Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

-

Wern Ming Che

, Cheow Keat Yeoh

Abstract

Natural rubber latex/graphene nanoplatelet (NRL/GNP) composites containing GNP-pristine and GNP–SDS were prepared by a simple mechanical mixing method. The main objective was to study the effect of dispersibility of GNP on the properties in NRL. X-ray diffraction confirmed the adsorption of sodium sulfate dodecyl (SDS) on the GNP surface. The results showed that high filler loading diminished the physical and mechanical properties of the composites but successfully endured to satisfy electrical conductivity to the NRL/GNP composites. Besides, the SDS surfactant-filled system demonstrated better physical, tensile, electrical, and thermal stability properties than the GNP-pristine. The intercalated and dispersed GNP–SDS increased the number of routes for stress and heat transfer to occur and facilitated the formation of conductive pathways as well, leading to the improvement of the properties as compared to NRL/GNP-pristine composites. However, as the GNP–SDS loading exceeded 5 phr, the GNP–SDS localized in the interstitial layer of NRL, restricted the formation of crosslinking, and interfered with the strain-induced crystallization ability of the composites.

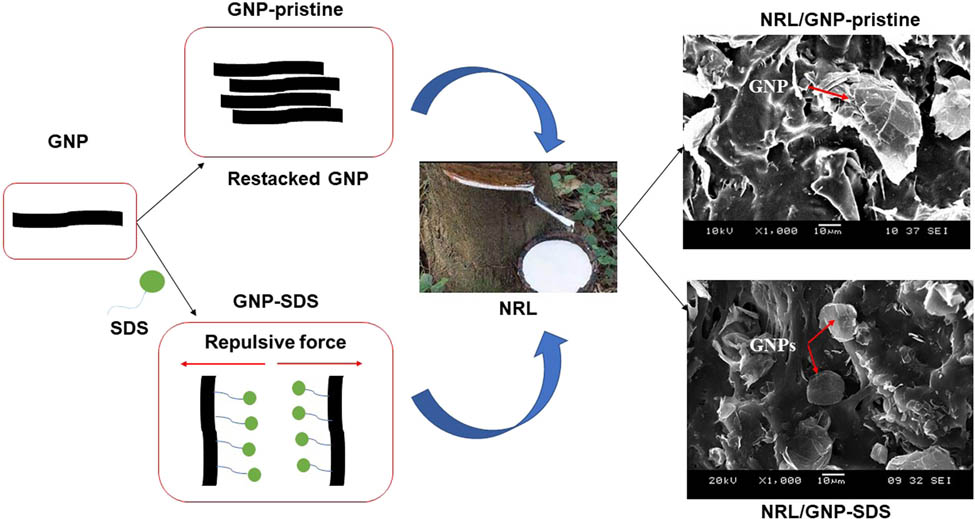

Graphical abstract

The effect of SDS in NRL/GNP–SDS composites.

1 Introduction

Natural rubber latex (NRL) is the colloidal suspension of the poly(cis-1,4-isoprene) within water together with the non-rubber substances to form a milky liquid. NRL acts as a good candidate to be used in various applications since it is obtained from natural resources, which is renewable, environmentally friendly, low cost, and possesses high elasticity properties. The properties of NRL products are tailorable by compounding the NRL with different types and amounts of additives based on the requirement of the end-use application (1). The high elasticity of NRL combined with these attractive properties enable it to be used as a wearable product. However, the application of the unfilled NRL was limited due to its low mechanical properties and inherently insulating characteristics.

To overcome the weaknesses of the NRL, carbonaceous filler such as graphene nanoplatelet (GNP) could be incorporated into the NRL matrix for the purpose of improvement of mechanical and electrical conductivity properties or even to endow some new characteristics for the composite. GNP possesses large surface area, exceptional Young’s modulus, high electron mobility, good barrier properties, and many other attractive properties (2). The properties of the composites depend on the matrix–filler interfacial interaction and the dispersibility of filler within the matrix (3). Nevertheless, the high surface area and high cohesive force in between the GNP sheets and their hydrophobic nature have led to the agglomeration issue, which tends to deteriorate the properties of the composite materials (4). Thus, repulsive force is required to be introduced on the individual GNP to improve the dispersibility of the GNP, especially to be dispersed in water medium of the NRL matrix.

Sodium sulfate dodecyl (SDS) is an anionic surfactant which consists of a hydrophobic hydrocarbon tail and a hydrophilic sulfate head. Hsieh and coworkers had demonstrated an adsorption model to explain the adsorption behavior of SDS at different concentrations. According to their findings, the alkyl chains of the SDS were adsorbed on the graphene surface while the anionic head formed micelle once and formed micelle once the critical micelle concentration is achieved to induce electrostatic force for intercalation and exfoliation of the GNP sheets (5). Besides, the SDS also acts as a “bridge” between the incompatible GNP and NRL matrix to improve the interfacial interaction through its amphiphilic characteristics. Also, the improved dispersibility of GNP within the matrix facilitated the construction of the conductive pathway due to the increment of the surface area of the intercalated and exfoliated GNP (6). This corresponded to the findings of Lin and coworkers who found that the SDS improved the electrical conductivity and thermal stability of the polyaniline/graphene due to the improvement of matrix–filler interaction and dispersion (7).

Herein, a simple mechanical and ultrasonic mixing system was used to establish the effect of GNP dispersibility on the tensile, crosslink density, electrical conductivity, and thermal properties of NRL/GNP composites. Both NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS composites are compared in this article. This stretchable conductive composite can be used for wearable applications such as smart watches to monitor the body temperature and pulse sensor.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

NRL with 60% of dry rubber content was supplied by MG Color Sdn. Bhd. The 50% dispersive compounding additives such as zinc oxide (ZnO), sulfur (S), zinc diethyldithiocarbamate (ZDEC), and zinc 2-mercaptobenzothiazole (ZMBT) were purchased from Farben Technique (M) Sdn. Bhd. Furthermore, stearic acid (SA) was supplied by Acidchem International Sdn. Bhd, while the stabilizer potassium hydroxide (KOH) was purchased from Johchem Scientific & Instruments Sdn. Bhd. Moreover, GNP (0540DX) was purchased from SkySpring Nanomaterials Inc., USA, and SDS was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation.

2.2 Sample preparation

The NRL/GNP composites were fabricated according to the formulation shown in Table 1. NRL was stirred with the compounding additives for overnight using magnetic stirrer after 1 h of sonication. After 24 h stirring, the mixture was filtered and casted on a glass mold. The casted NRL/UVSR composites were allowed to cure at room temperature for 72 h. Then, the sample was put in an oven to undergo post-curing at 70°C for 24 h. These preparation steps were replicated with different GNP species (GNP-pristine and GNP–SDS) and GNP loadings (0, 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 phr) to investigate the effect of matrix–filler interaction and filler loading on the physical, mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of the NRL/GNP composites.

Formulation for sample preparation

| Ingredients | NRL | KOH | ZnO | SA | ZMBT | ZDEC | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount (phr) | 100.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.0 |

2.3 Characterization

2.3.1 Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

The filler–matrix reaction was analyzed using Perkin Elmer Spectrum RX 1, FTIR spectrometer.

2.3.2 X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The intercalation and dispersion of the filler within the matrix was investigated using Shimadzu X-ray Diffractometer XRD-6000 with Cu-Kα with an angle from 10° to 40° and a scan rate of 5°·min−1.

2.3.3 Crosslink density

The crosslink density was determined by immersing the weighed samples (0.2 g) into toluene until the sample weight reached equilibrium. Then, the crosslink density of the composites was calculated using the Flory–Rehner equation shown as Eq. 1 and the swelling percentage was calculated using Eq. 2:

where v is the effective number of moles of crosslinked chains per gram of polymer in mol·g−1, M cs is the molecular weight between crosslink in g·mol−1, V 2 is the volume fraction of polymer in the swollen mass, V 1 is the molar volume of the solvent in mL·mol−1, χ is the polymer–solvent interaction parameter, ρ 2 is the density of the polymer in g·cm−3, and m s is the sample swollen mass while m d is the dry mass of the sample in g.

2.3.4 Tensile test

Tensile properties were determined using Instron 5569 Universal Testing Machines according to the ASTM D412 with a crosshead speed of 500 mm·min−1.

2.3.5 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The tensile fracture surface was observed by SEM, JEOL JSM-6460 LA after coating with a thin layer of palladiums.

2.3.6 Electrical conductivity

The electrical conductivity test was tested on the sample with a diameter of 1 cm2 according to the ASTM D257 using the Fluke 8845A/8846A 6.5-digit precision multimeter in direct current mode with a voltage supply of 5 V at room temperature. The bulk resistivity and bulk conductivity were calculated according to Eqs. 3 and 4, respectively:

where r is the resistance of resistor, A is the area of the specimens in cm2, and d is for the thickness of the specimens in cm.

2.3.7 Thermal stability

The thermal stability of the samples was tested using the TGA, Perkin Elmer Instruments with a heating rate of 10°C·min−1 from temperature 25°C to 800°C and the result was shown in weight loss versus temperature curve.

3 Results and discussion

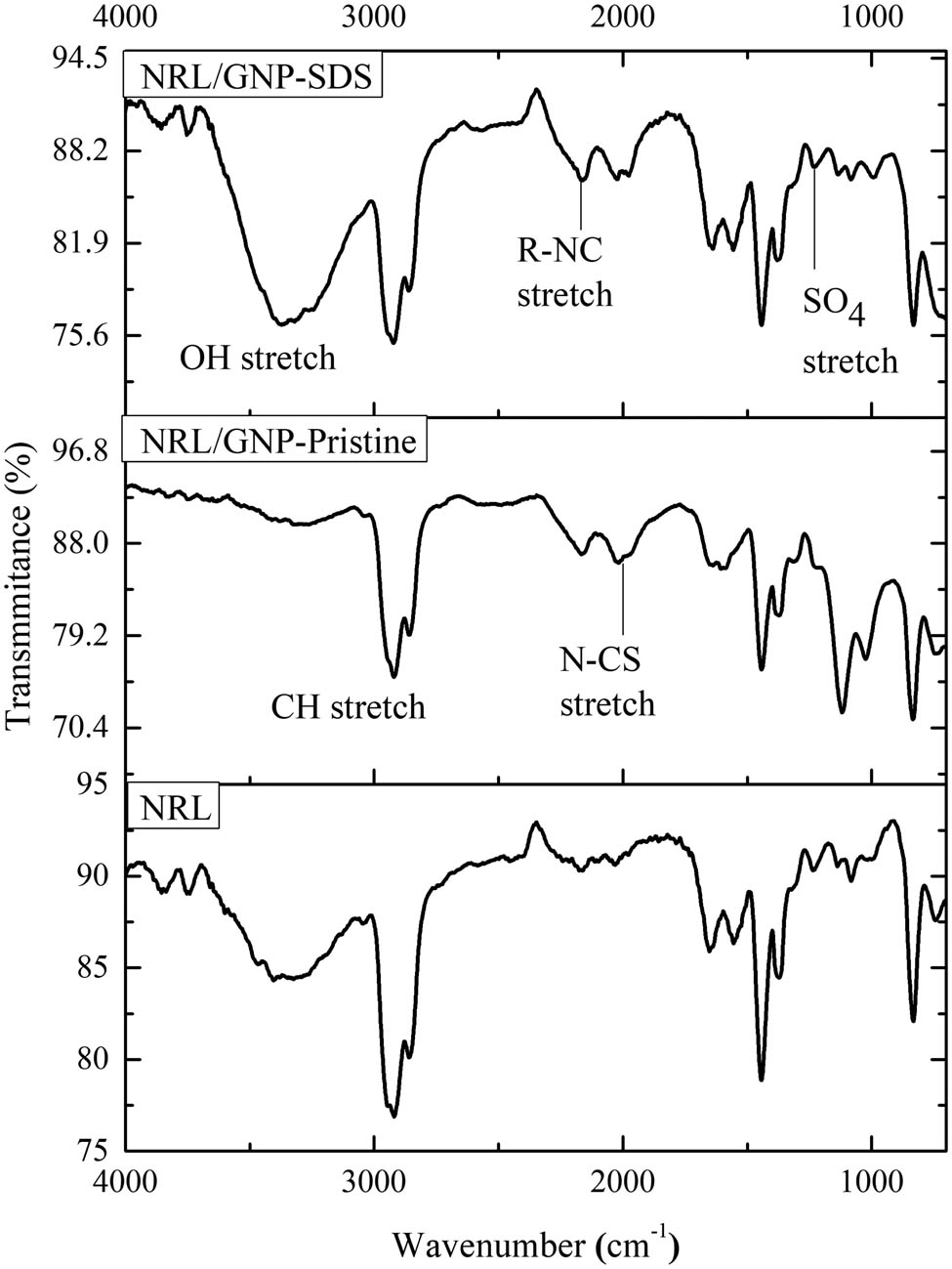

3.1 FTIR analysis

FTIR was employed to study the interaction between the SDS with GNP and NRL. The FTIR spectra of the NRL and NRL composites loaded with GNP-pristine and GNP–SDS are shown in Figure 1. The bands around 740, 832, 1,082, and 1,235 cm−1 are attributed to the C–H bend of the NRL. The peaks around 1,371 and 1,443 cm−1 are corresponding to the CH2 and CH3 bending of the NRL, respectively (8). The band at 1,555 cm−1 is attributed to the C–O stretching of the SA additives, while the absorption peak of C═C unsaturated backbone of NRL is detected at 1,651 cm−1. Besides, the peaks at 2,030, 2,161, and 2,566 cm−1 are related to the isothiocyanide stretching and S–H mercaptans of the accelerator. Furthermore, the asymmetric stretching of the CH2 group of SDS was detected at 2,858 cm−1. On the other hand, there was only one band observed to be different from the NRL/GNP–SDS composites which appeared around 1,135 cm−1. This band was reported as the characteristic band of S–O stretching in the structure of the SDS sulfate group (9). The FTIR result concludes that there was no chemical reaction occurring between the SDS, GNP, and NRL matrix since there was no new peak observed among the three components.

FTIR spectra of NRL, NRL/GNP-pristine, and NRL/GNP–SDS at 3 phr of GNP loading.

3.2 XRD analysis

Figure 2 and Table 2 show the XRD spectrums, 2 theta angles and d-spacing of GNP-pristine, GNP–SDS, NRL, and both NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS at 1 and 7 phr of GNP loadings. The wide and broad characteristic peaks located around 2Ɵ = 18° are attributed to the diffraction of amorphous NRL matrix. Then, the characteristic peaks in the range of 32–37° are attributed to the ZnO and SA added during compounding of NRL matrix (10). Besides, it can be noted that the GNP-pristine exhibits a higher intensity characteristic peak as against to GNP–SDS, indicating the retention of organized layered structure. The increment of interlayer spacing of GNP–SDS indicates the successful adsorption of SDS on the GNP surface (11).

XRD diffraction of (a) NRL, (b) GNP–SDS, (c) GNP-pristine, (d) NRL/GNP-pristine-1 phr, (e) NRL/GNP-pristine-7 phr, (f) NRL/GNP–SDS-1 phr, and (g) NRL/GNP–SDS-7 phr.

The 2Ɵ and d-spacing of unfilled NRL and selected NRL composites filled with 1 and 7 phr of GNP-pristine and GNP–SDS

| Samples | 2Ө (°) | d-spacing (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNP-pristine | 27 | 0.335 | |

| GNP–SDS | 26 | 0.339 | |

| NRL/GNP-pristine | 1 phr | 25 | 0.361 |

| 7 phr | 27 | 0.332 | |

| NRL/GNP–SDSGNP–SDS | 1 phr | 24 | 0.364 |

| 7 phr | 27 | 0.332 | |

It can be noticed that the diffraction peak of the NRL composites with loading of 1 phr has shifted to smaller diffraction angle and almost no sign of GNP reflection peak observed at around 2Ɵ = 24–26° within the diffractogram. In other words, the GNP nanofiller can disperse well within the NRL matrix at low filler loading. Moreover, the interlayer spacing of both NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS at 1 phr owned an interlayer distance which is larger than the pure filler. This stipulates that the NRL matrix has intercalated into the GNP gallery (12). However, credited to the adsorption of the SDS on the GNP surface, the larger graphene–graphene interlayer distance of the GNP–SDS allowed the intercalation of matrix to occur more readily than the GNP-pristine and hence, the NRL/GNP–SDS exhibited a larger d-spacing than the NRL/GNP-pristine composite.

In contrast, comparing between the NRL/GNP–SDS and NRL/GNP-pristine with 7 phr loading, the Bragg peak of the NRL/GNP-pristine reveals a more intense and larger 2Ɵ value, representing that the GNP-pristine restacked in a more orderly and packed layered structure as compared to the NRL/GNP–SDS (13). This is supported by the decrement of interlayer spacing of NRL/GNP-pristine as opposed to NRL/GNP–SDS at 7 phr. Hence, the treatment by SDS on the GNP successfully increased the interlayer spacing of the GNP nanofiller for ready intercalation of matrix into the GNP gallery and improved the dispersibility of the GNP nanofiller, which can be proven by the improvement of tensile properties of the composites.

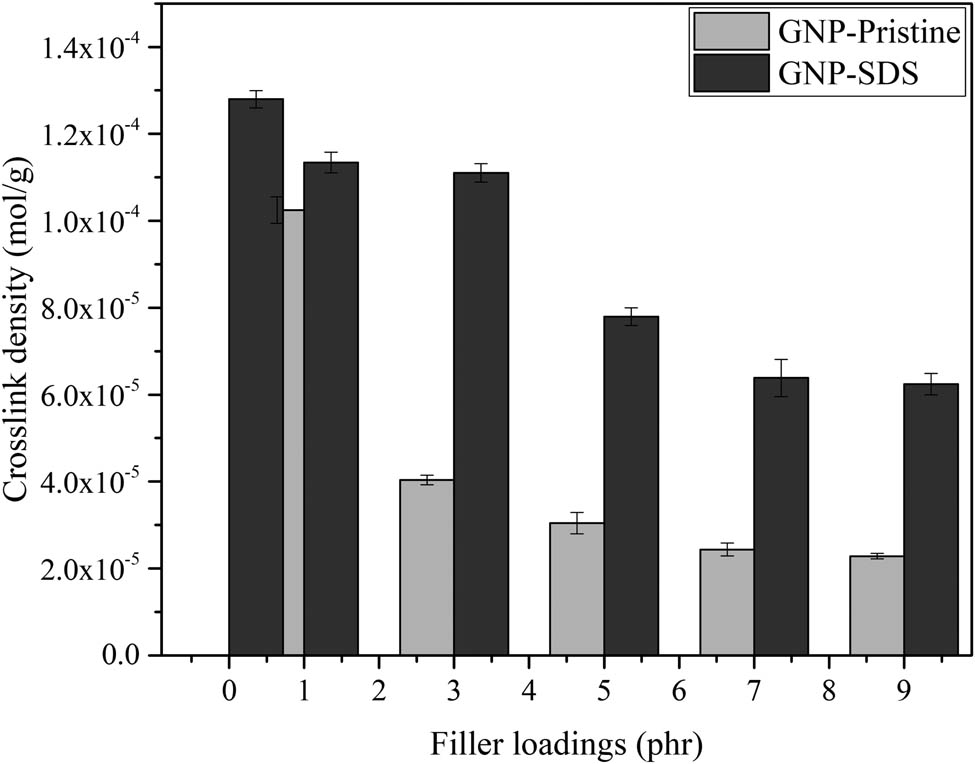

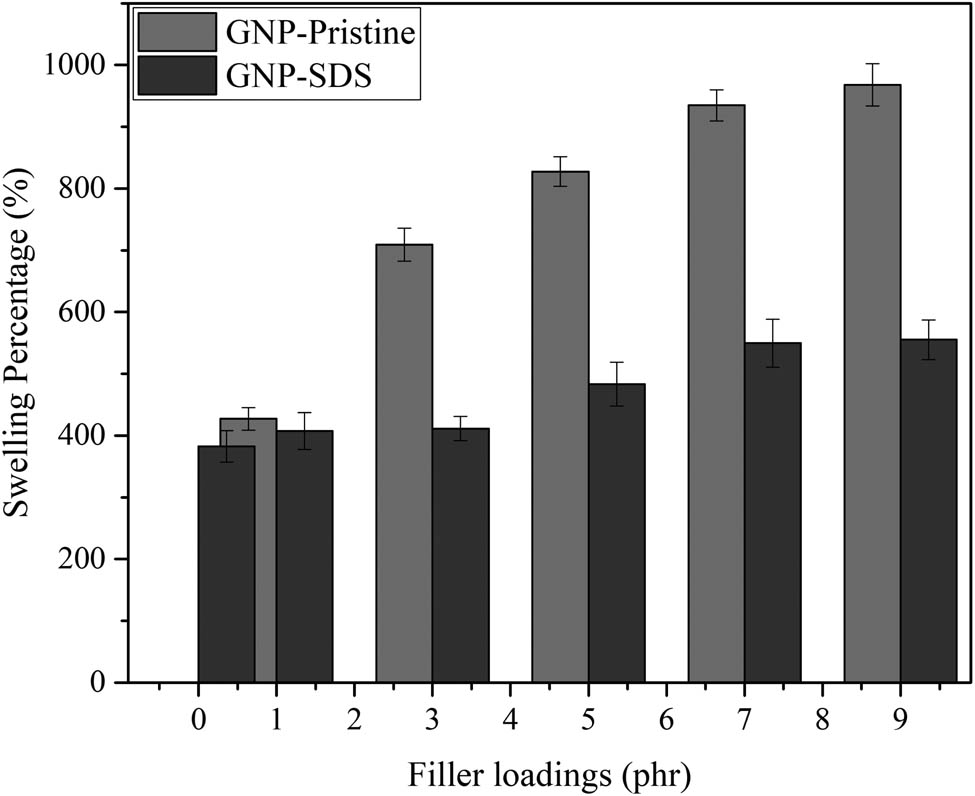

3.3 Crosslink density

Figures 3 and 4 show the crosslink density and swelling percentage of the composites prepared from GNP-pristine and GNP–SDS, respectively, with varying loadings. All the filled composites exhibited lower crosslink density compared to unfilled NRL. Despite there being some rubber particles that have penetrated in between the GNP layer, GNPs also have penetrated in between the NRL chains. The NRL chains unable to approach each other with the existence of the GNP particles and the reactive sites along the macromolecular chains could cover by the GNP as well, which in turn obstructed the formation of crosslink per chain, thus reducing the crosslink density. This was confirmed by the findings of Wang and coworkers who realized that the crosslinking of the polydimethylsiloxane was hindered by the graphene aerosol (14).

Crosslink density of NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS with increasing GNP loadings.

Swelling percentage of NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS with increasing GNP loadings.

Furthermore, the crosslink density was inversely proportional to the swelling percentage. The significant reduction of the crosslink density in the NRL/GNP-pristine composites was due to the nature of GNP which tends to form aggregates between the interparticles and cause poor dispersion of the GNP within the NRL matrix. For the NRL/GNP–SDS composites, the intercalated GNP–SDS sheets exhibited higher surface area. This attributed to the improvement of interfacial interaction between GNP–SDS and NRL, leading to the increment of contact within the composites. Furthermore, the dispersed GNP–SDS sheets have constructed tortuous paths for the toluene to diffuse through the composites and thus possess lower swelling percentage (15).

However, as the filler loading increased, the bulk volume of the matrix for both the GNP–SDS and GNP-pristine to be dispersed was reduced. Also, the GNP sheets had a higher tendency to form aggregate with each other as GNP loading increased. The GNP sheets started to restack through van der Waals force (16). The agglomerated GNP tends to increase the chain distance of the NR chains which in turn reduced the crosslink density (17). Thus, the NRL/GNP–SDS endowed higher crosslink density and better solvent resistance as compared to the NRL/GNP-pristine composites but these properties reduced as GNP loading increased.

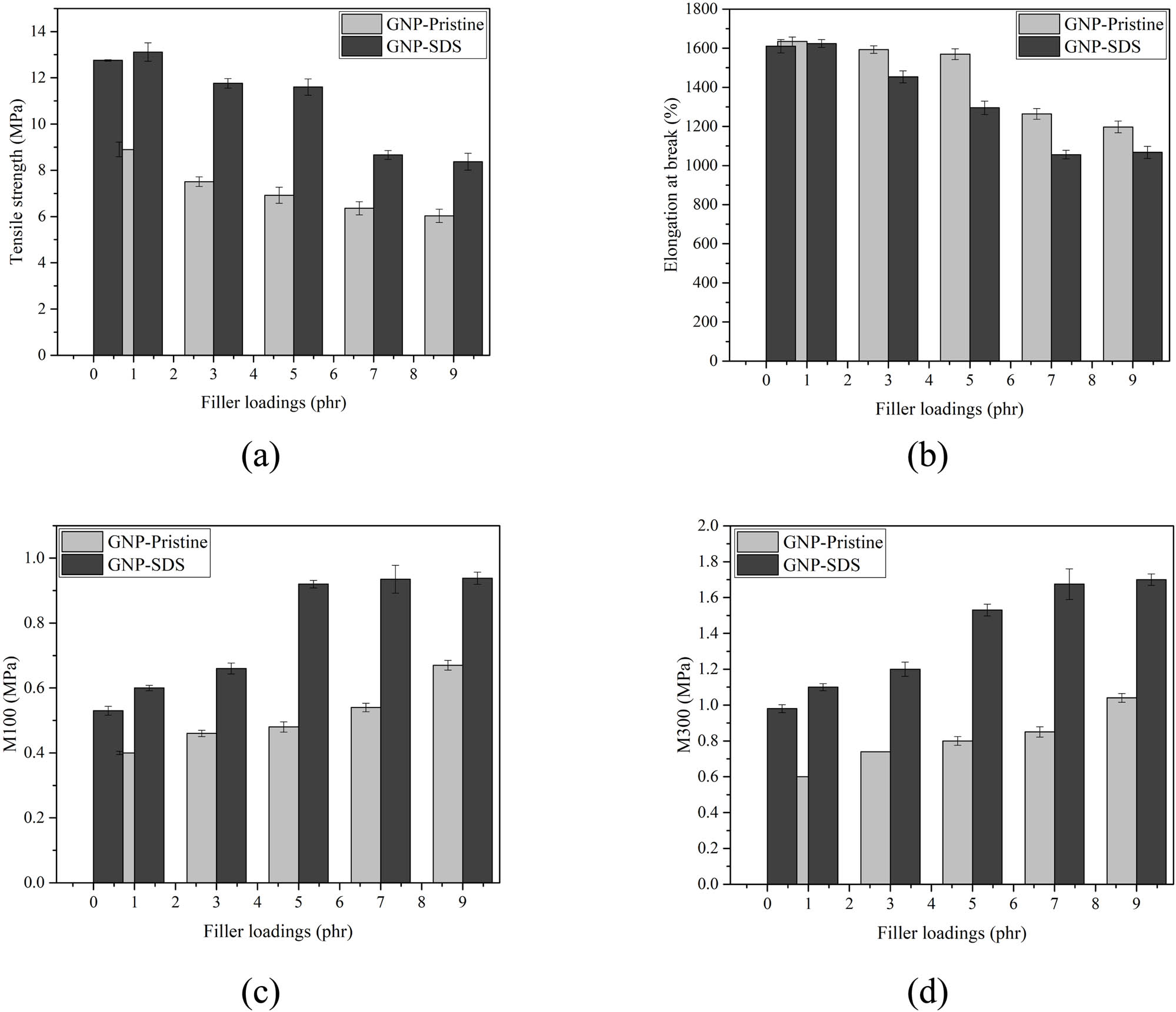

3.4 Tensile test

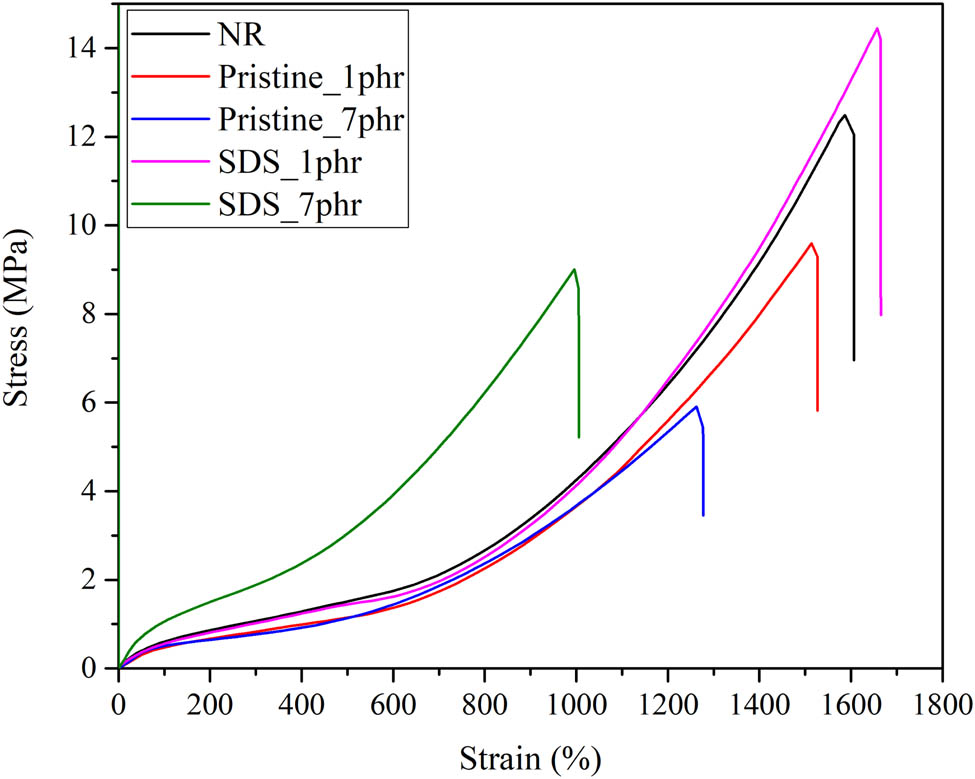

Figure 5 shows the stress–strain curve for neat NRL, NRL/GNP-pristine, and NRL/GNP–SDS loaded at 1 and 7 phr, respectively. All the specimens demonstrated a non-linear behavior and the stress raised continuously with strain. The sudden surge of the curve after 400% strain indicates the occurrence of strain-induced crystallization (SIC) throughout the rapid stretching. The tensile strength, elongation at break, and modulus at 100% and 300% elongation are displayed in Figure 6. The tensile strength of the NRL/GNP-pristine dropped continuously with the increase in filler loading while the NRL/GNP–SDS composites show an increasing trend at 1 phr but then reduced at further increment of loading. Besides for the reduction of crosslink density as discussed above, the mechanical properties can be affected by SIC ability of the composites.

Stress–strain curve of neat NRL, NRL/GNP-pristine, and NRL/GNP–SDS at 1 and 7 phr.

Tensile properties: (a) tensile strength, (b) elongation at break, (c) M100, and (d) M300 of NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS with increasing loadings.

The localization of the GNP in the interstitial area of the matrix could restrain the chain mobility during uniaxial stress applied. The NRL chains are unable to align along the stretch direction and constrained the crystal growth in the confined volume within the matrix, leading to the reduction of SIC ability of the composite which is liable for the high strength of the NR. The reduction of crosslink density and SIC ability caused the reduction of tensile strength and elongation at high GNP loading (18). Alternatively, the improvement of strength for NRL/GNP–SDS at 1 phr is contributed to the adsorption of SDS on the GNP sheets which was able to induce the repulsive force in between the adjacent GNP and prevent the restacking of the GNP (7). Nevertheless, the tensile strength of the NRL/GNP–SDS at 1 phr was lower than the similar composites prepared by La and coworkers, which showed a strength around 17 MPa at the same loading (19). This discrepancy could ascribe that different fabrication methods resulted in different filler dispersions. The processing method of using simple mechanical stirring is unable to disperse the GNP filler evenly as compared to the fabrication method that La and coworkers used.

Besides, the van der Waals attraction force of the GNP–SDS was high enough to overcome the repulsive force at high filler loading to form agglomerate and diminished the tensile strength of the resulting composite. On the other hand, the composites show an improvement of elongation at break at low filler loading. At lower loading, when the content of GNP is lower, the matrix has more free volume in between the rubber chain and thus leads to a more flexible composite (20). However, as the GNP loading increased, more GNP particles existed to hold the chains during the tensile stress applied, and it reduced the chain mobility and flexibility of the composites but improved the modulus at high GNP loading when tensile force was applied (21).

It can be noticed that the NRL/GNP–SDS composites were stronger than the NRL/GNP-pristine. This can be attributed to the improved interfacial interaction between the filler and matrix. The dispersed GNP–SDS possessed a higher contact area to be interacted with the NRL matrix. This provides more routes for the stress transfer from the matrix to the GNP to occur more efficiently, and therefore offer higher tensile strength for the NRL/GNP–SDS composites (22). Besides, the existence of higher physical interaction between the filler–filler and matrix–filler together with the chemical crosslink of matrix–matrix, the chains were held more tightly as compared to pristine GNP and thus required more force to elongate the chain and initiate deformation for the sample (23). Thus, the GNP–SDS possessed lower elongation at break and higher modulus as GNP loading increased. As a result, the better dispersion of GNP–SDS within the NRL matrix promoted a better filler–matrix interfacial interaction physically, leading to a higher tensile strength and modulus but lower elongation at break as compared to the NRL/GNP-pristine composites.

3.5 Morphology

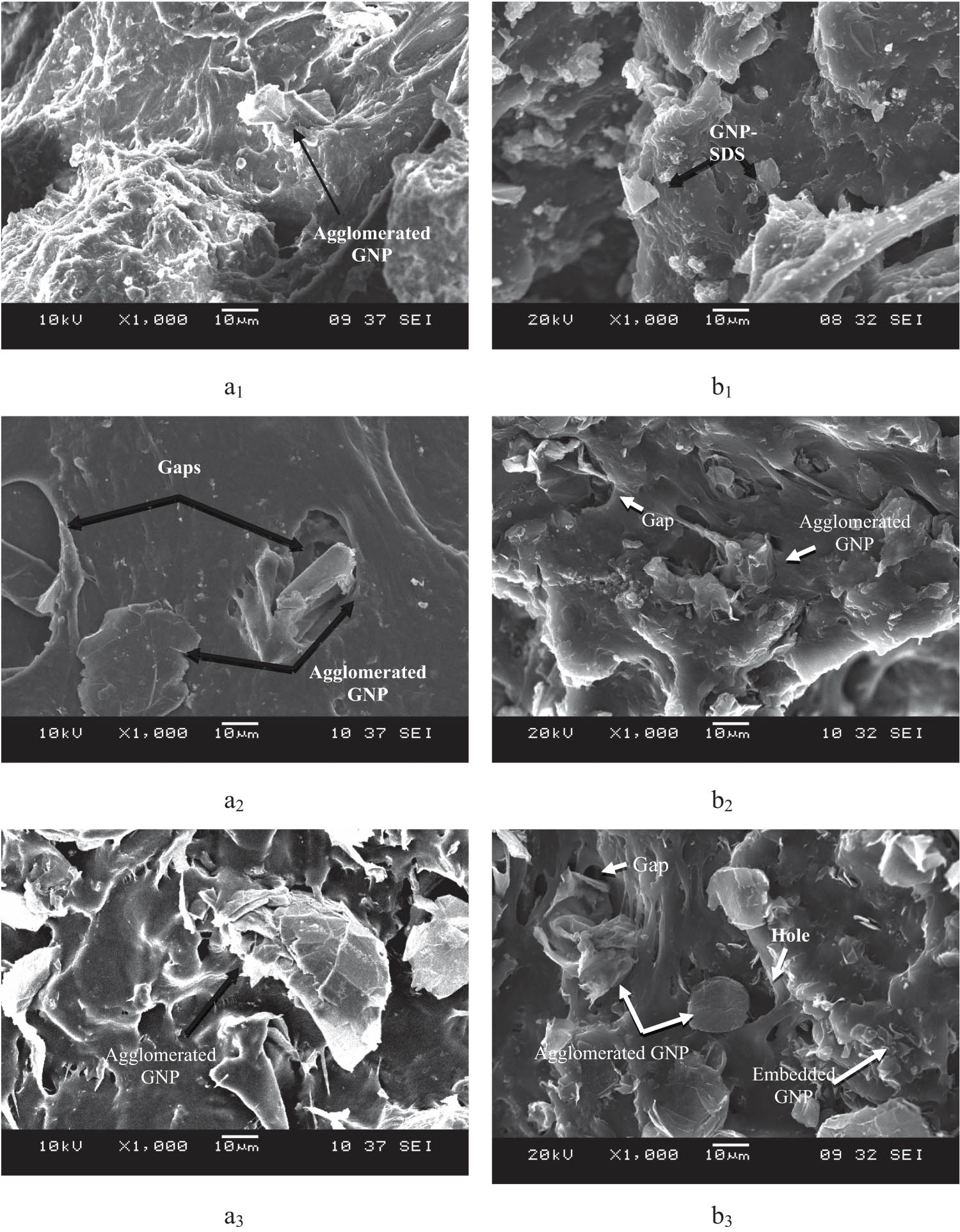

Figure 7 shows the tensile fractured surface of the composites prepared from both GNP-pristine and GNP–SDS, respectively, at 1, 3, and 9 phr of GNP loadings. From the figures, it can be seen that GNP–SDS shows better interfacial adhesion with matrix since most of the GNP sheets were embedded in the matrix. This could be attributed to the reduction of surface energy of the blend components contributing to the amphipathic nature of the SDS (3). Nevertheless, there were still some GNPs detached from the NRL–GNP–SDS interface. This denoted that the matrix–filler interfacial interaction was still not being optimized even though the GNP surface was adsorbed with surfactant.

SEM micrographs of the tensile fracture surface of (a) NRL/GNP-pristine and (b) NRL/GNP–SDS composites at: (1) 1 phr, (2) 3 phr, and (3) 9 phr of GNP loadings, respectively.

Besides the GNP–SDS was dispersed better than the GNP-pristine. The GNP–SDS can be found throughout the fracture surface and form small cluster at high loading. While for the NRL/GNP-pristine composite, the GNP-pristine agglomerated and concentrated at certain region. In addition, the size of the agglomerated GNP-pristine was larger than the GNP–SDS. This indicated that the adsorbed SDS molecules help to improve the filler dispersion and prevent the large agglomeration, which can be supported by the improvement of tensile properties.

Furthermore, there were gaps found around the filler particles after pulling action. According to Mphahlele et al., failure of a composite initiated at the weakest point of the composite (24). The matrix–filler interface was too weak and tends to detach under force and even leave a large hole as the GNP particles had been pulled out as shown in Figure 6b3 . Moreover, the interfacial shear stress induced due to the elongation mismatch between the flexible matrix and high modulus GNP also caused the deformation to initiate at the interface (23).

Although the interfacial interaction between GNP–SDS and NRL has improved, the weak physical interaction was not strong enough to withstand higher tensile load when it was applied. However, the NRL/GNP–SDS shows higher tensile strength as compared to that of GNP-pristine. This contributed to the better dispersion of GNP–SDS, which offers higher surface area for the interfacial interaction between the matrix and filler to occur. Both the NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS composites tend to restack and agglomerate at higher GNP loading, which is at 9 phr of GNP. These agglomerated GNPs acted as the stress concentration point, leading to the decrement of mechanical properties of the composites at high filler loading.

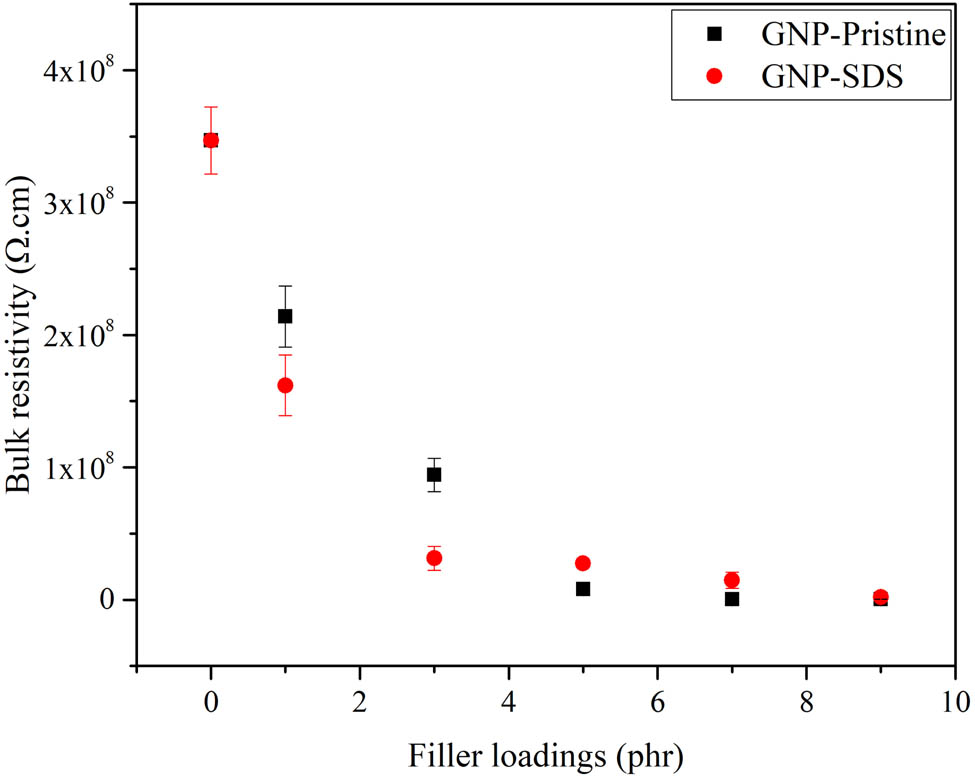

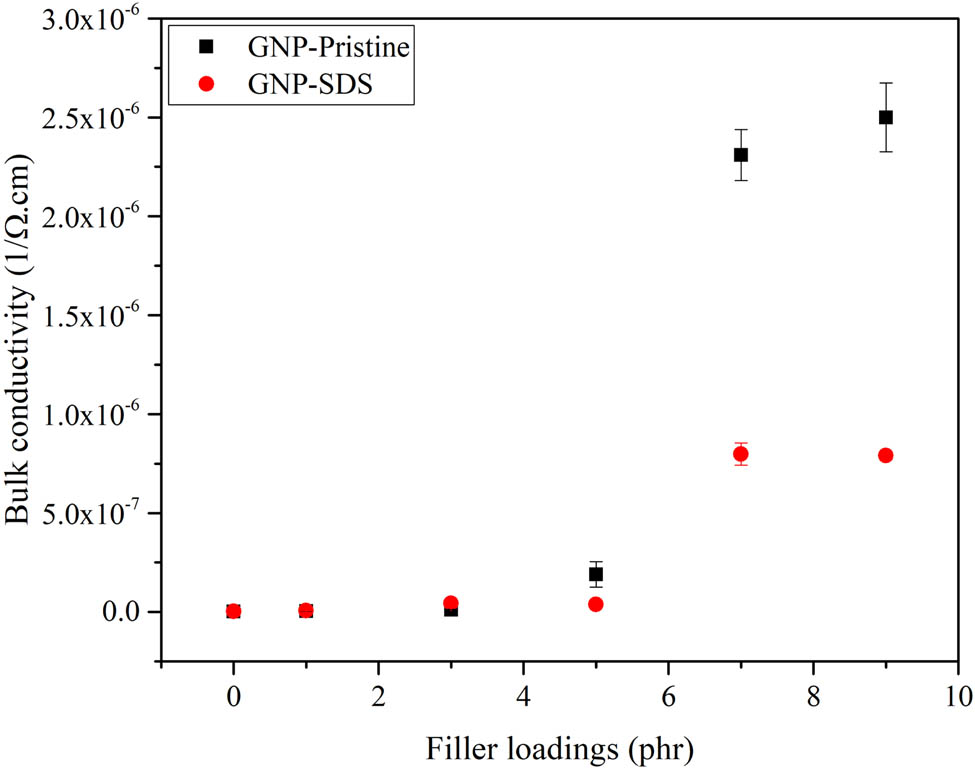

3.6 Electrical conductivity test

Although high filler loading of GNPs diminished the mechanical properties of the composite, it endured a high electrical conductivity to the materials. The variations of bulk resistivity and bulk conductivity of the NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS composites are shown in Figures 8 and 9. At lower filler loading, the NRL/GNP–SDS displayed a higher bulk resistivity and lower bulk conductivity. However, as the filler loading increased, the bulk resistivity of NRL/GNP–SDS reduced obviously to a lower value compared to the NRL/GNP-pristine and at the same time increased the bulk conductivity to a higher value. At low GNP loading, the GNPs were separated and surrounded by a layer of NRL matrix. The GNP particles were unable to contact with each other and remained as an insulator (25). As the GNP loading increased, the dispersed GNP sheets with higher surface area were able to contact with the neighboring GNP sheets. The increase of the continuity of GNP facilitated the construction of conductive networks, more conductive pathways were formed, and more electrons were allowed to travel along the matrix and thus increased the electrical conductivity (26).

Bulk resistivity of NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS with various loadings.

Bulk conductivity of NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS with various loadings.

As compared to the GNP-pristine, the better dispersibility of GNP–SDS within the composites exhibited higher electrical conductivity. This contributed to the penetration of SDS monomers into the GNP–SDS nanofiller and provided high surface area for the adjacent GNP–SDS to interact with each other to form a conductive network rather than aggregate into large clusters within the matrix. Both NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS composite materials achieved percolation threshold at 7 phr with bulk conductivity values of 7.99 × 10−7 and 2.31 × 10−6 Ω−1·cm−1, respectively. When compared with the findings of the other researchers loaded with same species of filler, the silicone rubber (SR)/GNP composites fabricated by Song and coworkers showed a conductivity value around 10−8 S·m−1 at 8 wt% of GNP (27). The lower conductivity of these SR/GNP composites attributed to the higher surface resistivity of the SR matrix as supported by Kamarudin et al. (28).

3.7 Thermal stability

The initial decomposition temperature (T 5), which is defined as the temperature at which 5% of weight loss; the temperature at 50% of weight loss (T 50); and the temperature at maximum rate of decomposition (T max) of the unfilled and filled NRL composites loaded with 0, 1, and 7 phr of GNP-pristine and GNP–SDS, respectively, are recorded in Table 3. It was noticed that the NRL/GNP–SDS displayed better thermal properties than the NRL/GNP-pristine at the same filler loading. Nonetheless, the introduction of GNP only diminished the thermal stability properties of the composite except for the T 50 at 7 phr. This could be attributed to the weak matrix–filler interfacial interaction, which inhibited the heat transfer to occur from the heat-sensitive rubber matrix phase to the high thermal stable reinforcement phase. The heat was not able to transfer from the rubber matrix to GNP, which was stopped by the interfacial gap in between them as shown in Figure 6a, and thus accumulated at the matrix phase. Then, the accumulated heat accelerated the decomposition of the specimen at the lower temperature. On top of that, the SDS-modified GNP improved the thermal stability as compared to the GNP-pristine owned to the better filler dispersion, which provided sufficient surface area to form better interfacial interaction with the matrix for heat transfer to occur efficiently (17).

T 5, T 50, and T max of unfilled NRL and selected NRL composites filled with 1 and 7 phr of GNP-pristine and GNP–SDS

| Samples | T 5 (°C) | T 50 (°C) | T max (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRL | 301 | 378 | 378 |

| NRL/GNP-pristine (1 phr) | 236 | 375 | 369 |

| NRL/GNP-pristine (7 phr) | 274 | 379 | 376 |

| NRL/GNP–SDS (1 phr) | 249 | 375 | 375 |

| NRL/GNP–SDS (7 phr) | 275 | 380 | 377 |

On the other hand, the thermal stability of the composites at 7 phr was higher than the one loaded with 1 phr of GNP. This ascribed to the physical structure and excellent thermal stability of the GNP nanofiller. The high specific surface area of the filler allowed them to arrange themselves and stacked to form a compact platelet structure barrier layer. The volatile decomposed product produced during heating of the materials had to pass the tortuous path to escape to the environment (29). Besides, the thermal stability can be related to the chain mobility of the composites. The immobile chains are able to capture the radicals formed during the chain scissoring of the macromolecular chains under high temperature. Hence, the thermal stability improved with filler concentration (30). Moreover, the GNP played a role to dissipate the heat applied on the composites, thanks to its inherently good thermal conductivity and prevent the heat to concentrate at the matrix phase as the efficiency interfacial interaction formed between the matrix and the filler. This explained why the NRL/GNP–SDS showed a higher thermal stability than the composites loaded with GNP-pristine (30).

4 Conclusions

The dispersibility of GNP within the matrix has contributed a significant effect on the properties of the NRL/GNP composites. The SDS surfactant improved the matrix–filler interaction physically and contributed to its amphiphilic characteristic and stabilized the intercalated GNP–SDS at low filler loading. The intercalated and dispersed GNP–SDS increased the surface area to be interacted with the matrix, thus increasing the routes for the stress transfer from matrix to GNP–SDS for load bearing and thus improved the tensile strength of the NRL/GNP–SDS composites as compared to the NRL/GNP-pristine composites. The addition of GNP led to the increment of the interstitial distance between the NR chains. This reduced the crosslink density and facilitated the solvent to pass through the less dense NR network, leading to the increment of swelling percentage. At high filler loading, the GNP tended to agglomerate for both NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS. Together with the restriction of SIC, the tensile strength reduced as GNP loading increased. However, the restriction of chain mobility by the GNP improved the modulus of the composites. On the other hand, the intercalated GNP also facilitated the formation of a conductive pathway as the surface area increased with better dispersibility. This provides more routes for the electrons to travel along the matrix, leading to the improvement of electrical conductivity once the percolation threshold was achieved at 7 phr of GNP loading for both NRL/GNP-pristine and NRL/GNP–SDS composites. Furthermore, the dispersed GNP allowed the heat transfer through the efficient interfacial and improved the heat stability of the composites. As a conclusion, the dispersibility of the GNP in the NRL matrix gave significant effect on the mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties of the composites.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude for the support of the Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE). The financial support of Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) under grant number FRGS/1/2018/TK05/UNIMAP/02/13 is gratefully acknowledged.

-

Funding information: The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) under the grant number of FRGS/1/2018/TK05/UNIMAP/02/13 from the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia.

-

Author contributions: All the authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this submitted manuscript and approved submission: Wern Ming Che: writing – original draft; Pei Leng Teh: review and editing the content and format; Cheow Keat Yeoh: review and checking of overall manuscript; Jalilah Binti Abd Jalil: review and checking of content and grammar; Bee Ying Lim and Mohamad Syahmie Mohamad Rasidi: review and checking of content and grammar.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

(1) Vaysse L, Bonfils F, Sainte-Beuve J, Cartault M. Natural rubber. Polymer science: a Comprehensive Reference. Burlington House, London: RSC Publishing; 2012. p. 281–93.10.1016/B978-0-444-53349-4.00267-3Search in Google Scholar

(2) Yasmin A, Luo JJ, Daniel IM. Processing of expanded graphite reinforced polymer nanocomposites. Compos Sci Technol. 2006;66(9):1182–9. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2005.10.014 Search in Google Scholar

(3) Mohamed A, Abu Bakar S, Sagisaka M, Esa SR. Rational design of aromatic surfactants for graphene/natural rubber latex nanocomposites with enhanced electrical conductivity. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;516:34–47. 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.01.041.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(4) Srinivasarao Y, Ri Hanum YS, Chan CH, Nandakumar K, Sabu T. Electrical properties of graphene filled natural rubber composites. Adv Mater Res. 2013;812:263–6. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.812.263.Search in Google Scholar

(5) Hsieh AG, Korkut S, Punckt C, Aksay IA. Dispersion stability of functionalized graphene in aqueous sodium dodecyl sulfate solutions. Langmuir. 2013;29(48):14831–8. 10.1021/la4035326.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(6) Mohamed A, Ardyani T, Bakar SA, Brown P, Hollamby M, Sagisaka M, et al. Graphene-philic surfactants for nanocomposites in latex technology. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2016;230:54–69. 10.1016/j.cis.2016.01.003.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(7) Lin YC, Hsu FH, Wu TM, Enhanced conductivity and thermal stability of conductive polyaniline/graphene composite synthesized by in situ chemical oxidation polymerization with sodium dodecyl sulfate. Synth Met. 2013;184:29–34. 10.1016/j.synthmet.2013.Search in Google Scholar

(8) Xing W, Tang M, Wu J, Huang G, Li H, Lei Z et al. Multifunctional properties of graphene/rubber nanocomposites fabricated by a modified latex compounding method. Compos Sci Technol. 2014;99:67–74. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2014.05.011.Search in Google Scholar

(9) Yeon C, Yun SJ, Lee KS, Lim JW. High-yield graphene exfoliation using sodium dodecyl sulfate accompanied by alcohols as surface-tension-reducing agents in aqueous solution. Carbon N Y. 2015;83:136–43. 10.1016/j.carbon.2014.11.035.Search in Google Scholar

(10) Valentı JL, Carretero J, Arroyo M, Lo MA. Morphology/behaviour relationship of nanocomposites based on natural rubber/epoxidized natural rubber blends. Compos Sci Technol. 2007;67(7–8):1330–9. 1330-1339.10.1016/j.compscitech.2006.09.019.Search in Google Scholar

(11) Zarei M, Naderi G, Bakhshandeh GR, Shokoohi S. Ternary elastomer nanocomposites based on NR/BR/SBR: effect of nanoclay composition. J Appl Polym Sci. 2012;127(3):2038–45. 10.1002/app.37687.Search in Google Scholar

(12) Stanier DC, Patil AJ, Sriwong C, Rahatekar SS, Ciambella J. The reinforcement effect of exfoliated graphene oxide nanoplatelets on the mechanical and viscoelastic properties of natural rubber. Compos Sci Technol. 2014;95:59–66. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2014.02.007.Search in Google Scholar

(13) Allahbakhsh A, Mazinani S. Influences of sodium dodecyl sulfate on vulcanization kinetics and mechanical performance of EPDM/graphene oxide nanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2015;5(58):46694–704. 10.1039/c5ra00394f.Search in Google Scholar

(14) Wang Y, Yao B, Chen H, Wang H, Li C, Yang Z. Preparation of anisotropic conductive graphene aerogel/polydimethylsiloxane composites as LEGO® modulars. Eur Polym J. 2019;112: 487–92. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2019.01.036.Search in Google Scholar

(15) Tang L, Zhao L, Guan L. Graphene/polymer composite materials: processing, properties and applications. In: Advance composites materials: properties and applications. 1st edn. Hangzhou: Sciendo; 2017. Vol. 5. Issue 58. p. 349–419.10.1515/9783110574432-007Search in Google Scholar

(16) Phua JL, Teh PL, Ghani SA, Yeoh CK. Effect of heat assisted bath sonication on the mechanical and thermal deformation behaviours of graphene nanoplatelets filled epoxy polymer composites. Int J Polym Sci. 2016;2016:1–8. 10.1155/2016/9767183.Search in Google Scholar

(17) Atif R, Shyha I, Inam F. Mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties of graphene-epoxy nanocomposites – a review. Polymers. 2016;8(281):1–37.10.3390/polym8080281.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(18) Formela K, Hejna A, Piszczyk Ł, Saeb MR, Colom X. Processing and structure–property relationships of natural rubber/wheat bran biocomposites. Cellulose. 2016;23(5):3157–75. 10.1007/s10570-016-1020-0.Search in Google Scholar

(19) La DD, Nguyen TA, Quoc VD, Nguyen TT, Nguyen DA, Duy LNP, et al. A new approach of fabricating graphene nanoplates@natural rubber latex composite and its characteristics and mechanical properties. J Carbon Res. 2018;4(3):50–60. 10.3390/c4030050.Search in Google Scholar

(20) Tang L, Zhao L, Qiang F, Wu Q, Gong L. Mechanical properties of rubber nanocomposites containing carbon nanofillers. In: Carbon-based nanofillers and their rubber nanocomposites. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Inc; 2019. p. 367–424.10.1016/B978-0-12-817342-8.00012-3Search in Google Scholar

(21) Zedler L, Colom X, Saeb MR, Formela K. Preparation and characterization of natural rubber composites highly filled with brewers’ spent grain/ground tire rubber hybrid reinforcement. Compos Part B Eng. 2018;145:182–8. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.03.024.Search in Google Scholar

(22) Wang J, Xue Z, Li Y, Li G, Wang Y, Zhong.W. Synergistically effects of copolymer and core-shell particles for toughening epoxy. Polymer. 2018;140:39–46.10.1016/j.polymer.2018.02.031Search in Google Scholar

(23) Wu X, Lin TF, Tang ZH, Guo BC, Huang GS. Natural rubber/graphene oxide composites: effect of sheet size on mechanical properties and strain-induced crystallization behavior. Express Polym Lett. 2015;9(8):672–85. 10.3144/expresspolymlett.2015.63.Search in Google Scholar

(24) Mphahlele K, Ray SS, Kolesnikov A. Self-healing polymeric composite material design, failure analysis and future outlook: a review. Polymers. 2017;9(10):1–22. 10.3390/polym9100535.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(25) Potts JR, Shankar O, Du L, Ruoff RS. Processing–morphology–property relationships and composite theory analysis of reduced graphene oxide/natural rubber nanocomposites. Macromolecules. 2012;45(15):6045–55. 10.1021/ma300706k.Search in Google Scholar

(26) Araby S, Zaman I, Meng Q, Kawashima N. Michelmore A, Kuan HC, et al. Melt compounding with graphene to develop functional, high-performance elastomers. Nanotechnology. 2013;24(16):1–14. 10.1088/0957-4484/24/16/165601.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(27) Song Y, Yu J, Yu L, Alam FE, Dai W, Li C, et al. Enhancing the thermal, electrical and mechanical properties of silicone rubber by addition of graphene nanoplatelets. Mater Des. 2015;88:950–7. 10.1016/j.matdes.2015.09.064.Search in Google Scholar

(28) Kamarudin N, Razak JA, Mohamad N, Norddin N, Aman A. Mechanical and electrical properties of silicone rubber based composite for high voltage insulator application. Int J Eng Technol. 2018;7:452–7. 10.14419/ijet.v7i3.25.17729.Search in Google Scholar

(29) Wang J, Shi Z, Ge Y, Wang Y, Fan J, Yin J. Solvent exfoliated graphene for reinforcement of PMMA composites prepared by in situ polymerization. Mater Chem Phys. 2012;136:43–50. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.06.017.Search in Google Scholar

(30) Zhang G, Wang F, Dai J, Huang Z. Effect of functionalization of graphene nanoplatelets on the mechanical and thermal properties of silicone rubber composites. Materials (Basel). 2016;9(2):1–13. 10.3390/ma9020092.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2022 Wern Ming Che et al., published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes