Abstract

Ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS) is a widely used precursor in the development of geopolymer concrete (GPC) due to its high reactivity. While nanomaterials have been explored for enhancing GPC properties, the specific influence of nano-Al2O3 (NA) on the mechanical and durability performance of GGBS-based GPC remains underexplored. This study investigates the effect of NA at dosages of 1, 2, and 3% as a partial replacement of GGBS, aiming to optimize the strength and durability of GPC. The highest strength was achieved with 2% NA, yielding compressive, split tensile, and flexural strengths of 57.36, 5.81, and 5.59 MPa, respectively, at 90 days of curing. Durability performance was examined by exposing the GPC to harmful chemicals like 6% HCl, 6% H2SO4, 6% NaCl, and 6% Na2SO4. The water absorption is reduced with an increase in the dosage of NA in concrete. This is due to the non-porous nature of the dense and compact NA-incorporated GPC. Microstructure analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of NA at nano- and microlevels. The formation of the extra N–A–S–H gel after incorporation of NA resulted in an enhancement in the strength of GPC. The key novelty of this study lies in providing comprehensive insights into the role of NA in refining the pore structure, enhancing geopolymerization, and improving the chemical resistance of GGBS-based GPC. The findings highlight the potential of NA in producing high-performance, sustainable concrete for aggressive environments.

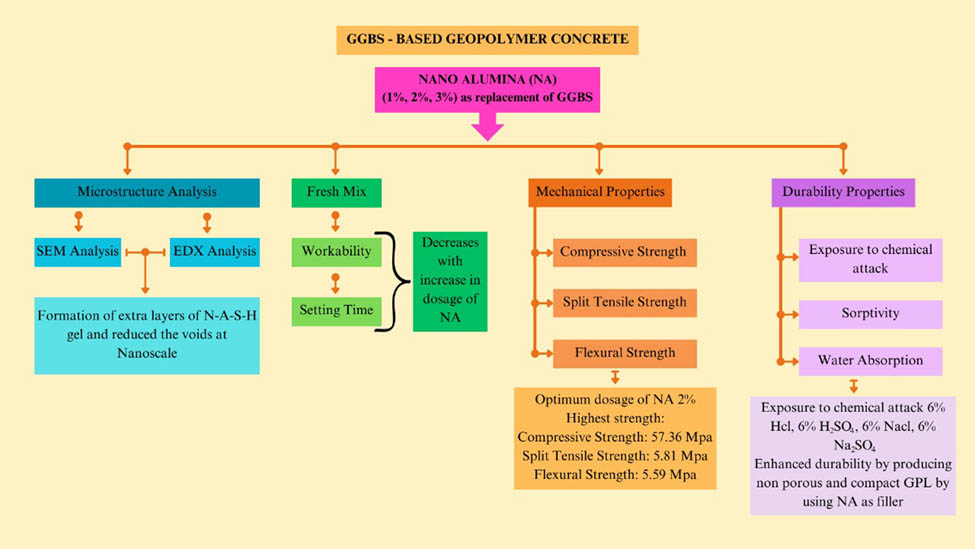

Graphical abstract

1 Introduction

Currently, cement is the most used binding material in construction; thus, it is used at a very large scale [1]. Due to excessive demand, cement manufacturing produces many harmful gases; about 1 ton of carbon dioxide per ton of cement produced significantly contributes to greenhouse gases and climate change [2]. To reduce shrinkage cracks from excessive cement use, an alternative binder is needed due to high concrete demand [3,4,5]. Geopolymer concrete (GPC) is a promising alternative binder, offering a significant replacement for cement in construction [6,7,8,9]. Materials rich in alumina and silica can serve as an effective source for alternative binders [10]. Ground granulated blast-furnace slag (GGBS) is favored in GPC for its high silica and alumina content [11,12]. This also significantly helps to reduce the disposal of industrial by-products [13,14]. Geopolymer binder is a viable alternative to cement due to its low embodied energy and reduced carbon emissions [15]. This makes it a versatile alternative for construction and repair materials, often enhanced with GGBS, a byproduct of ferrosilicon alloy production [16]. Recent studies show that geopolymer technology can reduce CO₂ emissions from the cement industry by 80%, offering a greener binder solution [17]. Cement use threatens the ecosystem; therefore, researchers are using alternatives like nanomaterials and microorganisms to reduce cement usage and CO2 production [18,19]. Heat activation is essential to accelerate polymerization and enhance the properties of GPC [20]. Nanomaterial enhances the mechanical and durability performance of GPC by accelerating the geopolymerization reaction and acting as a nanofiller and producing a dense and compact matrix [21]. There are several kinds of nanomaterials used nowadays in the GPC, such as nano-silica, nano-alumina (NA), nano-titania, graphene oxide, and carbon nanotubes [22,23,24,25,26]. The selection of NA over the other nanomaterials is due to its significantly enhanced performance in improving the mechanical and durability properties of GPC by improving the microstructure refinement, densification, and pozzolanic activity. Unlike nano-silica, which primarily accelerates geopolymerization but may lead to excessive water demand and workability issues, NA contributes to structural reinforcement while maintaining balanced rheology [27,28]. Furthermore, nano-titania has been extensively studied for photocatalytic applications, but does not provide substantial mechanical improvements compared to NA [24]. Similarly, carbonaceous nanofillers, such as carbon nanotubes or graphene oxide, require specialized dispersion techniques and may not be as effective in geopolymer matrices due to their hydrophobic nature [25,26]. Additionally, NA promotes better resistance to aggressive environments by reducing permeability and inhibiting crack propagation, making it a suitable choice for GPC applications [29]. The NA particles are present in spherical form in crystalline phase and possess pozzolanic reactivity [30]. NA has a diameter of less than 100 nm, and the surface area varies from 10 to 100 m2·g−1 [31]. The reason behind the loss of workability is the high specific surface area of nanomaterials. NA accelerates the larger hydration process, resulting in reduced workability [32]. Nanomaterials, such as NA, are used to produce concrete with higher and better mechanical properties due to the presence of higher stability, hardness, insulation, and transparency [33]. NA does not possess any effect on the geopolymerization process, and it may be added as a nanofiller [6]. NA in a small ratio may increase the tensile and compressive strength (CS) effectively. The bonding of the aggregate and binder phase is also strengthened by the use of nanoparticles [21]. Ions used in the composites are strongly dependent on the movement of water molecules. Nanoparticles are employed to slow down the deflection effects of ions such as chloride anions. By adding the organic polymer in GPC, its mechanical properties improve by changing the microstructure and pore size distribution of the GPC [34]. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy revealed that the addition of 5% NA increases the polymerization in different or many mixes [35]. An extensive study has been conducted on the reactions in which nanomaterials change the characteristics of geopolymer materials by simply adding or replacing it with some component [36]. NA does not affect the setting time of polymerization, but it influences the setting time of GPC. Hence, the percentage of nanomaterials is directly proportional to the setting time of GPC [37]. While previous studies have explored the role of nanomaterials in enhancing GPC properties, the specific impact of NA on the mechanical strength, durability, and microstructural characteristics of GGBS-based GPC remains insufficiently explored. This study aims to bridge this gap by investigating the potential of NA as a performance-enhancing additive in GPC. By examining the interaction of NA with the geopolymer matrix and its influence on mechanical properties, durability, and microstructure, this study provides valuable insights for optimizing sustainable concrete mixtures. The findings will contribute to the advancement of geopolymer technology, supporting the development of more durable and environmentally friendly construction materials suitable for aggressive environmental conditions.

Also, the present study uniquely focuses on the influence of NA on the fresh properties of GGBS-based GPC, specifically setting time and workability. This study provides novel insights into how varying dosages of NA alter the geopolymerization process, affecting initial and final setting times and the workability characteristics of the fresh mix. This study includes the determination of mechanical properties of concrete by performing CS, split tensile strength (STS), and flexural strength (FS) tests, and the influence of NA on GPC strength was studied. Apart from mechanical properties, it also includes the durability analysis of GPC after exposure to 6% HCl, 6% H2SO4, 6% NaCl, and 6% Na2SO4 for 90 days and measures the decrement in the CS of GPC in comparison with GPC cured in tap water. Sorptivity and water absorption were the other tests conducted for the durability analysis of NA-incorporated GPC. In the end, this study includes the microstructural analysis of GPC with or without NA and a study of the chemistry behind the performance of GPC by performing scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The Steel industry generates a byproduct with non-metallic characteristics, mainly comprising calcium, silica, and alkali, in molten form from blast furnace slag. GGBS is sometimes a precursor in producing GPC, providing substantial strength and performance outcomes. GGBS was chosen as the primary precursor in this study due to its high calcium and alumina-silicate content, which enhances geopolymerization and contributes to superior mechanical properties and long-term durability. GGBS-based GPC exhibits higher early-age strength due to the presence of reactive calcium, which accelerates the formation of calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) and sodium aluminosilicate (N–A–S–H) gels [38]. Additionally, the use of GGBS as a cement alternative significantly reduces carbon emissions, aligning with sustainability goals in construction materials [39]. GGBS can perform well as a binder in comparison with ordinary Portland cement due to the presence of monosilicate in it. GGBS also improves the durability performance of GPC by reducing the voids present in GPC and reducing the water requirement for the curing process [40]. GGBS was obtained from the local vendor and confirmed the guidelines given in IS 12089 (1987) [41]. It is more practical to use sodium hydroxide (SH) in flake form, with a purity between 94 and 96%. In this study, SH flakes were used due to their better zeolitic properties. The basic solution for polymerization is prepared by dissolving SH in distilled water in a 1 L flask, achieving a 16-molar solution. A sodium silicate (SS) solution known as glassy water is available in various concentrations. In this study, the ratio of SS/SH is kept at 2.5. This study uses Badarpur sand as a fine aggregate (FA). The specific gravity of FA was observed as 2.3, and the fineness modulus of sand was 2.2. Crushed granite stones were used as coarse aggregate (CA). The laboratory calculated its density as 2.5 tons·m−3. The maximum size of CA was 20 mm, having a fineness modulus of 7.1 and a specific gravity of 2.65. Polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer (SP) significantly improves workability in concrete mixes. This is especially important in GPC, where the viscous alkaline solutions can affect both fresh and hardened properties. By incorporating effective SPs, the overall quality and durability of concrete structures are greatly enhanced. It is light yellow and has an optimum dosage of 1.2%. The chemical composition of GGBS and NA is presented in Table 1. The characteristics of the material used are shown in Table 2. NA was selected for this study due to its high surface area, pozzolanic reactivity, and ability to enhance the microstructure of GPC. NA acts as a nanofiller, refining the pore structure and improving the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the geopolymer matrix and aggregates [31]. Additionally, NA contributes to the densification of the geopolymer matrix by forming additional N–A–S–H gels, which improve both mechanical strength and durability properties [30].

Percentage of oxides present in the precursor and additives

| Sample (%) | SiO2 | Fe2O3 | CaO | Al2O3 | MgO | K2O | Na2O | SO3 | P2O5 | TiO2 | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGBS | 30.26 | 0.74 | 43.8 | 15.4 | 4.9 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 4.35 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| NA | — | 0.031 | 0.013 | 99.3 | 0.008 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Characteristics of the material used

| Property | GGBS | NA | FA | CA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water absorption (%) | — | — | 0.5 | 1.1 |

| Fineness modulus (m2·kg−1) | 380 | — | 2.2 | 7.1 |

| Specific gravity | 3.1 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 2.65 |

| Average diameter | 6.30 | — | — | — |

| Source | Steel industry | — | River Sand | Granite Stone |

2.2 Methodology

In this study, GPC was designed and mixed in three different mix proportions, i.e., control GPC (0NA), in which 100% GGBS is used as a precursor, incorporating various dosages of NA (designated as 1NA, 2NA, and 3NA) as partial replacement of GGBS by 1, 2, and 3% by weight of GGBS. NA was incorporated into the concrete mix in its dry powder form. It was mechanically mixed along with other dry ingredients to ensure uniform dispersion. The mixing process involved the sequential addition of NA to the dry components, followed by thorough mechanical blending to achieve homogeneity. No ultrasonic treatment or dispersing agents were used during the preparation. To ensure proper distribution of NA within the mix, a high-shear mixer was employed to blend the dry constituents before the addition of liquid components. The approach facilitated even distribution of NA within the matrix, preventing agglomeration and enhancing its effectiveness in modifying GPC properties. The study focused on designing an M30 grade of GPC and converting it into high-strength concrete. The selection of 1, 2, and 3% NA replacement in GGBS-based GPC was based on a combination of prior research findings, particle packing considerations, and the pozzolanic activity of NA [42]. Previous studies have shown that nanomaterials enhance the mechanical and durability properties of concrete, but their effectiveness is highly dosage-dependent [30]. A low dosage (<1%) may not sufficiently improve the geopolymerization process, whereas an excessive dosage (>3%) can lead to agglomeration, increased viscosity, and reduced workability, which negatively impacts concrete performance [43]. To establish an optimum dosage range, three levels of NA incorporation (1NA, 2NA, and 3NA) were selected. To ensure consistency across all batches, the NaOH solution was prepared at least 24 h before mixing to allow complete dissolution and stabilization. The Na2SiO3 solution was used as received and stored in a sealed container to prevent any changes in composition due to aging or atmospheric exposure. The NaOH and Na2SiO3 solutions were mixed at room temperature and allowed to rest for 1 h before use to ensure uniformity in the activator composition across different batches.

The curing conditions significantly influence the geopolymerization process and the development of mechanical properties in GPC. In this study, a two-stage curing process was adopted: an initial oven curing at 60°C for 24 h, followed by room-temperature curing until the testing age. The selection of 60°C as the curing temperature is based on prior research, indicating that moderate heat curing accelerates the dissolution of aluminosilicate precursors in GGBS, leading to the formation of additional calcium–aluminosilicate–hydrate (C–A–S–H) and sodium–aluminosilicate–hydrate (N–A–S–H) gels, which enhance early-age strength development [44]. Oven curing provides the necessary thermal activation to accelerate geopolymerization, ensuring rapid setting and strength gain. However, prolonged high-temperature curing can lead to microcracking due to excessive shrinkage. To counterbalance this, subsequent room-temperature curing was implemented to allow further geopolymerization to occur gradually, improving long-term strength and durability [45]. Studies have shown that a combination of thermal curing followed by ambient curing results in better mechanical performance and reduced porosity compared to only room-temperature curing [46]. This dual-curing approach ensures that the geopolymer matrix achieves higher densification and improved microstructural integrity, leading to enhanced mechanical and durability properties. The mixed proportion of different grades of GPC is shown in Table 3. In this study, a water/solid ratio of 0.24 was selected based on previous research and recommendations from GPC mix design studies [44]. Although no direct IS code exists for GPC mix proportioning, the selection aligns with methodologies suggested in research-based mix design approaches for GPC adopted by other researchers [47,48].

Mixed proportion of the prepared GPC

| Mix designation | GGBS | NA | FA | CA | SH | SS | SP | Mix ratio | Water/solid ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0NA | 377.14 | 0 | 561.6 | 1310.4 | 43.10 | 107.76 | 6 | 1:1.48:3.47 | 0.24 |

| 1NA | 373.37 | 3.77 | 561.6 | 1310.4 | 43.10 | 107.76 | 6 | ||

| 2NA | 369.6 | 7.54 | 561.6 | 1310.4 | 43.10 | 107.76 | 6 | ||

| 3NA | 365.83 | 11.31 | 561.6 | 1310.4 | 43.10 | 107.76 | 6 |

2.2.1 Slump test

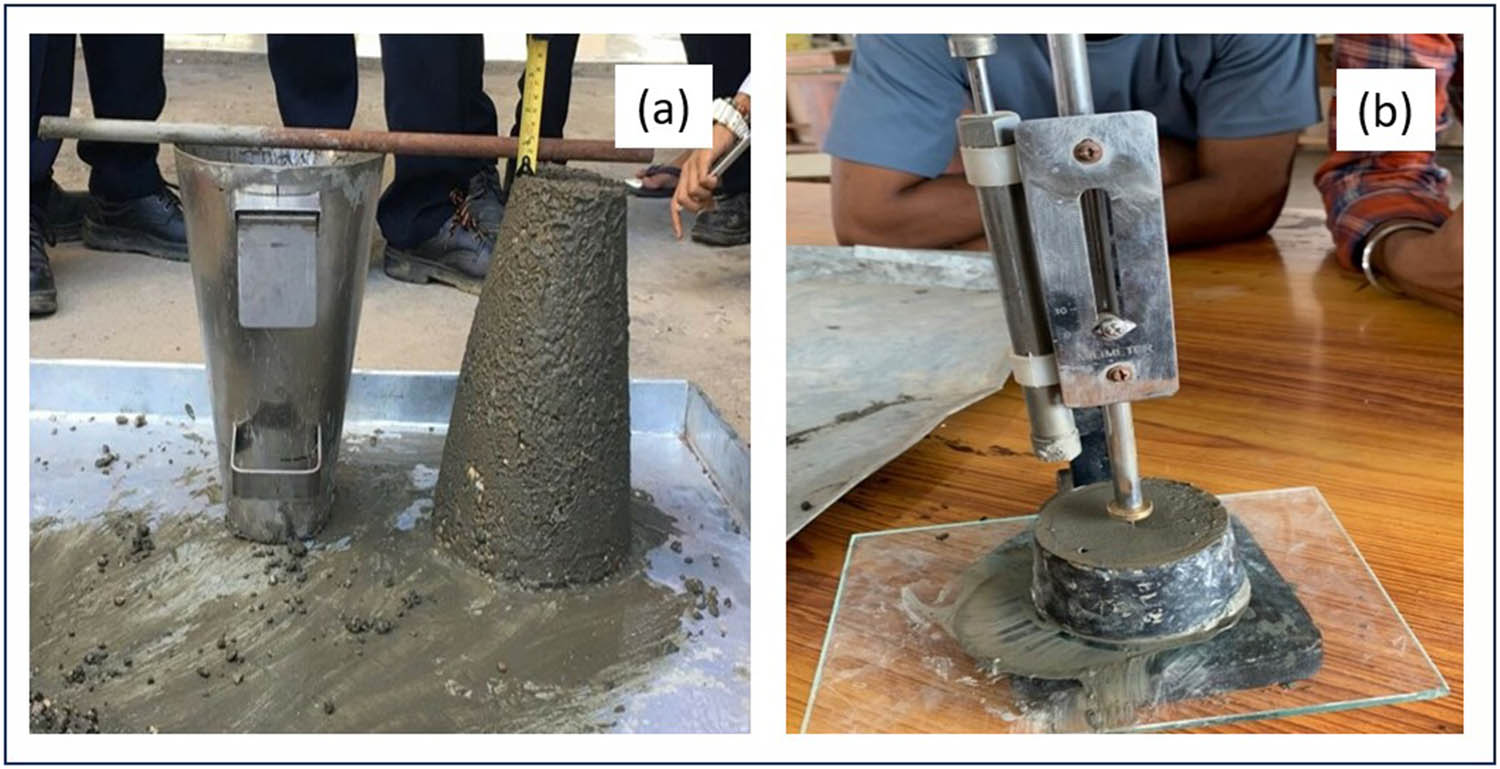

The first test on the freshly prepared GPC was a slump test to measure the workability of the freshly prepared GPC mix. The slump test, as per IS 1199-1959 (reaffirmed in 2013), indicates a compacted concrete cone’s behavior under the action of gravitational forces [49]. In the present study, the control GPC was designed to have a slump lying between 100 and 150 mm for the desired M30-grade concrete. The slump test performed is shown in Figure 1(a).

Physical appearance of the (a) slump test and (b) setting time test.

2.2.2 Setting time test

The two main stages in the setting process are the initial setting and the final setting. The initial setting time of mixing is the time when concrete starts to harden; in this stage, there is generally a significant loss of workability. This stage depends on factors such as the water-to-binder ratio and ambient temperature, among many others. It is the final setting where concrete gains enough strength to carry loads and cannot be shaped or finished anymore. Monitoring these setting periods is important since early hardening leads to cracking or poor bonding. With good control of the setting time through mix design and environmental management, construction professionals can optimize the performance and durability of concrete structures. The setting time of GPC with or without NA is determined by conforming to IS 8142(1976) guidelines [50]. The setting time tests were conducted in a laboratory environment at room temperature (approximately 27°C) and under normal atmospheric humidity conditions. No external temperature or humidity control measures were applied. The physical appearance of the setting time performed is shown in Figure 1(b).

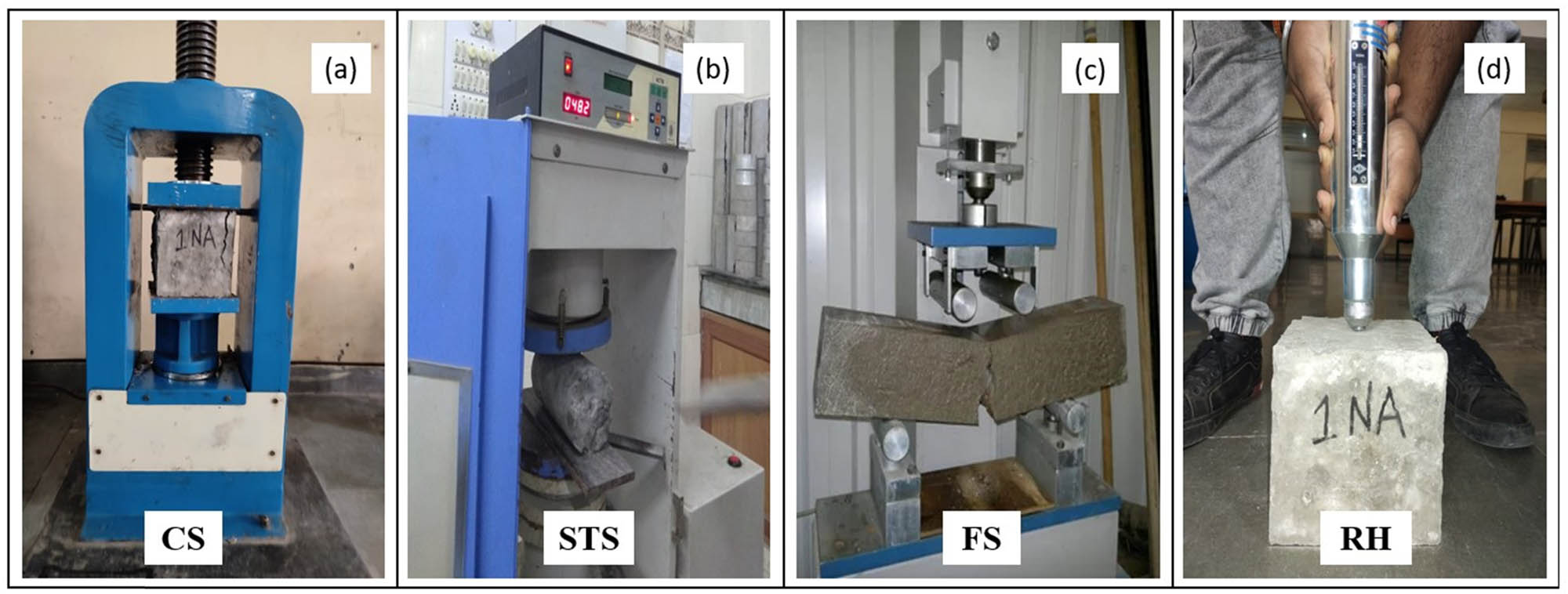

2.2.3 Compressive strength (CS) test

To evaluate the material’s performance and mix, GPC specimens of size 150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm were cast in the laboratory. The CS test for GPC was done as per IS 516-1959 (Reaffirmed in 2004) [51]. Overall, 48 GPC cube samples were cast, and specific designations were allotted to them. After casting the specimens, the molds were removed after 24 h. The specimens were kept in an oven for 1 day after the removal of molds at 60°C. After that, specimens were cured for 7, 28, 56, and 90 days in the water curing tank. Before testing these GPC specimens, the cube’s surfaces were first dried with a piece of cloth and then placed in the compressive testing machine (CTM), as shown in Figure 2(a).

Setup for (a) CS, (b) STS, (c) four-point FS and (d) RH test in the laboratory.

2.2.4 Split tensile strength (STS) test

The STS test of the concrete was done to assess the tensile strength of GPC. The STS test was performed as per IS 5816-1999 (reaffirmed in 2004) [52]. A total of 36 cylindrical specimens of 100 mm diameter and 200 mm long were cast and demolded after 24 h and kept in an oven for 1 day at 60°C. After 28, 56, and 90 days, the cast cylinders were taken out from the curing tank, and the surfaces of the cylinders were dried with a piece of cloth, and then they were kept under CTM to ascertain the tensile strength of GPC, as shown in Figure 2(b).

2.2.5 Flexural strength (FS) test

FS test was performed on beams of size 100 mm breadth, 100 mm height, and 500 mm length. The test was conducted as per IS 516-1959 (reaffirmed in 2004) [51]. A total of 24 beams were cast and demolded after 24 h and kept in an oven for 1 day at 60°C. After 28 and 90 days, the cast beams were taken out of the curing tank, and the surfaces of the beams were dried with a piece of cloth for testing. Four-point loading was applied on the rectangular prism beam’s top surface to test the rectangular prism beam, as shown in Figure 2(c).

2.2.6 Durability: Exposure to chemical attack

This study investigates the durability of GPC, particularly its ability to resist chemical attack under various aggressive environmental conditions. A total of 48 M30-grade GPC cubes, with and without NA, were cast and subjected to chemical exposure to examine their performance. After casting, the cubes were removed from the molds after 24 h and kept in an oven at 60°C for 1 day before being cured in normal water for 28 days. The cubes were then exposed to different chemical solutions: 6% sodium chloride (NaCl), 6% sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), 6% hydrochloric acid (HCl), and 6% sulfuric acid (H2SO4) for 90 days. The concentrations of chemicals were selected based on previous studies [22,53–55]. Following the exposure period, the CS of the cubes was tested using a CTM to assess the durability and resistance of GPC to chloride and sulfate attacks.

2.2.7 Durability: Sorptivity test

Sorptivity is a measure of the capability of GPC to percolate water through pores and transmit under capillary action. Sorptivity is an important feature in studying the durability characteristics of GPC as it connects to the rate of liquid penetration into the concrete. In this study, sorptivity is determined before and after the chemical exposure on the penetrating surface of concrete as per ASTM C642 [56]. To perform the sorptivity test, GPC cubes were prepared and dried in an oven for 1 day at 60°C and then left at room temperature for 1 day for cooling. After that, all the peripheral surfaces of the cube, including the top, are covered with the tape, except the base, to protect from water entry from the sides and the top of the cube. The specimen was left in a container with water up to 3–5 mm from the base of the cubes. After 7 days, the specimen’s weight was measured to calculate the quantity of water absorbed. The bottom surface of the cube, exposed to chemicals, was wiped with a cloth before measuring the weight of the specimen. Sorptivity was then calculated using Eqs. (1) and (2) [22]:

where t is the time of exposure of the specimen surface to the liquid, δm is the variation in the mass of the specimen in g due to penetration of liquid, a is the area of the cube in mm2, and d is the water density in g·mm−3.

2.2.8 Durability: Water absorption test

Water absorption is another feature that is used to analyze the durability characteristics of GPC. A water absorption test was conducted on a 150 mm hard cube in this study as per ASTM C642 [56]. Initially, GPC specimens were oven-dried at 60°C for 1 day, left at room temperature for 1 day, and then measured the initial weight W 1. After that, GPC cubes were immersed in water and weighed after cleaning with a cloth at 1, 12, 24, and 72 h intervals, giving the final weight W 2. Water absorption was determined using Eq. (3) [22]:

2.2.9 Non-destructive test: Rebound hammer (RH) test

The RH test is one of the most popular forms of non-destructive tests. It is specifically used in testing CS in concrete structures. This technique is beneficial as it tests the concrete quickly with less damage. Thus, it is very useful in repair and restoration projects where damage needs to be minimal. The RH test works on the principle that the hardness of the concrete directly relates to its CS. The RH test was performed for specimens with or without NA. Cubical specimens of size 150 mm were prepared and cured for 28 and 90 days at ambient temperature after curing in an oven for 1 day at 60°C. The RH test was performed following the guidelines of IS 13311(2)-1992 [57], as shown in Figure 2(d).

2.3 Microstructural analysis

SEM was used for the microstructural examination of GPC. This technique has a resolution that may give details on the composition and morphology of the material, besides offering surface characteristics needed to understand the behavior of the ingredients used in GPC. The specimens of the GPC were polished before testing. The sample was then placed in the SEM chamber, where electrons bombarded it through a focused beam that produced secondary electrons that were picked up to produce image details on the surface at various magnifications.

3 Results and discussion

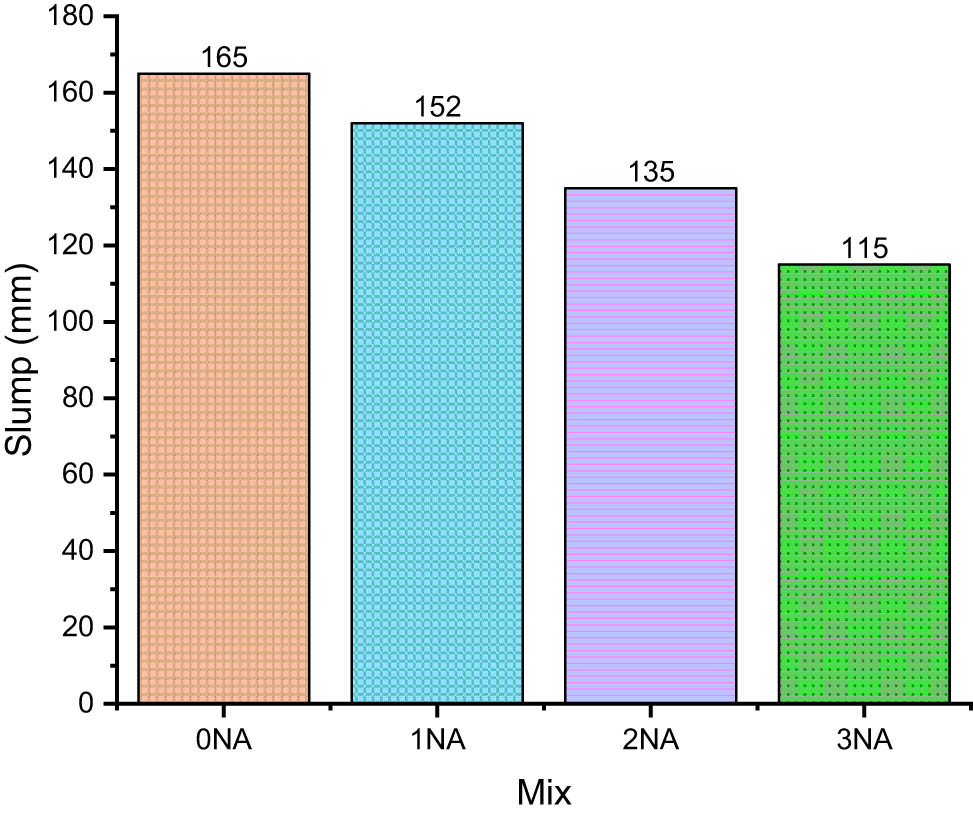

3.1 Slump test

Figure 3 presents the slump values measuring the workability of the GPC mix. It can be clearly seen that compared with a normal GPC mix, the reduction in the slump values is in the NA-based GPC. The reduction in the slump value was caused by the larger surface area of nanoparticles, which required excess water for the mix. This excess water demand was controlled by the additional dosage of SP in the GPC mix. The mix containing NA reported a decrease in the slump as the NA doses increased. The incorporation of NA significantly affects the workability of GPC due to its high surface area and strong van der Waals forces, which increase the water demand and lead to a rapid loss of slump. SP plays a crucial role in mitigating this issue by reducing interparticle friction and dispersing the nanoparticles more effectively within the mix. In this study, a polycarboxylate-based SP was used, which improves the flowability of the mix by electrostatic repulsion and steric hindrance mechanisms, ensuring better dispersion of NA and preventing agglomeration [58]. It was observed that as the NA dosage increased, the slump values decreased, primarily due to the increased surface area and higher water absorption capacity of NA. However, the controlled addition of SP counterbalanced this effect, maintaining acceptable workability levels for practical applications. This behavior aligns with previous studies, where the incorporation of nanomaterials in cementitious systems necessitated the use of SP to sustain adequate rheological properties [59–61]. These findings highlight the necessity of optimizing SP dosage to achieve a balance between strength enhancement and workability in NA-incorporated GPC.

Slump results of different GPC mixes.

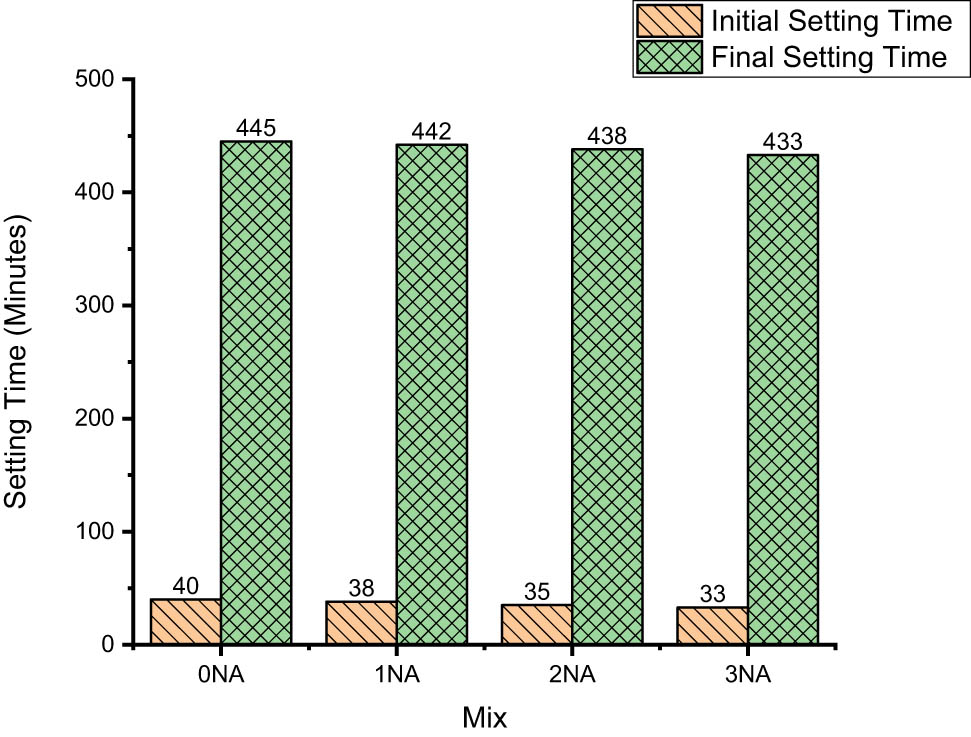

3.2 Setting time

The setting time results of different GPC mixes incorporated with different dosages of NA are shown in Figure 4. It was noticed that the setting time of GPC decreased with an increase in the dosage of NA. The maximum decrease in the initial setting time up to 7.89% was observed after the incorporation of 2% NA in concrete. The highest decrement in final setting time up to 1.14% was observed after the incorporation of 3% NA in concrete. This result aligns with the observations of Phoo-ngernkham et al., and it was noted that there was a slight decrement in the setting time after incorporation of NA in GPC, whereas the reduction in the setting time was greater during the incorporation of nano-silica in a similar mix [30]. However, Chindaprasirt et al. reported that a greater reduction in the setting time of GPC after incorporation of NA by more than 7% in fly ash-based GPC [62]. Therefore, we can conclude that an increase in the dosage of nanoparticles tends to accelerate the setting process in GPC. The decrement in the setting time was also noticed by Zhang et al. in the cement concrete after the incorporation of NA up to 1%, but the setting time was increased after further increments in the dosage of NA by more than 1% [63]. This is due to the nucleation and growth of the C–A–S–H gel, mainly occurring during the acceleration periods, as nanomaterials used as nucleating agents to promote geopolymerization and hydration, shorten the induction and acceleration time, and accelerate the setting and hardening owing to nanoparticles [64]. The reduction in the setting time of NA-incorporated GPC can be due to the faster interaction of the Al–O and Al free bonds of NA with dissolved species [65]. This may be due to the adsorption of water with a wide specific area of the NA. Thus, NAs perform as additive agents for the geopolymerization reaction [66].

Setting time of different GPC mixes.

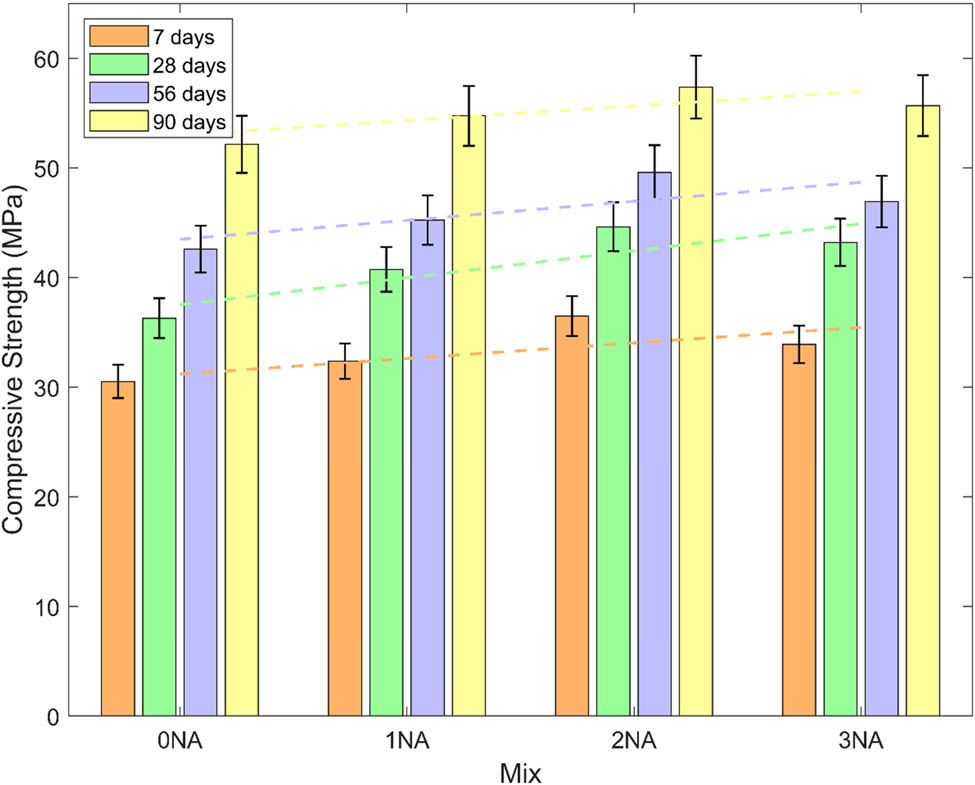

3.3 Compressive strength

As shown in Figure 5, among the four GPC mixes, the highest increment in the CS at 28 days compared to the normal GPC mix was noted as 22.97% NA-based GPC at 2% dosage and 60°C curing period for 1 day in an oven and then at room temperature in normal tap water until the day of testing. The CS of GPC after 28 days curing without NA was 36.28 MPa, but after incorporation of 1, 2, and 3% NA dosage as replacement of GGBS, the CS values were 40.73, 44.61, and 43.19 MPa, respectively. The reason for the gain in the strength at 7, 28, 56 and 90 days may be attributed to the incorporation of nanoparticles in the mix, which made the matrix stronger. A very strong bond seems to exist between the matrix ingredients, which further makes it impermeable. The maximum strength was at 90 days for GPC cured at 60°C for 1 day, and that for 90 days kept at room temperature. The data are as follows: 52.14, 54.73, 57.36 and 55.68 MPa for 0% NA, 1% NA, 2% NA, and 3% NA, respectively. Hence, it is concluded that by the inclusion of nanoparticles, the normal M30 grade GPC attains much higher strength, thus transforming to higher strength. From Figure 5, it is also noticed that the CS of GPC increases with increasing NA dosage up to 2%; with further increments in the NA dosage, the CS starts decreasing. While the CS of GPC increased with NA incorporation up to 2%, a slight reduction in strength was observed at 3% NA. This reduction can be attributed to the agglomeration of nanoparticles, which limits their effective dispersion within the geopolymer matrix. Excessive NA can lead to increased viscosity of the mix, reducing workability and creating microstructural inconsistencies [67]. Additionally, the high surface area of NA increases water demand, potentially leading to incomplete geopolymerization reactions and reducing the formation of C–A–S–H and N–A–S–H gels [30]. Similar trends have been reported in previous studies, where higher dosages of nanomaterials caused particle agglomeration, reducing their reinforcing effectiveness, leading to strength loss [42]. Similar results were observed by Zidi et al. during the analysis of the influence of NA on the CS of metakaolin-based GPC [65]. This improvement in the performance of NA-incorporated GPC is due to high homogeneity in the matrix structure, better rearrangement of the chain geopolymers, and high efficiency of the geopolymeric reaction, which is related to the growth and accumulation of the geopolymer gel. Reddy and Ramujee noticed that in comparison with ordinary Portland concrete (OPC), GPC performed well after the incorporation of NA in concrete, and the optimum dosage of NA for both OPC and GPC was 2% [42]. The Pozzolanic reaction of NA and its role in densifying the geopolymer matrix contributed to enhanced strength development. Similar enhancement in the CS of GPC was noticed in comparison with OPC, keeping the mix proportion same by Farhan et al. due to dense microstructure formed during the geopolymerization and formation of N–A–S–H gel along with C–S–H gel [68].

The CS of different GPC mixes.

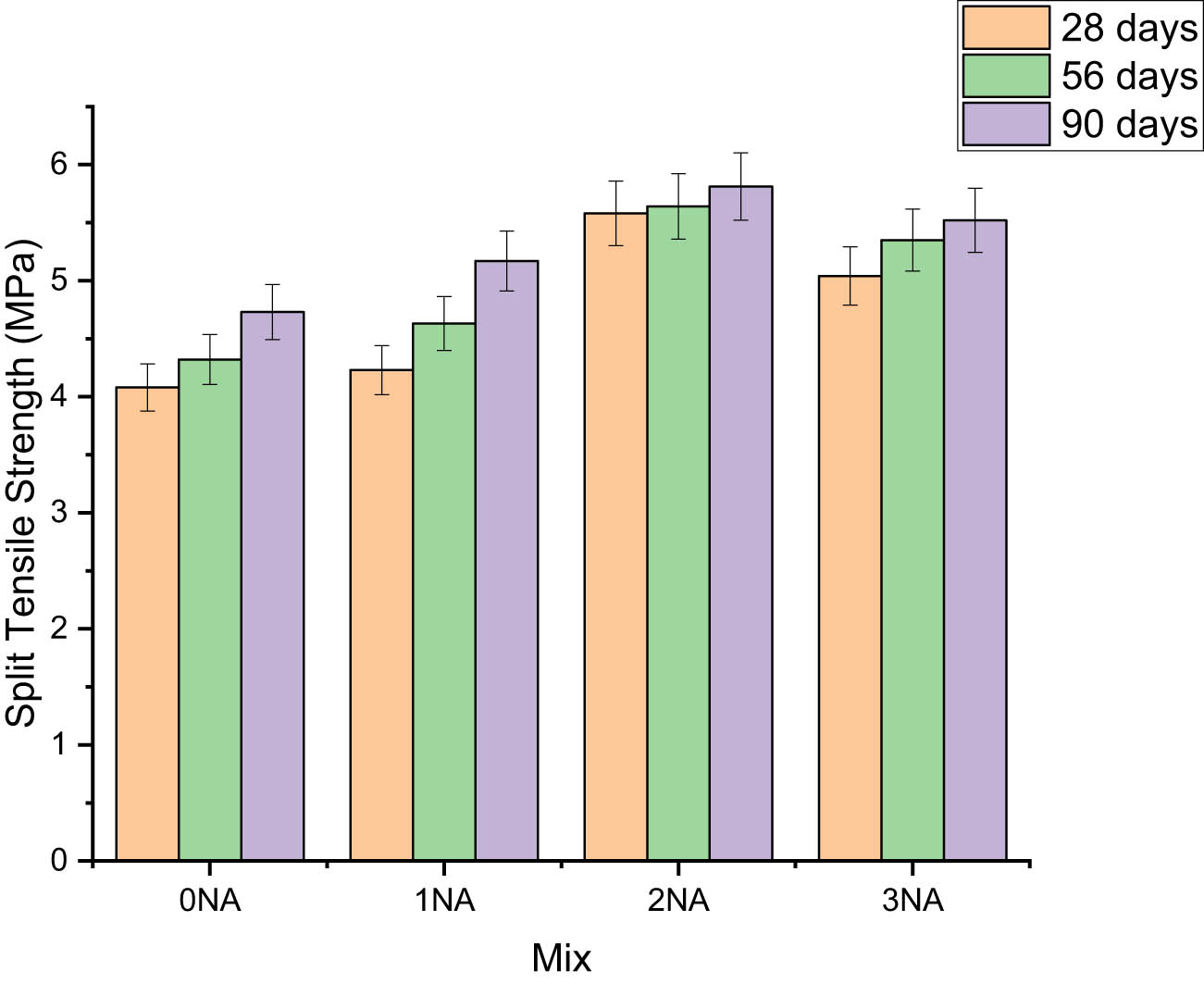

3.4 Split tensile strength

The STS results of different GPC mixes with or without NA are shown in Figure 6. It was noticed that STS increases as the dosage of the nanoparticle is increased. The maximum increase was observed in 2% NA-based GPC. An increase of about 36.77% at 28 days in comparison with the normal mix was observed in NA-based GPC at 60°C curing with 2% dosage, as compared to 3.68 and 23.53% in 1% NA and 3% NA-based GPC, respectively. The STS of GPC after 28 days curing without NA was 4.08 MPa, but after incorporation of 1, 2, and 3% NA dosage as replacement of GGBS, the STS were 4.23, 5.58, and 5.04 MPa, respectively. The maximum STS was observed to be 5.81 MPa for 90 days of curing after the incorporation of 2% NA in GPC. The reason for this increase in the STS was due to the presence of nanoparticles, which improve the fracture properties of the geopolymer matrix by controlling the matrix cracks at the nanoscale. The increase in STS with higher NA dosage can be attributed to the ability of NA to enhance the fracture properties of GPC. NA acts as a nanofiller, reducing porosity and refining the ITZ between aggregates and the geopolymer matrix. This leads to improved stress transfer across microcracks, delaying crack propagation and enhancing fracture resistance [69]. Additionally, NA incorporation increases the formation of N–A–S–H gels, improving matrix densification and bonding at the nanolevel, thereby improving the tensile strength of GPC [21]. Previous studies have shown that nanomaterials, particularly NA, improve fracture energy by enhancing the crack-bridging mechanism and impeding crack growth [65]. GGBS-modified concrete has more ductile failure mechanisms. The improved bonding and refined microstructure reduced the initiation and propagation of microcracks, which are the primary cause of failure under tensile loads [70]. This contributes to higher STS.

STS values of different GPC mixes.

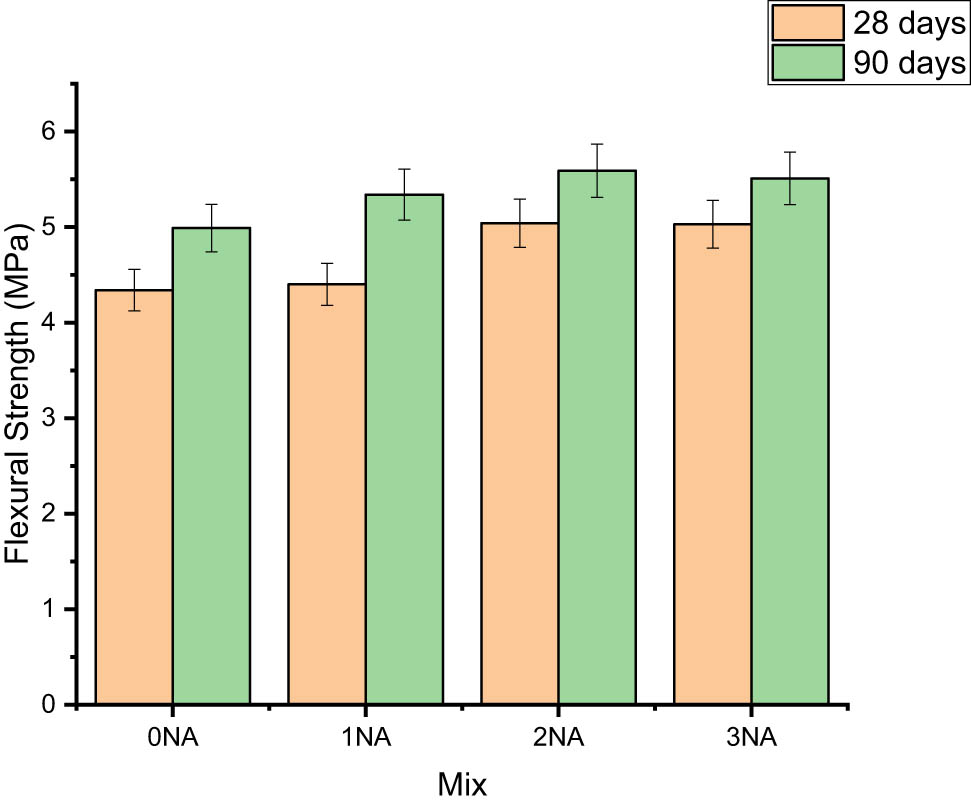

3.5 Flexural strength

The FS results of different GPC mixes are shown in Figure 7. It was noticed that FS increases with an increment in the dosage of nanoparticles. There is a negligible difference in the FS of the GPC mix incorporated with 2 and 3% NA. The maximum percentage of increment was again observed in 2% NA-based GPC. A remarkable increase of about 16.13% at 28 days of curing was observed in NA-based GPC beams at 2% dosage as compared to 1.39 and 15.89% in 1 and 3% NA dosages, respectively. The FS of GPC after 28 days curing without NA was 4.34 MPa. However, after incorporation of 1, 2, and 3% NA dosage as a replacement for GGBS, the FS values were 4.4, 5.04, and 5.03 MPa, respectively. The maximum FS was observed to be 5.59 MPa for 90 days of curing after the incorporation of 2% NS in GPC. Also, from Table 4, it can be observed that the FS calculated experimentally was more than that calculated as per IS 456-2000. The increase in FS is due to the presence of nanoparticles, which improve the GPC’s compaction and densification properties and further improve the geopolymer matrix’s fracture properties by controlling the matrix cracking at the scale level. While the increase in FS with 2% NA is notable, the negligible difference between 2 and 3% NA can be attributed to the agglomeration of excess nanoparticles, leading to non-uniform dispersion within the matrix. At 2% NA, the NA effectively enhances the ITZ by acting as a nanofiller, improving matrix densification and stress distribution [71]. However, beyond this dosage, agglomeration reduces the effectiveness of NA as a reinforcing agent, preventing further significant improvements in FS [72]. Additionally, excessive NA can increase the viscosity and reduce workability, impacting the efficiency of particle packing, leading to microstructural inconsistencies [58]. These findings align with previous studies, where nanomaterial dosage beyond an optimal level results in a plateau or slight reduction in the mechanical properties due to particle clustering and ineffective dispersion [30].

FS values of different GPC mixes.

FS test results for NA-based GPC cured at 60°C

| Beam designation | 28 days (MPa) | % increase in FS | Fcr* (28 days FS) = 0.7

|

90 days (MPa) | % increase in FS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0NA | 4.34 | — | 4.22 | 4.99 | — |

| 1NA | 4.4 | 1.39 | 4.47 | 5.34 | 7.02 |

| 2NA | 5.04 | 16.13 | 4.68 | 5.59 | 12.03 |

| 3NA | 5.03 | 15.89 | 4.61 | 5.51 | 10.42 |

*As per IS 456:2000.

3.6 Durability test: Concrete exposure to different harmful chemicals

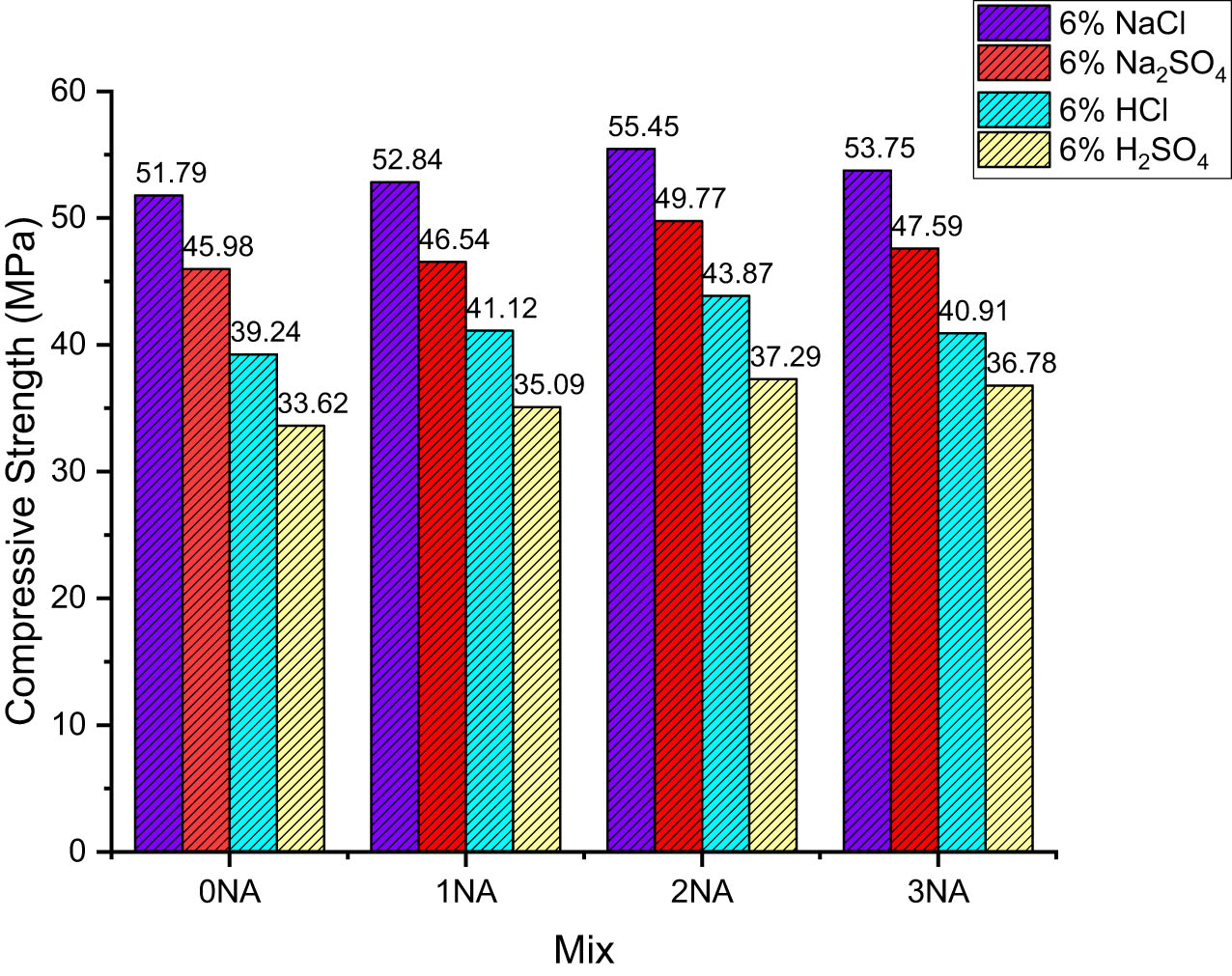

The CS results of different GPC mixes exposed to harmful chemicals for 90 days are shown in Figure 8. On exposure to 6% NaCl, it is observed that there is a remarkable increase of 6.80% at 2% NA dosage for 90 days of curing. On exposure to an additional 6% Na2SO4, there is a remarkable increase at 3% dosage of NA. It is observed that there is an increment of 3.38% at 3% NA dosage as compared to 1.20% at 1% and 0.07% at 2% NA dosages, respectively, on curing successfully for 90 days. At 6% HCl, there is an observed maximum percentage increase in CS at 2% dosage of NA, i.e., an increase of about 10.55% as compared to 4.57 and 4.08% at 1 and 3% NA dosage, respectively, on curing it for 90 days. At 6% H2SO4, it is observed that there is a maximum increase observed at 2% NA dosage of about 9.84% as compared to 4.18 and 9.39% increase for 1 and 3% dosage of NA, respectively, after curing for 28 days. The reduced effect of chloride attack on nanomaterial-based GPC and increase in CS was due to the filling of voids by the larger surface area of the nanoparticles, which makes the GPC impermeable and also makes it a denser and compact GPC. NA significantly enhances the GPC resistance to chemicals by refining the microstructures and creating a denser material more resistant to ion penetration. However, Rani and Gladston noticed that after reaching a 2% increase in the amount of NA, the observed improvements in resistance to CS degradation become less substantial, implying that beyond this threshold, additional NA yields negligible returns [73]. GGBS plays a vital role in chemical resistance as it reacts with calcium hydroxide produced during geopolymerization, forming an additional layer of the C–S–H gel. This improves the microstructure, reducing porosity and enhancing durability against chemical attacks [74]. Even the reaction product of GGBS contributes to the formation of stable hydration phases such as ettringite and monosulfate, which resist sulfate attacks. Additionally, NA facilitates the development of dense ITZ, minimizing chemical penetration [75]. Another study also indicates that GGBS-modified concrete exhibits superior resistance to sulfuric and hydrochloric acid exposure due to its low calcium content and reduced Ca(OH)2 dissolution. Also, the combination of NA and GGBS reduces pore connectivity and refines the pore structure, which significantly decreases chloride ion diffusion, mitigating reinforcement corrosion risks [76]. The improved durability characteristics suggest that NA-incorporated GPC can be a suitable material for real-world applications, particularly in infrastructure exposed to aggressive environments such as marine structures, bridges, and pavements. The reduced permeability and enhanced mechanical stability contribute to prolonged service life and reduced maintenance costs.

CS of GPC exposed to harmful chemicals for 90 days.

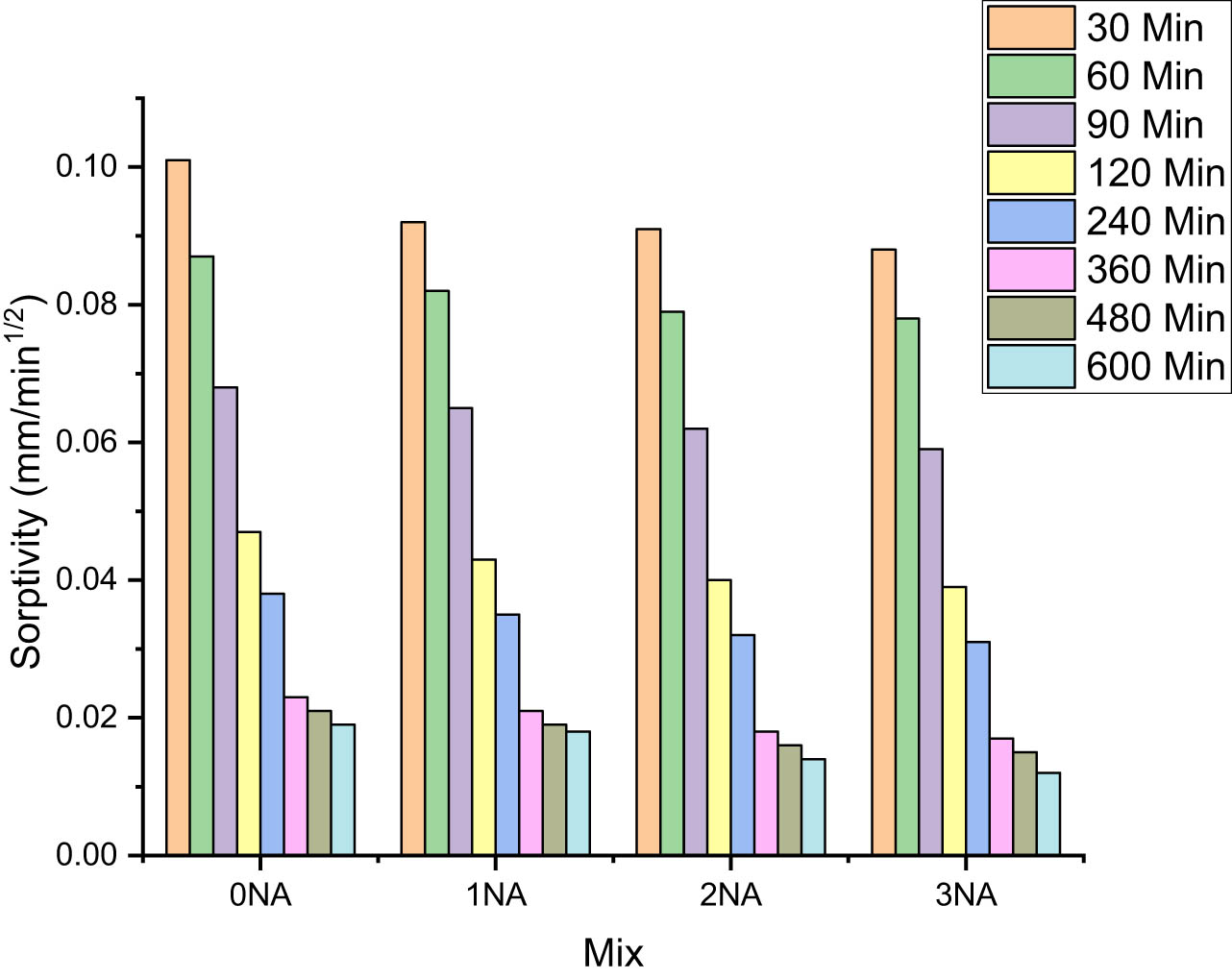

3.7 Durability test: Sorptivity

The sorptivity test results of different GPC mixes are shown in Figure 9. It is observed that the sorptivity effect on GPC decreases with an increase in the dosage of NA for all GPC mixes. The NA-based GPC with 3% imparts a maximum decrement of 12.87% at 30 min in contrast to 8.91 and 9.9% decrements with a dosage of 1 and 2% NA, respectively. The same trend is seen for all the curing periods. After 600 min, a 36.84% decrease in sorptivity of NA-based GPC with 3% NA dosage, a 26.31% decrease for NA GPC with 2% NA, and a 5.26% decrement with 1% NA GPC in comparison with the controlled GPC was observed. In the initial stages, the disparity in sorptivity among all GPC specimens cured is minimal, primarily attributable to capillary forces driving absorption. The reduction in sorptivity at later stages can be attributed to the progressive densification of the geopolymer matrix due to the NA pore-filling effect. Initially, water penetration is governed by capillary forces. However, as geopolymerization continues, the additional formation of the N–A–S–H gel due to NA incorporation refines the pore structure, reducing interconnectivity between capillary pores [31]. The presence of NA enhances secondary reaction phases, leading to the development of a denser matrix over time, further restricting water ingress at later curing stages [33]. Previous studies have shown that nanomaterials reduce sorptivity by blocking pathways for moisture transport, thereby improving long-term durability and resistance to chemical penetration [17].

Sorptivity results of different GPC mixes.

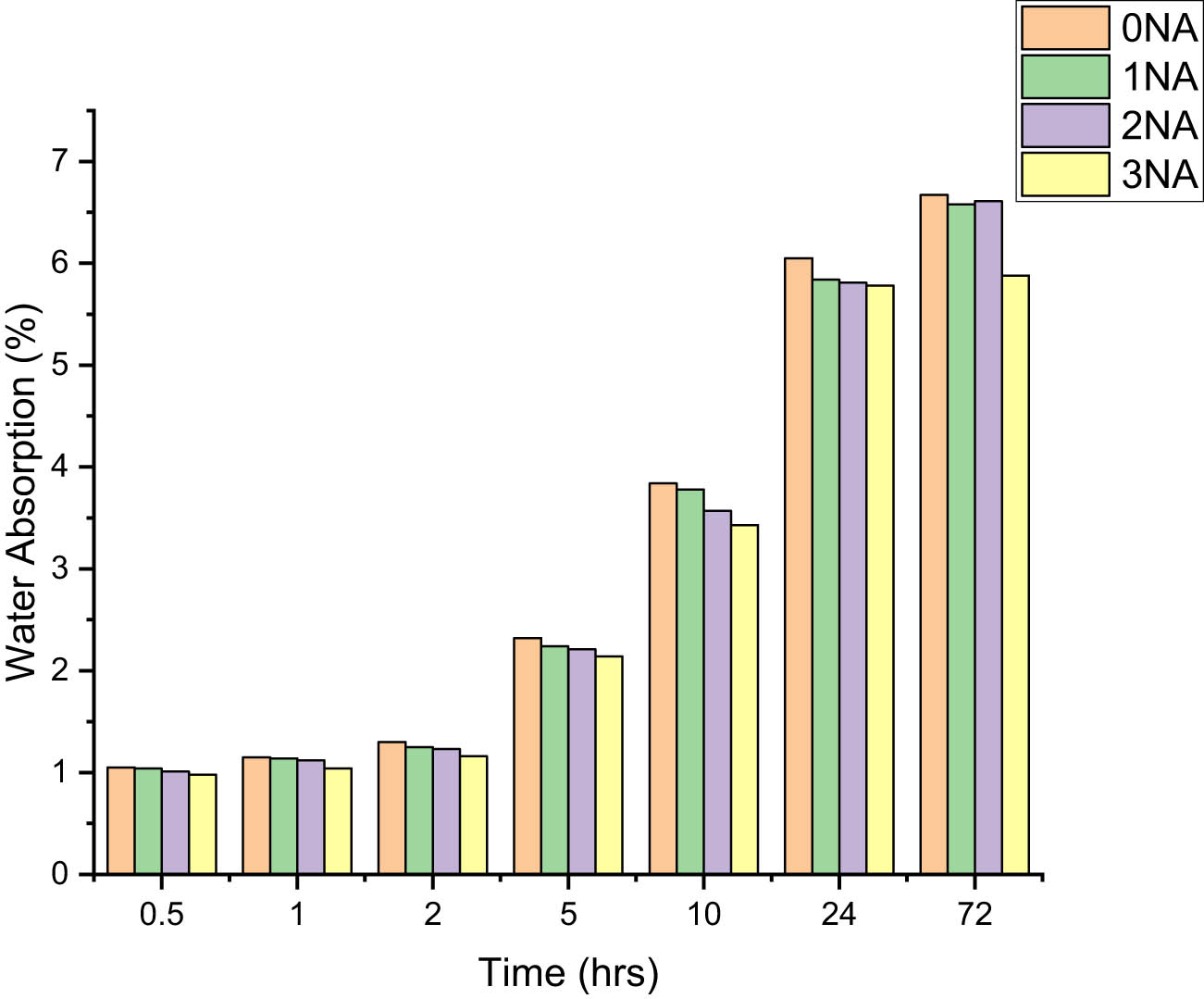

3.8 Durability test: Water absorption test

Figure 10 shows the water absorption results of GPC with or without NA. It was noticed that for all curing durations, water absorption was reduced with an increase in the dosage of NA in concrete. This is due to the non-porous nature of the dense and compact NA-incorporated GPC. The control GPC exhibited the highest water absorption, while the mix incorporating 2% NA showed the lowest absorption. However, a slight increase in water absorption was observed at 3% NA incorporation, which can be attributed to nanoparticle agglomeration, leading to localized defects. The observed reduction in water absorption with increasing NA content is primarily due to the pore-filling effect of NA. NA particles act as nanofillers, effectively blocking capillary pores and refining the microstructure, thus reducing the overall porosity of the concrete. The interaction of NA with the geopolymer matrix enhances the formation of N–A–S–H and C–A–S–H gels, leading to a more compact and impermeable structure [31]. Additionally, NA improves the ITZ between aggregates and the geopolymer binder, reducing the connectivity of pores and impeding water penetration [58]. A similar trend has been reported in previous studies, where the addition of nanomaterials, including nano-silica and NA, significantly reduced water absorption due to improved particle packing and enhanced gel phase formation [30]. The reduction in water absorption correlates with improved durability performance, as lower porosity reduces the ingress of harmful ions, minimizing the risk of chemical attack, chloride penetration, and freeze–thaw deterioration [33]. However, at 3% NA dosage, the slight increase in water absorption can be linked to nanoparticle agglomeration, which creates localized weak zones and prevents optimal matrix densification [30]. These findings suggest that incorporating an optimal dosage of NA is effective in minimizing water absorption and improving the durability characteristics of GPC. Beyond this dosage, excessive nanoparticle content may lead to microstructural inconsistencies, limiting the beneficial effects on permeability.

Water absorption of different GPC mixes.

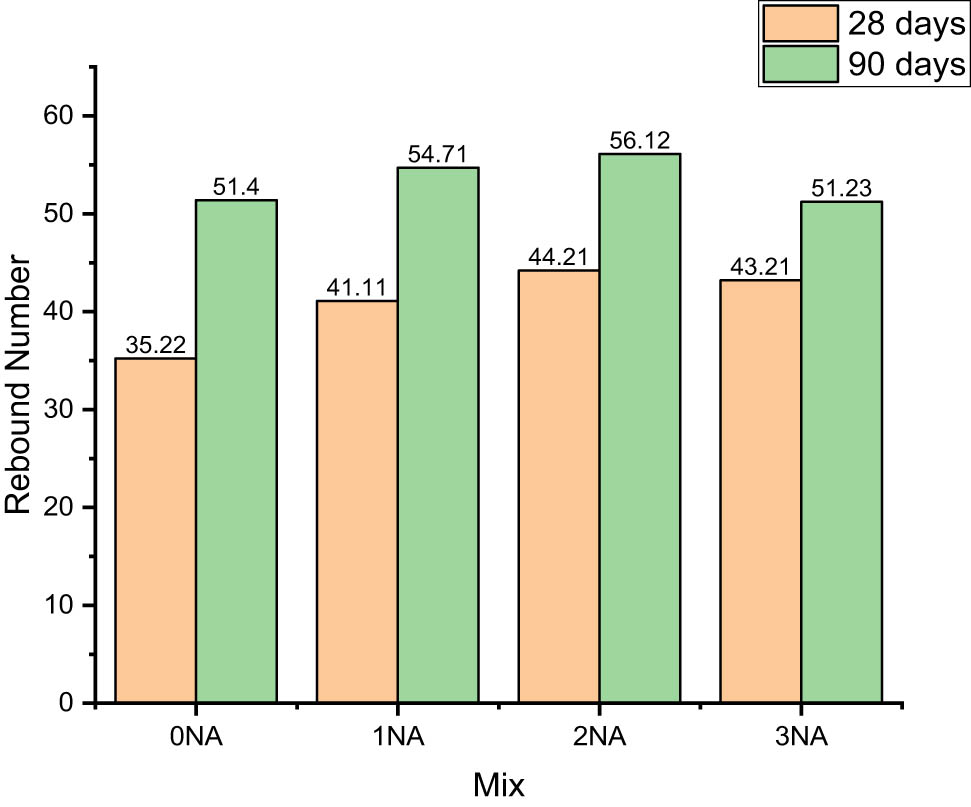

3.9 Rebound hammer (RH) test

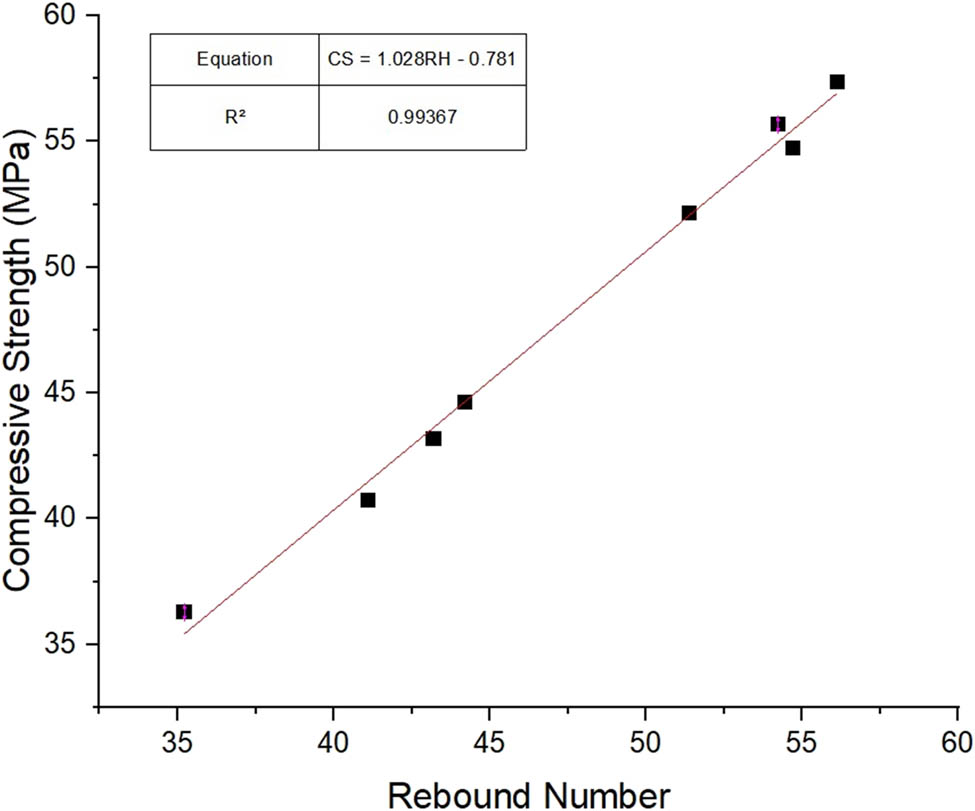

Figure 11 shows the results of the RH test performed on GPC with or without NA. It was noticed that RN increases with an increase in dosage of NA in concrete up to 2% and then starts decreasing. The maximum value of RN is observed after the incorporation of 2% NA in GPC cured for 28 and 90 days, respectively. The increment in the RN due to the increase in the dosage of NA is due to the formation of a denser and more compact GPC incorporated with the nanomaterial as a filler. The calibration curve of RN vs CS is shown in Figure 12. The relationship between the CS and RN is given by the following equation:

Rebound numbers of different GPC mixes.

Relationship between the RH and CS of GPC.

Eight mean observations were used in the development of the relationship between CS and RN. The coefficient of correlation (R 2) was found to be 0.99367.

The improved microstructure and enhanced ITZ due to NA and GGBS contribute to higher resistance against mechanical impact, as observed in the Hammer test [77–79]. The improved bonding and reduced porosity result in enhanced energy absorption capacity, making the concrete more resistant to surface deterioration under repeated impact loading [78,80].

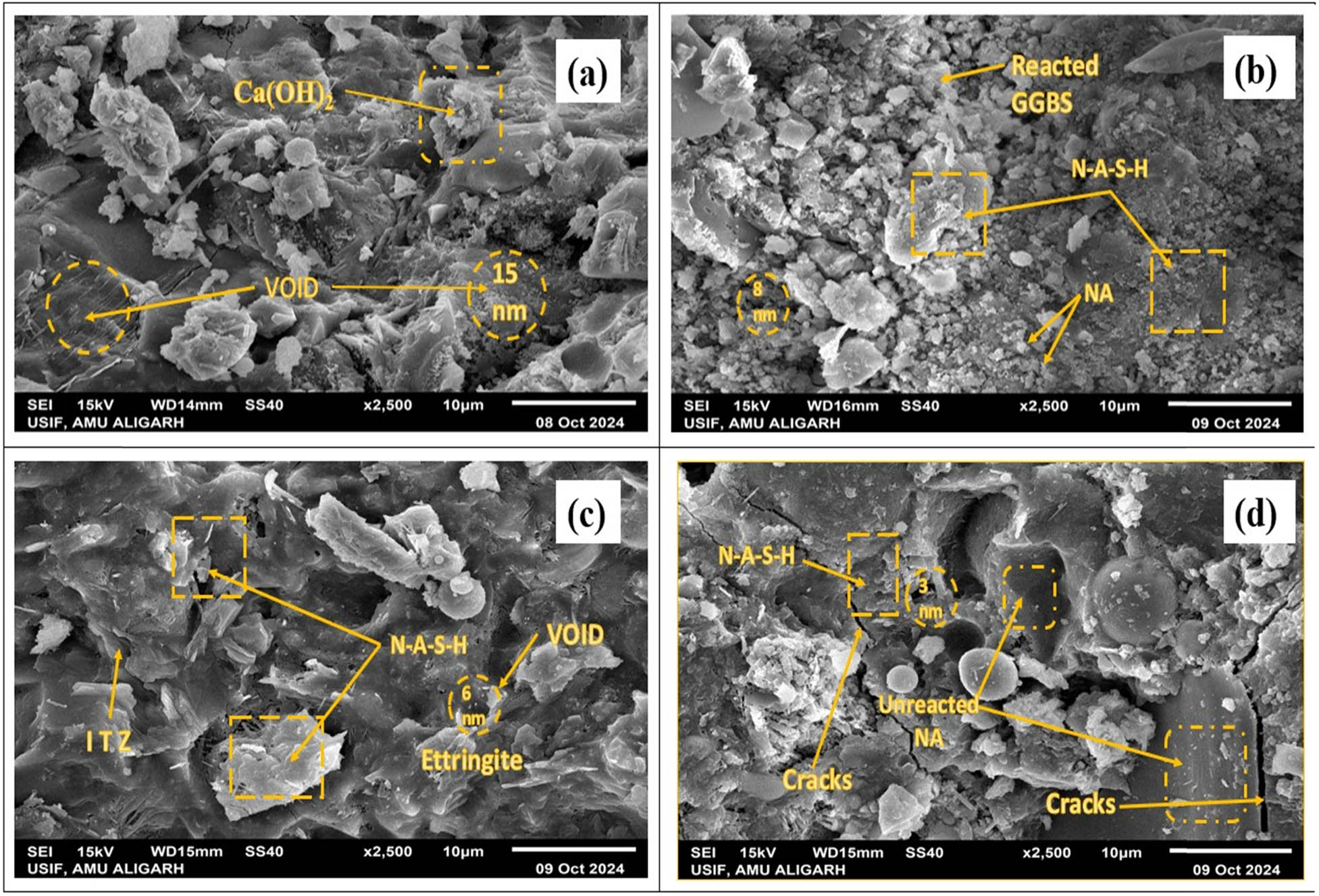

3.10 SEM analysis

Figure 13 shows the SEM analysis results of GPC with or without NA. It was noticed that with a very small amount of NA incorporation, the polymerization rate increased due to the formation of the extra N–A–S–H gel, resulting in an enhancement in the strength of GPC. The microstructure of GPC is improved due to the filling capacity of NA, which makes GPC denser. It was noticed from the SEM results that pores were eliminated in the NA-incorporated GPC. However, in GPC with 3% NA, the presence of unreacted nanomaterial results in a decrease in the strength of GPC. The presence of unreacted NA in the microstructure of GPC can be attributed to several factors, including incomplete geopolymerization due to insufficient dissolution of NA in the alkaline medium, improper dispersion leading to particle agglomeration, and excess dosage exceeding the optimal reactivity threshold. These residual particles can act as weak zones, disrupting the uniform gel structure and leading to the reduction in strength. Similar observations have been reported in previous studies where nanoscale materials, when not optimally dispersed or reacted, negatively affected the microstructure and mechanical performance of GPC [23].

SEM results of GPC incorporated with (a) 0NA, (b) 1NA, (c) 2NA, and (c) 3NA.

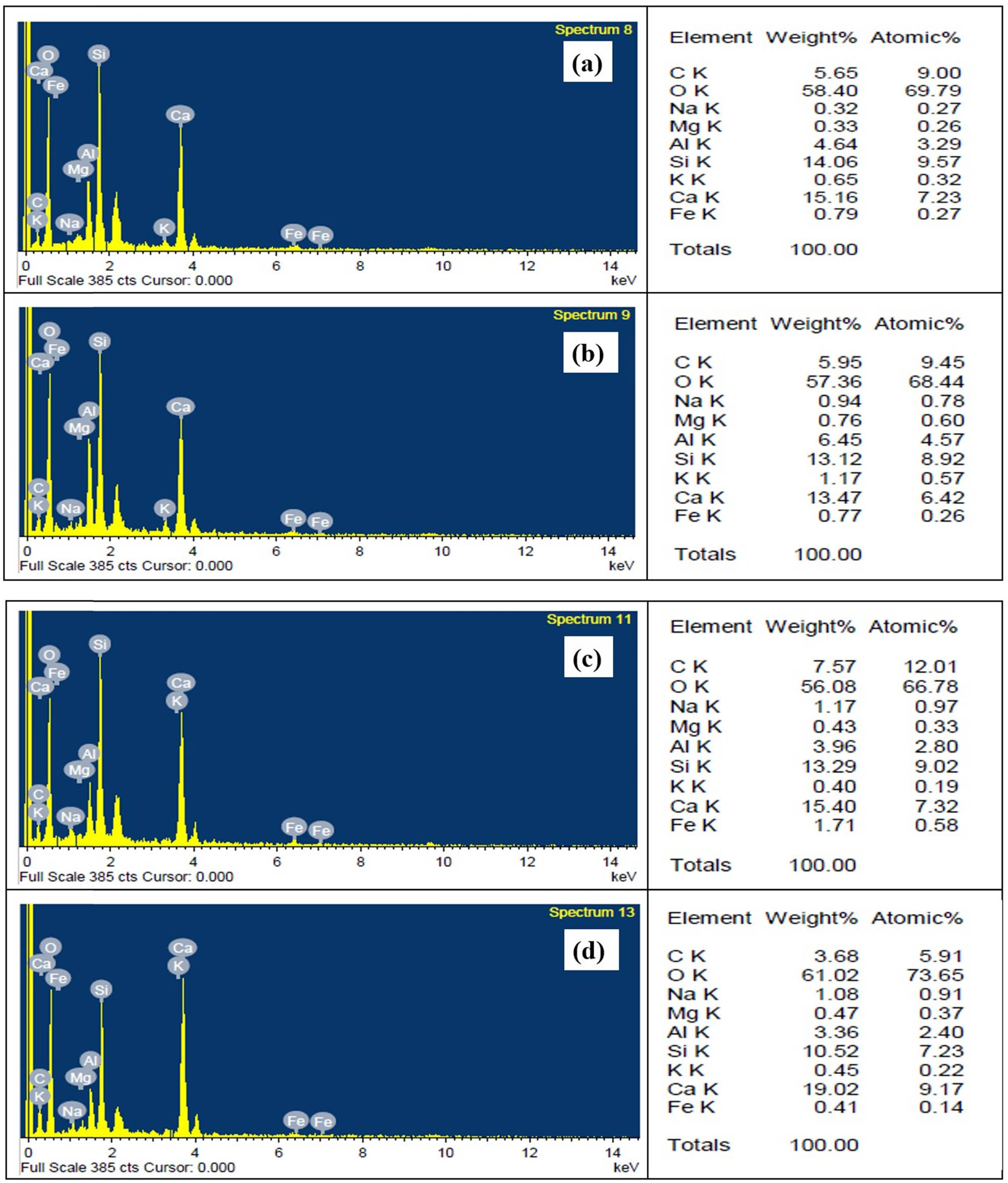

Non-reacted gaps are present with controlled GPC, as observed in Figure 13. It was noted from the SEM results that the average size of pores was 15 nm in GPC without NA, which decreased to 8, 6, and 3 nm for the GPC incorporated with 1, 2, and 3% NA. Hence, the optimum dosage of incorporation of NA in GPC is 2%, which is also observed during the morphology analysis. Therefore, we can conclude that the SEM analysis revealed that while 2% NA incorporation resulted in a dense and compact geopolymer matrix due to effective particle dispersion and enhanced N–A–S–H gel formation, the microstructure of 3% NA-based GPC exhibited certain inconsistencies. The presence of excessive NA led to the formation of agglomerated clusters, reducing the effective interaction between nanoparticles and the geopolymer binder. These agglomerates create weak zones in the matrix, impeding the uniform development of the geopolymer gel phase and leading to localized stress concentrations under loading conditions [43]. Furthermore, excessive NA can interfere with the geopolymerization reaction by increasing viscosity, limiting the mobility of reactive species, and consequently reducing the extent of gel formation [81]. Similar observations have been reported in previous studies, where higher nanomaterial dosages beyond an optimal level resulted in reduced mechanical performance due to poor particle dispersion and formation of microvoids in the matrix [71,81]. Figure 14 shows the EDX results of GPC incorporated with or without NA. The EDX study clearly shows the change in the chemical composition of the reacting compounds during the polymerization reaction. The EDX analysis further supports the observed decrease in strength at 3% NA. A noticeable reduction in the Si/Al ratio was observed at this dosage, indicating a shift in the geopolymer gel composition. The highest value of the Si/Al ratio was 3.35 for the GPC incorporated with 2% dosage of NA, followed by Si/Al ratios of 3.03, 2.03, and 3.13 for the GPC incorporated with 0, 1, and 3% dosage of NA. These results follow the trend of improvement in the CS of GPC incorporated with or without NA. While an optimal Si/Al ratio enhances the formation of stable N–A–S–H and C–A–S–H gels, an excessive alumina content can disrupt this balance, leading to a lower degree of polymerization and reduced gel connectivity [82]. Additionally, the presence of unreacted NA particles was identified, confirming that beyond a threshold dosage, excess nanoparticles do not effectively participate in the reaction but rather act as inert fillers, diminishing the overall bonding strength within the matrix [30]. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing NA dosage to ensure efficient utilization of nanomaterials in enhancing the mechanical properties.

EDX results of GPC incorporated with (a) 0NA, (b) 1NA, (c) 2NA, and (d) 3NA.

From Figure 14, it was noticed that EDX results of the GPC samples did not show significant variation in elemental composition among different specimens. This consistency can be attributed to the similar chemical nature of the base materials, the homogeneous dispersion of NA, and the limitations of EDX in detecting minor compositional variations at a nanoscale level.

4 Conclusion

After careful experimental study on the mechanical properties, durability properties, and microstructure analysis of GPC incorporated with NA, the conclusion of this study is as follows:

The incorporation of NA results in a decrease in the slump value of GPC, which can be controlled by the incorporation of the optimum dosage of SP in GPC. A similar influence of NA is observed on the setting time of GPC.

The mechanical properties of GPC are increased with an increase in dosage of NA up to 2%. The highest CS, STS, and FS values were 57.36, 5.81, and 5.59 MPa, which were achieved after incorporation of 2% NA in GPC cured for 90 days.

NA-incorporated GPC performs well under exposure to harmful alkaline chemicals. During the exposure to 6% NaCl and 6% Na2SO4 for 90 days, the maximum increase in strength of up to 6.80 and 3.38% was observed at 2 and 3% dosage of NA, respectively.

GPC behaves well after exposure to harmful acidic chemicals. During the exposure to 6% HCl and 6% H2SO4 for 90 days, the maximum increase in strength of up to 10.55 and 9.84% was observed at 2% NA dosage incorporation in GPC.

The sorptivity among all GPC specimens cured is minimal, primarily attributable to capillary forces driving absorption. However, significant variations in sorptivity emerge at later stages, predominantly stemming from the pore-filling effects of NA in GPC. The water absorption is reduced with an increase in the dosage of NA in concrete. This is due to the non-porous nature of the dense and compact NA-incorporated GPC.

The formation of the extra N–A–S–H gel after incorporation of NA results in an enhancement in the strength of GPC. The microstructure of GPC is improved due to the filling capacity of NA, which makes GPC denser.

Future studies can explore the combined effect of NA with other nanomaterials, such as nano-silica, nano-titanium dioxide, or carbon nanotubes, to further enhance the mechanical and durability properties of GPC.

Extensive long-term durability studies, including exposure to real-world environmental conditions such as freeze–thaw cycles, marine environments, and carbonation, should be conducted to validate the laboratory findings and assess the practical applicability of NA-incorporated GPC.

Further research is needed to investigate the influence of alternative curing methods, such as ambient curing or microwave curing, to improve the geopolymerization process and enhance the mechanical performance of NA-incorporated GPC while reducing energy consumption.

Future research should focus on the cost–benefit analysis of NA incorporation in GGBS-based GPC to assess its economic viability for large-scale use. Optimizing dosage levels for cost-effective enhancement of mechanical and durability properties are essential.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding of the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia through Project Number RG24-S0129.

-

Funding information: The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding of the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia, through Project Number: RG24-S0129.

-

Author contributions: Neha Sharma: conceptualization, methodology, writing – original draft, and writing; Seema: investigation and resources; Afzal Husain Khan: conceptualization, validation, supervision, writing, reviewing, and editing; Sagar Paruthi: visualization, data curation, and writing – original draft; Ali Almalki: supervision, writing, reviewing, and editing; Abdullah M Zeyad: supervision, writing, reviewing, and editing; and Ahmed A. El-Abbasy: supervision, writing, reviewing, and editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Amer, I., M. Kohail, M. El-Feky, A. Rashad, and M. A. Khalaf. Evaluation of using cement in alkali-activated slag concrete. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, Vol. 9, No. 5, 2020, pp. 245–248.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Mayhoub, O. A., E. S. A. Nasr, Y. A. Ali, and M. Kohail. The influence of ingredients on the properties of reactive powder concrete: A review. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2021, pp. 145–158.10.1016/j.asej.2020.07.016Search in Google Scholar

[3] El-Tair, A. M., R. Bakheet, M. El-Feky, M. Kohail, and M. I. Serag. Improving the microstructure and the strength of alkali activated slag mortar under ambient temperature. International Journal of Scientific and Technology Research, Vol. 9, 2020, pp. 1092–1099.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Assi, L. N., Y. A. Al-Hamadani, E. E. Deaver, V. Soltangharaei, P. Ziehl, and Y. Yoon. Effect of sonicated deionized water on the early age behavior of portland cement-based concrete and paste. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 247, 2020, id. 118571.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118571Search in Google Scholar

[5] Shilar, F. A., S. V. Ganachari, V. B. Patil, T. Yunus Khan, A. Saddique Shaik, and M. Azam Ali. Exploring the potential of promising sensor technologies for concrete structural health monitoring. Materials, Vol. 17, No. 10, 2024, id. 2410.10.3390/ma17102410Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[6] Çelikten, S., M. Sarıdemir, and İ. Ö. Deneme. Mechanical and microstructural properties of alkali-activated slag and slag + fly ash mortars exposed to high temperature. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 217, 2019, pp. 50–61.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.05.055Search in Google Scholar

[7] Chau-Khun, M., A. A. Zawawi, and O. Wahid. Structural and material performance of geopolymer concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 186, 2018, pp. 90–102.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.111Search in Google Scholar

[8] Shilar, F. A., S. V. Ganachari, and V. B. Patil. Investigation of the effect of granite waste powder as a binder for different molarity of geopolymer concrete on fresh and mechanical properties. Materials Letters, Vol. 309, 2022, id. 131302.10.1016/j.matlet.2021.131302Search in Google Scholar

[9] Shilar, F. A., S. V. Ganachari, V. B. Patil, B. Bhojaraja, T. Y. Khan, and N. Almakayeel. A review of 3D printing of geopolymer composites for structural and functional applications. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 400, 2023, id. 132869.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132869Search in Google Scholar

[10] Asim, N., M. Alghoul, M. Mohammad, M. H. Amin, M. Akhtaruzzaman, N. Amin, et al. Emerging sustainable solutions for depollution: Geopolymers. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 199, 2019, pp. 540–548.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.12.043Search in Google Scholar

[11] Reddy, M. S., P. Dinakar, and B. H. Rao. Mix design development of fly ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag based geopolymer concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 20, 2018, pp. 712–722.10.1016/j.jobe.2018.09.010Search in Google Scholar

[12] Shilar, F. A., S. V. Ganachari, V. B. Patil, K. S. Nisar, A.-H. Abdel-Aty, and I. Yahia. Evaluation of the effect of granite waste powder by varying the molarity of activator on the mechanical properties of ground granulated blast-furnace slag-based geopolymer concrete. Polymers, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2022, id. 306.10.3390/polym14020306Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[13] Nema, D. Compaction and strength characteristics of Lime activated flyash with GGBS as an admixture, Doctoral dissertation, National Institute of Technology, Rourkela, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[14] Murmu, A. L., N. Dhole, and A. Patel. Stabilisation of black cotton soil for subgrade application using fly ash geopolymer. Road Materials and Pavement Design, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2020, pp. 867–885.10.1080/14680629.2018.1530131Search in Google Scholar

[15] Jiang, C., A. Wang, X. Bao, T. Ni, and J. Ling. A review on geopolymer in potential coating application: Materials, preparation and basic properties. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 32, 2020, id. 101734.10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101734Search in Google Scholar

[16] Toghroli, A., P. Mehrabi, M. Shariati, N. T. Trung, S. Jahandari, and H. Rasekh. Evaluating the use of recycled concrete aggregate and pozzolanic additives in fiber-reinforced pervious concrete with industrial and recycled fibers. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 252, 2020, id. 118997.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118997Search in Google Scholar

[17] Zhang, P., Z. Gao, J. Wang, J. Guo, S. Hu, and Y. Ling. Properties of fresh and hardened fly ash/slag based geopolymer concrete: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 270, 2020, id. 122389.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122389Search in Google Scholar

[18] Sarkar, M., T. Chowdhury, B. Chattopadhyay, R. Gachhui, and S. Mandal. Autonomous bioremediation of a microbial protein (bioremediase) in Pozzolana cementitious composite. Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 49, 2014, pp. 4461–4468.10.1007/s10853-014-8143-1Search in Google Scholar

[19] Sarkar, M., N. Alam, B. Chaudhuri, B. Chattopadhyay, and S. Mandal. Development of an improved E. coli bacterial strain for green and sustainable concrete technology. RSC Advances, Vol. 5, No. 41, 2015, pp. 32175–32182.10.1039/C5RA02979ASearch in Google Scholar

[20] Hussin, M., M. Bhutta, M. Azreen, P. Ramadhansyah, and J. Mirza. Performance of blended ash geopolymer concrete at elevated temperatures. Materials and Structures, Vol. 48, 2015, pp. 709–720.10.1617/s11527-014-0251-5Search in Google Scholar

[21] Paruthi, S., I. Rahman, A. Husain, A. H. Khan, A.-M. Manea-Saghin, and E. Sabi. A comprehensive review of nano materials in geopolymer concrete: Impact on properties and performance. Developments in the Built Environment, Vol. 16, 2023, id. 100287.10.1016/j.dibe.2023.100287Search in Google Scholar

[22] Paruthi, S., I. Rahman, A. Husain, M. A. Hasan, and A. H. Khan. Effects of chemicals exposure on the durability of geopolymer concrete incorporated with silica fumes and nano-sized silica at varying curing temperatures. Materials, Vol. 16, No. 18, 2023, id. 6332.10.3390/ma16186332Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[23] Arab MAE-SMohamed, A. S., M. K. Taha, and A. Nasr. Microstructure, durability and mechanical properties of high strength geopolymer concrete containing calcinated nano-silica fume/nano-alumina blend. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 472, 2025, id. 140903.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.140903Search in Google Scholar

[24] Sastry, K. G. K., P. Sahitya, and A. Ravitheja. Influence of nano TiO2 on strength and durability properties of geopolymer concrete. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 45, 2021, pp. 1017–1025.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.03.139Search in Google Scholar

[25] Kishore, K., M. N. Sheikh, and M. N. Hadi. Doped multi-walled carbon nanotubes and nanoclay based-geopolymer concrete: An overview of current knowledge and future research challenges. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 154, 2024, id. 105774.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2024.105774Search in Google Scholar

[26] Guo, S., X. Qiao, T. Zhao, and Y.-S. Wang. Preparation of highly dispersed graphene and its effect on the mechanical properties and microstructures of geopolymer. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 32, No. 11, 2020, id. 04020327.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0003424Search in Google Scholar

[27] Chiranjeevi, K., M. Abraham, B. Rath, and T. Praveenkumar. Enhancing the properties of geopolymer concrete using nano-silica and microstructure assessment: a sustainable approach. Scientific Reports, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2023, id. 17302.10.1038/s41598-023-44491-ySearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[28] Dheyaaldin, M. H., M. A. Mosaberpanah, and R. Alzeebaree. The effect of nano-silica and nano-alumina with polypropylene fiber on the chemical resistance of alkali-activated mortar. Sustainability, Vol. 14, No. 24, 2022, id. 16688.10.3390/su142416688Search in Google Scholar

[29] Wong, L. S. Durability performance of geopolymer concrete: A review. Polymers, Vol. 14, No. 5, 2022, id. 868.10.3390/polym14050868Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[30] Phoo-ngernkham, T., P. Chindaprasirt, V. Sata, S. Hanjitsuwan, and S. Hatanaka. The effect of adding nano-SiO2 and nano-Al2O3 on properties of high calcium fly ash geopolymer cured at ambient temperature. Materials & Design, Vol. 55, 2014, pp. 58–65.10.1016/j.matdes.2013.09.049Search in Google Scholar

[31] Assaedi HS, D. and M. Olawale. Impact of nano-alumina on the mechanical characterization of PVA fibre-reinforced geopolymer composites. Journal of Taibah University for Science, Vol. 16, No. 1, 2022, pp. 828–835.10.1080/16583655.2022.2119735Search in Google Scholar

[32] Chindaprasirt, P. and K. Somna. Effect of addition of microsilica and nanoalumina on compressive strength and products of high calcium fly ash geopolymer with low concentration NaOH. Advanced Materials Research, Vol. 1103, 2015, pp. 29–36.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1103.29Search in Google Scholar

[33] Deb, P. S., P. K. Sarker, and S. Barbhuiya. Effects of nano-silica on the strength development of geopolymer cured at room temperature. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 101, 2015, pp. 675–683.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.10.044Search in Google Scholar

[34] Oliveira, L., A. Azevedo, M. Marvila, C. Vieira, N. Cerqueira, and S. Monteiro. Development of metakaolin-based geopolymer mortar and the flue gas desulfurization (FGD) waste. Characterization of Minerals, Metals, and Materials 2022, Springer, Cham, 2022, pp. 323–331.10.1007/978-3-030-92373-0_31Search in Google Scholar

[35] Zidi, Z., M. Ltifi, and I. Zafar. Characterization of nano-silica local metakaolin based-geopolymer: Microstructure and mechanical properties. Open Journal of Civil Engineering, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2020, pp. 143–161.10.4236/ojce.2020.102013Search in Google Scholar

[36] Sun, K., X. Peng, S. Wang, L. Zeng, P. Ran, and G. Ji. Effect of nano-SiO2 on the efflorescence of an alkali-activated metakaolin mortar. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 253, 2020, id. 118952.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118952Search in Google Scholar

[37] Grisolia, A., G. Dell’Olio, A. Spadafora, M. De Santo, C. Morelli, A. Leggio, et al. Hybrid polymer-silica nanostructured materials for environmental remediation. Molecules, Vol. 28, No. 13, 2023, id. 5105.10.3390/molecules28135105Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[38] Bakharev, T. Geopolymeric materials prepared using Class F fly ash and elevated temperature curing. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 35, No. 6, 2005, pp. 1224–1232.10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.06.031Search in Google Scholar

[39] Davidovits, J. Geopolymer chemistry and applications, Geopolymer Institute, 2nd Edn, 2008.Search in Google Scholar

[40] Salih, M. A., A. A. A. Ali, and N. Farzadnia. Characterization of mechanical and microstructural properties of palm oil fuel ash geopolymer cement paste. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 65, 2014, pp. 592–603.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.05.031Search in Google Scholar

[41] IS 12089 (1987). Specification for granulated slag for the manufacture of Portland slag cement [CED 2: Cement and concrete], Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 1987.Search in Google Scholar

[42] Reddy, N. A. K. and K. Ramujee. Comparative study on mechanical properties of fly ash & GGBFS based geopolymer concrete and OPC concrete using nano-alumina. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 60, 2022, pp. 399–404.10.1016/j.matpr.2022.01.260Search in Google Scholar

[43] Arshad, M., A. Raza, Q. U. Z. Khan, N. B. Kahla, and A. B. Elhag. Evaluation of mechanical and microstructural characterization of microfiber-reinforced nanocomposites comprising nano-alumina. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, Vol. 49, No. 4, 2024, pp. 5079–5094.10.1007/s13369-023-08368-6Search in Google Scholar

[44] Paruthi, S., A. Husain, P. Alam, A. H. Khan, M. A. Hasan, and H. M. Magbool. A review on material mix proportion and strength influence parameters of geopolymer concrete: Application of ANN model for GPC strength prediction. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 356, 2022, id. 129253.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129253Search in Google Scholar

[45] Olivia, M. and H. Nikraz. Strength and water penetrability of fly ash geopolymer concrete. Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Vol. 6, No. 7, 2011, pp. 70–78.Search in Google Scholar

[46] Temuujin, J., R. Williams, and A. Van Riessen. Effect of mechanical activation of fly ash on the properties of geopolymer cured at ambient temperature. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, Vol. 209, No. 12–13, 2009, pp. 5276–5280.10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2009.03.016Search in Google Scholar

[47] Hardjito, D., S. E. Wallah, D. M. Sumajouw, and B. V. Rangan. On the development of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Materials Journal, Vol. 101, No. 6, 2004, pp. 467–472.10.1080/13287982.2005.11464946Search in Google Scholar

[48] Rangan, B. V. Fly ash-based geopolymer concrete, Proceedings of the International Workshop on Geopolymer Cement and Concrete, Allied publishers Private Limited, 2008, pp. 68–106.10.1201/9781420007657.ch26Search in Google Scholar

[49] IS 1199 (1959). Methods of sampling and analysis of concrete [CED 2: Cement and concrete], Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[50] IS 8142 (1976). Method of rest for determining the setting time of concrete by penetration resistance [CED 2: Cement and concrete], Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[51] IS 516 (1959). Method of tests for strength of concrete [CED 2: Cement and concrete], Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 2004.Search in Google Scholar

[52] IS 5816 (1999). Method of test splitting tensile strength of concrete [CED 2: Cement and concrete], Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 2004.Search in Google Scholar

[53] Lakhssassi, M. Z., S. Alehyen, M. El Alouani, and M. Taibi. The effect of aggressive environments on the properties of a low calcium fly ash based geopolymer and the ordinary Portland cement pastes. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 13, 2019, pp. 1169–1177.10.1016/j.matpr.2019.04.085Search in Google Scholar

[54] Luhar, S., I. Luhar, and R. Gupta. Durability performance evaluation of green geopolymer concrete. European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering, Vol. 26, No. 10, 2022, pp. 4297–4345.10.1080/19648189.2020.1847691Search in Google Scholar

[55] Zhao, X., H. Wang, B. Zhou, H. Gao, and Y. Lin. Resistance of soda residue–fly ash based geopolymer mortar to acid and sulfate environments. Materials, Vol. 14, 2021, id. 785. Notes: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published …; 2021.10.3390/ma14040785Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[56] ASTM C642-21. Standard test method for density, absorption, and voids in hardened concrete, American Society for Testing and Materials, America, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[57] IS 13311-2 (1992). Method of non-destructive testing of concrete-methods of test, Part 2: Rebound hammer [CED 2: Cement and concrete], Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, 2013.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Nazari, A. and S. Riahi. The effects of TiO2 nanoparticles on physical, thermal and mechanical properties of concrete using ground granulated blast furnace slag as binder. Materials Science and Engineering: A, Vol. 528, No. 4–5, 2011, pp. 2085–2092.10.1016/j.msea.2010.11.070Search in Google Scholar

[59] Quercia, G. and H. Brouwers, eds., Application of nano-silica (nS) in concrete mixtures. 8th fib International Ph D Symposium in Civil Engineering, Lyngby, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Das, R., S. Panda, A. S. Sahoo, and S. K. Panigrahi. Effect of superplasticizer types and dosage on the flow characteristics of GGBFS based self-compacting geopolymer concrete. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 103, 2024, pp. 11–21.10.1016/j.matpr.2023.06.339Search in Google Scholar

[61] Sharif, H. H. Fresh and mechanical characteristics of eco-efficient GPC incorporating nano-silica: An overview. Kurdistan Journal of Applied Research, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2021, pp. 64–74.10.24017/science.2021.2.6Search in Google Scholar

[62] Chindaprasirt, P., P. De Silva, K. Sagoe-Crentsil, and S. Hanjitsuwan. Effect of SiO2 and Al2O3 on the setting and hardening of high calcium fly ash-based geopolymer systems. Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 47, 2012, pp. 4876–4883.10.1007/s10853-012-6353-ySearch in Google Scholar

[63] Zhang, A., W. Yang, Y. Ge, Y. Du, and P. Liu. Effects of nano-SiO2 and nano-Al2O3 on mechanical and durability properties of cement-based materials: A comparative study. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 34, 2021, id. 101936.10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101936Search in Google Scholar

[64] Zhang, A., Y. Ge, W. Yang, X. Cai, and Y. Du. Comparative study on the effects of nano-SiO2, nano-Fe2O3 and nano-NiO on hydration and microscopic properties of white cement. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 228, 2019, id. 116767.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.116767Search in Google Scholar

[65] Zidi, Z., M. Ltifi, Z. Ben Ayadi, and L. El Mir. Synthesis of nano-alumina and their effect on structure, mechanical and thermal properties of geopolymer. Journal of Asian Ceramic Societies, Vol. 7, No. 4, 2019, pp. 524–535.10.1080/21870764.2019.1676498Search in Google Scholar

[66] Gowda, R., H. Narendra, B. Nagabushan, D. Rangappa, and R. Prabhakara. Investigation of nano-alumina on the effect of durability and micro-structural properties of the cement mortar. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 4, No. 11, 2017, pp. 12191–12197.10.1016/j.matpr.2017.09.149Search in Google Scholar

[67] Li, Z., H. Wang, S. He, Y. Lu, and M. Wang. Investigations on the preparation and mechanical properties of the nano-alumina reinforced cement composite. Materials Letters, Vol. 60, No. 3, 2006, pp. 356–359.10.1016/j.matlet.2005.08.061Search in Google Scholar

[68] Farhan, N. A., M. N. Sheikh, and M. N. Hadi. Investigation of engineering properties of normal and high strength fly ash based geopolymer and alkali-activated slag concrete compared to ordinary Portland cement concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 196, 2019, pp. 26–42.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.083Search in Google Scholar

[69] Younus, S. J., M. A. Mosaberpanah, and R. Alzeebaree. The performance of alkali-activated self-compacting concrete with and without nano-Alumina. Sustainability, Vol. 15, No. 3, 2023, id. 2811.10.3390/su15032811Search in Google Scholar

[70] Parashar, A. K., P. Sharma, and N. Sharma. Effect on the strength of GGBS and fly ash based geopolymer concrete. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 62, 2022, pp. 4130–4133.10.1016/j.matpr.2022.04.662Search in Google Scholar

[71] Beilin, D. and P. Kudryavtsev. Effect of nano-alumina on physical-mechanical properties of geopolymer materials. Scientific Israel: Technological Advantages, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2024, pp. 5.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Orakzai, M. A. Hybrid effect of nano-alumina and nano-titanium dioxide on Mechanical properties of concrete. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 14, 2021, id. e00483.10.1016/j.cscm.2020.e00483Search in Google Scholar

[73] Rani, J. J. and H. Gladston. Study on durability of fly ash geo-polymer concrete with nano alumina. Matéria (Rio de Janeiro), Vol. 29, 2024, id. e20240412.10.1590/1517-7076-rmat-2024-0412Search in Google Scholar

[74] Xie, J., J. Zhao, J. Wang, C. Wang, P. Huang, and C. Fang. Sulfate resistance of recycled aggregate concrete with GGBS and fly ash-based geopolymer. Materials, Vol. 12, No. 8, 2019, id. 1247.10.3390/ma12081247Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[75] Xavier, C. and A. Rahim. Nano aluminium oxide geopolymer concrete: An experimental study. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 56, 2022, pp. 1643–1647.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.10.070Search in Google Scholar

[76] Ali, B. Evaluation of alkali-activated mortar incorporating combined and uncombined fly ash and GGBS enhanced with nano alumina. Civil Engineering Journal, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2024, pp. 902–914.10.28991/CEJ-2024-010-03-016Search in Google Scholar

[77] Divvala, S. Early strength properties of geopolymer concrete composites: An experimental study. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 47, 2021, pp. 3770–3777.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.03.002Search in Google Scholar

[78] Shilar, F. A., S. V. Ganachari, V. B. Patil, S. Javed, T. Y. Khan, and R. U. Baig. Assessment of destructive and nondestructive analysis for GGBS based geopolymer concrete and its statistical analysis. Polymers, Vol. 14, No. 15, 2022, id. 3132.10.3390/polym14153132Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[79] Ashok, K., B. K. Rao and B. S. C. Kumar, eds., Experimental study on metakaolin & nano alumina based concrete. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, IOP Publishing, 2021.10.1088/1757-899X/1091/1/012055Search in Google Scholar

[80] Paruthi, S., I. Rahman, A. H. Khan, N. Sharma, and A. Alyaseen. Strength, durability, and economic analysis of GGBS-based geopolymer concrete with silica fume under harsh conditions. Scientific Reports, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2024, id. 31572.10.1038/s41598-024-77801-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[81] Alomayri, T. Experimental study of the microstructural and mechanical properties of geopolymer paste with nano material (Al2O3). Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 25, 2019, id. 100788.10.1016/j.jobe.2019.100788Search in Google Scholar

[82] Ziada, M. The effect of nano-TiO2 and nano-Al2O3 on mechanical, microstructure properties and high-temperature resistance of geopolymer mortars. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, Vol. 50, 2025, pp. 12977–12996.10.1007/s13369-024-09570-wSearch in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Towards sustainable concrete pavements: a critical review on fly ash as a supplementary cementitious material

- Optimizing rice husk ash for ultra-high-performance concrete: a comprehensive review of mechanical properties, durability, and environmental benefits

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles