Abstract

In recent years, with the rise of an intelligent concept, oral and maxillofacial surgery smart dressing had also attracted the interest of researchers, especially for the pH sensor with flexible medium. In this study, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanofibrous yarn was fabricated by a conjugate electrospinning process and modified with in situ polymerization of polyaniline (PANI) forming a PANI/PVDF yarn. By a weaving process, these yarns could be weaved into a fabric. It was found that both the PANI/PVDF yarn and the fabric showed a sensitivity to pH, about −48.53 mV per pH for yarn and −38.4 mVper pH for fabric, respectively, in the pH range of 4.0–8.0. These results indicated that the prepared PANI-modified PVDF yarn and fabric might have a potential application in intelligent oral and maxillofacial surgery dressings for monitoring wound healing.

1 Introduction

The pH of a substance is one of its basic chemical properties. It was usually detected by pH value, calculated according to the concentration of hydrogen ion (H+), pH = −log(H+) (1). Generally, the pH value is in the range of 0–14, where pH = 7 is neutral, pH < 7 is acidic, and pH > 7 is alkaline. To determine the pH value of substances, different methods were used including optical and electrochemical ones (1). The optical method was based on pH-sensitive chemical dyes, which may show color changes through absorption, scattering, and luminescence, so as to calibrate the pH value (2), such as pH test paper. The electrochemical method was based on pH-sensitive potential, current, or impedance measurement (3), such as pH test pen and other tools.

The determination of pH value was of great significance in many fields, such as chemical industry, environmental monitoring, and medical care (4). It was shown that the pH value around a wound was a dynamic value during its healing process (5,6,7,8,9,10). A healthy skin was usually acidic, and the pH value ranged from 4 to 6. Once the skin was damaged, deep skin could be exposed and tissue fluid exuded, and the pH value might reach to 7.4. With the outbreak of inflammation, the pH value might reach to 8 (5). As for the chronic wounds, the pH value was in the alkaline range of 7–9 (9). Accordingly, by detecting the pH value at the wound site, one could monitor and help to manage the wound healing process (11). For the oral cavity, the nonharmful pH range was 6.0–7.5 (12,13). A pH below 5.5 was greatly harmful to both the hard and soft tissues in oral cavity (13,14). However, conventional pH measurement methods were not suitable for wound and oral and maxillofacial surgery healing monitoring, which may require a flexible pH sensing media and could be combined with wound dressing.

Recently, several flexible pH sensors had been reported (15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23). Wang et al. prepared a wearable bandage with polyaniline (PANI) conducting polymer as the pH-sensitive material and a polyvinyl butyral-based reference membrane to monitor the wound site pH (15). Rahimi et al. fabricated a flexible pH sensor with a screen-printed Ag/AgCl reference electrode, a carbon working electrode, and a pH-sensitive PANI film on a paper (16). Punjiya et al. designed a flexible yarn pH sensor based on the commercial cotton thread coating with carbon and PANI. It was found that the potential was highly sensitive to pH in an electrochemical test (17,18). Moreover, several nanofiber-based flexible pH sensors were prepared by electrospinning process with high pH sensitivity (19,20,21,22,23). However, it was still a challenge to integrate the flexible pH sensors into traditional textile structures (24,25).

In this communication, we proposed a yarn and fabric-based flexible pH sensor. In this context, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) was electrospun into nanofibrous yarn by a conjugate electrospinning process, and then PANI was in situ polymerized on the yarn. Moreover, the yarn could be weaved into a fabric. The pH sensitivity of the yarn and fabric was investigated.

