Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

-

Zbyněk Tüdös

, Paulína Szász

Abstract

Foci of splenic tissue separated from the spleen can occur as a congenital anomaly. Isolated nodules of splenic tissue are called accessory spleens or spleniculli. However, nodules of splenic tissue can merge with other organs during embryonic development, in which case we speak of spleno-visceral fusions: most often, they merge with the tail of the pancreas (thus forming spleno-pancreatic fusion or an intrapancreatic accessory spleen), with the reproductive gland (i.e., spleno-gonadal fusion), or with the kidney (i.e., spleno-renal fusion). Our case report describes the fusion of heterotopic splenic tissue with the right adrenal gland, which was misinterpreted as a metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of spleno-adrenal fusion. Spleno-visceral fusions usually represent asymptomatic conditions; their main clinical significance lies in the confusion they cause and its misinterpretation as tumors of other organs. We believe that the cause of retroperitoneal spleno-visceral fusions is the anomalous migration of splenic cells along the dorsal mesentery to the urogenital ridge, together with primitive germ cells, at the end of the fifth week and during the sixth week of embryonic age. This theory explains the possible origin of spleno-visceral fusions, their different frequency of occurrence, and the predominance of findings on the left side.

1 Introduction

Congenital heterotopia of splenic tissue can occur in the form of isolated accessory spleens, which are relatively common, or in the form of spleno-visceral fusions, i.e., the association of splenic tissue with another abdominal organ. These are asymptomatic conditions; their main clinical significance lies in the confusion they cause and its misinterpretation as tumors of other organs. So far, cases or even smaller groups of patients with spleno-pancreatic, spleno-gonadal, and spleno-renal fusion have been published. Our article presents a case report of fusion of heterotopic splenic tissue and the right adrenal gland. The finding was mistaken for an adrenal metastasis of a renal carcinoma of the right kidney; the correct diagnosis was made by histology after an adrenalectomy. In the discussion, we present a possible embryological basis for this anomaly, but also for other spleno-visceral fusions in the retroperitoneum.

2 Case report

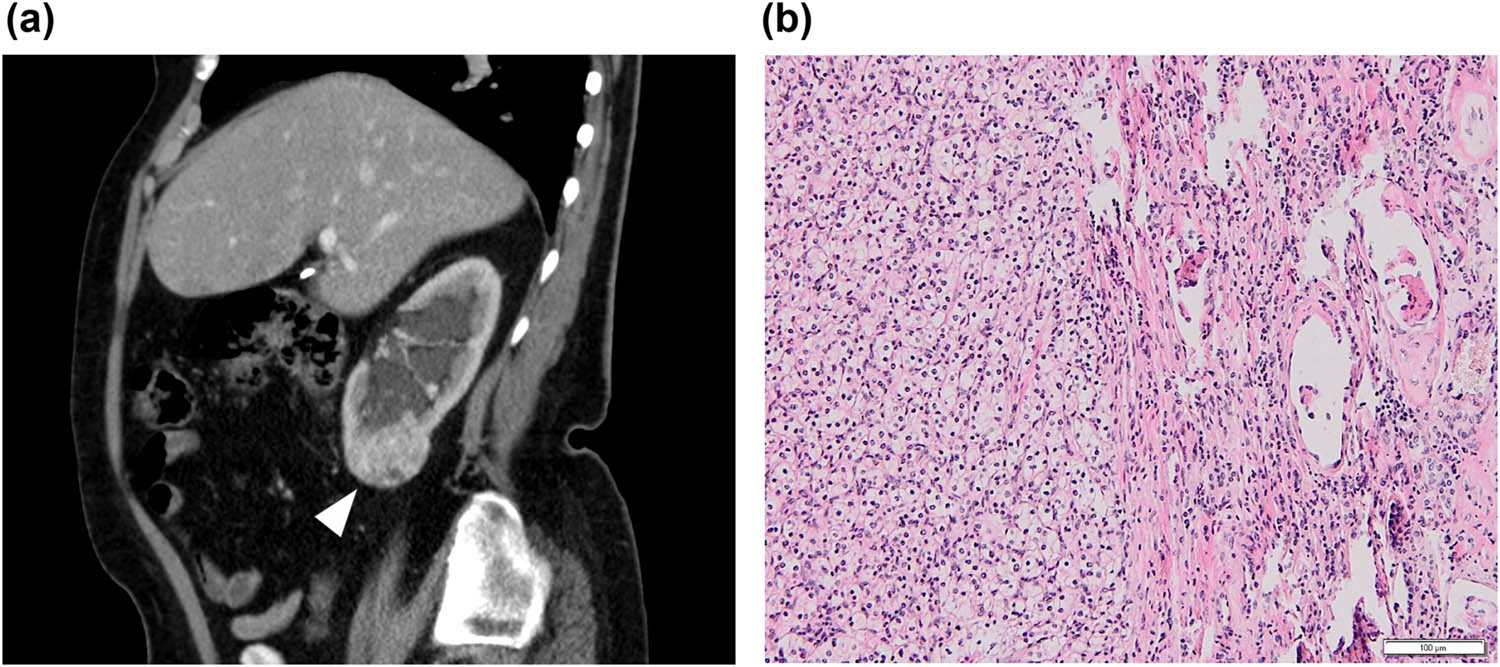

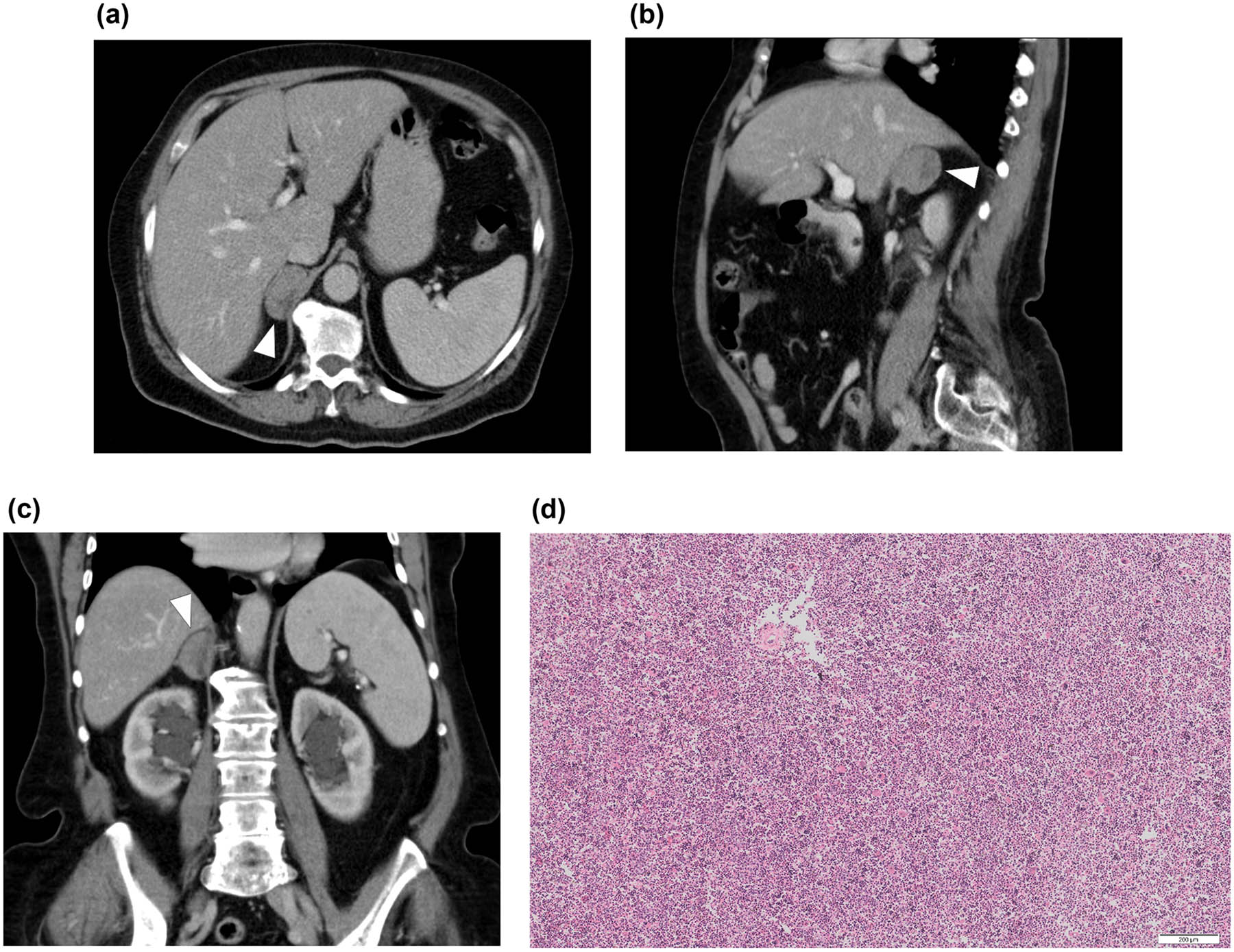

A 79-year-old female patient with dyspnea underwent computed tomography (CT) angiography to rule out pulmonary embolism in October 2017. There was only arterial hypertension, bilateral hip arthroplasty, and laparoscopically assisted cholecystectomy in the patient’s history. A mass on the right adrenal gland was incidentally detected on the CT scan. With this finding, the patient was referred to a urological department in a tertiary medical center. A lesion of the right adrenal gland was confirmed on the subsequent abdominal CT, and in addition, another incidental lesion was found on the right kidney. A tumor on the lower pole of the right kidney measured 45 × 38 × 34 mm, with significant heterogeneous enhancement; it was interpreted as a suspected renal cell carcinoma (Figure 1a). The mass on the right adrenal gland had dimensions of 41 × 38 × 24 mm (Figure 2a–c); its attenuation was 41 Hounsfield units (HU) in the unenhanced phase, 71 HU in the venous phase, and 64 HU in the late phase; the absolute percentage rate was 23.3% and the relative percentage rate was 9.9%. Neither the unenhanced attenuation nor the values of the wash-out rate indicated a typical adenoma; therefore, the lesion had to be classified as indeterminate. Endocrinological examination did not reveal increased hormonal activity. With regard to the finding of a tumor of the right kidney, metastasis seemed to be the most likely. Unfortunately, about 20% of patients with a malignant renal tumor are diagnosed in the metastatic stage [1]. A suspected malignant renal tumor should be removed with clear surgical margins [2,3]. In the case of cT1 renal neoplasm, partial nephrectomy or enucleation is recommended [4,5] in order to preserve renal function [3] for eventual adjuvant therapy. Therefore, a combined surgical procedure was indicated to remove both the renal and adrenal mass in December 2017. First, a robot-assisted partial nephrectomy was performed on the right kidney using a 5-port transperitoneal approach; the warm ischemia time was 19 min. A right-sided robot-assisted adrenalectomy followed directly. The patient was lying in the left lateral decubitus position, the overall operating time was 95 min and blood loss was minimal. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day.

(a) Abdominal CT scan revealing a mass on the lower pole of the right kidney (arrowhead) in the sagittal plane. (b) Histology confirmed the renal tumor to be a conventional renal cell carcinoma grade I–II (hematoxylin & eosin, 100×).

Abdominal CT scan revealing the mass of the right adrenal gland (arrowheads) in (a) the axial plane, (b) the sagittal plane, and (c) the coronal plane. Note the orthotopic intact spleen. There are clips after a cholecystectomy in the hepatic hilum and parapelvic cysts of the right kidney as additional findings. (d) Histology proved heterotopic splenic tissue connected to the right adrenal gland. The sample included a large proportion of red pulp with the presence of extramedullary hematopoiesis; damaged white pulp with a central artery is also present (hematoxylin & eosin, 100×).

Histological examination of the right kidney tissue confirmed a clear cell renal carcinoma pT1b, N0, M0, grade I–II (Figure 1b). The removed adrenal gland was without any metastatic involvement, but the cortical layer of its medial limb was fused with a nodule surprisingly formed by the splenic parenchyma with a large proportion of red pulp with the presence of extramedullary hematopoiesis (Figure 2d). In the case of hematopoietic elements included inside an adrenal tumor, it is necessary to consider the differential diagnostic possibility of an adrenal myelolipoma, which is a benign tumor-like lesion composed of mature adipose tissue admixed with hematopoietic elements in various proportions [6]. In our case, the sample contained splenic white pulp; on the other hand, it did not contain a fat component, and therefore, it was possible to rule out a myelolipoma.

The patient underwent follow-up abdominal CT in July 2018; the finding was without recurrence of the tumor. At the last follow-up clinical check in March 2020, the patient felt in good health condition.

Regarding the management of such a case, we believe that spleno-adrenal fusion is an extremely rare anomaly and could not be predicted a priori. In similar conditions that are more common in clinical practice, such as splenosis or accessory spleens mimicking a neoplastic lesion, the suspicion may be confirmed by 99m Technetium heat-damaged red blood cell scintigraphy combined with single-photon emission CT.

The patient provided an informed consent to all the diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Further, the patient provided a general informed consent to the use of the results of the examination methods for the purposes of research and publication, which is included as a part of the informed consent for hospitalization in our department.

3 Discussion

3.1 Splenic heterotopy and the development of the spleen

Foci of splenic tissue separated from the main body of the spleen can occur for several reasons. In general, they are considered asymptomatic and only very rarely is their presence accompanied by complications, such as torsion of a wandering accessory spleen or bleeding caused by spontaneous rupture [7]. The main clinical problem is their differential diagnostic confusion with tumor lesions. Although spleen tissue foci may occur in different areas of the abdomen and chest, in this discussion we will focus on their occurrence in the region of the retroperitoneum and retroperitoneal organs.

Splenosis represents one of the possible causes of foci of splenic tissue occurring in different regions of the body. It is not a congenital condition, but an autotransplantation of the splenic parenchyma at the time of trauma or a splenectomy [8]. If a focus of splenosis occurs in the suprarenal area, it can be confused with an adrenal tumor; such cases have already been described in the literature [8,9,10]. As already mentioned, splenosis should be considered in a patient with a history of splenic trauma or splenectomy. Heterotopy of the splenic tissue may be congenital.

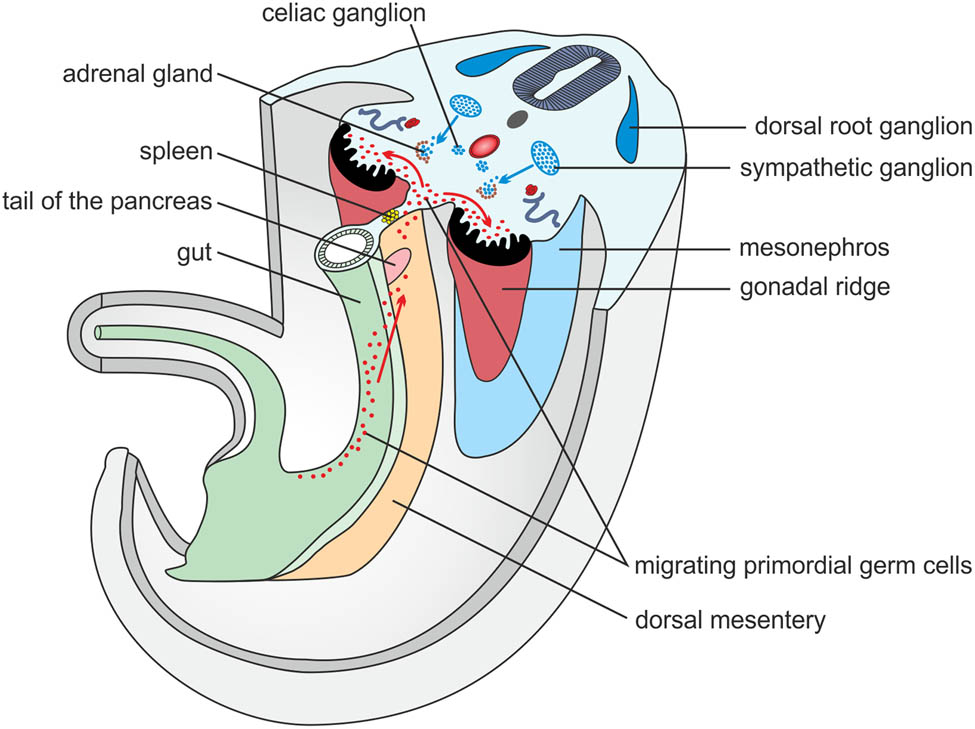

The spleen is derived from a mass of mesenchymal cells located between the layers of the dorsal mesogastrium and begins to develop during the fifth week [11]. The proliferating cells invade the underlying angiogenetic mesenchyme, which becomes condensed and vascularized. The process occurs simultaneously in several adjoining areas, which soon fuse to form a lobulated fetal spleen (Figure 3) [12]; the lobules normally disappear before birth [11]. Accessory spleens may be formed during embryonic development as heterotopic splenic tissue [12]; the occurrence of such a variety is reported in 4–15% of the population [12]. The most common localization is in the hilum of the main spleen, the great omentum, the gastrosplenic or spleno-renal ligament, and the pelvis [12]. It should also be emphasized that in humans ectopic splenic tissue also has a different architecture compared to a normal spleen, with plenty of red pulp and quite a small area of white pulp [13,14]. Accessory spleens may represent a differential diagnostic challenge, and several cases of an accessory spleen being mistaken for an adrenal tumor have been published [15,16,17]. The very rare accessory spleens mimicking a retroperitoneal tumor on the right side represent an even more challenging situation [18,19,20]. If a developmentally separate heterotopic splenic nodule is directly connected to another organ, the term “spleno-visceral fusion” should be used instead of “accessory spleen;” however, there is inconsistency in the literature and the term “accessory spleen” is also used in this context [21].

A scheme showing a transsection of an embryo during the fifth week of embryonic age. Note the primordial germ cells migrating along the dorsal mesentery into the retroperitoneum in close proximity to the developing spleen.

3.2 Spleno-pancreatic fusion and the development of the pancreas

Compared to other types of spleno-visceral fusions, fusion with the pancreas is probably the most common. Unver Dogan et al. report the occurrence of heterotopic splenic tissue within the tail of the pancreas in 0.7% of autopsies [12]. Case reports of splenic tissue being mistaken for a tumor of the pancreatic tail have also been published [22,23] and criteria to distinguish the two using magnetic resonance imaging have been proposed [21].

The embryological explanation is relatively straightforward, as the spleen and tail of the pancreas have their embryological origin in the dorsal mesogastrium during the fifth week and lie in relatively close proximity to one another (Figure 3) [11]. This fact may also explain the relatively high frequency of this type of fusion.

3.3 Spleno-gonadal fusion and the development of gonads

The connection of the spleen and reproductive glands is the second most common form of fusion; so far about 175 cases have been described [24]. Spleno-gonadal fusion can be classified into continuous or discontinuous types on the basis of the presence or absence of a continuous band of splenic tissue or a fibrous cord connecting the spleen and the gonad [25]. Out of 84 spleno-gonadal fusions, the majority were described in boys, and the gender difference is explained by the better availability of testes for clinical examination [25,26]. Only isolated cases are described on the right side [25,27]. The anomaly occurs in two forms, allowing division of the cases into two major subgroups: (1) continuous spleno-gonadal fusion, in which a continuous cord-like structure connects the spleen and the gonadal-mesonephric structures; (2) discontinuous spleno-gonadal fusion, in which the fused spleno-gonadal-mesonephric structures have lost continuity with the main spleen [28]. The continuous type is often associated with other congenital anomalies, especially of the limbs and lower jaw [25,28]. On the contrary, a single case classified as being the discontinuous type associated with other anomalies was described [25]. Thus, there is a theory according to which continuous spleno-gonadal fusion, with its associated high incidence of limb and jaw defects, is probably caused by a teratogenic insult between the fifth and eighth weeks of embryonic age, whereas discontinuous spleno-gonadal fusion represents a rare variant of an accessory spleen [29]. Thus, the theories of the embryological basis of spleno-visceral fusions below probably relate only to the discontinuous fusion.

The initial stages of gonadal development occur during the fifth week, when a thickened area of the mesothelium develops on the posterior abdominal wall on the medial side of the mesonephros. The proliferating epithelium and underlying mesenchyme create a bulge called the genital ridge (Figure 3) [30]. Primordial germ cells are large, spherical sex cells and originate from the endodermal cells of the umbilical vesicle near the origin of the allantois. During the fourth and fifth weeks, primordial germ cells migrate by amoeboid movement along the dorsal mesentery of the hindgut to the gonadal ridges, where they arrive during the sixth week (Figure 3) [30]. Approximately in the eighth week, the gonadal glands start to descend into the pelvis [30].

3.4 Spleno-renal fusion and the development of the kidney

Congenital connections of heterotopic splenic tissue and the kidney are much rarer in the literature than are those of the reproductive organs; so far about 13 cases have been published, including four in the right kidney [31,32,33,34,35,36].

Three slightly overlapping kidney systems are formed in the urogenital ridge during intrauterine life. The first of these systems, called the pronephros, is rudimentary and nonfunctional. It is presented during the fourth week [37]. The second system, called the mesonephros, starts to develop at the end of the fourth week and is temporarily functional until approximately the tenth week (Figure 3). The third kidney system, called the metanephros, forms the permanent kidney and develops between the fifth and the tenth week [37]. From the fifth to the ninth week, the permanent kidneys change their relative position in the caudal direction because of disproportional growth of the embryo’s body [37]. According to Rosenthal et al., there are several predisposing conditions for the formation of spleno-renal fusion. It must occur between the sixth and the ninth week of development, when the kidney reaches its final position [31]. Alternatively, the holonephric theory of the blurring of the distinction among the pronephros, mesonephros, and metanephros in renal development or the migration of splenic cells via blood supply could explain spleno-renal fusion at a later stage [31].

3.5 Spleno-adrenal fusion and the development of the adrenal gland

Congenital connections of heterotopic splenic tissue and the adrenal gland have been theoretically assumed, but we were unable to find any documented case of spleno-adrenal fusion. There are several case reports of accessory spleens in the right suprarenal space misinterpreted as retroperitoneal neoplasms, but there was no direct connection to the right adrenal gland [18,19,20]. As already mentioned, an adrenal myelolipoma should be considered and ruled out if an adrenal tissue sample contains hematopoietic elements. The adrenal gland develops from two components: a mesodermal portion, which forms the cortex, and an ectodermal portion, which forms the medulla. During the fifth week of development, mesothelial cells between the root of the mesentery and the developing gonad at the level of the celiac plexus begin to proliferate and penetrate the underlying mesenchyme to create the fetal cortex (Figure 3) [38,39]. The second wave of mesothelial cells creates the definitive cortex [39]. While the fetal cortex is being formed, neural crest cells originating in the adjacent sympathetic ganglion invade its medial aspect, where they are arranged in cords and clusters (Figure 3). These cells give rise to the medulla of the adrenal gland [39].

3.6 The hypotheses explaining spleno-visceral fusion

Several theories have been proposed that attempt to explain the embryological background of retroperitonal spleno-visceral fusions. To the best of our knowledge, Sneath came up with the first hypothesis in 1913 [40]. He pointed out that the spleen, as it is developed in the dorsal mesogastrium, lies in apposition to the urogenital ridge lying upon the posterior wall of the abdomen during the sixth week. He assumed that slight inflammation of the peritoneum may cause an adhesion to be formed between the spleen and the genital gland [40]. It should be emphasized that Sneath postulated his hypothesis to clarify the case of left-sided continuous spleno-testicular fusion. The adhesion hypothesis of the origin of spleno-gonadal fusion was later accepted by other authors, with special emphasis on the fragility of the spleen, e.g., by Talmann in 1926 [41]. The fragility of the spleen was reported to result in the loss of its tissue along the path of development during the mechanical injuries caused by the adhesions. However, this theory of simple adhesion has its weak points. Specifically, it does not explain the findings of splenic tissue nesting deep inside the parenchyma of other organs. And further, a right-sided finding would remain unexplained. In 1953, Hochstetter published his theory, which sought to explain the occurrence of heterotopic splenic tissue inside the left ovary of a left-sided thoracopagus twin specimen [42]. He assumed the migration of splenic cells along the caudal limiting fold, which is the medial and most caudal portion of the pleural-peritoneal membrane (Septum pleuroperitoneale mediale), which would provide a direct route from the dorsal mesogastrium to the retroperitoneum [42]. However, as Rosenthal et al. have noted, Hochstetter’s hypothetical way of migration does not explain the rare findings of right-sided fusions since the caudal limiting fold provides access only to the left retroperitoneum, and in addition, the hypothesis could explain the finding on the ovaries, but it is difficult to apply to other retroperitoneal organs [31]. Alternatively, Rosenthal suggests the migration of splenic cells along the dorsal mesentery [31]. According to Rosenthal et al., the larger proportion of left-sided findings could be explained by the migration of splenic cells after the beginning of the rotation of the digestive tract, i.e., at the end of the fifth and during the sixth week [31]. Later, Gouw et al. correctly pointed out in the discussion of their paper the need for the migration of primordial germ cells through the dorsal mesentery to reach the urogenital ridge [25].

In the context of the above facts, we offer an interpretation of our own finding. In our case, with histologically proven splenic tissue within the right adrenal gland, we primarily ruled out the possibility of splenosis, as there was no splenic trauma or splenectomy in the patient’s history (note the intact spleen in Figure 2a and c). We therefore considered our finding to be a congenital heterotopy. Accessory spleens in the right suprarenal space misinterpreted and removed as retroperitoneal neoplasms have been published, but these cases do not mention a direct relationship of splenic tissue to the adrenal gland [18,19,20]. We have not found any previous mention of spleno-adrenal fusion in the literature. We therefore believe that our patient is the first case of spleno-adrenal fusion to be documented using modern imaging methods. From published theories of how spleno-adrenal fusion in the right adrenal gland occurred, we can rule out the theories of Sneath and Hochstetter [40,42]. The only possible way is the migration of splenic cells along the dorsal mesogastrium after the beginning of the rotation of the digestive tract, as described by Rosenthal [31]. In general, we believe that the cause of retroperitoneal spleno-visceral fusions (with the exception of spleno-pancreatic fusions, which can be explained by the proximity of both organs in the dorsal mesentery) is splenic cell migration, together with primitive germ cells at the end of the fifth and during the sixth week (Figure 3). This theory possibly explains the different frequency of splenic fusion with different retroperitoneal organs, i.e., in most cases splenic cells arrive in the area of the genital ridge together with primitive germ cells (dozens to hundreds of described cases), a small number arrive in the area of the mesonephros (about 13 described cases), and only very rarely do they arrive in the adrenal area (three reported cases of an accessory spleen in the right retroperitoneum and our single case of spleno-adrenal fusion). The time of the migration of primitive germ cells also corresponds to the beginning of the rotation of the digestive tract and mesogastrium, which explains the mostly left-sided findings. The reason why splenic cells follow primitive germ cells still remains unclear.

3.7 Imaging diagnosis of splenic heterotopy

Spleno-renal and discontinuous spleno-gonadal fusion are usually mistaken for a potentially malignant kidney or testicular tumor, as splenic heterotopy in these organs is a very rare condition and the finding of imaging methods is nonspecific. Also in our case of spleno-adrenal fusion, the lesion was evaluated as an indeterminate adrenal mass and there was a high probability of metastatic adrenal involvement when a renal cell carcinoma was suspected. For spleno-pancreatic fusion or an intrapancreatic accessory spleen, which is relatively more common than other fusions, criteria have been proposed to distinguish the splenic tissue from tumors of the pancreatic tail [23,43]. In the case of splenosis, there is a diagnostic clue of splenic injury or splenectomy in a patient’s history. If splenic tissue heterotopy or splenosis is suspected, 99m Technetium heat-damaged red blood cell scintigraphy combined with single-photon emission CT is the method of choice to confirm the diagnosis, as it offers excellent specificity [44]. It is also well-established in distinguishing an intrapancreatic accessory spleen from pancreatic tumors [45,46,47].

4 Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of spleno-adrenal fusion. We believe that the cause of retroperitoneal spleno-visceral fusions is the anomalous migration of spleen cells along the dorsal mesentery to the urogenital ridge, together with primitive germ cells, at the end of the fifth and during the sixth week of embryonic age. This theory explains the possible origin of spleno-visceral fusions, their different frequencies of occurrence, and the predominance of findings on the left side. We believe that spleno-adrenal fusion is an extremely rare anomaly and could not be predicted a priori. In similar conditions that are more common in clinical practice, such as splenosis or accessory spleens mimicking a neoplastic lesion, the suspicion may be confirmed by 99m Technetium heat-damaged red blood cell scintigraphy combined with single-photon emission CT.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our thanks to Zdeňka Malínská for creating an embryonic scheme. The study was supported by the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (grant number 17-31847A) and Palacky University in Olomouc (grant number IGA_LF_2020_012).

-

Conflict of interest: None declared.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Boni A, Cochetti G, Ascani S, Del Zingaro M, Quadrini F, Paladini A, et al. Robotic treatment of oligometastatic kidney tumor with synchronous pancreatic metastasis: case report and review of the literature. BMC Surg. 2018;18:40. 10.1186/s12893-018-0371-x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[2] Cochetti G, Puxeddu E, Zingaro MD, D’Amico F, Cottini E, Barillaro F, et al. Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy of thyroid cancer metastasis: case report and review of the literature. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:355–60. 10.2147/OTT.S37402.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[3] Pansadoro A, Cochetti G, D’amico F, Barillaro F, Del Zingaro M, Mearini E. Retroperitoneal laparoscopic renal tumour enucleation with local hypotension on demand. World J Urol. 2015;33:427–32. 10.1007/s00345-014-1325-2.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Canfield S, Dabestani S, Hofmann F, Hora M, et al. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: 2014 update. Eur Urol. 2015;67:913–24. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.01.005.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[5] Cochetti G, Cocca D, Maddonni S, Paladini A, Sarti E, Stivalini D, et al. Combined Robotic surgery for double renal masses and prostate cancer: myth or reality? Medicina. 2020;56:318. 10.3390/medicina56060318.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Su H, Huang X, Zhou W, Dai J, Huang B, Cao W, et al. Pathologic analysis, diagnosis and treatment of adrenal myelolipoma. Can Urol Assoc J. 2014;8:E637–40. 10.5489/cuaj.422.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Gayer G, Zissin R, Apter S, Atar E, Portnoy O, Itzchak YCT. Findings in congenital anomalies of the spleen. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:767–72. 10.1259/bjr.74.884.740767.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[8] Felice M, Tourojman M, Rogers C. Right retroperitoneal splenosis presenting as an adrenal mass. Urol Case Rep. 2017;16:44–5. 10.1016/j.eucr.2017.08.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Xia Z, Zhou Z, Shang Z, Ji Z, Yan W. An unusual right-sided suprarenal accessory spleen misdiagnosed as an atypical pheochromocytoma. Urology. 2017;110:e1–2. 10.1016/j.urology.2017.08.022.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Hashem A, Elbaset MA, Zahran MH, Osman Y. Simultaneous peritoneal and retroperitoneal splenosis mimics metastatic right adrenal mass. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;49:30–3. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2018.05.015.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Moore KL, Persaud TVN, Torchia MG. Alimentary system. The developing human, 10th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016. p. 209–82.Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Unver Dogan N, Uysal II, Demirci S, Dogan KH, Kolcu G. Accessory spleens at autopsy. Clin Anat. 2011;24:757–62. 10.1002/ca.21146.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Sánchez-Paniagua I, Baleato-González S, García-Figueiras R. Splenosis: non-invasive diagnosis of a great mimicker. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2016;108:40–1.Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Yildiz AE, Ariyurek MO, Karcaaltincaba M. Splenic anomalies of shape, size, and location: Pictorial essay. Sci World J. 2013;2013:321810. 10.1155/2013/321810.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Tsuchiya N, Sato K, Shimoda N, Satoh S, Habuchi T, Ogawa O, et al. An accessory spleen mimicking a nonfunctional adrenal tumor: a potential pitfall in the diagnosis of a left adrenal tumor. UIN. 2000;65:226–8. 10.1159/000064885.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[16] Chen C-H, Wu H-C, Chang C-H. An accessory spleen mimics a left adrenal carcinoma. Med Gen Med. 2005;7:9.Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Porwal R, Singh A, Jain P. Retroperitoneal accessory spleen presented as metastatic suprarenal tumour – a diagnostic dilemma. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:PD07–8. 10.7860/JCDR/2015/13229.6120.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Kim MK, Im CM, Oh SH, Kwon DD, Park K, Ryu SB. Unusual presentation of right-side accessory spleen mimicking a retroperitoneal tumor. Int J Urol. 2008;15:739–40. 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02078.x.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Arra A, Ramdass MJ, Mohammed A, Okoye O, Thomas D, Barrow S. Giant accessory right-sided suprarenal spleen in thalassaemia. Case Rep Pathol. 2013;2013:269543. 10.1155/2013/269543.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Zhou J-S, Hu H-P, Chen Y-Y, Yu J-D. Rare presentation of a right retroperitoneal accessory spleen: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2015;10:2400–2. 10.3892/ol.2015.3622.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Jang KM, Kim SH, Lee SJ, Park MJ, Lee MH, Choi D. Differentiation of an intrapancreatic accessory spleen from a small (<3-cm) solid pancreatic tumor: value of diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Radiology. 2013;266:159–67. 10.1148/radiol.12112765.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Balli O, Karcaaltincaba M, Karaosmanoglu D, Akata D. Multidetector computed tomography diagnosis of fusion of pancreas and spleen confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:291–2. 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31817d74f7.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Yang B, Valluru B, Guo Y-R, Cui C, Zhang P, Duan W. Significance of imaging findings in the diagnosis of heterotopic spleen – an intrapancreatic accessory spleen (IPAS): case report. Med (Baltim). 2017;96:e9040. 10.1097/MD.0000000000009040.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Kanwal S, Silverman S. Splenogonadal fusion: a case report. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;146:5. 10.1093/ajcp/aqw161.005.Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Gouw ASH, Elema JD, Bink-Boelkens MThE , de Jongh HJ , ten Kate LP. The spectrum of splenogonadal fusion – case report and review of 84 reported cases. Eur J Pediatr. 1985;144:316–23. 10.1007/BF00441771.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Watson RJ. Splenogonadal fusion. Surgery. 1968;63:853–8.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Brasch J, Roscher AA. Unusual presentation on the right side of ectopic testicular spleen. Int Surg. 1987;72:233–4.Suche in Google Scholar

[28] Putschar W, Manion W. Splenicgonadal fusion. Am J Pathol. 1956;32:15–33.Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Le Roux PJ, Heddle RM. Splenogonadal fusion: Is the accepted classification system accurate? BJU Int. 2000;85:114–5. 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00410.x.Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Moore KL, Persaud TVN, Torchia MG. Urogenital system. The developing human. 10th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016. p. 241–82.Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Rosenthal JT, Bedetti CD, Labayen RF, Christy WC, Yakulis R. Right splenorenal fusion with associated hypersplenism. J Urol. 1981;126:812–4.10.1016/S0022-5347(17)54761-8Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Obley DL, Slasky BS, Bron KM. Right-sided splenorenal fusion with arteriographic, ultrasonic, and computerized tomographic correlation. Urol Radiol. 1982;4:221–5. 10.1007/BF02924051.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Hiradfar M, Zabolinejadm N, Banihashem A, Kajbafzadeh A-M. Renal splenic heterotopia with extramedullary hematopoiesis in a thalassemic patient, simulating renal neoplasm: a case report. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;29:195–7. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3180377b7f.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Rahbar M, Mardanpour S. Right side splenorenal fusion with marked extramedullary hematopoiesis, a case report. Hum Pathol Case Rep. 2018;11:76–8. 10.1016/j.ehpc.2017.09.003.Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Tordjman M, Eiss D, Dbjay J, Crosnier A, Comperat E, Correas J-M, et al. Renal pseudo-tumor related to renal splenosis: imaging features. Urology. 2018;114:e11–5. 10.1016/j.urology.2018.01.017.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Zugail AS, Ahallal Y, Comperat E-M, Guillonneau B. Splenorenal fusion mimicking renal cancer: One case report and literature review. Urol Ann. 2019;11:211–3. 10.4103/UA.UA_47_18.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Sadler TW. Urogenital system. Langmans’s medical embryology, 14th edn. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2019. p. 256–83.Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Barwick TD, Malhotra A, Webb JAW, Savage MO, Reznek RH. Embryology of the adrenal glands and its relevance to diagnostic imaging. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:953–9. 10.1016/j.crad.2005.04.006.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[39] Sadler TW. Central nervous system. Langmans’s medical embryology, 14th edn. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2019. p. 313–50.Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Sneath WA. An apparent third testicle consisting of a scrotal spleen. J Anat Physiol. 1913;47:340–2.Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Talmann IM. Nebenmilzen im nebenhoden und samenstrang. Virchows Arch path Anat. 1926;259:237–43. 10.1007/BF01890957.Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Hochstetter AV. Milzgewebe im linken ovarium des linken Individualteiles eines menschlichen thoracopagus. Virchows Arch path Anat. 1953;324:36–54. 10.1007/BF00948094.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[43] Kang B-K, Kim JH, Byun JH, Lee SS, Kim HJ, Kim SY, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI: usefulness for differentiating intrapancreatic accessory spleen and small hypervascular neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas. Acta Radiol. 2014;55:1157–65. 10.1177/0284185113513760.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Royal HD, Brown ML, Drum DE, Nagle CE, Sylvester JM, Ziessman HA. Procedure guideline for hepatic and splenic imaging. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:114–5.Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Werner C, Winkens T, Freesmeyer M. Splenic scintigraphy for further differentiation of unclear 68Ga-DOTATOC-PET/CT findings: strengths and limitations. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2016;60:365–9. 10.1111/1754-9485.12464.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Bhutiani N, Egger ME, Doughtie CA, Burkardt ES, Scoggins CR, Martin RCG, et al. Intrapancreatic accessory spleen (IPAS): a single-institution experience and review of the literature. Am J Surg. 2017;213:816–20. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.11.030.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Li B-Q, Xu X-Q, Guo J-C. Intrapancreatic accessory spleen: a diagnostic dilemma. HPB. 2018;20:1004–11. 10.1016/j.hpb.2018.04.004.Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Zbyněk Tüdös et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells

- Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 in healthy paediatric population

- Algorithm of rational approach to reconstruction in Fournier’s disease

- A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury

- Src-1 and SP2 promote the proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Dexmedetomidine may decrease the bupivacaine toxicity to heart

- Hypoxia stimulates the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma via up-regulating the NUSAP1 expression

- Long noncoding RNA XIST knockdown relieves the injury of microglia cells after spinal cord injury by sponging miR-219-5p

- External fixation via the anterior inferior iliac spine for proximal femoral fractures in young patients

- miR-128-3p reduced acute lung injury induced by sepsis via targeting PEL12

- HAGLR promotes neuron differentiation through the miR-130a-3p-MeCP2 axis

- Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 is elevated in serum of patients with heart failure and correlates with the disease severity and patient’s prognosis

- Cell population data in identifying active tuberculosis and community-acquired pneumonia

- Prognostic value of microRNA-4521 in non-small cell lung cancer and its regulatory effect on tumor progression

- Mean platelet volume and red blood cell distribution width is associated with prognosis in premature neonates with sepsis

- 3D-printed porous scaffold promotes osteogenic differentiation of hADMSCs

- Association of gene polymorphisms with women urinary incontinence

- Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels of urologic patients

- miR-496 inhibits proliferation via LYN and AKT pathway in gastric cancer

- miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development

- Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- Fluorescent light energy modulates healing in skin grafted mouse model

- Silencing CDK6-AS1 inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory damage in HK-2 cells

- Predictive effect of DCE-MRI and DWI in brain metastases from NSCLC

- Severe postoperative hyperbilirubinemia in congenital heart disease

- Baicalin improves podocyte injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

- Clinical factors predicting ureteral stent failure in patients with external ureteral compression

- Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway

- Triple-Endobutton and clavicular hook: A propensity score matching analysis

- Long noncoding RNA MIAT inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy and the activation of NF-κB pathway in high glucose-treated renal tubular epithelial cells by the miR-182-5p/GPRC5A axis

- Serum exosomal miR-122-5p, GAS, and PGR in the non-invasive diagnosis of CAG

- miR-513b-5p inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells by targeting TRIB1

- Fer exacerbates renal fibrosis and can be targeted by miR-29c-3p

- The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-92a in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prognostic value of α2δ1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study

- No significant benefit of moderate-dose vitamin C on severe COVID-19 cases

- circ_0000467 promotes the proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating KLF12 expression by sponging miR-4766-5p

- Downregulation of RAB7 and Caveolin-1 increases MMP-2 activity in renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxic conditions

- Educational program for orthopedic surgeons’ influences for osteoporosis

- Expression and function analysis of CRABP2 and FABP5, and their ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

- lncRNA-ZFAS1 promotes the progression of endometrial carcinoma by targeting miR-34b to regulate VEGFA expression

- Anticoagulation is the answer in treating noncritical COVID-19 patients

- Effect of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis on PFS after haplo-PBSCT

- Comparison of Dako HercepTest and Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2 (4B5) tests and their correlation with silver in situ hybridization in lung adenocarcinoma

- VSTM1 regulates monocyte/macrophage function via the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Comparison of vaginal birth outcomes in midwifery-led versus physician-led setting: A propensity score-matched analysis

- Treatment of osteoporosis with teriparatide: The Slovenian experience

- New targets of morphine postconditioning protection of the myocardium in ischemia/reperfusion injury: Involvement of HSP90/Akt and C5a/NF-κB

- Superenhancer–transcription factor regulatory network in malignant tumors

- β-Cell function is associated with osteosarcopenia in middle-aged and older nonobese patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study

- Clinical features of atypical tuberculosis mimicking bacterial pneumonia

- Proteoglycan-depleted regions of annular injury promote nerve ingrowth in a rabbit disc degeneration model

- Effect of electromagnetic field on abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- miR-150-5p affects AS plaque with ASMC proliferation and migration by STAT1

- MALAT1 promotes malignant pleural mesothelioma by sponging miR-141-3p

- Effects of remifentanil and propofol on distant organ lung injury in an ischemia–reperfusion model

- miR-654-5p promotes gastric cancer progression via the GPRIN1/NF-κB pathway

- Identification of LIG1 and LIG3 as prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer

- MitoQ inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis by enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy

- Dissecting role of founder mutation p.V727M in GNE in Indian HIBM cohort

- circATP2A2 promotes osteosarcoma progression by upregulating MYH9

- Prognostic role of oxytocin receptor in colon adenocarcinoma

- Review Articles

- The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Efficacy and safety of therapeutic plasma exchange in stiff person syndrome

- Role of cesarean section in the development of neonatal gut microbiota: A systematic review

- Small cell lung cancer transformation during antitumor therapies: A systematic review

- Research progress of gut microbiota and frailty syndrome

- Recommendations for outpatient activity in COVID-19 pandemic

- Rapid Communication

- Disparity in clinical characteristics between 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia and leptospirosis

- Use of microspheres in embolization for unruptured renal angiomyolipomas

- COVID-19 cases with delayed absorption of lung lesion

- A triple combination of treatments on moderate COVID-19

- Social networks and eating disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Letter

- COVID-19, WHO guidelines, pedagogy, and respite

- Inflammatory factors in alveolar lavage fluid from severe COVID-19 pneumonia: PCT and IL-6 in epithelial lining fluid

- COVID-19: Lessons from Norway tragedy must be considered in vaccine rollout planning in least developed/developing countries

- What is the role of plasma cell in the lamina propria of terminal ileum in Good’s syndrome patient?

- Case Report

- Rivaroxaban triggered multifocal intratumoral hemorrhage of the cabozantinib-treated diffuse brain metastases: A case report and review of literature

- CTU findings of duplex kidney in kidney: A rare duplicated renal malformation

- Synchronous primary malignancy of colon cancer and mantle cell lymphoma: A case report

- Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography and pathologic characters of CD68 positive cell in primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: A case report and literature review

- Persistent SARS-CoV-2-positive over 4 months in a COVID-19 patient with CHB

- Pulmonary parenchymal involvement caused by Tropheryma whipplei

- Mediastinal mixed germ cell tumor: A case report and literature review

- Ovarian female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin – Case report

- Rare paratesticular aggressive angiomyxoma mimicking an epididymal tumor in an 82-year-old man: Case report

- Perimenopausal giant hydatidiform mole complicated with preeclampsia and hyperthyroidism: A case report and literature review

- Primary orbital ganglioneuroblastoma: A case report

- Primary aortic intimal sarcoma masquerading as intramural hematoma

- Sustained false-positive results for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M: A case report and literature review

- Peritoneal loose body presenting as a hepatic mass: A case report and review of the literature

- Chondroblastoma of mandibular condyle: Case report and literature review

- Trauma-induced complete pacemaker lead fracture 8 months prior to hospitalization: A case report

- Primary intradural extramedullary extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PIEES/PNET) of the thoracolumbar spine: A case report and literature review

- Computer-assisted preoperative planning of reduction of and osteosynthesis of scapular fracture: A case report

- High quality of 58-month life in lung cancer patient with brain metastases sequentially treated with gefitinib and osimertinib

- Rapid response of locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma to apatinib: A case report

- Retrieval of intrarenal coiled and ruptured guidewire by retrograde intrarenal surgery: A case report and literature review

- Usage of intermingled skin allografts and autografts in a senior patient with major burn injury

- Retraction

- Retraction on “Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappa B pathway”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part I

- An artificial immune system with bootstrap sampling for the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial cancers

- Breast cancer recurrence prediction with ensemble methods and cost-sensitive learning

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells

- Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 in healthy paediatric population

- Algorithm of rational approach to reconstruction in Fournier’s disease

- A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury

- Src-1 and SP2 promote the proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Dexmedetomidine may decrease the bupivacaine toxicity to heart

- Hypoxia stimulates the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma via up-regulating the NUSAP1 expression

- Long noncoding RNA XIST knockdown relieves the injury of microglia cells after spinal cord injury by sponging miR-219-5p

- External fixation via the anterior inferior iliac spine for proximal femoral fractures in young patients

- miR-128-3p reduced acute lung injury induced by sepsis via targeting PEL12

- HAGLR promotes neuron differentiation through the miR-130a-3p-MeCP2 axis

- Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 is elevated in serum of patients with heart failure and correlates with the disease severity and patient’s prognosis

- Cell population data in identifying active tuberculosis and community-acquired pneumonia

- Prognostic value of microRNA-4521 in non-small cell lung cancer and its regulatory effect on tumor progression

- Mean platelet volume and red blood cell distribution width is associated with prognosis in premature neonates with sepsis

- 3D-printed porous scaffold promotes osteogenic differentiation of hADMSCs

- Association of gene polymorphisms with women urinary incontinence

- Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels of urologic patients

- miR-496 inhibits proliferation via LYN and AKT pathway in gastric cancer

- miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development

- Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- Fluorescent light energy modulates healing in skin grafted mouse model

- Silencing CDK6-AS1 inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory damage in HK-2 cells

- Predictive effect of DCE-MRI and DWI in brain metastases from NSCLC

- Severe postoperative hyperbilirubinemia in congenital heart disease

- Baicalin improves podocyte injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

- Clinical factors predicting ureteral stent failure in patients with external ureteral compression

- Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway

- Triple-Endobutton and clavicular hook: A propensity score matching analysis

- Long noncoding RNA MIAT inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy and the activation of NF-κB pathway in high glucose-treated renal tubular epithelial cells by the miR-182-5p/GPRC5A axis

- Serum exosomal miR-122-5p, GAS, and PGR in the non-invasive diagnosis of CAG

- miR-513b-5p inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells by targeting TRIB1

- Fer exacerbates renal fibrosis and can be targeted by miR-29c-3p

- The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-92a in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prognostic value of α2δ1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study

- No significant benefit of moderate-dose vitamin C on severe COVID-19 cases

- circ_0000467 promotes the proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating KLF12 expression by sponging miR-4766-5p

- Downregulation of RAB7 and Caveolin-1 increases MMP-2 activity in renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxic conditions

- Educational program for orthopedic surgeons’ influences for osteoporosis

- Expression and function analysis of CRABP2 and FABP5, and their ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

- lncRNA-ZFAS1 promotes the progression of endometrial carcinoma by targeting miR-34b to regulate VEGFA expression

- Anticoagulation is the answer in treating noncritical COVID-19 patients

- Effect of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis on PFS after haplo-PBSCT

- Comparison of Dako HercepTest and Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2 (4B5) tests and their correlation with silver in situ hybridization in lung adenocarcinoma

- VSTM1 regulates monocyte/macrophage function via the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Comparison of vaginal birth outcomes in midwifery-led versus physician-led setting: A propensity score-matched analysis

- Treatment of osteoporosis with teriparatide: The Slovenian experience

- New targets of morphine postconditioning protection of the myocardium in ischemia/reperfusion injury: Involvement of HSP90/Akt and C5a/NF-κB

- Superenhancer–transcription factor regulatory network in malignant tumors

- β-Cell function is associated with osteosarcopenia in middle-aged and older nonobese patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study

- Clinical features of atypical tuberculosis mimicking bacterial pneumonia

- Proteoglycan-depleted regions of annular injury promote nerve ingrowth in a rabbit disc degeneration model

- Effect of electromagnetic field on abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- miR-150-5p affects AS plaque with ASMC proliferation and migration by STAT1

- MALAT1 promotes malignant pleural mesothelioma by sponging miR-141-3p

- Effects of remifentanil and propofol on distant organ lung injury in an ischemia–reperfusion model

- miR-654-5p promotes gastric cancer progression via the GPRIN1/NF-κB pathway

- Identification of LIG1 and LIG3 as prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer

- MitoQ inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis by enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy

- Dissecting role of founder mutation p.V727M in GNE in Indian HIBM cohort

- circATP2A2 promotes osteosarcoma progression by upregulating MYH9

- Prognostic role of oxytocin receptor in colon adenocarcinoma

- Review Articles

- The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Efficacy and safety of therapeutic plasma exchange in stiff person syndrome

- Role of cesarean section in the development of neonatal gut microbiota: A systematic review

- Small cell lung cancer transformation during antitumor therapies: A systematic review

- Research progress of gut microbiota and frailty syndrome

- Recommendations for outpatient activity in COVID-19 pandemic

- Rapid Communication

- Disparity in clinical characteristics between 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia and leptospirosis

- Use of microspheres in embolization for unruptured renal angiomyolipomas

- COVID-19 cases with delayed absorption of lung lesion

- A triple combination of treatments on moderate COVID-19

- Social networks and eating disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Letter

- COVID-19, WHO guidelines, pedagogy, and respite

- Inflammatory factors in alveolar lavage fluid from severe COVID-19 pneumonia: PCT and IL-6 in epithelial lining fluid

- COVID-19: Lessons from Norway tragedy must be considered in vaccine rollout planning in least developed/developing countries

- What is the role of plasma cell in the lamina propria of terminal ileum in Good’s syndrome patient?

- Case Report

- Rivaroxaban triggered multifocal intratumoral hemorrhage of the cabozantinib-treated diffuse brain metastases: A case report and review of literature

- CTU findings of duplex kidney in kidney: A rare duplicated renal malformation

- Synchronous primary malignancy of colon cancer and mantle cell lymphoma: A case report

- Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography and pathologic characters of CD68 positive cell in primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: A case report and literature review

- Persistent SARS-CoV-2-positive over 4 months in a COVID-19 patient with CHB

- Pulmonary parenchymal involvement caused by Tropheryma whipplei

- Mediastinal mixed germ cell tumor: A case report and literature review

- Ovarian female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin – Case report

- Rare paratesticular aggressive angiomyxoma mimicking an epididymal tumor in an 82-year-old man: Case report

- Perimenopausal giant hydatidiform mole complicated with preeclampsia and hyperthyroidism: A case report and literature review

- Primary orbital ganglioneuroblastoma: A case report

- Primary aortic intimal sarcoma masquerading as intramural hematoma

- Sustained false-positive results for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M: A case report and literature review

- Peritoneal loose body presenting as a hepatic mass: A case report and review of the literature

- Chondroblastoma of mandibular condyle: Case report and literature review

- Trauma-induced complete pacemaker lead fracture 8 months prior to hospitalization: A case report

- Primary intradural extramedullary extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PIEES/PNET) of the thoracolumbar spine: A case report and literature review

- Computer-assisted preoperative planning of reduction of and osteosynthesis of scapular fracture: A case report

- High quality of 58-month life in lung cancer patient with brain metastases sequentially treated with gefitinib and osimertinib

- Rapid response of locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma to apatinib: A case report

- Retrieval of intrarenal coiled and ruptured guidewire by retrograde intrarenal surgery: A case report and literature review

- Usage of intermingled skin allografts and autografts in a senior patient with major burn injury

- Retraction

- Retraction on “Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappa B pathway”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part I

- An artificial immune system with bootstrap sampling for the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial cancers

- Breast cancer recurrence prediction with ensemble methods and cost-sensitive learning