Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

Abstract

This study presents a significant advancement in the development of sustainable construction materials by utilizing treated plastic waste and foundry sand to produce lightweight foam concretes and investigates the performance of lightweight foamed concrete premixed with a new composite of plastic waste pre-treated with polyester polymer and covered with waste foundry sand as a sand replacement material with different dosages of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 by weight of sand. The mechanical properties, including compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths, were evaluated at ages of 7, 14, 28, 56, and 180, in addition to their fresh properties. Durability aspects such as porosity, shrinkage, and water absorption ensure long-term resilience. The thermal properties, including conductivity and diffusivity, were examined to enhance the energy efficiency, and microstructural analyses were conducted. The results showed a significant increase in initial and final setting times by 6.3 and 30%, respectively, with a 6.4% improvement in workability with 20% sand replacement. Compared to the reference mix, the dry density decreased by 9.4%, and the compressive increased by 76.1, 70.4, 84.2, 84.4, and 83% at 7, 14, 28, 56, and 180 days, respectively. Moreover, splitting strength increased by 99%, and flexural strength increased by 84.7, 91.3, 115, 111.9, and 110.9% compared to the reference mix at 7, 14, 28, 56, and 180 days, respectively. The dry shrinkage decreased by 56.48% after 28 days for all replacement ratios. Notably, replacing sand with 50% waste plastic reduced thermal conductivity to 0.28 W·m−1·K−1 and decreased specific heat capacity by 18.7%. Scanning electron microscopic analysis revealed a dense microstructure with smaller voids. These findings demonstrate that incorporating treated plastic waste and foundry sand as sand replacements in lightweight foamed concrete significantly enhances the mechanical strength, durability, and thermal efficiency, making it a promising material for sustainable and energy-efficient construction in the future.

1 Introduction

Lightweight concrete is a more general term that covers lightweight aggregate concrete, autoclaved aerated concrete, and foamed concrete [1]. Some advantages of these concrete types are that they are lighter, better at blocking heat and sound, and easier to operate. Lightweight concrete has many applications, such as beams, precast concrete blocks, parking structures, bridge decks, piers, roof insulation, and non-load-bearing walls; however, these applications require easy maintenance, durability, and safety [2,3]. Therefore, this is a challenge. This is in addition to the common characteristics of lightweight concrete, such as thermal conductivity, low density, good durability, acceptable compressive strength, easy handling, and transportation [1]. Lightweight concrete is rarely used in columns and foundations. Foamed concrete is a special type of lightweight concrete, also called aerated concrete, which is prepared by mixing a foaming agent with cement mortar to form many stable air bubbles. This makes the material much lighter than regular concrete, which usually has a density of approximately 400–1,600 kg·m−3. The production of eco-friendly foam concrete was studied using waste glass as the primary precursor and incineration bottom ash as the foaming agent via a new sintering technique [2] using lightweight aggregates for high-strength lightweight foam concrete. For foamed concrete, recycled waste concrete was utilized as a fine aggregate at ratios of 25, 50, 75, and 100% to enhance the thermal properties and achieve environmental effects [3]. Recently, some applications require lightweight concrete; therefore, Md Azree Othuman Mydin et al. [4] investigated the improvement of foamed concrete properties using nano-silica with dosages of 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5%, in addition to enhancing and modifying properties in terms of fresh and hardened properties and recommended 3% as the optimum percentage to develop foamed concrete properties. Polyester polymer concrete, which requires rapid curing and repair, is widely used in the concrete industry. It is subjected to impact in addition to its unique strength resistance under triaxial compression, achieving an increment in the stress ratio ranging from 1.83 to 2.95 in the uniaxial stress, and the strain decreases gradually up to four times the uniaxial strain with increasing stress [5].

Improving lifestyles and increasing population significantly increase waste and are environmental challenges owing to their voluminous generation and non-biodegradable nature [6,7,8]. The construction process is of prime importance in obtaining eco-friendly materials with good mechanical and physical properties to develop new infrastructure and achieve cost-effectiveness. Plastics are waste that has gained attention because of their low thermal and electrical conductivities and huge production worldwide. The world produces more than 300 million tons of plastic annually but at a low percentage, which can be burned or cast off by approximately 20% and increase globally on a large scale [9,10]. To achieve this goal, the demand for alternative renewable natural sources has increased to achieve environmental benefits by reducing the carbon footprint of the concrete industry and using new strategies to obtain alternatives to existing materials for energy-efficient buildings [11,12,13]. Waste foundry sand is a promising by-product material of ferrous and non-ferrous metals that can be utilized as an alternative source for natural sand based on previous studies for fully and partially replacing sand with foundry sand and is recommended to be suitable for structural concrete owing to its good durability performance [14,15,16].

Plastic waste is recycled and reused as an alternative in the concrete industry based on its characteristics of lightweight, durability, and insulation, and wide applications involve making sustainable fibers and reducing the costs and environmental pollution caused by trash plastic. Saikia et al. [17] showed that incorporating polyethylene terephthalate (PET) aggregates enhanced concrete workability. Guo et al. [18] investigated the effect of using waste plastic fibers and recycled concrete to improve self-compacting concrete properties and reported that using plastic fiber enhanced mechanical properties. Tayeh et al. [19] investigated the effect of replacing sand with 0, 10, 20, 30, and 40% of PET and polyethylene (PE) on the properties of fresh and hardened concrete, including density, workability, compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength, and durability. The study showed that workability significantly increased, with a 188% rise in slump at a 40% replacement ratio, while the fresh unit weight tested based on BS, 1881-124, 2015 [20] and showed density reduction by 13.6% for PE and 6.4% for PET. Similarly, the dry unit weight dropped by 7.3 and 4.28% for PE and PET, respectively, which adversely affected compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths. Compressive strength declined by 15.4–21.4% for PE and 33.65–52.46% for PET, while splitting tensile and flexural strength reductions ranged from 9.12–42.41% and 5.61–24.96% for PE and PET, respectively, accompanied by a decrease in ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV). However, energy absorption was significantly improved in plastic concrete compared to normal concrete, reaching 1,600% for PE and 866% for PET, along with enhanced impact resistance.

Despite the advancements in sustainable construction materials, integrating recycled waste plastics into foam concrete remains limited and needs to be explored. This study investigates the effect of using a new approach in which recycled waste plastic is pretreated with polyester polymer and coated with fine foundry sand to achieve homogeneous consistency by increasing the density and avoiding the floating of lightweight aggregates in foamed concrete. This new composite material is intended to investigate the mechanical properties of foamed concrete, including compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, flexural strength, thermal properties of specific heat, thermal diffusive and heat transfer, durability, and microstructural properties of lightweight foamed concrete. The performance was compared with that of the reference mix. In addition, the environmental impact of CO2 emissions was evaluated.

2 Experimental program

2.1 Raw materials

Lightweight foamed concrete production requires cement, fine sand, clean water, and foaming agents, all of which have specific properties. The cement was classified as CEM 1 52.5 N and complied with the specifications specified in MS EN 197-1:2014. Local resources were used to obtain fine sand, which was passed through a sieve with a mesh size of 1.18 mm. The specific density of fine sand is 2.49, and the fineness modulus was 2.19. A locally manufactured protein-based foaming agent, Noraite PA-1, which is a protein-type foaming agent, was selected for this study because of its stronger binding structural attribute bubbles and stability when compared with synthetic protean-based foaming agents. As for its formulation, the exact composition of Noraite PA-1 is confidential, but it is known that these types of protein–based foaming agents are made from hydrolyzed natural proteins containing considerable amounts of the amino acids such as glutamic acid, alanine, leucine, and glycine, which enhance surface activity and foam stability.

The concentration of the foaming agent was reduced by diluting it with water at a ratio of one part of the foaming agent to 33 parts. Water is tap water free of particles or substances that may affect its cleanliness and purity. This meets the standards set by BS-3148.

2.2 Polyester-coating procedure of plastic waste aggregates

The plastic waste utilized in the present study, which substituted sand partially, was procured from Skyline Polymers, a company specializing in the manufacture of thermoplastics in Egypt. The material used was postconsumer low-density branched ethylene (LDPE) plastic bags and film products, which were later subjected to recycling. The LDPE was shredded, washed, and extruded to produce homogeneous LDPE flakes, which have a bulk density ranging from 910 to 930 kg·m−3. These flakes are suitable for lightweight concrete. As per the supplier, this material has a melt flow index of 6–8 g·10 min−1 at 190°C (2.16 kg) and a viscosity average molecular weight in the range of 80,000–120,000 g·mole−1.

The polyester resin used in this study was supplied by Endmoun for Chemical Industries, an Egyptian manufacturer of unsaturated polyester industrial-grade formulated resin. The resin showed a density of 1.1 g·cm−3 and remarkable mechanical performance, with flexural strength of 138 MPa and elongation at break (tensile = 2.50%, flexural = 5.94%) as per international organization for standardization (ISO) 0178. Its water absorption was low at 0.16% (ISO 0062), which indicates good dimensional stability.

Plastic waste with a density of 820 kg·m−3 was determined and submerged in polyester of straw with a specific gravity of 1.11 g·ml−1 while mixing until fully coated by adding cobalt naphthenate as additive with 0.1% from resin weight to accelerate hardening. Fine foundry sand 600 µm in size was added and mixed. A new composite was set up for drying under normal conditions for 48 h, and the final density was calculated to be 1,010 kg·m−3, as shown in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows the new composition preparation steps.

Preparation of new composite of plastic waste pre-treated with polyester polymer and covered with waste foundry sand.

Preparation steps for new composite.

2.3 Lightweight foamed concrete mix design

Lightweight foamed concrete was created using a cement-to-sand ratio of 1:1.5 by weight and a water-to-cement ratio of 0.45. This resulted in the production of medium-density foam concrete with a density of 1,280 kg·m−3, which was then analyzed. Plastic waste that underwent polymer pre-treatment and was coated with waste foundry sand was used as a substitute for sand. The proportions are as follows: 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50%. The mix proportions of lightweight foamed concrete are given in Table 1.

Lightweight foamed concrete mix proportions

| FC coding | Plastic waste (%) | Cement (kg·m−3) | Sand (kg·m−3) | Plastic waste (kg·m−3) | Foam (kg·m−3) | Water (kg·m−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LWP-P0 | 0 | 480 | 720 | 0 | 22 | 216 |

| LWP-P10 | 10 | 480 | 648 | 72 | 22 | 216 |

| LWP-P20 | 20 | 480 | 580 | 140 | 22 | 216 |

| LWP-P30 | 30 | 480 | 504 | 216 | 22 | 216 |

| LWP-P40 | 40 | 480 | 432 | 288 | 22 | 216 |

| LWP-P50 | 50 | 480 | 360 | 360 | 22 | 216 |

2.3.1 Mixing and casting

The mixing process of lightweight foam concrete was divided into two distinct steps. The initial step involved creating a stable foam by introducing a foaming agent into water at a ratio of 1:33. A compressor was used to generate the foam. Simultaneously, the cement, sand, water, and waste foundry sand powder were combined in a dry state using a planetary mixer. The stabilized foam was then added to the mixture to form fresh concrete following procedures reported in the literature [21,22,23,24,25,26]. The resulting mixture was shaped and dried until the specified test date, as shown in Figure 3.

Process of producing lightweight foamed concrete.

2.4 Experimental setup

Evaluating the properties of lightweight foamed concrete includes a study of several properties. Workability, setting time, and density were measured in the fresh state to evaluate the properties. The compressive strength, indirect tensile strength, flexural strength, and UPV were examined in terms of mechanical properties. In addition, durability properties such as sorptivity, apparent porosity, absorption, and dry shrinkage were determined. Moreover, the thermal properties, including thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity, and specific heat, are essential for lightweight foamed concrete. A microscopic examination used a scanning electron microscope (SEM) to analyze the structure. Figure 4 explains the performed tests.

Experimental program flow chart.

2.4.1 Workability and setting time

The common slump test is reported to be unsuitable for low-density concrete [27], and foam concrete workability evaluates viscosity; therefore, the slump test was performed in accordance with GB/T 8077-2016; a truncated cone (an upper diameter of 36 mm, a lower diameter of 60 mm, and a height of 60 mm) was used to test the fluidity of fresh cement pastes [28] and to evaluate the workability of all lightweight foamed concrete mixtures. To confirm the initial and final setting times, the viscosity of the paste must be tested by measuring the depth to which a Vicat piston with a diameter of 10 mm and a length of 50 mm can reach the paste. This measurement should be performed at a depth of 33–35 mm from the top of the mold, following the guidelines in BS EN 196-3 2005 [29]. The value of the fresh density was derived based on BS 12350-6 [30].

2.4.2 Sorptivity

The sorptivity of all mixtures was examined using cylindrical samples with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm, as specified in American society for testing and materials (ASTM) C 642 (2013). The surface of each sample was tightly sealed with silica gel, and the top surface was protected with a plastic cap. The samples were placed in a pan with the bottom submerged by 1–3 mm. The weight of each sample was recorded at specified time intervals after the initial exposure to water. Each group underwent six samples.

2.4.3 Mechanical properties

The compressive, splitting tensile, and flexural strengths were examined at 7, 14, 28, 56, and 180 days. A GOTECH-7001-M5 machine was used to perform compressive strength analysis, capable of bearing a load of 3000 kN and a loading speed of 0.5 N·mm−2·s−1. Compressive strength testing was performed on foaming concrete (FC) cubic specimens measuring 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm, according to the BS12390-3 (2002) guidelines [31]. The average results of the three samples were recorded. Samples with dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm × 500 mm were subjected to flexural strength testing according to BS12390-5 (2019) [32]. A GoTech GT-7001-C10 device is also used for mechanical testing. In addition, a GT-7001-BS300 universal testing machine was used to measure the tensile strength of cylindrical specimens with dimensions of 100 mm × 200 mm, according to the ASTM International C496 standard [33] and BS1239-6 [34]. UPV testing was performed to evaluate the quality of the concrete in accordance with the standards mentioned in BS12504-4 (2004) [35] using a prism measuring 100 mm × 100 mm × 500 mm, and the results were determined by averaging data from three samples. Dry shrinkage was evaluated following the guidelines outlined in ASTM C878, using prisms with 75 mm × 75 mm × 290 mm dimensions. The data obtained from the length measurements were used to calculate the drying shrinkage strain. This is expressed as a percentage of the original length of the specimen. Drying shrinkage was reported as the change in length per unit length (mm·m−1 or µm·m−1) during the drying period.

2.4.4 Thermal properties test

According to ASTM Protocol C 177, hot-shielded plate testing was performed to measure the thermal conductivity, diffusivity, and specific heat capacity of concrete. It is widely recognized that hot plate testing is the primary method for measuring the heat transfer capabilities of uniform insulating materials. A hot-disk thermal constant analyzer (TPS 2500) was used to measure the thermal conductivity of lightweight foam concrete. The experiments were conducted at ambient temperature (23 ± 2 °C) without an external heating rate since the TPS method works under isothermal conditions during testing. Each sample was in the shape of a cylinder with 50 mm in diameter and 20 mm in thickness, and for ensuring reproducibility and minimizing experimental uncertainty, the average thermal conductivity was calculated from three replicate measurements.

2.4.5 Microstructural analysis

SEM was used to observe the microstructure of FC in the presence of LWP. QUANTA FEG 650, a fully high-resolution analytical instrument, was used to acquire data. It is equipped with an Oxford Instruments X-Max 150 mm energy-dispersive X-ray detector, which automatically acquires high-resolution images over wide areas. This investigation included FC samples of dimensions 10 mm × 10 mm × 10 mm. Specifically, the samples were placed inside a vacuum chamber and coated with pure gold before the analysis to facilitate unhindered electron passage. If the coating is not performed properly, the image will be destroyed, and a white appearance will appear, resulting in blurry images. The inspections were performed at a depth of 10 mm from the surface.

The porosity of the lightweight foamed concrete mixes was the sum of the voids within the paste, and the entrained air bubbles were measured using vacuum saturation equipment. Cylindrical samples with 75 × 100 mm dimensions were cast and tested after 7, 14, 28, and 90 days of curing, following the methodology outlined by Cabrera and Lynsdale [36]. The porosity was determined by employing Eq. (1):

where P is the vacuum saturation porosity (%), W sat is the weight of the air-saturated sample, and W dry is the weight of the oven-dried sample.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Workability

Figure 5 shows the relationship between the flow diameters and different replacement ratios of plastic waste in lightweight foamed concrete. Using polymer-treated plastic waste and fine-waste foundry sand as partial substitutes for sand impacts the ease of working with foam concrete. A significant increase in workability was observed when the replacement level was increased from 10 to 50%. The increase in workability was mainly due to the properties of a low percentage of foundry sand with a decreasing surface area, absorption ratio, and plastic debris compared with full natural sand, which has rounded and smooth grains [6]. Plastic waste particles exhibit uneven shapes and rough surfaces. Increased internal friction impedes the smooth movement of the concrete mixture, resulting in increased hardness and difficulty in handling [37]. When lower replacement levels were used, such as 10 or 20%, there was a significant increase in the slump flow from 25.9 to 26.4 cm in lightweight foamed concrete. This can be easily controlled by making minor mix design adjustments or using plasticizers. However, when the substitution level exceeded 20%, difficulties in achieving operability became more evident because more foundry sand existed compared to fewer replacement ratios, with a recorded decrease in the slump flow from 26.40 to 25.3 cm. The mixture requires greater effort and is progressively more challenging to handle, cast, and finish [38]. The slump increased to a replacement ratio of 20%, but a slight decrease in the flow diameter was obtained beyond this value at a 50% replacement ratio. This can be attributed to the increasing surface area of each particle in the new composite, as part of the composite is smooth, and some are artificial because the coating can consume water when measuring the slump, which is still less than that of natural sand [38]. Consequently, 20% achieved the best balance between the new composite and the natural sand. In addition, at a 50% replacement of sand with a new composition, a high ratio may disrupt the balance of the mix, leading to a less cohesive matrix and less stability, which stops the improvement of workability [6]. The surface characteristics of the new composite may contribute to obtaining less cohesive mixes in the presence of foams, thereby reducing the relative workability improvement [39]. The optimal packing effect of the combination of sand and plastic creates workable and denser lightweight foam concrete because plastic waste may fill the voids created between sand particles, leading to easier and smoother flow. In general, although the plastic waste replacement ratio exceeded 20% led to a reduction in workability, all blends that contained plastic waste still had higher slump values when compared to the reference blend, suggesting enhanced flowability.

Workability of lightweight foamed concrete.

3.2 Setting time

Figure 6 shows the effect of plastic waste pre-treated with polymer and covered with foundry sand on the initial and final setting of lightweight foamed concrete when the replacement levels changed from 10 to 50%, with a 10% increase in the replacement ratio. The initial setting time increased with increasing replacement ratio by 22.52, 27.74, 39.88, 53.17, and 63% compared to the reference mix, which may be a result of the altered water absorption patterns resulting from the presence of the treated plastic waste, which has a lower absorption ratio. The final setting time also increased with lower values than the initial setting time of 8.98–31.16% when waste plastic was utilized from 10 to 50%. The presence of polymer-coated plastic particles and small amounts of waste foundry sand may hinder the cement hydration process by increasing the water content at a lower absorption ratio for each replacement ratio, resulting in a slower rate of concrete hardening [37]. Prolonged preparation periods can cause delays in proceeding with construction activities, resulting in longer project timeframes and higher costs because when the substitution level exceeds, the delay in timing becomes more apparent [23,40]. This can present difficulties, especially in fast-moving construction settings, where rapid hardening and early strength development are vital [4]. The increase in setting time with increasing replacement ratio can be attributed to the consistency reduction with an increase in the volume of foam in the mix, which may be attributed to (i) adhesion between the bubbles and solid particles in the mix, which increases the stiffness of the mix, and (ii) reduced self-weight and greater cohesion resulting from the higher air content [41]. Increasing the setting time may be attributed to the fact that when coated plastic is used, it can inhibit the movement between water and cement, thereby decreasing the rate of hydration, and the presence of coated plastic acts as a barrier to water penetration, which increases the setting time.

Initial and final setting of lightweight foamed concrete.

3.3 Density

Figure 7 shows the dry densities of all mixes. The figure shows a slight decrease in dry density from 1,320 kg·m−3 in the control mix with sand content as fine aggregate to 1,206 at a 50% replacement ratio of sand with waste plastic, which may be attributed to the low density of waste plastic compared to natural sand [42,43]. In addition, the foaming agent reduced the density, and the remaining water improved the void distribution during mixing. The lower densities of 2.8, 3.7, 4.1, 7.5, and 8.6% were achieved at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50%, respectively. This decrease in density could make lightweight foam concrete ideal for decreasing the total load for foundation applications [44]. These observations were also confirmed by Gencel et al. [45], who investigated two different dosages of foaming agents. They reported a low density at a higher dosage with a recorded dry density ranging between 890 and 1,504 kg·m−3 at 50 kg·m−3 foaming content of 50 kg·m−3 and 594–1078 kg·m−3 at 100 kg·m−3 foaming content of 100 kg·m−3. In conclusion, because the obtained density of the new composite is 1,010 kg·m−3, which is lower than that of natural sand with a density of 1,600 kg·m−3, the new composite has a lower absorption ratio; therefore, more voids may be created in the presence of foam, and the density also decreases. Many factors affect this, such as the air void distribution of plastic waste, which may alter the distribution compared to natural sand, polymer coating, and packing, depending on the size, shape, and interaction between particles [12]. This creates complex relationships between materials; therefore, the reduction in density differs from the difference between densities [4,46].

Measured density of foam concrete with varying weight fractions of LWP.

3.4 Compressive strength

Figure 8 shows the compressive strength of lightweight foamed concrete with different dosages ranging from 10 to 50% plastic waste at 7, 14, 28, 56, and 180 days. At 7 days compressive strength, a significant increase in compressive strength is obtained as the increasing ratio increases from 8.59 to 15.14 MPa at a 20% replacement ratio, with a 76.12% increase ratio. At higher dosages, the increasing ratio slightly decreased from 15.14 to 9.4 MPa, achieving a 9.6% increase ratio compared to the reference mix. This improvement can be attributed to the improved adhesion between the plastic particles and the cement matrix [37,47]. The new surface state increases the bond, which also enhances the interfacial transition zone and aggregate distribution owing to the enhanced density of waste plastic after curing and improves the reliability and overall strength; however, the slight reduction is due to the high number of pores, capillary microcracks, and void continuity created in the microstructure of the concrete, thereby reducing the concrete strength [48]. At 14 and 28 days, the compressive strength achieved higher values ranging between 11.8 and18.19 MPa compared to 10.67 MPa for replacing ratios up to 20%. Then, it decreased to 5.6 MPa at 14 days with an increasing ratio ranging between 10.5% at 50% LWP-P50 and 70.4% at LWP-P20 due to strength gaining continuity due to more hydration process. The ideal dosage is recorded at 20%, achieving the balance between components with an 84% increasing ratio with recording 24 MPa. The smooth surface due to sand achieved a higher bond and increased the compressive strength and promising sustainable concrete [18,49]. The strength development increased by 18–84% at 28 and 56 days, and a similar trend of improvement was obtained at 180 days [12], with approximately double the strength at 20% replacement compared with the reference mix with full sand replacement content. The compressive strength results obtained equalled 14–22 MPa which is in agreement with results obtained when 10%–40% palm oil was used as sand replacement materia [12] when 471.2 kg·m−3 of cement was used in mixing and 942.5 kg·m−3. Al-Shwaiter et al. [12] reported an increase in the compressive strength of lightweight foamed concrete up to 180 days with a small rate owing to the continuity of the hydration process. Based on Table 1, all mixes have constant cement content but curing age could significantly enhance concrete composite and decrease voids in addition to good bonding, as the increasing strength up to 120 days is also reported in the study by Khan et al. [26]. In addition, the polymer content is essential for coating plastic waste in a hardened state and not in a liquid state; therefore, we focused on the new composite. In conclusion, the hydration process occurs over an extended period, producing more calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel that develops strength gain. This product is still produced, particularly in lightweight foamed concrete, owing to its high water retention and low density, which enhances internal curing [50]. A lower density leads to fewer internal stresses that can be improved with time, with the gradual filling of pores with hydration products, strength gain, and promotion of prolonged hydration [21]. At 20% sand replacement, the optimum strength was obtained with a combination of low porosity and high bond between particles, and the interfacial bond may still be strong and effective, leading to a higher compressive strength. Therefore, the optimal strength performance observed for the LWP-P20 mix aligns with the effective balance of these factors. Beyond this point, increasing plastic waste may disrupt the overall bond strength or alter the microstructure in ways that do not positively contribute to the compressive strength [18]. Excessive plastic particles can create weak spots or reduce the effectiveness of bonding, which negatively affects strength [18]. The strength performance at 20% plastic waste replacement is a result of achieving a balance between improved porosity and sorptivity and the optimal structural bonding and compaction properties of the mix. While increased plastic waste reduces porosity and sorptivity, it can also affect strength if bonding or compaction is compromised [51].

Compressive strength of lightweight foamed concrete.

3.5 Flexural strength

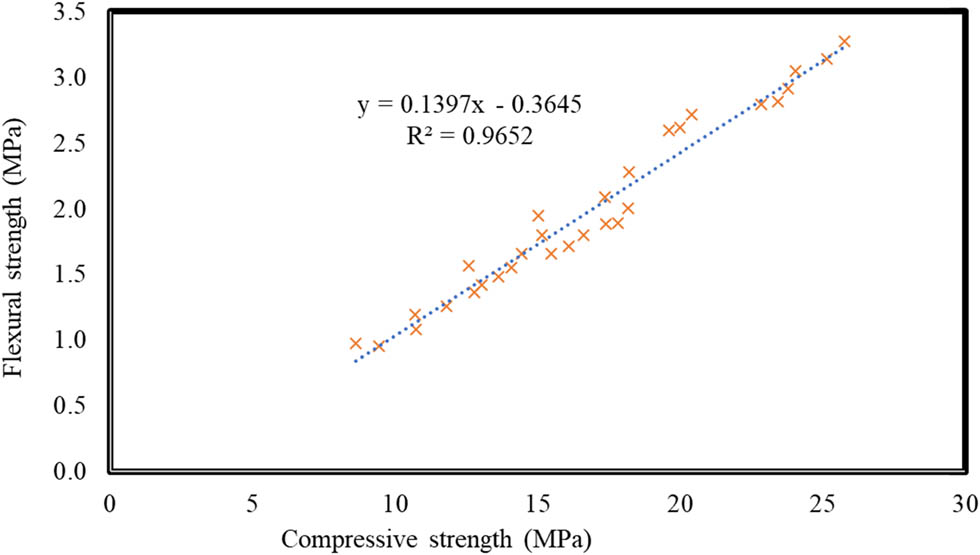

Figure 9 shows the flexural strength results of lightweight foamed concrete with different dosages ranging from 10 to50% of plastic waste treated with polymer and covered with waste foundry sand as a sand replacement alternative tested at curing ages of 7, 14, 28, 56, and 180 days. Comparing the results at all curing ages and various replacement ratios, a replacement level of 20% was recommended as the most appropriate minimum to achieve the highest possible flexural strength. The lightweight foamed concretes with high increasing strength ratios were observed by 84.8, 92.18, 115.08, 112.05, and 111.09% at 7, 14, 28, 56, and 180 days, respectively. Higher ratios resulted in a smaller increase in strength, and the decrease in strength was greater beyond the 20% dosage. The strength improvement at LWP-P50 reached 1.9, 6.5, 16.9, 15.6, and 15.89% at 7, 14, 28, 56, and 180 days, respectively, owing to the high percentage of lighter materials. This decreases the overall density and balance between the concrete components, reducing the material’s structural integrity and ability to withstand the bending forces [18,43]. However, the flexural strength increased for all mixes, which agrees with lightweight foamed concrete applications and can be used for structures. Hence, this can reduce the structural integrity of the material and its ability to withstand bending forces [52]. A strong correlation with an R 2 of 0.96 is observed between the compressive and flexural strengths, as shown in Figure 10.

Flexure strength of lightweight foamed concrete.

Relation between compressive strength and flexure strength.

3.6 Split tensile strength

Figure 11 shows the splitting strength results of lightweight foamed concrete with different dosages ranging from 10 to 50% of plastic waste treated with polyester polymer and covered with waste foundry sand as a sand replacement alternative at curing ages of 7, 14, 28, 56, and 180 days. The results showed an increase in the splitting strength by 80, 99, 79, 21, and 7% at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50%, respectively. After 7 days of polymer pretreatment for plastic waste, the adhesion between plastic particles and the cement matrix was enhanced, thus evenly distributing stress and preventing crack propagation when subjected to tensile loads. At 14 and 28 days, LWP-P20 exhibited the highest splitting strength with increasing ratios of 102.7 and 122%, which may be attributed to the combination of polymer-treated waste plastic with fine waste foundry sand at the 20% replacement level. A previous study [53] showed a similar trend for flexural strength when natural sand was partially replaced with different dosages of palm fuel ash from 10 to 40%. The flexure strengths ranged between 1 and 1.5 MPa, 1.1 and 1.65 MPa, 1.2 and 1.7 MPa, 1.4 and 1.9 MPa, and 1.45 and 1.95 MPa at 7, 28, 65, 90, and 180 days, respectively [12]. The composite material exhibited better tensile properties than other composites and conventional lightweight foamed concrete [15]. Adding fine waste foundry sand to the plastic surface enhances filling small gaps, resulting in a denser and more homogeneous matrix [54]. Owing to the uniformity of lightweight foamed concrete, tensile stresses are evenly distributed, reducing the formation of localized stress concentrations that may lead to cracking and structural failure. At later ages, a higher strength is obtained because fine particles occupy small empty spaces within the structure, resulting in a more compact and evenly distributed material [55,56]; hence, a higher strength is obtained. After a 20% replacement ratio, the strength slightly decreased from 1.7 MPa for LWP-P20 to 1.05 MPa for LWP-P10 as the presence of large amounts of plastic and waste foundry sand increases the number of contact points in concrete, which may serve as potential sites for crack formation and propagation [18,57]. Figure 12 shows the correlation between the splitting tensile strength and compressive strength, which showed a good relationship with an R 2 value of 0.94.

Splitting strength of lightweight foamed concrete.

Relation between compressive strength and splitting tensile strength.

3.7 UPV

Figure 13 illustrates the splitting strength results of lightweight foamed concrete with different dosages ranging from 10 to 50% of plastic waste treated with polyester polymer and covered with waste foundry sand as a sand replacement tested at curing ages of 7, 14, 28, 56, and 180 days. The results showed an increase in the UPV, which can be attributed to the application of polymers to plastic waste at all ages, from 2,604 m·s−1 for the control mix to 2,660 m·s−1 at 20% replacement at 7 days with a 2% increase ratio, from 2,641 to 2,690 m·s−1 with a 1.84% increase ratio at 14 days, and from 2,672 to 2,965 m·s−1 with a 10.9% increase ratio. Plastic waste treated with polyester polymers and covered with waste foundry sand improves the adhesion between components [58,59], whereas adding finely crushed waste foundry sand fills small empty spaces, resulting in decreased porosity and increased density, particularly at 28 days. Moreover, a consistent pattern indicates that the improved properties of concrete persist over time, thus enhancing its resilience and long-lasting nature, in addition to a more compact and uniform composition of concrete [23], which is associated with enhanced overall quality and reduced internal defects [60]. When the replacement level exceeds 20%, the UPV values may stabilize or decrease slightly compared to 20% but are still higher than the control mix. In conclusion, the improved microstructure is evident in high UPV measurements, which are directly related to the increased compressive, splitting tensile, bending strengths, and decreased absorption.

UPV for lightweight foamed concrete.

3.8 Sorptivity

Figure 14 illustrates the sorptivity results of lightweight foamed concrete with different dosages ranging from 10 to 50% of plastic waste treated with polyester polymer and covered with waste foundry sand as a sand replacement tested at curing ages of 28 days. The results showed absorption reductions of 16.37, 24.5, 30.4, 32,7, and 34.5% for LWP-P10, LWP-P20, LWP-P30, LWP-P40, and LWP-P50, respectively. This reduction can significantly improve the ability of concrete to resist water penetration and associated deterioration, which can also be attributed to the more sticky and compact structure of polymer-treated plastic waste. The greater the amount of plastic waste, the greater the densification of concrete [45,55,61], which not only enhances its mechanical qualities but also improves its durability by restricting water infiltration [58,62].

Sorptivity of lightweight foamed concrete.

3.9 Apparent porosity

Figure 15 illustrates the porosity results of lightweight foamed concrete with different dosages ranging from 10 to 50% of plastic waste treated with polyester polymer and covered with waste foundry sand as a sand replacement tested at curing ages of 7, 14, 28, and 90 days. As the curing process progresses, the cement becomes hydrated, and the polymer-treated waste plastic reacts with the waste foundry sand particles, thereby improving the microstructure of the concrete matrix [15,61,63]. Initial tests after 7 days indicated a significant reduction in porosity, ranging from 3.5 to 10.5% compared to conventional lightweight foamed concrete. This decrease can be attributed to the efficiency of filling empty spaces with processed plastic and foundry sand wastes. After 14 and 28 days, the concrete was subjected to additional compaction, which led to a significant decrease in porosity in all mixtures when 10–50% of the sand was replaced to record a reduction in porosity of approximately 4–11% After 90 days, the porosity of all mixtures reached a minimum as the porosity decreased from 58 to 51.5%. The mixture with 50% replacement showed the most significant improvement. Increasing the replacement ratio with the same water content leads to the filling of voids and the creation of denser microstructures by blocking the formation of large voids and improving the packing density, which can reduce porosity and sorptivity. Plastic waste cannot contribute to capillary action, decreasing the sorptivity. The synergistic effect of polymer processing and pozzolanic activity of waste foundry sand results in denser and less permeable concrete [16,62,64], thus improving its overall longevity and strength. Moreover, these results were confirmed by Bideci et al. [39], who investigated the physical properties of lightweight foamed concrete containing polyester-coated pumice and reported a high decrease in water absorption. Approximately 95% was obtained when the coated aggregate was utilized with mesh sizes of 4–8 and 8–16 mm.

Porosity of lightweight foamed concrete.

3.10 Drying shrinkage

Figure 16 shows the drying shrinkage evaluation results of lightweight foamed concrete with different dosages ranging from 10 to 50% of plastic waste treated with polyester polymer and covered with waste foundry sand as a sand replacement tested at curing ages of 1,3, 7, 14, 21, 28, and 56 days. Minimum shrinkage was obtained by increasing the replacement ratio. This increasing ratio was due to the reduced moisture content and increased internal tension [63,64] caused by the polymer and waste foundry sand particles. Concrete shrinkage continued to increase due to polymer-treated plastic waste’s effect on its moisture dynamics and internal structure [65,66]. However, plastic waste decreased the shrinkage for all replacement ratios compared to the control mix at 28 days. These shrinkages decreased at higher ages, as they underwent the most significant degree of shrinkage, with the most pronounced shrinkage occurring in the mix, in which 50% of the sand was replaced at 56 days. Good performance can be attributed to the chemical and physical properties of unsaturated polyester resin with low shrinkage, good filler, recommended for filling cracks [5,53], or a good choice for casting defects [67,68] owing to curing. The polyester used in this study was unsaturated cast-based polyester resin. The observation that 20% plastic waste substitution led to the least shrinkage across all curing ages is remarkable, as this feature is beneficial in concrete because it minimizes cracking potential and increases durability.

Dry shrinkage of lightweight foamed concrete.

3.11 Thermal conductivity

Figure 17 shows the thermal conductivity evaluation results of lightweight foamed concrete with different dosages ranging from 10 to 50% of plastic waste treated with polyester polymer and covered with waste foundry sand as a sand replacement tested for 28 days. The results showed a reduction in the thermal conductivity of 42% when sand was replaced with 50% waste plastic. This can be attributed to creating additional air pockets in the concrete matrix [24,69,70], thereby improving its insulating properties [71]. The intrinsic properties of the integrated materials, like waste foundry sand, have lower thermal conductivity than natural sand, reducing thermal conductivity from 0.48 at normal sand to 0.4, 0.35, 0.32, 0.29, and 0.28 W·m−1·K−1, enhancing the insulating effect. This ensures that the new composite is efficient for energy-efficient architectural plans [72–74] because it is vital in reducing the energy used for heating or cooling by reducing heat transfer and maintaining constant indoor temperatures [75,76].

Thermal conductivity of lightweight foamed concrete.

3.12 Thermal diffusivity

Figure 18 shows the thermal diffusivity evaluation results of lightweight foamed concrete with different dosages ranging from 10 to 50% of plastic waste treated with polymer and covered with waste foundry sand as a sand replacement tested at 28 days. Using waste plastic exhibited a significant gradual increase in lightweight foamed concrete thermal diffusivity from 0.409 to 0.46, with a 14.6% increase at a 50% replacement ratio. This increase can be attributed to decreased density with increasing replacement ratio; hence, more voids were formed. In addition, there is an overall increase in thermal diffusivity owing to the material’s ability to transfer heat more quickly [69,70], even though it has a lower thermal conductivity and rapid adaption to temperature changes owing to the polymer and foundry sand effect. Thus, the new composite can be used in special applications with unstable temperatures, such as thermal energy storage systems [68,69].

Thermal diffusivity of lightweight foamed concrete.

3.13 Specific heat capacity

Figure 19 shows the specific heat capacity evaluation results of lightweight foamed concrete with different dosages ranging from 10 to 50% of plastic waste treated with polyester polymer and covered with waste foundry sand as a sand replacement tested at 28 days. The results showed reductions in the specific heat capacities of 2.3, 5.6, 9.5, 13.6, and 18.7% at replacement ratios of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50%, respectively. As the replacement ratio increased, the total specific heat of concrete decreased from 721 to 585.5 J·kg−1·K−1 [54,57,71]. This means that foam concrete requires less energy to change its temperature [73], increasing sensitivity to temperature changes [51]. In addition, despite its insulating properties, waste foundry sand has lower specific heat than natural sand [14,74].

Specific heat of lightweight foamed concrete.

3.14 Environmental impact

In this study, the carbon emissions of foamed concrete with waste plastic were partially replaced with sand, and a slight decrease of approximately 1% in carbon dioxide emissions was observed because of the small difference between natural and foundry sand. Incorporating waste plastic as a substitute for sand in foamed concrete provides significant environmental benefits by reducing CO2 emissions and enhancing the sustainability of building materials [44]. Figure 20 reveals that, as the proportion of plastic waste increased, carbon dioxide emissions decreased slightly, with a significant reduction in the embodied CO2 index (CI) in mixtures containing up to 40% plastic replacement (LWP-P40). This emission reduction indicates that replacing natural sand with processed plastic waste can effectively reduce the environmental footprint of concrete production. However, the embodied CI increased slightly at higher replacement levels (LWP-P50), indicating an optimal range for achieving both environmental benefits and performance. This approach is consistent with development goals, as it enhances waste management and reduces dependence on natural resources.

CO2 emission and embodied CI of foamed concrete.

3.15 Microstructural assessment

Figure 21 shows the SEM images of the six mixes containing the control mix and three percentages of plastic waste as the sand replacement material. SEM images showed an enhancement in the microstructure with increasing solid matrix density and reducing voids with good distribution until a 20% replacement ratio with a high bond in the presence of more connecting points owing to the rough surface compared to natural sand, as shown in Figure 21(a)–(c). This is also in agreement with the compressive strength, splitting strength, and flexural strength results, with the recommendation of a 20% replacement ratio as the most effective dosage for balancing the natural sand content and partial replacement alternatives, as shown in Figure 21(a)–(c). For LWP-P 20, several pores with wider diameters were observed with connecting voids, which has also been reported in the literature [2,75]. Microcracks in the dense matrix were obtained for all replacement ratios due to the high bond effect and good distribution of plastic waste from the pre-treatment process [6,76,77]. A replacement ratio greater than 20% resulted in more significant strength loss and probability of crack propagation.

Microstructural analysis of lightweight foamed concrete: (a) control mix, (b) 10% waste plastic, and (c) 20% waste plastic.

4 Discussion

This study investigates the partial replacement of sand with treated waste plastic in foamed concrete, which significantly benefits the built environment regarding sustainability, performance, and energy efficiency. A replacement ratio of 20% was identified as optimal, achieving improved workability, reduced density, and enhanced mechanical properties, including a compressive strength of 24 MPa at 28 days. The durability was notably improved, with a 34.5% reduction in water sorptivity and a 10.5% decrease in porosity, ensuring better resistance to water penetration and prolonged structural integrity. The thermal conductivity decreased significantly (0.28 W·m−1·K−1 at 50% replacement), improving the insulation properties and supporting energy-efficient building designs. Using treated waste plastic reduces CO2 emissions, promotes resource efficiency, and enhances microstructure, aligning with sustainable construction goals. These findings demonstrate the potential of lightweight foamed concrete with treated plastic to meet the demands of modern, environmentally conscious construction, offering a durable, energy-efficient, and cost-effective material for diverse applications in the built environment.

5 Conclusion

This study evaluated lightweight foamed concrete for sustainable applications in a built environment by incorporating a composite of pre-treated plastic waste coated with polyester and waste foundry sand. Key performance indicators, such as workability, setting time, dry density, compressive strength, tensile strength, flexural strength, and UPV, were thoroughly analyzed. The thermal properties, including heat transfer, conductivity, and diffusivity, were examined to enhance energy efficiency. At the same time, durability factors, such as porosity, dry shrinkage, and sorptivity, were assessed to ensure structural longevity. Furthermore, microstructural analysis provides valuable insights into its potential for modern, eco-friendly, and resilient construction practices. Incorporating treated waste plastics reduced CO2 emissions, improved resource efficiency, enhanced the microstructure, and contributed to improved durability and thermal efficiency, aligning with sustainable and energy-efficient construction objectives. The following conclusions were drawn:

A 20% replacement ratio of natural sand with the new composite of lightweight foamed concrete optimizes workability, as it balances the properties of the composite with natural sand. In contrast, a 50% replacement disrupted the mix cohesion and stability, resulting in decreased workability compared to the reference mix.

The initial setting time of lightweight foamed concrete increased by 22.52–63% with higher replacement ratios of plastic waste, while the final setting time increased by 8.98–31.16%. This is attributed to the altered water absorption patterns from the treated plastic waste and the presence of polymer-coated particles and waste foundry sand in the lightweight foamed concrete.

The dry density of the lightweight foamed concrete decreased from 1,320 kg·m−3 in the control mix to 1,206 kg·m−3 at a 50% replacement ratio of sand with plastic waste. This is attributed to the lower density of waste plastic and the effects of the foaming agent, which enhanced the void distribution.

The compressive, splitting, and flexural strengths of lightweight foamed concrete improved at all replacement levels, with optimum values achieved at a 20% replacement ratio, resulting in increases of 84, 99, and 115%, respectively. The significant increase in the compressive strength correlates strongly with improvements in the flexural and splitting strengths.

The UPV increased for lightweight foamed concrete from 2,604 m·s−1 in the control mix to 2,965 m·s−1 at a replacement ratio of 28%, reflecting the improved density and reduced porosity. Water absorption and sorptivity decreased significantly for lightweight foamed concrete, enhancing durability, whereas shrinkage was minimized at a replacement ratio of 20%, although higher levels increased shrinkage over time.

Incorporating waste plastic in lightweight foamed concrete resulted in a 42% reduction in thermal conductivity and a 14.6% increase in thermal diffusivity at a 50% replacement ratio, enhancing the foam concrete’s insulating properties and energy efficiency. Additionally, the specific heat capacity of lightweight foamed concrete decreased by up to 18.7% at higher replacement ratios, indicating that foam concrete requires less energy to change its temperature.

Using plastic waste as a substitute for sand in foamed concrete is an effective approach for reducing CO2 emissions and promoting sustainability while improving resource utilization and reducing environmental impact in the construction sector.

SEM analysis revealed an enhanced microstructure of lightweight foamed concrete with reduced voids and increased solid matrix density up to a replacement ratio of 20%, correlating with improved mechanical performance. However, higher replacement ratios led to larger pores and an increased risk of crack propagation, indicating a potential strength loss of lightweight foamed concrete.

These findings demonstrate that incorporating treated plastic waste and foundry sand as a sand replacement in lightweight foamed concrete enhances mechanical strength, durability, and thermal efficiency while contributing to sustainability and CO₂ reduction in construction. A 20% replacement ratio was identified as the optimal balance, improving workability, strength, and shrinkage resistance, while higher replacement levels led to increased setting times, reduced density, and enhanced thermal insulation. The study confirms that this approach effectively enhances mechanical performance and energy efficiency, making it a viable and eco-friendly alternative for sustainable construction applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to JinhuaScience and Technology Planning Project: Jinhua Public Welfare Technology Application Research Projects (2023-4-046, 2023-4-047), Zhejiang Provincial College Students Scientific and Technological Innovation Activity (2024R479A008). The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through Project Number (TU-DSPP-2024-248).

-

Funding information: JinhuaScience and Technology Planning Project: Jinhua Public Welfare Technology Application Research Projects (2023-4-046, 2023-4-047), Zhejiang Provincial College Students’ Scientific and Technological Innovation Activity (2024R479A008). Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through Project Number (TU-DSPP-2024-248).

-

Author contributions: Z.Q.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation and writing – original draft. C.Q.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation resources, writing, reviewing, and editing. M.A.: data acquisition, writing, reviewing, data curation, visualization and editing. S.A.M.: conceptualization, supervision, resources, writing, reviewing, validation, and methodology. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Mo, K. H., U. J. Alengaram, and M. Z. Jumaat. A review on the use of agriculture waste material as lightweight aggregate for reinforced concrete structural members. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, Vol. 2014, 2014, pp. 1–9.10.1155/2014/365197Search in Google Scholar

[2] Bian, Z., Y. Huang, Y. Liu, J.-X. Lu, D. Fan, F. Wang, et al. A novel foaming-sintering technique for developing eco-friendly lightweight aggregates for high strength lightweight aggregate concrete. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 448, 2024, id. 141499.10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141499Search in Google Scholar

[3] Gencel, O., M. Oguz, A. Gholampour, and T. Ozbakkaloglu. Recycling waste concretes as fine aggregate and fly ash as binder in production of thermal insulating foam concretes. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 38, 2021, id. 102232.10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102232Search in Google Scholar

[4] Othuman Mydin, M. A., P. Jagadesh, A. Bahrami, A. Dulaimi, Y. Onuralp Ozkilic, and R. Omar. Enhanced fresh and hardened properties of foamed concrete modified with nano-silica. Heliyon, Vol. 10, No. 4, 2024, id. e25858.10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25858Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[5] Yang, F., Y. Hua, W. Feng, J. Zheng, and Y. Yang. Failure criterion and constitutive model for unsaturated polyester polymer concrete under true tri-axial compression. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 435, 2024, id. 136875.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136875Search in Google Scholar

[6] Hamada, H. M., A. Al-Attar, F. Abed, S. Beddu, A. M. Humada, A. Majdi, et al. Enhancing sustainability in concrete construction: A comprehensive review of plastic waste as an aggregate material. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, Vol. 40, 2024, id. e00877.10.1016/j.susmat.2024.e00877Search in Google Scholar

[7] Hanratty, N., M. Khan, and C. McNally. The role of different clay types in achieving low-carbon 3D printed concretes. Buildings, Vol. 14, No. 7, 2024, id. 2194.10.3390/buildings14072194Search in Google Scholar

[8] Lao, J.-C., B.-T. Huang, L.-Y. Xu, M. Khan, Y. Fang, J.-G. Dai, et al. Seawater sea-sand Engineered Geopolymer Composites (EGC) with high strength and high ductility. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 138, 2023, id. 104998.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.104998Search in Google Scholar

[9] Eriksen, M. K., K. Pivnenko, G. Faraca, A. Boldrin, and T. F. Astrup. Dynamic material flow analysis of PET, PE, and PP flows in Europe: evaluation of the potential for circular economy. Environmental Science & Technology, Vol. 54, No. 24, 2020, pp. 16166–16175.10.1021/acs.est.0c03435Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[10] Ali, B., M. Fahad, S. Ullah, H. Ahmed, R. Alyousef, and A. Deifalla. Development of ductile and durable high strength concrete (HSC) through interactive incorporation of coir waste and silica fume. Materials, Vol. 15, No. 7, 2022, id. 2616.10.3390/ma15072616Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Khawaja, S. A., U. Javed, T. Zafar, M. Riaz, M. S. Zafar, and M. K. Khan. Eco-friendly incorporation of sugarcane bagasse ash as partial replacement of sand in foam concrete. Cleaner Engineering and Technology, Vol. 4, 2021., id. 100164.10.1016/j.clet.2021.100164Search in Google Scholar

[12] Al-Shwaiter, A., H. Awang, and M. A. Khalaf. Performance of sustainable lightweight foam concrete prepared using palm oil fuel ash as a sand replacement. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 322, 2022, id. 126482.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126482Search in Google Scholar

[13] Jin, P., L. Li, Z. Li, W. Du, M. Khan, and Z. Li. Using recycled brick powder in slag based geopolymer foam cured at ambient temperature: Strength, thermal stability and microstructure. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 452, 2024, id. 139008.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.139008Search in Google Scholar

[14] Bhardwaj, B. and P. Kumar. Waste foundry sand in concrete: A review. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 156, 2017, pp. 661–674.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.09.010Search in Google Scholar

[15] Priyadarshini, M. and J. P. Giri. Use of recycled foundry sand for the development of green concrete and its quantification. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 52, 2022, id. 104474.10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104474Search in Google Scholar

[16] Selvakumar, M., C. Srimathi, S. Narayanan, and B. Mukesh. Study on properties of foam concrete with foundry sand and latex. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 80, 2023, pp. 1055–1060.10.1016/j.matpr.2022.11.462Search in Google Scholar

[17] Saikia, N., and J. De Brito. Use of plastic waste as aggregate in cement mortar and concrete preparation: A review. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 34, 2012, pp. 385–401.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.02.066Search in Google Scholar

[18] Guo, Z., Q. Sun, L. Zhou, T. Jiang, C. Dong, and Q. Zhang. Mechanical properties, durability and life-cycle assessment of waste plastic fiber reinforced sustainable recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 91, 2024, id. 109683.10.1016/j.jobe.2024.109683Search in Google Scholar

[19] Tayeh, B. A., I. Almeshal, H. M. Magbool, H. Alabduljabbar, and R. Alyousef. Performance of sustainable concrete containing different types of recycled plastic. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 328, 2021, id. 129517.10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129517Search in Google Scholar

[20] BSI. (2015). BS 1881–124:2015. Testing concrete–Part 124: Methods for analysis of hardened concrete. British Standards Institution, London, UK.Search in Google Scholar

[21] Gencel, O., B. Balci, O. Y. Bayraktar, M. Nodehi, A. Sarı, G. Kaplan, et al. The effect of limestone and bottom ash sand with recycled fine aggregate in foam concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 54, 2022, id. 104689.10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104689Search in Google Scholar

[22] Al Bakri Abdullah, M. M., Z. Yahya, M. F. Mohd Tahir, K. Hussin, M. Binhussain, and A. V. Sandhu. Fly ash based lightweight geopolymer concrete using foaming agent technology. Applied Mechanics and Materials, Vol. 679, 2014, pp. 20–24.10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.679.20Search in Google Scholar

[23] Amran, Y. H. M., N. Farzadnia, and A. A. Abang Ali. Properties and applications of foamed concrete; A review. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 101, 2015, pp. 990–1005.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.10.112Search in Google Scholar

[24] Risdanareni, P., A. Hilmi, and P. B. Susanto. The effect of foaming agent doses on lightweight geopolymer concrete metakaolin based. AIP Conference Proceedings, Vol. 1842, 2017, id. 020057.10.1063/1.4983797Search in Google Scholar

[25] Ibrahim, W. M. W., K. Hussin, M. M. A. B. Abdullah, and A. A. Kadir. Geopolymer lightweight bricks manufactured from fly ash and foaming agent, Vol. 1835, 2017, id. 020048.10.1063/1.4981870Search in Google Scholar

[26] Khan, Q. S., M. N. Sheikh, T. J. McCarthy, M. Robati, and M. Allen. Experimental investigation on foam concrete without and with recycled glass powder: A sustainable solution for future construction. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 201, 2019, pp. 369–379.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.12.178Search in Google Scholar

[27] BS EN12350-6. Testing fresh concrete: Density, British Standards Institution, London, UK, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[28] Li, M., H. Tan, X. He, S. Jian, G. Li, J. Zhang, et al. Enhancement in compressive strength of foamed concrete by ultra-fine slag. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 138, 2023, id. 104954.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.104954Search in Google Scholar

[29] BS EN 196-3. Methods of testing cement. Determination of setting times and soundness, British Standards Institute, London, UK, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[30] BS EN 12350-6. Testing fresh concrete Density, British Standards Institute, London, UK, 2016.Search in Google Scholar

[31] BS EN 12390-3. Testing hardened concrete. Compressive strength of test specimens, British Standards Institute, London, UK, 2011.Search in Google Scholar

[32] BS EN 12390-5. Testing hardened concrete. Flexural strength of test specimens, British Standards Institute, London, UK, 2019.Search in Google Scholar

[33] ASTM C469. Standard test method for static modulus of elasticity and Poisson’s ratio of concrete in compression, American Society for Testing and Materials, West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM International, 2002.Search in Google Scholar

[34] BS EN 12390-6. Testing hardened concrete. Tensile splitting strength of test specimens, British Standards Institute, London, UK, 2009.Search in Google Scholar

[35] BS EN 12504-4. Testing concrete in structures determination of ultrasonic pulse velocity, British Standards Institute, London, UK, 2021.Search in Google Scholar

[36] Cabrera, J. and C. J. Lynsdale. A new gas permeameter for measuring the permeability of mortar and concrete. Magazine of Concrete Research, Vol. 40, No. 144, 1988, pp. 177–182.10.1680/macr.1988.40.144.177Search in Google Scholar

[37] del Rey Castillo, E., N. Almesfer, O. Saggi, and J. M. Ingham. Light-weight concrete with artificial aggregate manufactured from plastic waste. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 265, 2020, id. 120199.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120199Search in Google Scholar

[38] Faraj, R. H., H. F. Hama Ali, A. F. H. Sherwani, B. R. Hassan, and H. Karim. Use of recycled plastic in self-compacting concrete: A comprehensive review on fresh and mechanical properties. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 30, 2020, id. 101283.10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101283Search in Google Scholar

[39] Bideci, A., Ö. S. Bideci, and A. Ashour. Mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight concrete produced with polyester-coated pumice aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 394, 2023, id. 132204.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132204Search in Google Scholar

[40] Dao, D. V., H. B. Ly, H. T. Vu, T. T. Le, and B. T. Pham. Investigation and optimization of the C-ANN structure in predicting the compressive strength of foamed concrete. Materials (Basel), Vol. 13, No. 5, 2020, id. 1072.10.3390/ma13051072Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[41] Ramamurthy, K., E. K. Kunhanandan Nambiar, and G. Indu Siva Ranjani. A classification of studies on properties of foam concrete. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 31, No. 6, 2009, pp. 388–396.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2009.04.006Search in Google Scholar

[42] Chen, H., R. Qin, C. L. Chow, and D. Lau. Recycling thermoset plastic waste for manufacturing green cement mortar. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 137, 2023, id. 104922.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2022.104922Search in Google Scholar

[43] Panda, S., A. Nanda, and S. K. Panigrahi. Potential utilization of waste plastic in sustainable geopolymer concrete production: A review. Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 366, 2024, id. 121705.10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.121705Search in Google Scholar PubMed

[44] Lim, S. M., M. He, G. Hao, T. C. A. Ng, and G. P. Ong. Recyclability potential of waste plastic-modified asphalt concrete with consideration to its environmental impact. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 439, 2024, id. 137299.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137299Search in Google Scholar

[45] Gencel, O., O. Yavuz Bayraktar, G. Kaplan, O. Arslan, M. Nodehi, A. Benli, et al. Lightweight foam concrete containing expanded perlite and glass sand: Physico-mechanical, durability, and insulation properties. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 320, 2022, id. 126187.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.126187Search in Google Scholar

[46] Selvi, M. T., A. Dasarathy, and S. P. Ilango. Mechanical properties on light weight aggregate concrete using high density polyethylene granules. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 81, 2023, pp. 926–930.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.04.302Search in Google Scholar

[47] Mohammadinia, A., Y. C. Wong, A. Arulrajah, and S. Horpibulsuk. Strength evaluation of utilizing recycled plastic waste and recycled crushed glass in concrete footpaths. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 197, 2019, pp. 489–496.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.192Search in Google Scholar

[48] Akbulut, Z. F., S. Guler, F. Osmanoğlu, M. R. Kıvanç, and M. Khan. Evaluating sustainable colored mortars reinforced with fly ash: A comprehensive study on physical and mechanical properties under high-temperature exposure. Buildings, Vol. 14, No. 2, 2024, id. 453.10.3390/buildings14020453Search in Google Scholar

[49] Haigh, R. The mechanical behaviour of waste plastic milk bottle fibres with surface modification using silica fume to supplement 10% cement in concrete materials. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 416, 2024, id. 135215.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135215Search in Google Scholar

[50] Kuzielová, E., L. Pach, and M. Palou. Effect of activated foaming agent on the foam concrete properties. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 125, 2016, pp. 998–1004.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.08.122Search in Google Scholar

[51] Chao, Z., H. Wang, S. Hu, M. Wang, S. Xu, and W. Zhang. Permeability and porosity of light-weight concrete with plastic waste aggregate: Experimental study and machine learning modelling. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 411, 2024, id. 134465.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134465Search in Google Scholar

[52] Sithole, N. T., N. T. Tsotetsi, T. Mashifana, and M. Sillanpää. Alternative cleaner production of sustainable concrete from waste foundry sand and slag. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 336, 2022, id. 130399.10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.130399Search in Google Scholar

[53] Hashemi, M. J., M. Jamshidi, and J. H. Aghdam. Investigating fracture mechanics and flexural properties of unsaturated polyester polymer concrete (UP-PC). Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 163, 2018, pp. 767–775.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.115Search in Google Scholar

[54] Hasheminezhad, A., A. Farina, B. Yang, H. Ceylan, S. Kim, E. Tutumluer, et al. The utilization of recycled plastics in the transportation infrastructure systems: A comprehensive review. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 411, 2024, id. 134448.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134448Search in Google Scholar

[55] Martins, M. A. B., L. R. R. Silva, B. H. B. Kuffner, R. M. Barros, and M. L. N. M. Melo. Behavior of high strength self-compacting concrete with marble/granite processing waste and waste foundry exhaust sand, subjected to chemical attacks. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 323, 2022, id. 126492.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126492Search in Google Scholar

[56] Sunita. Effect of biomass ash, foundry sand and recycled concrete aggregate over the strength aspects of the concrete. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 50, 2022, pp. 2044–2051.10.1016/j.matpr.2021.09.405Search in Google Scholar

[57] Sharma, D., N. Moondra, R. K. Bharatee, A. Nema, K. Sweta, M. K. Yadav, et al. Processing and recycling of plastic wastes for sustainable material management. Plastic Waste Management: Methods and Applications, Vol. 89, 2024, pp. 89–116.10.1002/9783527842209.ch4Search in Google Scholar

[58] Ferdous, W., A. Manalo, H. S. Wong, R. Abousnina, O. S. AlAjarmeh, Y. Zhuge, et al. Optimal design for epoxy polymer concrete based on mechanical properties and durability aspects. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 232, 2020, id. 117229.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117229Search in Google Scholar

[59] Heidarnezhad, F., K. Jafari, and T. Ozbakkaloglu. Effect of polymer content and temperature on mechanical properties of lightweight polymer concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 260, 2020, id. 119853.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119853Search in Google Scholar

[60] Ghosh, R., S. P. Sagar, A. Kumar, S. K. Gupta, and S. Kumar. Estimation of geopolymer concrete strength from ultrasonic pulse velocity (UPV) using high power pulser. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 16, 2018, pp. 39–44.10.1016/j.jobe.2017.12.009Search in Google Scholar

[61] Maglad, A. M., M. A. O. Mydin, S. S. Majeed, B. A. Tayeh, and S. A. Mostafa. Development of eco-friendly foamed concrete with waste glass sheet powder for mechanical, thermal, and durability properties enhancement. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 80, 2023, id. 107974.10.1016/j.jobe.2023.107974Search in Google Scholar

[62] Lu, Z., L. Su, G. Xian, B. Lu, and J. Xie. Durability study of concrete-covered basalt fiber-reinforced polymer (BFRP) bars in marine environment. Composite Structures, Vol. 234, 2020, id. 111650.10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.111650Search in Google Scholar

[63] Yang, L., C. Shi, and Z. Wu. Mitigation techniques for autogenous shrinkage of ultra-high-performance concrete – A review. Composites Part B: Engineering, Vol. 178, 2019, id. 107456.10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.107456Search in Google Scholar

[64] Maghfouri, M., V. Alimohammadi, R. Gupta, M. Saberian, P. Azarsa, M. Hashemi, et al. Drying shrinkage properties of expanded polystyrene (EPS) lightweight aggregate concrete: A review. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 16, 2022, id. e00919.10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e00919Search in Google Scholar

[65] Mosaberpanah, M. A., O. Eren, and A. R. Tarassoly. The effect of nano-silica and waste glass powder on mechanical, rheological, and shrinkage properties of UHPC using response surface methodology. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2019, pp. 804–811.10.1016/j.jmrt.2018.06.011Search in Google Scholar

[66] Hisseine, O. A., N. A. Soliman, B. Tolnai, and A. Tagnit-Hamou. Nano-engineered ultra-high performance concrete for controlled autogenous shrinkage using nanocellulose. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 137, 2020, id. 106217.10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106217Search in Google Scholar

[67] Akinyemi, B. A. and T. E. Omoniyi. Repair and strengthening of bamboo reinforced acrylic polymer modified square concrete columns using ferrocement jackets. Scientific African, Vol. 8, 2020, id. e00378.10.1016/j.sciaf.2020.e00378Search in Google Scholar

[68] Ahmed, S. and M. Ali. Use of agriculture waste as short discrete fibers and glass-fiber-reinforced-polymer rebars in concrete walls for enhancing impact resistance. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 268, 2020, id. 122211.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122211Search in Google Scholar

[69] Liu, M. Y. J., U. J. Alengaram, M. Z. Jumaat, and K. H. Mo. Evaluation of thermal conductivity, mechanical and transport properties of lightweight aggregate foamed geopolymer concrete. Energy and Buildings, Vol. 72, 2014, pp. 238–245.10.1016/j.enbuild.2013.12.029Search in Google Scholar

[70] Colangelo, F., G. Roviello, L. Ricciotti, V. Ferrándiz-Mas, F. Messina, C. Ferone, et al. Mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight geopolymer composites. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 86, 2018, pp. 266–272.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.11.016Search in Google Scholar

[71] Ahmad, J., A. Majdi, A. Babeker Elhag, A. F. Deifalla, M. Soomro, H. F. Isleem, et al. A step towards sustainable concrete with substitution of plastic waste in concrete: Overview on mechanical, durability and microstructure analysis. Crystals, Vol. 12, No. 7, 2022, id. 944.10.3390/cryst12070944Search in Google Scholar

[72] Mostafa, S. A., I. S. Agwa, B. Elboshy, A. M. Zeyad, and A. M. Hassan. The effect of lightweight geopolymer concrete containing air agent on building envelope performance and internal thermal comfort. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 20, 2024, id. e03365.10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03365Search in Google Scholar

[73] El Gamal, S., Y. Al-Jardani, M. S. Meddah, K. Abu Sohel, and A. Al-Saidy. Mechanical and thermal properties of lightweight concrete with recycled expanded polystyrene beads. European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering, Vol. 28, No. 1, 2024, pp. 80–94.10.1080/19648189.2023.2200830Search in Google Scholar

[74] Patil, A. R. and S. B. Sathe. Feasibility of sustainable construction materials for concrete paving blocks: A review on waste foundry sand and other materials. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 43, 2021, pp. 1552–1561.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.09.402Search in Google Scholar

[75] Khan, M., J. Lao, M. R. Ahmad, and J.-G. Dai. Influence of high temperatures on the mechanical and microstructural properties of hybrid steel-basalt fibers based ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 411, 2024, id. 134387.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134387Search in Google Scholar

[76] Panesar, D. K. Cellular concrete properties and the effect of synthetic and protein foaming agents. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 44, 2013, pp. 575–584.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.03.024Search in Google Scholar

[77] Qaidi, S., H. M. Najm, S. M. Abed, H. U. Ahmed, H. Al Dughaishi, J. Al Lawati, et al. Fly ash-based geopolymer composites: A review of the compressive strength and microstructure analysis. Materials, Vol. 15, No. 20, 2022, id. 7098.10.3390/ma15207098Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Towards sustainable concrete pavements: a critical review on fly ash as a supplementary cementitious material

- Optimizing rice husk ash for ultra-high-performance concrete: a comprehensive review of mechanical properties, durability, and environmental benefits

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae