Abstract

In this research work, recycled crushed bricks (CBs) were utilized as partial substitutes for fine aggregates in concrete mixes to enhance mechanical properties and promote sustainable construction practices. The main goal was to assess the mechanical properties and the behavior of concrete when a portion of fine aggregates is replaced with different amounts of CBs. Concrete samples were prepared by replacing normal fine aggregate with 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% CBs and also a control mix without the inclusion of CB, for compression strength (CS), splitting tensile strength (STS), and flexural strength (FS) assessment. It was found that adding refuse CB at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% of the fine aggregate weight increased the CS by 6, 12.8, 29.1, 39.7, and 48.3%, in that order. Accordingly, the STSs increased by 3.4, 13.3, 15.9, 17.9, and 28.2% for these ratios. The study revealed that the FSs of concrete combinations increased by 11.9, 23.8, 39.3, 45.2, and 48.8%. At a 50% CB level, CS increased by 48.3%, STS by 28.2%, and FS by 48.8% compared to the control mix. This enhancement is connected to the pozzolanic nature and the shape of CB particles, which contribute to better interaction within concrete. Moreover, one of the modeling approaches relied on empirical regression, correlation, and artificial neural networks, and was used to estimate the dependent variables CS, STS, and FS for concrete containing CBs, depending on the experimental results. These approaches were accurate enough to indicate their usefulness in predicting the mechanical characteristics of concrete structures with CBs. Incorporating CBs within concrete is in line with sustainable development as it helps to minimize waste emissions and preserve the use of raw materials. The addition of CBs in concrete contributes to the circular economy, which reduces the negative impact caused by conventional building materials. With the aim of replacing these traditional materials with less polluting alternatives, this research aims to enable a shift to more eco-efficient and responsible construction.

Abbreviations

- An

-

normalized age of the specimen (days)

- ANN

-

artificial neural network

- BCAn

-

normalized recycled brick coarse aggregate (kg·m−3)

- BFAn

-

normalized recycled brick fine aggregate (kg·m−3)

- CBs

-

crushed bricks

- Cn

-

normalized cement content (kg·m−3)

- CS

-

compressive strength

- CSn

-

normalized CS (MPa)

- EC2

-

Eurocode 2

- EDX

-

energy dispersive X-ray

- FS

-

flexural strength

- FSn

-

normalized flexural strength (MPa)

- ITZ

-

interface transition zone

- LM

-

the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm

- NCAn

-

normalized natural coarse aggregate (kg·m−3)

- NFAn

-

normalized natural fine aggregate (kg·m−3)

- SEM

-

scanning electron microscopy

- STS

-

splitting tensile strength

- STSn

-

normalized split tensile strength (MPa)

- Wn

-

normalized water (kg·m−3)

1 Introduction

The growing popularity of environmentally sustainable practices is catalyzing the development of new technologies that efficiently utilize or recycle by-products from various industrial processes [1,2,3]. In this context, concrete is the basic material used for construction and infrastructure worldwide. The widespread use of concrete in various structures has led to the generation of large volumes of concrete waste globally [4]. Therefore, the development and improvement of concrete and cement consistently attract attention from different perspectives. Reprocessing, reuse, and recovery are key strategies to manage concrete waste effectively. As one of these policies, discarded concrete is reprocessed as aggregates. Furthermore, the usage percentage is approximately 10%, which is very low. As the usage percentage increases, the mechanical properties of concrete are reduced because of the disadvantages of the reused aggregates. Thus, the usage ratio should be determined as accurately as possible.

Using recycled crushed bricks (CBs) is in harmony with sustainability goals all over the world since it cuts back on building waste and decreases the use of raw resources, thus supporting SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production). The inclusion of recycled raw materials in cement aligns with a circular economy because it promotes waste elimination and resource conservation. This not only addresses the issue of environmental pollution caused by the generation of construction waste but also enhances the use of different materials, improving consumption. In this context, this study is to summarize recent research on the use of recycled CBs and subsequently employ CBs as partial substitutes for fine aggregates in concrete mixtures to improve their mechanical characteristics.

In the literature, investigations on reused brick dust utilization have been performed on concrete blocks as aggregates. Furthermore, there are numerous research investigations on this topic. One such study was conducted by Sachdeva et al. [5]. In this study, Sachdeva et al. [5] investigated the influence of replacing sand with brick dust. At the end of this study, it was found that waste brick powder in the range of 5–10% might be chosen as a partial replacement for sand in mixtures of bituminous concrete.

Another investigation was performed by Letelier et al. [6]. In this study, Letelier et al. [6] used waste brick dust to replace cement at replacement levels ranging from 5 to 15%. Furthermore, Letelier et al. [6] used concrete with 30% recycled coarse aggregates instead of normal aggregates. At the end of this investigation, it was observed that 15% of the cement might be replaced by waste brick powder together with 30% of the reused aggregates without suffering significant losses in the strength of the final material compared to control concrete. The other study was conducted by Hiremath et al. [7]. Hiremath et al. [7] investigated the replacement of coarse aggregates with destroyed brick aggregates at volumetric replacement levels of 0, 25, 50, 75, and 100%. At the end of this investigation, it was detected that as the percentage of replacement of waste brick aggregates increases, both the strength and the density of the aggregates decrease. Furthermore, Hiremath et al. [7] observed that it can be an improved substitute for concrete, increasing strength by 25%. The other investigational study was conducted by Ge et al. [8]. In this study, Ge et al. [8] observed the influence of clay-brick powder on compression strength (CS), elastic modulus, and flexural strength (FS). To investigate these influences, a total of 17 combinations were established, containing one normal cement concrete as a reference. At the end of this study, Ge et al. [8] found that clay-brick powder can be reused to partially replace cement in concrete.

In another study, Ge et al. [9] observed three altered replacement stages (10, 20, and 30%); three forms of clay-brick powder with altered subdivision dimensions were implemented. At the end of this study, it was observed that clay-brick powder considerably reduced the slump of fresh concrete when the replacement level was above 10%. Furthermore, it was found that as the replacement level improved, the early-age strength decreased. O’Farrell et al. [10] also studied the distribution of pore dimensions of grout, which includes varying quantities of ground brick from dissimilar European forms. O’Farrell et al. [10] found an important correlation between the CS of the grout and the pore threshold radius. Dang et al. [11] detected the effect of reused aggregates from CBs with altered replacement percentages, subdivision dimensions, and added water content on the flow capability, CS, and FS of grout. At the end of this study, Dang et al. [11] found that the percentage of aggregates reused from CBs had a slight impact on grout strength.

In another study performed by Kumavat [12], the compressive stress and extension performance, as well as the mechanical properties of the clay brick wall and its components, clay bricks, and grout, were investigated through various laboratory examinations. At the end of this study, Kumavat [12] proposed simple methods for achieving the modulus of elasticity of bricks. Furthermore, the analytical model is practically accurate in calculating the stress–strain curves. Yang et al. [13] observed the mechanical and physical properties of recycled concrete containing high proportions of reused concrete and waste clay bricks and determined the probable restriction of reused aggregates used in primary concrete constructions. At the end of this study, Yang et al. [13] found that the most important effect on the physical and mechanical properties of fresh and hardened concrete is due to the presence of cement grout on the aggregate in the recycling aggregate and crushed clay bricks. Khatib [14] observed the presence of concrete with fine reused aggregate. For this purpose, the regenerated aggregate was made of crushed concrete or CB with subdivisions. Furthermore, fine aggregates were exchanged in different ratios of crushed concrete to CB. At the end of this investigation, Khatib [14] found that the strength of crushed concrete decreased by 15–30%.

On the other hand, concrete with up to 50% CB exhibits comparable long-term strength to the reference sample. The other study was conducted by Shaaban et al. [15]. The purpose of this research was to investigate the impact of the curing and drying regime on the strength and permeability properties of concrete containing both crumb rubber and steel fibers extracted from scrap tires. For this purpose, the discarded tire extracts were used to create five different concrete mixtures, and the resulting concrete was cast into cubes, cylinders, and prisms. It was found that the both FS and splitting tensile strength (STS) were greater than those of the control mix by 21 and 22.6%, respectively. Mohammed et al. [16] investigated the possibility of reusing aggregate concrete made from destroyed bricks as coarse aggregate. The specific gravity, absorption capacity, and abrasiveness of the recycled aggregates were among the features evaluated. According to the findings of this study, recycled brick aggregates have the potential to be used as coarse aggregates in the production of concrete with strength ranging from 20.7 to 31.0 MPa. Schackow et al. [17] investigated fired clays and demolition waste. At the end of this study, they evaluated the properties of typical fresh and hardened mortar resulting from the partial replacement of Portland cement by clay brick waste up to 40% by weight.

Bhatta et al. [18] investigated the use of CBs instead of natural coarse aggregate in concrete and investigated the effect of CB dust in the ratios of 0, 15, 20, and 25% by weight. According to the findings of the study, fluctuations of up to 20% preserve durability and have potential uses in the building industry. The other study was performed by Kumar and Rana [19]. In this study, CB aggregates were used at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% to substitute for natural coarse aggregates in M20-grade concrete. The findings demonstrated that concrete with up to 30% CB as coarse aggregate retained workability and CS and tensile strength values were comparable to those of ordinary concrete. Nonetheless, replacement levels over 30% exhibited substantial declines in compressive and tensile performance. Consequently, it was determined that CB aggregate is optimal for applications utilizing it up to 30%. Zhao et al. [20] performed another investigation. The objective of this investigation was to employ waste CB to create artificial fine aggregates that are based on waste CB through the use of a high-speed agitating method. To examine the CSs of individual particles in artificial fine aggregates with varying raw material proportions, six series of waste brick power-based artificial fine aggregates were created. At the end of the examination, it was found that concrete using 20% conventional Portland cement and artificial fine aggregates had higher splitting tensile and cubic CSs than concrete containing natural and recycled fine aggregates. Rocha et al. [21] performed another investigation to examine the strength impact of using recycled brick powder in concrete as a partial substitute for Portland cement by substituting recycled brick powder for 5–10% of Portland cement in two strength designs (20 and 25 MPa). To investigate the mechanical behavior of concrete subjected to high temperatures, Sweety Poornima Rau and Manjunat [22] studied the use of brick fines that were replaced with sand at varying percentages of 5, 10, 15, and 20%. It was found that 15% brick thin concrete had the maximum strength in the testing, regardless of temperature. In addition, it was discovered that the CS increased at 100°C before progressively declining as the temperature increased.

2 Scope of the study

As may be observed earlier, there have been several investigations into the production of concrete with reused crushed clay bricks in the literature. On the other hand, there is limited research included within the published literature about the empirical prediction of the concrete varying concentrations of CB dust. In addition, there are extremely few investigations on the impact of CB dust refuse. This study aims to fill the existing gap in the literature by determining the strength properties of concrete according to the optimum amount of CB powder and hence to highlight the contribution of CB dust to the strength properties. Therefore, this investigation contributes significantly to the literature. For this purpose, it was decided to replace the CB dust with five different percentages: 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50%. A total of 18 tests were performed, with three tests for every percentage change and one test for each variable. By conducting CS, STS, and FS tests, the concrete strength values of the concrete were determined. Details provided in the following sections. The optimal amount of CB derived from the present study will vary from values in the existing literature by demonstrating the viability of using recycled concrete to enhance mechanical strength while simultaneously reducing environmental effects associated with construction.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Experimental methods

Reused CB dust obtained from the local market is presented in Figure 1 and is modified with fine aggregates to obtain environmentally friendly concrete. The size of CB dust was approximately 0–4 mm. CB dust replaced fine aggregate at five levels: 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50%. CB dust was obtained from the demolished buildings. To create the concrete, CEM 1 (32.5 g) was used. The ratio of water to cement consumed was 0.46. The percentage of cement in the total aggregate was 0.34. In the design combination used, superplasticizer was not utilized. Pictures related to the preparation of test specimens according to appropriate standards are presented in Figure 2. The slump test was performed according to the ASTM C143: Standard Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic-Cement Concrete [23]. Figure 3 presents the slump test results for the percentage of CB dust discarded in the replacement of fine aggregate. Five altered CB dust contents for fine aggregates were identified, indicating the optimum cost and conductivity. The findings show that slump values decreased as the incorporation of CB dust increased for the replacement of fine aggregates. Table 1 shows the mix design for the concrete mix with CBs.

CB dust.

Perform test instances.

Slump test inferences.

Mixture of the concrete (kg·m−3)

| Mixture (%) | Cement | Water | Fine aggregate | Coarse aggregate | CB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 580 | 270 | 780 | 900 | 0 |

| 10 | 580 | 702 | 78 | ||

| 20 | 580 | 624 | 156 | ||

| 30 | 580 | 546 | 234 | ||

| 40 | 580 | 468 | 312 | ||

| 50 | 580 | 390 | 390 |

Figure 2 presents the visuals related to the experimental process used in the study. In the first stage, the CB dust was mixed with the other components in a mixer to create a homogeneous gray mixture. This indicates that the CB dust interacted appropriately with the water and aggregates, ensuring the workability of the mixture. The workability of the mixture in its fresh state was evaluated through a slump test. Low slump values in concrete mixtures containing recycled materials are associated with porosity. This test is crucial for predicting the workability performance of the mixture. In the final stage, concrete samples were poured into molds, allowed to set, and then cured for mechanical and microstructural testing. These samples comprise the primary dataset for the experimental phase of the study.

Figure 3 shows that as the percentage of CB added to the concrete mixture increases, the slump value decreases significantly. The control sample, which contained no CB, had a slump value of approximately 22 cm. Increasing the CB ratio resulted in the following slump values: 20 cm at 10%, 16 cm at 20%, 14 cm at 30%, 8 cm at 40%, and 6 cm at 50%. This decrease is directly related to the high water absorption capacity and porous structure of the CB dust. CB absorbs some of the free water in the mixture, reducing workability. In addition, increased friction within the aggregates due to particle shape and surface roughness limits the flowability of fresh concrete. These results suggest that increasing the CB additive ratio may necessitate adjustments to the water-to-binder ratio or the incorporation of additives that enhance consistency. From a construction application perspective, a low slump value can lead to placement difficulties and increased vibration requirements. Therefore, achieving an appropriate balance between environmental benefits and workability performance is crucial.

3.2 Microstructural analysis

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) is widely used in the field of materials science to investigate the microstructure and morphology of materials in detail and to understand their chemical and physical properties. The resolution of SEM is typically of the order of a few nanometers, allowing detailed analysis of the surface morphology and microstructure of a sample. Proper sample preparation is essential for obtaining high-quality SEM images. The samples were thoroughly cleaned and dehumidified. It is also important to choose appropriate imaging parameters, such as electron beam energy and detector settings, to optimize SEM image quality. SEM analysis with 10, 20, and 100 µm was taken to evaluate the microstructure of the concrete.

Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis is crucial for assessing the composition, durability, and environmental impact of concrete. Information about the ratio of the concrete components, especially the quality and ratio of the materials used in the construction of the concrete, can be obtained. EDX analysis of the added brick powder can help to define the chemical composition of the brick powder in the concrete, as well as to understand the factors that affect the ratio of elements in the concrete, its durability, hardness, and other properties. EDX analysis was performed for two different areas.

3.3 Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test

ANOVA test is a statistical analysis method and is used to determine whether there is a significant difference between the mean values of different groups. In other words, ANOVA tests whether the difference between groups is significant. In this study, the effect of CB admixture ratio on FS, CS and STS mechanical strengths in concrete was investigated by single factor ANOVA to determine whether the differences between experimental data were statistically significant. MiniTab 22 software was used to perform the ANOVA test. When the variance percentages of all the factors specified in the source are added, the total variance should reach 100%. The P value here indicates whether the result obtained while testing a hypothesis is significant. The P value being less than 0.05 in all parameters indicates that the result is significant.

3.4 Artificial neural networks (ANNs)

ANNs are machine learning models inspired by the structure and function of biological neural networks [24,25]. It is made up of many interconnected processing nodes, or neurons, that cooperate to learn from data by varying the strength of the connections among nodes in response to the input. A single layer (perceptron) is used because of several advantages, such as simplicity, efficiency, and linear separability. Each ANN layer comprises the required number of neurons. There should be an optimal number of neurons selected for ANN. If the number of neurons is high, there should be overfitting of data, and if the number of neurons is low, there should be underfitting. To select the optimized activation functions, a hyperbolic tangent (Tanh) function was selected because the data were distributed between −1 and +1.

The data were preprocessed using normalization techniques prior to prediction. Normalization techniques must be incorporated into the data preprocessing for machine learning. The normalization technique adopted in this modeling is shown in Eq. (1). The Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm, utilizing the TANSING activation function, was employed to predict the capacities. The LM algorithm optimizes the weights and biases of the ANN by minimizing the difference between the expected and actual outputs for each input–output combination in the training data. Iteratively, the weights and biases of the network are adjusted based on the discrepancies between the expected and actual output. This study employed a feedforward propagation technique, using the mean square error as the performance metric.

4 Experimental test implications and discussions

The most important objective of this investigative study is to attain an extensive investigation of cement from several manufacturers consumed with specific amounts of fine aggregates related to CB dust. To reach this aim, the amount of fine aggregate replaced by the waste CB dust was varied as 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% in the concrete mixture, and the impact of the discarded CB dust was also measured. At the end of these examinations, the completion of the CS, STS, and FS tests is ensured. Furthermore, SEM analyses were performed. Examination implications are offered in the following subsections. Table 2 summarizes the outcomes obtained from all tests based on the CB ratio.

Summarized results

| Number of sets | W f ratios (%) | CS | STS | FS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 0 | 17.18 ± 1.19 | 1.42 ± 0.08 | 8.43 ± 0.38 |

| #2 | 10 | 18.21 ± 1.11 | 1.46 ± 0.04 | 9.38 ± 0.31 |

| #3 | 20 | 19.38 ± 1.48 | 1.61 ± 0.06 | 10.41 ± 0.60 |

| #4 | 30 | 22.17 ± 0.88 | 1.64 ± 0.11 | 11.73 ± 0.19 |

| #5 | 40 | 24.00 ± 0.72 | 1.67 ± 0.05 | 12.24 ± 0.71 |

| #6 | 50 | 25.47 ± 0.68 | 1.82 ± 0.09 | 12.47 ± 0.42 |

4.1 Detailed investigation of the influence of CS

The size of the cube section was set to 150 mm × 150 mm × 150 mm. In this examination, samples containing altered amounts of fine aggregate related to CB dust were examined under a longitudinal limitation load, causing disruptions in the specimens. At this stage, compression ability was expected to initiate from a severe failure point, related to the number of specimens. As shown in Figure 4, the CS values were detected at 28 days using a design with 100% reference aggregates and varying amounts of aggregates replaced for reference aggregates, with both without the inclusion of CB dust. As observed in Figure 4, for a small dust percentage, the CSs of concrete mixtures with discarded CB dust as a partial aggregate replacement were larger than those of the steady concrete mixtures lacking CB dust. Aggregates of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% were replaced with CB dust, and the CSs of the concrete admixture were enhanced to 6, 12.8, 29.1, 39.7, and 48.3%.

Inferences of CS.

A numerical investigation confirmed the significant impact of CB dust on concrete properties, where aggregate was replaced with CB dust on the CS of the concrete up to 50% exchange. This condition may be due to the chemical and physical characteristics of concrete residue. Adamson et al. [26] considered the permanence of reinforced concrete prepared with CB as an aggregate and observed that natural coarse aggregates could be replaced with CBs without significantly altering the durability of concrete, even in the absence of steel reinforcement. Furthermore, it was established that the cylinders with brick aggregates were considerably stronger than those with normal soil as the control mixture; the strength increased as a result of improving the brick content due to the lower strength of natural aggregates. Adamson et al. [26] also suggested that this rise in CS is more profound as brick aggregates replace more natural aggregates. It was observed that the results obtained from this study were in parallel with those obtained from similar studies in the literature. Janković et al. [27] also found that CS was greater than predicted.

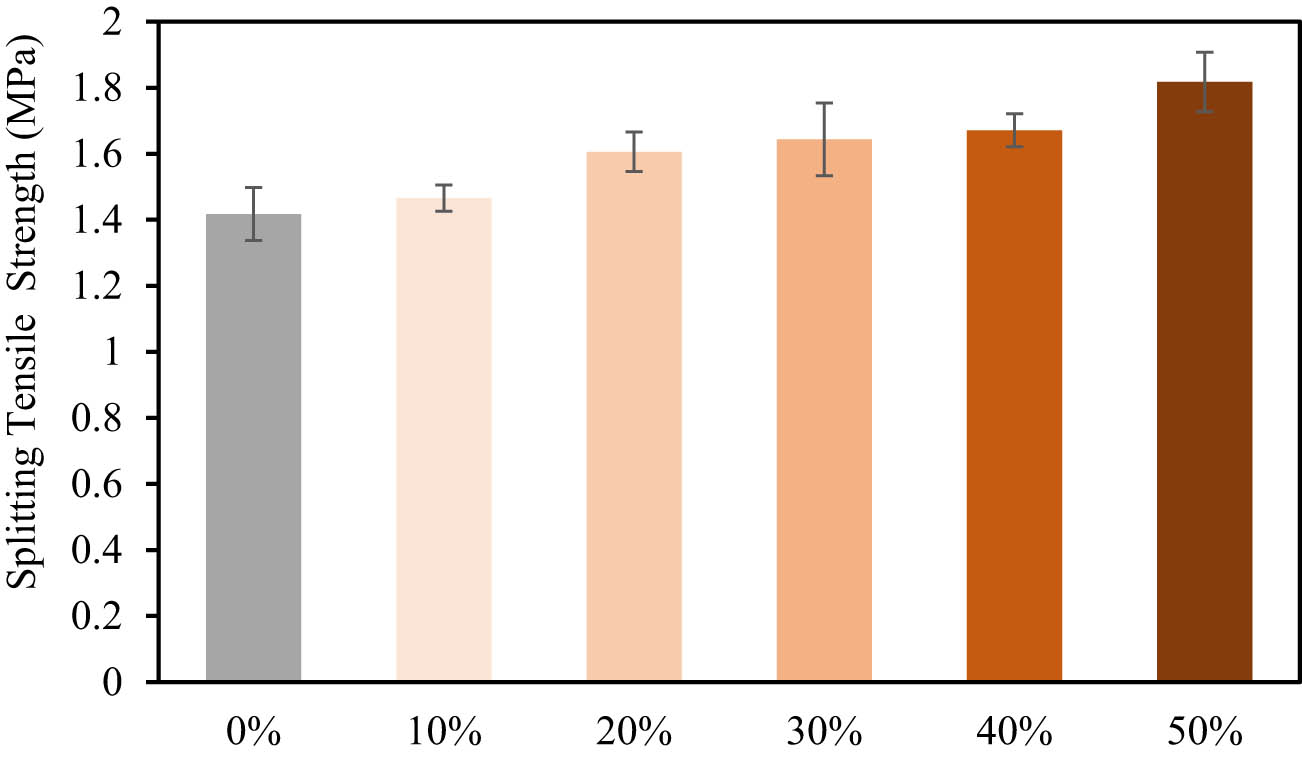

4.2 Detailed investigation of the influence of STS

An approximation of the comparative STS of several concrete percentage combinations, arranged with 100% reference, and various amounts of reused CB dust-swapping fine aggregate with 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% in the concrete mixture, has been provided in Figures 5 and 6. As shown in Figure 6, the extrapolations of the STS test show a tendency similar to that of the CS. As presented in Figure 5, aggregates of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% were exchanged with refuse CB dust. The STS of concrete increased by 3.4, 13.3, 15.9, 17.9, and 28.2% with the increasing CB content. As shown in Figure 5, the optimal tensile strength values were established at 50% CB dust content, requiring maximum concentrated tensile strength. While the amount of the refuse CB dust increased from 10 to 50%, it is noticed that values of tensile strength show an increase. As stated earlier, a numerical investigation of the sample inferences showed that exchanging 50% of the aggregate with CB dust significantly affected the STS of concrete.

STS tests.

STS results.

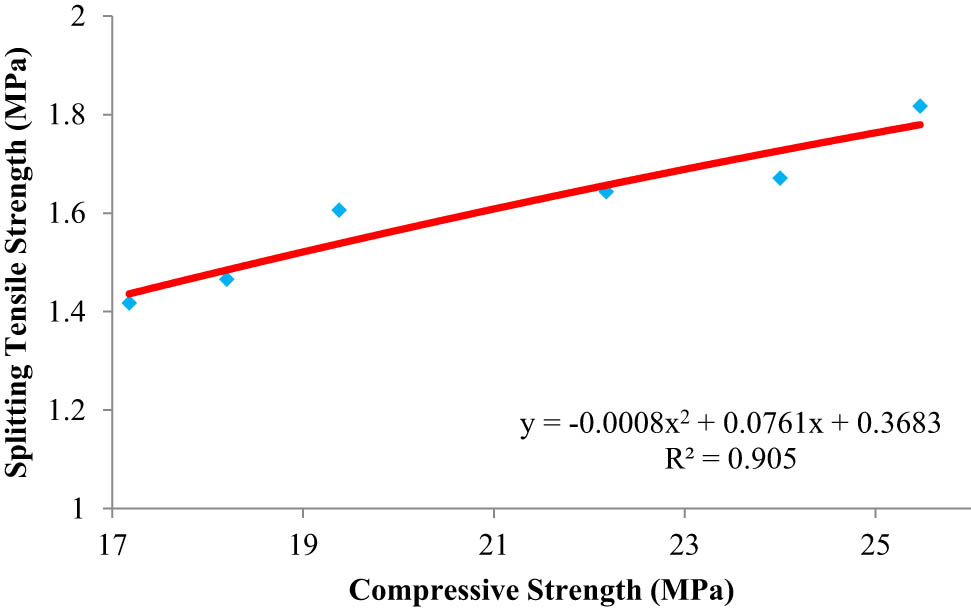

The relationship between CS and STS is also presented in Figure 7. As shown in Figure 7, the relationship between the CS and STS is nearly linear. Moreover, as shown in Figure 7, the regression plot describes a strong relationship among CSs compared due to STS, with an R 2 greater than 90% for aggregate replacement. Similar consequences have been described in the literature. Hansen [28] reported that the STS of concrete reinforced with CB aggregate improved by 10% compared to the control concrete. Khaloo [29] also found enhancements of 2 and 15% in STS when the concrete was prepared with CB aggregate. It was reported that the increase in tensile strength might be due to the rough surface texture of these aggregates offering better bond when coarse aggregates are combined with concrete. In addition, stone dust is better than natural sand due to its ability to block the holes in the interfacial transition zone with silica, which may ultimately decrease the quantity of calcium hydroxide. Its extraordinary pozzolanic reactivity densifies the interfacial transition zone, permitting the active load transfer between the aggregate and cement grout, leading to greater strength [30].

STS comparison using CS for aggregate replaces.

4.3 Detailed investigation of the influence of flexural performance tests

The significance of examples experiencing flexural stress may be understood as related to the tensile strength of the CB dust specimen, as illustrated in Figure 8. The FS investigation was proposed for beam specimens of size 100 mm × 100 mm × 400 mm. The FS of the specimens was observed. The strength of the reused aggregate, which replaced the fine aggregate, ranged between 8.4 and 12.5 MPa. In Figure 9, the FS is obtained due to increased percentages of refuse CB. As stated earlier, aggregates of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% were replaced with refuse CB, and the FSs of the concrete combinations were enhanced by 11.9, 23.8, 39.3, 45.2, and 48.8%. Statistical examination of the section conclusions presented the important benefits when CBs were used as an alternative (as aggregate was exchanged with waste CB) to the failure strength (FS) of concrete, until 50% exchange. The increase in the FS of the examples is shown in Figure 9. The comparable compressive capacity of concrete, failure strength, also increased with the replacement percentage of discarded CB, up to 50%.

FS test.

Effects of crushed brick.

The aim of improving performance was to utilize the pozzolanic action of CB waste and improve grain-dimension dispersion, which resulted in good bonding between the CB waste and cement–soil matrix [31]. In addition to pozzolanic considerations, restrictions such as form and unevenness of CB waste contribute to strength increase [32]. It was observed that the results obtained from this study were in parallel with those obtained from similar studies in the literature. The CS and FS strength results are presented in detail in Figure 10. The results demonstrate that the advantage for CB refuse combinations was greater than for the control combination. The maximum strength was observed in the combination with 50% waste CB for both the CS and FS in the examples’ strong points. This is because the CB waste is evident in a natural pozzolanic material, and silicate oxide (SiO2) reacts chemically with Ca(OH)₂ (alkali resulting from cement hydration) to form a cementitious product, which is responsible for the strength progress of grout [33,34,35]. The additional purpose is that fine subdivisions of CB refuse might efficiently fill the voids that contribute to enhancing the concrete microstructure [10].

FS vs CS.

5 The empirical models of the mechanical properties

In the literature, the following experimental equations have been proposed for the compressive and flexural tensile strengths and CB waste percentage based on experimental consequences. The correlation between FS and CS is offered in Eq. (2) by Mansoor et al. [35] is as follows:

To compare the investigational performance of concretes with refuse CB with that expected according to technical regulations; ACI 318 and Eurocode 2 (EC2) were chosen to estimate the FS related to the CS values. ACI 318 offers the subsequent equations.

where f

r is defined as FS, and

In the aforementioned equation, f ctm,fl represents the FS following EC2, and h is the height of the sample. Furthermore, f ctm is defined as the mean of the FS attained, using f ctm = 0.3(f ck)2/3. Here, f ck denotes the measured values attained of CS, reduced by 8 MPa. In this investigative research, based on the experimental test results, the following calculations are presented for CS to FS and CS to STS for the partial replacement of fine aggregates in Eqs. (5) and (6), respectively.

Comparison of the FS and STS with the models in the literature is depicted in Figures 11 and 12.

Comparison using different codes for FS.

Comparison by the use of different codes for STS.

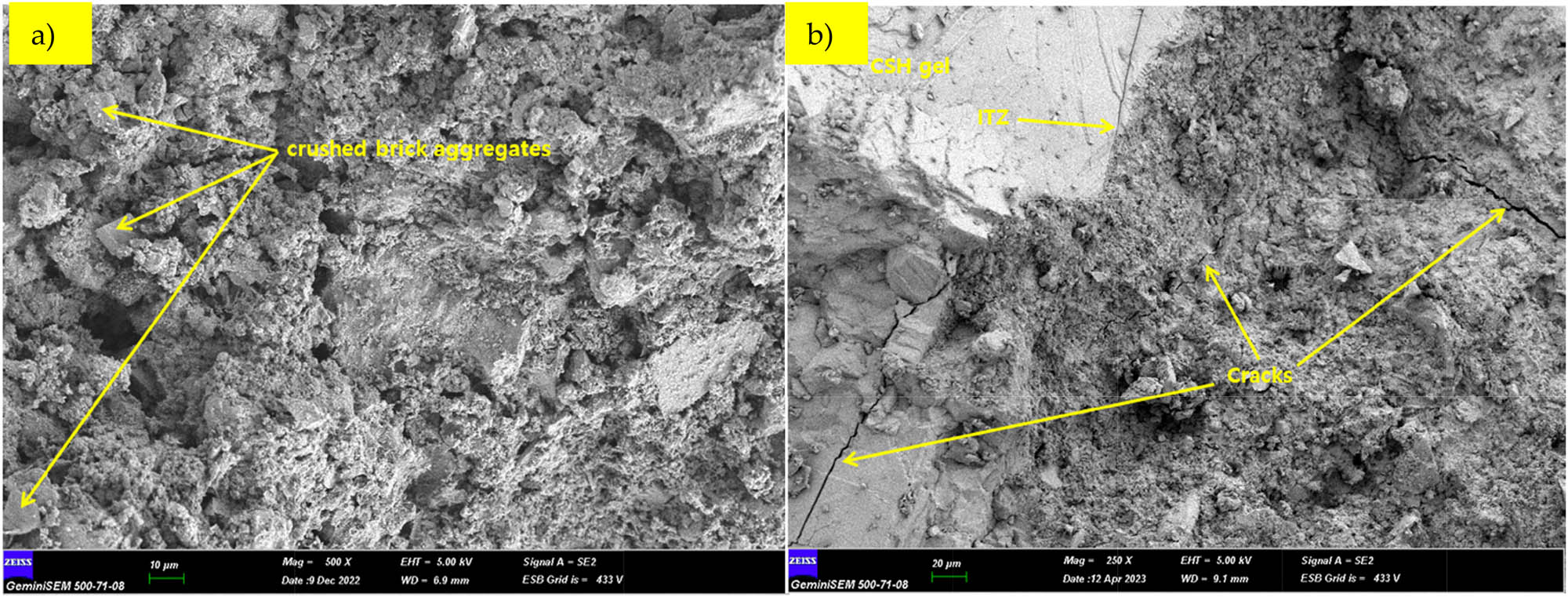

6 SEM analysis

The SEM image in Figure 13(a) illustrates that the material obtained with the additive CB was used as a substitute for fine aggregate, thereby achieving a strong bond in the resulting concrete. Along with providing good bonding around coarse aggregates, the crack and pore formations are also noteworthy. In general, it can be observed that it provides good hydration by replacing fine aggregates with waste CBs. The pores and formation of cracks in the images are disadvantageous to concrete strength. Pores in concrete are a key factor affecting strength. As Figure 13a shows, pore size distribution significantly affects the macrolevel permeability and mechanical strength of concrete. Large pores can negatively impact long-term durability by allowing water and harmful ions to penetrate. Figure 13b shows the micropores in detail. This microstructure directly affects the density of the binder phase (C–S–H) and overall concrete durability. The cracks and interconnected pores in Figure 13a indicate high water absorption, which reduces resistance to freeze-thaw cycles. Brick aggregates generally have higher internal porosity than natural aggregates, which can significantly increase the total pore volume. This can negatively impact the concrete overall permeability and long-term durability of the concrete. The pore structure develops based on factors such as water and air bubble entrapment during the mixing process, aggregate surface roughness, and the water-to-cement ratio. High water-to-cement ratios, in particular, can lead to the formation of a porous internal structure after the hydration process. However, proper mix design and compaction techniques can minimize pore and crack formation, significantly improving the mechanical properties and durability of concrete. If large amounts of water are added to the mix or if it remains in contact with water for a long time, ettringite crystals may form, thereby reducing the durability of the concrete. This can also cause concrete to become more susceptible to temperature changes and freeze-thaw cycles [36,37]. Figure 13(b) shows ettringite formation and partial C–S–H gel formation on the concrete surface. In similar studies, this was expressed as a delayed formation of ettringite [38,39].

SEM analysis with (a) 100 µm and (b) 1 µm.

Moreover, Figure 13a shows that most of the pores are in the 10–30 µm diameter range. This is usually linked to the higher porosity and uneven surface structures of CB aggregates [40]. In addition, significant increases in density were observed in the 30–40 and 70–80 µm ranges, indicating that pores of certain sizes form more frequently, reflecting the influence of the aggregate structure. However, Figure 13a also shows the presence of some large-diameter pores (over 100 µm). Such large pores can increase the total concrete porosity, which negatively affects mechanical strength and leads to high water absorption rates [41]. Furthermore, such large pores may increase sensitivity to structural damage during freeze–thaw cycles [42].

In Figure 14(a), it is observed that the waste CB and fine aggregate exhibit good bonding with the binding cement. The homogeneity of the distribution ensures good concrete quality. Despite the micro voids, the crushed refuse brick aggregate improved the concrete strength when properly mixed. The interface transition zone (ITZ) is where different materials in the concrete meet. This zone, which has a different structure, can influence the strength, hardness, and crack resistance of concrete. In Figure 14(b), near the ITZ border, the cracks are noticeable. Cracks occurring in both the Gel and mixture regions may be considered detrimental. Hydration does not completely occur in the ITZ region due to insufficient water. Adding too much water may increase the formation of pores and cracks. Hydration in the ITZ region can be increased by a balanced mixture and placement without exceeding the proportion limits. In addition to the sample preparation technique, the surface quality of the aggregate, the degree of infiltration, and chemical bonding affect ITZ formation. Although the effects of these materials vary in the literature, it is generally accepted that an increase in mortar-aggregate bond strength increases the concrete strength [43].

SEM analysis with (a) 10 and (b) 20 µm.

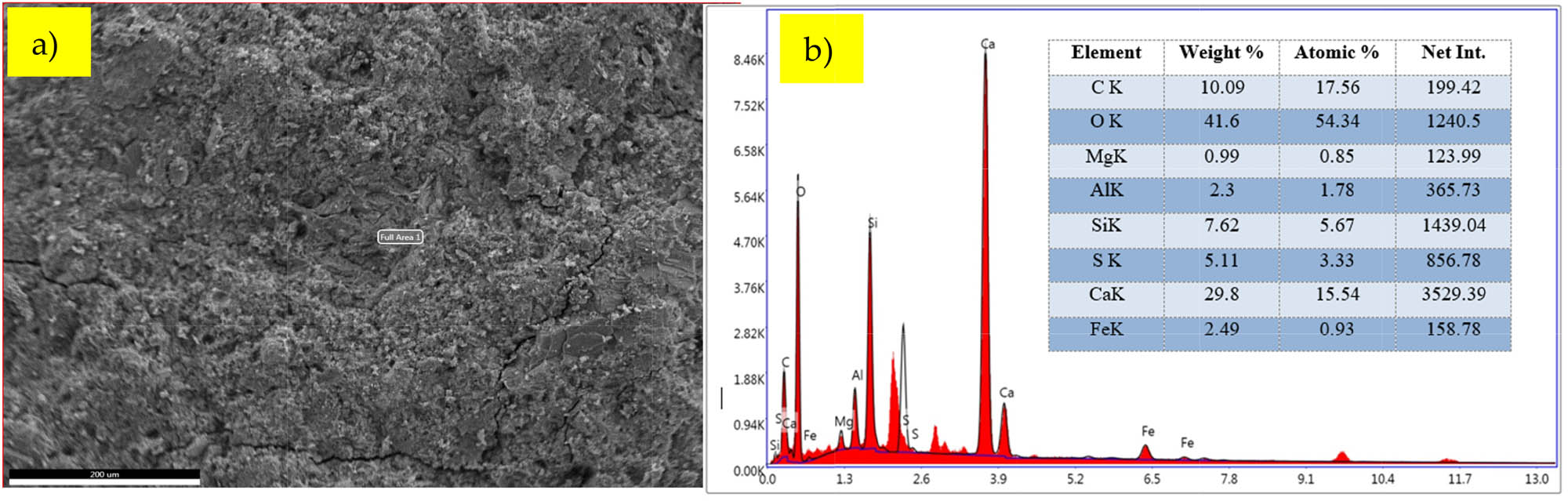

7 EDX analysis

EDX results for the concrete produced with CB are shown in Figure 15(a). A new ITZ and C–S–H gel formation is observed. The image also confirms the SEM analysis results. The element absorption rates within the structures are detailed in Figure 15(b). According to the full area analysis, focusing on one point, the presence of many elements and the height of some elements are highlighted in Figure 15. Each element in concrete is vital for hydration. In addition to the subdivision size of the elements, mixing proportions affect the structural integrity of concrete [44]. CB may contain many different elements depending on their intended use. Aluminum and calcium concentrations have attracted attention in this study. Calcium primarily affects the early setting and strength gain of concrete. Among the nine elements in total, magnesium (Mg), known for its lightness and silver color, is an alkaline earth metal, while carbon (C), oxygen (O), and aluminum (Al), known for its ductility, and silicon (Si), one of the most common elements in nature, are not. The presence of calcium (Ca) and iron (Fe) was observed in the structure. The presence of Al with a weight ratio of 2.31 indicates ettringite formation in the structure [45,46]. The highest rate of Ca and the presence of Si provided proof of C–S–H gel formation [47].

(a) SEM for EDX and (b) EDX spectra from area 1.

The pozzolanic reaction occurs when materials containing silica (SiO₂) and alumina (Al₂O₃) react with the calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂) present in their environment. This reaction forms calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gels, which serve as secondary binding phases. The high levels of calcium (Ca) and silicon (Si) detected in the EDX analysis obtained in this study are a strong indicator of C–S–H gel formation. In addition, the dense, the homogeneous microstructure observed in the SEM image indicates that the reaction occurred extensively and microporous, gel-like products were formed.

Although XRF analysis was not performed, the EDX data clearly confirm that the pozzolanic reaction occurred successfully, resulting in the formation of Ca- and Si-based binding gel phases. Elemental distribution and microstructural observations reveal that the recycled brick additive is not merely an inert filler in the mixture but rather a chemically active component within the binding matrix.

The formation of cracks was observed in scanning a different area in Figure 16(a). Although these cracks are observed as negative, it has been observed that the Al percentage in the structure increases the ductility. In the first stage, the reaction of water with calcium–silicate in cement triggers the formation of C–S–H. In appearance, C–S–H formation increases the durability of concrete by holding the internal structure together, reducing voids and water permeability, and increasing resistance to cracks. Figure 16(b) exhibits a homogeneous distribution in every area of the sample. In addition, even if its content is low, the presence of sulfur (S) is important for solidification. The presence of Ca at many points within the observed region provides evidence that it increases the durability of the concrete.

(a) SEM for EDX and (b) EDX spectra from Area 2.

8 ANOVA test results

At this stage of the study, ANOVA was used for the samples with examined CSs to test whether the differences in strength between the mixtures were significant. According to the table, the factor that has the greatest effect on concrete strength is the use of brick aggregate (kg·m−3). This factor makes the greatest contribution to the variability in concrete strength, accounting for 30.93% of the total variation. However, the amount of sand (kg) also plays an important role in concrete strength and explains 32.38% of the total variation. Test age (days) is also a factor affecting concrete strength, but its effect is not as great as the other two factors. It accounts for 21.96% of the total variation. It is shown that the experimental error is low at the level of 14.73. The total variance is shown as 100% in the source. When the variance percentages of all the factors specified in the source are added, the total variance reaches 100%. The P value expresses the probability that the result obtained while testing a hypothesis is due to chance. A P value of less than 0.05 in all parameters indicates that the result is significant (Table 3).

Variance components

| Source | Var | % of total | SE var | Z-value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brick as fine aggregate (kg·m−3) | 99,642,165 | 30.93% | 44,339,453 | 2,247,257 | 0.012 |

| Sand (kg) | 104,327,217 | 32.38% | 45,693,117 | 2,283,215 | 0.011 |

| Age of testing (days) | 70,740,012 | 21.96% | 47,248,174 | 1,497,201 | 0.067 |

| Error | 47,445,659 | 14.73% | 7,806,696 | 6,077,559 | 0.000 |

| Total | 322,155,053 |

Figure 17 presents a normal probability plot for the normal distribution of CS (MPa) measurements. The plot shows the relationship between the conditional residuals and the percentiles. The fact that the points are largely along a straight line indicates that the data have an approximately normal distribution. This plot is used to check whether one of the assumptions of statistical analysis, such as ANOVA, is met. The analysis supports the assumption that the data are normally distributed.

ANOVA normal probability plot.

9 Artificial neural networks

9.1 Estimation of CS

Determination of CS can be achieved using the number of hidden layers equal to the number of input variables. From references [48,49,50,51,52,53], 123 data points were collected to develop the model to predict the CS of recycled brick fine aggregate concrete. Input variables include cement, recycled brick fine aggregate, natural fine aggregate, natural coarse aggregate, water, and specimen age. The output variable is CS. The input and output variables for ANN analysis to determine the CS of the concrete are presented in Table 4.

Variables used in the ANN analysis to determine the CS (MPa)

| Cement (kg·m−3) | Filler (kg·m−3) | Brick fine aggregate (kg·m−3) | Natural fine aggregate (kg·m−3) | Natural coarse aggregate (kg·m−3) | Water (kg·m−3) | Superplastizer (kg·m−3) | Age of testing (Days) | CS (MPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 250 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 918 | 120.0 | 0 | 3.0 | 6.6 |

| Maximum | 570 | 208 | 900 | 772 | 1,530 | 325.5 | 9.12 | 90.0 | 66.8 |

| Average | 410 | 104 | 450 | 386 | 1,224 | 222.8 | 4.56 | 46.5 | 36.7 |

A hyperparameter called “epochs” determines how many times the learning algorithm will pass through the complete training dataset. Each sample in the training dataset had a chance to change the internal model parameters during an epoch.

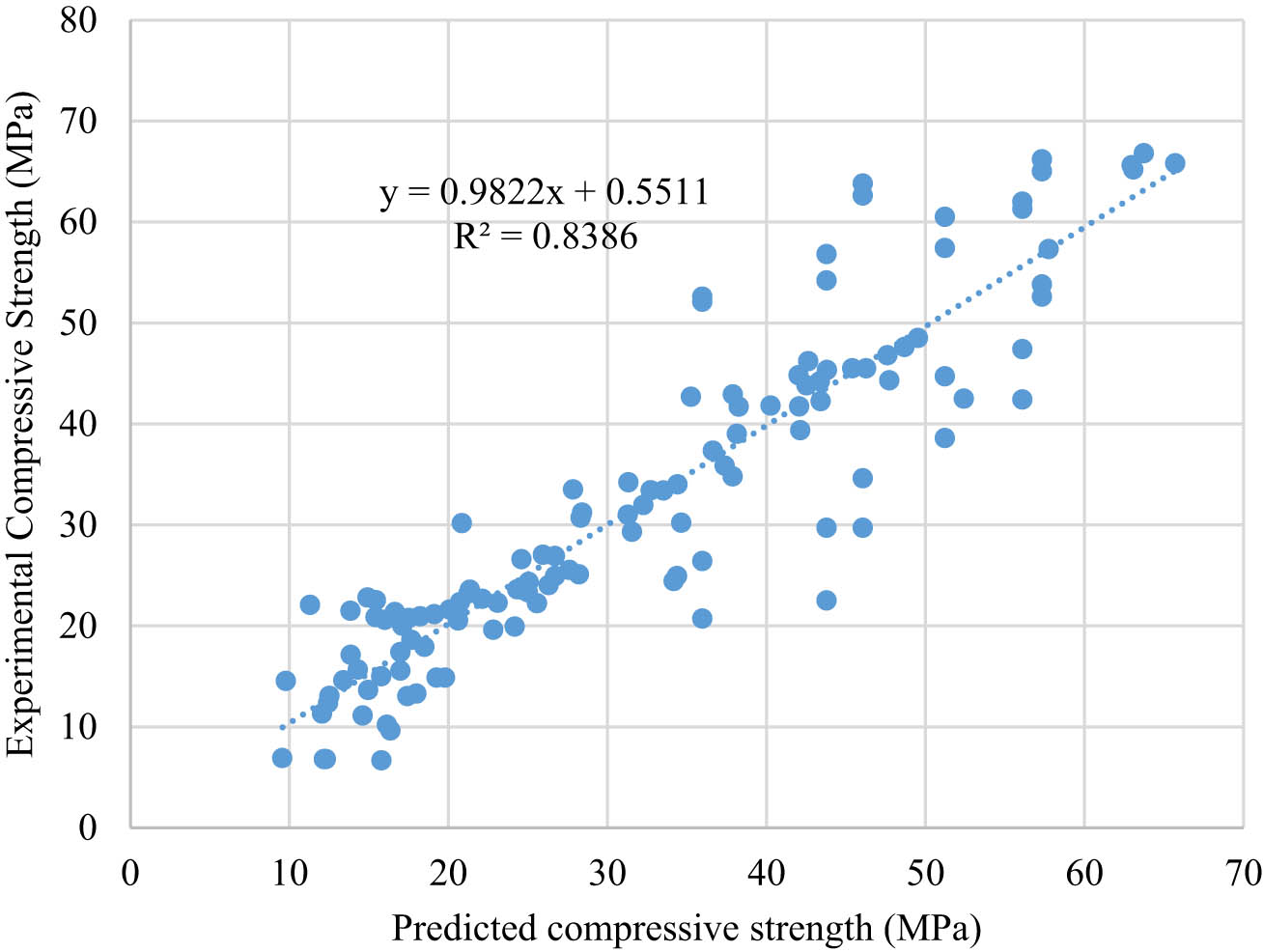

K-fold cross-validation was employed in the data from the literature [54], which were divided into five subsets of approximately equal size. In this method, the neural network was trained using four datasets comprising 70% of the observations, while the remaining 30% was set aside to evaluate the effectiveness of the model. This procedure was performed five times because the data were split such that each time, four sets were used for model development and the remaining set was used for testing, with four different combinations tried. It is advantageous that this method makes it possible to anticipate the ANN’s overall predictive capability [54]. The K-fold cross-validation (K = 10) method is used to obtain proper data models. K-fold cross-validation is a method for using more data for training and reducing the variance of the estimated performance. K-fold cross-validation was used to reduce data overfitting. The K-fold is repeated multiple times, each time using a different fold as the validation set. The coefficient of determination (R 2 and R) was used to assess the performance of the model, which is depicted in Figure 18 for K = fivefold cross-validation. The number of neurons is set to 6, equal to the number of input variables, and the number of hidden layers used is 2. The best K-fold cross-validation was determined to be K = 5, achieving the highest average R 2 value of 0.81 for both training and testing.

Predicted CS values for the ANN model.

It was found that the strongest correlation exists among the input parameters. The normalized CS value is determined by Eq. (7). Although A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6 are constant, with a normalized value for the cement (C) content (kg·m−3), recycled brick fine aggregate (R) content (kg·m−3), natural fine aggregate (NFA) content (kg·m−3), natural coarse aggregate (NCA) content (kg·m−3), water (W) content (kg·m−3), age of specimen (A) (days), and CS(CS) content (N·mm−2). The comparison of the predicted and experimental results is depicted in Figure 19.

Comparison of predicted STS values for the ANN model.

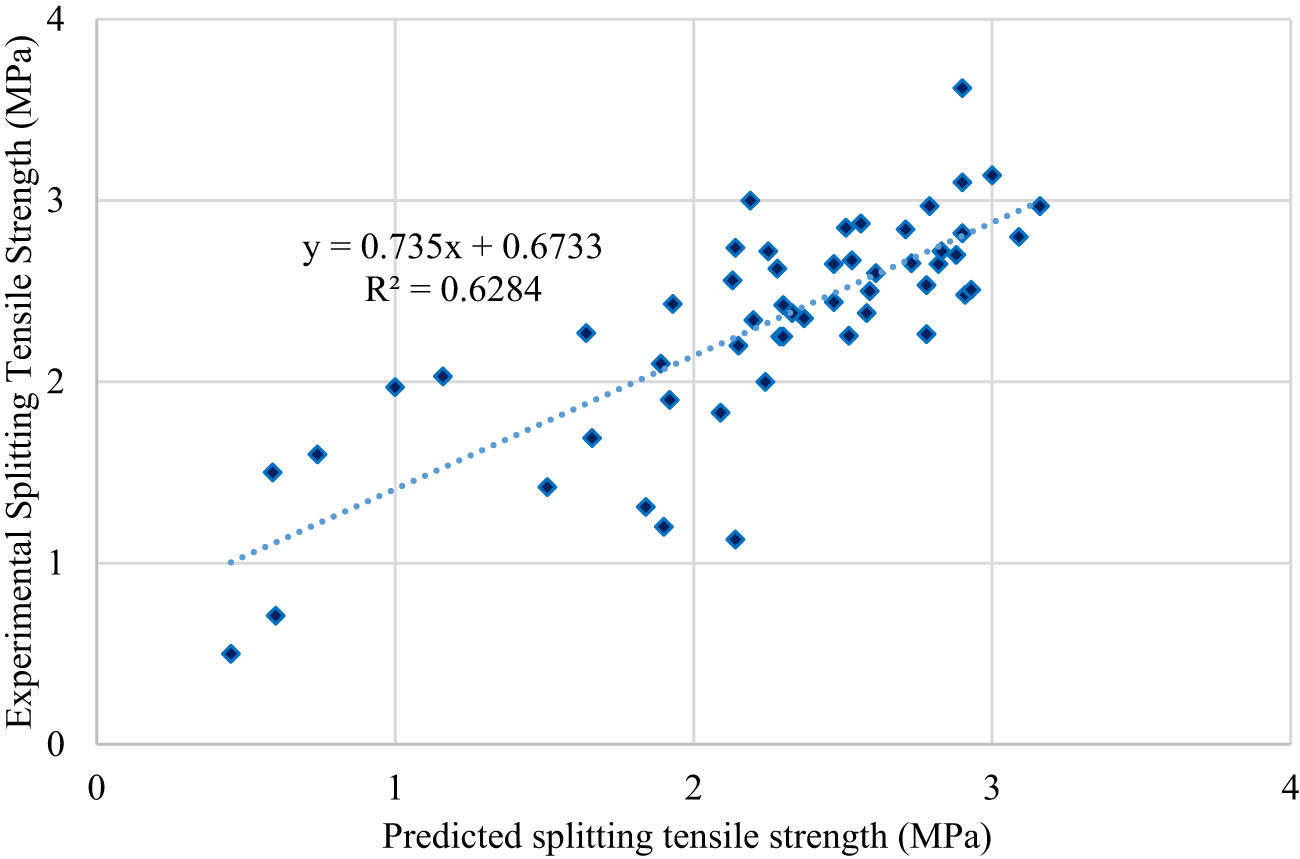

9.2 Estimation of STS

A total of 66 variables were collected from the literature [55,56,57] with seven input variables (cement, brick fine aggregate, natural fine aggregate, natural coarse aggregate, water, age of testing specimen, brick coarse aggregate) and an output variable (STS). To predict the STS from the input variables, similar to the previous section, an ANN with the LM algorithm and the TANSING function was used; ten-fold cross-validation (K = 10) was employed. The maximum, minimum, and average values used to predict the STS of are given in Table 5. Eq. (8) is used to normalize the variables used to predict STS. Epochs for the ANN model used to predict STS are depicted in Figure 19 for K-fold-cross validation with K = 6. The comparison of the predicted STS and experimental STS is depicted in Figure 20.

Variables used in the ANN analysis to determine STS

| Cement (kg·m−3) | Brick fine aggregate (kg·m−3) | Natural fine aggregate (kg·m−3) | Natural coarse aggregate (kg·m−3) | Water (kg·m−3) | Brick coarse aggregate (kg·m−3) | Age of testing (Days) | Split tensile strength (MPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 272.00 | 0 | 461.43 | 558.94 | 180.00 | 0 | 3 | 0.40 |

| Maximum | 490.00 | 153.81 | 738.00 | 1206.48 | 207.00 | 558.94 | 28.00 | 7.00 |

| Average | 400.25 | 16.78 | 636.75 | 964.05 | 194.11 | 178.15 | 20.33 | 2.41 |

Comparison of predicted FS and experimental FS.

Seventy percent of the data collected from the literature was used for training, and 30% was used for testing during the K-fold cross-validation to predict the STS. To predict STS, the coefficient of determination (R 2) was 0.92 for both training and testing data. The best K-fold cross-validation was found for the LM algorithm with K = 8.

To predict the STS of the ANN model, an equation was used, namely, weight and biases. Eq. (8) is used to predict the normalized STS.

9.3 Estimation of FS

From the literature [52,53,54,55], data were collected for about 42 variables, including seven input variables (cement, brick fine aggregate, natural fine aggregate, natural coarse aggregate, water and age of testing specimen) and one output variable (flexural tensile strength). To predict the FS from the input variable, similar to the previous section, the ANN with the LM algorithm and the TANSING function was used, and K-fold cross-validation (K = 10) was employed. The maximum, minimum, and average values used to predict the FS are presented in Table 6. Eq. (9) is used to normalize the variables used to predict the FS. Seventy percent of the data values collected from the literature were used to train the model, and 30% of the data values collected were used for the K-fold cross-validation to predict FS. To predict the FS, an R 2 value of 0.94 applied to both the training and testing data. Comparison of predicted and experimental FS are depicted in Figure 20.

Variables used in the ANN analysis to determine FS

| Cement (kg·m−3) | Brick fine aggregate (kg·m−3) | Natural fine aggregate (kg·m−3) | Natural coarse aggregate (kg·m−3) | Water (kg·m−3) | Age of testing (days) | FS (MPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 383.20 | 0 | 461.43 | 558.94 | 145.00 | 7.00 | 2.1 |

| Maximum | 487.50 | 153.81 | 636.34 | 1206.48 | 287.36 | 28.00 | 5.1 |

| Average | 417.85 | 26.37 | 590.69 | 949.36 | 213.77 | 18.67 | 3.63 |

Figure 20 shows predicted FS and experimental FS. To predict the FS of the ANN model, the prediction was made using weight and biases. Eq. (9) is used to predict the normalized FS.

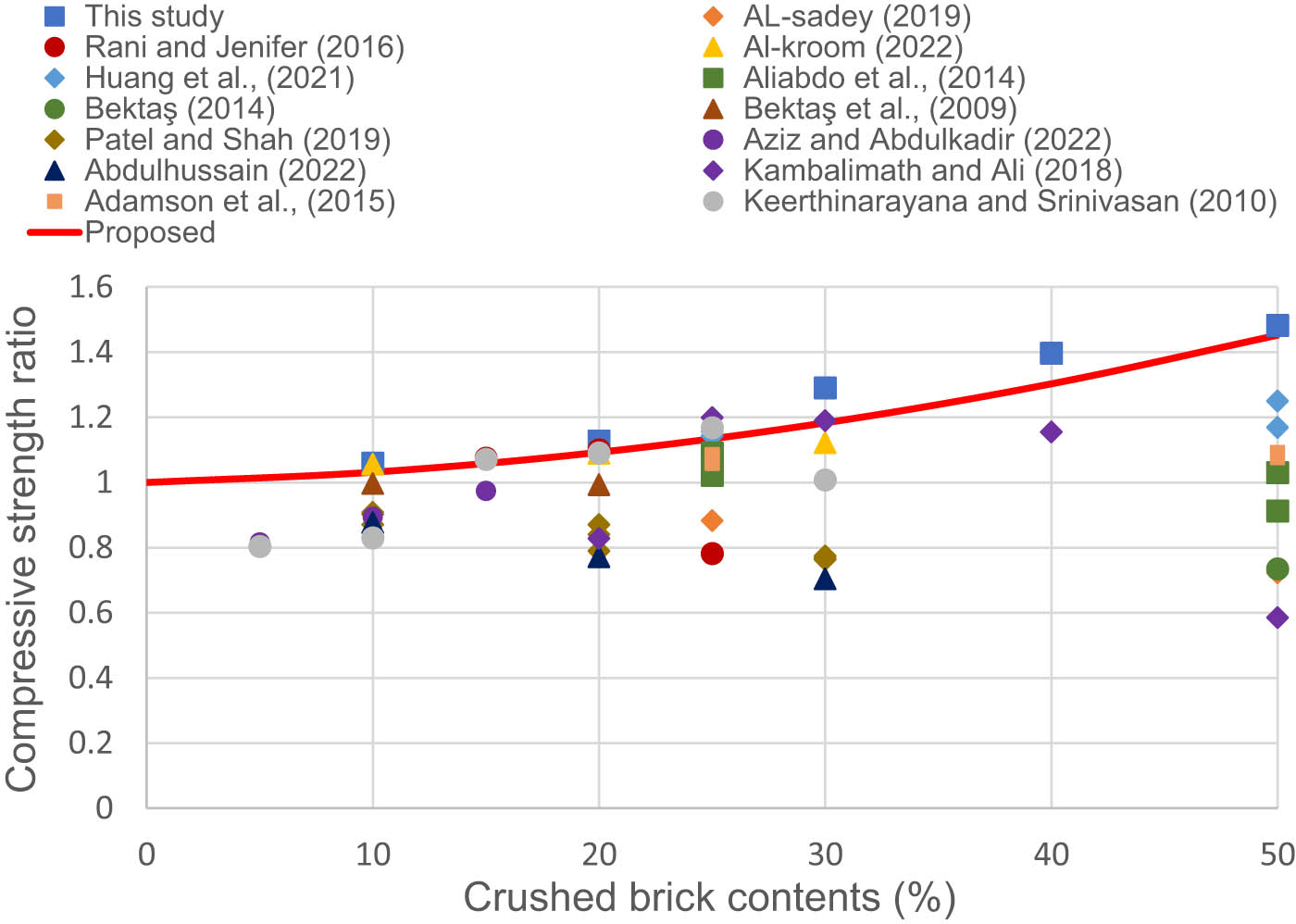

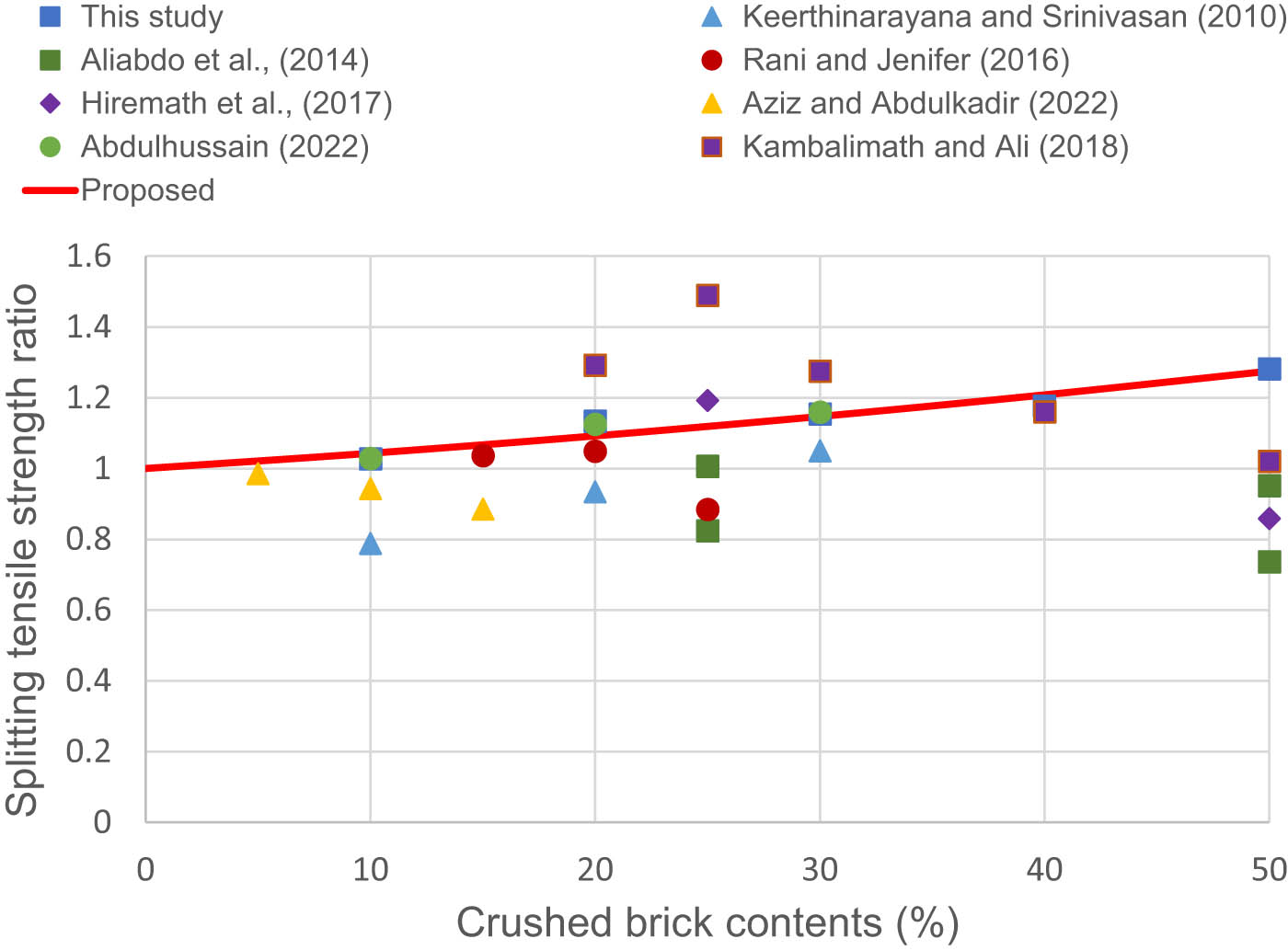

10 Simple calculations comparing current findings with previous studies

CB can be used as either an aggregate or a cement replacement in concrete. The evaluation of the CS of CB-produced concrete is shown in Figure 21. The aggregate was replaced by CBs, and the effects of this partial replacement on the engineering properties were investigated in this study. A new empirical model was developed to estimate these properties of concrete in this part of the study. To achieve this goal, the CS, FS, and STS of plain concrete and concrete produced with CB have been collected from the literature [7,11,13,26,48,55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. The strength (f) values of the concrete manufactured using CB were then normalized by the plain concrete strength (f). These normalized strength values are plotted in Figures 21–23 as a function of the crushed brick amount (CBA).

Evaluation of the CS of CB-produced concrete.

STS evaluation of concrete manufactured using CB.

Evaluation of the FS of concrete manufactured using CB.

Based on these variations, the following empirical model was developed for practical applications:

where f = strength values of concrete produced with recycled brick aggregate (f c = CS; f s = STS; f f = FS); c 1 and c 2 are coefficients given in Table 7; CBA = fire clay content (0 < CBA < 50); and f′ = strength values of the plain concrete.

The constants in Eq. (10)

| Strength values (f) | c 1 | c 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concrete produced using recycled brick aggregate | f c | 0.0017 | 0.00015 |

| f s | 0.004 | 0.00003 | |

| f f | 0.015 | −0.00011 | |

The engineering properties of concrete can be estimated as a function of the amount of fire clay used using Eq. 10.

11 Challenges to obtain recycled CBs

It has been very difficult to pick bricks for reuse from the general construction and demolition waste in developing countries since selective demolition is not yet established. Most demolitions in these areas are carried out materials sorting, leading to waste streams that are mixed and contaminated. In reality, bricks are mostly contaminated with concrete, wood, metals, and even hazardous materials, and in other words, extraction and cleaning are labor intensive and costly. In addition, it is possible that recovered bricks may have been damaged during demolition or may suffer from mortar and other residues, which could have a high impact on structural integrity for reuse. At the same time, there has been no specialized, standard equipment, and infrastructure for processing and sorting waste; therefore, large-scale recovery is impossible due to costly and inaccessible technology. Recycling in many developing countries is informal, and those resource-constrained informal workers hardly ever possess tools or equipment for proper sorting and quality checks. There is also a component of economy, whereby sorting and cleaning of bricks is costlier, while new ones will be cheaper in markets where the construction material prices are cheaper.

Although challenges present opportunities for brick recovery, such techniques can be made possible. Manual sorting and low-tech methods can already be employed in places where labor is cheap, bringing locals into the business by involving them in extracting CBs. Awareness-building campaigns, combined with policy inducements for selective demolition, can further improve the quality and quantity of recoverable bricks, as increasing material segregation even during demolition would enhance recovery. Small community-based units for brick processing are perhaps the most suitable and easiest way to create local recycling hubs, especially in rural or semi-urban areas. This will certainly help governments improve the economics of recovered bricks by introducing tax incentives or subsidies for their recycled content. Public–private partnerships can also fund and manage recycling programs with better sorting and processing. Measurement and certification of recycled bricks would also help instill confidence among construction professionals in using them. However, even though there are many challenges to face, dedicated policies, affordable infrastructure investments, and localized solutions can gradually pave the way for making the recovery of bricks from mixed demolition waste a viable and sustainable practice in developing contexts.

12 Conclusions

This study highlights the feasibility of using recycled CBs to enhance mechanical properties while reducing environmental impact. The use of recycled CBs not only reduces landfill waste but also limits the use of natural aggregate resources, both of which pertain to sustainable development. By replacing a portion of fine aggregates in concrete with waste CBs, the construction sector can encourage waste recycling and mitigate the harmful effects associated with its operations, thus contributing to global initiatives aimed at a healthy environment. For this purpose, recycled CB was replaced with fine aggregates. Exchange percentages were designated as 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50%. The examination of hardened concrete determined the CS, STS, and FS. Moreover, SEM examination was performed to compare the strength effects obtained from the investigational research. Based on this investigational consideration, the following conclusions may be drawn from this research:

While fine aggregate was replaced with recycled CB, a rise in the CS values was observed up to a certain ratio of the quantity of the waste CB, affecting its influence. It was identified that adding refuse CB at 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% of fine aggregate weight improved CS by 6, 12.8, 29.1, 39.7, and 48.3%, respectively. This was a consequence of the addition of the CB refuse. This situation can be characterized by the chemical and physical properties of concrete failure.

As the fine aggregate was replaced with recycled CB, there was a rise in the STS values corresponding to the proportion of refuse CB. When 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% of the concrete mixture was replaced by refuse CB, the STSs improved by 3.4, 13.3, 15.9, 17.9, and 28.2%, respectively. The main reason for this is that the waste CB reflects a natural pozzolan material, and the silicate oxide (SiO2) chemically reacts with Ca(OH)2 (alkaline byproducts from cement hydration).

It was discovered that the FS values of concrete combinations improved by 11.9, 23.8, 39.3, 45.2, and 48.8% when aggregates of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50% were replaced with refuse CB.

The compressive and tensile strengths of the specimens showed the greatest improvement when the mix included 50% CB as the tested component.

The empirical calculations for the CS, STS, and FS, which were established as consequences of the experimental conclusions and the results of the literature, were found to be similar, and the expected values can be easily predicted for concrete with recycled CB.

It was found from the ANN model that the predicted strength from the input parameters showed significantly high accurate results with R 2 values of 0.81, 0.92, and 0.95 for CS, STS, and FS for the K-fold cross validation value of K = 3, 8, and 8, respectively. A normalized equation to predict the values of CS, STS, and FS was developed.

A conclusion that can be drawn from the outcomes of this research is that it will be of use to designers in determining the ratios that they will employ in their designs. Furthermore, it is anticipated to facilitate the use of waste CB material within the building industry based on the data acquired.

Further research on lifecycle assessment and long-term durability is needed to maximize sustainability benefits. Such studies would take into account the in-depth analysis of the entire life cycle of the product including energy use, emissions, and costs associated with the production and utilization of CB-modified concrete. Furthermore, assessing the behavior of the CB-infused concrete under different environmental conditions and different loads will be useful in understanding the functionality of the material and its feasibility in the long run for the construction of major development projects. To better understand the structural behavior, especially in future studies, the use of CB in reinforced concrete beams and columns should be investigated depending on the usage percentages obtained from the present study.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the financial support provided for this research by the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, through Large Groups RGP2/539/46.

-

Funding information: The financial support provided for this research by the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, through Large Groups RGP2/539/46.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

[1] Nematzadeh, M., A. Arjomandi, M. Fakoor, A. Aminian, and A. Khorshidi-Mianaei. Pre-and post-heating bar-concrete bond behavior of CFRP-wrapped concrete containing polymeric aggregates and steel fibers: Experimental and theoretical study. Engineering Structures, Vol. 321, 2024, id. 118929.10.1016/j.engstruct.2024.118929Search in Google Scholar

[2] Gholampour, A., S.-A. Hosseini-Poul, S. MohammadNezhad, M. Nematzadeh, and T. Ozbakkaloglu. Effect of polypropylene and polyvinyl alcohol fibers on mechanical behavior and durability of geopolymers containing lead slag: Testing, optimization, and life cycle assessment. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 462, 2025, id. 139960.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.139960Search in Google Scholar

[3] Alharthai, M., Y. Ozkilic, M. Karalar, M. Mydin, N. Ozdoner, and A. ÇElİK. Performance of aerated lightweighted concrete using aluminum lathe and pumice under elevated temperature. Steel and Composite Structures, Vol. 51, No. 3, 2024, pp. 271–288.Search in Google Scholar

[4] Akhtar, A. and A. K. Sarmah. Construction and demolition waste generation and properties of recycled aggregate concrete: A global perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 186, 2018, pp. 262–81.10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.085Search in Google Scholar

[5] Sachdeva, N., P. Kushwaha, and D. K. Sharma. Impact of clay brick dust on durability parameters of bituminous concrete. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 80, 2023, pp. 110–115.10.1016/j.matpr.2022.10.284Search in Google Scholar

[6] Letelier, V., J. M. Ortega, P. Muñoz, E. Tarela, and G. Moriconi. Influence of waste brick powder in the mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete. Sustainability, Vol. 10, 2018, id. 1037.10.3390/su10041037Search in Google Scholar

[7] Hiremath, M., S. Sanjay, and D. Poornima. Replacement of coarse aggregate by demolished Brick waste in concrete. International Journal of Science Technology and Engineering, Vol. 4, 2017, pp. 31–36.Search in Google Scholar

[8] Ge, Z., Z. Gao, R. Sun, and L. Zheng. Mix design of concrete with recycled clay-brick-powder using the orthogonal design method. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 31, 2012, pp. 289–293.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.01.002Search in Google Scholar

[9] Ge, Z., Y. Wang, R. Sun, X. Wu, and Y. Guan. Influence of ground waste clay brick on properties of fresh and hardened concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 98, 2015, pp. 128–136.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.08.100Search in Google Scholar

[10] O’Farrell, M., S. Wild, and B. B. Sabir. Pore size distribution and compressive strength of waste clay brick mortar. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 23, 2001, pp. 81–91.10.1016/S0958-9465(00)00070-6Search in Google Scholar

[11] Dang, J., J. Zhao, W. Hu, Z. Du, and D. Gao. Properties of mortar with waste clay bricks as fine aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 166, 2018, pp. 898–907.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.01.109Search in Google Scholar

[12] Kumavat, H. R. An experimental investigation of mechanical properties in clay brick masonry by partial replacement of fine aggregate with clay brick waste. Journal of The Institution of Engineers (India): Series A, Vol. 97, 2016, pp. 199–204.10.1007/s40030-016-0178-7Search in Google Scholar

[13] Yang, J., Q. Du, and Y. Bao. Concrete with recycled concrete aggregate and crushed clay bricks. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 25, 2011, pp. 1935–1945.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.11.063Search in Google Scholar

[14] Khatib, J. M. Properties of concrete incorporating fine recycled aggregate. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 35, 2005, pp. 763–769.10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.06.017Search in Google Scholar

[15] Shaaban, I. G., J. P. Rizzuto, A. El-Nemr, L. Bohan, H. Ahmed, and H. Tindyebwa. Mechanical properties and air permeability of concrete containing waste tires extracts. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 33, 2021, id. 04020472.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0003588Search in Google Scholar

[16] Mohammed, T. U., A. Hasnat, M. A. Awal, and S. Z. Bosunia. Recycling of brick aggregate concrete as coarse aggregate. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 27, 2015, id. B4014005.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001043Search in Google Scholar

[17] Schackow, A., D. Stringari, L. Senff, S. L. Correia, and A. M. Segadães. Influence of fired clay brick waste additions on the durability of mortars. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 62, 2015, pp. 82–89.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2015.04.019Search in Google Scholar

[18] Bhatta, N., A. Adhikari, A. Ghimire, N. Bhandari, A. Subedi, and K. Sahani. Comparing crushed brick as coarse aggregate substitute in concrete: experimental vs numerical study. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering, Vol. 48, 2024, pp. 4255–74.10.1007/s40996-024-01407-8Search in Google Scholar

[19] Kumar, K. and R. Rana. Innovative concrete materials: utilizing crushed bricks for aggregate replacement. International Journal of Emerging Trends in Research, Vol. 6, No. 2, 2025, pp. 11–20.Search in Google Scholar

[20] Zhao, J., Y. Li, X. Li, and B. Lei. Properties of waste brick powder-based artificial fine aggregate and its application in concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 98, 2024, id. 111466.10.1016/j.jobe.2024.111466Search in Google Scholar

[21] Rocha, J. H. A., B. M. M. Ruiz, and R. D. Toledo Filho. Evaluating the use of recycled brick powder as a partial replacement for portland cement in concrete. IngenIería e InvestIgacIón, Vol. 44, 2024, id. 4.10.15446/ing.investig.107462Search in Google Scholar

[22] Sweety Poornima Rau, M. and Y. M. Manjunath. An experimental study on mechanical behaviour of concrete by partial replacement of sand with brick fines. Australian Journal of Structural Engineering, Vol. 25, 2024, pp. 194–211.10.1080/13287982.2023.2269633Search in Google Scholar

[23] Astm, C. Standard test method for slump of hydraulic-cement concrete, ASTM International West Conshohocken, PA, 2012.Search in Google Scholar

[24] Sabetifar, H., M. Fakhari, M. Nikofar, and M. Nematzadeh. Comprehensive study of eccentrically loaded CFRP-confined RC columns maximum capacity: prediction via ANN and GEP. Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and Design, Vol. 8, 2025, id. 158.10.1007/s41939-025-00738-xSearch in Google Scholar

[25] Yildizel, S. A., Y. O. Özkılıç, and A. Yavuz. Optimization of waste tyre steel fiber and rubber added foam concretes using Taguchi method and artificial neural networks. Structures, Vol. 61, 2024, id. 106098.10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106098Search in Google Scholar

[26] Adamson, M., A. Razmjoo, and A. Poursaee. Durability of concrete incorporating crushed brick as coarse aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 94, 2015, pp. 426–432.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.07.056Search in Google Scholar

[27] Janković, K., D. Bojović, D. Nikolić, L. Lončar, and Z. Romakov. Frost resistance of concrete with crushed brick as aggregate. Facta universitatis-series: Architecture and Civil Engineering, Vol. 8, 2010, pp. 155–162.10.2298/FUACE1002155JSearch in Google Scholar

[28] Hansen, T. C. Recycling of demolished concrete and masonry, CRC press, London, 1992.10.1201/9781482267075Search in Google Scholar

[29] Khaloo, A. R. Properties of concrete using crushed clinker brick as coarse aggregate. Materials Journal, Vol. 91, 1994, pp. 401–407.10.14359/4058Search in Google Scholar

[30] Chakradhara Rao, M. Influence of brick dust, stone dust, and recycled fine aggregate on properties of natural and recycled aggregate concrete. Structural Concrete, Vol. 22, 2021, pp. E105–E120.10.1002/suco.202000103Search in Google Scholar

[31] Kasinikota, P. and D. D. Tripura. Evaluation of compressed stabilized earth block properties using crushed brick waste. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 280, 2021, id. 122520.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122520Search in Google Scholar

[32] Silva, J., J. De Brito, and R. Veiga. Recycled red-clay ceramic construction and demolition waste for mortars production. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 22, 2010, pp. 236–244.10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2010)22:3(236)Search in Google Scholar

[33] Ayaz Khan, M. N., N. Liaqat, I. Ahmed, A. Basit, M. Umar, and M. A. Khan. Effect of brick dust on strength and workability of concrete, IOP Publishing, p. 012005.10.1088/1757-899X/414/1/012005Search in Google Scholar

[34] Resin, R., A. Alwared, and S. Al-Hubboubi. Utilization of brick waste as pozzolanic material in concrete mix, EDP Sciences, Sharm el-Shiekh, Egypt, p. 02006.10.1051/matecconf/201816202006Search in Google Scholar

[35] Mansoor, S. S., S. M. Hama, and D. N. Hamdullah. Effectiveness of replacing cement partially with waste brick powder in mortar. Journal of King Saud University-Engineering Sciences, Vol. 36, 2024, pp. 524–532.10.1016/j.jksues.2022.01.004Search in Google Scholar

[36] Wang, R., Q. Zhang, and Y. Li. Deterioration of concrete under the coupling effects of freeze–thaw cycles and other actions: A review. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 319, 2022, id. id. 126045.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.126045Search in Google Scholar

[37] Afflerbach, S., C. Pritzel, P. Hartwich, M. S. Killian, and W. Krumm. Effects of thermal treatment on the mechanical properties, microstructure and phase composition of an Ettringite rich cement. CEMENT, Vol. 11, 2023, id. 100058.10.1016/j.cement.2023.100058Search in Google Scholar

[38] Gu, Y. Experimental pore scale analysis and mechanical modeling of cement-based materials submitted to delayed ettringite formation and external sulfate attacks, Materials and structures in mechanics, Université Paris-Est, 2018.Search in Google Scholar

[39] Qoku, E., T. A. Bier, and T. Westphal. Phase assemblage in ettringite-forming cement pastes: A X-ray diffraction and thermal analysis characterization. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 12, 2017, pp. 37–50.10.1016/j.jobe.2017.05.005Search in Google Scholar

[40] Kaish ABMAOdimegwu, T. C., I. Zakaria, and M. M. Abood. Effects of different industrial waste materials as partial replacement of fine aggregate on strength and microstructure properties of concrete. Journal of Building Engineering, Vol. 35, 2021, id. 102092.10.1016/j.jobe.2020.102092Search in Google Scholar

[41] Thomas, C., J. de Brito, A. Cimentada, and J. A. Sainz-Aja. Macro- and micro- properties of multi-recycled aggregate concrete. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 245, 2020, id. 118843.10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118843Search in Google Scholar

[42] Zhang, K., J. Zhou, and Z. Yin. Experimental study on mechanical properties and pore structure deterioration of concrete under freeze–thaw cycles. Materials, Vol. 14, 2021, id. 6568.10.3390/ma14216568Search in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Tam, V. W. Y., X. F. Gao, and C. M. Tam. Microstructural analysis of recycled aggregate concrete produced from two-stage mixing approach. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 35, 2005, pp. 1195–1203.10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.10.025Search in Google Scholar

[44] Gharieb, M., W. Ramadan, and W. M. Abd El-Gawad. Outstanding effect of cost-saving heavy nano-ferrites on the physico-mechanical properties, morphology, and gamma radiation shielding of hardened cement pastes. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 409, 2023, id. 134064.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134064Search in Google Scholar

[45] Mohr, B. J., M. S. Islam, and J. France-Mensah. Leachate testing for delayed ettringite formation potential in cementitious systems. CEMENT, Vol. 12, 2023, id. 100060.10.1016/j.cement.2023.100060Search in Google Scholar

[46] Asamoto, S., K. Murano, I. Kurashige, and A. Nanayakkara. Effect of carbonate ions on delayed ettringite formation. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 147, 2017, pp. 221–226.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.04.107Search in Google Scholar

[47] Hou, D., H. Ma, and Z. Li. Morphology of calcium silicate hydrate (CSH) gel: a molecular dynamic study. Advances in Cement Research, Vol. 27, 2015, pp. 135–46.10.1680/adcr.13.00079Search in Google Scholar

[48] Aliabdo, A. A., A.-E. M. Abd-Elmoaty, and H. H. Hassan. Utilization of crushed clay brick in concrete industry. Alexandria Engineering Journal, Vol. 53, 2014, pp. 151–168.10.1016/j.aej.2013.12.003Search in Google Scholar

[49] Vieira, T., A. Alves, J. de Brito, J. R. Correia, and R. V. Silva. Durability-related performance of concrete containing fine recycled aggregates from crushed bricks and sanitary ware. Materials & Design, Vol. 90, 2016, pp. 767–776.10.1016/j.matdes.2015.11.023Search in Google Scholar

[50] Baradaran-Nasiri, A. and M. Nematzadeh. The effect of elevated temperatures on the mechanical properties of concrete with fine recycled refractory brick aggregate and aluminate cement. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 147, 2017, pp. 865–75.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.04.138Search in Google Scholar

[51] Nematzadeh, M., J. Dashti, and B. Ganjavi. Optimizing compressive behavior of concrete containing fine recycled refractory brick aggregate together with calcium aluminate cement and polyvinyl alcohol fibers exposed to acidic environment. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 164, 2018, pp. 837–849.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.12.230Search in Google Scholar

[52] Debieb, F. and S. Kenai. The use of coarse and fine crushed bricks as aggregate in concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 22, 2008, pp. 886–893.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.12.013Search in Google Scholar

[53] Miličević, I., D. Bjegović, and R. Siddique. Experimental research of concrete floor blocks with crushed bricks and tiles aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 94, 2015, pp. 775–783.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.07.163Search in Google Scholar

[54] Paneiro, G. and M. Rafael. Artificial neural network with a cross-validation approach to blast-induced ground vibration propagation modeling. Underground Space, Vol. 6, 2021, pp. 281–289.10.1016/j.undsp.2020.03.002Search in Google Scholar

[55] Kambalimath, N. C. and M. Ali. An experimental study on strength of concrete with partial replacement of fine aggregate with recycled crushed brick aggregate and quarry dust. IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering (IOSR-JMCE) e-ISSN, Vol. 15, 2018, pp. 52–60.Search in Google Scholar

[56] Rani, M. U. and J. M. Jenifer. An experimental study on partial replacement of sand with crushed brick in concrete. International Journal of Science Technology & Engineering (IJSTE), Vol. 2, 2016, pp. 316–322.Search in Google Scholar

[57] Zhang, S. and L. Zong. Properties of concrete made with recycled coarse aggregate from waste brick. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy, Vol. 33, 2014, pp. 1283–1289.10.1002/ep.11880Search in Google Scholar

[58] Bektaş, F. Alkali reactivity of crushed clay brick aggregate. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 52, 2014, pp. 79–85.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.11.014Search in Google Scholar

[59] Alsadey, S. Properties of concrete using crushed brick as coarse aggregate. International Journal of Advances in Mechanical and Civil Engineering, Vol. 6, 2019, pp. 44–47.Search in Google Scholar

[60] Pinchi, S., J. Ramírez, J. Rodríguez, and C. Eyzaguirre. Use of recycled broken bricks as Partial Replacement Coarse Aggregate for the Manufacturing of Sustainable Concrete, 1 edn, IOP Publishing, 2019 the 7th International Conference on Mechanical Engineering, Materials Science and Civil Engineering, Sanya, China, 2019, p. 012039.10.1088/1757-899X/758/1/012039Search in Google Scholar

[61] Bektas, F., K. Wang, and H. Ceylan. Effects of crushed clay brick aggregate on mortar durability. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 23, 2009, pp. 1909–1914.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.09.006Search in Google Scholar

[62] Shah, R. and N. Patel. Experimental exploration on crushed bricks considering partial alternate as coarse aggregate for concrete. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research (JETIR), Vol. 6, 2019, pp. 237–240.Search in Google Scholar

[63] Al-kroom, H., M. M. Atyia, M. G. Mahdy, and M. Abd Elrahman. The effect of finely-grinded crushed brick powder on physical and microstructural characteristics of lightweight concrete, Vol. 12, 2022, id. 159.10.3390/min12020159Search in Google Scholar

[64] Huang, Q., X. Zhu, G. Xiong, C. Wang, D. Liu, and L. Zhao. Recycling of crushed waste clay brick as aggregates in cement mortars: An approach from macro- and micro-scale investigation. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 274, 2021, id. 122068.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.122068Search in Google Scholar

[65] Aziz, P. L. and M. R. Abdulkadir. Mechanical properties and flexural strength of reinforced concrete beams containing waste material as partial replacement for coarse aggregates. International Journal of Concrete Structures and Materials, Vol. 16, 2022, id. 56.10.1186/s40069-022-00550-8Search in Google Scholar

[66] Abdulhussain, S. T. Evaluation of Compressive and tensile strength of self‐curing concrete by adding crushed bricks as additive material. Journal of Engineering, Vol. 2022, 2022, id. 5410964.10.1155/2022/5410964Search in Google Scholar

[67] Keerthinarayana, S., & Srinivasan, R. Study on strength and durability of concrete by partial replacement of fine aggregate using crushed spent fire bricks. Buletinul Institutului Politehnic din lasi. Sectia Constructii, Arhitectura, Vol. 56, No. 2, 2010, id. 51.Search in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Articles in the same Issue

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Towards sustainable concrete pavements: a critical review on fly ash as a supplementary cementitious material

- Optimizing rice husk ash for ultra-high-performance concrete: a comprehensive review of mechanical properties, durability, and environmental benefits

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches