Abstract

Nine poly(amic acid)s (PAAs) were synthesized by reacting butane-1,4-diyl bis(1,3-dioxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylate) dianhydride with various diamine monomers, including m-xylylenediamine, p-xylylenediamine, 4,4′-oxydianiline, bis(3-aminophenyl) sulfone, bis[4-(3-aminophenoxy)phenyl] sulfone, 2,2′-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzidine, N,N′-[2,2′-bis(trifluoromethyl)-4,4′-biphenylene]bis(3-aminobenzamide), 2,2-bis[4-(4-aminophenoxy)phenyl]propane, and 2,2-bis[4-(4-aminophenoxy)phenyl]hexafluoropropane. These PAAs were subsequently converted into colorless and transparent polyimide (CPI) films via thermal imidization under various heat treatment conditions. To achieve CPI films with suppressed charge transfer complex formation, the selected diamine monomers featured bent molecular structures, strong electron-withdrawing substituents such as –CF3 or –SO2–, or ether/ketone functional groups incorporated within the backbone. The thermomechanical properties, optical transparency, and solubility of the resulting CPI films were systematically evaluated, and the structure–property relationships between the monomers and CPI film performance were elucidated. Overall, CPI films derived from aromatic or linear main-chain structures exhibited excellent thermal and mechanical properties. In contrast, films incorporating bent structures with polar functional groups or electron-withdrawing substituents in the main chain showed superior optical transparency and solubility.

1 Introduction

Polyimides (PIs) and PI-based composites have long been recognized for their exceptional thermomechanical properties, chemical resistance, and, in some cases, optical transparency. These materials have been widely utilized in high-performance applications across various industries, including aerospace, electronics, and automotive sectors [1], 2]. Aromatic PIs, in particular, are known for their excellent thermal stability and flexibility, making them indispensable in the manufacturing of electronic devices and solar panels [3], [4], [5]. Furthermore, flexible PI composites have shown significant promise in emerging fields such as electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding and mechano-electronics [6].

Despite these numerous advantages, conventional PIs typically exhibit a dark brown color due to the formation of charge transfer complexes (CTCs) between polymer chains. This inherent coloration significantly limits their use in optoelectronic applications, particularly in flexible displays, where high optical transparency is essential [7], [8], [9].

To develop colorless and transparent polyimides (CPIs), several strategies have been employed to suppress CTC formation: 1. Incorporating bent monomers in ortho- (o-) or meta- (m-) configurations to disrupt chain linearity [10], 11]. 2. Introducing bulky substituents into the polymer backbone to inhibit molecular stacking and π-electron delocalization [12], 13]. 3. Using strong electron-withdrawing groups such as trifluoromethyl (–CF3) and hexafluoroisopropylidene (–C(CF3)2–) to reduce π–π interactions [14], [15], [16]. 4. Incorporating flexible ether (–O–), sulfone (–SO2–), or ketone linkages to increase chain mobility [17], [18], [19]. 5. Employing cycloaliphatic monomers devoid of π-electrons to enhance transparency [20], [21], [22]. Although CPIs derived from cycloaliphatic monomers offer superior solubility, lower dielectric constants, and higher optical transparency than aromatic CPIs, they often suffer from diminished thermal and mechanical performance due to weakened interchain interactions and reduced resonance stabilization [23], 24].

Recently, CPIs have found increasing use not only in display technologies but also in semiconductor packaging, where low weight and high dimensional stability are required [25]. Additionally, CPIs are being explored as flexible, lightweight plastic substrates to replace traditional glass in advanced electronic devices. In contrast to indium tin oxide (ITO) glass, which is expensive and brittle due to its indium content and rigidity, CPI films offer high thermal stability, excellent optical transmittance, and mechanical flexibility – making them ideal candidates for next-generation bendable, rollable, and wearable electronics [26]. Glass materials also present challenges in high-temperature processes due to their brittleness and thermal shock sensitivity. In comparison, CPI offers processability, lightweight characteristics, and comparable or superior performance [27], 28].

Most CPIs developed to date have utilized rigid aromatic monomers to ensure thermal and mechanical robustness [29]. However, such structures often result in poor solubility and limited processability due to strong π–π interactions and rigidity. Moreover, aromatic components absorb significantly in the visible spectrum, leading to undesirable coloration in the resulting films.

In this study, we employed butane-1,4-diyl bis(1,3-dioxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylate) (BU-DA), a novel dianhydride containing a flexible aliphatic segment between aromatic rings, as the core dianhydride monomer. The flexibility of BU-DA helps reduce main-chain rigidity and suppress CTC formation. Nine diamine monomers were selected based on their potential to yield CPI characteristics due to the presence of flexible alkyl and ether groups or strong electron-withdrawing substituents such as –CF3 and (–C(CF3)2–). Some diamines featured fully bent m-configurations, while others had linear backbones with pendant alkyl substituents.

CPI films were synthesized via thermal imidization of the resulting poly(amic acid) (PAA) precursors. The nine diamines used in this work were m-xylylenediamine (m-XDA), p-xylylenediamine (p-XDA), 4,4′-oxydianiline (4,4′-ODA), bis(3-aminophenyl) sulfone (m-APS), bis[4-(3-aminophenoxy)phenyl] sulfone (m-BAPS), 2,2′-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzidine (TFB), N,N′-[2,2′-bis(trifluoromethyl)-4,4′-biphenylene]bis(3-aminobenzamide) (m-TFAB), 2,2-bis[4-(4-amino-phenoxy)phenyl]propane (BAPP), and 2,2-bis[4-(4-aminophenoxy)phenyl]hexafluoropropane (6FBAPP). A series of CPI films were fabricated, and their thermomechanical properties, solubility, and optical transparency were thoroughly investigated.

The objective of this study was to optimize reaction conditions for the synthesis of CPIs and to elucidate the relationships between the molecular structures of the diamine monomers and the physical properties of the resulting CPI films. Special attention was given to analyzing the effects of diamine structure on CTC formation and its influence on optical transparency and other key performance metrics.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Butane-1,4-diyl bis(1,3-dioxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylate) (BU-DA) was obtained from Lum. Tech. Co. (Taipei, Taiwan). (The nine diamine monomers – m-XDA, p-XDA), 4,4′-ODA, m-APS, m-BAPS, TFB, m-TFAB, BAPP, and 6FBAPP – were purchased from TCI (Tokyo, Japan) and used without further purification. N,N′-Dimethylacetamide (DMAc), purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Yongin, Korea), was dried thoroughly to remove moisture before use.

2.2 Synthesis of CPI Films

Scheme 1 illustrates the synthesis route of CPI films via a two-step process involving PAA formation followed by thermal imidization. As the procedures for all nine diamine monomers were essentially identical, the synthesis using m-XDA is described here as a representative example: BU-DA (5.698 g, 1.3 × 10−2 mol) was completely dissolved in 50 mL of dried DMAc under stirring for 30 min. Then, m-XDA (1.770 g, 1.3 × 10−2 mol) was added to the BU-DA solution, and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C under a nitrogen atmosphere for 1 h. The solution was then polymerized at room temperature for 14 h to form the PAA precursor.

Synthetic routes for CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

The resulting PAA solution was cast uniformly onto a clean glass plate, followed by vacuum stabilization at 50 °C for 1 h. The solvent was then gradually removed under vacuum at 80 °C for an additional hour. The PAA film was subsequently thermally imidized at various temperatures under a nitrogen atmosphere, with specific thermal treatment conditions summarized in Table 1. After thermal imidization, the resulting CPI film was immersed in a 5 wt% aqueous hydrofluoric acid (HF) solution to detach it from the glass substrate. The final freestanding CPI films were obtained with dimensions up to 10 × 10 cm2.

Heat treatment conditions of CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

| Sample | Temperature (°C)/time (h)/pressure (Torr) |

|---|---|

| PAA | 0/1/760 → 25/14/760 → 50/1/1 → 80/1/1 |

| CPI | 110/0.5/760 → 140/0.5/760 → 170/0.5/760 →

200/0.5/760 → 230/0.5/760 → 250/0.5/760 |

2.3 Characterization

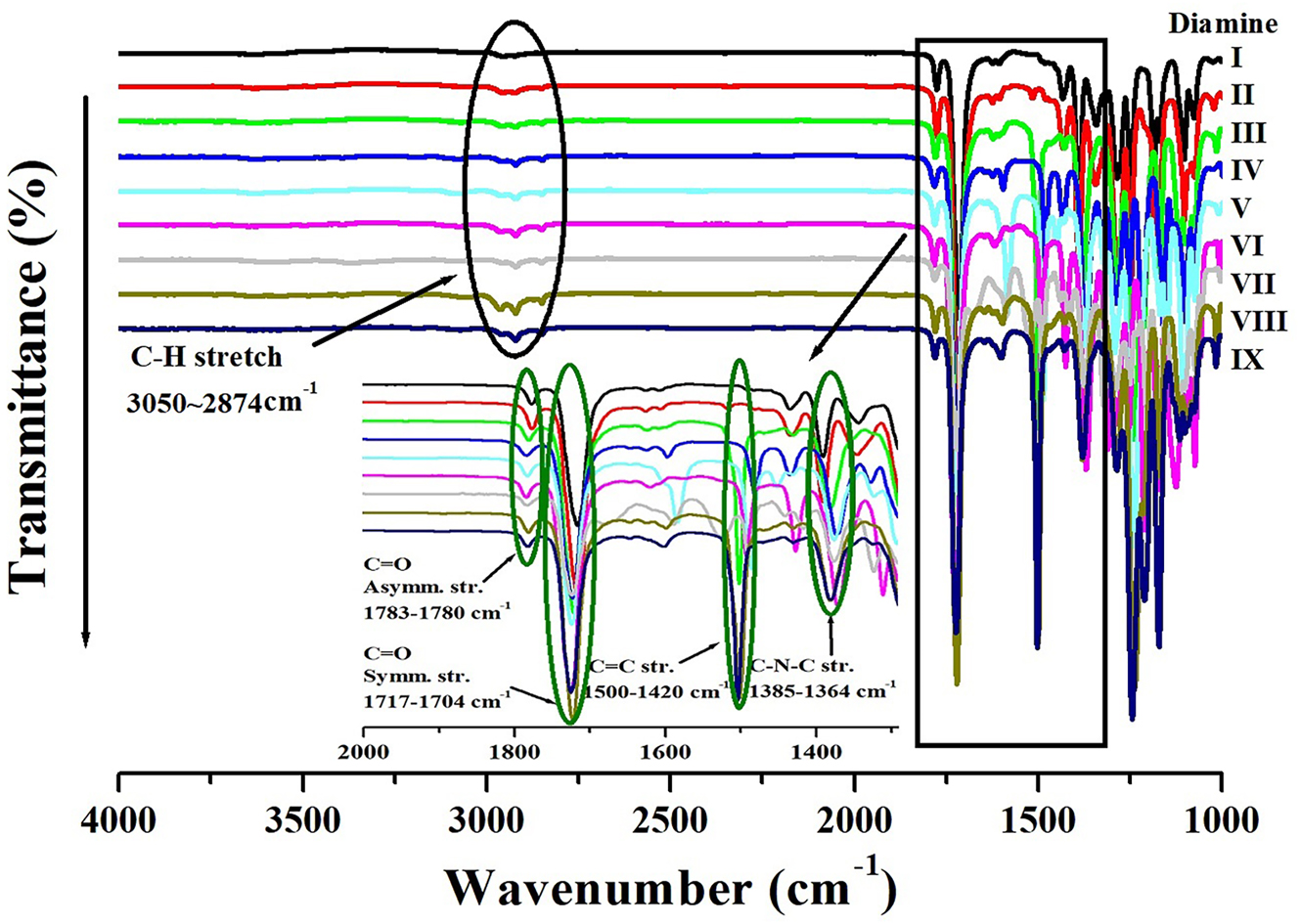

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy (PerkinElmer, L-300, London, UK) was used to confirm the imidization of CPI by identifying characteristic functional groups in the range of 4,000–1,000 cm−1.

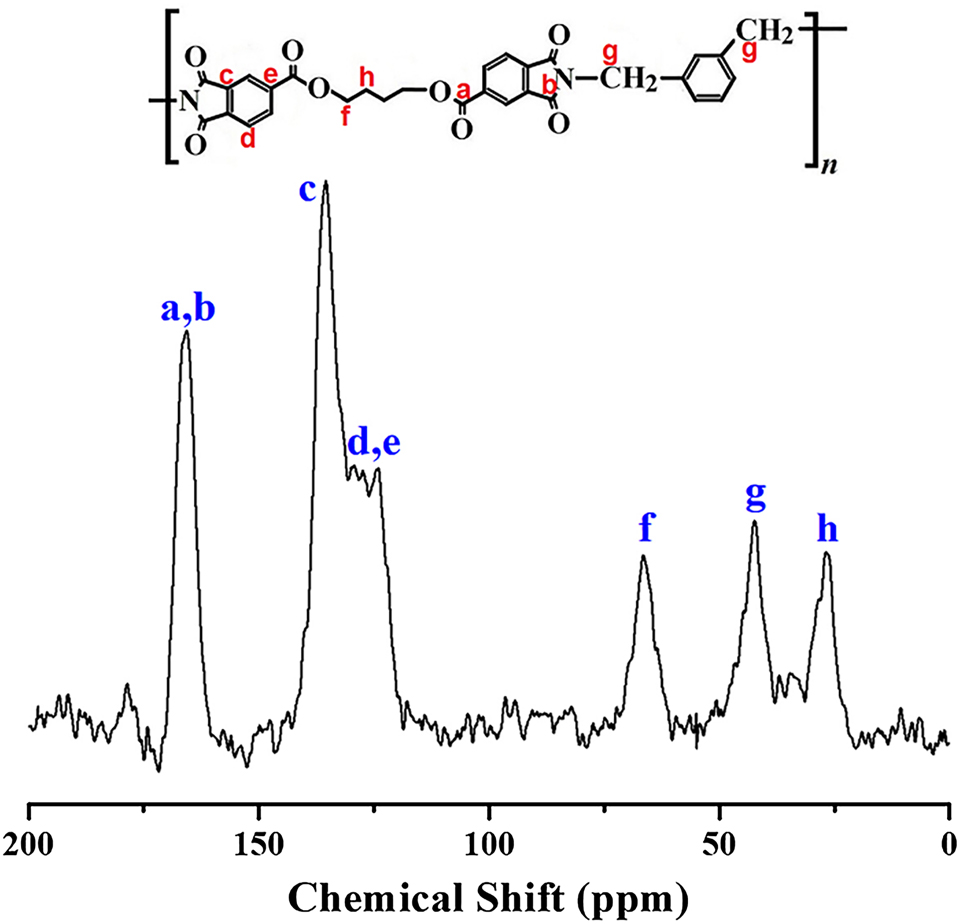

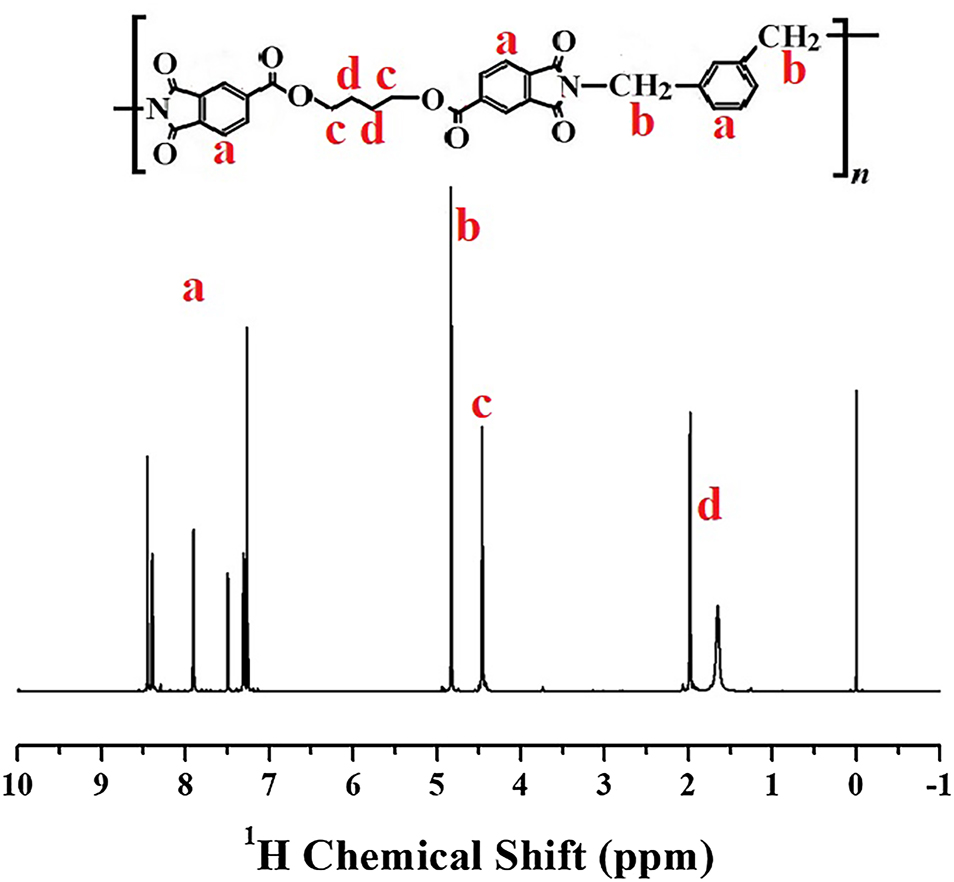

The 1H and 13C magic angle spinning (MAS) nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded at 850 MHz and 125.75 MHz, respectively, on a Bruker spectrometer (Germany) at the Laboratory of NMR, NCIRF, Seoul National University. The 1H and 13C chemical shifts were referenced to tetramethylsilane (TMS), and the 1H NMR experiment was performed using CDCl3 as the solvent.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, NETZSCH 200F3, Berlin, Germany), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and derivative thermogravimetry (DTG) (TA Instruments Q-500, New Castle, USA) were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere with heating and cooling rates of 10 °C min−1. The coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) was measured using a thermomechanical analyzer (TMA, TA Instruments TMA2940, Seiko, Tokyo, Japan) under a constant load of 0.1 N and a heating rate of 10 °C min−1.

Tensile properties were evaluated using a universal testing machine (UTM, Shimadzu AG-50KNX, Japan) with a crosshead speed of 5.00 mm min−1. Each film was tested at least ten times. Outliers were excluded from the dataset, and the average of the remaining values was reported. Experimental error margins were maintained within ±1 MPa for tensile strength and ±0.05 GPa for initial modulus.

The yellowness index (YI) was measured using a spectrophotometer (KONICA MINOLTA CM-3600d, Tokyo, Japan). Ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectroscopy (SHIMADZU UV-3600, Tokyo, Japan) was used to determine the cut-off wavelength (λ 0) and optical transmittance at 500 nm (500 nmtrans). To ensure consistency, all CPI films were prepared with a uniform thickness of 42–46 μm.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 FT-IR, 13C MAS NMR, and 1H NMR, analysis

CPIs were synthesized from a single dianhydride, BU-DA, and nine different diamine monomers, as illustrated in Scheme 1. FT-IR spectra of the resulting CPI films are presented in Figure 1. A separate inset was incorporated into Figure 1 to provide a more detailed view of the spectral range between 2000 and 1,300 cm−1. The absorption bands observed at 3,050–2,874 cm−1 correspond to the C–H stretching vibrations originating from aliphatic and aromatic moieties, reflecting the structural characteristics of the aliphatic and aromatic rings within the main chain. In addition, the strong absorption peaks appearing at 1783–1780 cm−1 and 1717–1704 cm−1 are assigned to the characteristic C=O stretching vibrations of the imide ring, corresponding to the asymmetric and symmetric modes, respectively. The peaks in the range of 1,500–1,420 cm−1 are attributed to the C=C stretching vibrations of the aromatic rings, indicating that the synthesized polymers retain the aromatic backbone structure. Finally, the absorptions observed at 1,385–1,364 cm−1 are assigned to the C–N–C stretching vibrations within the imide ring, which represent a typical characteristic band confirming the formation of polyimide. These results clearly demonstrate that the synthesized CPI films possess the intended chemical structure and that successful cyclization reactions were achieved in all compositions [30].

FT-IR spectra of various CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

Further confirmation of successful CPI formation was obtained by solid-state 13C MAS NMR analysis. Representative spectra of CPI structures I, IV, and VII are shown in Figure 2. In structure I, both the ester carbon (a) and imide carbon (b) were observed at 166.03 ppm. Aromatic ring carbons (c, d, e) appeared at 135.68, 129.65, and 124.56 ppm, respectively. The carbon of the alkyl group adjacent to the ester oxygen (f) was found at 66.45 ppm, while the central aliphatic methylene group (h) appeared at 26.77 ppm. The methylene group adjacent to the aromatic ring (g) gave a signal at 42.18 ppm. These results, along with the FT-IR data, confirm the successful synthesis of the CPI structures [31]. The full NMR spectra of structures IV and VII are provided in the Supplementary Figure I.

13C NMR spectrum of structure I based on BU-DA monomer.

Among the nine synthesized CPIs, the 1H NMR spectrum of Structure I (Figure 3) shows proton (1H) signals consistent with the proposed CPI structure, while the spectra of the remaining CPIs are provided in Supplementary Figure II. The aromatic protons adjacent to the imide ring (a) appeared at 7.1–8.5 ppm due to the strong deshielding effect of the carbonyl groups. The methylene protons bonded to the imide nitrogen (b) were observed at 4.7–4.9 ppm, reflecting the influence of the electronegative nitrogen and neighboring carbonyls. The protons adjacent to oxygen or carbonyl groups (c) resonated at 4.3–4.6 ppm. Finally, the aliphatic protons (d) appeared as broad multiplets at 1.5–2.2 ppm, consistent with shielding in the aliphatic environment. These assignments confirm that the proton environments are in good agreement with the designed CPI structure [31].

1H NMR spectrum of structure I based on BU-DA monomer.

3.2 Thermal properties

Since CPI is generally amorphous, it does not exhibit a melting point (T m ) detectable by DSC [32]. Instead, the primary thermal characteristic of interest is the glass transition temperature (T g ), which is highly sensitive to monomer structure, chain flexibility, bulky substituents, free volume, and inter- and intramolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding [33].

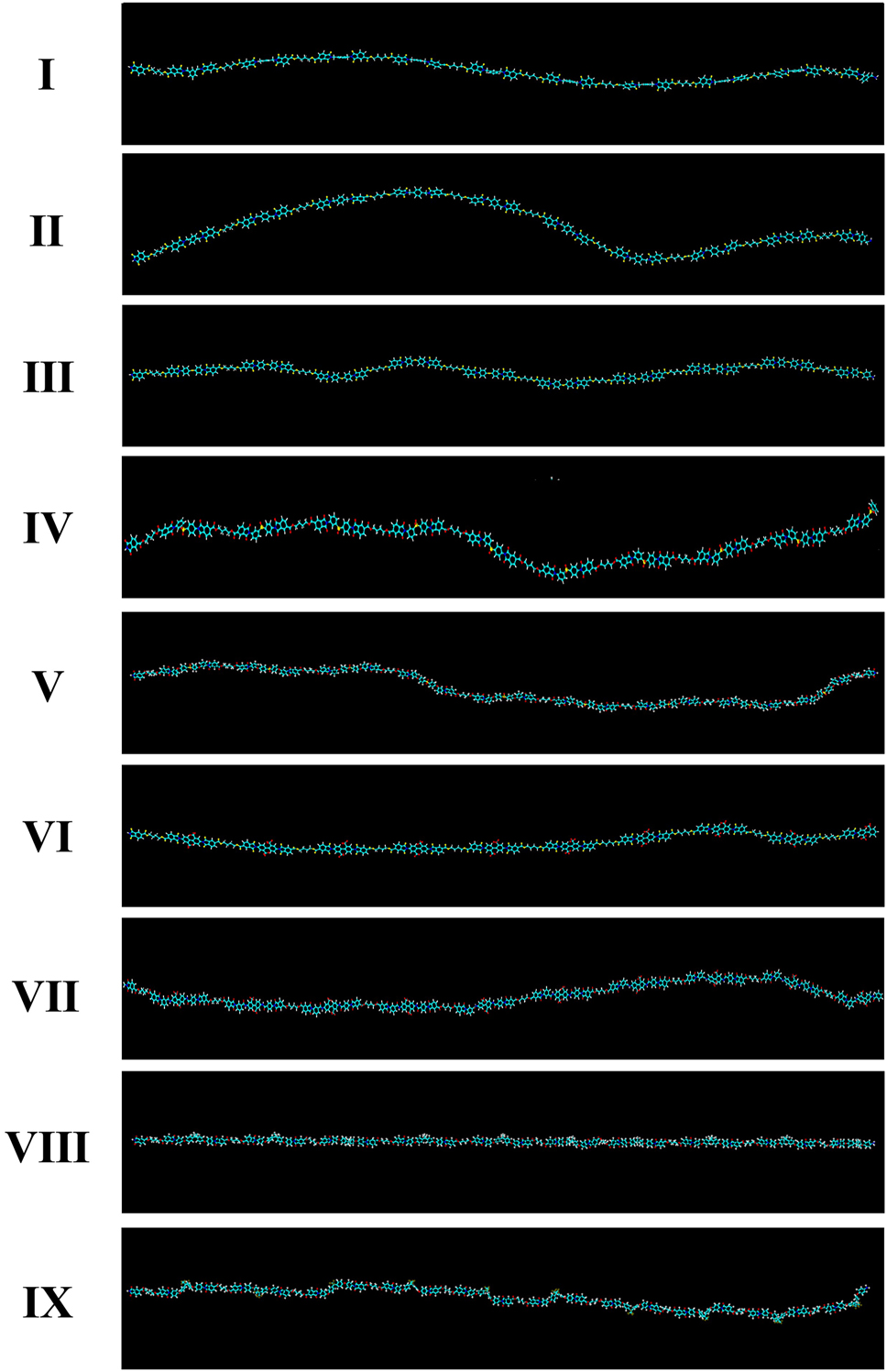

The measured T g values of the nine CPI films are summarized in Table 2, and their proposed 3D polymer structures are illustrated in Figure 4. CPI structures I and II showed the lowest T g values (112 °C and 130 °C, respectively), attributed to the presence of flexible alkyl groups and the bent m-substitution in structure I. Structure III, containing an ether linkage allowing free rotation, exhibited a slightly higher T g of 146 °C. The relatively low T g values of structures I–III may also be due to their lower aromatic content, resulting in reduced rigidity.

Thermal properties of CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

| Diamine | T g (°C) | T D ia (°C) | wt R 600b (%) | CTEc (ppm/°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ⅰ | 112 | 346 | 37 | 57.7 |

| Ⅱ | 130 | 368 | 36 | 55.7 |

| Ⅲ | 146 | 365 | 59 | 52.9 |

| Ⅳ | 149 | 367 | 59 | 49.0 |

| Ⅴ | 157 | 370 | 48 | 48.6 |

| Ⅵ | 165 | 370 | 55 | 56.3 |

| Ⅶ | 171 | 378 | 61 | 52.1 |

| Ⅷ | 154 | 382 | 64 | 56.6 |

| Ⅸ | 160 | 379 | 48 | 58.8 |

-

aInitial decomposition temperature at 2 % weight loss. bWeight residue at 600 °C. cCoefficient of thermal expansion for 2nd heating is 30∼100 °C.

Comparison of the CPI three-dimensional chemical structures based on BU-DA monomer.

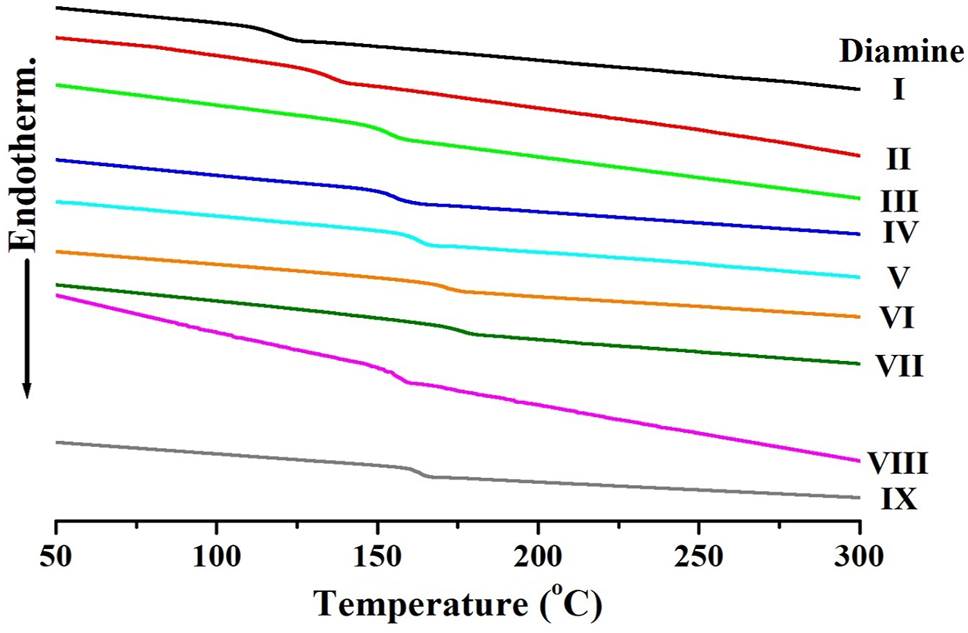

Structures IV and V, which incorporate the bulky and electron-withdrawing –SO2– group, showed T g values of 149 °C and 157 °C, respectively. The presence of sulfone groups introduces steric hindrance that restricts segmental motion. The higher T g of structure V compared to structure IV is attributed to its increased aromatic content. Structures VI, VII, and IX exhibited relatively high T g values (160–171 °C) due to reduced segmental mobility from the bulky –CF3 substituents [34], 35]. Structure VII showed the highest T g (171 °C), likely due to the presence of amide groups capable of forming intermolecular hydrogen bonds, which further restrict chain motion and increase the thermal energy required for transition [36], 37]. In contrast, structure VIII displayed a comparatively lower T g (154 °C), despite its bulky substituents, because of the flexibility imparted by alkyl groups [38]. In the case of CPIs, the T g is generally lower compared to that of conventional aromatic PIs. This tendency can be attributed to the specific structural modifications introduced to suppress CTC formation, which is essential for achieving optical transparency. For instance, the incorporation of flexible linkages such as ether bonds (–O–) or bulky substituents including –CF3 and –C(CF3)2– not only reduces intermolecular interactions but also decreases chain rigidity. These structural features increase the free volume and enhance segmental mobility, thereby lowering the thermal energy required for the glass transition. Consequently, while CPIs exhibit excellent optical transparency by minimizing intermolecular electronic interactions, this design strategy inevitably compromises chain stiffness, leading to a reduced T g relative to traditional aromatic polyimides [39], 40]. Figure 5 displays the DSC thermograms of the CPI films.

DSC thermograms of various CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

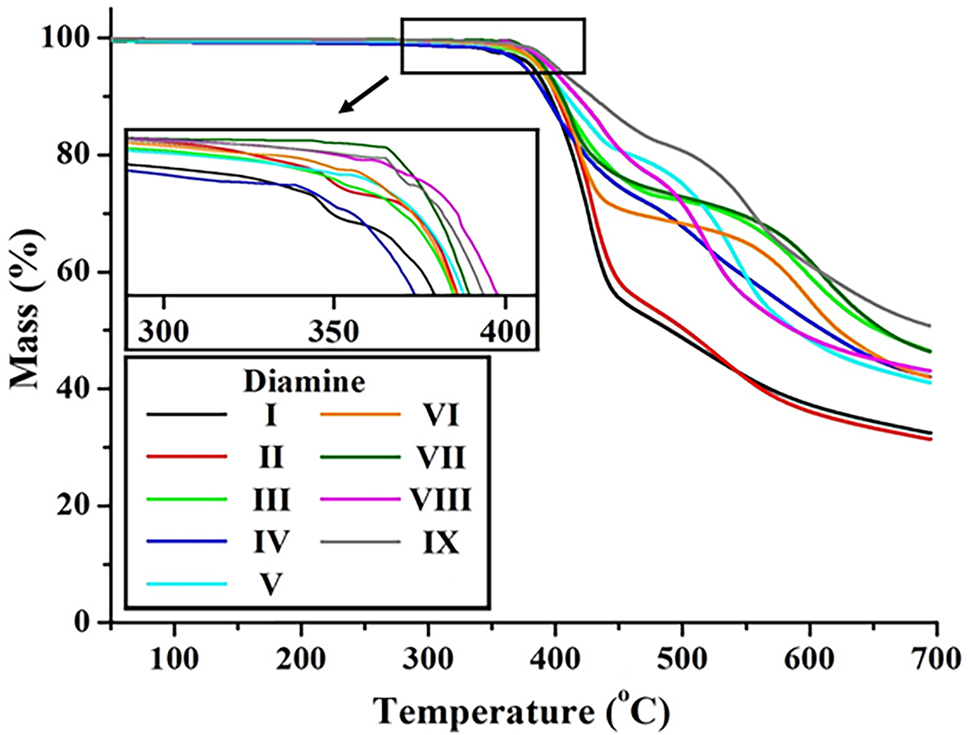

Thermal stability was further assessed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and the initial decomposition temperatures (T D i ) and residual weights at 600 °C (wt R 600 ) are summarized in Table 2 and shown in Figure 6. T D i values ranged from 346 °C to 382 °C. Structure I exhibited the lowest T D i (346 °C), likely due to the thermally unstable m-linked alkyl chains [41]. Structures II to IV, with para-(p-) alkyl, ether, and m-sulfone linkages, respectively, showed moderate stability (T D i = 365–368 °C), attributed to bent configurations that limit close chain packing and intermolecular interactions.

TGA thermograms of various CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

Structures V–IX, which feature thermally robust benzene rings and fluorinated substituents, exhibited higher T D i values (370–382 °C), indicating improved thermal stability [42]. Their linear configurations promote effective molecular packing and reinforce interchain interactions, enhancing thermal endurance [43]. The reason why the T D i of CPIs is lower than that of conventional aromatic polyimides is primarily related to the structural modifications introduced to suppress CTC formation. While these modifications improve optical transparency, they inevitably weaken the intermolecular interactions that typically enhance thermal stability. Moreover, the incorporation of flexible ether linkages, alkyl substituents, and bulky moieties such as –CF3 reduces the overall bond dissociation energy of the polymer backbone, thereby creating thermally weaker sites that promote earlier thermal degradation. In addition, the increased free volume generated by bulky substituents decreases chain packing density, rendering the polymer matrix more susceptible to the onset of decomposition. Consequently, CPIs exhibit a lower T D i compared to traditional polyimides, despite maintaining sufficient thermal stability for practical applications. Residual weights at 600 °C (wt R 600 ) for these structures generally ranged between 50 % and 64 %, whereas structures I and II, which included thermally labile alkyl groups, showed significantly lower residue values (36–37 %).

DTG analysis provides the rate of weight loss as a function of temperature, thereby offering more detailed insight into the thermal degradation behavior than TGA alone. In particular, for CPIs exhibiting multi-step degradation, the DTG curves clearly reveal the maximum degradation rate temperature (T max) for each stage, which can be correlated with the decomposition of specific structural units such as imide, ether, or sulfone moieties. Furthermore, DTG enables precise identification of the onset (T onset) and termination (Tend) of degradation, allowing a direct comparison of how additives, fillers, or copolymer compositions affect the decomposition process. Figure 7 shows the DTG curves of nine CPI films prepared from different diamines. All samples exhibited major degradation peaks in the range of 450–550 °C, which are associated with the thermal decomposition of the imide rings and aromatic backbones. However, the position and intensity of the T max varied depending on the diamine structure. CPIs containing rigid aromatic units or strongly electron-withdrawing substituents displayed higher T max values, reflecting enhanced thermal stability. In contrast, CPIs incorporating more flexible chain segments exhibited relatively lower T max, indicating reduced resistance to thermal decomposition. These results demonstrate that DTG analysis provides more detailed information on the stepwise degradation behavior compared with TGA alone, enabling clear identification of structural effects on the thermal stability of CPI films. The TGA/DTG results of the CPI films prepared with various diamines were provided in Supplementary Figure III.

DTG thermograms of various CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

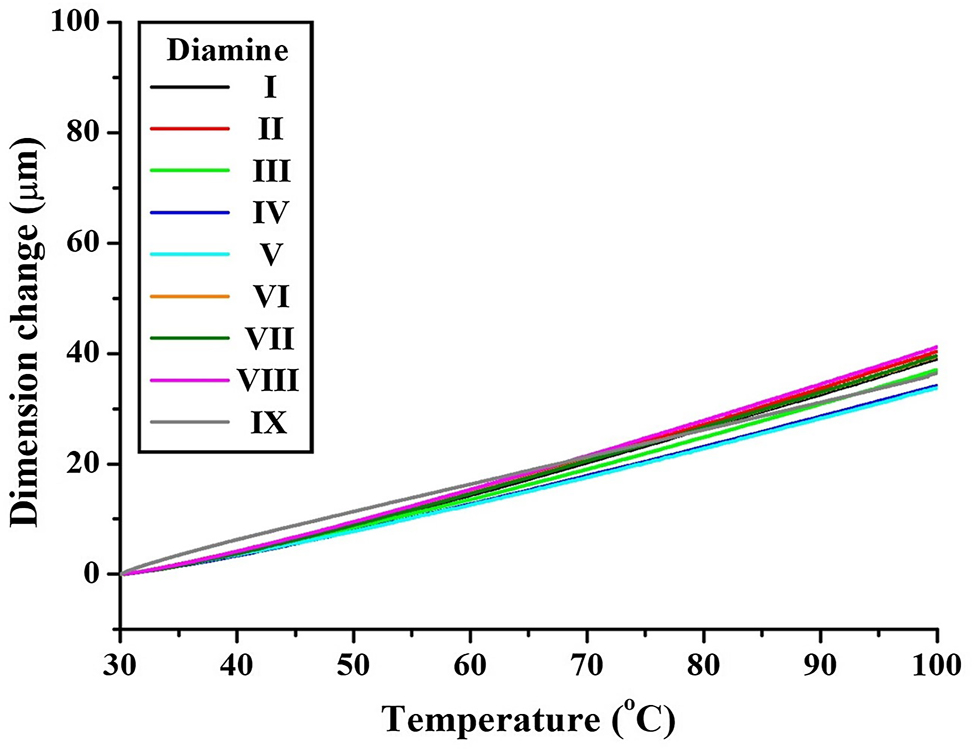

Thermal dimensional stability was evaluated using thermomechanical analysis (TMA). The coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), which reflects the polymer’s tendency to expand upon heating, is sensitive to chain rigidity and aromatic content [44], 45]. Figure 8 and Table 2 show the TMA results. Structures I and II exhibited high CTE values (55.7 and 57.7 ppm °C−1, respectively), due to flexible alkyl content and bent backbones. In contrast, structures IV and V, despite their non-linear chains, showed lower CTE values (48.6 and 49.0 ppm °C−1), attributed to the restricted rotation imparted by the –SO2– moieties. Among the fluorinated structures (VI–IX), structure VII displayed a relatively low CTE (52.1 ppm °C−1), due to the potential formation of hydrogen bonds via the –NH–CO– groups. Structure IX exhibited the highest CTE (58.8 ppm °C−1), which can be explained by the flexible hexafluoropropyl (–C(CF3)2–) substituents, allowing greater chain movement.

TMA thermograms of various CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

3.3 Mechanical properties

The mechanical properties of the CPI films – including ultimate tensile strength, initial modulus, and elongation at break (EB) – were evaluated using a UTM. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Mechanical properties of CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

| Diamine | Ult. Str.a (MPa) | Ini. Mod.b (GPa) | E.B.c (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 63 | 6.81 | 4 |

| II | 61 | 3.09 | 7 |

| III | 54 | 2.57 | 6 |

| IV | 22 | 2.23 | 4 |

| V | 57 | 2.63 | 4 |

| VI | 136 | 5.96 | 7 |

| VII | 92 | 2.87 | 7 |

| VIII | 95 | 4.71 | 10 |

| IX | 95 | 4.27 | 9 |

-

aUltimate tensile strength. bInitial tensile modulus. cElongation at break.

Structures I–III exhibited moderate tensile strengths ranging from 54 to 63 MPa. Structure IV, which incorporates a bulky –SO2– group and a m-substitution, displayed the lowest tensile strength (22 MPa) among all samples. This significant reduction in strength is attributed to its highly bent conformation, which limits effective chain alignment (Figure 4). Conversely, although Structure V also contains a –SO2– moiety, its more linear geometry, facilitated by ether linkages and a higher benzene content, led to a considerably higher tensile strength of 57 MPa. Structures VI–IX demonstrated superior tensile strength values (92–136 MPa), which can be attributed to their relatively linear chain configurations and higher aromatic content. In particular, Structure VI, derived from a simple p-substituted diamine, exhibited the highest tensile strength (136 MPa), attributed to its highly regular and linear 3D molecular conformation that enables effective chain packing.

The initial modulus, reflecting the stiffness of the polymer chain, was strongly influenced by structural rigidity and the presence of rigid aromatic units. As shown in Figure 4, Structure I exhibited the highest modulus (6.81 GPa), likely due to its relatively short and linear backbone. Structures VI, VIII, and IX also showed high modulus values (4.27–5.96 GPa), consistent with their more linear architectures. Although Structure VII exhibited a relatively high tensile strength (92 MPa), its modulus was comparatively lower (2.87 GPa), likely due to its overall bent chain configuration, which reduces stiffness despite the presence of hydrogen bonding interactions via amide linkages.

Overall, Structures VI–IX displayed enhanced mechanical performance, with high tensile strength and stiffness, which can be attributed to tightly packed, linear chains, short repeating units, and intermolecular attractions such as hydrogen bonding [46], 47].

The elongation at break (EB) values for all CPI films ranged consistently from approximately 4 %–10 %, suggesting comparable flexibility across the different structures. The reason why CPIs generally exhibit lower EB compared to conventional aromatic PIs can be attributed to their inherent structural characteristics. To suppress CTC formation and achieve optical transparency, CPIs are often designed with bulky substituents such as –CF3, –C(CF3)2–, or –SO2– groups, which increase chain rigidity and restrict molecular flexibility. This enhanced rigidity limits the ability of polymer chains to undergo plastic deformation during stretching, leading to brittle fracture and a reduced EB. Furthermore, the incorporation of bulky moieties increases free volume and disrupts uniform chain packing, which facilitates localized stress concentration rather than homogeneous chain extension under load. As a consequence, while CPIs maintain excellent thermal stability and optical transparency, they inevitably suffer from lower ductility, as reflected in their reduced EB [40], 48].

3.4 Optical transparency

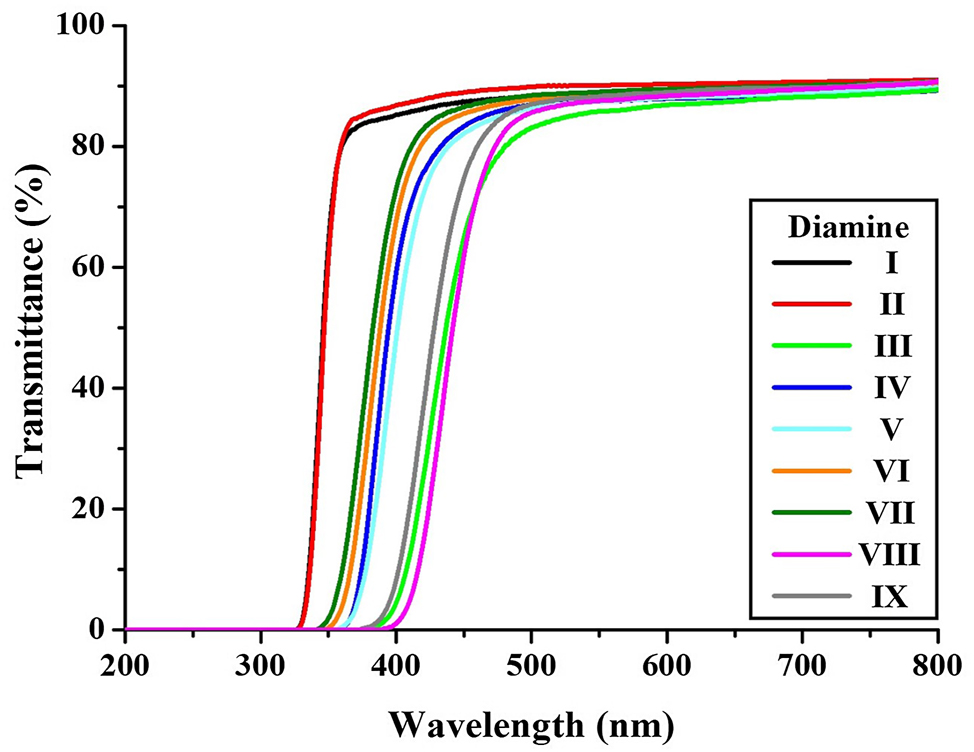

To evaluate the optical transparency of the CPI films, three key parameters were measured: the λ 0, the 500 nmtrans, and the YI. These values reflect the UV absorption onset, visible light transmittance, and visual coloration of the films, respectively [49]. All films were fabricated with a uniform thickness of 42–46 μm to ensure consistent optical comparison.

UV–vis spectra of the CPI films are shown in Figure 9, and the corresponding data are presented in Table 4. The λ 0 values ranged from 328 to 392 nm depending on the diamine monomer used. Structures III, VIII, and IX exhibited relatively high λ 0 values of 381, 392, and 374 nm, respectively. These results suggest increased CTC formation due to their more linear chain conformations. As a consequence, their 500 nmtrans values were slightly lower (81–83 %) compared to the other films. Nevertheless, all films demonstrated visible light transmittance greater than 80 % at 500 nm and transmitted light starting below 400 nm, indicating excellent overall optical transparency.

UV–vis. transmittance of various CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

Optical properties of CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

| Diamine | Thicknessa (μm) | λ 0 b (nm) | 500nmtrans (%) | YIc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ⅰ | 42 | 328 | 88 | <1 (0.1) |

| Ⅱ | 43 | 328 | 89 | <1 (0.2) |

| Ⅲ | 42 | 381 | 83 | 19.3 |

| IV | 44 | 360 | 86 | 4.2 |

| V | 44 | 358 | 86 | 3.6 |

| VI | 45 | 349 | 87 | 2.6 |

| VII | 46 | 343 | 88 | 2.2 |

| VIII | 45 | 392 | 81 | 27.5 |

| IX | 46 | 374 | 82 | 15.7 |

-

aFilm thickness. bCut off wavelength. cYellow index.

Table 4 summarizes the YI values, which were calculated using the ASTM E313-96 and DIN 6167 standards with the equation:

where a and b are constants specific to each method, and X, Y, and Z are the tristimulus values.

Structures I and II exhibited the lowest YI values (both < 1), due to their bent, flexible chain structures, which hinder close chain stacking and CTC formation. Structures IV–VII also showed good optical clarity (YI = 2.2–4.2), attributed to structural distortion and m-substitution effects.

Notably, although Structure VI contains a linear p-substitution, its incorporation of the strongly electron-withdrawing –CF3 group disrupts π-electron delocalization, thereby reducing CTC and lowering YI. In contrast, Structure III retained a relatively linear structure and displayed a significantly higher YI of 19.3. Structures VIII and IX, due to their linear conformations and lack of significant structural distortion, exhibited the highest YI values (27.5 and 15.7, respectively), consistent with increased coloration resulting from CTC formation.

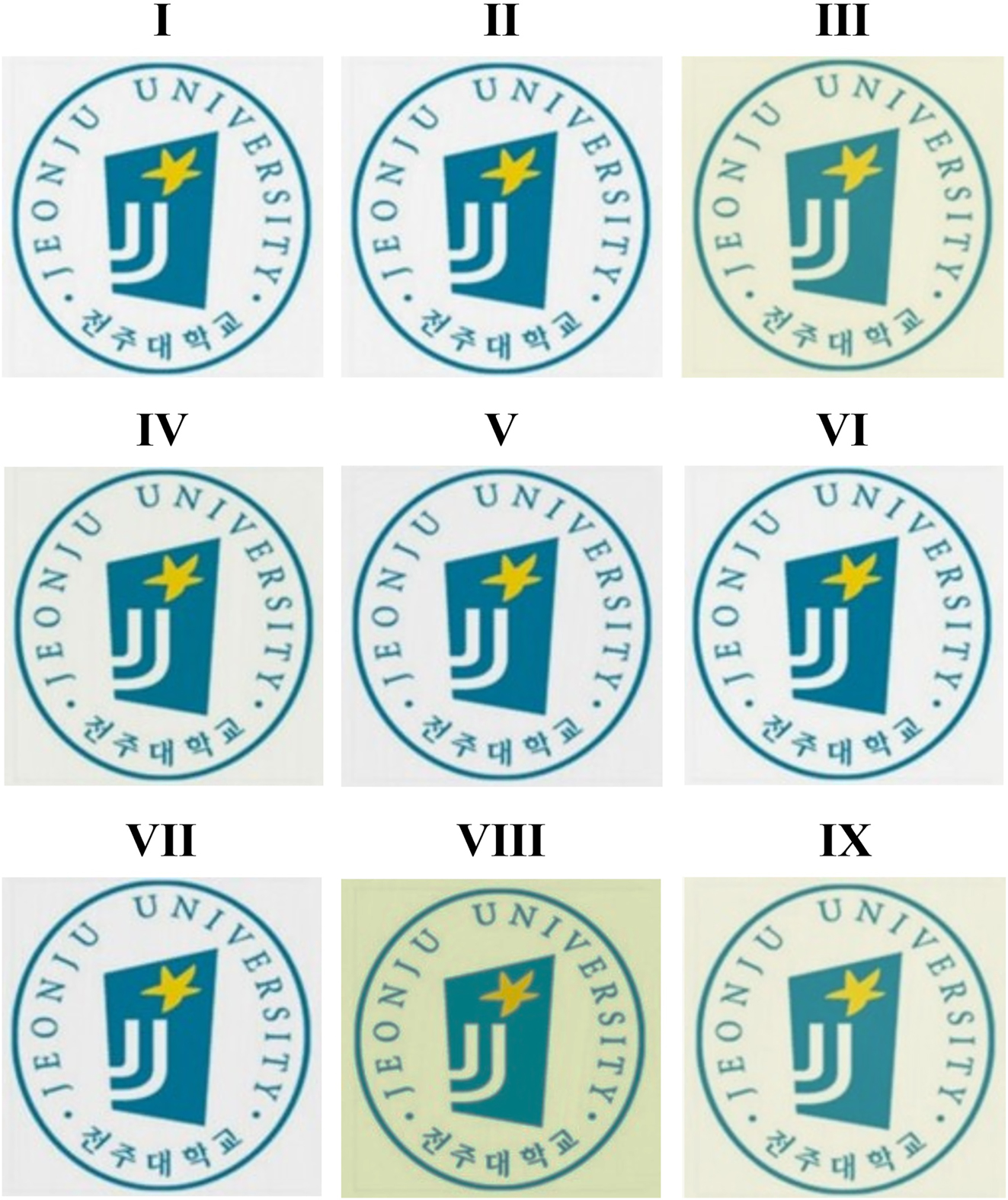

To visually assess transparency, Figure 10 shows images of a printed logo viewed through each CPI film. Despite color variations due to different monomer structures, all films maintained sufficient clarity for easy logo recognition. These differences are consistent with the measured YI values.

Photographs of various CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

3.5 Solubility

Although CPI materials are known for their excellent thermal and chemical stability, their rigid aromatic backbones often lead to poor solubility in conventional solvents [50], 51]. This limitation restricts their processability and application as high-performance polymer films. Therefore, structural modifications that improve solubility without compromising CPI’s desirable properties are of great interest.

In this study, solubility tests were conducted using 12 common solvents, and the results are compiled in Table 5. All CPI films were completely insoluble in polar protic solvents such as ethanol (EtOH) and methanol (MeOH), and only exhibited limited solubility in acetone, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and toluene. However, higher solubility was observed in halogenated solvents such as chloroform (CHCl3) and methylene chloride (CH2Cl2), and in polar aprotic solvents including N,N′-dimethylacetamide (DMAc), N,N′-dimethylformamide (DMF), N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), and tetrahydrofuran (THF).

Solubility tests of CPIs based on BU-DA monomer.

| Diamine | Act | CHCl3 | CH2Cl2 | DMAc | DMF | DMSO | MeOH | EtOH | NMP | Py | THF | Tol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | × | ◎ | ◎ | × | △ | × | × | × | ○ | ◎ | △ | × |

| II | × | ◎ | ◎ | × | × | × | × | × | △ | △ | × | × |

| III | ○ | ◎ | ◎ | ○ | ○ | × | × | × | ○ | ◎ | △ | × |

| IV | △ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | × | × | ○ | ◎ | △ | △ |

| V | △ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | × | × | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | △ |

| VI | △ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | △ | × | × | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | △ |

| VII | ○ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ○ | × | × | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | △ |

| VIII | × | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | × | × | × | ◎ | ◎ | ○ | △ |

| IX | × | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ○ | × | × | ◎ | ◎ | ◎ | ○ |

-

◎: excellent, ○: good, △: poor, ×: very poor. Act: Acetone, DMAc: N,N′-dimethylacetamide, DMF: N,N′-dimethylformamide, DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide, NMP: N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone, Py: Pyridine, THF: tetrahydrofuran. Tol: Toluene.

Structures I–III showed the poorest solubility due to their simple aromatic frameworks and absence of solubilizing substituents. In particular, structures I and II incorporate –CH2– linkages within the main chain. While such alkyl segments may increase chain flexibility, they essentially function as hydrophobic moieties with negligible polarity. This structural feature is unfavorable when dissolution in polar solvents such as DMAc, DMF, or NMP is required. The presence of alkyl groups diminishes the extent of specific intermolecular interactions between the polymer chains and solvent molecules, including hydrogen bonding and dipole–dipole interactions, which are critical to achieving efficient solvation. Consequently, instead of enhancing solubility, the incorporation of –CH2– units suppresses polymer–solvent affinity, thereby leading to a marked reduction in overall solubility [52]. In contrast, Structures IV–IX demonstrated significantly improved solubility. This enhancement is attributed to the presence of bulky groups such as –SO2–, –CF3, and alkyl substituents, which increase free volume and reduce chain packing density, thereby facilitating solvent penetration [53], 54]. Specifically, Structures VIII and IX exhibited excellent solubility across multiple solvents, owing to the incorporation of voluminous –C(CH3)2– (Structure VIII) and –C(CF3)2– (Structure IX) substituents. These groups improve solvent–polymer interactions and enhance accessibility to solvent molecules.

4 Conclusions

In this study, a series of PAA precursors were synthesized by reacting nine different diamine monomers – each incorporating various substituents such as alkyl, ether (–O–), sulfone (–SO2–), trifluoromethyl (–CF3), and methyl (–CH3) groups – with a dianhydride containing a flexible 1,4-butanediol unit in the polymer backbone. The resulting PAAs, composed of either m- or p-substituted structures, were converted into colorless and transparent polyimide (CPI) films via thermal imidization under controlled conditions. The thermomechanical, optical, and solubility properties of the CPI films were systematically investigated to understand the influence of diamine monomer structures.

The structure–property relationships of the synthesized CPIs revealed clear trends: CPI films with a high content of rigid and thermally stable aromatic structures demonstrated superior thermal and mechanical properties. In contrast, the introduction of bulky or electron-withdrawing substituents into the diamine units resulted in more distorted and flexible polymer backbones, leading to significantly improved optical transparency and solubility. Notably, the CPI films derived from relatively simple and slightly bent diamine structures exhibited excellent optical clarity, with YI values below 1 – comparable to that of conventional optical glass.

Overall, the nine newly developed CPI films exhibited the dual characteristics of high-performance engineering plastics and exceptional optical transparency. Moreover, their potential for scalable and cost-effective production highlights their suitability for diverse applications requiring both mechanical robustness and visual clarity, including flexible display substrates, solar panel coatings, and next-generation rollable or wearable electronic devices. These findings demonstrate that the CPIs reported in this work are promising candidates as polymeric alternatives to glass in advanced optoelectronic and flexible device technologies.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Jeonbuk RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Jeonbuk State, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-13-JJU).

-

Funding information: This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Jeonbuk RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Jeonbuk State, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-13-JJU).

-

Author contributions: J.-H. Chang designed the project and wrote the manuscript. A.R. Lim reviewed and data analyzed. Y.S. Shin prepared the samples and participated in the data analysis. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Gouzman, I, Grossman, E, Verker, R, Atar, N, Bolker, A, Eliaz, N. Advances in polyimide-based materials for space applications. Adv Mater 2019;31:1807738. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201807738.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

2. Chen, Y, Liu, Y, Min, Y. Innovative polyimide modifications for aerospace and optoelectronic applications: synergistic enhancements in thermal, mechanical, and optical properties. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2025;17:16016–26. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c21102.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

3. Jia, C, Li, Z, Wan, Z, Jiang, Z, Xue, J, Shi, J, et al.. Ultra-thin perovskite solar cells with high specific power density based on colorless polyimide substrates. Nano Energy 2024;131:110259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2024.110259.Search in Google Scholar

4. Wang, Y, Chen, Q, Zhang, G, Xiao, C, Wei, Y, Li, W. Ultrathin flexible transparent composite electrode via semi-embedding silver nanowires in a colorless polyimide for high-performance ultraflexible organic solar cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2022;14:5699–708. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c18866.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

5. Grabowska, A, Fuentes Pineda, R, Spinelli, P, Soto Pérez, G, Vinocour Pacheco, FA, Babu, V. Development of lightweight and flexible perovskite solar cells on ultrathin colorless polyimide foils. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024;16:48676–84. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c11355.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

6. Li, H, Li, J, Chu, W, Lin, J, He, P, Fan, W. Ultrahigh absorption dominant EMI shielding polyimide composites with enhanced piezoelectric properties. Compos Sci Technol 2024;257:id. 110820. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2024.110820.Search in Google Scholar

7. Zhou, L, Shen, D, Gou, P, He, L, Xie, F, He, C, et al.. Anisotropic high-strength polyimide-based electromagnetic interference shielding foam based on cation-π interaction. Chem Eng J 2023;477:id. 146992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.146992.Search in Google Scholar

8. Rusu, R-D, Constantin, CP, Drobota, M, Gradinaru, LM, Butnaru, M, Pislaru, M. Polyimide films tailored by UV irradiation: surface evaluation and structure-properties relationship. Polym Degrad Stabil 2020;177:id. 109182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2020.109182.Search in Google Scholar

9. Wu, Z, He, J, Yang, H, Yang, S. Progress in aromatic polyimide films for electronic applications: preparation structure and properties. Polymers 2022;14:id. 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14061269.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

10. Zuo, HT, Gan, F, Dong, J, Zhang, P, Zhao, X, Zhang, QH. Highly transparent and colorless polyimide film with low dielectric constant by introducing meta-substituted structure and trifluoromethyl groups. Chin J Polym Sci 2021;39:455–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10118-021-2514-2.Search in Google Scholar

11. Wen, Q, Tang, A, Chen, C, Liu, Y, Xiao, C, Tan, J, et al.. Impact of backbone amide substitution at the meta- and para- positions on the gas barrier properties of polyimide. Materials 2021;14:id. 2097. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14092097.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

12. Li, B, Jiang, S, Yu, S, Chen, Y, Tang, X, Wu, X, et al.. Co-polyimide aerogel using aromatic monomers and aliphatic monomers as mixing diamines. J Sol Gel Sci Technol 2018;88:386–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10971-018-4800-1.Search in Google Scholar

13. Zhang, H, Chen, L, Xin, H, Zhang, J. Performance regulation and application evaluation of colorless polyimide for flexible displays. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2025;17:17358–67. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c22198.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

14. Zhu, H, Su, Y, Li, J, Ding, Y, Li, M, Li, W. Highly rigid and functional polyimides based on noncoplanar benzimidazolone diamines and their photolithography application. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2024;6:6130–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.4c00856.Search in Google Scholar

15. Pu, C, Liu, F, Xu, H, Chen, G, Tian, G, Qi, S, et al.. Molecular dynamics study on the mechanism of poly(amic acid) chemical structure on thermal imidization process and polyimide architecture. Mater Today Chem 2023;33:id. 101679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtchem.2023.101679.Search in Google Scholar

16. Ma, P, Dai, C, Liu, H. High performance polyimide films containing benzimidazole moieties for thin film solar cells. E-Polymers 2019;19:555–62. https://doi.org/10.1515/epoly-2019-0059.Search in Google Scholar

17. Wu, D, Yi, C, Wang, Y, Qi, S, Yang, B. Preparation and gas permeation of crown ether-containing co-polyimide with enhanced CO2 selectivity. J Membr Sci 2018;551:191–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2018.01.028.Search in Google Scholar

18. Kaya, I, Kamaci, M. Synthesis, optical, and thermal properties of polyimides containing flexible ether linkage. J Appl Polym Sci 2018;135:id. 46573.10.1002/app.46573Search in Google Scholar

19. Li, H, Wang, X, Gong, Y, Zhao, H, Liu, Z, Tao, L, et al.. Polyimide/crown ether composite film with low dielectric constant and low dielectric loss for high signal transmission. RSC Adv 2023;13:7585–96. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ra07043j.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

20. Mushtaq, N, Xing, J, Li, X, Chen, G, Fang, X. Synthesis and comparative study of high Tg and colorless polyamide – imides with different amide-to-imide ratio. J Polym Sci 2024;62:2014–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/pol.20230948.Search in Google Scholar

21. Novakov, IA, Orlinson, BS, Zavialov, DV, Mednikov, SV, Gurevich, LM, Bogdanov, AI, et al.. A. Optically transparent (co) polyimides based on alicyclic diamines with improved dielectric properties. Russ Chem Bull 2023;72:1366–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11172-023-3911-1.Search in Google Scholar

22. Yu, S, Zhou, J, Xu, A, Lao, J, Luo, H, Chen, S. The scalable and high performance polyimide dielectrics containing alicyclic structures for high-temperature capacitive energy storage. Chem Eng J 2023;469:id. 13803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2023.143803.Search in Google Scholar

23. Narzary, BB, Baker, BC, Yadav, N, D’Elia, V, Faul, CF. Crosslinked porous polyimides: structure, properties and applications. Polym Chem 2021;12:6494–514. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1py00997d.Search in Google Scholar

24. Zhuang, Y, Seong, JG, Lee, YM. Polyimides containing aliphatic/alicyclic segments in the main chains. Prog Polym Sci 2019;92:35–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2019.01.004.Search in Google Scholar

25. Wang, W, Zhou, G, Wang, Y, Yan, B, Sun, B, Duan, S, et al.. Multiphotoconductance levels of the organic semiconductor of polyimide-based memristor induced by interface charges. J Phys Chem Lett 2022;13:9941–9. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c02651.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

26. Zhang, T, Li, P, Chen, N, Su, J, Yang, Z, Wang, D, et al.. Flexible transparent layered metal oxides for organic devices. J Mater Chem C 2025;13:9276–84. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4tc05338a.Search in Google Scholar

27. Lu, H, Yuan, J, Chen, Y, Xiang, S, Lu, Q. Super impact‐resistant, high‐strength, scratch‐resistant, and foldable glass‐like film for the next generation of ultra‐thin flexible display. Flex Mat 2025;1:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/flm2.50.Search in Google Scholar

28. Zhang, H, Chen, L, Xin, H, Zhang, J. Performance regulation and application evaluation of colorless polyimide for flexible displays. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2025;17:17358–67. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.4c22198.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

29. Wang, X, Xu, C, Wang, C, Zhao, X. Large π‐Conjugated structure strategy for optimizing polyimide film‐forming properties and developing gas fluorescence sensors. J Appl Polym Sci 2025;142:id. e56591. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.56591.Search in Google Scholar

30. Pavia, DL, Lampman, GM, Kriz, GS. Introduction to spectroscopy. Saunders College Pub., New York, USA; 2008:14–95 pp. Chap. 2.Search in Google Scholar

31. Pavia, DL, Lampman, GM, Kriz, GS. Introduction to spectroscopy. Saunders College Pub., New York, USA; 2008:146-83 pp. Chap. 4.Search in Google Scholar

32. Calosi, M, D’Iorio, A, Buratti, E, Cortesi, R, Franco, S, Angelini, R, et al.. Preparation of high-solid PLA waterborne dispersions with PEG-PLA-PEG block copolymer as surfactant and their use as hydrophobic coating on paper. Prog Org Coating 2024;193:id. 108541.10.1016/j.porgcoat.2024.108541Search in Google Scholar

33. Mushtaq, N, Zhang, Y, Nazir, M, Tan, L, Chen, G, Fang, X. Ultra-high Tg colorless polyimide film with balanced optical retardation and coefficient of thermal expansion for flexible display. Polymer 2025;321:id. 128085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2025.128085.Search in Google Scholar

34. Zuo, P, Li, J, Chen, D, Nie, L, Gao, L, Lin, J, et al.. Scalable co-cured polyimide/poly (p-phenylene benzobisoxazole) all-organic composites enabling improved energy storage density, low leakage current and long-term cycling stability. Mater Horiz 2024;11:271–82. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3mh01479g.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

35. Yan, C, Zhou, J, Xu, A, Long, H, Luo, H, Chen, S. Sharply improved electrical insulation of polyimide dielectrics at elevated temperatures by charge reassignment engineering. Small 2025;21:id. 2501050. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.202501050.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

36. Westwood, MM, Schroeder, BC. Solidifying the role of hydrogen bonds in conjugated polymers. J Mater Chem C 2024;12:19017–29. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4tc03666b.Search in Google Scholar

37. Qingpei, W, Thompson, BC. Control of properties through hydrogen bonding interactions in conjugated polymers. Adv Sci 2024;11:id. e2305356.10.1002/advs.202305356Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

38. Lee, J, Kwak, G. Extremely softened polyimides with long, branched alkyl side chains: shape memory characteristics and anticounterfeiting application. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2025;7:7526–34. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsapm.5c01168.Search in Google Scholar

39. Feng, J, Liu, H, Yang, S, Zhou, Y, Zhang, X, Wang, X. Revealing molecular mechanisms of colorless transparent polyimide films with high thermal stability, superior mechanical and dielectric properties. Polymer 2023;266:id. 125651.10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2023.110294Search in Google Scholar

40. Na, Y, Kang, S, Kwac, LK, Kim, HG, Chang, JH. Monomer dependence of colorless and transparent polyimide films: thermomechanical properties, optical transparency, and solubility. ACS Omega 2024;9:12195–203. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.4c00175.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

41. Sawada, R, Yajima, K, Takao, A, Liu, H, Ando, S. Thermal, optical, and dielectric properties of bio-based polyimides derived from an isosorbide-containing dianhydride and diamines with long alkyl chains. J Photopolym Sci Technol 2024;37:507–16. https://doi.org/10.2494/photopolymer.37.507.Search in Google Scholar

42. Zhang, Z, Ren, X, Huo, G, Zhou, X, Chen, H, Zhang, H, et al.. Effect of free volume and hydrophilicity on dehumidification performance of 6FDA-Based polyimide membranes. J Membr Sci 2024;705:id. 122876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.memsci.2024.122876.Search in Google Scholar

43. Jia, Y, Zhai, L, Mo, S, Liu, Y, Liu, LX, Du, XY, et al.. Effect of low-temperature imidization on properties and aggregation structures of polyimide films with different rigidity. Chin J Polym Sci 2024;42:1134–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10118-024-3137-1.Search in Google Scholar

44. Ran, Z, Yang, M, Wang, R, Li, J, Li, M, Meng, L, et al.. Surface-gradient-structured polymer films with restricted thermal expansion for high-temperature capacitive energy storage. Energy Storage Mater 2025;74:id. 103952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2024.103952.Search in Google Scholar

45. Zha, JW, Wang, F, Wan, B. Polymer composites with high thermal conductivity: theory, simulation, structure and interfacial regulation. Prog Mater Sci 2024;148:id. 101362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2024.101362.Search in Google Scholar

46. Sun, Q, Tian, K, Liu, S, Zhu, Q, Zheng, S, Chen, J, et al.. A combination of “Inner-Outer skeleton” strategy to improve the mechanical properties and heat resistance of polyimide composite aerogels as composite sandwich structures for space vehicles. Compos Sci Technol 2024;252:id. 110620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compscitech.2024.110620.Search in Google Scholar

47. Kamalov, A, Vaganov, G, Simonova, M, Kraft, V, Nesterova, A, Saprykina, N, et al.. Effect of the molar mass of polyimide based on pyromellitic dianhydride and 4, 4′‐oxydianiline on dielectric and mechanical properties of nonwoven oriented polyimide materials. Polym Eng Sci 2024;64:2894–904. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.26733.Search in Google Scholar

48. Shi, Y, Hu, J, Li, X, Jian, J, Jiang, L, Yin, C, et al.. High comprehensive properties of colorless transparent polyimide films derived from fluorine-containing and ether-containing dianhydride. RSC Adv 2024;14:32613–23. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ra05505e.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

49. Na, C, Kwac, LK, Kim, HG, Chang, JH. Effect of organoclay on the physical properties of colorless and transparent copoly(amide imide) nanocomposites. RSC Adv 2024;14:9062–71. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3ra08605d.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

50. Liu, YY, Wang, WK, Wu, DY. Synthetic strategies for highly transparent and colorless polyimide film. J Appl Polym Sci 2022;139:id. e52604. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.52604.Search in Google Scholar

51. Yi, C, Li, W, Shi, S, He, K, Ma, P, Chen, M, et al.. High-temperature-resistant and colorless polyimide: preparations, properties, and applications. Sol Energy 2020;195:340–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.11.048.Search in Google Scholar

52. Mabesoone, MFJ, MacLaren, CJ, Weder, C, Meijer, EW. Solute–solvent interactions in modern physical organic chemistry. J Am Chem Soc 2020;142:17721–9.10.1021/jacs.0c09293Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

53. Zhang, H, Xiang, Z, Fang, P, Zang, S, Zheng, Z. Soluble polyimide-modified epoxy resin with enhanced comprehensive performances. J Appl Polym Sci 2025;142:id. e57400. https://doi.org/10.1002/app.57400.Search in Google Scholar

54. Zheng, B, Li, J, Li, W, Zhang, S, Lei, H. Soluble photosensitive polyimide precursor with bisphenol A framework: synthesis and characterization. Polymers 2025;17:id. 1428. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17111428.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

Supplementary Material

This article contains supplementary material (https://doi.org/10.1515/rams-2025-0190).

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods