Abstract

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a highly prevalent disorder defined as a cluster of cardiometabolic risk factors including obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. It is believed that excessive cortisol secretion due to psychosocial stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation might be involved in the pathogenesis of MetS. We sought to explore the association between MetS and psychosocial risk factors, as well as cortisol concentration measured in different biological specimens including saliva, blood serum, and hair samples. The study was conducted on a sample of 163 young and middle-aged men who were divided into groups according to the presence of MetS. Hair cortisol concentration (HCC) was determined using high performance liquid chromatography with UV detection, while blood serum and salivary cortisol levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunoassay. Lipid metabolism biomarkers were determined using routine laboratory methods. Anthropometric and lifestyle characteristics, as well as self-reported psychosocial indicators, were also examined. Significantly higher HCC and lower social support level among participants with MetS compared with individuals without MetS were found. However, no significant differences in blood serum and salivary cortisol levels were observed between men with and without MetS. In conclusion, chronically elevated cortisol concentration might be a potential contributing factor to the development of MetS.

1 Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of metabolic abnormalities including abdominal obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertension, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and elevated triacylglycerol (TAG) concentration [1]. MetS is associated with a 5-fold increased risk for type 2 diabetes and two times higher risk for the development of cardiovascular diseases which are the leading cause of death worldwide [1,2]. It is estimated that about one quarter of the world population is affected with MetS. The cost of MetS including informal care provided by family and direct costs of medical care, as well as loss of potential economic activity, is in trillions [3]. Moreover, MetS has become increasingly prevalent among young and middle-aged adults living in economically developed countries [4]. Although the pathogenesis of MetS is not fully elucidated, it is likely that there is an interaction between metabolic, genetic, and environmental factors [5].

There is some evidence suggesting that long-term and intense stress or experience of extremely stressful life events (e.g., disaster) is associated with the elevated risk of MetS onset [6,7]. Stress-induced activation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system results in the production of cortisol, the main glucocorticoid in humans. Since chronically elevated cortisol concentration promotes abdominal obesity, hypertension, and hyperglycemia, it is believed that stress should be considered as an etiological factor of MetS [8,9,10]. However, the existing literature on the relationship between cortisol concentration and MetS is inconsistent. Some studies found positive association of cortisol concentration with the prevalence of MetS [11,12], while other papers reported no association [13,14] or even negative relationship between cortisol concentration and MetS [15]. Similarly, distinct findings on the association between stress-related psychosocial factors such as social support or work stress and MetS have been observed. Several studies have found significant association of lower social support level and higher work-related stress with the increased prevalence of MetS [16,17], while other large studies demonstrated no relationship [18] or gender-specific associations between these psychosocial indicators and MetS [19]. In the previous meta-analysis, significant associations between higher perceived stress level and the prevalence of individual MetS parameters (i.e., visceral obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension) were found. Interestingly, no relationship between the perceived stress and the presence of MetS diagnosis was detected [20]. Another systematic review and meta-analysis revealed the importance of the stress source and found that the strongest impact on the MetS risk is attributed to occupational stress, while general stress or stressful life events were not related to the increased prevalence of MetS [21].

The most common approach for the objective evaluation of stress level is measurement of cortisol concentration in blood serum or saliva samples [22]. The collection of saliva specimens is easily performed, noninvasive, painless, and relatively stress-free, while blood collection requires qualified medical personnel and venipuncture-induced stress might give falsely higher cortisol concentrations [23]. In addition, salivary cortisol concentration reflects the circulating level of free, biologically active fraction of hormone rather than total levels, which are confounded by the presence of high affinity binding proteins [24,25]. Nevertheless, both salivary and blood serum cortisol concentrations indicate acute or short-term changes in HPA axis activity. In the last decade, the analysis of cortisol in human scalp hair has received an increasing attention as a promising chronic stress biomarker since it represents long-term (1–3 months) HPA axis activity [23,24,26,27,28]. We hypothesize that the presence of conflicting results on the relationship between HPA axis activity and MetS might be caused by different biological matrices (i.e., saliva, blood serum or plasma, hair) used for the evaluation of cortisol concentration. Thus, the major objective of this study was to explore the associations between MetS and cortisol concentration measured in different biospecimens including blood serum, saliva, and hair samples in young and middle-aged men. Also, we aimed to analyze differences in subjectively evaluated psychosocial factors between men with and without MetS.

2 Methods

2.1 Study population and procedure

This cross-sectional study included 163 young and middle-aged (25–55 years) men, who were recruited consecutively from the database of the Outpatient Department of Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos. Individuals with mental and endocrine disorders were not involved in the study. Also, subjects were excluded if they used synthetic glucocorticoids during the previous 3 months. Data collection was implemented by appropriately trained general practitioner and nurses working at the Outpatient Department of Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos, a public tertiary healthcare institution in Lithuania. During the first visit in the healthcare institution, each enrolled individual filled out the psychosocial stress questionnaire validated in the LiVicordia study [29], as well as a questionnaire on sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics, including age, education level, monthly income, smoking status, physical activity, the presence of night shift work, and additional job. Also, Salivette® devices with the manufacturers’ instructions were given for each study participant and subjects were asked to obtain their saliva samples immediately after awakening on the day of the second visit to the healthcare institution. The second data collection stage was scheduled in the morning (at 8:00–9:00 h) within a week after the first stage. On the second visit, subjects delivered their saliva samples. Also, blood samples for biochemical analysis, hair samples for cortisol concentration measurement, as well as anthropometric data were obtained by trained personnel. All participants provided written informed consent, and this research followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki published in 1964 and its later amendments and also the study protocol was approved by the Lithuanian Bioethics Committee (No. 15820-15-807-319).

2.2 Psychosocial stress questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of four major parts including job strain, social support, personality, and depression. Job strain was evaluated as a combined effect of psychological demands at work and authority over decisions (demand/control). Social support score consisted of questions about social support at the work site and global social support with the two dimensions, emotional support and social integration. Personality score was calculated using instruments on coping, self-esteem, sense of coherence, hostility, immersion, and vital exhaustion ((coping + self-esteem + sense of coherence)/(hostility + immersion + vital exhaustion)). Depression was estimated using 13-item Beck depression inventory [30].

2.3 Biochemical analyses and MetS diagnosis

All blood samples were collected under fasting conditions and were analyzed in the Centre of Laboratory Medicine of Vilnius University Hospital Santaros Klinikos. Specifically, HDL-C, TAG, and glucose concentration in blood serum were determined using routine laboratory methods (Architect ci8200, Abbott, USA). Anthropometric assessment involved waist circumference (WC) and resting arterial blood pressure (systolic and diastolic) measures. MetS diagnosis was based according to the International Diabetes Federation consensus worldwide definition of the MetS [31]. MetS was diagnosed if an individual had central obesity (WC ≥ 94 cm) and any two of the following four factors: raised TAG concentration (≥1.7 mmol/L), reduced HDL-C concentration (<1.03 mmol/L) or specific treatment for these lipid abnormalities, increased arterial blood pressure (systolic BP ≥ 130 or diastolic BP ≥ 85 mm Hg) or treatment of previously diagnosed hypertension, elevated fasting plasma glucose concentration (≥5.6 mmol/L), or previously diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Arterial hypertension was diagnosed according to the guidelines of the International Society of Hypertension [32].

2.4 Analysis of stress biomarkers

2.4.1 Determination of cortisol concentration in saliva and blood serum samples

Saliva samples were collected using Salivette® devices (Sarstedt Co. Ltd., Rommelsdorf, Germany). Saliva samples were stored at −80°C. After thawing, samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 4,000 rpm. Fasting blood samples for cortisol measurement were collected into vacuum tubes (BD Vacutainer SST II Advance (Becton Dickinson, USA)) in the morning (between 7 and 8 am). After collection, blood samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 3,000 rpm. Blood serum samples were stored at −80°C until analysis. Cortisol concentration in blood serum and saliva samples were determined using commercial ELISA kits (LDN®, Nordhorn, Germany). The sensitivity of ELISA assay for the quantitative determination of cortisol in blood serum was 1.3 ng/mL, while the sensitivity of ELISA for the cortisol measurement in saliva was 0.019 ng/mL.

2.4.2 Determination of cortisol concentration in human hair

Hair cortisol concentration (HCC) was determined from the most proximal segment of 3 cm of scalp hair, representing approximately 3 months prior to sampling grown hair. The hair samples were stored at room temperature in envelopes until analysis. Samples were prepared using slightly modified methods published by Raul et al. [33] and de Palo et al. [34]. Hair samples were washed twice in 5 mL isopropanol. A 20–50 mg of each sample was finely cut with scissors into small fragments (∼1 mm long) to improve the efficiency of extraction and incubated in 1.5 mL of Sorenson’s buffer, pH 7.6, for 16 h at 40°C, in the presence of 10 ng of 6-α methylprednisolone as internal standard. Each sample then was transferred to solid-phase extraction Discovery DSC-18 column (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), which was previously equilibrated (3 mL MeOH followed by 1.5 mL of water). The subsequent steps were the following: washing with 0.5 mL of water followed by 0.5 mL of acetone/water (1:4, v/v), 0.25 mL of hexane, and elution with 1.5 mL of diethyl ether. The eluates were evaporated under a stream of nitrogen gas and resuspended with 100 μL of acetonitrile/water (1:1, v/v). Cortisol concentration was determined using Shimadzu Nexera X2 UHPLC system (Shimadzu Corp., Kyoto, Japan). A 10 μL of the extract was injected on the Zorbax Eclipse XDGB-C8 (5.0 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm; Agilent Technologies) column. The chromatographic isocratic separation was carried out with a binary mobile phase of acetonitrile and deionized water (2:3, v/v). The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. The UV absorbance was measured at 245 nm wavelength. The average retention time of the cortisol was 4.12 min. Data were collected and processed using the LabSolutions software (Shimadzu Corp.).

3 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with R version 3.6.0. Quantitative variables are presented as median (interquartile range) (IQR), while absolute and relative frequencies were calculated for categorical variables. Chi-square test was employed to compare the categorical variables between men with and without MetS, as well as to analyze the differences of MetS prevalence among study participants stratified into groups based on their HCC and social support level. The strength of association between categorical variables was evaluated by calculating contingency coefficient (C). Furthermore, Mann–Whitney U test was used for the comparison of continuous variables. Spearman’s rank coefficient was used to quantify the strength of the correlation between HCC and criteria of MetS. Binary simple and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate predictors of MetS. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05 for two-tailed testing.

4 Results

4.1 Sample characteristics

Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics of the study sample. Thirty eight (23.3%) of participants met the criteria of MetS. MetS patients were significantly older and less physically active during leisure time compared with participants without MetS. In contrast, there were no significant differences regarding education level, income, smoking status, physical activity at work, and the prevalence of night shift work or additional job between MetS patients and healthy men. The comparison of psychosocial stress indicators showed significantly lower social support level in MetS patients than in the group of participants without MetS. Regarding the objective psychosocial stress measures, only HCC median values differed significantly among MetS patients and healthy individuals.

Comparison of sociodemographic, lifestyle, psychosocial indicators, and stress biomarkers between individuals with and without MetS

| Characteristics | Individuals without MetS (n = 125) | MetS patients (n = 38) | χ 2, df = 1 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic and lifestyle indicators | ||||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 35 (18) | 42.5 (10) | 0.007 | |

| Education level (university graduates or those with higher education), n (%) | 119 (95.2) | 33 (91.7) | 0.66 | 0.416 |

| Income (higher than national average monthly wage), n (%) | 104 (83.2) | 32 (88.9) | 0.69 | 0.406 |

| Smoking status (current smoker), n (%) | 18 (14.5) | 9 (25.0) | 2.19 | 0.139 |

| Physical activity at work (physically active), n (%) | 35 (28.0) | 14 (38.9) | 1.57 | 0.211 |

| Recreational physical activity (physically active), n (%) | 109 (87.2) | 22 (62.9) | 10.69 | 9.520 × 10 −4 |

| Additional job, n (%) | 28 (22.4) | 11 (30.6) | 1.01 | 0.314 |

| Night shift work, n (%) | 18 (15.5) | 2 (4.5) | 2.05 | 0.250 |

| Psychosocial indicators | ||||

| Depression, median (IQR) | 2.00 (5) | 3.00 (4) | 0.804 | |

| Personality, median (IQR) | 0.51 (0.10) | 0.52 (0.10) | 0.901 | |

| Job strain, median (IQR) | 0.67 (0.21) | 0.72 (0.23) | 0.384 | |

| Social support, median (IQR) | 48.00 (10.0) | 46.50 (9.25) | 0.009 | |

| Stress biomarkers | ||||

| Hair cortisol concentration (ng/g), median (IQR) | 36.50 (98.26) | 85.73 (150.88) | 0.005 | |

| Morning salivary cortisol concentration (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 9.16 (6.78) | 11.09 (9.85) | 0.193 | |

| Cortisol concentration in blood serum (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 221.78 (94.29) | 200.62 (128.15) | 0.168 | |

Note: Statistically significant p-values (<0.05) are shown in bold font.

4.2 HCC, social support level, and MetS

Table 2 represents the correlation between HCC and distinct criteria of MetS. We found significant relationship between HCC and participants’ WC, resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure values, and fasting glucose concentration. However, there was no evidence for correlations between HCC and HDL-C or TAG concentration in serum samples. Correlation analysis also showed significant associations between subjectively perceived social support level and WC values, as well as fasting glucose concentration in blood serum (Table 3).

Correlations between HCC and criteria of metabolic syndrome

| Variable | Spearman’s r | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.21 | 0.007 |

| Resting systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 0.34 | 9.55 × 10 −6 |

| Resting diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 0.32 | 3.05 × 10 −5 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 0.16 | 0.046 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | −0.03 | 0.746 |

| Triacylglycerols (mmol/L) | 0.11 | 0.144 |

Note: Statistically significant p-values (<0.05) are shown in bold font.

Correlations between subjectively perceived social support level and criteria of metabolic syndrome

| Variable | Spearman’s r | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Waist circumference (cm) | −0.14 | 0.044 |

| Resting systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | −0.03 | 0.629 |

| Resting diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | −0.12 | 0.065 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | −0.14 | 0.040 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.10 | 0.139 |

| Triacylglycerols (mmol/L) | −0.04 | 0.557 |

Note: Statistically significant p-values (<0.05) are shown in bold font.

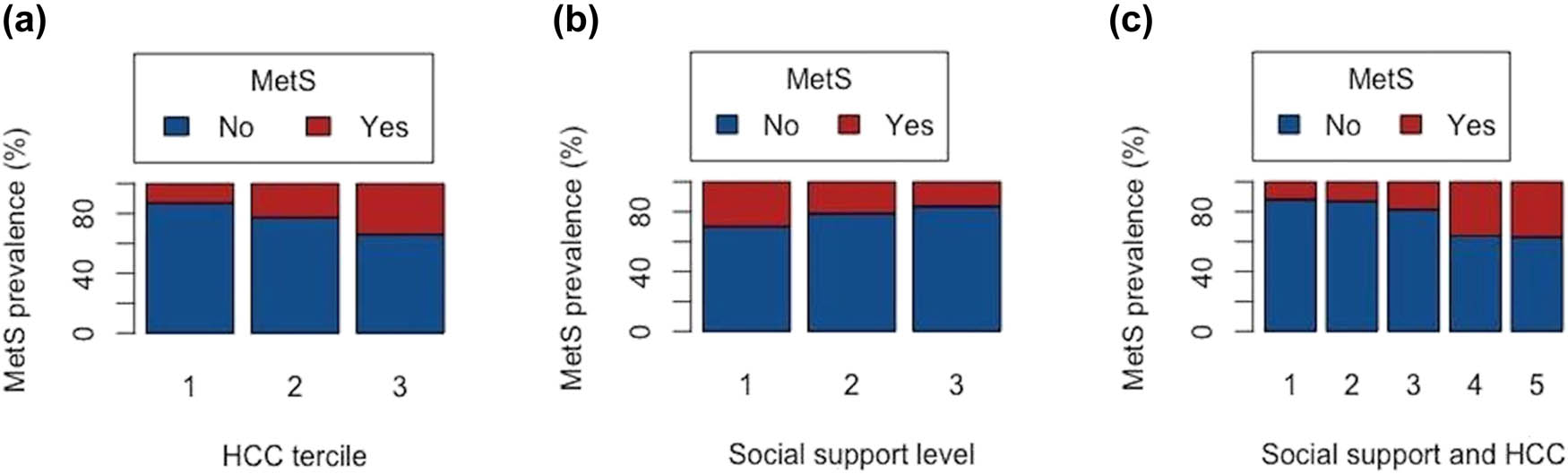

Since significant differences in HCC and social support levels were found between healthy individuals and MetS patients, we divided the entire study sample into three groups according to HCC and social support level terciles. Specifically, 1st, 2nd, and 3rd HCC tercile indicates low, moderate, and high chronic stress level, respectively. Similarly, 1st, 2nd, and 3rd social support tercile means low, moderate, and high subjectively perceived social support level, respectively. The prevalence of MetS (%) significantly increased with HCC, expanding from 13.0 to 33.9% from the first to the third terciles (χ 2 = 6.78, p = 0.034) (Figure 1a). Furthermore, we found statistically significant association between HCC terciles and the prevalence of MetS (contingency coefficient C = 0.200, p = 0.033). Although the frequency of MetS diagnosis decreased from the 1st to the 3rd social support level tercile (from 29.8 to 16.3%) (Figure 1b), the χ 2 test of independence showed that MetS diagnosis was independent of social support level (χ 2 = 2.85, p = 0.241) and its contingency coefficient value was nonsignificant (C = 0.133, p = 0.241). To investigate the relationship between the prevalence of MetS and cumulative effect of chronic stress and social support level, we stratified participants into five groups (1st – low chronic stress and high social support level; 2nd – low chronic stress and moderate social support level or moderate chronic stress and high social support level; 3rd – moderate chronic stress and social support level; 4th – high chronic stress and moderate social support level or moderate chronic stress and low social support level; 5th – high chronic stress and low social support level). Results showed increase in MetS prevalence as going from the 1st to the 5th group (from 11.8 to 36.8%) (Figure 1c) (χ 2 = 9.18, p = 0.066) and contingency coefficient value barely below the level of significance (C = 0.235, p = 0.057).

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome (%) according to HCC (a), social support level (b) terciles and five groups based on both HCC tercile and social support level (c).

We analyzed four logistic regression models: unadjusted (Model 1), age-adjusted (Model 2), age and recreational physical activity-adjusted (Model 3), and age, recreational physical activity, and social support level-adjusted (Model 4) models. The highest HCC tercile was associated with MetS in unadjusted (Model 1) and age-adjusted (Model 2) models. However, after adjustment for age (Model 2), the primary odds ratio found in unadjusted model (Model 1) fell to 2.77 (95% CI: 1.03, 7.49), while an additional adjustment for recreational physical activity (Model 3) resulted in the decrease of odds ratio to 2.60 which was close to being statistically significant. Furthermore, an adjustment for social support level has not changed the results significantly (Model 4). The prevalence of MetS was not significantly different among persons in the second HCC tercile compared with those in the lowest tercile in both unadjusted (Model 1) and adjusted models (Models 2–4) (Table 4).

Logistic regression models predicting MetS prevalence based on HCC terciles

| Hair cortisol terciles | MetS prevalence (%) | Model 1 OR (95% Cl) unadjusted | p-value | Model 2 OR (95% CI) adjusted for age | p-value | Model 3 OR (95% CI) adjusted for age and recreational physical activity | p-value | Model 4 OR (95% CI) adjusted for age, recreational physical activity, and social support | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13.0 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) | ||||

| 2 | 22.6 | 1.97 (0.71, 5.46) | 0.195 | 1.69 (0.59, 4.80) | 0.325 | 1.31 (0.43, 3.96) | 0.638 | 1.23 (0.40, 3.82) | 0.716 |

| 3 | 33.9 | 3.45 (1.31, 9.07) | 0.012 | 2.77 (1.03, 7.49) | 0.044 | 2.60 (0.92, 7.40) | 0.073 | 2.56 (0.90, 7.27) | 0.078 |

Note: Statistically significant odd ratios (95% CI) and the corresponding p-values (<0.05) are shown in bold font.

5 Discussion

The main focus of this study was to evaluate the association of MetS prevalence with objective stress biomarkers and distinct psychosocial stress indicators in young and middle-aged men. Analysis of objective stress biomarkers revealed significantly higher HCC in MetS patients compared with participants without MetS. Also, stratification of HCC into terciles showed that higher HCC tercile is related to increased presence of MetS. These findings are in line with the previous research, showing that the prevalence of MetS was the highest in the third HCC tercile in the population of depressed patients and age- and gender-matched healthy individuals [12]. A recently published case-control study investigated the relationship between HCC and MetS, as well as PTSD and MetS co-occurrence in a population of South African mixed ancestry females. Authors reported no significant association of HCC with MetS or PTSD and MetS comorbidity [35]. These inconsistencies might arise from gender-specific effects, as well as other factors mediating the association between HCC and MetS. For instance, Lehrer et al. [21] found a direct negative association of psychological resilience and MetS severity. The more complex analysis using moderated mediation model indicated that indirect association between perceived stress and MetS via HCC varies as a function of psychological resilience [21]. Thus, factors potentially mediating the relationship between stress and MetS should be explored in the future studies.

We found significant correlations between HCC and distinct criteria of MetS including WC, arterial blood pressure, and fasting glucose concentration. These results support the idea that chronic glucocorticoid excess is manifested by increased adipogenesis of visceral fat, mineralocorticoid receptor-associated hypertension, and induced activities of gluconeogenic enzymes [36,37,38]. Similarly, Kuehl et al. [12] reported that HCC significantly correlated with WC, systolic blood pressure, and TAG concentration. Another study in large aerospace company employees showed significant positive associations of HCC with WC values and glycosylated hemoglobin level [11]. However, a cross-sectional study conducted among HIV-infected patients found no relationship between MetS and individual cardiometabolic measures, except the positive association of MetS with HDL-C concentration [15].

Since no differences in salivary and blood serum cortisol concentrations were observed between MetS patients and subjects without MetS under baseline conditions, our results are in accordance with the evidence that cortisol concentration measurements in hair, saliva, and blood serum samples serve as independent markers of HPA axis activity. Results from the previous research examining the associations between blood serum cortisol and MetS showed inconsistent results. For instance, Park et al. [39] found that increased MetS risk was associated with higher blood serum cortisol even after adjustment for age and body mass index in Korean adults. On the other hand, a study conducted in a sample of older Italian men demonstrated no significant relationship between MetS and cortisol concentration in blood serum [40]. In addition, a more recently published systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies found no evidence of association between MetS and basal cortisol levels measured in saliva, blood serum, and urine samples [41]. The lack of such associations might be explained by the fact that cortisol concentration in biological fluids is dependent on tissue-specific cortisol metabolism including the rate of secretion, inactivation, and excretion [8]. For example, salivary glands possess the activity of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11β-HSD2) enzyme which irreversibly converts cortisol to inactive cortisone [8,42,43]. Thus, diversity of 11β-HSD2 activity results in altered salivary cortisol concentration with cortisol to cortisone ratio ranging from 1:2 to 1:8 [43]. Moreover, it is suggested that increased tissue sensitivity to cortisol due to polymorphisms in glucocorticoid receptor (GR) gene (NR3C1, Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 3 Group C Member 1) is related to the criteria of MetS (e.g., visceral obesity, hypertension), despite normal HPA axis activity [8,41]. These observations emphasize that the link between HPA axis activity and MetS might be affected by variability in cortisol metabolism and tissue-specific sensitivity to glucocorticoids.

Our results showed that among psychosocial indicators, only subjectively perceived social support level differed significantly between MetS patients and participants without MetS. Specifically, significant negative correlations between social support level and WC, as well as fasting glucose concentration, were found. However, when social support level was treated as a categorical variable (i.e., low, moderate, high social support), no evidence of association with the prevalence of MetS was noticed. Similarly, Hwang and Lee [44] reported no significant relationship between the MetS diagnosis and social support level considered as a dichotomous variable in Korean male and female blue-collar workers. A previous study by Ortiz et al. [18] showed a lack of relationship between the prevalence of MetS and social support in U.S. Latino population. Few recently published studies also failed to show any evidence of association between MetS and social support level in a group of cancer caregivers and among medical university staff members [45,46]. In contrast, the SOPKARD study [17] on 476 citizens of Sopot demonstrated that frequency in MetS was significantly higher in individuals with low social support level compared with participants experiencing high social support. In a study conducted by Vigna et al. [47], lower social support at work was related to increased risk of MetS only among women, but not in men attending an annual routine health check-up at an occupational medicine clinic. Thus, these contradictory results may be explained by the differences in the study sample characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status) and instruments used for the evaluation of social support level.

To the best of our knowledge, no other studies assessed the combined effect of HCC and social support level on the prevalence of MetS. Results showed that there is a tendency of increased prevalence of MetS in case of a combination of higher HCC and lower social support level. Our results showed statistically significant MetS predictive effect for the highest hair cortisol tercile even after adjustment for age (2.77 fold raised odds ratio). Inclusion of other potentially confounding factors such as recreational physical activity and social support level resulted in attenuated odds ratio which was close to being statistically significant. This finding is consistent with the study of Stalder et al. [11] who found an increase in MetS prevalence with higher HCC quartile within a large occupational cohort. In contrast, cross-sectional study by Langerak et al. [15] showed that higher risk of MetS was associated with lower HCC (4.23 fold raised odds ratio in the lowest HCC tercile compared with the highest tercile). Authors explained these results by cortisol hypersensitivity which is characterized by low systemic cortisol concentration due to disruption in GR function. Other studies examined predictive value of blood serum and salivary cortisol levels for MetS. Results showed no statistically significant MetS predictive effect of cortisol measured in blood serum as a continuous variable (OR = 0.999, 95% CI (0.997, 1.001)) and distinct salivary cortisol parameters divided into terciles with odds ratio (95% CI), ranging from 0.94 (0.44, 2.01) to 1.43 (0.69, 2.96) for the lowest tercile compared with the top tercile (14,41). Together, these findings indicate methodological advantage of HCC measurement over the analysis of blood serum or salivary cortisol since only long-term changes in cortisol concentration were found to be associated with the increased MetS prevalence.

6 Conclusion

A significant finding in the current study is that chronically elevated cortisol concentration and lower social support level might be potential contributing factors to the development of MetS, while single point salivary or blood serum cortisol measurements reflect acute HPA axis responses which are not associated with metabolic disturbances comprising MetS.

Abbreviations

- 11β-HSD2

-

11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2

- BP

-

blood pressure

- GR

-

glucocorticoid receptor

- HCC

-

hair cortisol concentration

- HDL-C

-

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HPA

-

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

- MetS

-

metabolic syndrome

- TAG

-

triacylglycerol

- WC

-

waist circumference

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Research Council of Lithuania (Grant No. MIP-050/2015).

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Wang HH, Lee DK, Liu M, Portincasa P, Wang DQH. Novel insights into the pathogenesis and management of the metabolic syndrome. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2020;23:189–230.10.5223/pghn.2020.23.3.189Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Han TS, Lean ME. A clinical perspective of obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. J R Soc Med Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;5:1–13.10.1177/2048004016633371Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Saklayen MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20(2):1–8.10.1007/s11906-018-0812-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[4] Nolan PB, Carrick-Ranson G, Stinear JW, Reading SA, Dalleck LC. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome components in young adults: a pooled analysis. Prev Med Reports. 2017;7:211–5. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.07.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Andreassi MG. Metabolic syndrome, diabetes and atherosclerosis: Influence of gene – environment interaction. Mutat Res. 2009;667:35–43.10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.10.018Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[6] Branth S, Ronquist G, Stridsberg M, Hambraeus L, Kindgren E, Olsson R, et al. Development of abdominal fat and incipient metabolic syndrome in young healthy men exposed to long-term stress. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;17:427–35.10.1016/j.numecd.2006.03.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Takahashi A, Ohira T, Okazaki K, Yasumura S, Sakai A, Maeda M, et al. Effects of psychological and lifestyle factors on metabolic syndrome following the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident: the Fukushima health management survey. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2020;27(9):1010–8.10.5551/jat.52225Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Jeong I-K. The role of cortisol in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab J. 2012;36:207–10.10.4093/dmj.2012.36.3.207Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Constantinopoulos P, Michalaki M, Kottorou A, Habeos I, Psyrogiannis A, Kalfarentzos F, et al. Cortisol in tissue and systemic level as a contributing factor to the development of metabolic syndrome in severely obese patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;172(1):69–78.10.1530/EJE-14-0626Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Wester VL, van Rossum EFC. Obesity and metabolic syndrome: a phenotype of mild long-term hypercortisolism? In: The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in health and disease. New York: Springer; 2017. p. 303–13.10.1007/978-3-319-45950-9_15Suche in Google Scholar

[11] Stalder T, Kirschbaum C, Alexander N, Bornstein SR, Gao W, Miller R, et al. Cortisol in hair and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(6):2573–80.10.1210/jc.2013-1056Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Kuehl LK, Hinkelmann K, Muhtz C, Dettenborn L, Wingenfeld K, Spitzer C, et al. Hair cortisol and cortisol awakening response are associated with criteria of the metabolic syndrome in opposite directions. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:365–70. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.09.012.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Garcez A, Weiderpass E, Canuto R, Bünecker Lecke S, Spritzer PM, Pattussi MP, et al. Salivary cortisol, perceived stress, and metabolic syndrome: a matched case-control study in female shift workers. Horm Metab Res. 2017;49(7):510–9.10.1055/s-0043-101822Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Martinac M, Babić D, Bevanda M, Vasilj I, Bevanda Glibo D, Karlović D, et al. Activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and inflammatory mediators in major depressive disorder with or without metabolic syndrome. Psychiatr Danub. 2017;29(1):39–50.10.24869/psyd.2017.39Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Langerak T, van den Dries LWJ, Wester VL, Staufenbiel SM, Manenschijn L, van Rossum EFC, et al. The relation between long-term cortisol levels and the metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;83:167–72.10.1111/cen.12790Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Almadi T, Cathers I, Chow CM. Associations among work-related stress, cortisol, inflammation, and metabolic syndrome. Psychophysiology. 2013;50:821–30.10.1111/psyp.12069Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Pakalska-Korcala A, Zdrojewski T, Piwoński J, Gil K, Chwojnicki K, Ignaszewska-Wyrzykowska A, et al. Social support level in relation to metabolic syndrome – results of the SOPKARD study. Kardiol Pol. 2008;66(5):500–6.Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Ortiz MS, Myers HF, Schetter CD, Rodriguez CJ, Seeman TE. Psychosocial predictors of metabolic syndrome among Latino groups in the multi- ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). PLoS One. 2015;10(4):1–12.10.1371/journal.pone.0124517Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Masters Pedersen J, Lund R, Andersen I, Jessie Clark A, Prescott E, Hulvej Rod N, et al. Psychosocial risk factors for the metabolic syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2016;215:41–6. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.076.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[20] Tenk J, Mátrai P, Hegyi P, Rostás I, Garami A, Szabó I, et al. Perceived stress correlates with visceral obesity and lipid parameters of the metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;95:63–73.10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.014Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Lehrer HM, Steinhardt MA, Dubois SK, Laudenslager ML. Perceived stress, psychological resilience, hair cortisol concentration, and metabolic syndrome severity: a moderated mediation model. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;113:1–8.10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.104510Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Lee DY, Kim E, Choi MH. Technical and clinical aspects of cortisol as a biochemical marker of chronic stress. BMB Rep. 2015;48(4):209–16.10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.4.275Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Russell E, Koren G, Rieder M, van Uum S. Hair cortisol as a biological marker of chronic stress: current status, future directions and unanswered questions. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:589–601. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.009.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Greff MJE, Levine JM, Abuzgaia AM, Elzagallaai AA, Michael RJ, van Uum SHM. Hair cortisol analysis: an update on methodological considerations and clinical applications. Clin Biochem. 2019;63:1–9.10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.09.010Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Clow A, Smyth N. Salivary cortisol as a non-invasive window on the brain [Internet]. Vol. 150, 1st ed. International review of neurobiology. Cambridge: Elsevier Inc; 2020. p. 1–16. 10.1016/bs.irn.2019.12.003.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Stalder T, Kirschbaum C. Analysis of cortisol in hair – state of the art and future directions. Brain, Behav Immun. 2012;26:1019–29. 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.02.002.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Meyer JS, Novak MA. Hair cortisol: a novel biomarker of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical activity. Endocrinology. 2012;153(9):4120–7.10.1210/en.2012-1226Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Lanfear JH, Voegel CD, Binz TM, Paul RA. Hair cortisol measurement in older adults: influence of demographic and physiological factors and correlation with perceived stress. Steroids. 2020;163:1–10. 10.1016/j.steroids.2020.108712.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Kristenson M, Kucinskiene Z, Bergdahl B, Calkauskas H, Urmonas V, Orth-Gomer K. Increased psychosocial strain in Lithuanian versus Swedish men: the LiVicordia study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:277–82.10.1097/00006842-199805000-00011Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Reynolds W, Gould J. A psychometric investigation of the standard and short form beck depression inventory. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1981;49(2):306–7.10.1037/0022-006X.49.2.306Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Alberti G, Zimmet P, Shaw J, Grundy SM. The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. IDF Commun. 2006;1–24.10.3109/9781420020601-2Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Unger T, Borghi C, Charchar F, Khan NA, Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, et al. International society of hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75(6):1334–57.10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15026Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Raul J-S, Cirimele V, Ludes B, Kintz P. Detection of physiological concentrations of cortisol and cortisone in human hair. Clin Biochem. 2004;37:1105–11.10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.02.010Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] de Palo EF, Antonelli G, Benetazzo A, Prearo M, Gatti R. Human saliva cortisone and cortisol simultaneous analysis using reverse phase HPLC technique. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;405:60–5.10.1016/j.cca.2009.04.006Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] van den Heuvel LL, Stalder T, du Plessis S, Suliman S, Kirschbaum C, Seedat S. Hair cortisol levels in posttraumatic stress disorder and metabolic syndrome. Stress. 2020;23(5):577–89. 10.1080/10253890.2020.1724949.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Arnaldi G, Scandali VM, Trementino L, Cardinaletti M, Appolloni G, Boscaro M. Pathophysiology of dyslipidemia in Cushing’s syndrome. Neuroendocrinology. 2010;92(suppl 1):86–90.10.1159/000314213Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Baid S, Nieman LK. Glucocorticoid excess and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2004;6:493–9.10.1007/s11906-004-0046-0Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Khani S, Tayek JA. Cortisol increases gluconeogenesis in humans: its role in the metabolic syndrome. Clin Sci. 2001;101:739–47.10.1042/CS20010180Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Park SB, Blumenthal JA, Lee SY, Georgiades A. Association of cortisol and the netabolic syndrome in Korean men and women. J Korean Med Sci. 2011;26:914–8.10.3346/jkms.2011.26.7.914Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Maggio M, Lauretani F, Ceda PG, Bandinelli S, Basaria S, Ble A, et al. Association between hormones and metabolic syndrome in older Italian men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(12):1832–8.10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00963.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Garcez A, Leite HM, Weiderpass E, Paniz VMV, Watte G, Canuto R, et al. Basal cortisol levels and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;95:50–62.10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.023Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[42] Chrousos G. The role of stress and the hypothalamic – pituitary – adrenal axis in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome: neuro-endocrine and target tissue-related causes. Int J Obes. 2000;24(Suppl2):50–5.10.1038/sj.ijo.0801278Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Wood P. Salivary steroid assays – research or routine? Ann Clin Biochem. 2009;46:183–96.10.1258/acb.2008.008208Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Hwang WJ, Lee CY. Effect of psychosocial factors on metabolic syndrome in male and female blue-collar workers. Japan J Nurs Sci. 2014;11:23–34.10.1111/j.1742-7924.2012.00226.xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[45] Eftekhari S, Alipour F, Aminian O, Saraei M. The association between job stress and metabolic syndrome among medical university staff. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2021;13(1):338–42.10.1007/s40200-021-00748-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[46] Steel JL, Cheng H, Pathak R, Wang Y, Miceli J, Hecht CL, et al. Psychosocial and behavioral pathways of metabolic syndrome in cancer caregivers. Psychooncology. 2019;28(8):1735–42.10.1002/pon.5147Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[47] Vigna L, Brunani A, Brugnera A, Grossi E, Compare A, Tirelli AS, et al. Determinants of metabolic syndrome in obese workers: gender differences in perceived job-related stress and in psychological characteristics identified using artificial neural networks. Eat Weight Disord. 2019;24(1):73–81. 10.1007/s40519-018-0536-8.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Eglė Mazgelytė et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells

- Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 in healthy paediatric population

- Algorithm of rational approach to reconstruction in Fournier’s disease

- A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury

- Src-1 and SP2 promote the proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Dexmedetomidine may decrease the bupivacaine toxicity to heart

- Hypoxia stimulates the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma via up-regulating the NUSAP1 expression

- Long noncoding RNA XIST knockdown relieves the injury of microglia cells after spinal cord injury by sponging miR-219-5p

- External fixation via the anterior inferior iliac spine for proximal femoral fractures in young patients

- miR-128-3p reduced acute lung injury induced by sepsis via targeting PEL12

- HAGLR promotes neuron differentiation through the miR-130a-3p-MeCP2 axis

- Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 is elevated in serum of patients with heart failure and correlates with the disease severity and patient’s prognosis

- Cell population data in identifying active tuberculosis and community-acquired pneumonia

- Prognostic value of microRNA-4521 in non-small cell lung cancer and its regulatory effect on tumor progression

- Mean platelet volume and red blood cell distribution width is associated with prognosis in premature neonates with sepsis

- 3D-printed porous scaffold promotes osteogenic differentiation of hADMSCs

- Association of gene polymorphisms with women urinary incontinence

- Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels of urologic patients

- miR-496 inhibits proliferation via LYN and AKT pathway in gastric cancer

- miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development

- Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- Fluorescent light energy modulates healing in skin grafted mouse model

- Silencing CDK6-AS1 inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory damage in HK-2 cells

- Predictive effect of DCE-MRI and DWI in brain metastases from NSCLC

- Severe postoperative hyperbilirubinemia in congenital heart disease

- Baicalin improves podocyte injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

- Clinical factors predicting ureteral stent failure in patients with external ureteral compression

- Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway

- Triple-Endobutton and clavicular hook: A propensity score matching analysis

- Long noncoding RNA MIAT inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy and the activation of NF-κB pathway in high glucose-treated renal tubular epithelial cells by the miR-182-5p/GPRC5A axis

- Serum exosomal miR-122-5p, GAS, and PGR in the non-invasive diagnosis of CAG

- miR-513b-5p inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells by targeting TRIB1

- Fer exacerbates renal fibrosis and can be targeted by miR-29c-3p

- The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-92a in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prognostic value of α2δ1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study

- No significant benefit of moderate-dose vitamin C on severe COVID-19 cases

- circ_0000467 promotes the proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating KLF12 expression by sponging miR-4766-5p

- Downregulation of RAB7 and Caveolin-1 increases MMP-2 activity in renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxic conditions

- Educational program for orthopedic surgeons’ influences for osteoporosis

- Expression and function analysis of CRABP2 and FABP5, and their ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

- lncRNA-ZFAS1 promotes the progression of endometrial carcinoma by targeting miR-34b to regulate VEGFA expression

- Anticoagulation is the answer in treating noncritical COVID-19 patients

- Effect of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis on PFS after haplo-PBSCT

- Comparison of Dako HercepTest and Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2 (4B5) tests and their correlation with silver in situ hybridization in lung adenocarcinoma

- VSTM1 regulates monocyte/macrophage function via the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Comparison of vaginal birth outcomes in midwifery-led versus physician-led setting: A propensity score-matched analysis

- Treatment of osteoporosis with teriparatide: The Slovenian experience

- New targets of morphine postconditioning protection of the myocardium in ischemia/reperfusion injury: Involvement of HSP90/Akt and C5a/NF-κB

- Superenhancer–transcription factor regulatory network in malignant tumors

- β-Cell function is associated with osteosarcopenia in middle-aged and older nonobese patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study

- Clinical features of atypical tuberculosis mimicking bacterial pneumonia

- Proteoglycan-depleted regions of annular injury promote nerve ingrowth in a rabbit disc degeneration model

- Effect of electromagnetic field on abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- miR-150-5p affects AS plaque with ASMC proliferation and migration by STAT1

- MALAT1 promotes malignant pleural mesothelioma by sponging miR-141-3p

- Effects of remifentanil and propofol on distant organ lung injury in an ischemia–reperfusion model

- miR-654-5p promotes gastric cancer progression via the GPRIN1/NF-κB pathway

- Identification of LIG1 and LIG3 as prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer

- MitoQ inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis by enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy

- Dissecting role of founder mutation p.V727M in GNE in Indian HIBM cohort

- circATP2A2 promotes osteosarcoma progression by upregulating MYH9

- Prognostic role of oxytocin receptor in colon adenocarcinoma

- Review Articles

- The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Efficacy and safety of therapeutic plasma exchange in stiff person syndrome

- Role of cesarean section in the development of neonatal gut microbiota: A systematic review

- Small cell lung cancer transformation during antitumor therapies: A systematic review

- Research progress of gut microbiota and frailty syndrome

- Recommendations for outpatient activity in COVID-19 pandemic

- Rapid Communication

- Disparity in clinical characteristics between 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia and leptospirosis

- Use of microspheres in embolization for unruptured renal angiomyolipomas

- COVID-19 cases with delayed absorption of lung lesion

- A triple combination of treatments on moderate COVID-19

- Social networks and eating disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Letter

- COVID-19, WHO guidelines, pedagogy, and respite

- Inflammatory factors in alveolar lavage fluid from severe COVID-19 pneumonia: PCT and IL-6 in epithelial lining fluid

- COVID-19: Lessons from Norway tragedy must be considered in vaccine rollout planning in least developed/developing countries

- What is the role of plasma cell in the lamina propria of terminal ileum in Good’s syndrome patient?

- Case Report

- Rivaroxaban triggered multifocal intratumoral hemorrhage of the cabozantinib-treated diffuse brain metastases: A case report and review of literature

- CTU findings of duplex kidney in kidney: A rare duplicated renal malformation

- Synchronous primary malignancy of colon cancer and mantle cell lymphoma: A case report

- Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography and pathologic characters of CD68 positive cell in primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: A case report and literature review

- Persistent SARS-CoV-2-positive over 4 months in a COVID-19 patient with CHB

- Pulmonary parenchymal involvement caused by Tropheryma whipplei

- Mediastinal mixed germ cell tumor: A case report and literature review

- Ovarian female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin – Case report

- Rare paratesticular aggressive angiomyxoma mimicking an epididymal tumor in an 82-year-old man: Case report

- Perimenopausal giant hydatidiform mole complicated with preeclampsia and hyperthyroidism: A case report and literature review

- Primary orbital ganglioneuroblastoma: A case report

- Primary aortic intimal sarcoma masquerading as intramural hematoma

- Sustained false-positive results for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M: A case report and literature review

- Peritoneal loose body presenting as a hepatic mass: A case report and review of the literature

- Chondroblastoma of mandibular condyle: Case report and literature review

- Trauma-induced complete pacemaker lead fracture 8 months prior to hospitalization: A case report

- Primary intradural extramedullary extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PIEES/PNET) of the thoracolumbar spine: A case report and literature review

- Computer-assisted preoperative planning of reduction of and osteosynthesis of scapular fracture: A case report

- High quality of 58-month life in lung cancer patient with brain metastases sequentially treated with gefitinib and osimertinib

- Rapid response of locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma to apatinib: A case report

- Retrieval of intrarenal coiled and ruptured guidewire by retrograde intrarenal surgery: A case report and literature review

- Usage of intermingled skin allografts and autografts in a senior patient with major burn injury

- Retraction

- Retraction on “Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappa B pathway”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part I

- An artificial immune system with bootstrap sampling for the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial cancers

- Breast cancer recurrence prediction with ensemble methods and cost-sensitive learning

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells

- Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 in healthy paediatric population

- Algorithm of rational approach to reconstruction in Fournier’s disease

- A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury

- Src-1 and SP2 promote the proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Dexmedetomidine may decrease the bupivacaine toxicity to heart

- Hypoxia stimulates the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma via up-regulating the NUSAP1 expression

- Long noncoding RNA XIST knockdown relieves the injury of microglia cells after spinal cord injury by sponging miR-219-5p

- External fixation via the anterior inferior iliac spine for proximal femoral fractures in young patients

- miR-128-3p reduced acute lung injury induced by sepsis via targeting PEL12

- HAGLR promotes neuron differentiation through the miR-130a-3p-MeCP2 axis

- Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 is elevated in serum of patients with heart failure and correlates with the disease severity and patient’s prognosis

- Cell population data in identifying active tuberculosis and community-acquired pneumonia

- Prognostic value of microRNA-4521 in non-small cell lung cancer and its regulatory effect on tumor progression

- Mean platelet volume and red blood cell distribution width is associated with prognosis in premature neonates with sepsis

- 3D-printed porous scaffold promotes osteogenic differentiation of hADMSCs

- Association of gene polymorphisms with women urinary incontinence

- Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels of urologic patients

- miR-496 inhibits proliferation via LYN and AKT pathway in gastric cancer

- miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development

- Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- Fluorescent light energy modulates healing in skin grafted mouse model

- Silencing CDK6-AS1 inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory damage in HK-2 cells

- Predictive effect of DCE-MRI and DWI in brain metastases from NSCLC

- Severe postoperative hyperbilirubinemia in congenital heart disease

- Baicalin improves podocyte injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

- Clinical factors predicting ureteral stent failure in patients with external ureteral compression

- Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway

- Triple-Endobutton and clavicular hook: A propensity score matching analysis

- Long noncoding RNA MIAT inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy and the activation of NF-κB pathway in high glucose-treated renal tubular epithelial cells by the miR-182-5p/GPRC5A axis

- Serum exosomal miR-122-5p, GAS, and PGR in the non-invasive diagnosis of CAG

- miR-513b-5p inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells by targeting TRIB1

- Fer exacerbates renal fibrosis and can be targeted by miR-29c-3p

- The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-92a in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prognostic value of α2δ1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study

- No significant benefit of moderate-dose vitamin C on severe COVID-19 cases

- circ_0000467 promotes the proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating KLF12 expression by sponging miR-4766-5p

- Downregulation of RAB7 and Caveolin-1 increases MMP-2 activity in renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxic conditions

- Educational program for orthopedic surgeons’ influences for osteoporosis

- Expression and function analysis of CRABP2 and FABP5, and their ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

- lncRNA-ZFAS1 promotes the progression of endometrial carcinoma by targeting miR-34b to regulate VEGFA expression

- Anticoagulation is the answer in treating noncritical COVID-19 patients

- Effect of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis on PFS after haplo-PBSCT

- Comparison of Dako HercepTest and Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2 (4B5) tests and their correlation with silver in situ hybridization in lung adenocarcinoma