2 Materials and methods

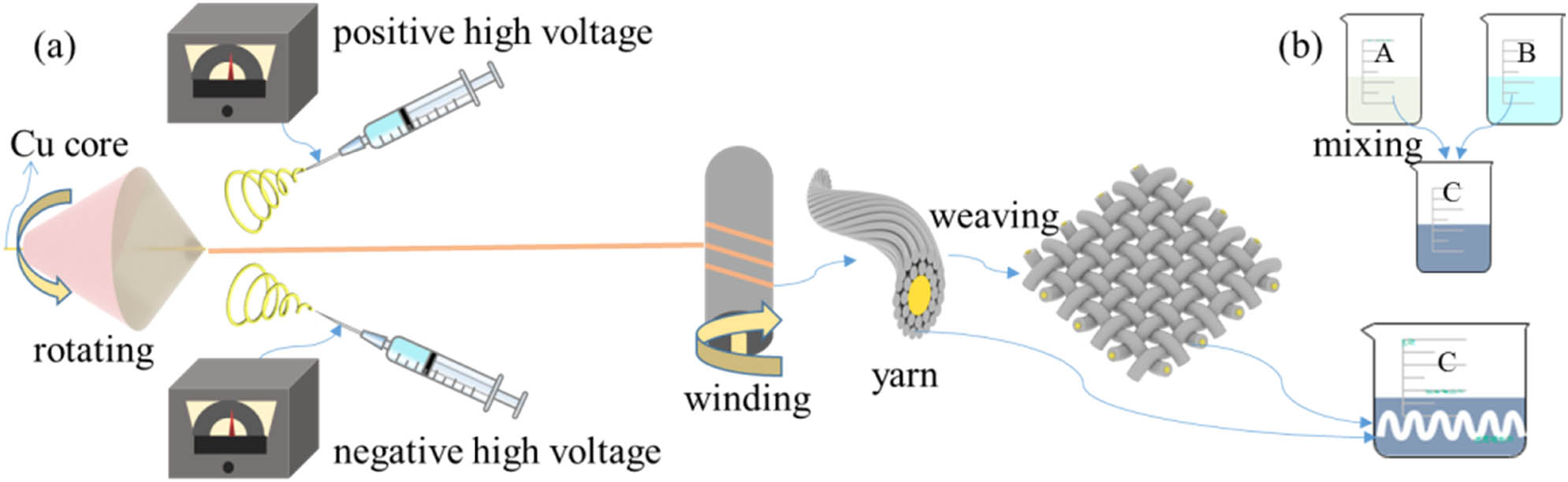

PVDF powders (FR903, Shanghai Sanaifu New Material Technology Co., Ltd., China) were dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide (analytical purity, Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China) at 20 wt% under 40°C water bath stirring for 4 h, and then stand for 24 h before electrospinning. During electrospinning process, an electrospinning apparatus (JDF05, Changsha Nayi Instrument Technology Co., Ltd, China) with a twisting module was used to achieve conjugate electrospinning (26,27,28). As suggested in Figure 1a, the prepared PVDF solution was loaded into a two 5 mL syringes with flat metal needles, and then connected to the positive and negative high voltage supply, respectively. The voltages were set at +6 and −6 kV. The feeding rate were 0.36 mL·h−1. The distance between the needles and the rotating funnel was 10 cm, and the funnel rotating speed was 200 rpm. The winding speed was 1 rpm. Cu wire with diameter 0.5 mm was used as the core of the spun yarn. Using a home-made paperboard loom, the obtained yarns could be weaved into a fabric.

(a) Diagram of the preparation of PVDF yarn and fabric and (b) the preparation of PANI solution and the preparation of PANI/PVDF yarn.

To modify the obtained yarn and fabric with PANI, two solutions A and B were prepared for in situ polymerization. Solution A contained 50 mL deionized water, 0.01 mol (2.542 g) sulfosalicylic acid (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China), and 0.02 mol (1.8626 g) aniline (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China); solution B contained 50 mL deionized water and 0.02 mol (4.564 g) ammonium persulfate (Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China). When the substances in solution A and solution B were fully dissolved forming a uniform and transparent solution, they were stored in the refrigerator at 5°C for 2 h. Then, the two solutions were mixed as soon as possible to make a solution C (29), as shown in Figure 1b. The prepared PVDF nanofiber yarn and fabric could be placed into solution C until complete immersion, and then stored in a refrigerator at 5°C for 12 h. Then, PANI could be polymerized onto the PVDF yarn and fabric. For later testing, the PANI-modified PVDF yarn and fabric was washed with deionized water for two to three times and then dried at 60°C for 8 h.

The morphology of prepared yarn and fabric was examined by a scanning electron microscopy (SEM; Phenom Pro, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at 10 kV after coating gold for 60 s. The chemical structures of the prepared samples were analyzed by a Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; Thermoscience Nicoletin 10, USA). The mechanical properties of prepared yarns (5 cm) and fabrics (2 cm × 2 cm) before and after polymerization were tested by universal tension machine (Instron 3352, US). The water contact angles of the fabrics before and after polymerization PANI were examined by an optical tensiometer (Attension Theta, Biolin Scientific, Germany) with 5 µL water drop. The prepared PANI/PVDF yarns and fabrics were put into the pH standard buffer (4.0, Leici, Shanghai Yidian Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., China), and diluted them continuously through the pipet to increase their pH ensuring that the pH increased by 1 every time until pH = 8. The open circuit voltage with time was measured by an electrochemical workstation (CHI 660e, Shanghai Chenhua Instrument Co., Ltd, China), using Ag/AgCl as reference electrode and Cu core as working electrode.

3 Results and discussion

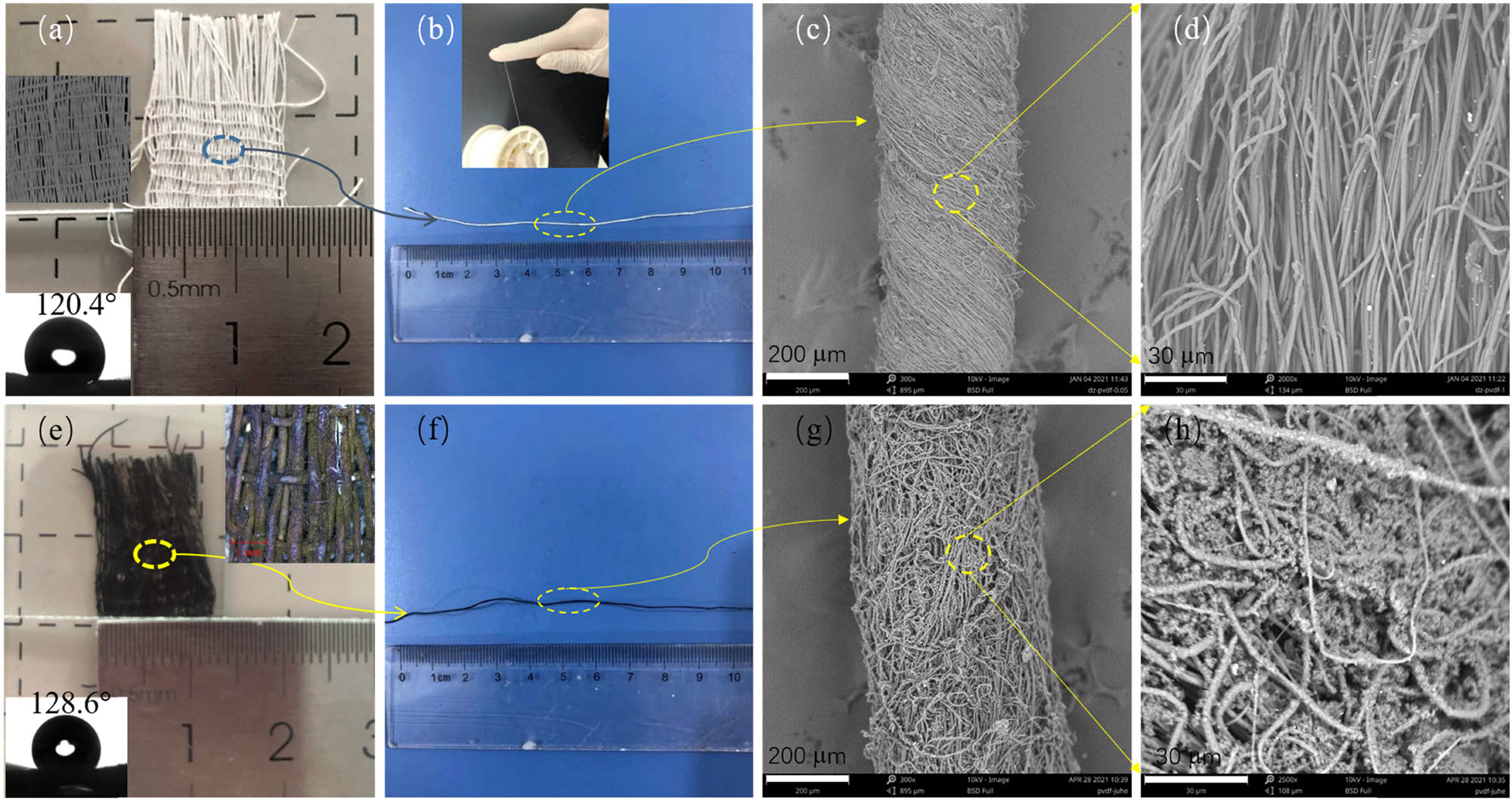

Figure 2 showed the morphologies of the prepared PVDF yarns and fabrics before and after PANI modification. From the comparison of Figure 2a, b, e and f, it could be found that there were obvious differences in color before and after PANI polymerization. The PVDF yarns and fabrics were white, whereas after in situ polymerization PANI modification, the fabrics and yarns were dark green. Through the SEM images in Figure 2c and d, it could be seen that the fibers in PVDF yarn were smooth, uniform, and arranged in a certain direction with a certain twist showing a compact yarn structure as a whole. After in situ polymerization of PANI, there were obvious PANI particles on the surface of yarn and fiber and the pores between fibers (Figure 2g and h). These PANI particles blurred the original clear yarn twist, which indicated that PANI had been successfully in situ polymerized onto PVDF yarns and fabrics. In addition, the diameter of the yarn before PANI modification was about 324 μm, and the average diameter of the fiber was 1.55 ± 0.61 μm. Although the modified yarn diameter was about 458 μm, and the average fiber diameter increased to 2.48 ± 0.98 μm. The increases of yarn and fiber diameter were also due to the adhesion of PANI particles to the surface of fiber and yarn. Moreover, the surface wettability of the fabrics before and after polymerized PANI was also examined. As suggested in the inset images in Figure 1a and e, the water contact angles were about 120.4° and 128.6° before and after coating PANI, respectively. These prepared PVDF fabrics were both hydrophobic, and the polymerization of PANI could enhance the hydrophobicity.

Optical images of (a) PVDF fabric and (b) yarn, (c and d) the SEM images the PVDF yarn, (e and f) the optical, and (g and h) the SEM images of PANI/PVDF fabric and yarn. Inset images in (a) and (e) were the contact angles of the fabrics.

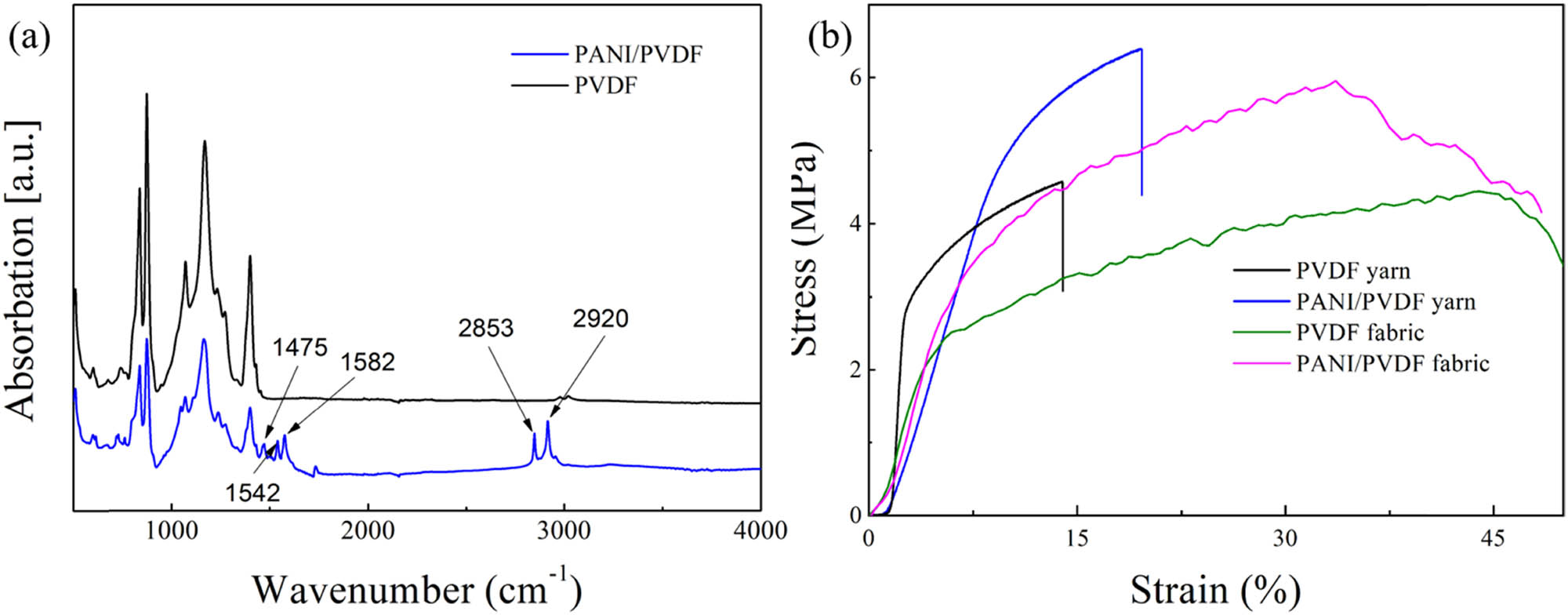

Figure 3a showed the FTIR spectrum of the yarn before and after polymerization. It could be seen that the yarn after modified by PANI had new absorption peaks at the wave numbers of 1,475, 1,542, 1,582, 2,853, and 2,920 cm−1. These absorption peaks correspond to the infrared absorption peaks of PANI (29). This also suggested that PANI was successfully polymerized onto a PVDF yarn.

(a) FTIR spectra and (b) stress–strain curve of the prepared PVDF and PANI/PVDF yarns and fabrics.

From the stress–strain curve in Figure 3b, it can be found that PANI attached to the PVDF yarn might significantly improve the tensile stress and strain of the yarn. Before PANI modification, the tensile strength of the yarn was 4.56 MPa, and the elongation was about 13.95%. After PANI modification, the tensile strength of the yarn increased to 6.39 MPa and the elongation increased to 19.62%. The improvement effect was 40.1% and 40.6%, respectively. Combined with the SEM images in Figure 2d and h, after PANI modification, a large number of PANI particles were attached to the yarn, fiber surface, and the gap between fibers. These particles improved the friction coefficient between fibers, so as to improve the tensile strength and elongation of the yarn. For the fabrics, due to the fabric structure, the elongation of the fabrics was greatly improved compared to the yarns. After coating with PANI, the tensile strength of the PANI/PVDF fabric was enhanced obviously, whereas the elongation of the PANI/PVDF fabric was reduced. It could be imagined that during the PANI in situ polymerization process of the fabric, PANI polymerized onto the yarn, and then enhanced the tensile strength, while for the connecting sites of the warp and weft yarns, less PANI polymerized here, and then under the high tensile force, the elongation was reduced.

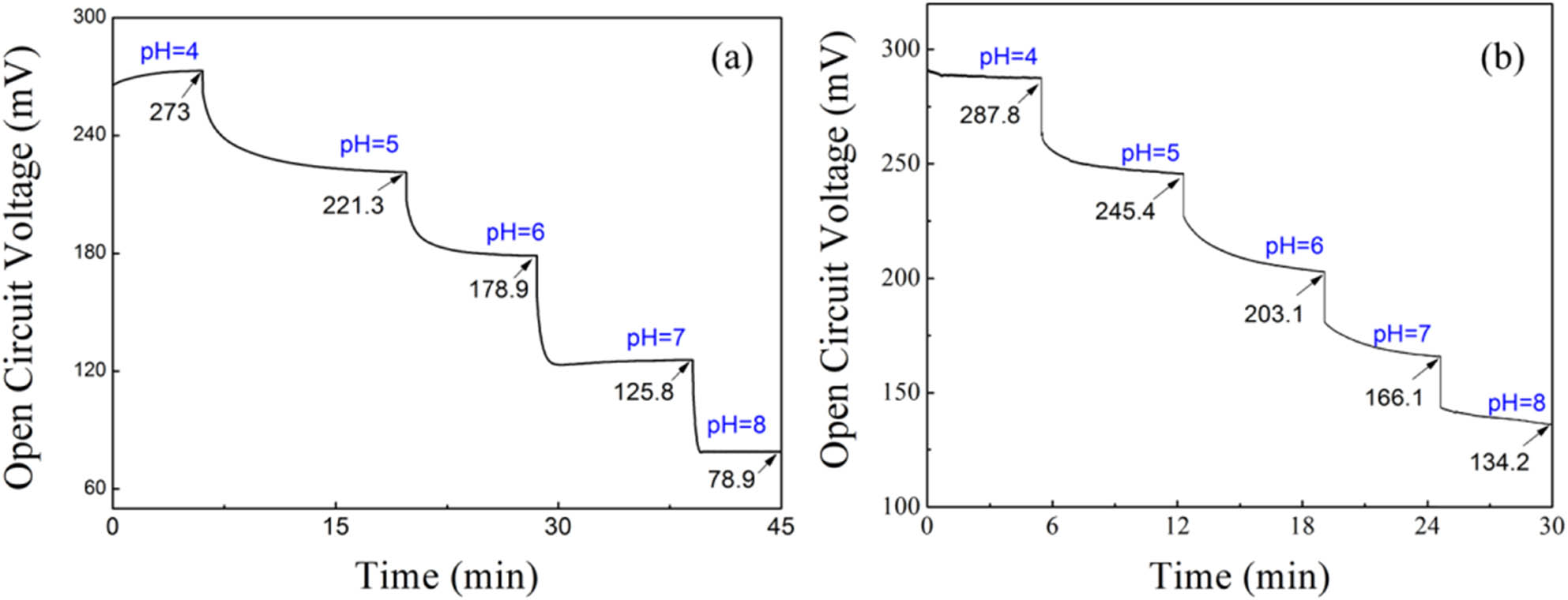

To investigate the pH sensitivity of the prepared PANI/PVDF yarn and fabric, the open circuit voltages in the range of pH = 4–8 were measured, as shown in Figure 4. It was suggested that the open circuit voltage of PANI/PVDF yarn decreased significantly with the increase of pH value, as displayed in Figure 4a. At pH 4, the open circuit voltage was 273 mV, whereas when pH increased to 8, the open circuit voltage decreased to 78.9 mV. The pH sensitivity was about −48.53 mV per pH. Moreover, with the increase of pH, the response of PANI/PVDF yarn to pH was increasingly faster, which was reflected in the increasingly shorter response time when pH changes. Especially, in the range of pH 6–8, the response sensitivity of PANI/PVDF yarn to pH was −50 mV per pH, and the response time was 30 s per pH.

The pH response of (a) PANI/PVDF yarn and (b) PANI/PVDF fabric in the pH range of 4–8.

For the PANI/PVDF fabric, the pH sensitivity was about −38.4 mV per pH in the pH range of 4–8 and −42.35 mV per pH in the pH range of 6–8, as indicated in Figure 4b. It seemed that the pH potential sensitivity of the PANI/PVDF fabric was lower than the yarn, which may result from the less PANI in the combining sites of the warp and weft yarns in the fabric. While the response time of the fabric was less than that of the yarn, which suggested the fabric may give a fast response to the pH change. These results demonstrated that the PANI-modified electrospun yarn as well as its fabric could be used as a flexible pH sensor.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, we fabricated PANI/PVDF yarn successfully by conjugate electrospinning process and in situ polymerization of PANI. The prepared yarn could be weaved into a fabric for smart dressing. The SEM and FTIR spectra showed that PANI particles were uniformly attached to the surface of the as-spun yarn. And after PANI modification, the tensile strength and elongation of the yarn could be improved up to 40%, which could meet the needs of weaving. In the range of pH 4.0–8.0, the PANI/PVDF yarn and fabric showed potential sensitivity to pH about 48.53 and 38.4 mV per pH, respectively. Specific in the pH range of 6.0–8.0, the sensitivity could be 50, and 42.35 mV per pH, which may be applied as oral and maxillofacial surgery smart dressing to monitor wound healing process.

-

Funding information: Qingdao Science and Technology Plan Special Project for Benefiting People Through Science and Technology (21-1-4-rkjk-20-nsh), Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (2020M671998), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51703102), and State Key Laboratory of Bio-Fibers and Eco-Textiles (Qingdao University) No. ZKT35.

-

Author contributions: Hongmei Zhao: investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, methodology, and formal analysis; Zhang Dai: data curation, formal analysis, methodology, and visualization; Tian He: formal analysis and data curation; Shufang Zhu: investigation and methodology; Xu Yan: project administration and resources; and Jianjun Yang: writing – review and editing, resources, supervision, and project administration.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

(1) Alam AU, Qin Y, Nambiar S, Yeow JTW, Howlader MMR, Hu NX, et al. Polymers and organic materials-based pH sensors for healthcare applications. Prog Mater Sci. 2018;96:174.10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018.03.008Search in Google Scholar

(2) Wencei D, Abel T, Mcdonagh C. Optical chemical pH sensors. Anal Chem. 2014;86:15.10.1021/ac4035168Search in Google Scholar

(3) Lindfors T, Ivaska A. pH sensitivity of polyaniline and its substituted derivatives. J Electroanal Chem. 2002;531:43.10.1016/S0022-0728(02)01005-7Search in Google Scholar

(4) Chen S, Jiang S, Jiang H. A review on conversion of crayfish-shell derivatives to functional materials and their environmental applications. J Bioresour Bioprod. 2020;5:238–47.10.1016/j.jobab.2020.10.002Search in Google Scholar

(5) Schneider LA, Grabbe AKS, Dissemond J. Influence of pH on wound-healing: a new perspective for wound-therapy. Arch Dermatol Res. 2007;298:413.10.1007/s00403-006-0713-xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

(6) Madni A, Kousar R, Naeem N, Wahid F. Recent advancements in applications of chitosan-based biomaterials for skin tissue engineering. J Bioresour Bioprod. 2021;6:11–25.10.1016/j.jobab.2021.01.002Search in Google Scholar

(7) Yan X, Yu M, Ramakrishna S, Russell S, Long Y. Advances in portable electrospinning devices for in situ delivery of personalized wound care. Nanoscale. 2019;11:19166–78.10.1039/C9NR02802ASearch in Google Scholar

(8) Dong W, Liu J, Mou X, Liu G, Huang X, Yan X, et al. Performance of polyvinyl pyrrolidone-isatis root antibacterial wound dressings produced in situ by handheld electrospinner. Colloid Surf B. 2020;188:110766.10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110766Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(9) Gethin G. The significance of surface pH in chronic wounds. Wounds UK. 2007;3:3.Search in Google Scholar

(10) Percival S, Mccarty S, Hunt J, Woods EJ. The effects of pH on wound healing, biofilms, and antimicrobial efficacy. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22(2):174.10.1111/wrr.12125Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(11) Qin M, Guo H, Dai Z, Yan X, Ning X. Advances in flexible and wearable pH sensors for wound healing monitoring. J Semicond. 2019;40(11):111607.10.1088/1674-4926/40/11/111607Search in Google Scholar

(12) Aframian DJ, Davidowitz T, Benoliel R. The distribution of oral mucosal pH values in healthy saliva secretors. Oral Dis. 2006;12:420–23.10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01217.xSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

(13) Bardow A, Pederson AML, Nauntofte B. Saliva. In: Miles TS, Nauntofte B, Svensson P, editors. Clinical oral physiology. Copenhagen: Quintessence; 2004. p. 17–18, 30–33.Search in Google Scholar

(14) Aframian D, Markitziu A. Oral manifestations of bulimia nervosa. Harefuah. 1999;136:537–40.Search in Google Scholar

(15) Guinovart T, Ramirez GV, Windmiller JR, Andrade FJ, Wang J. Bandage-based wearable potentiometric sensor for monitoring wound pH. Electroanalysis. 2014;26:1345.10.1002/elan.201300558Search in Google Scholar

(16) Rahimi R, Ochoa M, Parupudi T, Zhao X, Yazdi IK, Dokmeci MR, et al. A low-cost flexible pH sensor array for wound assessment. Sens Actuators B. 2016;229:609.10.1016/j.snb.2015.12.082Search in Google Scholar

(17) Punjiya M, Rezaei H, Zeeshan MA, Sonkusale S. A flexible pH sensing smart bandage with wireless cmos readout for chronic wound monitoring. In 19th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors Actuators and Microsystems (TRANSDUCERS); 2017. p. 1700.10.1109/TRANSDUCERS.2017.7994393Search in Google Scholar

(18) Lyu B, Punjiya M, Matharu Z, Sonkusale S. An improved pH mapping bandage with thread-based sensors for chronic wound monitoring. In IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS); 2018. p. 1–4.10.1109/ISCAS.2018.8351878Search in Google Scholar

(19) Steyaert, I, Rahier, H, Clerck, KD. Nanofibre-based sensors for visual and optical monitoring. Electrospinning for High performance sensors. nanoscience and technology. Cham: Springer; 2015.10.1007/978-3-319-14406-1_7Search in Google Scholar

(20) Zhao LY, Duan GG, Zhang GY, Yang H, Jiang S. Electrospun functional materials toward food packaging applications: a review. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(1):150.10.3390/nano10010150Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(21) Agarwal A, Raheja A, Natarajan TS, Chandra TS. Development of universal pH sensing electrospun nanofibers. Sens Actuators B. 2012;161:1097.10.1016/j.snb.2011.12.027Search in Google Scholar

(22) Schoolaert E, Steyaert I, Vancoillie G, Geltmeyer J, Lava K, Hoogenboom R, et al. Blend electrospinning of dye-functionalized chitosan and poly(ε-caprolactone): towards biocompatible pH-sensors. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4:4507.10.1039/C6TB00639FSearch in Google Scholar

(23) Pan N, Qin J, Feng P, Li Z, Song B. Color-changing smart fibrous materials for naked eye real-time monitoring of wound pH. J Mater Chem B. 2019;7:2626.10.1039/C9TB00195FSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

(24) Liu L, Xu W, Ding Y, Agarwal S, Greiner A, Duan G. A review of smart electrospun fibers toward textiles. Compos Commun. 2020;22:100506.10.1016/j.coco.2020.100506Search in Google Scholar

(25) Wei DW, Wei H, Gauthier AC, Song J, Jin Y, Xiao H. Superhydrophobic modification of cellulose and cotton textiles: Methodologies and applications. J Bioresour Bioprod. 2020;5:1–15.10.1016/j.jobab.2020.03.001Search in Google Scholar

(26) Dai Z, Yan FF, Qin M, Yan X. Fabrication of flexible SiO2 nanofibrous yarn via a conjugate electrospinning process. e-Polymers. 2020;20:600–5.10.1515/epoly-2020-0063Search in Google Scholar

(27) Dai Z, Wang N, Yu Y, Lu Y, Jiang L, Zhang DA, et al. One-step preparation of a core-Spun Cu/P(VDF-TrFE) nanofibrous yarn for wearable smart textile to monitor human movement. ACS Appli Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(37):44234–242.10.1021/acsami.1c10366Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(28) Jian S, Tian Z, Hu J, Zhang K, Zhang L, Duan G, et al. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic efficiency of la-doped ZnO nanofibers via electrospinning-calcination technology. Adv Powder Mater. 2021. 10.1016/j.apmate.2021.09.004.Search in Google Scholar

(29) He HW, Zhang B, Yan X, Dong RH, Jia XS, Yu GF, et al. Solvent-free thermocuring electrospinning to fabricate ultrathin polyurethane fibers with high conductivity by in situ polymerization of polyaniline. RSC Adv. 2016;6:106945.10.1039/C6RA21882BSearch in Google Scholar

© 2022 Hongmei Zhao et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes