Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

-

Luca Pezzullo

Abstract

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation during chemotherapy or after organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, and the risk of reactivation increases with patients’ age. Bendamustine, an alkylating agent currently used for treatment of indolent and aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas, can augment the risk of secondary infections including CMV reactivation. In this real-world study, we described an increased incidence of CMV reactivation in older adults (age >60 years old) with newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory indolent and aggressive diseases treated with bendamustine-containing regimens. In particular, patients who received bendamustine plus rituximab and dexamethasone were at higher risk of CMV reactivation, especially when administered as first-line therapy and after the third course of bendamustine. In addition, patients with CMV reactivation showed a significant depression of circulating CD4+ T cell count and anti-CMV IgG levels during active infection, suggesting an impairment of immune system functions which are not able to properly face viral reactivation. Therefore, a close and early monitoring of clinical and laboratory findings might improve clinical management and outcome of non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients by preventing the development of CMV disease in a subgroup of subjects treated with bendamustine more susceptible to viral reactivation.

1 Introduction

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are a heterogeneous group of hematologic diseases with various biological and clinical features classified in B, NK, or T cell lymphomas with different morphology, immunophenotype, genetic, and clinical features [1,2,3]. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) are the most common B-cell NHL, while mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is less frequent (3% of cases) [1,4]. Prognosis varies for each entity also based on clinical and molecular signatures. For example, in DLBCL, a mature B cell NHL frequently affecting older people, five-year overall survival (OS) ranges from 36 to 67% depending on nodal or extranodal involvement and combination of standard chemotherapy with rituximab [4,5,6]. In CLL, five-year OS can vary from 23.3 to 93.2% based on disease stage and serum markers [7,8,9]. Similarly, in follicular lymphoma (FL), the second most diagnosed lymphoma in Western Countries and frequently occurring in older patients, prognosis is influenced by clinical features, such as disease stage or number of involved nodal areas and two-year OS varies from 87% in high-risk to 98% in low-risk patients [10].

Bendamustine, an alkylating chemotherapeutic agent consisting of a purine analog-like benzimidazole ring, an alkylating agent group, and an alkane carboxylic chain, causes more durable intra- and inter-strand DNA cross-links than other alkylators and induces DNA damage and mitotic catastrophe [11,12,13]. Bendamustine is currently approved as first-line treatment of CLL Binet stage B or C, indolent NHL (iNHL) as monotherapy in patients relapsed or refractory to rituximab-based chemotherapy, and as first-line treatment in multiple myeloma patients not eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation [11]. This chemotherapeutic agent has also been used in newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory DLBCL and T-cell NHL [14,15,16,17]. Bendamustine-containing regimens are well-tolerated. The most frequent toxicities are thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, an increased risk of infections by opportunistic pathogens, such as Pneumocystis jirovecii, and higher risk of reactivation of chronic viral infections, including cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr, and Varicella-Zoster virus (VZV) [18,19,20]. CMV, a human herpesvirus, has an estimated seroprevalence worldwide of 45–100% in general population, and primary infection always occurs asymptomatically in immunocompetent subjects; however, immunocompromised patients experience a more aggressive disease with fever, hepatitis, severe pneumonia, encephalopathy and polyradiculopathy, myelosuppression, and graft rejection [21,22].

Bendamustine alone and in association with other immunosuppressive agents, such as steroids and rituximab, might increase the risk of CMV reactivation; however, literature lacks prospective longitudinal studies in large cohorts. In this real-world study, we investigated incidence of CMV reactivation in 167 consecutive patients with indolent and aggressive lymphoproliferative disorders treated with bendamustine-containing regimens, and candidate biomarkers of viral reactivation were also explored.

2 Subjects and methods

2.1 Patients and therapeutic regimens

Patients received diagnosis and chemotherapy as per international guidelines after informed consent obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki at the Hematology and Transplant Center, University Hospital “San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’Aragona” of Salerno, Italy, from June 2010 to April 2020. For assessment of CMV reactivation, a total of 167 patients with diagnosis of NHL were included in this retrospective study. Inclusion criteria were: age >18 years old; diagnosis of NHL; and treatment with bendamustine alone or in combination as first or above line of therapy. Median age was 70 years old (range, 41–88) and males were 59% (N = 99) (Table 1). NHL was diagnosed following the 2008 or 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms [1,23]; in particular, 95% (N = 158) B-cell NHL: DLBCL (N = 38; 23%); FL (N = 39; 23%); CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL; N = 32; 19%); mantle cell lymphoma (MCL; N = 17; 10%); marginal zone lymphoma (MZL; N = 18; 11%); lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (PLP; N = 4); plasmablastic lymphoma (PbL; N = 1); B-cell NHL not otherwise specified (NOS; N = 4); mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (N = 4); and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL; N = 1). Two subjects were diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, one with multiple myeloma, one with Waldenstrom disease, and 3% (N = 5) of patients with T-cell NHL.

Baseline patients’ characteristics

| Characteristics | N = 167 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 70 (41–88) |

| Sex, M/F | 99/68 |

| Diagnosis | |

| DLBCL | 38 |

| FL | 39 |

| CLL/SLL | 32 |

| MCL | 17 |

| MZL | 18 |

| Other B-cell NHL | 14 |

| T-cell NHL | 5 |

| Others | 4 |

| Stage | |

| I | 4 |

| II | 21 |

| III | 23 |

| IV | 82 |

| First-line therapy | |

| Bendamustine-based | 138 |

| Standard chemotherapy | 20 |

| Stem cell transplantation | 2 |

| No treatment | 7 |

| Second-line therapy | |

| Bendamustine-based | 18 |

| Standard chemotherapy | 3 |

| >2 lines of chemotherapy | 12 |

| Median cycles of bendamustine | 6 (1–10) |

| Median follow-up, months | 15.3 (0.6–99.5) |

| CMV serology | |

| IgG− | 4 |

| IgG+ | 80 |

Abbreviations: DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocyte leukemia; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CMV, cytomegalovirus; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Patients received bendamustine in combination with rituximab (RB regimen), rituximab and/or dexamethasone (DB, dexamethasone plus bendamustine; RDB, rituximab, dexamethasone, and bendamustine), and/or lenalidomide (LB, lenalidomide plus bendamustine; RLB, rituximab, lenalidomide, and bendamustine), or gemcitabine (GB). Bendamustine was given at doses of 70–90 mg/m2 for two consecutive days every 21 days for a maximum of four (RDB) or six (RB) cycles; while rituximab was administered at 375 mg/m2 every 21 days for a maximum of eight cycles, and dexamethasone was started at 20 mg/daily on days 1–4 and then tapered. Lenalidomide was administered at 25 mg/every other day. Patients with iNHL who achieved a complete remission received a maintenance therapy with rituximab at 375 mg/m2 every two months for two years. Therapeutic strategies non-containing bendamustine are summarized in Table 1. All patients received acyclovir and trimethoprim plus sulfamethoxazole as prophylaxis for VZV reactivation and for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, respectively.

2.2 Flow cytometry

Immunophenotyping was performed on fresh heparinized whole peripheral blood by flow cytometry (Figure 1). Neoplastic clones were identified using appropriate combinations of monoclonal antibodies as per manufacturer’s instructions (Beckman Coulter). CD4+ T cells were studied using the following antibodies: CD45; CD3; CD4; and CD8; and cell count assessed using beads as per manufacturer’s instructions (Beckman Coulter). Sample acquisition was carried out on a five-color FC500 cell analyzer cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) or on a ten-color three-laser Beckman Coulter Navios Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter). At least 1 million events per sample were recorded. Post-acquisition analysis was performed using CPX or Navios tetra software (Beckman Coulter).

![Figure 1

Flow cytometry gating strategy. After post-acquisition compensation using FlowJo, cell populations were first identified using linear parameters (forward scatter area [FSC-A] vs side scatter area [SSC-A], and double cells were excluded (FSC-A vs FSC-W)). On single cells, CD3+ cells were identified (CD3 vs SSC-A), and CD4 and CD8 expression was further studied. Flow cytometry analysis of a representative patient who experienced CMV reactivation is reported before starting treatment, after the first cycle of RDB and the third, and then after one year. Percent of CD3+ and CD4+ cells is shown for each timepoint.](/document/doi/10.1515/med-2021-0274/asset/graphic/j_med-2021-0274_fig_001.jpg)

Flow cytometry gating strategy. After post-acquisition compensation using FlowJo, cell populations were first identified using linear parameters (forward scatter area [FSC-A] vs side scatter area [SSC-A], and double cells were excluded (FSC-A vs FSC-W)). On single cells, CD3+ cells were identified (CD3 vs SSC-A), and CD4 and CD8 expression was further studied. Flow cytometry analysis of a representative patient who experienced CMV reactivation is reported before starting treatment, after the first cycle of RDB and the third, and then after one year. Percent of CD3+ and CD4+ cells is shown for each timepoint.

2.3 CMV-DNA quantification

Plasma CMV-DNA was quantified by real-time TaqMan CMV-DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) according to manufacturers’ instructions (Roche). During chemotherapy, CMV-DNA levels were measured every three weeks before starting each cycle, while CMV-DNA was monitored every week during CMV reactivation. After the end of treatment, CMV-DNA levels were measured every three months for two years. The instrument cut-off for positive results was CMV-DNA >137 copies/µL.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data were collected in spreadsheet and analyzed using Prism (v.8.3.0; GraphPad software, San Diego, CA). Categorical variables were compared by Fisher exact test, while continuous variable using Mann-Whitney nonparametric test. Two-group comparison was carried out by unpaired t-test. Differences in cumulative incidence of CMV reactivation between groups were assessed by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test and Hazard Ratio (HR) by log-rank. Multivariate analysis was performed by logistic regression model using SPSS Statistics software (IBM, Armonk, NY). A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Patients characteristics at baseline

A total of 167 NHL patients were included in the study for assessment of CMV reactivation during bendamustine-based chemotherapy. At diagnosis, disease stage was evaluable in 130 out of 167 subjects: 3% of cases (N = 4) showed a stage I disease; 16% (N = 21) stage II; 18% (N = 23) stage III; and 63% (N = 82) stage IV disease. In addition, 44 patients (26%) showed involvement of extra lymphatic organ or site, especially gastrointestinal tract (N = 14). A total of 160 patients received a first-line chemotherapy and 138 of them (86%) were treated with a bendamustine-based regimen: two subjects (1% of total treated patients) with bendamustine as single agent; one (1%) with DB; four (3%) with GB; 107 patients (67%) received RB and 22 (14%) RDB; while 2 subjects (1%) with LB or RLB. The remaining 22 subjects did not receive bendamustine containing regimens as first-line therapy, and 19 out of these 22 patients did not achieve a partial or complete remission requiring RB (N = 16) or other regimens as second-line therapy. Two subjects nonresponsive to RB as first-line therapy received GB or RB with bendamustine at 90 mg/m2. Eleven subjects had a third-line therapy (three bendamustine alone; six RB; and two RLB) and one a fourth-line treatment (R-CHOP to R-GemOx to R-CHOP to RB). Median complete cycles with bendamustine were six (range, 1–10). The presence of specific IgG against CMV at baseline was assessed in 90 subjects, and 89% of them (N = 80) were positive for CMV-IgG. Median follow-up was 15.3 months (range, 19 days to 99.5 months).

3.2 Clinical characteristics of patients with CMV reactivation

Forty-one patients (25%) experienced CMV reactivation with a median time to reactivation after starting bendamustine of 54 days (range, 11–309 days). Median age of this group of patients was 69 years old (range, 54–86), and 66% were males. Patients with CMV reactivation had a diagnosis of B-cell NHL in 95% of cases (N = 39) and T-cell NHL in 5% of subjects (N = 2; two Sézary syndrome). Among B-cell NHL, 6 subjects had DLBCL (15%), 9 (22%) FL, 8 (20%) CLL/SLL, 6 (15%) MCL, 5 (12%) MZL, and the remaining 5 cases (12%) were diagnosed as following: three cases with MALT and two with PLP. At diagnosis, disease stage was evaluable in 35 out of 41 subjects: 10% of cases (N = 4) showed a stage II disease; 7% (N = 3) stage III; and 68% (N = 28) stage IV disease. One CLL subject received bendamustine plus rituximab as second-line therapy after failure of fludarabine plus alemtuzumab; an FL patient was treated with rituximab plus higher dose of bendamustine after partial response to rituximab plus bendamustine at 70 mg/m2; the two subjects with Sézary syndrome received bendamustine alone as third-line therapy after failure of interferon-based regimens, while one MZL subject received RB after nonresponsiveness to chlorambucil first and R-FluCy later. The remaining 36 patients were treated with RD in 78% of cases (N = 28) or RDB in 22% of cases (N = 8) as first-line therapy with a median bendamustine cycle of 7 (range, 2–8). At baseline, median anti-CMV IgG levels were 108 UI/mL (range, 42–180 UI/mL), median lymphocyte count was 1,340 cells/µL (range, 530–14,895), and median CD4+ T cell count was 617 cells/µL (range, 180–1,278). Clinical manifestations of CMV reactivation were present in 15 patients (37%) and were: fever (20%; N = 8); diarrhea (5%; N = 2); anemia (5%; N = 2); chorioretinitis (2%; N = 1); and mucositis (2%; N = 1). The nadir lymphocyte count was 365 cells/µL (range, 0–1,590 cells/µL), while nadir anti-CMV IgG levels were 532 UI/mL (range, 129–1,320), nadir anti-CMV IgM levels were 42.5 UI/mL (range, 19–190), and nadir anti-CMV IgA were 82 UI/mL (range, 24–410). Median CMV-DNA levels were 2,120 copies/µL (range, 151–2,230,000). The maximum peak of 2,230,000 copies/µL was described after 69 days of treatment with RB with bendamustine at 90 mg/m2 in a patient with FL. Valganciclovir (VGCV) was administered at 900 or 1,800 mg/daily or twice per week based on clinical symptoms. One patient received first intravenous (IV) immunoglobulins (Ig) and then VGCV at 900 mg/daily. A total of four CMV-related deaths occurred in our cohort of patients. A 54 years old male patient with a diagnosis of MZL, stage IVb, died because of severe CMV disease. Reactivation occurred within 11 days after initiation of RB, and VGCV first at 900 mg/daily and then IVIg were administered; however, he died because of nonresponsiveness to antiviral therapy and severe CMV disease. OS was 31.7 months in patients with CMV reactivation, while subjects who did not experience CMV reactivation had an OS of 81.3 months; however, there were no statistically significant differences between groups (P = 0.2929).

3.3 Predictors of CMV reactivation

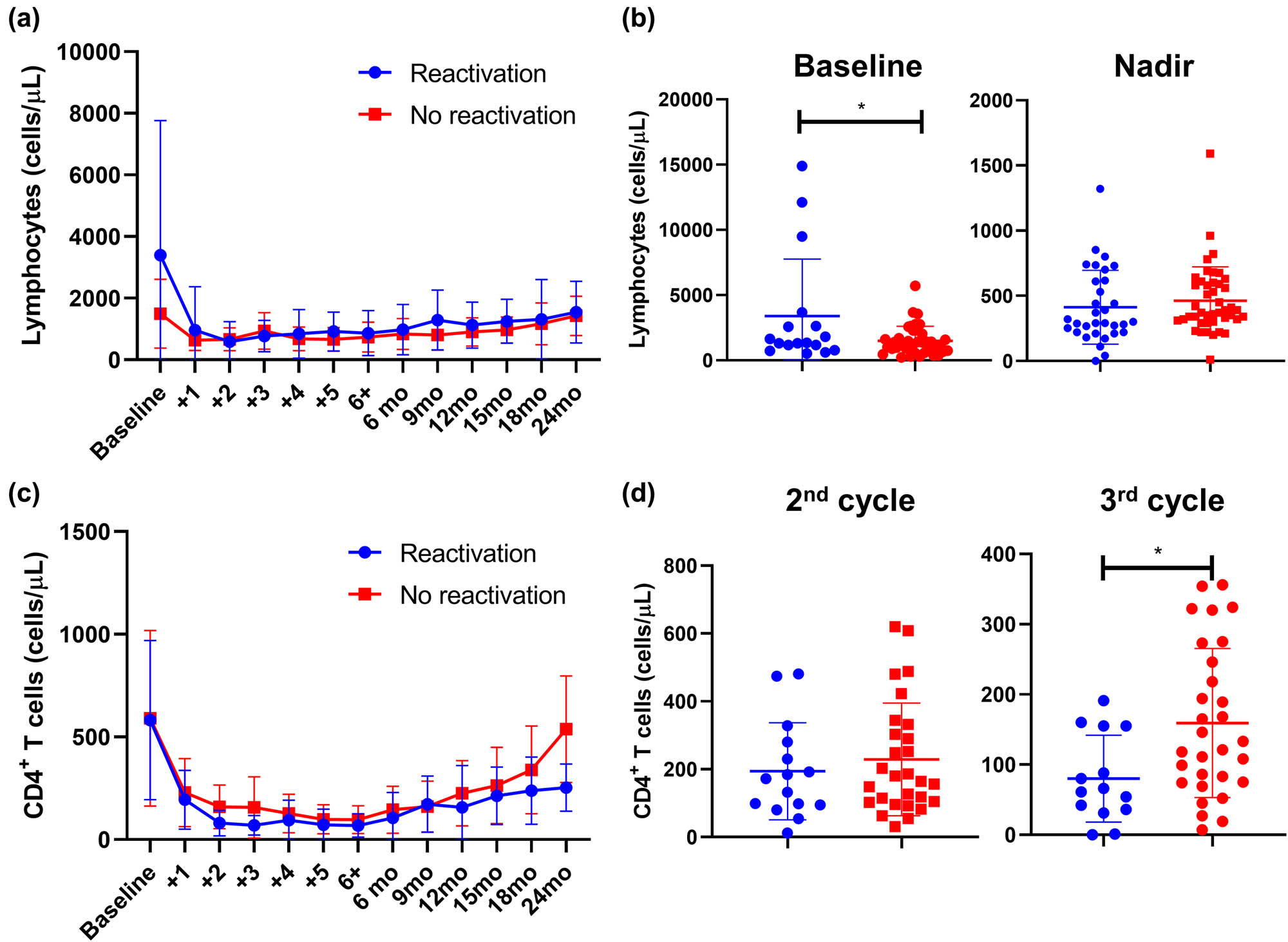

Whether to identify biomarkers of early CMV reactivation or risk factors, we compared clinical and laboratory findings between patients with CMV reactivation and subjects who did not experience viral reactivation. First, clinical and laboratory findings were compared between groups at baseline and during CMV reactivation (Table 2). No differences were described for age (P = 0.7069), number of bendamustine cycles (P = 0.6461), baseline anti-CMV IgG levels (mean ± SD, 111 ± 44.2 vs 113 ± 43.1, reactivation vs non-reactivation; P = 0.8610), and baseline CD4+ T cells (mean ± SD, 582 ± 387.8 vs 590 ± 427.5, reactivation vs non-reactivation; P = 0.9648). Significant variations were found in lymphocyte count at baseline (mean ± SD, 3,398 ± 4,366 vs 1,497 ± 1,117, reactivation vs no-reactivation; P = 0.0133), while frequencies were similar at the nadir of CMV reactivation (mean ± SD, 412 ± 282.9 vs 463 ± 259.7, reactivation vs non-reactivation; P = 0.4224) (Figure 2a and b). For CD4+ T cells, frequency similarly decreased after the first cycle of bendamustine in both CMV reactivated and non-reactivated groups; however, patients who did not experience CMV reactivation had higher CD4+ T cell count at the third bendamustine cycle compared to subjects who had CMV reactivation (mean ± SD, 80 ± 61.8 vs 159 ± 106.2, reactivation vs non-reactivation; P = 0.0133) (Figure 2c and d). In addition, anti-CMV IgG levels at the nadir of reactivation were lower in patients with CMV disease compared to patients who did not show viral reactivation (mean ± SD, 451 ± 208.7 vs 650 ± 254.6, reactivation vs non-reactivation; P = 0.0030), while anti-CMV IgA levels were similar between groups (P = 0.6259).

Patients’ characteristics at CMV reactivation

| Characteristics | CMV reactivation | No reactivation | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 41 | N = 126 | ||

| Age, years | 69 (54–86) | 71 (41–87) | 0.7069 |

| Sex, M/F | 27/14 | 72/54 | |

| Dead/Alive | 17/24 | 46/80 | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| DLBCL | 6 | 32 | |

| FL | 9 | 30 | |

| CLL/SLL | 8 | 24 | |

| MCL | 6 | 11 | |

| MZL | 5 | 13 | |

| Other B-cell NHL | 5 | 9 | |

| T-cell NHL | 2 | 3 | |

| Others | — | 4 | |

| Stage | |||

| I | 0 | 4 | |

| II | 4 | 17 | |

| III | 3 | 20 | |

| IV | 28 | 54 | |

| First-line therapy | |||

| Bendamustine-based | 37 | 101 | |

| Standard chemotherapy | 3 | 19 | |

| Second-line therapy | |||

| Bendamustine-based | 2 | 16 | |

| Standard chemotherapy | 1 | 2 | |

| >2 lines of chemotherapy | 3 | 9 | |

| Median cycles of bendamustine | 7 (2–8) | 6 (1–8) | 0.6461 |

| Median follow-up, months | 11.5 (0.7–51) | 18 (0.7–99.5) | 0.0097 |

| Time to reactivation, days | 54 (11–309) | — | |

| Baseline CMV IgG, UI/mL | 108 (42–180) | 127 (25–180) | 0.861 |

| Baseline CD4+ T cells/µL | 617 (180–1,278) | 591 (118–1,761) | 0.9648 |

| Baseline lymphocytes/µL | 1,340 (530–14,895) | 1,180 (200–5,700) | 0.0133 |

| Nadir lymphocytes/µL | 295 (0–1,320) | 410 (230–820) | 0.4224 |

| Nadir CMV-IgG, UI/mL | 412 (129–943) | 670 (416–937) | 0.003 |

| CMV-IgM, UI/mL | 38 (20–190) | — | |

| CMV-IgA, UI/mL | 83 (24–410) | 61 (49–158) | 0.6259 |

| CMV-DNA, copies/µL | 2,030 (151–2,230,000) | — | |

| Clinical manifestations | — | ||

| No symptoms | 26 | ||

| Fever | 8 | ||

| Diarrhea | 2 | ||

| Anemia | 2 | ||

| Chorioretinitis | 1 | ||

| Mucositis | 1 | ||

| Death | 4 | ||

| CMV treatment | |||

| Valgancyclovir | 18 | ||

| IVIg | 4 | ||

| Time to negativization, days | 45.5 (17–152) | ||

Abbreviations: DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocyte leukemia; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; CMV, cytomegalovirus; Ig, immunoglobulin; IVIg, intravenous immunoglobulins. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and highlighted in bold italic.

Lymphocyte and CD4+ T cell counts in CMV-reactivated and non-reactivated NHL patients. Patients were divided into two groups: subjects with CMV-reactivation (blue line or dots), and without CMV reactivation (red line or dots); and (a) lymphocyte counts are shown accordingly at baseline, before starting every cycle of bendamustine, and at regular monthly follow-up (month, mo). (b) Differences in lymphocyte counts at baseline and at the nadir of CMV reactivation were assessed by unpair t-test between patients who experienced CMV reactivation (blue dots) and those who did not have viral reactivation (blue dots). Similarly, CD4+ T cell counts were assessed from baseline through the follow-up (c), and frequencies of CD4+ cells in CMV-reactivated (blue dots) and non-reactivated (red dots) patients at the second and third cycle of bendamustine (d) are displayed. Data are shown as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD). *P < 0.05.

Next, cumulative incidence of CMV reactivation was calculated in our cohort of NHL patients showing an eight-year incidence of 46% (Figure 3a). Patients were then divided based on clinical and laboratory features and incidence proportion of CMV reactivation between groups was compared. No differences in CMV reactivation incidence were described when patients were divided based on sex (M vs F, P = 0.2607), diagnosis (P = 0.3963), disease stage (I–II vs III–IV, P = 0.1542), and number of bendamustine cycles (≤3 vs >3 cycles, P = 0.1753) (Figure 3b–e). Significant differences were described when patients were divided based on age with a cut-off of 60 years old (P = 0.0293; HR, 3.392; 95% confidential interval [CI], 1.602 to 7.180) and type of bendamustine-based regimen received as first-line therapy (Figure 3f and g). In particular, patients treated with RDB had a higher incidence of CMV reactivation compared to patients who did not receive bendamustine as first-line therapy (P = 0.0278; HR, 3.764; 95% CI, 1.134–12.49), while no differences were described between patients treated with RB or standard chemotherapy (P = 0.1658). Finally, multivariable analysis was performed in patients who received bendamustine-based regimens as first-line therapy and patients who were given standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment. In this latter group, none of analyzed variables, including age, sex, disease stage, cycles of bendamustine, nadir lymphocyte count, and anti-CMV IgG levels, was significantly associated to CMV reactivation, while in patients who received bendamustine as first-line treatment, potential risk factors were age ≥60 years old (P = 0.074), more than three bendamustine cycles (P = 0.027), and nadir anti-CMV IgG levels (P = 0.018).

![Figure 3

Cumulative incidence of CMV reactivation in NHL patients treated with bendamustine. (a) Cumulative incidence of CMV reactivation was first assessed on the entire cohort of patients diagnosed with NHL receiving bendamustine-containing regimens as first or above line of treatment. Then, influence of various clinical categories on the incidence of CMV reactivation was assessed by dividing patients based on: (b) type of lymphoma (FL, follicular lymphoma; DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; other B-NHL, other B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas; T-NHL, T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas); (c) sex (M, male; F, female); (d) disease stage (stage I–II, and stage III–IV); (e) number (No.) of bendamustine cycles (≤3 or >3); (f) age (<60 years old [yo] or ≥60 years old); and (g) therapeutic regimens administered as first-line therapy (not-containing bendamustine; RB, rituximab plus bendamustine; RDB, rituximab plus dexamethasone and bendamustine; other bendamustine-containing regimens including the drug alone).](/document/doi/10.1515/med-2021-0274/asset/graphic/j_med-2021-0274_fig_003.jpg)

Cumulative incidence of CMV reactivation in NHL patients treated with bendamustine. (a) Cumulative incidence of CMV reactivation was first assessed on the entire cohort of patients diagnosed with NHL receiving bendamustine-containing regimens as first or above line of treatment. Then, influence of various clinical categories on the incidence of CMV reactivation was assessed by dividing patients based on: (b) type of lymphoma (FL, follicular lymphoma; DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; other B-NHL, other B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas; T-NHL, T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas); (c) sex (M, male; F, female); (d) disease stage (stage I–II, and stage III–IV); (e) number (No.) of bendamustine cycles (≤3 or >3); (f) age (<60 years old [yo] or ≥60 years old); and (g) therapeutic regimens administered as first-line therapy (not-containing bendamustine; RB, rituximab plus bendamustine; RDB, rituximab plus dexamethasone and bendamustine; other bendamustine-containing regimens including the drug alone).

4 Discussion

CMV reactivation in immunocompromised subjects can cause a life-threatening disease and NHL patients are at higher risk because immune responses are already impaired, and chemotherapy can worse this condition because of myelo- and immuno-suppression [22,24]. In this real-world study, incidence of CMV reactivation was systematically and retrospectively investigated in a large cohort of NHL patients treated with bendamustine-containing regimens, and potential risk factors were outlined, such as age ≥60 years old, number of bendamustine cycles, and nadir anti-CMV IgG levels. In addition, variations in the immune status were also described at baseline and during treatment.

CMV reactivation in NHL patients has been anecdotically reported after bendamustine exposure often in older subjects with iNHL including FL, MCL, or MALT [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Most of those cases are refractory or relapsed iNHL, and they usually received bendamustine with or without rituximab as second or above line of therapy developing CMV disease after the third cycle of treatment. Two case series of 30 and 38 older relapse or refractory iNHL have reported an incidence of 20 and 6% of CMV reactivation after bendamustine exposure, respectively [26,27]. Some risk factors have also been identified, such as CD4/CD8 ratio and anti-CMV IgG levels; however, the small number of patients who experienced CMV reactivation in each cohort, the great heterogeneity in type of disease, stage, and previous treatments, and lack of data on younger adults and/or subjects diagnosed with aggressive NHL treated with bendamustine as first-line therapy could not allow the identification of univocal predictors of CMV reactivation. In this study, we presented results on a large cohort of patients with both iNHL and aggressive diseases mostly treated with bendamustine-containing regimens as first-line therapy. No differences in incidence of CMV reactivation were registered between patients with iNHL or aggressive lymphomas at any stage, suggesting that viral reactivation might be more likely related to immune impairments caused by chemotherapeutic agents than to those induced by the disease itself. Indeed, patients who received RDB as first-line therapy experienced CMV reactivation more frequently than those receiving only bendamustine or RB or than patients who received bendamustine-based regimens as second or above line of treatment [26]. These differences might be linked to a more profound immunosuppression caused by synergistic effects on both adaptive and innate immune responses of the combination of dexamethasone, rituximab, and bendamustine; while other bendamustine-containing regimens, such as RB, might not markedly impair immune system. Several studies have already described that combination of rituximab and dexamethasone has additive effects by reducing tumor cell growth, increasing apoptosis and rituximab-mediated complement-dependent cytotoxicity, and influencing or delaying immune reconstitution [33,34,35,36,37]. Bendamustine might enhance these synergistic effects and increase immunosuppression [33]. Indeed, incidence of CMV reactivation was also increased in patients on RB protocol and was similar between RB as first line of therapy and RB administered as second or above line of treatment, as already reported in several case reports of refractory or relapse iNHL receiving RB as second or above line therapy.

Older age (>65 years) has been indicated as an important risk factor of CMV reactivation in kidney (HR = 2.43) and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT; aged >50 years old; HR 1.40; 95% CI, 1.24–1.58) recipients [38,39,40]. In HSCT patients, CMV reactivation increases with T cell depletion and long-course steroid treatment [39]. In addition, in haploidentical HSCT, T cell repletion and post-transplant cyclophosphamide also augment the risk of CMV reactivation [41]. In NHL, CMV reactivation is a frequent cause of mortality, and prophylaxis might be warranted in patients at risk, such as patients with high antigenemia burden, recurrent CMV reactivation, and antiviral-associated toxicities [24]. In older iNHL (FL, MZL, and Waldenström macroglobulinemia) treated with bendamustine-containing regimens, the risk of CMV reactivation is increased (HR, 3.98; 95% CI, 1.40–11.26) compared to patients treated without bendamustine [18]; in particular, CMV reactivation is frequent in patients treated with bendamustine as third line or above therapy and exposed to corticosteroids [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Similarly, in our cohort, incidence of CMV reactivation was higher in patients aged >60 years; however, similar rates of reactivation were documented between indolent and aggressive diseases, or between bendamustine course as first-line therapy and second-line or above treatment (26 vs 11% respectively; P = 0.1361). Thus, we showed that CMV reactivation might complicate clinical courses and outcomes of both newly diagnosed and relapse/refractory older NHL patients with aggressive or indolent diseases.

CMV reactivation develops early in bendamustine administration usually after the third cycle of therapy, as documented in several case reports [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]; however, no significant differences in long-term cumulative incidence of reactivation were registered in our cohort between patients who received less than three courses of bendamustine and subjects who had more than three cycles of therapy, while in multivariate analysis the number of cycles of bendamustine increased the risk of CMV reactivation in treatment-naïve patients who received bendamustine as first-line therapy. This augmented susceptibility to viral reactivation might be caused by an impairment in T cell immunity, such as decreased circulating levels of CMV-specific CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes and CD4+ T cells [19,28,31,34,42,43]. In our study, patient with CMV reactivation had a significant depression of CD4+ T cell count between the second and third cycle of bendamustine compared to those subjects without CMV reactivation, in contrast with Isono et al. who documented a CD4+ cell decreased after the sixth course of bendamustine [26,43]. CD4+ T cells are important in maintaining CMV in its latent form, as a lack of CMV-specific CD4+ T cells is associated with a persistent viral shedding into urine and saliva even in healthy young subjects [44]. In addition, CMV-specific CD8+ T cells require the support of CMV-specific CD4+ T cells to prevent CMV reactivation after HSCT [45]. Therefore, CD4+ T cell depression during bendamustine treatment might affect the CMV-specific CD4+ T cell pool, thus increasing susceptibility to CMV reactivation in NHL patients. We also documented a significant decrease in circulating anti-CMV IgG at the nadir of reactivation which likely mirrors hyperactivation and/or exhaustion in both B and T cell immune responses [28].

Clinical manifestations and severity of CMV reactivation vary among patients treated with bendamustine, from no symptoms to severe CMV disease and death [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], as also described in our cohort. In symptomatic patients, various antiviral agents are employed, such as ganciclovir and VGCV at 900 or 1,800 mg/daily [46]. VGCV has also shown efficacy in prophylaxis of CMV reactivation in allogeneic HSCT at low dose (450 mg/daily for six months); however, drug-related toxicity, especially myelosuppression, might require drug discontinuation [47]. In our cohort, 18 patients who experienced CMV reactivation and high viremia with or without symptoms were treated with VGCV at low or high dose showing a median time of CMV viremia negativization of 45.5 days (range, 17–152 days) and four CMV disease-related deaths. No drug-related adverse events requiring antiviral agent discontinuation were registered.

In conclusion, CMV reactivation is a threat in hematologic patients who undergo chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies and/or conditioning regimens for HSCT [24,40]. Bendamustine, an alkylating agent, is used for treatment of iNHL; however, secondary infections are anecdotically reported, such as CMV reactivation in relapse/refractory iNHL patients [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. In our study, we described an increased incidence of CMV reactivation in older adults (age >60 years old) with newly diagnosed and relapse/refractory iNHL and aggressive disease treated with bendamustine-containing regimens, especially after the third course of bendamustine accompanied by a significant depression of circulating CD4+ T cell count and anti-CMV IgG levels. Therefore, a close and early monitoring of CD4+ T cell frequency, CMV-DNA, and virus-specific IgG levels might be required in older hematologic patients who received bendamustine, especially in combination with rituximab and dexamethasone, to prevent CMV reactivation and improve clinical management and outcomes of those subjects.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Bianca Cuffa and Francesca D’Alto (Hematology and Transplant Unit, University Hospital “San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’Aragona”), and the Flow Cytometry Facilities of the Hematology and Transplant Center and of the Transfusion Medicine Unit, University Hospital “San Giovanni di Dio e Ruggi d’Aragona” for technical assistance. This research was supported by the Intramural Program of the Department of Medicine, Surgery and Dentistry, University of Salerno, Italy.

-

Funding information: This research was supported by the Intramural Program of the Department of Medicine, Surgery and Dentistry, University of Salerno, Italy.

-

Author contributions: L. P., V. G., A. F., and C. S. designed the study. L. P., B. S., R. F., R. G., and C. M. enrolled patients and were involved in their clinical managements. E. M. performed diagnostic tests. V. G., A. B., and R. B. collected clinical data. V. G. analyzed the data. V. G., A. F., and C. S. wrote the manuscript. All the authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed with the final version.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

-

Data availability statements: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, C. S.

References

[1] Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–90.10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Giudice V, Mensitieri F, Izzo V, Filippelli A, Selleri C. Aptamers and antisense oligonucleotides for diagnosis and treatment of hematological diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3252.10.3390/ijms21093252Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Cozzolino I, Giudice V, Mignogna C, Selleri C, Caputo A, Zeppa P. Lymph node fine-needle cytology in the era of personalised medicine. Is there a role? Cytopathology. 2019;30(4):348–62.10.1111/cyt.12708Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Fisher SG, Fisher RI. The epidemiology of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Oncogene. 2004;23(38):6524–34.10.1038/sj.onc.1207843Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Gutiérrez-García G, Colomo L, Villamor N, Arenillas L, Martínez A, Cardesa T, et al. Clinico-biological characterization and outcome of primary nodal and extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(7):1225–32.10.3109/10428194.2010.483301Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Sun R, Medeiros LJ, Young KH. Diagnostic and predictive biomarkers for lymphoma diagnosis and treatment in the era of precision medicine. Mod Pathol. 2016;29(10):1118–42.10.1038/modpathol.2016.92Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Darwiche W, Gubler B, Marolleau JP, Ghamlouch H. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B-cell normal cellular counterpart: clues from a functional perspective. Front Immunol. 2018;9:683.10.3389/fimmu.2018.00683Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Hallek M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2017 update on diagnosis; risk stratification; and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:946–65.10.1002/ajh.24826Suche in Google Scholar

[9] International CLL-IPI Working Group. An international prognostic index for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL-IPI): a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:779–90.10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30029-8Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Freedman A. Follicular lymphoma: 2018 update on diagnosis and management. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(2):296–305.10.1002/ajh.24937Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[11] Hagemeister F, Manoukian G. Bendamustine in the treatment of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Onco Targets Ther. 2009;2:269–79.10.2147/OTT.S4873Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Hartmann M, Zimmer CH. Investigation of cross-link formation in DNA by alkylating cytostatic IMET 3106, 3393 and 3943. Biochem Biophys Acta. 1972;287:386–9.10.1016/0005-2787(72)90282-1Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Leoni LM, Bailey B, Reifert J, Bendall HH, Zeller RW, Corbeil J, et al. Bendamustine (Treanda) displays a distinct pattern of cytotoxicity and unique mechanistic features compared with other alkylating agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:309–17.10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1061Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[14] Ohmachi K, Niitsu N, Uchida T, Kim SJ, Ando K, Takahashi N, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bendamustine plus rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(17):2103–9.10.1200/JCO.2012.46.5203Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Park SI, Grover NS, Olajide O, Asch AS, Wall JG, Richards KL, et al. A phase II trial of bendamustine in combination with rituximab in older patients with previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2016;175(2):281–9.10.1111/bjh.14232Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Damaj G, Gressin R, Bouabdallah K, Cartron G, Choufi B, Gyan E, et al. Results from a prospective, open-label, phase II trial of bendamustine in refractory or relapsed T-cell lymphomas: the BENTLY trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:104–10.10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7285Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Gil L, Kazmierczak M, Kroll-Balcerzak R, Komarnicki M. Bendamustine-based therapy as first-line treatment for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Med Oncol. 2014;31(5):944.10.1007/s12032-014-0944-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Fung M, Jacobsen E, Freedman A, Prestes D, Farmakiotis D, Gu X, et al. Increased risk of infectious complications in older patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma exposed to bendamustine. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(2):247–55.10.1093/cid/ciy458Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl B, Wood P, Hawkins T, MacDonald D, et al. First-line treatment of patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma or mantle-cell lymphoma with bendamustine plus rituximab versus R-CHOP or R-CVP: results of the BRIGHT 5-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(12):984–91.10.1200/JCO.18.00605Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] Saito H, Maruyama D, Maeshima AM, Makita S, Kitahara H, Miyamoto K, et al. Prolonged lymphocytopenia after bendamustine therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory indolent B-cell and mantle cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5(10):e362.10.1038/bcj.2015.86Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[21] Cannon MJ, Schmid DS, Hyde TB. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev Med Virol. 2010;20(4):202–13.10.1002/rmv.655Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[22] Emery VC. Investigation of CMV disease in immunocompromised patients. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54(2):84–8.10.1136/jcp.54.2.84Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117(19):5019–32.10.1182/blood-2011-01-293050Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[24] Torres HA, Kontoyiannis DP, Aguilera EA, Younes A, Luna MA, Tarrand JJ, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in patients with lymphoma: an important cause of morbidity and mortality. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2006;6(5):393–8.10.3816/CLM.2006.n.016Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[25] Singhania SVK, Parikh P, Goyle S. CMV pneumonitis following bendamustine containing chemotherapy. J Assoc Physicians India. 2017;65(9):92–3.Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Isono N, Imai Y, Watanabe A, Moriya K, Tamura H, Inokuchi K, et al. Cytomegalovirus reactivation in low-grade B-cell lymphoma patients treated with bendamustine. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(9):2204–7.10.3109/10428194.2015.1126589Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Hasegawa T, Aisa Y, Shimazaki K, Nakazato T. Cytomegalovirus reactivation with bendamustine in patients with low-grade B-cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2015;94(3):515–7.10.1007/s00277-014-2182-1Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Cona A, Tesoro D, Chiamenti M, Merlini E, Ferrari D, Marti A, et al. Disseminated cytomegalovirus disease after bendamustine: a case report and analysis of circulating B- and T-cell subsets. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):881.10.1186/s12879-019-4545-7Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Lim SH, Pathapati S, Langevin J, Hoot A. Severe CMV reactivation and gastritis during treatment of follicular lymphoma with bendamustine. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(4):643–4.10.1007/s00277-011-1307-zSuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[30] Modvig L, Boyle C, Randall K, Borg A. Severe cytomegalovirus reactivation in patient with low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma after standard chemotherapy. Case Rep Hematol. 2017;2017:5762525.10.1155/2017/5762525Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Hosoda T, Yokoyama A, Yoneda M, Yamamoto R, Ohashi K, Kagoo T, et al. Bendamustine can severely impair T-cell immunity against cytomegalovirus. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54(6):1327–8.10.3109/10428194.2012.739285Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Yamasaki S, Kohno K, Kadowaki M, Takase K, Iwasaki H. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in relapsed or refractory low-grade B cell lymphoma patients treated with bendamustine. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(7):1215–7.10.1007/s00277-017-3005-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed

[33] Ito K, Okamoto M, Ando M, Kakumae Y, Okamoto A, Inaguma Y, et al. Influence of rituximab plus bendamustine chemotherapy on the immune system in patients with refractory or relapsed follicular lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(4):1123–5.10.3109/10428194.2014.921298Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] Yutaka T, Ito S, Ohigashi H, Naohiro M, Shimono J, Souichi S, et al. Sustained CD4 and CD8 lymphopenia after rituximab maintenance therapy following bendamustine and rituximab combination therapy for lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(11):3216–8.10.3109/10428194.2015.1026818Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] García Muñoz R, Izquierdo-Gil A, Muñoz A, Roldan-Galiacho V, Rabasa P, Panizo C. Lymphocyte recovery is impaired in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine plus rituximab. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(11):1879–87.10.1007/s00277-014-2135-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[36] Worch J, Makarova O, Burkhardt B. Immunreconstitution and infectious complications after rituximab treatment in children and adolescents: what do we know and what can we learn from adults? Cancers (Basel). 2015;7(1):305–28.10.3390/cancers7010305Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Rose AL, Smith BE, Maloney DG. Glucocorticoids and rituximab in vitro: synergistic direct antiproliferative and apoptotic effects. Blood. 2002;100(5):1765–73.10.1182/blood.V100.5.1765.h81702001765_1765_1773Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Hemmersbach-Miller M, Alexander BD, Pieper CF, Schmader KE. Age matters: older age as a risk factor for CMV reactivation in the CMV serostatus-positive kidney transplant recipient. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39(3):455–63.10.1007/s10096-019-03744-3Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Stern L, Withers B, Avdic S, Gottlieb D, Abendroth A, Blyth E, et al. Human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1186.10.3389/fmicb.2019.01186Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Takenaka K, Nishida T, Asano-Mori Y, Oshima K, Ohashi K, Mori T, et al. Cytomegalovirus reactivation after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is associated with a reduced risk of relapse in patients with acute myeloid leukemia who survived to day 100 after transplantation: the Japan society for hematopoietic cell transplantation transplantation-related complication working group. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(11):2008–16.10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.07.019Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[41] Slade M, Goldsmith S, Romee R, DiPersio JF, Dubberke ER, Westervelt P, et al. Epidemiology of infections following haploidentical peripheral blood hematopoietic cell transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19(1):e12629.10.1111/tid.12629Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Sylwester AW, Mitchell BL, Edgar JB, Taormina C, Pelte C, Ruchti F, et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J Exp Med. 2005;202(5):673–85.10.1084/jem.20050882Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Isono N, Imai Y, Asano C, Masuda M, Hoshino S, Moriya K, et al. Prospective analysis of cytomegalovirus reactivation and the immune state of low-grade B-cell lymphoma patients treated with bendamustine. Blood. 2014;124(21):4411.10.1182/blood.V124.21.4411.4411Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Lim EY, Jackson SE, Wills MR. The CD4+ T cell response to human cytomegalovirus in healthy and immunocompromised people. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:202.10.3389/fcimb.2020.00202Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] van der Heiden PLJ, van Egmond HM, Veld SAJ, van de Meent M, Eefting M, de Wreede LC, et al. CMV seronegative donors: Effect on clinical severity of CMV infection and reconstitution of CMV-specific immunity. Transpl Immunol. 2018;49:54–8.10.1016/j.trim.2018.04.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] O’Brien S, Ravandi-Kashani F, Wierda WG, Giles F, Thomas D, Huang X, et al. A randomized trial of valacyclovir versus valganciclovir to prevent CMV reactivation in patients with CLL receiving alemtuzumab. Blood. 2005;106(11):2960.10.1182/blood.V106.11.2960.2960Suche in Google Scholar

[47] Serio B, Rosamilio R, Giudice V, Pepe S, Zeppa P, Esposito S, et al. Low-dose valgancyclovir as cytomegalovirus reactivation prophylaxis in allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Infez Med. 2012;20(2):26–34.Suche in Google Scholar

© 2021 Luca Pezzullo et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells

- Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 in healthy paediatric population

- Algorithm of rational approach to reconstruction in Fournier’s disease

- A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury

- Src-1 and SP2 promote the proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Dexmedetomidine may decrease the bupivacaine toxicity to heart

- Hypoxia stimulates the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma via up-regulating the NUSAP1 expression

- Long noncoding RNA XIST knockdown relieves the injury of microglia cells after spinal cord injury by sponging miR-219-5p

- External fixation via the anterior inferior iliac spine for proximal femoral fractures in young patients

- miR-128-3p reduced acute lung injury induced by sepsis via targeting PEL12

- HAGLR promotes neuron differentiation through the miR-130a-3p-MeCP2 axis

- Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 is elevated in serum of patients with heart failure and correlates with the disease severity and patient’s prognosis

- Cell population data in identifying active tuberculosis and community-acquired pneumonia

- Prognostic value of microRNA-4521 in non-small cell lung cancer and its regulatory effect on tumor progression

- Mean platelet volume and red blood cell distribution width is associated with prognosis in premature neonates with sepsis

- 3D-printed porous scaffold promotes osteogenic differentiation of hADMSCs

- Association of gene polymorphisms with women urinary incontinence

- Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels of urologic patients

- miR-496 inhibits proliferation via LYN and AKT pathway in gastric cancer

- miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development

- Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- Fluorescent light energy modulates healing in skin grafted mouse model

- Silencing CDK6-AS1 inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory damage in HK-2 cells

- Predictive effect of DCE-MRI and DWI in brain metastases from NSCLC

- Severe postoperative hyperbilirubinemia in congenital heart disease

- Baicalin improves podocyte injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

- Clinical factors predicting ureteral stent failure in patients with external ureteral compression

- Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway

- Triple-Endobutton and clavicular hook: A propensity score matching analysis

- Long noncoding RNA MIAT inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy and the activation of NF-κB pathway in high glucose-treated renal tubular epithelial cells by the miR-182-5p/GPRC5A axis

- Serum exosomal miR-122-5p, GAS, and PGR in the non-invasive diagnosis of CAG

- miR-513b-5p inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells by targeting TRIB1

- Fer exacerbates renal fibrosis and can be targeted by miR-29c-3p

- The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-92a in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prognostic value of α2δ1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study

- No significant benefit of moderate-dose vitamin C on severe COVID-19 cases

- circ_0000467 promotes the proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating KLF12 expression by sponging miR-4766-5p

- Downregulation of RAB7 and Caveolin-1 increases MMP-2 activity in renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxic conditions

- Educational program for orthopedic surgeons’ influences for osteoporosis

- Expression and function analysis of CRABP2 and FABP5, and their ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

- lncRNA-ZFAS1 promotes the progression of endometrial carcinoma by targeting miR-34b to regulate VEGFA expression

- Anticoagulation is the answer in treating noncritical COVID-19 patients

- Effect of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis on PFS after haplo-PBSCT

- Comparison of Dako HercepTest and Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2 (4B5) tests and their correlation with silver in situ hybridization in lung adenocarcinoma

- VSTM1 regulates monocyte/macrophage function via the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Comparison of vaginal birth outcomes in midwifery-led versus physician-led setting: A propensity score-matched analysis

- Treatment of osteoporosis with teriparatide: The Slovenian experience

- New targets of morphine postconditioning protection of the myocardium in ischemia/reperfusion injury: Involvement of HSP90/Akt and C5a/NF-κB

- Superenhancer–transcription factor regulatory network in malignant tumors

- β-Cell function is associated with osteosarcopenia in middle-aged and older nonobese patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study

- Clinical features of atypical tuberculosis mimicking bacterial pneumonia

- Proteoglycan-depleted regions of annular injury promote nerve ingrowth in a rabbit disc degeneration model

- Effect of electromagnetic field on abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- miR-150-5p affects AS plaque with ASMC proliferation and migration by STAT1

- MALAT1 promotes malignant pleural mesothelioma by sponging miR-141-3p

- Effects of remifentanil and propofol on distant organ lung injury in an ischemia–reperfusion model

- miR-654-5p promotes gastric cancer progression via the GPRIN1/NF-κB pathway

- Identification of LIG1 and LIG3 as prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer

- MitoQ inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis by enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy

- Dissecting role of founder mutation p.V727M in GNE in Indian HIBM cohort

- circATP2A2 promotes osteosarcoma progression by upregulating MYH9

- Prognostic role of oxytocin receptor in colon adenocarcinoma

- Review Articles

- The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Efficacy and safety of therapeutic plasma exchange in stiff person syndrome

- Role of cesarean section in the development of neonatal gut microbiota: A systematic review

- Small cell lung cancer transformation during antitumor therapies: A systematic review

- Research progress of gut microbiota and frailty syndrome

- Recommendations for outpatient activity in COVID-19 pandemic

- Rapid Communication

- Disparity in clinical characteristics between 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia and leptospirosis

- Use of microspheres in embolization for unruptured renal angiomyolipomas

- COVID-19 cases with delayed absorption of lung lesion

- A triple combination of treatments on moderate COVID-19

- Social networks and eating disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Letter

- COVID-19, WHO guidelines, pedagogy, and respite

- Inflammatory factors in alveolar lavage fluid from severe COVID-19 pneumonia: PCT and IL-6 in epithelial lining fluid

- COVID-19: Lessons from Norway tragedy must be considered in vaccine rollout planning in least developed/developing countries

- What is the role of plasma cell in the lamina propria of terminal ileum in Good’s syndrome patient?

- Case Report

- Rivaroxaban triggered multifocal intratumoral hemorrhage of the cabozantinib-treated diffuse brain metastases: A case report and review of literature

- CTU findings of duplex kidney in kidney: A rare duplicated renal malformation

- Synchronous primary malignancy of colon cancer and mantle cell lymphoma: A case report

- Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography and pathologic characters of CD68 positive cell in primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: A case report and literature review

- Persistent SARS-CoV-2-positive over 4 months in a COVID-19 patient with CHB

- Pulmonary parenchymal involvement caused by Tropheryma whipplei

- Mediastinal mixed germ cell tumor: A case report and literature review

- Ovarian female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin – Case report

- Rare paratesticular aggressive angiomyxoma mimicking an epididymal tumor in an 82-year-old man: Case report

- Perimenopausal giant hydatidiform mole complicated with preeclampsia and hyperthyroidism: A case report and literature review

- Primary orbital ganglioneuroblastoma: A case report

- Primary aortic intimal sarcoma masquerading as intramural hematoma

- Sustained false-positive results for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M: A case report and literature review

- Peritoneal loose body presenting as a hepatic mass: A case report and review of the literature

- Chondroblastoma of mandibular condyle: Case report and literature review

- Trauma-induced complete pacemaker lead fracture 8 months prior to hospitalization: A case report

- Primary intradural extramedullary extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PIEES/PNET) of the thoracolumbar spine: A case report and literature review

- Computer-assisted preoperative planning of reduction of and osteosynthesis of scapular fracture: A case report

- High quality of 58-month life in lung cancer patient with brain metastases sequentially treated with gefitinib and osimertinib

- Rapid response of locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma to apatinib: A case report

- Retrieval of intrarenal coiled and ruptured guidewire by retrograde intrarenal surgery: A case report and literature review

- Usage of intermingled skin allografts and autografts in a senior patient with major burn injury

- Retraction

- Retraction on “Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappa B pathway”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part I

- An artificial immune system with bootstrap sampling for the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial cancers

- Breast cancer recurrence prediction with ensemble methods and cost-sensitive learning

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study