Abstract

The environmental burden of Portland cement production, a major contributor to global CO2 emissions, calls for innovative material solutions in concrete technology. This study examines the morphological and microstructural characteristics of sustainable concrete incorporating crumb rubber (CR), fly ash (FA), silica fume (SF), and marble slurry powder (MSP). Fifteen hybrid mix designs were prepared and characterized using X-ray diffraction, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, field emission scanning electron microscopy, and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy to investigate phase composition, hydration products, and interface morphology. The optimal mix containing 5% SF, 10% MSP, and 15% FA exhibited significant portlandite reduction (∼22–25%) and enhanced amorphous C–S–H gel formation, indicating strong pozzolanic interaction. MSP contributed to pore refinement and improved interfacial bonding, while CR, despite its non-reactive nature, enhanced the ductility and energy absorption potential of the matrix. Elemental mapping confirmed uniform distribution of Ca and Si, supporting improved hydration product formation and microstructural integrity. These findings demonstrate the synergistic effect of CR and supplementary cementitious materials in improving concrete’s internal structure and contribute to ongoing efforts to reduce the construction industry’s carbon footprint.

Abbreviations

- BSE

-

backscattered electron

- CaO

-

calcium oxide

- Ca(OH)2

-

portlandite

- C–A–S–H

-

calcium aluminosilicate hydrate

- C–S–H

-

calcium silicate hydrate

- C3S

-

tricalcium silicate

- C4AF

-

tetracalcium aluminoferrite

- CR

-

crumb rubber

- EDS

-

energy dispersive spectroscopy

- ELTs

-

end-of-life tires

- FESEM

-

field emission scanning electron microscopy

- FEGSEM

-

field emission gun-scanning electron microscope

- FTIR

-

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- FA

-

fly ash

- HPC

-

high-performance concrete

- ITZ

-

interfacial transition zone

- MSP

-

marble slurry powder

- OPC

-

ordinary Portland cement

- R

-

rubber (used in mix labels)

- SCMs

-

supplementary cementitious materials

- SF

-

silica fume

- SEM

-

scanning electron microscopy

- UHPC

-

ultra-high-performance concrete

- XRD

-

X-ray diffraction

1 Introduction

Concrete is the most widely used construction material across the globe due to its strength, versatility, and cost-effectiveness. However, its production, particularly that of Portland cement, is a major contributor to carbon emissions. Cement manufacturing alone accounts for approximately 7–8% of global CO2 emissions, raising critical environmental concerns [1,2]. The environmental impact has necessitated the investigation of sustainable alternatives to conventional concrete production [3,4]. A viable strategy entails the integration of industrial by-products and supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) to improve the sustainability and performance of concrete [5]. This study integrates SCMs, such as silica fume (SF), fly ash (FA), marble slurry powder (MSP), and crumb rubber (CR), to enhance concrete properties. While SCMs are known to enhance strength, microstructure, and durability, CR contributes to waste management and improves ductility. Although these materials have been widely studied individually, their combined impact on the internal structure of concrete requires further investigation. This research explores the combined effects of these materials on the microstructure and morphology of concrete.

CR, produced from discarded tires, provides a remedy for the escalating environmental issue associated with waste tyres [6,7]. The incorporation of CR into concrete not only mitigates waste disposal issues but also enhances durability and mechanical qualities, decreasing dependence on conventional aggregates and fostering resource efficiency within a circular economy paradigm. The growth of the automotive sector has led to a significant increase in the quantity of end-of-life tires (ELTs), with global estimates surpassing one billion ELTs disposed of each year. Approximately one billion ELTs are generated annually worldwide [8], with another report estimating around 4 million tyres reaching scrap standards every day [9]. India alone generates 1.5 million tons of ELTs per year, although only a small percentage gets recycled [10]. The intricate composition of tyres, comprising carbon black, synthetic rubber, and steel, complicates disposal [11,12] while simultaneously offering prospects for resource recovery [13]. The efficient recycling and incorporation of CR into concrete can reduce landfill waste and promote sustainable practices [11,14].

Recent investigations have expanded the functional scope of CR in cementitious systems, demonstrating that its benefits go beyond waste mitigation. Incorporating up to 30% CR into geopolymer composites significantly lowered thermal conductivity, reaching values as low as 0.43 W/m K, while still maintaining compressive strengths in the range of 25–52 MPa, sufficient for structural applications [15]. Another study applied response surface methodology to optimize both the content and particle size of CR in RC-based binders, achieving a compressive strength of 41.9 MPa alongside improved insulation performance [16]. Multi-criteria decision-making and conjugate heat transfer analysis were used to evaluate rubberized mortar blocks, identifying a 10% CR mix as optimal for balancing mechanical strength, thermal insulation, and embodied energy [17]. These studies emphasize that CR can serve as a viable modifier for enhancing not just ductility, but also the thermal and sustainability attributes of concrete systems.

FA, a byproduct of coal combustion in thermal power plants, presents environmental hazards when landfilled and yet functions as a promising SCM for concrete [18,19]. As a partial substitute for cement, FA improves workability, durability, and strength, while decreasing hydration heat, rendering it suitable for extensive applications [20,21]. Notwithstanding its benefits, difficulties such as diminished pozzolanic reactions and quality inconsistencies arising from variations in coal sources require creative strategies, including hybrid systems using additional SCMs such as SF [22,23]. The effective use of FA diminishes dependence on virgin resources and lessens its environmental impact, promoting resource-efficient building [24].

SF, a byproduct of the silicon and ferrosilicon alloy industries, is distinguished by its elevated silicon dioxide (SiO2) content and ultrafine particles, which improve concrete properties via pozzolanic reactions [25,26,27,28]. Its application as an SCM has shown considerable advantages, such as increased mechanical strength, diminished permeability, and augmented durability [29,30]. The small particle size of SF, however, elevates water requirements, necessitating the incorporation of superplasticizers for optimal workability [31]. SF, significantly smaller than cement particles, serves as a filler, improving the packing density of the concrete matrix. The principal chemical interaction is the pozzolanic process, in which it combines with calcium hydroxide from cement hydration to generate supplementary calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H). The enhanced production of C–S–H augments concrete strength and diminishes permeability [32,33]. SF is widely utilized in high-performance concrete (HPC) and self-compacting concrete (SCC), enhancing structural components including bridge decks, maritime constructions, and industrial floors [34,35,36,37].

MSP, produced during marble processing, is an alternative sustainable SCM option. Marble, a metamorphic rock esteemed for its beauty and resilience, produces significant waste during extraction and processing, resulting in environmental issues such as air pollution and soil obstruction [38,39], along with respiratory diseases and particle deposition on vegetation [40]. MSP has been employed to improve concrete characteristics by filling voids, decreasing porosity, and augmenting compressive strength [41,42]. It may substitute fine aggregates, aid in cement manufacture, and be utilized in brick and tile manufacturing, offering eco-friendly options for waste management and resource conservation [43].

In addition to these material-specific benefits, recent studies have explored how blending multiple waste-based materials can lead to optimized binders with reduced environmental footprint. One study demonstrated that combining date palm ash and eggshell powder in concrete can significantly reduce porosity and embodied CO2 emissions, while maintaining mechanical performance through improved hydration synergy [44]. Another investigation used response surface methodology to optimize ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) mixes incorporating ultrafine FA and metakaolin, achieving compressive strength of 164 MPa with reduced carbon emissions and cost [45]. A related study compared UHPC and ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete systems and found that geopolymer-based formulations achieved up to 70% reduction in CO2 emissions and 64% cost savings, with comparable early strength and improved microstructural compactness [46]. These findings highlight the broader potential of waste material hybridization to support sustainability goals in concrete design, even if some systems differ chemically from conventional cement-based mixes.

In addition to mitigating CO2 emissions, the valorization of waste materials such as CR, MSP, FA, and SF contributes to material circularity and cost efficiency in concrete production. These hybrid systems have shown potential to support sustainable construction practices through reduced resource consumption and waste diversion [47]. Moreover, life cycle assessment studies have shown that incorporating such SCMs can reduce embodied carbon emissions by 25–70%, extend service life, and improve environmental performance relative to conventional cement-based mixes [48,49,50]. These findings reinforce the role of circular economy strategies in promoting low-impact, cost-effective, and scalable alternatives for infrastructure applications [51,52,53].

In our previous study [54], the mechanical and durability properties of concrete mixes incorporating CR and SCMs were systematically investigated, demonstrating enhanced sulphate resistance, reduced water absorption, and satisfactory strength retention. However, the underlying microstructural mechanisms responsible for these improvements, particularly the nature of hydration phases, elemental distribution, and interfacial transitions within the matrix, remained unexplored. This study addresses that gap through detailed morphological and mineralogical characterization using X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), and energy dispersive spectroscopy EDS).

The objective is to evaluate how the combined presence of CR, SF, FA, and MSP alters hydration behaviour, matrix continuity, and porosity at a microstructural level. The intended outcome is to establish a clear correlation between these transformations and the enhanced performance reported earlier. The novelty lies in demonstrating how the synergistic use of these materials contributes not just to external properties like strength and durability, but also to the internal structure–performance relationship that governs sustainable HPC.

2 Materials used and their characterization

The materials used in this study include ordinary Portland cement (OPC, 43 grade) obtained from Ultratech Cement Limited. Natural river sand conforming to Zone II of BIS 383:1970 [55] was used as fine aggregate, while crushed basalt rock of 10 and 20 mm sizes, mixed in a 60:40 ratio, served as coarse aggregates. SCMs and CR were selected based on their physical properties and suitability for improving concrete performance.

CR, procured from Sai Tires, Bhopal, ranged in size from 0.1 to 4.76 mm and was free from metallic impurities. SF, sourced from Metro Chemicals, Bhopal, complied with BIS 15388:2003 [56] and ASTM C1240-20 [57], with 99.2% of particles finer than 45 µm. FA, obtained from Sarni Thermal Power Plant, met the requirements of BIS 3812:2003 [58], with 82% of particles passing through the 45 µm sieve. MSP was collected as wet waste from Taj Stone Company, oven-dried, and sieved through a 75 µm mesh to ensure uniformity. A polycarboxylate ether-based superplasticizer (SikaPlast-5202 NS) [59] was used to enhance workability. All mixing and curing operations were performed using municipal tap water with a neutral pH of 7.

The standard consistency, initial setting time, final setting time, and soundness of OPC are determined to be 29%, 126, 240, and 1 mm, respectively. The chemical composition of the materials is presented in Table 1, and their physical specifications are detailed in Table 2.

Chemical composition of materials used [54]

| Compounds | OPC | MSP | FA | SF | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 (%) | 30.59 | 6.11 | 55.94 | 96.83 | 2.19 |

| CaO (%) | 48.24 | 45.86 | 2.90 | 0.91 | 17.21 |

| Al2O3 (%) | 3.65 | 0.94 | 23.81 | 0.69 | — |

| Fe2O3 (%) | 3.49 | 0.80 | 6.10 | 0.76 | 1.04 |

| K2O (%) | 0.61 | 0.24 | 1.02 | 0.45 | — |

| MgO (%) | 0.89 | 6.59 | 1.34 | 0.73 | — |

| Na2O (%) | 0.05 | — | 0.60 | 0.18 | — |

| P2O5 (%) | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.38 | 0.48 | — |

| ZnO (%) | — | — | — | — | 55.68 |

| TiO2 (%) | 0.34 | 0.08 | 1.52 | 0.14 | 0.50 |

| MnO (%) | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | — |

Physical specifications of materials used [54]

| Physical properties | OPC | MSP | FA | SF | CR | Sand | Coarse aggregates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Form | Powder | Powder | Powder | Powder | Granules | Granules | Aggregates |

| Grain size (µm) | 100% < 90 µm | 92% < 75 µm | 82% < 45 µm | 100% < 600 µm | 75–4,750 µm | 150–4,750 µm | 100% < 20,000 µm |

| Colour | Dark grey | Off-white | Light grey | Grey | Black | Yellowish | Blackish |

| Specific gravity | 3.16 | 2.7 | 2.45 | 2.23 | 0.85 | 2.65 | 2.8 |

| Loss on ignition (%) | 3.10 | 36.25 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 4.5 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

Figure 1 displays the X-ray diffractograms for OPC, CR, SF, MSP, and FA, elucidating the chemical compositions of these compounds. The diffractogram peaks at 2θ in the case of OPC (Figure 1a) reveal the presence of alite (Ca3SiO5), belite (Ca2SiO4), celite or C3A (3CaO·Al2O3), felite or C4AF (4CaO·Al2O3·Fe2O3), and gypsum. The data unequivocally demonstrate significant quantities of lime, silica, and alumina oxides, aligning with previous research [60,61].

The XRD analysis of river sand (Figure 1b) reveals Quartz (SiO2) as the predominant crystalline substance. Crystalline silicate phases may facilitate the formation of C–S–H gel or calcium aluminium silicate hydrate in concrete. The presence of Quartz and Mica aligns with findings from earlier investigations [62].

XRD examination of CR (Figure 1c) indicated the presence of calcite (CaCO3) and zinc oxide (ZnO). Zn-based compounds are probably associated with tyre de-moulding agents used during the manufacturing and processing stages [63]. The diffractogram also shows a broad hump attributed to the amorphous carbon black phase, consistent with earlier findings [64].

The XRD analysis of SF (Figure 1d) reveals crystalline peaks at 2θ values of 22.0364, 24.5848, 26.8298, 30.6928, 31.7445, 35.9109, and 44.5875, indicating that Quartz is the predominant crystalline material, while the remainder consists of an amorphous phase, thus, confirming that Quartz is the primary component of SF, as documented by earlier investigations [65].

Analysis of the XRD data for MSP (Figure 1e) verifies the existence of calcite (CaCO3), dolomite (CaCO3·MgCO3), silica (SiO2), and sodium acetate (CH3COONa). The predominant mineral phases in MSP were calcite and dolomite. MSP comprises minor quantities of contaminants, including magnesium carbonate (MgCO3), iron oxide (Fe2O3), silica (SiO2), and several trace elements [60,66,67].

The XRD of FA (Figure 1f) reveals peaks corresponding to quartz (SiO2) and mullite (3Al2O3·2SiO2). The principal components of FA comprise silicon and aluminium oxides, together with other metallic oxides and residual carbon, as detailed in several sources [60,68,69].

3 Equipment and software used

At MANIT, Bhopal, XRD and FTIR were employed. The XRD, a Bruker Corp. model AXS D2 Phaser, operating with CuKα radiation of wavelength 1.54 Å and a scanning range of 10–110°, was used to analyse the crystalline structure of materials, identifying phase composition and crystallographic properties. FTIR, a Shimadzu IRAffinity-1S, obtained infrared spectra of solids, liquids, and gases, identifying organic, polymeric, and some inorganic materials in concrete samples, providing insights into chemical composition and possible reactions within the concrete matrix.

At the Sophisticated Instrumentation Facility (SIF), BITS Pilani (Pilani Campus), an FESEM and an EDS were used. The FESEM, a Thermo Fisher Scientific (FEI) Apreo S, provided high-resolution imaging of concrete samples, crucial for understanding microstructural features, morphology, and surface characteristics. The EDS, an OXFORD Instruments X-MaxN, enabled elemental analysis and mapping, identifying elemental composition and distribution within concrete samples. The Sputter Coater, a Quorum Tech Q150T ES, used gold coating to enhance sample conductivity for FESEM analysis.

At the Sophisticated Analytical Instrument Facility (SAIF)/Center for Research in Nano Technology and Science (CRNTS), IIT Bombay, the EDS attached to the field emission gun-scanning electron microscopy (FEGSEM) was used. The FEGSEM, a Jeol JSM7600F, was employed exclusively for precise elemental analysis, without obtaining any images. The EDS system, an Oxford X-Max 80 mm², helped in understanding the distribution and concentration of different elements within concrete samples, essential for evaluating the impact of various waste additives.

OriginPro 2024b, produced by OriginLab Corporation, was utilized for graphing XRD patterns, enabling detailed visualization and interpretation of the crystalline structures.

Table 3 summarizes all the equipment and software used in this research.

List of equipment and software used

| Equipment | Manufacturer | Model | Location | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray diffraction | Bruker Corp. | AXS D2 Phaser | MANIT, Bhopal | Analysing crystalline structure |

| Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy | Shimadzu Corp. | IRAffinity-1S | MANIT, Bhopal | Identifying chemical composition |

| Field emission scanning electron microscope | Thermo Fisher Scientific (FEI) | Apreo S | SIF, BITS Pilani | High-resolution microstructural imaging |

| Energy dispersive spectrometer | Oxford Instruments | X-MaxN | SIF, BITS Pilani | Elemental analysis and mapping |

| Sputter coater | Quorum Tech | Q150T ES | SIF, BITS Pilani | Gold coating for FESEM analysis |

| Field emission gun-scanning electron microscope | Jeol | JSM7600F | SAIF/CRNTS, IIT Bombay | High-resolution microstructural imaging |

| Energy dispersive spectrometer | Oxford | X-Max 80 mm² | SAIF/CRNTS, IIT Bombay | Precise elemental analysis |

| ETABS software | Computers & Structures Inc. (CSI) | ETABS Ultimate | — | Structural analysis and design |

| Statistical software | IBM | SPSS Statistics 25 | — | Statistical Analysis |

| Graphing software | OriginLab Corporation | OriginPro 2024b | — | Graphing XRD and FTIR patterns |

| Computational platform | Colab | — | Running Python code for data analysis |

Summary of testing methods, types of specimens, durations of testing, and associated standards used in evaluating the properties and performance of the materials is indicated in Table 4.

Summary of microstructural and morphological characterization techniques used

| S. no. | Property investigated | Test method | Category | Specimen type | Age at testing | Standard referenced |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mineralogical composition | X-ray diffraction | Microstructural | Powdered sample (residual from cubes) | 90 days | ASTM C1365 [70] |

| 2 | Surface morphology | Field emission scanning electron microscopy | Morphological | Pellet (≈10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm) | 90 days | ASTM C1723 [71] |

| 3 | Elemental distribution | Energy dispersive spectroscopy | Microstructural | Pellet (≈10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm) | 90 days | ASTM E1508 [72] |

| 4 | Chemical bond identification | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy | Microstructural | Powdered sample | 90 days | ASTM E168 [73] |

4 Mix-proportioning and concrete preparation

In the study, the concrete mixtures were designated as R0S0M0F0, R10S5M0F0, etc. This research concentrated on the incorporation of CR and SF, alongside FA and MSP. The standard mixture was designated as R0S0M0F0, whereas later mixtures included diverse waste materials. In the modified concrete samples, CR and SF were consistently replaced at 10 and 5%, respectively, whereas the replacement proportions of MSP and FA ranged from 5 to 15%, as specified in Table 5. CR was utilized to partially substitute fine aggregates, whereas FA, SF, and MSP were employed to partially replace cement. Figure 2 illustrates the flowchart for the process of preparing rubberized concrete.

Mix-proportion quantities [54]

| Mix Label | Cementitious materials | Fine aggregates | Coarse aggregates | Super plasticizer | Water | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC | Fly ash | Silica fume | Marble slurry powder | River sand | Crumb rubber | Basalt rock | ||||||||

| kg/m3 | % | kg/m3 | % | kg/m3 | % | kg/m3 | % | kg/m3 | % | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | |

| R0S0M0F0 | 540 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 695 | 0 | 0 | 955 | 3.5 | 180 |

| R10S5M0F0 | 513 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.9 | 180 |

| R10S5M0F5 | 486 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.71 | 180 |

| R10S5M0F10 | 459 | 10 | 54 | 5 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.67 | 180 |

| R10S5M0F15 | 432 | 15 | 81 | 5 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.65 | 180 |

| R10S5M5F0 | 486 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 27 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 5.45 | 180 |

| R10S5M5F5 | 459 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 27 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 5.36 | 180 |

| R10S5M5F10 | 432 | 10 | 54 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 27 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.645 | 180 |

| R10S5M5F15 | 405 | 15 | 81 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 27 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.62 | 180 |

| R10S5M10F0 | 459 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 27 | 10 | 54 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.64 | 180 |

| R10S5M10F5 | 432 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 27 | 10 | 54 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.625 | 180 |

| R10S5M10F10 | 405 | 10 | 54 | 5 | 27 | 10 | 54 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.61 | 180 |

| R10S5M10F15 | 378 | 15 | 81 | 5 | 27 | 10 | 54 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.59 | 180 |

| R10S5M15F0 | 432 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 27 | 15 | 81 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.65 | 180 |

| R10S5M15F5 | 405 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 27 | 15 | 81 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.63 | 180 |

| R10S5M15F10 | 378 | 10 | 54 | 5 | 27 | 15 | 81 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.6 | 180 |

| R10S5M15F15 | 351 | 15 | 81 | 5 | 27 | 15 | 81 | 90 | 625.5 | 10 | 69.5 | 955 | 4.53 | 180 |

Abbreviations: R – rubber, S – silica fume, M – marble slurry powder, F – fly ash.

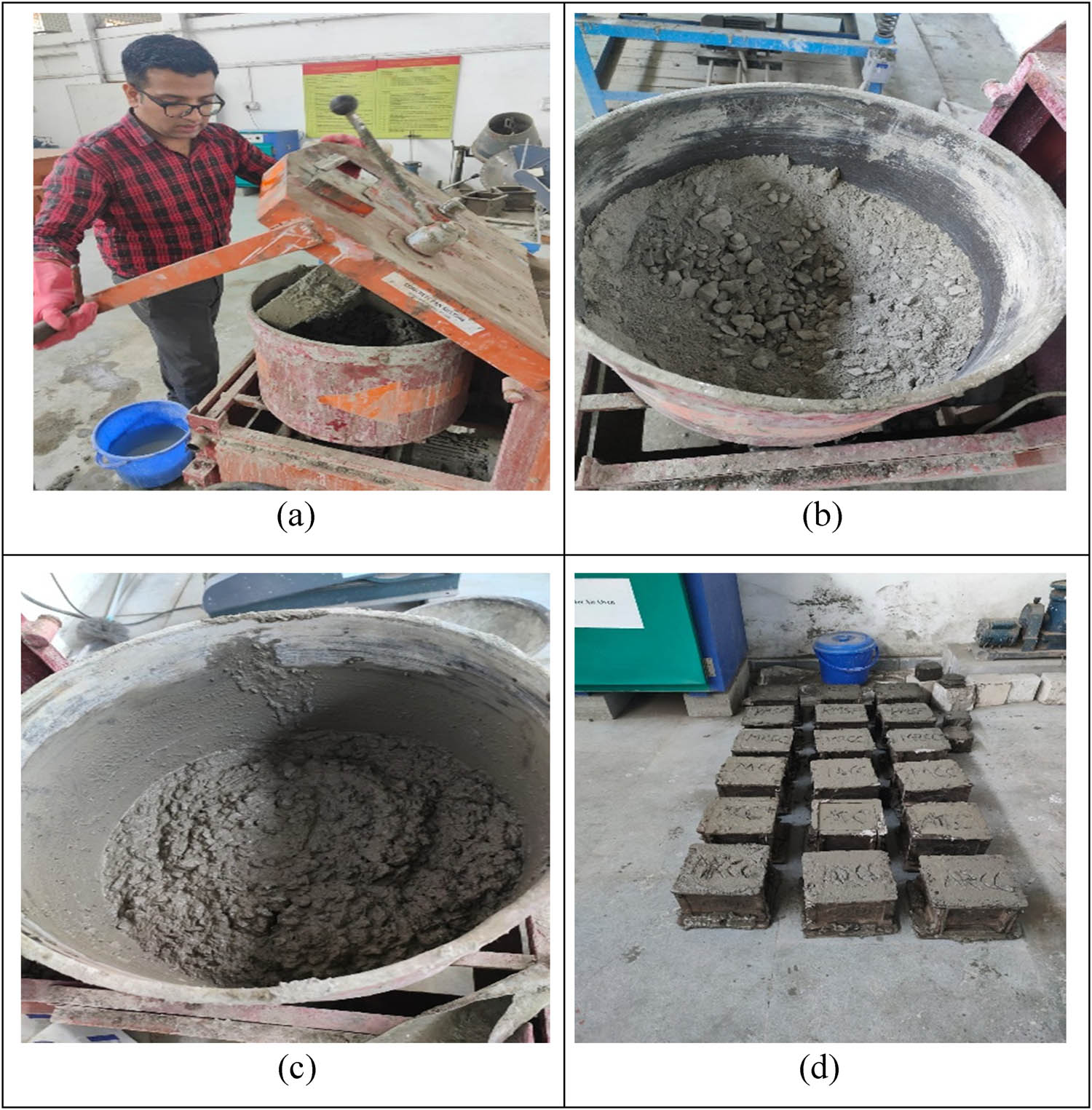

Process of rubberized concrete mixing.

The mixing process began with the dry blending of OPC, coarse aggregates (in a 60:40 ratio of 20–10 mm sizes), and fine aggregates to ensure a uniform base. CR, FA, and MSP were then added in their respective proportions as defined in the mix design. For example, in the mix R10S5M15F15, 10% of the fine aggregates were replaced with CR, while the cement content was partially substituted with 15% MSP and 15% FA by weight.

SF, however, was not included during the dry mixing phase. Instead, it was first dispersed in a portion of the mixing water to form a uniform slurry, which was subsequently introduced during the wet mixing stage along with the superplasticizer and the remaining water. This sequence was followed to ensure even distribution of the ultrafine SF particles and to prevent agglomeration. The resulting mix achieved a consistent and homogenous blend, allowing for a reliable assessment of how varying contents of CR, SF, MSP, and FA influenced the mechanical and durability characteristics of the concrete. Figure 3 illustrates the processes of concrete production, from dry mixing to specimen construction.

Stages of concrete preparation: From dry mixing to specimen formation. (a) Pan mixer for concrete mixing. (b) Dry mixing of ingredients. (c) Concrete after the addition of water. (d) Concrete mix specimens.

Figure 4 illustrates an overview of conventional and modified concrete mixes. The conventional mix, R0S0M0F0, is devoid of any waste elements, but the modified concrete mixes incorporate CR, SF, MSP, and FA in various proportions. The quantities for mix proportions are presented in Table 5.

![Figure 4

Overview of conventional and modified concrete mix ingredients [54].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0130/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0130_fig_004.jpg)

Overview of conventional and modified concrete mix ingredients [54].

The specific replacement levels for CR and SF were selected based on prior experimental optimization and alignment with trends reported in the literature. CR contents between 5 and 15% by volume have been shown to offer a practical balance between strength retention and improved ductility [74]. Similarly, SF dosages in the range of 5–10% have consistently demonstrated improvements in compressive strength, microstructural densification, and pozzolanic activity, while maintaining acceptable workability [75]. Accordingly, the 10% CR and 5% SF used in this study were chosen based on their proven synergy in enhancing the mechanical performance and durability of concrete.

These dosage levels, validated in broader literature, were further confirmed through our prior experimental investigation. The selection of rubberized mix R10S5M10F15 was based on a prior investigation involving seventeen different concrete formulations incorporating various combinations of CR, SF, MSP, and FA [54]. This mix exhibited an optimal balance of mechanical and durability performance, showing compressive strength comparable to the control mix, a 4.48% improvement in 90-day flexural strength, and reduced degradation under sulphate and acid attack. It also showed marginally lower water absorption, suggesting refined pore structure. The 10% CR replacement provided ductility and crack resistance, while 5% SF and 10% marble slurry improved matrix density and reactivity. The 15% FA content contributed to long-term strength through pozzolanic activity. Due to this synergistic performance across multiple criteria, R10S5M10F15 was selected as the most representative mix for detailed microstructural evaluation.

5 Microstructural and morphological properties

The characterization of modified concrete samples was conducted using advanced techniques to investigate their microstructural and morphological properties. Mineral composition was analysed using XRD on powdered samples (residuals from cube testing after 90 days), following ASTM C1365 [70]. Morphological features were explored using FESEM and FEGSEM on pellet samples approximately 10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm in size, in accordance with ASTM C1723 [71]. Elemental composition was assessed using EDS on the same pellet samples, following ASTM E1508 [72]. Additionally, FTIR was performed on powdered samples to determine chemical composition, adhering to ASTM E168 [73]. These techniques collectively offer a multidimensional understanding of the compositional, structural, and surface characteristics of the modified concrete. Their combined application has been widely recognized for diagnosing microstructural development, hydration progression, and durability indicators in cementitious systems [76].

Table 6 categorizes these techniques based on their specific analytical purposes and outputs, offering a comprehensive view of their relevance to the research. For instance, XRD and FTIR contributed to microstructural analysis by identifying crystalline phases and functional groups, while FESEM captured morphological characteristics such as void distribution and interfacial transition zone (ITZ) quality. EDS complemented these by quantifying elemental distribution, adding depth to the understanding of chemical interactions in modified concrete.

Overview of instrumentation techniques with purposes, visual elements, and categories

| Technique | Purpose | Visual element | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| XRD | Identify crystalline phases in the matrix | Diffraction pattern image | Microstructural |

| FTIR | Analyse functional groups and chemical bonds | FTIR spectral graph | Microstructural |

| FESEM/FEGSEM | Visualize voids and interfacial transition zones | Microstructural images | Morphological |

| EDS | Quantify elemental distribution | Elemental map | Microstructural |

5.1 Mineral composition using XRD

5.1.1 XRD spectrum analysis of conventional concrete

The XRD analysis of conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0) provides a detailed assessment of its mineralogical composition, revealing the various phases formed during cement hydration and their transformations over time. The XRD pattern, presented in Figure 5, shows a series of characteristic peaks corresponding to crystalline phases such as ettringite, calcite, portlandite, quartz, and C–S–H, as well as clinker phases including alite (C3S) and ferrite (C4AF). These phases play a pivotal role in determining the strength, durability, and stability of the concrete.

XRD pattern for conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0).

The analysis indicates the presence of ettringite (Ca6Al2(SO4)3(OH)12·26 H2O), identified by peaks at approximately 9.1, 15.8°, 18°, 20.9°, and 22.9° 2θ. Ettringite forms during the early stages of hydration when tricalcium aluminate (C3A) reacts with gypsum in the presence of water. As an expansive phase, ettringite contributes to the initial setting and early-age strength development of the concrete. Its formation is particularly significant in maintaining dimensional stability, as uncontrolled expansion due to delayed ettringite formation can compromise long-term durability.

Another prominent phase observed in the spectrum is calcite (CaCO3), with distinct peaks appearing at approximately 29.4, 39.4, 43.2, 47.5, and 48.6° 2θ. Calcite forms due to the carbonation of portlandite (Ca(OH)2 or CH), which occurs when concrete is exposed to atmospheric carbon dioxide. This carbonation process leads to the conversion of calcium hydroxide into calcium carbonate, a relatively stable phase. While the presence of calcite contributes positively to the densification of the microstructure and enhances durability, it can also reduce the alkalinity of the cementitious matrix, thereby potentially compromising the passive layer protecting steel reinforcement.

The broad hump observed between 29 and 32° 2θ is attributed to C–S–H, the primary hydration product responsible for the majority of strength development in concrete. Unlike the sharp peaks of crystalline phases, the diffuse nature of this hump highlights the semi-crystalline or amorphous structure of C–S–H. This phase forms through the hydration of tricalcium silicate (C3S) and dicalcium silicate (C2S), binding the aggregates together and providing the concrete with its load-bearing capability. The amorphous nature of C–S–H indicates its significant surface area and reactivity, which contribute to the overall strength and durability of the material.

Portlandite (Ca(OH)2), another critical hydration product, exhibits peaks around 18.1°, 34°, 47°, and 50.5° 2θ. As a byproduct of Tricalcium silicate (C3S) and Dicalcium silicate (C2S) hydration, portlandite ensures a highly alkaline environment within the concrete, with a pH above 12.5. This alkalinity is essential for protecting embedded steel reinforcement from corrosion by maintaining a passive oxide layer on the steel surface. The presence of portlandite also signifies ongoing hydration reactions, particularly in younger concrete, but its gradual consumption during carbonation or pozzolanic reactions influences the long-term chemical stability of the system.

Additionally, the XRD analysis confirms the presence of quartz (SiO2), with sharp peaks observed at 20.9°, 26.6°, 36.5°, 39.5°, 42.5°, and 50.2° 2θ. Quartz primarily originates from the fine aggregates, such as natural sand, used in the concrete mix. Known for its high hardness and chemical inertness, quartz contributes to the mechanical strength, wear resistance, and dimensional stability of concrete. The crystalline nature of quartz makes it a reliable phase for identifying aggregate sources and assessing their performance in the cementitious matrix.

The clinker phases inherent to Portland cement, particularly alite (Ca3SiO₅) and ferrite (C4AF), are also discernible in the XRD pattern. Alite, with peaks around 32.2°, 41.2°, 50.5°, 51.8°, and 52.1° 2θ, is the dominant phase responsible for early strength development in concrete. Upon hydration, alite reacts rapidly with water, forming C–S–H and portlandite, thereby contributing significantly to the initial strength gain. The ferrite phase (C4AF), identified by peaks at approximately 11.2°, 30.3°, 35.3°, and 60.2° 2θ, plays a secondary role in strength development while enhancing the workability of the cement paste.

The combination of hydration products (ettringite, portlandite, and C–S–H), secondary phases such as calcite, and the inert aggregate phases like quartz provides a comprehensive understanding of the mineralogical composition of conventional concrete. The XRD analysis highlights the dynamic transformations occurring within the concrete over time, reflecting the interplay between hydration, carbonation, and microstructural development. The presence of both crystalline and semi-crystalline phases demonstrates the complex nature of cementitious materials, where the simultaneous formation and consumption of phases govern the material’s performance characteristics.

5.1.2 XRD spectrum analysis of rubberized concrete

The XRD analysis of rubberized concrete, incorporating CR (10%) as a partial replacement for fine aggregates, along with SCMs such as SF (5%), MSP (10%), and FA (15%), reveals a complex mineralogical structure. The XRD spectrum, shown in Figure 6, identifies key crystalline phases and amorphous components contributing to the concrete’s strength, durability, and microstructural properties.

XRD pattern for rubberized concrete (R10S5M10F15).

The XRD spectrum prominently exhibits peaks for quartz (SiO2) at 20.9°, 26.6°, 36.5°, 39.5,° 42.5°, and 50.2° 2θ, reflecting its origin from natural sand and aggregates. Quartz remains chemically inert and mechanically stable, providing hardness and dimensional stability to the concrete matrix. Its presence ensures that the partial replacement of fine aggregates with CR does not compromise the overall mechanical framework. However, compared to conventional concrete, the intensity of quartz peaks may exhibit minor reductions due to the lower aggregate content, which is partially replaced by CR.

The peaks corresponding to calcite, observed at 29.4°, 39.4°, 43.2°, 47.5°, and 48.6° 2θ, indicate the carbonation of portlandite and the intentional inclusion of MSP. The addition of MSP, which primarily consists of calcium carbonate, densifies the concrete microstructure and enhances chemical stability. The increased intensity of calcite peaks compared to conventional concrete highlights the additional contribution of MSP to the overall mineralogical composition. This densification effect improves the concrete’s resistance to aggressive environmental conditions, such as sulphate and chloride ingress.

The broad hump between 29° and 32° 2θ represents C–S–H, a critical hydration product responsible for the binding properties and strength of the concrete matrix. The amorphous silica contributed by SF and FA enhances the pozzolanic reaction, consuming free portlandite to generate additional C–S–H phases. This transformation results in a refined microstructure, reduced porosity, and improved strength development over time. Compared to conventional concrete, the broader and more pronounced hump signifies an increase in amorphous content, attributable to the synergistic effect of SF and FA.

Portlandite, with characteristic peaks at 18.1°, 34°, 47°, and 50.5° 2θ, remains a prominent hydration product in the spectrum. Portlandite ensures a highly alkaline environment, essential for protecting embedded reinforcement steel. However, its intensity is relatively lower in rubberized concrete compared to conventional mixes, owing to the consumption of portlandite during the pozzolanic reactions facilitated by SF and FA. The reduction in free portlandite contributes to improved durability by mitigating carbonation and promoting denser hydration products.

The presence of ettringite (Ca6Al2(SO4)3(OH)12·26 H2O), identified by peaks at 9.1°, 15.8°, 18°, 20.9°, and 22.9° 2θ, indicates early hydration of cement phases. Ettringite plays a significant role in providing initial strength and dimensional stability to the concrete matrix. Its consistent presence in rubberized concrete confirms that the incorporation of CR does not disrupt the hydration process but ensures sufficient early-age strength.

The peaks corresponding to alite (Ca3SiO₅), observed at 32.2°, 41.2°, 50.5°, 51.8°, and 52.1° 2θ, signify the retained cement clinker phases responsible for early-age strength development. The presence of ferrite (C4AF), with peaks at 11.2°, 30.3°, 35.3°, and 60.2° 2θ, contributes to the colour stability, workability, and secondary strength properties of the concrete. These phases are indicative of the robust hydration process that remains unaffected by the incorporation of SCMs and CR.

The inclusion of MSP introduces dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2), which is observed at 30.9°, 41.1°, and 50.3° 2θ. Dolomite enhances the microstructural stability and mechanical properties of rubberized concrete by acting as a filler material and participating in minor chemical stabilization processes. Similarly, the peaks corresponding to mullite (Al6Si2O13), detected at 16.4°, 26.2°, 40.8°, and 60.2° 2θ, originate from the FA content. Mullite, being an aluminosilicate phase, provides high-temperature resistance and contributes to long-term strength development.

CR, primarily composed of carbon and hydrogen, does not exhibit distinct crystalline peaks due to its amorphous polymeric structure. Instead, the XRD spectrum shows broad humps, indicative of the amorphous nature of rubber particles. The addition of CR introduces flexibility, energy absorption, and impact resistance to the concrete, compensating for any potential reduction in compressive strength caused by aggregate replacement. The inert and hydrophobic nature of CR modifies the hydration process, slightly reducing the intensity of certain crystalline phases while enhancing ductility and resistance to brittle [77,78].

The XRD analysis of rubberized concrete (R10S5M10F15) reveals clear microstructural variations compared to conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0). The introduction of SF, FA, and MSP enhances the pozzolanic activity, as evidenced by reduced portlandite peaks and an intensified amorphous C–S–H hump. Quantitatively, the relative intensity of the Ca(OH)2 peak at 18.1° 2θ in the modified mix was approximately 22–25% lower than that observed in the control mix, confirming partial consumption of portlandite due to pozzolanic reactions.

This intensity reduction is consistent with the reactive silica from FA and SF converting CH into additional C–S–H. Furthermore, the area under the broad hump between 29° and 32° 2θ, representing amorphous C–S–H, showed a visible increase in width and prominence, suggesting enhanced gel formation. These observations corroborate the hypothesis of microstructural densification and support the reduced porosity and improved durability of the R10S5M10F15 mix.

The incorporation of MSP increases the intensity of calcite and dolomite phases, contributing to the overall matrix densification and long-term stability. Additionally, the presence of mullite highlights the influence of FA in providing thermal stability and enhanced compressive strength. CR introduces a unique amorphous signature, reflecting its inert nature but significantly contributing to the flexibility and impact resistance of the material. These interpretations are based on relative peak intensity and phase evolution trends, and are further corroborated by the FTIR and EDS analyses presented in the following sections.

Overall, these microstructural variations demonstrate that the addition of SCMs and CR results in a well-integrated system with refined hydration products, reduced free portlandite, and enhanced durability. These findings confirm the suitability of rubberized concrete as a sustainable alternative to conventional concrete, with improved microstructural characteristics and performance attributes.

5.2 Chemical composition using FTIR

5.2.1 FTIR spectrum analysis of conventional concrete

The FTIR spectrum of conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0) provides a detailed analysis of the chemical bonds and functional groups within the hydrated cement matrix, as illustrated in Figure 7. The spectrum identifies key regions that correspond to the primary components of the concrete system, which include silicates, carbonates, and water.

FTIR pattern for conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0).

The absorption bands in the region between 450 and 700 cm−1 represent the bending vibrations of Si–O bonds, confirming the presence of silicate and aluminate phases within the concrete matrix. These phases arise primarily from the hydration of cement, forming Calcium Silicate Hydrate (C–S–H) and other aluminosilicate compounds. Silicates are essential for the microstructural development and mechanical strength of the concrete.

A strong absorption peak observed between 950 and 1,150 cm−1 corresponds to the Si–O–Si stretching vibrations, which are indicative of silicate networks. This peak is attributed to the polymerization of silicate chains within the C–S–H gel, formed during the hydration of tricalcium silicate (C3S) and dicalcium silicate (C2S). The intensity of this peak reflects the degree of hydration and the extent of bond formation within the cement matrix.

The peak at approximately 1,450 cm−1 is associated with C–O stretching vibrations, confirming the presence of calcium carbonate. This peak signifies the carbonation process, where portlandite (Ca(OH)2), a product of cement hydration, reacts with atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) to form calcite. The formation of calcite contributes to the densification of the microstructure but may also indicate early signs of carbonation-induced degradation, particularly near exposed surfaces.

The absorption band around 1,650 cm−1 corresponds to H–O–H bending vibrations, which arise from water molecules within the hydrated cement paste. This water exists as bound water within the structure of C–S–H and ettringite, indicating the hydration progress and the retained moisture within the concrete matrix.

Finally, the broad absorption band in the 3,000–3,500 cm−1 region corresponds to O–H stretching vibrations, reflecting the presence of free water and hydroxyl groups within the concrete. These peak highlights the capacity of the cementitious matrix to retain moisture, which is essential for ongoing hydration reactions. The broad nature of this peak signifies the presence of multiple hydrogen-bonded water species, including both chemisorbed and physiosorbed water.

The FTIR spectrum of conventional concrete provides a baseline characterization of its chemical structure, highlighting the contributions of silicates, carbonates, and water molecules to the hydration process and the microstructural development of the cementitious system.

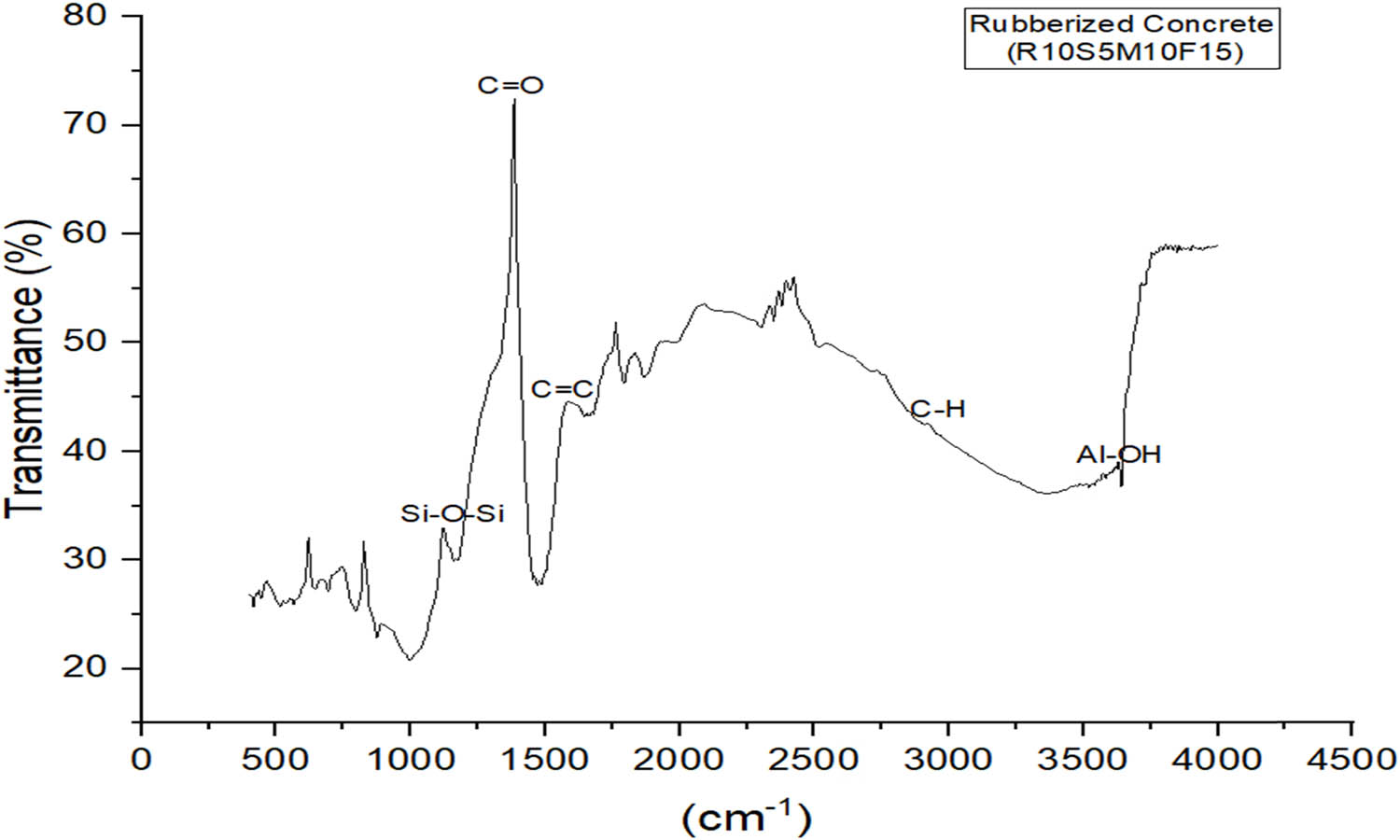

5.2.2 FTIR spectrum analysis of modified (rubberized) concrete

The FTIR spectrum of rubberized concrete (R10S5M10F15), incorporating CR (10%), SF (5%), MSP (10%), and FA (15%), presents significant variations compared to conventional concrete, as shown in Figure 8. These variations highlight the influence of SCMs and CR on the chemical composition and hydration mechanisms.

FTIR pattern for rubberized concrete (R10S5M10F15).

In the region between 450 and 700 cm−1, the spectrum exhibits bending vibrations of Si–O bonds, similar to those observed in conventional concrete. However, in rubberized concrete, this region is more pronounced due to the higher silicate content introduced by the pozzolanic materials such as SF and FA. The presence of these SCMs increases the availability of reactive silica, contributing to the formation of additional C–S–H through pozzolanic reactions. This enhancement refines the microstructure and improves the overall strength and durability of the concrete matrix.

The peak observed around 1,050 cm−1 corresponds to the Si–O–Si stretching vibrations, indicative of an extended and refined silicate network. While this peak is also prominent in conventional concrete, its intensity in rubberized concrete is higher due to the contribution of amorphous silica from SF and FA. The intensified Si–O–Si peak signifies an increased polymerization of silicate chains, which enhances the density and cohesiveness of the matrix, resulting in improved load-bearing capacity and resistance to environmental degradation.

A distinct peak near 1,450 cm−1 represents the C–O stretching vibrations, pointing to the presence of carbonate compounds such as calcium carbonate (CaCO3). This peak is more intense in rubberized concrete compared to conventional concrete, primarily due to the introduction of MSP, which contains calcium carbonate as its primary component. The carbonate content not only improves matrix densification but also enhances chemical stability, making rubberized concrete more resistant to aggressive environments such as carbonation and sulphate attack.

The absorption band at 1,640 cm−1 corresponds to C═C stretching vibrations, a unique feature attributed to the CR component. CR, being an organic polymer derived from tires, introduces carbon-carbon double bonds into the concrete matrix. These peak highlights the presence of rubber within the system, which contributes to the flexibility, ductility, and impact resistance of the modified concrete. These properties are critical in applications requiring increased energy absorption and resistance to brittle fracture.

A broad and pronounced peak around 3,400 cm−1 corresponds to O–H stretching vibrations, associated with hydroxyl groups and water molecules within the concrete matrix. Compared to conventional concrete, this peak in rubberized concrete is broader and more intense, reflecting the increased complexity of the matrix due to the introduction of SCMs and CR. The SCMs, particularly FA and SF, enhance the retention of bound water, which sustains long-term hydration and the formation of additional C–S–H. The presence of hydroxyl groups further supports the pozzolanic activity and microstructural refinement observed in rubberized concrete.

The FTIR spectrum comparison between conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0) and rubberized concrete (R10S5M10F15) highlights distinct microstructural variations caused by the incorporation of CR and SCMs.

In conventional concrete, the FTIR analysis identifies the primary phases such as silicates, carbonates, and water molecules, which are consistent with the typical hydration process. However, the spectrum of rubberized concrete demonstrates:

Increased Si–O–Si vibrations (1,050 cm−1) due to the enhanced silicate network formed by the pozzolanic reaction of SF and FA. This results in the development of additional C–S–H, which densifies the microstructure and improves mechanical strength.

Higher C–O vibrations (1,450 cm−1) caused by the introduction of MSP, reflecting the formation of calcium carbonate that contributes to matrix densification and chemical stability.

The unique C═C stretching vibrations (1,640 cm−1), indicative of the CR component, introduce polymeric flexibility into the system, compensating for the loss of rigidity from partial fine aggregate replacement and improving the ductility and impact resistance of the concrete.

A broader O–H stretching region (3,400 cm−1), demonstrating increased retention of hydroxyl groups and water molecules. This is attributed to the higher pozzolanic activity of SF and FA, which sustains hydration and generates additional C–S–H phases over time.

The observed differences in peak intensities and the presence of new functional groups highlight the improved microstructural properties of rubberized concrete compared to conventional concrete. While conventional concrete relies on primary hydration products such as C–S–H and portlandite, rubberized concrete benefits from Secondary hydration reactions facilitated by SF and FA, which refine the microstructure and also from filler effects of MSP, reducing voids and enhancing density. These microstructural variations not only enhance the mechanical strength and durability of rubberized concrete but also address specific performance requirements such as energy absorption, crack resistance, and chemical stability.

Thus, the FTIR analysis confirms that the increased Si–O–Si stretching intensity near 1,050 cm−1 in rubberized concrete arises not only from primary cement hydration, but also from secondary C–S–H formation through pozzolanic reactions of SF and FA. The reactive silica in these SCMs consumes calcium hydroxide, leading to additional silicate polymerization and microstructural densification. The subdued intensity of portlandite-associated bands (e.g., near 3,640 cm−1) further supports this consumption.

Simultaneously, the C–O peaks near 1,450–870 cm−1 reflect the presence of carbonate compounds primarily from MSP, contributing to filler effects and chemical stability. The broad O–H and H–O–H absorption bands (∼3,400 and 1,640 cm−1) indicate the retention of bound water and hydroxyl groups, essential for sustained hydration. Together, these features demonstrate that the combined action of SCMs and CR yields a chemically active and refined matrix, consistent with pozzolanic enhancement and improved hydration behaviour. The key functional groups, wavenumber assignments, and their corresponding implications are summarized in Table 7.

FTIR peak assignment and corresponding interpretation for R10S5M10F15 mix

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Bond/Functional group | Implication in cement matrix |

|---|---|---|

| ∼3,640 | O–H stretching (portlandite) | Presence of calcium hydroxide (CH); incomplete pozzolanic reaction |

| ∼3,420 | H–O–H bending (adsorbed water) | Moisture in gel pores and unbound water |

| ∼1,645 | H–O–H bending (molecular water) | Water retained in hydrated gel structures |

| ∼1,420–1,460 | C–O asymmetric stretching (carbonates) | Carbonation of CH due to atmospheric exposure |

| ∼980–1,000 | Si–O stretching (C–S–H gel) | Formation of calcium silicate hydrate – main strength phase |

| ∼875 | Out-of-plane bending of C–O | Minor calcite presence, indicative of surface carbonation |

| ∼712 | In-plane deformation of CO3 | Crystalline calcite (CaCO3) signature |

| ∼460–470 | Si–O bending (silicate network) | Polymerized silicate chains in hydrated matrix |

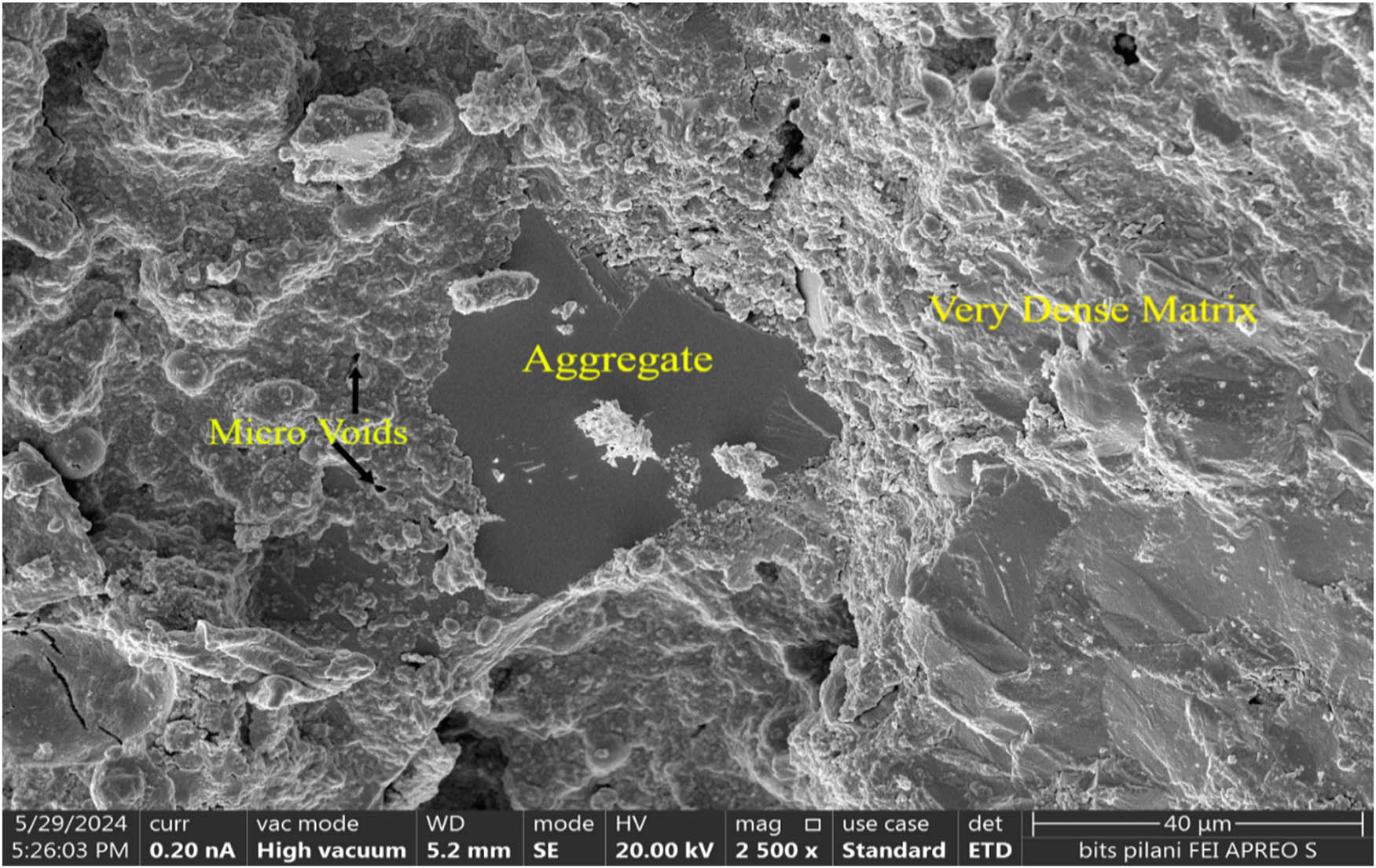

5.3 Microstructural analysis using FESEM

FESEM was employed to investigate the microstructural features and interfacial bonding of concrete mixes after 90 days of curing. Specimens approximately 10 mm × 10 mm × 5 mm in size were extracted from the central portions of the concrete cubes. These were intentionally fractured rather than polished to preserve the natural distribution of hydration products, internal porosity, and the ITZ characteristics. This preparation approach aligns with standard microscopy protocols for cement-based composites and minimizes surface distortion that could arise from mechanical abrasion.

Multiple zones across the matrix and ITZ were examined to capture representative microstructural features. The FESEM images of the control mix (R0S0M0F0) are presented in Figure 9 (2,500×) and Figure 10 (5,000×). The micrographs show loosely arranged hydration products interspersed with visible voids and interconnected microcracks ranging between 15 and 25 μm. These cracks are predominantly located along the ITZ, which appears weak and poorly compacted. The lack of binding gels and poor adhesion between paste and aggregate in this region indicate incomplete hydration, creating vulnerable paths for permeability and compromising long-term strength and durability.

FESEM micrographs of conventional mix (R0S0M0F0) at 2,500× magnification.

FESEM micrographs of conventional mix (R0S0M0F0) at 5,000× magnification.

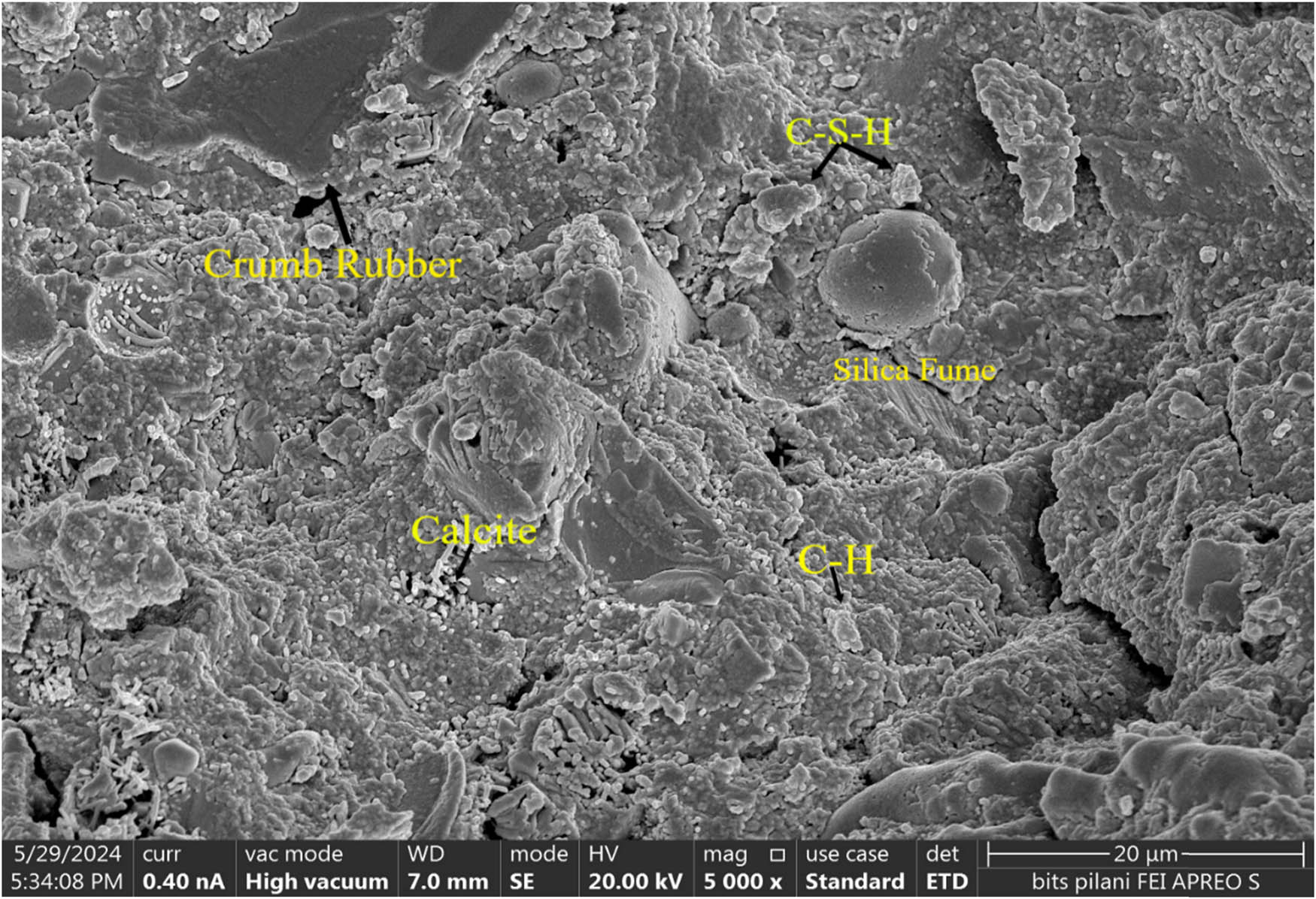

In comparison, the microstructure of the rubberized and SCM-modified mix (R10S5M10F15) exhibits notable densification and enhanced cohesion, as shown in Figure 11 (2,500×) and Figure 12 (5,000×). The inclusion of 10% CR introduces irregular particles with rough surfaces that mechanically interlock with the surrounding cement matrix. Although the chemical affinity between rubber and cement is inherently low, this partial physical interlocking, combined with the elastic nature of rubber, contributes to internal stress redistribution and limits crack propagation. These mechanisms align with earlier findings demonstrating energy absorption and crack-arresting behaviour in rubberized systems [79,80].

FESEM micrographs of Rubberized mix (R10S5M10F15) at 2,500× magnification.

FESEM micrographs of Rubberized mix (R10S5M10F15) at 5,000× magnification.

In the mix R10S5M0F0, the addition of 5% SF significantly improves microstructural quality. Its ultrafine particles fill capillary voids, leading to pore refinement and matrix densification [81]. The resulting structure displays narrower cracks and reduced porosity, directly contributing to increased durability and mechanical stability [82,83].

The incorporation of 10% MSP and 15% FA further enhances the matrix–aggregate interface and the overall compactness of the system. The marble slurry acts as a filler, reducing microvoids and contributing to a denser matrix, while FA, through pozzolanic reaction, refines the pore structure and forms additional C–S–H gels [84].

Comparative analysis between the control and modified mixes clearly illustrates the superior microstructural characteristics of the R10S5M10F15 mix. The control mix shows interconnected voids and a loosely packed ITZ, which provide pathways for fluid ingress and degrade durability, as mentioned by others [82]. In contrast, the modified mix features a well-bonded, homogenous microstructure with minimal cracking and a refined ITZ. The presence of CR aids in crack resistance through mechanical cushioning, while the synergistic action of SF, FA, and marble slurry promotes dense C–S–H formation, particle packing, and matrix cohesion.

Although direct porosity measurements were not performed in this study, FESEM micrographs clearly reveal fewer visible voids and a more cohesive matrix in the modified mix compared to the control. This morphological refinement is consistent with the broader amorphous C–S–H hump observed in XRD and the intensified silicate bonding seen in FTIR. These triangulated observations confirm that the combined action of SCMs and CR promotes microstructural densification and matrix continuity, effectively reducing porosity and enhancing durability.

The dense C–S–H phase, refined pore network, and improved ITZ observed in R10S5M10F15 create favourable conditions for long-term durability. Such features are known to enhance sulphate resistance and reduce vulnerability to freeze–thaw cycles. These observations are consistent with earlier studies reporting reduced sulphate-induced deterioration in SCM-enriched rubberized systems [54,85,86].

Despite the known limitations of CR, particularly its tendency to reduce compressive strength due to low stiffness and poor paste adhesion, the presence of SCMs in this mix compensates for such drawbacks. The 5% SF and 15% FA promote secondary C–S–H generation, while the MSP enhances particle packing. This combination results in a cohesive, crack-resistant structure capable of delivering strength levels comparable to control specimens.

Our earlier study [54] confirmed that R10S5M10F15 achieved compressive strength close to that of the control mix, while surpassing it in flexural strength and water resistance. The microstructural refinements described here directly underpin these performance trends. Similar conclusions have been drawn in other studies [86,87], which highlight the potential of well-designed SCM–rubber systems to balance ductility, durability, and mechanical resilience.

5.4 Elemental composition using EDS

EDS analysis was carried out using the X-MaxN model from OXFORD Instruments at BITS Pilani to determine the chemical elements present on the surface of fractured FESEM specimens. For each concrete sample, multiple zones were scanned across both the bulk matrix and interfacial transition areas. Fields of view were purposefully selected based on recurring microstructural features such as hydrated gel regions, pore boundaries, and reaction rims. Elemental mapping was performed on these representative regions to evaluate the spatial distribution of key components. This approach ensured that the data reflect consistent patterns across the specimen rather than isolated artefacts, enabling a reliable assessment of elemental homogeneity and its influence on concrete performance.

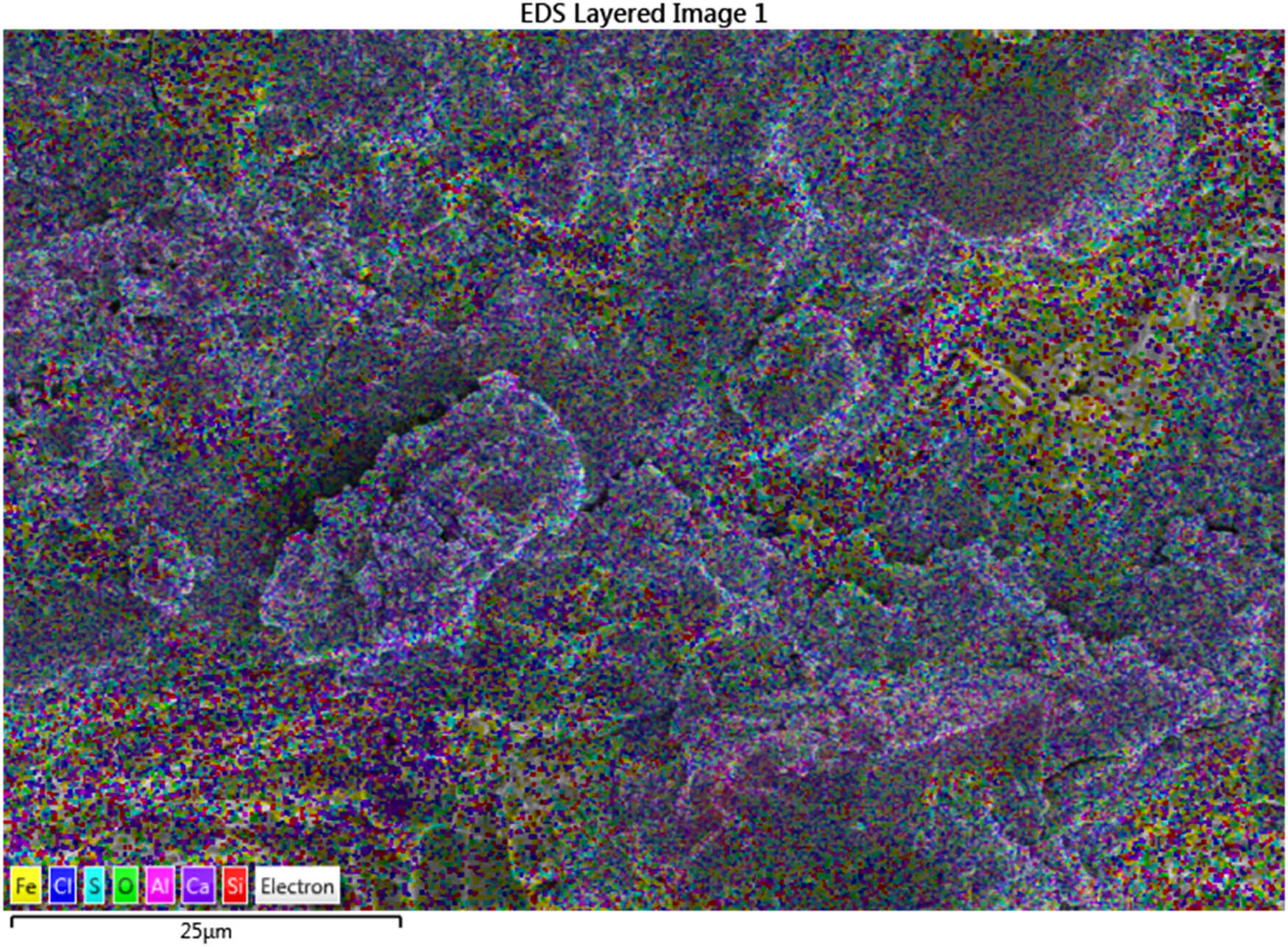

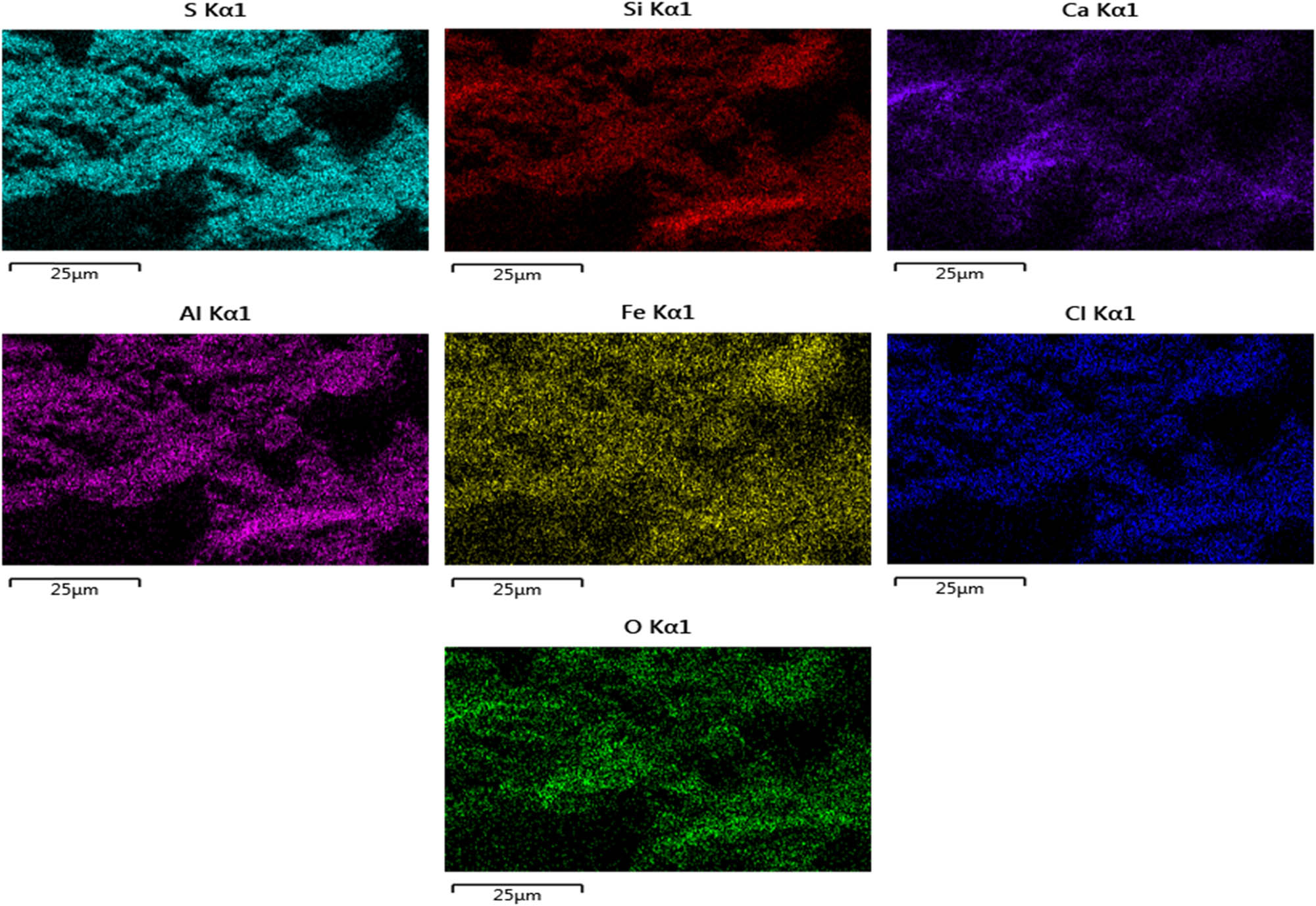

5.4.1 EDS analysis of conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0)

The energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis provides a detailed understanding of the elemental composition of conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0). The elemental composition of conventional concrete is summarized in Table 8. The primary elements detected include oxygen (30.91% by weight), calcium (29.37% by weight), silicon (14.51% by weight), and iron (14.19% by weight). These elements are crucial in forming the primary phases in concrete, such as C–S–H, which significantly contribute to the material’s strength and durability. The spatial distribution of these elements within the concrete matrix is depicted in Figure 13.

Elemental composition of conventional concrete

| Map sum spectrum | Weight (%) | Wt% sigma | Atomic (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| O | 30.91 | 1.46 | 50.81 |

| Al | 4.22 | 0.41 | 4.11 |

| Si | 14.51 | 0.53 | 13.58 |

| S | 6.33 | 0.81 | 5.19 |

| Cl | 0.47 | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| Ca | 29.37 | 0.80 | 19.27 |

| Fe | 14.19 | 0.87 | 6.68 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Spatial distribution of elements in conventional concrete.

The individual elemental maps shown in Figure 14 show widespread distribution of oxygen, reflecting its presence in various oxides and hydration products like C–S–H. Aluminium is localized, often associated with aluminosilicate phases, which contribute to the early strength development of the concrete. Silicon is uniformly distributed, highlighting its role in forming C–S–H and other silicate phases that enhance the concrete’s mechanical properties.

EDS elemental maps for conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0).

The sulphur map reveals areas of sulphate presence, participating in forming ettringite and influencing early-age properties. Chlorine is present in minor concentrations, which could impact durability by promoting chloride-induced corrosion. Calcium is abundantly present, crucial for forming calcium hydroxide and C–S–H, essential for the concrete’s strength and integrity. Iron’s distribution affects the colour, strength, and durability of the concrete. The combined EDS elemental map shows a comprehensive view of the spatial distribution of these key elements in the conventional concrete sample.

The high concentration of calcium, oxygen, and silicon in the conventional concrete emphasizes the dominance of hydration products like C–S–H, which are critical for its mechanical properties and durability. The presence of aluminium and sulphur, although in smaller quantities, indicates the formation of additional phases that contribute to the early strength and stability of the material. The detection of chlorine, even in minor amounts, necessitates consideration of potential durability issues related to chloride-induced corrosion.

The EDS spectrum of the conventional concrete, illustrated in Figure 15(a), shows the relative abundances of these elements. The prominent peaks for oxygen, calcium, silicon, and iron confirm their significant presence in the concrete matrix.

(a) EDS spectrum of conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0). (b) Backscattered electron image of conventional concrete.

Additionally, aluminium (4.22% by weight), sulphur (6.33% by weight), and minor amounts of chlorine (0.47% by weight) were also detected. Although present in smaller quantities, these elements play vital roles in the hydration process and the overall chemical stability of the concrete. The backscattered electron (BSE) image (Figure 15(b)) provides a detailed view of the microstructural features of the conventional concrete. The contrast in the BSE image helps differentiate between the various phases and the distribution of aggregate particles within the matrix.

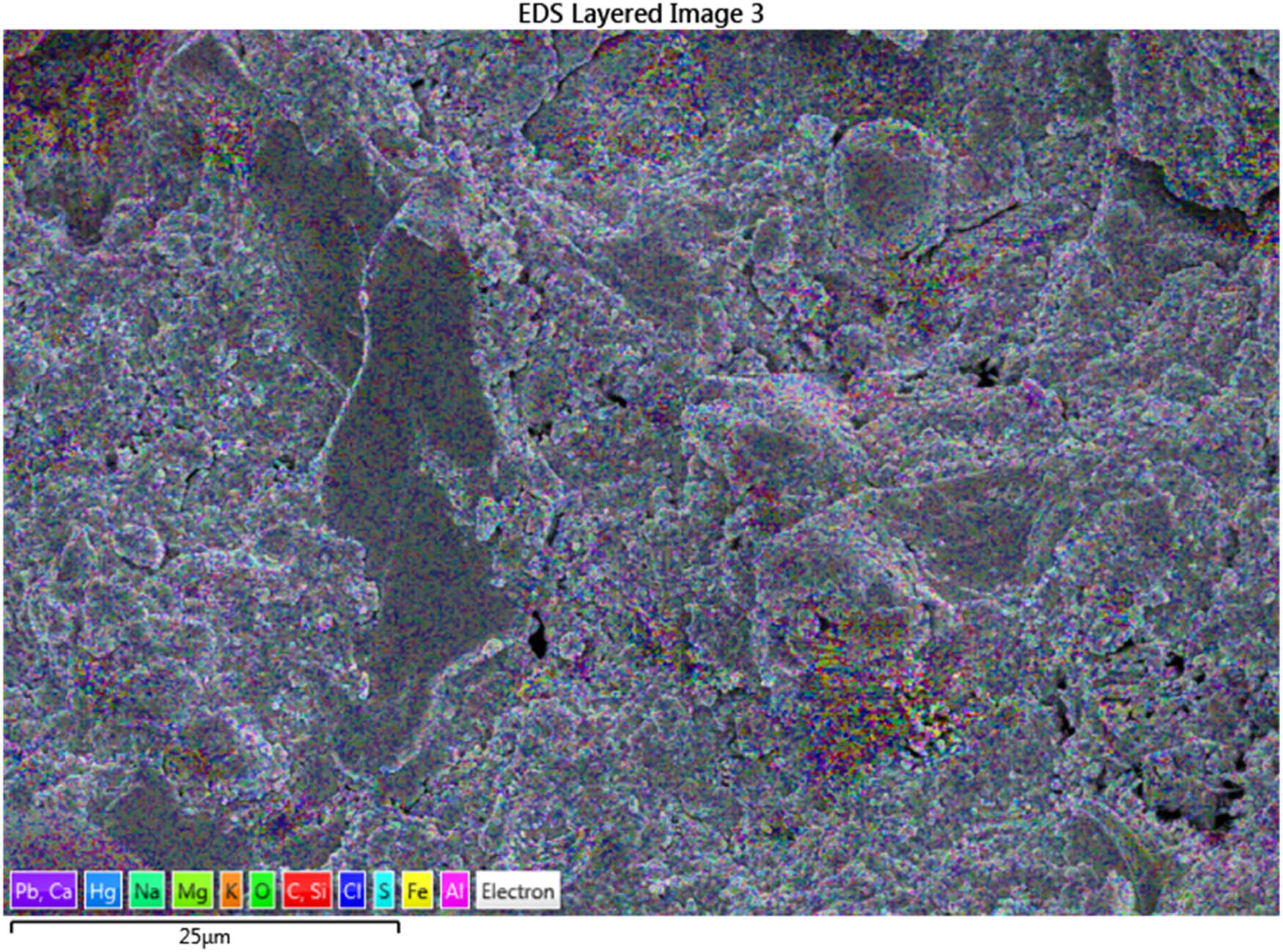

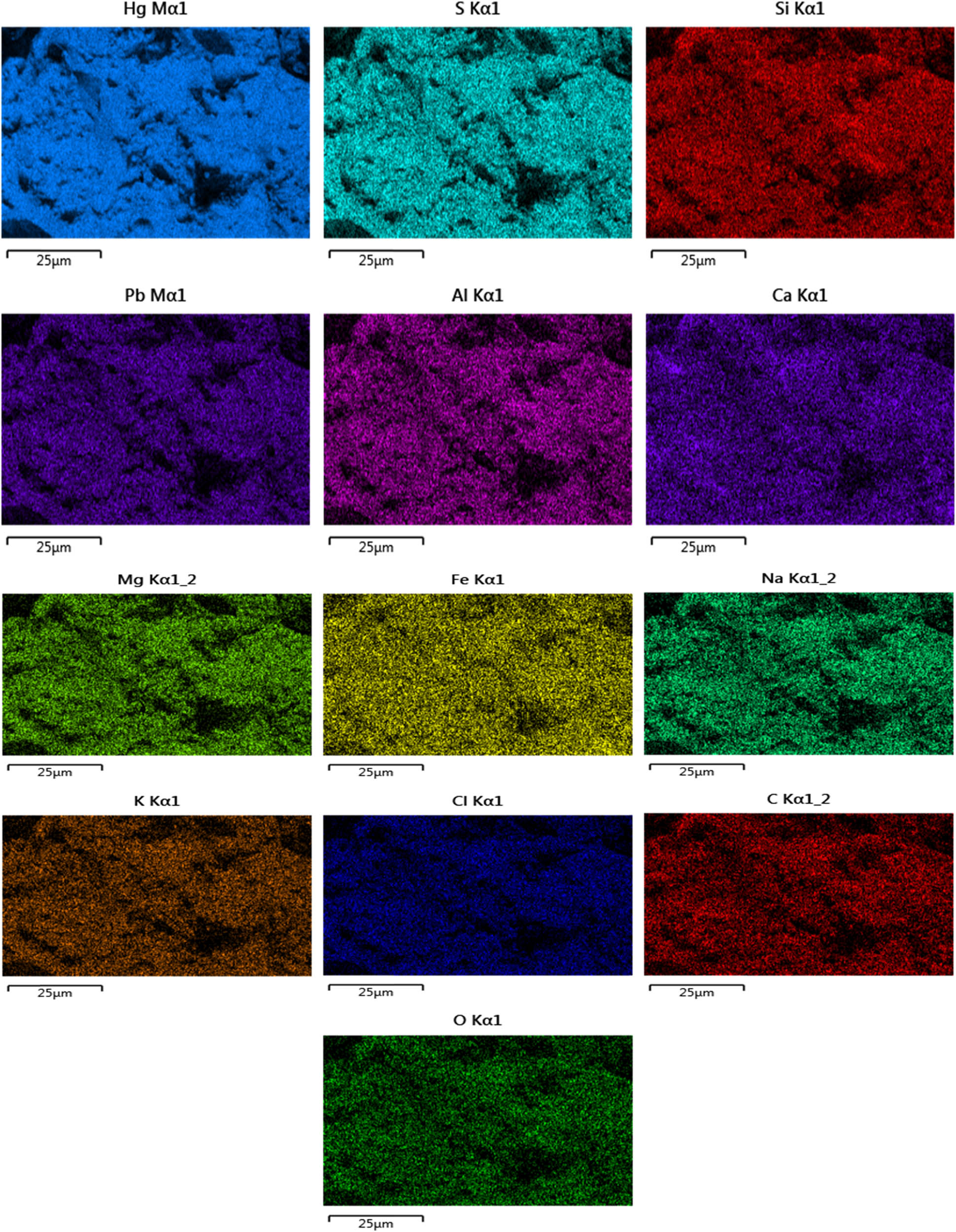

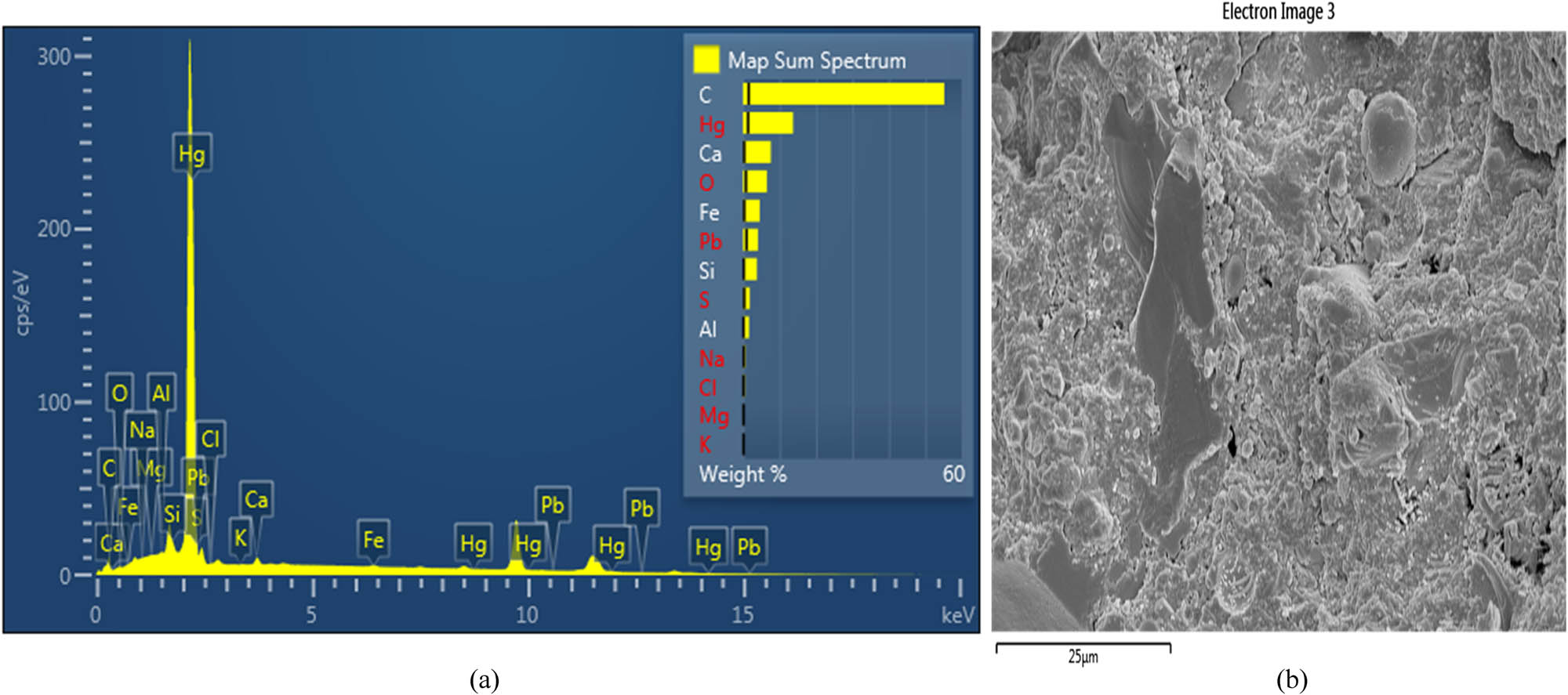

5.4.2 EDS analysis of rubberized concrete (R10S5M10F15)

The energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis provides a comprehensive understanding of the elemental composition of rubberized concrete (R10S5M10F15).

The elemental composition of rubberized concrete is summarized in Table 9. The primary elements detected include carbon (55.24% by weight), oxygen (6.50% by weight), calcium (7.59% by weight), and iron (4.50% by weight). The significant presence of carbon is primarily due to the inclusion of CR, which consists mainly of carbon-based polymers. This high carbon content enhances the concrete’s elasticity, toughness, and resistance to crack propagation. Figure 16 shows the spatial distribution of these elements within the concrete matrix.

Elemental composition of rubberized concrete

| Map sum spectrum | Weight (%) | Wt% sigma | Atomic (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 55.24 | 1.53 | 81.28 |

| O | 6.50 | 0.76 | 7.19 |

| Na | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.44 |

| Mg | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.11 |

| Al | 1.58 | 0.13 | 1.03 |

| Si | 3.73 | 0.17 | 2.35 |

| S | 1.83 | 0.29 | 1.01 |

| Cl | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.23 |

| K | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| Ca | 7.59 | 0.27 | 3.35 |

| Fe | 4.50 | 0.31 | 1.42 |

| Hg | 13.70 | 1.37 | 1.21 |

| Pb | 4.06 | 0.94 | 0.35 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Spatial distribution of elements in rubberized concrete.

The EDS spectrum of the rubberized concrete, illustrated in Figure 18(a), shows the relative abundances of these elements. The BSE image (Figure 18(b)) provides a detailed view of the microstructural features of the rubberized concrete. The prominent peak for carbon confirms its significant presence in the concrete matrix. Additionally, smaller amounts of sodium (0.58% by weight), magnesium (0.15% by weight), aluminium (1.58% by weight), silicon (3.73% by weight), sulphur (1.83% by weight), chlorine (0.46% by weight), mercury (13.70% by weight), and lead (4.06% by weight) were also detected. These elements, although present in smaller quantities, play vital roles in the overall chemical stability and properties of the concrete.

The development of concrete strength is significantly influenced by the calcium-to-silicon (Ca/Si) ratio. The EDS analysis revealed a Ca/Si ratio of 2.024 for traditional concrete, whereas rubberized concrete exhibited a slightly higher ratio of 2.034. This near-equal Ca/Si ratio correlates positively with the comparable compressive strength observed in both concrete types. These findings are consistent with the results reported by [23,88,89].

The inclusion of SCMs is anticipated to augment the hydration process and the creation of C–S–H, hence enhancing the microstructure and mechanical characteristics.

The EDS elemental maps (Figure 17) provide a comprehensive view of the spatial distribution of these key elements within the rubberized concrete sample. The carbon map indicates widespread distribution, reflecting the significant presence of CR in the matrix, which contributes to improved elasticity and crack resistance.

EDS elemental maps for rubberized concrete (R10S5M10F15).

Oxygen shows its presence in various oxides and hydration products like C–S–H and calcium hydroxide, essential for the concrete’s strength and durability. Sodium and magnesium, though present in minor amounts, are distributed throughout the matrix and can influence the setting time and early strength development. Aluminium shows localized concentrations, associated with aluminosilicate phases, enhancing early strength development and present in FA. Silicon, uniformly distributed, plays a crucial role in forming additional silicate phases, enhancing mechanical properties, and stemming from both SF and FA. Sulphur reveals areas of sulphate presence, influencing early-age properties by forming ettringite.

Chlorine, present in minor concentrations, impacts durability by promoting chloride-induced corrosion. Calcium is crucial for forming calcium hydroxide and additional silicate hydrates, reflecting its abundant presence in cement and supplementary materials like MSP. Iron affects colour, strength, and durability, often present in FA, contributing to structural properties. Mercury and lead, though concerning, highlight the need for careful monitoring and treatment of recycled materials due to their potential environmental and health impacts.

The energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis provides further insight into the elemental composition and distribution of phases, reflecting the microstructural differences between conventional and modified concrete mixes.

In conventional concrete (R0S0M0F0), the EDS results, as summarized in Table 8 and illustrated in Figures 13–15, confirm a composition dominated by calcium (29.37%), oxygen (30.91%), silicon (14.51%), and iron (14.19%). These elements are integral to the formation of hydration products such as C–S–H and portlandite. However, the relatively high concentration of calcium, coupled with localized voids observed in FESEM, indicates incomplete hydration and a lower degree of matrix densification. The spatial mapping of silicon and oxygen shows their uniform presence in the matrix, yet the absence of finer silicate phases highlights a lack of pozzolanic activity.

On the other hand, the modified rubberized concrete (R10S5M10F15) demonstrates significant variations in elemental composition, as shown in Table 9 and Figures 16–18. The EDS results highlight a higher carbon content (55.24%), reflecting the inclusion of CR. The carbon distribution map indicates uniform dispersion of rubber particles, which contribute to improved toughness, crack resistance, and flexibility. Additionally, the presence of silicon (3.73%) and aluminium (1.58%) confirms the influence of FA and SF, which introduce secondary C–S–H phases through pozzolanic reactions. This results in a more refined microstructure and improved bond strength at the ITZ.

(a) EDS spectrum of rubberized concrete (R10S5M10F15). (b) Backscattered electron image of rubberized concrete.

The calcium-to-silicon (Ca/Si) ratio in conventional concrete is 2.024, while in modified rubberized concrete, it remains comparable at 2.034. This near-identical ratio indicates that the primary hydration process remains intact in the modified mix. However, the improved matrix densification in rubberized concrete is attributed to the additional pozzolanic reactions and the filler effect of MSP, which reduces voids and enhances the overall cohesiveness of the matrix [88].

The EDS maps for modified concrete also reveal the presence of sulphur (1.83%), which contributes to the formation of ettringite during hydration, and trace elements such as chlorine (0.46%). While chlorine levels remain low, they highlight the need for monitoring to ensure long-term durability against chloride-induced corrosion. The detection of mercury (13.70%) and lead (4.06%) emphasizes the importance of quality control when using recycled materials like CR to avoid potential environmental risks.

EDS analysis reveals that conventional concrete relies predominantly on hydration products with limited refinement, while the modified mix benefits from enhanced pozzolanic activity, a more uniform elemental distribution, and improved matrix densification. The inclusion of CR introduces high carbon content, contributing to improved toughness and crack resistance, while the contributions of SF, FA, and MSP densify the microstructure and refine the ITZ. SCM-rich mixes demonstrated reduced porosity and improved densification, making them suitable for high-durability applications. CR’s flexibility makes it ideal for non-structural applications, where energy absorption is critical. Additional elemental analyses conducted at the SAIF/CRNTS, IIT Bombay, further validated and corroborated these findings.

6 Conclusions

This study provided a comprehensive morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating CR, SF, MSP, and FA. Advanced characterization techniques, including XRD, FTIR, FESEM, and EDS, were employed to elucidate the internal structural transformations and to correlate these with previously validated improvements in mechanical and durability performance.

The modified concrete mix demonstrated significantly enhanced hydration behaviour, as evidenced by the intensified amorphous C–S–H gel formation and an approximately 22–25% reduction in the intensity of portlandite peaks on XRD analysis. This confirmed the active pozzolanic reactivity of SF and FA in transforming calcium hydroxide into strength-giving hydration products.

FESEM observations revealed a dense, crack-free matrix with a markedly refined ITZ. The matrix surrounding aggregates and CR particles appeared more cohesive and compact, with fewer visible microvoids, indicating improved microstructural integrity and reduced permeability.

MSP contributed effectively as a filler, promoting calcite and dolomite formation that enhanced the overall densification and stability of the cementitious matrix. Although CR, due to its non-polar and inert nature, slightly diminished the bond strength at the matrix interface, it significantly enhanced the energy absorption and crack resistance of the composite, resulting in a balanced mechanical response.

EDS mapping confirmed a uniform distribution of calcium and silica elements within the matrix, demonstrating the homogeneous dispersion of hydration products and the chemical stability conferred by SCM integration. The Ca/Si ratio remained within optimal bounds, aligning well with durability and strength expectations.

This study builds upon previously established mechanical and durability performance [54] to reaffirm the promise of hybrid CR–SCM concrete systems as viable and sustainable alternatives for modern infrastructure. The R10S5M10F15 mix demonstrated superior morphological refinement, enhanced matrix integrity, and notable improvements in durability, all of which are essential for ensuring long-term structural reliability. These improvements, resulting from the synergistic incorporation of recycled and industrial byproduct materials, reflect both technical soundness and practical relevance in the context of sustainable construction. The combined insights from both performance and microstructural perspectives offer a solid foundation for the wider implementation and codification of such systems in real-world applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Department of Civil Engineering, Maulana Azad National Institute of Technology, Bhopal, for providing the core experimental facilities and academic environment essential for conducting the research work during the Ph.D. The authors also acknowledge the support of other departments within MANIT for enabling access to advanced material characterization tools such as XRD and FTIR. Further, the authors sincerely thank Punjab Engineering College (Deemed to be University), Chandigarh, for supporting the refinement and preparation of the manuscript. The assistance provided by the Sophisticated Instrumentation Facility at BITS Pilani and the Sophisticated Analytical Instrument Facility at IIT Bombay is sincerely appreciated. Heartfelt thanks are extended to family members for their continuous encouragement throughout the research journey.

-

Funding information: The authors state no funding involved.

-

Author contributions: Karan Moolchandani: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. Abhay Sharma: supervision, validation, resources, and reviewing the manuscript. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency. Trend in global CO2 emissions: 2015 Report [Internet], PBL, The Hague, 2015. [cited 2025 Dec 4] https://www.pbl.nl/uploads/default/downloads/pbl-2015-trends-in-global-co2-emisions_2015-report_01803_4.pdf.Search in Google Scholar

[2] International Energy Agency. Technology roadmap – Low-carbon transition in the cement industry [Internet], IEA, Paris, 2018. [cited 2025 Dec 4] https://www.iea.org/reports/technology-roadmap-low-carbon-transition-in-the-cement-industry.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Lehner, P. and K. Hrabová. Evaluation of degradation and mechanical parameters and sustainability indicators of zeolite concretes. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 371, 2023, id. 130791.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130791Search in Google Scholar

[4] Mostafaei, H., B. Badarloo, N. F. Chamasemani, M. A. Rostampour, and P. Lehner. Investigating the effects of concrete mix design on the environmental impacts of reinforced concrete structures. Buildings, Vol. 13, No. 5, 2023, id. 1313.10.3390/buildings13051313Search in Google Scholar

[5] Santhanam, M., S. Jain, and S. Bhattacherjee. Versatile concrete with limestone calcined clay cement. Indian Concrete Journal, Vol. 97, 2023, pp. 7–17.Search in Google Scholar

[6] Xiong, G., S. Al-Deen, X. Guan, Q. Qin, and C. Zhang. Economic and environmental benefit analysis between crumb rubber concrete and ordinary Portland cement concrete. Sustainability, Vol. 16, No. 11, 2024, id. 4758.10.3390/su16114758Search in Google Scholar

[7] Zhu, X. and Z. Jiang. Reuse of waste rubber in pervious concrete: experiment and DEM simulation. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 71, 2023, id. 106452.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106452Search in Google Scholar

[8] Contec. Tire waste statistics: All you need to know [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Jun 11]. https://contec.tech/tire-waste-statistics-need-to-know/.Search in Google Scholar

[9] Wang, K., T. Shan, B. Li, Y. Zheng, H. Xu, C. Wang, et al. Study on pyrolysis characteristics, kinetics and thermodynamics of waste tires catalytic pyrolysis with low-cost catalysts. Fuel, Vol. 356, 2024, id. 129644.10.1016/j.fuel.2023.129644Search in Google Scholar

[10] Material Recycling Association of India. Rubber & tyre [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 23]. https://mrai.org.in/theindustry/rubber.html.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Hu, Y., X. Yu, J. Ren, Z. Zeng, and Q. Qian. Waste tire valorization: Advanced technologies, process simulation, system optimization, and sustainability. Science of the Total Environment, Vol. 942, 2024, id. 173561.10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173561Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[12] Ahmed, I. Laboratory study on properties of rubber-soils. Publication FHWA/IN/JHRP-93/04, Joint Highway Research Project, Indiana Department of Transportation and Purdue University, West Lafayette (IN), 1993.Search in Google Scholar

[13] Fareghian, M., M. Afrazi, and A. Fakhimi. Soil reinforcement by waste tire textile fibers: small-scale experimental tests. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 35, No. 2, 2023, id. 04022402. 10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0004574Search in Google Scholar

[14] Ge, J., G. Mubiana, X. Gao, Y. Xiao, and S. Du. Research on static mechanical properties of high-performance rubber concrete. Frontiers in Materials, Vol. 11, 2024, Article 1426979.10.3389/fmats.2024.1426979Search in Google Scholar

[15] Raut, A. N., M. Adamu, R. J. Singh, Y. E. Ibrahim, A. L. Murmu, O. S. Ahmed, et al. Investigating crumb rubber-modified geopolymer composites derived from steel slag for enhanced thermal performance. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal, Vol. 59, 2024, id. 101880.10.1016/j.jestch.2024.101880Search in Google Scholar

[16] Janga, S., A. N. Raut, M. Adamu, Y. E. Ibrahim, and M. Albuaymi. Multi-response optimization of thermally efficient RC-based geopolymer binder using response surface methodology approach. Developments in the Built Environment, Vol. 19, 2024, id. 100528.10.1016/j.dibe.2024.100528Search in Google Scholar

[17] Chilukuri, S. K., A. N. Raut, S. Kumar, R. J. Singh, and V. Sakhare. Enhancing thermal performance and energy efficiency: optimal selection of steel slag crumb rubber blocks through multi-criteria decision making. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 409, 2023, id. 134094.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134094Search in Google Scholar