Abstract

The development of magnesium oxide (MgO), magnesium oxide concrete, and magnesium oxide concrete dams in China has experienced more than 40 years. So far, more than 60 MgO concrete dams have been built in China, creating significant economic and social benefits. In order to promote the continuous progress of MgO concrete dam construction technology, this study focuses on the effects of the calcination system on MgO activity. The delayed micro-expansion characteristics of MgO concrete significantly differ from non-MgO concrete. The temperature control measures of MgO concrete dams significantly differ from non-MgO concrete dams and the uniformity of MgO distribution in concrete and points out that the calcination system of magnesite determines the MgO activity. The MgO activity determines the expansion performance of MgO concrete, and the expansion performance of MgO concrete determines the temperature control measures of the MgO concrete dam. MgO concrete dam construction technology is worth popularization and application.

1 Introduction

In the early 1980s, the beneficial effects of magnesium oxide (MgO) were accidentally discovered at the Baishan Dam in Jilin Province, China. Since then, engineers and researchers have carried out a large number of studies on MgO, MgO concrete, and MgO concrete dams using a combination of micro and macro research methods. From MgO production, MgO concrete design to MgO concrete dam construction, a set of complete and standardized MgO concrete dam construction technologies has been formed. This technology has been used to build more than 60 MgO concrete dams in China, creating significant economic and social benefits [1,2,3,4,5]. In order to promote the continuous progress of concrete dam construction technology, it is necessary to timely summarize the influencing factors of MgO quality, the difference between MgO concrete and non-MgO concrete, and the difference between MgO concrete dam and non-MgO concrete dam, but there are few reports in this regard. Therefore, this study has been carried out in this work.

2 Magnesium oxide

The main raw material of MgO is magnesite. After the magnesite is calcined at high temperatures, a white powder of MgO is obtained, and its density is 2.9–3.5 g·cm−3. The calcination temperature of weighty calcined MgO is more than 1,600°C, and it is mainly used as a refractory material. The calcination temperature of light calcined MgO is less than 1,100°C, and it is widely used in building materials, agriculture, and the chemical industry. The specific surface area of MgO decreases with the increase of calcination temperature and is about 450–550 m2·kg−1, which is 1.1–1.8 times the specific surface area of cement. As early as 1980, Metha et al. [6] pointed out that MgO powder with a particle size of 300–1,180 μm obtained by careful calcination (at temperatures of 900–950°C) had the potential to be used as expansive agents for compensating thermal shrinkage and thus prevent cracks in mass concrete due to thermal stresses. However, this type of MgO was not produced industrially and applied in mass concrete. MgO is widely used as an expansion agent in the concrete of actual projects, which is gradually realized by scientific and technical personnel after realizing why there were no cracks in the Baishan Arch Dam.

Baishan Arch Dam is located in the upper reaches of the Songhua River, Jilin Province, China. The construction was started in May 1976 and water was stored under the sluice in November 1982. The maximum height of the dam was 149.50 m, and the total concrete used was about 260 × 104 m3. More than 60% of the concrete of the dam was poured in the summer, and the temperature difference in the foundation was more than 40°C, but no penetrating cracks in the foundation were found during the dam inspection before water storage, and no water seepage occurred after many years of dam operation. From the prototype observation data of the Baishan Arch Dam, it was found that the autogenous volume expansion of concrete during the cooling stage counteracted the volume contraction generated during the cooling process and inhibited the crack formation in the dam. After studying the Fushun dam cement used in the Baishan Arch Dam, Yuan and Mingshu [7] pointed out that Fushun dam cement with MgO content as high as 4.72% was the reason for autogenous volume expansion of Baishan Arch Dam concrete. Inspired by the autogenous volume expansion of Baishan Arch Dam concrete, a vast number of scientific and technical personnel began to develop the MgO expansion agent and its concrete.

The study of magnesium oxide mainly focuses on the study of the calcination system of magnesite. A large number of studies have shown that the calcination temperature and time of magnesite determine the hydration reaction capacity of MgO [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. The hydration reaction capacity of MgO refers to the activity of MgO, which is expressed by the activity index. The higher the activity index of MgO, the lower its hydration reaction capacity. The Chinese standard stipulates that the activity of MgO is evaluated by citric acid neutralization [17]. Figure 1 shows the morphology of highly active MgO (R-MgO), moderately active MgO (M-MgO), and low-active MgO (S-MgO) [18]. From Figure 1, it can be seen that a MgO particle consists of a large number of MgO grains, whose size is highly correlated with its activity. MgO with lower activity has a larger grain size due to its higher calcination temperatures [14].

![Figure 1

Morphology of MEA particles with different reactivities: (a) R-MgO, (b) M-MgO, and (c) S-MgO [18].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0094/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0094_fig_001.jpg)

Morphology of MEA particles with different reactivities: (a) R-MgO, (b) M-MgO, and (c) S-MgO [18].

In 1991, Zheng et al. [8] pointed out through a large number of experimental studies that the expansion rate and amount of MgO could be changed by adjusting the calcination temperature and time of magnesite so that the concrete mixed with the special MgO has delayed expansion characteristics. Later studies showed that with the increase of calcination temperature and the extension of calcination time, the grain size of MgO increased, the lattice distortion decreased, the specific surface area decreased, the density increased, and the hydration reaction capacity decreased [14,19]. Particularly when the calcination temperature exceeds 1,000°C, the hydration reaction ability of MgO decreases (Figure 2) [15]. Moreover, compared with MgO with a small activity index, MgO with a large activity index has larger expansion energy, slower expansion, and smaller expansion amount in the early stage, larger expansion amount in the later stage, and longer time for expansion stability, which has a better compensation effect on concrete shrinkage in the later stage [14,16]. After a lot of experimental research and engineering practice, the Chinese scientific and technological personnel finally determined that the calcination temperature of MgO for dam concrete is 1,000–1,100°C, the high temperature lasts for half an hour, and the activity index of the corresponding MgO is 200–280 s. This has been written into the relevant specifications of MgO for hydraulic concrete in China [17,20,21].

![Figure 2

The hydration degree of MgO (particle size: 150–300 μm) prepared at different calcination temperatures varies with age [15].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0094/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0094_fig_002.jpg)

The hydration degree of MgO (particle size: 150–300 μm) prepared at different calcination temperatures varies with age [15].

In China, proven magnesite reserves are 3.1 billion tons, accounting for about one-third of the world's total proven reserves, but mainly concentrated in Liaoning province [22]. Obviously, this will increase the transportation cost of building MgO concrete dams in the vast territory of China. Therefore, scientific and technological personnel have begun to study new raw materials and production processes for the production of MgO expansion agents and even develop new delayed expansion agents suitable for dam concrete. For example, dolomite is used as a raw material to produce MgO [23,24], low-grade magnesite is used to produce MgO [25,26], calcium oxide and magnesium oxide are used to make a calcium-magnesium compound expansive agent [27,28,29,30,31], MgO is produced by cement rotary kiln with pre-decomposition system [32], and so on. Yet, the exploration of more accessible and economical raw materials and simpler processes is still a topic worthy of further research in the future.

3 Magnesium oxide concrete

Magnesium oxide concrete is a material with delayed expansion, strength, and durability formed by mixing special MgO with cement, sand, gravel, fly ash, water, and other raw materials used to produce concrete in a certain proportion after mixing and hardening. The amount of MgO added is calculated as a percentage of the total amount of cementitious materials used in concrete, and MgO itself is not included in the total amount of cementitious materials. The design method of the MgO concrete mix is the same as that of ordinary concrete. A large number of experimental studies and engineering practices show that the mechanical properties and durability of MgO concrete are not reduced and even improved compared with the concrete without MgO under the same conditions [33,34,35,36,37,38]. The significant difference between MgO concrete and unmixed MgO concrete is that MgO concrete has good delayed micro-expansion characteristics. This expansion performance of MgO concrete, on the one hand, is controlled by the activity of MgO products at the front end; on the other hand, it affects the temperature control measures of the MgO concrete dam at the back end. Therefore, engineers and technicians pay special attention to the expansion performance of MgO concrete, the balanced content of MgO in concrete, and the mathematical model of long-term deformation of MgO concrete.

3.1 Expansion performance of magnesium oxide concrete

It is well known that, in the hardening process of ordinary concrete, the autogenous volume deformation only caused by the hydration of the cementing material is generally contracted [39,40,41]. However, a large number of experimental studies show that concrete exhibits good delayed micro-expansion characteristics after the special MgO is added to concrete [42,43,44]. This characteristic is determined by the activity of MgO [40,43,45,46]. This expansion deformation matches with the long temperature drop process of dam concrete, which can compensate for the volume shrinkage of dam concrete during the long temperature drop process so as to improve the crack resistance of dam concrete [47–50]. In addition, within the range of MgO balanced content, the long-term expansion deformation of concrete is stable [51,52]. Because the hydration product of MgO is only Mg(OH)2, it is a very simple and stable crystal that does not dehydrate unless the temperature increases to 350°C, which makes MgO a safe expansion agent [53]. After adding low activity MgO to concrete, the concrete expansion rate is slow and the expansion amount is small in the early stage, and the expansion amount is large in the later stage, and the expansion stability takes a long time. With the addition of highly active MgO, the early expansion is fast, and the expansion amount is large. The late expansion amount is small, and the time required for expansion stability is shorter. After adding MgO with an activity index of 200–280 s into the concrete, the expansion deformation of concrete is mainly concentrated in the age of 90–360 days, and the expansion deformation tends to be stable after 360–540 days, which would neither expand indefinitely nor retract. These excellent properties of MgO concrete, especially the delayed micro-expansion characteristics, are the key reasons why MgO concrete has attracted great attention from peers and has been rapidly promoted and applied. Figure 3 [4] and Figure 4 [54], respectively, show the typical autogenous volume deformation process of concrete and the autogenous volume deformation curves of MgO concrete at different curing temperatures, which show that the expansion of MgO concrete increases with the increase of MgO content or the increase of ambient temperature. Taking age 1 as an example, under the same conditions, in general, the expansion deformation increases by about 10 × 10−6–20 × 10−6 with each 1% increase in MgO content, or the expansion deformation increases by about 30 × 10−6–40 × 10−6 with each 10°C increase in the ambient temperature. Since the aggregate in the concrete does not expand, the expansion of MgO content is essentially the volume expansion of the cement slurry, and the aggregate plays a constraint role in the expansion of the cement slurry. The larger the aggregate volume, the smaller the expansion of the concrete. The research of Deng et al. [55] shows that the expansion of MgO cement slurry originates from the formation and development of Mg(OH)2 crystals; the expansion amount depends on the location, morphology, and size of Mg(OH)2 crystals, and the expansion energy comes from the water absorption swelling force and crystal growth pressure of Mg(OH)2 crystals. In the early stage of hydration, Mg(OH)2 crystals are very small, and the main driving force of slurry expansion is the water absorption swelling. At the later stage of hydration, with the growth of Mg(OH)2 crystals, the crystal growth pressure becomes the main driving force of expansion. According to Chatterji [27], more Mg2+ is generated near the surface of MgO in a short time at a higher curing temperature, which induces a larger supersaturation and thus increases the crystal growth pressure. This reveals the expansion mechanism of MgO concrete and lays a reliable scientific foundation for the application of MgO concrete in engineering.

![Figure 3

Typical autogenous volume deformation curves of concrete [4].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0094/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0094_fig_003.jpg)

Typical autogenous volume deformation curves of concrete [4].

![Figure 4

Autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete at different curing temperatures [54].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0094/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0094_fig_004.jpg)

Autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete at different curing temperatures [54].

3.2 Soundness content of MgO in concrete

As mentioned above, the expansion deformation of MgO concrete is stable within the range of balanced MgO content. Therefore, determining the balanced MgO content in concrete is crucial.

The balanced MgO content in concrete refers to the content of MgO corresponding to the maximum expansion caused by MgO that hardened concrete can withstand. Obviously, the less expansion the concrete can withstand, the less MgO should be added to the concrete. In the range of appropriate MgO content, the expansion of MgO is helpful in reducing the pore diameter and total pore volume of concrete, optimizing the microstructure of concrete, and improving the mechanical properties and durability of concrete [38]. However, when the MgO content exceeds a certain value, the expansion caused by MgO will destroy the interface between the cement matrix and aggregate and affect the mechanical properties and durability of concrete [56]. Some engineering cases [57,58] show that the high content of MgO in cement results in damage to concrete structures. The domestic and foreign cement product standards consider MgO to be a harmful component of cement and strictly control the MgO content of cement not to exceed 5% (if the cement autoclave soundness test is qualified, it can be relaxed to 6%) [20,21,58–62], which is based on the volume stability of concrete itself to make the provisions. The balanced MgO content in concrete was determined initially by the cement paste autoclave method [63]; that is, the cement paste specimens with sizes of 25 mm × 25 mm × 280 mm were put into an autoclave vessel at a temperature of 215.7°C ± 1.3°C for 3 h. The MgO amount corresponding to the autoclave expansion rate of the specimen of 0.5% was taken as the balanced MgO content in concrete. Obviously, there is a large difference between the cement paste sample and MgO concrete and its real expansion, so the balanced MgO content determined by this is too harsh. Therefore, the cement mortar autoclave method [1], the one-graded concrete autoclave method [64], the simulated cement paste autoclave method [65], and the simulated mortar autoclave method [66] were later proposed. The autoclave temperature of these methods was 215.7°C ± 1.3°C, and the autoclave time was 3 h. The differences between the various methods are shown in Table 1. As can be seen from Table 1, the balanced MgO content determined by the method of cement paste autoclave, cement mortar autoclave, one graded concrete autoclave, simulated cement paste autoclave, and simulated mortar autoclave increases in turn. In addition, the MgO balanced content in concrete determined by the simulated mortar autoclave method, simulated cement paste autoclave method, and one graded concrete autoclave method can reach 6.5–7.5%, but the MgO balanced content in concrete determined by other methods is difficult to exceed 6%.

Comparison of methods used to determine the balanced MgO content in concrete

| Determination method | Specimen material | Specimen size (mm × mm × mm) | Determination criteria | Balanced MgO content | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement paste autoclave method | Cement paste | 25 × 25 × 280 | The MgO amount corresponding to the autoclave expansion rate of the specimen of 0.5% is taken as the balanced MgO content in concrete. | 2–3% | [63] |

| Cement mortar autoclave method | Cement mortar | 30 × 30 × 280 or 25 × 25 × 280 | The MgO content corresponding to the autoclave expansion rate of the specimen is 0.5%, or the MgO content corresponding to the inflection point of the curve of the autoclave expansion rate with the MgO content is taken as the balanced MgO content of concrete | 3.5–4.5% | [1] |

| One graded concrete autoclave method | One graded concrete | 55 × 55 × 280 | It is the same as the cement mortar autoclave method | 4–5% | [64] |

| Simulated cement paste autoclave method | Simulated cement paste | 25 × 25 × 280 | It is the same as the cement paste autoclave method | 4.5–6.5% | [65] |

| Simulated mortar autoclave method | Simulation mortar | 25 × 25 × 280 | The MgO content corresponding to the inflection point of the curve of autoclave expansion rate with MgO content is taken as the balanced MgO content of concrete | 5–10% | [66] |

The theoretical basis of the above MgO balanced content determination method is the same. All of them are based on the autoclave principle. The cement-based material specimens are placed in a high temperature environment, so that the vast majority of MgO can undergo hydration and expansion reaction in a short time. Then, the expansion deformation caused by MgO that takes several years to be observed is exposed in a short time. The relative change in the specimen length before and after the test is used to determine whether the MgO content in cement-based materials is balanced. However, while the autoclave test accelerates the hydration reaction of MgO, the high-temperature and high-pressure environment may weaken the strength of the cement stone and destroy the bonding force that restricts the expansion of the specimen [67] so that the autoclave expansion amount of the specimen may be exaggerated. In other words, the autoclave test of the specimen-mixed MgO is qualified, and the corresponding volume stability of concrete is absolutely balanced. On the contrary, the autoclave test of the specimen-mixed MgO is not qualified, and the corresponding volume stability of concrete is not necessarily unbalanced. Therefore, further research is needed to explore a method for determining MgO balanced content matching with the deformation characteristics of dam concrete.

3.3 Mathematical model of deformation of magnesium oxide concrete

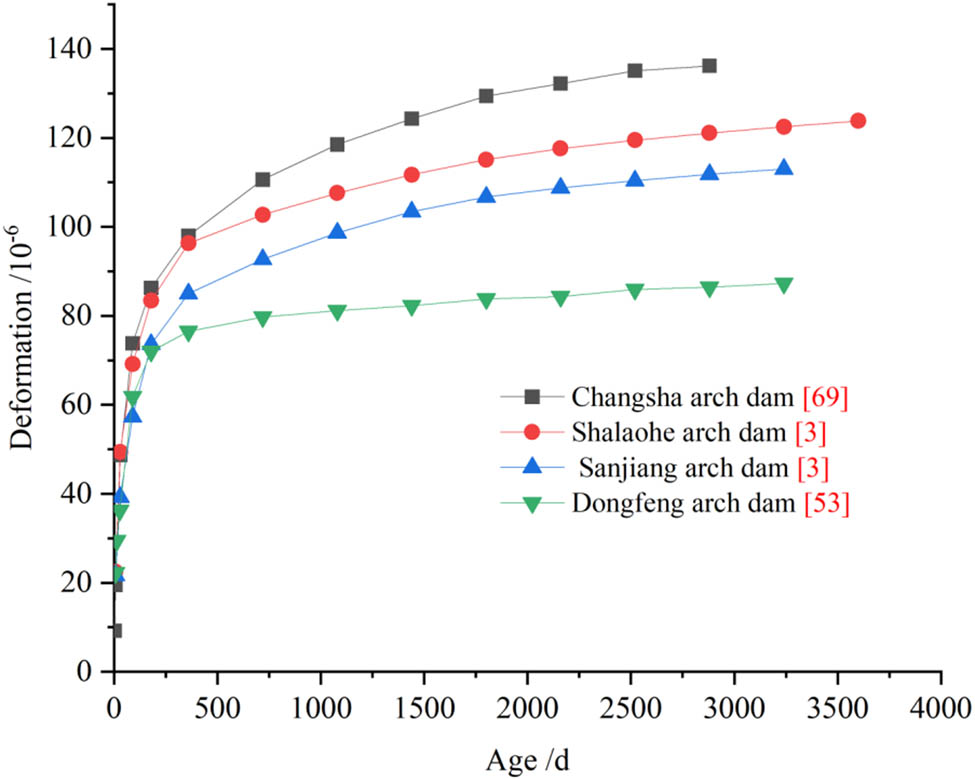

Not only laboratory experiments but also a large number of engineering examples have proved that MgO concrete does have good delayed microexpansion characteristics. The prototype observation results of MgO concrete for the Dongfeng Arch Dam Foundation in Guizhou [52], Changshaba Arch Dam in Guangdong [68], Shalaohe Arch Dam in Guizhou, and Sanjiang Arch Dam in Guizhou [3] with an age of more than 2,900 days, as shown in Figure 5, are important examples. The raw material consumption of MgO concrete used in these four projects is shown in Table 2. As can be seen from Table 2 and Figure 5, the composition materials of MgO concrete and its dosage affect the expansion amount of concrete. Among them, the influence of MgO content is more obvious. In general, the expansion of concrete with a larger MgO content will be larger.

Observation results of autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete in practical engineering.

Raw material consumption of MgO concrete used in typical projects (kg/m3)

| Ref. | Project name | Water | Cement | Fly ash | Admixture | MgO | Sand | Aggregate/mm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5–20 | 20–40 | 40–80 | 80–120 | ||||||||

| [52] | Dongfeng | 92 | 129 | 55 | 1.38 | 6.44 | 474 | 336 | 336 | 504 | 504 |

| [68] | Changshaba | 96 | 136 | 60 | 1.17 | 8.20 | 551 | 316 | 474 | 780 | 0 |

| [3] | Shalaohe | 95 | 112 | 61 | 1.21 | 8.13 | 548 | 343 | 343 | 515 | 515 |

| [3] | Sanjiang | 95 | 130 | 56 | 1.30 | 9.30 | 539 | 344 | 344 | 516 | 516 |

Before designing the temperature control measures of the MgO concrete dam, the designer often needs to analyze the expansion history and expansion amount of MgO concrete in order to determine the stress and strain state of the MgO concrete dam. However, due to the limitation of test conditions, it is very difficult to observe the deformation of MgO concrete indefinitely in the laboratory. Therefore, according to the laboratory test and engineering application results of MgO concrete long-term deformation, the researchers constructed several mathematical models based on certain assumptions. Typical models include the hyperbola model constructed by Yang et al. [69], the dynamics model constructed by Zhang et al. [70], the hyperbola improvement model constructed by Liu et al. [71,72], the exponential hyperbola model constructed by Xu et al. [73], and the arc tangent curve model constructed by Chen et al. [74,75]. All these models reflect the basic law of autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete, and their mathematical expressions and the influencing factors considered are shown in Table 3. Therefore, when analyzing the stress and strain of the MgO concrete dam, designers can choose one or two models to predict the long-term deformation of MgO concrete on the premise that MgO concrete has autogenetic volume deformation test data at an age of not less than 180 days, so as to provide basic data for the temperature control design of MgO concrete dam.

Typical mathematical models of MgO concrete deformation and its influence factors

| Ref. | Model name | Mathematical expression of the model | Influence factors considered by the model |

|---|---|---|---|

| [69] | Hyperbola model |

|

Age and temperature |

| In the equation, ε is the autogenous volume expansion of MgO concrete, t is the age (day), and T is the ambient temperature (°C). | |||

| [70] | Dynamics model |

|

Age and temperature |

| In the equation, ε g and ε 0 are the expansion amount and the final expansion amount of MgO concrete at a certain time, respectively, T is the ambient temperature (°C), γ is the undetermined coefficient, α is the reaction factor, and β is the reaction stage | |||

| [71,72] | Hyperbola improvement model |

|

Age, temperature, MgO content, and fly ash content |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

| 20°C时, k 3 = 0.58, 30°C时, k 3 = 1.00, 40°C时, k 3 = 1.21; c = 0.00023。 | |||

| In the formulas, G(t) is the autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete, t is the age (day), M is the magnesium oxide content (%), F is the fly ash content (%), k 3 is the influence coefficient of ambient temperature on the autogenous volume deformation of concrete, and c is a constant | |||

| [73] | Exponential hyperbola model |

|

Age and temperature |

| In the equations, ε g[a g(t e)] is the autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete based on hydration degree; t e is the equivalent age maturity of concrete relative to the reference temperature; ε gu is the final deformation of MgO concrete; a g(t e) is the hydration degree of MgO in concrete based on equivalent age; and m and n are calculation constants | |||

| [74,75] | Arc tangent curve model | ε = aT·arctan (bD) | Age and temperature |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

| In the formulas, ε is the autogenous volume expansion of concrete, ε max is the ultimate expansion of the autogenous volume deformation of concrete, T is the ambient temperature (°C), and D is the age (day). |

As can be seen from Table 3, the above mathematical models at least reflect the influence of age and temperature on the autogenous volume deformation of concrete and at most reflect the influence of age, temperature, MgO content, and fly ash content on the autogenous volume deformation of concrete, but do not fully reflect the influence factors of MgO concrete’s autogenous volume deformation. For example, the influence of water/binder ratio [76], cement variety [40], aggregate grading [40], specimen size [39], and other factors on the autogenous volume deformation of concrete is not reflected in the above model. Moreover, except for the hyperbolic modified model, the other four models need to refer to the laboratory test data and the long-term observation results of the existing MgO concrete dam in advance to predict the final expansion ε max of the autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete. When there is little or no long-term observation of MgO concrete dams, it is difficult to predict the final expansion amount or the accuracy of the predicted final expansion amount is low. Therefore, the above models have limitations and need to be further studied and improved, especially the mathematical model of autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete under the combined action of multiple factors.

4 Magnesium oxide concrete dam

A magnesium oxide concrete dam is a retaining dam made of MgO concrete. In China, the use of MgO concrete in dam construction has experienced a development process from the partial application of MgO concrete in the dam body to the application of MgO concrete in the whole dam of low, medium, and medium–high dams. Moreover, from laboratory tests to engineering applications, from theory to practice, the cycle is repeated to verify each other. Today, in China, from MgO production MgO concrete design to MgO concrete dam construction, a set of complete and standardized MgO concrete dam construction technologies has been formed. Moreover, more than 60 MgO concrete dams have been built using this technology. Among them, 18 dams use MgO concrete for the whole dam, as shown in Table 4. Of the >60 dams built with MgO concrete in China, there are Dongfeng Arch Dam in Guizhou Province, the first in the world to actively use special MgO in the dam foundation (completed in June 1993), Changsha Arch Dam in Guangdong Province, the first in the world to apply special MgO to the whole dam concrete (completed in April 1999), Huangjiazhai Arch Dam in Guizhou Province, the first in the world to add up to 6.5% MgO to the whole normal concrete (completed in March 2016), and Dahe Arch Dam in Guizhou Province, the world's first full-dam RCC with MgO content up to 6.5% (completed in May 2020) [5]. Looking back, the design and construction of MgO concrete dams involve two important tasks that are obviously different from non-MgO concrete dams, namely, the design of dam temperature control and the detection of the distribution uniformity of MgO in concrete dams.

Overview of dams built with MgO concrete for the whole dam in China [4]

| Serial number | Dam name | Dam height/m | Number of induced joints/pieces | Concrete volume/m3 | MgO content/% | Concrete expansion at age 1a/10−6 | Dam construction time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Changshaba Arch Dam in Guangdong Province | 59.5 | 0 | 34,600 | 3.5–4.5 | 160–180 | 1991.01–1999.04 |

| 2 | Shimenzi Arch Dam in Xinjiang autonomous region | 109.0 | 0 | 210,000 | 2.0 | Around 20 | 1999.04–2000.05 |

| 3 | Longshou Arch Dam in Gansu Province | 80.0 | 2 | 68,300 | 3.0–4.5 | 45–60 | 2000.04–2001.06 |

| 4 | Shalaohe Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 61.7 | 0 | 55,000 | 4.7 | 95–110 | 2001.03–2001.10 |

| 5 | Sanjiang Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 71.5 | 2 | 38,000 | 5.0 | 50–120 | 2002.12–2003.06 |

| 6 | Bamei Arch Dam in Guangdong Province | 53.5 | 0 | 38,000 | 5.0–5.5 | Unknown | 2003.02–2003.07 |

| 7 | Yujianhe Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 81.0 | 2 | 112,000 | 5.0 | 10–45 | 2003.10–2005.03 |

| 8 | Changtan Arch Dam in Guangdong Province | 53.0 | 0 | 29,000 | 5.5–5.75 | 120–160 | 2004.04–2004.12 |

| 9 | Luojiaohe Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 81.0 | 4 | 96,000 | 5.0 | 40–100 | 2005.12–2006.08 |

| 10 | Macaohe Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 67.5 | 4 | 38,000 | 6.0 | 50–150 | 2007.03–2007.10 |

| 11 | Huanghuazhai Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 108.0 | 4 | 292,000 | 3.0–3.9 | 10–45 | 2007.04–2010.12 |

| 12 | Laojiangdi Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 67.0 | 3 | 65,000 | 5.5–6.0 | 70–110 | 2007.12–2008.10 |

| 13 | Hewan Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 80.0 | 6 | 91,000 | 5.0 | 50–150 | 2011.05–2013.04 |

| 14 | Yuliang Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 50.0 | 2 | 35,500 | 5.0 | 115–190 | 2013.02–2014.07 |

| 15 | Xiatun Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 69.0 | 2 | 55,000 | 5.0 | 30–69 | 2013.12–2016.09 |

| 16 | Huangjiazhai Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 69.0 | 2 | 45,000 | 6.5 | 32–102 | 2014.04–2016.03 |

| 17 | Liangtiangou Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 60.2 | 6 | 45,000 | 5.5 | 25–90 | 2016.11–2018.04 |

| 18 | Dahe Arch Dam in Guizhou Province | 105.0 | 4 | 456,600 | 6.5 | 60–110 | 2017.12–2020.05 |

4.1 Temperature control design of magnesium oxide concrete dam

When conventional concrete is poured into the dam, owing to the huge volume of concrete, according to the design code of the China concrete arch dam [77], it is necessary to set a transverse joint every 15–25 m on the dam body to adapt to the change of thermal expansion and cold contraction of concrete in the design of dam temperature control. Obviously, the more the number of transverse joints, the greater the construction interference, the slower the construction speed, and the higher the construction cost. Therefore, reducing the number of transverse joints has become the goal of dam designers. Experimental research and engineering practice show that [1,3,4,5], within the range of MgO balanced content, the expansion deformation of concrete tends to be stable after the age of 360–540 days, and the expansion amount is mostly 50 × 10−6 to 150 × 10−6 when it is stable. It can partially offset the volume shrinkage of dam concrete during the long temperature drop. Therefore, when MgO concrete is used to build a dam, it is possible to have fewer transverse joints in the concrete dam. Through years of theoretical and practical exploration [78–81], when pouring MgO concrete dam now, in order to release the excessive tensile stress when the delayed micro-expansion of MgO concrete is not enough to compensate for the dam temperature stress and to guide the joint surface cracking and control the extension direction of the joint, 2–4 induced joints are prearranged in the upper section of the dam where cracks are most likely to occur. The most likely crack location is mostly determined by the stress simulation calculation of the dam body. The induced joint spacing of different dams is different, and the joint spacing of the riverbed dam section is larger, generally ranging from 50 to 130 m. The joint spacing of the dam section on the bank slope is small, generally 20–40 m. The specific spacing and number of induced joints in each dam are determined by the expansion performance of the MgO concrete used in that dam. That is, the expansion performance of MgO concrete determines the temperature control measures of the MgO concrete dam. Figure 6 shows an atypical design of the induced joint [81].

![Figure 6

A typical induced joint design: (a) induced joint profile 1:20, (b) induced joint plan view 1:50, (c) detail of grout box installation 1:5, and (d) precast section view 1:10 [81].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0094/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0094_fig_006.jpg)

A typical induced joint design: (a) induced joint profile 1:20, (b) induced joint plan view 1:50, (c) detail of grout box installation 1:5, and (d) precast section view 1:10 [81].

Engineering practice has proved that the use of MgO concrete dam construction greatly reduces the number of transverse joints of a concrete dam, and, through the installation of induced joints, the aggregate used to produce concrete cannot be pre-cooled in advance, the dam concrete cannot bury the cooling water pipe, which can realize continuous (or short intermittent) concrete pouring and all-weather construction, and even cancel or simplify the arch dam sealing grouting. The wish of speeding up construction progress and saving project investment is realized.

4.2 Uniformity of magnesium oxide in dam concrete

MgO is insoluble in water at room temperature, and the content in concrete is very small (generally 2–6%), especially since the expansion deformation time is very long. Suppose the specially mixed MgO is unevenly distributed in the dam concrete. In that case, the delayed expansion amount generated by excessively aggregated MgO in the cement hydration process may cause significant differences in the expansion amount of concrete in different parts, increase the local tensile stress of concrete, cause the decline of the mechanical properties of concrete and the damage of the structure, lead to dam cracking, and endanger the project safety. Therefore, we must pay great importance to the distribution uniformity of MgO in the dam concrete.

The distribution uniformity of MgO in dam concrete includes two situations. First, the distribution uniformity of MgO in the concrete mixture is mixed at the same time, that is, the uniformity of MgO concrete in a single tank. The second is the distribution uniformity of MgO in concrete mixes mixed at different times, that is, the uniformity of MgO concrete in different tanks. The distribution uniformity of MgO in concrete can be tested by randomly taking mortar samples at the outlet of the mixer or the concrete bin surface of the dam body. Engineering practice shows [82,83] that MgO can be evenly distributed in concrete by only extending the mixing time of concrete for 30–60 s without changing the concrete production process and technology. Therefore, it is possible not to test the uniformity of a single-tank MgO concrete mixture. However, due to the large volume of dam concrete and the long pouring time, the production process is greatly affected by factors such as human working quality, equipment working conditions, and raw material supply, which may cause the fluctuation of MgO content in concrete mixture mixed at different times. Therefore, the uniformity of the MgO concrete mixture mixed at different times is the inspection focus [82]. Both Guangdong Provincial standard DB44/T703-2010 [20] and Guizhou Provincial standard DB52/T720-2010 [21] recommend the use of a chemical method to test the distribution uniformity of MgO in the concrete mixture, and the results of random sampling at the outlet of the mixer shall be regarded as the standard. The test sample is wet-screened mortar, and the interval time of random sampling is no more than 4 h, the number of samples sampled at each time is no less than 3, and the weight of each sample is no less than 2 g. The MgO content of the sample is first tested by the complexometric titration method, and then the measured value is statistically analyzed. Finally, the uniformity of MgO distribution in concrete is determined according to the deviation coefficient Cv (Table 5). Nevertheless, it is still worth studying whether there is a more rapid uniformity detection method and whether a more rapid uniformity detection instrument can be developed.

| Uniformity grade | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concrete strength grade | Excellent | Good | General | Inferior |

| <C9020 | <0.15 | 0.15–0.18 | 0.18–0.22 | >0.22 |

| ≥C9020 | <0.11 | 0.11–0.14 | 0.14–0.18 | >0.18 |

In order to ensure the uniform distribution of MgO in dam concrete and not reduce the production capacity of concrete due to prolonged mixing time, Guangdong Hydropower Group Company first prepared MgO suspension by using MgO and part of water and water reducing agent and then used multi-point disperser during the construction of Madushan Gravity Dam in Yunnan Province. MgO suspension was added to the concrete mixture composed of coarse and fine aggregate, cement, admixture, and water by multi-point dispersion method, and MgO concrete was finally made by mixer, which realizes the desire of no reduction in concrete output and good uniformity [84].

5 Conclusion and prospects

The development of MgO, MgO concrete, and MgO concrete dams in China has been more than 40 years since the beneficial effect of MgO was accidentally discovered in Baishan Dam in China in the early 1980s. Through the continuous research and practice of a large number of engineers and researchers, through the partial application of MgO concrete in dam bodies to the whole application of MgO concrete for the low dam, medium dam, and medium–high dam, a set of complete and standardized MgO concrete dam construction technology has been formed from MgO production, MgO concrete design, to MgO concrete dam construction. More than 60 MgO concrete dams have been built using this technology. Through engineering practice, the following conclusions are verified, and the problems that need further research are found.

The calcination system of magnesite determines the activity of MgO. When the magnesite is calcined in an environment in the temperature range of 1,000–1,100°C and a high temperature lasting for half an hour, the MgO expansive agent, which matches the long temperature drop shrinkage of dam concrete, can be prepared. However, it is still an important topic in the future to study more easily available and more economical raw materials for MgO production and simpler MgO production processes.

The activity of MgO determines the expansion performance of MgO concrete. MgO concrete made by adding special MgO into concrete has good delayed microexpansion characteristics, and its expansion deformation can compensate for the volume shrinkage of dam concrete during the long-temperature drop process so as to improve the cracking resistance of dam concrete. In addition, the MgO balanced content in concrete can be determined by the cement paste autoclave method, cement mortar autoclave method, one graded concrete autoclave method, simulated cement paste autoclave method, and simulated mortar autoclave method, and the measured value of MgO balanced content increases according to the order of these methods. At the same time, the current method of determining MgO balanced content in concrete has limitations. Further research is needed to explore a method to determine MgO balanced content that matches the deformation characteristics of dam concrete.

The expansion performance of MgO concrete determines the temperature control measures of the MgO concrete dam. When designing the temperature control measures of dams, one or two models can be selected from the hyperbola model, dynamics model, hyperbola improvement model, exponential hyperbola model, and arc tangent curve model to predict the long-term deformation of MgO concrete. By focusing on the delayed micro-expansion effect of MgO concrete fully, only a very small number of induced joints can be set on the dam, which greatly reduces the number of transverse joints of the concrete dam, makes continuous (or short intermittent) concrete pouring and all-weather construction become a reality, and even cancel or simplify the arch dam sealing grouting, so as to accelerate the construction progress and save project investment. Similarly, there are still limitations to current mathematical models. In particular, the mathematical model under the combined action of multiple factors needs to be further studied.

Without changing the concrete production process and technology, MgO can be evenly distributed in concrete only by extending the mixing time of concrete for 30–60 s. Therefore, when the uniformity of MgO distribution in dam concrete is tested, the focus of work is not on the concrete mixture mixed at the same time but on the concrete mixture mixed at different times. Although the chemical method can test the distribution uniformity of MgO in concrete, it is still necessary to find a more rapid detection method or develop a more rapid detection instrument.

In short, after the special MgO is properly mixed into the dam concrete, the concrete's cracking resistance is improved, the temperature control measures are simplified, the construction period of the dam is shortened, and the project investment is reduced, which realizes the wish of building a dam well, quickly, and economically. Therefore, the MgO concrete dam construction technology is worth popularization and application. At the same time, the problems found in the popularization and application of MgO concrete dam construction technology should not be ignored but should be studied and solved in further applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 51869005, 51269003, 50969002), which funded this project.

-

Funding information: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers 51869005, 51269003, and 50969002.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

[1] Cao, Z. S. and X. Jinhua. Construction technology of dam with MgO concrete, China Electric Power Press, Beijing, China, 2003, pp. 4–7.Search in Google Scholar

[2] Mo, L. W., D. Min, T. Mingshu, and A. Abir. MgO expansive cement and concrete in China: Past, present and future. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 57, 2014, pp. 1–12.10.1016/j.cemconres.2013.12.007Search in Google Scholar

[3] Guizhou water resources and hydropower survey and design institute. Research and engineering practice on key technology of construction of MgO concrete arch dam, China Water Resources and Hydropower Press, Beijing, China, 2016, pp. 4–6.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Chen, C. L. Autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete, China Science Press, Beijing, China, Vol. 11, 2020, pp. 6–11.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Chen, C. L. and C. Rongfei. Application of magnesium oxide expansive agent in hydraulic concrete. Magazine of Concrete Research, Vol. 75, No. 2, 2023, pp. 97–106.10.1680/jmacr.21.00337Search in Google Scholar

[6] Mehta, P. K., D. Pirtz, and G. J. Komandant. Magnesium oxide additive for producing self-stress in mass concrete. In Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Chemistry of Cement, Vol. III, No. 3, Paris, France, 1980, pp. 6–9.Search in Google Scholar

[7] Yuan, M. X. and T. Mingshu. Study on autogenous volume expansion mechanism of concrete for baishan dam in jilin province. Journal of nanjing institute of chemical technology, Vol. 26, No. 4, 1984, pp. 38–45.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Zheng, L., C. Xuehua, and T. Mingshu. MgO-type delayed expansive cement. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 21, No. 6, 1991, pp. 1049–1057.10.1016/0008-8846(91)90065-PSearch in Google Scholar

[9] Birchal, V. S. S., S. D. F. Rocha, and V. S. T. Ciminelli. The effect of magnesite calcination conditions on magnesia hydration. Minerals Engineering, Vol. 13, No. 14–15, 2000, pp. 1629–1633.10.1016/S0892-6875(00)00146-1Search in Google Scholar

[10] Cui, X. and D. Min. Effects of calcined conditions on activity of MgO. Journal of Nanjing University of Technology (Natural Science Edition), Vol. 30, No. 4, 2008, pp. 52–55.Search in Google Scholar

[11] Chau, C. K. and L. Zongjin. Accelerated reactivity assessment of light burnt magnesium oxide. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, Vol. 91, No. 5, 2008, pp. 1640–1645.10.1111/j.1551-2916.2008.02330.xSearch in Google Scholar

[12] Gao, P. W., L. Xiaolin, G. Fei, L. Xiaoyan, H. Jie, L. Hui, et al. Production of MgO-type expansive agent in dam concrete by use of industrial by-products. Building and Environment, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2007, pp. 453–457.10.1016/j.buildenv.2007.01.037Search in Google Scholar

[13] Li, F. X., C. Youzhi, L. Shizong, W. Bing, and L. Guogang. Research on the preparation and properties of MgO expansive agent. Advances in Cement Research, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2010, pp. 37–44.10.1680/adcr.2008.22.1.37Search in Google Scholar

[14] Mo, L. W., D. Min, and T. Mingshu. Effects of calcination condition on expansion property of MgO-type expansive agent used in cement-based materials. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 40, No. 3, 2009, pp. 437–446.10.1016/j.cemconres.2009.09.025Search in Google Scholar

[15] Peng, S. S., Z. Shihua, Y. Huaquan, and S. Jie. Effect of preparing process on hydration characteristics of magnesia expansion agents. China Powder Science and Technology, Vol. 20, No. 5, 2014, pp. 67–70.Search in Google Scholar

[16] Lu, A. Q., T. Qian, L. Hua, and Z. Shouzhi. Effect of calcination condition on the composition and expansion properties of MgO expansive agent. China Concrete and Cement Products, Vol. 4, 2017, pp. 8–12.Search in Google Scholar

[17] DL/T 5296-2013. Technical specification of magnesium oxide expansive for use in hydraulic concrete, China Electric Power Press, Beijing, China, 2014.Search in Google Scholar

[18] Cao, F. Z., M. Miao, and Y. Peiyu. Effects of reactivity of MgO expansive agent on its performance in cement-based materials and an improvement of the evaluating method of MEA reactivity. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 187, 2018, pp. 187, 257–266.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.198Search in Google Scholar

[19] Sun, W. H., C. Chong, Z. Honghua, and C. Kehao. Relationship between crystalline size and lattice distortion of MgO and its activity. Jounal of Wuhan University of Technology, Vol. 13, No. 4, 1991, pp. 21–24.Search in Google Scholar

[20] DB44/T 703-2010. Guangdong quality and technical supervision bureau. Guide for technique of MgO-admixed concrete arch dam without transverse joints, Guangdong, China, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[21] DB52/T 720-2010. Guizhou quality and technical supervision bureau. Technical specification for MgO-admixed concrete arch dam construction. Guizhou, China, 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[22] Di, S. M. Magnesite resources and market in China. Non-Metallic Mines, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2001, pp. 5–6+39.Search in Google Scholar

[23] Xu, L. L. and D. Min. Dolomite used as raw material to produce MgO-based expansive agent. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 35, No. 8, 2004, pp. 1480–1485.10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.09.026Search in Google Scholar

[24] Cao, F. Z., L. Yu, and Y. Peiyu. Properties and mechanism of the compound MgO expansive agent (CMEA) produced by calcining the mixture of dolomite and serpentine tailings. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 277, 2021, id. 122331.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122331Search in Google Scholar

[25] Qing, J., D. Min, M. Liwu, and W. Zhilei. Preparation and expansion of MgO expansive agents with low grade magnesite and dolomite. New Building Materials, Vol. 43, No. 11, 2016, pp. 7–11.Search in Google Scholar

[26] Chu, Y. T., W. Yijun, P. Lu, Z. Lianfeng, and W. Kaixiang. Expansion characteristics of MgO-based expansive agents produced by magnesite tailings in restrained mortars. Bulletin of the Chinese Ceramic Society, Vol. 37, No. 4, 2018, pp. 1231–1234.Search in Google Scholar

[27] Chatterji, S. Mechanism of expansion of concrete due to the presence of dead-burnt CaO and MgO. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 25, No. 1, 1995, pp. 51–56.10.1016/0008-8846(94)00111-BSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Liu, J. P., Z. Shouzhi, T. Qian, G. Fei, and W. Yujiang. Deformation behavior of high performance concrete containing MgO composite expansive agent. Journal of Southeast University (Natural Science Edition), Vol. 40, No. S2, 2010, pp. 150–154.Search in Google Scholar

[29] Mo, L. W., D. Yang, L. Anqun, and D. Min. Preparation of MgO- and CaO-bearing expansive agent used for cement-based materials. Key Engineering Materials, Vol. 2178, No. 539, 2013, pp. 211–214.10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.539.211Search in Google Scholar

[30] Zhao, H. T., X. Yu, X. Dongsheng, X. Wen, W. Yujiang, L. Hua, et al. Effects of CaO-based and MgO-based expansion agent, curing temperature and restraint degree on pore structure of early-age mortar. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 257, 2020, id. 119572.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119572Search in Google Scholar

[31] Zhao, H. T., L. Xiaolong, C. Xiaodong, Q. Chunyu, X. Wen, W. Panxiu, et al. Micro-structure evolution of cement mortar containing MgO-CaO blended expansive agent and temperature rising inhibitor under multiple curing temperatures. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 278, 2021, id. 122376.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122376Search in Google Scholar

[32] Yang, Z. B., L. Fuzhou, and Z. Wei. Calcined MgO expansion agent in cement rotary kiln with predecomposition system. Bulletin of the Chinese Ceramic Society, Vol. 37, No. 10, 2018, pp. 51–54.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Gao, P., W. Sheng-xing, L. Ping-hua, W. Zhongru, and T. Mingshu. The characteristics of air void and frost resistance of RCC with fly ash and expansive agent. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 20, No. 8, 2005, pp. 586–590.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2005.01.039Search in Google Scholar

[34] Cwirzen, A. and H. Karin. Effects of reactive magnesia on micro-structure and frost durability of portland cement-based binders. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 25, No. 12, 2013, pp. 1941–1950.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000768Search in Google Scholar

[35] Choi, S., J. Bong-seok, K. Joo-Hyung, and L. Kwang-Myong. Durability characteristics of fly ash concrete containing lightly-burnt MgO. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 58, 2014, pp. 77–84.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.01.080Search in Google Scholar

[36] Liu, K. Z., S. Zhonghe, S. Tao, L. Gang, L. Xiaosheng, and C. Shukai. Effects of combined expansive agents and supplementary cementitious materials on the mechanical properties, shrinkage and chloride penetration of self-compacting concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 211, 2019, pp. 120–129.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.143Search in Google Scholar

[37] Jiang, F. F., D. Min, M. Liwu, and W. Wenging. Influence of combined action of steel fiber and MgO on chloride diffusion resistance of concrete. Crystals, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2020, pp. 338–338.10.3390/cryst10040338Search in Google Scholar

[38] Hu, S. G. and Y. Li. Research on the hydration, hardening mechanism, and micro-structure of high performance expansive concrete. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 29, No. 7, 1999, pp. 1013–1017.10.1016/S0008-8846(99)00084-8Search in Google Scholar

[39] Chen, C. L., C. Rongfei, Z. Zhenhua, L. Weiwei, Y. Shaolian, D. Xiangqin, et al. Influence of specimen size on autogenous volume deformation of long-aged MgO-admixed concrete. Frontiers in Materials, Vol. 8, 2021, id. 639838.10.3389/fmats.2021.639838Search in Google Scholar

[40] Chen, X., Y. Huaquan, and L. Wenwei. Factors analysis on autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete and early thermal cracking evaluation. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 118, 2016, pp. 276–285.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.093Search in Google Scholar

[41] Yan, S. L. and C. Changli. Influence of specimen size on autogenous volume deformation of concrete with magnesium oxide. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Vol. 103, No. 1, 2015, pp. 100–104.10.1088/1757-899X/103/1/012001Search in Google Scholar

[42] Gao, P. W., W. Shengxin, L. Xiaolin, D. Min, L. Pinghua, W. Zhongru, et al. Soundness evaluation of concrete with MgO. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2005, pp. 132–138.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2005.06.033Search in Google Scholar

[43] Gao, P. W., X. Shaoyun, C. Xiong, L. Jun, and L. Xiaolin. Research on autogenous volume deformation of concrete with MgO. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 40, 2013, pp. 998–1001.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.11.025Search in Google Scholar

[44] Wang, L., G. Fanxing, Y. Huamei, W. Yan, and T. Shengwen. Comparison of fly ash, PVA fiber, MgO and shrinkage-reducing admixture on the frost resistance of face slab concrete via pore structural and fractal analysis. Fractals, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2021, pp. 1–33.10.1142/S0218348X21400028Search in Google Scholar

[45] Liu, S. H. and F. Kunhe. Study on autogenous deformation of concrete incorporating MgO as expansive agent. Key Engineering Materials, Vol. 302, 2005, pp. 155–161.10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.302-303.155Search in Google Scholar

[46] Kabir, H. and R. D. Hooton. Evaluating soundness of concrete containing shrinkage-compensating MgO admixtures. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 253, 2020, id. 119141.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119141Search in Google Scholar

[47] Chen, X., Y. Huaquan, Z. Shihua, and Y. Jianjun. Crack resistance of concrete with incorporation of light burnt MgO. Advanced Materials Research, Vol. 168–170, 2010, pp. 1348–1352.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.168-170.1348Search in Google Scholar

[48] Lu, X. L., G. Fei, Z. Hongbo, and C. Xiong. Influence of MgO-type expansive agent hydration behaviors on expansive properties of concrete. Journal of Wuhan University of Technology-Materials Science Edition, Vol. 26, 2011, pp. 344–346.10.1007/s11595-011-0227-zSearch in Google Scholar

[49] Sherir, M., K. M. A. Hossain, and M. Lachemi. The influence of MgO-type expansive agent incorporated in self-healing system of engineered cementitious composites. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 149, 2017, pp. 164–185.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.109Search in Google Scholar

[50] Guo, J. J., Z. Shiwei, Q. Cuige, C. Lin, and Y. Lin. Effect of calcium sulfoaluminate and MgO expansive agent on the mechanical strength and crack resistance of concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 299, 2021, id. 123833.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123833Search in Google Scholar

[51] Li, C. M. and Y. Yuanhui. Study on long term autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, No. 3, 1999, pp. 54–58.Search in Google Scholar

[52] Chen, C. L., T. Chengshu, and Z. Zhenhua. Application of MgO concrete in China Dongfeng Arch Dam Foundation. Advanced Materials Research, Vol. 168–170, 2011, pp. 1953–1956.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.168-170.1953Search in Google Scholar

[53] Cao, F. Z. and Y. Peiyu. The influence of the hydration procedure of MgO expansive agent on the expansive behavior of shrinkage-compensating mortar. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 202, 2019, pp. 162–168.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.01.016Search in Google Scholar

[54] Li, C. M. Temperature effect test and application on self-deformation of concrete mixed with MgO. Journal of Advances in Science and Technology of Water Resources, Vol. 19, No. 5, 1999, pp. 33–37+69.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Deng, M., C. Xuehua, L. Yuanzhan, and T. Mingshu. Expansive mechanism of magnesia as an additive of cement. Journal of Nanjing University of Chemical Technology, Vol. 12, No. 4, 1990, pp. 1–11.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Zhang, J. Recent advance of MgO expansive agent in cement and concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 45, 2022, id. 103633.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103633Search in Google Scholar

[57] Lea, F. M. The chemistry of cement and concrete, 3rd edn. 1971, id. 369. Chemical Publishing Company, New York.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Mehta, P. K. History and status of performance tests for evaluation of soundness of cements. Cement standards-Evolution and Trends. Symposia Papers & STPs, STP663, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1978, pp. 35–60.10.1520/STP35785SSearch in Google Scholar

[59] ASTM C150-75, Stndard specification for Portland cement designation C150-75, Book of ASTM Standards Part I0: USA, 1975.Search in Google Scholar

[60] BSEN197-1: 2000, Cement-Part 1: Composition, specifications and conformity criteria for common cements, UK, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

[61] ASTMC150M-12, Standard specification for Portland cement. ASTM: USA, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[62] GB175-2007. General administration of quality supervision, inspection and quarantine of the People's Republic of China, standardization administration of China. Common Portland Cement. China Standard Press, Beijing, China, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Li, C. M., C. Xuemao, and L. Xiaoyong. Several problems about the pressure-braise test of MgO concrete. Guangdong Water Resources and Hydropower, Vol. 6, 2009, pp. 1–4+14.Search in Google Scholar

[64] Li, C. M., L. Wanjun, and C. Xuemao. The influence of coarse concrete and thin concrete for high-pressure-braise test. Water Power, Vol. 35, No. 4, 2009, pp. 38–41.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Chen, C. L. and F. Kunhe. Study on simulation test method for invariability of concrete with light-burned magnesium oxide. Journal of Hydroelectric Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 5, 2012, pp. 241–244.Search in Google Scholar

[66] Chen, C. L., L. Weiwei, L. Liangchuan, and C. Rongfei. Study on limit contents of MgO expansion agent in hydraulic concrete. Journal of Functional Materials, Vol. 46, No. S1, 2015, pp. 100–104.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Kabir, H., H. R. Douglas, and N. J. Popoff. Evaluation of cement soundness using the ASTM C151 autoclave expansion test. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 136, 2020, id. 106159.10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106159Search in Google Scholar

[68] Liu, Z. W. Application and development of quick damming technique by using concrete mixed with MgO in Guangdong Province. Water Resources and Hydropower Engineering, Vol. 33, No. 6, 2002, pp. 30–32+72–73.Search in Google Scholar

[69] Yang, G. H. and Y. Mingdao. The hyperbola model for autogenous expansion volume deformation of MgO concrete. Journal of Hydroelectric Engineering, Vol. 23, No. 4, 2004, pp. 38–44.Search in Google Scholar

[70] Zhang, G. X., C. Xianming, and D. Lihui. Expansion model of dynamics describing MgO concrete. Water Resources and Hydropower Engineering, Vol. 35, No. 9, 2004, pp. 88–91.Search in Google Scholar

[71] Liu, S. H. and F. Kunhe. Mathematical model of autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete. Journal of Hydroelectric Engineering, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2006, pp. 81–84.Search in Google Scholar

[72] Nguyen, C. V., T. Fuguo, and N. Van Nghia. Modeling of autogenous volume deformation process of RCC mixed with MgO based on concrete expansion experiment. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 210, 2019, pp. 650–659.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.226Search in Google Scholar

[73] Xu, P., Z. Yueming, and B. Nenghui. Computing model for autogenous volume deformation of MgO concrete based on degree of hydration. Water Resources and Hydropower Engineering, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2008, pp. 22–25.Search in Google Scholar

[74] Chen, C. L., F. Linan, and F. Kunhe. Arc tangent curve model of the self-volume deformation of MgO concrete. Journal of Hydroelectric Engineering, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2008, pp. 106–110.Search in Google Scholar

[75] Chen, R. F. and C. Changli. Improved formula for calculating parameters of arctangent curve model for the autogenous volume deformation of MgO-admixed concrete. Journal Yangtze River Scientific Research Institute, Vol. 37, No. 10, 2020, pp. 161–164.Search in Google Scholar

[76] Cao, F. Z. and Y. Peiyu. Effect of water-binder ratio on hydration degree and expansive characteristics of magnesium oxide expansive agents. Journal of the Chinese Ceramic Society, Vol. 47, No. 2, 2019, pp. 171–177.Search in Google Scholar

[77] DL/T 5346-2006. National development and reform commission of the People’s Republic of China, standardization administration of China. Design specification for concrete arch, China Electric Power Press, Beijing, China, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

[78] Luo, X. Q., Z. Guoxin, J. Feng, and L. Zhenwei. Simulation analysis of MgO concrete arch dam without contraction joints. Journal of Hydroelectric Engineering, No. 2, 2003, pp. 80–87.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Luo, J. and Y. Guanghua. Finite element simulation of MgO concrete in rapid dam construction technology. Pearl River, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2005, pp. 55–57.Search in Google Scholar

[80] Wang, Q., C. Xiaolin, L. Guowei, and Z. Chao. Effect of expansion deformation of high arch dam with magnesium oxide on transverse joint opening. Engineering Journal of Wuhan University, Vol. 46, No. 5, 2013, pp. 588–592.Search in Google Scholar

[81] Chen, C. L., S. Xianping, and C. Xuemao. Application of damming technology with MgO admixed concrete used in the whole dam in Guizhou,s arch dam. Journal of Advances in Science and Technology of Water Resources, Vol. 37, No. 5, 2017, pp. 84–88, 94.Search in Google Scholar

[82] Chen, C. L. Check and evaluation on uniformity of concrete admixed with MgO expanding agent. Journal of Hydroelectric Engineering, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2007, pp. 75–78.Search in Google Scholar

[83] Xia, C. F. and Z. Aiping. Research on rapid teet methed of MgO mingled in concrete from entrance of a mixer. Journal of Shanxi Water Power, Vol. 9, No. 1, 1994, pp. 56–58.Search in Google Scholar

[84] Xie, X. M. New method of quick homogeneous mixing roller compacted concrete incorporating MgO. Concrete, No. 1, 2010, pp. 130–131, 135.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Towards sustainable concrete pavements: a critical review on fly ash as a supplementary cementitious material

- Optimizing rice husk ash for ultra-high-performance concrete: a comprehensive review of mechanical properties, durability, and environmental benefits

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Experimental and RSM-based optimization of sustainable concrete properties using glass powder and rubber fine aggregates as partial replacements

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis