Abstract

To optimize the modifying effect of inorganic additives by using organic modifier, this study selected layered double hydroxides (LDHs) and ultraviolet (UV) absorbers as anti-aging agents to prepare modified asphalt. The anti-aging performance of modified asphalt was evaluated using a weathering tester. The influence of the composite modification effects of organic–inorganic modifiers on the pavement performance of asphalt binders was investigated through conventional tests. Dynamic shear rheometer tests were conducted to examine the performance grade classification of the composite anti-aging-modified asphalt. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was employed to analyze the variations in functional group composition of the composite-modified asphalt. Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations were utilized to elucidate the changes of composite-modified asphalt at the molecular level under UV aging. The results indicate that the incorporation of UV absorbers significantly mitigates the adverse effects of LDHs on the physical properties of asphalt, while their synergistic modification enhances the anti-aging performance of the modified asphalt. Due to the addition of UV absorbers, the solubility difference between the composite modifier and asphalt improves compared to that of LDHs alone. Moreover, as the proportion of UV absorbers increases, the solubility difference gradually decreases, enhancing the thermal stability of the asphalt system.

1 Introduction

During long-term service, asphalt pavements are susceptible to aging under environmental factors such as ultraviolet (UV) radiation and thermo-oxygen coupling effects, leading to degradation of mechanical properties and consequently shortened service life [1,2]. To retard the asphalt aging process, organic UV absorbers (such as benzotriazole and benzophenone compounds) and inorganic layered double hydroxides (LDHs) have been widely used in asphalt modification [3,4]. LDHs, with their unique layered structure and UV reflection capability, can reduce UV penetration depth through physical shielding, while organic UV absorbers convert UV light into harmless heat through molecular-level energy conversion mechanisms (such as excited-state proton transfer) [5–7]. However, single modifiers have limitations: LDHs exhibit poor compatibility with asphalt and tend to agglomerate, while only reflecting partial UV bands; organic UV absorbers may fail due to insufficient thermal stability or migration loss [8–10]. Therefore, researchers have recently begun exploring organic–inorganic composite modification systems aimed at achieving more efficient aging inhibition through synergistic effects. Existing research shows that the compounding method of LDHs and UV absorbers significantly affects modification effectiveness [11]. For example, intercalating UV absorbers (such as UV-284 and salicylic acid) into LDH interlayers through anion exchange can simultaneously enhance UV absorption capacity and interlayer shielding effects [12,13]. The synergistic mechanism manifests as the residual UV light reflected by LDHs is secondarily captured by intercalated absorbers, thereby achieving “reflection–absorption” cascade protection against full-band UV radiation [14–16]. Additionally, the intercalated structure can improve the thermal stability of organic components, delaying their decomposition during high-temperature asphalt processing [17–20]. In comparison, physically blended composite modifiers, although simple to prepare, may exhibit uneven dispersion due to insufficient interfacial compatibility, resulting in lower synergistic efficiency [21,22]. Notably, performance optimization of composite modifiers also requires consideration of component ratios and interactions with the asphalt matrix [23]. For instance, excessive LDHs may exacerbate asphalt hardening and low-temperature brittleness, while excessively high concentrations of UV absorbers may interfere with asphalt colloidal stability [24–26]. Although existing studies have confirmed the synergistic anti-aging effects of LDH/UV absorber composite systems, key issues remain unresolved regarding their multiscale mechanism [20,27–29]. The molecular-scale mechanism remains unclear – the inhibitory pathway of composite modifiers on free radical chain reactions during asphalt aging lacks dynamic characterization, particularly the quantitative barrier effect of intercalated structures on reactive oxygen diffusion [30,31]. The coupling relationship between multiple properties is missing – current research primarily focuses on macroscopic rheological properties (such as performance grade [PG] grading) or single chemical indicators (such as carbonyl index [CI]), lacking correlation analysis of mechanical–chemical–structural evolution.

Based on this, this study selected LDH modifiers and UV absorbers as anti-aging modifiers to prepare modified asphalt. The anti-aging-modified asphalt was subjected to UV aging treatment using a weather resistance tester. The composite modification effects of organic–inorganic modifiers on the pavement performance of asphalt binders were investigated through three major indicator tests. The changes in failure temperature and PG grading of composite anti-aging-modified asphalt under UV aging were studied using dynamic shear tests. The variations in functional group composition and characteristic functional group indices of composite anti-aging-modified asphalt under UV aging were analyzed using Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy tests. On this basis, molecular dynamics simulations were employed to analyze the changes in solubility, mean square displacement, and other indicators of composite anti-aging-modified asphalt during the UV aging process.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

2.1.1 Additive

This study employed LDHs as inorganic anti-aging agents to prepare modified asphalt. LDHs represent a novel class of supramolecular intercalated functional materials with the general chemical formula

2.1.2 Binder

The study utilized 70# base asphalt as the fundamental binder material. In accordance with the “Test Methods for Highway Engineering Asphalt and Asphalt Mixtures” (JTG E20-2019), comprehensive performance testing was conducted on the asphalt, with the specific performance indicators detailed in Table 1.

Technical indicators of 70# base asphalt

| Test index | Results | Requirements | Test procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Softening point (°C) | 50.8 | >46 | T0606 |

| Penetration (0.1 mm) | 61.1 | 60∼80 | T0604 |

| 10°C Ductility (cm) | >100 | >20 | T0605 |

| 60°C Dynamic viscosity (Pa·s) | 218 | 218 | T0620 |

2.2 Methodology

2.2.1 Preparation process of modified asphalt

The preparation procedure of modified asphalt was conducted as follows: first, the 70# base asphalt was heated in an oven at 140°C for 1.5 h until reaching a fluid state. Approximately 400–500 g of the base asphalt was then weighed and transferred into a glass baker for subsequent use. Next, 3% (by mass of base asphalt) of either LDHs or ULDHs modifier was gradually added to the fluid asphalt in three separate increments, with each addition followed by 5 min of stirring using a glass rod to ensure preliminary homogeneity of the modifier within the asphalt matrix. After complete incorporation of the modifier, high-speed shearing was performed at 5,000 rpm for 25 min under constant temperature conditions of 150°C to achieve thorough mixing between the asphalt and modifiers. The resulting samples were designated as OMA (base asphalt), LMA (LDHs-modified asphalt), and ULMA (ULDHs-modified asphalt) for subsequent testing and analysis.

2.2.2 Treatment process of UV radiation

This study employed a weathering test chamber to conduct UV aging on asphalt binder. The UV aging process utilized UVA-340 fluorescent lamps, which emit UV radiation predominantly within the 300–400 nm wavelength range, matching the solar UV spectrum reaching the Earth’s surface (280–400 nm). By controlling the irradiation temperature and intensity, the system simulated natural sunlight exposure for accelerated weathering testing while eliminating temperature interference inherent in conventional light sources. Based on the principle of total UV radiation conservation and the irradiance power of the fluorescent lamps in the weathering chamber, the corresponding durations for laboratory-accelerated UV aging were calculated, as detailed in Table 2.

Indoor and outdoor aging time correspondence table

| Solar radiation time (month) | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV radiation time (h) | 0 | 46 | 92 | 138 | 184 |

2.2.3 Experimental method

2.2.3.1 Physical property test

According to the “Test Specification for Asphalt and Asphalt Mixtures in Highway Engineering” (JTG E20-2019) T0604-2011, the penetration test is conducted on modified asphalt at 25°C and the penetration time is 5 s. According to T0605-2011, the ductility test is conducted at the temperature of 15°C and the stretching speed of 5 cm·min−1. According to T0606-2011, the softening point test is conducted with the initial temperature of 5°C and the heating rate is 5°C·min−1.

2.2.3.2 Rheological performance test

The tests were conducted using the Smartpave 102 dynamic shear rheometer (Anton Paar). For the PG classification, the testing frequency was set at 10 rad·s−1, with an initial temperature of 40°C and incremental temperature steps of 6°C until reaching 82°C. Within the high-temperature range, continuous temperature sweep tests were performed to measure the rutting factor (|G|/sinδ) of the asphalt mastic. The high-temperature performance was evaluated based on the criterion |G|/sinδ < 1.0 kPa. The failure temperature in the PG test was determined as the temperature at which |G*|/sinδ reached 1 kPa.

2.2.3.3 FTIR spectroscopy test

The modifier and modified asphalt were analyzed using a Nicolet IS50 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The experiments were conducted via attenuated total reflectance mode, with a wavenumber range of 400–4,000 cm−1, 32 scans, and a resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.2.3.4 Molecular dynamic simulation

Molecular models of base asphalt and modified asphalt were constructed using Materials Studio 2020 software to analyze the aging resistance performance and mechanisms of modified asphalt. Currently, asphalt molecular modeling approaches are primarily classified into two categories: average molecular models and multi-component molecular models. Compared with conventional asphalt models, the multi-component molecular model provides a more refined division of asphalt components, making it one of the most advanced asphalt models currently available in the field due to its closer approximation to the actual properties of asphalt. Based on this, the AAA-1 four-component model was selected for molecular dynamics simulations in this study.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Physical property

3.1.1 Softening point

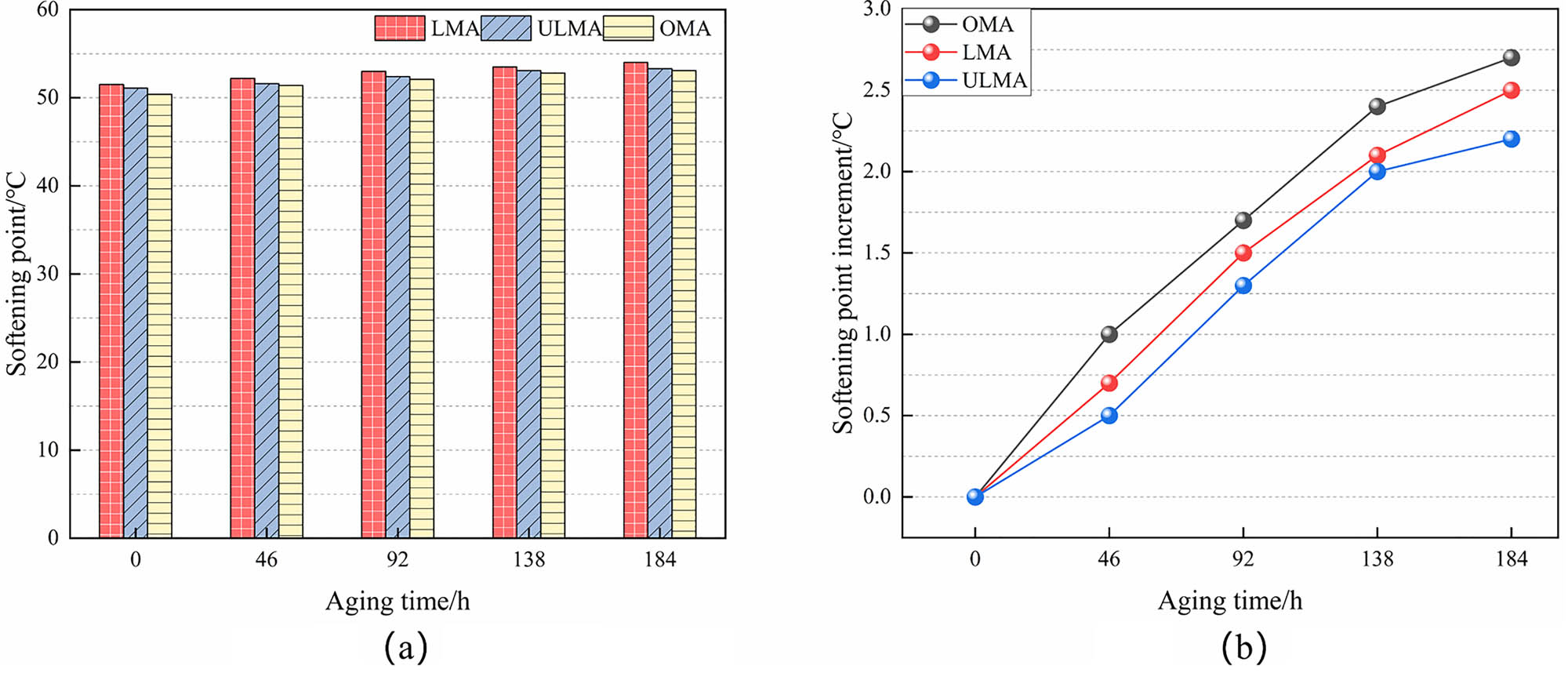

Figure 1 presents the softening point and softening point increment results for OMA, LMA, and ULMA. Analysis of Figure 1 reveals that UV aging exerts a significant influence on the softening point of asphalt binders. All three types of asphalt exhibited a gradual increase in softening point with prolonged UV aging duration. This phenomenon primarily stems from UV-induced transformation of light components (saturates and aromatics) into heavier fractions, accompanied by an increase in asphaltene content, ultimately leading to asphalt hardening. Throughout the entire UV aging cycle, both modified asphalts demonstrated higher softening points compared to the base asphalt (OMA). This observation suggests that LDHs modifiers may enhance the viscous properties of asphalt, thereby improving its high-temperature performance. Notably, the softening point increments of modified asphalts were consistently lower than those of the base asphalt, verifying the effectiveness of modifiers in enhancing aging resistance. The incorporation of LDHs and ULDHs resulted in relatively modest increases in softening points. Compared to OMA, ULMA showed softening point increases of 1.39, 0.39, 0.58, 0.57, and 0.38% at aging durations of 0, 46, 92, 138, and 184 h, respectively. In contrast, LMA exhibited greater improvements of 2.18, 1.56, 1.73, 1.33, and 1.69% at corresponding aging intervals. These results indicate that LDHs outperform ULDHs in terms of softening point elevation, demonstrating superior capability in enhancing the high-temperature deformation resistance of asphalt. The ranking of softening point increments followed the order: OMA > LMA > ULMA. The consistently lower increments observed for ULMA compared to LMA suggest that the synergistic effect of hydrotalcite–UV absorber composites provides superior anti-aging performance compared to hydrotalcite modification alone.

Softening point and softening point increment of different types of asphalt: (a) Softening point and (b) softening point increment.

3.1.2 Penetration

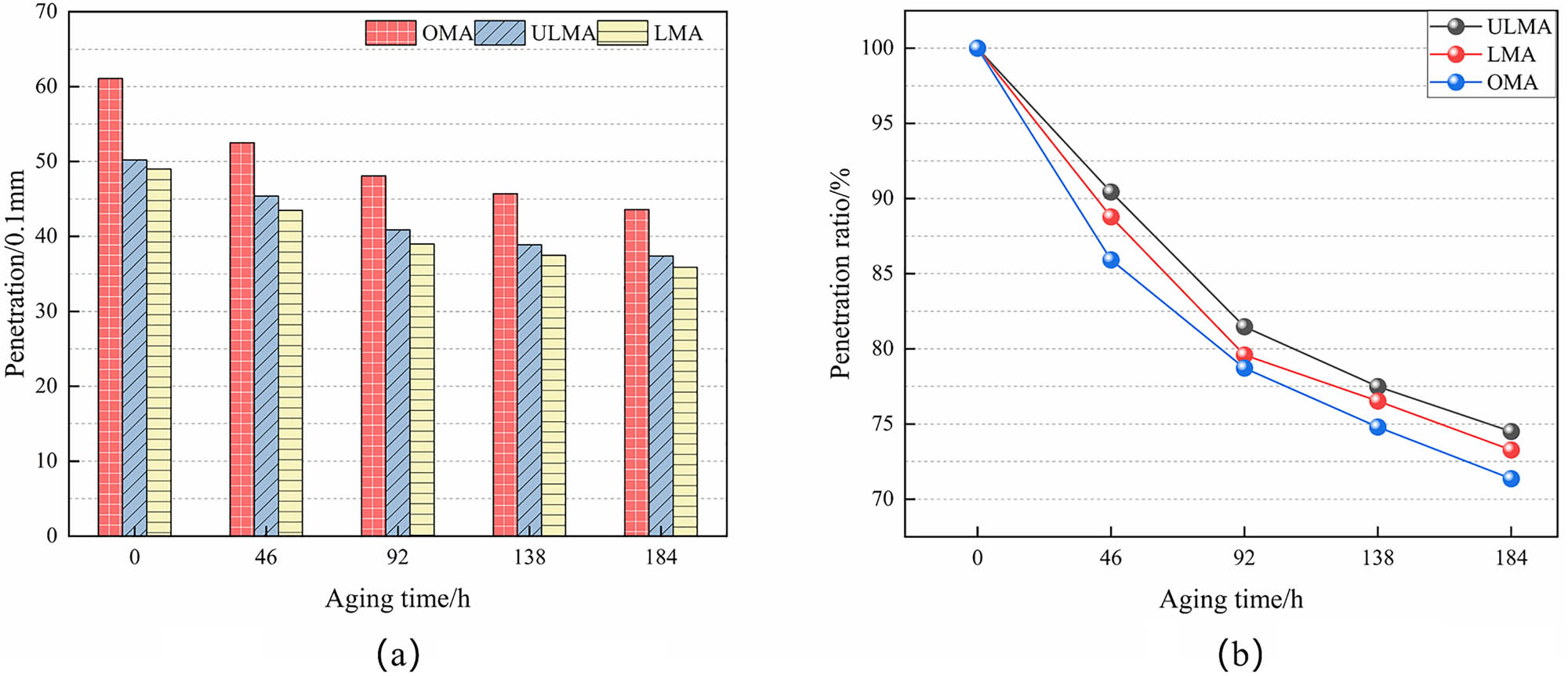

Figure 2 presents the penetration and penetration ratio results for OMA, LMA, and ULMA. As shown in Figure 2(a), the penetration of all three asphalt types gradually decreased with increasing aging severity. Notably, at all aging intervals, the modified asphalts exhibited lower penetration values than the base asphalt (OMA), attributable to the increased viscosity imparted by LDHs and ULDHs modifiers upon blending with asphalt. Analysis of Figure 2(b) reveals that the modified asphalts consistently demonstrated higher penetration ratios than OMA, confirming the efficacy of these modifiers in enhancing aging resistance. A comparative assessment of modifier effects on asphalt binder penetration is presented in Figure 2. Both LDHs and ULDHs additives induced substantial reductions in penetration. Relative to OMA, ULMA exhibited penetration decreases of 17.84, 13.52, 14.97, 14.88, and 14.22% at aging durations of 0, 46, 92, 138, and 184 h, respectively. The corresponding reductions for LMA were more pronounced at 19.80, 17.14, 18.92, 17.94, and 17.66%. The penetration ratios followed the hierarchy: ULMA > LMA > OMA. The consistently superior performance of ULMA over LMA indicates that the composite modification system combining hydrotalcite with UV absorbers provides superior anti-aging performance compared to hydrotalcite modification alone.

Penetration and penetration ratio of different types of asphalt: (a) Penetration and (b) penetration ratio.

3.1.3 Ductility

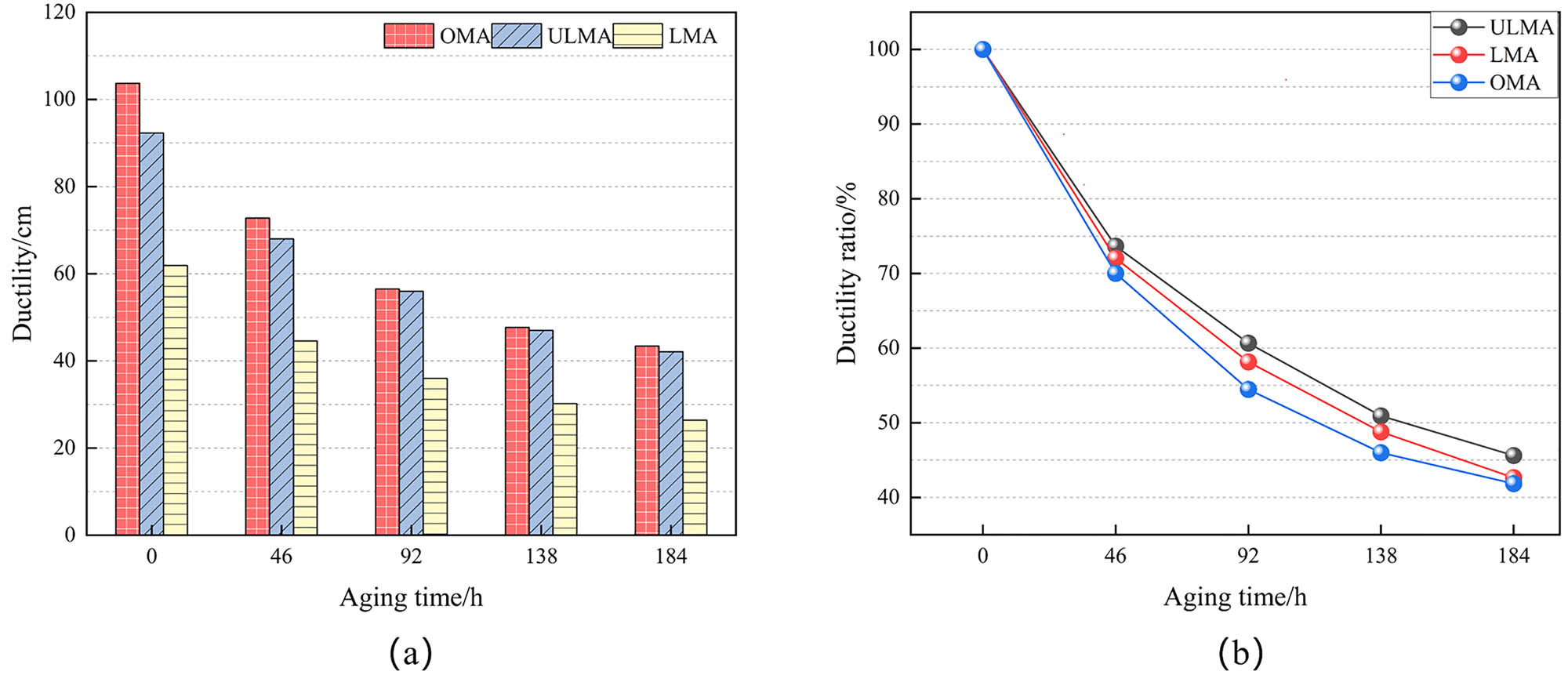

Figure 3 displays the ductility and ductility ratio results for OMA, LMA, and ULMA. Analysis of Figure 3(a) demonstrates that UV aging significantly affects asphalt ductility, with all asphalt types exhibiting marked reductions in ductility upon aging. The modified asphalts consistently showed higher ductility ratios than the base asphalt (OMA), confirming the effectiveness of modifiers in enhancing aging resistance. As illustrated in Figure 3, the incorporation of LDHs and ULDHs led to considerable decreases in ductility. Compared to OMA, ULMA exhibited ductility reductions of 10.99, 6.59, 0.88, 1.47, and 3.00% at aging durations of 0, 46, 92, 138, and 184 h, respectively. In contrast, LMA showed more substantial decreases of 40.31, 38.74, 36.28, 36.69, and 39.17% at corresponding aging intervals. These results indicate that LDHs have a more pronounced negative impact on asphalt ductility compared to ULDHs. The ductility ratios followed the order: ULMA > LMA > OMA. The consistently higher ductility values of ULMA relative to LMA suggest that the addition of UV absorbers effectively mitigates the adverse effects of LDHs on ductility. Furthermore, the synergistic modification effect between these components enhances the overall aging resistance of the composite-modified asphalt.

Ductility and ductility ratio of different types of asphalt: (a) Ductility and (b) ductility ratio.

3.2 Rheological performance

3.2.1 Failure temperature

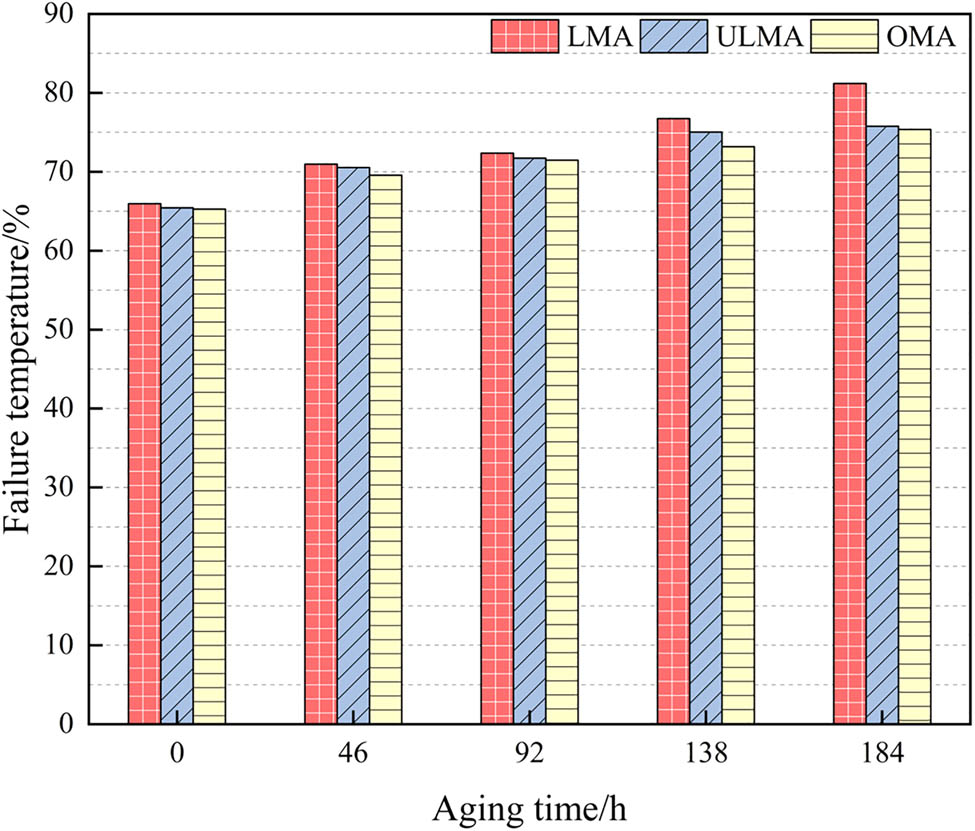

Figure 4 presents the failure temperatures of different asphalt types at various aging intervals. As shown in Figure 4, all asphalt specimens exhibited progressively increasing failure temperatures with extended aging duration. Specifically, after 186 h of aging, OMA, ULMA, and LMA demonstrated failure temperature increases of 15.46, 15.78, and 23.11%, respectively. Throughout all aging stages, the failure temperatures followed the order: LMA > ULMA > OMA, with both modified asphalts showing superior performance to the base asphalt. This confirms that both hydrotalcite and composite modifiers effectively enhance the high-temperature rutting resistance of asphalt. Comparative analysis revealed that LMA consistently achieved higher failure temperatures than ULMA under identical conditions. For instance, after 138 h of aging, OMA showed a failure temperature of 73.17°C. With modifier incorporation, ULMA and LMA reached 75.03 and 76.73°C, representing increases of 2.54 and 4.87%, respectively. While both OMA and ULMA maintained a PG-70 rating, LMA achieved a higher PG of PG-76. These results demonstrate that hydrotalcite modification alone provides more significant improvement in high-temperature rutting resistance compared to the composite modification system.

Failure temperature of different types of asphalt.

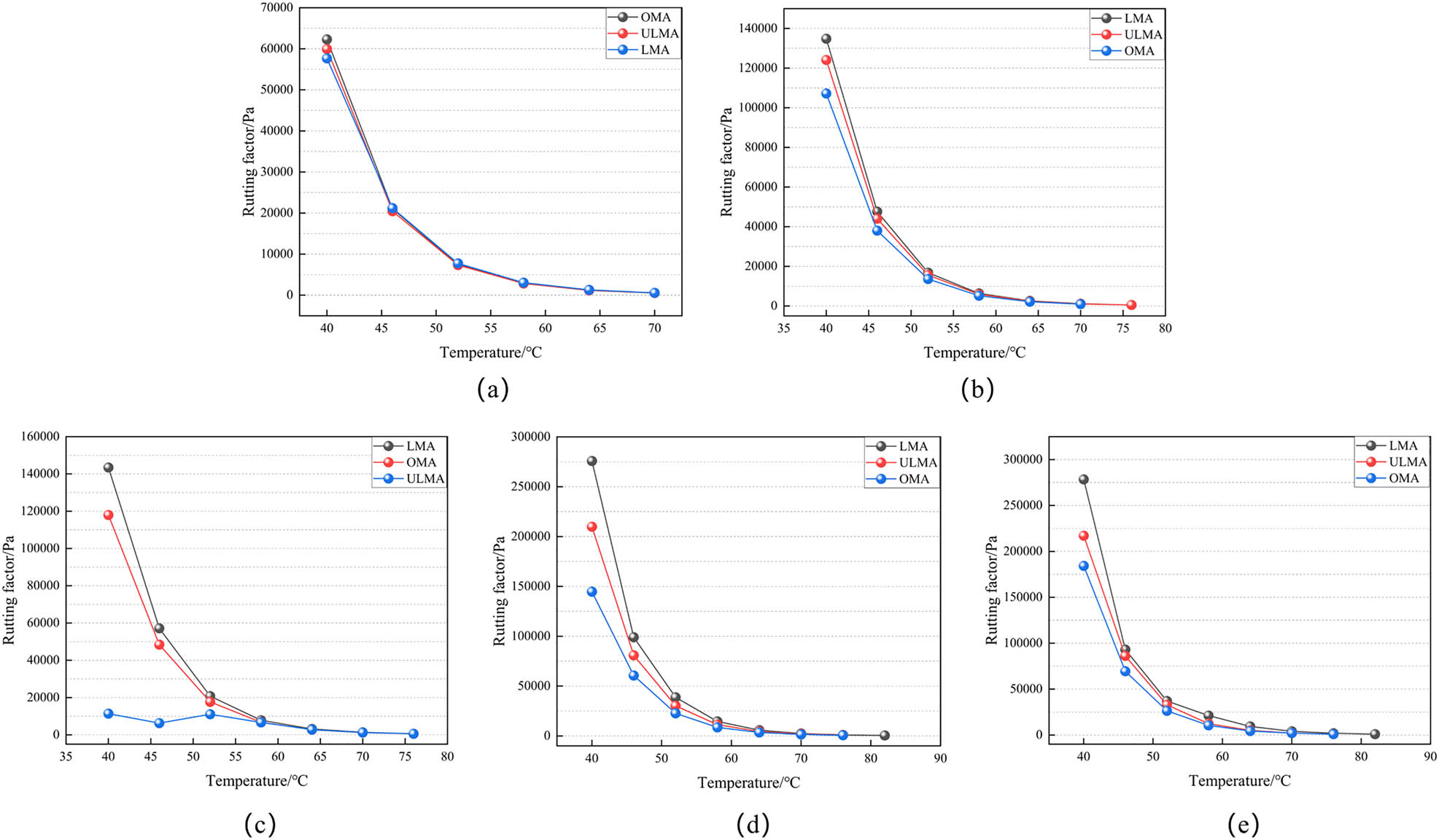

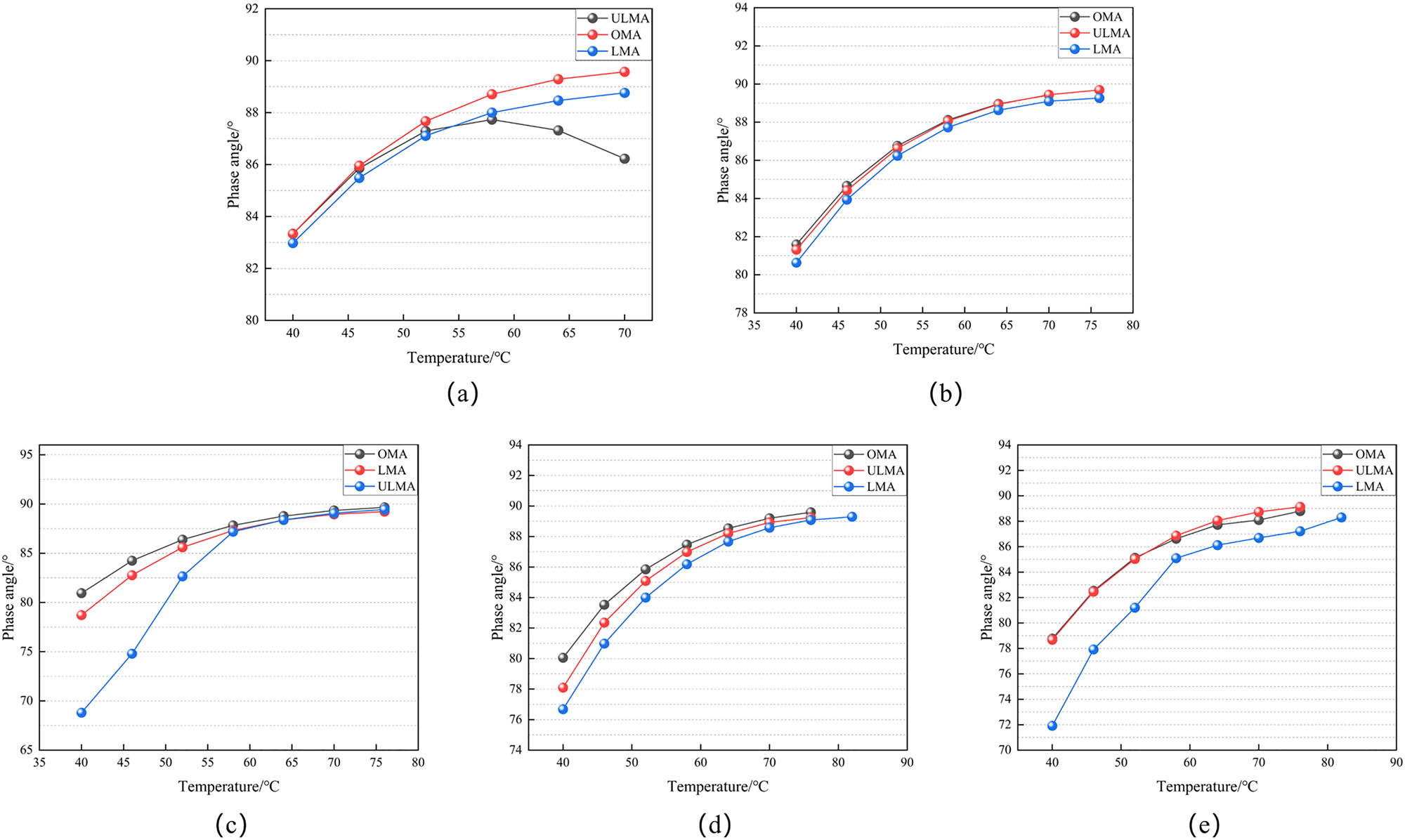

3.2.2 Rutting factor and phase angle

Figures 5 and 6 present the |G*|/sinδ and δ results for different asphalt types after UV aging. As shown in Figure 5, at lower temperatures, aged asphalt exhibits significantly higher rutting factors compared to unaged asphalt, with this difference gradually diminishing as temperature increases. This phenomenon may be attributed to stronger intermolecular interactions in asphalt at lower temperatures, leading to agglomeration of macromolecules such as asphaltenes. With rising temperature, enhanced molecular motion disperses these aggregates, allowing molecular chains to expand and distribute more uniformly within lighter components, thereby reducing elasticity and increasing viscous behavior.

Changes in rutting factors of different types of asphalt at various aging nodes: (a) 0 h, (b) 46 h, (c) 92 h, (d) 138 h, and (e) 184 h.

Phase angle changes of different types of asphalt at various aging nodes: (a) 0 h, (b) 46 h, (c) 92 h, (d) 138 h, and (e) 184 h.

Comparative analysis of rutting factors before and after aging reveals that aged asphalt consistently demonstrates higher values, indicating improved rutting resistance following UV exposure. Furthermore, the rutting factors of different asphalt types follow the order: LMA > ULMA > OMA, demonstrating that LMA provides superior high-temperature rutting resistance compared to ULMA. These results confirm that hydrotalcite modification alone offers greater enhancement of asphalt’s high-temperature performance than composite modification.

Figure 6 presents the phase angle (δ) results of asphalt binders before and after UV aging. The temperature-dependent phase angle behavior reveals that δ increases with rising temperature, indicating enhanced viscous behavior in asphalt. This trend corresponds to an increasing proportion of viscous components and decreasing elastic components, resulting in improved flow properties. Comparative analysis demonstrates that the base asphalt (OMA) consistently exhibits higher phase angles than modified asphalts, reflecting its superior flow characteristics. This observation suggests that the modifiers function as elastic components within the asphalt matrix, thereby enhancing the material’s elastic properties. The phase angles follow the order: OMA > ULMA > LMA, indicating that ULMA possesses better high-temperature rutting resistance than LMA. This result implies that hydrotalcite modification alone more effectively increases the elastic fraction of asphalt, consequently improving its high-temperature performance. These findings are consistent with the previously observed complex modulus trends, further validating the superior performance of hydrotalcite-modified asphalt.

3.3 Functional group composition

3.3.1 FTIR results

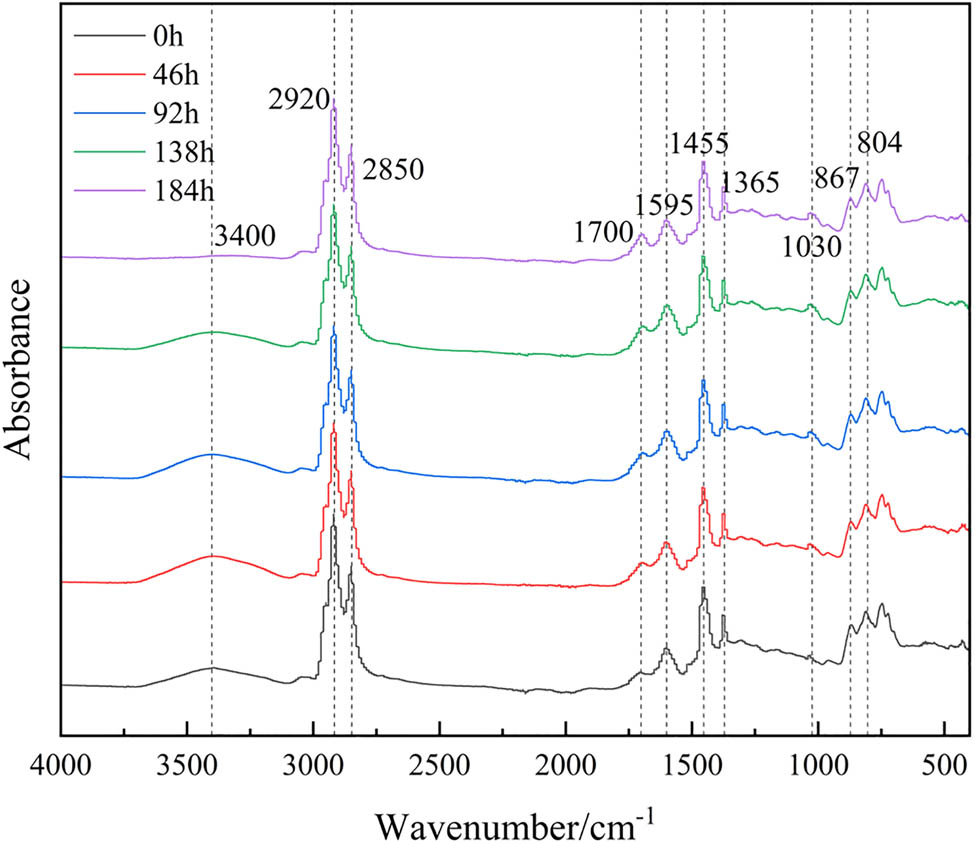

3.3.1.1 Base asphalt

Figure 7 presents the FTIR spectrum of the base asphalt, revealing several characteristic absorption peaks between 4,000 and 400 cm−1. A broad O–H stretching vibration appears at 3,400 cm−1, while peaks at 2,920 and 2,850 cm−1 correspond to methyl –CH3– and methylene –CH2– stretching vibrations, respectively. The spectrum shows carbonyl (C═O) vibrations at 1,700 cm−1, benzene ring breathing vibrations at 1,595 cm−1, and strong absorptions at 1,455/1,365 cm−1 from C–CH3 and –CH2– vibrations. Additional features include sulfoxide (S═O) vibrations at 1,030 cm−1 and aromatic out-of-plane vibrations at 804/867 cm−1, confirming aromatic constituents in the asphalt.

Infrared spectrum of matrix asphalt.

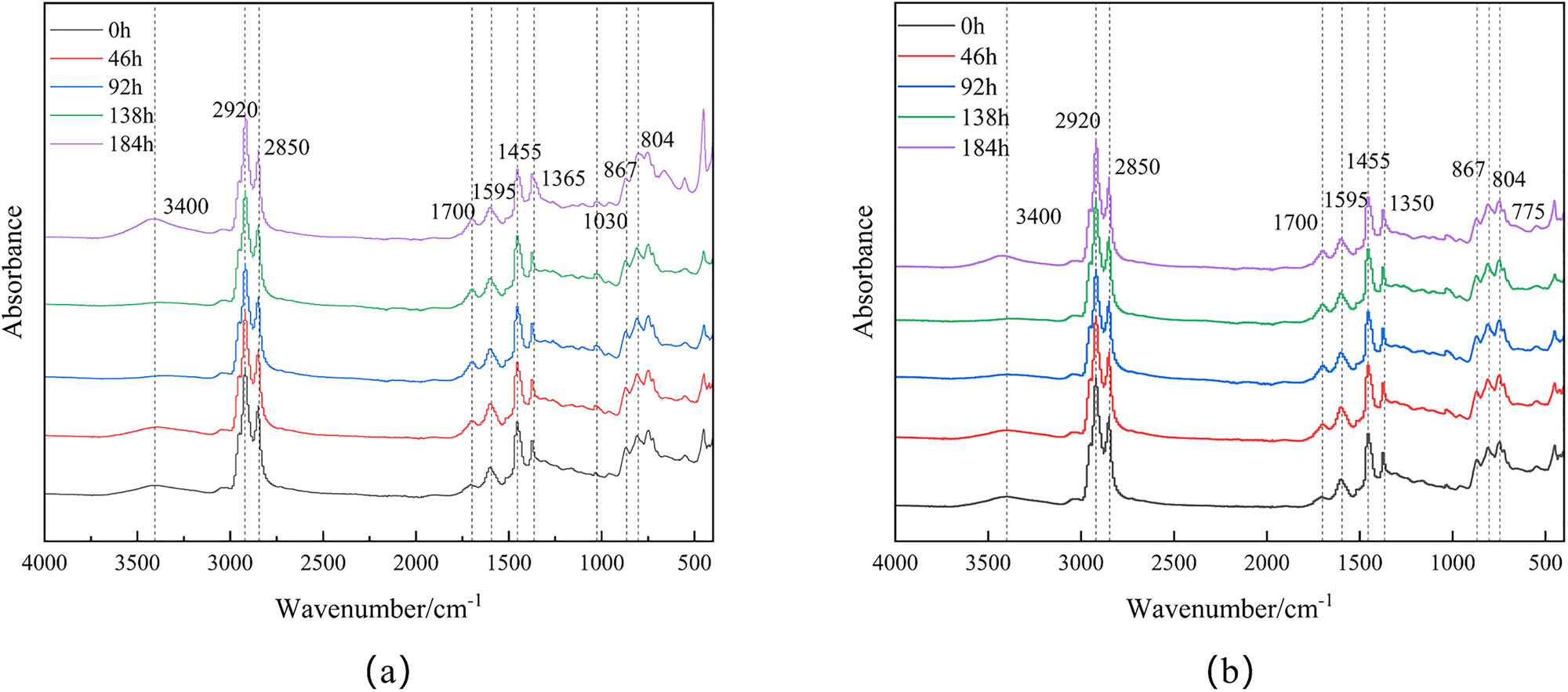

3.3.1.2 Modified asphalt

Figure 8 displays the FTIR results for modified asphalt, showing generally similar spectral features to the base asphalt but with notable modifications. The hydroxyl peak at 3,400 cm−1 weakens, suggesting chemical interaction between hydrotalcite surface hydroxyl groups and asphalt components. New absorption peaks emerge at 1,350 cm−1 CO3 2− and 775 cm−1 NO3 −, indicating successful hydrotalcite incorporation. The complex composition of petroleum asphalt may cause some functional group peaks to overlap or become obscured in the spectrum. These changes demonstrate measurable chemical modifications resulting from the additive incorporation while maintaining the fundamental asphalt spectral characteristics.

Infrared spectrum of modified asphalt: (a) LMA and (b) ULMA.

3.3.2 Functional index

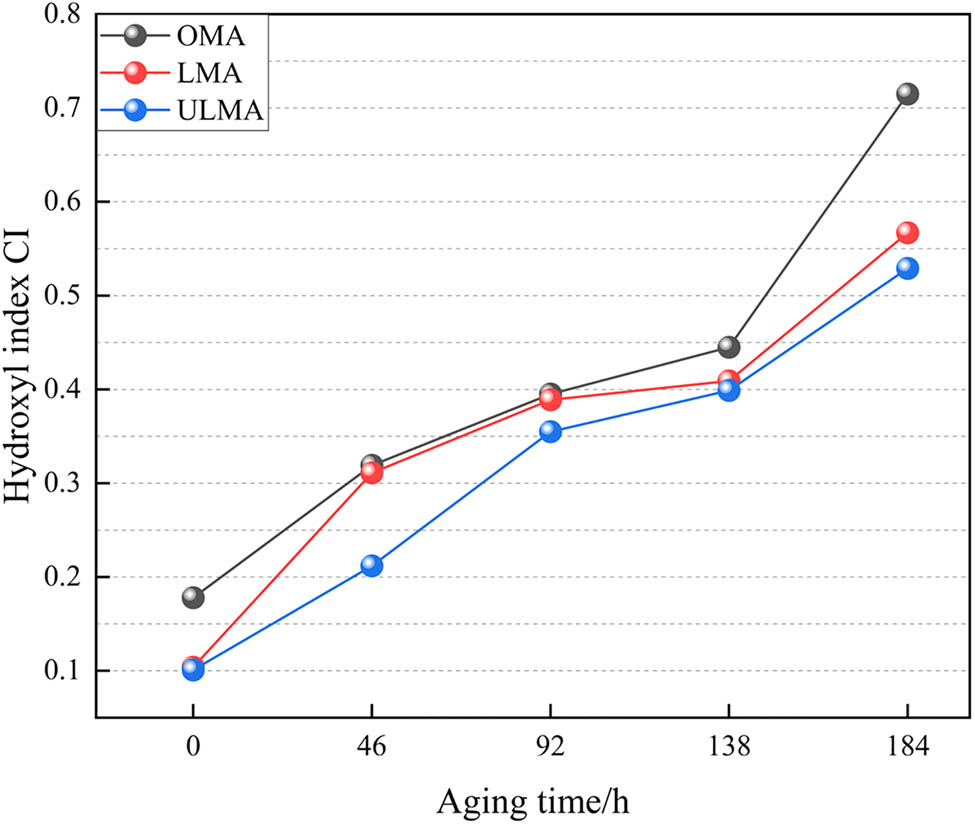

3.3.2.1 Hydroxyl index

Figure 9 illustrates the variation in the CI of different asphalt types with aging time. Analysis reveals that the CI values of all asphalt types progressively increase with advancing aging severity, attributable to oxidative degradation mechanisms. This trend stems from the abundant C═C bonds in asphalt, where hydroxyl group formation accompanies carbon chain (C═C bond) cleavage during oxidation, leading to continuous accumulation of carbonyl groups. The CI growth rate exhibits an initial deceleration with prolonged aging, likely due to decreasing C═C bond concentration reducing reaction kinetics, though a notable acceleration emerges after 138 h of aging. Comparative evaluation shows distinct CI magnitudes among asphalt types at equivalent aging durations, following the order: OMA > LMA > ULMA. This hierarchy demonstrates: (1) the effectiveness of both hydrotalcite and composite modifiers in suppressing aging-related functional group formation, thereby enhancing aging resistance; and (2) the superior performance of the composite-modified asphalt (ULMA) over hydrotalcite-modified asphalt (LMA), as evidenced by its consistently lower CI values. These results confirm that the synergistic interaction between hydrotalcite and UV absorbers in the composite system provides more efficient inhibition of oxidative aging pathways compared to hydrotalcite modification alone.

Change chart of CI index for different types of asphalt.

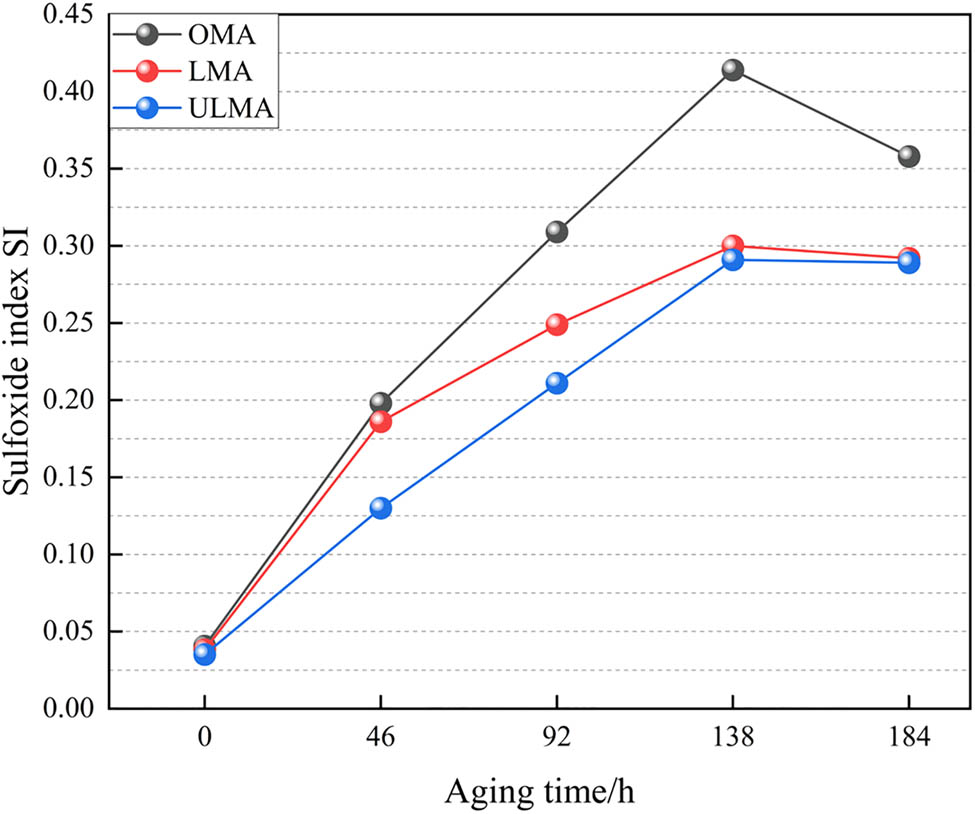

3.3.2.2 Sulfoxide index (SI)

Figure 10 presents the SI variation of different asphalt types with aging time. Analysis reveals a distinct decrease in SI concentration after 138 h of aging, suggesting potential decomposition of S═O bonds exceeding their formation rate through sulfur oxidation during this stage. The observed SI reduction indicates an actual decline in sulfoxide group concentration rather than accumulation. Comparative analysis demonstrates that base asphalt (OMA) exhibits the highest SI variation rate, implying greater susceptibility of its sulfur components to oxidation compared to modified asphalts. The SI values follow a consistent hierarchy across all aging durations: OMA > LMA > ULMA, mirroring the trend observed in the CI data. This parallel behavior strongly confirms that the composite-modified asphalt (ULMA) delivers superior aging resistance compared to hydrotalcite-modified asphalt (LMA), with the synergistic effect between hydrotalcite and UV absorbers proving more effective in inhibiting oxidative aging mechanisms than hydrotalcite modification alone.

SI index variation chart of different types of asphalt.

3.4 Molecular dynamic simulation

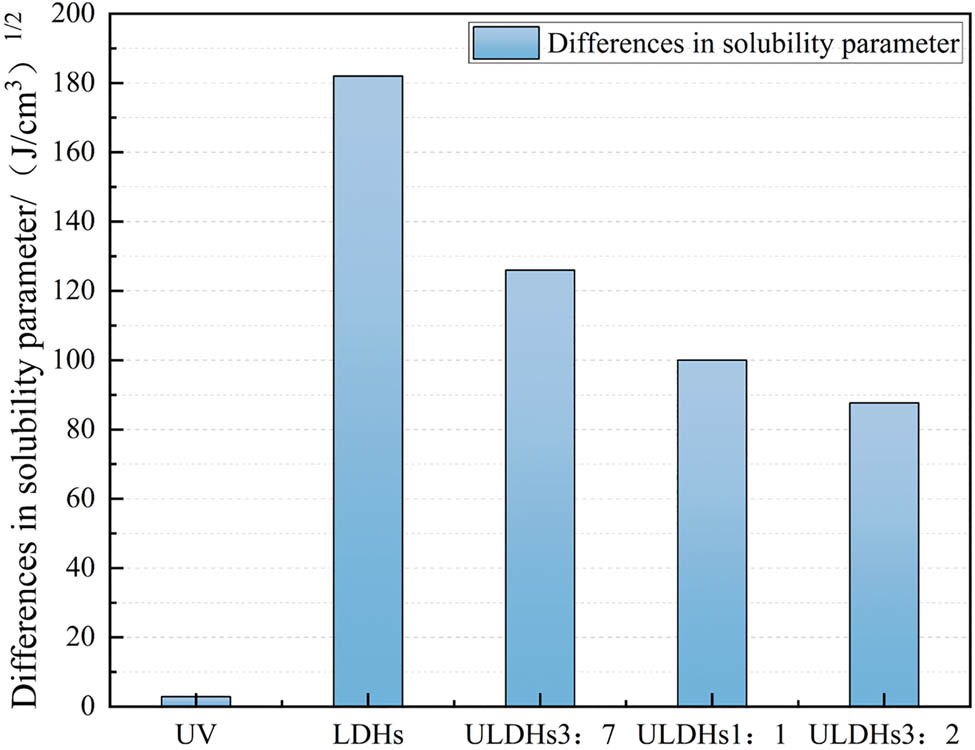

3.4.1 Solubility parameter

The solubility parameters of the UV absorber, hydrotalcite, and base asphalt are presented in Table 3. Analysis of the data reveals that the solubility parameter of the base asphalt remains around 17, which aligns with existing research findings. A comparison of the solubility parameters between the UV absorber and hydrotalcite indicates that the UV absorber exhibits the closest match to the base asphalt. This similarity arises because the molecular structure of the UV absorber resembles that of asphaltenes and resins in the asphalt model – both featuring aromatic rings and aliphatic chains. Consequently, the UV absorber demonstrates good compatibility with asphalt, contributing to enhanced structural stability. In contrast, hydrotalcite displays a significantly different solubility parameter from asphalt, indicating poor compatibility and inferior thermal stability. This discrepancy stems from the high layer charge density and strong hydrophilicity of LDHs. These properties lead to strong interparticle attraction among LDHs dispersed within the asphalt matrix, resulting in phase separation and inhomogeneous dispersion in asphalt/LDH composites.

Solubility parameters of different types of modifiers and matrix asphalt

| Model | Base asphalt | UV absorber | LDHs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility parameter (J·cm−3)(1/2) | 17.55 | 14.64 | 199.54 |

In summary, the above analysis demonstrates that the UV absorber exhibits superior compatibility with base asphalt compared to hydrotalcite. Consequently, it is preliminarily concluded that combining the UV absorber with hydrotalcite can improve the compatibility between hydrotalcite and asphalt. Based on this hypothesis, this study simulated and calculated the solubility parameters of composite modifiers at different blend ratios, as presented in Table 4. Here, the composite modifier (a:b) represents the mass ratio of the UV absorber (a) to hydrotalcite (b). The results indicate that the solubility parameters of the composite modifiers deviate significantly from those of the base asphalt, likely due to the presence of hydrotalcite. However, compared to pure hydrotalcite, the incorporation of the UV absorber substantially reduces the solubility parameter of the composite modifier, confirming that the UV absorber–hydrotalcite combination enhances the compatibility between hydrotalcite and asphalt. Further analysis of different blend ratios reveals that as the proportion of the UV absorber increases, the solubility parameter of the composite modifier decreases markedly, gradually approaching that of asphalt. This trend suggests that the UV absorber content significantly influences the compatibility between the composite modifier and asphalt – higher loading ratios lead to better compatibility.

Solubility parameters of composite modifiers with different ratios

| Model | ULDHs (3:7) | ULDHs (1:1) | ULDHs (3:2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility parameter (J·cm−3)1/2 | 143.58 | 117.57 | 105.2 |

Figure 11 presents the solubility parameter differences between various types of aging-resistant modifiers and the base asphalt. As shown in Figure 11, the order of solubility differences is LDHs > ULDHs > UV. The UV absorber exhibits the smallest solubility difference with asphalt, indicating optimal compatibility and the highest thermal stability. In contrast, LDHs display the largest solubility difference, resulting in poor compatibility and inferior thermal stability. Due to the incorporation of the UV absorber, the solubility difference between the composite modifier and asphalt is reduced compared to that of LDHs alone. Furthermore, as the proportion of the UV absorber increases, the solubility difference gradually decreases, thereby enhancing the thermal stability of the asphalt system.

Differences in solubility parameters between different types of anti-aging modifiers and matrix asphalt.

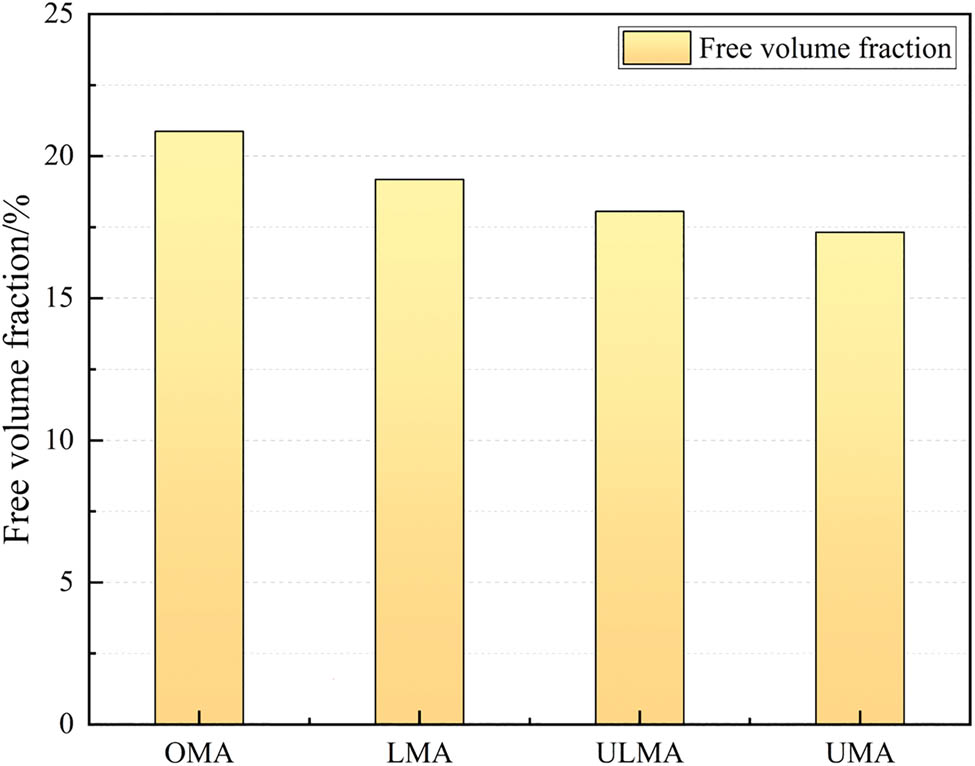

3.4.2 Free volume

The free volume fractions of the four models were calculated separately, and the results are presented in Figure 12. Analysis of Figure 12 reveals that the base asphalt exhibits the highest free volume fraction at 20.87%. Upon the incorporation of modifiers, the free volume fraction of asphalt shows a decreasing trend. This indicates that the addition of modifiers alters the distribution of asphalt components, reducing the internal free volume and restricting molecular mobility within the asphalt, thereby enhancing its internal stability. This phenomenon may be attributed to the aggregation of certain asphalt components around the modifiers, forming localized concentrated regions. As a result, the asphalt density increases, improving stability and making it less susceptible to aging.

Free volume fraction of different types of asphalt.

Table 5 presents the changes in free volume fraction of the models after modifier incorporation. Analysis of Table 5 reveals that the free volume fractions of all asphalt models decreased upon modifier addition. The introduction of LDHs exhibited the least pronounced effect, reducing the free volume fraction by only 1.69%. In contrast, UV absorbers demonstrated the most significant impact, decreasing the free volume fraction by 3.55%. The composite modifier yielded an intermediate reduction of 2.81%. These results indicate that, compared to LDHs alone, the synergistic effect of UV absorber and LDHs in the composite modifier more substantially reduces the free volume fraction of asphalt. This reduction contributes to enhanced structural stability within the asphalt matrix, consequently improving its aging resistance.

Change amplitude of free volume fraction in the model after adding modifier

| Modifier | UV absorber | LDHs | ULDHs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change amplitude of free volume fraction (%) | −3.55 | −1.69 | −2.81 |

4 Conclusions

The main research conclusions of this article are as follows:

The softening point of various asphalt types progressively increases with extended UV aging duration, while penetration and ductility gradually decrease. The incorporation of UV absorbers markedly mitigates the adverse effects of LDHs on asphalt’s physical properties, while their synergistic modification effect endows the modified asphalt with superior anti-aging performance.

After modifier incorporation, ULMA (composite-modified) and LMA (LDH-modified) exhibit elevated failure temperatures of 75.03 and 76.73°C, representing increases of 2.54 and 4.87%, respectively. While both OMA and ULMA maintain a PG grade of PG-70, LMA achieves a one-grade enhancement to PG-76, demonstrating that LDHs alone more effectively improve the high-temperature rutting resistance of asphalt.

The solubility parameter difference between UV absorbers and asphalt is minimal, indicating optimal compatibility and thermal stability. In contrast, LDHs exhibit the largest solubility difference with asphalt, resulting in poor compatibility and inferior thermal stability. The composite modifier, through the inclusion of UV absorbers, reduces this solubility difference compared to LDHs alone.

The composite modifier produces the most substantial improvement in asphalt’s diffusion coefficient (65.13% increase). This confirms that the synergistic interaction between UV absorbers and LDHs more significantly accelerates molecular diffusion rates in asphalt. The enhanced mobility prevents a greater number of asphalt molecules from undergoing degradation during aging, ultimately improving the material’s anti-aging performance.

Future study will focus on the interactive effect between organic and inorganic modifiers on of asphalt pavement materials, which could provide references for coupling applications of organic and inorganic modifiers in pavement engineering.

Acknowledgments

This article describes research activities mainly requested and sponsored by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (grant number 2024A1515012242), Guangdong Provincial Natural Science Foundation-Youth Promotion Project (grant number 2024A1515030113), and Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Project (Young Doctor “Sailing” Project) (grant number 2024A04J1276).

-

Funding information: This article describes research activities mainly requested and supported by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (grant number 2024A1515012242), Guangdong Provincial Natural Science Foundation-Youth Promotion Project (grant number 2024A1515030113), and Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Project (Young Doctor “Sailing” Project) (grant number 2024A04J1276).

-

Author contributions: Yixin Pan: investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing – original draft. Zhaojian Luo: investigation, data curation, writing – original draft. Liangyu Wang: investigation, data curation, formal analysis. Xuegang Yan: investigation, data curation, writing – original draft. Yuanyu Lu: investigation, formal analysis, data curation. Xiaolong Sun: conceptualization, resources, writing – review and editing. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] Sun, X., J. Yuan, Z. Liu, X. Qin, and Y. Yin. Evaluation and characterization on the segregation and dispersion of anti-UV aging modifying agent in asphalt binder. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 289, 2021, id. 123204.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123204Search in Google Scholar

[2] Zhang, H., H. Luo, H. Duan, and J. Cao. Influence of zinc oxide/expanded vermiculite composite on the rheological and anti-aging properties of bitumen. Fuel, Vol. 315, 2022, id. 123165.10.1016/j.fuel.2022.123165Search in Google Scholar

[3] Zhang, C., S. Yang, T. Wang, S. Xu, P. Jin, H. Dong, et al. A novel method to improve the anti-ageing ability of bitumen by organic LDHs/SBS composite: preparation, performance evaluation and mechanism analysis. Fuel, Vol. 383, 2025, id. 133845.10.1016/j.fuel.2024.133845Search in Google Scholar

[4] Sun, G., T. Ma, Y. Jiang, M. Hu, T. Lu, and D. Siwainao. Dual self-repairing enhancement mechanisms of blocked dynamic isocyanate prepolymer on aging degradation and fatigue damages of high-content SBS-modified asphalt. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 472, 2025, id. 140855.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.140855Search in Google Scholar

[5] Xu, Y., Q. Liu, H. Wang, and S. Wu. Synthesis of different antioxidant intercalated layered double hydroxides and their enhancement on aging resistance of SBS modified asphalt mixture. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 455, 2024, id. 139229.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.139229Search in Google Scholar

[6] Xu, S., X. Jia, S. Pan, Z. Ma, L. Fang, C. Zhang, et al. Effect of antioxidant/CA-LDHS on the properties of SBS-modified bitumen. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 36, 2024, id. 04023604.10.1061/JMCEE7.MTENG-16896Search in Google Scholar

[7] Sun, X., X. Qin, Z. Liu, and Y. Yin. Damaging effect of fine grinding treatment on the microstructure of polyurea elastomer modifier used in asphalt binder. Measurement, Vol. 2024, 2024, id. 115984.10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115984Search in Google Scholar

[8] Qiu, Y., B. Zheng, B. Jiang, S. Jiang, and C. Zou. Effect of non-structural components on over-track building vibrations induced by train operations on concrete floor. International Journal of Structural Stability and Dynamics, 2025, id. 2650180.10.1142/S0219455426501804Search in Google Scholar

[9] Sun, X., Z. Ou, Q. Xu, X. Qin, Y. Guo, J. Lin, et al. Feasibility analysis of resource application of waste incineration fly ash in asphalt pavement materials. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, Vol. 30, No. 2, 2023, pp. 5242–5257.10.1007/s11356-022-22485-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Zhang, H., W. Xuan, J. Chen, X. Sun, and Y. Zhu. Improving effect and mechanism on service performance of asphalt binder modified by PW polymer. Reviews on Advanced Materials Science, Vol. 63, 2024, id. 20240058.10.1515/rams-2024-0058Search in Google Scholar

[11] Zhang, M., D. Yuan, and W. Jiang. Effects of TLA on rheological, aging, and chemical performance of SBS modified asphalt. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 438, 2024, id. 137283.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137283Search in Google Scholar

[12] Guo, M., R. Zhang, X. Du, and P. Liu. A state-of-the-art review on the functionality of ultra-thin overlays towards a future low carbon road maintenance. Engineering, Vol. 32, 2024, pp. 82–98.10.1016/j.eng.2023.03.020Search in Google Scholar

[13] Xu, S., G. Tang, S. Pan, Z. Ji, L. Fang, C. Zhang, et al. Application of reactive rejuvenator in aged SBS modified asphalt regeneration: a review. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 421, 2024, id. 135693.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135696Search in Google Scholar

[14] Zhu, C., H. Zhang, Q. Li, Z. Wang, and D. Jin. Influence of different aged RAPs on the long-term performance of emulsified asphalt cold recycled mixture. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 458, 2025, id. 139680.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.139680Search in Google Scholar

[15] Ren, H., Z. Qian, T. Chen, H. Cao, X. Zhang, and L. Qian. Low-temperature flexural tensile performance degradation of asphalt mixture under coupled UV radiation and freeze-thaw cycles. Road Materials and Pavement Design, Vol. 1, 2025, pp. 1–15.10.1080/14680629.2025.2454024Search in Google Scholar

[16] Tong, Y., Y. Liu, X. Han, and Y. Tan. A simulation method for life cycling aging of asphalt binders under temperature cycling effects. Materials, Vol. 18, 2025, id. 1542.10.3390/ma18071542Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[17] Ju, Z., D. Ge, Y. Xue, D. Duan, S. Lv, and S. Cao. Investigation of the influence of the variable-intensity ultraviolet aging on asphalt properties. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 411, 2024, id. 134720.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134720Search in Google Scholar

[18] Li, Q., C. Liang, C. Sun, Y. Luo, J. Li, and H. Zhang. Investigation on targeted composite rejuvenation of aged SBS-modified bitumen for low-cost and efficient recycling. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 498, 2025, id. 145195.10.1016/j.jclepro.2025.145195Search in Google Scholar

[19] Pandhawale, S. S., S. Jain, A. K. Chandrappa, and V. Kari. UV aging assessment of asphalt binder: influence of duration, zinc oxide, and aging condition. International Journal of Pavement Engineering, Vol. 25, 2024, id. 2359537.10.1080/10298436.2024.2359537Search in Google Scholar

[20] Liu, Z., X. Sun, H. Xu, Y. Lu, Z. Su, Y. Ye, et al. Anti-aging performance and action mechanism of asphalt modified by composite modification. Applied Sciences, Vol. 14, 2024, id. 10250.10.3390/app142210250Search in Google Scholar

[21] Sun, X., H. Xu, X. Qin, Y. Zhu, and J. Jin. Cross-scale study on the interaction behaviour of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash-asphalt mortar: a macro–micro approach. International Journal of Pavement Engineering, Vol. 26, 2025, id. 2469114.10.1080/10298436.2025.2469114Search in Google Scholar

[22] Zhang, F., Y. Liu, Z. Cao, Y. Liu, Y. Ren, H. Liang, et al. Enhancement of anti-UV aging performance of asphalt modified by UV-531/pigment violet composite light stabilizers. Processes, Vol. 12, 2024, id. 2758.10.3390/pr12122758Search in Google Scholar

[23] Lin, M., Y. Fan, L. Zhang, P. Li, R. Ye, and Y. Zhang. Fatigue characteristics of recycled asphalt mastic under strong ultraviolet radiation in Gansu, China. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 22, 2025, id. e04340.10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04340Search in Google Scholar

[24] Jiang, Z., J. Si, M. Zhang, J. Wang, X. Shao, M. Xing, et al. UV aging behavior and mechanism of cold-mixed epoxy asphalt. Journal of Vinyl and Additive Technology, Vol. 30, 2024, pp. 301–312.10.1002/vnl.22050Search in Google Scholar

[25] Enfrin, M. and F. Giustozzi. The role of polymer modification in mitigating ‘sunburn’damage on asphalt roads. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 439, 2024, id. 140929.10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.140929Search in Google Scholar

[26] Yang, B., H. Li, Y. Sun, Y. Li, L. Yin, and M. Cheng. Aging gradient and aging acceleration effect on asphalt and asphalt mixture coupling thermal oxidation, ultraviolet radiation and water. Ultraviolet Radiation and Water, 2024.10.2139/ssrn.4933749Search in Google Scholar

[27] Chen, Q., T. Ge, X. Li, X. Li, and C. Wang. Road area pollution cleaning technology for asphalt pavement: literature review and research propositions. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 493, 2025, id. 144975.10.1016/j.jclepro.2025.144975Search in Google Scholar

[28] Chen, Z., Z. Zhang, X. Chen, R. Hou, Z. Ding, F. Liu, et al. Multi-role collaborative framework for structural damage identification considering measurement noise effect. Measurement, Vol. 250, 2025, id. 117106.10.1016/j.measurement.2025.117106Search in Google Scholar

[29] Wang, C., X. Tian, Y. Wang, and G. Li. The aging mechanism of asphalt aromatics based on density functional theory, frontier orbitals, IR, SARA, and GPC. Journal of Molecular Liquids, Vol. 396, 2024, id. 124010.10.1016/j.molliq.2024.124010Search in Google Scholar

[30] Li, Y., G. Jiang, S. Yan, J. Feng, and Z. Fang. Degradation behaviour and anti-UV ageing method of sustainable road marking materials for strong UV light area. International Journal of Pavement Engineering, Vol. 26, 2025, id. 2456737.10.1080/10298436.2025.2456737Search in Google Scholar

[31] Espinosa, L. V., K. Vasconcelos, and L. L. Bernucci. The effect of UV radiation in the rheological properties of a wood-based bio-binder. In The international workshop on the use of biomaterials in pavements, Vol. 58, 2024, pp. 261–266.10.1007/978-3-031-72134-2_28Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods