Abstract

Due to the impact on the environment, the construction industry is striving to comply with the EU Green Deal in terms of reducing the natural resources used to produce cement. One of the strategies is the use of industrial by-products such as cement substitutes. In this work, the autogenous shrinkage of cement pastes with red mud (RM), limestone (LS), silica fume (SF), and calcined clay (CC) was investigated. The materials used originate from the same region in South-Eastern Europe. Five different mixtures were tested, in which the replacement level for cement varies up to 20% for RM and up to 10% for SF, LS, and CC. In addition, the behavior in the fresh state was evaluated by testing the workability and setting time and in the hardened state by testing the compressive and flexural strength. The results show that as the amount of supplementary cementitious material (SCM) increases, the deformation of autogenous shrinkage gradually increases. Normalized to the amount of cement, the compressive strength showed higher efficiency of the cement when SCMs were added. The results suggest that the SCMs used, with their fine particle size, provide additional nucleation sites for hydration products, resulting in higher efficiency of the cement in achieving compressive strength and higher autogenous shrinkage when SCMs are present.

1 Introduction

The demand for cement has remained relatively unchanged in recent years, with global production reaching 4.1 billion tons in 2022 [1]. The production and consumption of cement are responsible for 96% of the total carbon footprint of concrete and 85% of installed energy [2]. In view of the EU’s commitment under the Green Deal [3] to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, the cement industry is under great pressure to urgently reduce its environmental impact. In most strategies and roadmaps [4], the additional reduction of the clinker factor of cement using supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) remains one of the fixed targets for 2030. Commonly used SCMs are still fly ash and granulated blast furnace slag, which are obtained as by-products from other energy and steel manufacturing sectors. However, the energy and manufacturing sectors are also under pressure to reduce their environmental impact (e.g., coal phase-out and clean production strategies), leading to a reduction in the availability of these classical SCMs. Therefore, the focus of cement research and industry is on other materials and by-products that are available in large quantities in different regions worldwide, such as limestone (LS), clay, and red mud (red mud) [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

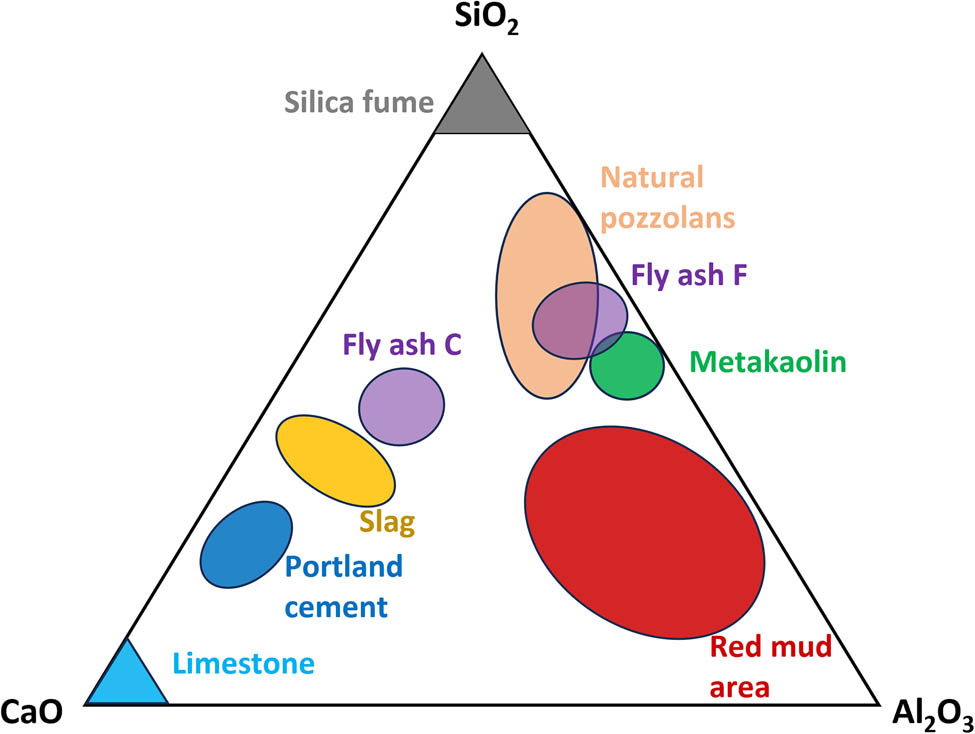

RM is produced as a by-product during alumina production from the bauxite ore [16]. The dense reddish-brown mass is an aggregate of iron oxides (hematite), from which the red color originates, but also of silicon dioxide, calcium carbonate/aluminate, sodium aluminosilicates, and sodium hydroxide [17]. During the production of alumina by the Bayer process, 55–65% of the RM is obtained from the bauxite ore [18]. The chemical composition of RM can vary considerably depending on the origin of the bauxite ore used for alumina production. Figure 1 (ternary diagram) shows the mineral composition of RM based on previous studies [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] in comparison to Portland cement and conventional SCMs [29]. A low CaO content and a variable Al2O3–SiO2 content can be seen.

Ternary diagram of main oxide distribution (SiO2–Al2O3–CaO) for Portland cement and common SCMs compared to RM.

RM is characterized by fine particle size, relatively high alkalinity, but a high Fe2O3 content [10], which limits its potential. Several studies have investigated RM for application in the cement industry [30,31,32]. Ribeiro et al. [20] concluded that RM does not exhibit pozzolanic properties like some common SCMs, and higher proportions of RM can be used as a cement replacement only for non-structural elements. In contrast, the work of Sawant et al. [33] and Venkatesh et al. [11] found an increase in compressive strength with an RM content of up to 15%. Some studies have reported that the addition of RM has a beneficial effect on the durability properties of concrete, e.g., reduction in chloride diffusion [34], reduction in the corrosion potential of reinforcing bars [35], and unchanged surface resistance [36]. In the literature, it has been found that RM significantly impairs the workability of concrete and increases the need for additional water [37]. The rheological properties of concrete with added RM are still being researched. Since autogenous shrinkage of hardened cement paste is an important cause of premature cracking in concrete, further experimental studies are required to understand and quantify the autogenous shrinkage of hardened cement paste with RM. While the addition of RM [12] leads to an increase in autogenous shrinkage but a decrease in drying shrinkage, Liu and Poon’s studies on self-compacting mortar [38] indicate the opposite, namely a decrease in autogenous shrinkage and an increase in drying shrinkage of mixtures with the addition of RM. Also, concrete with a high replacement cement level may be at higher risk of plastic shrinkage [39]. Finely ground fillers and SCMs result in smaller pores and a steeper rise in capillary pressure during drying at early age. At the same time, they develop a slower gain in stiffness, hence higher deformation under capillary pressure and bigger risk of cracking [39]. Untreated RM alone as the SCM shows inconsistent behavior and reduces concrete properties in most cases [40]. Therefore, researchers tend to use RM together with other SCMs [15,41,42,43,44,45]. Mixtures of RM with by-products, industrial waste, and materials generated in the vicinity of RM production have the greatest application potential from an LCA perspective. Worryingly, the level of cement substitution with common SCMs in the last few years has fallen back, mostly due to their limited availability and the limit in their reactivity [46]. Therefore, introducing SCMs with alumina can lead to increased LS reaction and increased cement substitutions. Unfortunately, materials with high alkali content lead to negative influence on later strength [46], which needs to be further studied.

In this study, the early age properties of cement paste containing RM, LS, silica fume (SF), and calcined clay (CC), all from sources in the same region (South-East EU), were investigated. All these materials are classified as industrial waste and are by-products of industrial production. The aim of this study is to evaluate the synergistic effects of the SCMs used on the autogenous shrinkage of cement paste. In addition, the behavior in the fresh state was evaluated by testing the workability and setting time and in the hardened state by testing the compressive and flexural strength. It is important to note that these materials were not previously studied as SCMs in regard to their effect on early age behavior of cement paste. Furthermore, the substitution levels for the selected materials are at the upper limit so that the maximum possible synergistic effect of these materials is achieved.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

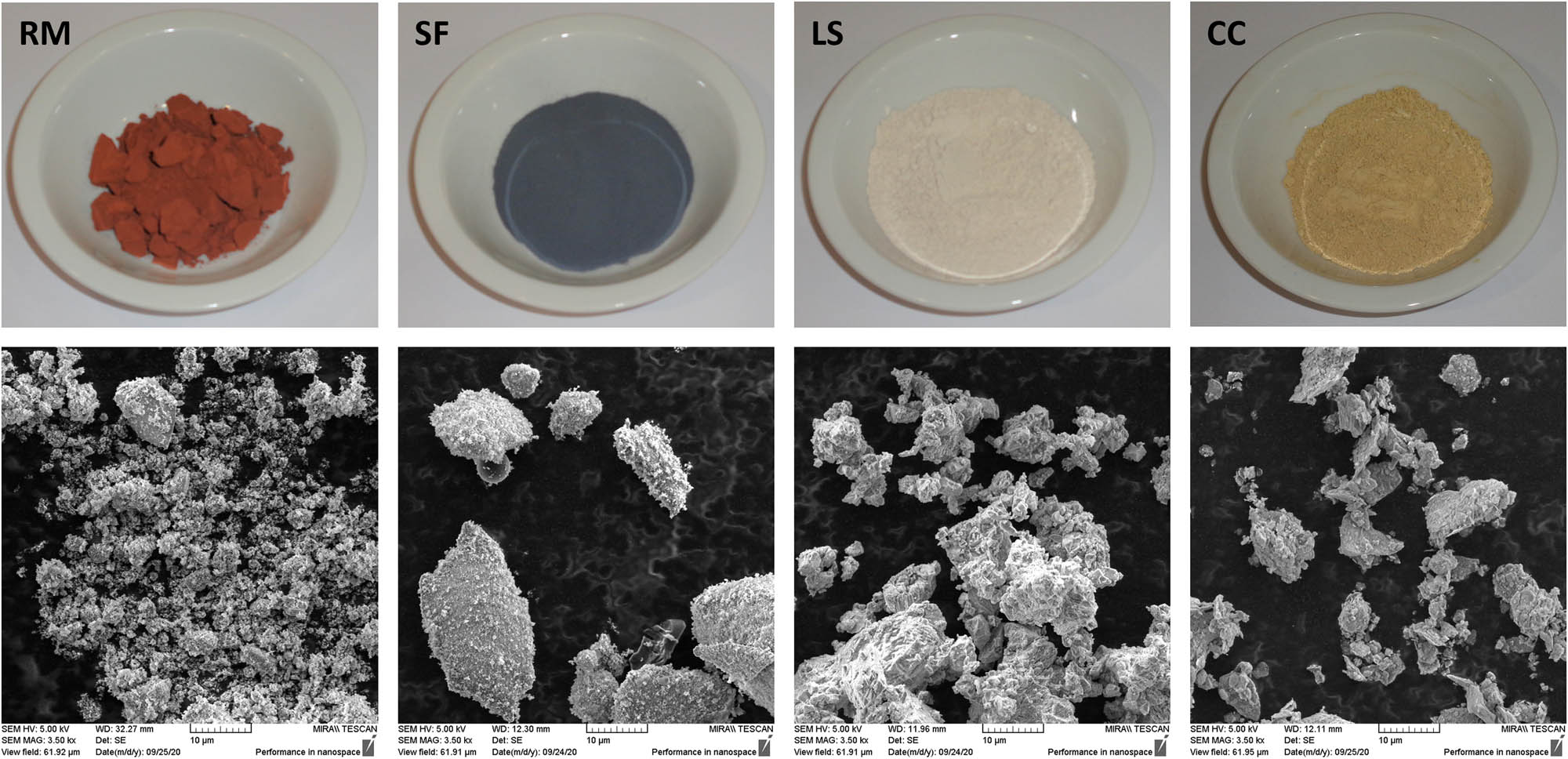

All mixtures produced in the study were based on the cement CEM I 42.5R, which contains 95–100% Portland clinker with only 0–5% by-products. The cement has very high early strength, fast-setting time, and high heat of hydration. Standardized quartz sand grains of 0–4 mm size and tap water were used to produce the mortars. RM, LS, SF, and CC were used as a partial substitute for cement in the mixtures. LS was obtained as quarry dust from Croatia; SF and RM were obtained from Bosnia and Herzegovina; and CC was from Serbia. All materials were used as they were delivered, with the exception of the clay, which was calcined at 800°C for 1 . Figure 2 shows pictures and SEM images of all materials. The chemical analysis of cement and SCMs is shown in Table 1. The analysis was performed by X-ray fluorescence.

Photographs and SEM images of used SCMs: RM, SF, LS, and CC.

Properties of cement and SCMs used in the study

| Oxides | CEM I | RM | LS | SF | Clay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 (%) | 19.32 | 21.95 | 20.21 | 92.02 | 61.77 |

| Al2O3 (%) | 4.86 | 16.94 | 4.32 | 1.68 | 28.72 |

| Fe2O3 (%) | 2.94 | 37.88 | 1.43 | 0.45 | 3.03 |

| TiO2 (%) | — | 4.13 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.87 |

| CaO (%) | 64.04 | 9.96 | 71.59 | 3.06 | 2.39 |

| MgO (%) | 1.83 | 0.61 | 1.69 | 0.77 | 0.68 |

| SO3 (%) | 2.75 | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.22 |

| MnO (%) | — | 0.43 | 0.03 | 0.03 | <0.01 |

| Na2O (%) | 0.23 | 7.23 | <0.01 | 0.21 | <0.01 |

| K2O (%) | 0.82 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 1.11 | 2.30 |

| P2O5 (%) | — | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.36 | <0.01 |

| Na2Oeq (%) | 0.77 | 7.35 | <0.01 | 0.94 | 1.52 |

| Sum pozz. (%) | — | 76.8 | 26 | 94.1 | 93.5 |

| d 50 (µm) | 9.95 | 0.39 | 18 | 0.3 | 6.4 |

| Spec. gravity (g·cm−3) | 3.098 | 3.250 | 2.700 | 2.130 | 2.260 |

| Amorphous phase (%) | — | 31.8 | 8.3 | 97.2 | 8.2 |

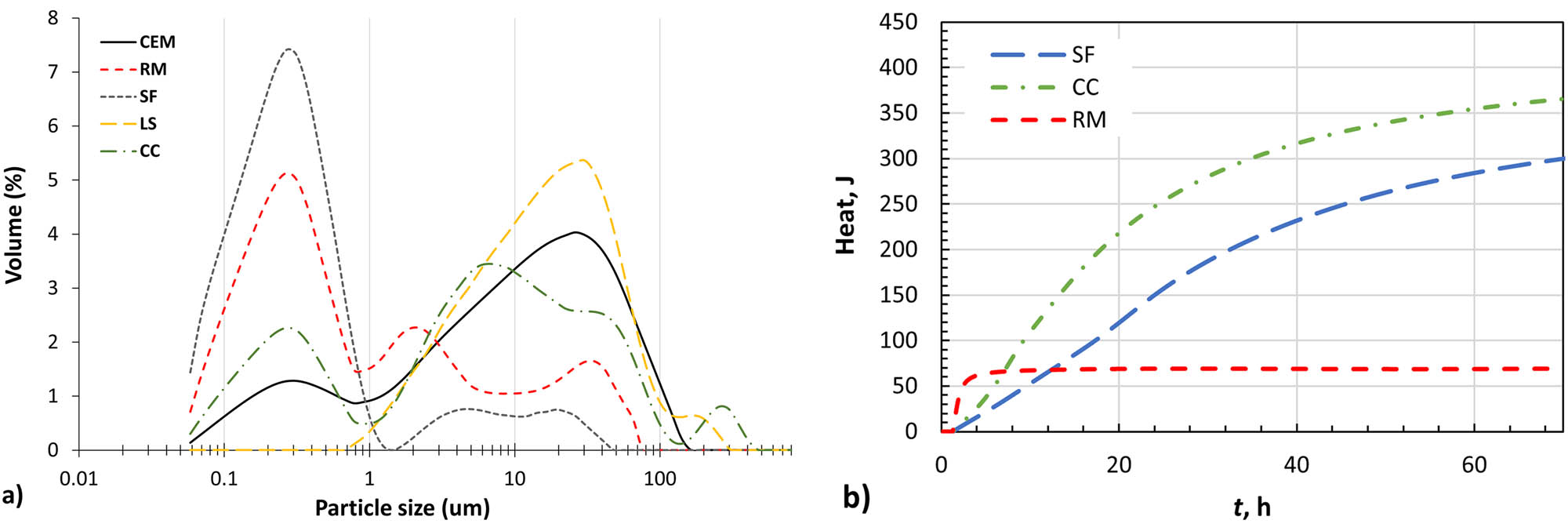

RM is rich in iron and alumina oxide, and a high sodium oxide content is also reported. LS is largely composed of CaO (>70%), and SF consists of 92% pure SiO2, while other components are negligible. CC is rich in silica and alumina, with a small proportion of other oxides and a kaolinite content of 43%. The sum of pozzolanic oxides (silicon, alumina, and iron) is above 70% for all SCMs except for LS [47]. In addition, the sodium oxide equivalent (Na2Oeq) is below 5% for all samples except RM. According to ASTM C618 [48], all SCM samples have an SO3 content of less than 5% and a calcium oxide content of less than 18%, with the exception of LS. The difference in particle size can be seen from the specific surface area. The SF particles have the highest fineness, and RM has about 2.5 times finer particles than the other materials used. Figure 3 shows the particle size distribution of used materials, given in volume fractions determined with a laser diffraction device (Mastersizer 2000). Most of the RM and SF particles are in the range of 0.10–1 µm. CC and cement have a relatively wide particle distribution, with most particles in the 1–100 µm range. LS has most particles in the 1–100 µm range. The reactivity of SCM, as determined by the R3 test, is shown in Figure 3 (right). CC exhibits the highest heat, indicating the highest rate of reaction. RM reacts very fast in the first period, while later acts fully inert.

(a) Particle size distribution and (b) heat evolution during the R3 test (right).

2.2 Sample preparation

Five different mixtures were designed and prepared according to the EN 480-1 standard (Table 2). The reference mix (CEM) was prepared with a cement content of 100%, and in the other four mixes the cement content was varied, i.e., the content of SCMs was varied. Thus, cement and other SCMs were considered as binders. All mixtures were prepared with a water to binder ratio of 0.5, the same amount of sand of 1,350 g, and a binder content of 450 g. The reference mix (CEM) is a classic cement mortar, i.e., cement, quartz sand, and water. The second mixture (CEM + RM) was prepared with a partial cement replacement of 20% by RM. In the third mixture (CEM + RM + LS), 20% RM and 10% LS were used. The mixture (CEM + RM + SF) contained 20% RM and 10% SF as a substitute for cement. Finally, the fifth mixture (CEM + RM + CC + LS) contained 20% RM, 10% CC, and 5% LS. The RM content was kept constant, while the content of the other SCMs varied.

Labelling and mix proportions of binder in different mixtures tested

| Mixture | Mass within the binder (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEM | RM | LS | SF | CC | |

| CEM | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CEM + RM | 80 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CEM + RM + LS | 70 | 20 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| CEM + RM + SF | 70 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| CEM + RM + CC + LS | 65 | 20 | 5 | 0 | 10 |

2.3 Methods

The mixing procedure was in accordance with EN 196-1. The mixtures were prepared in an automatic mortar mixer. First, dry components were added, mixed for 90 s to obtain a uniform mass. Then, the water was added, and the mixing continued to complete the mixing process. After the mixing procedure, the workability was determined. The workability of the mortar was determined by a flow table test in accordance with EN 1015-3. The spread was measured in two directions perpendicular to each other. Average results were calculated, which represent the results for workability.

The setting time (initial and final setting) was determined using a ToniSET Two – automatic Vicat needle. The mixture was poured in a mold, which was then placed in the apparatus. From that point, the test procedure was fully automatic, where the self-cleaning needle penetrated into the mixture in pre-defined time frames, and the depth of penetration as well as the test time were recorded until the end of test.

The auto-shrink-corrugated tube method with a digital dilatometer was used to test the autogenous shrinkage of cement paste [49]. This method was used for the linear measurement of autogenous shrinkage of cement-based materials. Primarily, this method is intended for measuring the deformation of cement pastes or mortars with a maximum grain size of 1 mm. The cement paste was poured into corrugated plastic tubes. The tube only allowed measurement in one direction as it is very stiff in the radial direction. The displacement was measured at the ends of the tubes. The measurement can be taken at both ends or only at one end, with the other end being fixed in a frame [50,51]. For this study, the measurement was carried out by fixing one end, and the displacement was measured at the other end (Figure 4).

Autogenous shrinkage test by the auto-shrink-corrugated tube method.

The compressive and flexural strength were determined on three 4 × 4 × 16 cm prisms per mixture after 7 and 28 days of curing according to HRN EN 196-1. After casting, molds were covered with a plastic film and kept for a minimum of 24 h to prevent water evaporation. After a minimum of 24 h, prisms were demolded, and the specimens were placed in a curing chamber at 20 ± 2°C and 95% relative humidity, where they were kept until testing. The compressive and flexural strength were tested on cement mortars prepared with the same binder compositions, according to the standard EN 196-1. Flexural strength was tested with a three-point flexural test device, and the results represent the average of three tested samples. Compressive strength was tested on split samples, thus results are represented as an average of six test results.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Workability and setting time

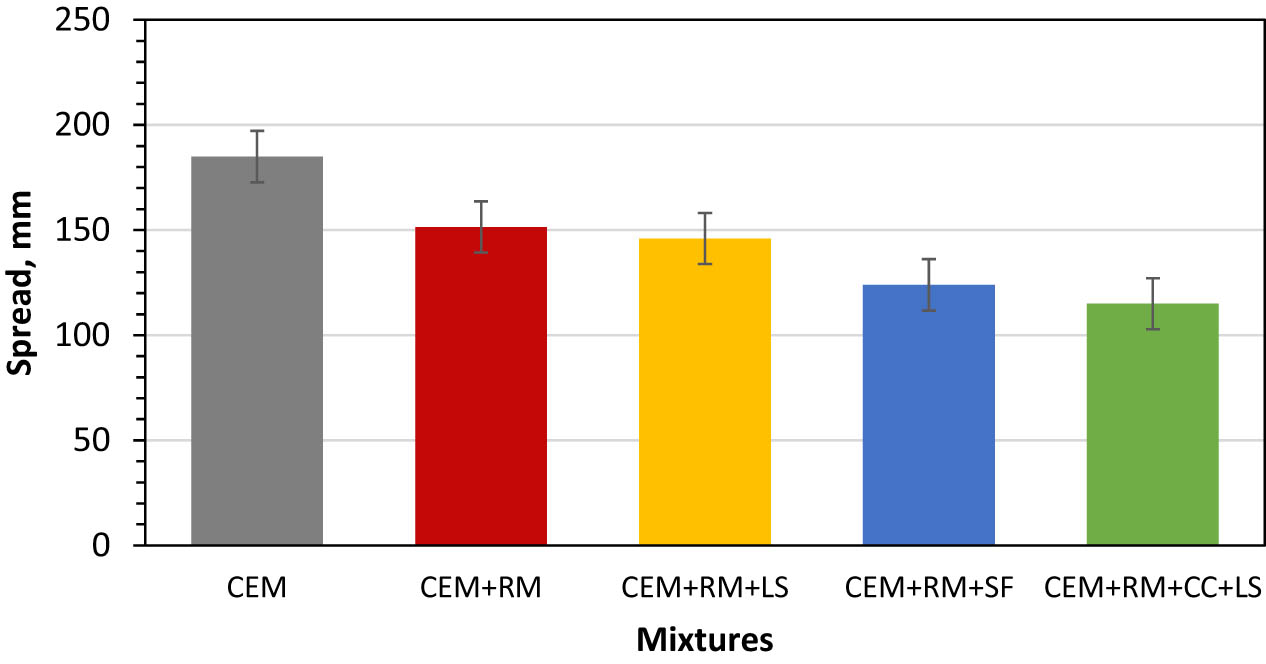

The results of the workability test of mixtures using the flow table method are shown in Figure 5. The reference mix showed the highest values of spreading. When cement was partially replaced by SCMs, the workability of the mixtures decreased with increasing SCM content. The large specific surface area of SCMs attracts water, which reduces the w/c ratio and thus the workability. The effect is also noted and reported in the studies of Hou et al. and Qureshi et al. [52,53]. This becomes particularly clear when comparing mixtures with SF and LS. The same amount of cement was used, but a significant difference in workability was found, which is due to the much finer particles of SF compared to LS, which affects the workability.

Workability results measured as spreading on a flow table.

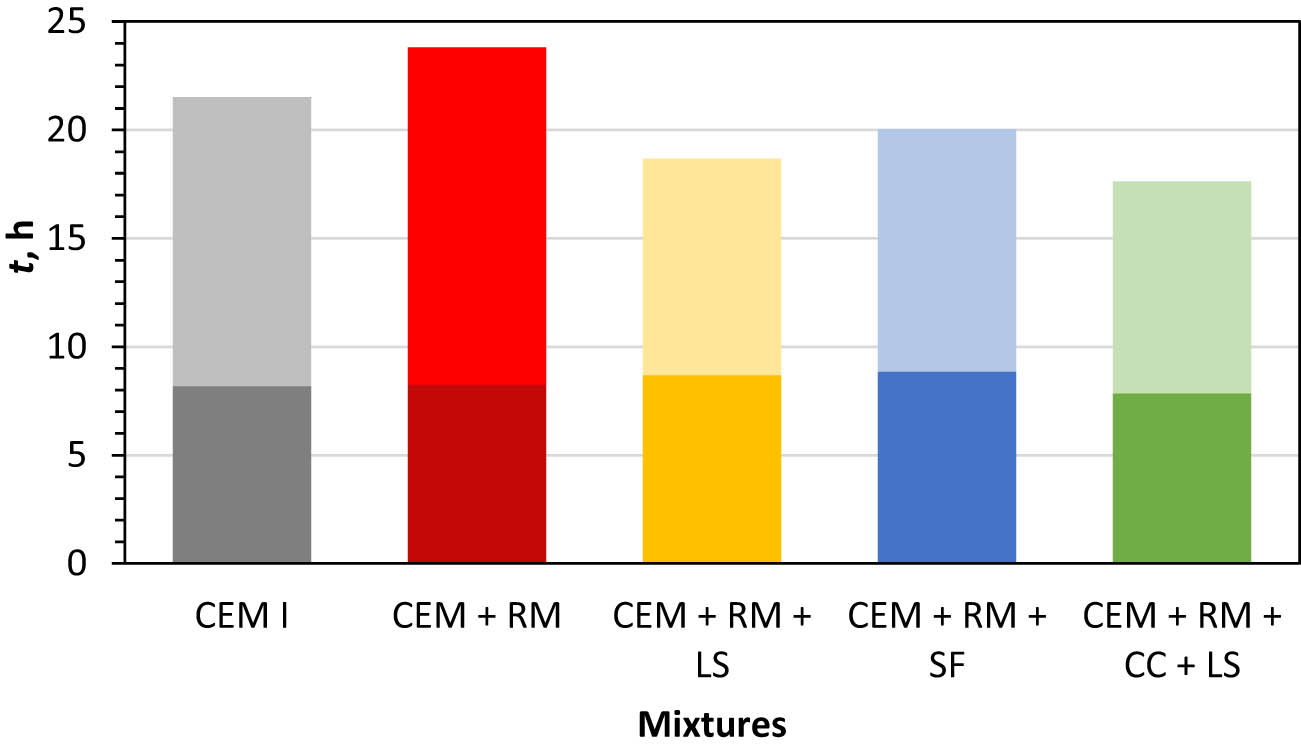

The results of the setting time tests for all five mixtures are shown in Figure 6. The partial cement replacement by SCM led to an increasingly later start of setting, except for the mixture with RM, CC, and LS. In this mixture, in which 35% of the cement is replaced by RM, CC, and LS, the start of setting is earlier than in the reference sample. The earliest end of setting was again determined for the same mixture. Other mixtures have an earlier end of setting compared to the reference mixture, while the mixture with only RM has a later end of setting [19]. The effect can be explained by the fact that RM fine particles retain water and later release it resulting in a higher setting time when only RM is added. However, when RM, LS, and CC are present, higher reaction and faster setting were observed. This can be explained by the additional activation of LS and CC due to the high alkalinity and alumina content of RM [52]. It is interesting to compare mixtures in which 20% LS or 20% SF was added in addition to RM. These two mixtures have the same cement content but slightly different setting times, which indicates the different influence of LS and SF on setting.

Initial and final setting of the tested mixtures.

3.2 Autogenous shrinkage test results

The results of autogenous shrinkage for all mixtures are shown in Figure 7. Here, the results are given from the initial time of measurement, without taking into account the different phases of the hydration process. It can be observed that there is a clear increase in deformation immediately after the start of the measurement. As the cement paste has not yet hardened and there is a very high w/b ratio, this initial increase in deformation can be attributed to the spreading of the mixture and the precipitation and segregation of the particles, with the cement particles tending to settle at the bottom and the water escaping at the top of the corrugated tube. The intensity of this initial deformation correlates with the workability of the mixes, with the sole exception of the mix with RM. For all other mixtures, better workability led to a higher initial deformation, possibly caused by segregation of the particles. In the case of RM mixture, it is possible that the RM particles do not settle during this initial phase due to the fineness of the particles. It is also possible that the RM particles initially swell as soon as they are surrounded by water.

Autogenous shrinkage of studied mortars.

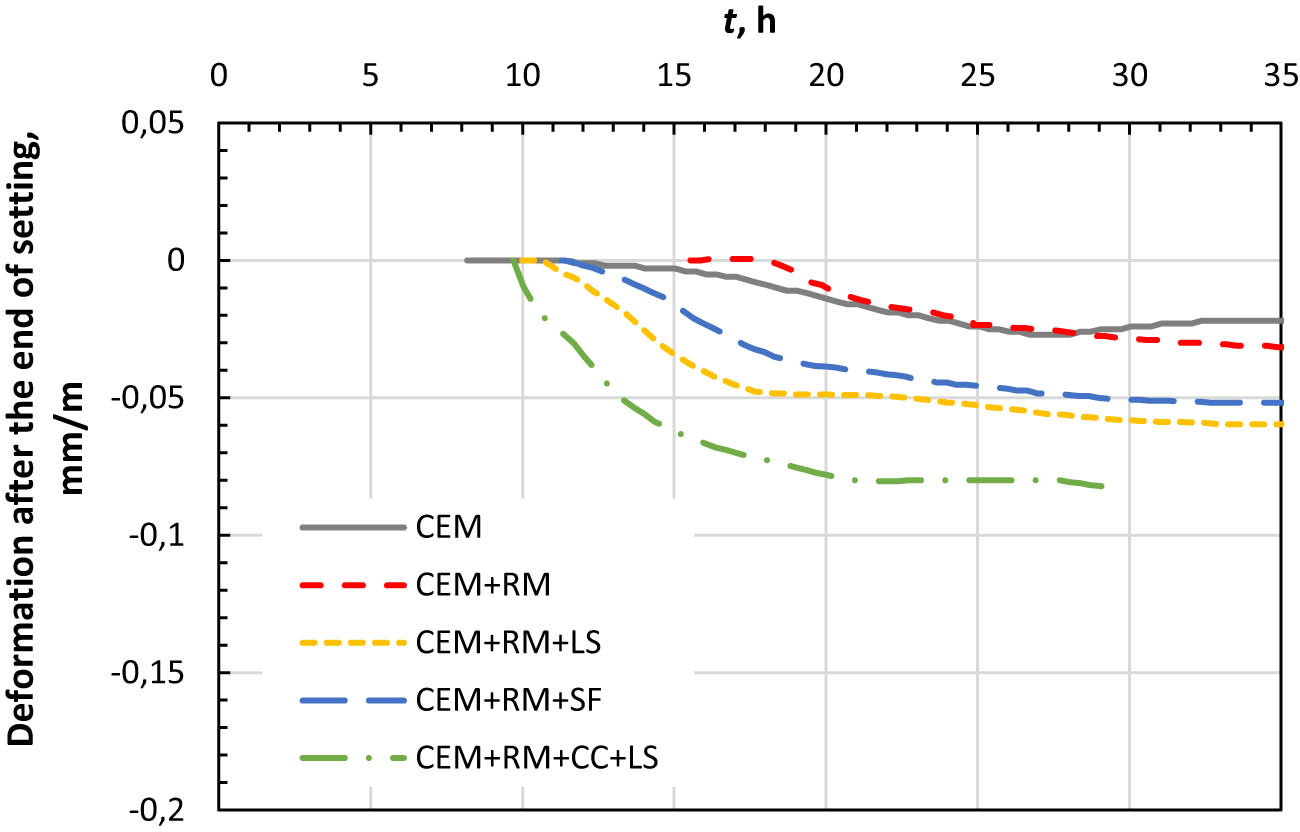

Figure 8 shows the results of autogenous shrinkage from “time zero,” which was taken as the final setting time determined with the Vicat needle method [50]. Time zero represents the point at which actual shrinkage due to self-desiccation and hydration start, when the internal relative humidity starts to decrease, i.e., when all the water has been reabsorbed.

Autogenous shrinkage deformation after the final setting taken as “time zero.”

The observed deformations after time zero (Figure 8) are significantly smaller than the total deformations shown in Figure 7. These graphs also show how the deformation due to autogenous shrinkage increases with increasing addition of SCM. The reference mix with cement showed the lowest values of autogenous shrinkage. It is interesting to note the swelling, the positive deformation in the case of the reference mix, and the mix with RM, which are possibly caused by reabsorption of the bleed water, i.e., the water that increased on the surface of the cement sample.

There could be several reasons for the increased autogenous deformation in mixtures with blended cement. First, the particles of most SCMs used are significantly smaller than cement particles and have a much larger surface area. As soon as these smaller particles come into contact with water, they require a higher amount of water for wetting, while the cement has a smaller amount of water available for reaction. This leads to a faster reaction of the cement particles with water and the need to attract more water, resulting in higher self-desiccation and the formation of deformations similar to those of cement pastes with a smaller w/c ratio. The second reason is the reactivity of used SCMs. The used SCMs lead to the formation of additional reaction products, which is further leading to the refinement of the pore structure, i.e., the formation of a larger number of finer pores. Such finer pores lead to an increase in pore pressure and an increase in deformation [54,55,56,57].

3.3 Strength test results

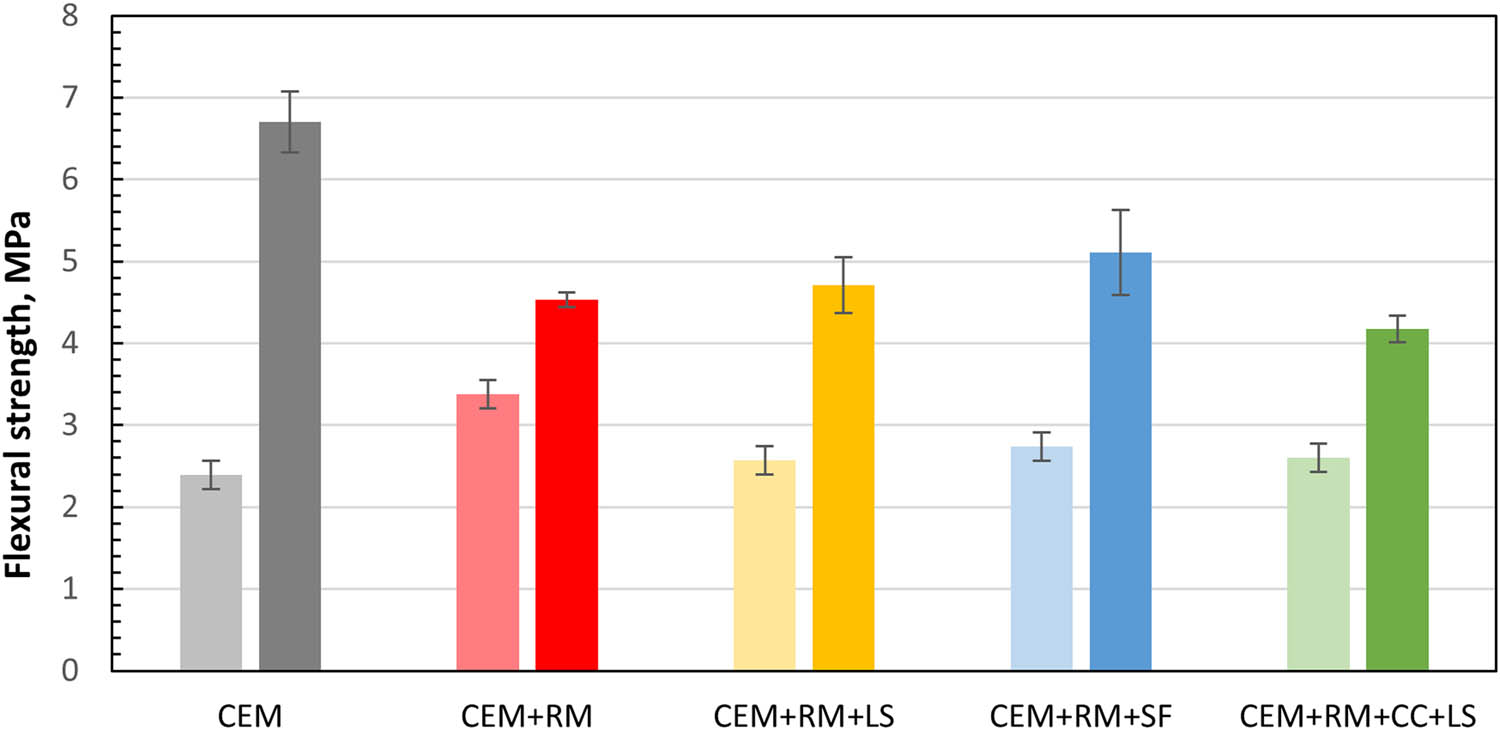

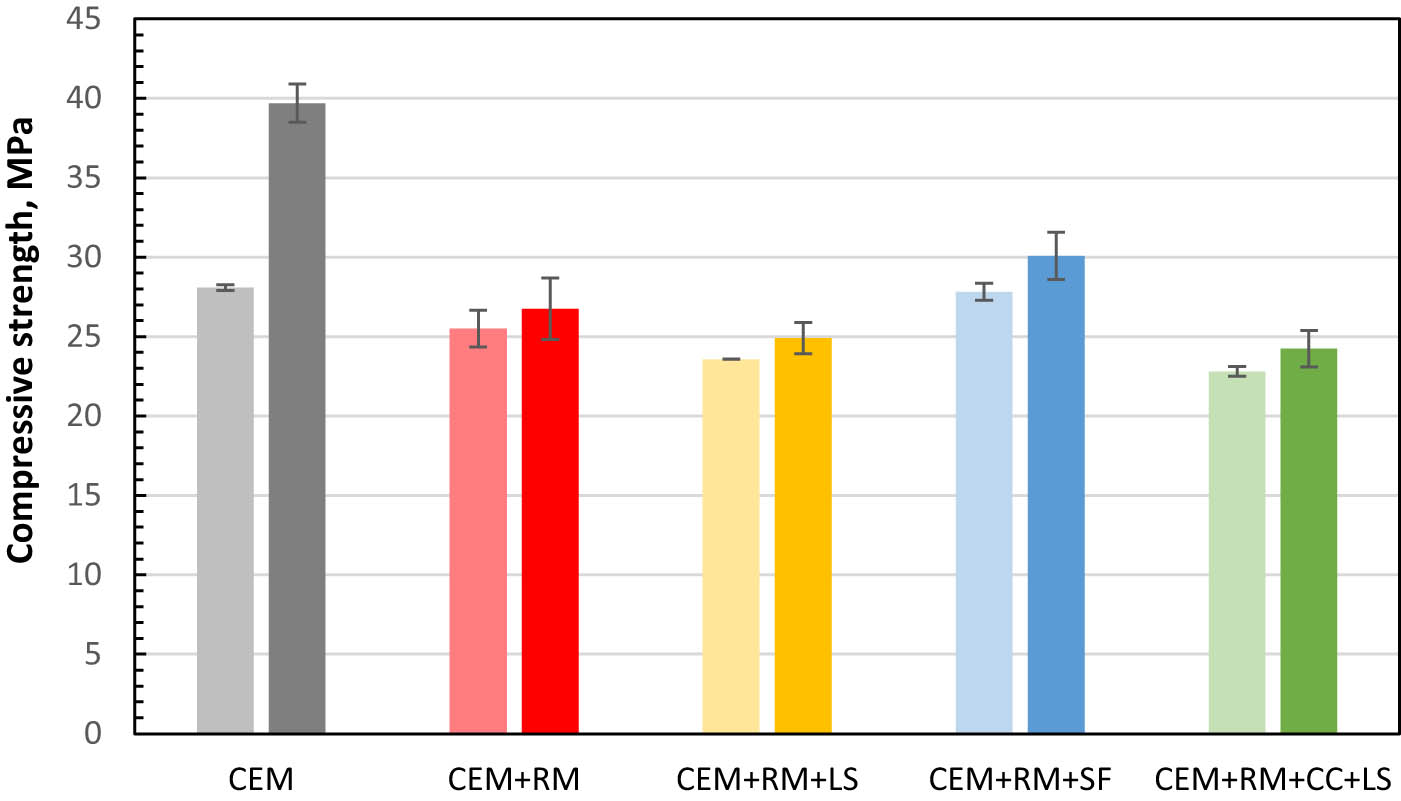

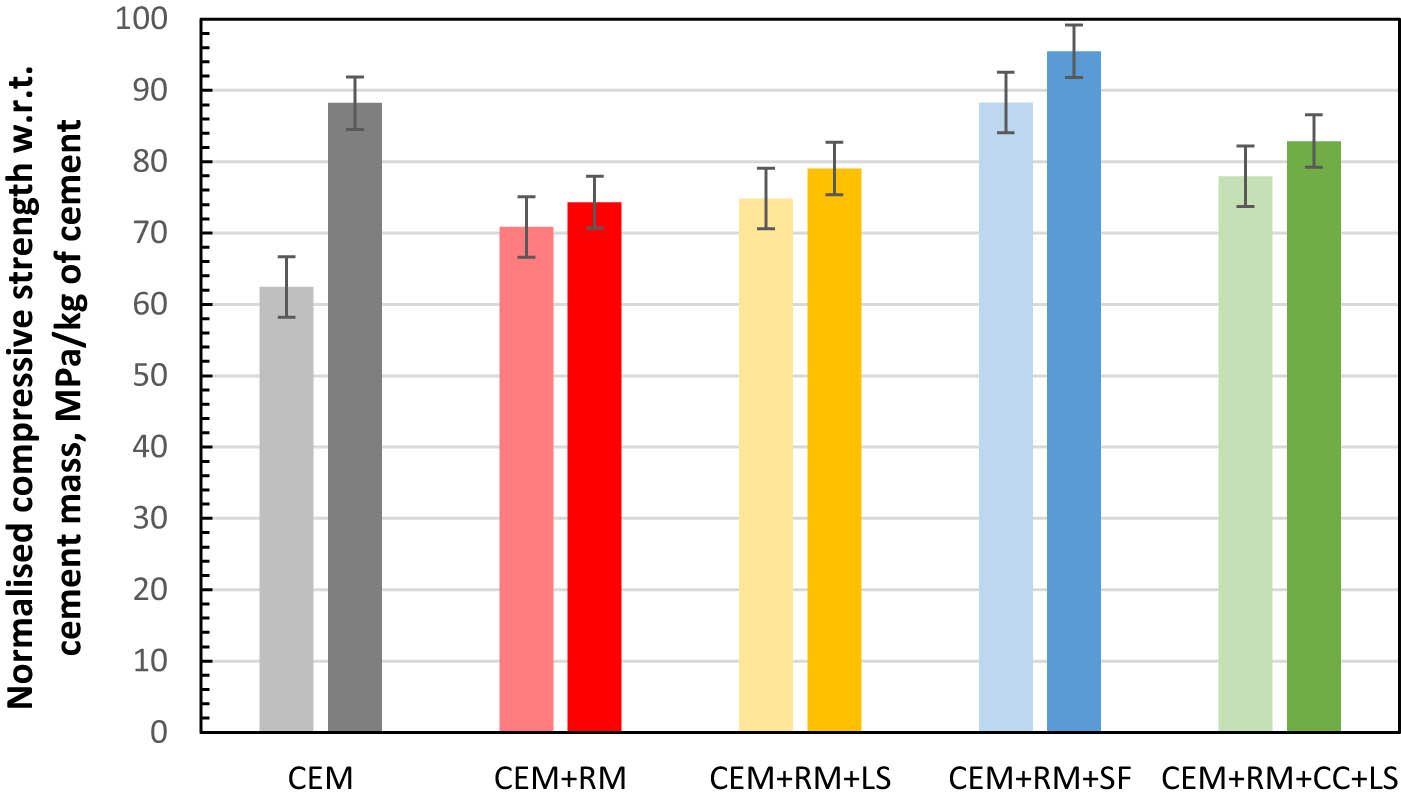

Flexural (Figure 9) and compressive strength (Figure 10) tests were performed after 7 and 28 days of curing.

Flexural strength after 7 and 28 days of curing.

Compressive strength test results after 7 and 28 days of curing.

After 7 days, the samples of the reference mixture showed the lowest values for flexural strength. All other mixtures with SCM achieved higher strength, 7.5% higher (CEM + RM + LS mixture) to 41% higher flexural strength (CEM + RM + SF mixture) compared to the reference. In contrast, the samples of the reference mixture exhibited the highest flexural strength after 28 days of curing compared to other samples. The decrease in flexural strength is between 8.5 (CEM + RM + LS mixture) and 60.7% (CEM + RM + CC + LS mixture) compared to the flexural strength value of the reference mixture. The flexural strength of all samples developed continuously over time. The fastest increase was recorded for the reference mix without SCMs. The slowest increase was observed for the mixture with 20% RM (CEM + RM).

The highest compressive strength values after 7 days of curing were determined for the reference mix with 100% cement. For other mixtures, a decrease of 8.1% (CEM + RM + SF mixture) to 23.1% (CEM + RM + CC + LS mixture) was observed compared to the compressive strength value of the reference mixture. After 28 days of curing, the results of compressive strength follow the same pattern as those of the flexural strength test. Here too, the reference mixture exhibited a significantly higher strength compared to all other mixtures, reaching around 40 MPa. Interestingly, the other mixtures exhibited compressive strength values close to those of the 7-day cured samples. This leads to a significant difference in the compressive strength of the other mixtures from 20.8 (CEM + RM + SF mixture) to 38.9% (CEM + RM + CC + LS mixture). Compressive strength increase was reported in Viyasun et al. [58] when 20% of RM was added to the mixture. Generally, a decrease in compressive strength with a high level of RM is expected [25,29,43]. This is attributed to the absence of secondary pozzolanic reaction, due to the low cement content and low reactivity of RM.

All samples develop compressive strength over time. The fastest increase was recorded for the reference mix, but for the other mixtures this increase is negligible. It is important to highlight the difference between the mixtures with RM and LS and RM and SF, which have different strengths for the same amount of cement and SCM, i.e., the mix sample with a combination of RM and SF has a higher compressive strength than the mix with a combination of RM and LS. The influence of SCMs on the formation of compressive strength can be better understood if the compressive strength is normalized to the cement mass. If there is no contribution from SCMs, the compressive strength normalized to the cement mass should be the same regardless of the addition of SCMs. The compressive strength normalized to the mass of cement in the mix is shown in Figure 11. The compressive strength per kg of cement is higher in all mixes with SCMs compared to the reference mix, which is in accordance with previous studies, where normalized compressive strength per kg cement was higher even with a high level of RM addition [59,60].

Compressive strength normalized per kg cement (with respect to mass of cement) for 7 and 28 days of age.

This confirms that the addition of SCM increases the reactivity of the cement, either through an additional hydration/pozzolanic reaction or through a filling effect where water is blocked and the cement reacts like cement paste with a lower water to cement ratio, resulting in a higher strength. This could also explain an increase in autogenous shrinkage of these mixtures.

4 Conclusions

In this work, mixtures with partial replacement of the cement by various SCMs in different quantities were investigated. The SCMs used were RM, LS, CC, and SF. Workability, autogenous shrinkage, setting time, and flexural and compressive strength of five mixtures were tested.

The workability results show that the workability of the mixes decreased as the cement content is reduced. It is important to note that for the same amount of cement, the mixture with RM and SF showed better workability than the mixture with RM and LS, indicating the different influence of SF and LS on workability.

The test of the setting time showed that the addition of SCM causes a slight delay in setting, except for the mixture with RM, CC, and LS, in which the start and end of setting occurred earlier than in the reference mixture.

The autogenous shrinkage from the so-called “time zero” was also investigated. It was found that these deformations are significantly lower than the total deformations. The deformation of the autogenous shrinkage gradually increased with increasing amounts of SCM. The reference mixture showed the lowest values of autogenous shrinkage, and the mixture with the highest degree of cement substitution showed the highest values of autogenous shrinkage.

The mechanical properties were evaluated by analyzing the flexural and compressive strength after 7 days and 28 days of curing.

The results for the flexural strength test show that the flexural strength of all samples developed continuously over time.

The results of compressive strength tests after 7 and 28 days of curing show that the compressive strength developed over time for all samples but to a lesser extent for the mixtures with SCM than the results of flexural strength tests. The fastest increase was recorded for the reference mixture and the slowest for the mixture with 20% RM.

By analyzing compressive strength normalized to the amount of cement in the binder, it was possible to conclude that the addition of SCM increased the efficiency of the cement, either through an additional hydration reaction or through a filling effect, which then well correlated with an increase in autogenous shrinkage of these mixes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Science from Bosnia and Herzegovina under the project “Development of sustainable concrete with alternative binders from industrial waste red mud and silica fume” (no. 05-35-2041-1/22) and the Croatian Science Foundation project “Alternative binders for concrete: understanding the microstructure to predict durability, ABC” (UIP-05-2017-4767). The authors would like to thank Lucija Šušak for her help during laboratory tests.

-

Funding information: This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Science from Bosnia and Herzegovina under the project no. 05-35-2041-1/22 and the Croatian Science Foundation project UIP-05-2017-4767.

-

Author contributions: All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

-

Conflict of interest: The authors state no conflict of interest.

-

Data availability statement: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

[1] CEMBUREAU. Activity Report 2022, CEMBUREAU, Brussels, 2022. Available from https://cembureau.eu/library/reports/.Suche in Google Scholar

[2] Serdar, M., D. Bjegović, N. Štirmer, and I. B. Pečur. Research challenges for broader application of alternative binders in concrete. Građevinar, Vol. 71, No. 10, 2019, pp. 877–888.10.14256/JCE.2729.2019Suche in Google Scholar

[3] European Commission. The European Green Deal, European Commission, Brussels. Available from https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en.Suche in Google Scholar

[4] Global Cement and Concrete Association. GCCA 2050 Roadmap for Net Zero Carbon Concrete, GCCA, London. Available from https://gccassociation.org/concretefuture/.Suche in Google Scholar

[5] Lollini, F., E. Redaelli, and L. Bertolini. Effects of portland cement replacement with limestone on the properties of hardened concrete. Cement & Concrete Composites, Vol. 46, 2014, pp. 32–40.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2013.10.016Suche in Google Scholar

[6] Tsivilis, S., G. Batis, E. Chaniotakis, G. Grigoriadis, and D. Theodossis. Properties and behavior of limestone cement concrete and mortar. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 30, No. 10, 2000, pp. 1679–1683.10.1016/S0008-8846(00)00372-0Suche in Google Scholar

[7] Mousavi, S. S., C. Bhojaraju, and C. Ouellet-Plamondon. Clay as a sustainable binder for concrete: A review. Construction Materials, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2021, pp. 134–168.10.3390/constrmater1030010Suche in Google Scholar

[8] Sánchez Berriel, S., A. Favier, E. Rosa Domínguez, I. R. Sánchez Machado, U. Heierli, K. Scrivener, et al. Assessing the environmental and economic potential of limestone calcined clay cement in Cuba. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 124, 2016, pp. 361–369.10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.125Suche in Google Scholar

[9] Mathieu, A. Investigation of cement substitution by blends of calcined clays and limestone [dissertation], EPFL, Lausanne, 2014.Suche in Google Scholar

[10] Vladić Kancir, I. and M. Serdar. Contribution to understanding of synergy between red mud and common supplementary cementitious materials. Materials, Vol. 15, No. 5, 2022, id. 1968.10.3390/ma15051968Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[11] Venkatesh, C., N. Ruben, and S. R. C. Madduru. Red mud as an additive in concrete: comprehensive characterization. Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society, Vol. 57, No. 3, 2020, pp. 281–289.10.1007/s43207-020-00030-3Suche in Google Scholar

[12] Serdar, M., I. Biljecki, and D. Bjegović. High performance concrete incorporating locally available industrial by-products. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2017.10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0001773Suche in Google Scholar

[13] Liu, Y., Y. Zhuge, X. Chen, W. Duan, R. Fan, L. Outhred, et al. Micro-chemomechanical properties of red mud binder and its effect on concrete. Composites Part B: Engineering, Vol. 258, 2023, id. 110688.10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.110688Suche in Google Scholar

[14] Zeng, H., F. Lyu, W. Sun, H. Zhang, L. Wang, and Y. Wang. Progress on the industrial applications of red mud with a focus on China. Minerals, Vol. 10, 2020, id. 773.Suche in Google Scholar

[15] Kumar, A. and S. Kumar. Development of paving blocks from synergistic use of red mud and fly ash using geopolymerization. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 38, 2013, pp. 865–871.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2012.09.013Suche in Google Scholar

[16] Tang, W., M. Khavarian, A. Yousefi. Red mud, sustainable concrete made with ashes and dust from different sources. In: Sustainable Concrete Materials, R. Siddique and R. Belarbi, eds., Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2022, p. 577–606.10.1016/B978-0-12-824050-2.00013-9Suche in Google Scholar

[17] Obhodas, J., D. Sudac, L. Matjačić, and V. Valković. Red mud characterization using nuclear analytical techniques. In: Proc 2nd Int Conf Advancements in Nuclear Instrumentation, Measurement Methods and their Applications; 2011 Jun 13–17, IEEE, Ghent, Belgium, 2011, pp. 1–5.10.1109/ANIMMA.2011.6172957Suche in Google Scholar

[18] Paramguru, R. K., P. C. Rath, and V. N. Misra. Trends in red mud utilization: A review. Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy Review, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2004, pp. 1–29.10.1080/08827500490477603Suche in Google Scholar

[19] Ćećez, M. and M. Šahinagić-Isović. Mortars with addition of local industrial by-products. Građevinar, Vol. 71, No. 1, 2019, pp. 1–7.10.14256/JCE.2358.2018Suche in Google Scholar

[20] Ribeiro, D. V., J. A. Labrincha, and M. R. Morelli. Potential use of natural red mud as pozzolan for Portland cement. Materials Research, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2011, pp. 60–66.10.1590/S1516-14392011005000001Suche in Google Scholar

[21] Liu, X., N. Zhang, H. Sun, J. Zhang, and L. Li. Structural investigation relating to the cementitious activity of bauxite residue: Red mud. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 41, 2011, pp. 847–853.10.1016/j.cemconres.2011.04.004Suche in Google Scholar

[22] Tsakiridis, P. E., S. Agatzini-Leonardou, and P. Oustadakis. Red mud addition in the raw meal for the production of Portland cement clinker. Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 116, No. 1–2, 2004, pp. 103–110.10.1016/j.jhazmat.2004.08.002Suche in Google Scholar PubMed

[23] Senff, L., A. Castela, W. Hajjaji, D. Hotza, and J. A. Labrincha. Formulations of sulfobelite cement through design of experiments. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 25, No. 8, 2011, pp. 3410–3416.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.03.032Suche in Google Scholar

[24] Pan, Z., L. Cheng, Y. Lu, and N. Yang. Hydration products of alkali-activated slag–red mud cementitious material. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 32, 2002, pp. 357–362.10.1016/S0008-8846(01)00683-4Suche in Google Scholar

[25] Choe, G., S. Kang, and H. Kang. Mechanical properties of concrete containing liquefied red mud subjected to uniaxial compression loads. Materials, Vol. 13, No. 4, 2020, id. 845.10.3390/ma13040854Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[26] Rathod, R. R., P. M. Kulkarni, V. S. Shingade, and S. S. Deshmukh. Suitability of red mud as an admixture in concrete. International Journal of Modern Trends in Engineering and Research, Vol. 2, No. 7, 2015, pp. 880–884.Suche in Google Scholar

[27] Venkatesh, C., R. Nerella, and S. R. C. Madduru. Experimental investigation of strength, durability, and microstructure of red‑mud concrete. Journal of the Korean Ceramic Society, Vol. 57, No. 2, 2019, pp. 167–174.10.1007/s43207-019-00014-ySuche in Google Scholar

[28] Li, W. Y., Z. Y. Zhang, and J. B. Zhou. Preparation of building materials from Bayer red mud with magnesium cement. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 323, 2022, id. 126507.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126507Suche in Google Scholar

[29] Lothenbach, B., K. Scrivener, and R. D. Hooton. Supplementary cementitious materials. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 41, No. 12, 2011, pp. 1244–1256.10.1016/j.cemconres.2010.12.001Suche in Google Scholar

[30] Zeng, H., F. Lyu, W. Sun, H. Zhang, L. Wang, and Y. Wang. Progress on the industrial applications of red mud with a focus on China. Minerals, Vol. 10, 2020, id. 773.10.3390/min10090773Suche in Google Scholar

[31] Pontikes, Y. and G. N. Angelopoulos. Bauxite residue in cement and cementitious applications: Current status and a possible way forward. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, Vol. 73, 2013, pp. 53–65.10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.01.005Suche in Google Scholar

[32] Dodoo-Arhin, D., R. A. Nuamah, B. Agyei-Tuffour, D. O. Obada, and A. Yaya. Awaso bauxite red mud-cement based composites: Characterisation for pavement applications. Case Studies in Construction Materials, Vol. 7, 2017, pp. 45–55.10.1016/j.cscm.2017.05.003Suche in Google Scholar

[33] Sawant, A. B., M. B. Kumthekar, V. V. Diwan, and K. G. Hiraskar. Experimental study on partial replacement of cement by neutralized red mud in concrete. The International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2012, pp. 282–286.Suche in Google Scholar

[34] Ribeiro, D. V., J. A. Labrincha, and M. R. Morelli. Analysis of chloride diffusivity in concrete containing red mud. IBRACON Structures and Materials Journal, Vol. 5, No. 2, 2012, pp. 137–152.10.1590/S1983-41952012000200002Suche in Google Scholar

[35] Venkatesh, C., S. K. Mohiddin and N. Ruben. Corrosion inhibitors behaviour on reinforced concrete: A review. In: Sustainable construction and building materials. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, B. Das and N. Neithalath, eds., Springer, Singapore, 2019, p. 287–309.10.1007/978-981-13-3317-0_11Suche in Google Scholar

[36] Viyasun, K., R. Anuradha, K. Thangapandi, D. Santhosh Kumar, A. Sivakrishna, and R. Gobinath. Investigation on performance of red mud based concrete. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2021, pp. 796–799.Suche in Google Scholar

[37] Senff, L., R. C. E. Modolo, S. A. Silva, V. M. Ferreira, D. Hotza, and J. A. Labrincha. Influence of red mud addition on rheological behavior and hardened properties of mortars. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 65, 2014, pp. 84–91.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.04.104Suche in Google Scholar

[38] Liu, R. and C. Poon. Effects of red mud on properties of self-compacting mortar. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 135, 2016, pp. 1170–1178.10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.07.052Suche in Google Scholar

[39] Wyrzykowski, M., C. Di Bella, D. Sirtoli, N. Toropovs and P. Lura. Plastic shrinkage of concrete made with calcined clay-limestone cement. Cement and Concrete Research, Vol. 189, 2025, id. 107784.10.1016/j.cemconres.2025.107784Suche in Google Scholar

[40] Hertel, T. and Y. Pontikes. Geopolymers, inorganic polymers, alkali-activated materials and hybrid binders from bauxite residue (red mud): Putting things in perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 258, 2020, id. 120610.10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120610Suche in Google Scholar

[41] Vladić Kancir, I. and M. Serdar. Synergy of red mud, calcined clay and limestone in cementitious binders. In: Proc 7th Symp Doctoral Studies Civil Engineering, Zagreb, Croatia, 2021 Jun, p. 1–6.10.5592/CO/ZT.2021.17Suche in Google Scholar

[42] Flegar, M., M. Serdar, D. Londono-Zuluaga, and K. Scrivener. Regional waste streams as potential raw materials for immediate implementation in cement production. Materials, Vol. 13, No. 23, 2020, id. 5456.10.3390/ma13235456Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[43] Feng, L., W. Yao, K. Zheng, N. Cui, and N. Xie. Synergistically using bauxite residue (red mud) and other solid wastes to manufacture eco-friendly cementitious materials. Buildings, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2022, id. 117.10.3390/buildings12020117Suche in Google Scholar

[44] Ćećez, M. and M. Šahinagić-Isović. Fresh and hardened concrete properties containing red mud and silica fume. Građevinar, Vol. 75, No. 5, 2023, pp. 439–449.10.14256/JCE.3620.2022Suche in Google Scholar

[45] Peys, A., T. Hertel, and R. Snellings. Co-calcination of bauxite residue with kaolinite in pursuit of a robust and high-quality supplementary cementitious material. Frontiers in Materials, Vol. 9, 2022, id. 913151.10.3389/fmats.2022.913151Suche in Google Scholar

[46] Scrivener, K., M. Ben Haha, P. Juilland, and C. Levy. Research needs for cementitious building materials with focus on Europe. RILEM Techical Letters, Vol. 7, 2023, pp. 220–252.10.21809/rilemtechlett.2022.165Suche in Google Scholar

[47] European Committee for Standardization. EN 450-1:2012. Fly ash for concrete – Part 1: Definition, specifications and conformity criteria, CEN, Brussels, 2012.Suche in Google Scholar

[48] ASTM International. C618 – 19. Standard specification for coal fly ash and raw or calcined natural pozzolan for use, ASTM International, West Conshohocken (PA), 2010.Suche in Google Scholar

[49] Jensen, M. O. and P. F. Hansen. A dilatometer for measuring autogenous deformation in hardening Portland cement paste. Materials and Structures, Vol. 28, 1995, pp. 406–409.10.1007/BF02473076Suche in Google Scholar

[50] Wyrzykowski, M., Z. Hu, S. Ghourchian, K. Scrivener, and P. Lura. Corrugated tube protocol for autogenous shrinkage measurements: review and statistical assessment. Materials and Structures, Vol. 50, 2017, id. 57.10.1617/s11527-016-0933-2Suche in Google Scholar

[51] Gao, P., T. Zhang, R. Luo, J. Wei, and Q. Yu. Improvement of autogenous shrinkage measurement for cement paste at very early age: Corrugated tube method using non-contact sensors. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 55, 2014, pp. 57–62.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2013.12.086Suche in Google Scholar

[52] Hou, D., D. Wu, X. Wang, S. Gao, R. Yu, M. Li, et al. Sustainable use of red mud in ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC): Design and performance evaluation. Cement and Concrete Composites, Vol. 115, 2021, id. 103862.10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2020.103862Suche in Google Scholar

[53] Qureshi, H. J., J. Ahmad, A. Majdi, M. U. Saleem, A. F. Al Fuhaid, and M. Arifuzzaman. A study on sustainable concrete with partial substitution of cement with red mud: A review. Materials, Vol. 15, 2022, id. 7761.10.3390/ma15217761Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[54] Muhammad, A., K. C. Thienel, and R. Sposito. Suitability of blending rice husk ash and calcined clay for the production of self-compacting concrete: A review. Materials, Vol. 14, No. 21, 2021, id. 6252.10.3390/ma14216252Suche in Google Scholar PubMed PubMed Central

[55] Li, Y., J. Bao, and Y. Guo. The relationship between autogenous shrinkage and pore structure of cement paste with mineral admixtures. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 24, No. 10, 2010, pp. 1855–1860.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.04.018Suche in Google Scholar

[56] Afroz, S., Y. Zhang, Q. D. Nguyen, T. Kim, and A. Castel. Shrinkage of blended cement concrete with fly ash or limestone calcined clay. Materials and Structures, Vol. 56, 2023, id. 15.10.1617/s11527-023-02099-8Suche in Google Scholar

[57] Yan, P., B. Chen, M. A. Haque, and T. Liu. Influence of red mud on the engineering and microstructural properties of sustainable ultra-high performance concrete. Construction and Building Materials, Vol. 396, 2023, id. 132404.10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132404Suche in Google Scholar

[58] Viyasun, K., R. Anuradha, K. Thangapandi, D. Santhosh Kumar, A. Sivakrishna, and R. Gobinath. Investigation on performance of red mud based concrete. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 39, No. 1, 2021, pp. 796–799.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.09.637Suche in Google Scholar

[59] Venkatesh, C., R. Nerella, and M. S. R. Chand. Role of red mud as a cementing material in concrete: a comprehensive study on durability behavior. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, Vol. 6, 2021, id. 13.10.1007/s41062-020-00371-2Suche in Google Scholar

[60] Saravanan, B. and D. S. Vijayan. Status review on experimental investigation on replacement of red-mud in cementitious concrete. Materials Today: Proceedings, Vol. 33, No. 1, 2020, pp. 593–598.10.1016/j.matpr.2020.05.500Suche in Google Scholar

© 2025 the author(s), published by De Gruyter

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Towards sustainable concrete pavements: a critical review on fly ash as a supplementary cementitious material

- Optimizing rice husk ash for ultra-high-performance concrete: a comprehensive review of mechanical properties, durability, and environmental benefits

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Experimental and RSM-based optimization of sustainable concrete properties using glass powder and rubber fine aggregates as partial replacements

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods

Artikel in diesem Heft

- Review Articles

- Utilization of steel slag in concrete: A review on durability and microstructure analysis

- Technical development of modified emulsion asphalt: A review on the preparation, performance, and applications

- Recent developments in ultrasonic welding of similar and dissimilar joints of carbon fiber reinforcement thermoplastics with and without interlayer: A state-of-the-art review

- Unveiling the crucial factors and coating mitigation of solid particle erosion in steam turbine blade failures: A review

- From magnesium oxide, magnesium oxide concrete to magnesium oxide concrete dams

- Properties and potential applications of polymer composites containing secondary fillers

- A scientometric review on the utilization of copper slag as a substitute constituent of ordinary Portland cement concrete

- Advancement of additive manufacturing technology in the development of personalized in vivo and in vitro prosthetic implants

- Recent advance of MOFs in Fenton-like reaction

- A review of defect formation, detection, and effect on mechanical properties of three-dimensional braided composites

- Non-conventional approaches to producing biochars for environmental and energy applications

- Review of the development and application of aluminum alloys in the nuclear industry

- Advances in the development and characterization of combustible cartridge cases and propellants: Preparation, performance, and future prospects

- Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review

- Cement-based materials for radiative cooling: Potential, material and structural design, and future prospects

- A comprehensive review: The impact of recycling polypropylene fiber on lightweight concrete performance

- A comprehensive review of preheating temperature effects on reclaimed asphalt pavement in the hot center plant recycling

- Exploring the potential applications of semi-flexible pavement: A comprehensive review

- A critical review of alkali-activated metakaolin/blast furnace slag-based cementitious materials: Reaction evolution and mechanism

- Dispersibility of graphene-family materials and their impact on the properties of cement-based materials: Application challenges and prospects

- Research progress on rubidium and cesium separation and extraction

- A step towards sustainable concrete with the utilization of M-sand in concrete production: A review

- Studying the effect of nanofillers in civil applications: A review

- Studies on the anticorrosive effect of phytochemicals on mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless-steel surfaces in acid and alkali medium: A review

- Nanotechnology for calcium aluminate cement: thematic analysis

- Towards sustainable concrete pavements: a critical review on fly ash as a supplementary cementitious material

- Optimizing rice husk ash for ultra-high-performance concrete: a comprehensive review of mechanical properties, durability, and environmental benefits

- Research Articles

- Investigation of the corrosion performance of HVOF-sprayed WC-CoCr coatings applied on offshore hydraulic equipment

- A systematic review of metakaolin-based alkali-activated and geopolymer concrete: A step toward green concrete

- Evaluation of color matching of three single-shade composites employing simulated 3D printed cavities with different thicknesses using CIELAB and CIEDE2000 color difference formulae

- Novel approaches in prediction of tensile strain capacity of engineered cementitious composites using interpretable approaches

- Effect of TiB2 particles on the compressive, hardness, and water absorption responses of Kulkual fiber-reinforced epoxy composites

- Analyzing the compressive strength, eco-strength, and cost–strength ratio of agro-waste-derived concrete using advanced machine learning methods

- Tensile behavior evaluation of two-stage concrete using an innovative model optimization approach

- Tailoring the mechanical and degradation properties of 3DP PLA/PCL scaffolds for biomedical applications

- Optimizing compressive strength prediction in glass powder-modified concrete: A comprehensive study on silicon dioxide and calcium oxide influence across varied sample dimensions and strength ranges

- Experimental study on solid particle erosion of protective aircraft coatings at different impact angles

- Compatibility between polyurea resin modifier and asphalt binder based on segregation and rheological parameters

- Fe-containing nominal wollastonite (CaSiO3)–Na2O glass-ceramic: Characterization and biocompatibility

- Relevance of pore network connectivity in tannin-derived carbons for rapid detection of BTEX traces in indoor air

- A life cycle and environmental impact analysis of sustainable concrete incorporating date palm ash and eggshell powder as supplementary cementitious materials

- Eco-friendly utilisation of agricultural waste: Assessing mixture performance and physical properties of asphalt modified with peanut husk ash using response surface methodology

- Benefits and limitations of N2 addition with Ar as shielding gas on microstructure change and their effect on hardness and corrosion resistance of duplex stainless steel weldments

- Effect of selective laser sintering processing parameters on the mechanical properties of peanut shell powder/polyether sulfone composite

- Impact and mechanism of improving the UV aging resistance performance of modified asphalt binder

- AI-based prediction for the strength, cost, and sustainability of eggshell and date palm ash-blended concrete

- Investigating the sulfonated ZnO–PVA membrane for improved MFC performance

- Strontium coupling with sulphur in mouse bone apatites

- Transforming waste into value: Advancing sustainable construction materials with treated plastic waste and foundry sand in lightweight foamed concrete for a greener future

- Evaluating the use of recycled sawdust in porous foam mortar for improved performance

- Improvement and predictive modeling of the mechanical performance of waste fire clay blended concrete

- Polyvinyl alcohol/alginate/gelatin hydrogel-based CaSiO3 designed for accelerating wound healing

- Research on assembly stress and deformation of thin-walled composite material power cabin fairings

- Effect of volcanic pumice powder on the properties of fiber-reinforced cement mortars in aggressive environments

- Analyzing the compressive performance of lightweight foamcrete and parameter interdependencies using machine intelligence strategies

- Selected materials techniques for evaluation of attributes of sourdough bread with Kombucha SCOBY

- Establishing strength prediction models for low-carbon rubberized cementitious mortar using advanced AI tools

- Investigating the strength performance of 3D printed fiber-reinforced concrete using applicable predictive models

- An eco-friendly synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles with jamun seed extract and their multi-applications

- The application of convolutional neural networks, LF-NMR, and texture for microparticle analysis in assessing the quality of fruit powders: Case study – blackcurrant powders

- Study of feasibility of using copper mining tailings in mortar production

- Shear and flexural performance of reinforced concrete beams with recycled concrete aggregates

- Advancing GGBS geopolymer concrete with nano-alumina: A study on strength and durability in aggressive environments

- Leveraging waste-based additives and machine learning for sustainable mortar development in construction

- Study on the modification effects and mechanisms of organic–inorganic composite anti-aging agents on asphalt across multiple scales

- Morphological and microstructural analysis of sustainable concrete with crumb rubber and SCMs

- Structural, physical, and luminescence properties of sodium–aluminum–zinc borophosphate glass embedded with Nd3+ ions for optical applications

- Eco-friendly waste plastic-based mortar incorporating industrial waste powders: Interpretable models for flexural strength

- Bioactive potential of marine Aspergillus niger AMG31: Metabolite profiling and green synthesis of copper/zinc oxide nanocomposites – An insight into biomedical applications

- Preparation of geopolymer cementitious materials by combining industrial waste and municipal dewatering sludge: Stabilization, microscopic analysis and water seepage

- Seismic behavior and shear capacity calculation of a new type of self-centering steel-concrete composite joint

- Sustainable utilization of aluminum waste in geopolymer concrete: Influence of alkaline activation on microstructure and mechanical properties

- Optimization of oil palm boiler ash waste and zinc oxide as antibacterial fabric coating

- Tailoring ZX30 alloy’s microstructural evolution, electrochemical and mechanical behavior via ECAP processing parameters

- Comparative study on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on the production of sustainable concrete

- Microemulsion synthesis of zinc-containing mesoporous bioactive silicate glass nanoparticles: In vitro bioactivity and drug release studies

- On the interaction of shear bands with nanoparticles in ZrCu-based metallic glass: In situ TEM investigation

- Developing low carbon molybdenum tailing self-consolidating concrete: Workability, shrinkage, strength, and pore structure

- Experimental and computational analyses of eco-friendly concrete using recycled crushed brick

- High-performance WC–Co coatings via HVOF: Mechanical properties of steel surfaces

- Mechanical properties and fatigue analysis of rubber concrete under uniaxial compression modified by a combination of mineral admixture

- Experimental study of flexural performance of solid wood beams strengthened with CFRP fibers

- Eco-friendly green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with Syzygium aromaticum extract: characterization and evaluation against Schistosoma haematobium

- Predictive modeling assessment of advanced concrete materials incorporating plastic waste as sand replacement

- Self-compacting mortar overlays using expanded polystyrene beads for thermal performance and energy efficiency in buildings

- Enhancing frost resistance of alkali-activated slag concrete using surfactants: sodium dodecyl sulfate, sodium abietate, and triterpenoid saponins

- Equation-driven strength prediction of GGBS concrete: a symbolic machine learning approach for sustainable development

- Empowering 3D printed concrete: discovering the impact of steel fiber reinforcement on mechanical performance

- Advanced hybrid machine learning models for estimating chloride penetration resistance of concrete structures for durability assessment: optimization and hyperparameter tuning

- Influence of diamine structure on the properties of colorless and transparent polyimides

- Post-heating strength prediction in concrete with Wadi Gyada Alkharj fine aggregate using thermal conductivity and ultrasonic pulse velocity

- Experimental and RSM-based optimization of sustainable concrete properties using glass powder and rubber fine aggregates as partial replacements

- Special Issue on Recent Advancement in Low-carbon Cement-based Materials - Part II

- Investigating the effect of locally available volcanic ash on mechanical and microstructure properties of concrete

- Flexural performance evaluation using computational tools for plastic-derived mortar modified with blends of industrial waste powders

- Foamed geopolymers as low carbon materials for fire-resistant and lightweight applications in construction: A review

- Autogenous shrinkage of cementitious composites incorporating red mud

- Mechanical, durability, and microstructure analysis of concrete made with metakaolin and copper slag for sustainable construction

- Special Issue on AI-Driven Advances for Nano-Enhanced Sustainable Construction Materials

- Advanced explainable models for strength evaluation of self-compacting concrete modified with supplementary glass and marble powders

- Analyzing the viability of agro-waste for sustainable concrete: Expression-based formulation and validation of predictive models for strength performance

- Special Issue on Advanced Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion

- Innovative optimization of seashell ash-based lightweight foamed concrete: Enhancing physicomechanical properties through ANN-GA hybrid approach

- Production of novel reinforcing rods of waste polyester, polypropylene, and cotton as alternatives to reinforcement steel rods