Abstract

Recent studies indicate that host immune responses are dysregulated with either myeloid cell compartment or lymphocyte composition being disturbed in COVID-19. This study aimed to assess the impact of SARS-CoV-2 viral infection on the composition of circulating immune cells in severe COVID-19 patients. In this retrospective single-center cohort, 71 out of 87 COVID-19 patients admitted to the intense care unit for oxygen treatment were included in this study. Demographics, clinical features, comorbidities, and laboratory findings were collected on admission. Out of the 71 patients, 5 died from COVID-19. Compared with survived patients, deceased patients showed higher blood cell counts of neutrophils and monocytes but lower cell counts of lymphocytes. Intriguingly, the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), and basophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (BLR) were markedly higher in deceased patients compared to survived patients. Furthermore, the lymphocyte counts were negatively correlated with D-dimer levels, while the ratios between myeloid cells and lymphocyte (NLR, MLR, and BLR) were positively correlated with D-dimer levels. Our findings revealed that the ratios between myeloid cells and lymphocytes were highly correlated with coagulation status and patient mortality in severe COVID-19.

1 Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, mediated by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 [1,2]. As with other virulent coronavirus infections such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), SARS-CoV-2 poses a major health threat to human worldwide [3,4]. With the rapid spread worldwide causing high morbidity and mortality, it has been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization. There have been 24,257,989 confirmed cases and 827,246 deaths reported as of 28 August 2020 [5].

Respiratory compromise characterized by lower respiratory tract symptoms, such as fever, dry cough, and dyspnea, has been reported in patients with COVID-19 [6]. In patients with severe COVID-19, the disease progresses to acute respiratory distress syndrome and life-threatening events including coagulopathy, septic shock, and death [3]. To reduce the morbidity and mortality rates, it is crucial to identify key risk factors associated with poorer prognosis. Basic laboratory tests have been proven crucial in identification of high-risk COVID-19 patients [7]. This allows early intensive care and support to be provided to patients at high risk of mortality.

The immune systems, including the innate and adaptive immune systems, are commonly disturbed in virus infection [8,9,10]. White blood cells, which are categorized into myeloid cells (neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils) and lymphocytes (T cells, B cells, and natural killer [NK] cells) based on their cell lineage, constitute the first line of defense against invading pathogens including viruses [11]. In COVID-19, several recent studies indicate that host immune responses are dysregulated with either myeloid cell compartment [12,13,14] or lymphocyte composition [15,16,17] being disturbed. Furthermore, the effectiveness and concerns over immunosuppressive therapies in COVID-19 patients have been discussed [18,19]. However, studies on differential involvement of the myeloid cells and lymphocytes and their correlation with the coagulation status and disease severity in COVID-19 patients are scarce to date.

In this study, we analyzed blood cells, coagulation parameters, and inflammatory markers from routine clinical laboratory tests and discovered the differential impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes. Furthermore, we found that the ratios between myeloid cells and lymphocytes were highly correlated with blood coagulation status and disease severity in COVID-19.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Patients and study design

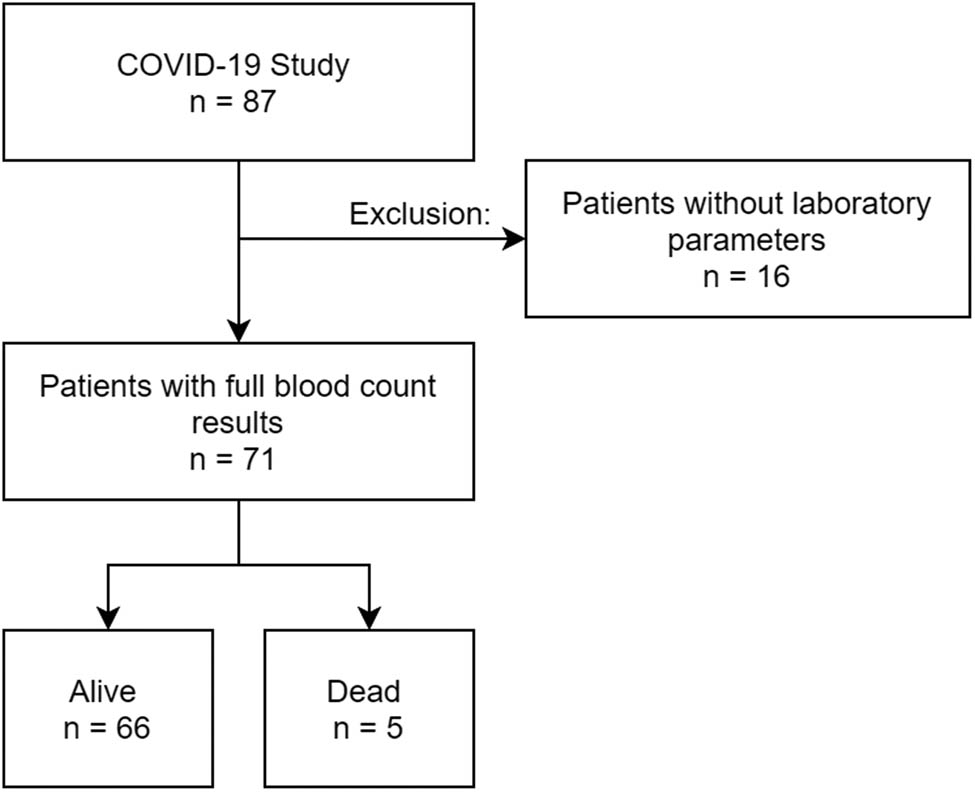

This was a retrospective single-center study with a total of 87 patients tested positive with COVID-19 between 19 January and 23 February 2020 in Wuhan Iron & Steel (Group) Company Second Staff Hospital. Subsequently, only 71 patients with comprehensive medical records were included in this study (Figure 1). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tianjin Chest Hospital (IRB-SOP-016(F)-001-02). The need for informed consent was waived given the observational and retrospective nature of the study.

Study design.

All patients were confirmed of COVID-19 either by SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test (63.4%) or by clinical symptoms and computerized tomography (CT) scan imaging (36.6%), according to the Diagnosis and Treatment Protocol for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia (Trial Version 4.0) released by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China [20]. Patient data including demographics, comorbidities, symptoms, and laboratory findings were collected during the hospital admission.

2.2 Laboratory testing

Patient throat swab specimens were collected for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 via the real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay. Peripheral blood was collected and analyzed in the clinical laboratory of Wuhan Iron & Steel (Group) Company Second Staff Hospital. The laboratory test results including full blood cell counts, coagulation parameters (prothrombin time [PT], international normalized ratio [INR], activated partial thromboplastin time [APTT], thrombin time [TT], D-dimer, and fibrinogen), and other blood markers (C-reactive protein [CRP] and creatinine kinase [CK]) were assessed for both survived and deceased COVID-19 patients. A full blood count was performed using the XN-10 automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex® Corporation), which generated the white blood cell differential fluorescence (WDF) scattergram [21].

2.3 Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Graphs for figures were prepared with GraphPad Prism 8.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Missing data were not imputed. Continuous data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median ± interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables were presented as percentage. The differences were compared by Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, χ 2 test, or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the nature of data. The relationship among biomarkers was assessed using Spearman’s correlation analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

From 19 January to 23 February 2020, a total of 71 patients admitted to Wuhan Iron & Steel (Group) Company Second Staff Hospital with confirmed COVID-19 and comprehensive medical records were included in this study (Figure 1). Five of these 71 patients died from COVID-19 and 66 patients fully recovered and were discharged. As shown in Table 1, the median age of deceased patients was significantly older than those who recovered (74.0 years, IQR: 65.0–83.0 vs 61.0 years, IQR: 50.0–71.0; p = 0.025), and there were more males in the deceased patients (100 vs 40.9%; p = 0.010). Of all COVID-19 patients, nearly half of them (n = 34, 47.9%) had at least one chronic medical condition, with diabetes being the most common comorbidity followed by hypertension, coronary heart disease, malignancy, cerebrovascular disease, and respiratory disease. Hypertension was more frequently seen among the deceased patients than those who recovered (60.0 vs 13.6%; p = 0.008).

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| Alive | Dead | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 66 | n = 5 | ||

| Demographic | |||

| Age (years) | 61.0 (50.0–71.0) | 74.0 (65.0–83.0) | 0.025 |

| Male (%) | 27 (40.9) | 5 (100.0) | 0.010 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Nuclear test (%) | 42 (63.6) | 3 (60.0) | 0.871 |

| Clinical test (%) | 24 (36.4) | 2 (40.0) | 0.871 |

| Hospital stay duration (days) | 19.5 (16.0–22.0) | 6 (3.5–15.0) | 0.008 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Fever (%) | 40 (60.6) | 5 (100.0) | 0.078 |

| Cough (%) | 35 (53.0) | 4 (80.0) | 0.243 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 12 (18.2) | 1 (20.0) | 0.919 |

| Hypertension (%) | 9 (13.6) | 3 (60.0) | 0.008 |

| Coronary heart disease (%) | 8 (12.1) | 1 (20.0) | 0.610 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (%) | 2 (3.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0.069 |

| Respiratory disease (%) | 2 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.693 |

| Malignancy (%) | 4 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.571 |

Continuous data are presented as mean ± SD or median ± IQR, and statistical analysis of continuous data was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables are presented as %, with differences between the groups tested with χ 2. Bold values indicate significant difference with a p-value of less than 0.05.

3.2 Laboratory parameters of COVID-19 patients

Differences in the initial laboratory parameters, including blood cell counts and biochemical markers, between the deceased patients and those who recovered from COVID-19 are presented in Table 2.

Laboratory parameters of COVID-19 patients

| Alive | Dead | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 66 | n = 5 | ||

| Full blood count indices | |||

| RBC count (×1012/L) | 4.06 (3.80–4.29) | 3.46 (3.15–3.90) | 0.010 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 125.00 (118.00–133.00) | 116.00 (106.00–135.00) | 0.237 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 36.90 (34.80–39.45) | 35.50 (31.35–38.90) | 0.261 |

| MCV (fL) | 91.70 (89.10–93.90) | 92.10 (89.95–101.55) | 0.370 |

| MCH (pg) | 30.90 (30.00–32.10) | 32.10 (29.95–34.75) | 0.251 |

| MCHC (g/L) | 337.50 (330.50–344.00) | 330.00 (319.50–341.00) | 0.146 |

| RDW-CV (%) | 12.00 (11.60–12.60) | 12.50 (11.75–12.95) | 0.389 |

| RDW (fL) | 46.00 (44.20–48.30) | 49.30 (44.05–52.45) | 0.153 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 228.00 (184.00–264.00) | 152.00 (88.00–178.00) | 0.004 |

| PDW (fL) | 16.10 (15.80–16.40) | 15.90 (15.35–17.00) | 0.282 |

| MPV (fL) | 8.90 (8.30–9.40) | 9.00 (8.75–9.55) | 0.567 |

| PCT (%) | 0.19 (0.17–0.22) | 0.21 (0.09–0.23) | 0.836 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 5.85 (4.55–6.61) | 8.43 (5.38–10.49) | 0.056 |

| Neutrophil count (×109/L) | 3.53 (2.54–4.27) | 6.83 (4.16–8.32) | 0.007 |

| Lymphocyte count (×109/L) | 1.57 (1.20–1.88) | 0.91 (0.61–1.31) | 0.014 |

| Monocyte count (×109/L) | 0.41 (0.33–0.49) | 0.61 (0.46–0.80) | 0.008 |

| Basophil count (×109/L) | 0.03 (0.02–0.03) | 0.06 (0.02–0.18) | 0.110 |

| Eosinophil count (×109/L) | 0.15 (0.11–0.22) | 0.11 (0.08–0.17) | 0.256 |

| Coagulation panel | |||

| PT (s) | 11.00 (10.60–11.30) | 11.40 (10.75–14.70) | 0.173 |

| INR | 0.85 (0.80–0.85) | 0.89 (0.81–1.17) | 0.268 |

| APTT (s) | 32.60 (29.30–38.45) | 29.40 (27.30–32.80) | 0.190 |

| TT (s) | 14.20 (13.70–14.65) | 14.80 (13.70–15.40) | 0.290 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.49 (2.07–2.97) | 2.43 (1.97–2.93) | 0.679 |

| D-dimer (µg/mL) | 0.57 (0.30–2.10) | 2.01 (1.17–3.00) | 0.159 |

| Others | |||

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 29.58 (5.00–74.50) | 75.25 (48.55–78.63) | 0.203 |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 37.00 (29.00–51.00) | 105.00 (69.00–165.00) | 0.019 |

Data are presented as median ± IQR and statistical analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Abbreviations: RBC, red blood cell; MCV, mean cell volume; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; RDW-CV, red cell distribution width – coefficient of variation; RDW, red cell distribution width; PDW, platelet distribution width; MPV, mean platelet volume; PCT, plateletcrit; WBC, white blood cell; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; TT, thrombin time. Bold values indicate significant difference with a p-value of less than 0.05.

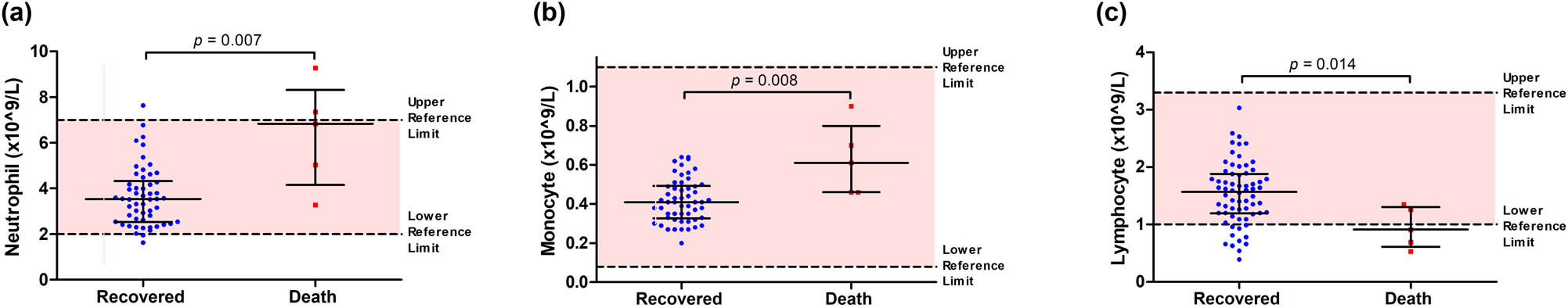

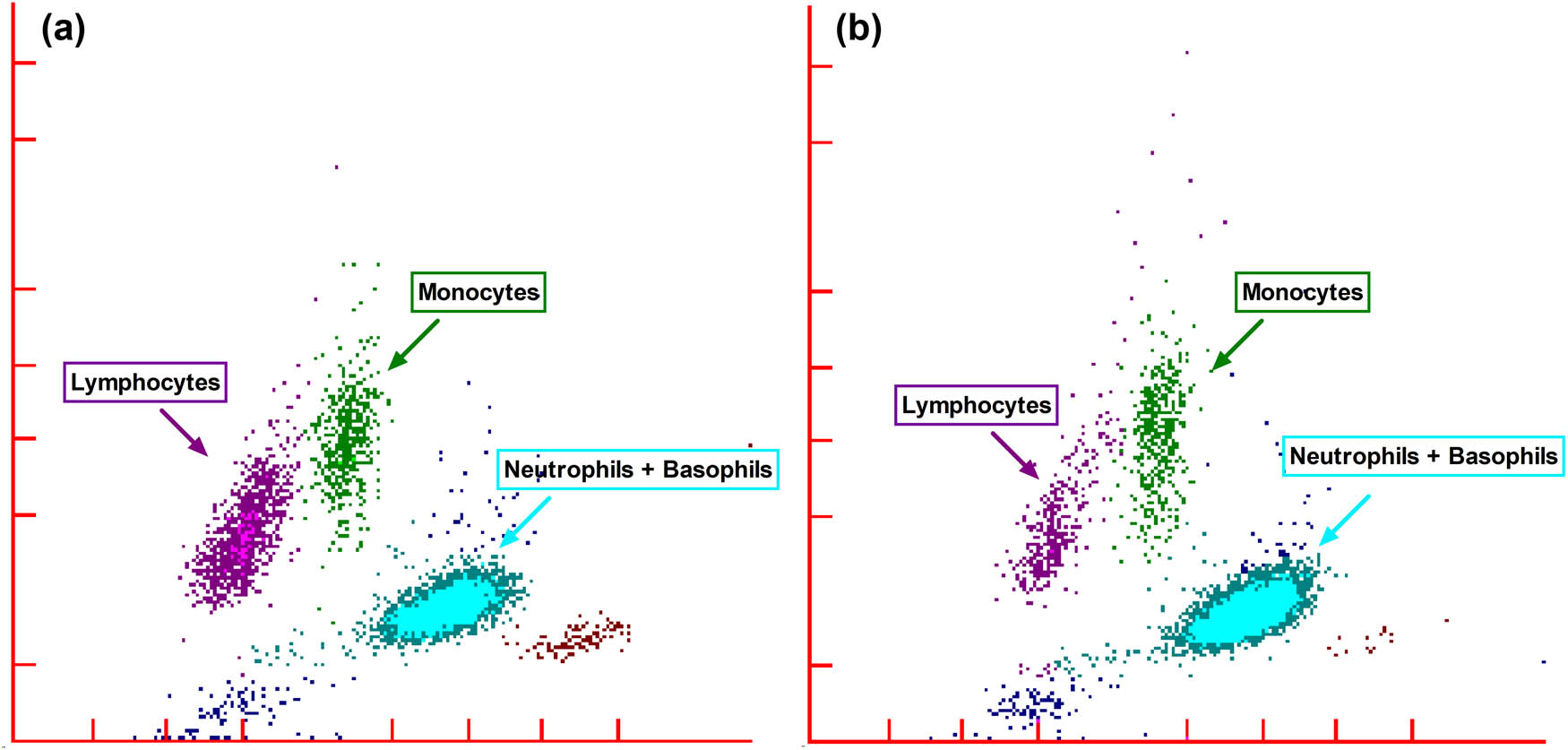

A full blood count and the white blood cell WDF scattergram were generated using the XN-10 automated hematology analyzer (Table 2 and Figure S1). Compared with the survivors, the deceased patients had lower red blood cell counts (3.46 × 1012/L vs 4.06 × 1012/L; p = 0.010) and platelet counts (152.00 × 109/L vs 228.00 × 109/L; p = 0.004). Interestingly, deceased patients presented with lower lymphocyte counts (0.91 × 109/L vs 1.57 × 109/L; p = 0.014) but higher neutrophil (6.83 × 109/L vs 3.53 × 109/L; p = 0.007) and monocyte counts (0.61 × 109/L vs 0.41 × 109/L; p = 0.008) (Table 2, Figure 2 and Figure S1). No difference in basophil and eosinophil counts was observed between the two patient groups.

Myeloid cells (a, neutrophils; b, monocytes) and lymphocytes (c) in deceased patients and those recovered from COVID-19. Data are presented as median ± IQR, and statistical analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney U test. The region highlighted in pink is the normal ranges of the respective cell counts.

All the patients presented with pro-thrombotic states, including relatively lower PT and INR, and higher D-dimer levels (Table 2). Of all COVID-19 patients with available data of coagulation tests, 22 out of 31 (70.97%) patients presented with D-dimer levels higher than the normal range. However, no significant difference was observed between survived and deceased patients in any of the coagulation parameters measured, including D-dimer levels (2.01 µg/mL, IQR: 1.17–3.00 for deceased patients vs 0.57 µg/mL, IQR: 0.30–2.10 for survived patients; p = 0.159), likely due to a small number of deceased patients in the current study.

The levels of an inflammatory biomarker, CRP, were elevated in most COVID-19 patients whose CRP data were available, with 18 out of 25 (72.00%) patients presented with CRP levels higher than the normal range. Although higher median CRP levels were found in deceased patients (75.25 mg/L, IQR: 48.55–78.63 vs 29.58 mg/L, IQR: 5.00–74.50; p = 0.203), the levels did not differ between survived and deceased patients. CK levels, however, were significantly higher in deceased patients (105.00 U/L, IQR: 69.00–165.00) compared with those who survived (37.00 U/L, IQR: 29.00–51.00; p = 0.019).

3.3 Differential influence of SARS-CoV-2 on circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes

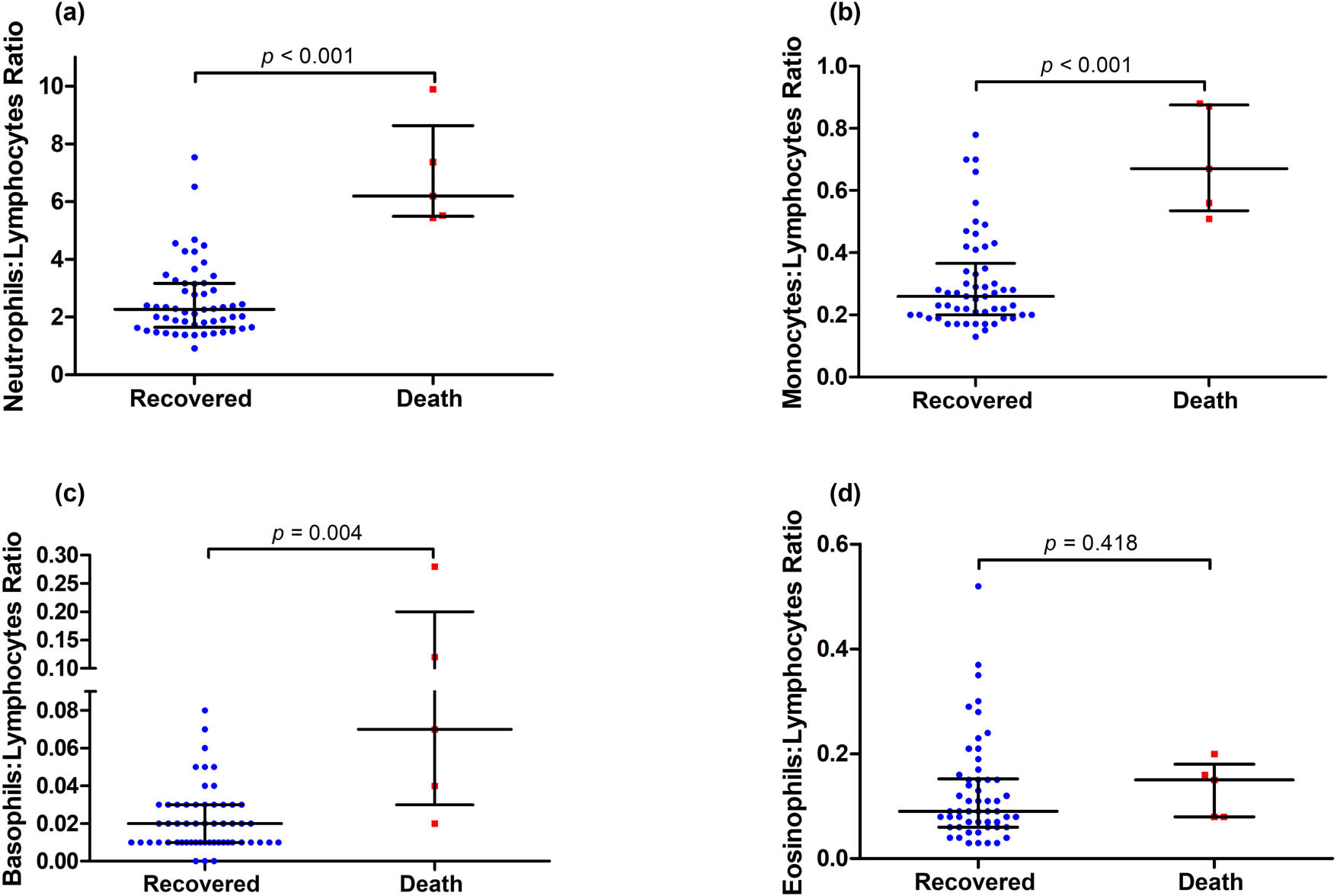

Given the different profiles of circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes from peripheral blood of survived and deceased patients (Table 2 and Figure 2), we further analyzed ratios of these two cell populations, including the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), basophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (BLR), and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (ELR). Strikingly, as shown in Figure 3, deceased patients had significantly higher ratios of myeloid cells over lymphocytes: NLR (6.19 vs 2.27; p < 0.001), MLR (0.67 vs 0.26; p < 0.001), and BLR (0.07 vs 0.02; p = 0.004). Of note, although the ELR appeared higher in deceased patients (0.15 vs 0.09; p = 0.418), the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 3d), likely due to the small sample size available for this study.

Ratios of myeloid cells and lymphocytes, including (a) neutrophil:lymphocyte, (b) monocyte:lymphocyte, (c) basophil:lymphocyte, and (d) eosinophil:lymphocyte, in deceased patients and those recovered from COVID-19. Data are presented as median ± IQR, and statistical analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

3.4 Correlation of D-dimer levels with circulating immune cell counts

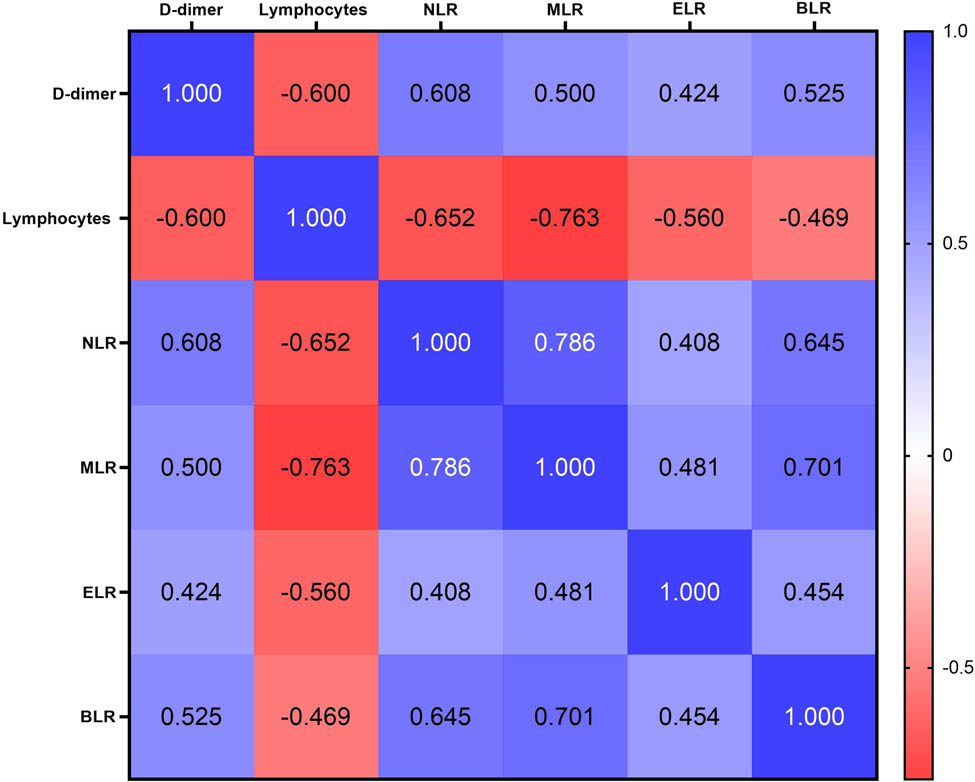

Since both coagulation parameters and the immune systems are disturbed in COVID-19, we analyzed the correlation between D-dimer levels and different immune cells (and their ratios). As shown in the correlation matrix (Figure 4), D-dimer levels were negatively correlated with lymphocyte counts (r = −0.600; p < 0.001), whereas there was no correlation between D-dimer levels and other immune cells including neutrophils, monocytes, basophils, and eosinophils. The correlations between D-dimer levels and the inflammatory marker CRP or the tissue damage marker CK were also analyzed but did not reach statistical significance. Intriguingly, D-dimer levels in COVID-19 patients were positively correlated with NLR (r = +0.608; p = 0.001), MLR (r = +0.500; p = 0.007), ELR (r = +0.424; p = 0.025), and BLR (r = +0.525; p = 0.004). These findings indicate that the imbalance between myeloid cells and lymphocyte counts is highly correlated with the pro-thrombotic state in COVID-19.

Correlation matrix showing the strength of correlation between D-dimer levels and inflammatory cells and ratios. Values in cells are Spearman correlation coefficient. All correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

4 Discussion

In this single-center retrospective study, we analyzed the clinical features, blood cells, coagulation parameters, and inflammatory markers of severe COVID-19 patients and uncovered that circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes were differentially affected. In particular, the ratios of myeloid cells and lymphocytes were overly associated with disease severity and highly correlated with the pro-thrombotic state in COVID-19.

The deceased patients in this study were older, predominantly male, and the majority had hypertension. These clinical features of severe COVID-19 patients are in agreement with previous reports [3,4,6]. Ageing commonly contributes to more severe COVID-19 and higher risk of death, which is likely associated with uncontrolled innate immune responses that cause cytokine storm and altered T cell responses [22]. The severity of COVID-19 was also reported to be inversely correlated with age in hospitalized children [23]. Recent studies also suggest that the phenotype and function of circulating monocytes, a type of innate immune cells, are changed in both aging and COVID-19 [24,25]. On top of the compromised immune system in aging population, comorbidities such as hypertension may explain the higher risk of death in elderly COVID-19 patients.

Activation of the immune systems has been well documented in viral infections including the SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 [26,27,28]. Neutrophilia and lymphopenia are associated with more severe disease symptoms and death in COVID-19 [29,30]. In agreement, we found higher counts of neutrophil and monocyte in deceased patients than in survived patients. In addition, we found lower lymphocyte counts in deceased patients. The differential changes in myeloid cells and lymphocytes result in markedly higher NLR, MLR, and BLR in deceased COVID-19 patients (Figure 3). The higher ratios of myeloid cells and lymphocytes in the more critically ill patients (deceased) may reflect the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Activation of neutrophils releases reactive oxygen species and cytokines as well as neutrophil extracellular traps, therefore, constitutes the first line of defense in response to viral infection [31,32]. Given the expression of virus-recognizing immune receptor, Toll-like receptor 7 [33], in monocytes, higher levels of monocytes in the blood may lead to over-reaction to SARS-CoV-2 infection. As Toll-like receptor 7 has been recently reported to deteriorate cardiovascular disease [34,35], higher levels of activated monocytes are expected to increase the risk of mortality in COVID-19 patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease [4,6,36]. Indeed, using high-dimensional flow cytometry analysis and single-cell RNA sequencing, Silvin et al. recently uncovered a disturbed balance between non-classical CD14LowCD16High monocytes and HLA-DRLow classical monocytes (Human Leukocyte Antigen-DR isotype) in the peripheral blood of severe COVID-19 patients [12]. Whether this change is associated with activation of monocytic Toll-like receptor 7 by SARS-CoV-2 is unknown. Nevertheless, uncontrolled activation of innate immune cells including neutrophils and monocytes may contribute to the detrimental cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients [6,8,37].

The majority of lymphocytes are T cells and B cells which constitute the major cellular components of adaptive immune system [38]. Given the emerging roles of T cells in COVID-19 and the critical role of B cells in producing antibodies [38], the lower levels of lymphocytes in deceased COVID-19 patients in the current study reflect a weaker adaptive immune response in fighting against SARS-CoV-2 infection. The significantly lower lymphocyte levels in deceased patients may be attributable to stress-induced apoptosis and exhaustion of antiviral lymphocytes [39]. In addition, the levels of circulating NK cells, a type of anti-viral innate immune cells which constitute a minor population of lymphocytes, also decrease in severe COVID-19 patients [15]. As a result, higher ratios of myeloid cells and lymphocytes (NLR, MLR, and BLR) indicate a more severe imbalance of innate and adaptive immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection and consequently an unfavorable outcome in such patients contracted with COVID-19. In agreement with our findings, the NLR was reported to be positively associated with disease severity in COVID-19 [40,41,42,43]. However, to our knowledge, no prior study has systemically assessed the ratios of different myeloid cell populations and lymphocytes in severe COVID-19.

Inflammatory responses have been associated with thrombotic and bleeding manifestations in sepsis [44,45]. In the context of COVID-19, early studies have shown the association between elevated D-dimer levels and mortality [4]. D-dimer is a fibrin degradation product, and it serves as a marker of fibrinolytic activity [46]. There is evidence that D-dimer correlates with proinflammatory cytokine levels in critically ill patients [47]. In consistence, majority of the patients in this study presented with D-dimer levels higher than the normal range. We did not find significant differences in D-dimer and CRP levels between deceased patients and recovered patients, as it is likely because all the patients included in this study were severe cases. However, by correlation matrix analysis, we found a significant correlation between D-dimer levels and the ratios of myeloid cells and lymphocytes (NLR, MLR, BLR, and ELR) as well as lymphocyte counts (Figure 4). This raises an open question: are the elevated D-dimers because of coagulopathy arising from viral infection, or are the imbalanced innate and adaptive immune responses attributable to activation of coagulation in viral infection? Further studies are warranted.

Besides coagulation parameters and inflammatory markers, we also observed a higher CK level in deceased patients compared with survived patients. Elevated CK levels were previously reported in the SARS and MERS outbreak [48]. Although rhabdomyolysis has been reported as potential late complication associated with COVID-19 [49], we did not have data regarding the symptoms of rhabdomyolysis in patients with elevated CK levels. The increase in CK levels may be attributed to hypovolemia that causes renal impairment in COVID-19 patients [50].

This study has several limitations. First, it is a single-center retrospective study with a small number of patients. Second, laboratory parameters were not complete for each individual patient and the number of deceased patients in this study is rather small, therefore, may result in underpowered statistical analysis. Furthermore, as only clinical laboratory data are available for this study, we are not able to analyze subpopulations of lymphocytes such as T-cells. Multi-center studies with a larger cohort of patients are therefore required to confirm our findings. Moreover, multi-dimensional analysis of subpopulations of immune cells will help to delineate the impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on innate and adaptive immunity in COVID-19. Nevertheless, given the fact that the overwhelming cases of COVID-19 lead to shortage of medical resources worldwide, our findings may facilitate the development of diagnostic protocols for patient stratification based on the routine laboratory tests available in most clinical laboratories.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, innate and adaptive immune systems were affected differentially among severe COVID-19 patients. Our findings suggest that the ratios of myeloid cells (except eosinophils) and lymphocytes are highly associated with pro-thrombotic state and disease severity in COVID-19 and may serve as potential biomarkers for risk stratification of COVID-19 patients, allowing early intensive care and support for those of higher risk of death.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Healthcare Technology Programme from the Health Commission of Tianjin (2020XKC07).

Appendix

Representative white blood cell differential fluorescence (WDF) scattergrams of (a) survived and (b) deceased patients from severe COVID-19.

-

Disclosure: The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

-

Data availability statements: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–33.10.1056/NEJMoa2001017Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Gralinski LE, Menachery VD. Return of the coronavirus: 2019-nCoV. Viruses. 2020;12(2):135.10.3390/v12020135Suche in Google Scholar

[3] Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–13.10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–20.10.1056/NEJMoa2002032Suche in Google Scholar

[5] World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports; 2020 [cited 28 August 2020]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reportsSuche in Google Scholar

[6] Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Sun Y, Koh V, Marimuthu K, Ng OT, Young B, Vasoo S, et al. Epidemiological and clinical predictors of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):786–92.10.1093/cid/ciaa322Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[8] Channappanavar R, Perlman S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39(5):529–39.10.1007/s00281-017-0629-xSuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[9] Gong F, Dai Y, Zheng T, Cheng L, Zhao D, Wang H, et al. Peripheral CD4+ T cell subsets and antibody response in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(12):6588–99.10.1172/JCI141054Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[10] Wilk AJ, Rustagi A, Zhao NQ, Roque J, Martínez-Colón GJ, McKechnie JL, et al. A single-cell atlas of the peripheral immune response in patients with severe COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(7):1070–6.10.1038/s41591-020-0944-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Chaplin DD. Overview of the immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(Suppl 2):S3–23.10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.980Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[12] Silvin A, Chapuis N, Dunsmore G, Goubet A-G, Dubuisson A, Derosa L, et al. Elevated calprotectin and abnormal myeloid cell subsets discriminate severe from mild COVID-19. Cell. 2020;182(6):1401–18.10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Agrati C, Sacchi A, Bordoni V, Cimini E, Notari S, Grassi G, et al. Expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with severe coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:3196–207.10.1038/s41418-020-0572-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Schulte-Schrepping J, Reusch N, Paclik D, Baßler K, Schlickeiser S, Zhang B, et al. Severe COVID-19 is marked by a dysregulated myeloid cell compartment. Cell. 2020;182(6):1419–40.10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.001Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[15] Market M, Angka L, Martel AB, Bastin D, Olanubi O, Tennakoon G, et al. Flattening the COVID-19 curve with natural killer cell based immunotherapies. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1512.10.3389/fimmu.2020.01512Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Chen Z, John, Wherry E. T cell responses in patients with COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(9):529–36.10.1038/s41577-020-0402-6Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Wang Z, He Y, Shu H, Wang P, Xing H, Zeng X, et al. High-fluorescent lymphocytes are increased in patients with COVID-19. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(2):e76–8.10.1111/bjh.16867Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[18] Campbell CM, Guha A, Haque T, Neilan TG, Addison D. Repurposing immunomodulatory therapies against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the era of cardiac vigilance: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):2935.10.3390/jcm9092935Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[19] Di Micco P, Di Micco G, Russo V, Poggiano MR, Salzano C, Bosevski M, et al. Blood targets of adjuvant drugs against COVID19. J Blood Med. 2020;11:237–41.10.2147/JBM.S256121Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[20] National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on the issuance of a programme for the diagnosis and treatment of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (Trial Version 4); 2020 [cited 28 August 2020]. Available from: http://bgs.satcm.gov.cn/zhengcewenjian/2020-01-28/12576.htmlSuche in Google Scholar

[21] Osman J, Lambert J, Templé M, Devaux F, Favre R, Flaujac C, et al. Rapid screening of COVID-19 patients using white blood cell scattergrams, a study on 381 patients. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(5):718–22.10.1111/bjh.16943Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[22] Meftahi GH, Jangravi Z, Sahraei H, Bahari Z. The possible pathophysiology mechanism of cytokine storm in elderly adults with COVID-19 infection: the contribution of “inflame-aging”. Inflamm Res. 2020;69(9):825–39.10.1007/s00011-020-01372-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Nathan N, Prevost B, Sileo C, Richard N, Berdah L, Thouvenin G, et al. The wide spectrum of COVID-19 clinical presentation in children. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):2950.10.3390/jcm9092950Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Merad M, Martin JC. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):355–62.10.1038/s41577-020-0331-4Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Pence BD. Severe COVID-19 and aging: are monocytes the key? Geroscience. 2020;42(4):1051–61.10.1007/s11357-020-00213-0Suche in Google Scholar

[26] Huang KJ, Su IJ, Theron M, Wu YC, Lai SK, Liu CC, et al. An interferon-gamma-related cytokine storm in SARS patients. J Med Virol. 2005;75(2):185–94.10.1002/jmv.20255Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, Zhang C, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(4):420–2.10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-XSuche in Google Scholar

[28] Kothari A, Singh V, Nath UK, Kumar S, Rai V, Kaushal K, et al. Immune dysfunction and multiple treatment modalities for the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: races of uncontrolled running sweat? Biology. 2020;9(9):243.10.3390/biology9090243Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[29] Feng X, Li S, Sun Q, Zhu J, Chen B, Xiong M, et al. Immune-inflammatory parameters in COVID-19 cases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med. 2020;7:301.10.3389/fmed.2020.00301Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Wan S, Xiang Y, Fang W, Zheng Y, Li B, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):797–806.10.1002/jmv.25783Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[31] Agraz-Cibrian JM, Giraldo DM, Mary FM, Urcuqui-Inchima S. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of NETs and their role in antiviral innate immunity. Virus Res. 2017;228:124–33.10.1016/j.virusres.2016.11.033Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] Muraro SP, De Souza GF, Gallo SW, Da Silva BK, De Oliveira SD, Vinolo MAR, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus induces the classical ROS-dependent NETosis through PAD-4 and necroptosis pathways activation. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14166.10.1038/s41598-018-32576-ySuche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[33] Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Innate antiviral responses by means of TLR7-mediated recognition of single-stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303(5663):1529–31.10.1126/science.1093616Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[34] de Kleijn DPV, Chong SY, Wang X, Yatim S, Fairhurst AM, Vernooij F, et al. Toll-like receptor 7 deficiency promotes survival and reduces adverse left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2019;115(12):1791–803.10.1093/cvr/cvz057Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[35] Karadimou G, Plunde O, Pawelzik S-C, Carracedo M, Eriksson P, Franco-Cereceda A, et al. TLR7 expression is associated with M2 macrophage subset in calcific aortic valve stenosis. Cells. 2020;9(7):1710.10.3390/cells9071710Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[36] Nishiga M, Wang DW, Han Y, Lewis DB, Wu JC. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease: from basic mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(9):543–58.10.1038/s41569-020-0413-9Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[37] Zhou Y, Fu B, Zheng X, Wang D, Zhao C, Qi Y, et al. Pathogenic T-cells and inflammatory monocytes incite inflammatory storms in severe COVID-19 patients. Natl Sci Rev. 2020;7(6):998–1002.10.1093/nsr/nwaa041Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Tay MZ, Poh CM, Rénia L, MacAry PA, Ng LFP. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):363–74.10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[39] Zheng M, Gao Y, Wang G, Song G, Liu S, Sun D, et al. Functional exhaustion of antiviral lymphocytes in COVID-19 patients. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(5):533–5.10.1038/s41423-020-0402-2Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[40] Qun S, Wang Y, Chen J, Huang X, Guo H, Lu Z, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios are closely associated with the severity and course of non-mild COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:2160.10.3389/fimmu.2020.02160Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Yang AP, Liu JP, Tao WQ, Li HM. The diagnostic and predictive role of NLR, d-NLR and PLR in COVID-19 patients. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;84:106504.10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106504Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[42] Chan AS, Rout A. Use of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios in COVID-19. J Clin Med Res. 2020;12(7):448–53.10.14740/jocmr4240Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Vafadar Moradi E, Teimouri A, Rezaee R, Morovatdar N, Foroughian M, Layegh P, et al. Increased age, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and white blood cells count are associated with higher COVID-19 mortality. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;40:11–4.10.1016/j.ajem.2020.12.003Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[44] Delabranche X, Helms J, Meziani F. Immunohaemostasis: a new view on haemostasis during sepsis. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7(1):117.10.1186/s13613-017-0339-5Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[45] Iba T, Levy JH. Inflammation and thrombosis: roles of neutrophils, platelets and endothelial cells and their interactions in thrombus formation during sepsis. J Thrombosis Haemost. 2018;16(2):231–41.10.1111/jth.13911Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[46] Soomro AY, Guerchicoff A, Nichols DJ, Suleman J, Dangas GD. The current role and future prospects of D-dimer biomarker. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2015;2(3):175–84.10.1093/ehjcvp/pvv039Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Shorr AF, Thomas SJ, Alkins SA, Fitzpatrick TM, Ling GS. D-dimer correlates with proinflammatory cytokine levels and outcomes in critically ill patients. Chest. 2002;121(4):1262–8.10.1378/chest.121.4.1262Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[48] Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, Chan P, Cameron P, Joynt GM, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(20):1986–94.10.1056/NEJMoa030685Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[49] Jin M, Tong Q. Rhabdomyolysis as potential late complication associated with COVID-19. Emerg Infect Dis J. 2020;26(7):1618.10.3201/eid2607.200445Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[50] Rivas-García S, Bernal J, Bachiller-Corral J. Rhabdomyolysis as the main manifestation of coronavirus disease 2019. Rheumatology. 2020;59(8):2174–6.10.1093/rheumatology/keaa351Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2021 Hui Ma et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells

- Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 in healthy paediatric population

- Algorithm of rational approach to reconstruction in Fournier’s disease

- A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury

- Src-1 and SP2 promote the proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Dexmedetomidine may decrease the bupivacaine toxicity to heart

- Hypoxia stimulates the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma via up-regulating the NUSAP1 expression

- Long noncoding RNA XIST knockdown relieves the injury of microglia cells after spinal cord injury by sponging miR-219-5p

- External fixation via the anterior inferior iliac spine for proximal femoral fractures in young patients

- miR-128-3p reduced acute lung injury induced by sepsis via targeting PEL12

- HAGLR promotes neuron differentiation through the miR-130a-3p-MeCP2 axis

- Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 is elevated in serum of patients with heart failure and correlates with the disease severity and patient’s prognosis

- Cell population data in identifying active tuberculosis and community-acquired pneumonia

- Prognostic value of microRNA-4521 in non-small cell lung cancer and its regulatory effect on tumor progression

- Mean platelet volume and red blood cell distribution width is associated with prognosis in premature neonates with sepsis

- 3D-printed porous scaffold promotes osteogenic differentiation of hADMSCs

- Association of gene polymorphisms with women urinary incontinence

- Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels of urologic patients

- miR-496 inhibits proliferation via LYN and AKT pathway in gastric cancer

- miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development

- Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- Fluorescent light energy modulates healing in skin grafted mouse model

- Silencing CDK6-AS1 inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory damage in HK-2 cells

- Predictive effect of DCE-MRI and DWI in brain metastases from NSCLC

- Severe postoperative hyperbilirubinemia in congenital heart disease

- Baicalin improves podocyte injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

- Clinical factors predicting ureteral stent failure in patients with external ureteral compression

- Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway

- Triple-Endobutton and clavicular hook: A propensity score matching analysis

- Long noncoding RNA MIAT inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy and the activation of NF-κB pathway in high glucose-treated renal tubular epithelial cells by the miR-182-5p/GPRC5A axis

- Serum exosomal miR-122-5p, GAS, and PGR in the non-invasive diagnosis of CAG

- miR-513b-5p inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells by targeting TRIB1

- Fer exacerbates renal fibrosis and can be targeted by miR-29c-3p

- The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-92a in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prognostic value of α2δ1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study

- No significant benefit of moderate-dose vitamin C on severe COVID-19 cases

- circ_0000467 promotes the proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating KLF12 expression by sponging miR-4766-5p

- Downregulation of RAB7 and Caveolin-1 increases MMP-2 activity in renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxic conditions

- Educational program for orthopedic surgeons’ influences for osteoporosis

- Expression and function analysis of CRABP2 and FABP5, and their ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

- lncRNA-ZFAS1 promotes the progression of endometrial carcinoma by targeting miR-34b to regulate VEGFA expression

- Anticoagulation is the answer in treating noncritical COVID-19 patients

- Effect of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis on PFS after haplo-PBSCT

- Comparison of Dako HercepTest and Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2 (4B5) tests and their correlation with silver in situ hybridization in lung adenocarcinoma

- VSTM1 regulates monocyte/macrophage function via the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Comparison of vaginal birth outcomes in midwifery-led versus physician-led setting: A propensity score-matched analysis

- Treatment of osteoporosis with teriparatide: The Slovenian experience

- New targets of morphine postconditioning protection of the myocardium in ischemia/reperfusion injury: Involvement of HSP90/Akt and C5a/NF-κB

- Superenhancer–transcription factor regulatory network in malignant tumors

- β-Cell function is associated with osteosarcopenia in middle-aged and older nonobese patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study

- Clinical features of atypical tuberculosis mimicking bacterial pneumonia

- Proteoglycan-depleted regions of annular injury promote nerve ingrowth in a rabbit disc degeneration model

- Effect of electromagnetic field on abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- miR-150-5p affects AS plaque with ASMC proliferation and migration by STAT1

- MALAT1 promotes malignant pleural mesothelioma by sponging miR-141-3p

- Effects of remifentanil and propofol on distant organ lung injury in an ischemia–reperfusion model

- miR-654-5p promotes gastric cancer progression via the GPRIN1/NF-κB pathway

- Identification of LIG1 and LIG3 as prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer

- MitoQ inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis by enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy

- Dissecting role of founder mutation p.V727M in GNE in Indian HIBM cohort

- circATP2A2 promotes osteosarcoma progression by upregulating MYH9

- Prognostic role of oxytocin receptor in colon adenocarcinoma

- Review Articles

- The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Efficacy and safety of therapeutic plasma exchange in stiff person syndrome

- Role of cesarean section in the development of neonatal gut microbiota: A systematic review

- Small cell lung cancer transformation during antitumor therapies: A systematic review

- Research progress of gut microbiota and frailty syndrome

- Recommendations for outpatient activity in COVID-19 pandemic

- Rapid Communication

- Disparity in clinical characteristics between 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia and leptospirosis

- Use of microspheres in embolization for unruptured renal angiomyolipomas

- COVID-19 cases with delayed absorption of lung lesion

- A triple combination of treatments on moderate COVID-19

- Social networks and eating disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Letter

- COVID-19, WHO guidelines, pedagogy, and respite

- Inflammatory factors in alveolar lavage fluid from severe COVID-19 pneumonia: PCT and IL-6 in epithelial lining fluid

- COVID-19: Lessons from Norway tragedy must be considered in vaccine rollout planning in least developed/developing countries

- What is the role of plasma cell in the lamina propria of terminal ileum in Good’s syndrome patient?

- Case Report

- Rivaroxaban triggered multifocal intratumoral hemorrhage of the cabozantinib-treated diffuse brain metastases: A case report and review of literature

- CTU findings of duplex kidney in kidney: A rare duplicated renal malformation

- Synchronous primary malignancy of colon cancer and mantle cell lymphoma: A case report

- Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography and pathologic characters of CD68 positive cell in primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: A case report and literature review

- Persistent SARS-CoV-2-positive over 4 months in a COVID-19 patient with CHB

- Pulmonary parenchymal involvement caused by Tropheryma whipplei

- Mediastinal mixed germ cell tumor: A case report and literature review

- Ovarian female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin – Case report

- Rare paratesticular aggressive angiomyxoma mimicking an epididymal tumor in an 82-year-old man: Case report

- Perimenopausal giant hydatidiform mole complicated with preeclampsia and hyperthyroidism: A case report and literature review

- Primary orbital ganglioneuroblastoma: A case report

- Primary aortic intimal sarcoma masquerading as intramural hematoma

- Sustained false-positive results for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M: A case report and literature review

- Peritoneal loose body presenting as a hepatic mass: A case report and review of the literature

- Chondroblastoma of mandibular condyle: Case report and literature review

- Trauma-induced complete pacemaker lead fracture 8 months prior to hospitalization: A case report

- Primary intradural extramedullary extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PIEES/PNET) of the thoracolumbar spine: A case report and literature review

- Computer-assisted preoperative planning of reduction of and osteosynthesis of scapular fracture: A case report

- High quality of 58-month life in lung cancer patient with brain metastases sequentially treated with gefitinib and osimertinib

- Rapid response of locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma to apatinib: A case report

- Retrieval of intrarenal coiled and ruptured guidewire by retrograde intrarenal surgery: A case report and literature review

- Usage of intermingled skin allografts and autografts in a senior patient with major burn injury

- Retraction

- Retraction on “Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappa B pathway”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part I

- An artificial immune system with bootstrap sampling for the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial cancers

- Breast cancer recurrence prediction with ensemble methods and cost-sensitive learning

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Research Articles

- Identification of ZG16B as a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer

- Behçet’s disease with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

- Erratum

- Erratum to “Suffering from Cerebral Small Vessel Disease with and without Metabolic Syndrome”

- Research Articles

- GPR37 promotes the malignancy of lung adenocarcinoma via TGF-β/Smad pathway

- Expression and role of ABIN1 in sepsis: In vitro and in vivo studies

- Additional baricitinib loading dose improves clinical outcome in COVID-19

- The co-treatment of rosuvastatin with dapagliflozin synergistically inhibited apoptosis via activating the PI3K/AKt/mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury rats

- SLC12A8 plays a key role in bladder cancer progression and EMT

- LncRNA ATXN8OS enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer

- Case Report

- Serratia marcescens as a cause of unfavorable outcome in the twin pregnancy

- Spleno-adrenal fusion mimicking an adrenal metastasis of a renal cell carcinoma: A case report and embryological background

- Research Articles

- TRIM25 contributes to the malignancy of acute myeloid leukemia and is negatively regulated by microRNA-137

- CircRNA circ_0004370 promotes cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and inhibits cell apoptosis of esophageal cancer via miR-1301-3p/COL1A1 axis

- LncRNA XIST regulates atherosclerosis progression in ox-LDL-induced HUVECs

- Potential role of IFN-γ and IL-5 in sepsis prediction of preterm neonates

- Rapid Communication

- COVID-19 vaccine: Call for employees in international transportation industries and international travelers as the first priority in global distribution

- Case Report

- Rare squamous cell carcinoma of the kidney with concurrent xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis: A case report and review of the literature

- An infertile female delivered a baby after removal of primary renal carcinoid tumor

- Research Articles

- Hypertension, BMI, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases

- Case Report

- Coexistence of bilateral macular edema and pale optic disc in the patient with Cohen syndrome

- Research Articles

- Correlation between kinematic sagittal parameters of the cervical lordosis or head posture and disc degeneration in patients with posterior neck pain

- Review Articles

- Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung: An analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database

- Research Articles

- Thermography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome

- Pemetrexed-based first-line chemotherapy had particularly prominent objective response rate for advanced NSCLC: A network meta-analysis

- Comparison of single and double autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma patients

- The influence of smoking in minimally invasive spinal fusion surgery

- Impact of body mass index on left atrial dimension in HOCM patients

- Expression and clinical significance of CMTM1 in hepatocellular carcinoma

- miR-142-5p promotes cervical cancer progression by targeting LMX1A through Wnt/β-catenin pathway

- Comparison of multiple flatfoot indicators in 5–8-year-old children

- Early MRI imaging and follow-up study in cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Intestinal fatty acid-binding protein as a biomarker for the diagnosis of strangulated intestinal obstruction: A meta-analysis

- miR-128-3p inhibits apoptosis and inflammation in LPS-induced sepsis by targeting TGFBR2

- Dynamic perfusion CT – A promising tool to diagnose pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- Biomechanical evaluation of self-cinching stitch techniques in rotator cuff repair: The single-loop and double-loop knot stitches

- Review Articles

- The ambiguous role of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in human immunity

- Case Report

- Membranous nephropathy with pulmonary cryptococcosis with improved 1-year follow-up results: A case report

- Fertility problems in males carrying an inversion of chromosome 10

- Acute myeloid leukemia with leukemic pleural effusion and high levels of pleural adenosine deaminase: A case report and review of literature

- Metastatic renal Ewing’s sarcoma in adult woman: Case report and review of the literature

- Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration in a patient with AIDS and a patient without AIDS: Two cases reports and literature review

- Skull hemophilia pseudotumor: A case report

- Judicious use of low-dosage corticosteroids for non-severe COVID-19: A case report

- Adult-onset citrullinaemia type II with liver cirrhosis: A rare cause of hyperammonaemia

- Clinicopathologic features of Good’s syndrome: Two cases and literature review

- Fatal immune-related hepatitis with intrahepatic cholestasis and pneumonia associated with camrelizumab: A case report and literature review

- Research Articles

- Effects of hydroxyethyl starch and gelatin on the risk of acute kidney injury following orthotopic liver transplantation: A multicenter retrospective comparative clinical study

- Significance of nucleic acid positive anal swab in COVID-19 patients

- circAPLP2 promotes colorectal cancer progression by upregulating HELLS by targeting miR-335-5p

- Ratios between circulating myeloid cells and lymphocytes are associated with mortality in severe COVID-19 patients

- Risk factors of left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation

- Clinical features of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 compared with a normotensive group: Single-center experience in China

- Surgical myocardial revascularization outcomes in Kawasaki disease: systematic review and meta-analysis

- Decreased chromobox homologue 7 expression is associated with epithelial–mesenchymal transition and poor prognosis in cervical cancer

- FGF16 regulated by miR-520b enhances the cell proliferation of lung cancer

- Platelet-rich fibrin: Basics of biological actions and protocol modifications

- Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer using logistic regression

- miR-377 inhibition enhances the survival of trophoblast cells via upregulation of FNDC5 in gestational diabetes mellitus

- Prognostic significance of TRIM28 expression in patients with breast carcinoma

- Integrative bioinformatics analysis of KPNA2 in six major human cancers

- Exosomal-mediated transfer of OIP5-AS1 enhanced cell chemoresistance to trastuzumab in breast cancer via up-regulating HMGB3 by sponging miR-381-3p

- A four-lncRNA signature for predicting prognosis of recurrence patients with gastric cancer

- Knockdown of circ_0003204 alleviates oxidative low-density lipoprotein-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells injury: Circulating RNAs could explain atherosclerosis disease progression

- Propofol postpones colorectal cancer development through circ_0026344/miR-645/Akt/mTOR signal pathway

- Knockdown of lncRNA TapSAKI alleviates LPS-induced injury in HK-2 cells through the miR-205/IRF3 pathway

- COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use

- Clinical analysis of 11 cases of nocardiosis

- Cis-regulatory elements in conserved non-coding sequences of nuclear receptor genes indicate for crosstalk between endocrine systems

- Four long noncoding RNAs act as biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma

- Real-world evidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphomas treated with bendamustine-containing regimens

- Relation between IL-8 level and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- circAGFG1 sponges miR-28-5p to promote non-small-cell lung cancer progression through modulating HIF-1α level

- Nomogram prediction model for renal anaemia in IgA nephropathy patients

- Effect of antibiotic use on the efficacy of nivolumab in the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- NDRG2 inhibition facilitates angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- A nomogram for predicting metabolic steatohepatitis: The combination of NAMPT, RALGDS, GADD45B, FOSL2, RTP3, and RASD1

- Clinical and prognostic features of MMP-2 and VEGF in AEG patients

- The value of miR-510 in the prognosis and development of colon cancer

- Functional implications of PABPC1 in the development of ovarian cancer

- Prognostic value of preoperative inflammation-based predictors in patients with bladder carcinoma after radical cystectomy

- Sublingual immunotherapy increases Treg/Th17 ratio in allergic rhinitis

- Prediction of improvement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

- Effluent Osteopontin levels reflect the peritoneal solute transport rate

- circ_0038467 promotes PM2.5-induced bronchial epithelial cell dysfunction

- Significance of miR-141 and miR-340 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- Association between hair cortisol concentration and metabolic syndrome

- Microvessel density as a prognostic indicator of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Characteristics of BCR–ABL gene variants in patients of chronic myeloid leukemia

- Knee alterations in rheumatoid arthritis: Comparison of US and MRI

- Long non-coding RNA TUG1 aggravates cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury by sponging miR-493-3p/miR-410-3p

- lncRNA MALAT1 regulated ATAD2 to facilitate retinoblastoma progression via miR-655-3p

- Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting severity in patients with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: A retrospective study

- Analysis of COVID-19 outbreak origin in China in 2019 using differentiation method for unusual epidemiological events

- Laparoscopic versus open major liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: A case-matched analysis of short- and long-term outcomes

- Travelers’ vaccines and their adverse events in Nara, Japan

- Association between Tfh and PGA in children with Henoch–Schönlein purpura

- Can exchange transfusion be replaced by double-LED phototherapy?

- circ_0005962 functions as an oncogene to aggravate NSCLC progression

- Circular RNA VANGL1 knockdown suppressed viability, promoted apoptosis, and increased doxorubicin sensitivity through targeting miR-145-5p to regulate SOX4 in bladder cancer cells

- Serum intact fibroblast growth factor 23 in healthy paediatric population

- Algorithm of rational approach to reconstruction in Fournier’s disease

- A meta-analysis of exosome in the treatment of spinal cord injury

- Src-1 and SP2 promote the proliferation and epithelial–mesenchymal transition of nasopharyngeal carcinoma

- Dexmedetomidine may decrease the bupivacaine toxicity to heart

- Hypoxia stimulates the migration and invasion of osteosarcoma via up-regulating the NUSAP1 expression

- Long noncoding RNA XIST knockdown relieves the injury of microglia cells after spinal cord injury by sponging miR-219-5p

- External fixation via the anterior inferior iliac spine for proximal femoral fractures in young patients

- miR-128-3p reduced acute lung injury induced by sepsis via targeting PEL12

- HAGLR promotes neuron differentiation through the miR-130a-3p-MeCP2 axis

- Phosphoglycerate mutase 2 is elevated in serum of patients with heart failure and correlates with the disease severity and patient’s prognosis

- Cell population data in identifying active tuberculosis and community-acquired pneumonia

- Prognostic value of microRNA-4521 in non-small cell lung cancer and its regulatory effect on tumor progression

- Mean platelet volume and red blood cell distribution width is associated with prognosis in premature neonates with sepsis

- 3D-printed porous scaffold promotes osteogenic differentiation of hADMSCs

- Association of gene polymorphisms with women urinary incontinence

- Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on stress levels of urologic patients

- miR-496 inhibits proliferation via LYN and AKT pathway in gastric cancer

- miR-519d downregulates LEP expression to inhibit preeclampsia development

- Comparison of single- and triple-port VATS for lung cancer: A meta-analysis

- Fluorescent light energy modulates healing in skin grafted mouse model

- Silencing CDK6-AS1 inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory damage in HK-2 cells

- Predictive effect of DCE-MRI and DWI in brain metastases from NSCLC

- Severe postoperative hyperbilirubinemia in congenital heart disease

- Baicalin improves podocyte injury in rats with diabetic nephropathy by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

- Clinical factors predicting ureteral stent failure in patients with external ureteral compression

- Novel H2S donor proglumide-ADT-OH protects HUVECs from ox-LDL-induced injury through NF-κB and JAK/SATA pathway

- Triple-Endobutton and clavicular hook: A propensity score matching analysis

- Long noncoding RNA MIAT inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy and the activation of NF-κB pathway in high glucose-treated renal tubular epithelial cells by the miR-182-5p/GPRC5A axis

- Serum exosomal miR-122-5p, GAS, and PGR in the non-invasive diagnosis of CAG

- miR-513b-5p inhibits the proliferation and promotes apoptosis of retinoblastoma cells by targeting TRIB1

- Fer exacerbates renal fibrosis and can be targeted by miR-29c-3p

- The diagnostic and prognostic value of miR-92a in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Prognostic value of α2δ1 in hypopharyngeal carcinoma: A retrospective study

- No significant benefit of moderate-dose vitamin C on severe COVID-19 cases

- circ_0000467 promotes the proliferation, metastasis, and angiogenesis in colorectal cancer cells through regulating KLF12 expression by sponging miR-4766-5p

- Downregulation of RAB7 and Caveolin-1 increases MMP-2 activity in renal tubular epithelial cells under hypoxic conditions

- Educational program for orthopedic surgeons’ influences for osteoporosis

- Expression and function analysis of CRABP2 and FABP5, and their ratio in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- GJA1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by mediating TGF-β-induced activation and the epithelial–mesenchymal transition of hepatic stellate cells

- lncRNA-ZFAS1 promotes the progression of endometrial carcinoma by targeting miR-34b to regulate VEGFA expression

- Anticoagulation is the answer in treating noncritical COVID-19 patients

- Effect of late-onset hemorrhagic cystitis on PFS after haplo-PBSCT

- Comparison of Dako HercepTest and Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2 (4B5) tests and their correlation with silver in situ hybridization in lung adenocarcinoma

- VSTM1 regulates monocyte/macrophage function via the NF-κB signaling pathway

- Comparison of vaginal birth outcomes in midwifery-led versus physician-led setting: A propensity score-matched analysis

- Treatment of osteoporosis with teriparatide: The Slovenian experience

- New targets of morphine postconditioning protection of the myocardium in ischemia/reperfusion injury: Involvement of HSP90/Akt and C5a/NF-κB

- Superenhancer–transcription factor regulatory network in malignant tumors

- β-Cell function is associated with osteosarcopenia in middle-aged and older nonobese patients with type 2 diabetes: A cross-sectional study

- Clinical features of atypical tuberculosis mimicking bacterial pneumonia

- Proteoglycan-depleted regions of annular injury promote nerve ingrowth in a rabbit disc degeneration model

- Effect of electromagnetic field on abortion: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- miR-150-5p affects AS plaque with ASMC proliferation and migration by STAT1

- MALAT1 promotes malignant pleural mesothelioma by sponging miR-141-3p

- Effects of remifentanil and propofol on distant organ lung injury in an ischemia–reperfusion model

- miR-654-5p promotes gastric cancer progression via the GPRIN1/NF-κB pathway

- Identification of LIG1 and LIG3 as prognostic biomarkers in breast cancer

- MitoQ inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis by enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy

- Dissecting role of founder mutation p.V727M in GNE in Indian HIBM cohort

- circATP2A2 promotes osteosarcoma progression by upregulating MYH9

- Prognostic role of oxytocin receptor in colon adenocarcinoma

- Review Articles

- The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- Efficacy and safety of therapeutic plasma exchange in stiff person syndrome

- Role of cesarean section in the development of neonatal gut microbiota: A systematic review

- Small cell lung cancer transformation during antitumor therapies: A systematic review

- Research progress of gut microbiota and frailty syndrome

- Recommendations for outpatient activity in COVID-19 pandemic

- Rapid Communication

- Disparity in clinical characteristics between 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia and leptospirosis

- Use of microspheres in embolization for unruptured renal angiomyolipomas

- COVID-19 cases with delayed absorption of lung lesion

- A triple combination of treatments on moderate COVID-19

- Social networks and eating disorders during the Covid-19 pandemic

- Letter

- COVID-19, WHO guidelines, pedagogy, and respite

- Inflammatory factors in alveolar lavage fluid from severe COVID-19 pneumonia: PCT and IL-6 in epithelial lining fluid

- COVID-19: Lessons from Norway tragedy must be considered in vaccine rollout planning in least developed/developing countries

- What is the role of plasma cell in the lamina propria of terminal ileum in Good’s syndrome patient?

- Case Report

- Rivaroxaban triggered multifocal intratumoral hemorrhage of the cabozantinib-treated diffuse brain metastases: A case report and review of literature

- CTU findings of duplex kidney in kidney: A rare duplicated renal malformation

- Synchronous primary malignancy of colon cancer and mantle cell lymphoma: A case report

- Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography and pathologic characters of CD68 positive cell in primary hepatic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors: A case report and literature review

- Persistent SARS-CoV-2-positive over 4 months in a COVID-19 patient with CHB

- Pulmonary parenchymal involvement caused by Tropheryma whipplei

- Mediastinal mixed germ cell tumor: A case report and literature review

- Ovarian female adnexal tumor of probable Wolffian origin – Case report

- Rare paratesticular aggressive angiomyxoma mimicking an epididymal tumor in an 82-year-old man: Case report

- Perimenopausal giant hydatidiform mole complicated with preeclampsia and hyperthyroidism: A case report and literature review

- Primary orbital ganglioneuroblastoma: A case report

- Primary aortic intimal sarcoma masquerading as intramural hematoma

- Sustained false-positive results for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin M: A case report and literature review

- Peritoneal loose body presenting as a hepatic mass: A case report and review of the literature

- Chondroblastoma of mandibular condyle: Case report and literature review

- Trauma-induced complete pacemaker lead fracture 8 months prior to hospitalization: A case report

- Primary intradural extramedullary extraosseous Ewing’s sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PIEES/PNET) of the thoracolumbar spine: A case report and literature review

- Computer-assisted preoperative planning of reduction of and osteosynthesis of scapular fracture: A case report

- High quality of 58-month life in lung cancer patient with brain metastases sequentially treated with gefitinib and osimertinib

- Rapid response of locally advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma to apatinib: A case report

- Retrieval of intrarenal coiled and ruptured guidewire by retrograde intrarenal surgery: A case report and literature review

- Usage of intermingled skin allografts and autografts in a senior patient with major burn injury

- Retraction

- Retraction on “Dihydromyricetin attenuates inflammation through TLR4/NF-kappa B pathway”

- Special Issue Computational Intelligence Methodologies Meets Recurrent Cancers - Part I

- An artificial immune system with bootstrap sampling for the diagnosis of recurrent endometrial cancers