Abstract

Plant antioxidants can be applied in the management of various human diseases. Despite these, extraction of these compounds still suffers from residual solvent impurities, low recovery yields, and the risks of undesirable chemical changes. Inspired by the protein–lipid interactions in the cell membranes, we proposed using poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) (PSMA) to destabilize and associate with the bilayer lipids into the membrane-like nanodiscs. Such nanostructures could serve as protective reservoirs for the active compounds to reside with preserved bioactivities. This concept was demonstrated in the antioxidant extraction from robusta coffee leaves. Results indicated that aqueous PSMA extraction (no buffer agent) yielded products with the highest contents of phenolic acids (11.6 mg GAE·g−1) and flavonoids (9.6 mg CE·g−1). They also showed the highest antioxidant activity (IC50 = 3.7 µg·mL−1) compared to those obtained by typical sodium dodecyl sulfate and water extraction. This biomimetic approach could be considered for developing environmentally friendly extraction protocols in the future.

1 Introduction

Plants produce a variety of bioactive metabolites for different purposes. Their primary metabolites, including nucleic acids, sugars, lipids, and amino acids, are essential compounds needed for plant growth and development. Secondary metabolites are not essential for the survival of plants, but they play an important role in plant defensive mechanisms and adaptation to fluctuating environments. Based on the chemical structure, plant secondary metabolites can be classified into three groups: terpenes, alkaloids, and phenolic compounds. Plant phenolics are composed of a hydroxyl functional group attached to an aromatic ring. They are produced by plants as a chemical defense against natural enemies. Due to their excellent electron donation, the compounds exhibit impressive antioxidant activity under both in vitro and in vivo conditions (1). Plant flavonoids, the largest group of naturally-occurring phenolic compounds, are one of the best antioxidant food supplements for human health. The global demand for plant flavonoids in 2024 was expected to reach USD 1.33 billion (2).

Extraction of plant antioxidants is generally performed in liquid solvents, either by maceration, soxhlet extraction, or heat reflux. The extraction efficiency depends on the increased mass transfer, solvent type, and energy input. Due to the toxicological concerns for human health and the environment, replacing organic solvents with less toxic media has always received considerable attention in the last few years. Water extraction is one of the most promising candidates for the extraction of plant phenolics. The method is readily available, cheap, recyclable, eco-friendly, and non-toxic. Nonetheless, the technique is quite limited in the case of moderate- or low-polarity compounds. To overcome this drawback, combined use of water and a surfactant, such as Triton-X, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide, or poly(ethylene glycol), was suggested (3,4,5,6). One of the most promising models depicting surfactant-assisted extraction of cellular biomolecules was proposed by Kalipatnapu and Chattopadhyay (7) and Lichtenberg et al. (8). In this model, molecules of surfactants were believed to be adsorbed onto the outer layers of biological membranes. Depending on their concentration and hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity balance, they can further flip into the lipid membranes and create micro-pore defects in the bilayer structure. This step is usually accompanied by a slow leakage of cytoplasmic components, such as soluble proteins, mitochondria, chloroplasts, and plant secondary metabolites. Although surfactant-assisted extraction is cheap and convenient, it has been considered to exhibit complex dependency on different parameters, such as pH, energy input, extraction time, ionic strength, surfactant concentration, and lipophilicity values. With a large number of factors to be optimized, the technique becomes less accessible and inefficient (3). Furthermore, traditional micellar extraction is a time-consuming process with several steps to be undertaken. A microwave-assisted micellar extraction technique was thereafter developed to resolve the issues. Previous work revealed a shortened extraction time with improved extraction yields when using a combined technique (9,10). Nonetheless, long-time exposure to microwave radiation may induce structural changes and thermal decomposition in phenolic compounds, causing them to lose their biological functions.

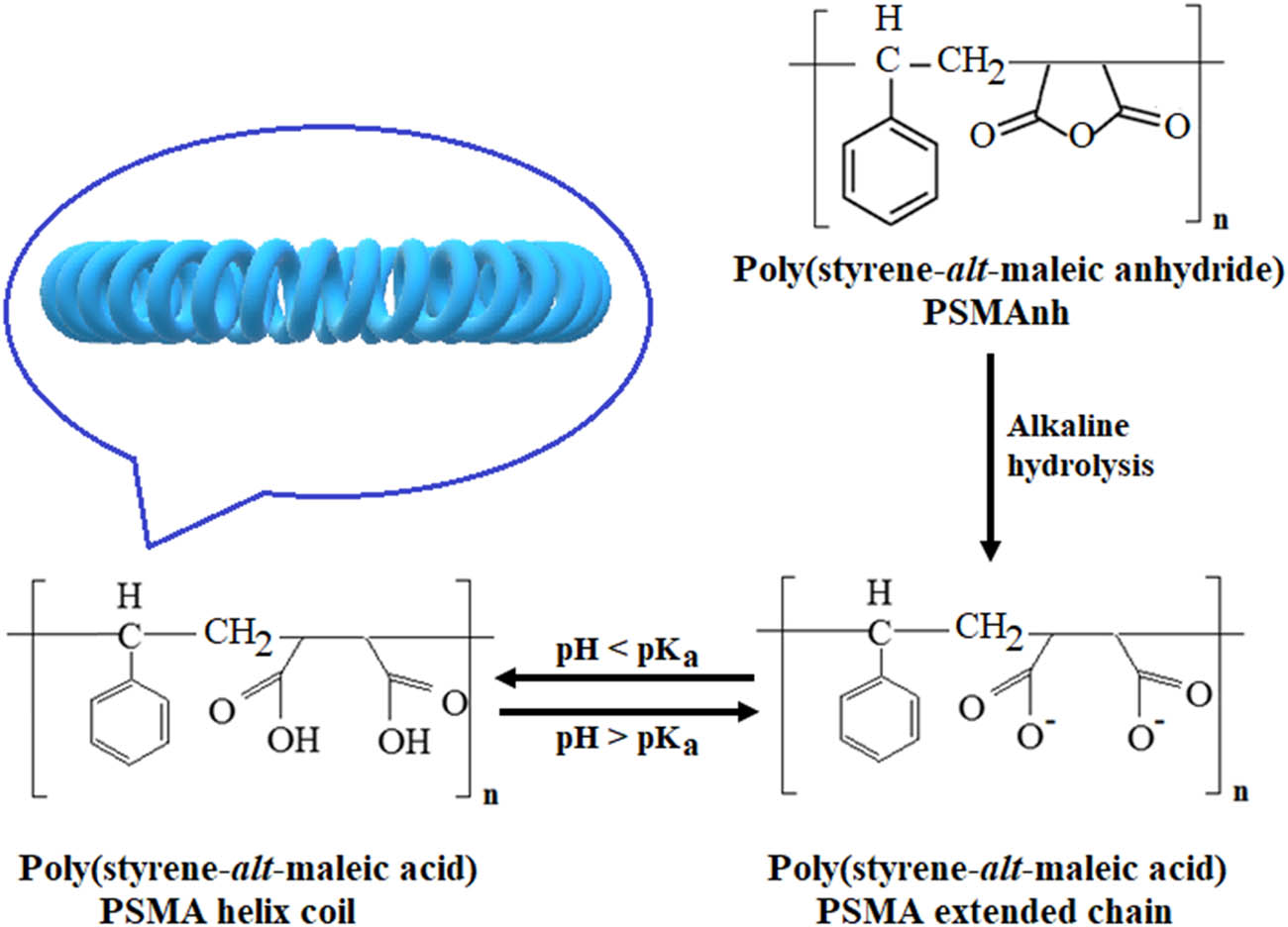

Poly(styrene-alt-maleic anhydride) (PSMAnh) has emerged as a promising surface-active agent in cell membrane disruption. The polymer is normally synthesized by solution radical polymerization using an equimolar ratio of styrene (St) to maleic anhydride (MAnh). Due to the high reactivity of the anhydride ring toward nucleophilic reagents, PSMAnh can be hydrolyzed into poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) (PSMA) or PSMA (Figure 1). Unlike PSMAnh, PSMA is water-soluble, making it more suitable for a green extraction process. One of the most interesting properties of PSMA is its ability to undergo a conformation transition upon pH adjustment. Above its acid dissociation constant value (pH > pK a ∼ 4), the polymer chains are mostly ionized. The charged repulsion along the polymer backbone prevails over the styryl–styryl hydrophobic effects, causing PSMA molecules to adapt into an extended chain. As the solution pH is lowered (pH ≤ 4), the carboxylic acid groups of PSMA are fully protonated. The loss of charged repulsion allows the hydrophobic effects to become a dominant factor. As a result, the polymer chains are collapsed progressively into a distinct microdomain and eventually adapt to an α-helix coil configuration (11,12), as illustrated in Figure 1. Here, the hydrophobic styryl groups were believed to be located along the central core axis of a PSMA coil structure, while those of the hydrophilic carboxylic acid groups were allocated around the outer structure surface facing toward water molecules. Due to the amphipathic nature of the PSMA coil, it can act as a surface-active agent to destabilize cellular membranes and then induce a release of cytoplasmic contents. The ability of PSMA to undergo a conformation transition enables its surface activity to be tunable in response to a pH change.

Formation of an extended PSMA chain upon alkaline hydrolysis of poly(styrene-alt-maleic anhydride) precursor and its conformational transition into a surface active α-helix coil.

The biggest advantage of PSMA as a membrane lysis agent is its ability to combine with the reconstituted membrane lipid and then produce membrane-like nanostructures, as presented in Figure 2 (11,12,13,14). These nanostructures, so-called astosomes, nanodiscs, SMALP, or Lipodisq, were reported to have a size diameter of 10–40 nm (11,14,15,16,17). According to the molecular models proposed by Tanaka et al. (18) and Dörr et al. (19), this membrane mimetic system is composed of reconstituted lipid bilayers surrounded by the polymeric chains of PSMA. The central lipoid zone of the nanoassemblies (pointed by the arrows in Figure 2) can facilitate the direct incorporation of the active compounds into their core structures, thereby allowing the compounds to be stabilized and resolved in their full functioning state. The concept was successfully demonstrated for the extraction of membrane proteins from a variety of bacterial and eukaryotic sources, including Staphylococcus aureus (20), Escherichia coli (14,19,21), Rhodobacter sphaeroides (22), Pichia pastoris (23), and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (24). However, there has been a limited focus on plant extraction.

Polymer–lipid nanostructures with amphipathic α-helical PSMA coil arrangement around lipid bilayer.

This study provided new insights into the use of PSMA lysis agents in plant antioxidant extraction. The method was performed in aqueous media with no toxic organic solvents. The leaves of the robusta coffee tree were selected as a model plant due to their potential sources of natural antioxidants, such as caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, p-coumaric acid, quercetin, kaempferol, catechin, and mangiferin (25,26,27). The extraction efficiency was evaluated on the basis of the total phenolic and flavonoid content, as well as the radical scavenging capacity. The results were compared with those extracted in deionized (DI) water, in both the absence and presence of the most commonly used surfactant, SDS.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Poly(styrene-alt-maleic anhydride), or PSMAnh (M n 2,000), was obtained from Cray Valley (USA). Morpholinopropane sulfonic acid, dithiothreitol, sodium nitrite (NaNO2), sodium acetate (CH3COONa), and acetic acid (CH3COOH) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. (+)-Catechin hydrate and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) were supplied by Sigma and used without purification. Aqueous solutions of sodium hydroxide (NaOH), hydrochloric acid (HCl), aluminum chloride (AlCl3), and sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) were received from QRëC Reagent Chemical. Ascorbic acid was purchased from Chem-supply. Prior to extraction, 1 g of PSMAnh was initially suspended in 100 mL of distilled water. The pH of the solution was adjusted to pH 12 by using 1 M NaOH. After 24 h, the mixture was neutralized by adding 1 M HCl, filtered-off, and dialyzed against DI water. Finally, the solution was freeze-dried in powder form.

2.2 Plant material and extraction

Leaves of a mature and healthy robusta coffee plant (Coffea robusta Pierre ex Froehner L.) were collected from Mae Fah Luang University Botanical Garden, Chiang Rai, Thailand. The leaf was washed, chopped, and ground in liquid nitrogen. The extracting medium was initially prepared by dissolving the surfactant (PSMA or SDS) in either DI water or acetate buffer. The surfactant content was adjusted to a final concentration of 1% (w/v). To prepare acetate buffers (200 mL, 20 mM), aqueous solutions of CH3COONa (0.1 M) and CH3COOH (0.1 M) were mixed. With the slight addition of HCl or NaOH, the desirable pH values were attained at 4.0, 5.6, or 7.0. To begin the extraction process, the plant tissue (2 g) was mixed with the extraction media (10 mL). The mixture was then incubated for 20 min on an orbital shaker (250 rpm) and maintained at room temperature. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm and 4°C, the supernatant was finally collected for further analysis.

2.3 Total phenolic content determination

According to the previous study (28), 100 µL of the coffee extracts by DI water extraction alone (pH 6.5–7) was mixed with 2 mL of Na2CO3 solution (2% w/v). Then, 100 µL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (50% w/v) was added and incubated for 30 min. Color development was determined at 750 nm (λ max). The total phenolic intensities were based on the gallic acid calibration curve (10–50 µg·mL−1). The results were expressed in terms of gallic acid equivalent per gram of sample (GAE·g−1). DI water without surfactant addition was used as a control sample.

2.4 Total flavonoid content determination

The AlCl3 colorimetric method was used (29). In total, 500 µL of the coffee extract derived from the DI water extraction alone (pH 6.5–7) was mixed with 200 µL of AlCl3 solution (0.55 M) and 100 µL of NaNO2 solution (3 M). Then, 500 µL of NaOH (2.5 M) and 1 mL of DI water were added. The final volume was adjusted to 2.5 mL by using DI water. The reaction mixture was incubated in darkness and at room temperature for 40 min. The UV absorbance was measured at 510 nm (λ max). The total flavonoid content was obtained by using the catechin calibration curve (5–50 µg·mL−1). The results were expressed as catechin equivalent (CE) per gram of sample (CE·g−1). DI water without surfactant addition was used as a control sample.

2.5 Evaluation of antioxidant activity

The antioxidant capacity (IC50) was estimated based on the DPPH assay. The stock solution of standard ascorbic acid (20 µg·mL−1) was prepared and further diluted to obtain final concentrations of 0.1–5.0 μg·mL−1. The crude extracts were diluted from the stock solution (4,884 µg·mL−1) by using the lysis buffer as a diluent. Each solution (100 µL) was transferred into the 96-well plates and then mixed with a 100 μL of 0.3 mM DPPH methanolic solution. The mixture was incubated in darkness and at room temperature for 30 min. Finally, the UV absorbance of the solution was measured at 517 nm (λ max). The percentage of inhibition (% inhibition) was calculated by using Eq. 1. The IC50 value was expressed based on the flavonoid content (μg CE·mL−1). The extraction medium alone was used as control samples.

2.6 Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean (± standard deviation) of at least three replicates (n = 3). Significant differences among mean values from triplicate analyses (p < 0.05) were determined by Duncan’s multiple range test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05 for all statistical tests.

3 Results and discussion

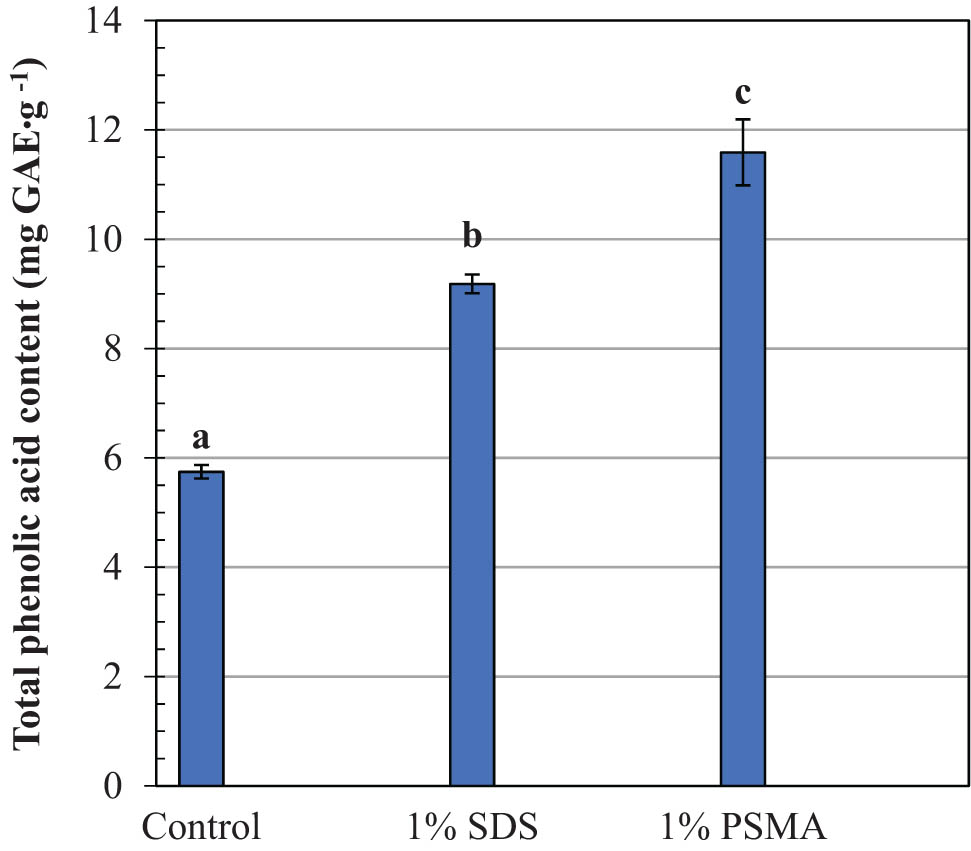

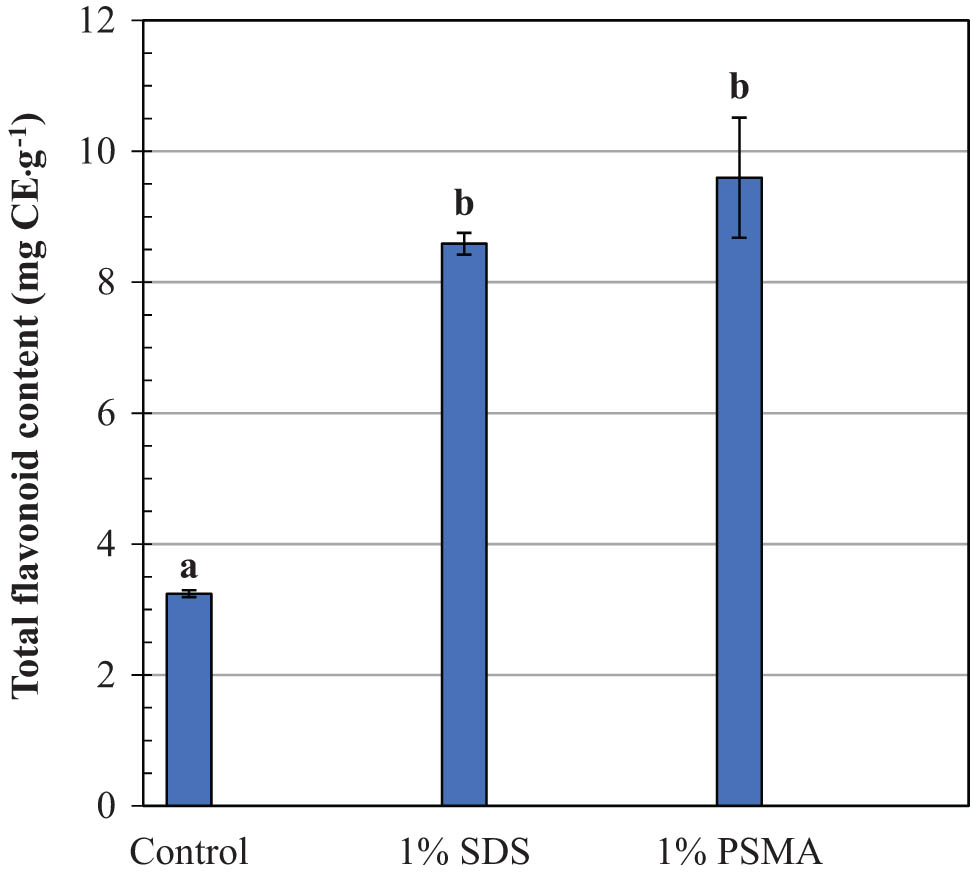

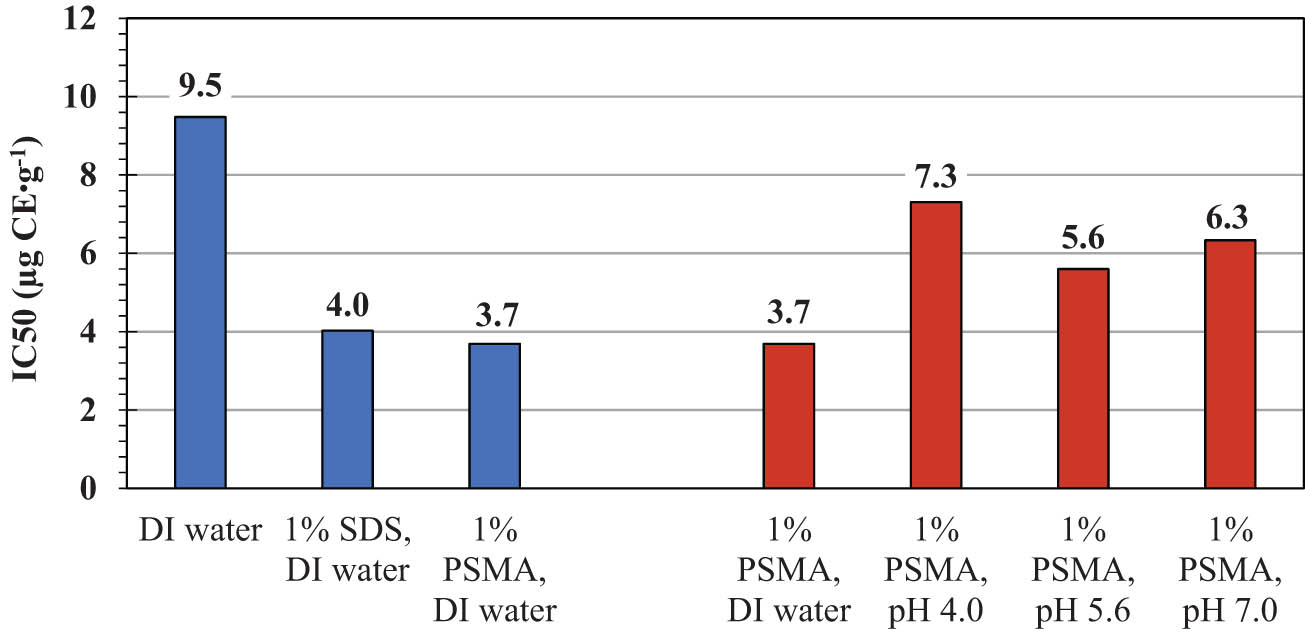

Coffee leaf extracts have been used for centuries as an alternative medicine due to their diverse pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammation, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, antioxidant, and neuroprotective properties. The crude extracts have long been used to treat various human diseases, such as gastrointestinal, diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular, and dermatological conditions (30,31). Their phytochemical and therapeutic properties are related to phenolic constituents, which vary with geographic location, seasoning, plant species, and the age of leaves. The main active compounds have been identified as mangiferin, catechins, kaempferol, rutin, caffeic acid, hydroxycinnamic acid, coumaric acid, and chlorogenic acid (31,32). Due to their structural complexity and lipophilicity nature, the recovery yields of these compounds by using water extraction alone are quite low. This is consistent with the results in Figures 3 and 4 (control media). In the absence of SDS or PSMA, the total contents of phenolic acids and flavonoids are found to be as low as 5.8 and 3.2 mg CE·g−1, respectively. On the addition of PSMA, approximately twofold and threefold increases in the recovery yields of phenolic acids and flavonoids are detected, respectively. The effects seem to be more effective than those of SDS, which is one of the most effective membrane lysis agents commonly used in both research and industrial applications. Interesting results may be obtained when comparing the DPPH antioxidant activity in all crude extracts. As noted in Figure 5 (blue bars), the crude extracts obtained by the PSMA extraction show the lowest averaged IC50 values of around 3.7 µg CE·mL−1, as compared to those by DI water extraction (9.5 µg CE·mL−1) and SDS extraction (4.0 µg CE·mL−1). The use of PSMA has thus proved its potential in recovering plant antioxidants with improved radical scavenging activity.

Comparison of the total phenolic acids in robusta coffee leave extracts obtained by different extracting systems. Mean values followed by the same letter in a bar chart plot are not significantly different at p < 0.05, according to the Duncan’s multiple range test.

Comparison of the total flavonoid contents in robusta coffee leave extracts obtained by different extracting systems. Mean values followed by the same letter in a bar chart plot are not significantly different at p < 0.05, according to the Duncan’s multiple range test.

Comparison of the DPPH scavenging assay IC50 values in the coffee leave extracts by different extracting systems.

The excellent extractability of the PSMA lysis agent may be due to the formation of PSMA/lipid assemblies, as presented in Figure 2. The central lipoid zone of these structures is non-polar in nature. This can serve as a binding domain for low-polarity antioxidants to be encapsulated, thus promoting their aqueous solubility and the extraction yields, as illustrated in Figures 3 and 4. Encapsulation within these membrane-like structures protects plant active compounds from the external environments and allows them to be resolved in their fully functional state. The formation of such a biomimetic system was experimentally proved, for the first time, by Qiu and co-workers (33). Their main focus was to extract the AcrB multidrug exporter from the Gram-negative bacterial host. By using PSMA, this compound was proved to be transferred into the central cavity of the renatured lipid bilayer. Led by the cryo-EM results, this bilayer was composed of 24 lipid molecules, occupying the areas of 264 Å2 (outer leaflet) and 400 Å2 (inner leaflet). The intimate protein–lipid interactions enable these bilayer lipids to sense any change in the AcrB trimers. If there was any conformational change, the membrane lipids would harmonize the peristaltic motion along the peptide chains, thus driving the protein to fold back to its native structure. The process was considered to serve as a protection mechanism to stabilize the AcrB native structure, thereafter preserving its biological function during the extraction process. The concept has already been applied to various transmembrane proteins from different cellular membrane sources (7,11,12,14,15,17,22,23,34). However, there has been no report on PSMA-assisted extraction of plant bioactive compounds. The current study is the first to confirm that this concept can also be applied to plant phenolics. The improved antioxidant activity by the PSMA extraction presented in Figure 5 provides good supporting evidence on this matter.

An important question is whether these stabilization effects exist in the case of SDS lysis agents. The answer to this question is related to the membrane solubilization mechanism by SDS detergent. At room temperature, membrane solubilization by SDS is likely to proceed via the micelle extraction mechanism, while that by PSMA occurs through the transbilayer flip–flop mechanism (8,35). The difference is mainly because of the slower kinetics of flip–flop motion across the membrane bilayer of the former. In the beginning, the micelles of SDS are adsorbed onto the outer monolayer of the membrane bilayer. The nearly lipid molecules are detached (pinched off) and then associated with SDS micelles, producing the mixed SDS–lipid micelles at the end. Due to the favorable electrostatic attraction between the lipid and SDS headgroups (36), the biological functions of phospholipids are expected to be altered. As such, the aforementioned stabilization effects would become less effective. Consequently, direct exposure to the external environment would cause permanent damage to the encapsulated compounds, thus causing them to lose their bioactivities, as observed in Figure 5 (blue bars).

The extraction performance of PSMA to maintain plant antioxidants is considered to be affected by the salt species in the buffer systems (e.g., acetic acid, sodium, and acetate ions). This is convinced by the change in the IC50 value from 3.7 µg CE·mL−1 (DI water) to around 7.3 µg CE·mL−1 (pH 4 buffer), 5.6 µg CE·mL−1 (pH 5.6 buffer), and 6.3 µg CE·mL−1 (pH 7 buffer). Due to the lack of hydrolysable functional groups along the polymer backbone, decomposition of PSMA is unlikely to occur during mild experimental DPPH testing (e.g., room temperature). Even at pH 4, this copolymer still showed excellent surface activity (34,37,38). To clarify the extent of PSMA degradation upon acidification (pH 4), we performed additional dynamic light scattering (DLS) experiments for PSMA itself and its complexation with the synthetic phospholipid (1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-phosphatidylcholine or DMPC). Under these experimental conditions, PSMA molecules display the ability to self-assemble into very fine and stable nanoparticles. These particles have an average size diameter of only around 18 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.98 (data not shown). As previously mentioned, the particle formation is primarily driven by a conformational transition of PSMA from an extended chain to a compact coil. At pH 4, complexation with DMPC produces the end-state particles with a slightly increased size diameter of around 33 nm (data not shown). A unimodal size distribution (PDI = 0.22) suggests that the formation of these PSMA/DMPC nanoparticles is quite uniform with a low possibility of fusion or degradation. The effect of pH neutralization has already been demonstrated on a similar PSMA/lipid system (39). As the pH was increased from 4 to 7, the nanoparticles of PSMA and dilauroyl phosphorylcholine (DLPC) displayed an increased particle size, changing from 16 nm (PDI = 0.32) to 53 nm (PDI = 0.25). The narrower size distribution and the absence of a new size population suggested little sign of vesicular fusion or degradation. Led by these DLS results, the reduced antioxidant profile in the buffered systems compared to the DI water (Figure 5) is perhaps due to the greater molecular changes of the plant antioxidants inside the loosely packed nanoassemblies. Some buffer species may have competitively interacted with PSMA and/or the reconstituted lipids, creating void defects in the PSMA/lipid assemblies (Figure 2). In the presence of these defects, the encapsulated antioxidants would have been exposed to the surrounding environment (e.g., UV light, oxygen gas, chemicals). As such, they would have a higher risk of molecular decomposition and/or structural conversion into inactive forms. To avoid this, PSMA extraction should be performed in a buffer-free medium, such as DI water. Among the three acetate buffers, the crude extracts from the pH 4 system exhibit the weakest radical scavenging ability, as demonstrated by the highest IC50 value of around 7.3 µg CE·mL−1 (Figure 5). In the pH 4 solution (pH = pK a), the molecules of PSMA are fully protonated, driving the polymer chains to adopt into a helical coil (Figure 1). In the absence of charged repulsion, a hydrophobically driven association with DMPC is supposed to be highly effective. As such, encapsulation of water-insoluble compounds into the deeper core region of the mixed assemblies can become most favorable. Chemical reactions with the DPPH reagent would thereafter be shielded to the greatest extent, resulting in the weakest inhibitory effect and so the highest IC50 value, as demonstrated in Figure 5 (pH 4). The balanced shielding effects are therefore a crucial element to the successful design of these lipid analogues in practice.

4 Conclusion

The underexploited application of PSMA lysis agent for the recovery of coffee antioxidants directly into an aqueous formulation was demonstrated. In the absence of the charge shielding effects (e.g., buffer-free water), the crude extracts displayed the highest total contents of phenolic acids (11.6 mg GAE·g−1) and flavonoids (9.6 mg CE·g−1), compared to those obtained by traditional SDS and water extraction techniques. The PSMA-derived samples also showed enhanced DPPH antioxidant activity (IC50 = 3.7 µg·mL−1). The improved extractability was believed to be due to the formation of the membrane-like reservoirs that could facilitate a protective mechanism for those phytochemical antioxidants to be stabilized within the inner core structures, thus avoiding undesirable chemical reactions and the loss of their biological functions. The proposed biomimetic approach has shown the great potential to recover plant antioxidants for the benefits of human health, pharmaceutics, and biomedical uses in the future.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Dr. Pattana Kakumyan and Dr. Natsaran Saichana, School of Science, Mae Fah Luang University, as well as Dr. Robert Molloy, Chiang Mai University, for their insightful suggestions.

-

Funding information: This work was financially supported by the National Research Council of Thailand and Mae Fah Luang University (No. 622B01065).

-

Author contributions: Patchara Punyamoonwongsa: Conceptual design, selection of the experimental protocols, in charged of overall data analysis and interpretation, took the lead in writing the manuscript with intellectual contents, reshaped and final approval of the version to be published.

-

Conflict of interest: The author states no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The author confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

(1) Kasote DM, Katyare SS, Hegde MV, Bae H. Significance of antioxidant potential of plants and its relevance to therapeutic applications. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11(8):982–91. 10.7150/ijbs.12096.Search in Google Scholar

(2) Adebooye OC, Alashi AM, Aluko RE. A brief review on emerging trends in global polyphenol research. J Food Biochem. 2018;42(4):e12519. 10.1111/jfbc.12519.Search in Google Scholar

(3) Sy Mohamad SF, Mohd Said F, Abdul Munaim MS, Mohamad S, Azizi Wan Sulaiman WM. Application of experimental designs and response surface methods in screening and optimization of reverse micellar extraction. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2020;40(3):341–56. 10.1080/07388551.2020.1712321.Search in Google Scholar

(4) Miłek M, Legáth J. Extraction of flavonoids from medicinal plants with use of various solvents systems. Proceedings of the Scientific Researches in Food Production-3rd Meeting of Young Researchers from V4 Countries. Debrecen, Hungary: 2018 Dec 7.Search in Google Scholar

(5) Chemat F, Abert Vian M, Ravi HK, Khadhraoui B, Hilali S, Perino S, et al. Review of alternative solvents for green extraction of food and natural products: Panorama, principles, applications and prospects. Molecules. 2019;24(16):3007.10.3390/molecules24163007Search in Google Scholar

(6) Zhou X, Dong L, Li D. A comprehensive study of extraction of hyperoside from Hypericum perforatum L. using CTAB reverse micelles. J Chem Technol Biotechnol Int Res Process Environ Clean Technol. 2008;83(10):1413–21.10.1002/jctb.1963Search in Google Scholar

(7) Kalipatnapu S, Chattopadhyay A. Membrane protein solubilization: recent advances and challenges in solubilization of serotonin1A receptors. IUBMB life. 2005;57(7):505–12. 10.1080/15216540500167237.Search in Google Scholar

(8) Lichtenberg D, Ahyayauch H, Goñi FM. The mechanism of detergent solubilization of lipid bilayers. Biophys J. 2013;105(2):289–99.10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.007Search in Google Scholar

(9) Peng L-Q, Cao J, Du L-J, Zhang Q-D, Xu J-J, Chen Y-B, et al. Rapid ultrasonic and microwave-assisted micellar extraction of zingiberone, shogaol and gingerols from gingers using biosurfactants. J Chromatogr A. 2017;1515:37–44. 10.1016/j.chroma.2017.07.092.Search in Google Scholar

(10) Nkhili E, Tomao V, Hajji HE, Boustani E-SE, Chemat F, Dangles O. Microwave‐assisted water extraction of green tea polyphenols. Phytochem Anal. 2009;20(5):408–15. 10.1002/pca.1141.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Knowles TJ, Finka R, Smith C, Lin Y-P, Dafforn T, Overduin M. Membrane proteins solubilized intact in lipid containing nanoparticles bounded by styrene maleic acid copolymer. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(22):7484–5.10.1021/ja810046qSearch in Google Scholar

(12) Tonge SR, Tighe BJ. Responsive hydrophobically associating polymers: a review of structure and properties. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2001;53(1):109–22. 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00223-x.Search in Google Scholar

(13) Fiori MC, Zheng W, Kamilar E, Simiyu G, Altenberg GA, Liang H. Extraction and reconstitution of membrane proteins into lipid nanodiscs encased by zwitterionic styrene-maleic amide copolymers. Sci Rep. 2020;10(9940):9940. 10.1038/s41598-020-66852-7.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(14) Postis V, Rawson S, Mitchell JK, Lee SC, Parslow RA, Dafforn TR, et al. The use of SMALPs as a novel membrane protein scaffold for structure study by negative stain electron microscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) – Biomembranes. 2015;1848(2):496–501. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.10.018.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(15) Chen A, Majdinasab EJ, Fiori MC, Liang H, Altenberg GA. Polymer-encased nanodiscs and polymer nanodiscs: New platforms for membrane protein research and applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:598450. 10.3389/bbioe.2020.598450.Search in Google Scholar

(16) Punyamoonwongsa P, Tighe BJ. A smart hydrogel-based system for controlled drug release. Chiang Mai J Sci. 2005;32(3):471–8.Search in Google Scholar

(17) Ravula T, Ramadugu S, Mauro GD, Ramamoorthy A. Bioinspired, size-tunable self-assembly of polymer-lipid bilayer nanodiscs. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56(38):11466–70. 10.1002/ange.201705569.Search in Google Scholar

(18) Tanaka M, Hosotani A, Tachibana Y, Nakano M, Iwasaki K, Kawakami T, et al. Preparation and characterization of reconstituted lipid–synthetic polymer discoidal particles. Langmuir. 2015;31(46):12719–26.10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b03438Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(19) Dörr JM, Koorengevel MC, Schäfer M, Prokofyev AV, Scheidelaar S, Van Der Cruijsen, et al. Detergent-free isolation of KcsA in nanodiscs. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(52):18607–12. 10.1073/pnas.1416205112.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(20) Paulin S, Jamshad M, Dafforn TR, Garcia-Lara J, Foster SJ, Galley NF, et al. Surfactant-free purification of membrane protein complexes from bacteria: application to the staphylococcal penicillin-binding protein complex PBP2/PBP2a. Nanotechnology. 2014;25:258101. 10.1088/0957-4484/25/28/285101.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(21) Walker P, Crane E. Constituents of propolis. Apidologie. 1987;18(4):327–34.10.1051/apido:19870404Search in Google Scholar

(22) Swainsbury DJK, Scheidelaar S, Foster N, Grondelle R, Killian JA, Jones MR. The effectiveness of styrene-maleic acid (SMA) copolymers for solubilisation of integral membrane proteins from SMA-accessible and SMA-resistant membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes. 2017;1859(10):2133–43. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.07.011.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(23) Logez C, Damian M, Legros C, Dupré C, Guéry M, Mary S, et al. Detergent-free isolation of functional G protein-coupled receptors into nanometric lipid particles. Biochemistry. 2016;55(1):38–48. 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01040.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(24) Smirnova IA, Sjöstrand D, Li F, Björck M, Schäfer J, Östbye H, et al. Isolation of yeast complex IV in native lipid nanodiscs. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) – Biomembranes. 2016;1858(12):2984–92. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.09.004.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(25) Chen X-M, Ma Z, Kitts DD. Effects of processing method and age of leaves on phytochemical profiles and bioactivity of coffee leaves. Food Chem. 2018;249:143–53. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.12.073.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(26) Rodríguez-Gómez R, Vanheuverzwjin J, Souard F, Delporte C, Stevigny C, Stoffelen P, et al. Determination of three main chlorogenic acids in water extracts of coffee leaves by liquid chromatography coupled to an electrochemical detector. Antioxidants. 2018;7(10):143. 10.3390/antiox7100143.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(27) Kurang RY, Kamengon RY. Phytochemical and antioxidant activities of Robusta coffee leaves extracts from Alor Island, East Nusa Tenggara. AIP Conf Proc. 2021;2349(1):020028. 10.1063/5.0051835.Search in Google Scholar

(28) Katsube T, Tabata H, Ohta Y, Yamasaki Y, Anuurad E, Shiwaku K, et al. Screening for antioxidant activity in edible plant products: comparison of low-density lipoprotein oxidation assay, DPPH radical scavenging assay, and Folin−Ciocalteu assay. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52(8):2391–6. 10.1021/jf035372g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(29) Lin W-Y, Yang MJ, Hung L-T, Lin L-C. Antioxidant properties of methanol extract of a new commercial gelatinous mushrooms (white variety of Auricularia fuscosuccinea) of Taiwan. Afr J Biotechnol. 2013;12(43):6210–21. 10.5897/AJB12.1520.Search in Google Scholar

(30) Acidri R, Sawai Y, Sugimoto Y, Handa T, Sasagawa D, Masunaga T, et al. Phytochemical profile and antioxidant capacity of coffee plant organs compared to green and roasted coffee beans. Antioxidants. 2020;9(2):93. 10.3390/antiox9020093.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(31) Rosales-Villarreal MC, Rocha-Guzmán NE, Gallegos-Infante JA, Moreno-Jiménez MR, Reynoso-Camacho R, Pérez-Ramírez IF, et al. Significance of bioactive compounds, therapeutic and agronomic potential of non-commercial parts of the Coffea tree. Biotecnia. 2019;21(3):143–53. 10.18633/biotecnia.v21i3.1046.Search in Google Scholar

(32) Patay ÉB, Bencsik T, Papp N. Phytochemical overview and medicinal importance of Coffea species from the past until now. Asian Pac J Tropical Med. 2016;9(12):1127–35. 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.11.008.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(33) Qiu W, Fu Z, Xu GG, Grassucci RA, Zhang Y, Frank J, et al. Structure and activity of lipid bilayer within a membrane-protein transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(51):12985–90.10.1073/pnas.1812526115Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(34) Saez-Martinez V, Punyamoonwongsa P, Tighe BJ. Polymer–lipid interactions: Biomimetic self-assembly behaviour and surface properties of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) with diacylphosphatidylcholines. Reactive Funct Polym. 2015;94:9–16.10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2015.06.015Search in Google Scholar

(35) Keller S, Heerklotz H, Jahnke N, Blume A. Thermodynamics of lipid membrane solubilization by sodium dodecyl sulfate. Biophys J. 2006;90(12):4509–21.10.1529/biophysj.105.077867Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(36) Sikorska E, Wyrzykowski D, Szutkowski K, Greber K, Lubecka EA, Zhukov I. Thermodynamics, size, and dynamics of zwitterionic dodecylphosphocholine and anionic sodium dodecyl sulfate mixed micelles. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;123(1):511–23.10.1007/s10973-015-4918-0Search in Google Scholar

(37) Scheidelaar S, Koorengevel MC, van Walree CA, Dominguez JJ, Dörr JM, Killian JA. Effect of polymer composition and pH on membrane solubilization by styrene-maleic acid copolymers. Biophys J. 2016;111(9):1974–86.10.1016/j.bpj.2016.09.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(38) Punyamoonwongsa P. Synthetic analogues of protein-lipid complexes. Birmingham, UK: Aston University; 2007.Search in Google Scholar

(39) Patchara P, Brian TJ. Association behavior of the synthetic protein-lipid complex analogues. Adv Mater Res. 2012;506:134–7. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.506.134.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Patchara Punyamoonwongsa, published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes