Abstract

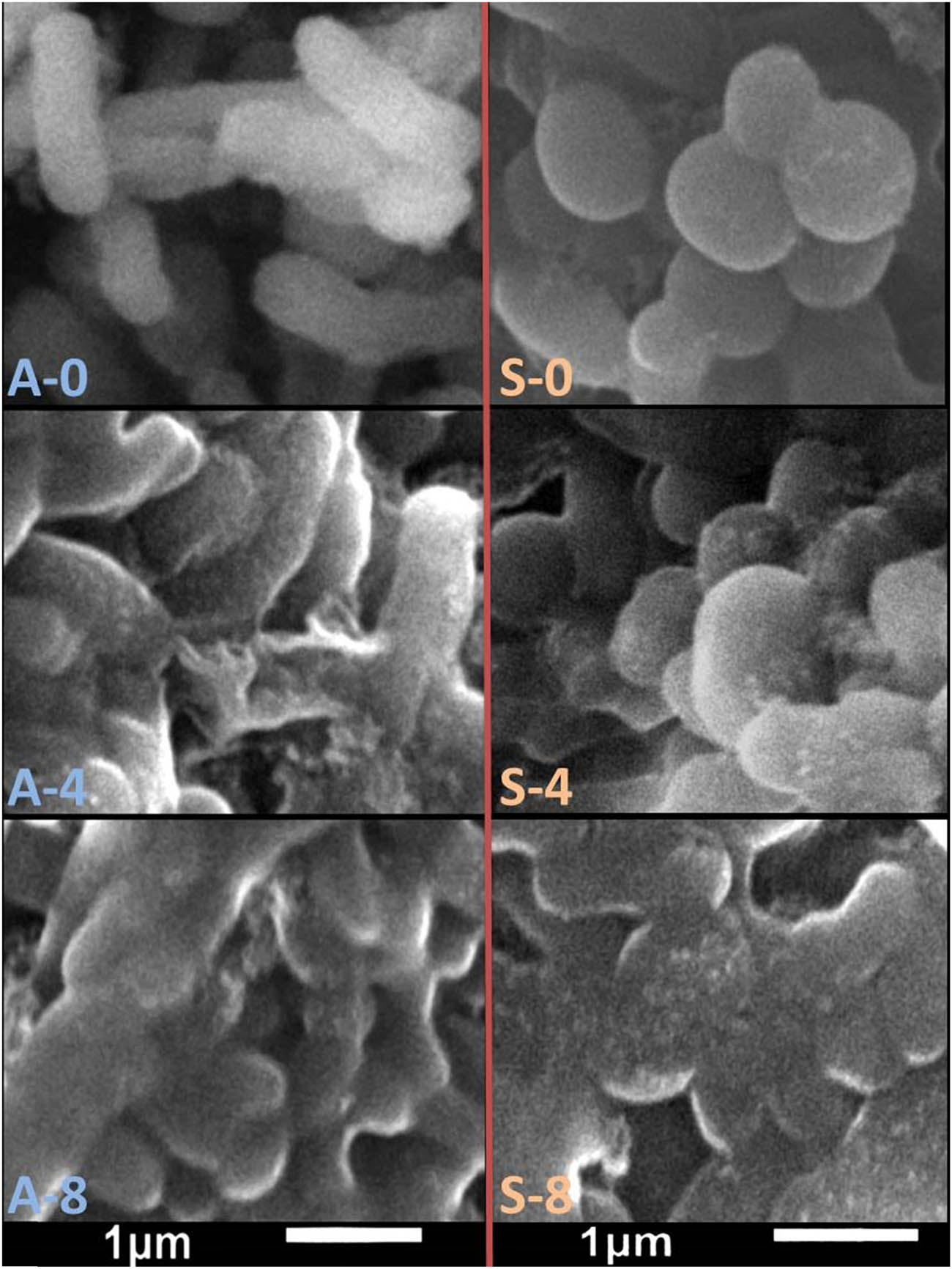

For controlling pathogenic bacteria using nanopolymer composites with essential oils, the formulation of chitosan/alginate nanocomposites (CS/ALG NCs) loaded with thyme oil, garlic oil, and thyme/garlic oil was investigated. Oils were encapsulated in CS/ALG NCs through oil-in-water emulsification and ionic gelation. The CS/ALG NCs loaded with oils of garlic, thyme, and garlic–thyme complex had mean diameters of 143.8, 173.9, and 203.4 nm, respectively. They had spherical, smooth surfaces, and zeta potential of +28.4 mV for thyme–garlic-loaded CS/ALG NCs. The bactericidal efficacy of loaded NCs with mixed oils outperformed individual loaded oils and ampicillin, against foodborne pathogens. Staphylococcus aureus was the most susceptible (with 28.7 mm inhibition zone and 12.5 µg·mL−1 bactericidal concentration), whereas Escherichia coli was the most resistant (17.5 µg·mL−1 bactericidal concentration). Scanning electron microscopy images of bacteria treated with NCs revealed strong disruptive effects on S. aureus and Aeromonas hydrophila cells; treated cells were totally exploded or lysed within 8 h. These environmentally friendly nanosystems might be a viable alternative to synthetic preservatives and be of interest in terms of health and food safety.

1 Introduction

Bacterial foodborne infections and outbreaks are enduring global threats. Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other pathogenic bacteria present in food can cause deterioration and contribute to the development of foodborne disease (1). Foodborne illness is believed to represent a serious public health hazard worldwide, with 420,000 fatalities happening each year (2). One potential strategy for lowering foodborne infections is the development of efficient preservation systems capable of eradicating microbial contamination of food (3). Antibiotic resistance in microorganisms has arisen because of widespread usage of accustomed antibiotics, posing a threat to public health (4). As a result, there is an essential need for antibacterial herbal remedies (5).

Essential oils (EOs) are a complex combination of volatile components generated from aromatic and other plant species’ secondary metabolism (6). Antiseptic, antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-parasitic, antifungal, and insecticidal properties have been reported for EOs (7). Thymol and carvacrol are the main active constituents of the thyme (Thymus vulgaris) family (Liliaceae) (8). Thyme oil has antibacterial and antimicrobial properties, making it valuable as a medicinal herb and as a food preservative (9). Diallyl disulfide, alliin, and allicin are the main active components of the garlic (Allium sativum) family (Liliaceae) (10). Garlic EO has been shown to prevent the growth of Shigella dysenteriae, E. coli, S. aureus, and Salmonella typhi (11).

However, EOs have a number of undesirable physiochemical features that prevent them from being extensively used. EOs can induce off-flavors and change the color of food products (12). The antibacterial and antioxidant properties of EOs are severely limited due to their extremely volatile and poor water-soluble components (13). Encapsulating EOs can boost the concentration of bioactive components in food areas where microorganisms grow, such as water-rich phases or liquid–solid interfaces (14). The nanoencapsulation of EOs protects the active ingredients from environmental influences such as oxygen, light, moisture, and pH (15). It also enhances their distribution and controlled release by trapping in the core of the membrane wall’s nanocapsule structure and/or adsorption onto the carrier (16). The encapsulation of EOs in nanoemulsions has shown to be a novel method for enhancing their potency, stability, and use (17). Nanoemulsions are significantly more stable against flocculation, coalescence, and creaming due to their tiny particle sizes, making them a great choice for food industries as well as pharmaceutical and medication delivery agents (14).

Because of their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and extended in vivo circulation duration, alginate (ALG) and chitosan (CS) have gained the most attention among nanocarriers (18). CS is a cationic linear polysaccharide composed of linked d-glucosamine and N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (19). Because of its advantageous properties such as abundant sources of supply, controlled, easy extraction, and biocompatibility, it has the potential to be used in the manufacture of nanoparticles (20). It has a unique property known as the permeation enhancing effect, which boosts the permeability of hydrophilic substances (21). ALG is a naturally occurring negatively charged polysaccharide composed of co-polymers of -l-glucuronic acid and -d-mannuronic acid extracted from brown seaweed (22). Alginic acid forms an insoluble ALG skin at low pH, limiting the release of encapsulated compounds. However, with higher pH, it transforms into a soluble viscous layer, releasing the contained components (21). CS, which is cationic, and ALG, which is anionic, combine to form an outstanding polyelectrolyte complex (PEC) (23).

As far as we are aware, no published articles have been presented on the antibacterial properties of thyme and garlic EOs encapsulated in CS/ALG nanocomposites (NCs) as yet. As a result, the goals of this study were to (i) synthesize innovative CS/ALG NCs containing thyme and garlic EOs through oil-in-water emulsification and ion gelation techniques, (ii) investigate the physiochemical properties and structural characteristics of novel thyme and garlic EOs loaded CS/ALG NCs, and (iii) assess the antibacterial activities and action modes.

2 Experimental

All used chemicals, media, and reagents in the current study were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO), unless other sources were mentioned.

2.1 Bacterial strains and cultures

Three different bacterial strains were tested: E. coli (ATCC-35218), S. aureus (ATCC-25923), and Aeromonas hydrophila (ATCC-27853). The bacterial cultures were cultivated on Trypticase soy broth and agar (TSB and TSA, Difco, Sparks, MD) at 37°C for 24–48 h. Microbial inocula were prepared by adjusting the turbidity of the medium to match the 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard. The cultures of microorganisms were maintained in TSA slants at 4°C throughout the study and used as stock culture.

2.2 Extraction of sodium ALG

Sargassum latifolium alga was collected from Red Sea coast, Hurghada, Egypt, following the institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. The seaweeds were rinsed with distilled water, dried in the shade, and ground into a fine powder. Biomass (1.5% w/v) was soaked in a 2% citric acid solution for one night before being rinsed with distilled water. For 4 h at 40°, the acidified algal biomass was suspended in a 3% Na2CO3 solution for ALG extraction. Filtration was used to collect the supernatants following extraction. Ethanol (1:2 v/v) was used to precipitate sodium ALG. The precipitated ALG was collected using vacuum filtration and left to dry at room temperature (24).

2.3 Extraction of CS

Shrimp (Penaeus monodon) shell waste was collected from the local fish market. The shells were washed properly with flowing tap water, dried in sun for 8 h and then ground into fine powder. About 15 g of powdered shells was treated with 4% HCl at solid to solvent ratio of 1:10 for 16 h with constant stirring at 200 rpm in an incubator shaker at 25°C. The samples were washed with tap water until they reached neutral pH, and dried at 45°C. Afterward, samples were treated with 4% (w/v) of NaOH solution at solid to solvent ratio of 1:20 for 4 h with constant stirring at 200 rpm in an incubator shaker at 50°C. The sample was washed with tap water for achieving neutral pH and then dried. The obtained chitin was treated with 60% (w/v) NaOH solution for 24 h at 60°C, followed by washing until it reached neutral pH. The sample was then washed with distilled water until reaching neutral pH, and dried at 45°C (25).

2.4 Preparation of CS/ALG NC

Ionic gelation was used to prepare a CS/ALG NC (26). CS powder was dissolved in 1% (v/v) aqueous acetic acid to yield concentrations of 0.6% (w/v). Sodium ALG was dissolved in distilled water to form homogeneous solutions of 0.3% (w/v). The pH of the ALG and CS solutions were first adjusted to 5 and 5.5, respectively. For ALG nanoparticles (NPs) preparation, 20 mL of aqueous calcium chloride (0.6 mg·mL−1) was added dropwise to 50 mL of sodium ALG solution while sonicating with a microtip probe ultrasonic sonicator (XK97-2 two-way homoiothermy magnetic stirrer), then the resultant calcium ALG pre-gel was further sonicated for 60 min. For CS NPs, an aqueous solution (0.5%, w/v) of Na-tripolyphosphate was prepared and 30 mL from this solution was dropped slowly (at 18 mL·h−1 rate) into 50 mL of CS solution, while stirring vigorously at 780×g. The resulted CS NPs were harvested via centrifugation at 10,800×g for 35 min, dried at 45°C and reconstituted in deionized water to have 1.0% (w/v) concentration. For CS/ALG NCs formation, 25 mL of CS NPs solution was dropped into equal volume of calcium ALG pre-gel solution and stirred (720×g) for 90 min. The resultant suspension was equilibrated overnight to allow nanospheres to form, having uniform particle size. The formed NCs were harvested via centrifugation, dried at 45°C, and reconstituted in deionized water to have 0.1% (w/v) concentration.

2.5 Preparation of thyme and garlic EOs loaded CS/ALG NC

Emulsification processes are used generally in the preparation of EOs loaded CS/ALG NC. The CS/ALG NCs solution in deionized water was prepared (0.1%, w/v) and used for loading with EOs loading. Thyme oil-loaded NC was prepared by adding 0.6 mL of thyme oil solution (20 mg·mL−1) dropwise into 20 mL of CS-ALG NCs solution. Garlic oil-loaded NC were prepared by addition of 0.6 mg·mL−1 of the garlic oil into 20 mL of CS/ALG NC dropwise. The mixtures were subjected to sonication for 60 min, for each. Garlic oil–thyme oil-loaded NC was prepared by addition of 0.3 mg·mL−1 of the garlic oil and 0.3 mg·mL−1 of thyme oil into 20 mL of CS/ALG NC and sonicated. The resulting emulsion was equilibrated overnight, and solvent was removed by rotatory evaporation at 40°C (27). The formed EOs loaded CS/ALG NCs were centrifuged at 10,800×g for 35 min and lyophilized for further analysis.

2.6 Characterization of EOs loaded CS/ALG NC

2.6.1 Particle size and zeta potential of NC

Particle size and zeta potential of the NCs were analyzed through a dynamic light scattering method using a Zetasizer 3000 HS, Malvern Instruments, UK. The nanoemulsions were diluted with distilled water to a suitable concentration (1:10) at room temperature before analysis. The analysis was performed in triplicates at a temperature of 25°C.

2.6.2 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The shape and size of EOs loaded CS/ALG NC were distinguished by SEM. The NCs were lyophilized, placed onto a self-adhesive carbon disc mounted on SEM stubs and sputter-coated with gold/palladium using a cool-sputter coater (E5100 II, Polaron Instruments Inc., Hatfield, PA) and examined using SEM (S-500, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) operating at 8 kV.

2.6.3 Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The chemical functional groups of CS NPs, ALG NPs, CS/ALG NC, thyme oil-loaded CS/ALG NCs, and garlic oil-loaded CS/ALG NCs were determined by an FTIR. For FTIR analysis, the samples were lyophilized and mixed with KBr powder to obtain the pellets. The FTIR spectra were obtained at a resolution of 4 cm−1 in the 4,000–500 cm−1 region using Thermo Fisher Nicolet IS10, USA.

2.7 Antimicrobial activity of EOs loaded CS/ALG NC

The antimicrobial activity of EOs loaded CS/ALG NC was assayed by agar well diffusion method. Each test microorganism was grown in TSB at 37°C overnight and diluted to 2 × 107 colony forming unit (CFU)·mL−1. Wells of 6 mm diameter were made on agar plates using a cork borer. About 20 µL of EOs loaded CS/ALG NCs aqueous solution (concentration 0.1%, w/v) was injected into the wells. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated by measuring the zone of inhibition (ZOI) around the wells. The inhibition zones are given as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Studies were performed in triplicate. Discs of ampicillin (10 μg, Sigma, St Louis, MO) were used as positive controls (28).

For determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of EOs loaded CS/ALG NC, micro-dilution broth method was used. The stock concentrations of nanoparticles were diluted by serial dilutions method to obtain concentrations in the range 1–100 µg·mL−1. Each test microorganism was grown in TSB at 37°C overnight and diluted to 2 × 107 CFU·mL−1. In sterile 96-well plates, 20 µL of each dilution of NCs was placed into the well containing 20 µL of bacterial suspension and incubated overnight at 37°C. Subsequently, 20 μL of p-iodonitrotetrazolium violet aqueous solution were dropped into each well and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The plates were read at 570 nm in a plate reader (Multiskan GO Thermo Scientific™, Waltham, MA). MIC was defined as the lowest NC concentration that completely inhibited bacterial growth. Triplicate samples were performed for each sample. Ampicillin was used as positive control. Wells containing culture medium and bacteria were used as negative control (29).

2.8 SEM imaging of bacterial strains treated with garlic/thyme oil-CS/ALG NC

Bacterial morphology before and after treatment with garlic/thyme oil-loaded CS/ALG NC was analyzed by SEM. In brief, logarithmic growth phase of A. hydrophila and S. aureus bacterial cultures (2 × 107 CFU·mL−1) were treated for 0, 4, and 8 h with garlic/thyme oil-loaded CS/ALG NC at MIC values. For 30 min, cells were fixed with a fixative buffer (2.5% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M Na-cacodylate buffer, pH 7.35). Following washing with ultrapure water, the samples were dehydrated using a succession of ethanol solutions (10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, and 99%). The dehydrated samples were dried with a critical point drier (Auto-Samdri-815 Automatic Critical Point Dryer; Tousimis, Rockville, MD), mounted on SEM stubs, and sputter-coated with gold/palladium using a cool-sputter coater (E5100 II, Polaron Instruments Inc., Hatfield, PA). Sections were then examined using the SEM at 8 kV (30).

2.9 Statistical analysis

Triplicated experiments were conducted (three assessments/each analysis); results mean ± standard deviation (SD) were computed via Microsoft Excel 365. The ANOVA and t-test of SPSS package (SPSS V-11.5, Chicago, IL) were used for statistically analyzing the significances of data (at p ≤ 0.05).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization

3.1.1 Particle size and zeta potential analysis

Size and zeta potential of the synthesized nanomaterials are essential physiochemical features for nanoparticles (31). Table 1 shows that the mean diameters of CS NPs, ALG NPs, and CS/ALG NC were 73.8, 86.6, and 128.7 nm, respectively. NCs have larger particle size diameter due to aggregation of isolated nanoparticles (32). It can be also shown that the mean diameter of garlic oil-loaded CS/ALG NC, thyme oil-loaded CS/ALG NC, and garlic–thyme CS/ALG NC have average diameter of 143.8, 173.9, and 203.4 nm, respectively. With the addition of EOs, the particle size of the CS/ALG NC gradually became larger. This may be due to the embedding of EOs (33).

Particles size distribution and charges (zeta potential) of synthesized nanoparticles and NC

| Nanomolecules | Particles range (nm) | Mean diameter (nm) ± SD* | Zeta potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS NPs | 16.5–168.6 | 73.8 ± 4.2a | +36.9 |

| ALG NPs | 19.3–193.4 | 86.6 ± 5.3b | −24.2 |

| CS/ALG NCs | 20.9–263.2 | 128.7 ± 7.1c | +32.5 |

| Thyme oil-CS/ALG NCs | 41.8–324.9 | 173.9 ± 9.7d | +28.5 |

| Garlic oil-CS/ALG NCs | 22.3–283.6 | 143.8 ± 7.9c | +26.6 |

| Thyme/garlic oil-CS/ALG NCs | 46.5–435.8 | 203.4 ± 11.3e | +28.4 |

Abbreviations: CS NPs – chitosan nanoparticles, ALG NP – alginate nanoparticles, CS/ALG NCs – chitosan–alginate nanocomposite.

*Triplicated experiments mean; dissimilar superscript letters within one column indicate significant difference (p ≤ 0.05).

Zeta potential is the surface charge, which can greatly influence the particle stability in suspension through the electrostatic repulsion between the particles (34). Table 1 shows that zeta potentials of CS NPs, CS/ALG NC, thyme oil-loaded CS/ALG NC, garlic oil-loaded CS/ALG NC, and garlic oil–thyme oil-loaded CS/ALG NC were +36.9, +32.5, +28.5, +26.6, +28.4 mV, respectively, while that of ALG NPs is −24.2 mV at pH 5.5. Since the amine groups are positively charged due to protonation at low pH levels, CS can be a water-soluble cationic polyelectrolyte (21). The carboxyl group of ALG and amino group of CS can form PEC. PEC formation is due to charge neutralization mainly by electrostatic interactions between polyanion–polycation systems (35). The greater concentration of CS to ALG resulted in the positive zeta potential of the CS/ALG NC (36). The positivity of the CS/ALG NCs decreased with the embedding of the EOs due to the charge generated by the NCs containing EOs shielding the CS amino groups (37). It was also shown that absolute differences in zeta potential values were more than 10 mV. Losso et al. (38) stated that emulsions with absolute zeta potential differences greater than 10 mV allow for the prediction of unique stability. MojtabaTaghizadeh et al. (39) stated that the accepted range of zeta potential to give good stability in solution is −30 to −20 mV or +20 to +30 mV. The positive zeta potential of nanoparticles allows for extended adhesion to bacteria’s negatively charged cell membrane (40).

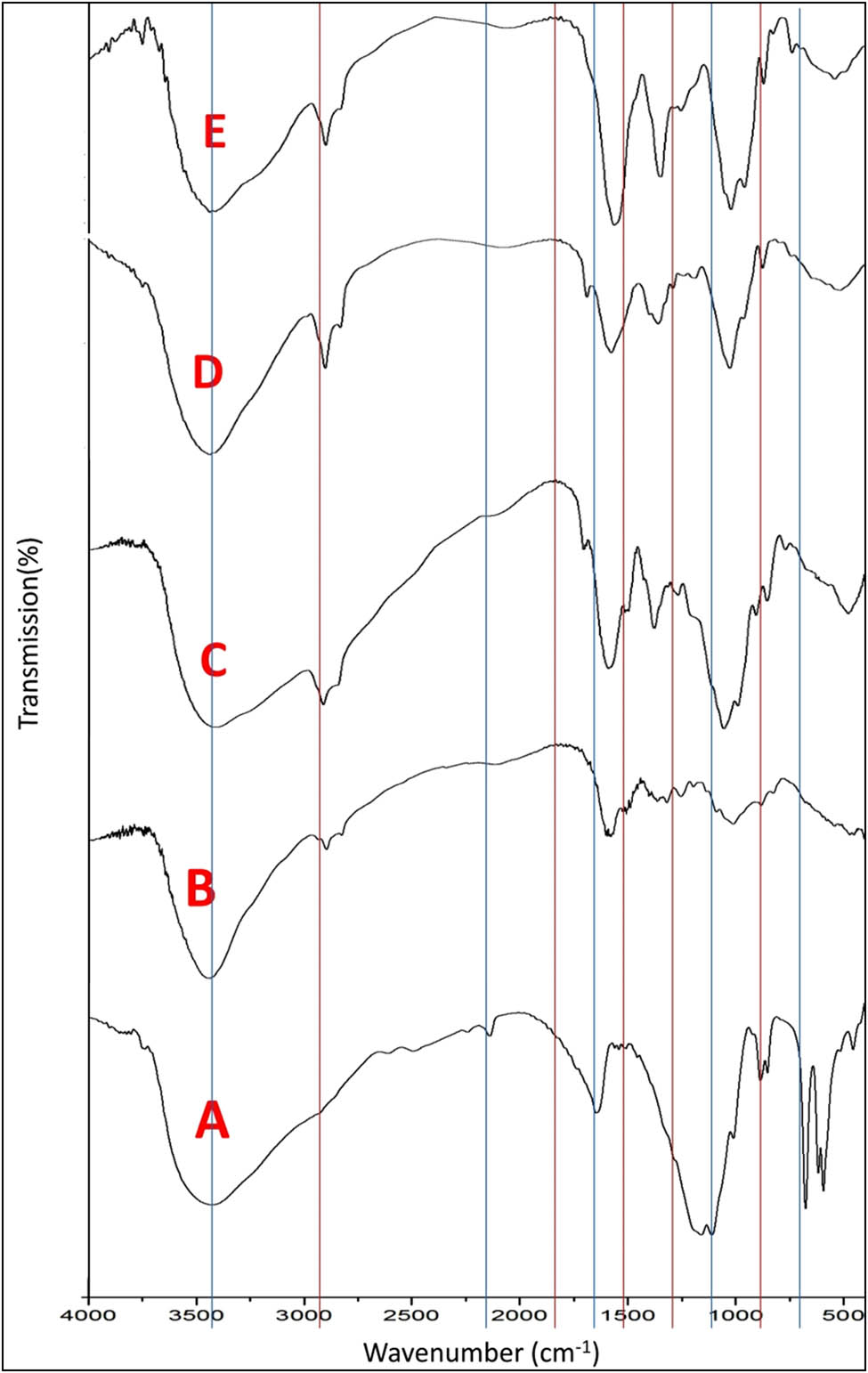

3.1.2 FTIR measurement

FTIR spectra of sodium ALG NPs showed mannuronic acid functional group at wavenumber 884 cm−1 and the uronic acid at wavenumber 939 cm−1. The asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of carboxylate groups (COO−) on the polymeric backbone of ALG appeared at 1,614 and 1,417 cm−1, respectively. A broadband at 3,420 cm−1 and a weak signal at 2,230 cm−1 were assigned to hydrogen bonded O–H and C–H stretching vibrations, respectively (41) (“A” Figure 1). The principal spectral features of CS NPs are as follows: A broadband between 3,750 and 2,500 cm−1, associated with the stretch of the O–H and N–H bonds, 2,878 cm−1 (C–H stretch) in pyranose ring, 1,647 cm−1 (amide I band, C═O stretch), 1,561 cm−1 (N–H bending of amine), 1,152 cm−1 (antisymmetric stretch C–O–C and C–N stretch), and 1,032 cm−1 (skeletal vibration of C–O stretch) (42) (“B” in Figure 1). FTIR spectra of ALG/CS NC showed that stretching peak of O–H and N–H groups was shifted to 3,355 cm−1 and the peak of N–H stretching vibration was shifted to 1,407 cm−1. In addition, the asymmetrical and –CO stretching vibration at 1,653 cm−1 shifted to 1,605 cm−1 because of the reaction between sodium ALG and CS. Furthermore, the –NH2 bending peak at 1,560 cm−1 disappeared due to interaction of the amine group of CS with the carboxylic group of ALG to form PEC (43) (“C” in Figure 1).

FTIR of ALG NPs (A), CS NPs (B), ALG/CS NCs (C), thyme loaded-CS/ALG NCs (D), and garlic loaded-CS/ALG NCs (E).

FTIR spectra of thyme oil-loaded ALG/CS NC show broadband at 3,229 cm−1 corresponding to phenolic –OH stretching involving hydrogen bonding. Peak at 2,952 cm−1 was attributed to the C–H stretching vibration of aromatic compound. The peaks at 1,700 and 1,612 cm−1 were attributed to N–C bending of the aliphatic CH2 groups. The absorption peaks at 1,583, 1,350, and 1,250 cm−1 were characteristic peaks of thymol. The band at 800 cm−1 is attributed to aromatic C–H wagging vibrations (44) (“D” in Figure 1). FTIR spectra of garlic oil-loaded ALG/CS NC show broadband at 3,229 cm−1, corresponding to phenolic –OH stretching involving hydrogen bonding. Peak at 1,036 cm−1 indicates S═O group, revealing the presence of organosulfur compounds such as alliin and allicin (45) (“E” in Figure 1).

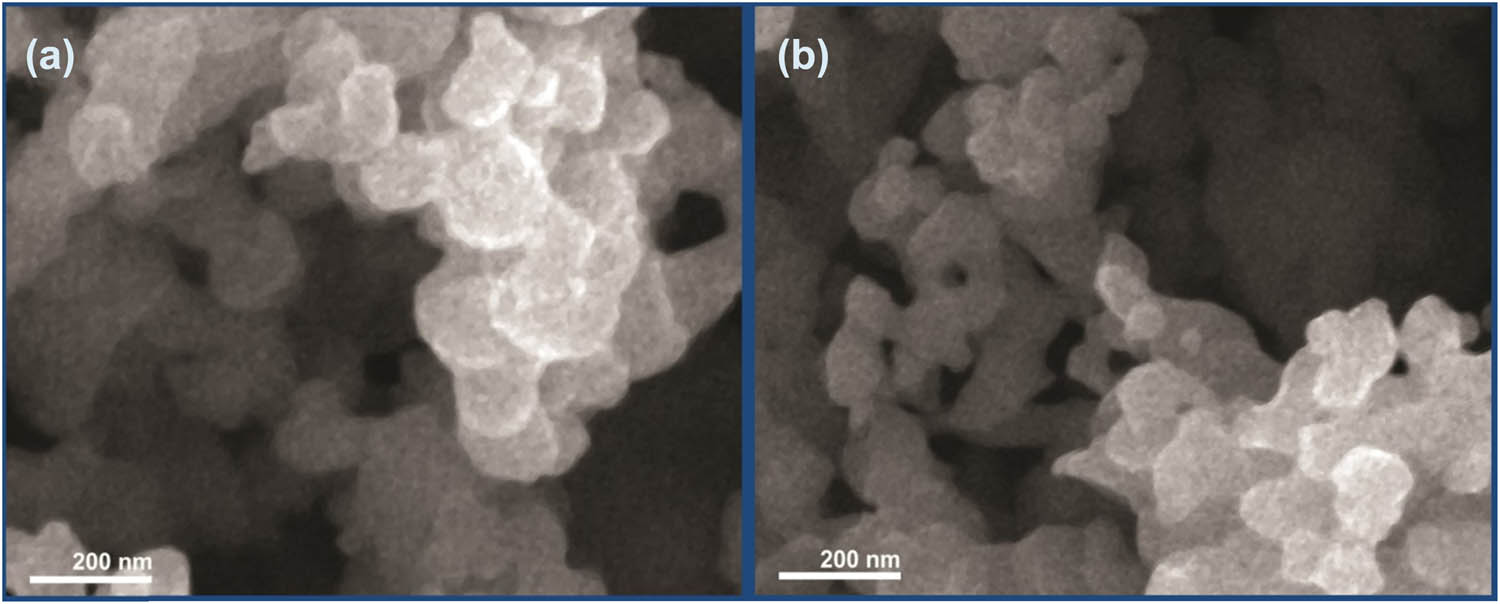

3.1.3 SEM

SEM analysis was carried out to visualize the size and shape of EOs loaded NCs. Thyme oil-CS/ALG NC and garlic oil-CS/ALG NC were uniformly distributed, had spherical shape morphology, and their surface was smooth. The mean size of thyme oil-CS/ALG NC and garlic oil-CS/ALG NC were 176.2 and 145.5 nm, respectively (Figure 2). This result agrees with the size distribution results. Harmonized results were obtained by Natrajan et al. (21), who stated that EOs loaded NCs had spherical shape and their mean size was found to be below 300 nm with aggregation. The smooth surface of NCs indicates that the EOs were well encapsulated in NCs (33).

Scanning microscopy images of EOs loaded NCs: (a) thyme oil-CS/ALG NC and (b) garlic oil-CS/ALG NC.

3.2 Antimicrobial activity

3.2.1 ZOI, MIC, and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

Different bacterial strains (one Gram positive and two Gram negative) were examined for their susceptibility to EOs loaded CS/ALG NCs The results reported in Table 2 show that thyme oil-loaded CS/ALG NCs, garlic oil-loaded CS/ALG NCs and garlic–thyme oils loaded CS/ALG NCs exhibited a remarkable zones of inhibition for all tested species.

Antimicrobial activity of thyme oil-CS/ALG NC, garlic oil-CS/ALG NC, and garlic/thyme oil-CS/ALG NC against bacterial strains

| Challenged bacteria | Thyme oil-CS/ALG NCs | Garlic oil-CS/ALG NCs | Garlic/thyme oil-CS/ALG NCs | Ampicillin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZOI* | MIC | MBC | ZOI | MIC | MBC | ZOI | MIC | MBC | ZOI | MIC | MBC | |

| S. aureus | 27.6 ± 2.4 | 10.0 | 17.5 | 24.8 ± 1.7 | 12.5 | 15.0 | 28.7 ± 2.7 | 7.5 | 12.5 | 23.8 ± 1.8 | 12.5 | 17.5 |

| E. coli | 22.3 ± 2.1 | 15.0 | 22.5 | 21.9 ± 3.2 | 15.0 | 20.0 | 24.6 ± 3.3 | 15.0 | 17.5 | 19.6 ± 2.6 | 17.5 | 20.0 |

| A. hydrophila | 24.5 ± 1.9 | 12.5 | 25.0 | 20.3 ± 2.8 | 17.5 | 25.0 | 26.8 ± 3.5 | 17.5 | 15.0 | 21.8 ± 2.2 | 20.0 | 22.5 |

Abbreviations: ZOI – zone of inhibition (mm), MIC – minimum inhibitory concentration (µg·mL−1), MBC – minimum bactericidal concentration (µg·mL−1).

*Triplicated experiments mean ± SD.

Regarding thyme oil-loaded CS/ALG NCs, the highest ZOI (27.6 ± 2.4 mm), the lowest MIC, and lowest MBC (10 and 17.5 µg·mL−1) were recorded against S. aureus. While, the lowest ZOI (22.3 ± 2.1 mm), the highest MIC and MBC (15 and 22.5 µg·mL−1) were recorded against E. coli. Regarding garlic oil-loaded CS/ALG NCs, the highest ZOI (24.8 ± 1.7 mm), the lowest MIC and MBC (12.5 and 15 µg·mL−1) were recorded against S. aureus. While, the lowest ZOI (20.3 ± 2.8 mm), the highest MIC and MBC (17.5 and 25 µg·mL−1) were recorded against A. hydrophila. Regarding thyme–garlic oils loaded CS/ALG NCs, the highest ZOI (28.7 ± 2.7 mm), the lowest MIC and MBC (7.5 and 12.5 µg·mL−1) were recorded against S. aureus. While, the lowest ZOI (24.6 ± 3.3 mm), the highest MIC and MBC (15 and 17.5 µg·mL−1) were recorded against E. coli. No significant differences (at p ≤ 0.05) were reported either between treatment ZOIs or between them and standard antibiotic (ampicillin), which indicates the efficiency of NCs, compared to standardized antibiotic. The increased sensitivity of (G+) bacteria may be related to the outer membrane’s relative permeability in comparison to (G−) bacteria (46). Gram-negative bacteria have a thick lipopolysaccharide layer that decreases microorganism’s susceptibility (47).

CS is a non-toxic, biodegradable, and biocompatible natural polymer that is bacteriostatic and bactericidal and has inherent antibacterial activity (48). The electrostatic interactions between the polycationic structure of CS and the negatively charged bacterial cell wall cause rupture of the cell, thereby affecting membrane permeability, followed by attachment to DNA, causing inhibition of DNA replication and, ultimately, cell death (49). Another suggested mechanism is that CS serves as a chelating agent, binding to trace metal elements and producing toxins while inhibiting microbial growth (50). In the case of Gram-negative bacteria, CS can form a polymer membrane around the bacterium, preventing nutrients from entering (51). CS, being a positively charged molecule, interacts with teichoic acid in S. aureus’ cell wall, affecting cell permeability (52).

The antibacterial character of the thyme oil studied appears to be related to its high phenolic content, notably carvacrol and thymol. Some studies suggested that thymol’s antibacterial mechanism was caused, at least in part, by a shift in the lipid component of the bacterial plasma membrane, resulting in alterations in membrane permeability and the escape of intracellular content (53). It has been hypothesized that phenolic components such as thymol and carvacrol suppress calcium and potassium transport via partitioning in the lipid phase of the membrane and therefore modifying the local environment of calcium channels (54). Garlic has been studied and reported to have inhibitory effects against other bacterial strains including S. typhi, E. coli, and S. aureus; the garlic’s organosulfur compounds are expected to scavenge free radicals and inhibit bacterial growth via interactions with sulfur-containing enzymes (55).

The antibacterial effect of EO-loaded NCs was greater than that of CS and EOs alone (56). The nanometric scale (subcellular dimensions) of the CS-based nanosystems including EOs resulted in a significant increase in bactericidal activity when compared to pure EOs and unloaded CS NPs, indicating a synergistic impact. CS nanoparticles can operate as active carriers, boosting EO penetration over the bacterial cell membrane, due to interactions between the CS cationic group and the anionic components on the cell membrane surface (57).

3.2.2 Morphological test of the bacterial cells

SEM images of the effect of a garlic/thyme oil-CS/ALG NC on the morphological and structural features of A. hydrophila and S. aureus are shown in Figure 3. Before being exposed to NC, the morphology of S. aureus can be seen in Figure 3 (subfigure S-0), having a normal and spherical shape and a well-preserved cell membrane. However, after being exposed to the garlic/thyme oil-CS/ALG NC (Figure 3, subfigures S-4 and S-8), the morphology of S. aureus was distorted. The peptidoglycan structure of the cell seemed depressed, suggesting that the intracellular material had seeped out. The decrease in cell size, length, and diameter seen in S. aureus in response to the active chemical might be attributable to cytosolic fluid leaking outside the cells. Untreated A. hydrophila cells were rod-shaped, regular, and had intact morphology (Figure 3, subfigure A-0). However, after exposing cells to a garlic/thyme oil-CS/ALG NC (Figure 3, subfigures A-4 and A-8), SEM pictures revealed morphological changes and lyses of the outer membrane integrity. The electrostatic reaction between CS NPs and bacteria might explain this phenomenon. This was followed by the creation of pores or the disintegration of the membrane (20,58).

Scanning microscopy images of A. hydrophila (A) and S. aureus (S) treated with garlic/thyme oil-CS/ALG NC for 0, 4, and 8 h.

4 Conclusion

Based on the data obtained, we can infer that CS/ALG NCs containing EOs of thyme and garlic might be offered as an efficient and potent antibacterial agent against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. They caused bacterial cell to burst or lyse, and its antibacterial effect was more potent in Gram-positive bacteria. The application of CS/ALG NC loaded with EOs of thyme and garlic could be recommended as a preservative agent against foodborne pathogens, in food industry. Further practical applications of this innovative NC in foodstuffs preservation are suggested for future investigations.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the support from University of Sadat City and Kafrelsheikh University, Egypt.

-

Funding information: Authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Shrifa Elghobashy: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, resources, formal analysis, writing – original draft; A.B. Abeer Mohammed: conceptualization, supervision, investigation, validation, writing – review and editing; Ahmed Tayel: conceptualization, supervision, methodology, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing; Fawzia Alshubaily: resources, data curation, visualization, formal analysis; Asmaa Abdella: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – original draft.

-

Conflict of interest: Authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

(1) Miladi H, Zmantar T, Chaabouni Y, Fedhila K, Bakhrouf A, Mandouani K, et al. Antibacterial and efflux pump inhibitors of thymol and carvacrol against food-borne pathogens. Microb Pathogene. 2016;99:95–100.10.1016/j.micpath.2016.08.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(2) Lee H, Yoon Y. Etiological agents implicated in foodborne illness worldwide. Food Sci Anim Resour. 2021;41(1):1–7.10.5851/kosfa.2020.e75Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(3) Singh S, Shalini R. Effect of hurdle technology in food preservation: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56:641–9.10.1080/10408398.2012.761594Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(4) Chouhan S, Sharma K, Guleria S. Antimicrobial activity of some essential oils-present status and future perspectives. Medicines. 2017;4(3):58.10.3390/medicines4030058Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(5) Fisher K, Phillips C. Potential antimicrobial uses of essential oils in food: is citrus the answer? Trends Food Sci Technol. 2008;19:156–64.10.1016/j.tifs.2007.11.006Search in Google Scholar

(6) Bassolé IHN, Juliani HR. Essential oils in combination and their antimicrobial properties. Molecules. 2012;17:3989–4006.10.3390/molecules17043989Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(7) Donsì F, Ferrari G. Essential oil nanoemulsions as antimicrobial agents in food. J Biotechnol. 2016;233:106–20.10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.07.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(8) Porte A, Godoy RLO. Chemical composition of Thymus vulgaris L. (thyme) essential oil from the Rio de Janeiro State (Brazil). J Serb Chem Soc. 2008;73(3):307–10.10.2298/JSC0803307PSearch in Google Scholar

(9) Xue J, Davidson PM, Zhong Q. Antimicrobial activity of thyme oil co-nanoemulsified with sodium caseinate and lecithin. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;210:1–8.10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.06.003Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(10) Kodera Y, Ushijima M, Amano H, Suzuki J, Matsutomo T. Chemical and biological properties of S-1-propenyl-L-cysteine in aged garlic extract. Molecules. 2017;22:570.10.3390/molecules22040570Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(11) Goncagul G, Ayaz E. Antimicrobial effect of garlic (Allium sativum). Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2010;5(1):91–3.10.2174/157489110790112536Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(12) Taghavi T, Kim C, Rahemi A. Role of natural volatiles and essential oils in extending shelf life and controlling postharvest microorganisms of small fruits. Microorganisms. 2018;2018(6):10.10.3390/microorganisms6040104Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(13) Tripathi S, Mehrotra G, Dutta P. Chitosan based antimicrobial films for food packaging applications. e-Polymers. 2008;8(1):093. 10.1515/epoly.2008.8.1.1082 Search in Google Scholar

(14) Donsì F, Annunziata M, Sessa M, Ferrari G. Nanoencapsulation of essential oils to enhance their antimicrobial activity in foods. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2011;44(9):1908–14.10.1016/j.lwt.2011.03.003Search in Google Scholar

(15) Gavini E, Sanna V, Sharma R, Juliano C, Usai M, Marchetti M, et al. Solid lipid microparticles (SLM) containing juniper oil as anti-acne topical carriers: preliminary studies. Pharm Dev Technol. 2005;10(4):479–87.10.1080/10837450500299727Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(16) Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, Campos EVR, Rodriguez-Torres MD, Acosta-Torres LS, et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnol. 2018;16(71):1–33.10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(17) Moghimi R, Ghaderi L, Rafati H, Aliahmadi A, McClements DJ. Superior antibacterial activity of nanoemulsion of Thymus daenensis essential oil against E. coli. Food Chem. 2016;194:410–5.10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.07.139Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(18) Rahmani O, Bouzid B, Guibadj A. Extraction and characterization of chitin and chitosan: applications of chitosan nanoparticles in the adsorption of copper in an aqueous environment. e-Polymers. 2017;17(5):383–97. 10.1515/epoly-2016-0318.Search in Google Scholar

(19) Almutairi FM, El Rabey HA, Alalawy AI, Salama AA, Tayel AA, Mohammed GM, et al. Application of chitosan/alginate nanocomposite incorporated with phycosynthesized iron nanoparticles for efficient remediation of chromium. Polymers. 2021;13(15):2481.10.3390/polym13152481Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(20) Alishahi A. Antibacterial effect of chitosan nanoparticle loaded with nisin for the prolonged effect. J Food Safe. 2014;34:111–8.10.1111/jfs.12103Search in Google Scholar

(21) Natrajan D, Srinivasan S, Sundar K, Ravindran A. Formulation of essential oil-loaded chitosan–alginate nanocapsules. J Food Drug Anal. 2015;23:560–8.10.1016/j.jfda.2015.01.001Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(22) Fertah M, Belfkira A, Dahmane El, Taourirte M, Brouillette F. Extraction and characterization of sodium alginate from Moroccan Laminaria digitata brown seaweed. Arab J Chem. 2017;10:3707–14.10.1016/j.arabjc.2014.05.003Search in Google Scholar

(23) Meng X, Tian F, Yang J, He CN, Xing N, Li F. Chitosan and alginate polyelectrolyte complex membranes and their properties for wound dressing application. Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2010;21:1751–9.10.1007/s10856-010-3996-6Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(24) Sugiono S, Ferdiansyah D. Biorefinery for sequential extraction of fucoidan and alginate from brown alga Sargassum cristaefolium. Carpathian J Food Sci Technol. 2020;12:88–9.10.34302/crpjfst/2020.12.2.9Search in Google Scholar

(25) Benhabiles MS, Salah R, Lounici H, Drouiche N, Goosen MFA, Mameri N. Antibacterial activity of chitin, chitosan and its oligomers prepared from shrimp shell waste. Food Hydrocoll. 2012;29(1):48–56.10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.02.013Search in Google Scholar

(26) Loquercio A, Castell-Perez E, Gomes C, Moreira RG. Preparation of chitosan–alginate nanoparticles for trans-cinnamaldehyde entrapment. J Food Sci. 2015;80:N2305–15.10.1111/1750-3841.12997Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(27) Lertsutthiwong P, Rojsitthisak P, Nimmannit U. Preparation of turmeric oil-loaded chitosan–alginate biopolymeric nanocapsules. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2009;29:856–60.10.1016/j.msec.2008.08.004Search in Google Scholar

(28) Islam M, Masum S, Mahbub KR, Haque Z. Antibacterial activity of crab-chitosan against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. J Adv Sci Res. 2011;2:63–6.Search in Google Scholar

(29) Tayel AA, Hussein H, Sorour NM, El‐Tras WF. Foodborne pathogens prevention and sensory attributes enhancement in processed cheese via flavoring with plant extracts. J Food Sci. 2015;80(12):M2886–91.10.1111/1750-3841.13138Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(30) Tayel AA, El-tras WF, Moussa S, El-baz AF, Mahrous H, Salem MF, et al. Antibacterial action of zinc oxide nanoparticles against foodborne pathogens. J Food Saf. 2011;31:211–8.10.1111/j.1745-4565.2010.00287.xSearch in Google Scholar

(31) Khana I, Saeed K, Idrees Khan I. Nanoparticles: properties, applications and toxicities. Arab J Chem. 2019;12(7):908–31.10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.05.011Search in Google Scholar

(32) Ashraf MA, Peng W, Zare Y, Rhee KY. Effects of size and aggregation/agglomeration of nanoparticles on the interfacial/interphase properties and tensile strength of polymer nanocomposites. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2018;13:214.10.1186/s11671-018-2624-0Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(33) Alghuthaymi MA, Diab AM, Elzahy AF, Mazrou KE, Tayel AA, Moussa SH. Green biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles by cinnamon extract and their antimicrobial activity and application as edible coatings with nano-chitosan. J Food Qual. 2021;2021:6670709. 10.1155/2021/6670709.Search in Google Scholar

(34) Larsson M, Hill A, Duffy J. Suspension stability, why particle size, zeta potential and rheology are important. Annu Trans Nordic Rheol Soc. 2012;20:209–14.Search in Google Scholar

(35) Becherán-Marón L, Peniche C, Argüelles-Monal W. Study of the interpolyelectrolyte reaction between chitosan and alginate: influence of alginate composition and chitosan molecular weight. Int J Biol Macromol. 2004;34(1–2):127–33.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2004.03.010Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(36) Sampraist W, Sutananta W, Opanasopit P. Effect of chitosan and alginate concentrations on particle size and zeta potential of chitosan–alginate micro/nanoparticles containing A-mangostin. BHST. 2017;15:72–6.Search in Google Scholar

(37) Tayel AA, Moussa SH, Salem MF, Mazrou KE, El‐Tras WF. Control of citrus molds using bioactive coatings incorporated with fungal chitosan/plant extracts composite. J Sci Food Agric. 2016;96(4):1306–12.10.1002/jsfa.7223Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(38) Losso JN, Khachatryan A, Ogawa M, Godber JS, Shih F. Random centroid optimization of phosphatidylglycerol stabilized lutein-enriched oil-in-water emulsions at acidic pH. Food Chem. 2005;92:737–44.10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.12.029Search in Google Scholar

(39) MojtabaTaghizadeh S, Javan R. Preparation and investigation of chitosan nanoparticles including salicylic acid as a model for an oral drug delivery system. e-Polymers. 2010;10(1):036. 10.1515/epoly.2010.10.1.370.Search in Google Scholar

(40) Mukhopadhyaya P, Chakrabortya S, Bhattacharya S, Mishra R, Kundu PP. pH-sensitive chitosan/alginate core–shell nanoparticles for efficient and safe oral insulin delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;72(2015):640–8.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.08.040Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(41) Moradhaseli S, Mirakabadi AZ, Sarzaeem A, dounighi NM, Soheily S, Borumand MR. Preparation and characterization of sodium alginate nanoparticles containing ICD-85 venom derived peptides. Int J Innov Appl Stud. 2013;4(3):534–42.Search in Google Scholar

(42) Tayel AA, Moussa S, Opwis K, Knittel D, Schollmeyer E, Nickisch-Hartfiel A. Inhibition of microbial pathogens by fungal chitosan. Int J Biol Macromol. 2010;47(1):10–4.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.04.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(43) Al-Gethami W, Al-Qasmi N. Antimicrobial activity of Ca-alginate/chitosan nanocomposite loaded with camptothecin. Polymers. 2021;13:3559.10.3390/polym13203559Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(44) Hu J, Zhang Y, Xiao Z, Wang X. Preparation and properties of cinnamon–thyme–ginger composite essential oil nanocapsules. Ind Crop Prod. 2018;122:85–92.10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.05.058Search in Google Scholar

(45) Divya BJ, Suman B, Venkataswamy M, Thyagaraju K. A study on phytochemicals, functional groups and mineral composition of Allium sativum (garlic) cloves. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2017;9(3):1–4.10.22159/ijcpr.2017.v9i3.18888Search in Google Scholar

(46) Clifton LA, Skoda MWA, Le Brun AP, Ciesielski F, Kuzmenko I, Holt SA, et al. Effect of divalent cation removal on the structure of gram-negative bacterial outer membrane models. Langmuir 31:404–12.10.1021/la504407vSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(47) Delcour AH. Outer membrane permeability and antibiotic resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1794;5:808–16.10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.005Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(48) Yan D, Li Y, Liu Y, Na L, Zhang X, Yan C. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan and chitosan derivatives in the treatment of enteric infections. Molecules. 2021;26:7136.10.3390/molecules26237136Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(49) Moussa SH, Tayel AA, Al-Turki AI. Evaluation of fungal chitosan as a biocontrol and antibacterial agent using fluorescence-labeling. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013;54:204–8.10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.12.029Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(50) Divya K, Vijayan S, Tijith KG, Jisha MS. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan nanoparticles: mode of action and factors affecting activity. Fibers Polym. 2017;18:221–30.10.1007/s12221-017-6690-1Search in Google Scholar

(51) Sánchez-Machado D, López-Cervantes J, Martínez-Ibarra D, Escárcega-Galaz A, Vega-Cázarez C. The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: a review. e-Polymers. 2022;22(1):75–86. https://doi.org/10.1515/epoly-2022-0011 Search in Google Scholar

(52) Davidova VN, Naberezhnykh GA, Yermak IM, Gorbach VI, Solov’eva TF. Determination of binding constants of lipopolysaccharides of different structure with chitosan. Biochemistry (Moscow). 2006;71:332–9.10.1134/S0006297906030151Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(53) de Souza EL, de Barros JC, de Oliveira CEV, da Conceição ML. Influence of Origanum vulgare L. essential oil on enterotoxin production, membrane permeability and surface characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;137:308–11.10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.11.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(54) Rúa J, Del Valle P, de Arriaga D, Fernández-Álvarez L, García-Armesto MR. Combination of carvacrol and thymol: antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and antioxidant activity. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2019;16(9):622–9.10.1089/fpd.2018.2594Search in Google Scholar PubMed

(55) Bhatwalkar SB, Mondal R, Krishna SBN, Adam JK, Govender P, Anupam R. Antibacterial properties of organosulfur compounds of garlic (Allium sativum). Front Microbiol. 2021;12:1–20.10.3389/fmicb.2021.613077Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(56) Jubair N, Rajagopal M, Chinnappan S, Abdullah NB, Fatima A. Review on the antibacterial mechanism of plant-derived compounds against multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDR). Evid-based Complement Altern Med. 2021;2021:3663315. 10.1155/2021/3663315 Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(57) Granata G, Stracquadanio S, Leonardi M, Napoli E, Malandrino G, Cafiso V, et al. Oregano and thyme essential oils encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles as effective antimicrobial agents against foodborne pathogens. Molecules. 2021;26:4055.10.3390/molecules26134055Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

(58) Rajagopal V, Rajathurai S, Parthasarathy K, Gimbun J, Ramakrishnan P, Ramakrishnan RP, et al. Review of nano-chitosan based drug delivery of plant extracts for the treatment of breast cancer. Trends Biomater Artif Organs. 2022;36(S1):83–7.Search in Google Scholar

© 2022 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes

Articles in the same Issue

- Research Articles

- The effect of isothermal crystallization on mechanical properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)

- The effect of different structural designs on impact resistance to carbon fiber foam sandwich structures

- Hyper-crosslinked polymers with controlled multiscale porosity for effective removal of benzene from cigarette smoke

- The HDPE composites reinforced with waste hybrid PET/cotton fibers modified with the synthesized modifier

- Effect of polyurethane/polyvinyl alcohol coating on mechanical properties of polyester harness cord

- Fabrication of flexible conductive silk fibroin/polythiophene membrane and its properties

- Development, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of adhesive fibrous mat for mucosal propranolol delivery

- Fused deposition modeling of polypropylene-aluminium silicate dihydrate microcomposites

- Preparation of highly water-resistant wood adhesives using ECH as a crosslinking agent

- Chitosan-based antioxidant films incorporated with root extract of Aralia continentalis Kitagawa for active food packaging applications

- Molecular dynamics simulation of nonisothermal crystallization of a single polyethylene chain and short polyethylene chains based on OPLS force field

- Synthesis and properties of polyurethane acrylate oligomer based on polycaprolactone diol

- Preparation and electroactuation of water-based polyurethane-based polyaniline conductive composites

- Rapeseed oil gallate-amide-urethane coating material: Synthesis and evaluation of coating properties

- Synthesis and properties of tetrazole-containing polyelectrolytes based on chitosan, starch, and arabinogalactan

- Preparation and properties of natural rubber composite with CoFe2O4-immobilized biomass carbon

- A lightweight polyurethane-carbon microsphere composite foam for electromagnetic shielding

- Effects of chitosan and Tween 80 addition on the properties of nanofiber mat through the electrospinning

- Effects of grafting and long-chain branching structures on rheological behavior, crystallization properties, foaming performance, and mechanical properties of polyamide 6

- Study on the interfacial interaction between ammonium perchlorate and hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene in solid propellants by molecular dynamics simulation

- Study on the self-assembly of aromatic antimicrobial peptides based on different PAF26 peptide sequences

- Effects of high polyamic acid content and curing process on properties of epoxy resins

- Experiment and analysis of mechanical properties of carbon fiber composite laminates under impact compression

- A machine learning investigation of low-density polylactide batch foams

- A comparison study of hyaluronic acid hydrogel exquisite micropatterns with photolithography and light-cured inkjet printing methods

- Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of apoptin plasmid in cancer treatment

- Thermal stability, mechanical, and optical properties of novel RTV silicone rubbers using octa(dimethylethoxysiloxy)-POSS as a cross-linker

- Preparation and applications of hydrophilic quaternary ammonium salt type polymeric antistatic agents

- Coefficient of thermal expansion and mechanical properties of modified fiber-reinforced boron phenolic composites

- Synergistic effects of PEG middle-blocks and talcum on crystallizability and thermomechanical properties of flexible PLLA-b-PEG-b-PLLA bioplastic

- A poly(amidoxime)-modified MOF macroporous membrane for high-efficient uranium extraction from seawater

- Simultaneously enhance the fire safety and mechanical properties of PLA by incorporating a cyclophosphazene-based flame retardant

- Fabrication of two multifunctional phosphorus–nitrogen flame retardants toward improving the fire safety of epoxy resin

- The role of natural rubber endogenous proteins in promoting the formation of vulcanization networks

- The impact of viscoelastic nanofluids on the oil droplet remobilization in porous media: An experimental approach

- A wood-mimetic porous MXene/gelatin hydrogel for electric field/sunlight bi-enhanced uranium adsorption

- Fabrication of functional polyester fibers by sputter deposition with stainless steel

- Facile synthesis of core–shell structured magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2@Au molecularly imprinted polymers for high effective extraction and determination of 4-methylmethcathinone in human urine samples

- Interfacial structure and properties of isotactic polybutene-1/polyethylene blends

- Toward long-live ceramic on ceramic hip joints: In vitro investigation of squeaking of coated hip joint with layer-by-layer reinforced PVA coatings

- Effect of post-compaction heating on characteristics of microcrystalline cellulose compacts

- Polyurethane-based retanning agents with antimicrobial properties

- Preparation of polyamide 12 powder for additive manufacturing applications via thermally induced phase separation

- Polyvinyl alcohol/gum Arabic hydrogel preparation and cytotoxicity for wound healing improvement

- Synthesis and properties of PI composite films using carbon quantum dots as fillers

- Effect of phenyltrimethoxysilane coupling agent (A153) on simultaneously improving mechanical, electrical, and processing properties of ultra-high-filled polypropylene composites

- High-temperature behavior of silicone rubber composite with boron oxide/calcium silicate

- Lipid nanodiscs of poly(styrene-alt-maleic acid) to enhance plant antioxidant extraction

- Study on composting and seawater degradation properties of diethylene glycol-modified poly(butylene succinate) copolyesters

- A ternary hybrid nucleating agent for isotropic polypropylene: Preparation, characterization, and application

- Facile synthesis of a triazine-based porous organic polymer containing thiophene units for effective loading and releasing of temozolomide

- Preparation and performance of retention and drainage aid made of cationic spherical polyelectrolyte brushes

- Preparation and properties of nano-TiO2-modified photosensitive materials for 3D printing

- Mechanical properties and thermal analysis of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced polyimine composites

- Preparation and in vitro biocompatibility of PBAT and chitosan composites for novel biodegradable cardiac occluders

- Fabrication of biodegradable nanofibers via melt extrusion of immiscible blends

- Epoxy/melamine polyphosphate modified silicon carbide composites: Thermal conductivity and flame retardancy analyses

- Effect of dispersibility of graphene nanoplatelets on the properties of natural rubber latex composites using sodium dodecyl sulfate

- Preparation of PEEK-NH2/graphene network structured nanocomposites with high electrical conductivity

- Preparation and evaluation of high-performance modified alkyd resins based on 1,3,5-tris-(2-hydroxyethyl)cyanuric acid and study of their anticorrosive properties for surface coating applications

- A novel defect generation model based on two-stage GAN

- Thermally conductive h-BN/EHTPB/epoxy composites with enhanced toughness for on-board traction transformers

- Conformations and dynamic behaviors of confined wormlike chains in a pressure-driven flow

- Mechanical properties of epoxy resin toughened with cornstarch

- Optoelectronic investigation and spectroscopic characteristics of polyamide-66 polymer

- Novel bridged polysilsesquioxane aerogels with great mechanical properties and hydrophobicity

- Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks dispersed in waterborne epoxy resin to improve the anticorrosion performance of the coatings

- Fabrication of silver ions aramid fibers and polyethylene composites with excellent antibacterial and mechanical properties

- Thermal stability and optical properties of radiation-induced grafting of methyl methacrylate onto low-density polyethylene in a solvent system containing pyridine

- Preparation and permeation recognition mechanism of Cr(vi) ion-imprinted composite membranes

- Oxidized hyaluronic acid/adipic acid dihydrazide hydrogel as cell microcarriers for tissue regeneration applications

- Study of the phase-transition behavior of (AB)3 type star polystyrene-block-poly(n-butylacrylate) copolymers by the combination of rheology and SAXS

- A new insight into the reaction mechanism in preparation of poly(phenylene sulfide)

- Modified kaolin hydrogel for Cu2+ adsorption

- Thyme/garlic essential oils loaded chitosan–alginate nanocomposite: Characterization and antibacterial activities

- Thermal and mechanical properties of poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate)/calcium carbonate composite with single continuous morphology

- Review Articles

- The use of chitosan as a skin-regeneration agent in burns injuries: A review

- State of the art of geopolymers: A review

- Mechanical, thermal, and tribological characterization of bio-polymeric composites: A comprehensive review

- The influence of ionic liquid pretreatment on the physicomechanical properties of polymer biocomposites: A mini-review

- Influence of filler material on properties of fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review

- Rapid Communications

- Pressure-induced flow processing behind the superior mechanical properties and heat-resistance performance of poly(butylene succinate)

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of semifluorinated liquid-crystalline block copolymers

- RAFT polymerization-induced self-assembly of poly(ionic liquids) in ethanol

- Topical Issue: Recent advances in smart polymers and their composites: Fundamentals and applications (Guest Editors: Shaohua Jiang and Chunxin Ma)

- Fabrication of PANI-modified PVDF nanofibrous yarn for pH sensor

- Shape memory polymer/graphene nanocomposites: State-of-the-art

- Recent advances in dynamic covalent bond-based shape memory polymers

- Construction of esterase-responsive hyperbranched polyprodrug micelles and their antitumor activity in vitro

- Regenerable bacterial killing–releasing ultrathin smart hydrogel surfaces modified with zwitterionic polymer brushes