Abstract

In the pursuit of sustainable and durable building materials, this study delves into the potential application of polypropylene fiber (PPF) as a reinforcement material in lightweight concrete. With increasing emphasis on environmentally responsible construction, enhancing the mechanical performance of lightweight concrete is crucial. Although PPF is not a cementitious material, its integration into concrete mixtures has shown promise in improving properties such as compressive strength, flexural strength, and ductility. A detailed analysis of the chemical and physical characteristics of various PPF types was conducted to assess their influence on concrete behavior. In addition, a comprehensive literature review was undertaken to identify existing gaps and establish a foundation for further investigation. The study also evaluates the effects of PPF inclusion on failure modes, stress–strain behavior, and crack propagation in lightweight concrete. Results indicate that incorporating PPF significantly enhances toughness, crack resistance, and energy absorption capacity, contributing to a more ductile and resilient material. These improvements are particularly relevant for structural applications requiring both reduced weight and enhanced durability. However, the performance gains are closely related to the fiber type, dosage, and distribution, underscoring the need for careful mix design and optimization. By addressing limitations in previous studies and offering a nuanced understanding of PPF’s role in lightweight concrete, this research contributes valuable insights for the development of durable, sustainable building materials. The findings serve as a foundation for future research and practical applications, supporting the broader adoption of fiber-reinforced concrete in environmentally conscious construction.

1 Introduction

During the past two centuries of development, concrete materials have progressed from useful to essential in a wide variety of technical applications due to their unique features, low cost, and ease of preparation [1]. The strength of typical concrete is adequate to meet the ever-increasing demands placed on today’s buildings [2]. Despite its many benefits, including resistance to fire and high temperatures, ordinary concrete is quickly destroyed by tensile stress due to its extremely low tensile strength. Consequently, researchers are interested in concrete made with a wide variety of fibers [3,4].

Sustainable building materials should prioritize improving concrete’s energy efficiency, longevity, and low life-cycle cost. Considering that the production of 1 tonne of Portland cement leads to carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions [5], it is essential to broaden our supply of sustainable binder resource [6]. Geopolymer, an inorganic polymer, could be used instead of cement-based concrete to reduce greenhouse gas emissions [7]. Industrial byproducts, such fly ash [8,9], rice husk ash [10,11], and metakaolin [12,13], are being considered as viable alternatives to cement in the production of products and processes, which can potentially diminish the environmental impact of concrete production. Concurrently, the integration of nanomaterials introduces innovation to enhance concrete properties, such as metakaolin [14], SiC nanoparticles [15], perovskite nanomaterial [16], and nano-silicon carbide [17]. Merging geopolymer, nanomaterials [18,19], and industrial byproducts underscores sustainable practices and innovation in construction materials, aligning with carbon footprint reduction and improved performance goals [19].

Amidst rapid population growth and urbanization, the emergence of a substantial volume of construction trash has been a significant and formidable obstacle, yielding a slew of social and environmental predicaments [20]. Worldwide, scholars and engineers are resolutely engaged in devising effective strategies to curtail construction waste, leading to a compelling emphasis on the practical feasibility of repurposing such waste into secondary building materials. This dual-pronged approach targets the reduction of construction waste storage and the diminished reliance on natural building resources [21].

The increasing disposal of concrete waste and its enduring social and environmental consequences remain pressing concerns in the foreseeable future [22]. To address this issue, researchers worldwide are focusing on recycling and reclamation strategies [23], with particular attention to the substitution of natural sand and stones in concrete by employing recycled fine [24] and coarse aggregate [25]. Creating man-made aggregate from trash has many benefits. For example, by using recycled materials to create lightweight aggregate, we can save nonrenewable natural resources and save transportation costs [26].

Waste management is a serious issue worldwide. The construction industry frequently makes use of waste solids because they can be repurposed into useful components of buildings. Scientists have reverse-engineered certain solid wastes for use in creating artificial aggregates [27]. Green technology, such as the geopolymerization process, has the potential to lower the world’s carbon footprint. According to previous studies [28,29], the amount of CO2 emitted during the production of 1 metric ton of GPC is approximately 164 kg, which is roughly one-sixth of CO2 released during the production of OPC concrete; thus, it helps mitigate global warming. As an alternative to cement, industrial byproducts, such as fly ash, metakaolin, and waste agriculture, in addition to polypropylene fiber (PPF), can be used to supply the aluminosilicate needed for goods and processes [30,31], thereby reducing CO2 emissions [26].

Given its ease of production, low cost, and abundance of raw materials, concrete is one of the most used building materials worldwide. Its plasticity, durability, and versatility are ideal for ordinary construction [32]. By contrast, traditional concrete is problematic due to its high brittleness, low toughness, and low tensile strength. For these reasons, regular concrete is not fit for use in some projects and buildings, such as field prefabricated beams and bridge decks [33]. To achieve these criteria, a concrete composite with lower specific gravity and higher mechanical characteristics is needed [32].

Modern developments in lightweight cement concrete (LCC) have resulted in a material with desirable properties, including enough compressive strength [34], low density [35], good thermal resistance [34], durability, and impermeability [36]. An increasing number of people are starting to take notice of LCC because of its wide range of possible uses in onshore and offshore building projects. Concrete can be made lighter by adding air, bubbles, or lightweight materials or by omitting concrete fines; however, such incorporation greatly reduces its strength [37]. The specific strength of LCCs can be kept high through the incorporation of microlightweight particles into cement [38].

Lightweight concrete is a type of concrete characterized by its reduced density compared to conventional concrete, achieved by using lightweight aggregates such as expanded clay, shale, pumice, perlite, or by incorporating air-entraining agents [34]. The typical density of lightweight concrete ranges from 1,400 to 2,000 kg·m−3, significantly lower than that of normal weight concrete (approximately 2,400 kg·m−3) [35]. This reduced weight offers advantages in structural efficiency, thermal insulation, and seismic performance, making lightweight concrete a desirable choice in a variety of engineering and construction applications [39]. The mechanical properties of lightweight concrete, such as compressive strength, tensile strength, and modulus of elasticity, can vary based on the mix design, type of lightweight aggregate used, and curing conditions. In recent years, the incorporation of fiber reinforcements, such as PPFs, has further enhanced the performance of lightweight concrete by improving its tensile strength, ductility, and resistance to cracking.

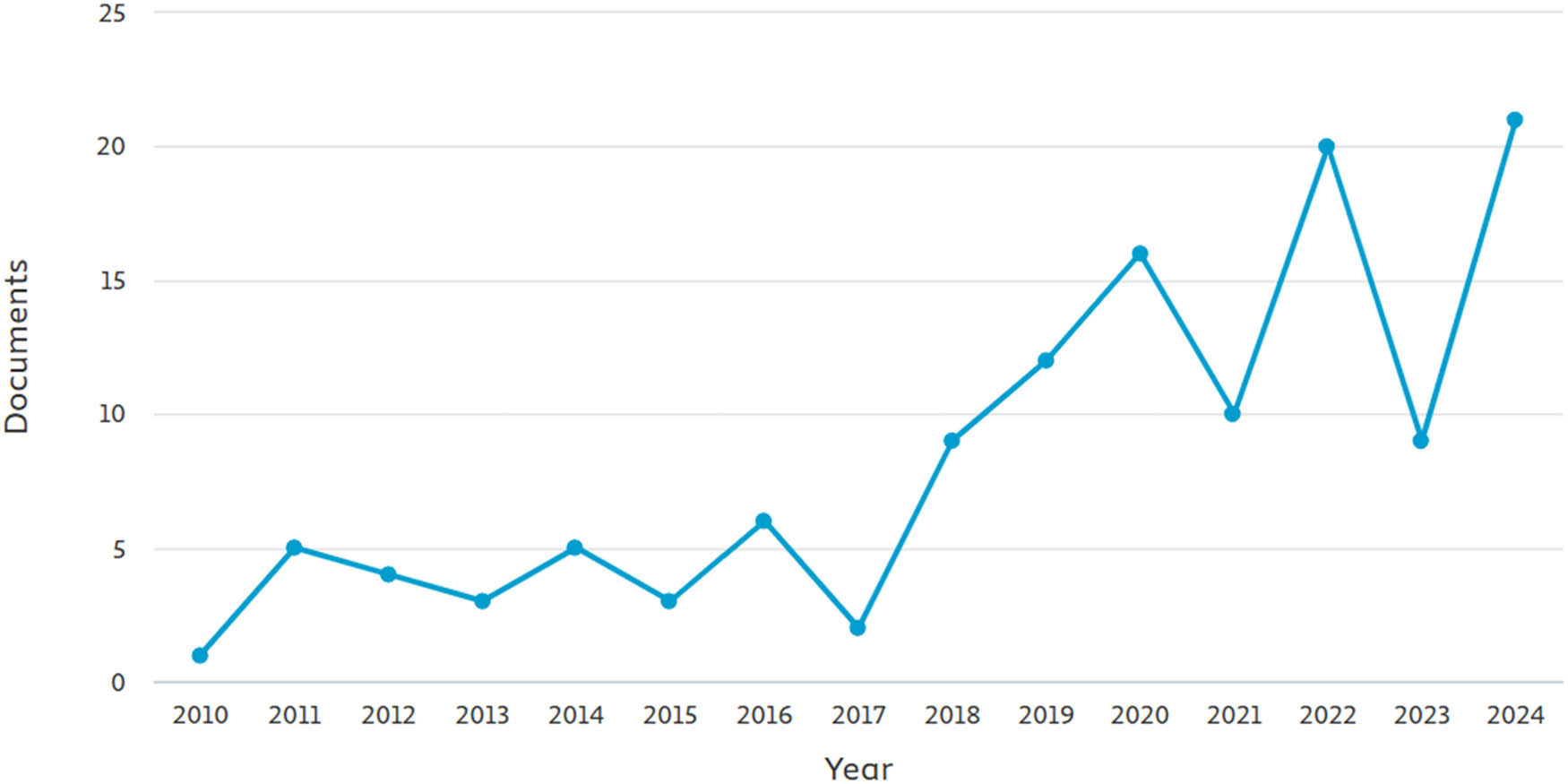

The optimization of raw materials and advances in production technology have led to concrete’s increase in prominence as the primary construction material utilized in engineering construction. Lightweight [40], high-strength [41], environmentally friendly [42], and green sustainable development have become priorities in the construction industry as a whole in response to the increase of industrialization in the building and engineering sector. Given its many advantages [43], such as higher specific strength, lower density, better thermal insulation, improved durability, etc., lightweight aggregate concrete (LWC) is now commonly used in the building industry. However, the poor flexural tensile strength and brittleness of the material have restricted its use [44]. Fiber increases the impact resistance, flexural strength, and postcracking ductility of LWCs [45]. An analysis of publication trends of PPF and fiber-reinforced LWC from 2010 to 2024 reveals a significant increase in research on PPF-reinforced lightweight concrete, with publications rising from 2 in 2010 to an estimated 22 in 2024 (Figure 1).

Number of studies on PPF and fiber-reinforced LWC (according to Scopus database 2010–2024).

Wall panels [46], masonry blocks [47], precast concrete units [48], lightweight floor fills [48], and so on are examples of LWC’s widespread application in the construction industry. These applications make use of LWC’s many benefits, such as low self-weight, high strength-to-weight ratio, cost effectiveness, and long service life. Porous lightweight aggregates are responsible for much of the concrete’s strength and low density, making them crucial to the success of LWC [49]. LWC shares the porous property of ceramsites, but it also has several shortcomings, such as brittleness texture and inferior workability [50,51,52], which severely limit its widespread usage in civil engineering.

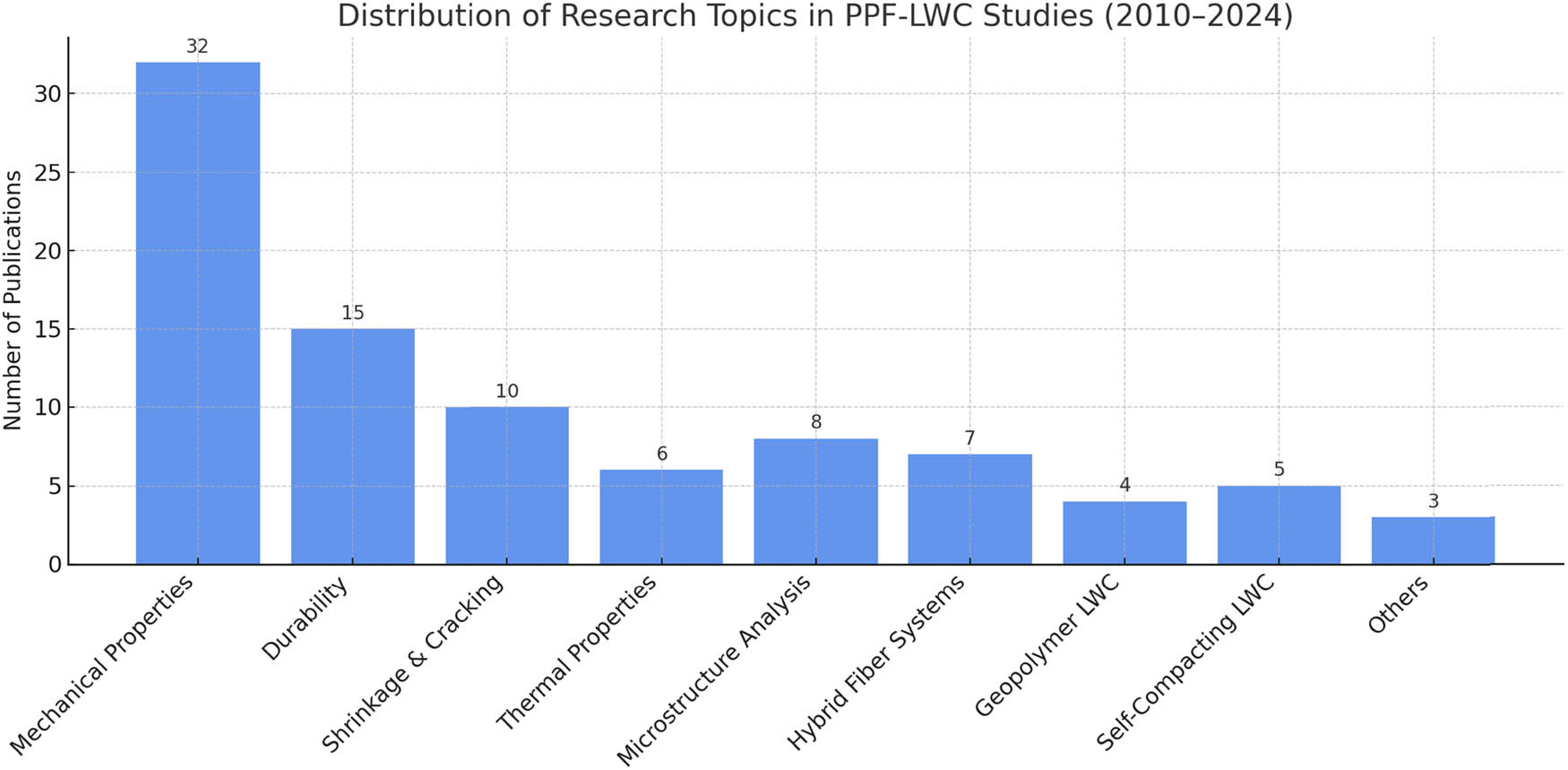

The majority of PPF-based LWC studies focus on mechanical properties (40%), followed by durability (25%) and thermal performance (15%) (Figure 2). Numerous studies have explored the brittleness of LWA’s texture. Research has shown that adding the right amount of HPP to LWC enhances its fracture resistance, crack resistance, and toughness qualities. Previous studies have demonstrated that LWC is more brittle than regular concrete of the same mix proportions, and that this brittleness increases as LWC strength is enhanced [52]. To enhance its strength and reduce its susceptibility to damage, LWC has traditionally been reinforced with various types of fibers, such as steel, polyvinyl alcohol, and PPF, either alone or in combination. Numerous studies have explored the mechanical features of fiber-reinforced LWC, with the general consensus being that the addition of fiber expands its compressive, flexural strength, flexural toughness, and impact resistance [53,54].

Distribution of research topics in PPF–LWC studies (according to Scopus database 2010–2024).

Given the numerous internal voids, LWAs can absorb considerably more water than regular aggregates. Given that LWAs are porous, they readily absorb the free water, drastically reducing the workability of fresh LWC if the LWAs are not sufficiently prewetted. Prewetting LWAs has been shown to vastly increase the workability and pumpability of fresh LWC in the engineering field. Prewetted LWAs, which might act as a water reservoir in the concrete, were also used to forestall cracking caused by autogenous shrinkage. At the same time, the density, freeze–thaw resistance, and thermal insulation of hardened LWC would be affected by the water-saturated state of LWA [55,56].

A new environmentally preferable binder called geopolymer has been launched as a substitute for Portland cement. Industrial waste that has a high content of silica and alumina, for instance, fly ash [47,57,58], bottom ash [59,60], slag [61], and rice husk ash [62,63], can be used to create the geopolymer material. In addition, geopolymer concrete applications [64] have made extensive use of PPF to boost flexural strength and durability. However, high PPF content may reduce workability and increase porosity [65]. According to Chindaprasirt et al. [66], the binding strength between the matrix and the fiber is improved by adding fiber at the optimal content with uniform dispersion [67].

Particularly for high-strength concrete, which is brittle, fiber can be added to the matrix to increase the material’s ductility [68]. LWC has been reported to be more fragile than regular concrete [51]. Many different fibers have been studied in published research. Lightweight concrete benefited greatly from the addition of steel fiber in terms of flexural strength and splitting strength. However, adding steel fiber to lightweight concrete makes it more substantial [69]. As a result, research on low-density fiber for use in lightweight concrete is warranted. Lightweight concrete reinforced with PPF has been shown to boost indirect tensile strength without considerably affecting compressive strength or modulus of elasticity, as demonstrated in the study of Liu et al. [69].

Fiber added to concrete increases its residual strength and bearing capacity when debonding, making the material less likely to collapse. Given their ability to lower corrosion and wear on mining equipment, PPF is gaining popularity [70]. Thus, contrary to what was found in a previous study, PPF was chosen in this study [71].

An overview of earlier research on fiber integration into lightweight concrete is presented in Table 1. Regular concrete has a number of disadvantages, such as an increased specific gravity, an increased level of brittleness, and a low degree of toughness. Due to these shortcomings, ordinary concrete is inappropriate for use in constructions, notably bridge decks and field-fabricated beams. Lightweight concrete is subject to cracking and flexural strains more than ordinary concrete because LWC fractures as a result of aggregate rupture. Newer LCC is quite low in density and exhibits sufficient compressive strength. A high specific strength can be achieved by adding microlightweight particles to cement. Lightweight concrete allows for the construction of smaller and lighter-weight structural members, which in turn reduces the dead load and increases the seismic resilience of structures. Several researchers are interested on how LWC might be used on ships and other floating structures. For the most part, lightweight concrete is no different from other cementitious materials in being a brittle substance. Reinforced concrete buildings have a shorter lifespan than expected because of steel reinforcement corrosion, which necessitates frequent and expensive maintenance. Lightweight concrete is an important component of green structures. PPF-reinforced lightweight concrete is gaining much interest because of its additional advantages [72]. By adding PPF to lightweight concrete, its load-carrying capacity is increased, making it closer in strength to normal weight concrete. The inclusion of fiber also helps control crack propagation and reduce crack width. Additionally, this type of concrete decreases deformation capacity, which results in more cost-effective solutions by reducing the weight of the concrete.

An overview of earlier research on fiber integration into lightweight concrete

| Ref. | Country | Field of use |

|---|---|---|

| Ghanim et al. [73] | KSA | PPE and glass fiber in LWC |

| Mohamed et al. [74] | KSA | Fiber-reinforced LWC |

| Aisheh et al. [75] | Jordan | Polypropylene and SF in geopolymer concrete |

| Zhu et al. [56] | China | LWC made with high-performance PPF |

| Ortiz et al. [71] | Chile | A lightweight approach utilizing fiber |

| Zeng and Tang [76] | China | Fibers made of basalt and polyacrylonitrile |

| Li et al. [45] | China | Reinforced LWC with high-performance PPF |

| Madandoust et al. [77] | Iran | LWC enhanced with PPF and steel fibers |

| Abdul-Rahman et al. [78] | Iraq | PPF-reinforced reactive powder concrete beams |

| Salehi et al. [79] | Iran | Lightweight concrete strengthened with PPF. |

| Srinivas et al. [80] | India | PPF lightweight concrete |

| Balgourinejad et al. [81] | Iran | PPF used in lightweight concrete, as well as incorporating metakaolin |

| Liu et al. [69] | China | Lightweight concrete created macro-polyfelin polymer fibers |

| Yew et al. [72] | Malaysia | Various types of PPFs on high-strength lightweight concrete |

| Jun Li et al. [82] | China | Fiber made of high-performance polypropylene |

| Altalabani et al. [83] | Iraq | Self-compacting LWC + PPF |

| Xie et al. [37] | China | LWC strengthened by PPFs |

| Tanyildizi [84] | Turkey | PPF concrete |

| Guler [85] | Turkey | Impact of polyamide fibers on structural lightweight concrete properties |

| Wang et al. [86] | UK | Geopolymer lightweight concrete properties, including PPFs. |

| Mehrab and Esfahani [87] | Iran | Role of PPF in the strength of LWC |

| Ghasemzadeh Mousavinejad and Shemshad Sara [88] | Iran | Hybrid fiber on the mechanical properties of LWC |

| Najaf et al. [89] | Iran | Impact of PF on the impact resistance and ductility of lightweight concrete |

| Ismael and Mohammed [90] | Iraq | Fiber-reinforced LWC |

| Loh et al. [91] | Malaysia | Synthetic PPF used on LWC |

| Srinivas et al. [80] | India | LWC made by using coconut shell and expanded polystyrene beads as coarse aggregate, and incorporating PPF |

| Zhou and Chen [92] | China | Using hybrid fiber on LWC |

| Xie et al. [37] | China | Using PPFs on lightweight concrete |

| Altalabani et al. [83] | Iraq | Using PPF on self-compacting LWC |

| Badogiannis et al. [93] | Greece | Steel and PPF concrete |

| Al Qubro and Saggaff [94] | Indonesia | Lightweight concrete made with PPF |

| Rasheed and Prakash [95] | India | Hybrid synthetic fiber reinforcement used in LWC under uniaxial tension |

| Yang et al. [96] | China | Use of fiber in LWC |

| Zhang et al. [32] | China | Effects of fibers on LWC |

| Cunha et al. [48] | Brazil | Concrete reinforced with fiber |

| Sun et al. [97] | Australia | Engineered cementitious composites reinforced with lightweight fiber |

| Shaiksha Vali and Bala Murugan [98] | India | Impact of artificial fiber aggregate on lightweight concrete |

| Karamloo et al. [99] | Iran | Effects of different quantities of polyolefin macrofiber on self-compacting LWC |

| Amin et al. [100] | Egypt | Lightweight fiber concrete used in high-temperature environments |

| Mastali et al. [46] | Finland | Slag foam concrete + fiber alkali activation |

| Ismael and Mohammed [90] | Iraq | Performance evaluation of lightweight concrete slabs reinforced with fiber |

| Hossain et al. [101] | Canada | Lightweight-SCC beams reinforced with fiber |

| Shafigh et al. [102] | Malaysia | Thermomechanical effectiveness of fiber-reinforced structural-LWC |

| Deifalla [103] | Egypt | Analysis of LWC beams + fiber |

| Manharawy et al. [104] | Egypt | Deep beams made of LWC and reinforced with SF |

| Christidis et al. [105] | Greece | Lightweight concrete with end-hooked steel fibers |

| Liu et al. [106] | China | Flexural cracking in LWC beams reinforced with steel fiber |

| Li et al. [107] | China | Lightweight concrete using fibers, self-compacting, and LWC |

| Xiong et al. [108] | China | Improvement of steel fiber LWC |

| Li et al. [109] | China | SCC-LWC reinforced with steel fiber |

| Salehi et al. [79] | Iran | Impact of microbiological stress on the properties of PPF LWC |

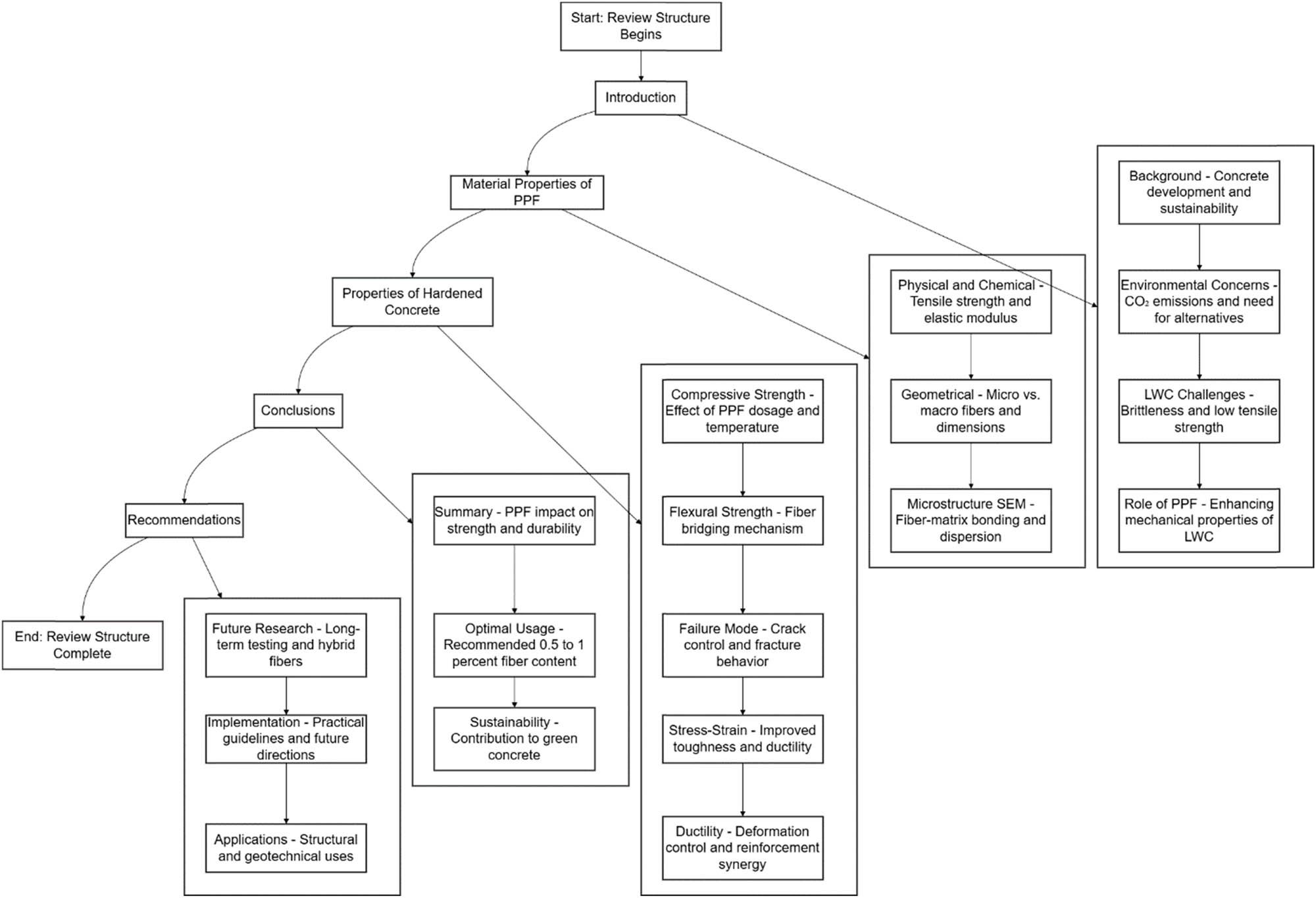

The main goal of this research is to fill in current knowledge gaps by thoroughly examining the use of PPF in LWC as a substitute for cement. By analyzing several PPF choices in terms of their chemical structure and physical features, this study aims to further the development of sustainable LWC. Additionally, the study seeks to assess the effects of PPF on the mechanical characteristics of LWC, concentrating on the characteristics of hardness, such as compressive and flexural strengths. Figure 3 presents the research flow chart of review logic and arrangement of different sections.

Research flow chart of this study.

This research endeavor also aims to explore the interplay between PPF and the durability of lightweight concrete. It delves into an array of pertinent properties, encompassing the failure mode of steel fiber–LWC, stress–strain behavior, and ductility. By amalgamating the study of PPF with the broader context of lightweight concrete performance, a more comprehensive understanding of the material’s behavior and potential advantages can be attained.

In essence, this study builds upon prior research limitations by offering a holistic examination of PPF’s effects on lightweight concrete. It not only enhances the existing body of knowledge by bridging these gaps but also provides nuanced insights into PPF’s behavior within the realm of lightweight concrete. This research does not just conclude with its findings but it paves the way for future inquiries by outlining areas of potential exploration. By shedding light on the properties and behavior of PPF in sustainable lightweight concrete, this study is poised to make a significant contribution to the field, driving further advancements and insights in this evolving domain.

2 Material properties of PPF

The current work offers a thorough analysis of all aspects that were addressed in earlier research on the incorporation of PPF into LWC’s physical and chemical characteristics. In order to contrast the characteristics and pinpoint the most crucial PPF elements, the article presents the properties in tables and figures. Additionally, research into the physical and chemical characteristics of materials is important because it helps us understand the significance of the material, how to use it, and where it can be used. A detailed assessment of the most significant and most recent findings on the chemical and physical properties of PPF is provided in the current work.

2.1 Physical and chemical properties

PPF is effective in keeping cracks to a minimum, as shown in Figure 4, to strengthen the concrete’s ability to resist heat loss. The concrete’s fibers also distribute the tension stresses throughout the material.

![Figure 4

PPF used in an investigation [111].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_004.jpg)

PPF used in an investigation [111].

Table 2 displays the PPF’s physicochemical characteristics [110], and Table 3 presents the geometrical properties of PPF [111]. The physicochemical attributes and geometrical properties of PPF play pivotal roles in improving concrete to be green concrete by utilizing PPF. The findings not only have direct implications for the development of durable and energy-efficient structures but also contribute to the broader discourse on sustainable building materials.

Physical properties of PPF [110]

| Physical properties with units | Values |

|---|---|

| Electric insulation | Excellent |

| Resistance to mildew, moth | Excellent |

| Elongation (%) tensile strength (kgf/den) | 40–100, 3.5–5.5 |

| Abrasion resistance | Good |

| Moisture absorption (%) | 0–0.05 |

| Softening point (C) | 140 |

| Relative density | 0.91 |

| Thermal conductivity | 6.0 (with air as 1.0) |

| Melting point (C) | 165 |

| Chemical resistance | Generally excellent |

Geometrical properties of PP fibers [111]

| Fiber type | Diameter (µm) | Specific density (g·cm−3) | Tensile strength (MPa) | Length (mm) | Aspect ratio | Elastic modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | 40 | 0.91 | 450 | 12 | 300 | 5 |

For high-strength concrete, PPF was used as a reinforcing material [112]. These fibers are perfect for this application due to their high tensile strength, enhanced elongation, and low elastic modulus. Table 4 lists the physical attributes of the fiber in further detail.

Physical properties of PPF [112]

| Specification | Description |

|---|---|

| Length | 12 mm |

| Tensile strength | 600–700 MPa |

| Elastic modulus | 3,000–3,500 MPa |

| Density | 0.91 g·cm−3 |

Eidan et al. [113] developed PPFs with fibrillated shapes, as presented in Figure 5. Moreover, the characteristics of the fiber are presented in Table 5.

![Figure 5

Shape of PPFs [113].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_005.jpg)

Shape of PPFs [113].

Physical characteristics of PPF [113]

| Length, l (mm) | Diameter, d (mm) | Aspect ratio, l/d | Tensile strength (MPa) | Melting temperature (°C) | Specific gravity (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 0.078 | 77 | 300–400 | 162 | 0.91 |

| 12 | 0.078 | 154 | 300–400 | 162 | 0.91 |

The term “straight or distorted fragments of extruded, oriented, and cut polymer material” refers to a particular kind of polymer fiber.” PPF is of two different types: microfiber and macrofiber [113], as presented in Figure 6. Their length is the most distinguishing feature but they also serve distinct purposes in the poured material. Fibers increase LWC’s flexural tensile strength, impact resistance, and postcracking ductility [113].

In this way, steel reinforcement can be made faster, reducing the initial outlay costs. Typically, they range in size from 30 to 50 mm. Microfibers are less than 30 mm in length, thus they cannot support weight [114,115].

Instead of using a mesh to prevent cracks, micro-PPF can be used. Either a single filament or a network of fibrils characterizes them. Melt spinning yields monofilaments, which are then used to create PPF, or one can use a sheet of polypropylene film to create fibrillated fiber [116]. According to calculations, micro-PPF has an elastic modulus of around 3.8–7.0 GPa and a tensile strength in the range of 300–450 MPa. At 400–760 MPa and 3,512.0 GPa, macro-PPF has a stronger tensile strength and elastic modulus [114].

Fiber hybridization, or incorporating fibers of different materials and/or lengths into the concrete to make HFRC, is described. It is a reliable method to regulate cracks of varying widths and depths over a range of cure times and loading conditions [117,118]. That is, when tiny cracks emerge in the concrete, short fibers can be used to patch them up. Given that they are greater in amount in the mixture, microfibers are more efficient than macrofibers. Thus, the concrete’s early tensile phase is characterized by an increase in strength. When the microscopic fissures join together and macrocracks form, the longer fibers become dynamic and work to slow down the crack expansion, thus increasing the ductility of the concrete and allowing them to withstand a greater load despite the ongoing deformations. For example, the efficacy of combining microfibers and macrofibers was confirmed by showing that after combining the toughness, compressive, tensile, and flexural strength of a material made from polypropylene microfibers and macrofibers increased, whereas drying shrank the material less [119]. A polyethylene/PPF blend improved the postcracking behavior of concrete, as shown in the study of Jongvivatsakul et al. [120].

To improve the mechanical properties of LWC, including its compressive and tensile strengths, without considerably increasing the related heat conductivity, Wang et al. [86] used PPF. Table 6 displays the mechanical properties of polyester fiber (PF), revealing that its tensile strength is pointedly greater than that of normal lightweight concrete. As a result, PF is a great option for enhancing the durability and strength of lightweight concrete.

Parameters of PPF [86]

| Density (g·cm−3) | Diameter (mm) | Modulus of elasticity (MPa) | Elongation at break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.91 | 0.017 | 4987 | 19 |

Badogiannis et al. [93] used a synthetic (polypropylene) macrofiber and three steel fibers of varying total lengths (30, 36, and 60 mm) in the experiment. Steel fibers of 36 and 60 mm length were found to have the standard double-hooked end shape, but steel fibers of 30 mm length were found to have an opposite-hooked end shape. As shown in Figure 7, the fiber and pumice (8–16 mm) penetrate the concrete. Table 7 summarizes the geometrical and mechanical parameters of all fibers.

![Figure 7

Materials used in the concrete mixtures examined [93].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_007.jpg)

Materials used in the concrete mixtures examined [93].

Geometrical and mechanical characteristics of fibers [93]

| Material | Steel 1 | Steel 2 | Steel 3 | Polypropylene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape | Opposite-hook ended | Double-hook ended | Double-hook ended | Straight |

| Length, l (mm) | 30 | 36 | 60 | 52 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 1,100 | 1,100 | 1,100 | 613 |

| Modulus of elasticity (MPa) | 200,000 | 200,000 | 200,000 | 5,400 |

| Diameter, d (mm) | 0.55 | 0.63 | 0.92 | 0.46 |

| Aspect ratio, I/d | 55 | 57 | 65 | 113 |

In addition, Hussain et al. [121] reported that PPFs, steel fibers, and glass fibers, shown in Figure 8, provide a comparative perspective of fiber reinforcements. Table 8 details various characteristics of the fibers.

![Figure 8

(a) Steel fibers, (b) glass fibers, and (c) PPF [121].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_008.jpg)

(a) Steel fibers, (b) glass fibers, and (c) PPF [121].

Characteristics of the employed fiber reinforcements [121]

| Property | SF | GF | PPF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length (mm) | 35 | 618 | 12 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 1,200 | 1,200 | 500 |

| Modulus of elasticity (GPa) | 200 | 1,500 | 5 |

| Diameter of filament (mm) | 0.9 | 0.015 | 0.03 |

| Aspect ratio of filament | 39 | 400 | 400 |

| Density (kg·m−3) | 7,750 | 2,600 | 900 |

SF: steel fiber; GF: glass fiber; PPF: polypropylene fiber.

To sum up, the three kinds of fibers that are most frequently utilized in LWC are PPF, steel fibers, and glass fibers. The geometrical and physical characteristics of these fibers are compared in Tables 2, 7, and 8. PPF is resistant to mildew and moths and provides great insulation from electricity. Glass fibers have a larger dimension ratio and a smaller density compared to steel and PPF fibers, while steel fibers have a greater tensile strength and elastic modulus compared to PPF fibers. The mechanical characteristics of various types of LWCs, such as those with and without PPF, are compared in Tables 3–6. They demonstrate that the inclusion of PPF can dramatically enhance the tensile and compressive strengths of LWC without significantly raising the associated heat conductivity. Although to a lesser extent than PPF fibers, steel and glass fibers can also enhance the mechanical qualities of lightweight concrete.

2.2 Microstructure properties

Jeyanthi and Revathi [110] stated that a comparison of the SEM images of PPF in Figure 9 reveals that the fibers are not sticky and have a shining surface, both of which indicate the presence of fibers within the concrete.

![Figure 9

SEM image of PPF: (a) 200 lm, (b) 100 lm, and (c) 50 lm [110].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_009.jpg)

SEM image of PPF: (a) 200 lm, (b) 100 lm, and (c) 50 lm [110].

Additionally, Givi et al. [122] stated that the great adhesive strength of fiber to the composite binder is evidenced by the fact that when breaking a fiber-reinforced concrete sample, cement paste fragments closely fitting microfiber fiber are plainly evident at a crack (Figure 10). Therefore, under all conditions, the composite binder (containing PPF) concrete has superior qualities over the Portland cement concrete.

![Figure 10

An example of the microstructure of the fiber’s interfacial transition zone in modified cement [122].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_010.jpg)

An example of the microstructure of the fiber’s interfacial transition zone in modified cement [122].

According to Ahmed et al. [112], given the high tensile strength, high elongation, and low modulus of elasticity of PPFs, they were utilized as reinforcing materials in high-strength concrete. Moreover, Yoosuk et al. [67] stated that the SEM images of the PPM samples shown in Figure 11 exhibited interfacial transition zones between fiber and matrices, which were produced by PPF [37]. Mixing became more challenging when the fiber content was higher than optimal. Consequently, the fiber began to ball up, resulting in the matrix developing large holes. In addition, the voids inside the matrix increased with the foam content (Fc). Thus, the fiber and geopolymer paste had less adhesion.

![Figure 11

SEM images of PPF reinforcement. Fc = 0%, and PPF content: (a) 0%, (b) 1.5%, (c) 2.5%, and (d) 3% [67].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_011.jpg)

SEM images of PPF reinforcement. Fc = 0%, and PPF content: (a) 0%, (b) 1.5%, (c) 2.5%, and (d) 3% [67].

According to Bentegri et al. [123], given their high tensile strength, fibrillated twist PPFs of 19 and 54 mm are designed to be utilized in reinforcing and precast concrete (689 MPa). However, PPFs that are 30 mm in diameter are less tensile and have a wave-like appearance (486 MPa). Additionally, in contrast to 19 and 54 mm fibers, this type of fiber is more flexible due to its high elastic modulus (6.9 and 5.75 GPa, respectively). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses reveal distinct differences in the fiber form (Figures 12 and 13).

![Figure 12

SEM images of the fibrillated twist PPF [123].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_012.jpg)

SEM images of the fibrillated twist PPF [123].

![Figure 13

SEM images of the wave PPF [123].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_013.jpg)

SEM images of the wave PPF [123].

Figure 14 displays the microscopic morphologies of PPF and cementitious materials, as reported by Chen et al. [124]. The fibers retain their morphology despite the attachment of a small quantity of cementitious elements to their surfaces. This result suggests that the fiber and cementitious components do not appear to react chemically. Alkali-activated composites demonstrated superior interfacial binding strength with various fiber types, as demonstrated by Bhutta et al. [125].

![Figure 14

SEM images of the PPFs [124].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_014.jpg)

SEM images of the PPFs [124].

Hydrophilic fiber, such as basalt fiber (BF), and hydrophobic fiber, such as PF, are described in the study of Jiang et al. [126]. The bonding performance between BF and the shotcrete matrix is considerably superior to that between PF and the shotcrete matrix owing to the alteration in physical and mechanical properties of BF and PF. Therefore, as shown in Figure 15, the BF has a shorter pull-out length than the PF. Consequently, the ductility, toughness, and rigidity of LWC shotcrete can be improved by a two-fiber material and can prevent the improvement of various cracks in the course of the lightweight aggregate fiber shotcrete (LAFS) impact test. Smaller fibers tend to prevent cracks from occurring, whereas larger fibers prevent cracks from spreading and penetrating at a macroscopic scale [127]. As a result, PF is more flexible and has less stiffness than BF. As an added advantage, PF has a substantially longer draw-out length than BF. After peak stress, ductile deformation in concrete is enhanced further by PF.

![Figure 15

Reflection of BF and PPF in the LAFS matrix: (a) BF and (b) PPF (PF) [126].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_015.jpg)

Reflection of BF and PPF in the LAFS matrix: (a) BF and (b) PPF (PF) [126].

SEM images for ultralightweight high-strength concrete (ULHSC) reinforced with PP fibers are shown in Figure 16. Large gaps are observed among the PP fibers and the cement matrix, suggesting that the PP fibers are only tenuously bound to the matrix [128]. Loose bonding and poor mechanical properties can be traced back to the hydrophobic nature of synthetic PP fibers. Matrix components of ULHSC-PP include Ca, Si, and O, with a lower Ca/Si ratio in ULHSC-PP compared to ULHSC-0. Only a slight increase in static mechanical characteristics was observed, and numerous PP fibers ruptured and broke due to their low tensile strength. The dynamic mechanical capabilities of the ULHSC reinforced with PP fibers were high, showing that the bonding strength between the fiber and matrix is not the only determinant of the dynamic qualities [128].

![Figure 16

SEM images of (a) and (b) ULHSC-0.5 PP- and (c) and (d) ULHSC-1.0 PP-reinforced ULHSCs [128].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_016.jpg)

SEM images of (a) and (b) ULHSC-0.5 PP- and (c) and (d) ULHSC-1.0 PP-reinforced ULHSCs [128].

3 Properties of hardened concrete

The physical and chemical characteristics of the raw materials and binder, the quantity of raw materials and binder utilized, the kind and quantity of coarse aggregate, the quality and quantity of fine aggregates, the proportion of aggregates to binder, the rate of mixing, the proportional of alkaline solution to binder, the curing process, and the testing criteria all have an impact on the concrete durability [129–131].

The present research evaluates the impact of adding or removing PPF in LWC and gives a thorough assessment of the most significant results pertaining to the hardness qualities.

3.1 Compressive strength

Badogiannis et al. [93] explored how the addition of PPF affected the mechanical properties (i.e., compressive strength) of lightweight concrete. A total of nine mixes (six containing steel fiber, two containing PPF, and one serving as a reference without fiber) were tested as part of the experimental inquiry. The data collected during the experiments revealed that the totaling of either type of fiber remarkably increased the compressive strength compared with plain concrete between 16 and 76%. Strong dependence on the term Vf*(l/d) was found for the magnitude of the compressive strength for steel and PPF. Compressive strength was assessed and found to be stronger in all mixes than in the plain concrete by as much as 110%. The term Vf*(l/d) was found to be dependent on compressive strength. Instead, postcrack behavior was substantially linked with the fiber type [93].

El Ouni et al. [132] mentioned that natural aggregate concrete (NC) and recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) saw different effects when a single PPF was added to the mix (RC). Compressive strength in NC and RC is reduced by 4–6% when single synthetic fiber (i.e., PPF) are used because PPF has a lower density than the plain concrete matrix. The difficulty in dispersing microfiber, which leads to buildup of fiber filaments, is another reason [133] for the detrimental effect of PPF on compressive strength. As a result, the concrete’s total porosity improves. Compressive strength was increased when hybrid SF and PPF were used. In high-strength (54 MPa) applications, RC with hybrid fiber can perform up to 94%, as well as plain NC. The compressive strength of RC is increased by 17.2 and 19.6%, respectively, while using 0.75% SF/0.25% PPF and 0.85% SF/0.15% PPF instead of plain RC. PPF reduced the compressive strength when applied alone, but adding SF would have a synergistic effect. Thus, the combined effect of polypropylene and SFs is more beneficial than the sum of the effects induced by individual fiber. By utilizing fiber of varying lengths and diameters, the fracture bridging limit of concrete can be increased, resulting in synergistic effects. When polypropylene and SF are combined, a more corrosion-resistant RC can be produced than when using only SF. In addition, compared with single-SF RC, hybrid fiber RC is lighter and less expensive. PPF can provide an effective hybrid fiber RC because it has a smaller carbon footprint and is less expensive than SF per unit volume [134].

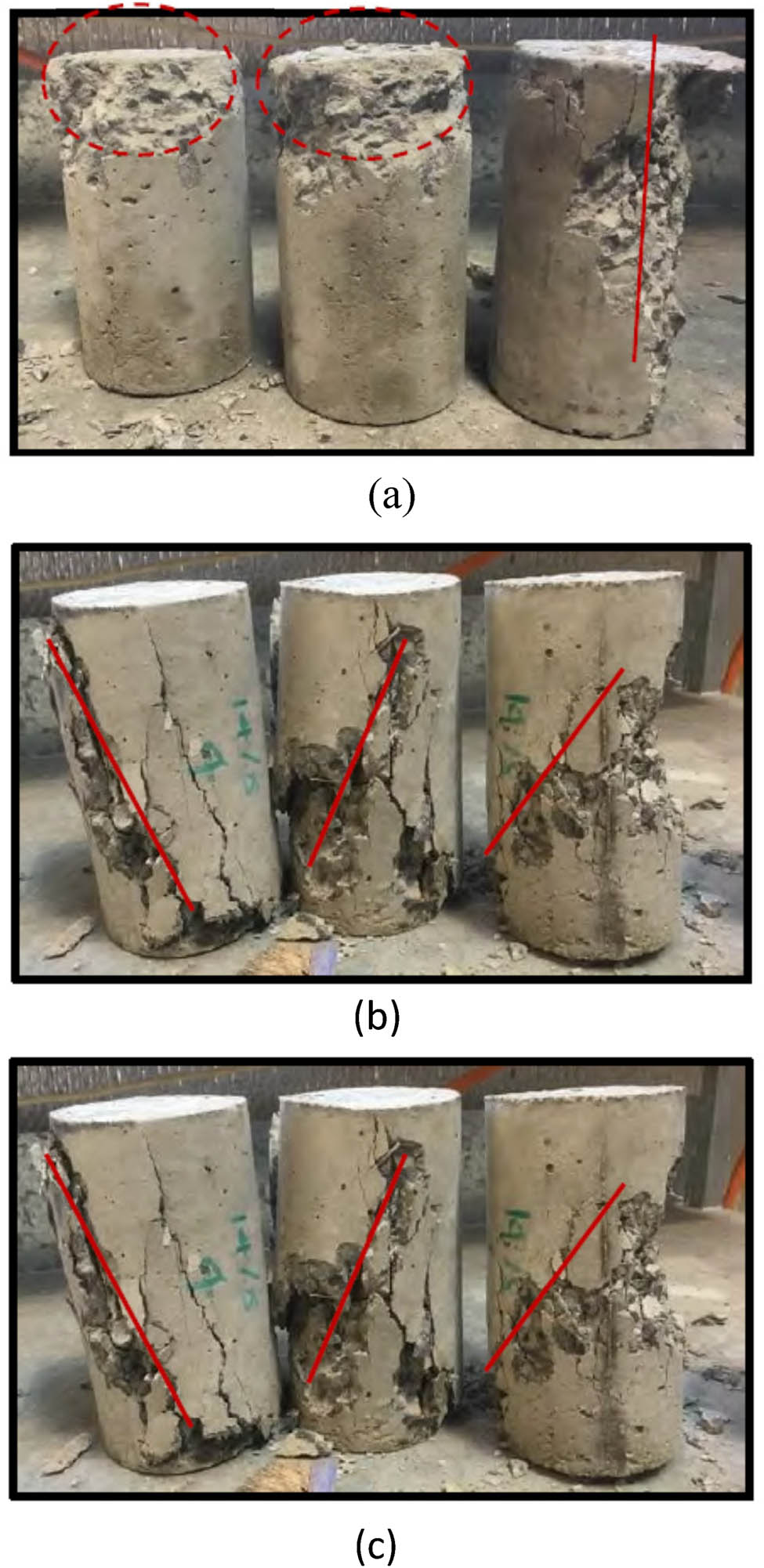

Figure 17 depicts the compression failure of several fiber-containing and fiber-free concrete compositions. PPF-reinforced concrete is more robust than regular concrete, even if it has a low compressive strength because the fiber fills in the gaps caused by the macrocracks, preventing the concrete from breaking apart too easily once the maximum stress has been applied. The single SF-reinforced concrete and the hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete samples maintained a high compressive strength when the maximum load was applied [132].

![Figure 17

Patterns of compression failure in concrete with (a) no fiber (b) one SF, (c) a single PPF, and (d) an SF-PPF hybrid [132].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_017.jpg)

Patterns of compression failure in concrete with (a) no fiber (b) one SF, (c) a single PPF, and (d) an SF-PPF hybrid [132].

PF is a popular choice for reinforcing the strength of lightweight concrete [86] because it offers high-performance abrasion, corrosion, and fire resistance without considerably increasing the thermal conductivity of the concrete. While studies have shown that the addition of PF can enhance the compressive and tensile strengths of lightweight concrete, its effectiveness in increasing compressive strength is found to be less than that of its tensile strength. Therefore, PF can be an excellent option for enhancing the durability and strength of LWC, particularly when tensile strength is a priority. Furthermore, the selection of an appropriate fiber type and configuration for reinforcing lightweight concrete should be the result of the specific performance requirements of the concrete and the conditions in which it will be used.

Compressive strength of fiber with lengths of 3, 6, 9, 12, and 19 mm was reported to be raised by 57, 46, 57, 57, 71, and 6%, respectively, by Wang et al. [86] (Figure 18). The bridging action of the fiber at the crack face shows that its insertion can increase the compressive strength. An anisotropic sample was produced because disseminating the longer PPF uniformly was difficult. The improvement is less pronounced when the fiber length is more than 12 mm.

![Figure 18

Effects of fiber length on the compressive strength [86].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_018.jpg)

Effects of fiber length on the compressive strength [86].

According to Jeyanthi and Revathi [110], compressive strength is measured to determine the overall strength of composite concrete. Casted samples (0, 15, and 30% cenosphere with 0.5% PPF) were cured for 28 days before being put through their paces. The following is a summary of the findings based on the mean values of the strengths: The test may be conducted at day 28 because the minimum strength criteria will have been met by day 7. Levels of maximal strength might be from 0 to 30% (without any admixture) (18.503 and 17.96 MPa – 0 and 15% – on day 7, 25.09 and 23.17 MPa – 0 and 30% – on day 28).

Amran et al. [135] further reported that after 28 days, the composition’s compressive strength had reached 88.5 MPa, which was higher than the control nonreinforced composition (76%) and the reinforced composition (74%). This result proves that the fiber reduces the compressive strength, with the produced polymineral modifier providing majority of the effect. According to Ahmed et al. [112], several scientists have shown that adjusting the proportion of coarse recycled gravel to PPF considerably affects the concrete strength. However, Ahmed et al. [112] demonstrated the effect of PP fiber in concrete with silica fume and coarse recycled material (readily available due to the numerous demolished structures in the Mosul City research zone) on the basis of criteria, such as compressive strength. To achieve this goal, coarse RA concrete (at 0, 50, and 100% volume) is combined with varying percentages of PP fiber (at 0, 0.15, 0.3, 0.45, 0.6, 0.7, and 0.9% volume).

PPF played an important role by enhancing the test findings; its height fineness and length variation in the staple made a bridge action to prevent further construction of microfractures. Compressive strength was maximized at 0.6% PP fiber, with increases of 24.8 and 24.4% for 50 and 100% RA replacement.

According to Meena and Ramana [136], fiber boosted the compressive strength of the concrete. Compressive strength was enhanced by over 17% in comparison with regular concrete after 28 days due to an increase in the fiber content of 0.0–0.5%. The effectiveness of the PF and the concrete mix in stopping cracks from forming is one possible explanation for the concrete’s enhanced compressive strength. Nonlinear regression analysis is used to convert PPF content into an expression of compressive strength. Meena and Ramana [136] noted that up to a PPF concentration of 0.5%, the concrete’s compressive strength increased. Compared with regular concrete, the compressive strength of mixtures containing 0.5% PPF increased by 17% (Figure 19).

![Figure 19

Experimental compressive strength at various PPF contents [136].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_019.jpg)

Experimental compressive strength at various PPF contents [136].

Salehi et al. [79] reported that adding PPF to the control specimens had no appreciable effect on the size of their compressive strength. In contrast to the first group, the percentage of compressive strength increased when bacteria with 0.5% fiber were present. The 1% fiber group had a higher level of bacterial activity. The number of pores in the concrete increased with the fiber fraction.

For temperature effects, concrete with various PPF contents exhibited various compressive strengths both at room temperature and at higher temperatures [137]. After 28 days, the fiber dosage up to 0.5% polypropylene content increased the compressive strength at room temperature, achieving a peak increase of over 17% at 0.5% PPF, before starting to decline. At 200°C, concrete reinforced with PPF at doses of 0.20, 0.35, and 0.50% had compressive strengths that were, respectively, 2.87, 3.51, and 4.43% higher than those of concrete reinforced with PPF at ambient temperature. The compressive strength of concrete containing 0.75 and 1.00% PPF dropped by 3.8 and 4.61%, respectively, as compared to PPF concrete at 27°C [138]. All PPF mixes lost compressive strength at 400°C. In comparison to room temperature, the compressive strengths of PPF concrete mixtures with 0.20, 0.35, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.00% fiber dosage were 12.47, 13.50, 12.35, 15.51, and 17.38% lower, respectively [132,139].

To conclude, Wang et al. [86] showed that the maximal compressive strength of composite concrete can range from 0 to 30% (without any admixture), with mean values of 18.503 and 17.96 MPa for 0 and 15% fiber length, respectively, on day 7, and 25.09 and 23.17 MPa for 0 and 30% fiber length, respectively, on day 28. Wang et al. [86] also indicated that the compressive strength increases with increasing fiber length up to a certain point, beyond which the improvement is less pronounced. Fibers up to 12 mm enhanced strength significantly (up to 71%), but strength gains dropped for 19 mm fibers (only 6%). This can be attributed to dispersion challenges and agglomeration of longer fibers, leading to anisotropic behavior and poor bonding with the cement matrix. Therefore, the optimal fiber length for compressive strength improvement appears to lie between 6 and 12 mm, depending on the mix’s workability and compaction efficiency.

While Meena and Ramana [136] showed that the compressive strength of composite concrete increased with increasing mix content up to a certain point, beyond which the improvement was less pronounced. The optimal mix of content may depend on the specific application and desired strength requirements. It was also indicated that the compressive strength of mixtures containing 0.5% PPF increased by 17% compared with regular concrete. Similar patterns were observed in Surendranath and Ramana [138], where excessive fiber content (>0.6%) led to increased porosity and decreased strength, especially at elevated temperatures.

The hybrid use of steel and polypropylene fibers (SF + PPF) introduces a synergistic effect. According to El Ouni et al. [132], this combination improved compressive strength by enhancing both crack-bridging and toughness. For example, mixes with 0.75% SF + 0.25% PPF outperformed plain RAC by ∼17.2%, and the effect was attributed to better stress distribution and complementary mechanical performance of the fibers. While PPF alone may reduce compressive strength due to its lower modulus and dispersion issues, pairing it with SF can mitigate these drawbacks and yield a net improvement.

Table 9 provides a summary of previous studies on the compressive strength of PPF lightweight concrete. The table includes information on the field of use, mix proportion, PPF content, and compressive strength in MPa. By comparing the data in this table, we can see that the compressive strength of PPF lightweight concrete can vary widely depending on the specific application and mix proportion. For example, Hussein et al. [26] reported compressive strengths of 70 and 87 MPa for alkali-activated mortar with 0.5% PPF and 0.5% PPF + 1% NS, respectively. Qin et al. [3] reported compressive strengths ranging from 34.10 to 35.83 MPa for PPF fabric-reinforced concrete with different fiber contents and mix proportions. Yu et al. [140] reported compressive strengths of 28 and 90 MPa for PPF lightweight concrete used in different fields of application. These variations in compressive strength may be due to differences in the mix proportion, fiber content, curing time, and other factors. Overall, Table 9 highlights the importance of carefully selecting the mix proportion and fiber content to achieve the desired compressive strength for a given application.

Compressive strengths of PPF lightweight concrete according to previous studies

| Ref. | Field of use | Mix proportion | PPF | Compressive-strength (MPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 28 | 90 | ||||

| Hussein et al. [26] | Chemical resistance of alkali-activated mortar | — | 0.5% PPF | — | 70 | 87 |

| 0.5% PPF + 1% NS (nano silica) | — | 64 | 78 | |||

| Qin et al. [3] | PPF fabric-reinforced concrete | 0.75: 1: 3.62: 2.67 | 0.6 | — | 34.17 | 35.23 |

| 0.9 | — | 35.48 | 35.83 | |||

| 1.2 | — | 34.10 | 35.30 | |||

| 1.5 | — | 34.29 | 34.70 | |||

| Yu et al. [140] | Ultra-lightweight fiber-reinforced concrete | — | 0 | — | 11 | — |

| 0.2 long PF | — | 12.5 | — | |||

| 0.3 long PF | — | 13.5 | — | |||

| 0.05 long + 0.15 short PF | — | 12 | — | |||

| 0.6 long PF | — | 14.5 | — | |||

| 1.2 long PF | — | 13.75 | — | |||

| Vakili et al. [141] | Lightweight concrete beams reinforced with GFRP bars | 0.39: 1: 0.53: 0.80 | 0.8 PF | — | 36 | — |

| Orouji and Najaf [142] | PPFs on flexural and compressive strength | 0.30: 1: 2.78: 0 | 0 | 55.4 | 71.8 | 83.5 |

| 0.5 | 56.6 | 73.2 | 85.3 | |||

| 1 | 57.1 | 74.4 | 86.1 | |||

| 1.5 | 57.8 | 75.1 | 87.4 | |||

| Salehi et al. [79] | Lightweight concrete reinforced with PPF | 0.43: 1: 0.99: 1.19 | 0 | — | 28 | — |

| 0.5 | — | 33.5 | — | |||

| 1 | — | 29.5 | — | |||

| Meena and Ramana [137] | PPF reinforced concrete | — | 0 | — | 32.93 | — |

| 0.2 | — | 35.53 | — | |||

| 0.35 | — | 38.17 | — | |||

| 0.5 | — | 38.53 | — | |||

| 0.75 | — | 32.63 | — | |||

| 1 | — | 31.7 | — | |||

| Srinivas et al. [80] | Lightweight concrete with PPF | 0.45: 1: 1.41: 2.16 | 0.5 | 4.43 | 8.66 | |

| 1 | 5.9 | 9.93 | ||||

| 1.5 | 4.28 | 4.75 | ||||

| Ahmed et al. [112] | High-strength PPF concrete | — | 0 | — | 66.3 | — |

| 0.15 | — | 71.2 | — | |||

| 0.30 | — | 78.3 | — | |||

| 0.60 | — | 80.1 | — | |||

| 0.90 | — | 60.9 | — | |||

| Kakooei et al. [143] | PPFs on the properties of hardened lightweight self-compacting concrete | 0.32: 1: 0.80: 0.45 | 1.10 | 19 | 28 | — |

| 1.08 | 16.75 | 25 | — | |||

| 1.06 | 16 | 25.75 | — | |||

Overall, the inclusion of PPF in lightweight concrete demonstrates a variable yet generally positive impact on the compressive strength, with most studies identifying an optimal fiber content in the range of 0.5–1.0% (Table 9). Improvements up to 76% have been reported, particularly when PPF is used in hybrid systems or with optimized mix designs. The most significant gains occur around 0.5% PPF, where adequate fiber dispersion and bridging action at crack interfaces contribute to enhanced strength and toughness. However, discrepancies arise among studies due to differences in fiber dispersion, mix composition, and aggregate types. For instance, some studies report reductions in strength when PPF is used alone, citing issues such as fiber agglomeration, increased porosity, or poor compatibility with recycled aggregates. Others highlight the synergistic effect of combining PPF with steel fibers, resulting in improved mechanical performance and cost-effectiveness. Moreover, fiber length and aspect ratio (l/d) influence performance; overly long fibers may entangle, leading to anisotropy and reduced workability, while shorter fibers may inadequately bridge cracks. Environmental conditions (e.g., elevated temperatures) and additives (e.g., silica fume) also affect outcomes, further contributing to variability. Despite these inconsistencies, the weight of evidence suggests that carefully controlled PPF dosages between 0.5 and 1%, combined with appropriate mix designs and placement techniques, can reliably enhance the compressive strength of lightweight concrete in both conventional and recycled aggregate systems.

3.2 Flexural strength

The flexural strength of fiber cementitious composites is a crucial criterion in determining their tensile strength. Ductility increases with flexural strength [75,131]. The flexural strength of alkali-resistant PPF was found to decrease, whereas tensile strength increased [26,144]. The effectiveness of PPF and nanosilica in enhancing the flexural strength of concrete has been investigated in various studies. Comparisons have been made between mixes containing PPF and nanosilica, mixes with either PPF or nanosilica alone, and control mixes without either additive. PPF outperforms control mixes without fiber and nanosilica in enhancing the flexural strength. Furthermore, the combination of PPF and nanosilica has been found to offer even greater improvements in flexural strength. These findings highlight the potential benefits of using PPF and nanosilica as additives for improving the flexural strength of concrete, which can have important implications for the performance and durability of concrete structures. Furthermore, the specific mix design and conditions of use should be considered when selecting and optimizing the use of additives for concrete reinforcement. Fiber reinforcement is commonly used to boost the flexural characteristics and postpeak appearances of comparable composites by reducing the propagation of fractures under various mechanical loads [145].

When matched to other mixes, the ones containing 0.5% PPF demonstrate suitable and higher performance in terms of flexural tensile strength. Furthermore, when comparing the strength performance of test specimens with and without PPF, a difference of approximately 6.5 and 4.5 MPa can be observed when using alkali ratios of 2.5 and 1.5, respectively. Furthermore, when comparing 1% PPF specimens to 0.5% PPF specimens without nanosilica, the flexural tensile strength of the latter group is lower [26].

Amran et al. [135] observed that after 28 days, the flexural strength reaches 15.2 MPa, which is 217 percentage points more than the control nonreinforced composition and 111 percentage points higher than the control reinforced composition. This result proves that the improved flexural strength is due to a combination of the fiber itself and the created polymineral modifier. In addition, fibers have been shown to increase the flexural strength of concrete, as reported by Meena and Ramana [136]. Compared with regular concrete, the flexural strength of fiber-reinforced concrete is greater by over 7.53% after 28 days. Flexural strength is represented as PPF content using a nonlinear regression technique [146].

For flexural strength, the optimal percentage of PPF in the sample was found to be 2.5%. The consequence of fiber bridging across the cracks accounted for the increase in flexural strength shown with increasing PPF concentration up to 2.5%. Overshooting the optimal PPF level resulted in a steady decline in the flexural strength due to problems in mixing and a lack of uniform fiber distribution, which in turn reduced workability and increased porosity. For instance, the flexural strength of a sample with 8 M NaOH and 2% Fc was 1.27 MPa with 0% PPF, 1.47 MPa with 1% PPF, 1.88 MPa with 2% PPF, 2.19 MPa with 2.45% PPF, and 2.22 MPa with 3.0% PPF [67].

Transverse loads applied to a plain beam are used to measure the flexural strength of concrete. Flexural strength is determined using a three-point loading approach. Srinivas et al. [80] observed that the maximum flexure of lightweight concrete is obtained at 1% PP fiber, and with increasing fiber%, the strength decreased (Figure 20).

![Figure 20

Flexural strength of PF [80].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_020.jpg)

Flexural strength of PF [80].

According to Salehi et al. [79], the flexural strength and the postcracking behavior of LWC are enhanced when fiber is added. As a result, the bearing capacity is improved because the fiber stops the cracks from spreading and prevents them from breaking suddenly. The addition of 0.5% fiber improved the flexural strength. Given the balling phenomena that enhance porosity and heterogeneity in the concrete matrix, flexural strength might be expected to decrease if the percentage of fiber used is greater than the optimal amount.

Furthermore, Salehi et al. [79] reported that 0.5 and 1% fiber concentrations in bacterial specimens resulted in increased flexural strength. Increased bacterial activity in the fiber-containing group led to greater flexural strength.

When compared to ordinary concrete, all of the combinations tested showed considerably higher flexural strength values, ranging from 47 to 110%. Furthermore, the flexural strength was dependent on the expression Vf*(l/d). However, post-crack behavior was substantially linked with the fiber type. For comparable values of Vf*(l/d), the postcrack behavior appeared to be governed by the fiber form, even among steel fiber blends. Polypropylene blends with oppositely hooked fibers demonstrated similar post-crack behavior, as noted by Badogiannis et al. [93]. However, considerable postcrack strength and toughness values appeared to result from the use of all fiber kinds and shapes investigated.

As shown in Figure 21, flexural strength increases of 10.2 and 43.4% were reported for 7-day and 28-day bimaterial concrete, respectively, as compared with the standard mix with fibers [147]; the strength of the interface concrete increased by 13.1–45.9%. The primary function of the fiber is to strengthen the concrete’s resistance to cracks, and their “bridge action” in the presence of voids makes the material stronger than regular or bilayer mixes. Strength is reduced by 22.60% when the fiber mix is added to concrete, which is already rather strong. The creation of a void between conventional and bilayer concrete may account for some of the strength loss.

![Figure 21

Flexural strength of bimaterial concrete [147].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_021.jpg)

Flexural strength of bimaterial concrete [147].

Using bilayer fiber concrete led to remarkable results and increased flexural deflection strength. In plain concrete, a fracture appears immediately after a load increase, and it widens and deepens as the load decreases. Afterward, the load is increased again because of the fiber’s bridging effect [147]. The load-bearing capacity of the fiber is increased over a standard mix, preventing the matrix from splitting under the strain [148]. Shilkrot and Srolovitz [149] found that as the fiber level increases, the performance of the fiber deteriorates and becomes more challenging because they are no longer interacting with the cement matrix.

According to the findings of a flexural strength test conducted by Ramana et al. [147], the specimen’s strength increased in comparison with plain concrete but decreased in comparison with fiber filling the entire volume of the specimen. The creation of cracks could be the result of a weak connection between various materials.

Overall, the flexural strength performance of PPF-reinforced concrete shows considerable enhancement across various mix designs and testing conditions, though the optimal dosage varies between 0.5 and 1%, as presented in Table 10. Most studies reported a significant increase in flexural strength with PPF addition compared to control mixes, with maximum strength typically achieved at 0.5–1% PPF. For example, Meena and Ramana [137], Salehi et al. [79], and Xie et al. [37] observed the highest strength at 0.5% or 1% PPF, attributing the improvements to enhanced crack-bridging mechanisms and improved ductility. However, some studies reported peak flexural strength at higher fiber dosages, up to 2.5% [67], suggesting variability due to factors such as fiber dispersion, mix proportions, alkali content, and use of supplementary materials like nanosilica. Discrepancies, such as reduced strength at 0.9% or 1% PPF in certain mixes [112,137], were often attributed to poor workability, fiber balling, and increased porosity at higher dosages. The synergistic effect of combining PPF with nanosilica has also been found to enhance flexural strength beyond what is achievable with either additive alone [26]. Therefore, while 0.5–1% PPF generally offers optimal balance between strength gain and mix integrity, the variability across studies highlights the importance of considering mix design parameters, fiber geometry, and supplementary cementitious additives when optimizing for flexural performance.

Flexural strengths of PPF lightweight concrete according to previous studies

| Ref. | Field of use | Mix proportion | PPF % | Flexural strength (MPa at day 28) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmed et al. [112] | High strength PPF concrete | — | 0 | — | 4.53 | — |

| 0.15 | — | 4.76 | — | |||

| 0.30 | — | 4.8 | — | |||

| 0.60 | — | 4.9 | — | |||

| 0.90 | — | 4.34 | — | |||

| Srinivas et al. [80] | Lightweight concrete with PPF | 0.45: 1: 1.41: 2.16 | 0.5 | 1.65 | 3.23 | — |

| 1 | 1.90 | 3.82 | — | |||

| 1.5 | 1.40 | 2.80 | — | |||

| Meena and Ramana [137] | PPF-reinforced concrete | — | 0 | — | 4.65 | — |

| 0.2 | — | 4.79 | — | |||

| 0.35 | — | 4.82 | — | |||

| 0.5 | — | 5 | — | |||

| 0.75 | — | 4.57 | — | |||

| 1 | — | 4.38 | — | |||

| Orouji and Najaf [142] | PPFs on flexural and compressive strengths | 0.30: 1: 2.78: 0 | 0 | — | 15.5 | — |

| 0.5 | — | 16.4 | — | |||

| 1 | — | 17.3 | — | |||

| 1.5 | — | 18.6 | — | |||

| Xie et al. [37] | Lightweight concrete reinforced with PPFs | — | 0 | — | 3.9 | — |

| 0.5 | — | 4.7 | — | |||

| 0.75 | — | 5.3 | — | |||

| 1 | — | 5.8 | — | |||

| Salehi et al. [79] | Lightweight concrete reinforced with PPF | 0.43: 1: 0.99: 1.19 | 0 | — | 3.55 | — |

| 0.5 | — | 4.25 | — | |||

| 1 | — | 4.02 | — | |||

| Qin et al. [3] | PPF fabric-reinforced concrete | 0.75: 1: 3.62: 2.67 | 0.6 | — | 5.72 | 5.78 |

| 0.9 | — | 5.90 | 5.99 | |||

| 1.2 | — | 5.53 | 5.76 | |||

| 1.5 | — | 5.07 | 5.38 | |||

| Hussein et al. [26] | Alkali-activated mortar | — | 0.5% PPF | — | 17.5 | — |

| 0.5% PPF + 1% NS (nanosilica) | — | 12.75 | — | |||

3.3 Failure mode of PF lightweight concrete

The toughness and failure morphology of a fracture specimen can be considerably altered by the inclusion of fiber, although these effects depend on the elastic modulus of the fiber and the method of incorporation. Yang et al. [96] found that low-modulus fiber aids in the management of microcracks, whereas high-modulus fiber aids in the management of macrocracks. In addition, Yang et al. [96] reported that when PPF is incorporated into the specimens for the type-I shear fracture test, the resulting crack is fine. All fiber-doped samples also retain their structural integrity after being fractured. By contrast, the initial fractures of most specimens for a type-II shear fracture test grow steadily along the reserved crack tips. The expansion path shifts, and the fracture type is a mixture of types I and II due to the varied fiber involved and the effect of type-I strain.

The addition of fiber to concrete has always been driven by the need to improve the material’s performance in finished constructions. Various types of fibers have been used in construction, but steel and polypropylene dominate. Steel fiber, for instance, is known to increase a material’s fracture energy, creep and shrinkage resistance [150,151], impact resistance, freeze–thaw resistance, abrasion resistance, and fatigue resistance, among other desirable properties. Steel fibers have limited application in concrete because they cannot prevent spalling even at high temperatures [152].

PPF has a low melting point; thus, when the temperature is beyond 170°C, the fiber melts and generates more pores in the concrete matrix, which allows the accumulated vapor to be evacuated more efficiently, resulting in lower pore pressure [153].

When polypropylene melts, the pore pressure of plain concrete always becomes larger than the pore pressure of similar concrete with the addition of PPF [152]. This benefit is crucial for high-risk buildings that could be destroyed by fire. Many experiments have shown that the presence of PPF degrades the residual mechanical qualities of concrete subjected to high temperatures [154]. Thus, most ongoing studies focus on hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete, which combines steel and PPF.

Fibers enhance flexural strength and substantially improve toughness. In trials with polypropylene–BF-reinforced concrete, the incorporation of fibers enhanced the material’s flexural strength [155]. Under bending stress, fibers significantly decreased fracture propagation, exhibited increased ductility, and hence enhanced the material’s toughness (Table 11). They also provide a convoluted fracture propagation pathway. This augments resistance to fracture propagation and improves the overall toughness of concrete. In contrast to traditional concrete, hybrid fiber concrete exhibits more uniform cracking, hence diminishing localized crack development and enhancing energy dissipation. Test findings indicate that hybrid fibers can markedly improve the fracture toughness of concrete.

| Fiber concentration | Crack pattern |

|---|---|

| Without fiber and PPF-based specimens (compressive strength): |

|

|

|

| Hybrid fiber (PPF + steel): |

|

|

|

| Hybrid fiber (PPF + steel after flexural strength test) |

|

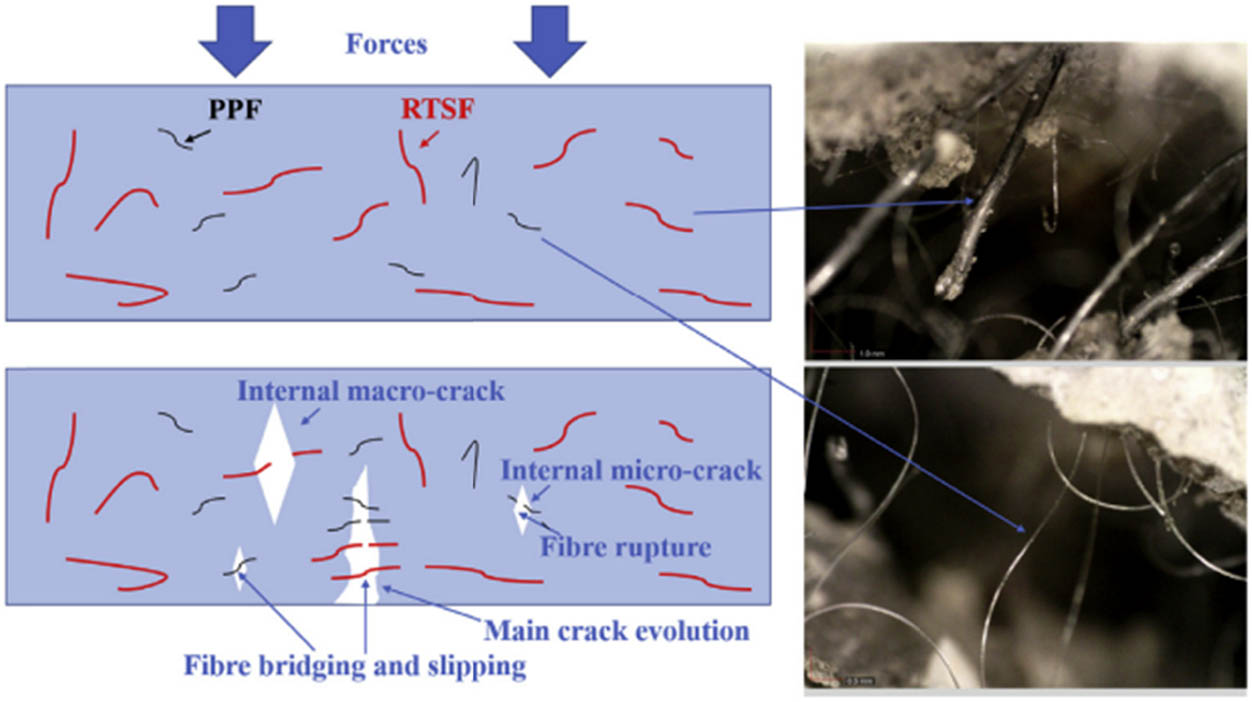

The flexural schematic diagram in Table 11 illustrates the primary fiber bridging process of hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete under flexural loading: Initial loading causes interior micro or macro fractures due to inherent flaws and shrinking, but no outward major cracks form [156]. Randomly dispersed fibers can bridge cracks and relieve matrix tension. Due to its poorer matrix contact and lower tensile characteristics, PPF can only withstand the formation of tiny microcracks, resulting in lower pull-out loads. Loading causes the primary fracture to propagate, while fiber bridging enhances flexural behavior. Fiber sliding and de-bonding may occur at the PPF–matrix interface due to minimal contact between fiber and the matrix. Fiber rupture occurs when stress exceeds the reinforcing limit and the fiber is strongly attached to the matrix (e.g., at the steel fiber–matrix contact). Both approaches can improve post-cracking performance, particularly energy absorption capacity. However, energy absorption depends on parameters like fiber quantity and spacing surrounding the fracture. Overall, fiber behavior significantly improves FRC flexural behavior, with greater enhancement when more fibers align perpendicular to the loading direction.

3.4 Stress–strain behavior

Wu et al. [159] suggested that the ductility of core concrete can be increased through a combination of transverse reinforcement and fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete. Ductility refers to the ability of a material to deform under stress without breaking. In the case of concrete columns, ductility is important because it allows the column to absorb energy during an earthquake or other severe loading event without collapsing. Wu et al. [159] also noted that columns reinforced with fibers saw a 50% increase in ductility when the spiral spacing was reduced from 45 mm to 30 mm. This decrease suggests that the use of fiber-reinforced concrete can be an effective method for increasing the ductility of concrete columns. The reduction in spiral spacing likely contributed to the increased ductility by increasing the amount of transverse reinforcement in the column. However, Wu et al. [159] also noted that unreinforced columns saw almost no benefit from the change of spiral spacing. This finding highlights the importance of reinforcement in increasing the ductility of concrete columns. Without reinforcement, the concrete may not be able to withstand the forces acting on it during a severe loading event. Finally, no remarkable increase in peak stress in the column was observed due to the reduction in spiral spacing. This consideration is crucial because excessive stress can lead to the failure of the column. The fact that the difference between the two tie spaces was negligible suggests that the reduction in spiral spacing did not considerably increase the stress on the column. Overall, Wu et al. [159] suggested that a combination of transverse reinforcement and fiber-reinforced lightweight concrete can be an effective method for increasing the ductility of concrete columns. However, it also highlights the importance of proper reinforcement and the need to avoid excessive stress on the column.

Libre et al. [44] concluded that PP fiber did not affect concrete compressive strength. PP fiber slightly improved the concrete’s energy absorption and durability under compression. Moreover, Libre et al. [44] highlighted that the primary objective of adding fiber to LWC is to enhance its ductility and postpeak behavior. In this regard, PP and steel fiber can expand the ductility and postpeak behavior of the concrete. The descending part of stress–strain curves in concrete, which represents the postpeak behavior, is mainly affected by the addition of steel fiber. However, the ascending part of the curve, which represents the elastic behavior of the concrete, is less influenced by the addition of steel fiber. In summary, Libre et al. [44] suggested that the addition of fiber can remarkably develop the compressive strength, ductility, and postpeak behavior of LWC. Although PP fiber have a relatively minor effect on the compressive strength of the concrete, they can enhance its energy absorption and toughness characteristics.

An increase in the foam agent content reduces mass loss and increases compressive and flexural strengths of foam concrete when the material is subjected to high temperatures, cooled by air and water [160]. High temperature has less of an effect on foam concrete because of the enhanced porosity made possible by the improved foam agent content. Cement content has a considerable effect on the compressive and flexural strengths of foam concrete, with more cement content resulting in lower mass loss and higher strengths across the board. However, Gencel et al. [160] stated that a higher proportion of PPF increases the mass loss of foam concrete. Cracks and interconnected pores can be seen in SEM images of samples after they have been heated to high temperatures and subjected to thermal stresses caused by the breakdown of calcium silicate phases.

PPF fabric-reinforced concrete had a uniaxial compressive constitutive model, which was established by Qin et al. [3]. The correlation coefficients b, αa, λ, β, and αd for PPF-reinforced concrete at varying ages and fabric contents were calculated using the constitutive equation for uniaxial compression (Figure 22). The stress–strain curve of PPF fabric-reinforced concrete was also investigated, as reported by Qin et al. [3]. The falling part of the stress–strain curve was more affected by the fabric dosage and curing age than the growing half. This result is a direct result of the fact that as fabric percentage increases, the material’s toughness and the value of d drops increase, and the steepness of the curve’s decline is mitigated. As the curing age of a material increases, its internal water content drops, its brittleness grows, its αd value increases, and the slope of the corresponding descending section of the curve steepens.

![Figure 22

Diagram illustrating the constitutive relationship that is impacted by the age and amount of fabric and fiber [3].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0141/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0141_fig_022.jpg)

Diagram illustrating the constitutive relationship that is impacted by the age and amount of fabric and fiber [3].

3.5 Ductility

Orouji and Najaf [142] found that the glass fiber-reinforced plastic (GFRP) rebars had lower flexural strength than steel rebars, which resulted in lower ductility and overall strength in specimens reinforced with GFRP rebars. However, the addition of fiber proved to be beneficial in compensating for this weakness. By increasing the amount of fibers used, the ductility of hybrid beams was enhanced. For example, using 1.5% fiber in combination with GFRP rebars resulted in a fully ductile beam that exhibited flexural strength similar to that of specimens reinforced solely with fiber but without any rebars.

Orouji and Najaf [142] highlighted the importance of carefully considering the properties of different reinforcement materials and how they interact with one another. While GFRP rebars may have certain advantages over traditional steel rebars, their lower flexural strength can affect the overall performance of a reinforced structure. However, by using a combination of materials and adjusting the amount of fibers used, a balanced and effective reinforcement system can be achieved.

Fiber reinforcement is a commonly used method to enhance the properties of lightweight concrete, such as its flexural capacity, toughness, post-failure ductility, and crack control. Among the different types of fiber available, PPF is often preferred for its effectiveness in providing thermal insulation and improving ductility. PPF is also popular due to its affordability and excellent resistance to environmental factors [86,161].

Wang et al. [86] mentioned that the addition of fiber to lightweight concrete can help mitigate the inherent weaknesses of this material, such as its low tensile strength and brittle behavior. IN particular, PPF can improve the toughness of the concrete by absorbing energy during deformation and preventing the propagation of cracks. This improvement can lead to a more ductile behavior, which is desirable in many applications, including earthquake-resistant construction. In summary, fiber reinforcement, especially using the PP fiber, is a widely recognized and effective method for improving the properties of lightweight concrete. Its cost effectiveness, resistance to environmental factors, and ability to enhance ductility and crack control make it a popular choice in the construction industry.

Numerous parameters, including high-performance PPF content, stirrup ratio, and shear span to depth ratio, can affect the failure mechanism of LWC beams, according to Xiang et al. [162]. It has been proven that adding more high-performance PPF to the concrete mix will effectively halt the spread of diagonal fractures. By altering the fiber content and stirrup ratio, the specimen’s failure mode can also be changed. When specimens break under diagonal tension with evident brittleness, they can change from shear compression failure to shear bending failure with enhanced ductility. This change demonstrates how fiber and stirrups may help a design achieve a less brittle failure mode, which is frequently desired in structural engineering.

Ekanayake et al. [163] reported that fiber added to concrete can boost the material’s strength and flexibility. To this end, this research looked into the outcomes of reinforcing concrete beams with either macrosynthetic polypropylene (MSPP) fiber, PPF, or both. Findings revealed that the addition of MSPP fiber enhanced beam load capacity by 13%, the addition of MSPP and PPF raised it by 6%, and the addition of PPF alone increased it by 5%. In addition to enhancing the initial stiffness by 3% and the ductility by 12%, MSPP fiber was added to the beam to make it stronger than the fiber-reinforced concrete alternative. However, PP fiber had only a moderate effect on the beam’s ductility and initial stiffness.

The beams’ failure mode varied depending on the length of the lap splices. Failure occurred before the expected performance was reached when the lap splice length was insufficient (20ϕ or 0.5 lb). However, when a sufficient amount of lap splice (40ϕ or 1.0 lb) was used, the beams did not fail in the middle even when subjected to a displacement of 130 mm. The beams in this instance behaved ductilely. Overall, Ekanayake et al. [163] demonstrated that the addition of MSPP and PP fiber can improve the load capacity and ductility of concrete beams. However, the effect of PP fiber on the ductility and initial stiffness was found to be limited. Additionally, providing sufficient lap splice length is crucial to ensuring the desired performance of the beams.