Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

-

Irfan Ullah

, Muhammad Faisal Javed

, Hisham Alabduljabbar

Abstract

This study explored advanced hybrid machine learning (ML) techniques for estimating the non-steady-state migration coefficient (D nssm) of concrete, a key indicator of chloride penetration resistance. Support vector regression (SVR) was integrated with four metaheuristic optimization techniques: grey wolf optimization (GWO), gorilla troops optimization (GTO), firefly algorithm (FFA), and particle swarm optimization (PSO) to improve predictive accuracy. Among these models, SVR-GTO exhibited the superior effectiveness, attaining the maximum R 2 of 0.97 and the lowest root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.93. The SVR-GWO model similarly demonstrated the robust predictive accuracy, with an R 2 of 0.92 and an RMSE of 1.55, whereas the SVR-PSO and SVR-FFA models recorded slightly lower R 2 of 0.91 and 0.89, with RMSE of 1.67 and 2.13, respectively. To enhance model transparency and interpretability, the study employs SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), partial dependence plots, and individual conditional expectation plots, offering a comprehensive understanding of how predictors affect the predicted outcomes. SHAP model revealed the higher significance of water-to-binder ratio (W/B), migration test (MT) age, and total aggregate (TA) in predicting the D nssm. An interactive graphical interface was created to estimate the D nssm of concrete, allowing efficient model interaction and eliminating the need for physical experimentation.

1 Introduction

Steel-reinforced concrete structures in coastal environments often suffer deterioration due to exposure to aggressive chemical agents, including water [1], 2], carbon dioxide [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], sulphates [7], [8], [9], and especially chloride ions [10], [11], [12]. Chlorides are the primary cause of corrosion in steel reinforcement, resulting in reduced durability, cracking, spalling, and loss of strength in concrete structures [13], 14]. When chloride ions penetrate the concrete’s pore system, they disrupt the protective oxide layer on steel reinforcement, initiating corrosion that can cause severe structural damage and significant economic costs [15]. Corrosion begins once the chloride concentration at the steel surface exceeds a critical threshold, with the time to onset influenced by the concrete’s diffusion properties and the environmental exposure to chloride. High chloride levels, common in marine areas, accelerate deterioration and reduce concrete’s load-bearing capacity. To protect structures, it is essential to use low-chloride materials, corrosion inhibitors, protective coatings, and properly designed concrete mixes with sufficient reinforcement cover. Regular monitoring and maintenance are also necessary to ensure long-term durability [15], 16].

Marine aerosols, generated by sea surface bubbles and transported inland by wind, are the primary source of chloride ions that cause corrosion in coastal concrete structures [17]. Their concentration increases with wind speed [18], while deicing salts add to chloride exposure even far from roads and at high elevations globally [19]. Assessing chloride accumulation in offshore concrete is vital for durability evaluation, with field data informing accurate chloride ingress models [20]. Chloride penetration involves multiple transport mechanisms, mainly diffusion, modeled using Fick’s second law, where the diffusion coefficient measures ion spread over time [21]. Rapid chloride migration tests offer quick assessment but may lack field accuracy, whereas wetting-drying and immersion tests provide realistic results but are time-consuming [22]. Designing durable concrete requires optimizing mixes for chloride resistance and minimal cement use, but verifying this through standard lab tests is slow and resource intensive. Therefore, fast, reliable, and comprehensive predictive methods are needed to estimate chloride penetration resistance efficiently, addressing the complexity of chloride transport in concrete.

Several research studies have explored the implementation of machine learning (ML) in estimating the properties of concrete, thereby eliminating the need for laborious and resource-intensive laboratory testing. Multi-objective optimization techniques combined with ML algorithms have been employed to enhance ingredient proportions for concrete mix design, which can be implemented at batching facilities to efficiently produce high-strength concrete before construction [23]. A hybrid backpropagation neural network (BPNN) model utilizing ReLU activation functions was created to forecast the shear strength of reinforced concrete beams, achieving an R 2 value of 0.924 and a mean squared error of 10.611 kN [24]. An optimized BPNN was also developed to estimate surface chloride infiltration in concrete exposed to marine conditions, outperforming conventional and advanced models with an R 2 value of 0.91 and offering faster, more efficient predictions [25]. To estimate surface chloride content in marine concrete, ML models such as support vector regression (SVR) and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) were trained on preprocessed data, with the ensemble model achieving superior accuracy (R 2 = 0.95) compared to the individual models [26]. AQ21 and WEKA, using the J48 algorithm, were employed to automate the classification of plain and CFBC fly ash-enhanced concrete, identifying materials with high chloride resistance [27]. An artificial neural network (ANN) model was also used to assess chloride diffusivity in high-performance concrete, showing high prediction accuracy when validated against experimental data [28]. Additionally, a metaheuristic algorithm was applied to enhance a BPNN model’s performance in predicting chloride levels, surpassing traditional BPNN methods [29]. Utilizing observed data, another ANN model was employed to correlate input parameters with the depth of chloride ion penetration under drying–wetting cycles [30]. ANN and XGBoost have proven effective in accurately predicting the natural frequencies of functionally graded nanobeams [31]. Physics-informed recurrent neural networks have enhanced elastoplastic constitutive modeling by improving stability and extrapolation capabilities [32]. Hybrid metaheuristic-optimized neural networks have achieved superior accuracy in predicting concrete-reinforcement bond strength, outperforming traditional analytical models [33]. Additionally, hybrid approaches combining ML and finite element analysis have accelerated material parameter calibration, resulting in improved accuracy and reduced computational time [34]. Moreover, XGB excelled in predicting remediation outcomes, with Bayesian optimization boosting model performance and SHAP analysis offering interpretability [35].

This study tackles a critical issue by minimizing the dependence on labor-intensive and resource-demanding laboratory tests for assessing chloride diffusion in concrete through advanced ML techniques. By leveraging hybrid ML models, this research aims to develop a reliable predictive framework for estimating the non-steady-state migration diffusion coefficient (D nssm) of concrete, a crucial parameter for ensuring the long-term performance of reinforced concrete structures subjected to chloride exposure. Support vector regression (SVR) was integrated with four metaheuristic optimization techniques: grey wolf optimization (GWO), gorilla troops optimization (GTO), firefly algorithm (FFA), and particle swarm optimization (PSO) to improve predictive accuracy. These algorithms were selected based on a combination of their diverse exploration-exploitation mechanisms, proven effectiveness in solving complex nonlinear problems, and their increasing adoption in civil engineering applications. GWO and PSO are well-established and widely used due to their robustness and global search capabilities, whereas FFA offers excellent local search refinement through its light-attraction mechanism. GTO, a relatively recent algorithm, was included for its innovative exploration strategy, inspired by the social behavior of gorillas, and represents a novel addition to the field. The combination of established and emerging algorithms aimed to balance innovation with performance reliability in optimizing SVR parameters. To enhance model interpretability, tools such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), partial dependence plots (PDP), and individual conditional expectation plots (ICE) were used, offering important understanding of how individual input variables influence predictions. Furthermore, an interactive graphical interface was created to facilitate the prediction of D nssm, providing rapid results and eliminating the reliance on conventional experimental methods.

2 Methodology

2.1 Database overview

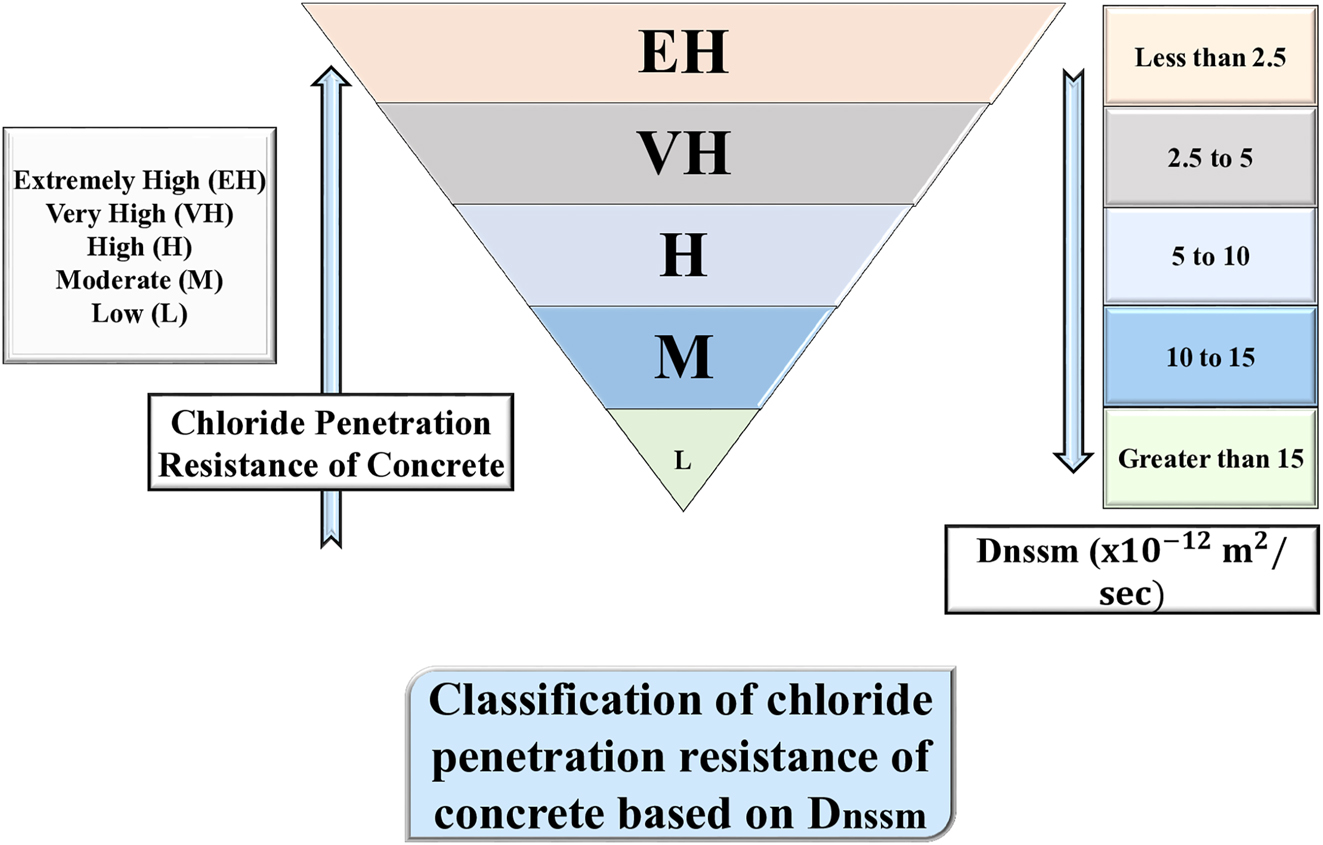

The database comprises 843 data points that capture D nssm values across various types of concrete. This database is collected from two channels: i) academic research projects [36], and ii) publications in international journals [21], 27], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. The D nssm values serve as indicators for evaluating concrete’s ability to withstand chloride ion infiltration, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Chloride penetration resistance.

The dataset comprises diverse concrete classifications, including conventional, lightweight, enhanced-strength, advanced-performance, and self-consolidating concrete. These concrete mixes are characterized by eight attributes that detail the components and their proportions: water-to-binder ratio, quantities of binders (slag, cement, silica fume, lime filler, and fly ash) measured in kg/m3, amounts of fine and coarse aggregates in kg/m3, and levels of chemical additives (air-entraining agents, superplasticizers, and plasticizers) as a percentage of the binder’s weight.

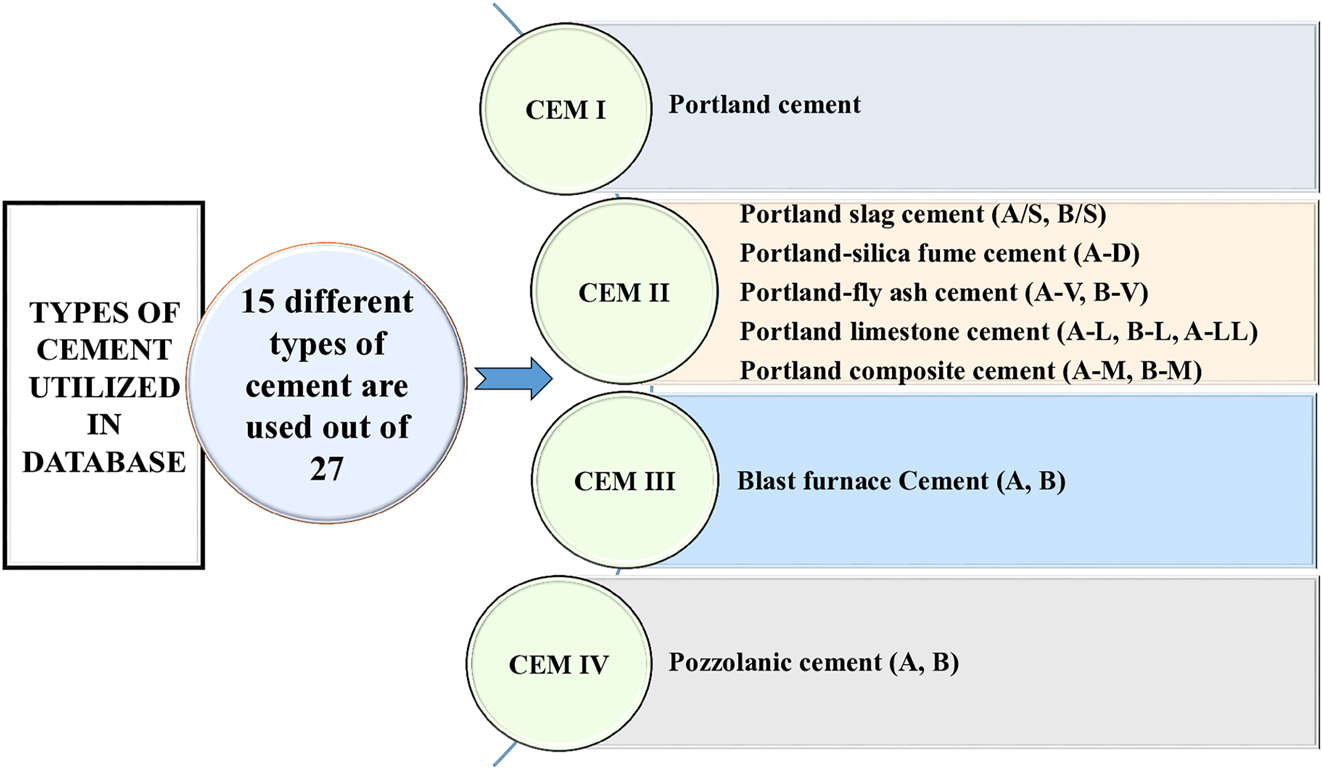

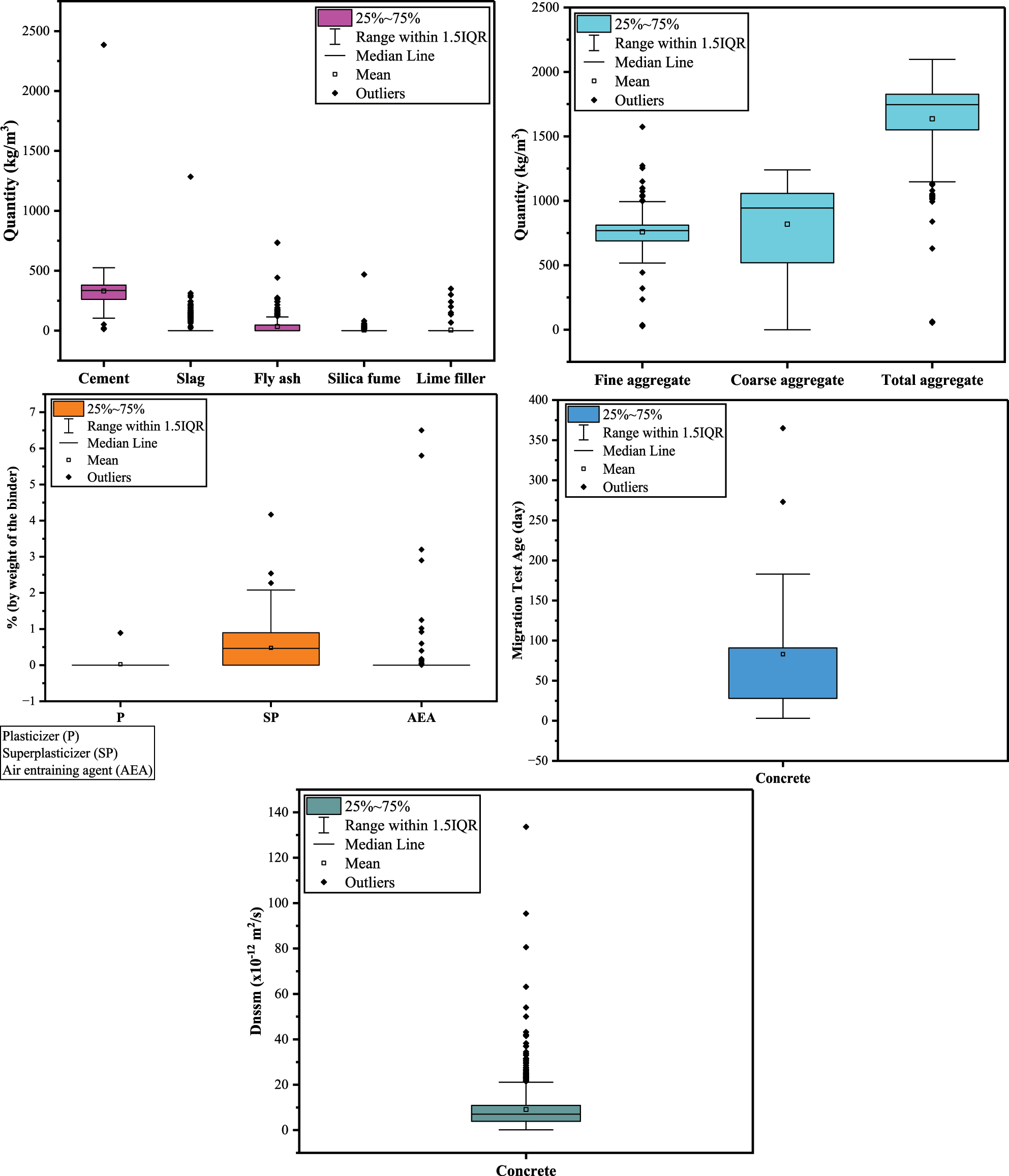

The database encompasses various cement varieties documented in diverse standards as experimental data has been gathered from numerous regions of the world. To ensure uniformity, all cement types are standardized based on the European standard EN 197-1. This standard classifies cement into 27 unique types, organized into five main categories, as depicted in Figure 2. Within the database, there are 15 cement types representing the four primary cement groups as illustrated in Figure 3. Around 57 % of the experiments conducted incorporate supplementary cementitious materials. The water-to-binder ratio spans from 0.19 to 0.65. Within the dataset, admixtures consist of numerous compounds, including superplasticizers containing polycarboxylate ether, naphthalene, melamine sulfonate, and lignosulfonate, as well as air-entraining agents composed of vinsol resin, synthetic surfactants, and fatty acid soap. The statistical distribution of the features is given in Table 1. Further, box plots of the features and D nssm are depicted in Figure 4.

Cement groups (EN 197-1).

Cement types utilized in the database.

Statistical intuitions into the features.

| Statistics | W/B | Water | Cement | Slag | Fly ash | SF | FA | CA | TA | SP | MT age | D nssm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | % (by Wb) | Day | (×10−12 m2/s) | ||

| Mean | 0.42 | 162.3 | 330.07 | 29.3 | 33.9 | 5.28 | 759.06 | 818.5 | 1,636 | 0.48 | 83.06 | 9.1 |

| Median | 0.44 | 164.5 | 334.61 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 768 | 944 | 1746 | 0.47 | 28 | 7.04 |

| Mode | 0.45 | 162 | 360 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 786 | 463.0 | 1,960 | 0 | 28 | 8.8 |

| SD | 0.09 | 54.68 | 134.32 | 85.6 | 81.8 | 19.9 | 183.63 | 307.0 | 323.9 | 0.53 | 95.47 | 9.42 |

| Maximum | 0.65 | 1,049 | 2,384.97 | 1,284 | 735 | 468 | 1,574.1 | 1,240 | 2,097 | 4.17 | 365 | 133.6 |

| Minimum | 0.19 | 8.46 | 13.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27.53 | 0 | 54.04 | 0 | 3 | 0.2 |

| Skewness | −0.02 | 9.74 | 8.32 | 8.23 | 5.14 | 15.4 | −0.47 | −0.86 | −2.33 | 1.25 | 1.83 | 5.4 |

-

SD, standard deviation.

Statistical distribution of the features and label.

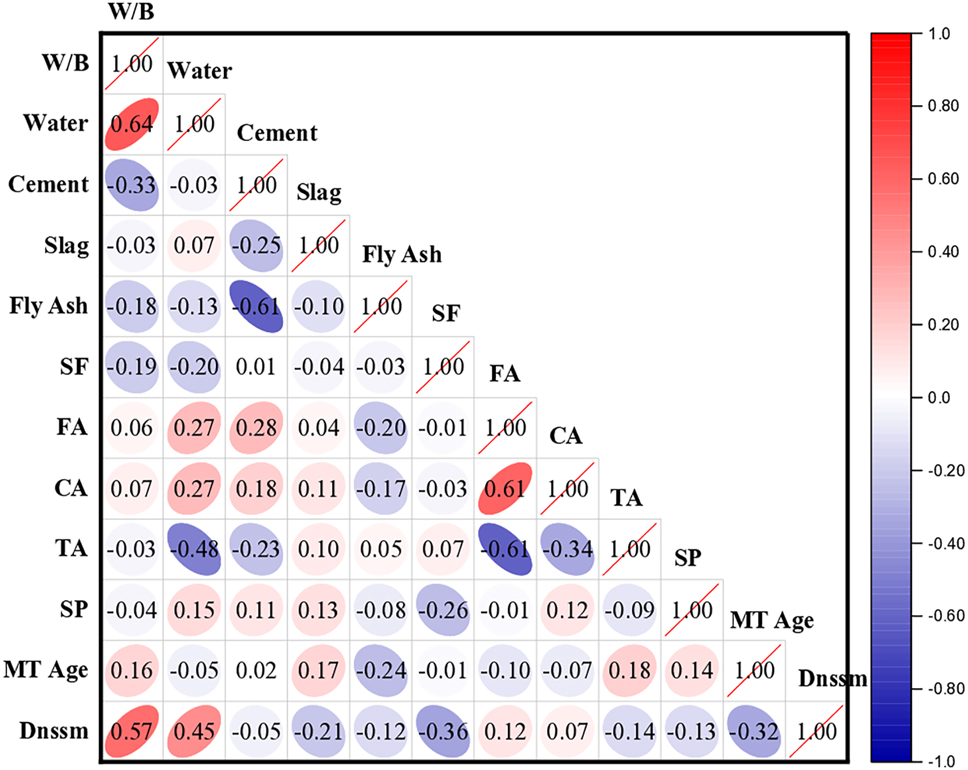

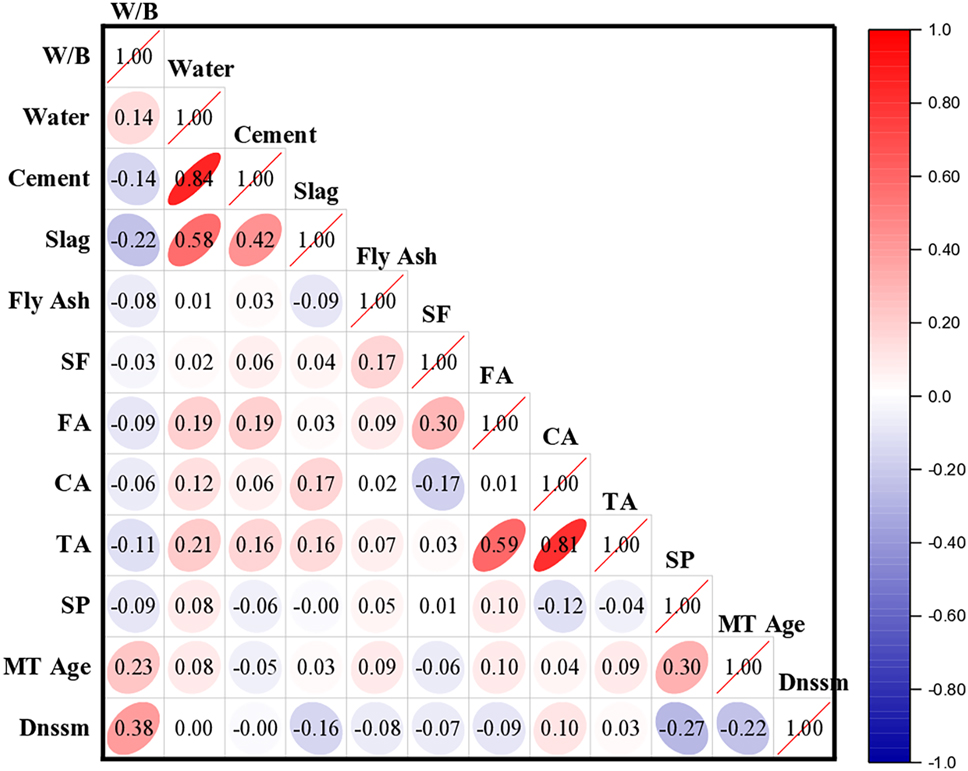

Correlation heatmaps were utilized to evaluate multicollinearity issues. In the Spearman correlation matrix (Figure 5), a notable correlation exists between D nssm and the water-to-binder ratio (W/B), with a coefficient of 0.57. This correlation is followed by water (0.45), fine aggregate (FA, 0.12), and coarse aggregate (CA, 0.07). Additionally, there are negative correlations of −0.36, −0.32, −0.21, −0.14, −0.13, and −0.12 with silica fume (SF), migration test age (MT Age), slag, total aggregate (TA), superplasticizer (SP), and fine aggregate (FA), respectively. Likewise, in the Pearson correlation matrix (Figure 6), W/B exhibits the strongest linear association, with a correlation coefficient of 0.38, followed by CA (0.10) and TA (0.03). Conversely, there are negative correlations of −0.27 and −0.22 with SP and MT Age, respectively. As all features have correlation coefficients below 0.8, multicollinearity is not present.

Spearman correlation heatmap.

Pearson correlation heatmap.

2.2 Data preprocessing

The dataset consisted of 843 data points collected from academic journals and research projects, covering a wide range of concrete mixes. To ensure data quality, errors and duplicates were removed, and missing values were handled using manual and naïve imputation [43], 44]. Box plots were used to detect and remove outliers. Some features, like water, cement, and slag, had highly skewed distributions. Although log transformations were considered to correct this, standardizing the data with StandardScaler was enough to handle the skewness without changing the original meaning of the features.

All input features were scaled to have zero mean and unit variance to improve model stability and performance. Correlation analysis using Pearson and Spearman methods confirmed that all variables had correlation coefficients below 0.8, indicating low multicollinearity. The dataset had a high data-to-variable ratio (76.6), exceeding the recommended minimum and reducing the risk of overfitting [45], 46]. Additionally, 30 % of the data was reserved for testing and validation. For the hybrid models, parameter values for the metaheuristic algorithms (GWO, GTO, FFA, and PSO) were initially based on literature. A preliminary sensitivity analysis was also performed to fine-tune the parameters and ensure good optimization performance for the SVR models.

2.3 Model development

The optimization techniques PSO, GWO, FFA, and GTO were utilized to enhance the predictive performance of the SVR model in determining the D nssm. An overview of the model development process is presented in Figure 7. The key SVR parameters include the radial basis function (RBF) kernel width (g) and penalty factor (C), each constrained within the range of 0.01–100. The parameter configurations for the ML models are as follows: In FFA, the absorption coefficient (α) is set to 0.2, the randomization parameter (rand) is 0.93, the initial attractiveness coefficient (β 0) is 2, and the light intensity absorption coefficient (γ) is 1. For GWO, the control variable (a) reduces in a linear fashion from an initial value of 2 down to 0. In PSO, the maximum velocity (V max) is defined as 6, while the minimum (w min) and maximum (w max) inertia weights are 0.2 and 0.8, respectively. Additionally, the cognitive coefficient (c 1) and social coefficient (c 2) are assigned values of 1.6 and 1.8, respectively, to regulate swarm behaviour during optimization. The GTO algorithm utilizes 20 candidate solutions per iteration, with a maximum of 50 optimization iterations. A reproducibility seed of 42 ensures consistency in results, while the perturbation range is set at ±0.1. The candidate solution adjustment follows a random uniform perturbation mechanism based on both exploitation and exploration strategies. These optimized parameter settings enhance the efficiency of the SVR model in predicting the response parameter.

Overview of hybrid model development.

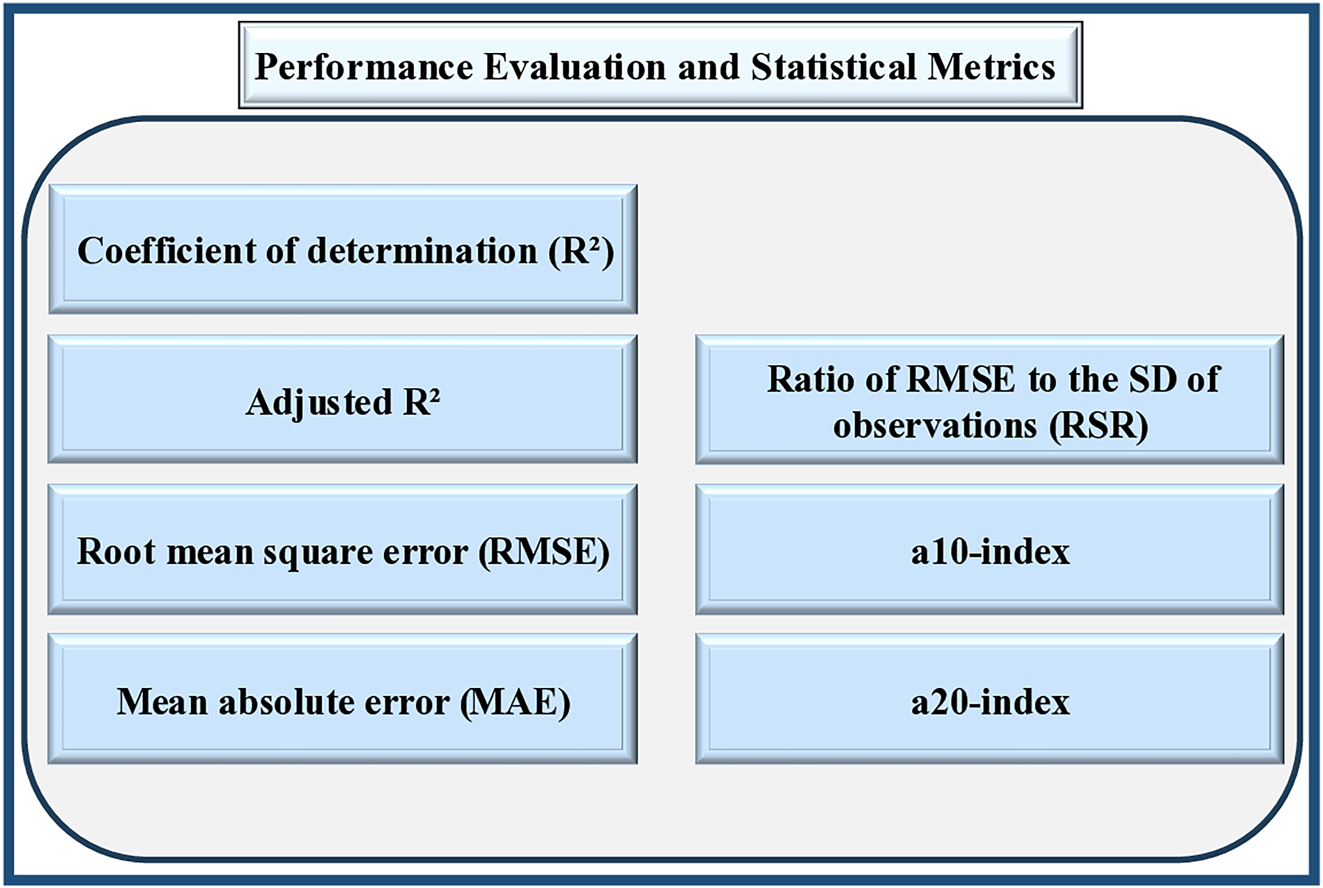

2.4 Assessment of model effectiveness

Every model is subjected to a comprehensive assessment procedure, which involves computing a range of performance indicators to evaluate its effectiveness (Figure 8). The mathematical formulations for these statistical indices are provided in Eqs. (1–6).

Where P i depicts the actual value, while Q i represents the anticipated value, where N refers to the total observations, and K n represents the number of predictors. The letter with a bar on top represents the average values. R20 denotes the anticipated number of values falling within the ratio range of 0.90–1.20 for experimental-to-predicted values, whereas R10 represents the count of values within the range of 0.80–1.10.

Performance indicators for assessing model efficacy.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Performance analysis

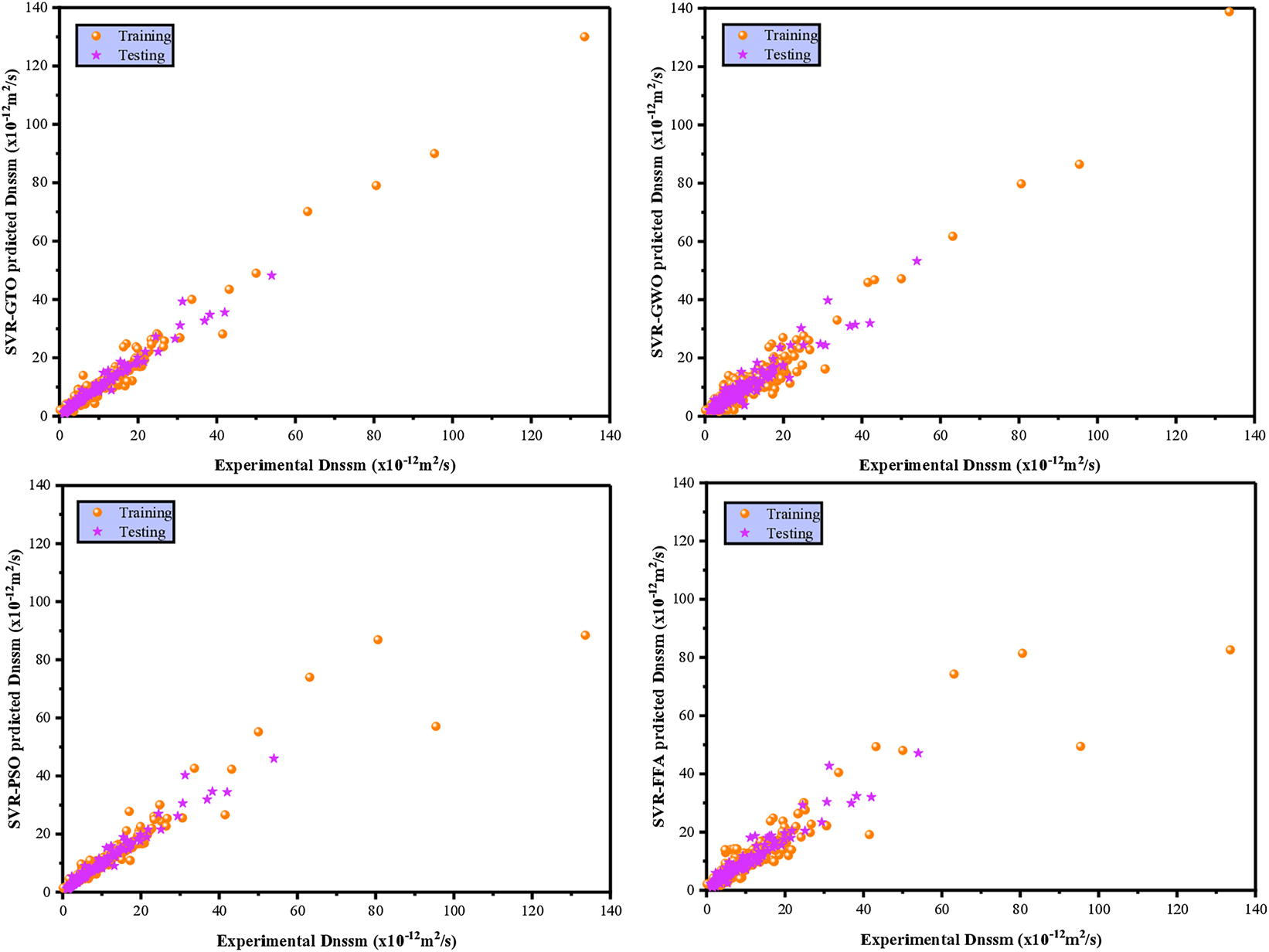

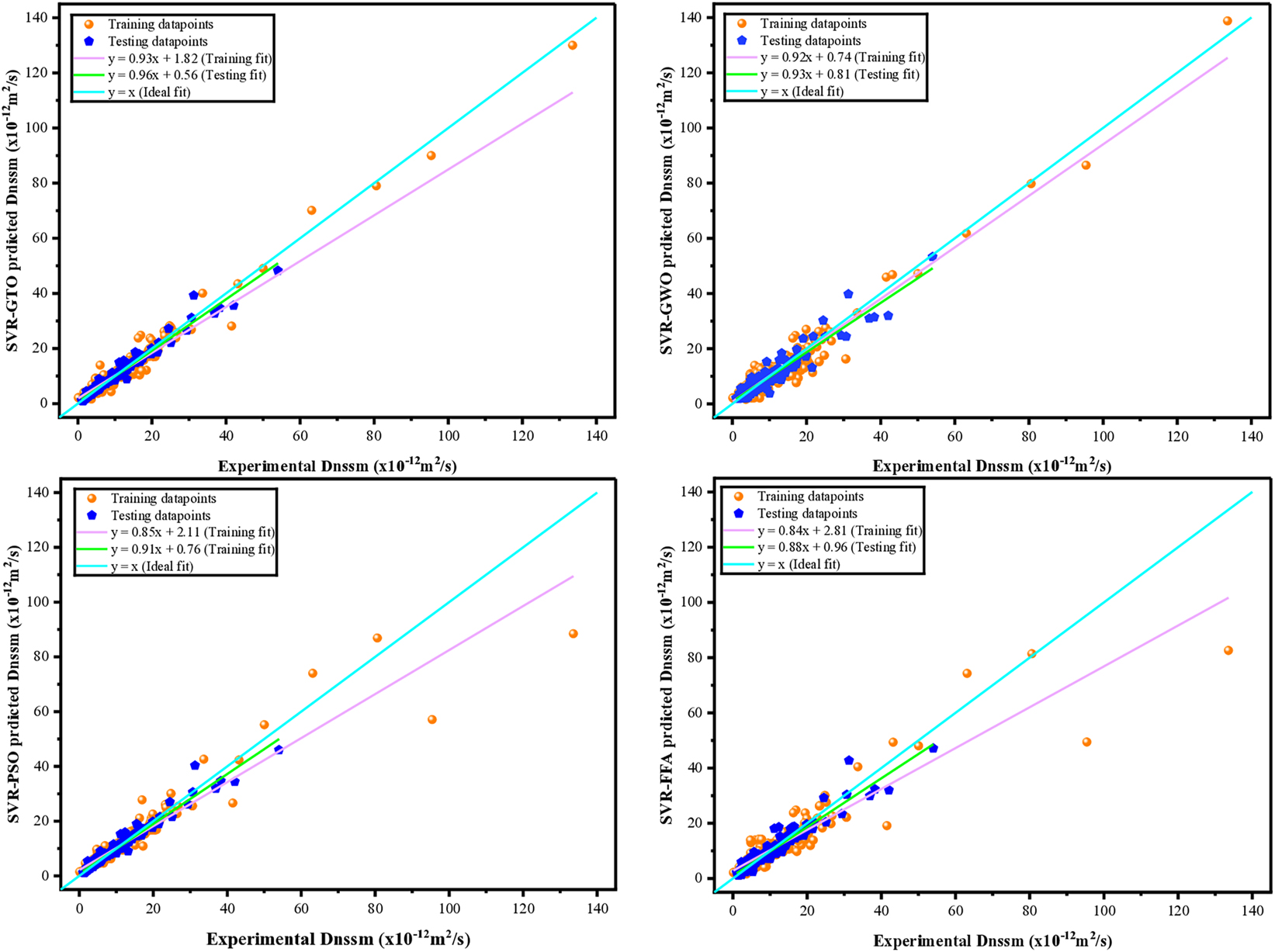

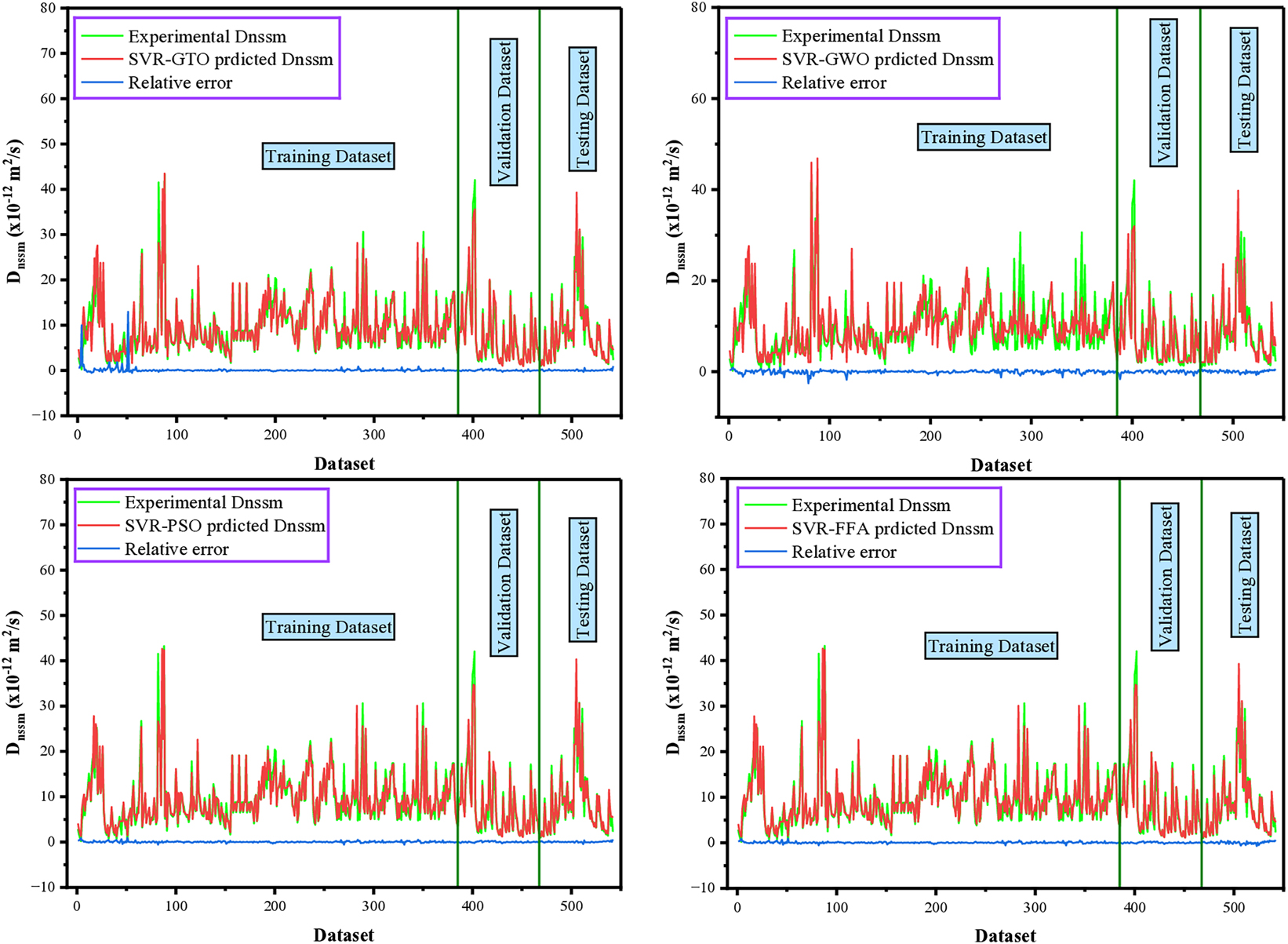

Regression analysis is crucial for evaluating the predictive accuracy of ML models by quantifying the alignment between predicted and observed values (Figure 9). A regression coefficient close to 1, particularly above 0.8, demonstrates the model’s effectiveness in capturing complex relationships [47], 48]. The obtained regression slopes validate the performance of the suggested SVR-based hybrid models (Figure 10). During the training phase, SVR-GTO exhibited the highest slope (0.93), followed by SVR-GWO (0.92), while SVR-PSO and SVR-FFA both achieved a slope of 0.85. In the testing phase, the regression slopes further improved, with SVR-GTO increasing to 0.96, SVR-GWO reaching 0.93, SVR-PSO attaining 0.91, and SVR-FFA maintaining a strong slope of 0.88. These results confirm the robustness of the models in estimating chloride penetration resistance in concrete, ensuring minimal deviation from experimental values and reinforcing their applicability in engineering practices. Additionally, Figure 11 presents an evaluation of the prediction accuracy by comparing actual and predicted values, along with the corresponding relative errors.

Scatter plots comparing predicted and actual values.

Regression analysis of the developed models.

Evaluation of prediction accuracy using actual, predicted, and relative error values.

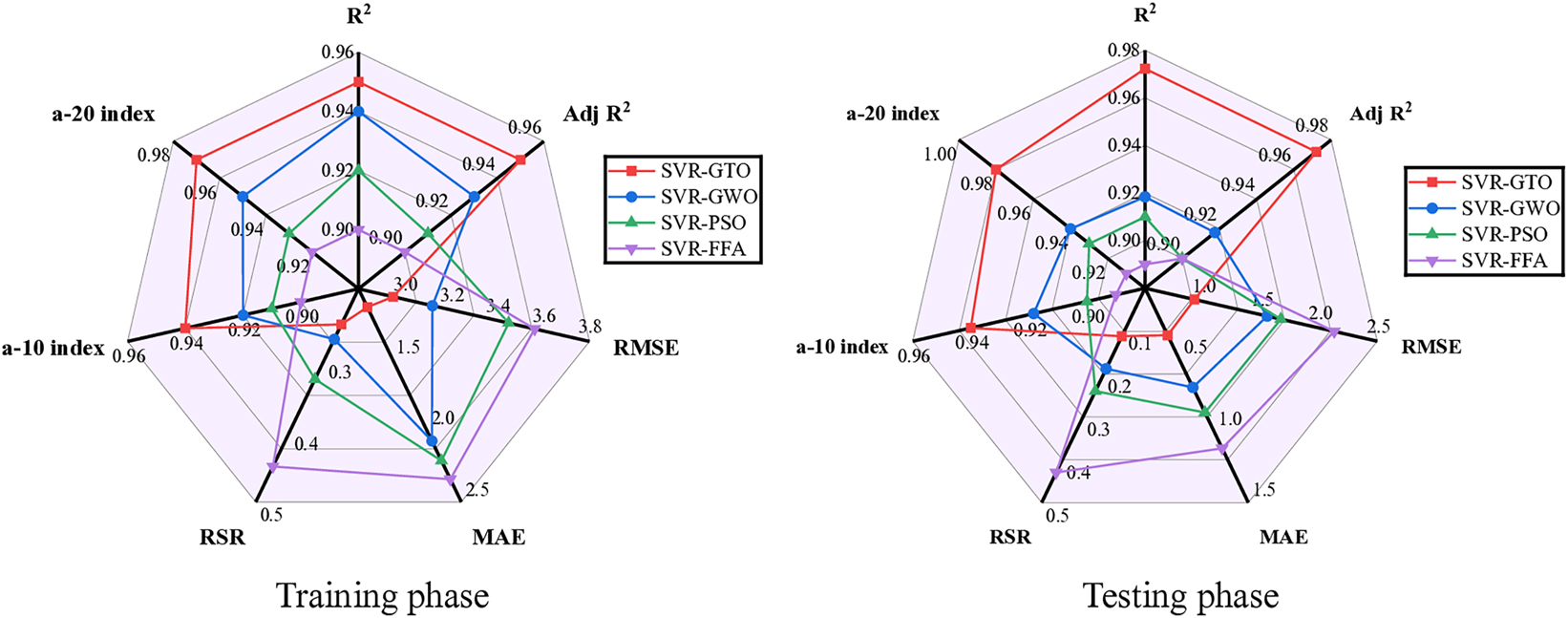

3.2 Assessment of model effectiveness

The statistical assessment of the ML models was conducted utilizing key performance indicators for both the training and testing phases (Table 2). In the training phase, SVR-GTO achieved the highest accuracy with an R 2 of 0.95 and an RMSE of 2.95, followed closely by SVR-GWO (R 2 = 0.94, RMSE = 3.12). SVR-PSO and SVR-FFA demonstrated slightly lower performance, with R 2 values of 0.92 and 0.90, and RMSE values of 3.45 and 3.56, respectively.

Overview of performance metrics for the proposed models.

| Phase | Models | R 2 | Adj R 2 | RMSE | MAE | RSR | a-10 index | a-20 index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | SVR-GTO | 0.95 | 0.95 | 2.95 | 1.13 | 0.25 | 0.94 | 0.97 |

| SVR-GWO | 0.94 | 0.93 | 3.12 | 2.07 | 0.27 | 0.92 | 0.95 | |

| SVR-PSO | 0.92 | 0.91 | 3.45 | 2.21 | 0.33 | 0.91 | 0.93 | |

| SVR-FFA | 0.90 | 0.90 | 3.56 | 2.34 | 0.45 | 0.90 | 0.92 | |

| Testing | SVR-GTO | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.94 | 0.98 |

| SVR-GWO | 0.92 | 0.92 | 1.55 | 0.69 | 0.19 | 0.92 | 0.94 | |

| SVR-PSO | 0.91 | 0.90 | 1.67 | 0.87 | 0.24 | 0.90 | 0.93 | |

| SVR-FFA | 0.89 | 0.90 | 2.13 | 1.12 | 0.43 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

In the testing phase, SVR-GTO again outperformed other models, attaining the highest R 2 of 0.97 and the lowest RMSE of 0.93, indicating strong generalization. SVR-GWO maintained solid performance (R 2 = 0.92, RMSE = 1.55), while SVR-PSO and SVR-FFA yielded R 2 values of 0.91 and 0.89, and RMSE values of 1.67 and 2.13, respectively. These findings confirm the superior accuracy and reliability of the SVR-GTO model in predicting chloride penetration resistance (Figure 12). The superior performance of SVR-GTO can be attributed to the unique exploration–exploitation balance of the GTO algorithm. GTO simulates the complex social behavior and dynamic movement patterns of gorilla troops, enabling it to effectively avoid local optima and explore the solution space more thoroughly. Its adaptive strategy and strong global search capability make it particularly suitable for high-dimensional, nonlinear problems such as predicting chloride diffusion in concrete.

Spider plots of statistical indicator scores.

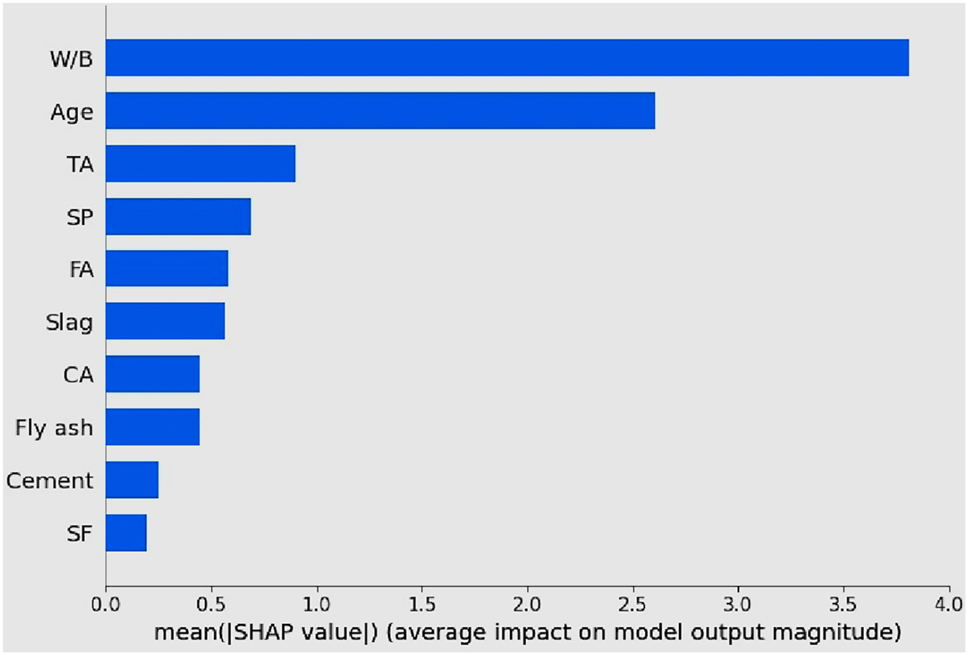

3.3 SHAP interpretation

The relative importance of input features in predicting D nssm is illustrated in Figure 13 through SHAP analysis. The W/B exhibited the highest mean SHAP value (+3.8), underscoring its dominant influence on model predictions. MT Age followed with a mean value of +2.6, indicating its strong contribution to chloride resistance. TA and SP also demonstrated notable impacts, with SHAP values of +0.8 and slightly lower, respectively. Furthermore, fly ash and slag each contributed with a value of +0.6, while CA, cement, and SF showed smaller but meaningful effects, with SHAP values of 0.5, 0.3, and 0.2, respectively. These findings highlight the critical roles of mixture composition and curing age in determining chloride ingress behavior in concrete.

Mean SHAP plot: assessing feature’s significance.

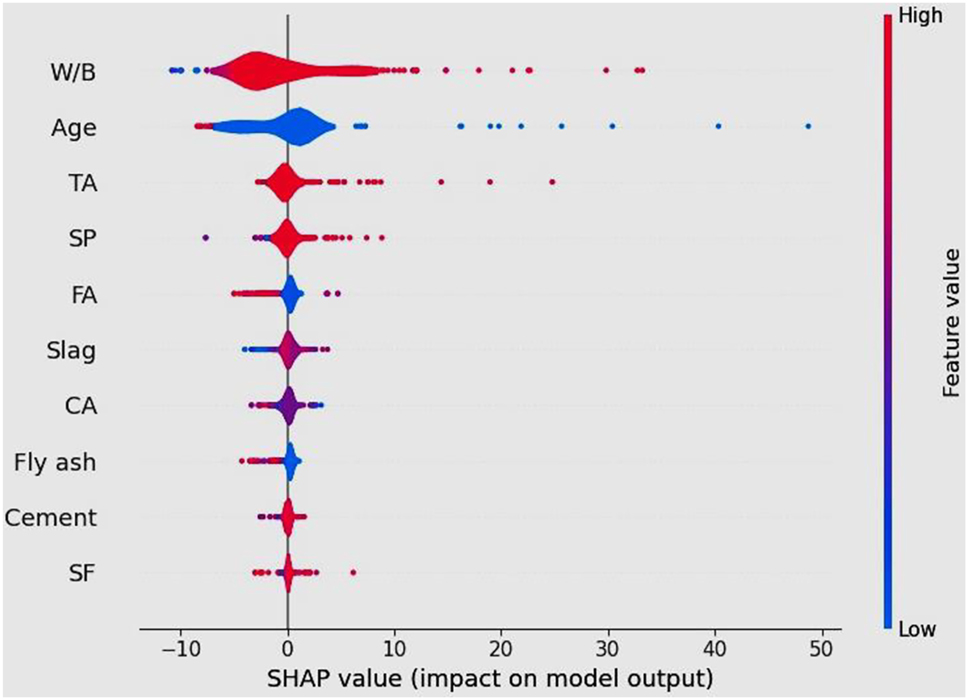

A rise in the W/B ratio is associated with a positive SHAP value of approximately +35, indicating that higher W/B ratios contribute positively to D nssm (Figure 14). Conversely, a decrease in the W/B ratio depicts a negative SHAP value (around −10), suggesting a detrimental effect on D nssm. The MT Age also plays a significant role, with higher durations showing negative SHAP values (around −8) and shorter durations exhibiting positive SHAP values (around +48). This implies that longer curing periods negatively impact D nssm, while shorter durations have a positive influence. Similarly, higher FA quantities show negative SHAP values (−5), indicating adverse effects on D nssm prediction, while lower FA amounts exhibit positive SHAP values (+3), implying beneficial impacts.

Impact of variables: SHAP summary visualization.

D nssm shows contrasting trends with CA and TA content. Specifically, increasing CA content leads to a decrease in D nssm, indicating improved resistance to chloride penetration. This occurs because larger, well-graded coarse aggregates disrupt the continuity of the cement paste, increasing the tortuosity of the diffusion path and effectively reducing the permeability of the concrete [49]. In contrast, while moderate increases in TA, which includes both fine and coarse aggregates, can improve the concrete matrix, very high TA levels lead to an increase in D nssm. This rise may be attributed to the excessive volume of fine aggregates within the total aggregate fraction, which increases the interfacial transition zones (ITZs). Since ITZs are more porous than bulk paste, their expansion at very high TA contents can create easier pathways for chloride ions, thereby increasing chloride diffusivity. Hence, while coarse aggregate contributes positively to durability by blocking ion transport, an overly large total aggregate content, largely influenced by fine aggregate and the associated ITZ volume, can counteract this benefit and increase chloride permeability. This highlights the importance of optimizing both aggregate grading and overall aggregate volume to balance tortuosity effects with ITZ-induced permeability for enhanced concrete durability.

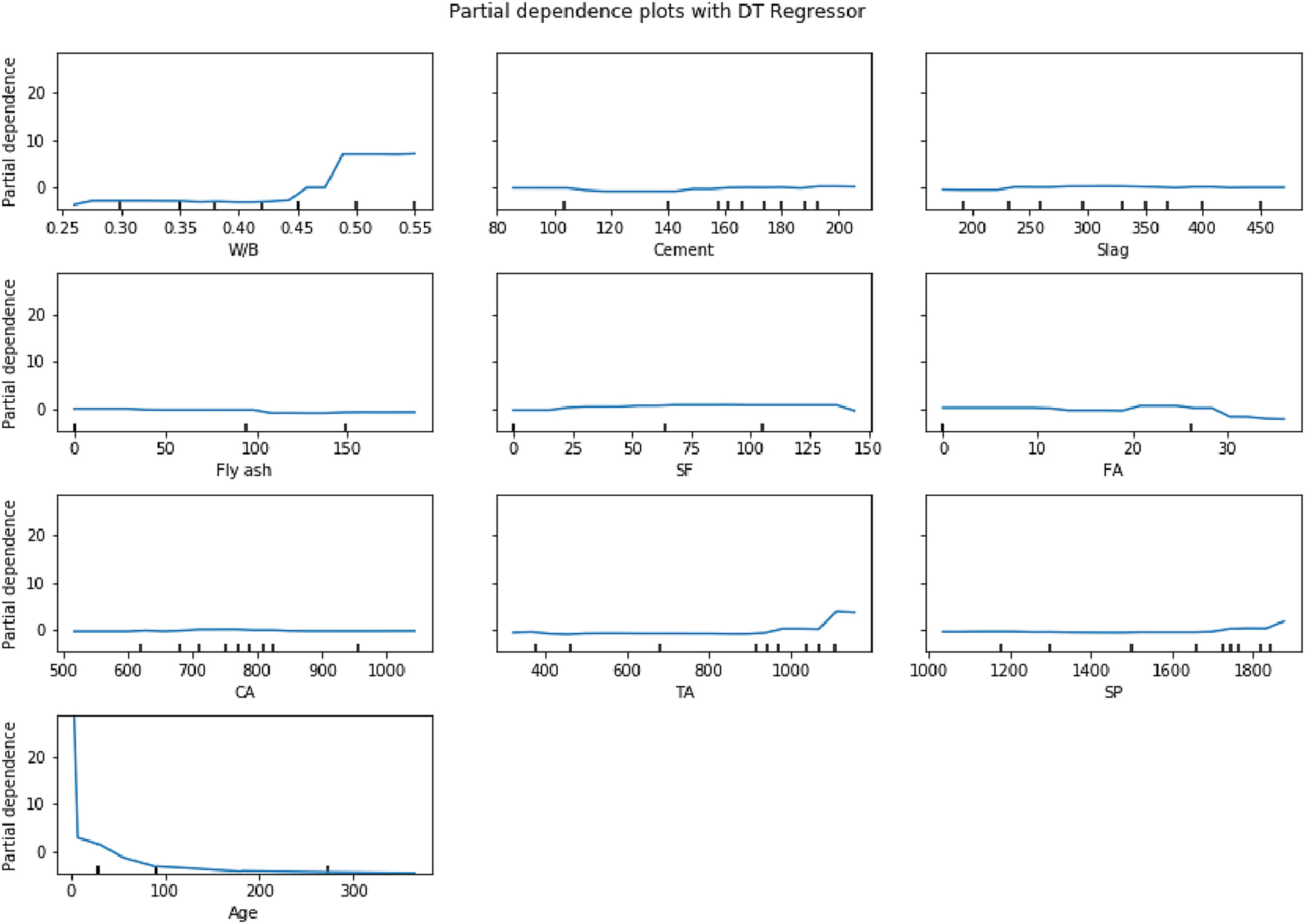

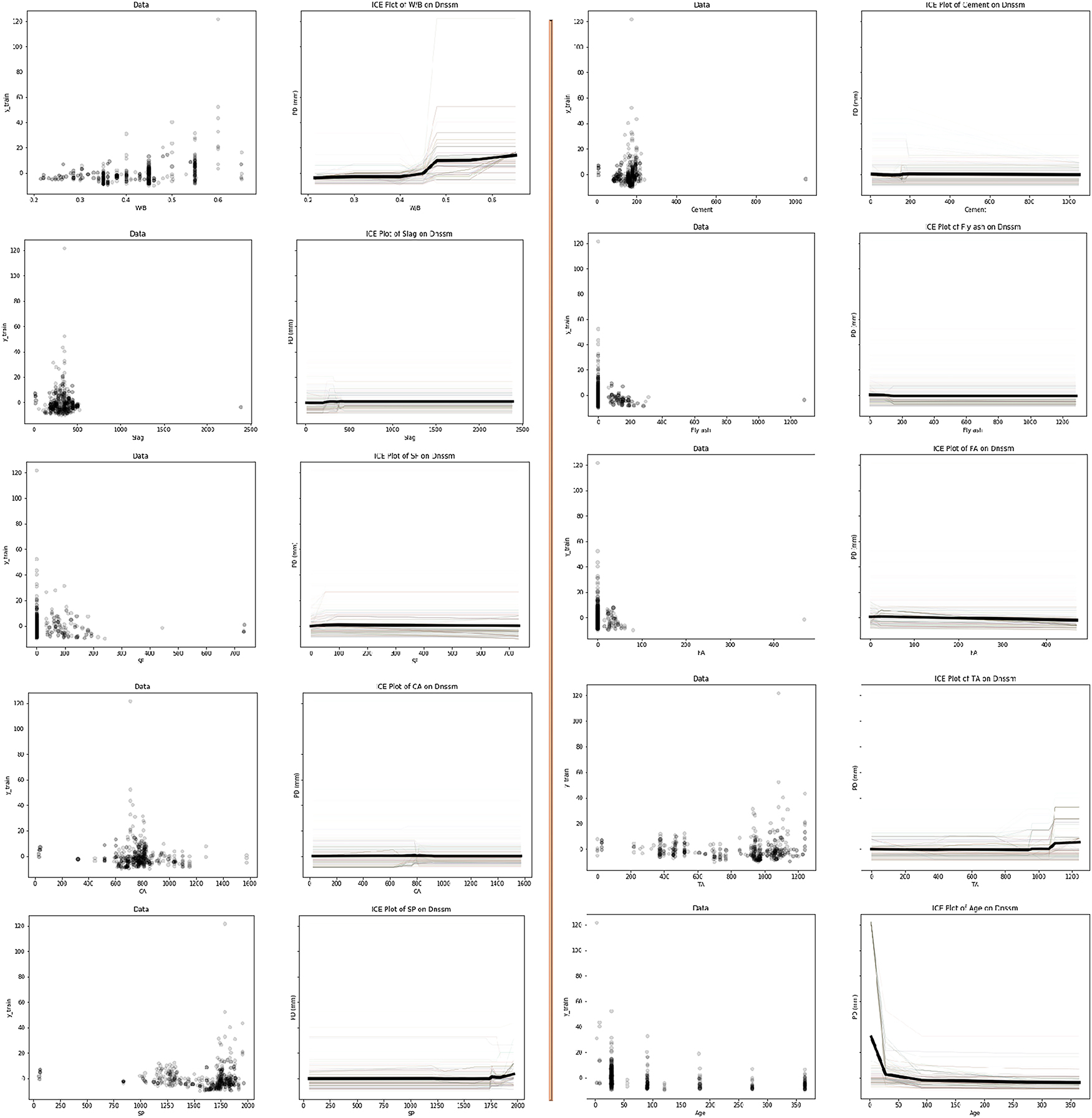

3.4 ICE and PDP interpretation

The D nssm of concrete exhibits diverse trends across different material parameters (Figure 15). Initially, D nssm increases with higher W/B ratios but only for a limited range, after which it stabilizes until approximately 0.44. Subsequently, there is a rapid increase in D nssm from 0.44 to 0.49, maintaining a constant value up to 0.55. Similarly, D nssm remains consistent up to 102 kg/m3 of cement, beyond which it experiences a slight decrease until approximately 145 kg/m3, remaining relatively constant thereafter. Additionally, D nssm remains constant up to 225 kg/m3 and then slightly decreases. Furthermore, D nssm shows a slight decrease up to 90 kg/m3, followed by a more significant decrease up to 100 kg/m3, after which it remains constant. D nssm almost remains constant with an increase in SF but decreases around 112 kg/m3. It also decreases slightly up to 18 kg/m3of FA, then shows a slight rise and decreases again. With an increase in CA content, D nssm remains almost constant and slightly decreases initially but remains constant up to 980 kg/m3, after which it increases. Moreover, D nssm initially experiences a rapid fall with a rise in MT age and continues to decrease with further increases in MT age. The PDP analysis reveals that D nssm rises sharply when the TA content exceeds approximately 1,100 kg/m3, consistent with the SHAP findings.

PDP analysis.

The results of this study offer clear guidance for optimizing concrete mix designs to enhance durability against chloride ingress. Maintaining a low W/B ratio, ideally below 0.44, is a key factor in minimizing chloride diffusivity. A moderate cement content, around 102–145 kg/m3, appears sufficient for maintaining strength without increasing permeability. Incorporating SF up to 112 kg/m3 improves matrix densification, thereby reducing D nssm. Increasing CA content up to 980 kg/m3 is beneficial, as it enhances tortuosity and obstructs ion transport pathways. However, care must be taken with TA content. When TA exceeds 1,100 kg/m3, D nssm may increase due to a larger volume of ITZs, which are more porous and facilitate chloride movement. Additionally, extending the MT age shows that prolonged curing significantly improves chloride resistance. By carefully adjusting these key parameters, engineers can design concrete mixes with better long-term performance in chloride-rich environments.

4 Comparison with existing models

ML has been increasingly integrated with analytical and numerical methods to enhance the prediction of complex structural behaviors and material properties. Among boosting algorithms used to predict the homogenized stiffness of fiber-reinforced composites, XGBoost achieved the highest accuracy [50]. For structural stability problems, a hybrid PSO-XGBoost model effectively estimated the buckling loads of columns with variable cross-sections, demonstrating near-perfect R 2 values and improved interpretability via SHAP analysis [51]. Similarly, ensemble models such as light gradient boosting (LGB) outperformed other techniques in predicting the buckling behavior of functionally graded nanobeams [52]. In concrete-related applications, ANN consistently exhibited superior predictive performance over traditional methods such as linear regression and decision trees [53]. Additionally, bagging regressors (BR) yielded the most accurate predictions in estimating wear depth in fly ash concrete [54]. For high-performance concrete, multilayer perception (MLP) showed superior predictive accuracy [55]. Table 3 presents a comparative summary of the models employed in previous literature and those adopted in the current study.

Comparative summary of ML models utilized in existing literature and the present study.

| Reference | Best model | Model interpretation | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| [50] | XGBoost | 0.99 | |

| [51] | PSO-XGBoost | SHAP | 0.996 |

| [52] | LGB | 0.999 | |

| [53] | ANN | Sensitivity analysis | 0.99 |

| [54] | BR | SHAP | 0.99 |

| [55] | MLP | 0.912 | |

| Current study | SVR-GTO | SHAP, ICE, and PDP | 0.97 |

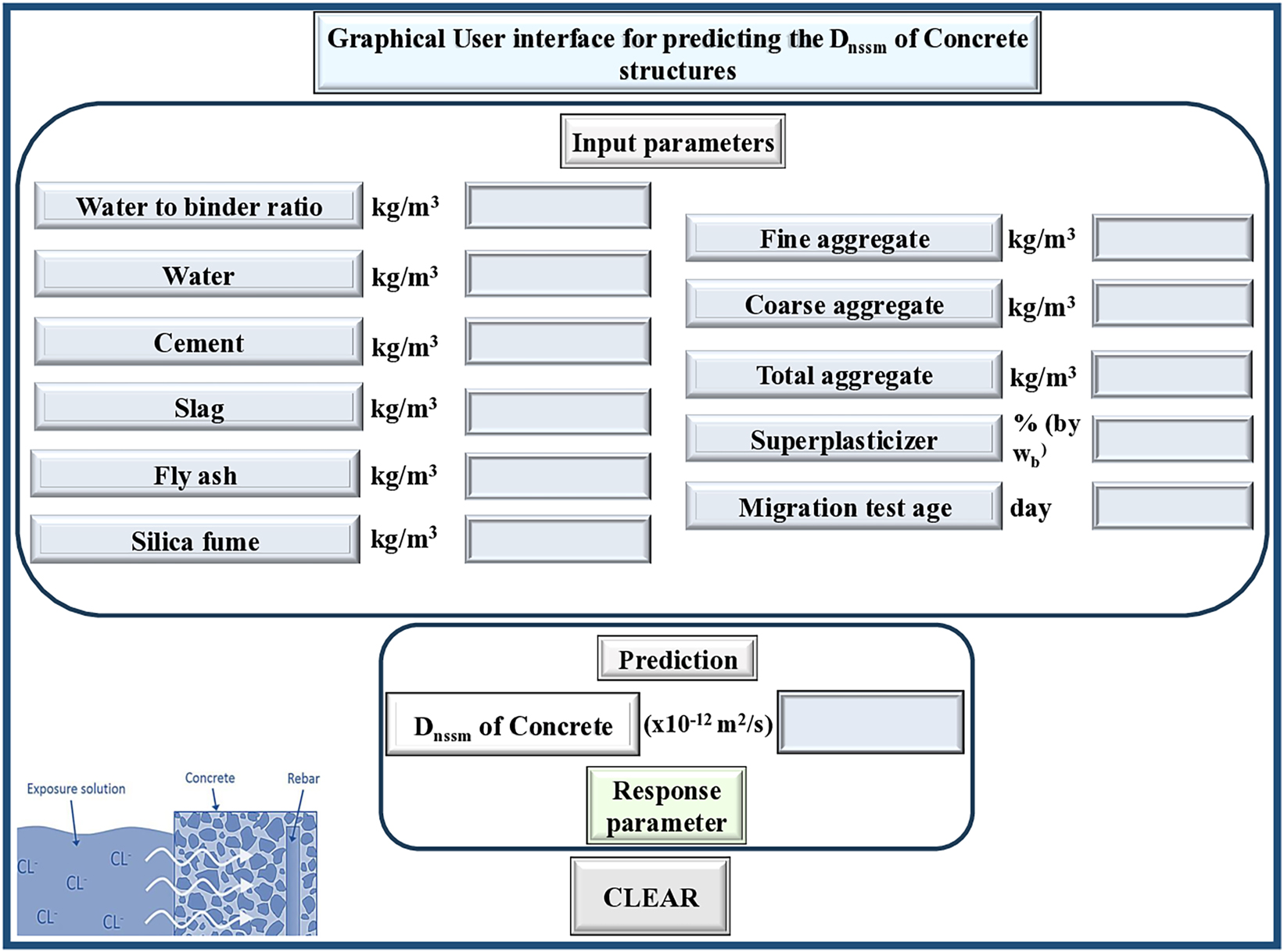

5 Graphical user interface (GUI)

An interactive GUI, depicted in Figure 17, was designed to streamline the prediction of the D nssm of concrete. This innovative tool eliminates reliance on traditional labor-intensive laboratory testing, enabling rapid and accurate assessment of chloride penetration resistance. By inputting key parameters, users can efficiently obtain precise predictions of the migration coefficient, a critical indicator of concrete durability in chloride-exposed environments. The GUI, driven by advanced ML models, provides a practical and easy-to-use tool for researchers and professionals to assess the durability of concrete structures. This interface represents a significant step forward in forecasting chloride resistance, supporting the development of long-lasting, resilient infrastructure in chloride-rich conditions (Figure 17).

ICE analysis.

GUI

6 Limitations and research directions for future

To make ML models more reliable, it is important to conduct experiments in controlled environments and collect data from a consistent, real-world source. This approach would improve dataset consistency and enhance the accuracy and reliability of ML models. The dataset, while comprehensive, may not fully represent all concrete types or environmental conditions, such as freeze-thaw cycles or varying chloride sources. This may limit the generalizability of the models to new scenarios. Additionally, future research should include additional predictors to assess the chloride resistance of concrete. For future research, deep learning techniques could be explored by expanding the dataset size to provide more comprehensive information, improving the model’s generalization and predictive performance.

7 Conclusions

This study explored advanced hybrid ML techniques to predict the D nssm of concrete, a key indicator of chloride penetration resistance. SVR was combined with four metaheuristic optimization algorithms: GTO, GWO, PSO, and FFA to enhance predictive accuracy. The primary outcomes of the study are succinctly outlined below:

SVR-GTO attained the highest R 2 of 0.97 and the minimum RMSE of 0.93, demonstrating superior robustness and generalization capability, while SVR-GWO also exhibited strong predictive efficacy with an R 2 of 0.92 and an RMSE of 1.55; in comparison, SVR-PSO and SVR-FFA recorded slightly lower R 2 of 0.91 and 0.89, with RMSE values of 1.67 and 2.13, respectively.

The analysis underscored the critical significance of the W/B ratio, MT Age, and TA in accurately estimating the chloride penetration resistance of concrete. Specifically, higher values of W/B and TA are associated with increased D nssm values, indicating reduced chloride resistance in concrete. Conversely, greater MT Age corresponds to lower D nssm values, signifying higher chloride resistance in concrete structures.

A GUI was created to streamline the estimation of the D nssm of concrete, eliminating the need for traditional, labor-intensive laboratory testing. The developed GUI, driven by advanced ML algorithms, provides a practical and easy-to-use tool for researchers and professionals to evaluate the durability of concrete structures.

-

Funding information: This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R435), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

-

Author contribution: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

1. Liu, J, Xing, F, Dong, B, Ma, H, Pan, D. Study on surface permeability of concrete under immersion. Materials (Basel) 2014;7:876–86. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma7020876.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

2. Vicente, C, Castela, AS, Neves, R, Montemor, MF. Assessment of the influence of concrete modification in the water uptake/evaporation kinetics by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Electrochim Acta 2017;247:50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2017.06.168.Search in Google Scholar

3. Dong, BQ, Qiu, QW, Xiang, JQ, Huang, CJ, Xing, F, Han, NX, et al.. Electrochemical impedance measurement and modeling analysis of the carbonation behavior for cementititous materials. Constr Build Mater 2014;54:558–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.12.100.Search in Google Scholar

4. Dong, B, Qiu, Q, Gu, Z, Xiang, J, Huang, C, Fang, Y, et al.. Characterization of carbonation behavior of fly ash blended cement materials by the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy method. Cem Concr Compos 2016;65:118–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2015.10.006.Search in Google Scholar

5. Dong, B, Qiu, Q, Xiang, J, Huang, C, Xing, F, Han, N. Study on the carbonation behavior of cement mortar by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Materials (Basel) 2014;7:218–31. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma7010218.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

6. Dong, B, Qiu, Q, Xiang, J, Huang, C, Sun, H, Xing, F, et al.. Electrochemical impedance interpretation of the carbonation behavior for fly ash-slag-cement materials. Constr Build Mater 2015;93:933–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.05.066.Search in Google Scholar

7. Qiu, Q, Gu, Z, Xiang, J, Huang, C, Hong, S, Xing, F, et al.. Influence of slag incorporation on electrochemical behavior of carbonated cement. Constr Build Mater 2017;147:661–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.008.Search in Google Scholar

8. Yu, D, Guan, B, He, R, Xiong, R, Liu, Z. Sulfate attack of Portland cement concrete under dynamic flexural loading: a coupling function. Constr Build Mater 2016;115:478–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.02.052.Search in Google Scholar

9. Gong, J, Cao, J, Wang, YF. Effects of sulfate attack and dry-wet circulation on creep of fly-ash slag concrete. Constr Build Mater 2016;125:12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.08.023.Search in Google Scholar

10. Tang, SW, Yao, Y, Andrade, C, Li, ZJ. Recent durability studies on concrete structure. Cem Concr Res 2015;78:143–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.05.021.Search in Google Scholar

11. Bernal, J, Fenaux, M, Moragues, A, Reyes, E, Gálvez, JC. Study of chloride penetration in concretes exposed to high-mountain weather conditions with presence of deicing salts. Constr Build Mater 2016;127:971–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.09.148.Search in Google Scholar

12. Berrocal, CG, Lundgren, K, Löfgren, I. Corrosion of steel bars embedded in fibre reinforced concrete under chloride attack: state of the art. Cem Concr Res 2016;80:69–85.10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.10.006Search in Google Scholar

13. Liu, J, Qiu, Q, Chen, X, Xing, F, Han, N, He, Y, et al.. Understanding the interacted mechanism between carbonation and chloride aerosol attack in ordinary Portland cement concrete. Cem Concr Res 2017;95:217–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2017.02.032.Search in Google Scholar

14. Liu, JC, Wang, TJ, Sung, LC, Kao, PF, Yang, TY, Hao, WR, et al.. Influenza vaccination reduces hemorrhagic stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation: a population-based cohort study. Int J Cardiol 2017;232:315–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.12.074.Search in Google Scholar PubMed

15. Montemor, MF, Simões, AMP, Ferreira, MGS. Chloride-induced corrosion on reinforcing steel: from the fundamentals to the monitoring techniques. Cem Concr Compos 2003;25:491–502.10.1016/S0958-9465(02)00089-6Search in Google Scholar

16. Tadayon, MH, Shekarchi, M, Tadayon, M. Long-term field study of chloride ingress in concretes containing pozzolans exposed to severe marine tidal zone. Constr Build Mater 2016;123:611–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.07.074.Search in Google Scholar

17. Liu, J, Ou, G, Qiu, Q, Xing, F, Tang, K, Zeng, J. Atmospheric chloride deposition in field concrete at coastal region. Constr Build Mater 2018;190:1015–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.09.094.Search in Google Scholar

18. Fitzgerald, JW. Marine aerosols: a review. Atmos Environ Part A, Gen Top 1991;25:533–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/0960-1686(91)90050-h.Search in Google Scholar

19. Houska, C, Houska, C. Deicing salt – recognizing the corrosion threat, TMR consulting. Pittsburgh, PA USA; 1990:1990 p.Search in Google Scholar

20. Liu, J, Ou, G, Qiu, Q, Chen, X, Hong, J, Xing, F. Chloride transport and microstructure of concrete with/without fly ash under atmospheric chloride condition. Constr Build Mater 2017;146:493–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.04.018.Search in Google Scholar

21. Pontes, J, Bogas, JA, Real, S, Silva, A. The rapid chloride migration test in assessing the chloride penetration resistance of normal and lightweight concrete. Appl Sci 2021;11:7251. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11167251.Search in Google Scholar

22. Ann, KY, Ahn, JH, Ryou, JS. The importance of chloride content at the concrete surface in assessing the time to corrosion of steel in concrete structures. Constr Build Mater 2009;23:239–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2007.12.014.Search in Google Scholar

23. Tipu, RK, Panchal, VR, Pandya, KS. Multi-objective optimized high-strength concrete mix design using a hybrid machine learning and metaheuristic algorithm. Asian J Civ Eng 2023;24:849–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-022-00535-8.Search in Google Scholar

24. Kumar Tipu, R, Batra, V, Suman, PKS, Panchal, VR. Shear capacity prediction for FRCM-strengthened RC beams using hybrid ReLU-Activated BPNN model. Structures 2023;58:105432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2023.105432.Search in Google Scholar

25. Tipu, RK, Panchal, VR, Pandya, KS. Enhancing chloride concentration prediction in marine concrete using conjugate gradient-optimized backpropagation neural network. Asian J Civ Eng 2024;25:637–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-023-00801-3.Search in Google Scholar

26. Tipu, RK, Batra, V, Suman, PVR, Pandya, KS. Predictive modelling of surface chloride concentration in marine concrete structures: a comparative analysis of machine learning approaches. Asian J Civ Eng 2024;25:1443–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42107-023-00854-4.Search in Google Scholar

27. Marks, M, Jóźwiak-NiedzWiedzka, D, Glinicki, MA. Automatic categorization of chloride migration into concrete modified with CFBC ash. Comput Concr 2012;9:375–87.10.12989/cac.2012.9.5.375Search in Google Scholar

28. Hodhod, OA, Ahmed, HI. Developing an artificial neural network model to evaluate chloride diffusivity in high performance concrete. HBRC J 2013;9:15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hbrcj.2013.04.001.Search in Google Scholar

29. Yao, L, Ren, L, Gong, G. Evaluation of chloride diffusion in concrete using PSO-BP and BP neural network. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2021;687:012037. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/687/1/012037.Search in Google Scholar

30. Delgado, JMPQ, Silva, FAN, Azevedo, AC, Silva, DF, Campello, RLB, Santos, RL. Artificial neural networks to assess the useful life of reinforced concrete elements deteriorated by accelerated chloride tests. J Build Eng 2020;31:101445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101445.Search in Google Scholar

31. Tariq, A, Uzun, B, Akpınar, M, Yaylı, MÖ, Deliktaş, B. Size dependent dynamics of a bi-directional functionally graded nanobeam via machine learning methods. Adv Nano Res 2025;18:33–52.Search in Google Scholar

32. Lourenço, R, Tariq, A, Georgieva, P, Andrade-Campos, A, Deliktaş, B. On the use of physics-based constraints and validation KPI for data-driven elastoplastic constitutive modelling. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2025;437:117743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2025.117743.Search in Google Scholar

33. Safaeian Hamzehkolaei, N, Ghavaminejad, S, Barkhordari, MS. Predictive model of bond strength in reinforced concrete structures: a hybrid metaheuristic-optimized neural network approach. Int J Eng Trans B Appl. 2025;38:1190–212.10.5829/ije.2025.38.05b.19Search in Google Scholar

34. Tariq, A, Deliktaş, B. An inverse parameter identification in finite element problems using machine learning-aided optimization framework. Exp Mech 2025;65:325–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11340-024-01136-z.Search in Google Scholar

35. Barkhordari, MS, Zhou, N, Li, K, Qi, C. Interpretable machine learning for predicting heavy metal removal efficiency in electrokinetic soil remediation. J Environ Chem Eng 2024;12:114330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2024.114330.Search in Google Scholar

36. Kuosa, H. Concrete durability field testing –– Field and laboratory results 2007–2010 in DuraInt-project. VTT Research Report VTT-R-00482-11; 2011:96 p.Search in Google Scholar

37. Choi, YC, Park, B, Pang, GS, Lee, KM, Choi, S. Modelling of chloride diffusivity in concrete considering effect of aggregates. Constr Build Mater 2017;136:81–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.01.041.Search in Google Scholar

38. Sell Junior, FK, Wally, GB, Teixeira, FR, Magalhães, FC. Experimental assessment of accelerated test methods for determining chloride diffusion coefficient in concrete. Rev IBRACON Estruturas e Mater 2021;14:e14407. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1983-41952021000400007.Search in Google Scholar

39. Elfmarkova, V, Spiesz, P, Brouwers, HJH. Determination of the chloride diffusion coefficient in blended cement mortars. Cem Concr Res 2015;78:190–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2015.06.014.Search in Google Scholar

40. Audenaert, K, Yuan, Q, De Schutter, G. On the time dependency of the chloride migration coefficient in concrete. Constr Build Mater 2010;24:396–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.07.003.Search in Google Scholar

41. Park, JI, Lee, KM, Kwon, SO, Bae, SH, Jung, SH, Yoo, SW. Diffusion decay coefficient for chloride ions of concrete containing mineral admixtures. Adv Mater Sci Eng 2016;2016:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2042918.Search in Google Scholar

42. Marks, M, Glinicki, MA, Gibas, K. Prediction of the chloride resistance of concrete modified with high calcium fly ash using machine learning. Materials (Basel) 2015;8:8714–27. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8125483.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

43. Anas, M, Khan, M, Bilal, H, Jadoon, S, Khan, MN. Fiber reinforced concrete: a review †. Eng Proc 2022;22:3. https://doi.org/10.3390/engproc2022022003.Search in Google Scholar

44. Alyami, M, Nassar, RUD, Khan, M, Hammad, AW, Alabduljabbar, H, Nawaz, R, et al.. Estimating compressive strength of concrete containing rice husk ash using interpretable machine learning-based models. Case Stud Constr Mater 2024;20:e02901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e02901.Search in Google Scholar

45. Alyami, M, Khan, M, Fawad, M, Nawaz, R, Hammad, AWA, Najeh, T, et al.. Predictive modeling for compressive strength of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using machine learning algorithms. Case Stud Constr Mater 2024;20:e02728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02728.Search in Google Scholar

46. Alyousef, R, Rehman, MF, Khan, M, Fawad, M, Khan, AU, Hassan, AM, et al.. Machine learning-driven predictive models for compressive strength of steel fiber reinforced concrete subjected to high temperatures. Case Stud Constr Mater 2023;19:e02418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02418.Search in Google Scholar

47. Khan, M, Khan, A, Khan, AU, Shakeel, M, Khan, K, Alabduljabbar, H, et al.. Intelligent prediction modeling for flexural capacity of FRP-strengthened reinforced concrete beams using machine learning algorithms. Heliyon 2024;10:e23375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e23375.Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

48. Alabduljabbar, H, Khan, M, Awan, HH, Eldin, SM, Alyousef, R, Mohamed, AM. Predicting ultra-high-performance concrete compressive strength using gene expression programming method. Case Stud Constr Mater 2023;18:e02074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02074.Search in Google Scholar

49. Yang, Q, Wu, Y, Zhi, P, Zhu, P. Effect of micro-cracks on chloride ion diffusion in concrete based on stochastic aggregate approach. Buildings 2024;14:1353. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14051353.Search in Google Scholar

50. Tariq, A, Polat, A, Deliktaş, B. Boosting machine learning algorithms for predicting the macroscopic material behavior of continuous fiber reinforced composite. J Reinf Plast Compos. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1177/07316844241292694.Search in Google Scholar

51. Polat, A, Tariq, A, Okay, F, Deliktaş, B. Investigation of the critical buckling load of a column with linearly varying moment of inertia using analytical, numerical, and hybrid machine learning approaches. J Strain Anal Eng Des 2025;60:612–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/03093247251337987.Search in Google Scholar

52. Tariq, A, Uzun, B, Deliktaş, B, Yaylı, MÖ. An investigation on ensemble machine learning algorithms for nonlinear stability response of a two-dimensional FG nanobeam. J Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng 2024;46:556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40430-024-05093-5.Search in Google Scholar

53. Mohammed, A, Burhan, L, Ghafor, K, Sarwar, W, Mahmood, W. Artificial neural network (ANN), M5P-tree, and regression analyses to predict the early age compression strength of concrete modified with DBC-21 and VK-98 polymers. Neural Comput Appl 2021;33:7851–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-05525-y.Search in Google Scholar

54. Khan, M, Nassar, RUD, Khan, AU, Houda, M, El Hachem, C, Rasheed, M, et al.. Optimizing durability assessment: machine learning models for depth of wear of environmentally-friendly concrete. Results Eng 2023;20:101625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101625.Search in Google Scholar

55. Shakr, PN, Mohammed, A, Hamad, SM, Kurda, R. Electrical resistivity-compressive strength predictions for normal strength concrete with waste steel slag as a coarse aggregate replacement using various analytical models. Constr Build Mater 2022;327:127008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127008.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Towards sustainable concrete pavements: a critical review on fly ash as a supplementary cementitious material

- Optimizing rice husk ash for ultra-high-performance concrete: a comprehensive review of mechanical properties, durability, and environmental benefits

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Experimental and RSM-based optimization of sustainable concrete properties using glass powder and rubber fine aggregates as partial replacements

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Towards sustainable concrete pavements: a critical review on fly ash as a supplementary cementitious material

- Optimizing rice husk ash for ultra-high-performance concrete: a comprehensive review of mechanical properties, durability, and environmental benefits

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Experimental and RSM-based optimization of sustainable concrete properties using glass powder and rubber fine aggregates as partial replacements

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods