Abstract

Wollastonite glass doped with or without 0.5 and 1.0% Fe2O3 was synthesized using a melt-quenching procedure in order to produce new bioactive implants with appropriate magnetic properties. When glasses were sintered at either 1,100 or 1,200°C, combeite (Ca1.543Na2.914Si3O9), pseudowollastonite (Ca3Si3O9), and wollastonite (CaSiO3) with traces of hematite (Fe2O3) in highest Fe-containing sample were obtained. Upon examining the sintered samples at 1,200°C using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM), a variety of irregular grains composed of submicron-sized particles were found. Using dynamic light scattering (DLS), the colloidal stability of wollastonite and its composites with Fe2O3 was investigated. The distribution of particle sizes was between approximately 1 μm and 190 nm, and the zeta potential was negative. The Fe2O3 composition of the sintered samples exhibited a variety of magnetic behaviors. FT-IR reflection was used to assess the produced materials’ biocompatibility after a month of immersion in SBF. The soaked samples confirmed that

1 Introduction

Wollastonite, a calcium metasilicate (CaSiO3, CS), was developed to address biocompatibility in glass systems intended to be biomaterials. Additionally, non-cytotoxic and osteoconductive wollastonite has been considered an alloplast bioactive material for bone repair [1,2]. Traces of iron, magnesium, manganese, potassium, sodium, and aluminum may also be present in wollastonite. It may contain 51.7% silicon dioxide and 48.3% calcium oxide. It is made of limestone or calcium carbonates, which are heated to extremely high temperatures in the presence of fluids containing silica [3]. It was discovered that transition metal ions, particularly iron, show uncommon magnetic properties at the solvability frontier of iron oxide and that anti-ferromagnetic transition metal ion groups are present in oxide glasses. The precipitates or nanocrystalline domains showed predicted magnetization due to the potential group in the glass matrix [4]. Iron is supplied at concentrations greater than 5 mol%, which more easily simulates a network former than a modifier [5]. To provide well-considered structural support, metal ions were added to wollastonite as a dopant. In this context, Taha et al. found that osteogenesis and maturation increased when the Fe2O3 nanoparticle concentration increased. Fe2O3 and CS work together to enhance bone formation in a coordinated manner [6]. They claimed that there is insufficient study describing the nanostructure produced by doping calcium silicate with Fe2O3. Because of their extensive use in biological, permanent, and magnetic sensors, materials with magnetic properties have attracted a lot of interest. In the field of nanomedicine, magnetic nanoparticles (M-NPs) are a type of nanomaterial that has been regularly planned for its possible uses. Presentations on drug and gene delivery, hyperthermia rehabilitation, diagnostics, and magnetic imaging have all made use of them [7]. Hematite (α-Fe2O3), maghemite (γ-Fe2O3), and magnetite (Fe3O4) are the three types of iron oxide nanoparticles that are most frequently used for medical applications [8]. These altered designs have several interesting features, such as improved stability in the magnetic field, decreased oxidation sensitivity, and biocompatibility. Hyperthermia is a promising and effective cancer therapy strategy among traditional treatments [1].

Currently, localized perfusion with heated blood, microwave, ultrasound, or any other electromagnetic energy source is used to treat clinical hyperthermia. However, the main challenge in employing these methods is their inability to regulate local tumor heating without causing harm to healthy tissues. Furthermore, intrusive heat is employed in the majority of these therapy techniques. Therefore, magnetic bioactive glass-ceramics have been shown to heat cancer cells without causing harm to healthy tissues, as mentioned by Oskoui and Rezvani [9]. The stability and biomineralization of the graft may be enhanced by the presence of iron oxide (Fe2O3) as a dopant material. In the process of bone regeneration, namely in the development of osteoblastic cells, iron particles are important [10]. It was also taken into account for the bioactive material that was exchanged with Fe2O3, which improved the potential for apatite synthesis [11]. A constant equilibrium between biomineral synthesis and appropriate magnetic properties is necessary for the material to remain nontoxic. Fe2O3, also known as hematite, is an inorganic ferric oxide that is regarded as a paramagnetic mineral with only the Fe3+ oxidation state, whereas Fe3O4, also known as magnetite, is a mixed ferromagnetic material that consumes both Fe2+ and Fe3+ oxidation states of iron. This is the main distinction between the two minerals. Fe2O3 exists in two polymorphs: the gamma and alpha phases. The structure of the alpha phase is symmetrical, but the gamma Fe2O3 is structured in a cubic fashion. Fe3O4 has an inverted spinel structure, which is cubic in shape. In contrast to Fe2O3, which has a relatively low output, Fe3O4 distribution is little more complex and time-consuming [12].

The objective of this study was to examine the incorporation of iron ions into the calcium silicate matrix. In vitro biomineralization as well as size, shape, and physical features were found to be influenced by iron incidence.

2 Materials and methods

How ferric oxide (Fe2O3) affected the wollastonite glass’s bioactivity and characterization was determined. The components of wollastonite (CaSiO3) glass were as follows: SiO2 from silica sand (white silica sand), iron oxide (Fe2O3; Sigma Aldrich 96%), and calcium oxide (CaO) from limestone (CaO: 55.7, Al2O3: 0.22, Fe2O3: 0.02, MgO: 0.1, Na2O: 0.1, K2O: 0.16, and TiO2: 0.02 wt%). The batch compositions with and without Fe2O3 are displayed in Table 1. The addition of 5.0% Na2O (from Na2CO3-BDH) lowered the melting point. To obtain a powder with a grain size of less than 0.038 mm, the batches were thoroughly combined in a ball mill using the melt-quenching process. A global electrical furnace was used to melt the batches in platinum crucibles, with melting points in the range of 1,400–1,450°C.

Constituents and chemical composition of glass batches

| Samples | Batch in oxides | Batch | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | SiO2 | Over 100% addition | Starting material | |||||

| Na2O | Fe2O3 | L.S | Silica sand | Na2CO3 | Fe2O3 | |||

| G0 | 48.28 | 51.72 | 5.00 | 00 | 86.68 | 51.72 | 8.5 | 0.00 |

| G0.5Fe | 48.28 | 51.72 | 5.00 | 0.25 | 86.68 | 51.72 | 8.5 | 0.50 |

| G1.0Fe | 48.28 | 51.72 | 5.00 | 0.50 | 86.68 | 51.72 | 8.5 | 1.00 |

Differential thermal analysis (DTA-Perkin Elmer DTA-7, USA) was used to determine the thermal history of the glass samples. The glass powder was found at a heating rate of 20°C per minute. The glass was sintered at 1,100 and 1,200°C for 2 h and X-ray diffraction (XRD-BRUKER, D8 ADVANCED, CuO target, = 1.54, Germany) was used to identify the crystalline phases. Field emission scanning electron microscopy combined with energy dispersive X-ray microanalysis (FE-SEM/EDX, model FEJ Quanta 250 Fei, Holland) was used to confirm the microcrystalline structure of sintered glass samples. Fresh crystalline surfaces were etched using a solution of 1% HNO3 + 1% HF before FE-SEM scanning.

With an accuracy of over 1 ± 0.2% and within the range of 0.1 × 10−6 to 103 (emu) of moment measurement, the magnetic characteristics of the powder were assessed using a Lake Shore-7410 vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) with a magnetic field of 20 kOe.

The Zetasizer (Zeta Potential Analyzer, Nano ZS, Malvern Instrument Ltd, UK) was used to measure the hydrodynamic diameter (particle size), polydispersity index (PDI), and zeta potential of evenly distributed powdered materials at 25°C. For the most promising detection, a 633 nm laser was used. To obtain a concentration of 20 mg·ml−1, the powder was spread out and diluted with distilled water. A particular piece of software (Version 4.0) was utilized for data analysis; each measurement was an average of 12 runs. With the use of an appropriate microscopic procedure, the zeta potential was bestowed upon the voltage of the applied electricity and the mobility of particles under the action of the electricity.

The presence or absence of the calcium phosphate layer on the fresh surface of the synthetic sintered glass-ceramic discs was examined using SBF, which had the same composition as human blood plasma [13]. By incubating sintered discs in SBF for a month at 37°C, the hydroxyapatite formed on the sample surfaces was examined. Kokubo’s method was used to create SBF, which entailed dissolving appropriate concentrations of reagent-grade chemicals in deionized water, including NaCl, NaHCO3, KCl, Na2HPO4, MgCl2·6H2O, Na2SO4, (CH2OH)3CNH2, and CaCl2·H2O [14]. Tris-hydroxymethyl amino methane [(CH2OH)3CNH2] and 1 M HCl were added to the SBF solution to adjust its pH to 7.4 and equal to the content of human blood plasma [15]. Glass discs that were sintered at 1,200°C underwent bioactivity tests. For a month, the samples were kept in closed, sterile polyethylene vials that contained SBF. Samples were taken out of the solution after a month, rinsed with distilled water to stop the reaction, and allowed to dry at room temperature. FE-SEM/EDX and FT-IR reflection (Jasco, FT/IR-4600, USA) are used to characterize disc samples following SBF in order to ensure the establishment of a hydroxyl calcium phosphate layer.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Sample characterization

3.1.1 DTA and XRD analysis

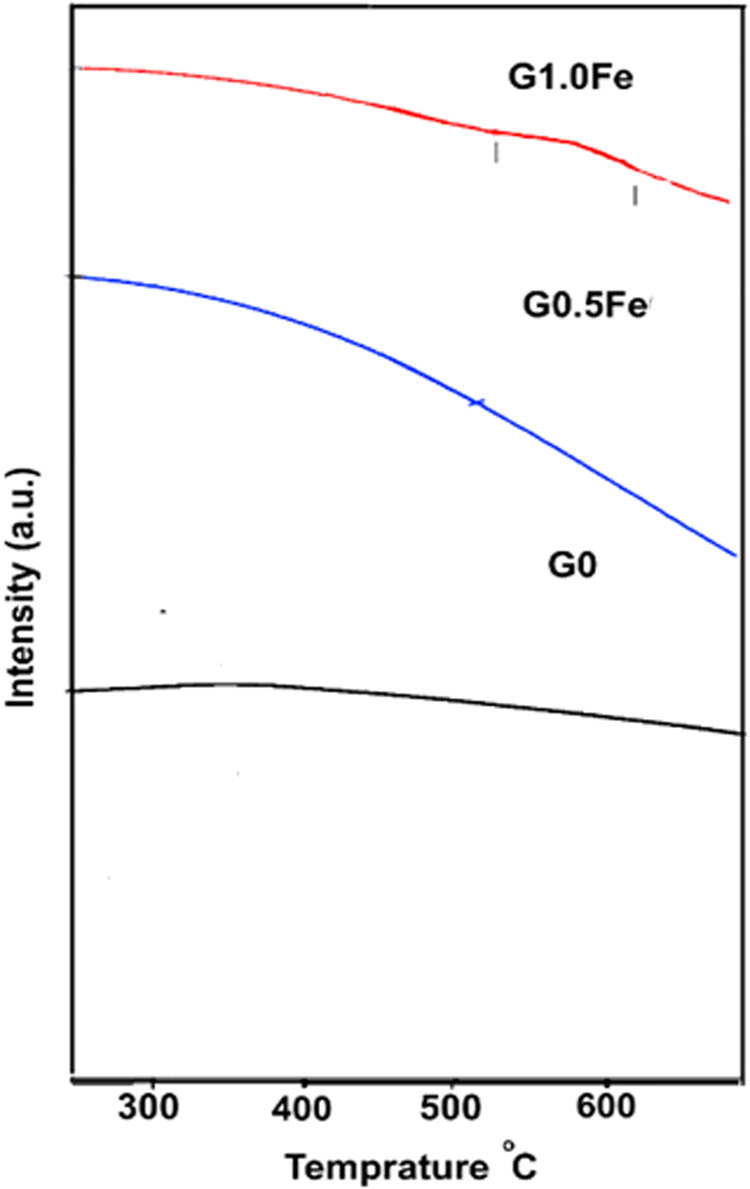

With the exception of the G1.0Fe sample, the available thermal history of DTA up to 750°C did not reveal any signs of an exothermic or endothermic action. The exothermic crystallization process involves a phase change from an unstable to a stable state. The broad exothermic peak in the DTA curve of the G1.0Fe sample between 508 and 695°C indicates the glass crystallization processes (Figure 1). However, the glass discs were sintered at 1,100 and 1,200°C to provide high-quality sintered samples.

DTA curves of G0, G0.5Fe, and G1.0Fe glasses.

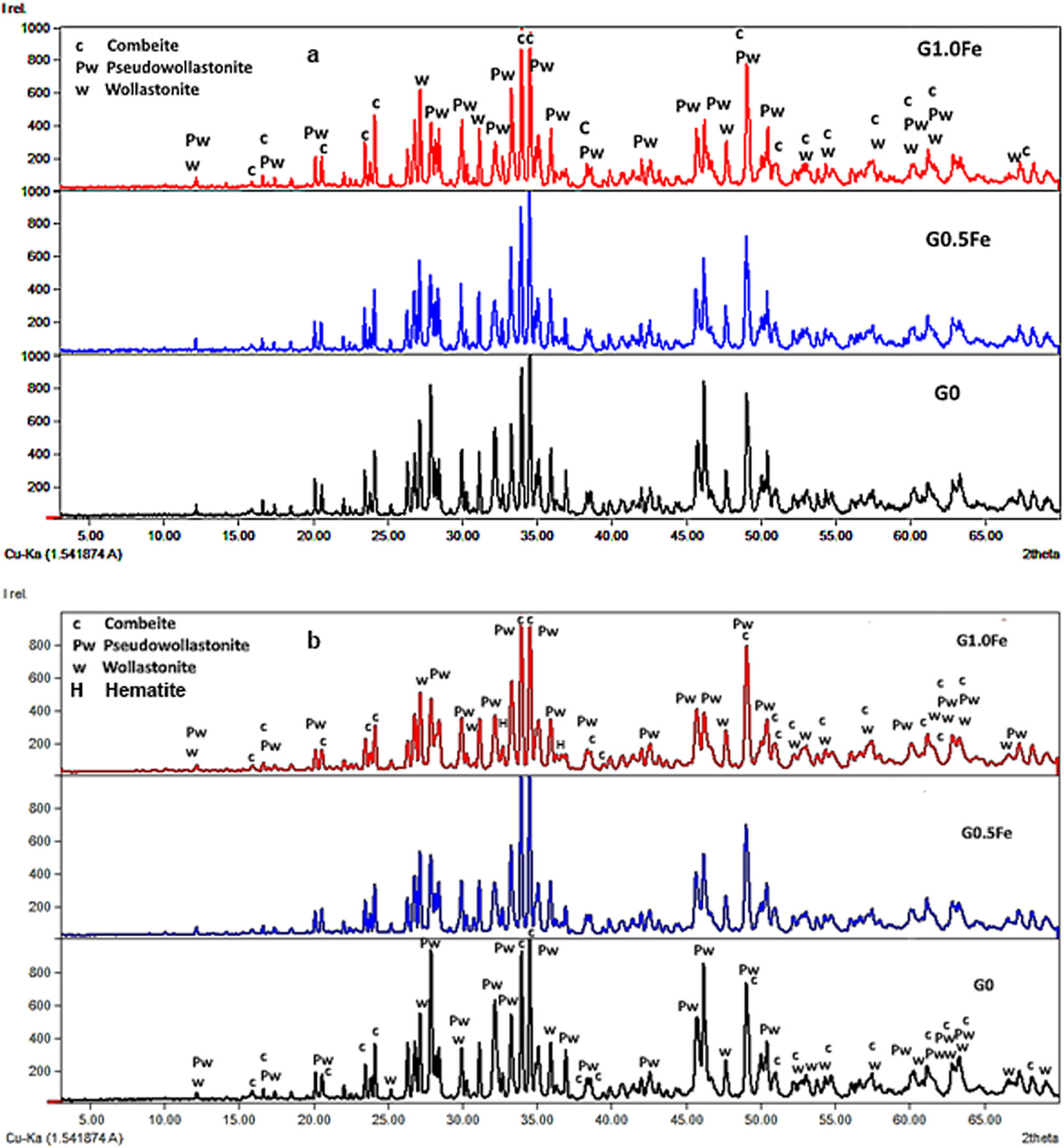

X-ray diffraction patterns of samples sintered at 1,100 and 1,200°C showed that, in addition to pseudowollastonite (CaSiO3, ICDD: 96-900-2180) and wollastonite (CaSiO3, ICDD: 96-900-5779), combeite (Ca1.543Na2.914Si3O9, ICDD: 96-900-7712) is crystallized as a significant phase (Figure 2(a) and (b)). However, traces of hematite were developed in high Fe-containing G1.0Fe sample (Fe2O3, ICDD: 96-901-5965). It forms the primary phase with CaO and SiO2 despite the low ratio of Na2O; however, the crystallization of both pseudowollastonite and wollastonite allowed Na2O to form a phase that contained Ca silicate (combeite, Ca1.543Na2.914Si3O9). The energy of combeite formation may also be thought to be lower than that of pseudowollastonite and wollastonite. The primary constituents of combeite, which is a bioactive silicate, are Na2O, CaO, and SiO2, which are extremely similar to the composition of bioactive compounds. Its crystallization can improve the biocompatibility of glass ceramics that are produced [9,16].

X-ray diffraction patterns of G0, G0.5Fe, and G1.0Fe glasses sintered at (a) 1,100°C and (b) 1,200°C.

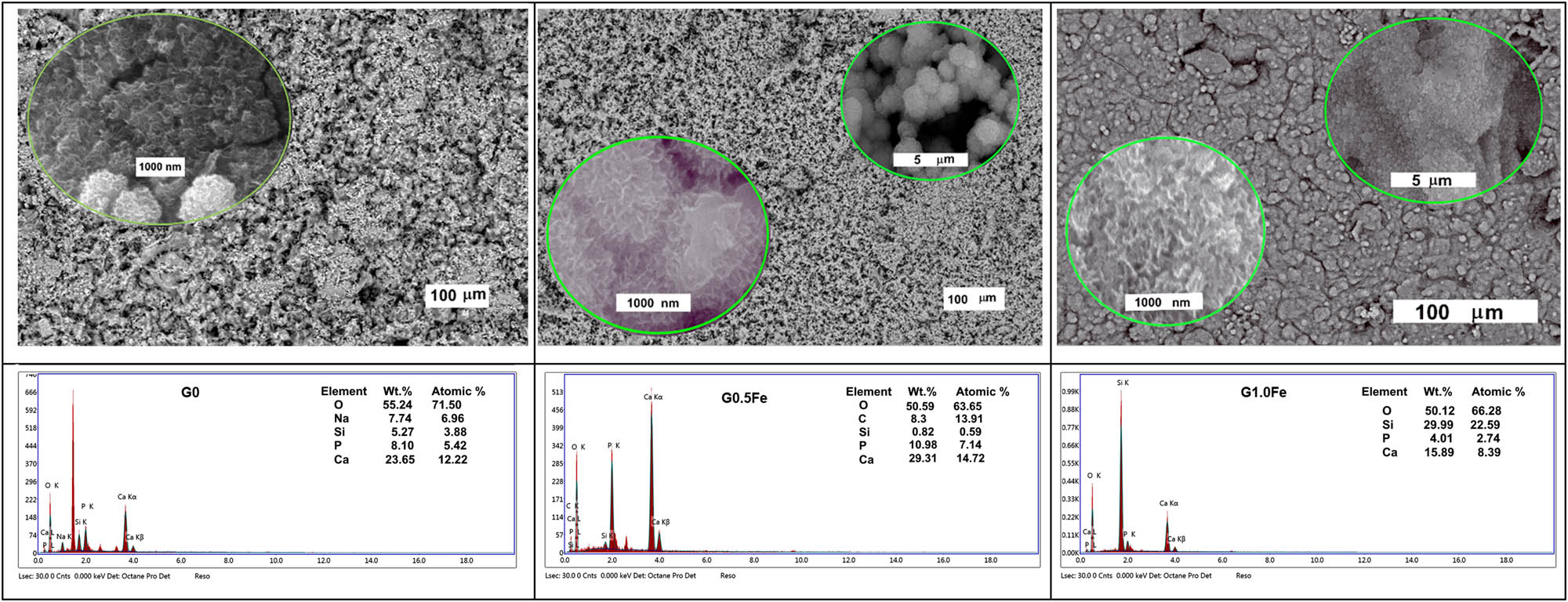

3.1.2 FE-SEM/EDX analysis

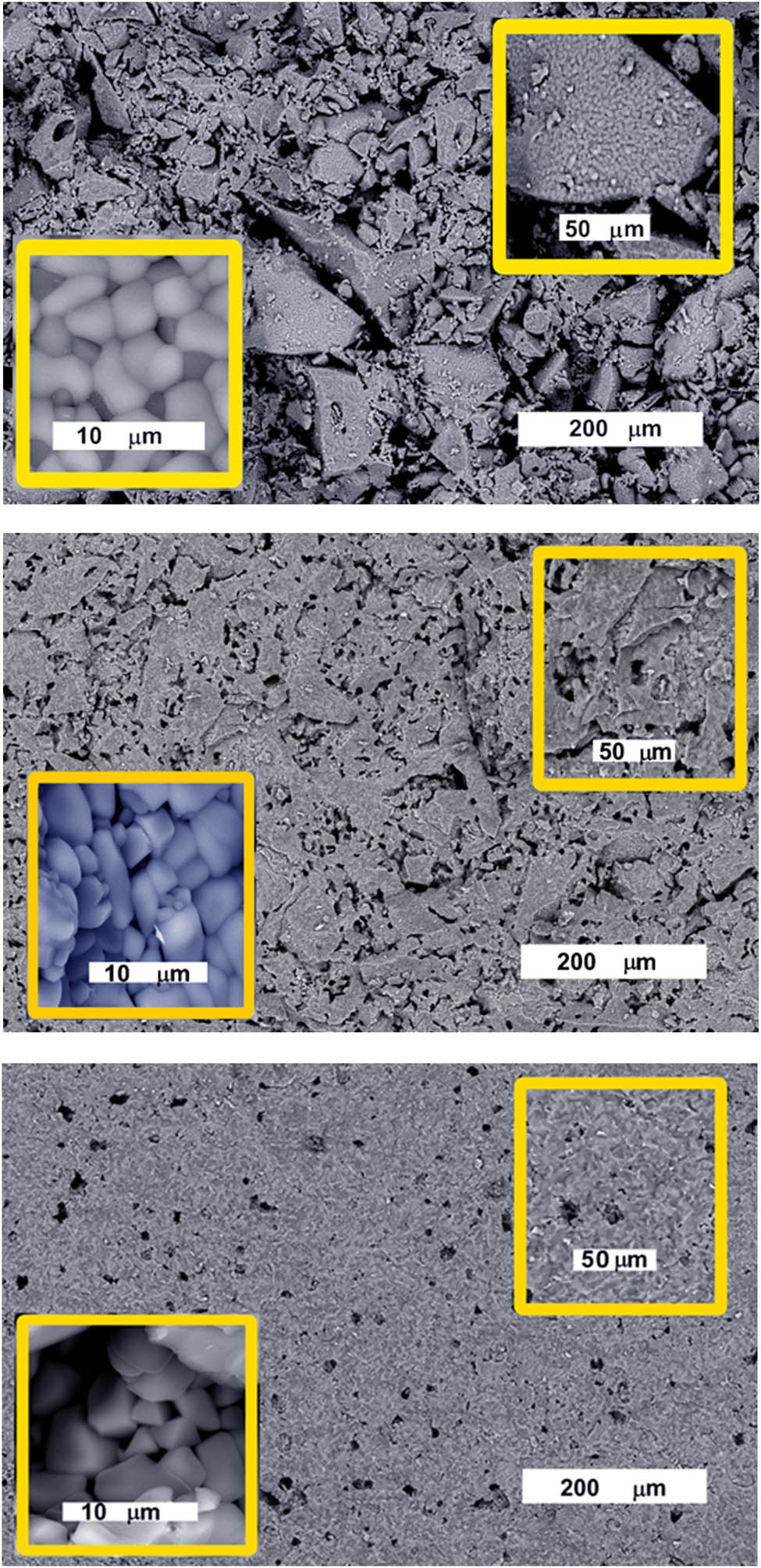

The microstructures of the sintered samples at 1,200°C are depicted in the FE-SEM images (Figure 3). As the Fe2O3 content increases (X = 500 times), the microstructures show irregular grains with decreasing intergrained gaps at high magnification (X = 1,500); however, the grains display dispersed particles embedded in the glassy matrix (Figure 3). However, distinct euhedral crystals in the glassy groundmass were seen at higher magnification (X = 12,000), particularly in the G1.0Fe sample.

SEM images of G0, G0.5Fe, and G1.0Fe glasses sintered at 1,200°C.

3.1.3 Particle size distribution and zeta potential analysis

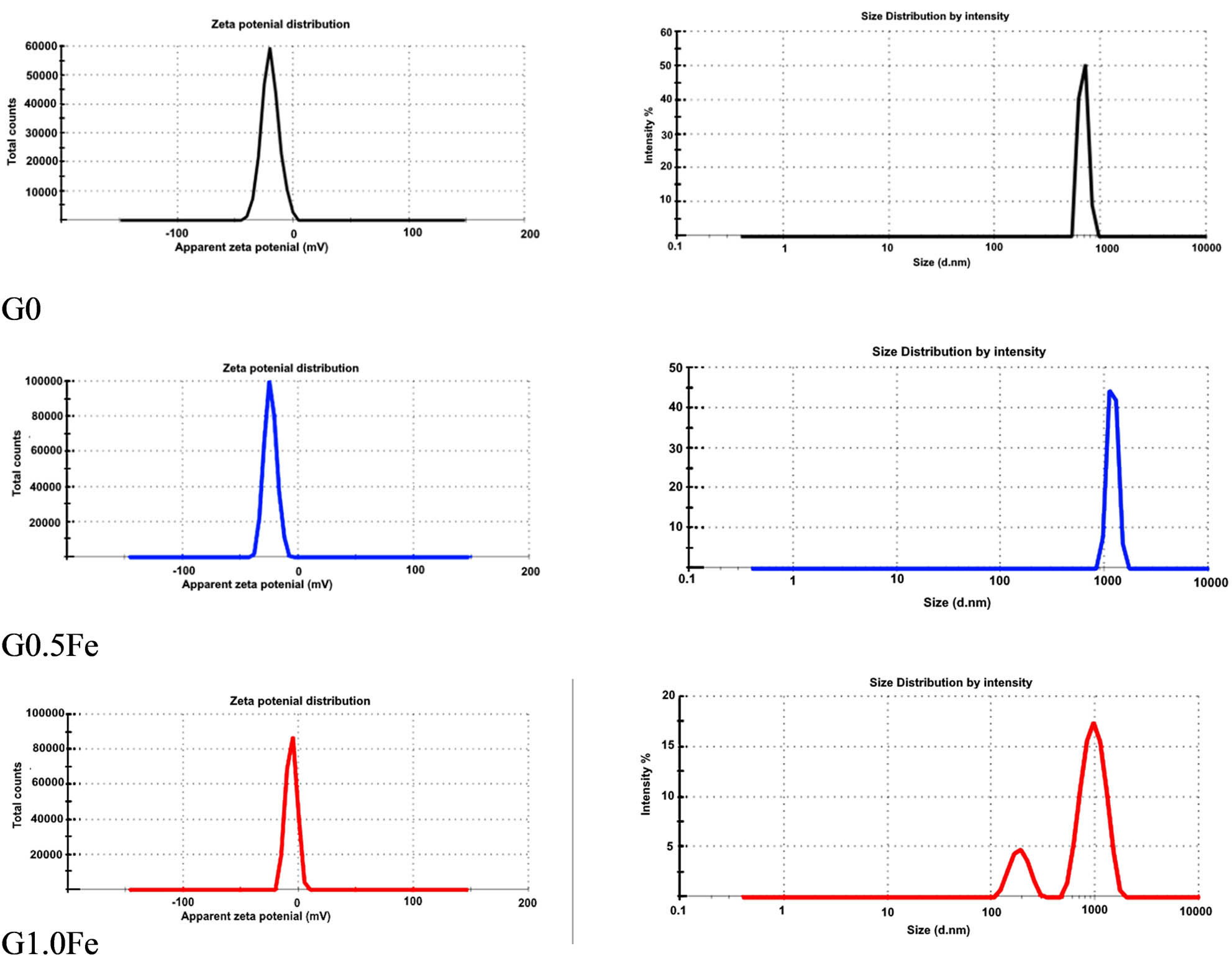

Using zeta-potential (ξ) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) techniques, the colloidal stability of wollastonite (G0) and its composites with Fe2O3 (G0.5Fe and G1.0Fe) was investigated. From G0 to G1.0Fe, the (PDI) displayed a decreasing order. According to Alangari et al. [17], the limited size distribution of the produced material for the G1.0Fe sample is approved by the low PDI value. As the Fe2O3 content increased, it was observed that the apparent zeta potential of all sintered samples at 1,200°C/2 h displayed a negative trend (Figure 4). When implanted in bone, such an observation might be a useful characteristic for samples that include live cells [17]. The average values of the 12 runs of ζ are shown in Table 2 and Figure 4, which show the zeta potential distribution (G0: −19.8 ± 7.5 mV, G0.5Fe: −24.0 ± 5.38, and G1.0Fe: −6.2 ± 4.71) as well as the size distribution by number (G0: 665.8 nm, GFe0.5: 1167 nm, GFe1.0: approximately 800.5 and 169.2 nm) [18]. Note that the decrease in the particle leads to increase in the surface area and, consequently, increase in the precipitation of the apatite phase. This is clear in G0 (665.8 nm), G0.5Fe (1,167 nm), and G1.0Fe (800.5–1689.2 nm).

Apparent zeta potential and particle size distribution of the sintered samples at 1,200°C/2 h.

Particle size, PDI, and apparent zeta potential for powder samples sintered at 1,200°C

| Samples | Apparent zeta potential (mV) | Zeta deviation (mV) | Particle size (d·nm) | PDI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak 1 | Peak 2 | |||||

| G0 | −19.8 | 7.50 | 665.8 | — | 0.841 | |

| G0.5Fe | −24.0 | 5.38 | 1,167 | — | 0.781 | |

| G1.0Fe | −6.20 | 4.71 | 800.5 | 169.2 | 0.619 | |

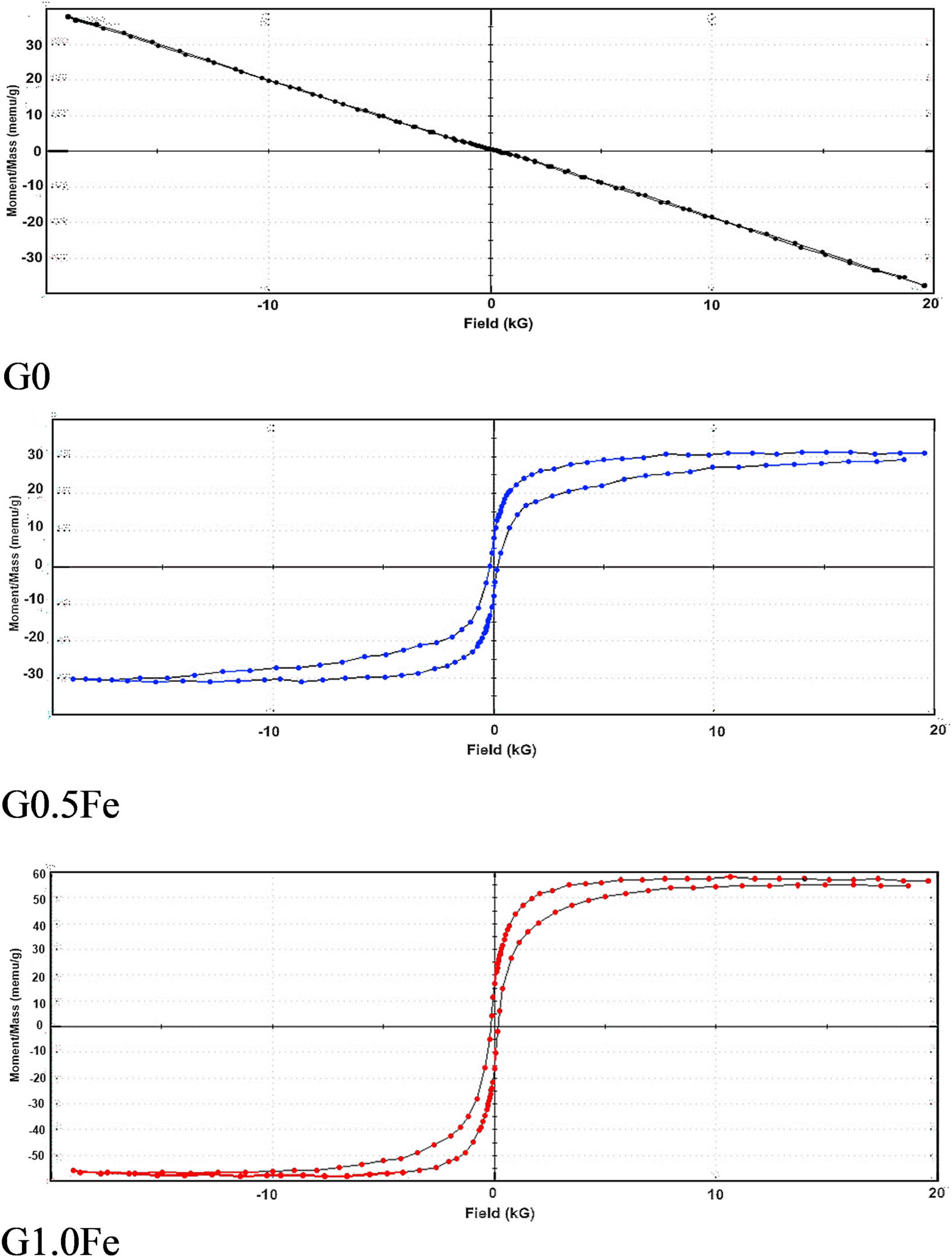

3.1.4 Magnetic analysis

All of the sintered discs were evaluated using a magnetometer at 1,200°C for 2 h, with or without Fe2O3. The wollastonite structure may exhibit a potential calcium exchange in the samples [19]. According to Akamatsu et al. [20], the influence of anion deficit on the magnetic characteristics was triggered by the presence of various iron valence states. The magnetic characteristics for the samples are shown in Table 3, and the M–H hysteresis curves of base G0 and those containing 0.5 (G0.5Fe) and 1.0% (G1.0Fe) of Fe2O3 at room temperature (RT) are shown in Figure 5. The magnetic types of the two glass-ceramic specimens, G0.5Fe and G1.0Fe, were similar. The materials under study exhibited a range of coercivity (Hci) from 23.248 to 175.39 (G), remnant magnetization (Mr) alternating between 35.502 × 10−6 and 15.814 × 10−3 (emu/g), squareness from 943.59 × 10−6 to 0.27141, and saturation magnetization (Ms) from 37.625 × 10−3 to 58.266 × 10−3 (emu/g) [21]. Therefore, Ms, Hci, Mr, and Mr/Ms values were enhanced when the Fe2O3 content of the materials was increased compared to the base. It is evident from Figure 5 that pure wollastonite behaves in a diamagnetic fashion [3]. As for the integration of 0.5 and 1.0% Fe2O3, there was notable conduct as a ferromagnetic and a paramagnetic material, respectively [10,22]. Consequently, the magnetization of the G0 base doped with Fe2O3 (G0.5Fe and G1.0Fe) improved as the iron replacement increased. The Ms values of G0.5Fe and G1.0Fe were 0.0312 and 0.05826 (emu/g), respectively, due to the addition of iron ions to the wollastonite structure. The G0.5Fe and the G1.0Fe curves exhibit a thin hysteresis cycle and low coercive field found in soft magnetic materials. Thus, a transition metal ion, such as iron, may be chosen to enhance the magnetic characteristics. For a month at 37°C in the current magnetic field, the bioactivity was active in SBF, as shown in the next section on bioactivity, enabling the cells to easily become viable. In the base G0 sample, the traces of iron either from limestone or the additive ingredient may cause the magnetism.

Room temperature M–H loops of G0, G0.5Fe, and G1.0Fe glass samples sintered at 1,200°C.

Magnetic parameters of the sintered samples measured at room temperature for the samples sintered at 1,200°C

| Samples | Total loop area (erg/g) | Coercivity Hci (G) | Saturation magnetization Ms (emu/g) × 10−3 | Remanence magnetization Mr (emu/g) | Squareness SQR (Mr/Ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0 | 11.583 | 23.248 | 37.625 | 35.502 × 10−6 | 943.59 × 10−6 |

| G0.5Fe | 167.00 | 173.94 | 31.262 | 7.4988 × 10−3 | 0.23987 |

| G1.0Fe | 171.89 | 175.39 | 58.266 | 15.814 × 10−3 | 0.27141 |

3.2 Bioactivity

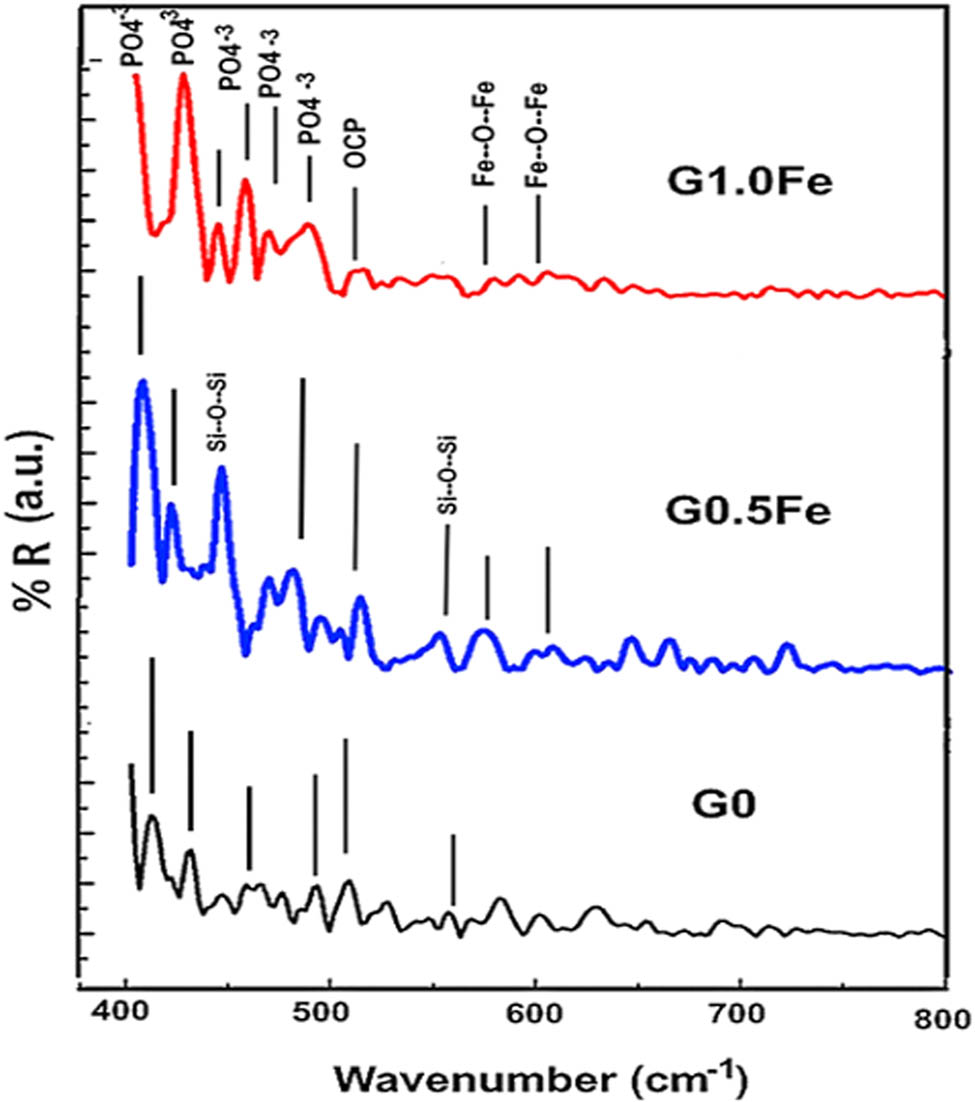

3.2.1 FT-IR analysis following SBF immersion

Using in vitro tests, the synthesized material’s bioactivity was assessed. By immersion in a simulated bodily fluid (SBF), the dynamics of hydroxyapatite (HA) formation, which aids in the creation of strong connections with soft tissues and bones, were assessed using FT-IR and SEM/EDX [23].

In the current study, we investigated the effects of trivalent iron (Fe3+) on the physicochemical and in vitro biological characteristics of wollastonite. By evaluating the formation of hydroxyapatite (HA) cover on the surface using an in vitro bioactivity test, the ability of the produced materials to form bone was investigated [24,25]. The ceramic discs, which were sintered at 1,200°C for 2 h, were immersed in a simulated bodily fluid (SBF) at 37°C for 2 weeks while being kept in a static environment. SBF was set using Kokubo’s standard approach [26], which made it easy for the cells to become viable. Prior to soaking in SBF, Hench proposed a series of five processes to explain the initiation, development, and precipitation of the bone-like apatite phases on top of silicate glass [27].

The exchange of ions from the glass fluid occurs through the exchange of monovalent (Na+) and bivalent (Ca2+) cations from the glass with the SBF protons (H+). This results in the formation of Si–OH bonds (silanol bonds) on the glass surface.

Increasing the pH with respect to alkalinity will damage the Si–O–Si bonds via OH– and produce dissolvable silica Si(OH)4 [28].

Precipitating and decarboxylation Si–OH by the formation of silica gel. The resulting gel can interact with ions from the SBF, making it a key reactor for the formation of apatite.

For 2 weeks, G0, G0.5Fe, and G1.0 Fe discs were submerged in SBF. FT-IR reflection analysis was used to test the layer on the surfaces of the submerged disks, and the obtained spectra are displayed in Figure 6. The presence of well-designed groups was shown to be associated with carbonated apatite [11]. The IR bands observed at 683 and 650 cm−1 were attributed to the symmetric stretching vibration of Si–O–Si. According to Oskoui and Rezvani, the uniformity of the chemical bond determines the width of the band, and each imperfection weakens the bond by creating strain, which changes the bond’s strength and shows up as minute changes in the bond positions. The band linked to the asymmetric stretching of Si–O–Si shifts to lower wavenumbers as the iron oxide content of the sample increases [9].

FTIR reflection of G0, G0.5Fe, and G1.0Fe glasses sintered at 1,200°C.

At 904 and 941 cm−1, the bands associated with the Si–O–NBO non-bridging silicon–oxygen bond were found. The Si–O–Si bending vibrational mode is associated with the bands at 462 and 563 cm−1. The bending vibration of the

3.2.2 SEM/EDX analysis post-immersion in SBF

Figure 7 displays the SEM micrographs of the sintered glasses at 1,200°C/2 h and following a month-long soaking in SBF. At low magnification, the base sample displays irregularly collected small crystals, whereas at high magnification, it displays clusters of fine nanoparticles with scattered strings of sub-nano size in between [35,36]. At low magnification, G0.5Fe has a similar texture; however, at high magnification, several collected clusters with strings of sub-nano size in between were visible. Figure 7 shows the high-magnification many-string crystals in the sub-nanoscale and linked irregular shape grains in the microscale for iron ratio G1.0Fe. The phosphate-containing phase was formed, according to the EDX microanalysis, and the Ca/P ratio ranged from 3.06 (G1.0Fe) to 2.06 (G0.5Fe), while that of the base sample was 2.25 (Figure 7). For samples with a Ca/P ratio of 2.0:3.0, Liu et al. found that the CaO phase starts to resemble the major phase, the HA phase [37]. In the end, in vitro testing typically precedes in vivo testing, and both tests give researchers the information they require to approve a testing compound’s success for its future purpose and danger [38].

SEM images and EDX analysis of G0, G0.5Fe, and G1.0Fe glasses sintered at 1200°C and soaked in SBF for a month.

4 Conclusion

Nominal wollastonite glass was used as the basis for the preparation of sintered glass ceramics with and without 0.5 and 1.0% Fe2O3. Combeite crystallization was shown as a significant phase in the XRD patterns of samples sintered at 1,100 and 1,200°C, together with pseudo-wollastonite and wollastonite. Samples sintered at 1,200°C had irregular grains with submicron-sized particles in their microstructure. Although the zeta potential recorded negative values, the zeta potential analyzer showed that the particle size distribution varied between approximately 1 μm and 190 nm. Due to the Fe2O3 composition, the sintered samples responded magnetically in a variety of ways, including diamagnetically and paramagnetically. The mineralization of

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (grant no. G: 546-247-1442). The authors, therefore, acknowledge DSR for technical and financial support.

-

Funding information: The funding support for the research of this study was granted by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (grant no. G: 546-247-1442).

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Eniu, D., C. Gruian, E. Vanea, L. Patcas, and V. Simon. FTIR and EPR spectroscopic investigation of calcium-silicate glasses with iron and dysprosium. Journal of Molecular Structure, Vol. 1084, 2015, pp. 23–27.10.1016/j.molstruc.2014.12.020Search in Google Scholar

[2] Tatli, Z., O. Bretcanu, F. Çalıs¸kan, and K. Dalgarno. Fabrication of porous apatite-wollastonite glass ceramics using a two steps sintering process. Materials Today Communications, Vol. 30, 2022, id. 103216.10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.103216Search in Google Scholar

[3] Mahdy, M. A., S. H. Kenawy, E. M. A. Hamzawy, G. T. El-Bassyouni, and I. K. El Zawawi. Influence of SiC on structural, optical and magnetic properties of wollastonite/Fe2O3 nanocomposites. Ceramics International, Vol. 47, No. 9, 2021, pp. 12047–12055.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.01.048Search in Google Scholar

[4] Nayak, M. T., J. A. E. Desa, and P. D. Babu. Magnetic and spectroscopic studies of an iron lithium calcium silicate glass and ceramic. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, Vol. 484, 2018, pp. 1–7.10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2017.12.050Search in Google Scholar

[5] Holland, D., A. Mekki, I. A. Gee, C. F. McConville, J. A. Johnson, C. E. Johnson, et al. The structure of sodium iron silicate glass – a multi-technique approach. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, Vol. 253, No. 1–3, 1999, pp. 192–202.10.1016/S0022-3093(99)00353-1Search in Google Scholar

[6] Taha, S. K., M. A. Abdel Hamid, E. M. A. Hamzawy, S. H. Kenawy, G. T. El-Bassyouni, E. A. Hassan, et al. Osteogenic potential of calcium silicate-doped iron oxide nanoparticles versus calcium silicate for reconstruction of critical-sized mandibular defects: An experimental study in dog model. Saudi Dental Journal, Vol. 34, 2022, pp. 485–493.10.1016/j.sdentj.2022.06.008Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[7] Sahadevan, J., R. Sojiya, N. Padmanathan, K. Kulathuraan, M. G. Shalini, P. Sivaprakash, et al. Magnetic property of Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 nanoparticle prepared by solvothermal process. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 58, 2022, pp. 895–897.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.11.420Search in Google Scholar

[8] Neuberger, T., B. Schöpf, H. Hofmann, M. Hofmann, and B. Rechenberg. Superparamagnetic nanoparticles for biomedical applications: Possibilities and limitations of a new drug delivery system. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, Vol. 293, No. 1, 2005, pp. 483–496.10.1016/j.jmmm.2005.01.064Search in Google Scholar

[9] Oskoui, P. R. and M. Rezvani. Structure and magnetic properties of SiO2-FeO-CaO-Na2O bioactive glass-ceramic system for magnetic fluid hyperthermia application. Heliyon, Vol. 9, 2023, id. e18519.Search in Google Scholar

[10] Srivastava, A. K., R. Pyare, and S. P. Singh. In vitro bioactivity and physical - mechanical properties of Fe2O3 substituted 45S5 bioactive glasses and glass – ceramics. Journal of Biomimetics Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2012, pp. 249–258.10.1166/jbt.2012.1043Search in Google Scholar

[11] Mahdy, M. A., S. H. Kenawy, I. K. El Zawawi, E. M. A. Hamzawy, and G. T. El-Bassyouni. Optical and magnetic properties of wollastonite and its nanocomposite crystalline structure with hematite. Ceramics International, Vol. 46, No. 5, 2020, pp. 6581–6593.10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.11.144Search in Google Scholar

[12] Mabrouk, M., S. K. Taha, M. A. Abdel Hamid, S. H. Kenawy, E. A. Hassan, and G. T. El-Bassyouni. Radiological evaluations of low cost wollastonite nano-ceramics graft doped with iron oxide in the treatment of induced defects in canine mandible. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research B Applied Biomaterials, Vol. 109, 2021, pp. 1029–1044.10.1002/jbm.b.34767Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[13] Danewalia, S. S. and K. Singh. Bioactive glasses and glass–ceramics for hyperthermia treatment of cancer: state-of-art, challenges, and future perspectives. Materials Today Bio, Vol. 10, 2021, id. 100100.10.1016/j.mtbio.2021.100100Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[14] Kokubo, T. and H. Takadama. How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity? Biomaterials, Vol. 27, No. 15, 2006, pp. 2907–2915.10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.017Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[15] Baino, F. and S. Yamaguchi. The use of simulated body fluid (SBF) for assessing materials bioactivity in the context of tissue engineering: Review and challenges. Biomimetic (Basel), Vol. 5, No. 4, 2020, id. 57.10.3390/biomimetics5040057Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[16] Kokubo, T. and S. Yamaguchi. Simulated body fluid and the novel bioactive materials derived from it. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research A, Vol. 107, No. 5, 2019, pp. 968–977.10.1002/jbm.a.36620Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[17] Alangari, A., M. S. Alqahtani, A. Mateen, M. AbulKalam, A. Alshememry, R. Ali, et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization, and assessment of antimicrobial and anticancer activity. Adsorption Science & Technology, Vol. 2022, 2022, id. 1562051.10.1155/2022/1562051Search in Google Scholar

[18] Şavran, C., T. Türk, G. Irgasheva, and M. O. Kangal. Enrichment of wollastonite with high calcite content. Physicochemical Problem of Mineral Processing, Vol. 58, No. 5, 2022, id. 153058.10.37190/ppmp/153058Search in Google Scholar

[19] Eldera, S. S., N. Alsenany, S. Aldawsari, G. T. El-Bassyouni, and E. M. A. Hamzawy. Characterization, biocompatibility and in vivo of nominal MnO2-containing wollastonite glass-ceramic. Nanotechnology Reviews, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2022, pp. 2800–2813.10.1515/ntrev-2022-0477Search in Google Scholar

[20] Akamatsu, H., S. Oku, K. Fujita, S. Murai, and K. Tanaka. Magnetic properties of mixed valence iron phosphate glasses. Physical Review B, Vol. 80, 2009, id. 134408.10.1103/PhysRevB.80.134408Search in Google Scholar

[21] Shakdofa, M. M. E., E. A. Mahdy, and H. A. Abo-Mosallam. Thermo-magnetic properties of Fe2O3-doped lithium zinc silicate glass-ceramics for magnetic applications. Ceramics International, Vol. 47, 2021, pp. 25467–25474.10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.05.269Search in Google Scholar

[22] Mahdy, M. A., E. M. A. Hamzawy, G. T. El-Bassyouni, I. K. El Zawawi, and H. H. A. Sherif. Influence of manganese ions in calcium silicate glass–ceramics on optical, mechanical, and magnetic properties. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics (JMSE), Vol. 34, No. 4, 2023, id. 295.10.1007/s10854-022-09605-8Search in Google Scholar

[23] Myat-Htun, M., A. F. Mohd Noor, F. Kawashita, and Y. M. Baba Ismail. Tailoring mechanical and in vitro biological properties of calcium‒silicate based bioceramic through iron doping in developing future material. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, Vol. 128, 2022, id. 105122.10.1016/j.jmbbm.2022.105122Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[24] Kusyak, A., V. Poniatovskyi, O. Oranska, D. M. Behunova, I. Melnyk, V. Dubok, et al. Nanostructured sol-gel bioactive glass 60S: In vitro study of bioactivity and antibacterial properties in combination with vancomycin. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids: X, Vol. 20, 2023, id. 100200.10.1016/j.nocx.2023.100200Search in Google Scholar

[25] Dridi, A., K. Z. Riahi, and S. Somrani. Mechanism of apatite formation on a poorly crystallized calcium phosphate in a simulated body fluid (SBF) at 37°C. Journal of Physics and Chemistry Solids, Vol. 156, 2021, id. 110122.10.1016/j.jpcs.2021.110122Search in Google Scholar

[26] Kokubo, T., H. Kushitani, S. Sakka, T. Kitsugi, and T. Yamamum. Solutions able to reproduce in vivo surface-structure changes in bioactive. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research, Vol. 24, No. 6, 1990, pp. 721–734.10.1002/jbm.820240607Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[27] Hench, L. L. The story of bioglass. Journal of Materials Science 3 Materials Medical, Vol. 17, No. 11, 2006, pp. 967–978.10.1007/s10856-006-0432-zSearch in Google Scholar PubMed

[28] Lunevich, L. Chapter: Aqueous silica and silica polymerization, Published: March 5th (2019). IntechOpen; 2019.10.5772/intechopen.84824Search in Google Scholar

[29] Dorozhkin, S. V. Synthetic amorphous calcium phosphates (ACPs): Preparation, structure, properties, and biomedical applications. Biomaterials Science, Vol. 9, 2021, pp. 7748–7798.10.1039/D1BM01239HSearch in Google Scholar

[30] El-Sayed, M. M. H., A. A. Mostafa, A. M. Gaafar, W. El Hotaby, and E. M. A. Hamzawy. In vitro kinetic investigations on the bioactivity and cytocompatibility of bioactive glasses prepared via melting and sol–gel techniques for bone regeneration applications. Biomedical Materials, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2017, id. 015029.10.1088/1748-605X/aa5a30Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[31] Mabrouk, M., S. A. ElShebiney, S. H. Kenawy, G. T. El-Bassyouni, and E. M. A. Hamzawy. Novel, cost-effective, cu-doped calcium silicate nanoparticles for bone fracture intervention: inherent bioactivity and in vivo performance. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B, Vol. 107B, 2019, pp. 388–399.10.1002/jbm.b.34130Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[32] El-Kheshen, A. A., G. T. El-Bassyouni, A. H. Abdel-kader, and A. O. El-Maghraby. Effect of composition on bioactivity and magnetic properties of glass/ceramic composites for hyperthermia. Interceram, Vol. 60, No. 6, 2011, pp. 379–382.Search in Google Scholar

[33] Valverde, T. M., V. M. R. dos Santos, P. I. M. Viana, G. M. J. Costa, A. M. de Goes, L. R. D. Sousa, et al. Novel Fe3O4 nanoparticles with bioactive glass–naproxen coating: Synthesis, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of bioactivity. Int J Mol Sci, Vol. 25, 2024, id. 4270.10.3390/ijms25084270Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[34] Chukanov, N. V. IR Spectra of minerals and reference samples data, infrared spectra of mineral species, Springer Geochemistry/Mineralogy, Springer, Dordrecht, 2014.10.1007/978-94-007-7128-4Search in Google Scholar

[35] Zaki, D. Y. and E. M. A. Hamzawy. In vitro bioactivity of binary nepheline-fluorapatite glass/polymethyl-methacrylate composite. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, Vol. 2018, 2018, id. 8379495.10.1155/2018/8379495Search in Google Scholar

[36] El-Batal, F. H. and G. T. El-Bassyouni. Bioactivity of hench bioglass and corresponding glass-ceramic and the effect of transition metal oxides. Silicon, Vol. 3, No. 4, 2011, pp. 185–197.10.1007/s12633-011-9095-6Search in Google Scholar

[37] Liu, H., H. Yazici, C. Ergun, T. J. Webster, and H. Bermek. An in vitro evaluation of Ca/P ratio of cytocompatibility of nano-to-micron particulate calcium phosphates for bone regeneration. Acta Biomaterialia, Vol. 4, 2008, pp. 1472–1479.10.1016/j.actbio.2008.02.025Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[38] Hamzawy, E. M. A., A. M. El-Kady, M. I. El Gohary, A. A. El Saied, and S. H. Zayed. In vivo bioactivity evaluation for an inexpensive biocompatible composite based on wollastonite ceramic/soda-lime-silica glass. Biomedical Physics & Engineering Express, Vol. 3, No. 4, 2017, id. 045018.10.1088/2057-1976/aa7c79Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods