GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

-

Gengming Niu

, Jun Ren

und Liang Hong

Abstract

Introduction

Gap junction protein, alpha 1 (GJA1), which is correlated with recurrences and unfavorable prognoses in hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs), is one of the specific proteins expressed by activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).

Methods

Expression of GJA1 was compared between HCCs and nontumor tissues (NTs), between hepatic cirrhosis and NTs, and between primary and metastatic HCCs using transcriptomic datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus and the Integrative Molecular Database of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. The in vitro activities of GJA1 were investigated in cultured HSCs and HCC cells. The underlying mechanism was characterized using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis and validated by western blotting.

Results

The expression of GJA1 was significantly increased in HCCs and hepatic cirrhosis compared to that in NTs. GJA1 was also overexpressed in pulmonary metastases from HCCs when compared with HCCs without metastasis. Overexpression of GJA1 promoted while knockdown of GJA1 inhibited proliferation and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β-mediated activation and migration of cultured HSCs. Overexpression of GJA1 by lentivirus infection promoted proliferation and migration, while conditioned medium from HSCs overexpressing GJA1 promoted migration but inhibited proliferation of Hep3B and PLC-PRF-5 cells. Lentivirus infection with shGJA1 or conditioned medium from shGJA1-infected HSCs inhibited the proliferation and migration of HCCLM3 cells that had a high propensity toward lung metastasis. Mechanistically, GJA1 induced the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) in HSCs and HCCLM3 cells.

Conclusion

GJA1 promoted HCC progression by inducing HSC activation and the EMT in HSCs. GJA1 is potentially regulated by TGF-β and thus may be a therapeutic target to inhibit HCC progression.

1 Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most predominant and fatal malignancies worldwide [1]. Although immunization with vaccines against the hepatitis B virus could dramatically decrease the incidence of HCC in high-risk populations [2], this malignancy remains a huge health threat due to the high probability of metastasis [3]. Therefore, it is crucial to characterize the underlying mechanisms of HCC metastasis to develop effective therapeutic measures and improve patient survival.

Activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) initiates HCC recurrence and metastasis [4,5,6,7]. Stimulated by various profibrotic factors such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, HSCs are activated and transdifferentiated into myofibroblasts that secrete extracellular matrix proteins into the stroma to promote the development of hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis, which are predisposed to and often interact with HCCs [7,8,9,10]. Activated HSCs also express a number of specific genes that facilitate HCC recurrence [4,5]. By inhibiting HSC activation and minimizing the adverse effects of profibrotic factors, fibrotic and cirrhotic liver diseases may be effectively treated [9,10,11], and HCC progression may be inhibited.

Gap junction protein, alpha 1 (GJA1), also known as connexin 43 (Cx43), belongs to the connexin family. It mediates the intercellular transmission of small molecules by means of gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) [12]. GJA1 mediates GJIC between neighboring HSCs and is upregulated in activated HSCs in response to inflammatory and proliferative stimuli [13]. GJA1 has been associated with hepatic fibrosis in rats and HCC progression in patients and cultured cells [5,13,14,15]. However, there are conflicting reports regarding whether GJA1 suppresses fibrosis and HCC progression [16,17,18]. To eliminate this controversy, it is important to investigate whether GJA1 is actively involved in HSC activation and whether this involvement is functionally implicated in HCC progression.

In the current study, we used public datasets to compare GJA1 expression between HCCs and adjacent nontumor tissues (NTs), between hepatic cirrhosis and NTs, as well as between metastatic HCCs and HCCs without metastasis. We then examined the in vitro effects of GJA1 on HSC activation with or without TGF-β stimulation. In addition, we evaluated the direct and indirect effects of GJA1 on the proliferation and migration of cultured HCC cells. Finally, we characterized the underlying mechanism of action of GJA1.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Access to public datasets and the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)

Thirteen datasets including GSE6764 [19], GSE10143 [20], GSE14323 [21], GSE14520 [22,23], GSE22058 [24,25], GSE25097 [26,27,28], GSE36376 [29], GSE46444 [30], GSE54236 [31], GSE63898 [32], GSE76427 [33], the Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma Project of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA-LIHC),[1] and the Liver Cancer-RIKEN, JP Project from the International Cancer Genome Consortium [34] were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus [35] and the Integrative Molecular Database of Hepatocellular Carcinoma [36], and analyzed for GJA1 mRNA expression in cirrhosis, HCC, and hepatic NTs. These datasets included 1,438 NTs, 2,061 HCCs, and 94 cirrhotic liver tissues. In addition, two datasets of primary and metastatic HCCs were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE40367 [37] and GSE364 [38]). To explore potential mechanisms of GJA1 in HCC progression, a GSEA was employed using the TCGA-LIHC dataset.

2.2 Cell culture and lentivirus infection

The HSC-LX2 human hepatic stellate cell line was obtained from Shanghai Ke Lei Biological Technology (Shanghai, China). HCCLM3 cells were kind gifts from Dr. Lijie Ma from the Liver Cancer Institute, Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China. Hep3B, PLC-PRF-5, and SK-Hep1 cells were provided by Prof. Yongzhong Liu from the Shanghai Cancer Institute, Shanghai, China. All cell lines used in this study have been validated by short tandem repeat profiling methods. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM; BBI Life Sciences, Shanghai, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 µg/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). GFP-expressing lentivirus particles were prepared by Genechem (Shanghai, China). The vectors used were GV358 (for GJA1 and the vector control) and GV248 (for shGJA1 and the scrambled control). The target sequence for shGJA1 was CCAAACTGATGGTGTCAAT. The titration was 2E + 9 (TU/mL) for all types of lentiviruses.

2.3 Collection of conditioned medium (CM)

The CM from LX2 cells was collected as previously described [39]. Briefly, stably transfected cells (1 × 106) were seeded into 100 mm dishes containing 10 mL of DMEM with 10% FBS for 24 h and washed twice with serum-free DMEM. The cells were cultured in serum-free DMEM for another 24 h, and the supernatants were collected, centrifuged, filtered, and stored at −20°C until use.

2.4 Treatment of HSCs with recombinant human TGF-β1

HSCs were seeded in 100 mm dishes and 96-, 12-, and 6-well plates at the indicated concentrations with 10% FBS in the medium. After 24 h, the cells were serum-starved for 24 h and treated with recombinant hTGF-β1 (Univ-Bio, Shanghai, China) at a final concentration of 5 ng/mL, or with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as control and incubated for 24, 48, 72, or 96 h.

2.5 RNA extraction and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cell cultures using RNAiso Plus (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and reverse-transcribed and subjected to real-time reverse transcription-PCR using the 2−ΔΔCT method. The sequences for RT-PCR primers were the following: GJA1 forward primer, 5′-CAATCTCTCATGTGCGCTTCT-3′; and GJA1 reverse primer, 5′-GGCAACCTTGAGTTCTTCCTCT-3′. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as an internal control. Experiments were repeated three times, in duplicate.

2.6 Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from cell cultures at the indicated time points using radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) containing phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime Biotechnology) and proteinase inhibitor cocktail solution (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and quantitated using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Beyotime Biotechnology) as recommended by the manufacturers. Western blotting was performed as previously described [40] using rabbit anti-GJA1 polyclonal antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Univ-Bio) or a mouse anti-α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) monoclonal antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Univ-Bio). Other antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table A1. GAPDH (1:2,000 dilution, rabbit anti-human; Beyotime Biotechnology) was detected as a loading control. The grayscale values of protein bands were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.7 Proliferation assay

Stably transfected LX2, Hep3B, PLC-PRF-5, or HCCLM3 cells (2 × 103 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates with 10% FBS in the medium and cultivated for 24 h and then serum-starved for another 24 h. TGF-β1 or an equal volume of PBS was added and the cells were cultivated for 24, 48, 72, or 96 h. Then, 10 μL of cholecystokinin octapeptide-8 reagent [10% (v/v) in serum-free DMEM; Beyotime Biotechnology] was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (BioTek Synergy 2; BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

2.8 Migration assay

Stably transfected LX2, Hep3B, PLC-PRF-5, or HCCLM3 cells (4 × 105 cells/mL) were seeded in serum-free DMEM with or without TGF-β1 in the top chamber of a Transwell insert. The medium containing 20% FBS in the lower chamber served as a chemoattractant. After incubation for 24 h at 37°C, the cells on the top side of the membrane were removed with a cotton swab, and those on the bottom side were fixed with methanol for 20 min and stained with crystal violet (0.1% in PBS) for 15 min. Six randomly selected fields per well were photographed, and the numbers of migrated cells were counted.

2.9 Scratch wound healing assay

A monolayer scratch wound assay was conducted as previously described [41]. Briefly, stably transfected LX2 cells (4 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in 12-well plates with 10% FBS in the medium and grown to nearly 100% confluence. After 24 h of serum starvation, a scratch wound was generated with a 200 μL pipette tip. Wound closure was photographed at 0, 24, and 48 h.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) or GraphPad Prism7 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance was performed for continuous variables. Statistical significance was defined as a value of p < 0.05. All statistical tests were two-sided.

3 Results

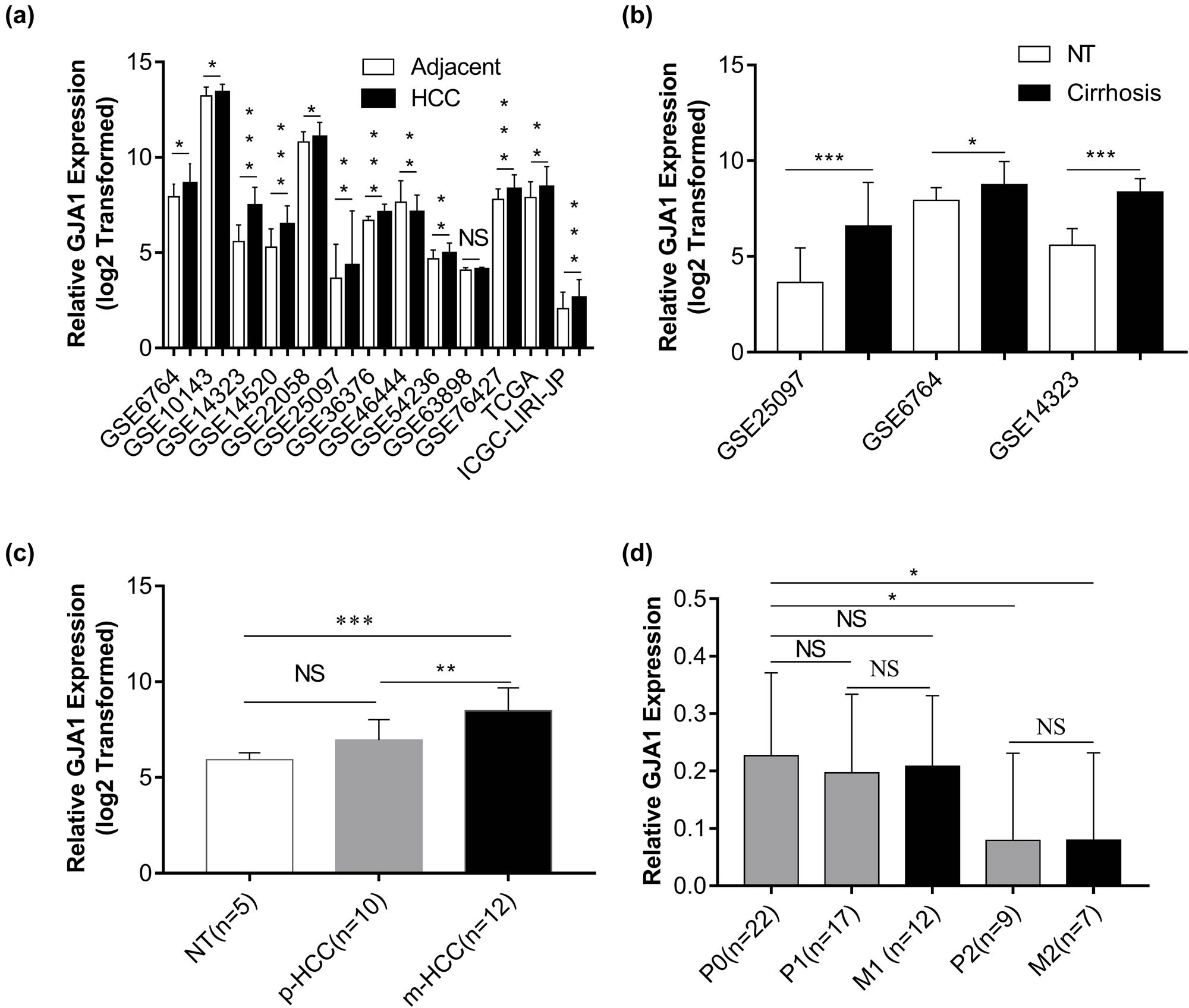

3.1 GJA1 is upregulated in HCCs and hepatic cirrhosis

Because the functional relevance of GJA1 in HCCs and hepatic cirrhosis remains unknown, we analyzed GJA1 mRNA expression with 13 public datasets. Figure 1a shows that in HCCs compared with adjacent NTs, GJA1 was significantly upregulated in 11 datasets, significantly downregulated in one dataset, and was similar in one dataset. In three of the datasets with cirrhosis samples, GJA1 expression was significantly increased in hepatic cirrhosis compared with that in NTs (Figure 1b). Surprisingly, by analyzing one dataset consisting of 5 NTs, 10 primary HCCs without metastasis (p-HCC), and 12 pulmonary metastases from HCCs (m-HCC), we found that GJA1 expression was significantly increased in pulmonary metastases from HCCs compared to that in NTs or primary HCCs without metastasis (Figure 1c). By contrast, in another dataset that contained 22 primary HCCs without metastasis (P0), 17 primary lesions (P1) and 12 metastases (M1) from HCCs with intrahepatic spread metastasis, and 9 primary lesions (P2) and 7 metastases (M2) from HCCs with portal vein tumor thrombus metastasis, the expression of GJA1 was significantly decreased in P2 and M2 samples while decreased with no significance in P1 and M1 samples, compared to that in P0 samples (Figure 1d). Besides, GJA1 expression was quite similar between primary tumor lesions and their matched distant metastases (Figure 1d). Taken together, these results indicated that GJA1 transcription was enhanced in HCCs, hepatic cirrhosis, and pulmonary metastases from HCCs, but diminished in portal vein tumor thrombus metastasis from HCCs, compared to their relative controls.

GJA1 is upregulated in HCCs and hepatic cirrhosis. The expression of GJA1 was compared between HCCs and adjacent NTs (a), between hepatic cirrhosis and NTs (b), between pulmonary metastases from HCCs (m-HCC) and primary HCCs without metastasis (p-HCC) (c), and between HCCs with intrahepatic metastasis (M1) or with portal vein tumor thrombus metastases (M2) and their corresponding primary HCCs (P1 or P2) or primary HCCs without metastasis (P0) (d). GJA1, gap junction protein, alpha 1; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NS, not significant; NT, nontumor tissue; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs the control group.

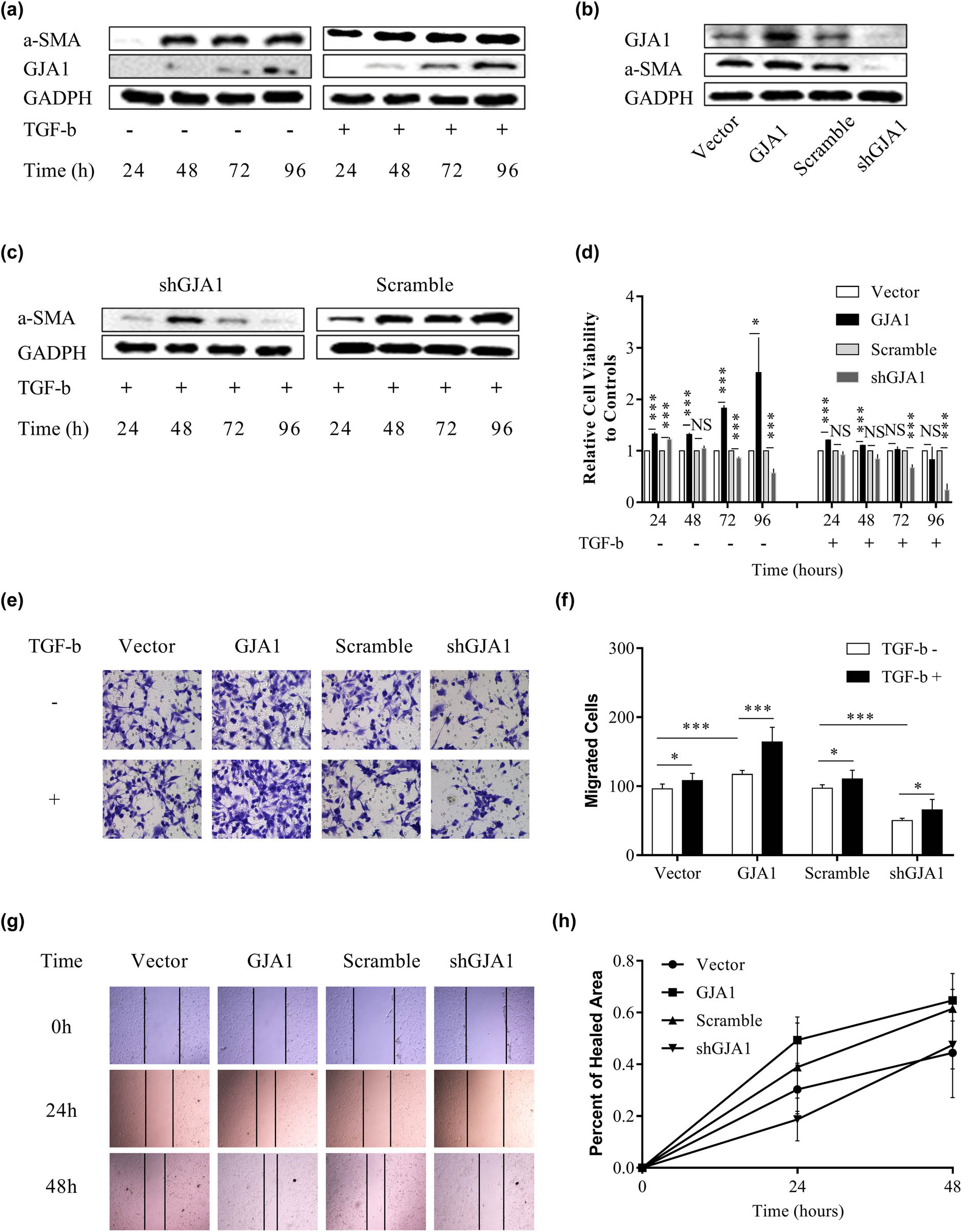

3.2 TGF-β-mediated HSC activation and migration are dependent on GJA1

HSC activation is the key contributing factor of hepatic cirrhosis and HCC progression, characterized by enhanced HSC proliferation, migration, contraction, and expression of specific markers such as alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) [7,42]. TGF-β, the most potent fibrogenic cytokine, promotes HSC activation and HCC progression [42,43]. We therefore investigated whether TGF-β-mediated HSC activation was dependent on GJA1. Figure 2a shows that HSCs became activated 48 h after resuscitation, which was accelerated by TGF-β1 stimulation and coincided with elevated GJA1 expression. Ectopic expression of GJA1 upregulated while knockdown of GJA1 downregulated α-SMA expression in HSCs (Figure 2b). In addition, knockdown of GJA1 significantly abrogated TGF-β1-induced α-SMA overexpression at 72 and 96 h (Figure 2c). We further evaluated whether GJA1 influenced HSC proliferation and migration. Figure 2d shows that overexpression of GJA1 significantly promoted HSC proliferation, which was most apparent at 72 and 96 h, while knockdown of GJA1 remarkably suppressed HSC proliferation at 72 and 96 h. Concurrent TGF-β1 treatment with GJA1 overexpression had no effects on HSC proliferation at 72 and 96 h, whereas concurrent TGF-β1 treatment with GJA1 knockdown further inhibited HSC proliferation at these time points. By contrast, overexpression of GJA1 accelerated and knockdown of GJA1 inhibited HSC migration, while concurrent TGF-β1 treatment increased the effects of GJA1 overexpression and neutralized the effects of GJA1 knockdown on HSC migration, as suggested by the Transwell migration assay (Figure 2e and f). Similarly, the wound healing assay also confirmed that GJA1 promoted the migration of HSCs (Figure 2g and h). Taken together, these results indicated that GJA1 was a potential downstream target of TGF-β that was necessary for TGF-β-induced HSC activation and migration but not proliferation.

TGF-β-mediated HSC activation and migration are dependent on GJA1. LX2 cells were stimulated with or without TGF-β for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, and cell lysates were collected and analyzed using western blotting with the indicated antibodies (a). Cell lysates were collected from LX2 stable infectants expressing GJA1, vector control, shGJA1, or scrambled control, followed by western blotting using the indicated antibodies (b). LX2 stable infectants expressing shGJA1 or scrambled control were stimulated with TGF-β for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, and cell lysates were collected and analyzed by western blotting with the indicated antibodies (c). LX2 stable infectants expressing GJA1, vector control, shGJA1, or scrambled control were seeded into 96-well plates and stimulated with or without TGF-β for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, followed by cholecystokinin octapeptide-8 assays (d). LX2 stable infectants expressing GJA1, vector control, shGJA1, or scrambled control were stimulated with or without TGF-β for 24 h and analyzed using the Transwell migration assay (e and f). LX2 stable infectants expressing GJA1, vector control, shGJA1, or scrambled control were seeded into 12-well plates and analyzed using the scratch wound-healing assay. Wound closure was photographed at 0, 24, and 48 h and quantitated (g and h). α-SMA, alpha smooth muscle actin; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; HSC, hepatic stellate cell; GJA1, gap junction protein, alpha 1.

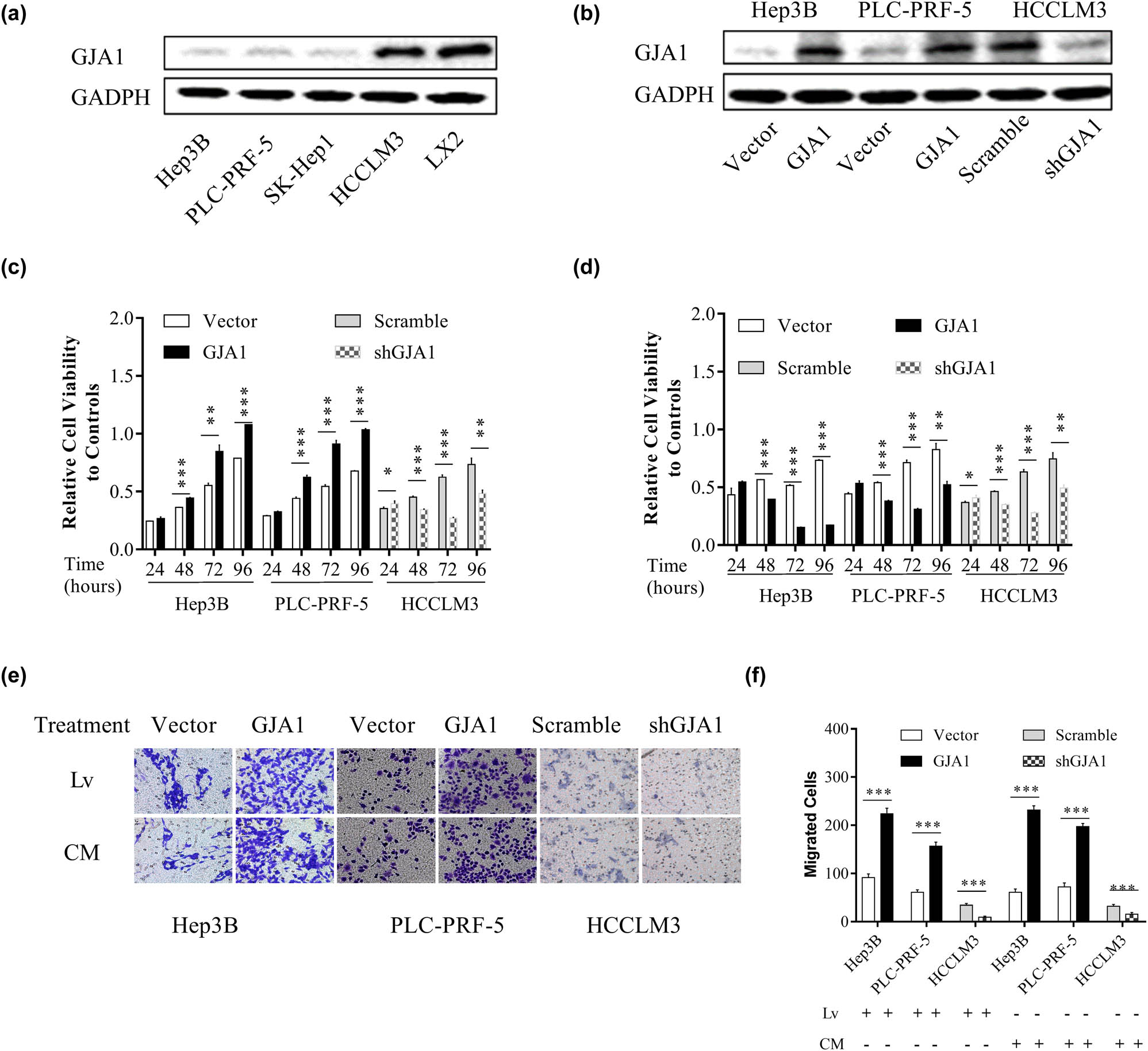

3.3 GJA1 differentially affects the proliferation and migration of cultured HCC cells

To further characterize the role of GJA1 in HCC progression, we evaluated the effects of GJA1 on the proliferation and migration of cultured HCC cells. We first assessed the abundance of GJA1 in four HCC cell lines with different malignant potencies and LX2. Figure 3a shows that GJA1 was significantly downregulated in Hep3B, PLC-PRF-5, and SK-Hep1 cells that had low to moderate malignant potencies, compared to that in LX2 cells and HCCLM3 cells that were derived from MHCC97-H cells and had a high tendency for pulmonary metastasis. We then overexpressed GJA1 in Hep3B and PLC-PRF-5 cells and knocked down GJA1 in HCCLM3 cells (Figure 3b). GJA1 overexpression significantly increased the proliferation of HEP3B and PLC-PRF-5 cells, while GJA1 knockdown significantly decreased the proliferation of HCCLM3 cells, from 48 to 96 h (Figure 3c). Culturing with the corresponding CM from HSCs yielded similar results in HCCLM3 cells but opposite results in HEP3B and PLC-PRF-5 cells, compared to that in lentivirus-transduced cells (Figure 3d). GJA1 overexpression significantly accelerated the migration of HEP3B and PLC-PRF-5 cells, and GJA1 knockdown significantly impeded the migration of HCCLM3 cells, while cultivation with the corresponding CM from HSCs yielded similar results in these cells compared with that in lentivirus-transduced cells (Figure 3e and f). Collectively, these results suggested that the activity of GJA1 was cell type-dependent.

GJA1 differentially affects the proliferation and migration of cultured HCC cells. The intrinsic expression of GJA1 in cultured HCC cells and HSCs was analyzed by western blotting (a). HEP3B and PLC-PRF-5 cells with low to moderate malignant potencies were transduced with lentiviruses carrying GJA1 or vector control, while HCCLM3 cells with a high tendency for pulmonary metastasis were transduced with shGJA1 or scrambled control. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting (b). HCC cells transduced with lentiviruses expressing GJA1, vector control, shGJA1, or scramble control were seeded into 96-well plates and analyzed using the cholecystokinin octapeptide-8 assay (c). HCC cells stimulated with conditioned medium from HSCs transduced with the indicated lentiviruses were seeded into 96-well plates and analyzed using the cholecystokinin octapeptide-8 assay (d). HCC cells transduced with the indicated lentiviruses or stimulated with CM from HSCs transduced with indicated lentiviruses were analyzed using the Transwell migration assay (e and f). CM, conditioned medium; GJA1, gap junction protein, alpha 1; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HSC, hepatic stellate cell; Lv, lentiviruses.

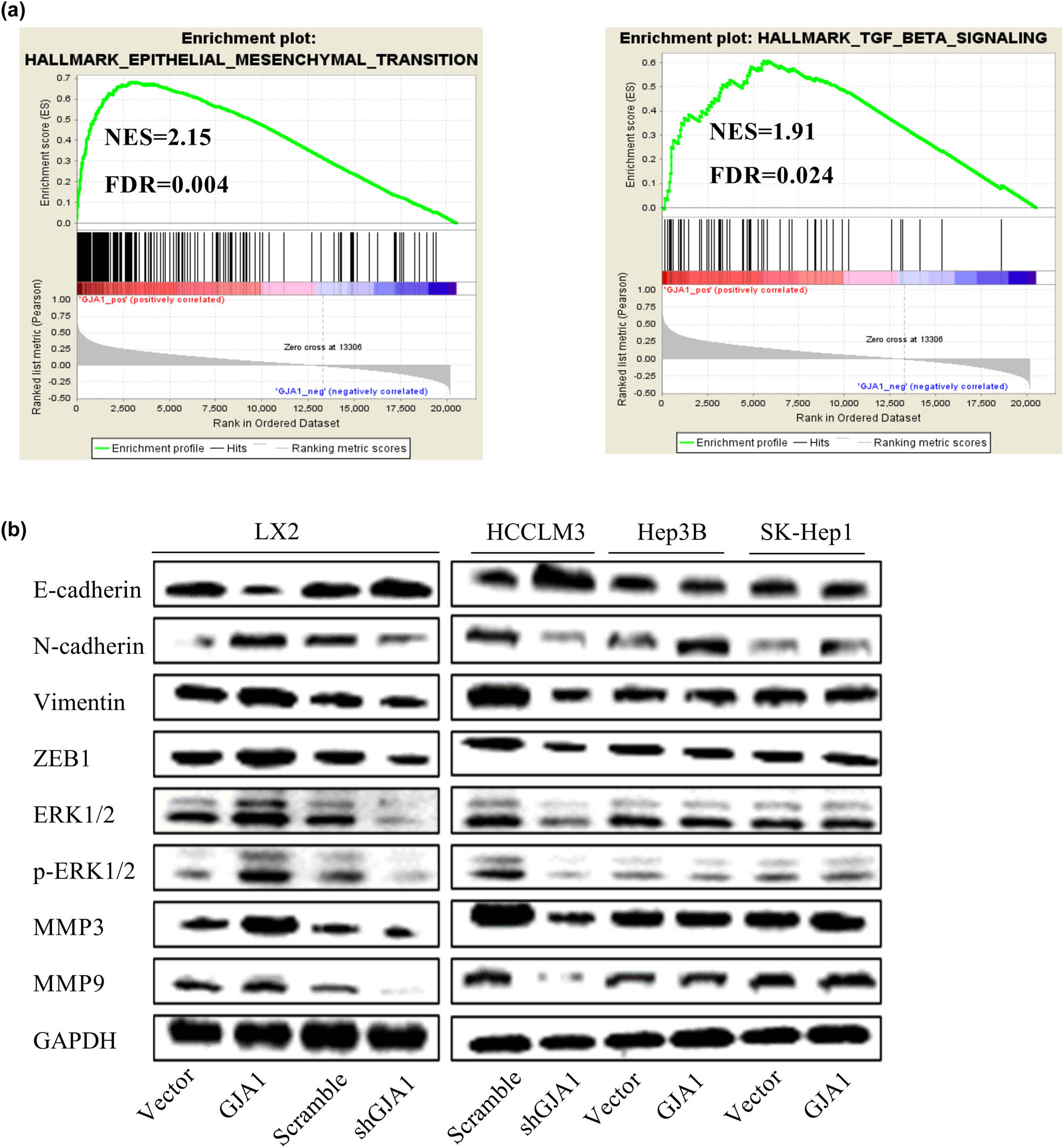

3.4 GJA1 induces the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)

To characterize the potential underlying mechanism of GJA1 activity, we first performed a GSEA using the TCGA-LIHC dataset. We found that high GJA1 expression was positively correlated with the hallmark gene sets EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION and TGF_BETA_SIGNALING (Figure 4a) as well as several other gene sets that were closely associated with tumor progression (data not shown). To verify these observations, we tested the effects of GJA1 on several EMT markers and EMT-related transcription factors in LX2, HCCLM3, PLC-PRF-5, and HEP3B cells transduced with the indicated lentiviruses. As the ERK1/2 pathway and MMPs are critically involved in TGF-β-mediated EMT [44,45], we also tested the effects of GJA1 on key molecules in these pathways. Western blot analysis showed that GJA1 overexpression in HSCs decreased the epithelial marker E-cadherin, increased the mesenchymal markers N-cadherin, vimentin, and Zeb1, activated the ERK1/2-MAPK signaling pathway, and increased MMP-3 and MMP-9 compared to control cells. GJA1 knockdown in HSCs and HCCLM3 cells increased E-cadherin, decreased N-cadherin, vimentin, and Zeb1, inhibited the ERK1/2-MAPK signaling pathway, and decreased MMP-3 and MMP-9 compared to control cells. By contrast, GJA1 overexpression in PLC-PRF-5 and HEP3B cells had no consistent effects on these markers (Figure 4b). Overall, these results suggested that GJA1 promoted HCC progression by inducing the EMT in both HSCs and highly aggressive HCC cells.

GJA1 induces the EMT. A GSEA indicated that GJA1 expression was positively correlated with the hallmark gene sets EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION (a, left) and TGF_BETA_SIGNALING (a, right). Cell lysates were collected from LX2 stable infectants expressing GJA1, vector control, shGJA1, or scrambled control cells, followed by western blot analyses with the indicated antibodies (b, left panel). HEP3B and PLC-PRF-5 cells were transduced with lentiviruses carrying GJA1 or vector control, while HCCLM3 cells were transduced with shGJA1 or the scrambled control. Cell lysates were collected and were analyzed using western blotting with the indicated antibodies (b, right panel). EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; ERK, extracellular regulated protein kinases; FDR, false discovery rate; GJA1, gap junction protein, alpha 1; GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; NES, normalized enrichment score; ZEB1, zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1.

4 Discussion

GJA1 is one of the specific proteins expressed by activated HSCs and is positively associated with HCC recurrence and unfavorable prognoses [5]. GJA1 also mediates hepatic cirrhosis and metastasis of several malignancies [15,46]. Consistent with these observations, the present study showed that GJA1 was almost always overexpressed in HCCs and hepatic cirrhosis, compared to corresponding NTs. In addition, GJA1 expression was significantly increased in lung metastases from HCCs and HCCLM3 cells that had a high propensity for lung metastasis, compared to HCCs without metastasis and HCC cells with less malignant potentials, which is highly consistent with observations made by Ogawa et al. using a rat model of HCC [47]. Furthermore, the overexpression of GJA1 promoted, while knockdown of GJA1 inhibited, the proliferation and migration of cultured HCC cells. Unexpectedly, we found that GJA1 expression was decreased significantly in portal vein tumor thrombus metastases, while it was decreased with no significance in intrahepatic metastases compared to that in corresponding primary HCCs. As primary tumor lesions and their matched distant metastases share large similarities at the genomic and transcriptomic levels, the metastatic propensity of the primary tumor has been suggested as “inherent” [37]; thus, the enhanced GJA1 expression in primary tumors could indicate a high propensity of pulmonary metastasis. To our surprise, CM from HSCs overexpressing GJA1 differentially influenced the proliferation and migration of HCC cells with relatively lower malignant potency. Although CM from activated HSCs generally promotes HCC progression [48,49,50], conflicting results were occasionally reported in the literature [51,52]. Besides, Coulouar et al. identified the bidirectional crosstalk between HSCs and HCC cells, which induced HCC cell migration rather than proliferation, and generation of the proangiogenic microenvironment in HSC-LX2 cells [8]. Thus the inconsistency observed in Hep3B and PLC-PRF-5 cells may be ascribed to different pathways mediating proliferation and migration of HCC cells that are targeted by proteins secreted by GJA1-overexpressing HSCs. Together, these results suggested that the roles of GJA1 were tumor-type and cell type-dependent, and could partly explain the discrepancy in previous reports that GJA1 had contrasting effects on tumor progression.

Among various profibrotic factors, TGF-β is generally considered the most potent. Binding of TGF-β to the type I receptor induces phosphorylation of the receptor, subsequently resulting in phosphorylation and activation of the factor, and small molecules targeted against decapentaplegic-3, followed by enhanced transcription of type I and type III collagen [42]. TGF-β also promotes HSC activation by activating the MAPK signaling pathway, including extracellular signal-regulated kinase, p38, and c-jun N-terminal kinase [42]. In the present study, we found that GJA1 was upregulated by TGF-β1 in cultured and activated human HSCs, and its presence was necessary for TGF-β1-induced HSC activation and migration, but not for TGF-β1-mediated proliferation inhibition. However, conflicting reports from previous studies have suggested that the regulation of GJA1 by TGF-β is highly diversified. For example, TGF-β upregulated GJA1 expression in human granulosa cells and ovarian cancer cells [53,54] but downregulated GJA1 expression in rat HSCs [55]. This may partly be explained by the observation that GJA1-mediated GJIC was organ-specific and only existed between neighboring HSCs but not between HSCs and other cell types in the liver [13], and that the plasma membrane localization of GJA1 was functional, promoting disease metastases, while the cytoplasmic localization was not functional, accompanied by reduced cell proliferation, adhesion, and invasion [46]. Besides, the identification of N-terminally truncated GJA1 isoforms may further complicate this case, as the most predominant one GJA1 20k regulates GJA1 gap junction formation and inhibition of this isoform leads to redistribution and malfunction of GJA1 [56]. In addition, being one of the specific genes expressed by activated HSCs [5], GJA1 promoted HSC activation in return, which suggests positive feedback between HSC activation and GJA1 overexpression that leads to augmented GJIC between HSCs. These observations underline the complicacy and importance of GJA1 in mediating tumor progression and need to be addressed in future studies.

In the current study, the GSEA results showed that high GJA1 expression was positively correlated with the hallmark gene sets EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_ TRANSITION and TGF_BETA_SIGNALING as well as several other tumor-related gene sets, providing further evidence that GJA1 is closely associated with tumor progression in HCCs. The EMT is one of the key processes mediating cirrhosis and tumor metastasis and has been classified into three different biological subtypes based on its biological context. Type 1 EMTs generate primary mesenchymal cells and are related to implantation, embryo formation, and organ development. Type 2 EMTs are involved in wound healing, tissue regeneration, and organ fibrosis. Type 3 EMTs occur in neoplastic cells and induce cancer invasion and metastasis [45]. TGF-β induces the EMT in both fibrosis and cancer and has been suggested as a target to reverse the EMT [44]. Our results showed that GJA1 induced the EMT in LX2 and HCCLM3 cells but not in PLC-PRF-5 or HEP3B cells, which may contribute to its functional complexity in HCC progression. Stimulated by TGF-β, normal mouse mammary gland epithelial cells undergo EMT with increased expression of full-length GJA1 but reduced expression of GJA1 20k and gap junction formation [56]. However, as enhanced gap junction formation may be associated with increased HSC activation, these observations once again demonstrate the tumor-type and cell type-dependent roles of GJA1.

The current study presents some findings that are clinically and scientifically meaningful, which may help better understand the critical involvement of GJA1 in hepatic fibrosis and HCC metastasis; however, there are some inherent limitations, including but not limited to the following. First, the pooled analyses of different datasets would bring great heterogeneity because of the largely variable background, which should be taken into consideration before any conclusions can be drawn. Second, we did not confirm the in vivo tumor-promoting activity of GJA1 using metastatic xenograft models since the cell lines we used failed to derive lung metastasis, maybe due to the short observation period. Third, although we uncovered the potential regulation of GJA1 on EMT of HSCs and HCC cells, we did not further elaborate on the underlying mechanism in the current study. Last, the transcriptional changes of GJA1 observed in different metastases from HCCs were only based on limited sample numbers, which should be validated in larger patient cohorts. These limitations should be addressed in future studies.

5 Conclusion

In summary, we have identified GJA1 as a potential downstream target of TGF-β that may promote HCC progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the EMT of HSCs.

Abbreviations

- CM

-

conditioned medium

- Cx43

-

connexin 43

- EMT

-

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- GJA1

-

gap junction protein, alpha 1

- GJIC

-

gap junctional intercellular communication

- GSEA

-

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- HCC

-

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HSC

-

hepatic stellate cell

- LIHC

-

the Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma Project

- NT

-

normal tissue

- PBS

-

phosphate-buffered saline

- q-PCR

-

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- SMA

-

α-smooth muscle actin

- TCGA

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TGF

-

transforming growth factor

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the constructive suggestions from Professor He Meng from Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by Shanghai Fifth People’s Hospital (grant numbers 2016WYRC01, 2017WYRCSG01); the Medical System of Shanghai Minhang District (grant number 2017MWDXK01); the Shanghai Minhang District Health and Family Planning Commission (grant number 2016MW03); Shanghai Minhang District Science and Technology Commission (grant number 2019MHZ054); and the Shanghai Minhang District Science and Technology Commission (grant number 2017MHZ02). The funding sources were not involved in the study design; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

-

Author contributions: Ke CW designed the study. Niu GM, Wang X, Zhang XT, Ren J, Song T, Hu ZQ, Chen L, Xia J, Hong L, Yang XM, and Hong RQ performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Wang X and Niu GM wrote the manuscript. Ke CW, Hong L, and Ren J helped to revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within this article and its additional images. Raw data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Appendix

Antibody information datasheet*

| Protein ID | Species | Purification | Cat. no. | Producer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vimentin | Rabbit | mAb | abs130228 | Absin Biotechnology, Shanghai, China |

| MMP3 | Rabbit | mAb | 14351S | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| MMP9 | Rabbit | mAb | 13667 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| ERK1/2 | Rabbit | mAb | 4695 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| p-ERK1/2 | Rabbit | mAb | 4376 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| E-cadherin | Rabbit | mAb | 3195 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| N-cadherin | Rabbit | mAb | 13116 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

| Zeb1 | Rabbit | mAb | 3396 | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA |

*All antibodies were diluted at 1:1,000.

References

[1] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[2] Chang MH, Chen CJ, Lai MS, Hsu HM, Wu TC, Kong MS, et al. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children. Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(26):1855–9. 10.1056/NEJM199706263362602.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. 10.3322/caac.21654.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Zhang DY, Goossens N, Guo J, Tsai MC, Chou HI, Altunkaynak C, et al. A hepatic stellate cell gene expression signature associated with outcomes in hepatitis C cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Gut. 2016;65(10):1754–64. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309655.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Ji J, Eggert T, Budhu A, Forgues M, Takai A, Dang H, et al. Hepatic stellate cell and monocyte interaction contributes to poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;62(2):481–95. 10.1002/hep.27822.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Dou C, Liu Z, Tu K, Zhang H, Chen C, Yaqoob U, et al. P300 acetyltransferase mediates stiffness-induced activation of hepatic stellate cells into tumor-promoting myofibroblasts. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(8):2209–21.e14. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.02.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Thompson AI, Conroy KP, Henderson NC. Hepatic stellate cells: central modulators of hepatic carcinogenesis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:63. 10.1186/s12876-015-0291-5.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Coulouarn C, Corlu A, Glaise D, Guenon I, Thorgeirsson SS, Clement B. Hepatocyte-stellate cell cross-talk in the liver engenders a permissive inflammatory microenvironment that drives progression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72(10):2533–42. 10.1158/0008-5472.Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Mikuriya Y, Tashiro H, Kuroda S, Nambu J, Kobayashi T, Amano H, et al. Fatty liver creates a pro-metastatic microenvironment for hepatocellular carcinoma through activation of hepatic stellate cells. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(4):E3–13. 10.1002/ijc.29096.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Coulouarn C, Clement B. Stellate cells and the development of liver cancer: therapeutic potential of targeting the stroma. J Hepatol. 2014;60(6):1306–9. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Faggioli F, Palagano E, Di Tommaso L, Donadon M, Marrella V, Recordati C, et al. B lymphocytes limit senescence-driven fibrosis resolution and favor hepatocarcinogenesis in mouse liver injury. Hepatology. 2018;67(5):1970–85. 10.1002/hep.29636.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Evans WH. Cell communication across gap junctions: a historical perspective and current developments. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43(3):450–9. 10.1042/BST20150056.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Fischer R, Reinehr R, Lu TP, Schonicke A, Warskulat U, Dienes HP, et al. Intercellular communication via gap junctions in activated rat hepatic stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(2):433–48. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.065.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Zhang D, Kaneda M, Nakahama K, Arii S, Morita I. Connexin 43 expression promotes malignancy of HuH7 hepatocellular carcinoma cells via the inhibition of cell-cell communication. Cancer Lett. 2007;252(2):208–15. 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.12.024.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Balasubramaniyan V, Dhar DK, Warner AE, Vivien Li WY, Amiri AF, Bright B, et al. Importance of Connexin-43 based gap junction in cirrhosis and acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2013;58(6):1194–200. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.01.023.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Cogliati B, Da Silva TC, Aloia TP, Chaible LM, Real-Lima MA, Sanches DS, et al. Morphological and molecular pathology of CCL4-induced hepatic fibrosis in connexin43-deficient mice. Microsc Res Tech. 2011;74(5):421–9. 10.1002/jemt.20926.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Naus CC, Laird DW. Implications and challenges of connexin connections to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(6):435–41. 10.1038/nrc2841.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[18] Wang ZS, Wu LQ, Yi X, Geng C, Li YJ, Yao RY. Connexin-43 can delay early recurrence and metastasis in patients with hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma and low serum alpha-fetoprotein after radical hepatectomy. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:306. 10.1186/1471-2407-13-306.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Wurmbach E, Chen YB, Khitrov G, Zhang W, Roayaie S, Schwartz M, et al. Genome-wide molecular profiles of HCV-induced dysplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;45(4):938–47. 10.1002/hep.21622.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Hoshida Y, Villanueva A, Kobayashi M, Peix J, Chiang DY, Camargo A, et al. Gene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(19):1995–04. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804525.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Mas VR, Maluf DG, Archer KJ, Yanek K, Kong X, Kulik L, et al. Genes involved in viral carcinogenesis and tumor initiation in hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Med. 2009;15(3–4):85–94. 10.2119/molmed.2008.00110.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Roessler S, Jia HL, Budhu A, Forgues M, Ye QH, Lee JS, et al. A unique metastasis gene signature enables prediction of tumor relapse in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70(24):10202–12. 10.1158/0008-5472.Suche in Google Scholar

[23] Roessler S, Long EL, Budhu A, Chen Y, Zhao X, Ji J, et al. Integrative genomic identification of genes on 8p associated with hepatocellular carcinoma progression and patient survival. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(4):957–66.e12. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.039.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Burchard J, Zhang C, Liu AM, Poon RT, Lee NP, Wong KF, et al. microRNA-122 as a regulator of mitochondrial metabolic gene network in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:402. 10.1038/msb.2010.58.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Liu AM, Yao TJ, Wang W, Wong KF, Lee NP, Fan ST, et al. Circulating miR-15b and miR-130b in serum as potential markers for detecting hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(2):e000825. 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000825.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Tung EK, Mak CK, Fatima S, Lo RC, Zhao H, Zhang C, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic significance of serum and tissue Dickkopf-1 levels in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2011;31(10):1494–504. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02597.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Lamb JR, Zhang C, Xie T, Wang K, Zhang B, Hao K, et al. Predictive genes in adjacent normal tissue are preferentially altered by sCNV during tumorigenesis in liver cancer and may rate limiting. PloS One. 2011;6(7):e20090. 10.1371/journal.pone.0020090.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Sung WK, Zheng H, Li S, Chen R, Liu X, Li Y, et al. Genome-wide survey of recurrent HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44(7):765–9. 10.1038/ng.2295.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Lim HY, Sohn I, Deng S, Lee J, Jung SH, Mao M, et al. Prediction of disease-free survival in hepatocellular carcinoma by gene expression profiling. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(12):3747–53. 10.1245/s10434-013-3070-y.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Kojima K, April C, Canasto-Chibuque C, Chen X, Deshmukh M, Venkatesh A, et al. Transcriptome profiling of archived sectioned formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (AS-FFPE) tissue for disease classification. PloS One. 2014;9(1):e86961. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086961.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Villa E, Critelli R, Lei B, Marzocchi G, Camma C, Giannelli G, et al. Neoangiogenesis-related genes are hallmarks of fast-growing hepatocellular carcinomas and worst survival. Results from a prospective study. Gut. 2016;65(5):861–9. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308483.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Villanueva A, Portela A, Sayols S, Battiston C, Hoshida Y, Mendez-Gonzalez J, et al. DNA methylation-based prognosis and epidrivers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;61(6):1945–56. 10.1002/hep.27732.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Grinchuk OV, Yenamandra SP, Iyer R, Singh M, Lee HK, Lim KH, et al. Tumor-adjacent tissue co-expression profile analysis reveals pro-oncogenic ribosomal gene signature for prognosis of resectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Oncol. 2018;12(1):89–113. 10.1002/1878-0261.12153.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Zhang J, Baran J, Cros A, Guberman JM, Haider S, Hsu J, et al. International Cancer Genome Consortium Data Portal--a one-stop shop for cancer genomics data. Database (Oxford). 2011;2011:bar026. 10.1093/database/bar026.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets – update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(D1):D991–5. 10.1093/nar/gks1193.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Lian Q, Wang S, Zhang G, Wang D, Luo G, Tang J, et al. HCCDB: a database of hepatocellular carcinoma expression atlas. Genom Proteom Bioinform. 2018;16(4):269–75. 10.1016/j.gpb.2018.07.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Roessler S, Lin G, Forgues M, Budhu A, Hoover S, Simpson RM, et al. Integrative genomic and transcriptomic characterization of matched primary and metastatic liver and colorectal carcinoma. Int J Bio Sci. 2015;11(1):88–98. 10.7150/ijbs.10583.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Ye QH, Qin LX, Forgues M, He P, Kim JW, Peng AC, et al. Predicting hepatitis B virus-positive metastatic hepatocellular carcinomas using gene expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2003;9(4):416–23. 10.1038/nm843.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Liao R, Wu H, Yi Y, Wang JX, Cai XY, He HW, et al. Clinical significance and gene expression study of human hepatic stellate cells in HBV related-hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2013;32:22. 10.1186/1756-9966-32-22.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Zhao S, Zhou L, Niu G, Li Y, Zhao D, Zeng H. Differential regulation of orphan nuclear receptor TR3 transcript variants by novel vascular growth factor signaling pathways. FASEB J. 2014;28(10):4524–33. 10.1096/fj.13-248401.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Niu G, Ye T, Qin L, Bourbon PM, Chang C, Zhao S, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor TR3/Nur77 improves wound healing by upregulating the expression of integrin beta4. FASEB J. 2015;29(1):131–40. 10.1096/fj.14-257550.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Tsuchida T, Friedman SL. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(7):397–411. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.38.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Peng L, Yuan XQ, Zhang CY, Ye F, Zhou HF, Li WL, et al. High TGF-beta1 expression predicts poor disease prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(21):34387–97. 10.18632/oncotarget.16166.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Zavadil J, Bottinger EP. TGF-beta and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions. Oncogene. 2005;24(37):5764–74. 10.1038/sj.onc.1208927.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(6):1420–8. 10.1172/JCI39104.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Lamiche C, Clarhaut J, Strale PO, Crespin S, Pedretti N, Bernard FX, et al. The gap junction protein Cx43 is involved in the bone-targeted metastatic behaviour of human prostate cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29(2):111–22. 10.1007/s10585-011-9434-4.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Ogawa K, Pitchakarn P, Suzuki S, Chewonarin T, Tang M, Takahashi S, et al. Silencing of connexin 43 suppresses invasion, migration and lung metastasis of rat hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(5):860–7. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02228.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[48] Imai Y, Yoshida O, Watanabe T, Yukimoto A, Koizumi Y, Ikeda Y, et al. Stimulated hepatic stellate cell promotes progression of hepatocellular carcinoma due to protein kinase R activation. PloS one. 2019;14(2):e0212589. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212589.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[49] Lv X, Fang C, Yin R, Qiao B, Shang R, Wang J, et al. Agrin para-secreted by PDGF-activated human hepatic stellate cells promotes hepatocarcinogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget. 2017;8(62):105340–55. 10.18632/oncotarget.22186.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Xie YX, Liao R, Pan L, Du CY. ERK pathway activation contributes to the tumor-promoting effects of hepatic stellate cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunol Lett. 2017;188:116–23. 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.06.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[51] Rawal P, Siddiqui H, Hassan M, Choudhary MC, Tripathi DM, Nain V, et al. Endothelial cell-derived TGF-beta promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition via CD133 in HBx-infected hepatoma cells. Front Oncol. 2019;9:308. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00308.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[52] Liu WT, Jing YY, Yu GF, Chen H, Han ZP, Yu DD, et al. Hepatic stellate cell promoted hepatoma cell invasion via the HGF/c-Met signaling pathway regulated by p53. Cell Cycle. 2016;15(7):886–94. 10.1080/15384101.2016.1152428.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[53] Chen YC, Chang HM, Cheng JC, Tsai HD, Wu CH, Leung PC. Transforming growth factor-beta1 up-regulates connexin43 expression in human granulosa cells. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(9):2190–1. 10.1093/humrep/dev175.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Qiu X, Cheng JC, Zhao J, Chang HM, Leung PC. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates human ovarian cancer cell migration by up-regulating connexin43 expression via Smad2/3 signaling. Cell Signal. 2015;27(10):1956–62. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.07.010.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[55] Lim MC, Maubach G, Zhuo L. TGF-beta1 down-regulates connexin 43 expression and gap junction intercellular communication in rat hepatic stellate cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 2009;88(12):719–30. 10.1016/j.ejcb.2009.08.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[56] James CC, Zeitz MJ, Calhoun PJ, Lamouille S, Smyth JW. Altered translation initiation of GJA1 limits gap junction formation during epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Mol Biol Cell. 2018;29(7):797–808. 10.1091/mbc.E17-06-0406.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2021 Gengming Niu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells

- Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 in healthy paediatric population

- Algorithm of rational approach to reconstruction in Fournier’s disease

- A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury

- Src-1 and SP2 promote the proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Dexmedetomidine may decrease the bupivacaine toxicity to heart

- Hypoxia stimulates the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma via up-regulating the NUSAP1 expression

- Long noncoding RNA XIST knockdown relieves the injury of microglia cells after spinal cord injury by sponging miR-219-5p

- External fixation via the anterior inferior iliac spine for proximal femoral fractures in young patients

- miR-128-3p reduced acute lung injury induced by sepsis via targeting PEL12

- HAGLR promotes neuron differentiation through the miR-130a-3p-MeCP2 axis

- Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 is elevated in serum of patients with heart failure and correlates with the disease severity and patient’s prognosis

- Cell population data in identifying active tuberculosis and community-acquired pneumonia

- Prognostic value of microRNA-4521 in non-small cell lung cancer and its regulatory effect on tumor progression

- Mean platelet volume and red blood cell distribution width is associated with prognosis in premature neonates with sepsis

- 3D-printed porous scaffold promotes osteogenic differentiation of hADMSCs

- Association of gene polymorphisms with women urinary incontinence

- Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels of urologic patients

- miR-496 inhibits proliferation via LYN and AKT pathway in gastric cancer

- miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development

- Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- Fluorescent light energy modulates healing in skin grafted mouse model

- Silencing CDK6-AS1 inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory damage in HK-2 cells

- Predictive effect of DCE-MRI and DWI in brain metastases from NSCLC

- Severe postoperative hyperbilirubinemia in congenital heart disease

- Baicalin improves podocyte injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

- Clinical factors predicting ureteral stent failure in patients with external ureteral compression

- Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway

- Triple-Endobutton and clavicular hook: A propensity score matching analysis

- Long noncoding RNA MIAT inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy and the activation of NF-κB pathway in high glucose-treated renal tubular epithelial cells by the miR-182-5p/GPRC5A axis

- Serum exosomal miR-122-5p, GAS, and PGR in the non-invasive diagnosis of CAG

- miR-513b-5p inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells by targeting TRIB1

- Fer exacerbates renal fibrosis and can be targeted by miR-29c-3p

- The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-92a in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prognostic value of α2δ1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study

- No significant benefit of moderate-dose vitamin C on severe COVID-19 cases

- circ_0000467 promotes the proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating KLF12 expression by sponging miR-4766-5p

- Downregulation of RAB7 and Caveolin-1 increases MMP-2 activity in renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxic conditions

- Educational program for orthopedic surgeons’ influences for osteoporosis

- Expression and function analysis of CRABP2 and FABP5, and their ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

- lncRNA-ZFAS1 promotes the progression of endometrial carcinoma by targeting miR-34b to regulate VEGFA expression

- Anticoagulation is the answer in treating noncritical COVID-19 patients

- Effect of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis on PFS after haplo-PBSCT

- Comparison of Dako HercepTest and Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2 (4B5) tests and their correlation with silver in situ hybridization in lung adenocarcinoma

- VSTM1 regulates monocyte/macrophage function via the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Comparison of vaginal birth outcomes in midwifery-led versus physician-led setting: A propensity score-matched analysis

- Treatment of osteoporosis with teriparatide: The Slovenian experience

- New targets of morphine postconditioning protection of the myocardium in ischemia/reperfusion injury: Involvement of HSP90/Akt and C5a/NF-κB

- Superenhancer–transcription factor regulatory network in malignant tumors

- β-Cell function is associated with osteosarcopenia in middle-aged and older nonobese patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study

- Clinical features of atypical tuberculosis mimicking bacterial pneumonia

- Proteoglycan-depleted regions of annular injury promote nerve ingrowth in a rabbit disc degeneration model

- Effect of electromagnetic field on abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- miR-150-5p affects AS plaque with ASMC proliferation and migration by STAT1

- MALAT1 promotes malignant pleural mesothelioma by sponging miR-141-3p

- Effects of remifentanil and propofol on distant organ lung injury in an ischemia–reperfusion model

- miR-654-5p promotes gastric cancer progression via the GPRIN1/NF-κB pathway

- Identification of LIG1 and LIG3 as prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer

- MitoQ inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis by enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy

- Dissecting role of founder mutation p.V727M in GNE in Indian HIBM cohort

- circATP2A2 promotes osteosarcoma progression by upregulating MYH9

- Prognostic role of oxytocin receptor in colon adenocarcinoma

- Review Articles

- The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Efficacy and safety of therapeutic plasma exchange in stiff person syndrome

- Role of cesarean section in the development of neonatal gut microbiota: A systematic review

- Small cell lung cancer transformation during antitumor therapies: A systematic review

- Research progress of gut microbiota and frailty syndrome

- Recommendations for outpatient activity in COVID-19 pandemic

- Rapid Communication

- Disparity in clinical characteristics between 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia and leptospirosis

- Use of microspheres in embolization for unruptured renal angiomyolipomas

- COVID-19 cases with delayed absorption of lung lesion

- A triple combination of treatments on moderate COVID-19

- Social networks and eating disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Letter

- COVID-19, WHO guidelines, pedagogy, and respite

- Inflammatory factors in alveolar lavage fluid from severe COVID-19 pneumonia: PCT and IL-6 in epithelial lining fluid

- COVID-19: Lessons from Norway tragedy must be considered in vaccine rollout planning in least developed/developing countries

- What is the role of plasma cell in the lamina propria of terminal ileum in Good’s syndrome patient?

- Case Report

- Rivaroxaban triggered multifocal intratumoral hemorrhage of the cabozantinib-treated diffuse brain metastases: A case report and review of literature

- CTU findings of duplex kidney in kidney: A rare duplicated renal malformation

- Synchronous primary malignancy of colon cancer and mantle cell lymphoma: A case report

- Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography and pathologic characters of CD68 positive cell in primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: A case report and literature review

- Persistent SARS-CoV-2-positive over 4 months in a COVID-19 patient with CHB

- Pulmonary parenchymal involvement caused by Tropheryma whipplei

- Mediastinal mixed germ cell tumor: A case report and literature review

- Ovarian female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin – Case report

- Rare paratesticular aggressive angiomyxoma mimicking an epididymal tumor in an 82-year-old man: Case report

- Perimenopausal giant hydatidiform mole complicated with preeclampsia and hyperthyroidism: A case report and literature review

- Primary orbital ganglioneuroblastoma: A case report

- Primary aortic intimal sarcoma masquerading as intramural hematoma

- Sustained false-positive results for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M: A case report and literature review

- Peritoneal loose body presenting as a hepatic mass: A case report and review of the literature

- Chondroblastoma of mandibular condyle: Case report and literature review

- Trauma-induced complete pacemaker lead fracture 8 months prior to hospitalization: A case report

- Primary intradural extramedullary extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PIEES/PNET) of the thoracolumbar spine: A case report and literature review

- Computer-assisted preoperative planning of reduction of and osteosynthesis of scapular fracture: A case report

- High quality of 58-month life in lung cancer patient with brain metastases sequentially treated with gefitinib and osimertinib

- Rapid response of locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma to apatinib: A case report

- Retrieval of intrarenal coiled and ruptured guidewire by retrograde intrarenal surgery: A case report and literature review

- Usage of intermingled skin allografts and autografts in a senior patient with major burn injury

- Retraction

- Retraction on “Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappa B pathway”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part I

- An artificial immune system with bootstrap sampling for the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial cancers

- Breast cancer recurrence prediction with ensemble methods and cost-sensitive learning

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells