Abstract

Mitophagy affects the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). Mitochondria-targeted ubiquinone (MitoQ) is a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant that reduces the production of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). However, its relationship with mitophagy remains unclear. This study evaluated mitophagy during HSC activation and the effects of MitoQ on mitophagy in cell culture and in an animal model of the activation of HSCs. We found that MitoQ reduced the activation of HSCs and alleviated hepatic fibrosis. PINK1 (PTEN-induced putative kinase 1) is a putative serine/threonine kinase located in the mitochondria’s outer membrane. While the activation of primary HSCs or LX-2 cells was associated with reduced PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy, MitoQ reduced intracellular ROS levels, enhanced PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy, and inhibited the activation of HSCs. After knocking down the key mitophagy-related protein, PINK1, in LX-2 cells to block mitophagy, MitoQ intervention failed to inhibit HSC activation. Our results showed that MitoQ inhibited the activation of HSCs and alleviated hepatic fibrosis by enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy.

1 Introduction

Hepatic fibrosis is a common scarring response to chronic liver injury caused by various etiological factors, including viral hepatitis, alcohol abuse, autoimmune hepatitis, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. The degree of fibrosis is measured by semiquantitative scoring, such as the Ishak score [1]. Activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) is a key step in the development of hepatic fibrosis. Resident HSCs become fibrogenic myofibroblast when they are activated, expressing α-SMA and producing large amounts of extracellular matrix proteins, such as collagen 1, leading to hepatic fibrosis. HSCs are activated by a variety of growth factors and cytokines, including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [2,3]. Thus, inhibiting HSC activation could be an effective strategy for treating liver fibrosis.

Mitophagy is regulated by various factors. PINK1 (PTEN-induced putative kinase 1) is a putative serine/threonine kinase located in the mitochondria’s outer membrane. The PINK1/parkin pathway is considered the most important regulatory pathway, critical for the maintenance of mitochondrial integrity and function [4]. When a mitochondrial injury occurs, PINK1 recruits parkin to the mitochondria by phosphorylating both parkin and ubiquitin. This results in the activation of parkin’s E3 ligase activity and ubiquitination of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins (e.g., TOM20 and Mfn2), which eventually leads to degradation of mitochondrial proteins and clearance of damaged mitochondria via mitophagy [5,6,7]. Studies have shown that PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy plays a role in various diseases, such as nervous system [8], cardiovascular system [9,10], renal system [11], and liver diseases [12]. Specifically, mitophagy plays a role in hepatic fibrosis. Namely, PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy is enhanced in HSCs in a hepatic fibrosis-reversal model, and the inhibition of mitophagy enhances the activation of HSCs in mice [13].

MitoQ is a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, which contains coenzyme Q10 and triphenyl phosphonium cations to allow it to enter the mitochondria and aggregate under the action of an electrochemical gradient, to reduce the generation of lipid peroxidation free radicals in the mitochondria, and to prevent lipid peroxidation [14]. MitoQ exerts a protective function in many diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and liver fibrosis [14,15,16]. Mitochondria are the main organelle that produces reactive oxygen species (ROS). A number of studies have shown the relationship between MitoQ and ROS. MitoQ alleviates liver damage by reducing ROS production [17,18]. Several studies have shown the correlation between intracellular ROS level and mitophagy [19,20,21]. Increased ROS levels stimulate mitophagy and induce cell death. While inhibition of mitophagy increases ROS levels [22], enhanced mitophagy eliminates intracellular oxidative stress and reduces ROS production [23]. MitoQ regulates ROS production. However, it is still unclear whether MitoQ regulates mitophagy. A previous study has shown that MitoQ enhances mitophagy through the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/PINK1 pathway and inhibits renal tubular epithelial-mesenchymal transition [24]. There are scarce data on MitoQ and PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy in the process of liver fibrosis. It is unclear whether MitoQ inhibits HSC activation by regulating PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy. Therefore, this study explored the relationship between MitoQ and PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy during HSC activation and the regulatory mechanism.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Design of animal experiments

Thirty-six healthy male C57BL/6 mice 4–6 weeks old were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology (Beijing, China), license number: SCXJ (Hebei Province) [1403088]. The animal experiments were conducted in the Laboratory Animal Center of Hebei Medical University. Animals were housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled facility with standard laboratory chow and ad libitum access to food and water. Hepatic fibrosis was induced using carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) [14]. These animals were randomly divided into three groups: control (Oil), model (CCl4), and intervention (CCl4 + MitoQ) groups (n = 12 animals per group). The control group was given an intraperitoneal injection of olive oil at a dose of 5 mL/kg twice a week and 5 mL/kg olive oil intragastrically once every other day for 6 weeks. The model group was intraperitoneally injected with 5 mL/kg 10% CCl4 olive oil solution (CCl4: olive oil = 1:9, v/v) twice a week to induce hepatic fibrosis and also received 5 mL/kg olive oil intragastrically once every other day for 6 weeks. The intervention group was intraperitoneally injected with 5 mL/kg 10% CCl4 olive oil solution twice a week and also received 5 mL/kg olive oil containing MitoQ (10 mg/kg; MitoQ from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) intragastrically once every other day for 6 weeks [18]. The animals were sacrificed 3 days after the final injection. All animals were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of phenobarbital (50 mg/kg), and their sera and livers were harvested. The animals were sacrificed by exsanguination, heartbeats were assessed to determine death, and adequate humanitarian care was given.

2.2 Serum aminotransferase activity

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) activities were determined by ALT and AST assay kits in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (Changchun Huili Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China).

2.3 Isolation and culture of primary HSCs

HSCs were isolated from C57BL/6 mice as previously described [25,26]. Briefly, the portal vein was cannulated with a 26-gauge needle. The liver was first perfused with an EGTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich) and then with collagenase and pronase (Gibco BRL, Gathersburg, MD, USA). The primary HSCs were isolated by Percoll density gradient centrifugation and, subsequently, cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 1 day. The HSCs were identified by their property that newly isolated HSCs emitted blue-green fluorescence when excited by the ultraviolet light of 328 nm, which decreased within a few seconds. After 24 h of incubation, the medium was replaced with DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% FBS; at this time, the cell debris and nonadherent cells were removed by washing, and HSCs culture was 90% pure. After 3 days in culture, the cells were harvested for the subsequent experiments.

2.4 Morphology and immunohistochemical analyses of liver tissues

The livers were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, followed by embedding in paraffin, and sliced into 5-μm sections. Next, the sections were stained with H&E for morphological evaluation. Quantification of inflammation and necrosis was performed by a “blinded” liver pathologist, using a scale from 0 to 3 [27]. Immunohistochemical staining for α-SMA was performed as previously described [28]. Briefly, after deparaffinization, sodium citrate buffer was used for antigen retrieval. Subsequently, the slides were immersed in 3% hydrogen peroxide solution for 10 min, followed by incubation with 10% goat serum for 10 min. The sections were incubated with α-SMA antibodies (Cat. no. CY5295, 1:200, Shanghai Abways Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) at 4°C overnight. After that, the slides were washed with PBS, incubated with secondary antibody (#SP-9001; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China) and DAB chromogen (#ZLI-9018; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China), stained with hematoxylin, and sealed. Staining intensities were quantified by measuring the positive area using ImageJ software. Masson staining was used for the assessment of collagen. Collagen deposition was quantified by measuring the positive area using ImageJ software. The degree of fibrosis was measured by semiquantitative scoring – the Ishak score [1].

2.5 Cell cultures

LX-2 Human Hepatic Stellate Cell Line (Cat. no. SCC064) was purchased from Merck. The LX-2 was cultured in DMEM (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD, USA) containing 10% FBS in an incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37°C.

2.6 Measurement of intracellular ROS levels

Intracellular ROS levels were determined using a ROS Assay Kit (#S0033S, Beyotime, China). LX-2 cells from each treatment group were incubated in DMEM mixed with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min. Next, they were washed three times in DMEM. The fluorescence was quantified using a fluorescence microplate reader with excitation and emission settings at 488 and 525 nm, respectively (BioTek, Biotek Winooski, Vermont, USA).

2.7 Western blot analysis

The primary HSCs and human LX-2 cells were treated with RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 1 mmol/L phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF: Sigma-Aldrich), vertexed, and centrifuged to collect the supernatant. The protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using the Bradford assay. The western blot analysis was performed as previously described [29]. The following primary antibodies were used in this study: rabbit anti-α-SMA (Cat. no. CY5295, 1:1,000, Abways), rabbit anti-collagen 1 (Cat. no. AF7001, 1:300, Affinity Biosciences, OH, USA), rabbit anti-PINK1 (Cat. no. DF7742, 1:500, Affinity), rabbit anti-parkin (Cat. no. sc-32282, 1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), rabbit anti-P-parkin (Cat. no. AF3500, 1:500, Affinity), rabbit anti-TOM20 (Cat. no. ab186735, 1:1,000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and GAPDH (Cat. no. AF7021, 1:5,000, Affinity). The immunoreactive bands were visualized using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Nebraska, USA). For protein quantification, the bands were scanned and quantified using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Datacell, UK).

2.8 siRNAs transfection

The small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were synthesized by Gene Pharma (Shanghai China). and included the following sequences for PINK1: 5′-GGA GCA GUC ACU UAC AGA ATT-3′and 5′-UUC UGU AAG UGA CUG CUC CTT-3′. The negative control (NC) sequences were 5′-UUC UCC GAA CGU GUC ACG UTT-3′ and 5′-ACG UGA CAC GUU CGG AGA ATT-3′. Briefly, when the LX-2 cells were 60% confluent in the plate, we added the diluted siRNA to diluted RNAiMAX reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and incubated for 5 minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, added to cells and incubate for 6 h at 37°C. After that, we replaced the serum-free DMEM with DMEM containing 10% FBS and incubate it for 24 h. Then, the cells were divided into the following treatment groups: si-NC, si-NC + MitoQ (MitoQ 2 ng/mL), si-PINK1, and si-PINK1 + MitoQ (MitoQ 2 ng/mL). Every group incubated 24 h with serum-free DMEM to synchronization then MitoQ was added and incubated for 24 h.

2.9 Statistical analysis

The measurement data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (x ± SD). SPSS 16.0 software (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis. Differences of means between multiple groups were compared by one-way ANOVA and the least significant difference (LSD) test. Differences of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

-

Ethical approval: The research related to animal use has complied with all the relevant national regulations and institutional policies for the care and use of animals (2021-AE003).

3 Results

3.1 MitoQ inhibits mouse liver fibrosis

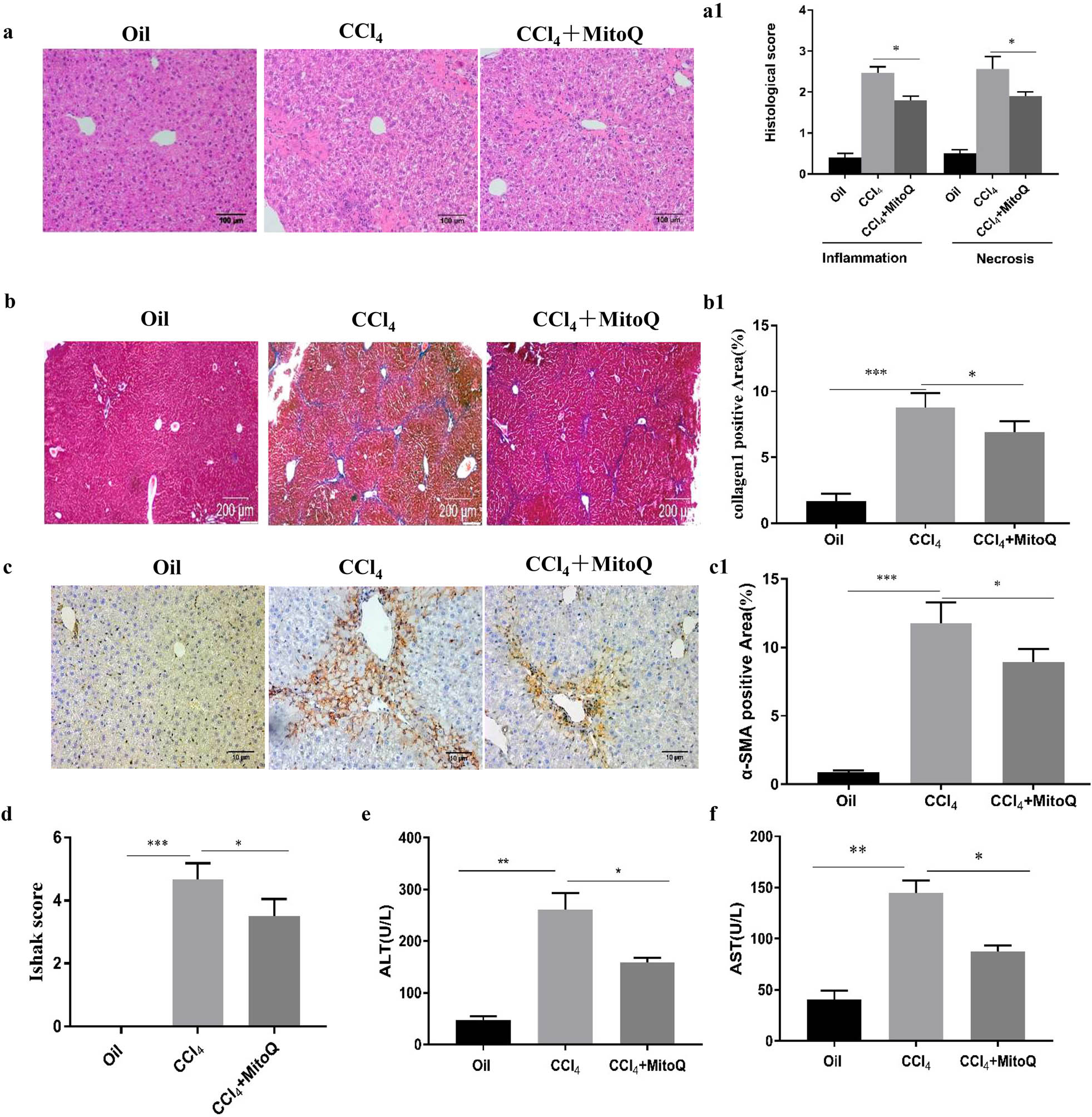

To evaluate the effects of MitoQ on hepatic fibrosis, we established a model of CCL4-induced hepatic fibrosis [13]. Hepatic damage was assessed by morphological analysis of H&E-stained slides. Fibrosis degree was assessed by Masson’s trichrome staining and immunohistochemical staining for α-SMA. The liver sections showed inflammation and necrosis in the model group, which was alleviated by MitoQ intervention (Figure 1a and a1). Masson’s trichrome staining showed significant proliferation and deposition of the collagen fibers in the model group, which was reverted after MitoQ intervention (Figure 1b and b1). Results of α-SMA immunohistochemistry showed increased α-SMA expression in the model group, whereas MitoQ intervention significantly reduced the α-SMA expression (Figure 1c and c1). The Ishak scores of the mice injected with CCl4 were significantly higher than those of the oil-treated mice. However, after treatment with MitoQ, the CCl4-injected mice had significantly reduced Ishak scores (Figure 1d), suggesting that MitoQ intervention inhibited collagen secretion in mouse livers with fibrosis. Serum ALT and AST levels were significantly higher in the model group than in the oil group. MitoQ intervention significantly reduced the ALT and AST levels (Figure 1e and f). These findings showed that MitoQ alleviated liver damage and liver fibrosis.

MitoQ inhibits mouse hepatic fibrosis. (a) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining of liver tissue (100× magnification). (a1) Quantification of liver inflammation and injury was performed. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. *P < 0.05 indicates significant differences relative to the indicated groups; (n = 6). (b) Masson’s trichrome staining of the liver tissue (40× magnification); (n = 6). (b1) Columns represent the percentage of positive area of collagen fibers. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 (n = 6). (c) Immunohistochemistry for α-SMA in the liver tissue (100× magnification). (c1) Columns represent the percentage of α-SMA positive area. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 (n = 6). (d) Liver fibrosis semiquantitative scoring was performed. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001; (n = 6). (e) Serum ALT levels. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (n = 6). (f) Serum AST levels. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (n = 6).

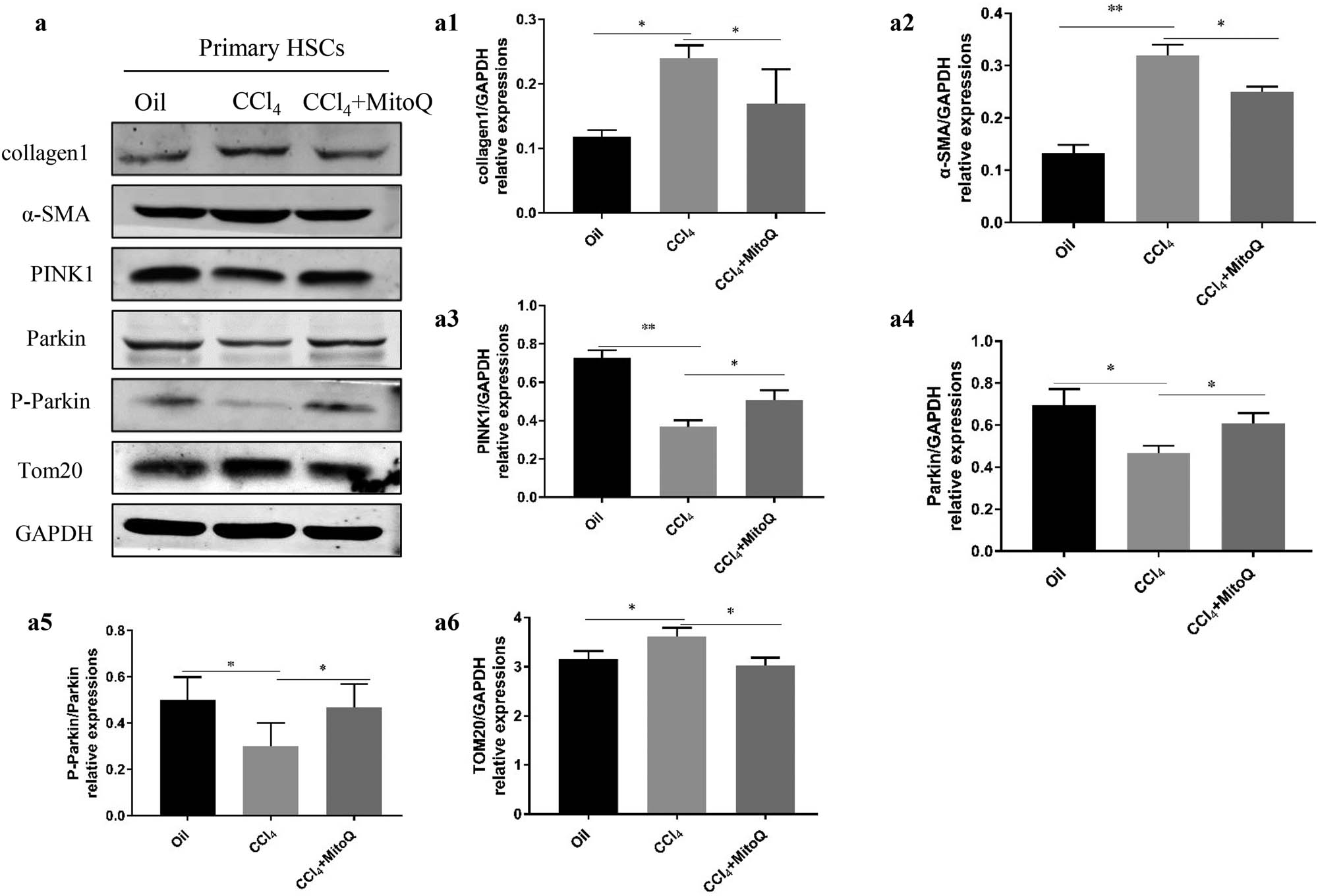

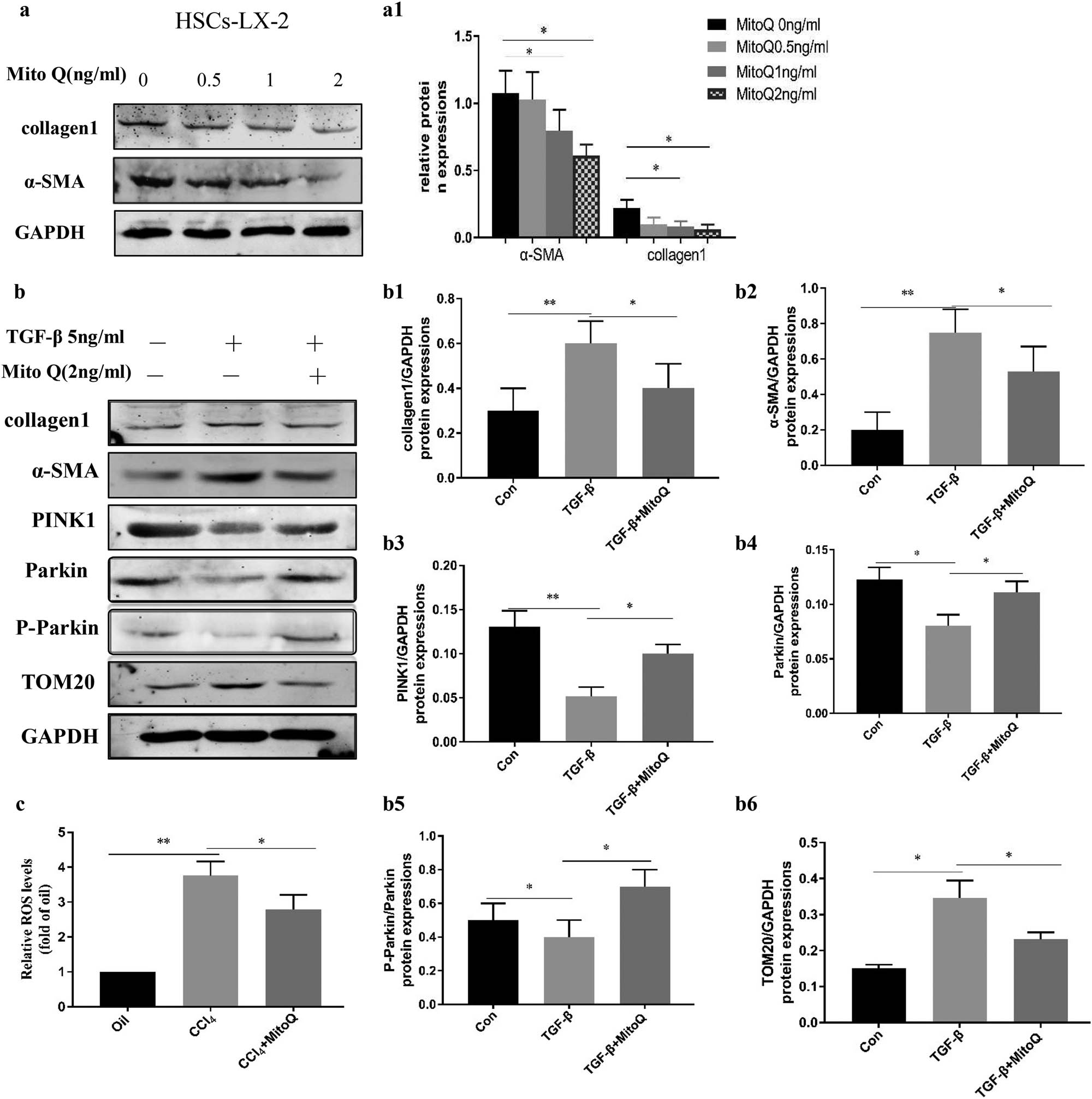

3.2 Mitophagy decreases with the activation of stellate cells, and MitoQ enhances mitophagy and reduces ROS production

PINK1 accumulates selectively on dysfunctional mitochondria, recruits parkin to the mitochondria, and activates it by phosphorylation of serine 65 on parkin. The E3 ubiquitin ligase activity of parkin targets mitochondria for degradation by autophagy and leads to mitochondrial protein TOM20 degradation [4]. Hence, PINK1, parkin, P-parkin, and TOM20 are important proteins involved in mitophagy. To study mitophagy during the activation of HSCs, primary HSCs were extracted from animals to determine the expression of mitophagy-related proteins. Our data demonstrated that the expression of α-SMA and collagen 1 (HSC activation marker proteins) was higher in the model group compared with the control group. Interestingly, expression of mitophagy-related proteins PINK1, parkin, and P-parkin was reduced, and TOM20 expression was increased in the primary HSCs of the model group, while MitoQ reverted this change (Figure 2a and a1–6). Furthermore, we used TGB-β to activate the HSC line LX-2 in vitro. The expression levels of α-SMA and collagen 1 were downregulated with increasing MitoQ concentrations in the human LX-2 cells (Figure 3a and a1). TGF-β stimulated LX-2 cells to mediate downregulation of mitophagy-related proteins PINK1, parkin, and P-parkin and increased the accumulation of α-SMA, collagen 1, and TOM20. However, MitoQ intervention increased the PINK1, parkin, and P-parkin protein expression and reduced α-SMA, collagen 1, and TOM20 expression (Figure 3b and b1–6). ROS levels were increased after TGF-β stimulation of LX-2 cells, while MitoQ intervention reduced the ROS levels (Figure 3c). Taken together, our data indicated that mitophagy was decreased with the activation of HSCs, while MitoQ enhanced the mitophagy activity of the PINK1/parkin pathway, reduced intracellular ROS levels, and inhibited LX-2 activation.

Mitophagy decreases with the activation of HSCs, and MitoQ enhances mitophagy. (a) Western blot analysis shows the collagen 1, α-SMA, PINK1, parkin, P-parkin, and TOM20 expression in the primary HSCs. (a1) Columns represent the gray-scale value of collagen 1 expression. (a2) Columns represent the gray-scale value of the α-SMA expression. (a3) Columns represent the gray-scale value of PINK1 expression. (a4) Columns represent the gray-scale value of parkin expression. (a5) Columns represent the gray-scale value of P-parkin expression. (a6) Columns represent the gray-scale value of TOM20 expression. Data show the mean ± standard deviation. Experiments were repeated three times. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01.

Mitophagy decreases with the LX-2 activation, and MitoQ enhances mitophagy and reduces ROS levels. (a) TGB-β to activate the LX-2 in vitro, Western blot analysis showing collagen 1 and α-SMA expression in LX-2 cells treated with different concentrations of MitoQ. (a1) Columns represent the gray-scale value of α-SMA and collagen 1 expression. Data show the mean ± standard deviation. Experiments were repeated three times. *P < 0.05. (b) Western blot analysis showing collagen 1, α-SMA, PINK1, parkin, P-parkin, and TOM20 expression with TGF-β stimulation and MitoQ intervention in LX-2 cells. (b1) Columns represent the gray-scale value of collagen 1 expression. (b2) Columns represent the gray-scale value of the α-SMA expression. (b3) Columns represent the gray-scale value of the PINK1 expression. (b4) Columns represent the gray-scale value of parkin expression. (b5) Columns represent the gray-scale value of P-parkin expression. (b6) Columns represent the gray-scale value of TOM20 expression. Data show the mean ± standard deviation. Experiments were repeated three times. *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01. (c) ROS probe was used to detect the levels of ROS in LX-2 cells, *P < 0.05, and **P < 0.01.

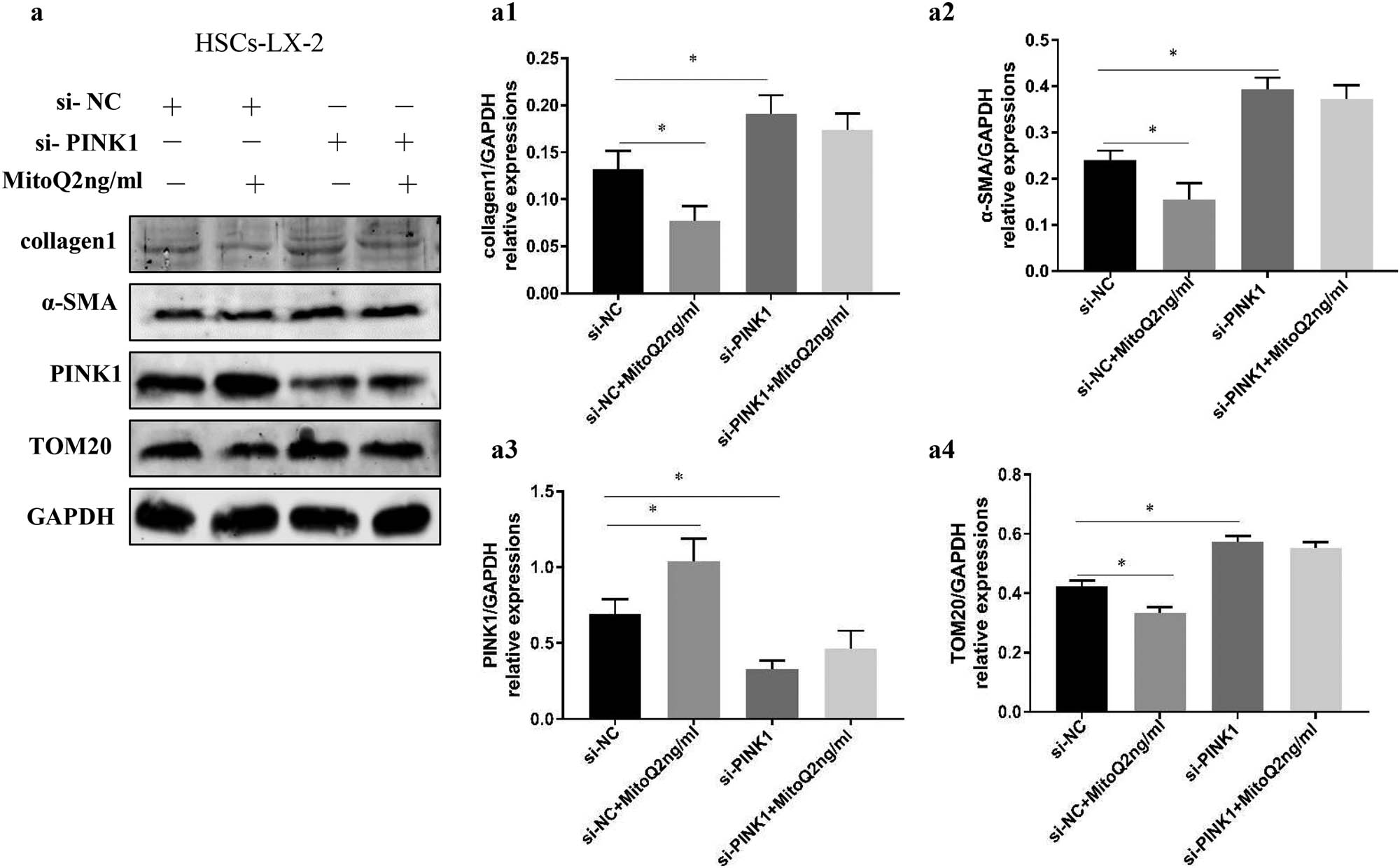

3.3 MitoQ inhibits HSC activation through enhancing mitophagy

To further test whether MitoQ inhibited HSC activation by enhancing mitophagy, PINK1 was knocked down by siRNA in LX-2 cells. The PINK1 knockdown led to an increase in α-SMA, collagen 1, and TOM20 expression, suggesting that inhibition of PINK1/parkin-induced mitophagy enhanced HSC activation and increased the number of residual mitochondria. However, after knocking down PINK1, the application of MitoQ did not reduce α-SMA and collagen 1 expression or lead to changes in TOM20 expression. These findings suggested that MitoQ reduced HSC activation by enhancing the PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy pathway (Figure 4a and a1–4).

MitoQ inhibits HSC activation by enhancing mitophagy. (a) LX-2 cells stimulated by MitoQ showed reduced α-SMA, collagen 1, and TOM20 expression (si-NC vs si-NC + MitoQ). The PINK1 knockdown to inhibit mitophagy increased the expression of α-SMA, collagen 1, and TOM20 expression in the LX-2 cells (si-NC vs si-PINK1), but the expression of α-SMA, collagen1, and TOM20 were not affected by stimulation with MitoQ (si-PINK1 vs si-PINK1 + MitoQ). (a1) Columns represent the gray-scale value of collagen 1 expression. (a2) Columns represent the gray-scale value of the α-SMA expression. (a3) Columns represent the gray-scale value of the PINK1 expression. (a4) Columns represent the gray-scale value of TOM20 expression. Data show the mean ± standard deviation. Experiments were repeated three times. *P < 0.05.

4 Discussion

PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy plays an important role in autophagy-dependent mitochondrial degradation in mammals. MitoQ is an antioxidant that specifically targets mitochondria. However, research on MitoQ and mitophagy in the process of liver fibrosis has been limited. In this study, we found that PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy was downregulated during the activation of HSCs and development of hepatic fibrosis, while MitoQ enhanced mitophagy and reduced ROS levels in the HSCs and reduced liver fibrosis.

Liver fibrosis in mice is usually induced by CCl4 administration or bile duct ligation (BDL) [30,31]. This study established a CCl4-induced hepatic fibrosis mouse model and used the Ishak score to assess the degree of fibrosis. We observed a reduced Ishak score in the MitoQ intervention group, indicating successful modeling of hepatic fibrosis, while MitoQ reduced hepatic fibrosis.

Recent studies have shown that mitophagy may participate in the pathogenesis of various liver diseases, such as viral hepatitis, liver injury, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver steatosis/fatty liver disease, and hepatic fibrosis [32]. However, studies investigating the role of mitophagy in liver fibrosis have mainly focused on hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (KCs). Melatonin protects against liver fibrosis via upregulation of mitophagy [33]. TIM‐4 interference in the KCs inhibits Akt1‐mediated ROS production, resulting in the suppression of PINK1, parkin, and LC3‐II/I activation, reduction of TGF‐β1, and attenuation of fibrosis development [34]. One study mentioned that resveratrol induces mitophagy in HSCs [35], and mitophagy was enhanced in a hepatic fibrosis-reversal model [13]. However, the effect of mitophagy on HSC survival and hepatic fibrosis was unclear. We found that PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy was downregulated during the activation of the HSCs, which is consistent with the previous studies [13,36].

Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant mitoquidone improves liver inflammation and fibrosis in rats with cirrhosis by reducing hepatic oxidative stress, preventing apoptosis, and promoting the removal of dysfunctional mitochondria. However, the research focused on hepatocytes [37]. One study reported that mitoquidone deactivates human and rat HSCs and reduces portal hypertension in rats with cirrhosis through decreased oxidative stress levels [19]. However, the relationship between MitoQ and mitophagy in HSCs has been unknown. MitoQ exerts beneficial effects on tubular injury in diabetic kidney disease via Nrf2/PINK1-mediated mitophagy [25]. Thus, we speculated that MitoQ enhanced PINK1/parkin-induced mitophagy in HSCs to reduce liver fibrosis. In this study, we found that MitoQ reduced the ROS levels, upregulated mitophagy, and deactivated LX-2 cells and primary HSCs; this was reflected in increased PINK1, parkin, and P-parkin expression, and in reduced TOM20, α-SMA, and collagen 1 expression after the MitoQ intervention in primary HSCs and LX-2 cells. This study demonstrated that MitoQ can affect HSC activation by regulating mitophagy, which has not been reported in this context previously.

5 Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrated that mitophagy is weakened during HSC activation. We propose a new mechanism that MitoQ inhibits HSC activation and plays an antifibrotic role through regulating PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy and ROS production.

-

Funding information: This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 81770601], Key Research and Development Program of Hebei Province [grant number 182777117D], and Medical Science Research of Hebei Province [grant number 20200058].

-

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;6:696–9.10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6Search in Google Scholar

[2] Radaeva S, Sun R, Jaruga B, Nguyen VT, Tian Z, Gao B. Natural killer cells ameliorate liver fibrosis by killing activated stellate cells in NKG2D-dependent and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-dependent manners. Gastroenterology. 2006;2:435–52.10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.055Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[3] Ruan W, Pan R, Shen X, Nie Y, Wu Y. CDH11 promotes liver fibrosis via activation of hepatic stellate cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;2:543–49.10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.11.153Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[4] Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Gautier CA, Shen J, et al. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010;1:e1000298.10.1371/journal.pbio.1000298Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Sha D, Chin LS, Li L. Phosphorylation of parkin by Parkinson disease-linked kinase PINK1 activates parkin E3 ligase function and NF-kappaB signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;2:352–63.10.1093/hmg/ddp501Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Vazquez-Martin A, Cufi S, Corominas-Faja B, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Vellon L, Menendez JA. Mitochondrial fusion by pharmacological manipulation impedes somatic cell reprogramming to pluripotency: new insight into the role of mitophagy in cell stemness. Aging (Albany NY). 2012;6:393–401.10.18632/aging.100465Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Han H, Tan J, Wang R, Wan H, He Y, Yan X, et al. PINK1 phosphorylates Drp1(S616) to regulate mitophagy-independent mitochondrial dynamics. EMBO Rep. 2020;8:e48686.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Shaerzadeh F, Motamedi F, Minai-Tehrani D, Khodagholi F. Monitoring of neuronal loss in the hippocampus of Aβ-injected rat: autophagy, mitophagy, and mitochondrial biogenesis stand against apoptosis. Neuromolecular Med. 2014;1:175–90.10.1007/s12017-013-8272-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[9] Givvimani S, Munjal C, Tyagi N, Sen U, Metreveli N, Tyagi SC. Mitochondrial division/mitophagy inhibitor (Mdivi) ameliorates pressure overload induced heart failure. PLoS One. 2012;3:e32388.10.1371/journal.pone.0032388Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Chaanine AH, Jeong D, Liang L, Chemaly ER, Fish K, Gordon RE, et al. JNK modulates FOXO3a for the expression of the mitochondrial death and mitophagy marker BNIP3 in pathological hypertrophy and in heart failure. Cell Death Dis. 2012;2:265.10.1038/cddis.2012.5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Ishimoto Y, Inagi R. Mitochondria: a therapeutic target in acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;7:1062–9.10.1093/ndt/gfv317Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Czaja MJ, Ding WX, Donohue TMJr, Friedman SL, Kim JS, Komatsu M, et al. Functions of autophagy in normal and diseased liver. Autophagy. 2013;8:1131–58.10.4161/auto.25063Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Ding Q, Xie XL, Wang MM, Yin J, Tian JM, Jiang XY, et al. The role of the apoptosis-related protein BCL-B in the regulation of mitophagy in hepatic stellate cells during the regression of liver fibrosis. Exp Mol Med. 2019;1:1–13.10.1038/s12276-018-0199-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Graham D, Huynh NN, Hamilton CA, Beattie E, Smith RA, Cochemé HM, et al. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ10 improves endothelial function and attenuates cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 2009;2:322–8.10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.130351Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Yin X, Manczak M, Reddy PH. Mitochondria-targeted molecules MitoQ and SS31 reduce mutant huntingtin-induced mitochondrial toxicity and synaptic damage in Huntington’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2016;9:1739–53.10.1093/hmg/ddw045Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Rehman H, Liu Q, Krishnasamy Y, Shi Z, Ramshesh VK, Haque K, et al. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ attenuates liver fibrosis in mice. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2016;1:14–27.Search in Google Scholar

[17] Mukhopadhyay P, Horváth B, Zsengellėr Z, Bátkai S, Cao Z, Kechrid M, et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation triggers inflammatory response and tissue injury associated with hepatic ischemia-reperfusion: therapeutic potential of mitochondrially targeted antioxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;5:1123–38.10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.05.036Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Vilaseca M, García-Calderó H, Lafoz E, Ruart M, López-Sanjurjo CI, Murphy MP, et al. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant mitoquinone deactivates human and rat hepatic stellate cells and reduces portal hypertension in cirrhotic rats. Liver Int. 2017;7:1002–12.10.1111/liv.13436Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[19] Basit F, van Oppen LM, Schöckel L, Bossenbroek HM. van Emst-de Vries SE, Hermeling JC, et al. Mitochondrial complex I inhibition triggers a mitophagy-dependent ROS increase leading to necroptosis and ferroptosis in melanoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2017;3:e2716.10.1038/cddis.2017.133Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Li L, Tan J, Miao Y, Lei P, Zhang Q. ROS and autophagy: interactions and molecular regulatory mechanisms. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2015;5:615–21.10.1007/s10571-015-0166-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[21] Yang X, Yan X, Yang D, Zhou J, Song J, Yang D. Rapamycin attenuates mitochondrial injury and renal tubular cell apoptosis in experimental contrast-induced acute kidney injury in rats. Biosci Rep. 2018;38:BSR20180876.10.1042/BSR20180876Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Su CJ, Shen Z, Cui RX, Huang Y, Xu DL, Zhao FL, et al. Thioredoxin-interacting protein (txnip) regulates parkin/PINK1-mediated mitophagy in dopaminergic neurons under high-glucose conditions: implications for molecular links between parkinson’s disease and diabetes. Neurosci Bull. 2020;4:346–58.10.1007/s12264-019-00459-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Levy A, Stedman A, Deutsch E, Donnadieu F, Virgin HW, Sansonetti PJ, et al. Innate immune receptor NOD2 mediates LGR5(+) intestinal stem cell protection against ROS cytotoxicity via mitophagy stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;4:1994–2003.10.1073/pnas.1902788117Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Xiao L, Xu X, Zhang F, Wang M, Xu Y, Tang D, et al. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ ameliorated tubular injury mediated by mitophagy in diabetic kidney disease via Nrf2/PINK1. Redox Biol. 2017;297–311.10.1016/j.redox.2016.12.022Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[25] Geerts A, Eliasson C, Niki T, Wielant A, Vaeyens F, Pekny M. Formation of normal desmin intermediate filaments in mouse hepatic stellate cells requires vimentin. Hepatology. 2001;1:177–88.10.1053/jhep.2001.21045Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[26] Melhem A, Muhanna N, Bishara A, Alvarez CE, Ilan Y, Bishara T, et al. Anti-fibrotic activity of NK cells in experimental liver injury through killing of activated HSC. J Hepatol. 2006;1:60–71.10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Deng YR, Ma HD, Tsuneyama K, Yang W, Wang YH, Lu FT, et al. STAT3-mediated attenuation of CCl4-induced mouse liver fibrosis by the protein kinase inhibitor sorafenib. J Autoimmun. 2013;46:25–34.10.1016/j.jaut.2013.07.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Guo Y, Ding Q, Chen L, Ji C, Hao H, Wang J, et al. Overexpression of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor mediates liver fibrosis in transgenic mice. Am J Med Sci. 2017;2:199–210.10.1016/j.amjms.2017.04.011Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[29] Ma J, Li F, Liu L, Cui D, Wu X, Jiang X, et al. Raf kinase inhibitor protein inhibits cell proliferation but promotes cell migration in rat hepatic stellate cells. Liver Int. 2009;4:567–74.10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.01981.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Gao J, Wei B, de Assuncao TM, Liu Z, Hu X, Ibrahim S, et al. Hepatic stellate cell autophagy inhibits extracellular vesicle release to attenuate liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2020;5:1144–54.10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.044Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Zhang H, Sun D, Wang G, Cui S, Field RA, Li J, et al. Alogliptin alleviates liver fibrosis via suppression of activated hepatic stellate cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;2:387–93.10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.02.065Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Ke PY. Mitophagy in the pathogenesis of liver diseases. Cells. 2020;9:831.10.3390/cells9040831Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Kang JW, Hong JM, Lee SM. Melatonin enhances mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis in rats with carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis. J Pineal Res. 2016;4:383–93.10.1111/jpi.12319Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Wu H, Chen G, Wang J, Deng M, Yuan F, Gong J. TIM-4 interference in Kupffer cells against CCL4-induced liver fibrosis by mediating Akt1/Mitophagy signalling pathway. Cell Prolif. 2020;1:e12731.10.1111/cpr.12731Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[35] Meira Martins LA, Vieira MQ, Ilha M, de Vasconcelos M, Biehl HB, Lima DB, et al. The interplay between apoptosis, mitophagy and mitochondrial biogenesis induced by resveratrol can determine activated hepatic stellate cells death or survival. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;2:657–72.10.1007/s12013-014-0245-5Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Tian Z, Chen Y, Yao N, Hu C, Wu Y, Guo D, et al. Role of mitophagy regulation by ROS in hepatic stellate cells during acute liver failure. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018;3:G374–84.10.1152/ajpgi.00032.2018Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[37] Turkseven S, Bolognesi M, Brocca A, Pesce P, Angeli P, Di Pascoli M. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant mitoquinone attenuates liver inflammation and fibrosis in cirrhotic rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2020;2:G298–304.10.1152/ajpgi.00135.2019Search in Google Scholar PubMed

© 2021 Shi-Ying Dou et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells

- Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 in healthy paediatric population

- Algorithm of rational approach to reconstruction in Fournier’s disease

- A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury

- Src-1 and SP2 promote the proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Dexmedetomidine may decrease the bupivacaine toxicity to heart

- Hypoxia stimulates the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma via up-regulating the NUSAP1 expression

- Long noncoding RNA XIST knockdown relieves the injury of microglia cells after spinal cord injury by sponging miR-219-5p

- External fixation via the anterior inferior iliac spine for proximal femoral fractures in young patients

- miR-128-3p reduced acute lung injury induced by sepsis via targeting PEL12

- HAGLR promotes neuron differentiation through the miR-130a-3p-MeCP2 axis

- Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 is elevated in serum of patients with heart failure and correlates with the disease severity and patient’s prognosis

- Cell population data in identifying active tuberculosis and community-acquired pneumonia

- Prognostic value of microRNA-4521 in non-small cell lung cancer and its regulatory effect on tumor progression

- Mean platelet volume and red blood cell distribution width is associated with prognosis in premature neonates with sepsis

- 3D-printed porous scaffold promotes osteogenic differentiation of hADMSCs

- Association of gene polymorphisms with women urinary incontinence

- Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels of urologic patients

- miR-496 inhibits proliferation via LYN and AKT pathway in gastric cancer

- miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development

- Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- Fluorescent light energy modulates healing in skin grafted mouse model

- Silencing CDK6-AS1 inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory damage in HK-2 cells

- Predictive effect of DCE-MRI and DWI in brain metastases from NSCLC

- Severe postoperative hyperbilirubinemia in congenital heart disease

- Baicalin improves podocyte injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

- Clinical factors predicting ureteral stent failure in patients with external ureteral compression

- Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway

- Triple-Endobutton and clavicular hook: A propensity score matching analysis

- Long noncoding RNA MIAT inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy and the activation of NF-κB pathway in high glucose-treated renal tubular epithelial cells by the miR-182-5p/GPRC5A axis

- Serum exosomal miR-122-5p, GAS, and PGR in the non-invasive diagnosis of CAG

- miR-513b-5p inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells by targeting TRIB1

- Fer exacerbates renal fibrosis and can be targeted by miR-29c-3p

- The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-92a in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prognostic value of α2δ1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study

- No significant benefit of moderate-dose vitamin C on severe COVID-19 cases

- circ_0000467 promotes the proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating KLF12 expression by sponging miR-4766-5p

- Downregulation of RAB7 and Caveolin-1 increases MMP-2 activity in renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxic conditions

- Educational program for orthopedic surgeons’ influences for osteoporosis

- Expression and function analysis of CRABP2 and FABP5, and their ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

- lncRNA-ZFAS1 promotes the progression of endometrial carcinoma by targeting miR-34b to regulate VEGFA expression

- Anticoagulation is the answer in treating noncritical COVID-19 patients

- Effect of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis on PFS after haplo-PBSCT

- Comparison of Dako HercepTest and Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2 (4B5) tests and their correlation with silver in situ hybridization in lung adenocarcinoma

- VSTM1 regulates monocyte/macrophage function via the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Comparison of vaginal birth outcomes in midwifery-led versus physician-led setting: A propensity score-matched analysis

- Treatment of osteoporosis with teriparatide: The Slovenian experience

- New targets of morphine postconditioning protection of the myocardium in ischemia/reperfusion injury: Involvement of HSP90/Akt and C5a/NF-κB

- Superenhancer–transcription factor regulatory network in malignant tumors

- β-Cell function is associated with osteosarcopenia in middle-aged and older nonobese patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study

- Clinical features of atypical tuberculosis mimicking bacterial pneumonia

- Proteoglycan-depleted regions of annular injury promote nerve ingrowth in a rabbit disc degeneration model

- Effect of electromagnetic field on abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- miR-150-5p affects AS plaque with ASMC proliferation and migration by STAT1

- MALAT1 promotes malignant pleural mesothelioma by sponging miR-141-3p

- Effects of remifentanil and propofol on distant organ lung injury in an ischemia–reperfusion model

- miR-654-5p promotes gastric cancer progression via the GPRIN1/NF-κB pathway

- Identification of LIG1 and LIG3 as prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer

- MitoQ inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis by enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy

- Dissecting role of founder mutation p.V727M in GNE in Indian HIBM cohort

- circATP2A2 promotes osteosarcoma progression by upregulating MYH9

- Prognostic role of oxytocin receptor in colon adenocarcinoma

- Review Articles

- The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Efficacy and safety of therapeutic plasma exchange in stiff person syndrome

- Role of cesarean section in the development of neonatal gut microbiota: A systematic review

- Small cell lung cancer transformation during antitumor therapies: A systematic review

- Research progress of gut microbiota and frailty syndrome

- Recommendations for outpatient activity in COVID-19 pandemic

- Rapid Communication

- Disparity in clinical characteristics between 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia and leptospirosis

- Use of microspheres in embolization for unruptured renal angiomyolipomas

- COVID-19 cases with delayed absorption of lung lesion

- A triple combination of treatments on moderate COVID-19

- Social networks and eating disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Letter

- COVID-19, WHO guidelines, pedagogy, and respite

- Inflammatory factors in alveolar lavage fluid from severe COVID-19 pneumonia: PCT and IL-6 in epithelial lining fluid

- COVID-19: Lessons from Norway tragedy must be considered in vaccine rollout planning in least developed/developing countries

- What is the role of plasma cell in the lamina propria of terminal ileum in Good’s syndrome patient?

- Case Report

- Rivaroxaban triggered multifocal intratumoral hemorrhage of the cabozantinib-treated diffuse brain metastases: A case report and review of literature

- CTU findings of duplex kidney in kidney: A rare duplicated renal malformation

- Synchronous primary malignancy of colon cancer and mantle cell lymphoma: A case report

- Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography and pathologic characters of CD68 positive cell in primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: A case report and literature review

- Persistent SARS-CoV-2-positive over 4 months in a COVID-19 patient with CHB

- Pulmonary parenchymal involvement caused by Tropheryma whipplei

- Mediastinal mixed germ cell tumor: A case report and literature review

- Ovarian female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin – Case report

- Rare paratesticular aggressive angiomyxoma mimicking an epididymal tumor in an 82-year-old man: Case report

- Perimenopausal giant hydatidiform mole complicated with preeclampsia and hyperthyroidism: A case report and literature review

- Primary orbital ganglioneuroblastoma: A case report

- Primary aortic intimal sarcoma masquerading as intramural hematoma

- Sustained false-positive results for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M: A case report and literature review

- Peritoneal loose body presenting as a hepatic mass: A case report and review of the literature

- Chondroblastoma of mandibular condyle: Case report and literature review

- Trauma-induced complete pacemaker lead fracture 8 months prior to hospitalization: A case report

- Primary intradural extramedullary extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PIEES/PNET) of the thoracolumbar spine: A case report and literature review

- Computer-assisted preoperative planning of reduction of and osteosynthesis of scapular fracture: A case report

- High quality of 58-month life in lung cancer patient with brain metastases sequentially treated with gefitinib and osimertinib

- Rapid response of locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma to apatinib: A case report

- Retrieval of intrarenal coiled and ruptured guidewire by retrograde intrarenal surgery: A case report and literature review

- Usage of intermingled skin allografts and autografts in a senior patient with major burn injury

- Retraction

- Retraction on “Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappa B pathway”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part I

- An artificial immune system with bootstrap sampling for the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial cancers

- Breast cancer recurrence prediction with ensemble methods and cost-sensitive learning

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells

- Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 in healthy paediatric population

- Algorithm of rational approach to reconstruction in Fournier’s disease

- A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury

- Src-1 and SP2 promote the proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Dexmedetomidine may decrease the bupivacaine toxicity to heart

- Hypoxia stimulates the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma via up-regulating the NUSAP1 expression

- Long noncoding RNA XIST knockdown relieves the injury of microglia cells after spinal cord injury by sponging miR-219-5p

- External fixation via the anterior inferior iliac spine for proximal femoral fractures in young patients

- miR-128-3p reduced acute lung injury induced by sepsis via targeting PEL12

- HAGLR promotes neuron differentiation through the miR-130a-3p-MeCP2 axis

- Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 is elevated in serum of patients with heart failure and correlates with the disease severity and patient’s prognosis

- Cell population data in identifying active tuberculosis and community-acquired pneumonia

- Prognostic value of microRNA-4521 in non-small cell lung cancer and its regulatory effect on tumor progression

- Mean platelet volume and red blood cell distribution width is associated with prognosis in premature neonates with sepsis

- 3D-printed porous scaffold promotes osteogenic differentiation of hADMSCs

- Association of gene polymorphisms with women urinary incontinence

- Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels of urologic patients

- miR-496 inhibits proliferation via LYN and AKT pathway in gastric cancer

- miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development

- Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- Fluorescent light energy modulates healing in skin grafted mouse model

- Silencing CDK6-AS1 inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory damage in HK-2 cells

- Predictive effect of DCE-MRI and DWI in brain metastases from NSCLC

- Severe postoperative hyperbilirubinemia in congenital heart disease

- Baicalin improves podocyte injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

- Clinical factors predicting ureteral stent failure in patients with external ureteral compression

- Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway

- Triple-Endobutton and clavicular hook: A propensity score matching analysis

- Long noncoding RNA MIAT inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy and the activation of NF-κB pathway in high glucose-treated renal tubular epithelial cells by the miR-182-5p/GPRC5A axis

- Serum exosomal miR-122-5p, GAS, and PGR in the non-invasive diagnosis of CAG

- miR-513b-5p inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells by targeting TRIB1

- Fer exacerbates renal fibrosis and can be targeted by miR-29c-3p

- The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-92a in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prognostic value of α2δ1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study

- No significant benefit of moderate-dose vitamin C on severe COVID-19 cases

- circ_0000467 promotes the proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating KLF12 expression by sponging miR-4766-5p

- Downregulation of RAB7 and Caveolin-1 increases MMP-2 activity in renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxic conditions

- Educational program for orthopedic surgeons’ influences for osteoporosis

- Expression and function analysis of CRABP2 and FABP5, and their ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

- lncRNA-ZFAS1 promotes the progression of endometrial carcinoma by targeting miR-34b to regulate VEGFA expression

- Anticoagulation is the answer in treating noncritical COVID-19 patients

- Effect of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis on PFS after haplo-PBSCT

- Comparison of Dako HercepTest and Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2 (4B5) tests and their correlation with silver in situ hybridization in lung adenocarcinoma

- VSTM1 regulates monocyte/macrophage function via the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Comparison of vaginal birth outcomes in midwifery-led versus physician-led setting: A propensity score-matched analysis

- Treatment of osteoporosis with teriparatide: The Slovenian experience

- New targets of morphine postconditioning protection of the myocardium in ischemia/reperfusion injury: Involvement of HSP90/Akt and C5a/NF-κB

- Superenhancer–transcription factor regulatory network in malignant tumors

- β-Cell function is associated with osteosarcopenia in middle-aged and older nonobese patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study

- Clinical features of atypical tuberculosis mimicking bacterial pneumonia

- Proteoglycan-depleted regions of annular injury promote nerve ingrowth in a rabbit disc degeneration model

- Effect of electromagnetic field on abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- miR-150-5p affects AS plaque with ASMC proliferation and migration by STAT1

- MALAT1 promotes malignant pleural mesothelioma by sponging miR-141-3p

- Effects of remifentanil and propofol on distant organ lung injury in an ischemia–reperfusion model

- miR-654-5p promotes gastric cancer progression via the GPRIN1/NF-κB pathway

- Identification of LIG1 and LIG3 as prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer

- MitoQ inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis by enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy

- Dissecting role of founder mutation p.V727M in GNE in Indian HIBM cohort

- circATP2A2 promotes osteosarcoma progression by upregulating MYH9

- Prognostic role of oxytocin receptor in colon adenocarcinoma

- Review Articles

- The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Efficacy and safety of therapeutic plasma exchange in stiff person syndrome

- Role of cesarean section in the development of neonatal gut microbiota: A systematic review

- Small cell lung cancer transformation during antitumor therapies: A systematic review

- Research progress of gut microbiota and frailty syndrome

- Recommendations for outpatient activity in COVID-19 pandemic

- Rapid Communication

- Disparity in clinical characteristics between 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia and leptospirosis

- Use of microspheres in embolization for unruptured renal angiomyolipomas

- COVID-19 cases with delayed absorption of lung lesion

- A triple combination of treatments on moderate COVID-19

- Social networks and eating disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Letter

- COVID-19, WHO guidelines, pedagogy, and respite

- Inflammatory factors in alveolar lavage fluid from severe COVID-19 pneumonia: PCT and IL-6 in epithelial lining fluid

- COVID-19: Lessons from Norway tragedy must be considered in vaccine rollout planning in least developed/developing countries

- What is the role of plasma cell in the lamina propria of terminal ileum in Good’s syndrome patient?

- Case Report

- Rivaroxaban triggered multifocal intratumoral hemorrhage of the cabozantinib-treated diffuse brain metastases: A case report and review of literature

- CTU findings of duplex kidney in kidney: A rare duplicated renal malformation

- Synchronous primary malignancy of colon cancer and mantle cell lymphoma: A case report

- Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography and pathologic characters of CD68 positive cell in primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: A case report and literature review

- Persistent SARS-CoV-2-positive over 4 months in a COVID-19 patient with CHB

- Pulmonary parenchymal involvement caused by Tropheryma whipplei

- Mediastinal mixed germ cell tumor: A case report and literature review

- Ovarian female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin – Case report

- Rare paratesticular aggressive angiomyxoma mimicking an epididymal tumor in an 82-year-old man: Case report

- Perimenopausal giant hydatidiform mole complicated with preeclampsia and hyperthyroidism: A case report and literature review

- Primary orbital ganglioneuroblastoma: A case report

- Primary aortic intimal sarcoma masquerading as intramural hematoma

- Sustained false-positive results for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M: A case report and literature review

- Peritoneal loose body presenting as a hepatic mass: A case report and review of the literature

- Chondroblastoma of mandibular condyle: Case report and literature review

- Trauma-induced complete pacemaker lead fracture 8 months prior to hospitalization: A case report

- Primary intradural extramedullary extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PIEES/PNET) of the thoracolumbar spine: A case report and literature review

- Computer-assisted preoperative planning of reduction of and osteosynthesis of scapular fracture: A case report

- High quality of 58-month life in lung cancer patient with brain metastases sequentially treated with gefitinib and osimertinib

- Rapid response of locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma to apatinib: A case report

- Retrieval of intrarenal coiled and ruptured guidewire by retrograde intrarenal surgery: A case report and literature review

- Usage of intermingled skin allografts and autografts in a senior patient with major burn injury

- Retraction

- Retraction on “Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappa B pathway”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part I

- An artificial immune system with bootstrap sampling for the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial cancers

- Breast cancer recurrence prediction with ensemble methods and cost-sensitive learning