conditions that exist around the world, the use of native halophytes for food production in South Africa could be a climate change adaptation strategy [18]. Concurrently, it has also been stated that South Africa is approaching physical water scarcity by 2040, and its agricultural sector has been directly hampered by the recent drought [19]. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to cultivate crops that are adapted to harsh conditions within the framework of saline agriculture, to address the challenges of nutrient deficiency, saline soils, and water scarcity [20].

Seawater and salinized lands represent potentially cultivable areas for edible salt tolerate plants. In South Africa, the majority of the fields with these qualities are located close to coastal areas and suffer from salinity [21]. Therefore, saline agriculture with halophytes could enable coastal and saline soils to be productive. Hence, knowledge on the unexploited edible halophyte, Tetragonia decumbens is needed to support its cultivation potential on saline soils. This review examined the potential of domesticating the wild dune spinach as a leafy vegetable, describing its morphology and ecology, its propagation and cultivation requirements, as well as its potential benefits to human health and in phytoremediation.

2 Materials and methods

Research articles were downloaded from databases such as Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, and google scholar. The keywords used for searching the appropriate articles related to the title were “Dune spinach,” “Tetragonia,” “Wild edible halophytes,” “Phytoremediation,” Medicinal value of Tetragonia, and “Nutritional value of halophytes” or “coastal foods.” Boolean operators were used to combine search terms for optimal retrieval of relevant literature. Initial screening of search results was performed based on titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant articles. Articles used for this research were limited to the original research articles and those written in English Language only.

3 Taxonomy, morphology, and distribution of Tetragonia decumbens

Tetragonia decumbens Mill. is a perennial shrub and a member of the Aizoaceae family and its common names include Dune spinach (English) and Duinespinasie (Afrikaans) [22,23]. It is a sprawling shrub with branches or runners that can grow up to 1 m long. This perennial shrub has papillose-hirsute and oblong or lance-shaped fleshy leaves that feel hairy to the touch [24]. The glistening leaves have a shiny and warty appearance [25]. This is caused by the small, shiny, water-storage cells that cover the surface of the leaf. The inflorescences are axillary with one to three flowers, which usually start appearing from August to November (spring to summer). The seeds vary in size and have a brown hard outer casing with distinct rigid wings when dry [26].

The shrub occurs in few southern African countries including South Africa, Namibia, and Botswana (Figure 1). It is largely distributed along the coastal dunes (Figure 2), saline flats, and inland saline areas from southern Namibia to the Eastern Cape [27].

Geographical distribution map of T. decumbens (adapted from: http://www.ville-ge.ch/musinfo/bd/cjb/africa/details.php?langue=an&id=48025).

T. decumbens growing in its natural habitat along the strand beach, Cape Town, South Africa (Photo: Avela Sogoni).

4 Crop production of T. decumbens

4.1 Plant propagation

Tetragonia decumbens can be easily propagated by pulling mature runners from the sand with roots attached as cuttings. These can be directly planted into a well-drain soil which must be kept moist until the plant has established itself [28]. However, this practice could lead to over-harvesting as the species begin to gain popularity among coastal communities. Hence, an easy, suitable, and cost-effective propagation protocol should be in place. A propagation study conducted by Sogoni et al. [29] on root initiation of nodal stem cuttings of T. decumbens as influenced by rooting hormone and various rooting media found that cuttings planted on sand, peat mix (1:1) without hormone treatment, had better rooting percentage suggesting that the species can be easily propagated from cuttings in greenhouse conditions. This could be a cost-saving option for potential growers of the species since no additional cost on hormone treatment will be needed. In terms of seed propagation, no studies have been conducted. However, Rusch [28] reported the re-sprouting ability of the species when watered and suggested that this can be utilized for repeated harvest without the need to save seeds and re-sowing every year. Hence, further studies are required on repeated harvests of shoots and their phytonutrients, to promote large scale production of this leafy vegetable.

4.2 Cultivation trials

Tetragonia decumbens has been recently piloted as a possible commercial crop at a community garden in Khayelitsha, Cape Town, South Africa (Figure 3). Rusch [28] reported that rooted stem cuttings of the species can be easily grown in well-drained media such as sand or loamy soil. For optimal growth, the media should be kept moist until the cuttings have established, thereafter, they should be watered three times a week. This was also supported by the pot experiment of Tembo-Phiri [26] who reported that T. decumbens can be grown with water level maintained at 25% pot capacity (a pot volume of 3.4 dm3). When grown under a nutrient film hydroponic system, the species performed well in silica sand with the application of a full nutrient solution with low electrical conductivity [23]. This leafy vegetable was also successfully cultivated by Sogoni et al. [30] under salt stress in soilless culture (Figure 4). The cuttings were planted in pots containing sand: peat mix (1:1) and a total of 300 mL of nutrient solution were prepared for each pot with and/or without NaCl addition. The plants were then watered every 3 days. The nutrient solution was created by adding NUTRIFEED™ (manufactured by Starke Ayres Pty. Ltd, South Africa) to municipal water at 10 g per 5 L. The nutrient solution contained the following ingredients: N (65 mg/kg), P (27 mg/kg), K (130 mg/kg), Mg (22 mg/kg), Ca (70 mg/kg), Cu (20 mg/kg), Fe (1,500 mg/kg), Zn (240 mg/kg), Mn (240 mg/kg), S (75 mg/kg), B (240 mg/kg), and Mo (10 mg/kg). Results revealed that the use of nutritive solution incorporated with 50 and 100 mM NaCl had a positive effect on crop development, minerals, and yield, with a pronounced effect at 50 followed by 100 mM as compared to the control. These findings suggest that dune spinach is a halophyte and hold the potential to be cultivated on saline soils. Nevertheless, anatomical, physiological, and biochemical responses of this species to saline conditions remain underexplored for precise bio-saline agriculture, hence further studies are recommended.

Site preparation in Khayelitsha for planting in sandy soil (Photo: Loubie Rusch). Adapted from: https://www.capetownbotanist.com/planting-wild-food-garden-at-moya-we/.

A trial experiment showing dune spinach response to salt stress (Photo: Avela Sogoni).

5 Possible adaptation mechanisms of T. decumbens for bio-saline agriculture

Plants are often exposed to unfavourable conditions such as salinity stress, which in some cases dramatically alter the physiological processes within the plant, causing a reduction in growth and yield [31]. However, some species classified as halophytes have been reported to possess various physiological, anatomical, and biochemical adaptations allowing them to adapt to or cope with abiotic stress [32]. The same cannot be said for dune spinach since its adaptation behaviour to saline environments remains undocumented. Potential adaptation mechanism in dune spinach could be explored by examining studies conducted on salt-tolerance mechanisms of other halophytes which are discussed below.

5.1 Ion transport, accumulation, and excretion

Ion transport (Na+ and Cl−) from roots to leaves, where they are compartmentalized in vacuoles, has been reported as a salt mitigation strategy in dicot halophytes [33]. Souid et al. [34] also reported that NaCl levels in roots are maintained by ion exportation to shoots, which reduces the toxic effects of salt at the root level. Concurrently, Al Hassan et al. [35] and González-Orenga et al. [36] reported Na+ and Cl− accumulation in leaves of various Limonium species, lending support to this dicot model. Nonetheless, high levels of Na+ can be associated with toxic effects, resulting in a decrease in other ions such as K+ and Ca2+ [5]. Thus, avoiding ion toxicity appears to be a crucial survival mechanism which is achieved by the development of specialized structures such as salt glands, and or trichomes responsible for the regulation of internal salt load for ion excretion and storage [37]. Species like Mesembryanthemum crystallinum, Atriplex portulacoides, Chenopodium quinoa, and Tetragonia tetragoniodes have been reported to possess bladder cells, or specialized structures where ions are sequestered under saline conditions (Figure 5) [38,39,40]. While in Sporobolus ioclados, Lasiurus scindicus, and Salsola imbricata, anatomical modifications observed were thick cuticle and epidermis, smaller and fewer stomata, higher proportion of storage tissues, and thickened endodermis [41,42,43]. Nevertheless, these anatomical modifications in T. decumbens are not reported in the literature. Thus, anatomical studies are needed to give better insight on the adaptation mechanism of this species under saline conditions.

![Figure 5

Sodium accumulation and intracellular distribution in leaf bladder cells of T. tetragoniodes subjected to salinity. (a) Control and (b) 30% seawater. Adapted from the study of Atzori et al. [44].](/document/doi/10.1515/opag-2022-0368/asset/graphic/j_opag-2022-0368_fig_005.jpg)

Sodium accumulation and intracellular distribution in leaf bladder cells of T. tetragoniodes subjected to salinity. (a) Control and (b) 30% seawater. Adapted from the study of Atzori et al. [44].

5.2 Osmolyte production

When inorganic ions accumulate excessively in the vacuoles of plant cells, they are compensated for by compatible osmolytes/solutes in the cytoplasm [45]. These osmolytes are non-toxic organic molecules and do not interfere with cellular metabolism even at high intracellular concentrations. They play important roles in plant responses to abiotic stress, such as osmotic adjustment and protein stabilization, as well as serving as “reactive oxygen species” (ROS) scavengers [46]. Osmolytes are chemically diverse, as they contain amino acids like proline, methylated proline, and quaternary ammonium compounds like glycine betaine.

Proline and glycine betaine are well known for their important roles in osmotic adjustment and anti-oxidative defence in abiotically stressed plants [47]. These osmolytes have been found in a variety of halophytes and are typically lower in plants grown in non-saline conditions but show a significant increase in plants exposed to salinity and drought stress [45]. According to Alasvandyari et al. [48], proline and glycine betaine accumulation in plant tissues is associated with higher salt tolerance in plants. As a result, determining the osmolytes in dune spinach will be critical in describing its salt-tolerance nature.

5.3 Activation of anti-oxidative enzymes

Different biotic and abiotic stressors, including salinity, are known to cause oxidative stress in plants by producing superoxide radicals via the Mehler reaction [45,49]. When created in excess, these free radicals disrupt the regular metabolic mechanisms in cytoplasm, mitochondria, and peroxisomes by causing oxidative damage to proteins and lipids, resulting in cell malfunctions and, ultimately, death [50]. To overcome this phenomenon, plants respond by activating the production and accumulation of antioxidant enzymes. These antioxidant enzymes contribute to the elimination of ROS and the maintenance of appropriate cellular redox. For example, superoxide dismutase (SOD) catalyses a conversion from two O2 radicals to H2O2 and O2 [51]. In alternative ways, several antioxidant enzymes can also eliminate the H2O2 such as catalases (CAT) and peroxidases by converting it to water [52], thus maintaining the adequate cellular redox state. High amount of SOD and CAT under saline cultivation has been reported in halophytes such as Bupleurum tenuissimum, Chenopodium quinoa, Kandelia obovate, and Mesembryanthemum crystallinum, respectively [53,54,55,56]. Concurrently, Jeeva [57] reported that Tetragonia tetragoniodes a close relative of dune spinach regulated the SOD enzyme activity in mitigating cell membrane injury under saline conditions.

When excessive highly toxic ROS are not eliminated by the antioxidative enzymes, halophytes are said to activate the accumulation of non-enzymatic compounds such as phenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins, and tannins to scavenge these highly toxic species [58]. This response has been reported in many halophytes, where increasing saline irrigation induced the increase in phenols and flavonoids to scavenge highly toxic free radicals [59]. Therefore, examining the activity of these anti-oxidative enzymes in dune spinach will be useful in improving the agronomical aspects of the species under saline cultivation.

6 Potential use of T. decumbens

6.1 Phytoremediation

Accumulation of toxic ions in agricultural lands caused by the application of chemical fertilizer and climate change has led to the loss of soil fertility and the phenomena of salinization and desertification, which makes soils unsuitable for cultivation [60]. To overcome this catastrophic phenomenon, farmers have been predominantly using chemical amendments for the amelioration of saline and sodic soils. However, this process has become expensive in developing countries due to the competing demand from industry [61]. Therefore, identifying cost-effective and environmentally friendly techniques is necessary [62]. Numerous researchers have introduced the use of phytoremediation as a low-cost option in restoring saline soils. Phytoremediation is the use of plants to remediate contaminated soils [63]. This includes the use of salt removing species to restore saline lands. T. decumbens not only has the potential to remove toxic ions from the soil but it can also be used as a food crop which is a win-win scenario for potential farmers. Currently, Jeeva [57] evaluated the performance and phytoremediation effect on the close relative of dune spinach, Tetragonia tetragoniodes in salt-affected soils and reported that sodic soil can be utilized for growing this crop and that it has the potential for mitigation of sodic soils. Bekmirzaev et al. [64] also found that mineral nutrition of Tetragonia tetragoniodes was positively affected by salt stress. This suggests that dune spinach might exhibit good potential for the amelioration of saline and sodic soils. Hence, further research should be conducted on the growth performance and phytoremediation effect of dune spinach in salt-affected soils under field experiments for easy implementation by local farmers. Additionally, dune spinach might also be a good companion when intercropped with conventional cash crops on saline soils.

6.2 Intercropping potential of T. decumbens

Intercropping is primarily utilized in developing countries to improve crop productivity and is defined as the practice of growing two or more species concurrently [65]. In South Africa, this practice is widely utilized by small-scale farmers to satisfy dietary needs and to reduce the risk of single crop failure [66]. However, intercropping with halophytes remains unexplored, even though the country is currently facing the challenges of saline soils and water shortages. The use of intercropping halophytes with conventional cash crops might be the potential solution in mitigating stress in areas where salt is of particular concern and reduce crop production [67]. Nevertheless, there are still few studies conducted on intercropping of conventional crops with halophytes around the world and South Africa is no exception. Zuccarini [68] showed that tomatoes intercropped with purslane and garden orache had reduced Na+ and Cl− concentrations in tissues and had increased fruit yield under saline conditions. The fruit yield increased at approximately 44% in tomatoes that were intercropped with purslane and achieved comparable yields to those grown without saline conditions. These results were currently supported by Jurado et al. [67], who reported that tomato plants intercropped with the halophyte Arthrocaulon macrostachyum had improved nutrient homeostasis and photosynthesis performance leading to enhanced fruit yield. Likewise, Simpson et al. [69] also found that watermelon intercropped with the halophyte orache (Atriplex hortensis L.) substantially enhanced the yield and fruit quality of watermelon under saline conditions. While Liang and Shi [70] discovered that cotton plants intercropped with Suaeda salsa and alfalfa had decreased salt accumulation in their tissues. It was also reported that these halophytes improved soil physicochemical properties and crop productivity in saline-alkali soils under mulched drip irrigation for 3 years under field experiment. These studies suggest that there is potential to grow conventional crops on saline lands by intercropping them with halophytes. However, studies on field experiments will be needed for longer periods to determine which cropping system will benefit producers and increase yields while mitigating salt stress in sensitive crops. Thus, field experiments on dune spinach should be conducted to assess its viability as an intercropping candidate.

6.3 Desertification and soil erosion alleviation

Desertification, normally known as land degradation, has resulted in significant environmental and socio-economic issues in several arid and semi-arid regions worldwide [71,72]. It causes soil erosion and nutrient degradation, significantly reducing land productivity and resulting in the decline of ecosystem functioning and services [72]. Furthermore, the rise in population growth and economic progress persistently exerts greater demands on land use, especially in emerging countries, where natural vegetation is cleared for farming and residential purposes [73,74,75]. The land degradation problem has been reported to affect all three elements of the critical triangle of developmental goals, namely, agricultural growth, poverty reduction, and sustainable resource management [76]. Therefore, it was pointed out by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification and soil erosion [73,77].

Sustainable mitigation strategies to combat desertification include the use of resilient species such as phreatophytes which uses different metabolic and physiological adaptations to prevent oxidative mutilation, nutritional imbalance, and osmotic stress under drought and saline conditions [78,79]. Phreatophytes generally grow in semi-arid and arid regions and satisfy their water and nutrient requirements by using extensive root systems to access groundwater, while stabilising the soil from erosion [80]. For example, Tamarix ramosissima, a drought-tolerant halophyte with high resistance to drought, wind erosion, and sand burial, has been widely used in desertification control in China [81]. Similarly, the halophyte Karelinia caspia exhibits both drought and salt tolerance [82], which allows it to play a role in reducing wind erosion and desertification [83]. The species is considered as an ecosystem engineer that plays a crucial role in improving semi-arid ecosystem productivity by mitigating desertification under global climate change [84]. Therefore, the use of South African halophytes such as T. decumbens could potentially mitigate soil erosion and desertification due to its tolerance to drought and salinity as well as its soil stabilizing ability. Hence, further studies are recommended on the desertification control ability of T. decumbens.

6.4 Food security

Water scarcity and rising soil salinity are significant global issues, particularly affecting agricultural outputs of conventional crops [3]. The alternative use of resilient crops like edible halophytes is crucial in remediating saline soils to fulfil the increasing food demand escalated by the increasing human population [71]. Throughout history, wild plants have served as important sources of nutrition during periods of drought and salinity and as dietary reinforcements, particularly in communities that rely on hunting and gathering [72]. Wild vegetables, along with other wild plant foods, are often known as the “hidden harvest” since they are gathered directly from the wild, such as agricultural fields and marshy regions, without any intentional cultivation for food purposes [73]. The failure to fully utilize these green vegetables has led to conclusive proof of metabolic abnormalities, specifically classified as malnutrition, undernutrition, and stunting. Thus, the inclusion of these neglected leafy greens including T. decumbens in human diets is necessary in reducing hidden hunger resulting from micro-nutrient deficiencies.

6.4.1 Tetragonia decumbens as a promising nutritious leafy vegetable

Edible halophytes are used in many green dishes in restaurants and have gained popularity in some cultures across the world due to their saltiness and crunchiness [85]. The species climatic adaptation to high temperatures, drought, and salinity compared to conventional leafy vegetable crops makes them an ideal choice in some countries [86]. Recently, upscale restaurants in Europe and Asia have started including these plants into their menus as novel ingredients that promote nutritious diet [87]. In Australia and Brazil, close relatives of dune spinach such as Tetragonia tetragoniodes, Tetragonia expansa, and Mesembryanthemum crystallinum are commercially cultivated as a new choice of nutrient-rich leafy vegetable [88]. The leaves and soft stems of these species are consumed in a variety of ways such as seasoned vegetable and as a fermented food. Moreover, the considerable proximate and mineral composition of these species as depicted in Table 1 supports their nutritional value. Carbohydrates for instance supply energy to muscle and brain and the high carbohydrate content obtained in these species indicate that they are a good source of carbohydrates. These species are also a good source of protein and contain less fibre. According to Friday and Uchenna Igwe [89], food that contains 12% or higher protein can regulate body metabolism, cellular function, and the production of amino acids [90]. Thus, reducing constipation, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases [91]. Also, the considerable amount of minerals recorded in these species suggests that consuming these plants could mitigate mineral deficiencies known for causing health problems.

| Nutritional value | T. tetragoniodes | T. expansa | M. crystallinum | T. decumebens |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture% | 60–92.7 | ND | 7.1–8.3 | ND |

| Crude protein% | 10–18.2 | ND | 13.1–15.2 | ND |

| Crude fibre% | 6–13.9 | ND | 18–21.6 | ND |

| Ash% | 11–13.9 | ND | 12–37.2 | ND |

| Fat% | 0.9–4.2 | ND | 1–2.1 | ND |

| Carbohydrate% | 40–50.6 | ND | 38–44.9 | ND |

| Na (mg/100 g) | 700–3,180 | 60–94 | 900–3,000 | 840–2,100 |

| K (mg/100 g) | 1,000–2,706 | 420–530 | 430–2,610 | 1,800–2,080 |

| Ca (mg/100 g) | 1,900–2,120 | 35–64 | 1,900–2,115 | 900–1,800 |

| Mg (mg/100 g) | 200–459 | 40–55 | 420–640 | 400–770 |

| P (mg/100 g) | 400–620 | ND | 270–330 | 400–540 |

| Fe (mg/100 g) | 0.8–4.5 | 0.5–1 | 28–43 | 12–18 |

| Zn (mg/100 g) | 0.7–1.29 | 0–0.3 | 6–11.7 | 4–6.3 |

| Vitamin C (mg/100 g) | 28–50.5 | 58–116 | 4–10 | ND |

Note: ND = no data retrieved.

In South Africa, T. decumbens as a leafy green vegetable remains underutilized as commercial farming of this species has never been explored. The leaves and soft stems of dune spinach have a salty taste and are used like green spinach, eaten raw in green salads, or cooked with other vegetables as demonstrated in Figure 6. Dune spinach can also be fermented, pickled, used in stews and soups, and particularly tasty in a stir-fry [28]. When boiled, it has a granular texture and tastes bland but when mixed with Oxalis pes-caprae (sorrel) and butter, makes a tasty dish [25]. More recently, the species has been found to possess a substantial amount of minerals when cultivated (Table 1). Plant-based mineral nutrients are known to be important components of human diet since they play a substantial role in the maintenance of certain physicochemical processes required to life [92]. High amounts of potassium (1,800–2,080 mg/100 g), calcium (900–1,800 mg/100 g), and magnesium (400–770 mg/100 g) recorded in the leaves of dune spinach exceed the daily recommended allowance for humans, suggesting that this neglected leafy vegetable can be an alternative source of nutritional minerals. Even though the edibility and promising potential of dune spinach as a fresh and processed vegetable has been documented, its nutritional composition has not been extensively explored [23]. Therefore, nutritional profiling of the edible parts of this species is crucial to justify and support its consumption among South African households.

![Figure 6

Oep ve Koep’s Sandveld restaurant dumplings with dune spinach (a) and Dune spinach salad served with feta cheese (b), adapted from Tembo-Phiri [26].](/document/doi/10.1515/opag-2022-0368/asset/graphic/j_opag-2022-0368_fig_006.jpg)

Oep ve Koep’s Sandveld restaurant dumplings with dune spinach (a) and Dune spinach salad served with feta cheese (b), adapted from Tembo-Phiri [26].

6.5 Potential consumer acceptance of T. decumbens

Consumer studies on the adoption and acceptance of edible halophytes have not been widely investigated in South Africa [99]. This might be attributed to the fact that the use of wild vegetables as a method to address food insecurity and mitigate climate change has been ignored and only recently has it gained attention [100]. Moreover, current research on wild leafy vegetables has focused primarily on promoting consumption through the provision of nutritional information and health advantages of including these veggies into one’s diet [101,102]. Despite this intervention, vegetable consumption is still a significant problem in sub-Saharan Africa leading to micronutrient deficiency [103]. Hence, gaining a comprehensive understanding of customers’ opinions of wild vegetables might provide valuable information on how to effectively promote their utilization and consumption [104]. This is because consumption and purchasing intention are critical elements in assessing the potential adoption of a food product [103]. The consumer acceptance process is significantly influenced by the appearance and taste aspects of a given food [105]. Research conducted in some regions of South Africa indicates that although the flavour of indigenous foods serves as a significant incentive for consumption, it also acts as a deterrent for others [106]. Hence, it is important to conduct research that promotes enhancements in the taste and flavour of wild edible species to stimulate public acceptance and use. Recently, a consumer acceptance study focusing on taste, texture, consumption and purchasing intent was conducted by Tembo-Phiri [26] on raw and cooked leaves of T. decumbens and M. crystallinum. The recipes were prepared by Ms. Loubie Rusch, a local food activist and chef as shown in Table 2. Twenty-four respondents consisting of 11 senior conservation ecology university students and 9 community members participated in a survey that explored the acceptance of these edible halophytes. Results revealed that cooked leaves of T. decumbens had a higher score of acceptance than the raw and cooked leaves of M. crystallinum. When assessing the consumption and purchasing intent, about 70% of the correspondence showed willingness to consume and purchase these vegetables if available in stores. These findings suggest that T. decumbens has potential to be adopted as leafy vegetable in South African households. However, studies with larger sample size might have a better significance in enhancing its domestication and consumption.

Recipes of raw and cooked T. decumbens and M. crystallinum leaves

| Raw salad meal | |

|---|---|

| 1 chopped onion | ½ chilli and ¼ ring of lemon |

| ½ chopped green pepper | 2 cm of peeled and finely chopped ginger |

| Juice of one lemon | Two cups of T. decumbens and M. crystallinum |

| Mix the finely chopped onions, green peppers, ginger, some green chilli, and lemon zest. Allow the mixture to marinate overnight in lemon juice and salt. Add chopped T. decumbens and M. crystallinum leaves and some olive oil to the mix 15 min before serving. | |

| Cooked meal | |

|---|---|

| 1 chopped onion | Olive oil for sauteing |

| ½ chopped green pepper and ½ chilli | 2 cm of peeled and finely chopped ginger |

| ¼ ring of lemon and ½ chopped tomato | ¼ teaspoon of salt |

| Reduce tomato in a saucepan by half to thicken and intensify flavour. Fry finely chopped chilli, onion, green pepper, ginger, and lemon rind until onion is translucent. Add reduced tomato and stir through for a minute. In a separate pan, add 1 tbsp of oil and stir fry the leaves of T. decumbens and M. crystallinum for 3 min or until just wilted. Stir the wilted greens into the tomato mix and adjust salt as needed | |

6.6 Potential of T. decumbens leaves as an alternative source of sodium

According to Klein [107], people who have switched to raw food diets and avoided salt experienced low levels of sodium in their blood as well as resultant weakness, fatigue, loss of appetite, and other health issues. Most patients who suffered from severe inflammatory bowel conditions caused by high numbers of bowel movements and hyperacidity have also experienced low sodium levels [108]. However, increasing the patients’ sodium levels to the normal range is sometimes a long process. Traditional health practitioners have suggested and used celery, the most known source of sodium in the diet. However, in some cases, this has been inadequate for improving sodium deficits within a reasonable time frame. When this happens, some health practitioners have advised the consumption of sea salt or intravenous saline as options to help avoid further physiological dysfunction and the spectre of seizures and cardio arrest [107]. Some edible halophytes have proven to be safe and healthful answers to sodium deficiency due to their high salt content when grown in saline conditions [108]. Zhang et al. [109] discovered that salt made from Salicornia bigelovii Torr. prevented the hypertensive effect that is associated with sodium deficiency. Moreover, Barroca et al. [110] evaluated the NaCl replacement by Sarcocornia perennis leaf powder in white bread. The results showed that the addition of this halophyte powder as a NaCl substitute improved nutrients and minerals as well as bread quality. With such benefits, South African edible halophytes including T. decumbens should be popularized as an edible substitute in improving sodium deficiency.

6.7 Therapeutic potential of T. decumbens

Most edible halophytes are considered as promising nutraceutics in other countries and have been documented for the treatment and prophylaxis against various chronic diseases that afflict modern societies [12]. Tetragonia tetragoniodes has been actively utilized in oriental medicine to treat stomach hypersecretion, gastric ulcers, dyspepsia, and even gastric cancer. Nevertheless, its close relative T. decumbens endemic to south Africa has not received any research attention, hence its potential medicinal value can be drawn from previous and current studies conducted on T. tetragoniodes and other closely related species.

6.7.1 Antioxidant potential

Halophytes are known to accumulate high amounts of total phenolics and flavonoids as a defence response to saline conditions. These compounds are well known for their antioxidant potential against active oxygen species and free radicals responsible for various chronic diseases that afflict modern societies. Leaf crude extracts of T. tetragoniodes have been reported to show strong 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl and ABTS radical scavenging activity. Lee et al. [111] isolated methoxyquercetin and quercetin as the main bioactive compounds responsible for this strong antioxidant effect. Likewise, a strong ferric reducing antioxidant power was noted in crude extracts of T. decumbens with increasing saline treatment [30]. Moreover, a more potent antiradical activity was also noted in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum, a close family relative of T. decumbens. The methanol extract of this species was reported to possess high scavenging activity against the ABTS synthetic radicals, superoxide anion, and inhibited the lipid peroxidation of linoleic acid [112,113]. Nevertheless, there are few studies conducted on the isolation of compounds responsible for the potent antiradical activity of the species in the genus Tetragonia, hence further studies are recommended.

6.7.2 Anti-inflammatory potential

Inflammation is induced by the response of a cell/tissue to infection, damage, or irritation. It is generally marked by fever, oedema, swelling, and aches [114]. During inflammation, mast cells are commonly mobilized to produce histamine. In this context, 6-methoxykaempferol isolated from T. tetragoniodes demonstrated an anti-inflammatory effect when consumed by diabetic mice by inhibiting histamine and improved blood circulation [115]. Likewise, 6-methoxyflavonols, kaempferol, and quercetin isolated from T. tetragoniodes were also tested on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase – 2 (COX-2) protein upregulation in RAW 264.7 cells [111]. The results showed that all the isolated compounds suppressed iNOS and COX-2, respectively. These two enzymatic pathways are involved in the synthesis of nitric oxide and prostaglandin, which causes inflammation. Thus, their suppression is crucial in controlling immune responses. Koa et al. [116] also reported the suppression effect of hydrosols extracted from T. tetragoniodes on these two enzymatic pathways in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Even though these studies show potential, further research on isolated compounds are required on chronic diseases induced by inflammation.

7 Challenges associated with utilization of T. decumbens as a leafy vegetable

7.1 Scarcity of indigenous knowledge transfer

Colonization, apartheid and urbanization have led to the removal of indigenous people from cultural lands which resulted in societies completely disassociated from the land and knowledge of the useful plants it offers [117,118]. As a result, many of these native plant species remain underutilized due to the loss of indigenous knowledge on their potential use. T. decumbens is no exception, as it is only known by a small group of local chefs and food enthusiast due to its nutritional offering of healthy and affordable nutrient-dense alternative [16].

7.2 Inadequate information on cultivation, post-harvest handling, and storage

Very little information is available about the adoption of T. decumbens from the wild to cultivation, particularly regarding the environmental and agronomic processes required from propagation to post-harvest handling. The inadequate evidence-based data to support its agronomic potential is a major challenge that hinders the commercialization of this plant. This is due to researchers focusing on their areas of interest or interesting studies with few dealings with basic agronomic studies on wild vegetables, which require extensive field work. According to Baldermann et al. [119], ineffective production, storage, and processing of the by-products together with the lack of baseline knowledge on the nutritional potential negatively affect the acceptance, utilization, and value addition of many wild vegetables. Thus, further research is needed on the agronomic aspect of dune spinach to further promote its commercialization.

7.3 Marketing of wild vegetables in South Africa

Marketing of Halophytes in South Africa is still very low, as these species are only popular among senior citizens and are marketed through street vendors [120]. Despite their potential as nutritional and processed foods, they are rarely found in supermarkets and upmarket groceries in South Africa. This has greatly contributed to their reduced consumption among citizens. To increase their potential consumption and promotion, there should be integration between local producers and supply outlets. This will allow linkage of various market actors, which will increase the supply and efficiency in the chains.

8 Prospects of unlocking the potential use of dune spinach

8.1 Holistic research approach and improved policy framework

Holistic research on halophytes in South Africa has been ignored by policymakers and researchers, although they are currently attracting interest in other parts of the world due to their adaptive nature to salinity and drought [121]. The Agricultural Research Council, Vegetables and Ornamental Plants, and Water Research Commission are major role players involved in the research and training of indigenous vegetables in South Africa [120]. However, there has been limited focus on halophyte research due to the current food security policy guiding research, production and marketing of agricultural produce, which pays limited or no attention to the promotion of halophytes as edible vegetables. Changing such policies and improved research funding as well as collaboration between universities and government research institutions could promote intensive research on edible halophytes. This will then unlock the resource value of dune spinach through validated findings to meet the needs of potential consumers and promote its commercialization.

8.2 Publication of research findings

It is through publication that the edible halophyte-based research, including its scientific and practical contributions, can be disseminated to the public in various ways, such as in journals, conferences, and reports. Hence, it is of utmost importance for researchers to publish their results in such platforms, so that it can be easily accessed by practitioners, potential growers, and consumers with similar interests. This will then contribute to advancing knowledge on edible halophytes and their vast application on human health in South Africa.

8.3 Awareness and education

Appropriate awareness and education on the benefits of halophytes will ultimately boost their consumption and cultivation. This can be achieved through the inclusion of agricultural education curricula in universities that deals with the agronomic aspects of indigenous vegetables in both commercial and communal areas. This will then upgrade the knowledge base of rural dwellers and low-income groups on the importance of these neglected edible species since wild vegetables are naturally less demanding to cultivate and are economical natural resources.

9 Conclusion

Tetragonia decumbens, an overlooked and underutilized halophyte with edible attributes, presents a convincing argument for its incorporation into dietary regimens and agricultural practices. This is due to its exceptional easy to grow methods, accompanied by its high nutritional value, promising consumer acceptance, and therapeutic potential. The promising capacity of this species to fulfil most of the recommended dietary allowance for essential nutrients such as sodium, magnesium, potassium, iron, zinc, and vitamin C for all age groups makes it a powerful ally in combating nutrient deficiencies. Moreover, its salt accumulating capabilities makes it a good candidate for phytoremediation of saline soils through various systems such as intercropping with salt-sensitive species. Likewise, the species deep root system, drought tolerance, and soil stabilization capacity, support its use in desertification control. Therefore, it can be concluded that the addition of T. decumbens to agricultural systems may enhance crop diversity, assure food security, improve food nutrition, and promote sustainable farming practices. Moreover, the restoration of this species may also have a significant impact in reclaiming infertile soil and improving food security. This makes it a prospective option for future food production, especially considering the changing climate.

Acknowledgements

We thank the financial support of the South African National Research Foundation (Grant no: 140847) towards this study.

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa, Grant no: 140847.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal, reviewed all the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. A.S.: conceptualization and writing the original draft of the manuscript; C.L.: funding acquisition and critical revision of the article. M.O.J. and S.N.: critical review of the article with technical inputs. L.K.: supervision and critical revision of the article.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Loconsole D, Murillo-Amador B, Cristiano G, De Lucia B. Halophyte common ice plants: A future solution to arable land salinization. Sustainability. 2019;11:6076. 10.3390/su11216076.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Ogunniyi AI, Mavrotas G, Olagunju KO, Fadare O, Adedoyin R. Governance quality, remittances and their implications for food and nutrition security in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2020;127:104752. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104752.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Singh A. Soil salinity: A global threat to sustainable development. Soil Use Manag. 2022;38:39–67. 10.1111/SUM.12772.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Corwin DL. Climate change impacts on soil salinity in agricultural areas. Eur J Soil Sci. 2021;72:842–62. 10.1111/ejss.13010.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Amerian M, Palangi A, Gohari G, Ntatsi G. Enhancing salinity tolerance in cucumber through Selenium biofortification and grafting. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24:1–16. 10.1186/S12870-023-04711-Z/TABLES/4.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Ventura Y, Sagi M. Halophyte crop cultivation: The case for salicornia and sarcocornia. Env Exp Bot. 2013;92:144–53. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2012.07.010.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Debez A, Saadaoui D, Slama I, Huchzermeyer B, Abdelly C. Responses of Batis maritima plants challenged with up to two-fold seawater NaCl salinity. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2010;173:291–9. 10.1002/jpln.200900222.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Kashyap SP, Kumari N, Mishra P, Moharana DP, Aamir M. Tapping the potential of Solanum lycopersicum L. pertaining to salinity tolerance: perspectives and challenges. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2021;68:2207–33. 10.1007/s10722-021-01174-9.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Jang H-S, Kim K-R, Choi S-W, Woo M-H, Choi J-H. Antioxidant and antithrombus activities of enzyme-treated Salicornia herbacea extracts. Ann Nutr Metab. 2007;51:119–25. 10.1159/000100826.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Petropoulos S, Karkanis A, Martins N, Ferreira ICFR. Phytochemical composition and bioactive compounds of common purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) as affected by crop management practices. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2016;55:1–10. 10.1016/j.tifs.2016.06.010.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Sánchez-Gavilán I, Rufo L, Rodríguez N, de la Fuente V. On the elemental composition of the Mediterranean euhalophyte Salicornia patula Duval-Jouve (Chenopodiaceae) from saline habitats in Spain (Huelva, Toledo and Zamora). Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:2719–27. 10.1007/s11356-020-10663-w.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Ksouri R, Ksouri WM, Jallali I, Debez A, Magné C, Hiroko I, et al. Medicinal halophytes: Potent source of health promoting biomolecules with medical, nutraceutical and food applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2012;32:289–326. 10.3109/07388551.2011.630647.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Petropoulos SA, Karkanis A, Martins N, Ferreira ICFR. Edible halophytes of the Mediterranean basin: Potential candidates for novel food products. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2018;74:69–84. 10.1016/j.tifs.2018.02.006.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Castañeda-Loaiza V, Oliveira M, Santos T, Schüler L, Lima AR, Gama F, et al. Wild vs cultivated halophytes: Nutritional and functional differences. Food Chem. 2020;333:127536. 10.1016/J.FOODCHEM.2020.127536.Search in Google Scholar

[15] Ben Hamed K, Custódio L. How could halophytes provide a sustainable alternative to achieve food security in marginal lands? In: Hasanuzzaman M, Nahar KM, editors. Ecophysiology, abiotic stress responses and utilization of halophytes. Singapore: Springer; 2019. p. 259–70. 10.1007/978-981-13-3762-8_12.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Botha MS, Cowling RM, Esler KJ, de Vynck JC, Cleghorn NE, Potts AJ. Return rates from plant foraging on the Cape south coast: Understanding early human economies. Quat Sci Rev. 2020;235:106129. 10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.106129.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Afolayan AJ, Jimoh FO. Nutritional quality of some wild leafy vegetables in South Africa. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2009;60:424–31. 10.1080/09637480701777928.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Mndi O, Sogoni A, Jimoh MO, Wilmot CM, Rautenbach F, Laubscher CP. Interactive effects of salinity stress and irrigation intervals on plant growth, nutritional value, and phytochemical content in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L. Agriculture. 2023;13:1026. 10.3390/AGRICULTURE13051026.Search in Google Scholar

[19] Bischoff-Mattson Z, Maree G, Vogel C, Lynch A, Olivier D, Terblanche D. Shape of a water crisis: Practitioner perspectives on urban water scarcity and “Day Zero” in South Africa. Water Policy. 2020;22:193–210. 10.2166/wp.2020.233.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Panta S, Flowers T, Lane P, Doyle R, Haros G, Shabala S. Halophyte agriculture: Success stories. Env Exp Bot. 2014;107:71–83. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2014.05.006.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Malan M, Müller F, Cyster L, Raitt L, Aalbers J. Heavy metals in the irrigation water, soils and vegetables in the Philippi horticultural area in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Env Monit Assess. 2015;187:1–8. 10.1007/s10661-014-4085-y.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Forrester J. Tetragonia decumbens | PlantZAfrica; 2004. http://pza.sanbi.org/tetragonia-decumbens (accessed April 22, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

[23] Nkcukankcuka M, Jimoh MO, Griesel G, Laubscher CP. Growth characteristics, chlorophyll content and nutrients uptake in Tetragonia decumbens Mill. cultivated under different fertigation regimes in hydroponics. Crop Pasture Sci. 2021;72:1–12. 10.1071/CP20511.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Snijman DA. Plants of the Greater Cape Floristic Region: the extra Cape flora. Strelitzia. Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute; 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[25] Van Wyk BE, Gericke N. People’s plants – a guide to useful plants of Southern Africa. 2nd edn. Pretoria, South Africa: Briza Publications; 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Tembo-Phiri C. Edible Fynbos Plants: A soil type and irrigation regime investigation on Tetragonia decumbens and Mesembryanthemum crystallinum. Msc. Stellenbosch: University of Stellenbosch; 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Klak C, Hanáček P, Bruyns PV. Out of southern Africa: Origin, biogeography and age of the Aizooideae (Aizoaceae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;109:203–16. 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.12.016.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Rusch L. The cape wild food garden: a pilot cultivation project. Lyndoch, Stellenbosch: Sustainability Institute; 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Sogoni A, Jimoh MO, Laubscher CP, Kambizi L. Effect of rooting media and IBA treatment on rooting response of South African dune spinach (Tetragonia decumbens): an underutilized edible halophyte. Acta Hortic, vol. 1356, International Society for Horticultural Science; 2022. p. 319–25. 10.17660/ActaHortic.2022.1356.38.Search in Google Scholar

[30] Sogoni A, Jimoh MO, Kambizi L, Laubscher CP. The impact of salt stress on plant growth, mineral composition, and antioxidant activity in Tetragonia decumbens mill.: An underutilized edible halophyte in South Africa. Horticulturae. 2021;7:140. 10.3390/horticulturae7060140.Search in Google Scholar

[31] Jimoh MO, Afolayan AJ, Lewu FB. Suitability of Amaranthus species for alleviating human dietary deficiencies. South Afr J Bot. 2018;115:65–73. 10.1016/j.sajb.2018.01.004.Search in Google Scholar

[32] Barreira L, Resek E, Rodrigues MJ, Rocha MI, Pereira H, Bandarra N, et al. Halophytes: Gourmet food with nutritional health benefits? J Food Compos Anal. 2017;59:35–42. 10.1016/J.JFCA.2017.02.003.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Munns R, Tester M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:651–81. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Souid A, Gabriele M, Longo V, Pucci L, Bellani L, Smaoui A, et al. Salt tolerance of the halophyte Limonium delicatulum is more associated with antioxidant enzyme activities than phenolic compounds. Funct Plant Biol. 2016;43:607–19. 10.1071/FP15284.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Al Hassan M, Estrelles E, Soriano P, López-Gresa MP, Bellés JM, Boscaiu M, et al. Unraveling salt tolerance mechanisms in halophytes: A comparative study on four mediterranean Limonium species with different geographic distribution patterns. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1438. 10.3389/fpls.2017.01438.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] González-Orenga S, Ferrer-Gallego PP, Laguna E, López-Gresa MP, Donat-Torres MP, Verdeguer M, et al. Insights on salt tolerance of two endemic limonium species from Spain. Metabolites. 2019;9:294. 10.3390/metabo9120294.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Kuster VC, da Silva LC, Meira RMSA. Anatomical and histochemical evidence of leaf salt glands in Jacquinia armillaris Jacq. (Primulaceae). Flora. 2020;262:151493. 10.1016/J.FLORA.2019.151493.Search in Google Scholar

[38] Agarie S, Shimoda T, Shimizu Y, Baumann K, Sunagawa H, Kondo A, et al. Salt tolerance, salt accumulation, and ionic homeostasis in an epidermal bladder-cell-less mutant of the common ice plant Mesembryanthemum crystallinum. J Exp Bot. 2007;58:1957–67. 10.1093/JXB/ERM057.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Shabala S. Learning from halophytes: physiological basis and strategies to improve abiotic stress tolerance in crops. Ann Bot. 2013;112:1209–21. 10.1093/AOB/MCT205.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Parida AK, Veerabathini SK, Kumari A, Agarwal PK. Physiological, anatomical and metabolic implications of salt tolerance in the halophyte Salvadora persica under hydroponic culture condition. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:184129. 10.3389/FPLS.2016.00351/BIBTEX.Search in Google Scholar

[41] Naz N, Fatima S, Hameed M, Naseer M, Batool R, Ashraf M, et al. Adaptations for salinity tolerance in Sporobolus ioclados (Nees ex Trin.) Nees from saline desert. Flora. 2016;223:46–55. 10.1016/J.FLORA.2016.04.013.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Naz N, Fatima S, Hameed M, Ashraf M, Naseer M, Ahmad F, et al. Structural and functional aspects of salt tolerance in differently adapted ecotypes of Aeluropus lagopoides from saline desert habitats. Int J Agric. Biol. 2018;20:41–51.Search in Google Scholar

[43] Naz N, Fatima S, Hameed M, Ahmad F, Ahmad MSA, Ashraf M, et al. Modulation in plant micro-structures through soil physicochemical properties determines survival of Salsola imbricata Forssk. in Hypersaline environments. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2022;22:861–81. 10.1007/S42729-021-00697-5/FIGURES/10.Search in Google Scholar

[44] Atzori G, Nissim W, Macchiavelli T, Vita F, Azzarello E, Pandolfi C, et al. Tetragonia tetragonioides (Pallas) Kuntz. as promising salt-tolerant crop in a saline agricultural context. Agric Water Manag. 2020;240:106261. 10.1016/J.AGWAT.2020.106261.Search in Google Scholar

[45] González-Orenga S, Grigore M-N, Boscaiu M, Vicente O. Constitutive and induced salt tolerance mechanisms and potential uses of Limonium Mill. Species. Agronomy. 2021;11:413. 10.3390/agronomy11030413.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Ejaz S, Fahad S, Anjum MA, Nawaz A, Naz S, Hussain S, et al. Role of osmolytes in the mechanisms of antioxidant defense of plants. Sustainable agriculture reviews. Cham: Springer; 2020. p. 95–117. 10.1007/978-3-030-38881-2_4.Search in Google Scholar

[47] Rady MOA, Semida WM, Abd El-Mageed TA, Hemida KA, Rady MM. Up-regulation of antioxidative defense systems by glycine betaine foliar application in onion plants confer tolerance to salinity stress. Sci Hortic. 2018;240:614–22. 10.1016/j.scienta.2018.06.069.Search in Google Scholar

[48] Alasvandyari F, Mahdavi B, Hosseini SM. Glycine betaine affects the antioxidant system and ion accumulation and reduces salinity-induced damage in safflower seedlings. Arch Biol Sci. 2017;69:139–47. 10.2298/ABS160216089A.Search in Google Scholar

[49] Rodrigues de Queiroz A, Hines C, Brown J, Sahay S, Vijayan J, Stone JM, et al. The effects of exogenously applied antioxidants on plant growth and resilience. Phytochem Rev. 2023;2023:1–41. 10.1007/S11101-023-09862-3.Search in Google Scholar

[50] Saleem A, Zulfiqar A, Ali B, Naseeb MA, Almasaudi AS, Harakeh S. Iron sulfate (FeSO4) improved physiological attributes and antioxidant capacity by reducing oxidative stress of Oryza sativa L. Cultivars in alkaline soil. Sustainability. 2022;14:16845. 10.3390/SU142416845.Search in Google Scholar

[51] Zulfiqar F, Ashraf M. Antioxidants as modulators of arsenic-induced oxidative stress tolerance in plants: An overview. J Hazard Mater. 2022;427:127891. 10.1016/J.JHAZMAT.2021.127891.Search in Google Scholar

[52] García-Caparrós P, De Filippis L, Gul A, Hasanuzzaman M, Ozturk M, Altay V, et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant metabolism under adverse environmental conditions: a review. Bot Rev. 2020;1–46. 10.1007/s12229-020-09231-1.Search in Google Scholar

[53] González-Orenga S, Leandro MEDA, Tortajada L, Grigore MN, Llorens JA, Ferrer-Gallego PP, et al. Comparative studies on the stress responses of two Bupleurum (Apiaceae) species in support of conservation programmes. Env Exp Bot. 2021;191:104616. 10.1016/J.ENVEXPBOT.2021.104616.Search in Google Scholar

[54] Parvez S, Abbas G, Shahid M, Amjad M, Hussain M, Asad SA, et al. Effect of salinity on physiological, biochemical and photostabilizing attributes of two genotypes of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) exposed to arsenic stress. Ecotoxicol Env Saf. 2020;187:109814. 10.1016/J.ECOENV.2019.109814.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Hasanuzzaman M, Inafuku M, Nahar K, Fujita M, Oku H. Nitric oxide regulates plant growth, physiology, antioxidant defense, and ion homeostasis to confer salt tolerance in the Mangrove Species, Kandelia obovata. Antioxidants. 2021;10:611. 10.3390/ANTIOX10040611.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Mohamed E, Ansari N, Yadav DS, Agrawal M, Agrawal SB. Salinity alleviates the toxicity level of ozone in a halophyte Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L. Ecotoxicology. 2021;30:689–704. 10.1007/S10646-021-02386-6/FIGURES/1.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Jeeva S. Studies on the performance and phytoremediation effect of underutilized leafy vegetables in salt affected soils. Int J Chem Stud. 2020;8:1762–4. 10.22271/chemi.2020.v8.i2aa.9015.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Azeem M, Pirjan K, Qasim M, Mahmood A, Javed T, Muhammad H, et al. Salinity stress improves antioxidant potential by modulating physio-biochemical responses in Moringa oleifera Lam. Sci Rep. 2023;13:1–17. 10.1038/s41598-023-29954-6.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[59] Kumari A, Parida AK, Rangani J, Panda A. Antioxidant activities, metabolic profiling, proximate analysis, mineral nutrient composition of Salvadora Persica fruit unravel a potential functional food and a natural source of pharmaceuticals. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:61. 10.3389/FPHAR.2017.00061/FULL.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Hamzah A, Hapsari RI, Wisnubroto EI. Phytoremediation of Cadmium-contaminated agricultural land using indigenous plants. Int J Env Agric Res. 2016;2:8–14.Search in Google Scholar

[61] Hasanuzzaman M, Nahar K, Alam MM, Bhowmik PC, Hossain MA, Rahman MM, et al. Potential use of halophytes to remediate saline soils. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014(1):589341. 10.1155/2014/589341.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[62] Yan A, Wang Y, Tan SN, Mohd Yusof ML, Ghosh S, Chen Z. Phytoremediation: a promising approach for revegetation of heavy metal-polluted land. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:359. 10.3389/fpls.2020.00359.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[63] Jacob JM, Karthik C, Saratale RG, Kumar SS, Prabakar D, Kadirvelu K, et al. Biological approaches to tackle heavy metal pollution: A survey of literature. J Env Manage. 2018;217:56–70. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.03.077.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Bekmirzaev G, Ouddane B, Beltrao J, Fujii Y. The impact of salt concentration on the mineral nutrition of Tetragonia tetragonioides. Agriculture. 2020;10:238. 10.3390/agriculture10060238.Search in Google Scholar

[65] De La Fuente EB, Suárez SA, Lenardis AE, Poggio SL. Intercropping sunflower and soybean in intensive farming systems: Evaluating yield advantage and effect on weed and insect assemblages. NJAS – Wagening J Life Sci. 2014;70:47–52. 10.1016/j.njas.2014.05.002.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Bantie YB, Abera FA, Woldegiorgis TD. Competition indices of intercropped lupine (Local) and small cereals in additive series in West Gojam, North Western Ethiopia. Am J Plant Sci. 2014;5:1296–305. 10.4236/ajps.2014.59143.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Jurado C, Díaz-Vivancos P, Gregorio BE, Acosta-Motos JR, Hernández JA. Effect of halophyte-based management in physiological and biochemical responses of tomato plants under moderately saline greenhouse conditions. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024;206:108228. 10.1016/J.PLAPHY.2023.108228.Search in Google Scholar

[68] Zuccarini P. Ion uptake by halophytic plants to mitigate saline stress in Solanum lycopersicon L., and different effect of soil and water salinity. Soil Water Res. 2008;3:62–73.10.17221/25/2008-SWRSearch in Google Scholar

[69] Simpson C, Franco J, King S, Volder A. Intercropping halophytes to mitigate salinity stress in Watermelon. Sustainability. 2018;10:681. 10.3390/su10030681.Search in Google Scholar

[70] Liang J, Shi W. Cotton/halophytes intercropping decreases salt accumulation and improves soil physicochemical properties and crop productivity in saline-alkali soils under mulched drip irrigation: A three-year field experiment. Field Crop Res. 2021;262:108027. 10.1016/j.fcr.2020.108027.Search in Google Scholar

[71] Roy P, Pal SC, Chakrabortty R, Chowdhuri I, Saha A, Ruidas D, et al. Climate change and geo-environmental factors influencing desertification: a critical review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2024;1–14. 10.1007/S11356-024-32432-9/FIGURES/7.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Tariq A, Ullah A, Sardans J, Zeng F, Graciano C, Li X, et al. Alhagi sparsifolia: An ideal phreatophyte for combating desertification and land degradation. Sci Total Environ. 2022;844:157228. 10.1016/J.SCITOTENV.2022.157228.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[73] Yan Z, Guo Y, Sun B, Gao Z, Qin P, Li Y, et al. Combating land degradation through human efforts: Ongoing challenges for sustainable development of global drylands. J Env Manage. 2024;354:120254. 10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2024.120254.Search in Google Scholar

[74] Zhao Y, Chang C, Zhou X, Zhang G, Wang J. Land use significantly improved grassland degradation and desertification states in China over the last two decades. J Env Manage. 2024;349:119419. 10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2023.119419.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[75] Kulik KN, Vlasenko MV. Experience in implementing major national projects to combat degradation and desertification in Russia. Case Stud Chem Environ Eng. 2024;9:100583. 10.1016/J.CSCEE.2023.100583.Search in Google Scholar

[76] Owusu AB, Fynn IEM, Adu-Boahen K, Kwang C, Mensah CA, Atugbiga JA. Rate of desertification, climate change and coping strategies: Insights from smallholder farmers in Ghana’s Upper East Region. Environ Sustainability Indic. 2024;23:100433. 10.1016/J.INDIC.2024.100433.Search in Google Scholar

[77] Gui D, Liu Q, Martínez-Valderrama J, Abd-Elmabod SK, Zeeshan A, Xu Z, et al. Desertification baseline: A bottleneck for addressing desertification. Earth Sci Rev. 2024;257:104892. 10.1016/J.EARSCIREV.2024.104892.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Ali AM, Salem HM. Salinity-induced desertification in oasis ecosystems: challenges and future directions. Environ Monit Assess. 2024;196(8):1–20. 10.1007/S10661-024-12804-X.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Parnian A, Parvizi H, Selmy S, Mushtaq Z. Haloculture: A pathway to reduce climate change consequences for societies. Integration of core sustainable development goals in rural areas. Cham: Springer; 2024. p. 385–413. 10.1007/978-3-031-60149-1_14.Search in Google Scholar

[80] Gao Y, Tariq A, Zeng F, Graciano C, Zhang Z, Sardans J, et al. Allocation of foliar-P fractions of Alhagi sparsifolia and its relationship with soil-P fractions and soil properties in a hyperarid desert ecosystem. Geoderma. 2022;407:115546. 10.1016/J.GEODERMA.2021.115546.Search in Google Scholar

[81] Zhang Q, Zhang X. Impacts of predictor variables and species models on simulating Tamarix ramosissima distribution in Tarim Basin, northwestern China. J Plant Ecol. 2012;5:337–45. 10.1093/JPE/RTR049.Search in Google Scholar

[82] Guo Q, Han J, Li C, Hou X, Zhao C, Wang Q, et al. Defining key metabolic roles in osmotic adjustment and ROS homeostasis in the recretohalophyte Karelinia caspia under salt stress. Physiol Plant. 2022;174:e13663. 10.1111/PPL.13663.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[83] Tariq A, Ullah A, Graciano C, Zeng F, Gao Y, Sardans J, et al. Combining different species in restoration is not always the right decision: Monocultures can provide higher ecological functions than intercropping in a desert ecosystem. J Env Manage. 2024;357:120807. 10.1016/J.JENVMAN.2024.120807.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[84] Kim G, Ahn J, Chang H, An J, Khamzina A, Kim G, et al. Effect of vegetation introduction versus natural recovery on topsoil properties in the dried Aral Sea bed. Land Degrad Dev. 2024;35:4121–32. 10.1002/LDR.5209.Search in Google Scholar

[85] Agudelo A, Carvajal M, Martinez-Ballesta M, del C. Halophytes of the Mediterranean Basin – Underutilized species with the potential to be nutritious crops in the scenario of the climate change. Foods. 2021;10:119. 10.3390/foods10010119.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[86] Ebert A. Potential of underutilized traditional vegetables and legume crops to contribute to food and nutritional security, income and more sustainable production systems. Sustainability. 2014;6:319–35. 10.3390/su6010319.Search in Google Scholar

[87] Lima AR, Castañeda-Loaiza V, Salazar M, Nunes C, Quintas C, Gama F, et al. Influence of cultivation salinity in the nutritional composition, antioxidant capacity and microbial quality of Salicornia ramosissima commercially produced in soilless systems. Food Chem. 2020;333:127525. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127525.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[88] Cecílio Filho AB, Bianco MS, Tardivo CF, Pugina GCM. Agronomic viability of New Zealand spinach and kale intercropping. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2017;89:2975–86. 10.1590/0001-3765201720160906.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[89] Friday C, Uchenna Igwe O. Phytochemical and nutritional profiles of Tetragonia tetragonioides leaves grown in Southeastern Nigeria. Chem Search J. 2021;12:1–5.Search in Google Scholar

[90] Zhao J, Zhang X, Liu H, Brown MA, Qiao S. Dietary protein and gut microbiota composition and function. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2018;20:145–54. 10.2174/1389203719666180514145437.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[91] Xiao F, Guo F. Impacts of essential amino acids on energy balance. Mol Metab. 2022;57:101393. 10.1016/J.MOLMET.2021.101393.Search in Google Scholar

[92] Salami SO, Adegbaju OD, Idris OA, Jimoh MO, Olatunji TL, Omonona S, et al. South African wild fruits and vegetables under a changing climate: The implications on health and economy. South Afr J Bot. 2022;145:13–27. 10.1016/J.SAJB.2021.08.038.Search in Google Scholar

[93] Onoiko OB. Bioactive compounds and pharmacognostic potential of Tetragonia tetragonioides. Biotechnol Acta. 2024;17:29–42. 10.15407/biotech17.01.029.Search in Google Scholar

[94] Walters K, Mattson N, Sipos L, Wei Chen J, Patloková K, Pokluda R. The effect of the daily light integral and spectrum on Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L. in an indoor plant production environment. Horticulturae. 2024;10:266. 10.3390/HORTICULTURAE10030266.Search in Google Scholar

[95] Rodríguez-Hernández M, del C, Garmendia I. Optimum growth and quality of the edible ice plant under saline conditions. J Sci Food Agric. 2022;102:2686–92. 10.1002/JSFA.11608.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[96] Kawashima LM, Valente Soares LM. Mineral profile of raw and cooked leafy vegetables consumed in Southern Brazil. J Food Compos Anal. 2003;16:605–11. 10.1016/S0889-1575(03)00057-7.Search in Google Scholar

[97] Mugo BM, Kiio J, Munyaka A. Effect of blanching time–temperature on potassium and vitamin retention/loss in kale and spinach. Food Sci Nutr. 2024. 10.1002/FSN3.4186.Search in Google Scholar

[98] Cebani S, Jimoh MO, Sogoni A, Wilmot CM, Laubscher CP. Nutrients and phytochemical density in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L. cultivated in growing media supplemented with dosages of nitrogen fertilizer. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2024;31:103876. 10.1016/J.SJBS.2023.103876.Search in Google Scholar

[99] Sogoni A. The effect of salinity and substrates on the growth parameters and antioxidant potential of Tetragonia decumbens (Dune spinach) for horticultural applications. Msc. Cape Town, South Africa: Cape Peninsula University of Technology; 2020.Search in Google Scholar

[100] Borelli T, Hunter D, Powell B, Ulian T, Mattana E, Termote C, et al. Born to eat wild: an integrated conservation approach to secure wild food plants for food security and nutrition. Plants. 2020;9:1299. 10.3390/PLANTS9101299.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[101] Bvenura C, Sivakumar D. The role of wild fruits and vegetables in delivering a balanced and healthy diet. Food Res Int. 2017;99:15–30. 10.1016/J.FOODRES.2017.06.046.Search in Google Scholar

[102] Imathiu S. Indigenous African leafy vegetables for food and nutrition security. J Food Secur. 2021;9:115–25. 10.12691/jfs-9-3-4.Search in Google Scholar

[103] Shembe PS, Ngobese NZ, Siwela M, Kolanisi U. The potential repositioning of South African underutilised plants for food and nutrition security: A scoping review. Heliyon. 2023;9:e17232. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17232.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[104] Pieterse E, Millan E, Schönfeldt HC. Consumption of edible flowers in South Africa: nutritional benefits, stakeholders’ views, policy and practice implications. Br Food J. 2023;125:2099–122. 10.1108/BFJ-10-2021-1091/FULL/XML.Search in Google Scholar

[105] Torrico DD, Nie X, Lukito D, Deb-Choudhury S, Hutchings SC, Realini CE. Consumer attitudes and acceptability toward Edible New Zealand Native plants. Sustainability. 2023;15:11592. 10.3390/SU151511592/S1.Search in Google Scholar

[106] Omotayo AO, Ndhlovu PT, Tshwene SC, Olagunju KO, Aremu AO. Determinants of household income and willingness to pay for indigenous plants in North West Province, South Africa: A two-stage heckman approach. Sustainability. 2021;13:5458. 10.3390/SU13105458.Search in Google Scholar

[107] Klein D. Sea asparagus. The salty salt-free vegetable; 2014. p. 1–4. https://olakaihawaii.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/OlakaiHawaii-Sea-Asparagus-Vibrance-no.10.pdf (accessed April 20, 2021).Search in Google Scholar

[108] Wang QZ, Liu XF, Shan Y, Guan FQ, Chen Y, Wang XY, et al. Two new nortriterpenoid saponins from Salicornia bigelovii Torr. and their cytotoxic activity. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:742–9. 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.02.013.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[109] Zhang S, Wei M, Cao C, Ju Y, Deng Y, Ye T, et al. Effect and mechanism of Salicornia bigelovii Torr. plant salt on blood pressure in SD rats. Food Funct. 2015;6:920–6. 10.1039/c4fo00800f.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[110] Barroca MJ, Flores C, Ressurreição S, Guiné R, Osório N, Moreira da Silva A. Re-Thinking Table Salt Reduction in Bread with Halophyte Plant Solutions. Appl Sci. 2023;13:5342. 10.3390/APP13095342.Search in Google Scholar

[111] Lee YG, Lee H, Ryuk JA, Hwang JT, Kim HG, Lee DS, et al. 6-Methoxyflavonols from the aerial parts of Tetragonia tetragonoides (Pall.) Kuntze and their anti-inflammatory activity. Bioorg Chem. 2019;88:102922. 10.1016/J.BIOORG.2019.102922.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[112] Hanen F, Riadh K, Samia O, Sylvain G, Christian M, Chedly A. Interspecific variability of antioxidant activities and phenolic composition in Mesembryanthemum genus. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:2308–13. 10.1016/J.FCT.2009.06.025.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[113] Kang YW, Joo NM. Comparative analysis on phytochemical properties, anti-oxidative, and anti-inflammatory activities of the different organs of the Common Ice Plant Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L. Appl Sci. 2023;13:2527. 10.3390/APP13042527.Search in Google Scholar

[114] Adeoye RI, Olopade ET, Olayemi IO, Okaiyeto K, Akiibinu MO. Nutritional and therapeutic potentials of Carica papaya Linn. seed: A comprehensive review. Plant Sci Today. 2024;11:671–80. 10.14719/pst.2843.Search in Google Scholar

[115] Lee YS, Kim SH, Yuk HJ, Lee GJ, Kim DS. Tetragonia tetragonoides (Pall.) Kuntze (New Zealand Spinach) prevents obesity and hyperuricemia in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients. 2018;10:1087. 10.3390/NU10081087.Search in Google Scholar

[116] Koa EY, Cho SH, Kang K, Kim G, Lee JH, Jeon YJ, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of hydrosols from Tetragonia tetragonoides in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. EXCLI J. 2017;16:521. 10.17179/EXCLI2017-121.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[117] Cavanagh E. The anatomy of a South African genocide: The extermination of the Cape San Peoples. J South Afr Am Stud. 2013;14:232–4. 10.1080/17533171.2013.778106.Search in Google Scholar

[118] La Croix S. The Khoikhoi population, 1652–1780: A review of the evidence and two new estimates. J Stud Econ Econom. 2018;42:15–34. 10.1080/10800379.2018.12097332.Search in Google Scholar

[119] Baldermann S, Blagojević L, Frede K, Klopsch R, Neugart S, Neumann A, et al. Are neglected plants the food for the future? CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2016;35:106–19. 10.1080/07352689.2016.1201399.Search in Google Scholar

[120] Maseko I, Mabhaudhi T, Tesfay S, Araya H, Fezzehazion M, Plooy C. African leafy vegetables: A review of status, production and utilization in South Africa. Sustainability. 2017;10:16. 10.3390/su10010016.Search in Google Scholar

[121] Beletse Y, Du Plooy I. Jansen van rensburg W. Water requirement of selected african leafy vegetables. In: Oelofse, A, Van Averbeke W, editors. Nutritional value and water use of African leafy vegetables for improved livelihoods. Pretoria: Water Research Commission; 2012. p. 100–22.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Optimization of sustainable corn–cattle integration in Gorontalo Province using goal programming

- Competitiveness of Indonesia’s nutmeg in global market

- Toward sustainable bioproducts from lignocellulosic biomass: Influence of chemical pretreatments on liquefied walnut shells

- Efficacy of Betaproteobacteria-based insecticides for managing whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), on cucumber plants

- Assessment of nutrition status of pineapple plants during ratoon season using diagnosis and recommendation integrated system

- Nutritional value and consumer assessment of 12 avocado crosses between cvs. Hass × Pionero

- The lacked access to beef in the low-income region: An evidence from the eastern part of Indonesia

- Comparison of milk consumption habits across two European countries: Pilot study in Portugal and France

- Antioxidant responses of black glutinous rice to drought and salinity stresses at different growth stages

- Differential efficacy of salicylic acid-induced resistance against bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae in rice genotypes

- Yield and vegetation index of different maize varieties and nitrogen doses under normal irrigation

- Urbanization and forecast possibilities of land use changes by 2050: New evidence in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam

- Organizational-economic efficiency of raspberry farming – case study of Kosovo

- Application of nitrogen-fixing purple non-sulfur bacteria in improving nitrogen uptake, growth, and yield of rice grown on extremely saline soil under greenhouse conditions

- Digital motivation, knowledge, and skills: Pathways to adaptive millennial farmers

- Investigation of biological characteristics of fruit development and physiological disorders of Musang King durian (Durio zibethinus Murr.)

- Enhancing rice yield and farmer welfare: Overcoming barriers to IPB 3S rice adoption in Indonesia

- Simulation model to realize soybean self-sufficiency and food security in Indonesia: A system dynamic approach