Abstract

This study assesses the technical feasibility of replacing portions of the cement in mortar mixes with copper mine tailings, with a particular focus on mechanical strength. Compression, flexural, workability (flow test), and splitting tensile strength tests were conducted with different replacement percentages of cement by copper tailings (10, 20, and 30%). The experimental setup included three study cases: (i) fine aggregates, (ii) coarse aggregates, and (iii) fine aggregates with double the cement/tailings dosage ratio. The results revealed a decrease in mechanical strength as the percentage of mining tailings increased for compressive and tensile strength. However, the compressive and flexural strength increased when the cement-to-water ratio was increased in which case good mechanical results were obtained. In particular, in case (iii), the flexural strength increased by almost 40% when a mixture with 30% of copper tailings was used. Thus, the results obtained here suggest that it is feasible to use copper tailings in the manufacture of mortars, achieving acceptable mechanical strength and promoting a circular economy in copper extraction.

1 Introduction

The mining industry is growing worldwide due to the increasing demand for raw materials, making it globally the largest waste-generating industry. Approximately 65–80 billion tons of waste are generated annually after mining operations. Tailings represent about 10–15 billion tons of this total, with the rest being waste rock [1]. In Chile, 764 mine-tailing deposits have been recorded [2]. Of these, 110 deposits are currently in operation (14%), 473 are inactive (62%), 173 are abandoned (23%), and 8 are under construction or under review (1%). Although the most widely used method for tailings disposal is tailings dams, this method has many disadvantages in terms of costs, the environment, and human health. There are approximately 3,500 active tailings dams worldwide, and hundreds of significant accidents related to these dams have been reported [3,4,5,6].

Currently, many environmental problems associated with tailings management in South America are related to potential soil, water (surface/groundwater), and air contamination. In recent years, there have been significant advances in tailings dewatering technologies [7,8], infiltration control from tailings storage facilities, and operational management of mining tailings. However, tailings spill accidents continue to occur, such as the Mount Polley case in Canada, the Fundao Samarco case in Brazil, the Corrego do Feijao Brumadinho case in Brazil, and the Jagersfontein case in South Africa [9,10].

Environmental damage occurring during tailings disposal through dams can be significantly reduced by using new technologies and methods such as paste technology [11,12], but these approaches are insufficient for sustainable mining. Due to the increase in tailings generation and the environmental and cost challenges associated with their disposal, finding an industrial use for tailings, such as in the concrete industry, would be beneficial to increase the sustainability of mining operations. Hence, this article investigates the impact of replacing a fraction of the cement in mortar production with copper tailings.

1.1 Theoretical background

Mine tailings have been used in mixed concrete but mostly as partial or complete substitutes for fine aggregate, given that tailing particles have diameters of less than 1 mm [13,14,15]. The physical characteristics of tailings notably influence their workability, density, and strength [16]. In general, tailings have a rough and irregular surface [17] due to the crushability of various mineral phases of which they are composed. Then, adding tailings to other materials increases the specific surface area of the new mixture and changes its rheological properties such as workability.

Workability, which is defined as the ease of transportation, placement, compaction, and finishing of the mixture, is an important property of fresh mortar or concrete mixtures [18]. The flow of mortar has been found to decrease with increasing tailing substitution levels because tailings have a finer particle-size distribution that raises the total surface area of fine aggregates [19,20,21]. Given the characteristics of tailings, steps before incorporating them into concrete as supplementary cementitious materials must be evaluated. These steps include drying, grinding, and/or calcining. Regrettably, only a limited number of research papers have delved into the drying process of tailings. Onuaguluchi et al. [22,23] tested tailing samples that underwent air drying and subsequent sieving under a 600 μm size sieve. Other researchers [24] have proposed that treating the tailings could involve passing them through a 45 μm size sieve before utilization in concrete. Additionally, few investigations [25,26] have employed grinding to treat tailings. Table 1 summarizes the chemical composition of tailings as reported in the literature used in mortar studies of tailings replacing cement.

Reported chemical composition (%) of different types of tailings

| References | Ore | Country | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | SO3 | K2O | Na2O | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nouairi et al. [27] | Zn·Pb tailings | Tunisia | 15.5 | 6.56 | 5.91 | 19.90 | 3.99 | 21.90 | 0.33 | 15.10 | |

| Zhang et al. [28] | Zn·Pb tailings | China | 69.92 | 10.41 | 1.89 | 2.19 | 1.39 | 0.55 | 2.17 | 0.51 | 3.68 |

| Argane et al. [29] | Zn·Pb tailings | Morocco | 68.44 | 9.38 | 2.20 | 1.99 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 5.46 | 0.70 | |

| Janković et al. [13] | Zn·Pb tailings | Serbia | 43.26 | 11.11 | 15.57 | 20.01 | 4.31 | 0.32 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 5.61 |

| Cheng et al. [30] | Iron tailings | China | 75.23 | 2.64 | 11.31 | 1.47 | 2.10 | 0.08 | 0.40 | 0.49 | |

| Fontes et al. [19] | Iron tailings | Brazil | 24.19 | 4.82 | 45.92 | 4.06 | |||||

| Shettima et al. [31] | Iron tailings | Malaysia | 56.00 | 10.00 | 8.30 | 4.30 | 1.50 | 3.30 | |||

| Zhao et al. [17] | Iron tailings | China | 52.06 | 17.14 | 9.13 | 12.74 | 3.68 | 0.30 | 0.97 | 3.23 | |

| Gupta et al. [32] | Copper tailings | India | 75.00 | 12.16 | 3.60 | 0.16 | 0.49 | 1.85 | 4.297 | 2.10 | |

| Kiventerä et al. [33] | Gold tailings | Finland | 49.90 | 10.40 | 9.70 | 11.10 | 5.90 | 1.30 | 3.00 | 12.90 | |

| Ye et al. [34] | Bauxite tailings | China | 32.24 | 37.39 | 8.67 | 3.15 | 0.85 | 13.74 | |||

| Zheng et al. [35] | Phosphate tailings | China | 2.10 | 0.10 | 0.80 | 36.80 | 18.90 | 1.00 | 0.10 | 35.80 | |

| Pyo et al. [36] | Quartz-based tailings | Korea | 79.53 | 9.52 | 3.22 | 0.51 | 0.64 | 3.24 | 0.72 | 2.46 |

In general, mine tailings exhibit a high silica content, as detailed in Table 1, which increases the molar ratio of SiO2/Al2O3 in geopolymer composites derived from mine tailings, negatively affecting the geopolymerization process. For this reason, metakaolin is more frequently used in the chemical industry as an additional source of aluminum [37,38,39] due to the purity and uniformity of its composition, as well as its high interaction capacity [40]. Furthermore, the addition of supplementary alumina-silicate source materials enhances the compressive strength of copper mine tailings-based geopolymer composites [41,42]. Similarly, increasing the concentrations of copper slag, raising the sodium silicate-to-sodium hydroxide ratio up to 1.0, and increasing the molarity of sodium hydroxide solutions to 10 molars all contribute to an improvement in the compressive strength of copper mine tailings and copper slag blended geopolymers [43,44].

Some studies have observed that the use of tailings as a cement substitute has resulted in a decrease in compressive strength with an increase in the proportion of tailings, regardless of the age of the concrete or mortar [25,26,30,35,45,46]. In these studies, the decline was attributed to the low pozzolanic activity of tailings as supplementary cementitious materials, even when treated as ground powder. However, in a few cases, a specific concentration of fine tailings could enhance the compressive strength of concrete with tailings as supplementary cementitious materials because the fine tailings powder could fill minuscule pores, accelerating cement hydration [26,30,35,45]. Indeed, Franco de Carvalho et al. [47] demonstrated that if fine basic oxygen furnace slag tailings were used as supplementary cementitious material, the compressive strength was highest with a 20% fine tailings replacement. If 40% coarse tailings and 20% fine tailings were added, the strength was lower than that of the control concrete but still close to it. By using calcined tailings, in which metakaolin was created from the kaolinite, the compressive strength of concrete improved [48,49]. Also, in tailings used as an additive to concrete, without replacing cement, it was found that the compressive strength was higher than the control concrete due to the filler effect [23,50,51].

Compressive strength and flexural strength tests with copper tailings as replacements for sand were evaluated in previous studies [32,50]; these studies suggested that the higher strengths of the samples mixed with copper tailings are due to the filling effect and the moderate reactivity of the fine particles of the tailings along with the cement particles. Furthermore, the setting time of cement replacement with tailings has been analyzed, in which a comparison case between tailings from the Nalunaq and Zinkgruvan mines [52] showed that the time from the initial setting to the final setting decreased for the tailings-cement mixture.

The promising results found when mixing tailings in concrete mixtures prompted to study the impact of mixing Chilean copper tailings on the mortar samples’ mechanical strength and workability. Different proportions – 10, 20, and 30% of cement replacement – were tested based on the above literature, which specified replacement percentages.

2 Materials and methods

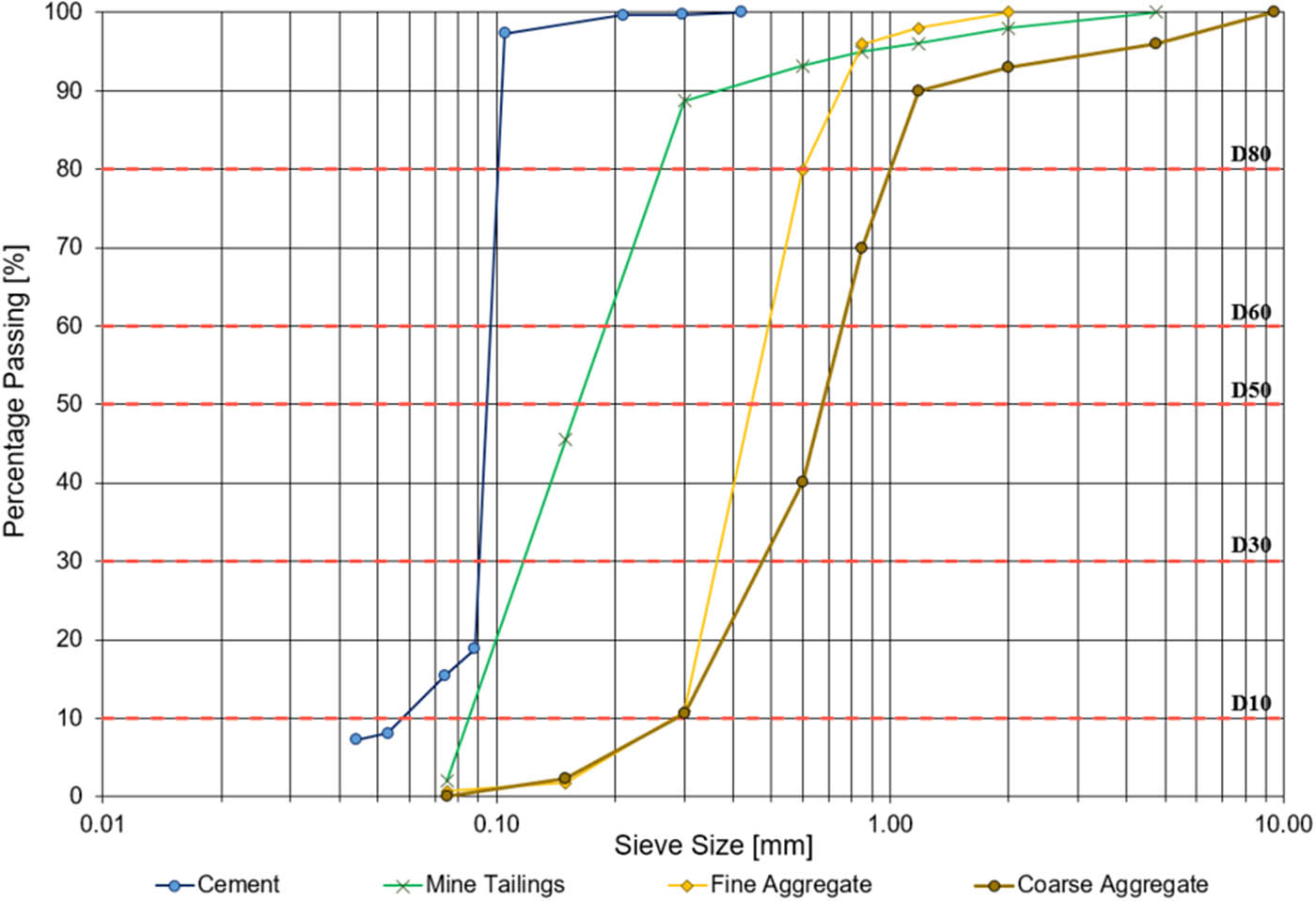

The materials used in this study are cement, fine and coarse aggregates, and copper mine tailings. Figure 1 shows the particle size distribution of these materials. As shown, the particle size distribution of mine tailings used in this study is finer than that of the aggregates and coarser than cement particles. A detailed characterization of these materials is described further in this study.

Particle size distribution of copper tailings and cement.

2.1 Cement

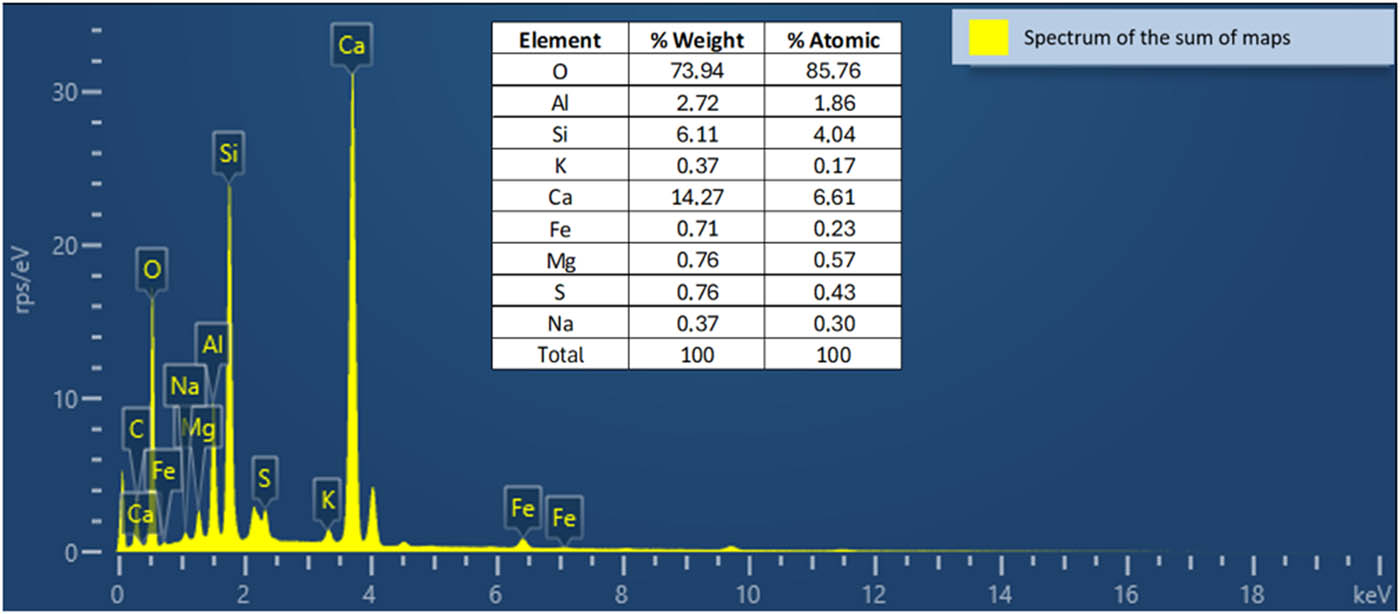

A pozzolanic-class cement was used based on its composition and strength [53]. The results of an Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis provided information about the elemental composition of the cement. Overall, EDS findings for the cement reveal the presence of abundant calcium, silicon, aluminum, and iron, which are responsible for providing strength and bonding characteristics to the cement from hydration reactions and processes during the setting.

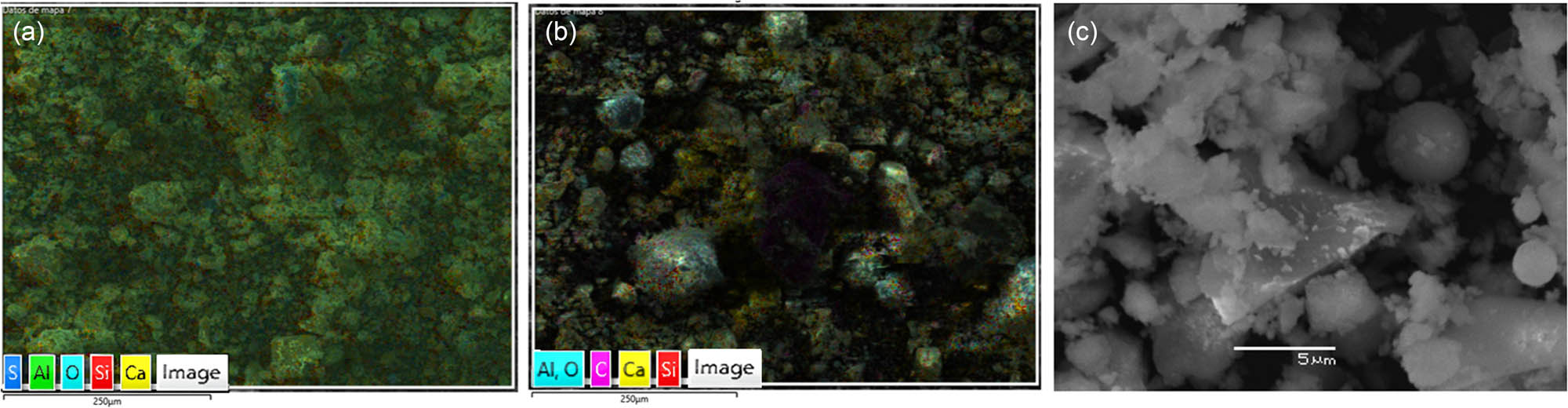

Figure 2 shows the weighted concentration of elements in the pozzolanic cement. EDS results primarily specify the chemical composition of the materials present in the cement. Besides oxygen (O), calcium (Ca) was the most abundant element, representing 14.27% of the total weight. Silica and alumina, also abundant, had a positive impact on the cement due to their potential pozzolanic and semi-cementitious properties. The chemical and mechanical properties of the mortar will strengthen, depending on the dispersion of the elements. Here the dispersion clearly indicates good C–S–H formation in the mix. This directly influences increased pozzolanic activity during the hydration process. Figure 3 shows Scanning electron microscope (SEM) morphologies of the cement at scales of 250 and 5 µm, demonstrating a wide size-range of particles with irregular morphologies and small spherical pozzolana particles.

EDS of pozzolanic cement.

SEM of pozzolanic cement: (a and b) scale of 250 μm (mapping), and (c) scale of 5 μm.

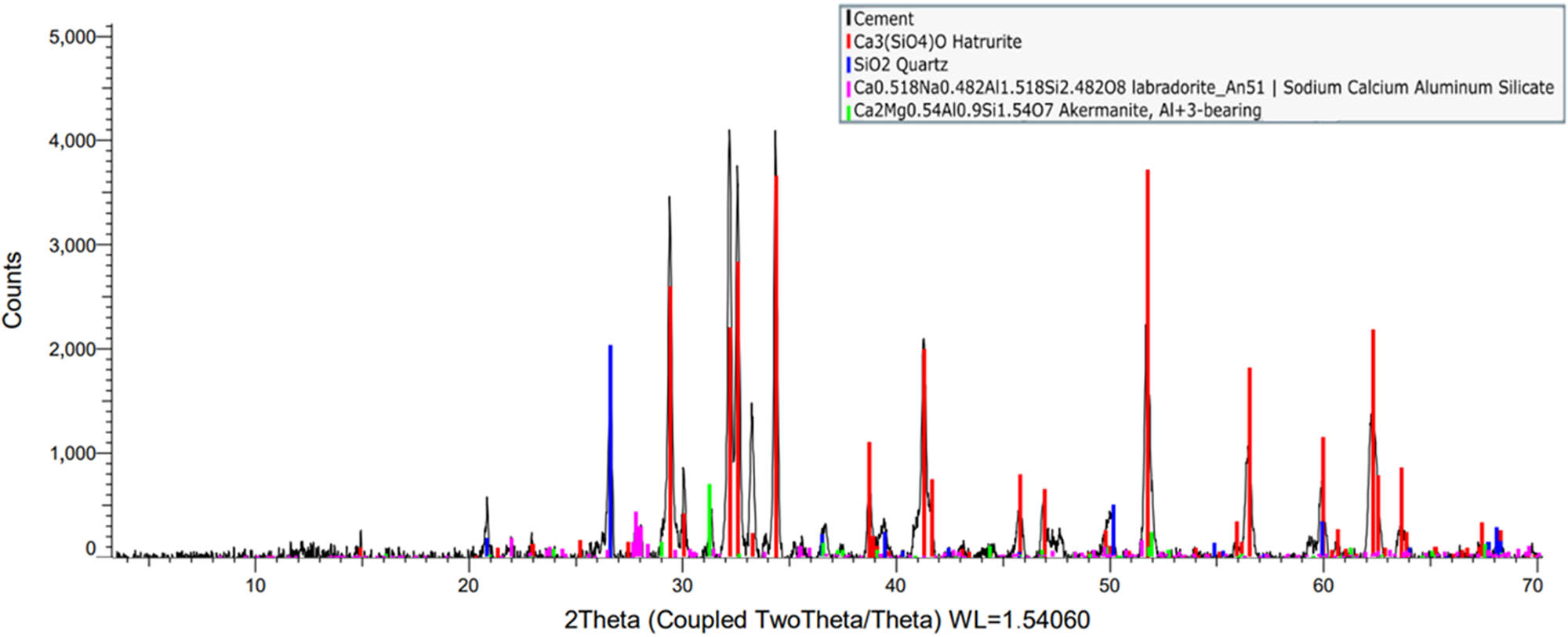

In addition, Table 2 shows the mineral phases present in the cement used, determined from X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. In order of abundance, Hatrurite, Quartz, Plagioclase, and Akermanite appear. Both Hatrurite (Ca3SiO5) and Akermanite (Ca2MgSi2O7) confer cementitious properties to the material. This mineralogy is consistent with the abundant calcium observed through the EDS analysis, as well as the rest of the determined elements. The overlap of diffraction peaks of the main components in the range of 2θ = 3°–70° can also be observed in Figure 4.

Mineralogy of the cement (XRD)

| Sample | Semi-quantitative mineralogy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plagioclase | Quartz | Hatrurite | Akermanite | |

| Cement (%) | 10.2 | 14.5 | 68.7 | 6.6 |

XRD of pozzolanic cement.

2.2 Fine and coarse aggregates

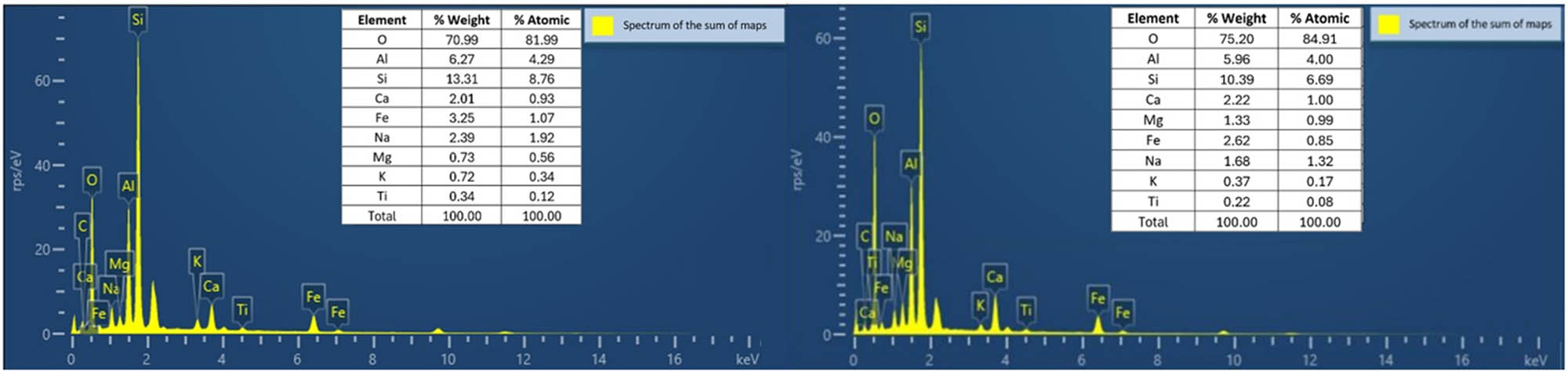

As shown in Figure 1, the maximum particle size used in this study was 2 mm for fine aggregate and under 4.5 mm for coarse aggregate. The fine and coarse aggregates have a density of 2.76 and 2.77 g·cm−3, respectively [54]. Figure 5 shows the weighted concentration of elements in the aggregates (through EDS). EDS results primarily specify the chemical composition of the materials. Besides oxygen, silicon (Si) is the most abundant with more than 10% and aluminum (Al) with about 6%. Also, there is a high presence of other elements such as Ca, Fe, Na, and Mg, in addition to the organic content of the sample.

EDS of fine aggregate (left) and coarse aggregate (right).

Additionally, Figure 6 shows SEM morphologies of the coarse and fine aggregate at scales between 500 and 5 µm. The irregular morphology of the surface of the grains and their angularity can be observed, as well as the gradation in their particle size. Fine aggregates (Figure 6a) have a higher uniformity coefficient than coarse aggregates (Figure 6d). Based on the roundness scale of Powers [55], the particles are subrounded and with low sphericity. These characteristics, together with the aforementioned mineralogical composition, point to a mafic volcanic origin of the source rock of both types of aggregates, which have been fragmented, transported, and accumulated naturally by streams of water.

SEM of fine and coarse aggregate. Fine – (a)–(c): scale of 500, 10, and 5 μm, respectively. Coarse – (d)–(f): scale of 500, 200, and 10 μm, respectively.

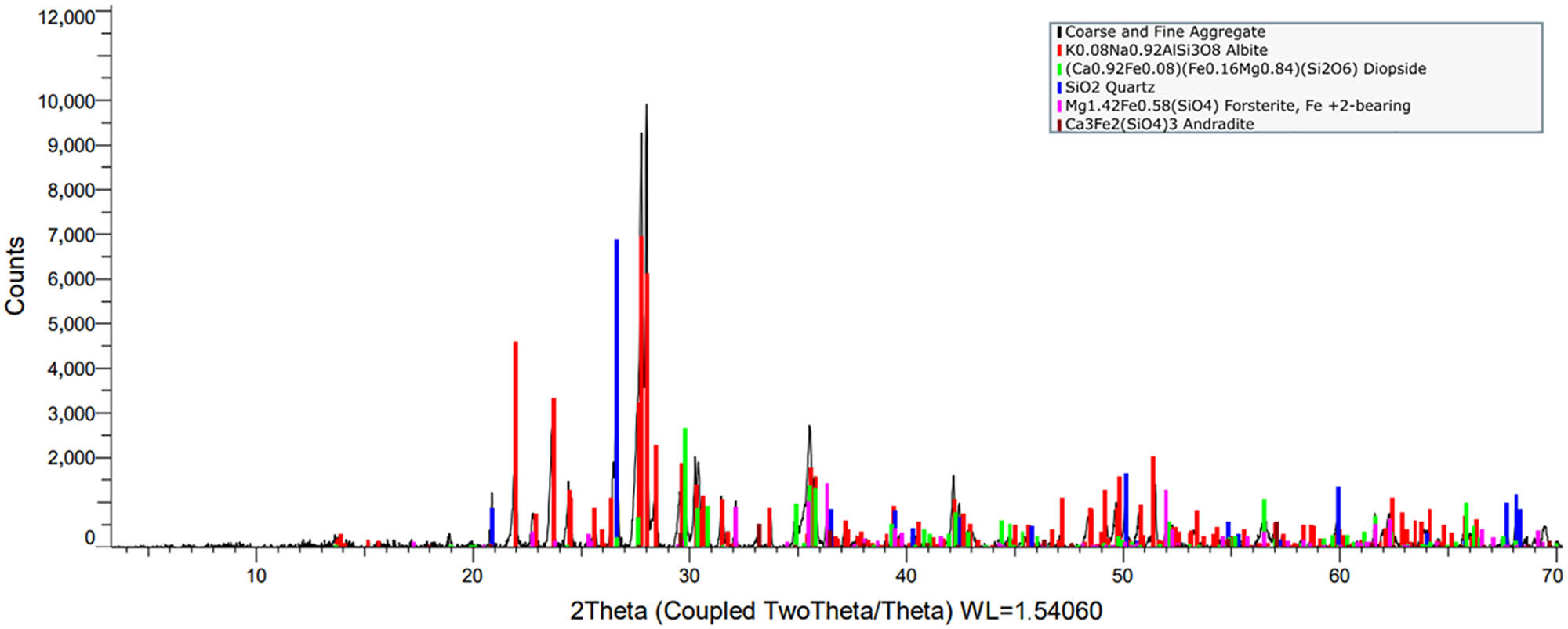

Table 3 shows five types of mineral components obtained by XRD: Pyroxene, Quartz, Plagioclase, Olivine, and Garnet. The overlap of diffraction peaks of the main components in the range of 2θ = 3° to 70° can also be observed in Figure 7.

Mineralogy of fine and coarse aggregate X-ray diffraction (XRD)

| Sample | Semi-quantitative mineralogy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plagioclase | Quartz | Pyroxene | Olivine | Garnet | Hematite | |

| Fine aggregate (%) | 64.9 | 11.8 | 13.0 | 8.5 | 1.7 | 0.1 |

| Coarse aggregate (%) | 64.9 | 11.8 | 13.1 | 8.5 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

XRD pattern of coarse and fine aggregate (red – plagioclase, blue – quartz, green – pyroxene, pink – olivine, and maroon – garnet).

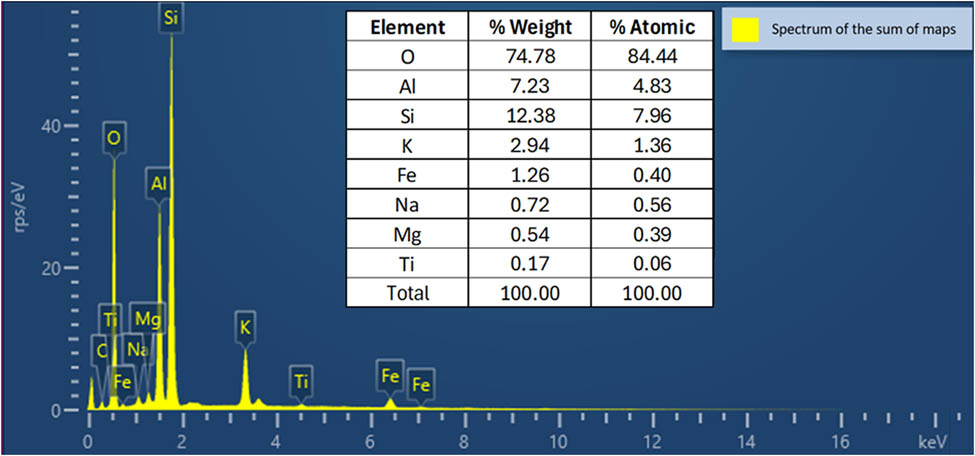

2.3 Copper mine tailings

The EDS results primarily specify the chemical composition of the materials present in the copper mine tailings. After oxygen (O), silicon (Si) is the most abundant cation, representing 12.38% of the total weight, followed by silicon aluminum (Al) with 7.23% (Figure 8).

EDS of copper tailings.

Atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) is commonly employed to identify the concentration of metals/metalloids in environmental studies. To evaluate whether the use of these copper tailings could pose a potential environmental hazard, analyses of heavy metals present in the material were carried out, using a total sample digestion process and then AAS. The AAS results are shown in Table 4.

Amount of each element in copper tailing used in this study

| Sample | Cu | Co | Ni | Mn | Cr | Pb | As | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tailing (mg·kg−1) | 732.8 | — | 70.3 | 94.7 | 113.8 | 17.7 | 151.0 | 108.7 |

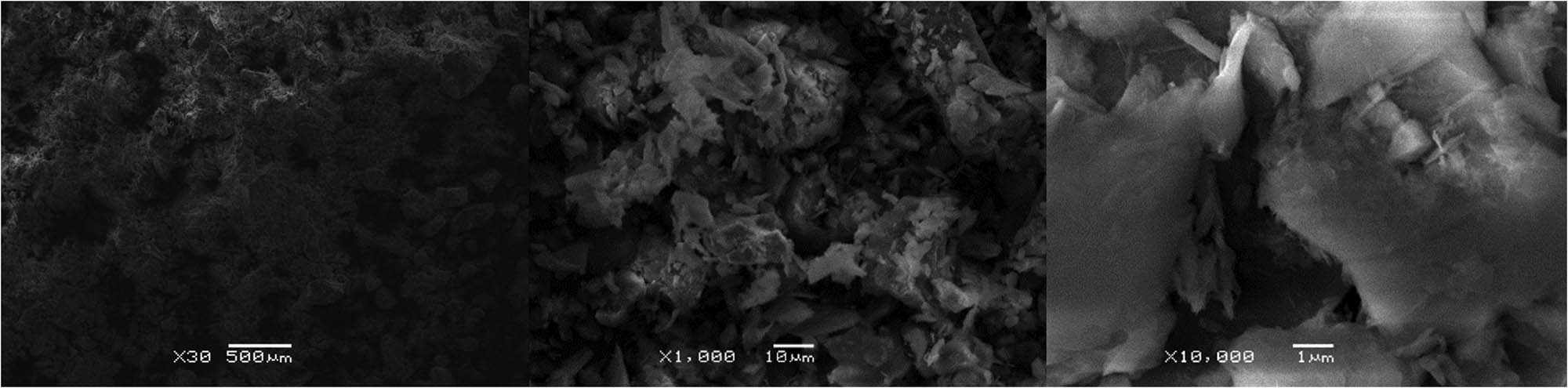

Figure 9 presents SEM images, showing morphologies and sizes of the copper mine tailings. The morphology of the particles is irregular due to the comminution processes, and their size is mostly less than 500 µm, with finer sizes predominating, data that agree with the particle-size-distribution are presented in Figure 1. Additionally, tailings exhibited a range of densities because of the various mineral phases present. Tailings used in this study had a bulk density of 2.67 g·cm−3 [54].

SEM with EDS of copper tailings. (a)–(c): Scale of 500, 10, and 1 μm, respectively.

The chemical composition of the mine tailings used in this study is shown in Table 5. Silica and alumina are the main components of these tailings. In lower concentrations, alkalis (K and Na) also stand out. The measurement of Total Organic Carbon (TOC) is also presented in Table 5, where a value above 4 is shown for the copper mineral tailings used in this study.

Reported chemical composition of copper tailing (%)

| Types of tailings | Sources | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | SO3 | K2O | Na2O | TOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper tailings | Chile | 66.71 | 20.47 | 1.84 | 0.36 | 1.39 | 0.52 | 6.15 | 1.54 | 4.04 |

| P2O5 | TiO2 | Cr2O3 | MnO | CuO | Rb2O | ZrO2 | BaO | |||

| 0.16 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

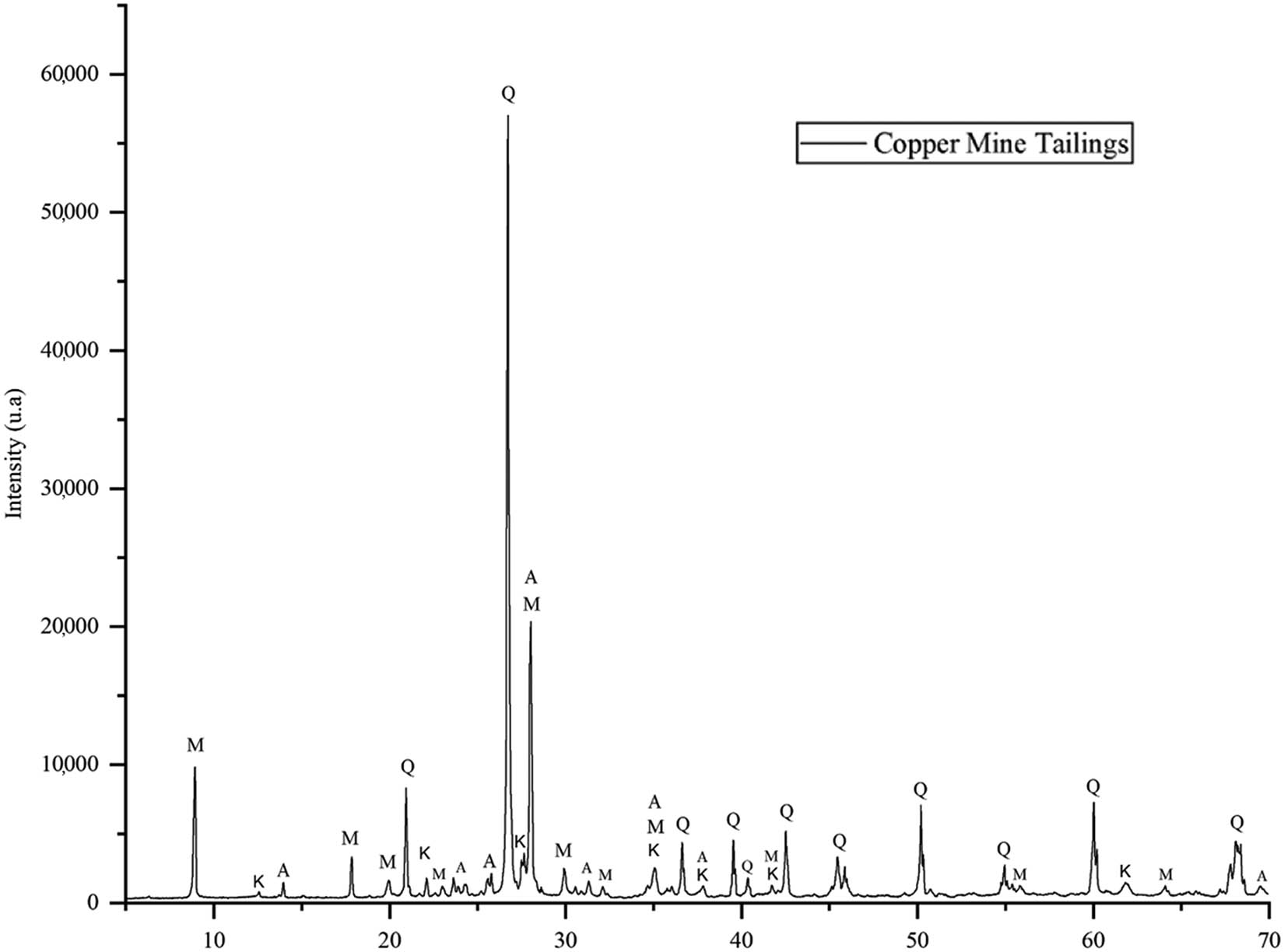

Table 6 displays the semi-quantitative mineralogical composition obtained for the copper tailings, along with the corresponding diffractogram of the copper tailings depicting their respective phases as shown in Figure 10. It is noteworthy that the mineral phases present are quartz (SiO2), muscovite (KAl2(AlSi3O10)(OH)2), albite (NaAlSi3O8), and kaolinite (Al2 Si2O5(OH)4). This composition indicates a felsic-type parent rock, with a certain degree of alteration that gives rise to the appearance of kaolinite, unlike the aggregates used, which originate from mafic rocks. The percentage of muscovite explains the high concentration of potassium observed. On the other hand, the presence of kaolinite and muscovite is important for this work, due to their potential pozzolanic behavior. However, quartz, the main component of the tailings, is a resistant mineral even in the alkaline conditions of the medium presented by the mortars [56]. Nevertheless, quartz will not have an important contribution to the cementing properties.

Mineralogy of copper mine tailings (XRD)

| Semi-quantitative mineralogy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Quartz | Muscovite | Albite | Kaolinite |

| Copper mine tailings (%) | 43.9 | 21.1 | 23.5 | 11.5 |

XRD pattern of copper mine tailings (Q – quartz, M – muscovite, A – albite, and K – kaolinite).

2.4 Samples

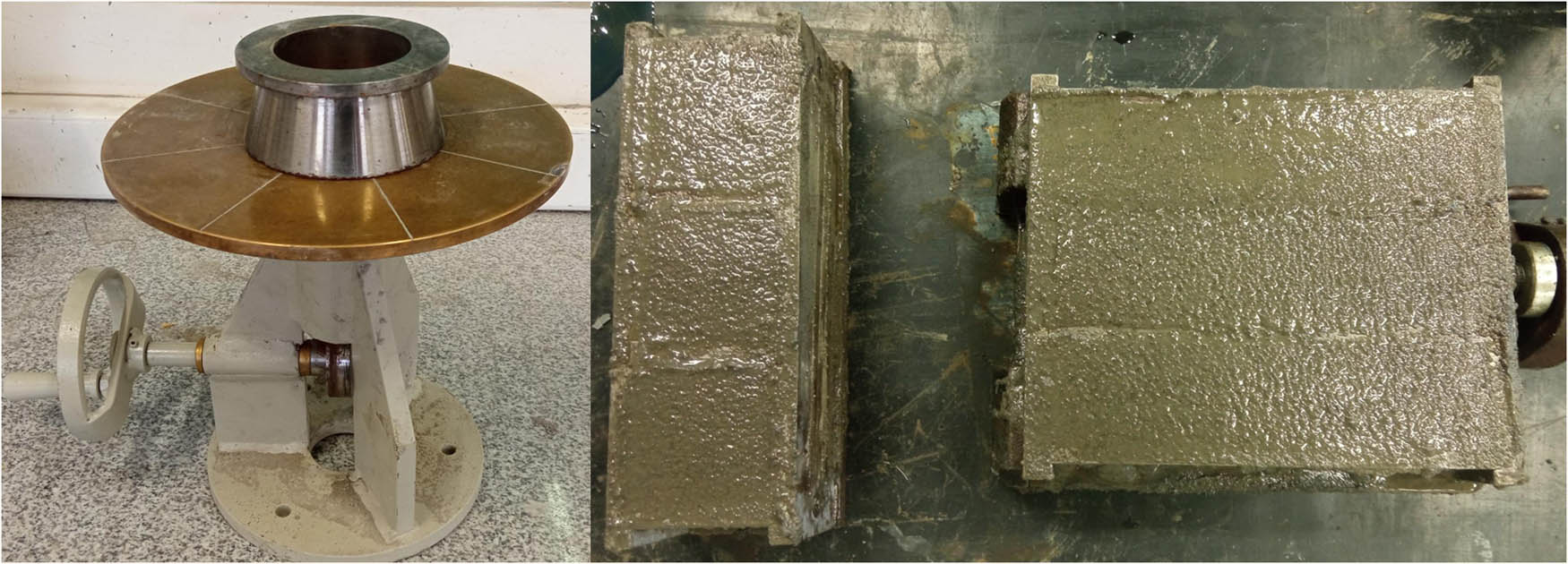

The mortar samples were fabricated in steel molds. The steel molds used have dimensions of 50 mm × 50 mm × 50 mm for cube samples, 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm for prism samples, and 70 mm diameter × 150 mm length for cylinder samples. Figure 11 shows mortar samples before mechanical tests. Initially, a total of 60 mortar samples were prepared (including the control samples without tailings) with different dosages corresponding to a 10% (RC10C), 20% (RC20C), and 30% (RC30C) replacement of cement with copper mine tailings with fine aggregate, and 12 mortar samples (only cubes) with coarse aggregate.

RC30C samples.

Then, 24 samples were prepared by adjusting the initial dosages to increase the use of cement and copper tailings and decrease the water/cement (w/c) and water/(cement + tailing) ratios by almost half, exclusively using fine aggregate.

Each initial mortar components is summarized in Table 7. Samples containing coarse aggregate are indicated by the term “AG” (e.g., Control_AG); in the other samples, only fine aggregate was used. The samples with an asterisk correspond to the adjusted dosage.

Dosages used in mortar samples

| Sample | Dosages with fine aggregate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement (kg·m−3) | Water (kg·m−3) | Fine aggregate (kg·m−3) | Coarse aggregate (kg·m−3) | Copper tailing (kg·m−3) | % Replacement of cement by copper tailings | w/c ratio | w/(c+tailing) ratio | |

| Control | 420 | 335 | 1,657 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.80 | 0.8 |

| RC10C | 378 | 42 | 10 | 0.89 | ||||

| RC20C | 336 | 84 | 20 | 0.99 | ||||

| RC30C | 294 | 126 | 30 | 1.14 | ||||

| Dosages with coarse aggregate | ||||||||

| Control_AG | 420 | 335 | 0 | 1,657 | 0 | 0 | 0.80 | 0.8 |

| RC10C_AG | 378 | 42 | 10 | 0.89 | ||||

| RC20C_AG | 336 | 84 | 20 | 0.99 | ||||

| RC30C_AG | 294 | 126 | 30 | 1.14 | ||||

| *Adjusted dosage used | ||||||||

| *Control | 853 | 342 | 1,137 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 |

| *RC10C | 768 | 85 | 10 | 0.45 | ||||

| *RC20C | 682 | 171 | 20 | 0.50 | ||||

| *RC30C | 597 | 256 | 30 | 0.57 | ||||

The variation in adjusted dosage involves the quantity of cement and tailings and consequently fine material amounts. Additionally, different water-to-cement ratios were considered to achieve a suitable workability mixture (evaluated through flow test). The adjusted dosage for the mortar was developed to investigate the effect of cement replacement while simultaneously increasing the overall cement content and reducing the water–cement ratio. This approach was specifically designed to evaluate how an optimized mixture could compensate for potential reductions in mechanical performance or durability often associated with partial cement replacement in an effort to obtain favorable results in mechanical resistance using mining tailings.

In the experimental plan, not all dosages underwent the same number of tests because of a shortage of tailings material. Table 8 presents the test matrix for each sample, indicating which tests were conducted. Three samples were prepared for each dosage. This triplicate testing approach helps mitigate any potential variability and provides a more robust dataset for analysis to ensure the reliability and accuracy of the results.

Test matrix

| Test type | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compression | Flexural | Splitting tensile | Flow | ||||

| Sample | 7 days | 28 days | |||||

| Fine aggregate/X% water in mortar | Control (0% replacement) | 1 | X | X | X | X | X |

| 2 | |||||||

| 3 | |||||||

| RC10C (10% replacement) | 4 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 5 | |||||||

| 6 | |||||||

| RC20C (20% replacement) | 7 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 8 | |||||||

| 9 | |||||||

| RC30C (30% replacement) | 10 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| 11 | |||||||

| 12 | |||||||

| Coarse aggregate/X% water in mortar | Control (0% replacement) | 1 | X | X | X | ||

| 2 | |||||||

| 3 | |||||||

| RC10C (10% replacement) | 4 | X | X | X | |||

| 5 | |||||||

| 6 | |||||||

| RC20C (20% replacement) | 7 | X | X | X | |||

| 8 | |||||||

| 9 | |||||||

| RC30C (30% replacement) | 10 | X | X | X | |||

| 11 | |||||||

| 12 | |||||||

| Fine aggregate/Y% water | Control (0% replacement) | 1 | X | X | X | ||

| 2 | |||||||

| 3 | |||||||

| RC10C (10% replacement) | 4 | X | X | X | |||

| 5 | |||||||

| 6 | |||||||

| RC20C (20% replacement) | 7 | X | X | X | |||

| 8 | |||||||

| 9 | |||||||

| RC30C (30% replacement) | 10 | X | X | X | |||

| 11 | |||||||

| 12 | |||||||

2.5 Flow tests

The mixing process begins with a mixer in the starting position, water poured into a container, and the continuous addition of cement. Once the mixture is prepared, the flow test is conducted following ASTM C1437 [57]. The test begins by introducing the mixture into the cone, giving it a height of approximately 25 mm, compacting it with 20 strokes made by rotating the handlebar of the testing device to finally determine the height difference. The results obtained are shown in Table 9.

Mortar workability ranges [58]

| Average diameter (mm) | <130 | 131–180 | 181–220 | 221–250 | >250 |

| Workability | Dry | Plastic | Soft | Fluid | Liquid |

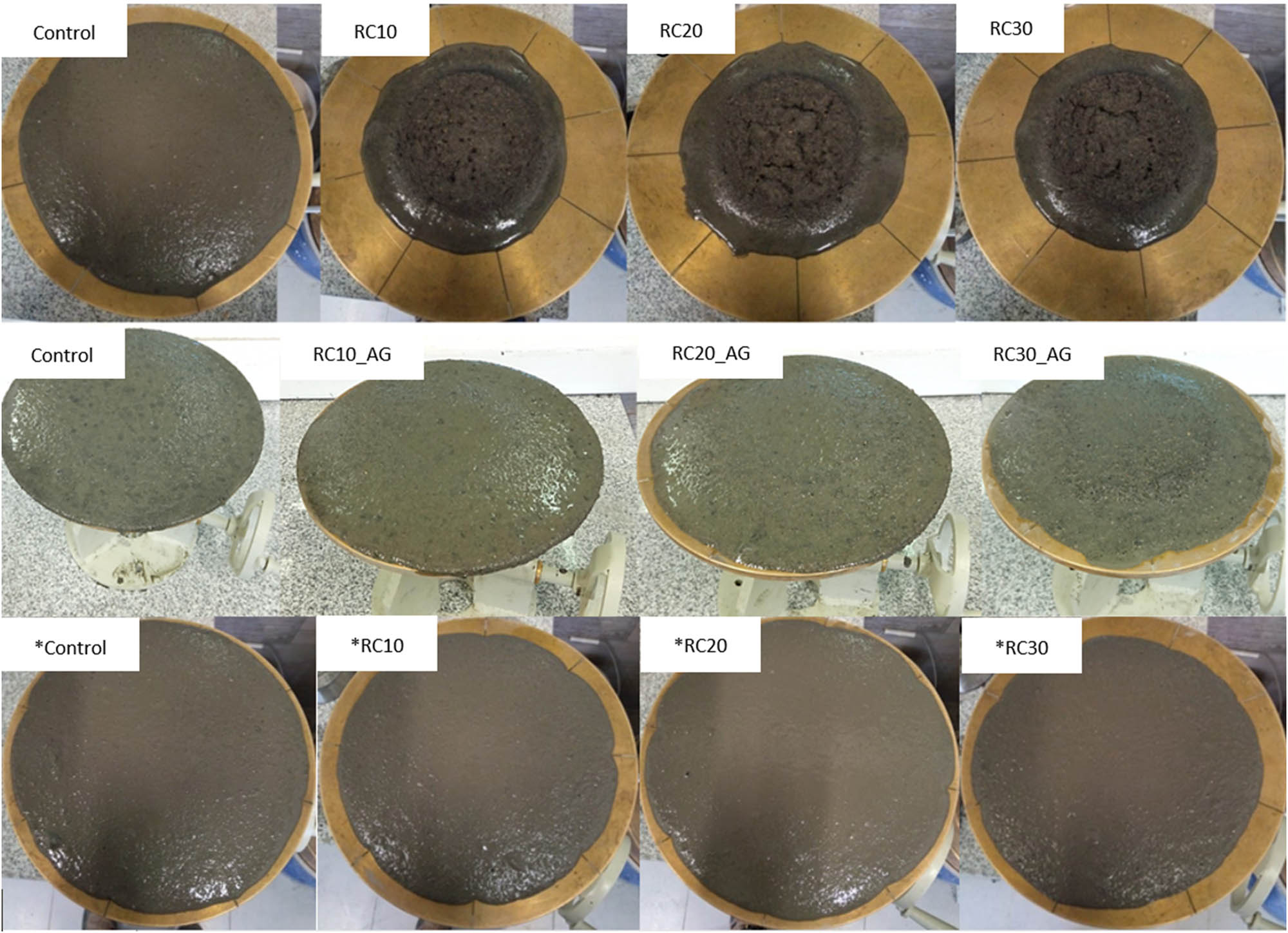

To complete the flow test, the mixture was put in steel molds as shown in Figure 12. After setting for 24 h, the samples are demolded and then cured for 7 and 28 days for cubes and prisms, and 28 days for cylinders. After the curing period, samples were dried at a temperature of 110°C for 24 h. Once the drying was complete, samples were cooled to room temperature to conduct the mechanical tests. The samples were dried because some studies [59,60] indicate that the presence of moisture in the samples can reduce their mechanical strength in both compression and flexure.

Equipment used for the flow test (left) and cubic-prismatic samples (right).

2.6 Mechanical test: Compression, flexural, and tensile tests

Compressive strength is a key parameter in concrete and related materials. This parameter indicates the mix's compressive strength after hardening and is indirectly related to other properties such as compactness, toughness, and durability [61]. In this study, the Chilean Standard #1037 is used, which has an adaptation in the Chilean Manual [62].

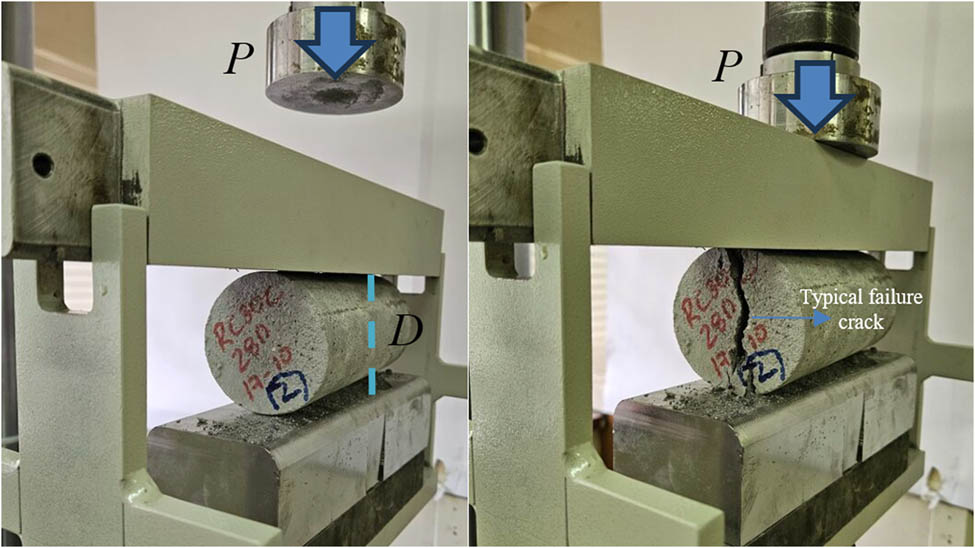

Figure 13 shows an example of the compression test carried out. To validate the test, after the sample fails, a load equivalent to 60% of the maximum load is applied to determine the type of failure. Sixty compression tests were conducted: 24 cubic samples with fine aggregate (7 and 28 curing days), 24 cubic samples with coarse aggregate (7 and 28 curing days), 12 cubic samples with fine aggregate and adjusted dosage (28 curing days).

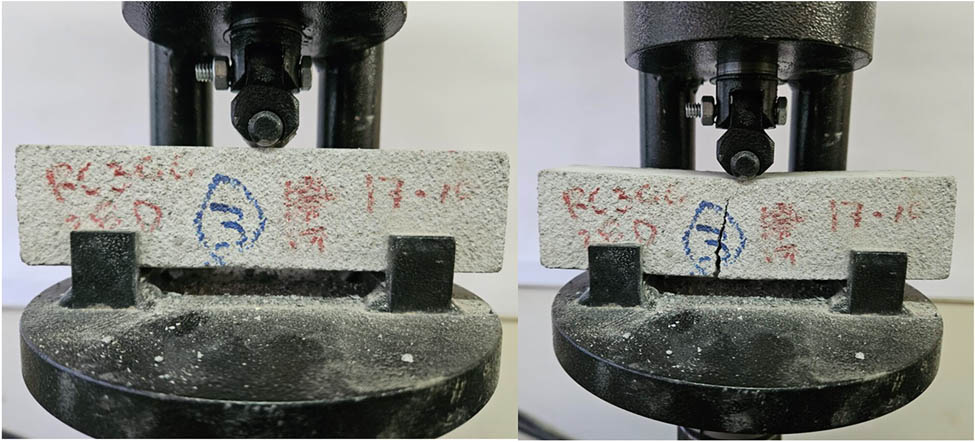

Example of compression test.

Flexural strength corresponds to the theoretical maximum tensile stress reached at the extreme tensioned part of a test beam under a three-point bending test (Figure 14). The Chilean standard NCh 1038 has an adaptation corresponding to section 8.402.12 in the Highway Manual [62], and this adapted standard was used in this study. At 28 days of curing, 36 flexural tests were conducted, including 12 with fine aggregate, 12 with coarse aggregate, and 12 with adjusted fine aggregate.

Example of flexural test.

Tensile cracking is a common failure mode in mortars. To test for this failure, split tensile testing were done following the 1170 standard, as adapted in the Highway Manual, corresponding to section 8.402.13 [62]. This standard establishes the procedure for conducting the splitting tensile strength test on cylindrical specimens until failure. This method employs various loading patterns classified into four typical modes: flat plates, loading jaws, modified wooden pads and loading plates. Among these loading patterns, the flat loading was selected (Figure 15). Twelve splitting tests were conducted at 28 days of curing.

Example of splitting tensile strength test.

3 Experimental results

3.1 Flow test results

Figure 16 shows the flow test of different samples, and Table 10 shows their workability ranges. Of all the samples, just the first two mixtures (RC10C and RC20C) entered the plastic workability range, defined in Table 9, which is useful for considering shotcrete, helping to prevent possible segregation in the case of being too dry or too wet. The RC30C replacement had a flow percentage of 59.24%, indicating a rigid workability, which could complicate possible shotcreting. All the samples of coarse aggregate remained in a moist workability condition (Table 9). A greater segregation of material was observed in the mixture made with coarse particles and 30% replacement of tailings (Figure 16h). In this case, the coarse material was found to concentrate in the central part with migration of cement toward the external parts. Otherwise, the mixtures with adjusted dosages of cement, tailings, and water improved the workability of the prepared mortars compared to the control sample, as evidenced by the samples with 10, 20, and 30% replacement.

Consistencies of mortar from left to right: Top row – fine aggregate. Second row – coarse aggregate. Last row – adjusted doses of mortar.

Samples workability (range mm)

| Workability of dosages with fine aggregate | ||

| Control | 205 | Soft (181–220) |

| RC10C | 179 | Plastic (131–180) |

| RC20C | 177 | Plastic (131–180) |

| RC30C | 159 | Plastic (131–180) |

| Workability of dosages with coarse aggregate | ||

| Control_AG | 250 | Fluid (221–250) |

| RC10C_AG | 247 | Fluid (221–250) |

| RC20C_AG | 225 | Fluid (221–250) |

| RC30C_AG | 223 | Fluid (221–250) |

| *Workability of adjusted mortar dosages | ||

| *Control | 231 | Fluid (221–250) |

| *RC10C | 209 | Soft (181–220) |

| *RC20C | 223 | Fluid (221–250) |

| *RC30C | 216 | Soft (181–220) |

3.2 Compression test

Figure 17 shows the compression test results for 7 and 28 days of curing for the Control, RC10C, RC20C, and RC30C samples and x_AG samples. Here samples of 28 days of curing with adjusted dosages are also included (*). The highest values for the three dosages (fine aggregate, coarse sand, and fine aggregate adjusted) are in the control samples. The compressive strength in all samples decreased as more tailings were added to replace cement.

![Figure 17

Compression test results in all samples. Red dashed line represents the minimum suggested for shotcrete applications [61].](/document/doi/10.1515/rams-2025-0137/asset/graphic/j_rams-2025-0137_fig_017.jpg)

Compression test results in all samples. Red dashed line represents the minimum suggested for shotcrete applications [61].

When comparing the results obtained from the initial dosage and the adjusted dosage, an increase in the compressive strength value was observed, maintaining the trend of decreasing compressive strength value as the dosage of cement replacement by tailings increased. Additionally, it was noted that the control sample continued to maintain the highest compressive strength value. The compressive strength values increased on average by 199% when adjusting the dosages as described in Table 7, and the difference between the initial and final values obtained for compressive strength averaged 31 MPa.

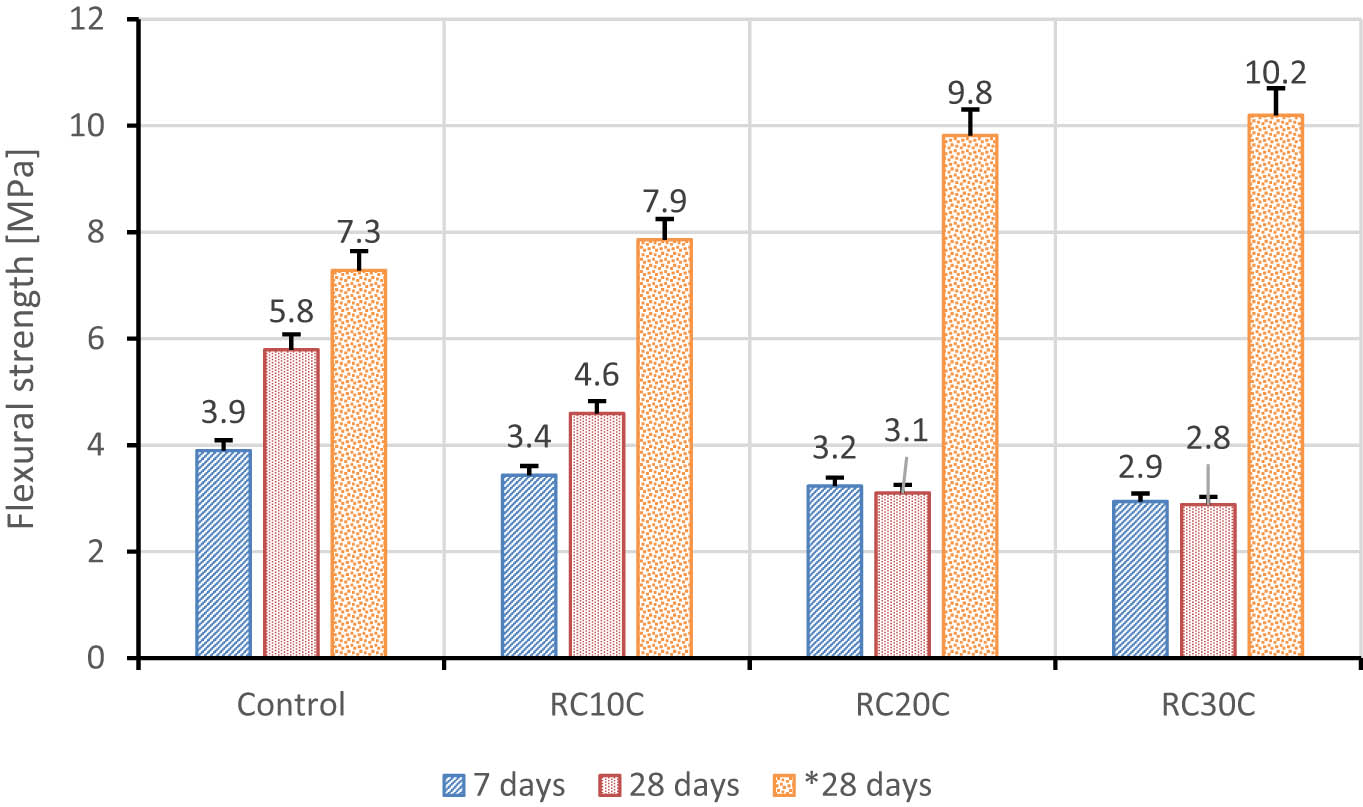

3.3 Flexural test

Figure 18 shows the results of flexural strength in which the samples corresponding to 7 and 28 days of curing with initial dosages exhibit the same behavior as in compressive strength: increasing the percentage of tailings caused a decrease in strength. In the RC20C and RC30C samples, there was a slight decrease from 7 to 28 days of curing. The control sample reached a strength of 5.79 MPa, followed by the 10% replacement of cement with tailings, which had a strength of 4.59 MPa. After 28 curing days, the replacements of 20 and 30% demonstrated strengths of 3.10 and 2.88 MPa, respectively.

Flexural strength result.

The results obtained for the adjusted dosages (*) are shown alongside the initial dosages. A change in the trend of the flexural test results with the adjusted dosages was observed, with this trend increasing as the amount of tailings replacing cement in the mortars increased. In this particular case, the highest flexural strength value was presented by the 30% cement replacement (10.2 MPa), and the lowest recorded value was that of the control sample (7.3 MPa), with a difference of 2.9 MPa between the control and RC30C values. Comparing the results obtained using the initial and adjusted dosages, it can be observed that the increase in these flexural strength values was on average 142%. In general, the flexural strength is about 10–20% of the compressive strength of concrete. In our result, the flexural strength results are about 12–31% of the compressive strength.

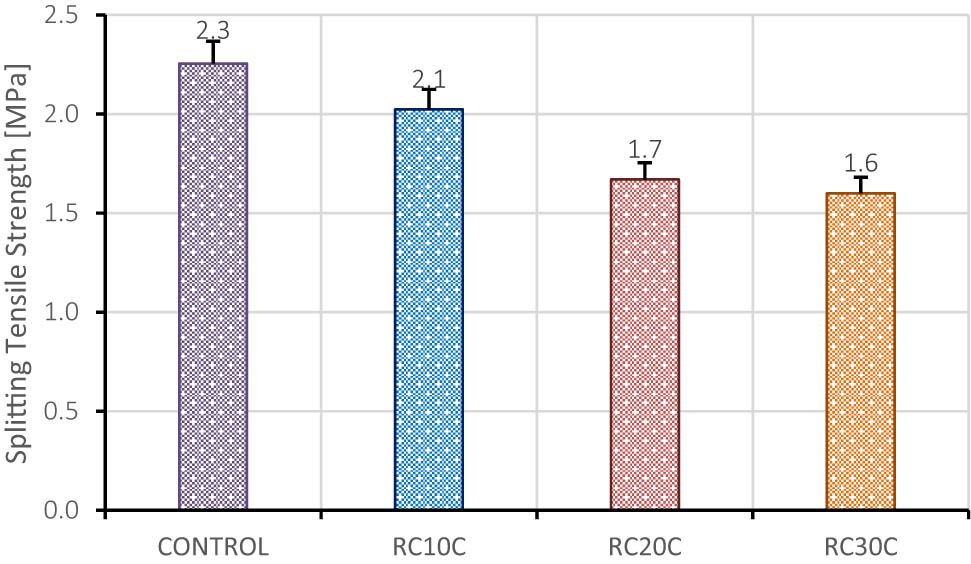

3.4 Splitting tensile strength

Figure 19 shows the results of splitting tensile strength in samples with 28 days of curing. A clear decrease in tensile strength was observed as the cement replacement increased, exhibiting the same behavior as in the previous compressive mechanical tests and decreasing from 2.25 to 1.6 MPa when comparing the control with RC30C. The splitting tensile strength results were about 11–14% of the compressive strength.

Splitting tensile strength results.

4 Discussion

This comparative study of the feasibility of replacing portions of the cement in mortar mixes with copper mine tailings revealed interesting results for the concrete industry. Here the findings are summarized in terms of chemical and mineralogical stability, workability, and mechanical behavior.

4.1 Chemical and mineralogical stability

To evaluate the results obtained by AAS of potentially hazardous elements present in tailing (Table 4), a review of different international regulations regarding the presence of these elements in soils was carried out. It should be noted that in Chile, the country where the study was carried out, there is no specific soil regulation in this regard. Table 11 displays various chemical elements along with the standards from different countries, indicating the maximum permissible limits for each element in soils for industrial or similar use. Comparing the values obtained here with those of the international regulations shown in Table 11, copper (Cu) and arsenic (As) values surpass the limits allowed in some cases. Despite this, given that these tailings would be integrated into the structure of the mortar, the possibility of these elements leaching and being released into the environment is much lower than the possibility of leaching from tailings dump; although to guarantee this, other types of tests would have to be carried out on the already-formed mortar.

Maximum concentration of elements allowed in soils for industrial use according to international regulations

| Element | Canada [63] | Australia [64] | Germany [64] | Swiss [65] | Brazil [66] | Italy [67] | Sweden [68] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg·kg−1 | mg·kg−1 | mg·kg−1 dry matter | mg·Kg−1 | mg·kg−1 dry matter | mg·kg−1 dry matter | mg·kg−1 | |

| Arsenic (inorganic) | 12 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 150 | 20 | 15 |

| Cobalt | 50 | 100 | — | 90 | 20 | 60 | |

| Copper | 63 | 1,000 | — | 1,000 | 600 | 120 | 200 |

| Chromium | 64 | 64 | 400 | 400 | — | 250 | |

| Lead | 140 | 300 | 400 | 2,000 | 900 | 100 | 300 |

| Nickel | 50 | 600 | 140 | 1,000 | 130 | 120 | 150 |

| Zinc | 200 | 7,000 | — | 2,000 | 2,000 | 150 | 700 |

It should be noted that the mineralogical composition of the tailings differs from that of the aggregates, the parent rock of the former being of the felsic type, while the aggregates used come from mafic rocks. However, this composition does not imply chemical incompatibility with that of the cement.

4.2 Workability

Workability, which is defined as the ease of transportation, placement, compaction, and finishing of the mixture, is an important property of fresh mortar or concrete mixtures. The physical properties of tailings have a significant impact on this parameter [16]. Since plasticity and cohesion are difficult to measure, consistency is frequently used as a measure of workability [69].

Analyzing the workability of mortars with fine aggregate dosages (Table 10), the mixtures lose fluidity as the percentage of tailings increases. Parthasarathi et al. [70] in a study in which they used gold mine tailings to make mortar determined that the workability of the mixture decreases with the higher the percentage of tailings used, which can be attributed to the presence of very fine particles in the tailings. Other researchers [19,20,21] also found that mortar flow decreased with increasing levels of tailings substitutions, justifying this because the tailings had a finer particle size distribution. This is probably not only due to the presence of smaller particles since they are in the size range of cement particles but also due to the presence of minerals from the clay group among the tailings components, which have a greater specific surface area than cement particles, given their laminar crystalline structure. These minerals adsorb water in abundance in their internal structure, preventing them from participating in the fluidization of the mixture, thus reducing its viscosity.

In this study, comparing the results of the samples prepared with fine and coarse aggregates, the fine preparations behave in a more viscous manner. Considering that the proportions of cement, water, aggregates, and tailings are equal, this can only be due to the friction generated between the aggregate particles in the mixture, which should be greater in the fine ones. Fine aggregates have a greater specific surface area than coarse aggregates; therefore, for the same proportion in the mixture, the larger particles will have fewer points of contact with each other, thus reducing friction. This lower friction between coarse aggregates translates into lower viscosity of the mortar. Other studies have also identified a lower workability of the mortar when it has fine aggregates compared to coarse ones [69].

Finally, the mixtures with adjusted dosages, despite having a lower water/solid ratio than the former (Table 7), present higher fluidity values. Taking into account the mixture components, this is justified by a lower proportion of fine aggregates in the mixture, especially concerning the cement content, which would cause the aggregate grains to have less friction, mainly between themselves due to greater dispersion, causing the viscosity of the mortar to decrease.

According to what was observed in this work, with the variables used, the main determining factor in the workability of the mortar seems to be the size of the aggregates. Various authors report the adverse effect of tailings used as a partial replacement of aggregate or cement on the workability of fresh concrete and mortar. Although the fluidity of the mortar can be modified by varying the dosage of water or using additives, these can have other effects such as a delay or acceleration in the beginning of setting [61]. For some kinds of applications, for instance, in the case of shotcrete, the incorporation of tailings material into the mixture can be useful to reduce the fluidity of the mortar due to the greater water retention of tailings material, which can then be adjusted to optimal workability conditions in a range between wet and plastic for use as shotcrete.

4.3 Mechanical behavior

Superior mechanical strengths were observed in samples with coarse aggregate compared to those containing fine aggregate at the same dosage, with a range of improvement from 20 to 23%. The larger particle size contributed to enhanced compressive strength by promoting greater interaction with the mortar matrix, facilitated by improved hydration of calcium silicate. However, the adjusted dosage using fine aggregates (*) considerably improved the mechanical strength, which would be expected, since the proportion of cement is doubled compared to the previous samples.

The influence of fine and coarse aggregates on compression tests has been evaluated in a variety of studies. The use of coarse sand improved the compression results compared to fine sand, as observed by Meddah et al. [71] suggesting that the compressive strength increases in correlation with the particle size distribution of the aggregate employed. Also, Ruiz [72] discovered that the compressive strength of concrete increased as the volume of coarse aggregate increased; however, when the aggregate volume fraction rises within the range of 45–75%, the compressive strength of concrete could slightly decrease (15%) and can be practically considered constant. Gou et al. [16] determined that for the same workability of mortar or concrete with tailings as fine aggregate, the compressive strength decreased since tailings need more water resulting in a higher water–cement ratio.

In addition to the direct effect of the significant increase in cement in the samples with dosage adjustment (*), indirectly, this would lead to the formation of high amounts of calcium hydroxide, which could have triggered an early pozzolanic reaction of certain minerals in the tailings, contributing to improving the strength of the mortar. On the other hand, the decrease in the water–cement ratio could also have had a favorable effect on the compressive strength of the mortars tested. In the work conducted by Haach et al. [69], all hardened properties evaluated (compressive strength, elastic modulus, and flexural strength) decreased with the increase in the water–cement ratio, while sand grading appeared to have no influence on compressive strength; however, sand granulometry had a significant impact on flexural strength. In their study, mortars made with coarse sand showed higher flexural resistance, as observed in this work and as Haach et al. pointed out, coarse sand likely promoted better particle entanglement.

A progressive increase in flexural strength value was observed in the mortar samples in which the adjusted dosage was used in comparison to the control sample (Figure 18) followed by 10, 20, and 30% replacement of cement with copper tailings. Other researchers [32,73] also found better results in flexion tests at higher proportions of tailings (with the adjusted dosage), which may be because the lower proportion of water favors the formation of calcium silicate bonds, increasing the bending strength. It is also suspected that this behavior is due to a slightly higher degree of hydration induced by the release of internal curing water.

The physical and chemical attributes of tailings utilized as fine aggregate in concrete have a direct impact on the mechanical properties of the concrete [51,74,75]. The general decrease in mechanical strengths is attributed to the fact that the replacement of tailings used lacks cementitious properties that would contribute to strength improvements. Therefore, progressively reducing the cement content in the mixture results in significant decreases in strength. It is also important to note the value obtained for the TOC in the copper tailings, which is above 4. The TOC content (Table 5) could have negatively affected the mechanical strengths in compression and flexure, as organic carbon may have formed a thin layer around cement particles, hindering their proper hydration and resulting in a potential decrease in strength. This effect is heightened in cases where copper tailings were extensively used as a substitute for cement. This behavior mirrors findings by researchers [76,77], who agree that higher TOC values lead to reduced durability and hardening properties of mortar samples due to partial inhibition or delay in cement hydration. On the other hand, international standard EN 197-1 [78] specifies that to achieve optimal behavior in mortar mixes, the TOC should not exceed 0.20 wt% for CEM II/A-LL and CEM II/B-LL types while the maximum TOC for CEM II/A-L and CEM II/B-L should not exceed 0.50 wt%.

Table 12 shows the results from various studies on replacing cement with tailings, based on different types of tailings, tests, and tailings content. The potential decrease in strength when adding tailings of all types may be attributed to the dosage used since not even the results of the control samples surpass any of the results from the references in Table 12. However, our study suggests that by adjusting the dosage, the mechanical properties of the mortar can be improved. Therefore, increasing the cement content should lead to an increase in strength – at least for the control sample – since there is no pozzolanic activity in the hydration process, there is no release of internal curing water from pre-moistened tailings as shown in [50], for the initial dosage used. The results of this study are in agreement with the findings from previous studies.

Results of mechanical tests on mortar/concrete samples with different types of tailings and cement replacement

| Tailing | Test | Cement content replaced by tailings (wt%) | Strength (MPa) (28 days of curing) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold | Compressive strength of mortar | 0 | 54.7 | [79] |

| 5 | 51.8 | |||

| 10 | 51.2 | |||

| 15 | 45.9 | |||

| 20 | 39.7 | |||

| 25 | 35.3 | |||

| Flexural strength of mortar | 0 | ∼8 | ||

| 5 | 7.6 | |||

| 10 | 7.5 | |||

| 15 | 6.8 | |||

| 20 | 6.9 | |||

| 25 | 6.6 | |||

| Iron (high silicon content) | Compressive strength of concrete | 0 | 44.1 | [30] |

| 10 | 42.3 | |||

| 20 | 38.9 | |||

| 30 | 38.3 | |||

| 40 | 32.3 | |||

| 0 | ∼14 | [19] | ||

| 5 | ∼3.8 | |||

| 10 | ∼3.8 | |||

| 25 | ∼4 | |||

| 50 | ∼7 | |||

| Flexural strength of mortar | 0 | ∼3.5 | ||

| 5 | 1–2 | |||

| 10 | — | |||

| 25 | — | |||

| 50 | — | |||

| Lead-Zinc | Compressive strength of concrete | 0 | ∼53 | [80] |

| 10 | ∼37 | |||

| Zinc, copper, and lead | Compressive strength of mortar | 0 | 55 | [52] |

| 5 | 52 | |||

| 10 | 46 | |||

| Gold | Compressive strength of mortar | 0 | 55 | |

| 5 | 48 | |||

| 10 | 45 | |||

| 0 | 32.5 | [81] | ||

| 10 | 29 | |||

| 20 | 31 | |||

| 30 | 33 | |||

| 40 | 32 | |||

| Iron | Compressive strength of concrete | 0 | 53 | [82] |

| 5 | 55 | |||

| 10 | 51 | |||

| 15 | 46 | |||

| 0 | 45 | [83] | ||

| 20 | 42 | |||

| 50 | 31 | |||

| Copper | Compressive strength of mortar using fine aggregate | 0 | 21.2 | This study |

| 10 | 18.2 | |||

| 20 | 13.2 | |||

| 30 | 11.1 | |||

| Compressive strength of mortar using coarse aggregate | 0 | 25.6 | ||

| 10 | 21.8 | |||

| 20 | 16.0 | |||

| 30 | 13.6 | |||

| Flexural strength of mortar | 0 | 5.8 | ||

| 10 | 4.6 | |||

| 20 | 3.1 | |||

| 30 | 2.9 | |||

| Splitting tensile strength of mortar | 0 | 2.3 | ||

| 10 | 2 | |||

| 20 | 1.7 | |||

| 30 | 1.6 | |||

| Compressive strength of mortar using fine aggregate (adjusted dosage) | 0 | 61.7 | ||

| 10 | 52.0 | |||

| 20 | 43.0 | |||

| 30 | 32.7 | |||

| Flexural strength of mortar (adjusted dosage) | 0 | 7.3 | ||

| 10 | 7.9 | |||

| 20 | 9.8 | |||

| 30 | 10.2 |

For tailings to exhibit pozzolanic material properties, it is necessary to have calcium hydroxide, typically supplied by hydrated Portland cement, which reacts with siliceous or silico-aluminous minerals. The tailings used in this work have high concentrations of silica and alumina (Table 5), although the high SiO2 content in these is present in the form of quartz, which is a chemically stable phase, so it does not generate this type of reaction. On the other hand, the presence of aluminosilicates such as kaolinite and muscovite (Table 6) could potentially give rise to this type of reaction although the resistance results obtained clearly do not reflect their pozzolanic activity. Despite this mineralogy present, due to the granulometry of the tailings, it would be expected that pozzolanic reactions would begin to take place in curing time periods greater than the 28 days analyzed here. Wu et al. [84] carried out studies with ground quartz particles, determining that the finest particles, with sizes less than 1 µm, are mainly responsible for the reactivity at early stages (up to 7 days). At later stages (28–90 days), particles of this mineral with diameters between 1 and 10 µm contribute to the pozzolanic reaction, providing compressive strength after 28 days of curing.

To develop the pozzolanic capacity of these minerals, abundant in these tailings, it would be useful to carry out interventions on them, such as calcination in the case of kaolinite, as described in numerous works [85,86,87], or mechanical activation by reducing the size of the muscovites by grinding, which increases their specific surface and reactivity [88]. Although the results of the resistance of the mortars have not been as expected by replacing cement with tailings, the abundance of aluminosilicates such as kaolinite and muscovite in these materials could potentially be used through thermal or mechanical treatments, developing their pozzolanic capacity to achieve improvements in their mechanical behavior.

5 Conclusion

Reusing tailings to replace cement in mortar mixes could be one way to reduce the growing stockpile of tailings and mitigate the deleterious effects of their buildup. To this end, this study evaluated the reuse of copper tailings in the manufacture of mortar. Findings show that the results in the flow test can be considered acceptable up to a 20% replacement with fine aggregates and 30% with coarse aggregate, but the mechanical strength values of these mortars are below the desired level, especially in terms of compressive and tensile strength. However, with adjustments in dosages – especially when the cement-to-water ratio is increased – improved mechanical strength values for both compressive and flexural strength can be obtained, as observed by others and confirmed in the present research. Moreover, when the dosage of copper tailings is adjusted, the flexural strength increases by almost 40% when replacing 30% of cement with copper tailings. Based on the results obtained in this study, it is feasible to use copper tailings for cement, achieving good results in its mechanical resistance, with the key being the correct balance of cement, water, and tailings in the mixture.

-

Funding information: The Chilean National Research and Development Agency, ANID/FONDEF/ID23I10183. F. Betancourt acknowledge ANID/ACT210030, ANID/FONDAP/1523A0001, ANID/FONDAP/15130015, and ANID BECAS/DOCTORADO NACIONAL 21241408.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Jones, H. and D. Boger. Sustainability and waste management in the resource industries. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, Vol. 51, 2012, pp. 10057–10065.10.1021/ie202963zSearch in Google Scholar

[2] Comisión Chilena del cobre Monitoreo Del Estado de Los Relaves Mineros En Chile, Ministerio de Minería, Santiago, Chile, 2022.Search in Google Scholar

[3] Tariq, A. and M. Nehdi. Developing paste backfill from heath steele mine sulphidic tailings using industrial by-products. Proceedings, Annual Conference - Canadian Society for Civil Engineering, 2005, 2005, id. GC-208.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Verburg, R. B. M. Use of paste technology for tailings disposal: Potential environmental benefits and requirements for geochemical characterization. IMWA Symposium, Vol. 2001, 2001, id. 13.Search in Google Scholar

[5] Bascetin, A., S. Tuylu, D. Adıguzel, and O. Ozdemir. New technologies on mine process tailing disposal. Journal of Geological Resource and Engineering, Vol. 4, 2016, pp. 63–72.10.17265/2328-2193/2016.02.002Search in Google Scholar

[6] Tuylu, S., A. Bascetin, and D. Adiguzel. The effects of cement on some physical and chemical behavior for surface paste disposal method. Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 231, 2019, pp. 33–40.10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.10.007Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[7] Cacciuttolo, C. and G. Perez Campomanes. Practical experience of filtered tailings technology in Chile and Peru: An environmentally friendly solution. Minerals, Vol. 12, 2022, id. 889.10.3390/min12070889Search in Google Scholar

[8] Cacciuttolo, C. and F. Valenzuela. Efficient use of water in tailings management: New technologies and environmental strategies for the future of mining. Water (Switzerland), Vol. 14, 2022, id. 1741.10.3390/w14111741Search in Google Scholar

[9] Williams, D. J. Lessons from tailings dam failures—Where to go from here? Minerals, Vol. 11, 2021, id. 853.10.3390/min11080853Search in Google Scholar

[10] Schoenberger, E. Environmentally sustainable mining: The case of tailings storage facilities. Resources Policy, Vol. 49, 2016, pp. 119–128.10.1016/j.resourpol.2016.04.009Search in Google Scholar

[11] Simms, P., M. Grabinsky, and G. Zhan. Modelling evaporation of paste tailings from the Bulyanhulu Mine. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, Vol. 44, 2007, pp. 1417–1432.10.1139/T07-067Search in Google Scholar

[12] Bouglada, M. S., N. Ammar, and B. Larbi. Optimization of cellular concrete formulation with aluminum waste and mineral additions. Civil Engineering Journal (Iran), Vol. 7, 2021, pp. 1222–1234.10.28991/cej-2021-03091721Search in Google Scholar

[13] Janković, K., N. Šušić, M. Stojanovic, B. Dragan, and L. Lončar. The influence of tailings and cement type on durability properties of self-compacting concrete. Tehnicki Vjesnik, Vol. 24, 2017, pp. 957–962.10.17559/TV-20160304113800Search in Google Scholar

[14] Pavez, O., L. González, H. Vega, and E. Rojas. Copper tailings in Stucco Mortars. Revista Escola de Minas, Vol. 69, 2016, pp. 333–339.10.1590/0370-44672015690148Search in Google Scholar

[15] Silva, E. J. D. A. and D. B. Mazzinghy. Evaluation of compressive strength in geopolymer mortars produced using iron ore tailings ground by tumbling ball mills. Tecnologia em Metalurgia, Materiais e Mineração, Vol. 18, 2021, id. e2480.10.4322/2176-1523.20212480Search in Google Scholar

[16] Gou, M. F., L. Zhou, and N. Then. Utilization of tailings in cement and concrete: A review. Science and Engineering of Composite Materials, Vol. 26, 2019, pp. 449–464.10.1515/secm-2019-0029Search in Google Scholar

[17] Zhao, S., J. Fan, and W. Sun. Utilization of iron ore tailings as fine aggregate in ultra-high performance concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 50, 2014, pp. 540–548.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.10.019Search in Google Scholar

[18] Saha, A. K., M. N. N. Khan, and P. K. Sarker. Value added utilization of by-product electric furnace ferronickel slag as construction materials: A review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Vol. 134, 2018, pp. 10–24.10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.02.034Search in Google Scholar

[19] Fontes, W., J. Mendes, S. Silva, and R. Peixoto. Mortars for laying and coating produced with iron ore tailings from tailing dams. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 112, 2016, pp. 988–995.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.03.027Search in Google Scholar

[20] Argane, R., M. Benzaazoua, R. Hakkou, and A. Bouamrane. A comparative study on the practical use of low sulfide base-metal tailings as aggregates for rendering and masonry mortars. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 112, 2016, pp. 914–925.10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.06.004Search in Google Scholar

[21] Xu, W., X. Wen, J. Wei, P. Xu, B. Zhang, Q. Yu, et al. Feasibility of kaolin tailing sand to be as an environmentally friendly alternative to river sand in construction applications. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 205, 2018, pp. 1114–1126.10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.119Search in Google Scholar

[22] Onuaguluchi, O. and Ö. Eren. Reusing copper tailings in concrete: Corrosion performance and socioeconomic implications for the Lefke-Xeros Area of Cyprus. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 112, 2016, pp. 420–429.10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.036Search in Google Scholar

[23] Onuaguluchi, O. and Ö. Eren. Cement mixtures containing copper tailings as an additive: Durability properties. Materials Research, Vol. 15, 2012, pp. 1029–1036.10.1590/S1516-14392012005000129Search in Google Scholar

[24] Xiong, C., W. Li, L. Jiang, W. Wang, and Q. Guo. Use of grounded iron ore tailings (GIOTs) and BaCO3 to improve sulfate resistance of pastes. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 150, 2017, pp. 66–76.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.05.209Search in Google Scholar

[25] Xiaoyan, H., R. Ravi, and V. C. Li. Feasibility study of developing green ECC using iron ore tailings powder as cement replacement. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 25, 2013, pp. 923–931.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0000674Search in Google Scholar

[26] Wu, P., C. Wang, Y. Zhang, L. Chen, W. Qian, Z. Liu, et al. Properties of cementitious composites containing active/inter mineral admixtures. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, Vol. 27, 2018, pp. 1323–1330.10.15244/pjoes/76503Search in Google Scholar

[27] Nouairi, J., W. Hajjaji, C.∼S. Costa, L. Senff, C. Patinha, E. Ferreira da Silva, et al. Study of Zn-Pb ore tailings and their potential in cement technology. Journal of African Earth Sciences, Vol. 139, 2018, pp. 165–172.10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2017.11.004Search in Google Scholar

[28] Zhang, D., S. Shi, C. Wang, X. Yang, L. Guo, and S. Xue. Preparation of cementitious material using smelting slag and tailings and the solidification and leaching of Pb2+. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, Vol. 2015, 2015, pp. 1–7.10.1155/2015/352567Search in Google Scholar

[29] Argane, R., M. Benzaazoua, R. Hakkou, and A. Bouamrane. Reuse of base-metal tailings as aggregates for rendering Mortars: Assessment of immobilization performances and environmental behavior. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 96, 2015, pp. 296–306.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.08.029Search in Google Scholar

[30] Cheng, Y., F. Huang, W. Li, R. Liu, G. Li, and J. Wei. Test research on the effects of mechanochemically activated iron tailings on the compressive strength of concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 118, 2016, pp. 164–170.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.05.020Search in Google Scholar

[31] Shettima A. U., M. W. Hussin, Y. Ahmad, and J. Mirza. Evaluation of iron ore tailings as replacement for fine aggregate in concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 120, 2016, pp. 72–79.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.05.095Search in Google Scholar

[32] Gupta, R. C., P. Mehra, and B. S. Thomas. Utilization of copper tailing in developing sustainable and durable concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 29, 2017, id. 04016274.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001813Search in Google Scholar

[33] Kiventerä, J., I. Lancellotti, M. Catauro, F. D. Poggetto, C. Leonelli, and M. Illikainen. Alkali activation as new option for gold mine tailings inertization. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 187, 2018, pp. 76–84.10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.182Search in Google Scholar

[34] Ye, J., W. Zhang, and D. Shi. Properties of an aged geopolymer synthesized from calcined ore-dressing tailing of bauxite and slag. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 100, 2017, pp. 23–31.10.1016/j.cemconres.2017.05.017Search in Google Scholar

[35] Zheng, K., J. Zhou, and M. Gbozee. Influences of phosphate tailings on hydration and properties of Portland Cement. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 98, 2015, pp. 593–601.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.08.115Search in Google Scholar

[36] Pyo, S., M. Tafesse, B.-J. Kim, and H.-K. Kim. Effects of quartz-based mine tailings on characteristics and leaching behavior of ultra-high performance concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 166, 2018, pp. 110–117.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.01.087Search in Google Scholar

[37] Zhu, X., W. Li, Z. Du, S. Zhou, Y. Zhang, and F. Li. Recycling and utilization assessment of steel slag in metakaolin based geopolymer from steel slag by-product to green geopolymer. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 305, 2021, id. 124654.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124654Search in Google Scholar

[38] Mahmoodi, O., H. Siad, M. Lachemi, and M. Sahmaran. Synthesis and optimization of binary systems of brick and concrete wastes geopolymers at ambient environment. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 276, 2021, id. 122217.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.122217Search in Google Scholar

[39] Divvala, S. and M. Swaroopa Rani. Early strength properties of geopolymer concrete composites: An experimental study. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 47, 2021, pp. 3770–3777.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.03.002Search in Google Scholar

[40] Moukannaa, S., A. Nazari, A. Bagheri, M. Loutou, J. G. Sanjayan, and R. Hakkou. Alkaline fused phosphate mine tailings for geopolymer mortar synthesis: Thermal stability, mechanical and microstructural properties. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, Vol. 511, 2019, pp. 76–85.10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2018.12.031Search in Google Scholar

[41] Manjarrez, L., A. Nikvar-Hassani, R. Shadnia, and L. Zhang. Experimental study of geopolymer binder synthesized with copper mine tailings and low-calcium copper slag. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 31, 2019, id. 04019156.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0002808Search in Google Scholar

[42] Raut, A. N., M. Adamu, V. C. Khed, A. L. Murmu, and Y. E. Ibrahim. Effects of agro-industrial by-products as alumina-silicate source on the mechanical and thermal properties of fly ash based-alkali activated binder. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 18, 2023, id. e02070.10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02070Search in Google Scholar

[43] Ahmari, S., X. Ren, V. Toufigh, and L. Zhang. Production of geopolymeric binder from blended waste concrete powder and fly ash. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 35, 2012, pp. 718–729.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.04.044Search in Google Scholar

[44] Ahmari, S., L. Zhang, and J. Zhang. Effects of activator type/concentration and curing temperature on alkali-activated binder based on copper mine tailings. Journal of Materials Science, Vol. 47, 2012, pp. 5933–5945.10.1007/s10853-012-6497-9Search in Google Scholar

[45] Kundu, S., A. Aggarwal, S. Mazumdar, and K. B. Dutt. Stabilization characteristics of copper mine tailings through its utilization as a partial substitute for cement in concrete: Preliminary investigations. Environmental Earth Sciences, Vol. 75, 2016, id. 227.10.1007/s12665-015-5089-9Search in Google Scholar

[46] Çelik, Ö., I. Y. Elbeyli, and S. Piskin. Utilization of gold tailings as an additive in Portland cement. Waste Management & Research, Vol. 24, 2006, pp. 215–224.10.1177/0734242X06064358Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[47] Franco de Carvalho, J. M., T. V. de Melo, W. C. Fontes, J. O. dos Santos Batista, G. J. Brigolini, and R. A. F. Peixoto. More eco-efficient concrete: An approach on optimization in the production and use of waste-based supplementary cementing materials. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 206, 2019, pp. 397–409.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.02.054Search in Google Scholar

[48] Zhang, G., Y. Yan, Z. Hu, and B. Xiao. Investigation on preparation of pyrite tailings-based mineral admixture with photocatalytic activity. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 138, 2017, pp. 26–34.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.01.134Search in Google Scholar

[49] Guo, Z., Q. Feng, W. Wang, Y. Huang, J. Deng, and Z. Xu. Study on flotation tailings of kaolinite-type pyrite when used as cement admixture and concrete admixture. Procedia Environmental Sciences, Vol. 31, 2016, pp. 644–652.10.1016/j.proenv.2016.02.118Search in Google Scholar

[50] Onuaguluchi, O. and Ö. Eren. Recycling of copper tailings as an additive in cement mortars. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 37, 2012, pp. 723–727.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.08.009Search in Google Scholar

[51] Arunachalam, K. P., S. Avudaiappan, N. Maureira, F. D. C. Garcia, S. Neves, I. D. Batista, et al. Innovative use of copper mine tailing as an additive in cement mortar. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, Vol. 25, 2023, pp. 2261–2274.10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.06.066Search in Google Scholar

[52] Sigvardsen, N. M., M. R. Nielsen, C. Potier, L. M. Ottosen, and P. E. Jensen. Utilization of mine tailings as partial cement replacement. Modern Environmental Science and Engineering, Vol. 4, 2018, pp. 365–373.Search in Google Scholar

[53] IS:3812 (Part-1). Pulverized fuel ash — Specification. Part 1: For Use as Pozzolana in cement, cement mortar and concrete (Second Revision). Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi, India, 2013, 1–14.Search in Google Scholar

[54] ASTM D 854. Standard test methods for of soil specific gravity solids by water pycnometer. ASTM Standards, Pensilvania, United States, 2018, 24.Search in Google Scholar

[55] Powers, M. C. A new roundness scale for sedimentary particles. Journal of Sedimentary Particles, Vol. 23, 1953, pp. 117–119.10.1306/D4269567-2B26-11D7-8648000102C1865DSearch in Google Scholar

[56] Maiza, P. J. and S. A. Marfil. Las Rocas Como Materiales Para Hormigón. Revista de Geología Aplicada a la Ingeniería y al Ambiente, Vol. 24, 2010, pp. 1–11.Search in Google Scholar

[57] ASTM C1437-20. Test method for flow of hydraulic cement mortar. ASTM Standards, Pensilvania, United States.Search in Google Scholar

[58] Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Laboratorio Virtual de Ensayo de Materiales- Laboratorio de Hormigón, https://www7.uc.cl/sw_educ/construccion/materiales/html/lab_h/mortero2.html (accessed on 12 January 2024).Search in Google Scholar

[59] Yurtdas, I. Experimental characterisation of the drying effect on uniaxial mechanical behaviour of mortar. Materials and Structures, Vol. 37, 2004, pp. 170–176.10.1617/13915Search in Google Scholar

[60] Yurtdas, I., H. Peng, N. Burlion, and F. Skoczylas. Influences of water by cement ratio on mechanical properties of mortars submitted to drying. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 36, 2006, pp. 1286–1293.10.1016/j.cemconres.2005.12.015Search in Google Scholar

[61] Garcia, S. and M. Ogaz. Shotcrete - Chilean Shotcrete Manual (in Spanish); Rojas, Lui., Instituto del Cemento y del Hormigón en Chile, Santiago, 2015. ISBN 244981.Search in Google Scholar

[62] Nabalón, G., V. Reyes, and H. Briones. Volumen No 8 Especificaciones Y Metodos De Muestreo, Ensaye Y Control Manual De Carreteras, Ministerio de obras publicas, Gobierno de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2008, 199-210.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Berthiaume, A., Galarneau, E., & Marson, G. Polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) in the Canadian environment: Sources and emissions. Environmental Pollution, Vol. 269, 2021, id. 116008.10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116008Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[64] Department of Environment and Conservation. Assessment levels for soil, sediment and water, Vol. Version 4, Department of Environment and Conservation, Western, Australia, 2010.Search in Google Scholar

[65] Confederation Suisse. Ordonnance 814.680: Sur l’assainissement des sites pollués. Berne, Suisse, 1998. (in French)Search in Google Scholar

[66] Conselho Nacional Do Meio Ambiente. RESOLUÇÃO No 420, Companhia Ambiental do Estado de São Paulo (CETESB): Brasil, 2009, pp. 81–84.Search in Google Scholar

[67] Commission, E. EUR 22805: Environmental risks of heavy metals in soil, 2007.Search in Google Scholar

[68] INSURE, I.S.R. EQS Limit and guideline values for contaminated sites; Innovative Sustainable Remediation, Sweden, 2017.Search in Google Scholar

[69] Haach, V., G. Vasconcelos, and P. Lourenco. Influence of aggregates grading and water/cement ratio in workability and hardened properties of mortars. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 25, 2011, pp. 2980–2987.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.11.011Search in Google Scholar

[70] Parthasarathi, N., B. Reddy, and K. S. Satyanarayanan. Effect on workability of concrete due to partial replacement of natural sand with gold mine tailings. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, Vol. 9, 2016, pp. 1–4.10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i35/99052Search in Google Scholar

[71] Meddah, S., Z. Salim, and S. Belâabes. Effect of content and particle size distribution of coarse aggregate on the compressive strength of concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 24, 2010, pp. 505–512.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.10.009Search in Google Scholar

[72] Ruiz, W. M. Effect of volume of aggregate on the elastic and inelastic properties of concrete, Master Thesis, Cornell University, 2006.Search in Google Scholar

[73] Onuaguluchi, O. and Ö. Eren. Rheology, strength and durability properties of mortars containing copper tailings as a cement replacement material. European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering, Vol. 17, 2013, pp. 19–31.10.1080/19648189.2012.699708Search in Google Scholar

[74] Alcayaga, A., M. V. Gutiérrez, S. Avudaiappan, R. E. Gómez, and F. Betancourt. Towards sustainable shotcrete in mining: A literature review on the utilization of tailings as a partial replacement for fine aggregate. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Mechanical Behaviour of Materials, Springer Nature, Switzerland, 2023, p. 197–207.10.1007/978-3-031-53375-4_13Search in Google Scholar

[75] Alcayaga Restelli, A., S. Avudaiappan, R. F. Arrué Muñoz, C. Canales, and R. Gómez. Tailings as a sustainable resource in 3D printed concrete for the mining industry: A literature review. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances on the Mechanical Behaviour of Materials, E. I. Saavedra Flores, Astroza, R., Das, R., eds., Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2024, pp. 89–107.10.1007/978-3-031-53375-4_7Search in Google Scholar

[76] Tosun, K., B. Felekoğlu, B. Baradan, İ. A. Altun, B. Felekoǧlu, B. Baradan, et al. Effects of limestone replacement ratio on the sulfate resistance of portland limestone cement mortars exposed to extraordinary high sulfate concentrations. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 23, 2009, pp. 2534–2544.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2009.02.039Search in Google Scholar

[77] Diab, A. M., I. A. Mohamed, and A. A. Aliabdo. Impact of organic carbon on hardened properties and durability of limestone cement concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 102, 2016, pp. 688–698.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.10.182Search in Google Scholar

[78] European Commitee EN 197-1. Cement - Part 1: Composition, specifications and conformity criteria for common cements. Official Journal of the European Union, EN 197-1:2000 E 2000, 91.100.10, 1–29.Search in Google Scholar

[79] Kunt, K., M. Yildirim Ozen, F. Dur, E. Derun, and S. Pişkin. Utilization of Bergama gold tailings as an additive in the mortar. Celal Bayar Üniversitesi Fen Bilimleri Dergisi, Vol. 11, 2015, pp. 365–371.10.18466/cbujos.89776Search in Google Scholar

[80] Liang, X., D. Yuan, C. Wang, S. Jiao, and Y. Zhang. Preparation of C30 concrete using lead-zinc tailings. Chemical Engineering Transactions, Vol. 62, 2017, pp. 937–942.Search in Google Scholar

[81] Ince, C. Reusing gold-mine tailings in cement mortars: Mechanical properties and socio-economic developments for the Lefke-Xeros area of cyprus. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 238, 2019, id. 117871.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.117871Search in Google Scholar

[82] Liu, Y., W. Hao, W. He, X. Meng, Y. Shen, T. Du, et al. Influence of dolomite rock powder and iron tailings powder on the electrical resistivity, strength and microstructure of cement pastes and concrete. Coatings, Vol. 12, 2022, id. 95.10.3390/coatings12010095Search in Google Scholar

[83] Wang, H., F. Han, S. Pu, and H. Zhang. Properties of blended cement containing iron tailing powder at different curing temperatures. Materials, Vol. 15, 2022, pp. 1–14.10.3390/ma15020693Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[84] Wu, P., X. Lyu, J. Wang, and S. Hu. Effect of mechanical grinding on the hydration activity of quartz in the presence of calcium hydroxide. Advances in Cement Research, Vol. 29, 2017, pp. 269–277.10.1680/jadcr.16.00159Search in Google Scholar

[85] Bich, C., J. Ambroise, and J. Péra. Influence of degree of dehydroxylation on the pozzolanic activity of metakaolin. Applied Clay Science, Vol. 44, 2009, pp. 194–200.10.1016/j.clay.2009.01.014Search in Google Scholar

[86] Sánchez, I., I. S. de Soto, M. Casas, R. Vigil de la Villa, and R. García-Giménez. Evolution of metakaolin thermal and chemical activation from natural kaolin. Minerals, Vol. 10, 2020, id. 534.10.3390/min10060534Search in Google Scholar

[87] Liu, Y., Q. Huang, L. Zhao, and S. Lei. Influence of kaolinite crystallinity and calcination conditions on the pozzolanic activity of metakaolin. Gospodarka Surowcami Mineralnymi-Mineral Resources Management, 2021, pp. 39–56.Search in Google Scholar

[88] Yao, G., H. Zang, J. Wang, P. Wu, J. Qiu, and X. Lyu. Effect of mechanical activation on the pozzolanic activity of muscovite. Clays and Clay Minerals, Vol. 67, 2019, pp. 209–2016.10.1007/s42860-019-00019-ySearch in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Towards sustainable concrete pavements: a critical review on fly ash as a supplementary cementitious material

- Optimizing rice husk ash for ultra-high-performance concrete: a comprehensive review of mechanical properties, durability, and environmental benefits

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future