Abstract

The synthesis of tetrazole-containing derivatives of chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan was carried out by a sequence of reactions including cyanoethylation of polysaccharides and subsequent azidation of cyanoethyl derivatives. The reaction of cyanoethylation of polysaccharides with acrylonitrile proceeds in the temperature range 40–60°C in the presence of NaOH. The transformation of nitrile groups into tetrazole rings (azidation) of cyanoethylated polysaccharide derivatives was carried out with a mixture of sodium azide with ammonium chloride in DMF at 105°C. The reaction with the participation of derivatives of starch and arabinogalactan is characterized by the degree of conversion of nitrile groups into tetrazole rings, which is close to the maximum. The introduction of unsubstituted tetrazole rings into the structure of polysaccharides of acidic N–H substantially changes some of their properties. Like other carbo- and hetero-chain polymers containing N–H unsubstituted tetrazole rings in the structure, tetrazolated polysaccharides exhibit the properties of acidic polyelectrolytes. Tetrazole-containing derivatives of chitosan exhibit the properties of polyampholytes. The presence of tetrazole rings in the structure of modified polysaccharides allows the reaction with epoxy compounds to yield network polymers capable of limited swelling in aqueous media with the formation of polyelectrolyte hydrogels.

1 Introduction

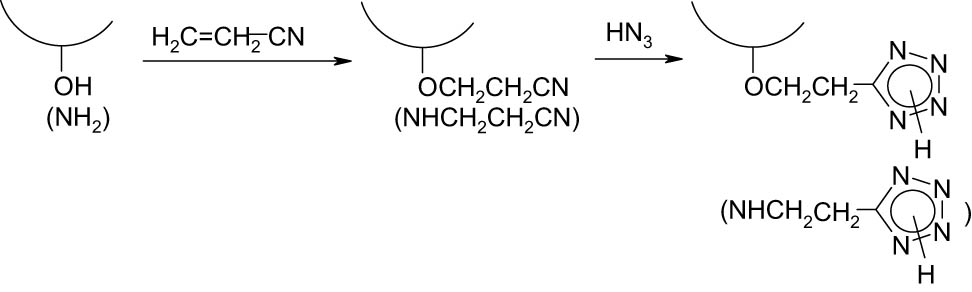

Natural polymers, polysaccharides, are unique building blocks for the design of various polymeric materials (1,2,3). This is due to the combination of three essential features that distinguish polysaccharides from other natural and synthetic polymers. First, such polysaccharides as cellulose, starch, arabinogalactan, and chitosan (deacetylated chitin) are extracted from renewable, almost inexhaustible natural raw materials. Second, polysaccharides possess a plethora of practically valuable properties: nontoxicity, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and chemical and physiological activities (4,5,6,7,8). Third, polysaccharides bearing the hydroxyl and amino functions (e.g., chitosan) are chemically reactive compounds that provide great opportunities for their chemical modification to afford new functional polymeric materials (9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19). Among the most promising directions in the modification of polysaccharides is the introduction of poly-nitrogen heterocyclic fragments (20,21,22), in particular, tetrazole rings (23,24,25,26,27) as pendent substituents into their polymeric structure. This is not surprising since tetrazole and its derivatives are known to possess extremely interesting properties. The tetrazole ring, having 80% mass content of nitrogen, is characterized by a high positive enthalpy of formation (236 kJ·mol−1 (28,29)), i.e., it is an explosophoric fragment, which can significantly enhance the energy characteristics of high-molecular compounds, including cellulose-based polymers (24,30,31,32). Such polymeric compounds are ranked as very promising energy-rich ingredients for highly efficient solid rocket fuels and explosive and gas-generating compositions. Featuring a wide array of physiological activity, tetrazole derivatives are also employed for the design of drugs with diverse therapeutic effects (33,34,35). In this regard, the synthesis of polymers combining the properties of polysaccharides and tetrazole fragments represents a challenge for the development of so-called “smart” drugs of the controlled and targeted action (26,36,37). In addition, polymeric compounds, including those derived from polysaccharides containing N–H unsubstituted tetrazole cycles, exhibit the properties of polyelectrolytes, have a complexing ability with respect to inorganic and organic objects, and high reactivity (27,38,39,40) that supports the prospects for further modification of tetrazole-containing polysaccharides. However, the reactions involving the introduction of a tetrazole ring into the structure of a polysaccharide macromolecule are mainly limited to the modification of cellulose and chitosan (or chitin). For instance, tetrazole cellulose was synthesized by the reaction of cellulose hydroxyl groups with various carboxyl-containing tetrazole derivatives affording an ester spacer between the main macromolecular chain and the tetrazole ring (21,24,31,32). Also, tetrazole derivatives of chitosan were obtained via the reaction between tetrazole and chitosan derivatives containing “anchor” functional groups, capable of interacting with each (25,41). A general approach to the introduction of a tetrazole ring into the macromolecule of cellulose and chitosan (chitin) includes a sequence of transformations (Scheme 1). First, the nucleophilic addition of hydroxyl or amino groups (in the case of chitosan) of the polysaccharide to acrylonitrile (or cyanoethylation of cellulose and chitosan) (1) occurs followed by the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of azide ions to the nitrile group (transformation of nitrile fragments into tetrazole rings) (2) (26,36,37,39,42). This approach is assumed to be general for the synthesis of tetrazole-containing derivatives of any polysaccharides. Moreover, in this case, the pendent heterocyclic substituent represents an N–H unsubstituted tetrazole cycle, which is very intriguing in terms of imparting new properties (acidic, polyelectrolyte, complexing, physiological, reactive) to polysaccharides.

Reaction scheme of polysaccharide modification.

In the present article, a sequential modification of three polysaccharides (chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan) involving their cyanoethylation and subsequent azidation has been studied. Also, some properties of the synthesized tetrazole derivatives of polysaccharides are analyzed.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Commercial chitosan (Aldrich), with a deacetylation degree of 63% and molecular weight of 200 kDa, starch (120 kDa) and arabinogalactan (42 kDa) (manufactured in Russia), acrylonitrile and sodium azide (Merck), as well as epoxy resin based on polyethylene glycol (ERPEG) (495 Da) were used in the work. The solvents were dried and purified according to the standard procedures.

2.2 Synthesis of the cyanoethyl derivatives of polysaccharides

Arabinogalactan (15 g) was dissolved in water (30 mL) and mixed with excess acrylonitrile (180 g). While stirring on a magnetic stirrer, the mixture was an emulsion, to which NaOH (0.5 g) was added as a concentrated aqueous solution. The temperature was raised to 40°C or 60°C. After about 30 min, the system became homogeneous. The reaction mixture was kept under constant stirring for 4 h. After the completion of the reaction, the cyanoethylation product was precipitated into a 0.1 M HCl solution, washed several times with distilled water until neutral, and dried in a vacuum to a constant weight. The yield of (cyanoethyl)arabinogalactan (CNAG) was 12 g. (Cyanoethyl)starch (CNS) was synthesized in a similar way.

(Cyanoethyl)chitosan (CNC) was synthesized by a slightly modified procedure. First, chitosan (12 g) was dissolved in a mixture of concentrated HCl (13 g) and water (450 g). Then, NaOH (7 g) was added to the solution, and a loose precipitate of chitosan was filtered off and squeezed out in a centrifuge to remove excess water. The crude chitosan thus prepared was mixed with acrylonitrile (120 g). NaOH (0.5 g) was added to the resulting suspension as a concentrated aqueous solution. The reaction mixture was kept under constant stirring at 60°C for 4 h. The cyanoethylation product was precipitated into acidified water and repeatedly washed with water, squeezed out on a porous filter, and dried in a vacuum to a constant weight. The CNC yield was 9.5 g.

2.3 Synthesis of the tetrazole derivatives of polysaccharides

A mixture of sodium azide (2 g) with ammonium chloride (1.6 g) in DMF (10 mL) was heated upon stirring at 60°C for 1 h and then cooled to room temperature. To the resulting suspension, a solution of CNAG (3 g) in DMF (15 mL) was added, and the temperature of the mixture was slowly raised to 105°C within 1 h. At this temperature, the reaction mixture was kept under constant stirring for 15 h, then cooled and poured into acidified water. The precipitated [(tetrazole-5-yl)ethyl]arabinogalactan (TEAG) was washed with distilled water until neutral reaction of the wash water, separated and dried in vacuum to constant weight. [(Tetrazole-5-yl)ethyl]starch (TES) and [(tetrazole-5-yl)ethyl]chitosan (TEC) were synthesized in a similar way.

2.4 Synthesis of the cross-linked tetrazole derivatives of polysaccharides

The cross-linked tetrazole derivatives of polysaccharides TES and TEC were synthesized by the reaction with ERPEG in DMF at a concentration of tetrazole-containing polymer of 10 g·dL−1, the molar ratio of TES(TEC)/ERPEG of 3:1 and a temperature of 80°C. To carry out the process at room temperature, pre-prepared DMF solutions of TES or TEC with ERPEG were mixed. Then, the reaction mixture was loaded into ampoules, blown with argon, sealed, and kept in a thermostat at the above temperature. The reaction was accompanied by gelation; the time of flowing loss by the system was recorded visually. The complete cross-linking of tetrazolized polysaccharides was achieved in 7 days. The resulting gelatinous mass was kept for three weeks under distilled water, which was periodically replaced, to remove DMF. Thus, hydrogels of cross-linked tetrazolized TES and TEC containing nonionized tetrazole fragments were obtained.

2.5 Characterization

The structure of the modified polymers and the degrees of cyanoethylation and azidation were determined via elemental analysis, FT-IR, 13C and 1H NMR spectroscopy, and potentiometric titration of polymers. Elemental analysis was conducted on a FLASH BA 1112 Series CHN analyzer. 13C and 1H NMR spectra were registered on a VarianVXR-500 spectrometer (500 MHz) in deuterated DMSO d 6 solutions. The FT-IR spectra of modified polysaccharides were run on an FT-IR Fourier spectrometer “Infralum FT-801” at room temperature using KBr pellets. The residual content of N–H unsubstituted tetrazole moieties in TEC, TES, and TEAG was estimated by potentiometric measurements conducted using an EV-74 ionometer. The thermal analysis of the tetrazole derivatives of polysaccharides was conducted on a NETZSCH STA 449 F3 Jupiter thermogravimetric analyzer in the dynamic regime; the rate of heating in air was 5 deg·min−1. The phase diagrams of tetrazole-containing polymer–water systems were measured by the equilibrium swelling of polymer samples in water vapor at the predetermined temperature. The viscosities of polymer solutions were determined with the use of an Ubbelohde viscometer at 25°C. The pH of the medium was varied by adding hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide to the system.

3 Results and discussion

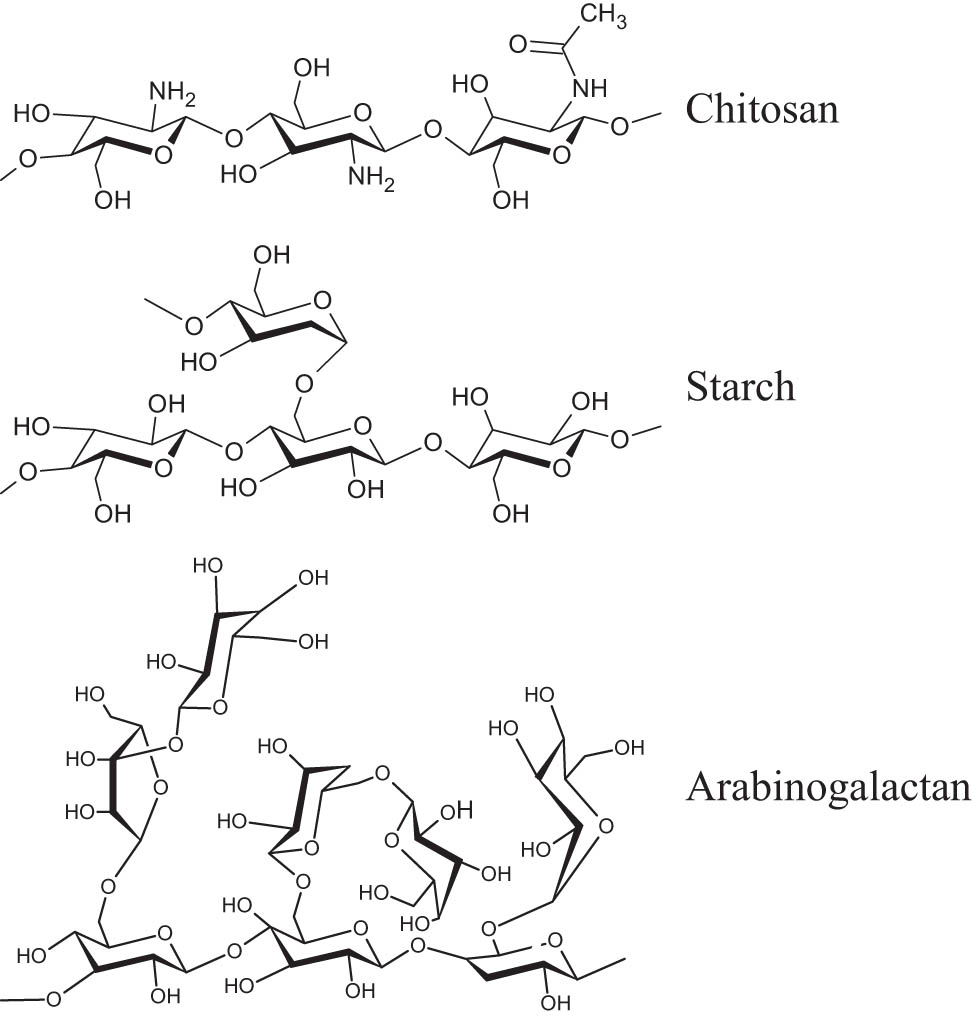

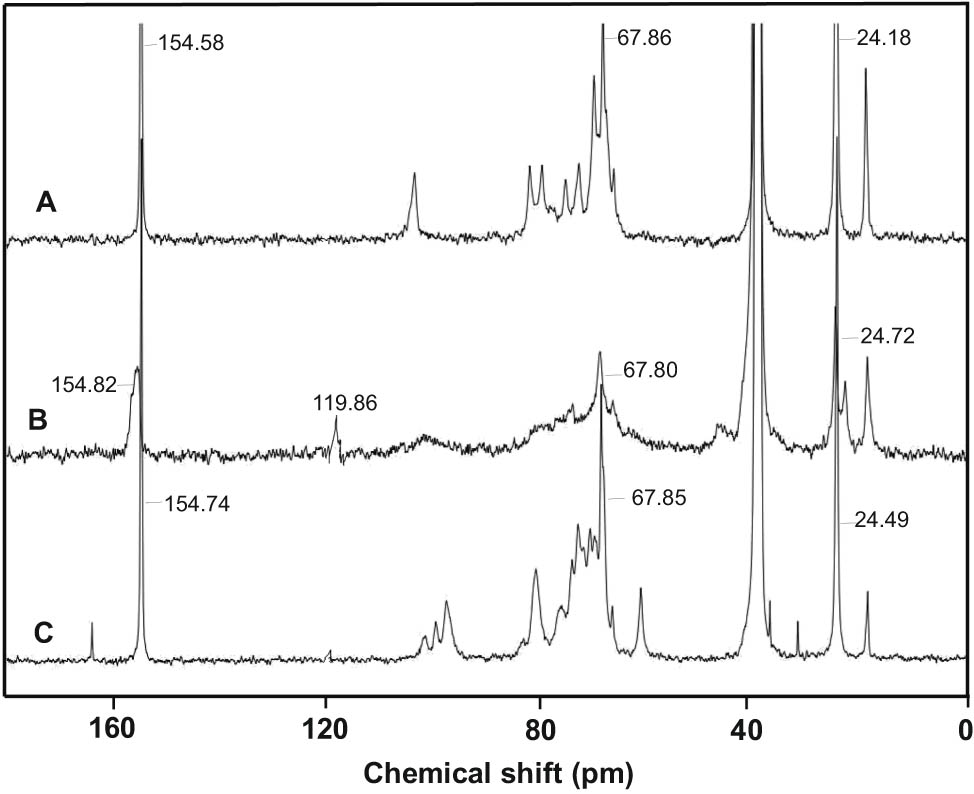

The macromolecules of chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan polysaccharides, used in this work, contain the same pyranose structural fragments, but differ in functionality and branching (Scheme 2). In each pyranose cycle, a linear chitosan macromolecule bears, along with hydroxyl groups, the amino or residual acylamino functions, which does not participate in the studied modification reactions. Starch and arabinogalactan have only one type of reactive functional group (hydroxyl). However, the macromolecules of these polysaccharides have a branched structure. Therefore, in the case of these polysaccharides, the tetrazole rings can be introduced both into the main and side polymer chains. It should be noted that here we aimed to reach the maximum conversion of functional groups at both stages (cyanoethylation and azidation) of polysaccharide modification.

Illustration of the structures of arabinogalactan, starch, and chitosan.

The cyanoethyl derivatives of chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan were synthesized by reacting acrylonitrile in the presence of sodium hydroxide (Scheme 3). In the absence of the alkali, the addition of acrylonitrile took place only in the case of chitosan and only to the amino group (a stronger nucleophile than the hydroxyl moiety). Varying the polysaccharides' cyanoethylation conditions (Table 1) showed that the increased concentration of NaOH and higher temperature of the reaction medium augmented the degree of substitution (DSCN) of the hydroxyl groups of the polymer substrate (the maximum DSCN was approximately 3). However, in the case of chitosan, even with the highest amount of sodium hydroxide and highest temperature, the degree of functional groups’ conversion in the polymer chain was significantly lower as compared to starch or arabinogalactan. Further increase of the above parameters turned out to be inappropriate due to the resinification processes and worse quality of the target modification products. For the most branched arabinogalactan, DSCN values (>2) indicated that the side branch pyranose cycles were also modified.

Synthesis scheme of TEC, TES, and TEAG.

Conditions and results of the cyanoethylation reaction of polysaccharides

| Polysaccharidea | NaOH (mol × 102) | T (°C) | Nitrogen content in the polymer (%) | DSCN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabinogalactan | 0.38 | 40 | 10.2 | 2.1 |

| Arabinogalactan | 0.50 | 40 | 10.5 | 2.2 |

| Arabinogalactan | 1.25 | 40 | 10.8 | 2.3 |

| Arabinogalactan | 2.50 | 40 | 11.0 | 2.4 |

| Arabinogalactan | 0.63 | 60 | 11.6 | 2.5 |

| Arabinogalactan | 1.25 | 60 | 12.3 | 2.6 |

| Starch | 0.75 | 40 | 9.7 | 2.0 |

| Starch | 2.75 | 40 | 11.6 | 2.5 |

| Starch | 1.18 | 60 | 10.5 | 2.2 |

| Chitosan | 0 | 40 | 10.0 | 0.5b |

| Chitosan | 1.25 | 60 | 14.0 | 1.6b |

| Chitosan | 2.50 | 60 | 14.8 | 1.7b |

| Chitosan | 3.75 | 60 | 14.9 | 1.8b |

| Chitosan | 6.25 | 60 | 15.0 | 1.9b |

- a

The amount of arabinogalactan and starch taken into the reaction was 0.093, and chitosan was 0.068 mol.

- b

Calculated taking into account the degree of deacetylation in the original chitosan.

The formation of cyanoethylation products (CNAG, CNS, and CNC) of polysaccharides was confirmed by the data elemental analysis (nitrogen content), IR, and NMR spectroscopy. The 13C NMR spectra of all the samples show signals of the methylene group carbons of the side substituent (δ 21.5–21.9 and 62.9–63.7 ppm), fragments of the polysaccharide polymer chain (δ 18.1–21.7, 57.2–61.3, and 68.1–70.7 ppm), and nitrile groups (δ 119.6 ppm). The 1H NMR spectra contain signals of the methylene group protons of the side substituent (δ 4.10–4.21 and 4.92–5.27 ppm) and broadened signals of the carbohydrate chain protons (δ 1.84–2.33 and 2.42–3.15 ppm). The presence of a nitrile group in the structures of CNAG, CNS, and CNC is confirmed by an absorption band at 2,250–2,253 cm−1 in the IR spectra of the samples.

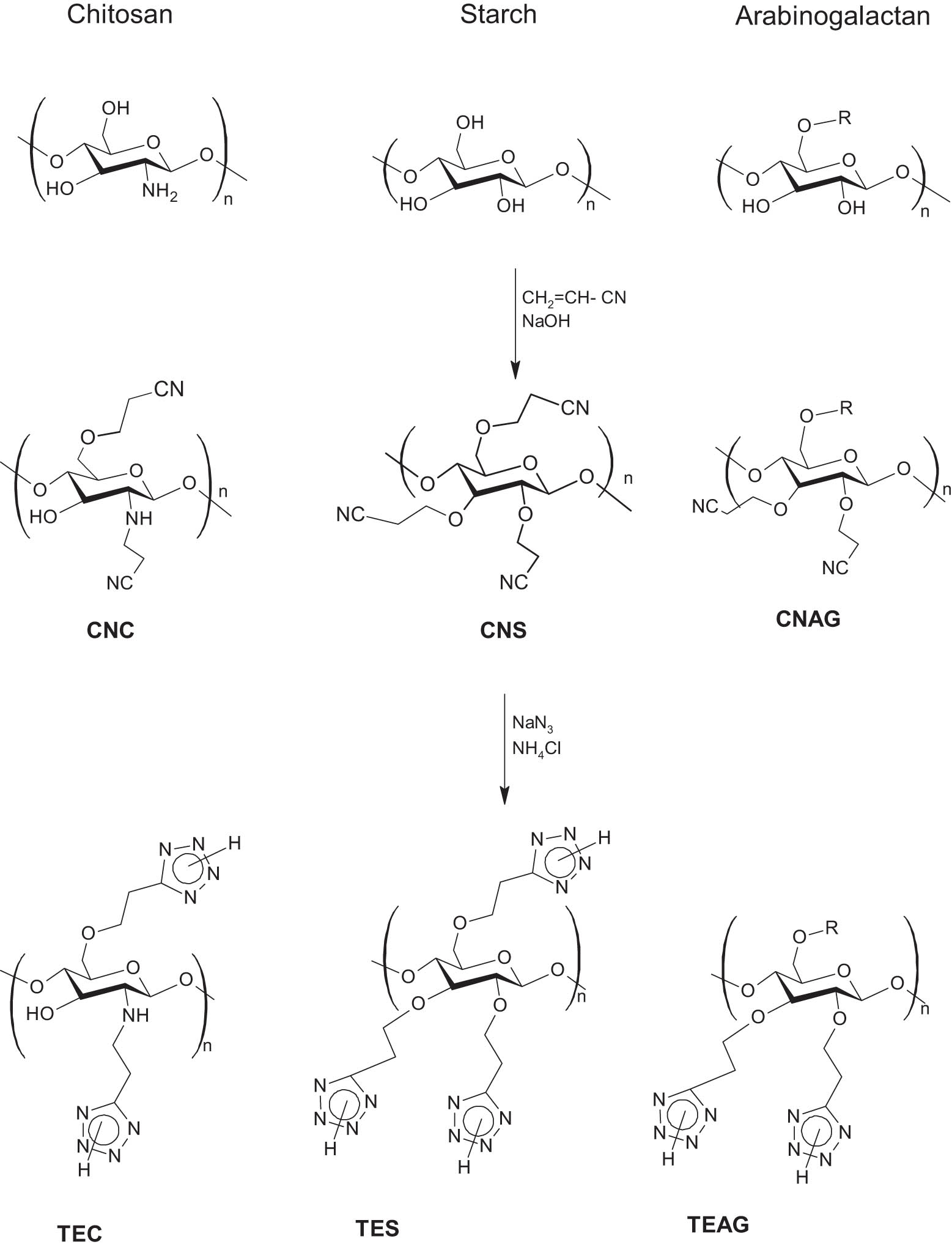

The modified chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan containing N–H unsubstituted tetrazole rings as side substituents were synthesized by 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of azide anions to nitrile groups of cyanoethyl polysaccharide derivatives (Scheme 3). In the azidation of CNAG, CNS and CNC, the samples with the maximum cyanoethylation degree of the starting polysaccharides were employed. The azidation was carried out according to the previously reported procedure for the synthesis of tetrazolated cellulose using the azidating system NaN3–NH4Cl (39). Like in the case of cellulose, the selected conditions for the transformation of nitrile groups into tetrazole rings in cyanoethyl derivatives of starch and arabinogalactan were characterized by close to maximum DST values (Table 2). For a chitosan derivative, this value was lower by 15–20%. The reaction course was monitored by NMR spectroscopy. Thus, after cycloaddition of the azide ion to the nitrile group, in the 13C NMR spectra, a decrease in the signal intensity of the nitrile group carbon was observed at 119.6 ppm, and the appearance and increase in the signal intensity of the tetrazole ring carbon were detected at 154.6 ppm. It was found that the maximum conversion of the nitrile groups into tetrazole rings for cyanoethyl derivatives of chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan was achieved in 15 h. At a longer reaction time, the conversion of CN groups was not significantly increased.

Results of azidation of cyanoethyl derivatives of polysaccharides

| Cyanoethyl derivative | Nitrogen content in the polymer (%) | DST (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Found | Calculateda | Elemental analysis | Potentiometry | |

| CNS (DSCN 2.5) | 32.5 | 34.6 | 88 | 91 |

| CNAG (DSCN 2.6) | 34.0 | 35.8 | 90 | 94 |

| CNC (DSCN 1.9) | 28.4 | 32.7 | 74 | 76 |

- a

Nitrogen content at 100% conversion of nitrile groups to tetrazole rings.

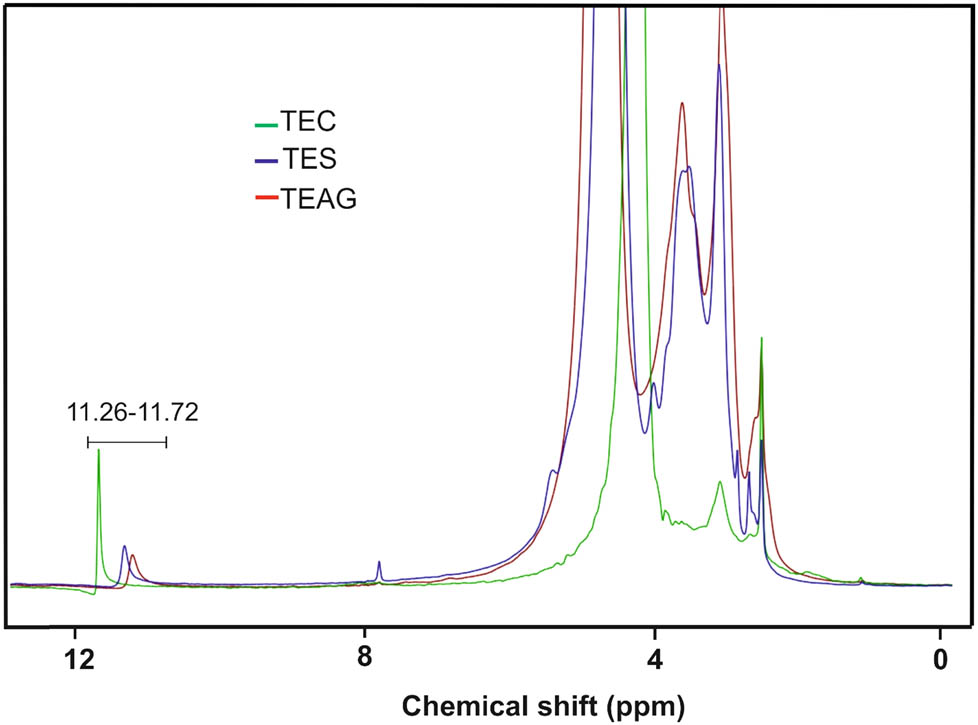

In the 13C NMR spectra of tetrazole-containing polysaccharides (TEC, TES, and TEAG) (Figure 1), along with the signal of the tetrazole ring carbon (δ 154.6–154.8 ppm), signals of methylene group carbons of the side substituent (δ 24.2–24.7 and 67.8–68.7 ppm) and fragments of the polysaccharide polymer chain (δ 18.6–22.2, 60.5–81.4, and 99.8–103.3 ppm) are present. In the spectrum of TEC, which is characterized by a lower degree of nitrile group azidation, signals of the carbon assigned to the residual CN groups (δ 119.6 ppm) are retained. The 1H NMR spectra of tetrazolized polysaccharides are less informative (Figure 2): they contain a set of signals in the region of 3.04–5.50 ppm, attributable to the methylene group protons of the side substituent and carbohydrate fragments. However, the 1H NMR spectra of TEC, TES, and TEAG contain a signal at δ 11.26–11.72 ppm, which unambiguously indicates the presence of the tetrazole ring in the structure of polysaccharides. This is a signal characteristic of the N–H acidic proton of the unsubstituted tetrazole cycle (43).

13C NMR spectra of (A) TEAG, (B) TEC, and (C) TES.

1H NMR spectra of TEC, TES, and TEAG.

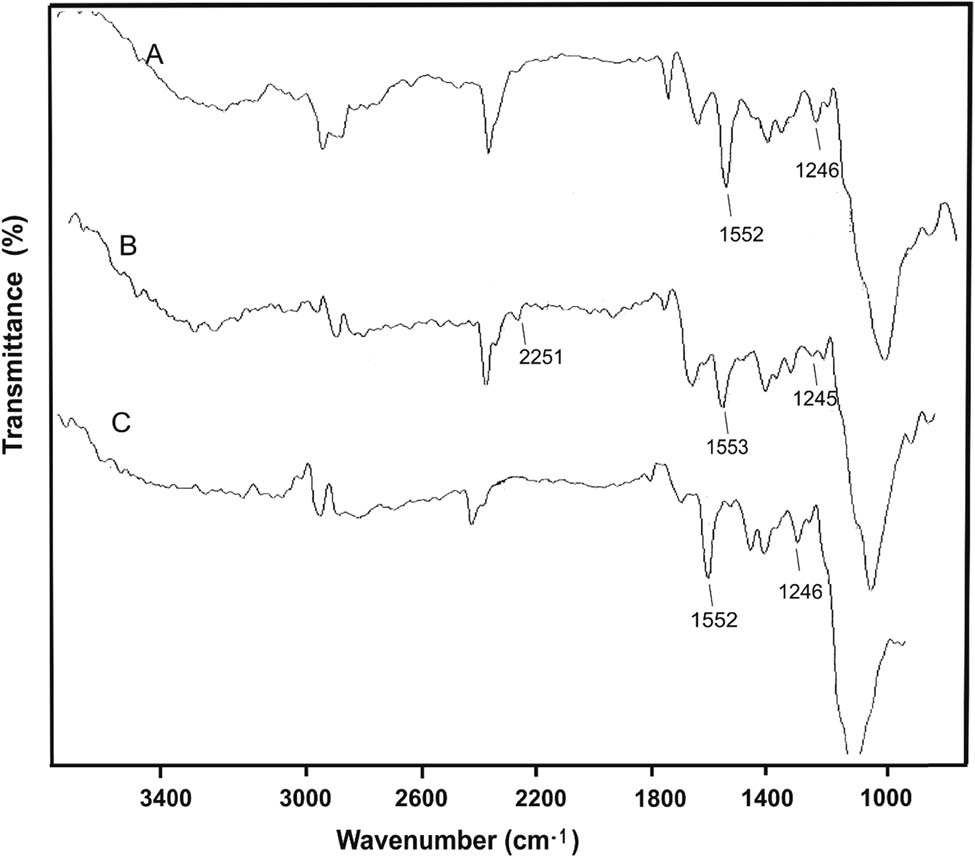

The data of IR spectroscopy also confirm the structure of tetrazole-containing polysaccharides. The IR spectra of TEC, TES, and TEAG contain absorption bands assigned to the N–H vibrations of the unsubstituted tetrazole ring at 3,000–3,700, 1,552–1,553, and 1,245–1,246 cm−1 (Figure 3), respectively. In the spectrum of TEC, there is a low-intense absorption at 2,251 cm−1 indicating the presence of unreacted CN groups.

FTIR spectra of (A) TES, (B) TEC, and (C) TEAG.

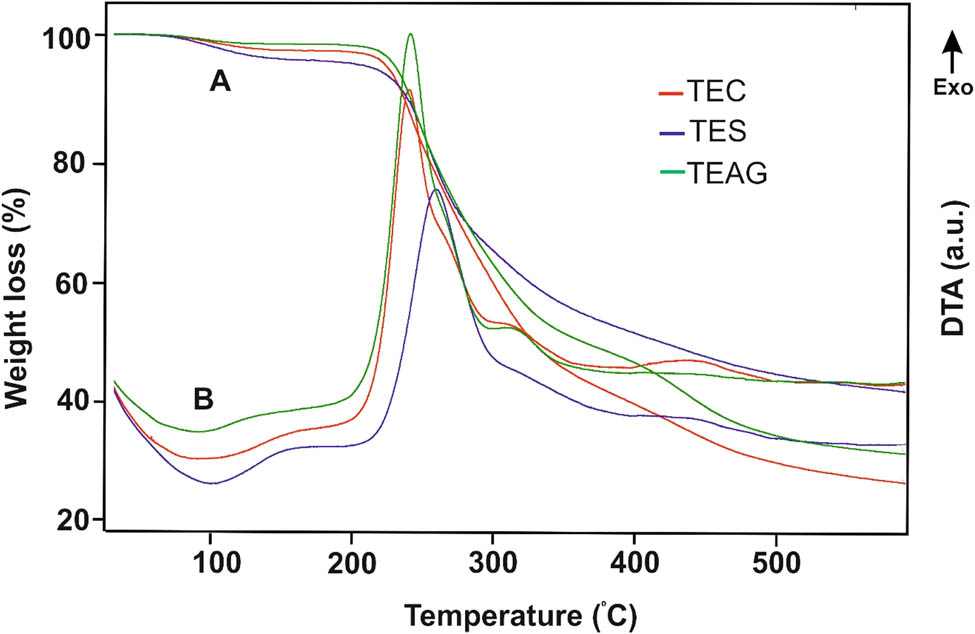

Thus, the derivatives of chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan with a high content of tetrazole structural fragments have been synthesized by sequential cyanoethylation and azidation reactions. The presence of the above heterocycle in the structure of modified polysaccharides is additionally proved by similar thermochemical properties of these and other tetrazole-containing polymers (Figure 4). All three polymers, TEC, TES, and TEAG, decompose without melting upon heating. The onset temperature (220–230°C), the shape of the weight loss curves, and the high exothermicity of the process indicate that polymer decomposition starts with thermal destruction of the tetrazole rings (27). The weaker thermal effect of TEC decomposition in comparison with other tetrazole-containing polysaccharides is owing to the relatively lower specific content of the tetrazole rings in the structure of modified chitosan.

TGA (A) and DTA (B) curves of TEC, TES, and TEAG.

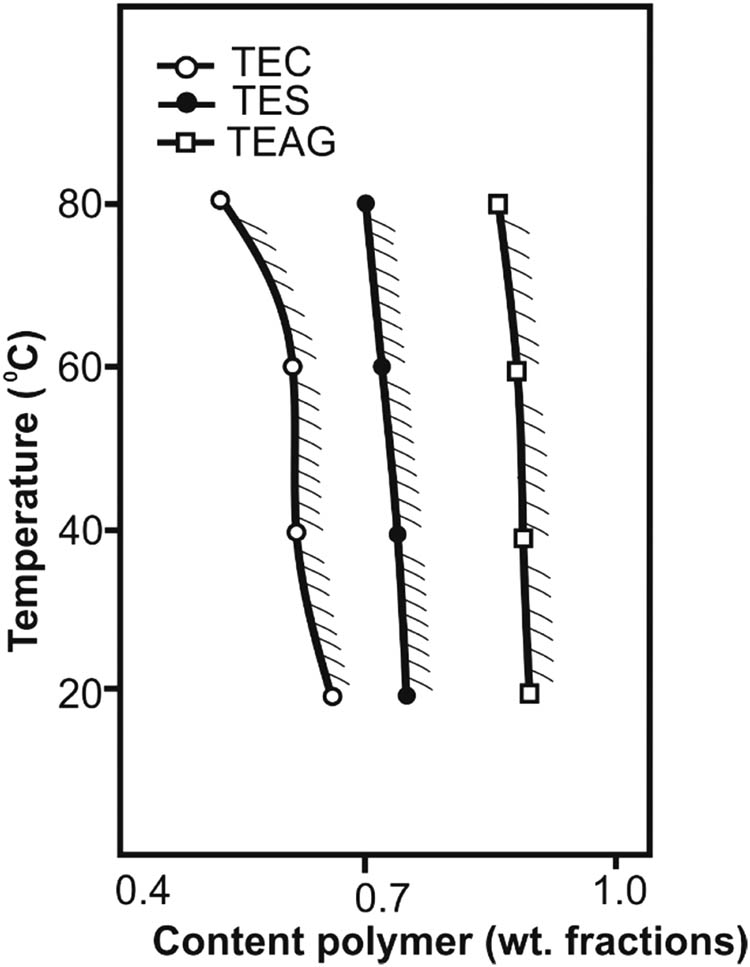

Introduction of acidic N–H unsubstituted tetrazole cycles into the polysaccharides dramatically changes some of their properties and, first of all, solubility (Table 3). Thus, unlike the original polysaccharides, TEC, TES, and TEAG are soluble in DMF, which is a common solvent for the majority of tetrazole-containing polymers. At the same time, TES and TEAG, bearing the tetrazole rings in the nonionized state (H-form), lose their ability to dissolve in water, where they only limitedly swell (Figure 5). Moreover, the least tetrazolated polysaccharide TEC possesses the highest sorption capacity with respect to water. The ionization of 10% of the tetrazole rings (from the total amount) in the macromolecule by converting them into the sodium salt (salt-form) ensures the unlimited compatibility of all modified polysaccharides with water. The minimum pH values of aqueous solutions dissolving TEC, TES, and TEAG are 5.6, 4.7, and 4.0, respectively. In the case of TEC, the macromolecules of which can be transferred into an ionized state due to the protonation of amino groups in an acidic medium, solubility in an aqueous solution is reached at pH < 2. Thus, the presence of tetrazole rings in the structure of chitosan contributes to the solubility of the polymer in a much more acidic region compared to the original polysaccharide (chitosan is soluble in water at pH < 5). On the other hand, modified chitosan can be dissolved in neutral and alkaline media. Other solvents for the tetrazole-containing polymers are aqueous solutions of low-molecular salts (38), in particular, ammonium thiocyanate. Tetrazolated polysaccharides TEC, TES, and TEAG are no exception (Table 3). It should be noted that the minimum dissolving concentrations of ammonium thiocyanate aqueous solutions for these polymers are significantly lower than those for the previously described tetrazolized cellulose and carbo-chain poly-5-vinyltetrazole (PVT) (27).

Solubility of tetrazole-containing polysaccharides

| Solvent | TES | TEAG | TEC |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMF | Sol. | Sol. | Sol. |

| Water | Insol. | Insol. | Insol. |

| Aqueous solution of HCl | Insol. | Insol. | Sol. |

| Aqueous solution of NaOH | Sol. | Sol. | Sol. |

| Aqueous solution of NH4SCNa | 1.5 M | 1.2 M | 1.5 M |

- a

Values of the minimum dissolving concentrations of aqueous solutions of NH4SCN.

Phase diagram of the polymer (TEC, TES, and TEAG)-water system. The shaded region corresponds to the homogeneous state of the system.

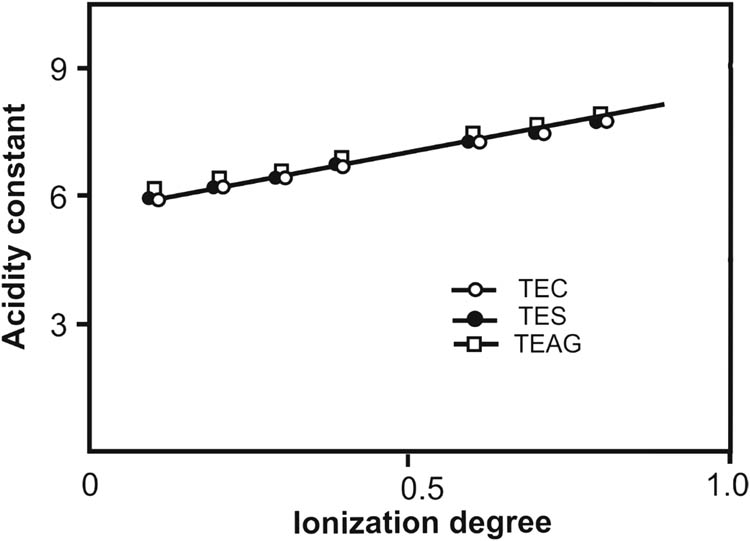

Like other carbo- and hetero-chain polymers containing N–H unsubstituted tetrazole cycles, TEC, TES, and TEAG exhibit the properties of acidic polyelectrolytes. However, in comparison with carbo-chain PVT (pK o 4.65 (38)), the acidic properties of tetrazolized polysaccharides are somewhat inferior. The values of the acidity constants pK o obtained by potentiometric titration of all three modified polysaccharides are approximately the same, ranging from 5.8 to 6.2 (Figure 6). Besides, the rigid-chain structure of the polymers determines the almost linear dependence of pK on the degree of ionization (α) of the polymeric acid.

Acidity constant pK 0 vs the degree of polymer ionization ɑ of TEC, TES, and TEAG.

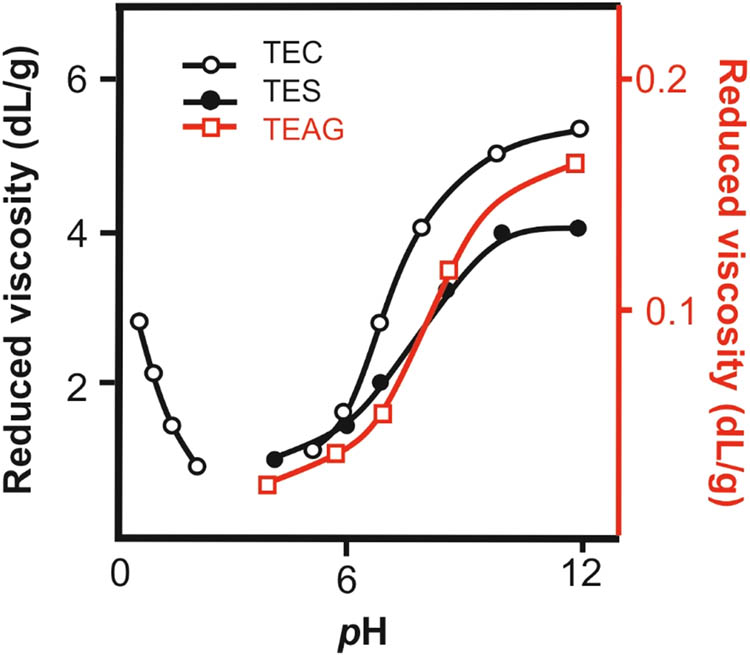

The polyelectrolyte nature of TEC and TES is manifested in the higher viscosity of their aqueous solutions due to the unfolding of polymer coils during ionization of the macromolecules (an increase in the pH of the medium) (Figure 7). It is worthwhile to note that for tetrazolated chitosan, which is a polyampholyte, two regions of unfolding of polymer coils were observed: the alkaline and acidic ones (at pH of 2.0–5.6, TEC is insoluble). However, the amplitude of the viscosity change for the solutions of rigid-chain tetrazolized polysaccharides is significantly lesser than that for flexible-chain tetrazole-containing polymers (39). The lowest viscosities (even upon polymer ionization) were detected for aqueous solutions of TEAG. This fact, along with the weak dependence of viscosity on the pH of the medium, is explained by the most branched structure of the above polysaccharide. Such compaction of macromolecular coils of branched polymers was previously reported for the carbon-chain tetrazole-containing polymers (44). The presence of tetrazole fragments in the side chains of TEAG macromolecules leads to the formation of hydrogen bonds, strong dipole–dipole interactions that, in turn, contribute to the generation of globular macromolecular structures.

Reduced viscosities of aqueous solutions of TEC, TES, and TEAG vs solution pH at 25°C.

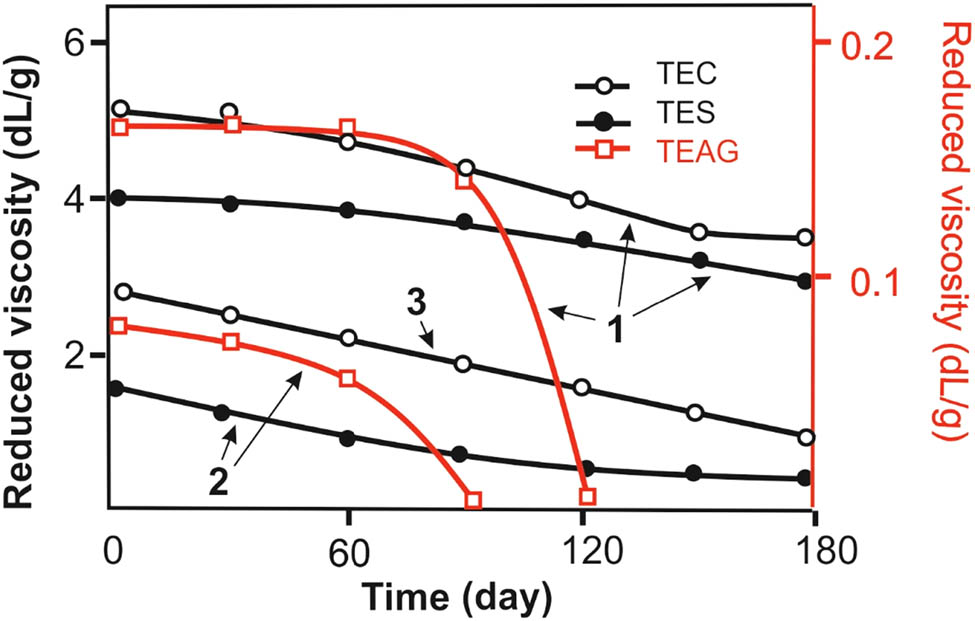

Another difference in the behavior of TEAG in an aqueous solution, which is probably caused by peculiarities of the macromolecule spatial structure, is the lower resistance of the arabinogalactan derivative to hydrolytic cleavage (Figure 8). If for aqueous solutions of TEC and TES with different pH values, a monotonic decrease in the viscosity by 1.5–3 times was observed within 6 months; in the case of TEAG, a sharp decrease in the viscosity of aqueous solutions occurred after 2–3 months. After another month, the viscosity of the solution reached the value of a pure solvent, which indicates the destruction of the high-molecular compound. This process proceeds faster at a pH = 6, when the major amount of tetrazole cycles in macromolecules exist in the nonionized H-form. When pH = 10, tetrazole rings are present exclusively in the salt form. It can be assumed that the acidic properties of the N–H unsubstituted tetrazole ring are manifested in a decrease of resistance of the polysaccharide derivative to hydrolytic cleavage.

Reduced viscosities of aqueous solutions of TEC, TES, and TEAG vs time at 25°C: (1) pH 10, (2) pH 6, and (3) pH 1.

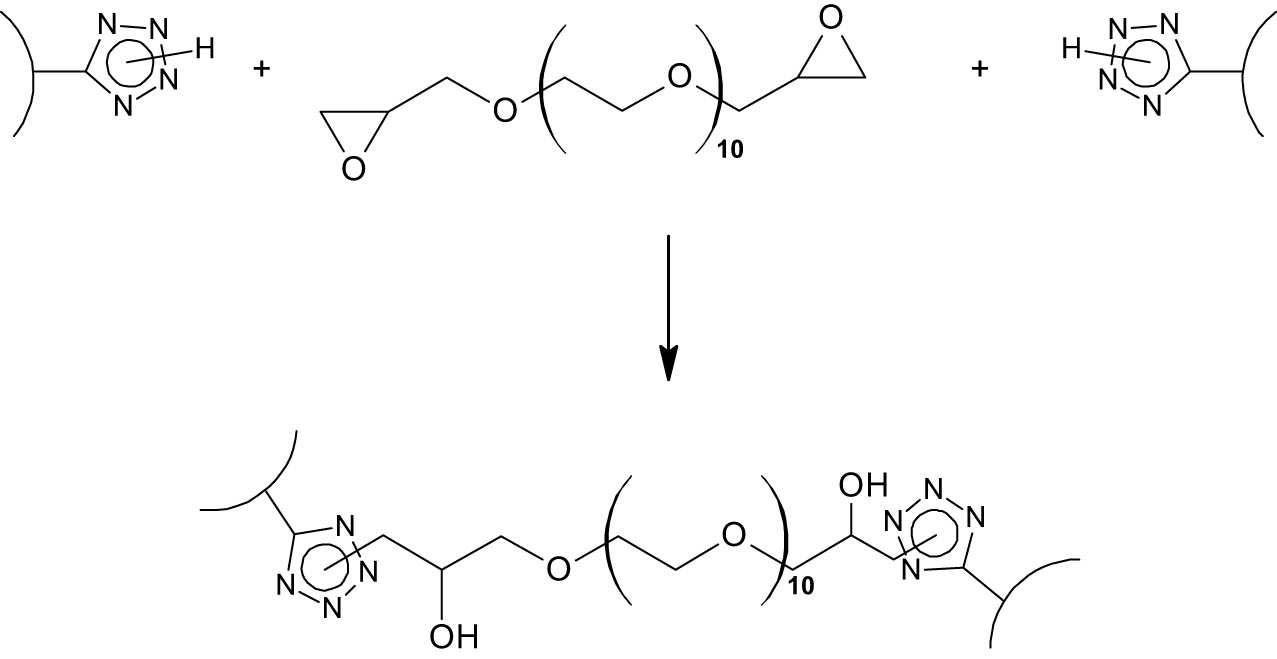

The presence of the tetrazole rings in modified polysaccharides allows the synthesis of cross-linked polymers, which are capable of limited swelling in aqueous media to deliver polyelectrolyte hydrogels. The bridges bonding macromolecules are formed via the reaction between N–H unsubstituted tetrazole rings of the polysaccharide with oxirane cycles of epoxy resins, in particular, PEG-derived ones (Scheme 4). However, the spatial structure of the tetrazolated polysaccharide macromolecule affects the formation of the spatial network. Thus, we failed to obtain a cross-linked polymer by curing highly branched TEAG with epoxy resin. Under similar conditions of TES curing, the formation of a cross-linked structure, accompanied by a loss of the reaction system flowing, starts after 27 h. During the curing of the linear TES, the time of the reaction system fluidity loss was only 5 h.

Cross-linking reaction of tetrazolized polysaccharides with epoxy resin.

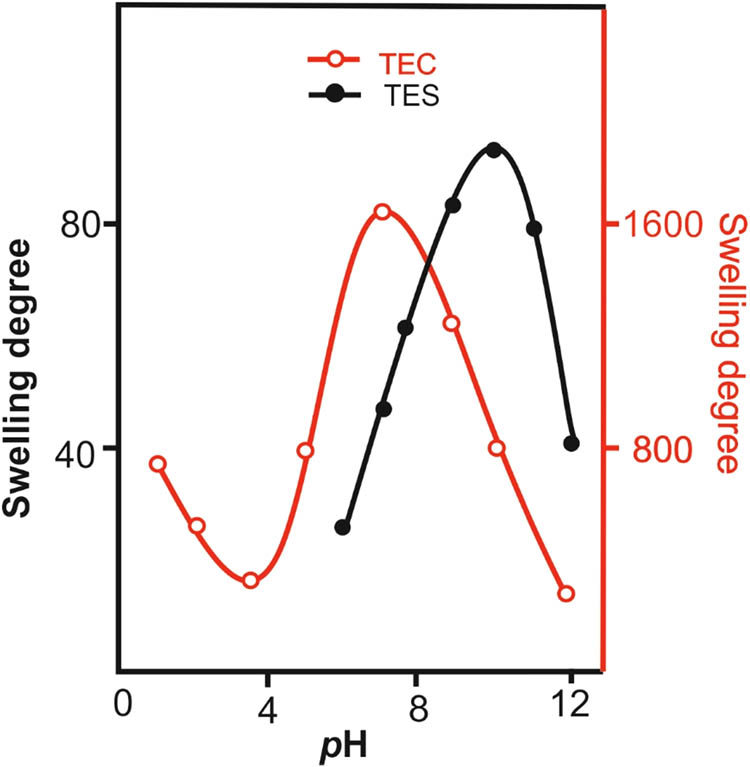

Upon swelling in water, the samples of cross-linked TEC and TES form hydrogels of a polyelectrolyte nature. The equilibrium degree of swelling of such hydrogels strongly depends on the pH of the medium since it is determined by the degree of macromolecules ionization. For TEC and TES-based hydrogels, the values of hydrogel swelling degree at different pH values of the medium corresponding to an extreme dependence (typical for cross-linked acidic polyelectrolytes) with a maximum of swelling in the alkaline region (Figure 9). In addition, the polyampholytic nature of the cross-linked TEC hydrogel is manifested by higher degrees of swelling also in the acidic region. From this point, solutions and hydrogels of the modified polysaccharides are similar. However, there is a difference. For aqueous solutions of TES at pH < 4.7 and TEC at pH of 2.0–5.6, the polymer precipitates into a separate phase. In the case of cross-linked TEC and TES, the polymers do not precipitate even in the area of maximum collapse but remain in the form of water-filled gel substances.

Degrees of swelling of cross-linked TEC and TES in water at 25°C vs pH of the medium.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, it has been shown that the modification presented in this article and described earlier only for cellulose and chitosan, can be successfully employed to introduce the tetrazole cycles into the structure of almost any polysaccharide. It should be especially noted that the azidation of cyanoethyl precursors affords an N–H unsubstituted tetrazole ring. The presence of such functional fragment results in dramatic change of natural polymer properties: the solubility alters, the features of acidic polyelectrolytes appear (in the case of tetrazolated chitosan, polyampholytic properties), and various reactivities inherent in tetrazole-containing polymers emerges. This provides new opportunities for further modification of polymers, in particular, for the design of water-compatible cross-linked polymers and hydrogels, which are sensitive to changes of various environmental parameters. Considering the intrinsic physiological activity of polysaccharides and tetrazole fragment, the biodegradability of the polymer matrix, synthesized polymers can be considered as the basis for the creation of drugs of various therapeutic action or as “smart” polymer carriers of drugs for their point delivery and controlled release in a living organism.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Government Assignment for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Agreement No. 075-03-2020-176/3; project code in Parus 8: FZZE-2020-0022) and Russian Foundation for Basic Researches (project 20-33-90023).

-

Author contributions: Fedor A. Pokatilov: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing – original draft; Helen V. Akamova: formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, visualization, writing – original draft; Valery N. Kizhnyaev: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, project administration, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

(1) Dumitriu S. Polysaccharides. Structural diversity and functional versatility. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2005.10.1201/9781420030822Search in Google Scholar

(2) Belgacem MN, Gandini A. Monomers, Polymers and Composites from Renewable Resources. Amsterdam; London; New York: Elsevier; 2008.Search in Google Scholar

(3) Rinaudo M. Chitin and chitosan: properties and application. Progr Polym Sci. 2006;31(7):603–32. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2006.06.001.Search in Google Scholar

(4) Czaja WK, Young DJ, Kawecki M, Brown JRRM. The future prospects of microbial cellulose in biomedical applications. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(1):1–12. 10.1021/bm060620d.Search in Google Scholar

(5) Pillai CKS, Paul W, Sharma CHP. Chitin and chitosan polymers: chemistry, solubility and fiber formation. Progr Polym Sci. 2009;34(7):641–78. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2009.04.001.Search in Google Scholar

(6) Kean T, Thanou M. Biodegradation, biodistribution and toxicity of chitosan. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2010;62(1):3–11. 10.1016/j.addr.2009.09.004.Search in Google Scholar

(7) Fox SC, Li B, Xu D, Edgar KJ. Regioselective esterification and etherification of cellulose: a review. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(6):1956–72. 10.1021/bm200260d.Search in Google Scholar

(8) Kritchenkov AS, Andranovits S, Skorik YA. Chitosan and its derivatives: vectors in gene therapy. Russ Chem Rev. 2017;86(3):231–9. 10.1070/RCR4636.Search in Google Scholar

(9) Badawy MEI. Chemical modification of chitosan: synthesis and biological activity of new heterocyclic chitosan derivatives. Polym Int. 2000;57(2):254–61. 10.1002/pi.2333.Search in Google Scholar

(10) Heinze T, Liebert T. Unconventional methods in cellulose functionalization. Progr Polym Sci. 2001;26(9):1689–762. 10.1016/S0079-6700(01)00022-3.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Grote C, Heinze T. Starch derivatives of high degree of functionalization 11: studies on alternative acylation of starch with long-chain fatty acids homogeneously in N,N-dimethyl acetamide/LiCl/. Cellulose. 2005;12(4):435–44. 10.1007/s10570-005-2178-z.Search in Google Scholar

(12) Koschella A, Fenn D, Illy N, Heinze T. Regioselectively functionalized cellulose derivatives: a mini review. Macromol Symp. 2006;244(1):59–73. 10.1002/masy.200651205.Search in Google Scholar

(13) Pan Y, Luo X, Zhu A, Dai SH. Synthesis and physicochemical properties of biocompatible N-carboxyethylchitosan. J Biomat Sci. 2009;20:981–92. 10.1163/156856209X444385.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(14) Philippova OE, Korchagina EV. Chitosan and its hydrophobic derivatives: Preparation and aggregation in dilute aqueous solutions. Polym Sci Ser A. 2012;54(7):552–72. 10.1134/S0965545X12060107.Search in Google Scholar

(15) Liu H, Zhao YU, Cheng S, Huang N, Leng Y. Syntheses of novel chitosan derivative with excellent solubility, anticoagulation, and antibacterial property by chemical modification. J Appl Polym Sci. 2012;124:2641–8. 10.1002/app.34889.Search in Google Scholar

(16) Tkacheva NI, Morozov SV, Grigor’ev IA, Mognonov DM, Kolchanov NA. Modification of cellulose as a promising direction in the design of new materials. Polym Sci Ser B. 2013;55(7–8):409–29. 10.1134/S1560090413070063.Search in Google Scholar

(17) Masina N, Choonara YE, Kumar P, Toit L, Govender M, Indermun S, et al. A review of the chemical modification techniques of starch. Carbohydrate Polym. 2017;157:1226–36. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.09.094.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(18) Mochalova AE, Smirnova LA. State of the art in the targeted modification of chitosan. Polym Sci Ser B. 2018;60(2):131–61. 10.1134/S1560090418020045.Search in Google Scholar

(19) Fan Y, Picchioni F. Modification of starch: a review on the application of “green” solvents and controlled functionalization. Carbohydrate Polym. 2020;241:1–19. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116350.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(20) Pestov AV, Bratskaya SYU, Azarova YUA, Yatluka YUG. Imidazole-containing chitosan derivative:a new synthetic approach and sorption properties. Russ Chem Bul. 2012;61(10):1959–64. 10.1007/s11172-012-0271-7.Search in Google Scholar

(21) Dietrich M, Delaittre G, Blinco JP, Inglis AJ, Bruns M, Barner-Kowollik CH. Photoclickable surfaces for profluorescent covalent polymer coatings. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:304–12. 10.1002/adfm.201102068.Search in Google Scholar

(22) Hufendiek A, Carlmark A, Meier MAR, Barner-Kowollik CH. Fluorescent covalently cross-linked cellulose networks via light-induced ligation. ACS Macro Lett. 2016;5(1):139–43. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.5b00806.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(23) Klapoetke TM. Structure and bonding: high energy density compounds. Vol. 125, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag; 2007.Search in Google Scholar

(24) Betzler FM, Klapotke ThM, Sproll S. Energetic nitrogen-rich polymers based on cellulose. Centr Eur J Energetic Materials. 2011;8(3):157–71.Search in Google Scholar

(25) Berezin AS, Ishmetova RI, Rusinov GL, Skorik YUA. Tetrazole derivatives of chitosan: synthetic approaches and evaluation of toxicity. Russ Chem Bull. 2014;63(7):1624–32. 10.1007/s11172-014-0645-0.Search in Google Scholar

(26) Kritchenkov AS, Lipkan NA, Kurliuk AV, Shakola TV, Egorov AR, Volkova OV, et al. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of chitin tetrazole derivatives. Pharm Chem J. 2020;54(2):138–41. 10.1007/s11094-020-02180-4.Search in Google Scholar

(27) Pokatilov FA, Kizhnyaev VN, Akamova EV, Edel’shtein OA. Effect of alkylation of tetrazole rings on the properties of carbochain and heterochain tetrazole-containing. Polym Sci Ser B. 2020;62(3):190–5. 10.1134/S1560090420030124.Search in Google Scholar

(28) Ghule VD, Radhakrishnan S, Jadhan PM. Computational studies on tetrazole derivatives as potential high energy materials. Struct Chem. 2011;22:775–82. 10.1007/s11224-011-9755-6.Search in Google Scholar

(29) Ostrovskii VA, Koldobskii GI, Trifonov RE. Comprehensive heterocyclic chemistry III. Tetrazoles. 2008;6:257–423.10.1016/B978-008044992-0.00517-4Search in Google Scholar

(30) Kizhnyaev VN, Golobokova TV, Pokatilov FA, Vereshchagin LI, Estrin YAI. Synthesis of energetic triazole- and tetrazole-containing oligomers and polymers. Chem Heterocycl Comp. 2017;53(6/7):682–92. 10.1007/s10593-017-2109-6.Search in Google Scholar

(31) Tarchoun AF, Trache D, Klapötke THM, Khimeche K. Tetrazole-functionalized microcrystalline cellulose: A promising biopolymer for advanced energetic materials. Chem Eng J. 2020;400:125960. 10.1016/j.cej.2020.125960.Search in Google Scholar

(32) Tarchoun AF, Trache D, Klapötke THM, Abdelaziz A, Derradji M, Bekhouche S. Chemical design and characterization of cellulosic derivatives containing high-nitrogen functional groups: towards the next generation of energetic biopolymers. Defence Technology. 2021. 10.1016/j.dt.2021.03.009.Search in Google Scholar

(33) Ostrovskii VA, Popova EA, Trifonov RE. Medicinal chemistry of tetrazole. Russ Chem Bull. 2012;61(4):768–80. 10.1007/s11172-012-0108-4.Search in Google Scholar

(34) Ostrovskii VA, Popova EA, Trifonov RE. Developments in tetrazole chemistry 2009-2016. Adv Heterocycl Chem. 2017;123:1–62. 10.1016/bs.aihch.2016.12.003.Search in Google Scholar

(35) Myznikov LV, Vorona SV, Zevatskii YE. Biologically active compounds and drugs in the tetrazole series. Chem Heterocycl Comp. 2021;57:224–33. 10.1007/s10593-021-02897-4.Search in Google Scholar

(36) Kritchenkov AS, Egorov AR, Krytchankou IS, Dubashynskaya NV, Volkova OV, Shakola TV, et al. Synthesis of novel 1H-tetrazole derivatives of chitosan via metal-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. Catalytic and antibacterial properties of [3-(1H-tetrazole-5-yl)ethyl]chitosan and its nanoparticles. Int J Biological Macromol. 2009;132:340–50. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.153.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(37) Dacrory S, Fahim AM. Synthesis, anti-proliferative activity, computational studies of tetrazole cellulose utilizing different homogenous catalyst. Carbohydrate Polym. 2020;229:115537. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115537.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(38) Kizhnyaev VN, Pokatilov FA, Vereshchagin LI. Carbochain polymers with oxadiazole triazole, and tetrazole cycles. Polym Sci Ser C. 2008;50(1):1–21. 10.1134/S1811238208010013.Search in Google Scholar

(39) Pokatilov FA, Kizhnyaev VN. Properties of new polyelectrolytes based on cellulose and poly(vinyl alcohol). Polym Sci Ser A. 2012;54(11):894–99. 10.1134/S0965545X12090076.Search in Google Scholar

(40) Pokatilov FA, Kizhnyaev VN, Zhitov RG, Krakhotkina EA. Network polymers based on tetrazolylethyl cellulose ether. Russ J Appl Chem. 2016;89(12):1990–6. 10.1134/S1070427216120259.Search in Google Scholar

(41) Kashkouli KI, Torkzadeh-Mahani M, Mosaddegh E. Synthesis and characterization of aminotetrazole-functionalized magnetic chitosan nanocomposite as a novel nanocarrier for targeted gene delivery. Materials Sci Eng. 2018;89:166–74. 10.1016/j.msec.2018.03.032.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(42) Andriyanova NA, Smirnova LA, Semchikov YUD, Kir’yanov KV, Zaborshchikova NV, Ur’yash VF, et al. Synthesis of cyanoethyl chitosan derivatives. Polym Sci Ser A. 2006;48(5):483–88. 10.1134/S0965545X06050051.Search in Google Scholar

(43) Kizhnyaev VN, Vereshchagin LI. Vinyltetrazoles. Irkutsk: Irkutsk State University; 2003.Search in Google Scholar

(44) Kizhnyaev VN, Pokatilov FA, Vereshchagin LI. Branched tetrazole-containing polymers. Polym Sci Ser A. 2007;49(1):28–34. 10.1134/S0965545X0701004X.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Fedor A. Pokatilov et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes