Abstract

Epoxy/polyamic acid (EP/PAA) adhesives with high polyimide precursor-PAA content have been synthesized and then cured. The structure, thermal, and adhesive properties were investigated by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, thermogravimetric analysis, and tensile shear test. The effects of PAA content and curing process on the tensile shear strength were also studied. The results showed that the addition of PAA improved the heat resistance and reduced the water absorption. EP/PAA adhesive kept good adhesion. A kind of EP/PAA composite adhesive with excellent comprehensive properties was prepared in this study.

1 Introduction

Flexible printed circuits (FPC) are widely used in telecommunication, computer, automobile, and electronic fields due to their excellent performance (1,2,3,4). With the rapid development of microelectronics industry, FPC are required to have lower dielectric constant, higher temperature resistance, and better processability (5). Flexible copper clad laminate (FCCL) is an indispensable material for flexible printed circuit board (6,7). According to the presence or absence of adhesive, FCCL can be divided into three-layer FCCL (3L-FCCL) and double-layer FCCL (2L-FCCL) (8). 3L-FCCL is composed of copper foil, insulation substrate, and adhesive, which is the most widely used FCCL for its simple process and low cost (9). The adhesive bonding copper foil and insulating layer are the only products that have not achieved industrial standardization, which still directly determines the performance of 3L-FCCL.

At present, the adhesive used in 3L-FCCL mainly includes epoxy resins, acrylate, polyimide, polyester, and polyurethane (10), among which epoxy resin was widely investigated because of its excellent adhesion, moisture resistance, and chemical corrosion resistance (11,12,13,14). The studies on epoxy resins such as curing kinetics (15), flame retardant property (16), and toughness (17) of epoxy (EP) have become a hotspot. Moreover, the long-term use of epoxy resin cannot meet the application of 3L-FCCL at high temperature (18). Therefore, it is urgent for epoxy resin to be modified to adapt to the current development in the microelectronics industry. Gholipour-Mahmoudalilou et al. (19) improved the thermal properties of epoxy resin by preparing new curing agent of poly(amidoamine) dendrimer-grafted graphene oxide. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) results showed that decomposition temperature was improved compared to pure epoxy resin. Tao et al. (20) synthesized epoxy resin containing imine ring and siloxane. The results showed that the fully cured epoxy resin had good thermal stability and the 10% weight loss temperature was up to 365°C. Wang et al. (21) modified epoxy resin by bentonite. As the content of the bentonite increases, the heat resistance of the sample increases, and the 5% weight loss temperature of the system increases by 3.2% when the amount of the bentonite added is 10%.

Polyimide is also used as FCCL adhesive due to its low dielectric constant and high heat resistance (22,23,24,25,26). Tasaki et al. (27) developed soluble polyimides with good heat resistance and low dielectric constant/dissipation factor characteristics. The 10% weight loss temperature of polyimides was 455°C, which can be used as adhesive for 3L-FCCL. However, pure polyimide has the disadvantages of weaker adhesion with copper foil and higher cost than epoxy resin.

The combination of polyimide and epoxy resin is expected to balance the adhesive properties. However, it is difficult for polyimide to be directly melted and mixed with epoxy resin. Polyamide acid (PAA), as a precursor of polyimide, became a good candidate for mixing or even reacting with epoxy resin. At present, studies on PAA-modified epoxy resin mainly focused on thermal properties and curing kinetics. For instance, Yong et al. (28) investigated modification of epoxy resin with different contents of PAA varying from 1% to 10%. The onset temperature of thermal decomposition and the flexural properties of epoxy resin simultaneously increased after being modified by PAA. Armin Majd et al. (29) prepared PAAs through reaction between 4,4′-biphthalic dianhydride and 3,3′-dihydroxybenzidine and then mixed with epoxy resin. The results showed that the 10% weight loss temperature for EP with 5 wt% PAA improved by around 13°C. However, the mechanical properties of epoxy resins studied in these two works mentioned above did not include the tensile shear strength. Tensile shear strength of epoxy resin was one of the most important parameters for EP used as adhesive in 3L-FCCL. Besides, study on modifying epoxy resin with large polyimide content was rare.

In this study, the epoxy resin with EP equivalent of 170 was cured by self-made PAA without other curing agents. The effects of PAA content and curing process on the tensile shear strength and heat resistance of the epoxy resin were studied. Compared with the work of using PAA to modify epoxy resin (28,29), this study not only improved the heat resistance of epoxy resin, but also maintained good adhesive properties of epoxy resin. Besides, the optimum curing temperature and curing time of epoxy resin used as adhesive were found.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

4,4′-Oxydianiline (ODA), benzophenone-3,3′,4,4′-tetracarboxylic dianhydride (BTDA), and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) were purchased from Shanghai Titan Technology Co., Ltd. The phenol A epoxy resin used in this study was supplied by Shanghai Hummer Construction Technology Co., Ltd. All the reagents were utilized as supplied without further purification.

2.2 Preparation of PAA

The polymerization procedure for the synthesis of PAA was as follows. ODA (4.025 g, 0.0201 mol) was added into 250 mL three-necked flask and NMP (42 g) was used as a solvent. After ODA was completely dissolved, BTDA (6.445 g, 0.02 mol) was added, and the mixture was reacted for 6 h. The whole experiment was kept at 0°C under the protection of nitrogen atmosphere. The PAA solution was obtained and stored in the refrigerator at 0°C.

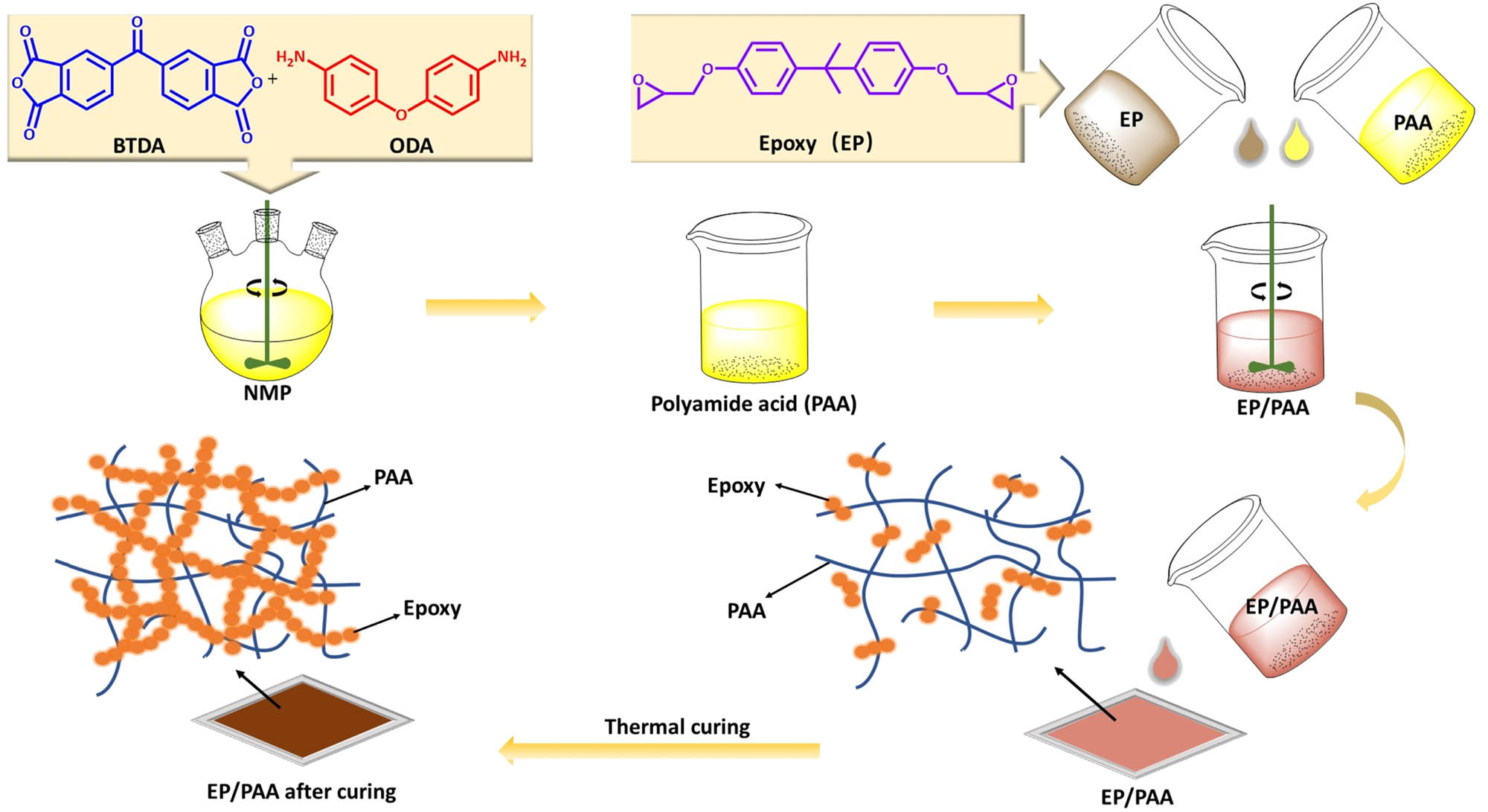

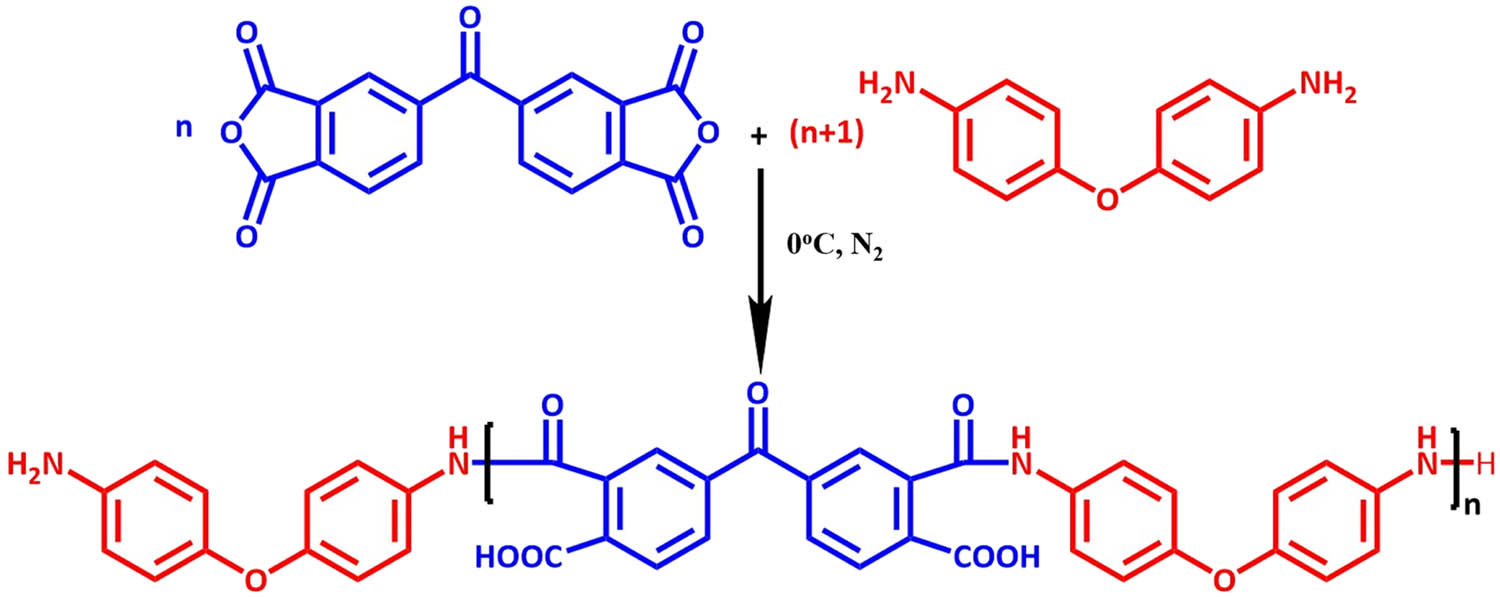

The reaction scheme for the EP/PAA is shown in Figure 1 and the synthesis equation of PAA is shown in Figure 2.

The reaction scheme for the epoxy resin modified by PAA.

The reaction equation between BTDA and ODA.

2.3 Blending and curing of epoxy resin modified by PAA

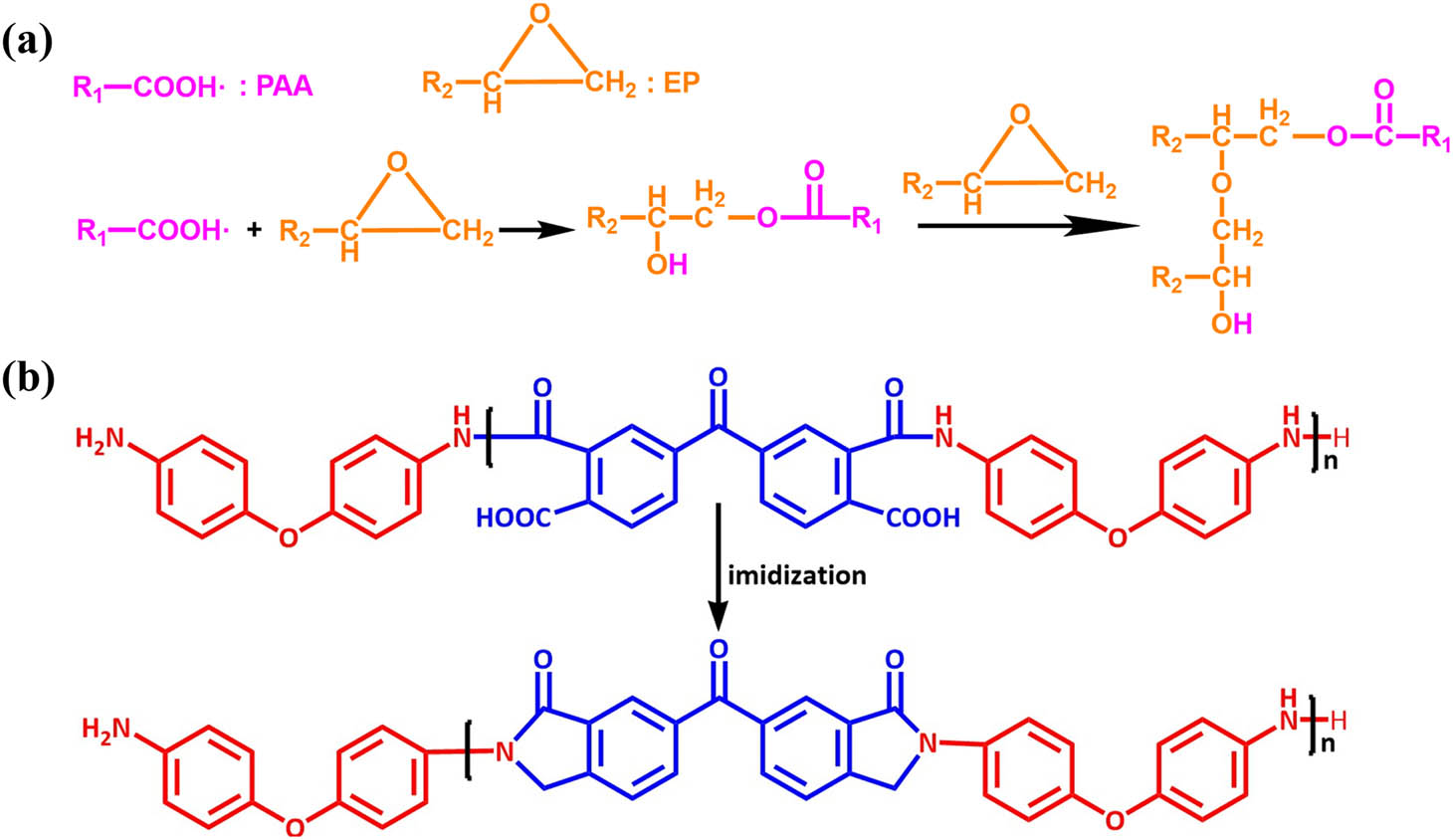

The epoxy resin was mixed with PAA solution in various weight ratios according to Table 1. The mixture (EP/PAA) was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. Then, it was put into the blast oven at 70°C for 3 h. EP/PAA was poured into the poly tetra fluoroethylene mold and cured according to the temperature program. The reaction equation during thermal curing is shown in Figure 3.

Component table of EP/PAA

| Items | PAA content (wt%) |

|---|---|

| E 1 | 20 |

| E 2 | 40 |

| E 3 | 60 |

| E 4 | 70 |

| E 5 | 80 |

| E 6 | 90 |

The reaction equation during thermal curing: (a) the reaction between PAA with EP and (b) the thermal imidization reaction of PAA.

2.4 Characterization

Analysis using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; Equinox 55) with a resolution of 0.5 cm−1 in the range of 500–4,000 cm−1 was performed. TGA (STA 449 C) was performed from room temperature to 800°C at a heating rate of 10°C·min−1 in nitrogen environment. The tensile shear strength was evaluated at room temperature using universal testing machine (TES50T) according to ISO 4587:2003. The water absorption was tested according to ISO 62:2008. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained with a Quanta 200 FEG field emission microscope and all samples were brittle broken with liquid nitrogen and coated with gold by sputtering prior to observation.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 FTIR analysis

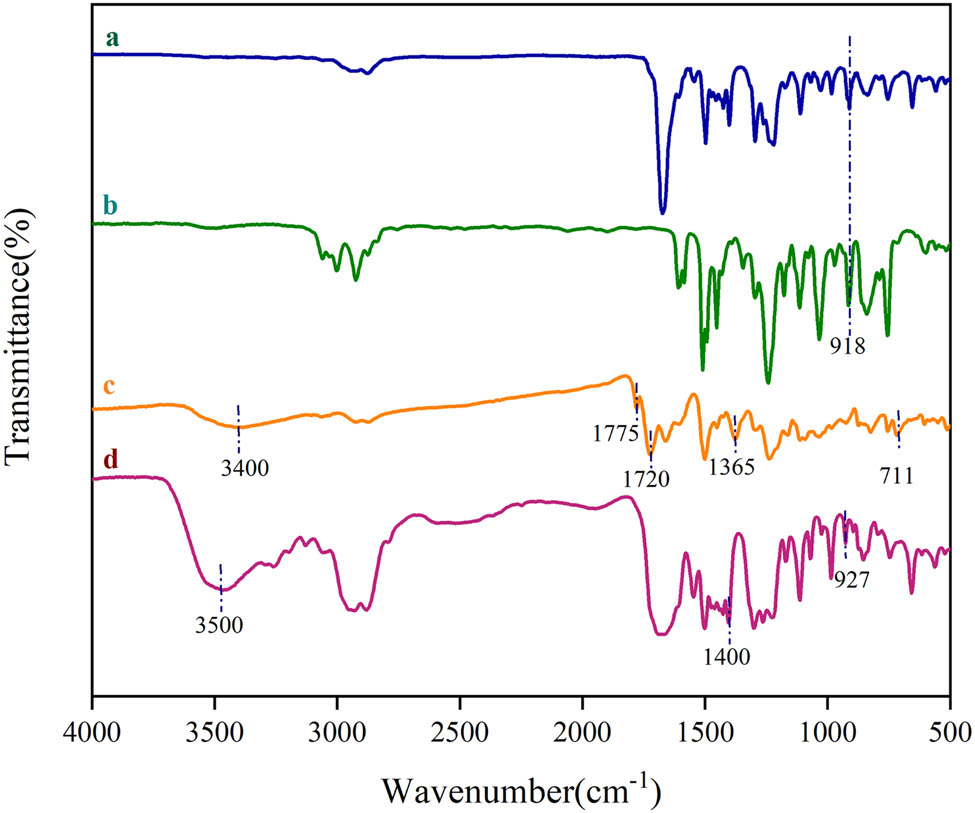

The FTIR spectra of EP, PAA, EP/PAA before and after curing are shown in Figure 4. There is no carbonyl C═O absorption peak at 860, 800, 1,800, and 1,750 cm−1 in the infrared absorption of PAA (curve d), indicating that there is no anhydride group in PAA, and the PAA is successfully prepared.

FTIR spectra of (a) EP/PAA before curing, (b) EP, (c) EP/PAA after curing, and (d) PAA.

The characteristic peak of EP group can be found at about 918 cm−1 in the EP (curve b) and EP/PAA before curing (curve a), but it disappears in the EP/PAA after curing (curve c), which confirms that the epoxy resin has been completely cured. The peak at 3,400 cm−1 in the EP/PAA after curing is assigned to the characteristic peak of hydroxyl due to the EP-ring opening reaction. The absorption peaks at 1,720 cm−1 (C═O symmetric stretching), 1,775 cm−1 (C═O asymmetric stretching), 1,365 cm−1 (imide C–N stretching), and 711 cm−1 (imide C═O bending) are believed to be the characteristic peaks of the imide architecture arising. In addition, the absence of peaks at 1,547 and 3,464 cm−1 further confirms imidization ring closure.

3.2 Thermal properties

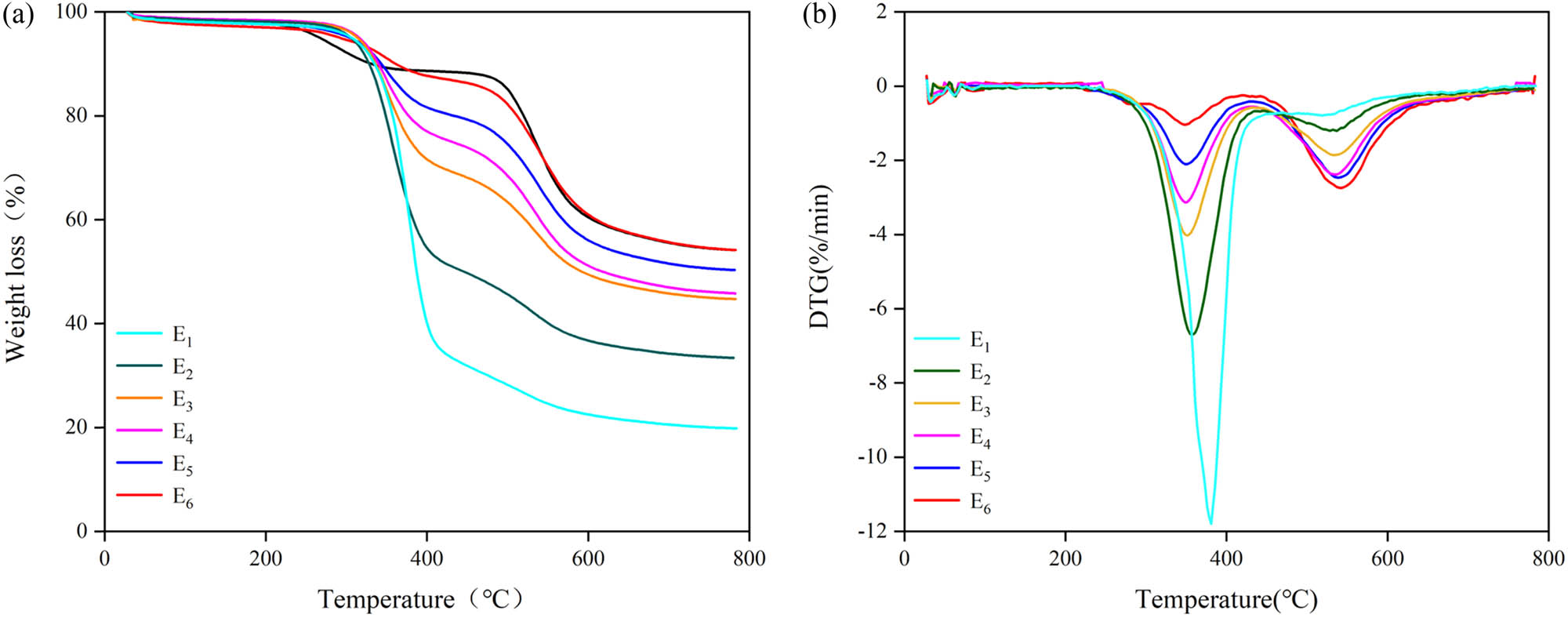

The TGA curves of EP/PAA after curing are depicted in Figure 5. There are two weight loss steps in all curves in Figure 5a. In the first stage, the weight loss between 200°C and 400°C is likely due to the decomposition of epoxy resin (30). The second decomposition step, the weight loss between 400°C and 600°C is maybe contributed to the decomposition of polyimide structure (31). All the EP/PAA after curing samples show good stability before 300°C.

(a) TGA curves and (b) DTG curves of EP/PAA after curing.

The TGA data of EP/PAA after curing is shown in Table 2. The 5% weight loss temperature of all samples is above 300°C and the 10% weight loss temperature is above 330°C, which meets the use requirements of 3L-FCCL. With the increase in the content of PAA, the thermal decomposition temperature increases. For example, the 10% weight loss temperature increases about 20°C with the PAA content increasing from 40% to 80%. The residual weight also increases with the increase in PAA content. With the increase in PAA content, the semi-IPN structure is formed by the entanglement of PAA chains and EP during the curing reaction (28), which improves the heat resistance (32).

TGA data of EP/PAA

| Items | T 5 (°C) | T 10 (°C) | Residual weight (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E 1 | 306 | 327 | 34 |

| E 2 | 314 | 336 | 45 |

| E 3 | 316 | 337 | 46 |

| E 4 | 304 | 343 | 51 |

| E 5 | 342 | 357 | 52 |

| E 6 | 355 | 370 | 55 |

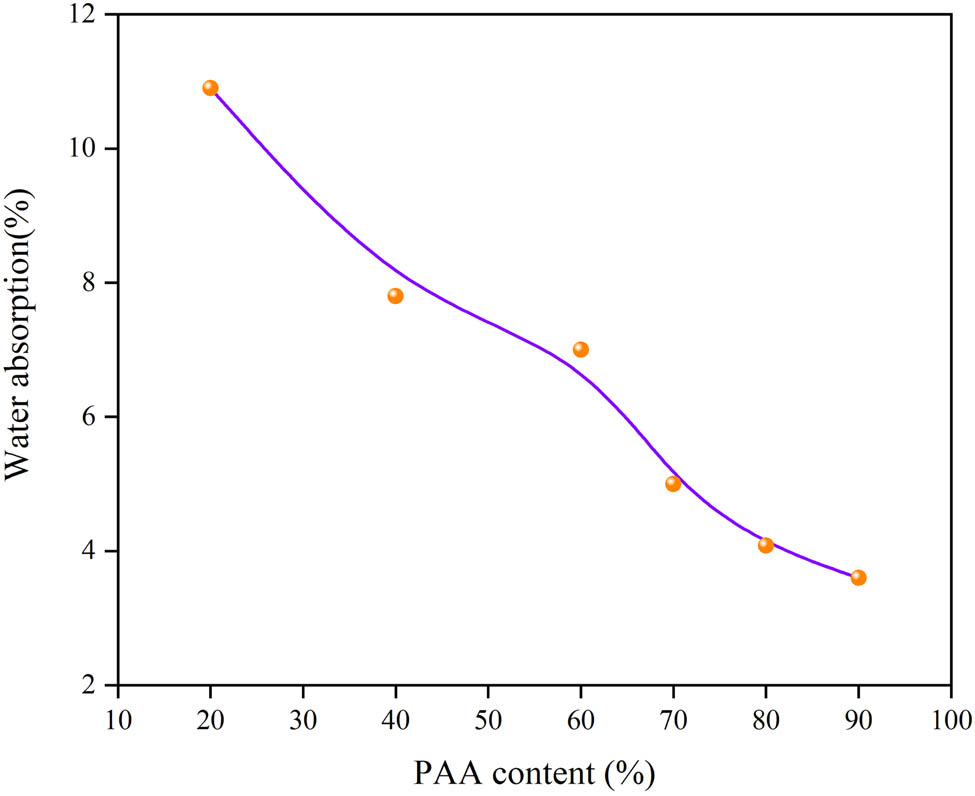

3.3 Water absorption analysis

The hydrophilic groups of epoxy resin will hydrolyze under high temperature and water vapor environment, which lead to the reduction in molecular weight and the hygrothermal aging of epoxy resin. Therefore, it is important to reduce the water absorption of epoxy resin to avoid the failure of 3L-FCCL in humid and warm environment. Figure 6 shows the 24-hour water absorption of EP/PAA after curing. With the increase in PAA content, the water absorption of EP/PAA after curing decreases. The water absorption of E 6 is only 3.6%, which is much lower than that of E 1 (10.9%). The number of polar imide rings for the EP/PAA after curing increases with the increase in the PAA content. The more imide rings created, the more molecular chains attract each other tightly and stack closely under polar action. Hence, it is more difficult for water to penetrate such compact structure.

Water absorption of EP/PAA after curing.

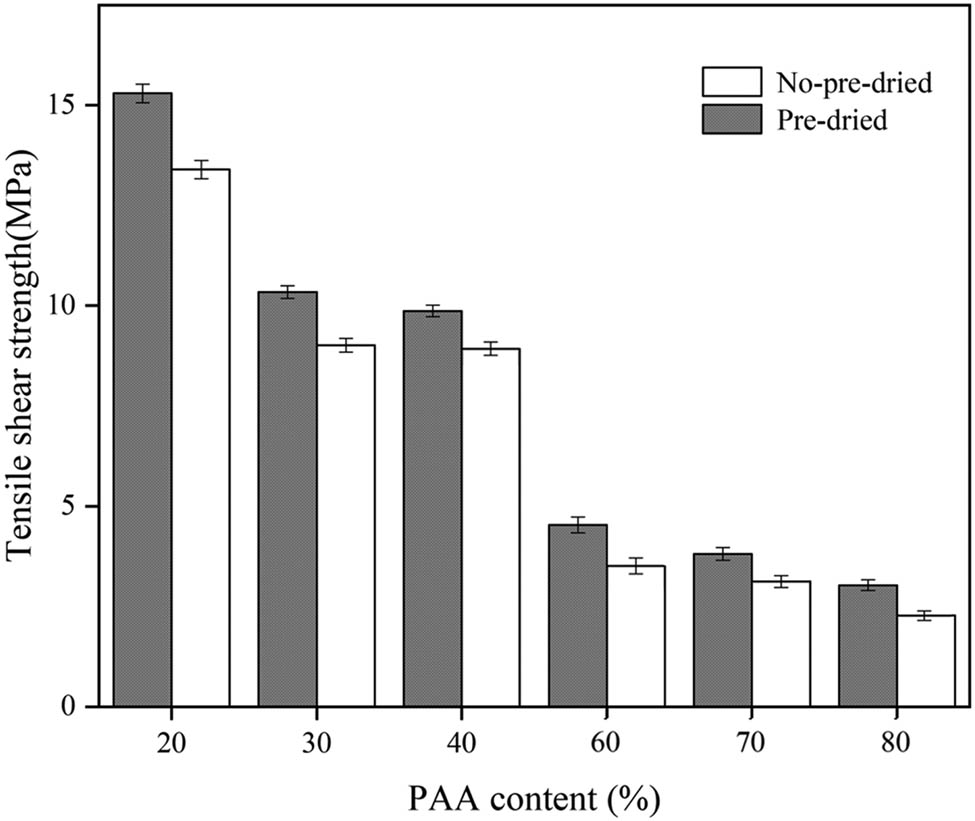

3.4 Tensile shear analysis

Figure 7 shows the tensile shear strength of EP/PAA after curing. The tensile shear strength decreases gradually with the increase in PAA content, and the reasons can be given as follows. On the one hand, high PAA content requires more NMP solvent. NMP is not easy to remove in the process of thermal amination, and the following volatilization will produce bubbles. On the other hand, the increase in PAA content means the decrease in epoxy resin content. The bonding ability of epoxy resin is better than that of PAA due to the EP group, hydroxyl group, etc.

Effects of PAA content and curing treatment on tensile shear strength.

The tensile shear strength of EP/PAA after curing with or without pre-drying curing treatment is also shown in Figure 7. Comparing with that of EP/PAA without pre-drying treatment, the tensile shear strength of EP/PAA with pre-drying treatment is improved. For instance, the tensile shear strength of E 2 with pre-drying treatment (9.87 MPa) is 27% higher than that of EP/PAA without pre-drying treatment (8.93 MPa). The NMP solvent is removed during pre-drying process in the EP/PAA and the influence of solvent on the structure of the adhesive layer is avoided.

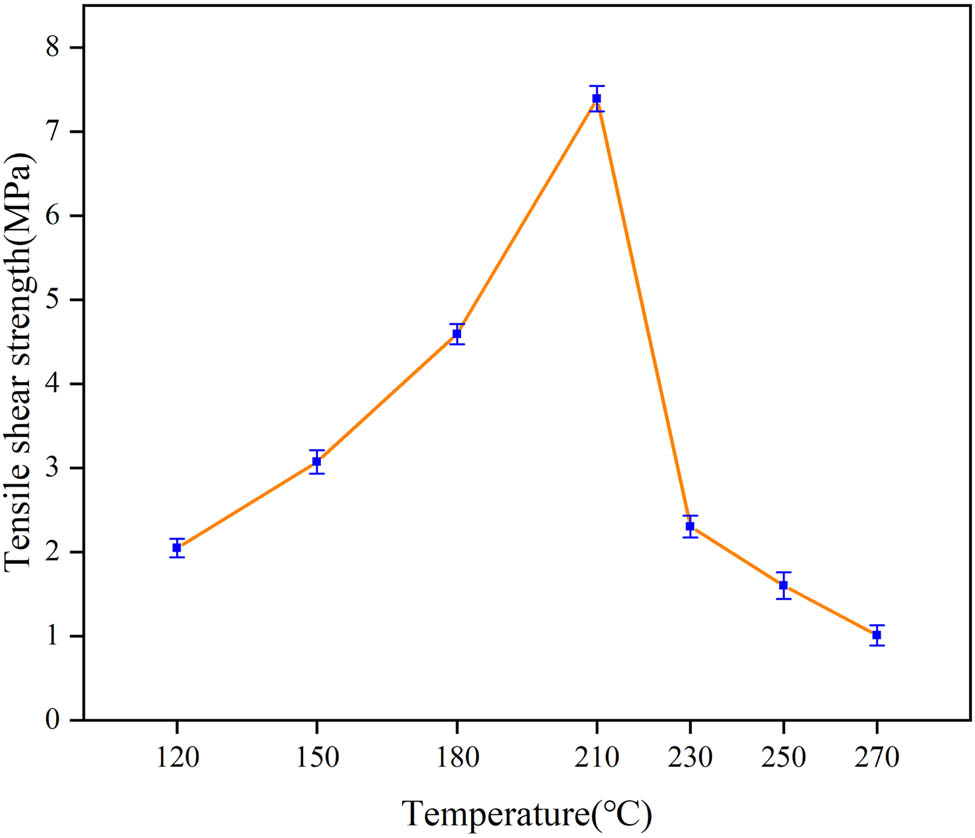

Figure 8 shows the tensile shear strength of E 2 cured at different curing temperatures. The tensile shear strength first increases and then decreases with the increase in temperature. The peak of tensile shear strength (7.39 MPa) is located at 210°C, which is about 6 times higher than the value at 270°C (1.01 MPa). Before 210°C, with the increase in temperature, both the reaction degree between PAA and EP and the polymer crosslinking density increase, which are beneficial for the increase in cohesion strength. However, epoxy resin is a thermosetting resin and the degree of intramolecular crosslinking increases with the increase in temperature. Therefore, excessive crosslinking makes the adhesive layer brittle and the cohesive strength decreases.

Tensile shear strength of E 2 with different curing temperatures.

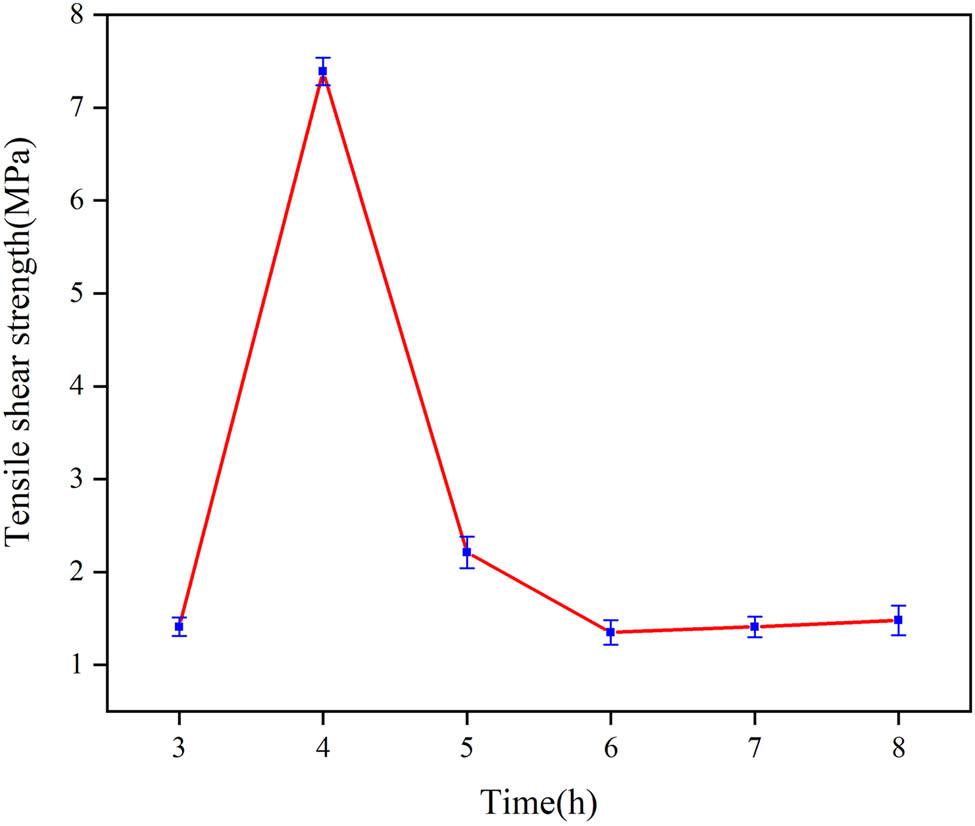

Figure 9 shows the tensile shear strength of E 2 cured at 210°C with different times. Tensile shear strength increases with increasing curing time up to 4 h and then reduces beyond 4 h. It is particularly noteworthy that the peak of tensile shear strength is 7.39 MPa when the curing time is 4 h, which is approximately 4 times higher than that cured for 8 h (1.58 MPa). The degree of reaction between PAA and EP increases with time, leading to first increase in the cohesive strength and then decrease.

Tensile shear strength of E 2 with different curing time.

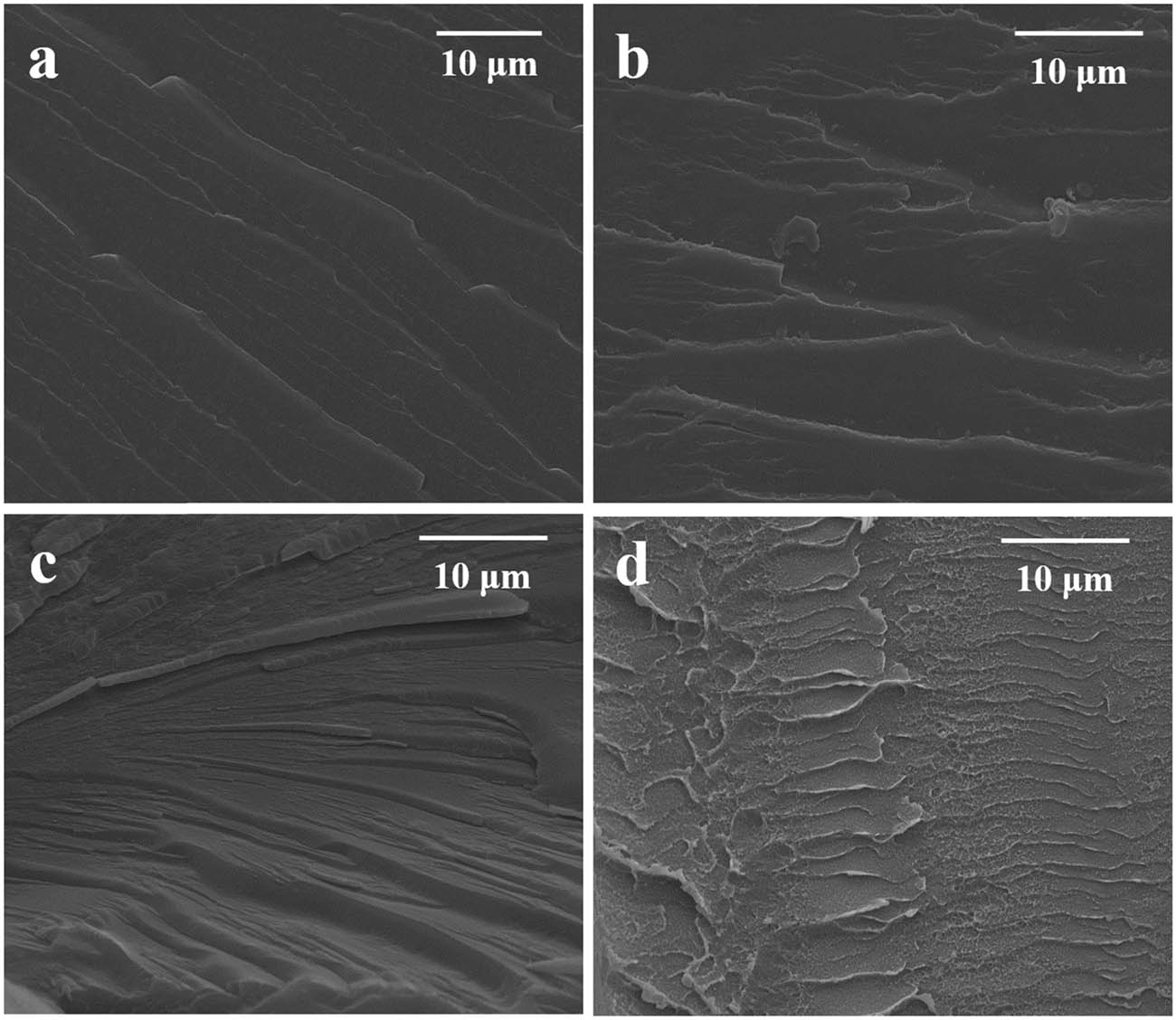

3.5 SEM analysis

Figure 10 shows the SEM images of the fractured surfaces of E 1, E 2, E 3, and E 6. The fractured surface of E 1 shown in Figure 10a is smooth. The river line is shallow and its ability to prevent crack propagation is weak. With the increase in PAA content, the river line becomes thick and strong, as shown in Figure 10c and d. The propagation of cracks in the EP/PAA is limited by the semi-IPN structure and the fracture will absorb more energy.

The SEM images of the fractured surfaces of EP/PAA after curing: (a) E 1, (b) E 2, (c) E 3, and (d) E 6.

4 Conclusion

PAA solution was prepared with BTDA and ODA as monomers and a new modified epoxy resin was prepared by blending epoxy resin with high PAA content. All the EP/PAA after curing samples showed good heat stability and the 10% weight loss temperature could arrive at around 340°C. The tensile shear strength of EP/PAA after curing samples improved after pre-dried curing process. Besides, the optimum curing time and temperature were 4 h and 210°C, respectively. The tensile shear strength reached 7.39 MPa under the optimum curing process. The water absorption decreased with the increase in PAA content. In this study, a new modified epoxy resin with good comprehensive properties was prepared, which meets the requirements of 3L-FCCL at the present stage and has broad application prospects.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank teachers Zhenlei Zhang, Jianguo Wu, and Xueliang Yao of Tongji University for guiding the operation of the equipment during our experiments.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Xiaoyan Xu: writing – review and editing, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, and writing – review and editing; Yan Li: writing – review and editing, formal analysis, and conceptualization; Jinchan Peng: writing – original draft, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, and validation; Qinggang Tan: investigation and formal analysis; Jianjiang Yang: resources; Dedong Hu: resources; Zhihong Chang: investigation and formal analysis

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

(1) Kamiya S, Furuta H, Omiya M. Adhesion energy of Cu/polyimide interface in flexible printed circuits. Serf Coat Tech. 2007;202(4–7):1084–8. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2007.07.061.Search in Google Scholar

(2) Kim Y-T, Kim J-H, Kim D-K, Kwon Y-H. Force sensing model of capacitive hybrid touch sensor using thin-film force sensor and its evaluation. Int J Precis Eng Man. 2015;16(5):981–8. 10.1007/s12541-015-0127-9.Search in Google Scholar

(3) Moschou D, Greathead L, Pantelidis P, Kelleher P, Morgan H, Prodromakis T. Amperometric IFN-γ immunosensors with commercially fabricated PCB sensing electrodes. Biosens Bioelectron. 2016;86:805–10. 10.1016/j.bios.2016.07.075.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(4) Khan Y, Thielens A, Muin S, Ting J, Baumbauer C, Arias AC. A new frontier of printed electronics: flexible hybrid electronics. Adv Mater. 2020;32(15):1905279. 10.1002/adma.201905279.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(5) Song R, Zhao X, Wang Z, Fu H, Han K, Qian W, et al. Sandwiched graphene clad laminate: a binder-free flexible printed circuit board for 5G antenna application. Adv Eng Mater. 2020;22(10):2000451. 10.1002/adem.202000451.Search in Google Scholar

(6) Choi Y-M, Jung J, Lee AS, Hwang SS. Photosensitive hybrid polysilsesquioxanes for etching-free processing of flexible copper clad laminate. Compos Sci Technol. 2021;201:108556. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2020.108556.Search in Google Scholar

(7) Tan Y-Y, Zhang Y, Jiang G-L, Zhi X-X, Xiao X, Wu L, et al. Preparation and properties of inherently black polyimide films with extremely low coefficients of thermal expansion and potential applications for black flexible copper clad laminates. Polymers. 2020;12(3):576. 10.3390/polym12030576.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(8) Li K, Tong L, Jia K, Liu X. Design of flexible copper clad laminate with outstanding adhesion strength induced by chemical bonding. J Mater Sci-Mater. 2014;25(12):5446–51. 10.1007/s10854-014-2327-y.Search in Google Scholar

(9) Noh B-I, Yoon J-W, Jung S-B. Effect of laminating parameters on the adhesion property of flexible copper clad laminate with adhesive layer. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2010;30(1):30–5. 10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2009.07.001.Search in Google Scholar

(10) Aleksandrova LG. Adhesive materials in the production of clad dielectrics for printed circuits. Polym Sci Ser D+. 2013;6(1):54–8. 10.1134/S1995421212040028.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Ahmadi Z. Nanostructured epoxy adhesives: a review. Prog Org Coat. 2019;135:449–53. 10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.06.028.Search in Google Scholar

(12) Wei H, Xia J, Zhou W, Zhou L, Hussain G, Li Q, et al. Adhesion and cohesion of epoxy-based industrial composite coatings. Compos Part B-Eng. 2020;193:108035. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2020.108035.Search in Google Scholar

(13) Pham VH, Ha YW, Kim SH, Jeong HT, Jung MY, Ko BS, et al. Synthesis of epoxy encapsulated organoclay nanocomposite latex via phase inversion emulsification and its gas barrier property. J Ind Eng Chem. 2014;20(1):108–12. 10.1016/j.jiec.2013.04.019.Search in Google Scholar

(14) Su S, Wang H, Zhou C, Wang Y, Liu J. Study on epoxy resin with high elongation-at-break using polyamide and polyether amine as a two-component curing agent. e-Polymers. 2018;18(5):433–9. 10.1515/epoly-2017-0252.Search in Google Scholar

(15) Zhang L, Yang HK, Shi G. Curing kinetics study of epoxy resin/hyperbranched poly(amideamine)s system by non-isothermal and isothermal DSC. e-Polymers. 2010;10(1):136. 10.1515/epoly.2010.10.1.1516.Search in Google Scholar

(16) Li A, Mao P, Liang B. The application of a phosphorus nitrogen flame retardant curing agent in epoxy resin. e-Polymers. 2019;19(1):545–54. 10.1515/epoly-2019-0058.Search in Google Scholar

(17) Zhang X, Lu X, Qiao L, Jiang L, Cao T, Zhang Y. Developing an epoxy resin with high toughness for grouting material via co-polymerization method. e-Polymers. 2019;19(1):489–98. 10.1515/epoly-2019-0052.Search in Google Scholar

(18) Yin B, Zhang J. A novel photocurable modified epoxy resin for high heat resistance coatings. Colloid Polym Sci. 2020;298(10):1303–12. 10.1007/s00396-020-04708-2.Search in Google Scholar

(19) Gholipour-Mahmoudalilou M, Roghani-Mamaqani H, Azimi R, Abdollahi A. Preparation of hyperbranched poly(amidoamine)-grafted graphene nanolayers as a composite and curing agent for epoxy resin. Appl Surf Sci. 2018;428:1061–9. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.09.237.Search in Google Scholar

(20) Tao Z, Yang S, Chen J, Fan L. Synthesis and characterization of imide ring and siloxane-containing cycloaliphatic epoxy resins. Eur Polym J. 2007;43(4):1470–9. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2007.01.039.Search in Google Scholar

(21) Wang J, Deng Z, Huang Z, Li Z, Yue J. Study on preparation and properties of bentonite-modified epoxy sheet molding compound. e-Polymers. 2021;21(1):309–15. 10.1515/epoly-2021-0025.Search in Google Scholar

(22) Nasreen S, Baczkowski ML, Treich GM, Tefferi M, Anastasia C, Ramprasad R, et al. Sn-polyester/polyimide hybrid flexible free-standing film as a tunable dielectric material. Macromol Rapid Comm. 2019;40(3):1800679. 10.1002/marc.201800679.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(23) Deyang J, Tao L, Wenping H, Fuchs H. Recent progress in aromatic polyimide dielectrics for organic electronic devices and circuits. Adv Mater. 2019;31(15):1806070 (19 pp.). 10.1002/adma.201806070.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(24) Maddipatla D, Xingzhe Z, Bose AK, Masihi S, Narakathu BB, Bazuin BJ, et al. A polyimide based force sensor fabricated using additive screen-printing process for flexible electronics. IEEE Access. 2020;8:207813–21. 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3037703.Search in Google Scholar

(25) Junyong C, Haemin S, Jongsun L, Gyungock K, Mi Hye Y, Jae-Won K. A photo-functional electro-optic polyimide with excellent high-temperature stability. Dye Pigment. 2019;163:547–52. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.12.049.Search in Google Scholar

(26) Li S, Yu S, Feng Y. Progress in and prospects for electrical insulating materials. High volt. 2016;1(3):122–9. 10.1049/hve.2016.0034.Search in Google Scholar

(27) Tasaki T, Shiotani A, Yamaguchi T, Sugimoto K, editors. Low Dk/Df polyimide adhesives for low transmission loss substrates. 2017 International Conference on Electronics Packaging (ICEP), 19–22 April 2017. Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2017.10.23919/ICEP.2017.7939410Search in Google Scholar

(28) Yong L, Wei W, Yu C, Pinpin S, Mingchang L, Xiang W. The effects of polyamic acid on curing behavior, thermal stability, and mechanical properties of epoxy/DDS system. J Appl Polym Sci. 2013;127(4):3213–20. 10.1002/app.37759.Search in Google Scholar

(29) Amini Majd A, Mortezaei M, Amiri Amraei I. Curing behavior, thermal, and mechanical properties of epoxy/polyamic acid based on 4,4′-biphthalic dianhydride and 3,3′-dihydroxybenzidine. Polym Eng Sci. 2020;60(8):1917–29. 10.1002/pen.25427.Search in Google Scholar

(30) Fang F, Ran S, Fang Z, Song P, Wang H. Improved flame resistance and thermo-mechanical properties of epoxy resin nanocomposites from functionalized graphene oxide via self-assembly in water. Compos Part B-Eng. 2019;165:406–16. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.01.086.Search in Google Scholar

(31) Leu C-M, Wu Z-W, Wei K-H. Synthesis and properties of covalently bonded layered silicates/polyimide (BTDA-ODA) nanocomposites. Chem Mater. 2002;14(7):3016–21. 10.1021/cm0200240.Search in Google Scholar

(32) Tanaka N, Iijima T, Fukuda W, Tomoi M. Synthesis and properties of interpenetrating polymer networks composed of epoxy resins and polysulphones with cross-linkable pendant vinylbenzyl groups. Polym Int. 1997;42(1):95–106 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0126(199701)42:1<95:AID-PI679 > 3.0.CO;2-C.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 Xiaoyan Xu et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes